The Paris Review's Blog, page 8

May 23, 2025

Two New Movies

Amalia Ulman’s Magic Farm (2025).

Montreal/Paris/London/New York/Berlin/Chicago/Seoul/Amsterdam/Mexico City/Tokyo/Vancouver/Los Angeles. In the Day-Glo light of the mid-aughts, that slogan of American soft power swung off canvas tote bags everywhere. The message was optimistic: the world has no boundaries—at least, if you’re wearing American Apparel.

Magic Farm, the sophomore work of Argentine director Amalia Ulman, is that millennial dream fruited and fermented. Her characters work at a VICE-style gonzo web show, pal around with Chloë Sevigny, and proudly blaze a trail through the world, totally unaware that the trail they’re proudly blazing has already been paved and advertises Monday–Friday street-side parking.

Ulman’s grifters end up in the Argentine countryside chasing a tip that doesn’t exist. Quickly, they resolve to fabricate one—unconcerned with the ethics behind writing their own reality and indifferent to the townspeople’s actual lives, which, of course, have far more depth: the nearby farmland is routinely crop-dusted with a pesticide that’s resulted in a sickly, cancer-addled population. The Americans despair over crushes, bugbites, jobs, and the imagined pain of creating something revelatory out of nothing. Can magic be manufactured? Or does it, like factory-farmed corn, salmon, or cattle, end up tasteless, even cancerous?

Personal childhood heartthrob Alex Wolff (passing around a business card replete with the American Apparel font) swings between braggadocio and romantic ruin. Immediately, he is entranced by local soubrette Camila del Campo, a stunner who scampers up trees to post thirst traps. Chloë, his more mature love interest, is the hostess of the show. She is paraded around by the traveling circus, desperately unhappy with the cage she built. Meanwhile, Joe Apollonio swoons in the presence of Guillermo Jacubowicz, the good-natured hotel owner, culminating in a sexually tense but doomed laundry-washing. As an actress, Ulman is the most reserved of the bunch, playing a pregnant translator caught between the locals and the Americans.

As a director, Ulman is anything but reserved, excelling at tender moments of personal inadequacy, allowing characters to snip themselves down to the quick. She moves the camera with a sense of boundarylessness: the viewer is placed on the head of the dog, is shot into the air, and takes a ride around on a motorcycle. Unironically, boundarylessness is what killed American Apparel: their CEO, Dov Charney, was eventually ousted for sexual misconduct. The stores in Montreal/Paris/London/New York/Berlin/Chicago/Seoul/etc. closed one at a time, and then suddenly. The world, after all, is not edgeless. Magic Farm’s hapless protagonists may be oblivious to their surroundings, determined to cocoon themselves in the safety of their own problems—but, Ulman ensures, we are not.

—Nicolaia Rips

In The ADHD Muses, Bernadette Van-Huy—better known as the eponymous member of the art collective Bernadette Corporation—takes on the “fake theme” of ADHD. As to what makes the theme “fake,” I’m nonplussed. Perhaps it’s just a refusal to commit to an idea. The movie starts with jazz, but it’s all downhill from there.

The test group for this ironically engaged theme—which tracks with the collective’s interest in pouring identities into prefabricated forms and isn’t a terrible premise in the abstract—are two young women whose lack of apparent talent isn’t allowed to get in the way of the filmmaker’s affectionate curiosity about them. One of them, Marika Thunder, is the daughter of painter Rita Ackermann, a longtime associate of the filmmaker’s. A significant portion of the film is shot in what appears to be Ackermann’s studio, where Thunder and Tessa Gourin, an aspiring actress, woodenly recite scenes from Pulp Fiction or a Christopher Walken monologue that, like the title Annie Hall scrawled on an otherwise blank wall, don’t make themselves any more interesting than the average spazzed shoutout. Choppy editing doesn’t make the film kinetic or even lively. The older, figurative painter Eric Fischl gets name-checked—I guess he’s on the attention-deficit spectrum, as they say—and it’s a sign of how dull The ADHD Muses’s proceedings are that I would have welcomed an interview about his dusty work by the time the Mean Girls scene recitations started.

A long shot of Gourin walking along East Eighty-Sixth Street and interior-monologuing about her life so far and an extended studio visit with Thunder both fail to inspire. Gourin: “A really interesting fact about me is I’m always early.” If there was a script for the film, SMALL TALK! would be the header (and footer) on every page.

The outro to the film features an omniscient narrator offering a curious meditation on clock time, implying a thematic connection to the women’s personal orientations, but it’s a little late to be retrospectively tacking on a long view that the director’s subjects themselves lack. If there was a guiding concept behind the film, maybe it should have felt a bit more real to Van-Huy before she pressed RECORD.

—Paige K. Bradley

May 22, 2025

The Matter of Martin

Martin Amis poses for a photo in his North London home on Oct. 18, 2005. Courtesy of Writer Pictures/Graham Jepson, via AP Images.

“They’re waiting for an autograph from Salman Rushdie,” the man behind me explained. After everything he’s been through. People were gathering behind a barricade at a door of the 92nd Street Y, down the block from the one where I stood waiting for “A Celebration of Martin Amis.” A couple of minutes passed, during which time the man behind me also decided to tell me that he thought the attempt on Donald Trump’s life seemed staged. Then the actual Salman Rushdie arrived at our door, wearing a tan Yankees cap, and walked right in, unbothered by fans. Suspicious of my line mate’s sense of the nature of the assassination attempt and his suggestion that the crowd was there for a novelist, I excused myself and went to investigate. A woman at the barricade said they were there for Murderbot. (This, I gathered from Google later, is an action-comedy TV series.)

A literary writer in 2025 may not pull throngs of fans hanging off a barricade the way an action comedy TV series can. But the crowd passing through the lobby of the 92nd Street Y, there to hear a set of distinguished writers talk about Amis, was indeed soon in the hundreds. Martin Amis, whom Geoff Dyer once called the “Mick Jagger of literature,” was among our last great literary celebrities. Along with his crew of London writer friends—which included Christopher Hitchens, Ian McEwan, and Rushdie—Amis moved like a star, back when writers (I’m told) commanded that kind of public attention.

In the lobby, some attendees self-identified as Amis diehards: Paige McGreevy, who works at the United Nations, remembered being eighteen in Barcelona, staying out until six in the morning, sleeping all day in her blackout-shaded room, and then waking up and inhaling Money in bed. The novelist Julian Tepper recalled with a cringe the time he approached Amis at a PEN gala and did the whole “Mr. Amis, I just wanted to say—” thing. Another Money fan, Emilie Meyer, who said she was a friend of the Amis family’s, marveled at the way its protagonist combines piggishness with a nimble, pixielike wit. Meyer is a bookseller at Aeon Bookstore, and she often recommends Amis’s work to people who come in seeking books for a vacation—that way, she explained, they will always remember it as the trip when they read Amis.

Emilie is twenty-five. Most of the other young people in the crowd were there with groups from M.F.A. programs. Both the New School and NYU, I was told, arranged for tickets. Some of the students hadn’t read much—or any—Amis, but all seemed pleased to be there. Most of the attendees were closer to Amis’s age, and some were from his milieu. Anna Wintour entered; this being the second Monday of May, she was available. She sat down in the auditorium not far from literary agent Andrew Wylie, who represented Amis from the mid-nineties on. (Wintour, who also attended Amis’s London memorial service in 2023, goes way back with Amis; in their London youths, she dated his great friend the Hitch.)

A few rows back from them, I chatted with Hugo Guinness, another pal of Amis’s from those days, who fondly recalled tennis games and “lots of drinking.” Novelists were still cool and glamorous then, he said; playwrights too. He and his wife, the painter Elliott Puckette, had also attended the London memorial. This event, as the speakers soon made clear, was the New York version of that service.

The event was billed as a “celebration,” and I didn’t quite know what that would mean. I was thinking maybe a panel, perhaps some group discussion of his books. Instead a procession of venerated writers stood behind a lectern to deliver what were effectively eulogies; it was a celebration of life, two years after Amis’s death. Isabel Fonseca, Amis’s wife, reflected in gracious opening remarks on Amis’s recurrent interest in the theme of aging. She noted that he was searing on each stage of life, including old age, though he “hardly touched his own.” The speakers shared tender anecdotes about “Martin.” Jeffrey Eugenides, who spoke after Fonseca, noted that Amis was actually a “sweetheart” who’d gone to the trouble of shipping his daughter’s stuffed animal, left behind at Amis’s rental house in Brazil; cigarette ash was stuck to the stamps. (That the speakers noted that Amis could be tender did not surprise me: Anyone who has read Amis’s writing about children, not to mention the boundless sorrow of losing his cousin Lucy Partington, the victim of a brutal murder, suspects this.) Lorrie Moore described how he aged gracefully from an enfant terrible, recalling the handful of times she encountered him. She said, intriguingly, that money in his work functioned as a “La Brea Tar Pit of the soul.”

People shared snippets of conversation and memories, praised his style and personal qualities, and read long passages from Amis’s work. It was during these readings that the biggest laughs came. Amis writing about himself is probably funnier than most people could be about him. (Though it was also very funny when Fonseca said that to crack open a Martin Amis book is to wonder, “When will something truly horrible and humiliating happen to this man, or this woman?”) A. M. Homes read the opening of The Rachel Papers, and Jennifer Egan read from The Information, Amis’s great tale of literary rivalry and flailing. Nathan Heller, was the only speaker who had never met Amis: “I knew him as a writer, which is the way I suspect writers would most like to be known.” He spoke to and for the many of us who also knew Amis only through his work—those of us pulled to the event by the Nabokovian throb of recognition. Of all the speakers, Heller best captured, and reenacted, Amis’s sheer sense of wonder and glee about literature. One pleasure of reading Amis is the electricity of his alertness to the world: Heller described him as writing realism with “the saturation turned up.” Recalling the “ecstatic snicker” that comes from reading both Martin and Kingsley Amis—this “somatic line of literary happiness”—Heller reminded us that reading Amis is fun. Murmurs of how great Heller was circulated in my section.

Overall, the tone of the speeches was reverent—appropriate, probably, to the occasion. Still, Amis was a writer who ventured gleefully beyond the bounds of good taste. Rushdie, who closed out the evening, recounted the cheeky word games they used to play; in one, they replaced the word Love in titles with the words Hysterical Sex, to get to “Hysterical Sex in the Time of Cholera” and things like that. A close friend of Amis’s, he shared his regret, his voice almost breaking, that he never properly got to say goodbye. “So I’ll say it now,” he concluded. “Goodbye, Martin. And I send you a lot of hysterical sex.”

Amis’s work was the focus of the event. But Amis was interested in life—his own, and those of the writers he examined in his parallel career as a critic. As the critic Parul Sehgal (who cohosts a terrific podcast on Amis called The Martin Chronicles) wrote in 2020: “The hallmark of his own literary criticism is his interest in the pressures that life and art exert on each other.” His own life seemed to exert much. He was not a hermit type. He had a rich world—relationships, children, tennis matches, vexed paternal relations, feuds, spats, dental work (sorry!). Amis ran headlong into the mix, as any satirist, arguably any writer, should. He went after Hitchens in print, who went after him in turn. He defended himself vigorously against claims that his major dental surgery was cosmetic, and friends did the same, for example in a ten-page New Yorker spread—covering the oral surgery, a massive book advance, and his falling-out with Julian Barnes and Pat Kavanagh—which appeared in 1995, a few months before I was born. One critic, Rushdie told the magazine, “behaved disgracefully badly in the matter of Martin.” But on Monday, none of this came up. The asterisk that sometimes hovers over conversations among young people today about his work (yes, the portrayals of women aren’t always great, but … and yes, he was sort of controversial, but …) were absent too. That’s okay: it was, after all, a celebration. It was all very pleasant for the man who, in the eighties, became the face of what one critic called the “new unpleasantness.”

Amis’s writing is stylish and screwy and grotesque and vulgar. The jokes come at an unhinged pace. He was an exquisite writer of the male body and the horrors of inhabiting one: “My hair hung on my head as if it were a cut-price toupée,” Charles Highway (Charles Highway!) reflects in Amis’s debut novel The Rachel Papers. That same character savages the “Big Boys” that are his pimples and speaks of “laundering my orifices,” as “they went all to hell if not scrupulously maintained.” A genital region is referred to as a “rig.” The names, across his books, are insane. Amis calls characters things like Spunk, 13, Fart Klaeber, Sod. A female cop (or as she calls herself “a police”) is named Mike Hoolihan. A quartet of violent dogs are Joe, Joel, Jeff, and Jon. That he called a writer-character Martin Amis, or so the story goes, caused his father to throw Money across the room. Famed for his antic satire, he was later unafraid to take on—in his novels, nonfiction, and short stories—genocide and the end of the world, too.

No one is doing it like Amis did. That the contemporary fiction landscape lacks his flavor of frenzied humor, chaotic storylines, maximalist characters, and full-throated play is a loss. But perhaps that’s how it should be, especially for a critic who championed writers whose work could not be mistaken for anyone’s but their own. He was an influence—the 92nd Street Y is planning more events featuring young writers affected by Amis—but he was also singular. Perhaps his legacy, more than inspiring copycats, will be to have opened up a sense of freedom, a sense that, yes, you really can do what you want.

The auditorium in the 92nd Street Y’s Unterberg Poetry and Literature Center has the names of a handful of famous writers and thinkers emblazoned on the walls. I was amused to note that directly to the right of where I sat, the wall read SHAKESPEARE. Amis was fascinated by, and irreverent toward, the Bard of Avon. In The Rachel Papers, young Highway suggests that Shakespeare had it easy because he could just wrap things up with a wedding; far harder to make it through the narrative muck of twentieth-century relationships. And one of the all-time Amis passages, for me, is John Self’s close analysis in Money of a portrait of Shakespeare: “The beaked and bumfluffed upper lip, the oafish swelling of the jawline, the granny’s rockpool eyes. And that rug! Isn’t it a killer?” (A rug, in Amisese, refers to a head of hair.) Shakespeare, to the comfort of our hero, “looked like shit.” Amis, who mocked literary giants, nonetheless betrayed in his journalism, and in the frequent references to great writers in his novels, an awe for the stars that preceded him—though he never stopped denigrating playwrights, whom he suggested, in his memoir Experience, were knighted far too much. “It is very funny that Shakespeare was a playwright,” he wrote. (Amis was himself knighted posthumously in 2023.)

After the speeches, everyone filed back onstage for a charming farewell. No one took a bow. It was not a performance, not really. In the lobby, I chatted with a couple of members of the extended Amis–Fonseca family, one of whom observed that Amis talked like he wrote. The evening, they concluded, had felt authentic.

Amis showed, even early in life, a canny awareness of his own image (one doesn’t become a literary Mick Jagger by accident) and both his capacity and his inability to shape it. In a letter to his father and his then-stepmother Elizabeth Jane Howard, ahead of his Oxford interview, a teenage Amis wonders: “Shall I be refreshingly different, stolidly middle-brow, engagingly naïve, candidly matter-of-fact, contemptuously sophisticated, incorruptibly sincere, sonorously pedantic, curiously fickle, youthfully wide-eyed? Should I bow my head in solemn appreciation of the hallowed atmosphere of learning? Should I play the profound truth-seeker, the seedy anti-hero, the crusty society-observer, the all-discerning beauty-appreciator?” Fair questions, all. But his conclusion, touching and wise, is: “No, I suppose I shall end up … just … being…… myself.” Himself he seemed to stay.

Amis’s friends and readers last week, looking at his life, did not attempt holistic description of who he became. In his criticism, Amis sometimes quoted at length from the writers he reviewed. I am not reviewing Amis, of course. But in the spirit of skimming inspiration from him, I will end with a passage from Experience about the trouble with life and the structure of it all:

The trouble with life (the novelist will feel) is its amorphousness, its ridiculous fluidity. Look at it: thinly plotted, largely themeless, sentimental and ineluctably trite. The dialogue is poor, or at least violently uneven. The twists are either predictable or sensationalist. And it’s always the same beginning; and the same ending.

Lora Kelley is a writer who lives in Brooklyn.

May 21, 2025

A Missive Sent Straight from the Mayhem: On Michelle Tea’s Valencia

Photograph by Juergen Striewski, via Wikimedia Commons. Licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

Michelle Tea once described Valencia as “a snapshot, more or less, of my twenty-fifth year on earth, written not how it happened but how I felt it happened.” It feels right, then, in a numerological sense, to be addressing Tea’s classic twenty-five years after its turn-of-the-millennium publication. One way to do so would be to hail Valencia as an exuberant, hilarious record of a truly unprecedented and mutinous time in lesbian/queer history—the San Francisco dyke scene of the nineties—and by lauding its spot-on testimony to the fashions (“I had big purple hair, a green studded collar, and roller skates. I looked insane”), the locales (Mission dive bars and apartments, the Bearded Lady, a whorehouse in the woods of Marin), the drugs (booze, crystal meth, mushrooms that taste like “a trunk of moth-eaten clothes,” Valencia Street coffee), the pre-internet technologies (zines, open mics, personal ads in newspapers, pay phones, latex gloves), the gender vibes (all over the place, but generally still using she/her pronouns), and the kinks (“Petra was really into the knife. I got the sense that I could have been any body beneath her, it was the knife that was the star of the show”). Such a read would underscore Valencia’s status as one of the most vivid, thrilling documents of its time, while also ensuring that the explosive and inventive culture it portrays isn’t lost to history, as so much queer history, especially of the lesbian, poor, and debauched variety, can be.

But here I want to talk about other things that reading Valencia now makes me think and feel. Namely, I want to talk about Valencia’s achievement in transmitting the conjoined rush of being young, being high, being in love, and becoming a writer—and how that rush feels when these things are pursued all at once, with great abandon. Writers often convey this rush in retrospect, after the dust of an era has settled, or after they’ve removed themselves from a scene (and/or from the substances fueling it). That’s its own trick—and one that Tea has pulled off elsewhere, such as in her great 2016 novel Black Wave. Valencia is something else, maybe something more improbable. It’s a missive sent straight from the mayhem. I still don’t know how she did it.

So, how did she? I’m willing to bet that this passage from Tea’s 2018 collection Against Memoir describes her process at the time pretty accurately: “I remember being inside a nightclub, sitting up on top of a jukebox, scribbling in my notebook by the light that escaped it. All around me the darkness writhed with throngs of females, their bodies striped and pierced, as shaved and ornamented as any tribe anywhere, clad in animal skins, hurling themselves into one another with love. What feeling it filled me with. An alcoholic, an addict, I know what it is to crave, and the need to take this story into my body was consuming. For years I sat alone at tables, writing the story of everything I had ever known or seen.” It’s a kind of miracle, when everyone’s fucked up and fucking, for there to be someone just as fucked up and fucking, but also scribing it all down, and rendering it into literature. And here we have to thank the Higher Power of our choosing that Tea perched atop that jukebox, sat at that bar table, and scribbled. As Tea puts it in a Valencia-era essay titled “Explain,” in a passage that never ceases to make me want to pump my fist: “Why not me. My poverty and the girls that don’t love me and how drunk I got the other night. How I was a prostitute. It seems to be literature when guys write about it, it’s practically become a genre, men writing about their transcendental trips to the cathouse, their orgasms and revelations. Or men writing about women’s lives in general. Straight people writing about queers and white people writing about every other race on the planet. The writing that I love, it’s the Other telling the part that got left out, the truth. Not only a writer and a historian, but a spy.”

Some spies don’t have to labor too hard to throw others off the trail; being a diminutive female is usually enough to keep people from recognizing the genius at hand. “There’s this awful copy shop near my house,” Tea says in “Explain.” “I go there all the time because I’m too lazy to walk up to Kinko’s. The guys at this place are such jerks. I had a bunch of my books and he said, Are Those Your Books? Yeah. You wrote them? Yeah. He makes this suspicious little scrunched-up face. Are You Sure? he asks. He means it. Looking at my dirty fucked up hair and tattoos scrawled up my arms and whatever else he saw. You Just Don’t Look Like You Would Be A Writer. Yeah well keep an eye out for yourself in my next novel, asshole.” And just like that, there he is—first in her essay, and now here. That’s one thing writing can do—seize the means of production. (Asshole!)

Tea makes it look easy to write from the eye of the storm, but let’s pause for a moment to appreciate the rarity. Surely her hypergraphia—a compulsion to write that she has compared to other addictions—helped; as she describes her disposition in Valencia, “Oh, I should be quiet and full of potential like all those still flowers, but I know I am a weed and I’ve got to blow my seeds around the garden.” Yet there’s inevitably a tension between writing and living hard. Sometimes getting wasted makes writing possible (“I always drank while I wrote, and I loved drinking so much that the drinking kept me in my chair, writing,” Tea has said); at other times, it can threaten the whole project, including the project of staying alive. “I could not imagine what would happen to me if I smoked more pot,” Tea writes in Valencia, before adding, in a classic step toward self-abandonment, “I held it to my lips and drew it in.” Being high on love presents a similar conundrum: after filling pages and pages about different girlfriends in Valencia, Tea tells us: “I cannot write when I have a girlfriend.” The mystery of the balancing act goes on.

Maybe one way to think about it is, this balancing act works until it doesn’t, and Valencia emanates from of a time when it was working. For some, it stops working before age twenty-five, but twenty-five seems to me like a pretty typical high mark, before the shit really starts to hit the fan. Denis Johnson’s collection Jesus’ Son—published a year before Valencia—comes to mind here, in part because both Jesus’ Son and Valencia capture so powerfully what Johnson called, in reference to his collection, “the experience of the youthful soul,” and in part because of something Johnson once said in response to an interviewer who asked him if he felt nostalgic for the wild, druggy, desperate days that Jesus’ Son describes. “Well,” Johnson said, “just for the self-abandonment of it. Just sometimes there’s nothing better than lying down in the dirt, being completely hopeless and helpless, because then of course you have no responsibilities, and that kind of appeals to me. But the problem is you can’t do that for long. There’s always a steam roller headed your way.”

The protagonist of Jesus’ Son collides with that steamroller in the book’s pages; in Valencia, the rumble remains in the offing. You can hear it faintly in passages such as: “And Laurel got a girlfriend in Amsterdam, and George got a boyfriend who wouldn’t top him, and eventually Candice did like me, and eventually Iris no longer did, and my older poetry friends from the bar left behind secret addictions as they moved to far away states to dry out, and Ashley got a boyfriend and disappeared completely, and here I sit with my coffee.” Some folks may have begun to move on or move out, but for now our narrator stays put, coffee and notebook in hand. Valencia is a freeze-frame of that ongoingness.

When I imagine an interviewer asking Tea if she feels, twenty-five years hence, nostalgic for the experience of the youthful soul captured so lavishly by Valencia, I think about something she said in conversation with another great chronicler of queer life, Mattilda Bernstein Sycamore. “When I was younger and saw nostalgia in older people,” Tea tells Sycamore, “it really scared me. I never wanted to have that kind of a relationship to my own history. It felt like everyone always thinks that their time was the best time, and it was almost a plan I came up with when I was younger, or a pledge I made to myself, to not get old and boring. Part of that means not being nostalgic.” To honor Tea’s wisdom here, I invite us to read Valencia not as a postcard from a bygone era, but as a shimmering, ever-alive thing, an always-open portal to the kind of youthful soul who vows, as Tea’s narrator does, to “run through the streets in excellent danger.”

Valencia lets us touch this excellent danger whether we have grown away from it, are smack in the middle of it, or never chose to court it. No matter how dangerous or bleak things get, Tea’s narrator remains fundamentally optimistic and questing. Faced with the advent of darkness, she asks, “What would the night give us?” This fundamental buoyancy—which is aided and abetted by Tea’s never-flagging sense of humor—steers us away from moralizing, away from the quicksands of trauma, and toward possibility and gift. “In the mainstream popular consciousness,” Tea tells Sycamore, “certain things are like irredeemably bad. Like getting strung out on drugs is bad, and you’ve lost something if you’ve gotten addicted on drugs. This idea that you’ve lost control, or you’ve lost your mind, or something. Or you’ve lost your virginity, you know how girls always ‘lose’ their virginity. Or if you do sex work, you’ve somehow lost … Any transgression get marked as a sort of loss. And what’s never talked about is what you get from it.” Valencia is all about what you get from it.

This essay is adapted from the foreword to the twenty-fifth-anniversary edition of Michelle Tea’s Valencia, which will be published by Seal Press in June.Maggie Nelson is the author of several books of prose and poetry, including Pathemata, or, The Story of My Mouth; Like Love; The Red Parts; Bluets; the National Book Critics Circle Award winner The Argonauts; and On Freedom. She teaches at the University of Southern California and lives in Los Angeles.

May 20, 2025

Recurring Screens

My iMac G3, running Warp.

The world’s first screen saver was not like a dream at all. It was a blank screen. It was called SCRNSAVE, and when it was released in 1983 it was very exciting to a niche audience. It was like John Cage’s 4’33″ but for computers—a score for meted-out doses of silence.

Instructions for using the screen saver were first published in the tech magazine Softalk. The headline read: SAVE YOUR MONITOR SCREEN! Across from the article was a full-page photo of firefighters rescuing a computer monitor from a burning building.

Softalk, December 1983.

The article explained that there was a new danger facing computers: “burn-in.” Basically, if a screen showed the same thing for too long, the shadow of its image would be tattooed to the pixels. A screen saver stirs the soup of the image to keep it from sticking to the screen.

The science behind burn-in is grotesque: picture swarms of electrons like locusts flinging themselves at the thin phosphor coating of a screen, chewing holes. A screen saver periodically smokes the locusts out, thereby saving the screen from the disfigurement of monotony.

SCRNSAVE was a big deal engineering-wise, but it never caught on with most computer users, who, reasonably, did not see the value in making their screens shut off every few minutes. Before long, software developers figured out how to convince people to adopt screen savers: aesthetics. The screen savers had to make people want to look back at the screens they had just looked away from.

In 1989, a software company called Berkeley Systems launched a program called After Dark. Instead of just going blank, After Dark screen savers showed animations: flying toasters, or falling rain, or overlapping curved lines in neon gradients. The new screen savers took the world by storm. But in terms of preventing burn-in, flying toasters were no better than a blank screen. Their purpose was pleasure.

After Dark 2.0, Berkeley Systems, 1992.

I don’t know the exact percentage of my life I have spent watching screen savers, but I’m sure it’s equivalent to the amount of time I’ve spent peeing or stuck in traffic. I’ve probably watched screen savers for the same amount of time I’ve spent dreaming about the car, the airplane, and the hill. The details change, but every night for years I’ve dreamed that I’m in a car, and that I’m on an airplane, and that I’m jumping off the top of a hill.

When I was a kid, my favorite After Dark screen saver was called Warp. In Warp, you’re flying into the center of a tunnel of tiny white stars. Nothing happens except that you keep going forward. Nothing changes, but it always seemed to me like it might. Like if I kept looking I might finally see past the tunnel’s center. I’d watch until an adult snapped their fingers in my face and told me to pay attention.

In my least favorite screen saver, 3D Maze, you’re running through a maze with red brick walls and a white asbestos-tiled ceiling. The light is cold and fluorescent, like in an office building. Sometimes you go the wrong way and have to briefly run backward. Sometimes the whole maze flips over and you keep running on the asbestos ceiling like nothing happened. The worst part of 3D Maze was that it could appear on any computer screen without warning. Once the screen saver had started, it was hard to look away, even though I knew what would happen. Every night in my sleep I climb the hill, and I jump off the top.

***

There are no screen savers in pleasureis amiracle by Bianca Rae Messinger. But the poems talk about memory as though time itself were a screen saver—a series of recurring dreams that overlap. Messinger writes:

nothing is transposed so she goes back to sleep with no thinking about

fucking but about water or is it the same object anavenue circles it tying

the new ocean and outside there’s a field which is familiar though

destroyed sometimes she has torun as the water comes fast and tan, so

she steals a car in the next scene like a spaceship so fast

Many words in pleasureis amiracle are merged. They make me think of parataxis, the pushing together of distinct ideas in writing. Messinger imagines parataxis as a physical form of adhesion. Words can stick together, and so can everything else. A new ocean to a familiar field. An image burned into a screen.

By the time I started high school in 2008, the screen saver boom had faded. Bored with the limited options on my white plastic MacBook, I downloaded one called Electric Sheep, whose selling point was that it would never show the same thing twice. Every time the screen saver ran, my computer would connect to other computers on the internet, and together they would make new kaleidoscopic patterns in new kaleidoscopic colors. The website explained:

When these computers “sleep,” the screen saver comes on and the computers communicate with each other by the internet to share the work of creating morphing abstract animations known as “sheep.” The result is a collective “android dream,” an homage to Philip K. Dick’s novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?

I was excited to be part of an internet of dreaming sheep. But for some reason my computer could never connect. Every day it made the same four patterns in the same four colors. Instead of many sheep remembering many dreams, the screen saver was like one sheep trying to remember one dream and only seeing fragments. A car, an airplane, a hill.

Bianca Rae Messinger believes phone calls are a form of time travel. For Messinger, if it’s morning on one end of the phone, it’s morning on the other. “If you walked to California from New York,” she explained to me once, “it would be morning by the time you arrived, even if it wasn’t when you left.” A voice on a telephone travels close to the speed of light. Ergo, time travel. In pleasureis amiracle, she writes:

wefight in your red car about space,

whether it’s consecutive, you say, whether it’s observatory

no, i say no too as i tend toagree

without wantingto, but yet each

moment feels improvisatory…

Can time be improvised if we are trapped in it? If we are trapped in time, can we teleport to other places? According to some scientists and science fiction writers, the answer is yes—through something called a tesseract. In A Wrinkle in Time, Madeleine L’Engle describes the tesseract by way of an ant. I’ll summarize:

If an ant wanted to walk from one side of a length of fabric to the other, it would need to walk across the entire surface. Here’s a diagram that L’Engle included in her book:

But what if someone folded the fabric in half? The ant would be able to teleport immediately from one end of the fabric to the other.

Now imagine the ant has been walking along a box instead of a piece of fabric. To travel instantly to the other side, the ant would need to fold the box in half without breaking it, which would mean invoking the fifth dimension: a tesseract.

Are phone calls tesseracts? What about the internet, or dreams? Messinger writes:

doing everything at once doesn’t feel like

an action exactly…this neighborhood

smells like the one I grew up in but

that’s 300 miles away.

pleasureis amiracle asks whether memory is a type of action and whether a repeated action is a form of remembering. The book answers: Memory is an action like the spinning plate of the microwave. It’s morning on both sides of the phone because you remember morning. If you leave a computer awake long enough, it will eventually remember to show a screen saver. Every time it sleeps, the computer dreams its recurring dreams.

***

My grandmother’s iMac spent most of its time showing Flurry, a dancing rainbow spider that was the first-ever Macintosh screen saver when it debuted in 2002. My grandmother was very tech-averse and preferred to write on a yellow legal pad. Whenever she needed to use the iMac, she’d call me with questions. “Thank goodness you picked up,” she’d say. “An alternate universe has emerged in the corner of my screen. Can you help?”

I quickly gave up on trying to convince her to use words like “window” or “application” instead of “planet” or “dimension.” Her descriptions felt closer to the real experience of using a computer—like trying to fly a spaceship. She read a lot of sci-fi. I helped her download Ursula K. Le Guin’s The Lathe of Heaven from iTunes as an audiobook. We listened together as a man altered collective reality with his dreams.

My grandmother’s stereoscope.

A glass slide of my grandmother being pulled by a horse.

One of the few things my grandmother’s family managed to bring from Austria when they fled the Nazis in 1938 was a stereoscope—a three-dimensional image-viewing device. When I was young, my grandmother sometimes let me look through its binocular-like lenses at glass slides of her in Austria: a three-dimensional child in a cart pulled by a three-dimensional horse.

When my grandmother died, everyone agreed I should be given her computer. Actually, at first everyone agreed that we should throw her computer away, but they said I could have it if I really wanted it.

My grandmother’s computer looked like all iMacs had looked for a decade—like a piece of sheet metal with an apple stamped on it. I took it home and it runs decently enough. Not quickly, but respectably. Not quite light-speed, but telephone-speed.

The first iMacs did not look like sheet metal. Instead, they looked like colorful plastic bubbles. I recently bought one on eBay. It’s from 1999 and made of pink translucent plastic—a color Apple called strawberry. My concept was that I’d try and replace my 2021 laptop with the Strawberry. But when the Strawberry arrived, it wouldn’t turn on. When I finally got it to wake up, it could not load most websites.

I took the Strawberry apart thirty-nine times. (I kept count.) I didn’t really know what I was doing. I cut my hands open on the logic board more than once. There’s still dried blood on the hard drive. But despite my best efforts at modernization, the Strawberry has refused to accept any of my updates. It only wants to exist in 1999, to connect to an old internet that hardly exists anymore. These days it mostly runs screen savers. Warp is still my favorite.

The Strawberry and my grandmother’s iMac.

Toward the end of pleasureis amiracle, Messinger writes,

being able to ‘live’ in one’s own memories was what caused

the eventual collapse, and it being joyful. a radio on repeat…

she thinks, an easier way to say this is that dreams are now considered life forms.

I used to think I could use old computers to break open time and get everything back; to fold the screen in two and make a tesseract. I wanted to know what would happen at the end of my dream with the car, the airplane, and the hill. I wanted to go inside the stereoscope and see my grandmother in three dimensions in a place that no longer exists.

But when I finally went back in time, what I found instead were screen savers. Radios on repeat. Places where you could look at time and watch things move around inside it, at the speed of a telephone, just slower than light.

Nora Claire Miller’s debut poetry collection, Groceries, is forthcoming from Fonograf Editions this fall.

May 16, 2025

A Man Is Like a Tree: On Nicole Wittenberg

Nicole Wittenberg, Woods Walker 7 (2023–2024), oil on canvas, 96 x 72″.

Nicole Wittenberg has painted a variety of subjects over the last fifteen years, but two predominate: lush and lyrical landscapes, often of places where water meets land—generally unpopulated, but with an occasional figure glimpsed among the trees, as if to provide focus and scale—and her less well-known male nudes (along with an occasional pulchritudinous female counterpart), often engaged in sex acts that have seldom been depicted in Western high art. These pictures show sexual beings up close and personal, though maybe up close and impersonal is more to the point. They are exercises in concision and point of view; if you get close enough, anything looks big, and these dicks look monumental, like big trees in a low-rise landscape.

Despite their provocative, even polemical subject matter (why not paint dicks?) Wittenberg’s paintings of blowjobs and the form of self-care commonly known as jerking off are also concerned with style, with the how of painting as inseparable from the what. In paintings like Blow Job and Red Handed, Again, both from 2014, the how relies on a gesture that is high-risk and directionally sound. It is the precise placement along with a certain velocity that allows the gesture to adhere to the form. In terms of accuracy of brush mark, Wittenberg might be the Franz Kline of dick paintings. You have to paint something, and you may as well paint what interests you. Sometimes you might paint what interests others, to see if it also interests you. Are these paintings pornographic? I don’t know, maybe. I don’t really care—perhaps that descriptor is even a compliment. I’m not especially polemical in my approach to art or to life, but suffice it to say that the analytically sexual gaze in painting should be equally and unreservedly available to all. These are paintings that say, Oh, is this image making you uncomfortable? Get over it.

Nicole Wittenberg, Red Handed, Again, 2014, oil on canvas, 36 x 48″.

Wittenberg’s landscape paintings and pastels, on the other hand, belong to a long ancestral line; they derive, meanderingly, from some of the earliest paintings produced in this country, and they constitute a contemporary reframing of a potent and closely held self-image: the sense of wonder engendered by the pristine vastness of the North American landscape. It’s as F. Scott Fitzgerald wrote about the early Dutch settlers sailing into New Amsterdam, seeing for the first time the “fresh, green breast of the new world.”

Wittenberg posits two basic visions of this Arcadian heritage, the peopled and the unpeopled landscape, and both stem from her time living among the shallows and the depths of coastal Maine, where she has summered the last dozen or so years. One type of picture shows a densely wooded grove bordered by water, seen from the middle distance in the indistinct light of early morning or evening. In these seminocturnes, the landscape is shadowy and mysterious, more or less inaccessible—perhaps the view from a boat of one of the innumerable uninhabited islands that dot the Penobscot Bay, as in Cradle Cove (2022). Or the view from the shore as we contemplate a stand of trees halfway to the horizon in the fading pink light, as in After the Storm (2024). The illumination is dim; the trees are backlit and the colors of the woods and water as well as sky are all dark and close-valued. These pictures are portents of existential unease, of loneliness and something unresolved, and as such are a continuation of a soulful lineage; one feels Marsden Hartley standing behind them, and behind Hartley stands Albert Pinkham Ryder. Wittenberg’s luminous, unpeopled landscapes have a closely held, interior feeling of something that resists us, of an awareness just out of reach.

Nicole Wittenberg. Woods Walker (2021), pastel on paper, 15.5 x 11.5″.

The other type of landscape painting is also of the Maine woods but seen from within a grove of towering white pines. It is perhaps midday, the contrast between light and shadow is high, and a solitary figure wends his way beneath the swooping branches. These are the Woods Walker paintings, of which Wittenberg has painted a number of variations. The addition of the single figure marked a turning point in her art; we are inside the forest now, the figure is our surrogate, and though more of a participant in the passage of minutes and hours and the change in light, we are still vulnerable to the vicissitudes of nature, weather, and memory. The unspoken worry: Will we be able to find our way back? The ebullience one feels in that moment, walking in the brilliant light, arms swinging by one’s sides, may be short-lived.

Wittenberg’s paintings all share a concern for compression and for scale: dicks as big as trees and trees towering over diminutive hikers. Both are a function of point of view, which itself constitutes the painter’s first decisive act. The point of view goes a long way in setting a picture’s narrative capability. We only see what the painter chooses to show us; what is left out is not our concern. We can’t know what happens in the next instant, or after we stop looking. The mystery continues to unfold, with us or without us. This exact quality of light—hold it! In the next instant it changes, forever. The melancholy of painting.

David Salle’s essay “A Man Is Like a Tree” will appear in Nicole Wittenberg, the first survey of Wittenberg’s work, which will be published by Phaidon in July. The publication of the book coincides with two solo exhibitions of the artist’s work, at the Ogunquit Museum of American Art and the Center for Maine Contemporary Art.

May 15, 2025

A Night and a Day and a Night and a Day and a Night and a Day in the Dark

Photographs courtesy of Lisa Carver.

Day One

All around me are short, shiny young Romans groping each other. The old ones engage in the more solitary pleasures of hawking loogies and eating out of greasy paper bags. I’m on my way to a dark retreat on a farm so high up in the mountains it requires five modes of transportation to get there—plane, train, metro, bus, taxi—each more confusing than the last. You buy your bus ticket at a particular newsstand nowhere near the bus. The only reason I knew this was because Antonello, the dark-retreat guide, had emailed me travel instructions … paragraphs of them … which I had memorized for dear life. Clutching my ticket, I tried to go through gate ten up the stairs to platform ten, as instructed, but the gate was locked. I tried gate eleven, but there was a sign saying not to cross the platform, which would have been the only way to get to ten. Vomit or diarrhea had been flung over the wall of the stairwell at regular intervals the whole way up. How did anyone have so much stuff in their guts? And why would they keep going up the stairs? I would have laid down and called 911. These Italians are of hearty stock. The smell was amazing. The arrow indicating the way to the metro switched directions so many times it curled and pointed at the sky. I guess you just guess here. Don’t even think about asking for help from the people in little cages like tollbooths scattered about. Signs in front of the booths warn in English: “We’re Not Here to Give Information.”

At last I alighted in Sora, the town closest to the farm, population five thousand, and called the taxi driver, Giulia, but she only giggled and said her boyfriend took her car and she had no idea when he would be back. I walked the streets of Sora and noticed that all the clocks were off, but each told a different wrong time. Actually, now that I think of it: Other towns don’t even have clocks anymore, do they? Everyone’s looking at their phones.

Which is one reason why people go on dark retreats. It’s the only place you can escape your phone, with its light and sounds. When my husband Bruno’s ex-wife Emilie asked why I would torture myself like that, I gave my usual answer: I don’t do anything for why; I do everything for why not. But this is more than a whim. I used to be fine with how I am: never staying in one place or with one person. But lately something feels off, feels in need of fixing, and I don’t know where the problem is. Could be I will find it in the dark. That’s historically what dark retreats are for: to heal body and mind when more conventional methods fail. Often a mirror would be secured over the bed as a passageway for ancestors or spirits to give you whatever advice they’ve been saving up. I’ve had too much hubris to listen to anyone’s wisdom, especially my ancestors’, considering half the ones I know about were rapists or murderers. But if we learn the most from mistakes, it follows that the worse someone lived, the better their advice must be. Hold on, dead Carvers, I’m coming!

I was waiting as instructed at a fountain in the middle of town with a directional arrow pointing inexplicably straight down to the center of the earth when a woman in a bikini hanging out of a banged-up car with no taxi sign hooted at me.

“You must be Giulia,” I said.

“I must,” she answered—not sarcastically, but as a simple imperative—and we were on our bumpy way.

The farm is made up of lush hills that stretch empty all the way to the empty sky. So peaceful. Lethargy rolled through me in waves as Antonello showed me around, two chickens in tow. Antonello could have been thirty or sixty. He was open yet unreadable, joking yet serious, bony and taut yet gentle. He looked like he was born on this farm (he was) and would die here, just like his father and his father before him. I said I was hungry, and he yanked some grapes off a vine on the wall and handed them to me. I’m glad I told him I was a vegetarian! He looked capable of grabbing one of the chickens, wringing its neck, plucking its feathers, throwing it on a fire, and handing that to me as easily as the grapes.

At the end of the line lay my dark room. It’s basically a cave, its stone walls carved into the mountainside and fitted with a bed, a dresser, a card table, a chair, and a doorless bathroom over to the side. No nightstand for the book I need to read in order to sleep or the notebook I need to keep in order to live. For the first time since my father taught me to read and write at two years old, I would be without both. I did bring a tape recorder with black electrical tape over the red “on” light just in case I have some thoughts, but it’s not the same. Writing has been my one constant. I was about to be truly alone. For a night and a day and a night and a day and a night and a day.

Antonello asked what meditation method I’d be using to manage anxiety or fear. I said none. He looked dubious. I said, “We’re just animals. Animals crawl down into pitch-black holes all the time. I think it’s normal.” He said, “So your method is no method.” I got irritated at that, because I will not be using the no-method method! That’s a method! If you plan for something, that’s what you’ll get. I don’t want to manage my fear—I want to meet it. But first, dinner.

We took Antonello’s seventies van down to the regular part of the farm where British, Portuguese, Romanian, Dutch, French, and Italian guests gathered around two long tables pushed together. No one but me came for the dark room. The others are here for relaxation, nature, silent horseback riding … The next time I sit at this table, everyone here now will be gone, and a new pack will have arrived. I don’t join in the conversation.

“Are you ready?” Antonello asks when I put my fork down.

Oh, yes.

Day Two

(transcription numbered with each time I turned the recorder on)

1.

I just had my once-daily human visit, as such. Antonello knocked on the door and wordlessly placed some food in the vestibule between the outer and the inner door. He had said my meal would arrive at one o’clock each day, so I figure I’ve been in here fifteen hours with nothing to say worth turning this recorder on for. If I hadn’t just had that fractional interaction with the world to remind me there is a world out there, who knows if anything at all would have occurred to me as worth preserving for later. In here it feels like there is no later.

When I went to sleep last night, it felt normal. You sleep in darkness and silence. But when I opened my eyes in the morning and there was no light and no coffee and no bustle of stepchildren getting ready for school, I was instantly thrust into an altered state. I started hallucinating my surroundings. Furniture, walls. Not seeing it—I was imagining it. And imagining was exactly the same as seeing. It’s making me wonder how much I imagine what I think I’m seeing out there in real life too.

Eating in here is nothing like the eating I’m used to. Sometimes I get the fork to my mouth and there’s nothing on it—it must’ve fallen off. And what even is it? Something that could have been eggs with nuts inside. A spongy breadlike thing—mayhap a giant mushroom? And some really sour lettuce, possibly seaweed. I don’t know this food and I don’t know the man who brought it—not really. You just have to trust. It must’ve been like this in the womb: you didn’t decide anything; stuff just came; you just ate it. I love when things get down to their simplest form. After a few bites, I was full. Everything is slowed down here, functions are going extinct. I pictured my digestion trying to outrun the slowness and then just shrugging and curling up for a nap. This constant game of intake and energy conversion and discharge and beginning again before you’ve even finished one job … why didn’t it ever occur to me I don’t have to keep going and going? I could just … not eat.

I hallucinated stepping out onto the balcony, which doesn’t exist. I looked down the valley, which doesn’t exist. I didn’t exactly feel my body moving, going outside. I was just doing it. It was totally natural. It’s so still here, I guess my brain knew I needed to see and move or I’d go crazy, so it let me see and move in this other way that has always existed, I just never had cause to tap into it before.

I also hallucinated two rectangles of light cast on the wall from two windows instead of shadows. Wait a minute. That’s what windows do. Ha ha ha! But in my brain windows cast shadows, and this was opposite. I thought that for at least thirty seconds. And then just as it had drifted in, it drifted away: the hallucination, then the awareness that it was a hallucination, then the story I built about what it means to hallucinate.

Nothing spectacular has shown itself—nothing like the dragon that visited the Buddhist monk on his dark retreat that he talked about on a YouTube video. It’s all mundane. I shouldn’t say mundane because it’s very beautiful. What I mean is it has become ordinary almost instantly—the ways of the dark.

I tried hallucinating on purpose just to see what I could see. I saw a snowy mountain dotted delicately with evergreens and a cabin. Then I remembered where I’d seen this mountain before: in a large Japanese painting behind the sofa at Mrs. McCooey’s, a woman paralyzed by polio who my mother would take me to visit. I’d stare at that painting and fantasize about being there instead of where I was, with the boring adult conversation, which was always the same. Now I am one of those boring adults talking instead of escaping into a painting.

When I was a kid, I thought art and songs and movies were real. Then I grew up and grew money and influence, and art became symbolic. Everything became symbolic. And complex, and distant. Now, in this room where I can’t see and can’t impress anyone, nothing is symbolic, everything is easy, and I can walk into paintings again.

2.

I feel like it’s bedtime, though it could be anytime. I don’t know how to behave here. There’s no habit, no feedback, no punishment or reward to show me what is expected of me. The same way I can’t inspect the food, can only eat it, I can’t inspect the life I’m leading right now, can only live it. Well, I’m not leading it. I’m lying in it. In the light, you get to choose from a menu at a restaurant, and you choose from the menu of life—what kind of friend will you be that day, what hobbies will you learn that year. There’s only the one thing here. And it’s eternal.

I know this: I’ve spent way too many of my first twenty-four hours being bitter about Bruno, filling this room with lists of all the ways he is chaotic and selfish. He’s not even doing anything to me right now! I give so much energy to fighting with him when we are in the same room, how disappointing that I’m continuing the fight when we aren’t. Obsession is an invasive species of the mind. You can reimagine events so constantly it chokes out all the other little events that are trying to happen. I’m ashamed. I’m having to face that it is me choosing to live my life in struggle. I gotta stop telling myself it will be better “when …” There is no “when.” There only is.

Auuugh, gawd, listen to me holding forth and forth to my audience of none! I can’t stand myself.

3.

It’s hard to tell sleeping from waking in here. But I do recognize what a nightmare is, and I just had one, so I must have been asleep. In it Bruno kept turning the light on and telling me about something happening—animals replicating. I said, “Leave me be. They’re going to replicate whether I’m there to see it or not, and right now I’m on my dark retreat.” But he wouldn’t stop, so finally I went to see these animals replicating. I could hear something moving behind an old built-in bookcase, and I yanked desperately at it to free the creature, and pulled out chunks of what I realized was the original Bruno. The pieces were falling apart in my hands like rotted food, while the replicant Bruno yelled and gesticulated at me. It was so horrible it woke me up. It was horrible because it’s true.

We categorize nightmares as unreal because we, as a species, don’t “believe” in sleep. I mean as a landscape, its own real place. Perhaps I should reverse it, stop paying attention to what people say when I’m awake and instead believe what they say in my sleep.

4.

Harry Styles lyrics running through my mind: Stop your crying, have the time of your life, gotta get away from here, you’re not really good, everything will be all right.

5.

Came here to report that I was walking in the snow in a black snowsuit. I saw an oval space in the snow and curled up in it. I pulled snow over me like a blanket and it kept me warm. I thought, Why didn’t I ever realize we don’t have to be cold?

I don’t know why I keep seeing snow when I know it’s not winter out there. I guess because snow is white, and I’m hungry for the opposite of blackness.

6.

I feel my separateness. I feel like a tiny piece of gravel cutting into the heel of the darkness. The darkness is whole and I am just an aberration. I don’t matter. I have never had that thought before! How terrible it feels! How I wish I could talk to someone or look at homes on Zillow or walk the dog—anything to tell me that it’s the darkness that’s insignificant and fleeting, not me. Oh God, it’s awful in here! I can’t even fantasize about the other activities on the farm that I might do when I get out of here, like paragliding, weather permitting, because it won’t be me out there paragliding. It will be Lisa Light. Lisa In Motion. I don’t know that person. Me Now is stuck in here forever. Without all of Lisa Light’s scurrying about, I have come to the terrible realization that—get ready for it: There is no God. Sigh.

I thought God was everything and so that meant me, too. But now I see there is no “one life” that I’m a part of. I am a minor character in someone else’s plot. Someone else being this darkness, this stillness.

Day Three

1.

When you chew, you hear yourself. I don’t want to hear myself chewing! And there’s nothing I can do about it! Chomp, chomp-chomp-chomp-chomp-chomp. I ate yesterday’s unknown fruit for breakfast, and oh my goodness! The squishing and the chomping. I could hear the juice squirting! I don’t want to know all the machinations of the human sausage factory. I can’t handle it. This awareness of process. I want to live in a dream, flitting about. Just do your jobs, body, and don’t tell me about it.

2.

I hallucinated a church bell. I think it really did ring a few times—the only sound loud enough to penetrate these castle walls—but then I heard it two hundred and fifty more times. I counted. I started experimenting with trying to stop and start it, and I could. So it probably wasn’t real, but you never know with Italians and how much they love Jesus—two hundred and fifty could be exactly the right amount of times to ring His bell.

3.

Okay, 113 church bell tollings from the opposite direction. Then twenty more from the first direction. It’s getting irritating because I don’t know which world I’m in. I’m also starting to hear something like the ticking of a clock or horse hooves on cobblestones in the distance. You know how when the radio’s set at the lowest volume in your car, you can’t quite hear music but you know it’s there? You can sort of feel it? It drives me crazy. This sound is like that, only I can’t adjust the volume. It could be what John Cage describes as the treble hum of our nervous system above the base thump of pumping blood.

Maybe there’s a whole lot of sounds all the time that we never hear. Maybe I’m hearing a tree growing right outside my window.

4.

You hear about vicious killers in solitary confinement feeling tender toward a rat in their cell, or an insect. There’s a fly or a bee or a mosquito in here with me … Pretty sure it’s a fly, a big horsefly, and I feel tender toward it. It really breaks up the monotony. It’s doing things, moving around, living. I feel united with it against the darkness. We’re two of a kind!

5.

It feels much later than one o’clock. I’m so distressed. Antonello hasn’t come with my food. I don’t care about the food, but I care about the coming to my door.

My insect is gone too. Maybe it died.

6.

I think it’s night, but I can’t sleep because I’m seeing so much light. Bright light above, below, within. Drive-in movie screens with bright white movies playing. Walls of graffiti, all the words white white white. And silver. If I close my eyes, it doesn’t stop it because the light is coming from inside me. You guys, there is all this light inside my brain. I’ve stayed in here too long.

Day Four

1.

It’s the fourth day. I think. It feels like the fourth year. My muscles have atrophied. I get dizzy when I stand. It’s weird to walk. The floorboards sort of … float up to meet my feet. I imagine they must actually move an infinitesimal amount each time we walk on them. Everything must, even stone. Every single thing is coated in membrane—that is the nature of things. I simply haven’t been sensitive enough to pick up on the motion of objects till now. But yes, everything is in motion. Each time my foot lands, I can feel the give, and the springing back, of the floorboards. It’s disconcerting. I’ve always thought of myself as walking on a surface, not with it. In fact, the floorboards are walking on me too.

2.

I don’t like to think of other people having been in this room or coming here in the future. We are not welcome, with our disruptive thoughts cutting the one cool Everything into pieces. At first I thought the darkness didn’t care about me, but I was forgetting we care a lot about a splinter stuck in our finger. The darkness might try to tweeze me out! Or drive me mad with terror or boredom so that I self-eject. I have always been good at camouflaging myself, so thus far I have eluded detection. But if someone else came into the room—even if I think about somebody else here—the darkness might sense their presence, even my made-up person’s presence, because they wouldn’t be coated in darkness camo like me. And then, after the darkness was done with my made-up person, it might scan for more intruders and find me! Oh ho, now I’m all spooked out.

3.

I took a shower. It was nice. I took off my clothes and stood under the showerhead (I felt for it to figure out where to stand) and turned on the faucet, and what happens next is totally predictable when you perform those three operations … yet it surprised me as if it just happened on its own, as if I didn’t do anything at all to create that wetness.

Another surprise came when I got out of the shower. Earlier, I’d felt around for the cool basin and left my towel in the sink. I thought I would be able to find it there easily. Turns out that wasn’t the sink. Can you guess what it was?

I was careful putting my clothes on, because it’s dangerous to drop things in the dark. They move. I lost a sock in the night. I took both of them off and dropped them by the bed when I went to not-sleep. This morning only one remained. I was on my hands and knees everywhere feeling for its brother. Somehow it got to the middle of the room!

Trying to find the right place to comb the part in my hair so that it doesn’t dry with my cowlick gone haywire without looking in a mirror was precarious.

Anything done tentatively is exquisite. When forced to move slowly, to grope for one’s bearings, we become fragile, delicate. We come across small beauties that normally we rush past and trample. Feeling uncertain opens the possibility of surprise. Surprise is not enjoyment. It’s awe. Humility. Surprise is being outsmarted by the universe, and we glory in our smallness because it allows us to be teased in a loving way by the ubiquitous.

This feeling was perfectly captured by a travel guide who took a duchess to see the Grand Canyon: “Upon standing on its rim and encountering its vastness for the first time, the duchess flung her arms open and screamed.”

4.

Every time I feel my way along the soft stone wall, a nanoscopic layer falls off. How many feels, over thousands of years, before this stone wears clean away, and I can plunge my hand through the wall into the outside?

5.

The electricity bill for this cottage must be so low. Ah ha ha!

6.

Note to self: Look up the meaning of desultory. I do believe this pillow is “desultory.” It’s a wet noodle pillow.

***

***

And that was my last transmission from the dark. I tried to gauge when it was 10 P.M., so I would exit at the same hour I entered, but I miscalculated, because when I wobbled out of my room I was hit in the face with some hazy afternoon sunrays. All the better to witness the world with.

7.

Oh my God. All that is out here! Fruit trees, a mother cat with kittens, horses whinnying, stone houses with no doors in the doorframes, no windows in the window openings, no floor but dirt. These are probably those crumbling Italian countryside houses you hear about that you can buy for a dollar. Of course now I really want to buy one and stay here forever. Hey, I bet that’s the father cat there. There’s so much dimension out here. I don’t know why I ever went indoors! This world is glorious! I gotta take it while I can have it! Because—you guys—I’ve gotten a glimpse of what’s to come. Death is heavy, man. Literally. It hurt my chest lying on me. And the loss of God got me right in the mouth. I can feel with my tongue a bunch of canker sores inside my lips and one of my cheeks.

And that’s where the recording stops, with a small scream from the first human being I came across, an old-fashioned, lots-of-layers dress despite the warmth of the day, woman. I’d forgotten to look at myself before emerging. I must have been a sight. All pale, with my legs moving funny. Puffing my lower face out so the cankers didn’t scrape against my teeth while I muttered into the recorder. I wore sunglasses even though by now it was twilight, and a later (shocking) glance in the mirror revealed that my cowlick pointed straight to the moon.

Day Five

I met the guests at dinner, and they were indeed all new people—from Scotland, Spain, Australia, Ireland, Poland, and England. They were curious about what happened in the dark. After hearing what I went through, a couple of them wanted to try it out; the rest said over their dead body. When I got to the part about losing God in there, a vibrant gay handsome Australian actor/content creator named Robbie cried, “I found Him!”

He whipped out his phone and read what he had just written about the year since his mother died and he found out his Argentinian fiancé was using him for a visa, so he ran away to Thailand and did ayahuasca and breath work and something with three initials that unblocked trauma quite traumatically, it seems, as evidenced in the video he showed me of himself in little black underwear shaking like someone being exorcised.

He asked what I do and then he googled my name and was yelling SUCKDOG?!?! The name of my band from a million years ago. Seven faces stopped eating and they, too, demanded an explanation. I said, “It was the eighties.” That seemed to satisfy everyone.

Robbie was vegan and alcohol-free while he lived in Thailand, until he came to Italy and someone offered him a glass from a fifty-thousand-dollar bottle of wine. I asked if it tasted like $50K. He said no, it tasted like $5K: He only had one glass.

It is so good to hear other people’s jokes and not just your own.

Antonello explained how they make cheese on the farm the old-fashioned way. They slaughter a lamb and use its intestines (I think) to make the milk bubble (I think) as it’s churned instead of the chemicals that Americans and now the rest of the world use instead. They make everything on this farm themselves with absolutely nothing from stores. Nothing modern whatsoever. Robbie said he learned from Antonello that agriculture is exactly the same as spirituality.

Robbie and I spilled it all—utterly indiscreet. What a relief it was to make sense to someone! Conversation with him is not the high wire act it is for me in France. Even after three years of living there, Parisians find me inexplicable, and it kind of hurts my feelings. Everything there is undertone and nuance that I just don’t get. I don’t want to get it! It feels like a game with rules written in invisible ink, where someone has to win and someone has to lose. I don’t want to do either! I want to know and be known and laugh a lot at stupid stuff—but not at how stupid other people are. Robbie’s the same. We love juvenile movies like Airplane! Robbie just says anything, like I used to do. No context, no modesty, fast and loose with facts. He thinks I’m normal. I am normal!

In my exuberance at being able to speak without effort, at not having to pay attention to another culture’s manners, at not trying to predict and disarm my husband’s next mood, I maybe went overboard: I accidentally ate an entire tureen of lentils that I thought were for me, but it turns out were for the whole table.

Day Six

I am so emotional since regaining the world of light and sound that comes from sources other than me. When Robbie didn’t appear at breakfast or the afternoon activity, I was like an actress in a Mexican soap opera twice betrayed. When he showed up at dinner, I was so joyful I forgot I’d ever been anything else until … this redhead came late and enthralled the table with tales of her past life when she was a Chinese woman who loved her husband and he didn’t love her and she got hooked on opium because of it and died giving birth to their sixth child … Robbie joined in with one sentence only: “A shaman told me my spirit animal is a turtle.” “Turtles are so wise,” the redhead noted, and began giving a tutorial on the subject. “Turtles are so cute,” I interrupted, “with their little E.T. heads.” “Little E.T. heads!?” cried Robbie, and we both burst out laughing while the redhead remained stone-faced. Touchdown! There’s not room enough in Robbie for two new best friends.

The redhead shot back that my marriage was unsustainable. I said, “Well it is or it isn’t, I don’t really care which.” But inside I was thinking, I don’t think you’re one to decide about some else’s marriage, after having six kids in a row on opium until you died.

Day Seven

To get to breakfast, activities, or dinner, I’d walk to the common area from my little stone house (dark no more—all you have to do is turn on the lights … and it shrinks! I can’t believe how huge my room got in the dark!) down a hilly, winding, lonesome road flanked by vineyards twenty minutes each way. Dogs would bark my coming as if passing a torch, alerting the next dog two minutes away of the demon who dared step foot on their land. When they’d discover—a hurtful surprise each time—that they couldn’t break through their fences and maul me, they did the next best thing and peed at me. A chorus of urine streams. I never shared the road with another human or vehicle … just me and the grapes and olives and figs and birds … until this morning, my last (maybe my last ever, I thought), when an escaped German shepherd trotted straight at me and I thought, Feel no fear, feel no fear, feel no fear. It worked: He let me pass. I feel more in sync with everything in this world since I found out what it’s like to be just with myself. To meet even an attack dog is welcome in its not-me-ness.

Enormous pink ribbons tied to the gates of two houses across from each other at the entrance to the farm proclaimed that each had been blessed with the birth of a daughter. Since no one ever leaves here, I imagined these two little girls growing up together and then growing old together. I’d seen their grandmas a few times, with their plain clothes, plain faces, plain attitudes, bending over to yank weeds or do some other earth business; slow, placid, belonging. That will be these babies someday.

For my last breakfast, I asked for cold water, and the staff acted like I was a zoo animal who broke out, hitchhiked to a diner, and demanded crickets. “Antonello won’t let us have cold water in the morning as it’s not good for the health,” a French guest explained. “ ‘You don’t wash dirty greasy dishes in cold water,’ ” she quoted.

“I don’t wake up as a dirty greasy dish,” I protested.

An edict of Antonello’s can be griped at, but it cannot be overturned. I drank my water tepid.

Robbie was steadily sucking down coffee. “I didn’t sleep at all last night,” he said. “I was lying on the hammock under three blankets staring at the full moon and it came to me: You met Lisa for a reason.” He decided that reason was to make me the scriptwriter for his TV dramedy about his mother coming back from the dead to give him gay dating advice. I fly to Thailand in January to begin shooting!

Lisa Carver published the nineties zine Rollerderby. She lives in Pittsburgh and wants a divorce. Her latest book is Lover of Leaving, and her Patreon is called Philosophy Hour.

May 13, 2025

There Is Another World, But It Is This One

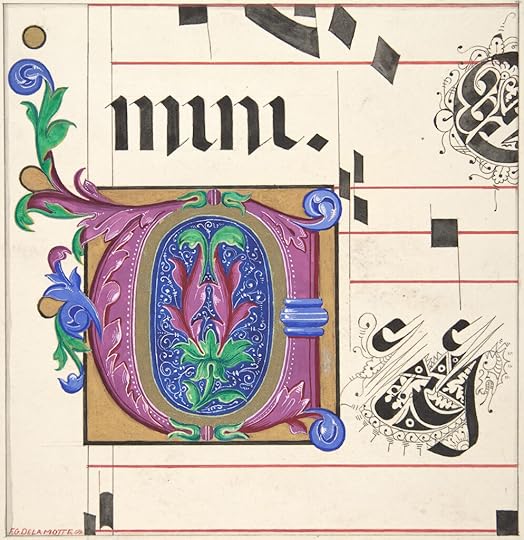

Freeman Gage Delamotte, Illuminated Initial from Hymnal, 1830–1862. Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Elisha Whittelsey Collection, The Elisha Whittelsey Fund, 1966. Public domain.

1. Before my mum died I was a rain guy. Weren’t we all? Now I get it: the wind. Its shoulders. Smooth and deep as a bowl. Like a lullaby about a big old brush. Glowing, of course, but on the inside, far away from our world. Who could possibly go through the death of their mother and come out the other side anything less than a total idiot for wind? It is the golden whistle. God’s first attempt at a dinosaur. A holiday from all that silence and color.

2. In her final text messages, sent the night before she died, my mum invites her friend over for sex, a reminder that two things can sometimes meet the same need.

3. The invitation to sex in the midst of death is my mum at her most desperate, so it’s also my mum as I most love her, miss her. Like the embroideries she made of my stepdad’s poems when he was dying of cancer, it weaves together death and love into something that can be shared, a made thing amid all the unmaking.

4. My mum always had a needlework going, though she called them her tapestries. Big old castles were a particular specialty. So were grumpy bowls of fruit. But what I remember most about her tapestries are the backs, that mess of colored thread that looks like a vomited version of the castle or sunset or pineapple on the front. When you live with a tapestry maker (tapestrist? tapestreur?) you get used to seeing this frayed mass of color, which they carry around with them at all times like a small shield. The hours my mum spent tapestrating appeared to be spent inspecting the reverse of a mysterious hairy object.

5. She had a funny idea of fun, my mum. As a librarian and schoolteacher, she had a habit of parceling off excitement into manageable packets called “activities.” We didn’t “do stuff,” we completed “projects.” She treated fun as something that needed to be safeguarded, as though there were only so much of it. Or as though it were something there was only one of, like a library book that had to be returned before it could be borrowed again. As one of four children, I seemed to spend a lot of time waiting for permission to access fun, which was always on hold somewhere else, or stuck in some administrative hinterland between borrowings.

6. I felt this frustration all the way into my twenties, but by then the frustration had moldered into contempt. I was ashamed of her for making fun unfun. I was embarrassed by her difficulty being happy. What I failed to understand is that my mum’s librification of fun had been a compromise. Like so many mothers, she was the scaffold upon which other people’s pleasures secretly depended. By organizing her fun, she was trying to protect it from the corroding forces of everyone else’s chaotic enjoyment.

7. After David died I watched Mum flourish through a kind of second adolescence. She colored her hair, bought a guitar, went traveling. On New Year’s Eve she emailed to say she was staying in an Ecuadorian “jungle lodge.” A few weeks later she wrote again to let us know she was “on a bus to the Grand Canyon.” Finally she quit her job and announced that she was leaving the UK for good. She was moving to a small, treeless island off the southern coast of Argentina, where there are more penguins than people. In our conversations it was always this odd fact about the penguins that she emphasized.