The Paris Review's Blog, page 12

March 20, 2025

“A Threat to Mental Health”: How to Read Rocks

Richard Sharpe Shaver, born 1907 in Berwick, Pennsylvania, became a national sensation in the forties with his dramatic accounts of a highly advanced civilization that inhabited Earth in prehistoric times. An itinerant Midwesterner, he’d been employed as a landscape gardener, a figure model for art classes, and a welder at Henry Ford’s original auto plant. He gained public attention as a writer who asserted that descendants of those early beings still live in hidden underground cities, where they wield terrifying technology capable of controlling thoughts. Many readers agreed with Shaver, and a splashy controversy ensued.

Public fascination with his writings subsided during the fifties, but Shaver continued searching for evidence of a great bygone civilization. In about 1960, while living in rural Wisconsin, Shaver formulated a hypothesis that would captivate him for the balance of his life: some stones are ancient books, designed and fabricated by people of the remote past using technology that surpasses anything known today. He identified complex pictorial content in these “rock books.” Images reveal themselves at every angle and every level of magnification and are layered throughout each rock. Graphic symbols and lettering also appear in what he called “the most fascinating exhibition of virtuosity in art existent on earth.”

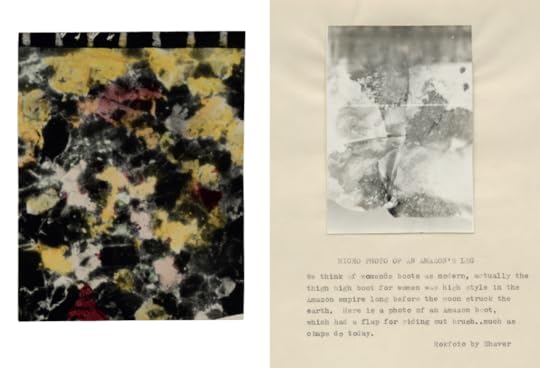

Frustrated that the equipment needed to fully decipher the dense rock books was lost to time, Shaver undertook strategies to make at least a fraction of the books’ content clearly visible. Initially, he made drawings and paintings of images he found in the rocks, developing idiosyncratic techniques to project a slice of rock onto cardboard or a wooden plank. Shaver also produced conventional black-and-white photos using 35 mm film, often showing a cross section of rock alongside a ruler or a coin to indicate scale. Sometimes he highlighted imagery by hand coloring the prints with felt pens. He attached photos to typewriter paper where he added commentary: he describes the rock books, interprets images, details his photo techniques, and expresses disappointment at the conspicuous lack of academic or journalistic interest in his findings.

Shaver and his wife, Dorothy, moved in 1963 to Summit, Arkansas, where he established his Rock House Studio on their small property. There, in addition to painting, he processed and printed film. His efforts at illuminating the rock books moved away from painting and toward photography in his final years. That shift may have been influenced by his perception that viewers interpreted the paintings as a product of his imagination rather than an objective record of ancient artifacts. Shaver wrote, “People will believe photos and won’t believe drawings or paintings… the camera wins, by being honest. Which doesn’t say much for artist’s honesty, I guess. We try… but people think we lie.”

Shaver made small books on paper at his studio—some illustrated with his drawings or collages of rock photos—which he produced with a local printer. He kept his manuscripts in file folders with colorful hand-lettered titles. As many as twenty booklets were planned; five of them, plus a brochure about “pre-deluge art stones,” are known to have seen print. Each one views the prehistoric library in stone from a different angle. “Giant Evening Wings” is named after swarming ape-bats that threatened the ancient Amazons; “Blue Mansions” features the undersea Mer people; “The Vermin from Space!!!” paints a bleak picture involving rock books, mind control, and flying saucer sightings: “We are a remnant of an ancient race, adrift on a dying world and the parasites of space circle us, looking for a place to sink in their sucking tube.”

In contrast with faulty reconstructions of human history from bone fragments, “from now on … we can read the books written by people who actually lived the pre-history.” He describes how rock books, which once filled great libraries, were tossed across the world by a cataclysmic deluge that “burst the ancient libraries like ripe nuts. The seeds of ages of learning were scattered over the earth. They await only fertile mental soil to grow again.”

***

To approach Shaver’s rock photography—a process he sometimes referred to as “rokfogo”—it is useful to consider his earlier success as a writer and to introduce Ray Palmer, the magazine editor who became an inextricable part of his public life. Ray Palmer was, by the early forties, editor of Amazing Stories, the first American science fiction magazine, and a line of other pulp fiction periodicals published by Ziff-Davis in Chicago, Illinois. In addition to fiction, Palmer’s Amazing Stories included regular sections on “Scientific Mysteries,” “Scientific Oddities,” and a wide-ranging forum for letters to the editor under the banner “Discussions.” In the January 1944 issue of Amazing Stories, a letter signed by S. Shaver appears with the headline “An Ancient Language?” It included a glossary that attached meanings to each letter of the English alphabet. (The excerpt quoted below is drawn from a later, expanded manuscript of his glossary, probably written in the seventies. Shaver’s “Alphabet of the Ancients” remained important to him for decades; it was often known as the “Mantong” alphabet.)

A stands for animal

B stands for be, to exist… to be.

C stands for vision, and the history of C as it relates to the Greek-wave-pattern is interesting and backs up the amphibious or fish-lizard source of the man-shape.

C also meant “sea-water clear water.. water in which vision was possible..thus “Clear as crystal” means understanding as in “CON” for see-on ..used today in words like conning tower…

Thus today.. I see means I understand…

Shaver wrote, “Am sending you this in hopes you will insert in an issue to keep it from dying with me… This language seems to me to be definite proof of the Atlantean legend… This is perhaps the only copy of this language in existence, and it represents my work over a long period of years… I need a little encouragement.”

Response to the letter was so encouraging that Shaver soon became a featured author in the magazine. In his 1975 autobiography, Ray Palmer writes, “Many hundreds of readers’ letters came in, and the net result was a query to Richard S. Shaver asking him where he got his alphabet. The answer was in the form of a 10,000 word ‘manuscript’ typed with what was certainly the ultimate in non-ability at the typewriter and entitled, ‘A Warning to Future Man.’ ” According to Palmer, Shaver’s text was not a short story but a long letter detailing his beliefs about the true history of intelligent life on Earth and the terrible hidden reality that humanity currently faced. Palmer saw it as a “jumping off place” for salable stories. “Using Mr. Shaver’s strange letter-manuscript as a basis, I wrote a thirty-one-thousand-word story which I titled ‘I Remember Lemuria!’ ” Shaver disputed Palmer’s claim of authorship, but regardless, the story was featured on the cover of the March 1945 issue of Amazing Stories.

“I Remember Lemuria!” is set in an underground civilization where the protagonist, an aspiring painter, is humiliated by a brutal art critique. On the advice of his artistic mentor, he sets off in search of knowledge. Unusual for the pulp fiction of its era, the story includes footnotes that elaborate Shaver’s scientific claims. Also unusual is the author’s preface, in which he writes, “To me it is tragic that the only way I can tell my story is in the guise of fiction.”

Shaver insisted that his tales, however outlandish they may seem, were true and grounded in firsthand experience. According to Shaver, sadistic creatures that live inside the earth manipulate human society. They torture and enslave, project voices and thoughts into people’s minds, and induce death, mayhem, and war. Known as Dero—short for degenerate or detrimental robots—these are the mentally impaired descendants of a super-sophisticated civilization that occupied Earth eons ago. Those ancients discovered they were being poisoned by the rays of Earth’s sun, so they built cities deep underground. Ultimately, they departed Earth in favor of a planet with a more accommodating atmosphere. A few were left behind in the cavern cities (the “abandondero”), and their powerful machinery remained underground as well, including the “ray” devices that the Dero use to project voices into the minds of contemporary humans. A smaller population also exists underground: the benevolent Tero. This group did not suffer the mental and moral decline that shaped generations of Dero. It was the Tero who guided Shaver into the under-ground cities and educated him about Earth’s true cultural history. Tero protected him in the face of the Dero, such that Shaver, unique among men, could return to the surface to tell his story.

Touted by Palmer as “The Shaver Mystery,” these warnings about a legion of mind-manipulating evildoers found a receptive audience in the immediate aftermath of World War II; readers were attuned to reports of diabolical enemies and secret weapons. Shaver’s accounts also resonated with those who were troubled by intrusive voices or antisocial impulses. Many wrote to express support for his claims; some affirmed that they had personally heard voices or encountered malevolent Dero. According to Palmer, demand for the magazine grew explosively in response to Shaver’s stories.

The groundswell of enthusiasm extended beyond the pages of Amazing Stories. Shaver Mystery fans set out in search of entrances to the underground cities and attempted to build working models of the Dero’s fantastic machines. Earnest mimeographed publications, such as “The Shaver Mystery Club Letterzine,” appeared. A separate Shaver Mystery Magazine was launched. The Shaver Mystery soon met with opposition, some of it from fans committed to elevating the literary reputation of science fiction. A resolution at the 1947 World Science Fiction Convention condemned “The Shaver Mythos and related absurdities” as a threat to mental health and a “perversion of fantasy fiction.” The controversy drew mention in general-circulation magazines, including Life and Harper’s. The publishers of Amazing Stories put an end to the Shaver series in 1949.

***

Shaver anticipated that his audience would miss the point of the rock books because of the Dero’s baleful influence on their thoughts. In The Hidden World, a sixteen-volume series later published by Palmer, Shaver writes: “Please, dear victimized and brutally mistreated people that you are, PLEASE wake up! No matter what cavern idiots tell you in the back of your mind, look at these stones and understand what they are! How can anyone ignore these marvelous ancient picture books?”

Richard Shaver died in Arkansas in 1975. He produced the following photos and texts at his Rock House Studio during the last decade of his life.

I am forever explaining prints like this photo of Viet Nam rock to someone not at all willing to be explained to.

The rock saw has cross-sectioned a series of photo-like pictorials which run in 2 to 4 mm. sizes in scan-strips in the rock. IF you could use a penetrative light instead of ordinary light you would see and understand that such pictures are pictures..but the saw cross-sections them. Thus they are mutilated and s distorted..like bits torn out of an encyclopedia they’re unreadable and un-understandable.

HOWEVER they are very interesting glimpses of an ancient way of life and and a forgotten culture and language now quite unknown. Once it was world wide..now it lies forgotten and ignored as “mere rocks” on the landscape that “should” be cleaned off and thrown away..and usually are.

We destroy all these rock books by making them into road gravel… and what were once treasured libraries containing the lore of millions of years of study and mental effort..are made into black top roads that go no-where for no real purpose.

Our whole civilization is very busily rushing about to go no-where to no particular purpose and most of the careening cars are in fact making trips totally unnecessary is something you know.

I get quite a lot of requests for pictures of rock … of this type. I send them small ones made like this on sheets of Zerox … or sheets of proofs in 35mm size. to give them a broad idea of the look of a lot of the pictures. It is too bad we dont have available the right combinations of lenses or lenses and mirrors to unscramble these 3-di pictures from the far past. But they are fascinating anyway. Lots of these rock books contain children’s stories..one can recognize old classics like Puss-in-Boots or Red Riding Hood. So one deduces that rock magnification gadgetry was available in every home … and such could be the case today if we really had some enterprise in our financial empires.

WEIRD AND WONDERFUL ART

in the rock books can be mistaken for “mere” accidentals only by a superficial eye and careless mind refusing to look carefully.

When one has studied enough of them, the rock books begin to assume their true stature… the greatest of all books extant on earth. How to get this across toe a modern ignoramus, shorn of all right to reason and learn by a misguided and sabotaged school system…is a genuine problem. That 3-di art means a 3-di mind, and is not to be appreciated in one glance any more than 3-di chess can be learned in one sitting.

Such great features are the faces of the immortals, practically, with minds active over immense periods of time, and their rock art is the art of saying much in little space and with few symbols.

Their bodies seem double-jointed, for they were…amphibious races and space races ..yet their faces are the faces of our ancestors, as wells the faces of our Gods. The little figures with the big tell the story in gesture, sometimes they are musical score.

Accenting a B&W print with colored pens gives you faces like this, multiples of faces in series of sizes… what I am supposed to do about it after I tell them I can never quite figure. To the average Joe its an insane idea, because he never heard of any “previous civilization” the whole thing is some sort of delusion, I suppose. If I dont accent the prints, he “Cant see them” and if I DO accent them, I am “making them from my imagination”. Since I cant win, I dont try very hard.

BUT the rock books a re a vast library from antiquity, of inestimable value. Those people had solved ecological problems like overcrowding. They lived underground, farmed the whole surface of the earth. They lived IN the oceans, too, as Mers and “Mermaids”. We think of mermaids as a mad sort of myth, but in fact they were our direct ancestors.

What to do about universal ignorance of man’s beginnings is too much problem for me. I cant even sell a rock book! (“no sich animal”.)

Adapted from Richard Sharpe Shaver: Some Stones Are Ancient Books, edited by Christine Burgin and Andy Lampert and with an introduction by Brian Tucker, to be published by Further Reading Library in April.

Brian Tucker is a professor of art at Pasadena City College who has researched the life and work of Richard Shaver since 1989. As an artist, he has exhibited work based on the story of Shaver and Palmer at venues including the California Institute of the Arts and Curt Marcus Gallery in New York City.

March 17, 2025

Is Robert Frost Even a Good Poet?

Robert Frost, between 1910 and 1920, via Library of Congress. Public domain.

Though he is most often associated with New England, Robert Frost (1874–1963) was born in San Francisco. He dropped out of both Dartmouth and Harvard, taught school like his mother did before him, and became a farmer, the sleeping-in kind, since he wrote at night. He didn’t publish a book of poems until he was thirty-nine, but went on to win four Pulitzers. By the end of his life, he could fill a stadium for a reading. Frost is still well known, occasionally even beloved, but is significantly more known than he is read. When he is included in a university poetry course, it is often as an example of the conservative poetics from which his more provocative, difficult modernist contemporaries (T. S. Eliot, Ezra Pound) sought to depart. A few years ago, I set out to write a dissertation on Frost, hoping that sustained focus on his work might allow me to discover a critical language for talking about accessible poems, the kind anybody could read. My research kept turning up interpretations of Frost’s poems that were smart, even beautiful, but were missing something. It was not until I found the journalist Adam Plunkett’s work that I was able to see what that was. “We misunderstand him,” Plunkett wrote of Frost in a 2014 piece for The New Republic, “when, in studying him, we disregard our unstudied reactions.” We love to point out, for example, that the two roads in “The Road Not Taken” are worn “really about the same,” as though to say that your first impression of the poem—as about choosing the road “less traveled by”—was wrong. For Plunkett, “the wrongness is part of the point, the temptation into believing, as in the speaker’s impression of himself, that you could form yourself by your decisions … as the master of your fate.” Subsequent googling told me that Plunkett had been publishing essays and reviews, mostly about poetry, rather regularly until 2015, when he seemed to have fallen off the edge of the internet. After many search configurations, including “adam plunkett obituary,” I found a brief bio that said he was working on a new critical biography of Robert Frost, the book that would become Love and Need: The Life of Robert Frost’s Poetry, recently published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux. He responded to my October 2022 email, explaining that he had “stopped writing much journalism as of 2015 so as to avoid distractions from a book project that I thought would take an almost unfathomably long time—two years or perhaps even three. Seven years later, I’m doing my best to polish the third draft.” Just as Plunkett is the unique reader of Frost interested in both our studied and unstudied reactions to the poems, he is the unique biographer of Frost whose work is neither hagiography nor slander. His is a middle way of which, I think, Frost would approve. Recently, we talked on the phone about why Frost has become uncool, Greek drama, and, relatedly, the soul.

INTERVIEWER

What makes you and Frost a good fit?

ADAM PLUNKETT

I tend not to think that stuff other people think is obvious is obvious.

INTERVIEWER

And Frost is obvious?

PLUNKETT

Everyone feels like they have some sense of Frost. Everyone knows a poem or two. That kind of overexposure lends an aspect of at least apparent obviousness. But there’s another aspect, too, which is that many people read Frost for the first time as children and associate him with an early stage of life. There’s a cultural association between the time of exposure and the level of sophistication. You’d sound pretty vulgar if you said, Oh, yeah, I learned to play Bach when I was thirteen—that’s easy stuff. But people really do make pronouncements like that about literature. Someone I met a few years ago, a big poetry person, just could not believe that an adult would spend years of his life thinking about Robert Frost. To her it seemed like doing a Ph.D. in simple algebra.

INTERVIEWER

What is it about his poems that makes people feel that way?

PLUNKETT

They understand the words. People read the poems and think they know what the poems mean. Even when they think that a poem doesn’t mean exactly what it says on the surface, they think they understand the secondary meaning, too. The dark woods in “Stopping by Woods” tend to strike readers as also something other than physical woods, something deeper, which often gets reduced to “death symbolism” but is much richer and subtler than death alone. There’s both a surface coherence and a sense that the thing that’s hinted at beyond the surface is familiar.

INTERVIEWER

Would you say that there’s a direct correlation between Frost’s familiarity and the fact that he’s fallen so out of favor with people who are serious about poetry today?

PLUNKETT

One thing that has been interesting about working on Frost is that so many people come out of the woodwork who turn out to be incredible admirers of him. But he was really far outside of the circle of poets who I was taught when I was in college. This has a lot to do with the fetishization of what’s difficult, especially as both poetry and criticism professionalized. Frost’s difficulties are of a different kind. His genius is harder to see. A lot of his poems tap into something like common culture and common problems, these very basic conflicts that were also the stuff of Greek drama. Those difficulties are different from that of a line break, and they are not the favored difficulties of professional criticism.

INTERVIEWER

How do you think Frost’s difficulty is like that of Greek drama?

PLUNKETT

Take a poem like “Mending Wall.” You have two characters, the speaker and his neighbor, who embody these different ways of ordering space. When they get together, as they do once a year in spring, to mend the stone wall between their properties, the speaker begins to feel that there’s something unnecessary and even untoward about maintaining this boundary. He suggests as much to his neighbor, who just continues to repeat an old folk saying—“Good fences make good neighbors.” If you sit with it, you can see that the poem has the aspect of a Greek drama. It gets down to a conflict, like the one in Antigone, between love and duty, or between obligations to the family versus obligations to the state. You realize that you’re meant to take the speaker’s descriptions, especially of his neighbor, with a bit more than a grain of salt, and that there’s a tremendous amount of balance between these two points of view. It’s an unresolvable problem, how to organize human society. How does a political body at any scale manage borders? Some people may think they have the answer, but I think that if you have any degree of certainty about it, you don’t really understand the problem. I would say the same about reading Frost’s poetry.

INTERVIEWER

That if you think you have the answer, you don’t have it?

PLUNKETT

You don’t quite understand the problem.

INTERVIEWER

You might understand the poem’s language but still not grasp the real-world problem that it describes.

PLUNKETT

Absolutely. Frost’s mind really did work by trying to strip ordinary problems down to the deepest tensions underlying them. That doesn’t mean that he was always wise. He could be a complete bore, and he could be extremely stubborn and crass and prejudiced, especially in his old age. That people tend to rest in easy interpretations of his poems comes in part from the idea that the man who was writing the poetry was in some way simple. But Frost’s simplicity has much more in common with Horace’s phrase “the art that hides art” than with the simplicity of somebody repeating old folk sayings. Yet his sophistication is not the same as that of the intelligentsia. And that’s part of what makes Frost so interesting, that there’s a conflict within him between the life of the mind and a kind of embodied, distributed knowledge that he did not think correlated well with higher education, nor, really, with any of the standard American systems for conferring sophistication. Part of what makes the poetry so good, when it’s good, is that he has a tremendous amount of respect for the sort of person who knows how to mend a wall.

INTERVIEWER

Would you call him a populist?

PLUNKETT

I actually think that it would be a grave mistake to call Frost a populist. Frost was an anti-elitist, not a populist. He even distinguished himself from Carl Sandburg, a genuinely populist contemporary of his, on exactly these grounds—“Carl Sandburg says, ‘The people, yes.’ I say, ‘The people, yes and no.’ ” He also didn’t really think in terms of social class as we understand it. Frost just did not have a sense of himself as in any way superior to people who had less education. In a way that could not be more relevant to the world we’re living in right now, he actually, without condescension or idealization, learned from people who had different backgrounds. He found things to admire in them—different sets of virtues, and certainly different sets of vices than the people who he wound up socializing with once he’d found success. I’d add that, as I see the arc of Frost’s career, the more he’s institutionalized, the worse his writing gets. The more access he has to a privileged, cosmopolitan, educated world, the more that world starts to crowd out his other exposures, and there’s a loss there.

INTERVIEWER

Frost was an important early example of the way a poet could inhabit the university, in roles that many American poets depend on for their livelihood today—he was the original writer in residence, or visiting writer, or professor of the practice, that kind of thing. Yet he was so critical of higher education. How do you think about that tension?

PLUNKETT

Frost had general misgivings about the institutionalization of anything, whether that was an act of imagination that finds its form in the institution of verse, or even a bond of love that finds its form in the institution of marriage. He had a sense of misgiving about what’s lost in learning as it’s institutionalized in college. He occupies this funny role where he has these misgivings but he very much thinks that the institution is better than the utopian alternative. He’s a lapsed Romantic, where both the Romanticism and the lapse are important. He is able to imagine an ideal alternative to the way things are, while being critical of the kind of idealism that would demand that the world actually rise up to meet it.

INTERVIEWER

This makes me think that a better way to describe the tension we’ve been discussing is not between education and the lack thereof but between two different kinds of knowing. Maybe the poems ask you to get your more educated knowing out of the way.

PLUNKETT

You’re certainly right that the work does that—the work at its best, I should say, and that qualification really ought to stand for a lot of it, since it’s not a very large oeuvre of published work and about half of it is really not so good. Though I don’t think that’s a bad ratio for a poet. Poetry is just really, really hard to do well. But when Frost’s work is good, it gives us some capacity to see things stripped away from the judgments we might otherwise bring to them.

INTERVIEWER

Is there a moral dimension to Frost’s work?

PLUNKETT

The relationship between the aesthetic and the moral is quite different for Frost than it is for a lot of secular moderns. He thinks of greatness—though he would never try to formulate it so neatly—partly as being able to see things of value with profound clarity. And seeing things that way was itself a kind of glorification of God for him. His absolute reverence for greatness in art meant that he was hesitant to subordinate his art to ethical demands that most people would probably consider more important. He infuriated his old friend and critical champion Louis Untermeyer, a Jewish American who was doing a great deal to raise awareness of the Holocaust, by refusing to write poetry for the war effort. Frost compared such a demand with that made on ancient Greeks in wartime to appease the gods by destroying beautiful works of art. This perspective can look foreign to a lot of people, especially reading him now. He is also not entirely consistent in holding it.

INTERVIEWER

Frost talks about “coming close to poetry” as a way to describe the experience of connecting with a particular author’s work, but also with the feeling that poetry makes sense as a thing in the world. What would it take for a reader to come close to Frost’s poetry now?

PLUNKETT

Reading Frost requires a kind of modesty and curiosity. Coming to this modesty has been a big part of my own experience with him. At first, I was reading a lot of the poems and thinking, This is dumb. What a dumb way of looking at the world. Then I would think more, and read them again, and the twentieth time, I would realize I had been holding on to a false sense of certainty. Frost called poetry “guessing at myself.” If you have a picture of yourself or of the other or of the world that’s entirely certain, then you can’t really guess at it.

INTERVIEWER

Do you think a worldview that is so invested in guessing, or in withholding judgment, comes off as too spiritual for contemporary readers? It can feel so urgent today to come down on a side.

PLUNKETT

There are parts of Frost’s uncertainty that I think can feel profoundly intuitive, even revelatory, these days. The sense of the self as always imperfectly known, always at most guessed at, and the picture that follows of inner life with the constant play of interpretations at the heart of it—what could feel more modern than that? But Frost also had a profound sense of the sacred, and a quite complex sense of the relationship between the sacred and his own often quite profane self. This relationship is hard to get a handle on—in some ways the book is both my effort to wrap my head around it and a history of Frost, and everyone around him, trying to do the same. In a way that was beguiling for everyone, Frost was both a thoroughgoing skeptic about received religious ideas and profoundly religious in the tradition of Anglo-American Puritanism. He was absolutely animated by the conviction that his inner life, his will, was for something far greater than itself. But how much his self had reached the ideals that drove him—this he could only guess at. This kind of inner drama is probably harder to see now for readers less familiar with Protestant habits of feeling.

Frost’s gravestone. Photograph courtesy of Jessica Laser.

INTERVIEWER

Are you saying that Frost believed in the soul?

PLUNKETT

Very much, yes.

INTERVIEWER

Do you think that Frost is uncool, or has become uncool, because the soul has become uncool? Would a comeback for Frost require a comeback for the soul?

PLUNKETT

The short answer is yes. Uncool is such a great way to put it. All sorts of ways people talk and think about themselves today, even among the most educated, seem animated by a premonition that there’s something more spiritual underlying the world. But it’s still not cool. If you’ve been to college, you’ve probably heard that there’s no rational way to defend that idea. For Frost it comes down to a tension about how much of the world is answerable to reason and how much to some kind of intuition. In a way, his work is all about doubt, but he is a doubter from the vantage of somebody who thinks that there may well be some immortal part of him.

INTERVIEWER

How would you describe Frost’s legacy to someone who has never heard of him?

PLUNKETT

I would say that Frost’s public life in poetry is one of the great ironies of American literary history. An unbelievably strange and idealistic young person, who did not naturally fit into any world in young adulthood, managed by absolute, astonishing drive to study and apprentice his way through obscurity into becoming the very voice of the establishment and the heart of American culture. That’s the history part. As for the poetry part, I’d say that, for me, the biggest gift of the art is his ability to see potentially transcendent beauty and a sense of meaning in things that you’d otherwise think of as too obvious to really regard. It’s a kind of grace of attention. And it’s just really good poetry, you know? It’s great stuff.

INTERVIEWER

Half of it.

PLUNKETT

Half of it. Exactly.

Jessica Laser’s most recent collection of poetry is The Goner School. Her poem “Consecutive Preterite” appeared in issue no. 247.

March 14, 2025

Dreams from the Third Reich

J. J. Grandville, A Dream of Crime and Punishment, 1847, via Wikimedia Commons. Public domain.

Charlotte Beradt began having strange dreams after Hitler took power in Germany in 1933. She was a Jewish journalist based in Berlin and, while banned from working, she began asking people about their dreams. After fleeing the country in 1939 and eventually settling in New York, she published some of these dreams in a book in 1966. Below, in a new translation from Damion Searls, are some of the dreams that she recorded.

Three days after Hitler seized power, Mr. S., about sixty years old, the owner of a midsize factory, had a dream in which no one touched him physically and yet he was broken. This short dream depicted the nature and effects of totalitarian domination as numerous studies by political scientists, sociologists, and doctors would later define them, and did so more subtly and precisely than Mr. S. would ever have been able to do while awake. This was his dream:

Goebbels came to my factory. He had all the employees line up in two rows, left and right, and I had to stand between the rows and give a Nazi salute. It took me half an hour to get my arm raised, millimeter by millimeter. Goebbels watched my efforts like a play, without any sign of appreciation or displeasure, but when I finally had my arm up, he spoke five words: “I don’t want your salute.” Then he turned around and walked to the door. So there I was in my own factory, among my own people, pilloried with my arm raised. The only way I was physically able to keep standing there was by fixing my eyes on his clubfoot as he limped out. I stood like that until I woke up.

Mr. S. was a self-confident, honest, and upright man, almost a little dictatorial. His factory had been the most important thing to him throughout his long life. As a Social Democrat, he had employed many of his old Party comrades over the past twenty years. It is fair to say that what happened to him in his dream was a kind of psychological torture, as I spontaneously called it when he told me his dream in 1933, a few weeks after he’d had it. Now, though, in hindsight, we can also find in the dream—expressed in images of uncanny, sleepwalker-ish clarity—themes of alienation, uprooting, isolation, loss of identity, a radical break in the continuity of one’s life: concepts that have been widely popularized, and, at the same time, widely mythologized. This man had to dishonor and debase himself in the factory that was practically his whole sense of self, and do so in front of employees representing his lifelong political views—the very people over whom he is a paternalistic authority figure, with this sense of authority being the most powerful component of who he feels he is as a person. Such humiliation ripped the roots up out of the soil he had made his own, robbed him of his identity, and completely disoriented him; he felt alienated not only from the realities of his life but from his own character, which no longer felt authentic to him.

Here we have a man who dreamed of political and psychological phenomena drawn directly from real life—a few days after a current political event, the so-called seizure of power. He dreamed about these phenomena so accurately that the dream captured the two forms of alienation so often equated or confused with each other: alienation from the environment and alienation from oneself. And he came to an accurate conclusion: that his attempt in front of everyone to toe the Nazi line, his public humiliation, ended up being nothing but a rite of passage into a new world of totalitarian power—a political maneuver, a cold and cynical human experiment in applying state power to break the individual’s will. The fact that the factory owner crumbled without resistance, but also without his downfall having any purpose or meaning, makes his dream a perfect parable for the creation of the submissive totalitarian subject. By the time he stands there at the end of the dream, unable to lower his arm again now that he’s finally raised it, staring at Goebbels’s clubfoot in petty revenge against the man who holds all the true power and only in that way managing to stay on his own two feet at all, his selfhood has been methodically demolished with the most up-to-date methods, like an old-fashioned house that has to make way for the new order. And yet what has happened to him, while sad, is hardly a tragedy—it even has something of a farce about it. The dream depicts not so much an individual’s fate as a typical event in the process of transformation. He has not even become unheroic, much less an antihero—he has become a nonperson.

***

The factory owner’s dream—what should we call it? “The Dream of the Raised Arm”? “The Dream of Remaking the Individual”?—seemed to have come directly from the same workshop where the totalitarian regime was putting together the mechanisms by which it would function overall. It confirmed an idea I had already had in passing: that dreams like this should be preserved for posterity. They might serve as evidence, if the Nazi regime as a historical phenomenon should ever be brought to trial, for they seemed full of information about people’s emotions, feelings, and motives while they were being turned into cogs of the totalitarian machine. Someone who sits down to keep a diary does so intentionally, and shapes, clarifies, and obscures the material in the process. Dreams of this kind, in contrast—not diaries but nightaries, you might say—emerge from involuntary psychic activity, even as they trace the internal effects of external political events as minutely as a seismograph. Thus dream images might help interpret the structure of a reality about to turn into a nightmare.

And so I began to collect the dreams that the Nazi dictatorship had, as it were, dictated. It was not entirely an easy matter, since more than a few people were nervous about telling me their dreams; I even ran across the dream “It’s forbidden to dream but I’m dreaming anyway” half a dozen times in almost identical form.

I asked the people I came into contact with about their dreams; I didn’t have much access to enthusiastic supporters of the regime, or people benefiting from it, and their internal reactions in this context would in any case not have been particularly useful. I asked the dressmaker, the neighbor, an aunt, a milkman, a friend, almost always without revealing my purpose, since I wanted their answers to be as unembellished as possible. More than once, their lips were unsealed after I told them my factory owner’s dream as an example. Several had been through something similar themselves: dreams about current political events that they had immediately understood and that had made a deep impression on them. Other people were more naive and not entirely clear on the meaning of their dreams. Naturally, each dreamer’s level of understanding and ability to retell their dreams depended on their intelligence and education. Still, whether young lady or old man, manual laborer or professor, however good or bad their memory or expressive ability, all had dreams containing aspects of the relationship between the totalitarian regime and the individual that had not yet been academically formulated, like the elements of “crushing someone’s personhood” in the factory owner’s dream.

It goes without saying that all these dream images were sometimes touched up by the dreamer, consciously or unconsciously. We all know that how a dream is described depends heavily on when it is written down, whether right away or later—dreams written down the same night, as many of my examples were, are of greatest documentary value. When written down later, or retold from memory, conscious ideas play a greater role in the description. But even aside from the fact that it is also interesting to hear how much the waking mind “knew” and supplemented the dream with images from the real environment, these particular dreams about political current events were especially intense, relatively uncomplicated, and less disjointed and erratic than most dreams, since after all they were unambiguously determined. Typically they consisted of a coherent, even dramatic story, and so were easy to remember. And in fact they were remembered—spontaneously, without artificial help—unlike most dreams, especially painful dreams, which are quickly forgotten. (Remembered so well that quite a lot of them were told to me with the same introductory words: “I’ll never forget it.” And after my first publication on this topic, several people told me dreams that lay ten or twenty years in the past by then, dreams that clearly were unforgettable; these retrospective accounts are labeled as such in this book.)

I gathered material in Germany until 1939, when I left the country. Interestingly, the dreams of 1933 and those from later years are remarkably similar. My most revealing examples, however, are from the early, original years of the regime, when it still trod lightly.

***

The most obvious and striking facts of the totalitarian regime—the rules and regulations, laws and ordinances, prescribed and preplanned activities—are the first things to penetrate the dreams of its subjects. The bureaucratic apparatus of offices and officeholders is in fact a dream-protagonist par excellence, macabre and grotesque.

One forty-five-year-old doctor had this dream in 1934, a year into the Third Reich:

At around nine o’clock, after my workday was done and I was about to relax on the sofa with a book on Matthias Grünewald, the walls of my room, of my whole apartment, suddenly disappeared. I looked around in horror and saw that none of the apartments as far as the eye could see had any walls left. I heard a loudspeaker blare: “Per Wall Abolition Decree dated the seventeenth of this month.”

This doctor, deeply troubled by his dream, decided on his own to write it down the next morning (and consequently had further dreams that he was being accused of writing down dreams). He thought further about it and figured out what minor incident of the day before had prompted his dream, which was very revealing—as so often, the personal connection made the historical relevance of the scene depicted in the dream even clearer. In his words:

The block warden had come to me to ask why I hadn’t hung a flag. I reassured him and offered him a glass of liquor, but to myself I thought: “Not on my four walls … not on my four walls.” I have never read a book about Grünewald and don’t own any, but obviously, like many others, I think of his Isenheim Altarpiece as a symbol for Germany at its purest. All the ingredients of the dream and everything I said were political but I am by no means a political person.

“Life Without Walls”—this dream formulation that universalizes in exemplary fashion the plight of an individual who doesn’t want to be part of a collective—could easily be the title of a novel or academic study about life under totalitarianism. And along with capturing perfectly the human condition in a totalitarian world, the doctor’s dream went on to express the only way out of a “life without walls”: the only way to achieve what would later be called inner emigration.

Now that the apartments are totally public, I’m living on the bottom of the sea in order to remain invisible.

An unemployed, liberal, cultured, rather pampered woman of about thirty had a dream in 1933 which, like the doctor’s, revealed the existential nature of the totalitarian world:

The street signs on every corner had been outlawed and posters had been put up in their place, proclaiming in white letters on a black background the twenty words that it was now forbidden to speak. The first word on the list was Lord—in English; I must have dreamed it in English, not German, as a precaution. I forgot the other words, or probably never dreamed them at all, except for the last one, which was: I.

When telling me this dream, she spontaneously added: “In the old days people would have called that a vision.”

It’s true: A vision is an act of seeing, and this radical dictate, whose first commandment was “Thou shalt not speak the name of the Lord” and whose last forbade saying “I,” is an uncannily sharp way of seeing the domain that the twentieth century’s totalitarian regimes have occupied—the empty space between the absence of God and the absence of identity. The basic nature of the dialectic between individual and dictatorship is here revealed while cloaked under a parable. This woman herself admitted with a laugh that her “I” was in general quite prominent. But then we have the details that flesh out the dream: the poster that the dreamer put up like Gessler’s hat; the outlawed, missing street signs symbolizing people’s directionlessness as they are turned into mere cogs. And the simple move of dreaming that the poster listed the English word Lord, which she never uses in her normal life, in place of the German Gott, serves to show that everything high and noble and excellent is forbidden altogether.

This dreamer produced a whole series of such dreams between April and September of 1933—not variations on the same dream, like the factory owner’s, but different ways of processing the same basic theme. While a perfectly normal person in daily life, she proved herself in her dreams to be the equal of Heraclitus’s sibyl, whose “voice reached us across a thousand years”—in a few months of dreams she spanned the Thousand Year Reich of the Nazis, sensing trends, recognizing connections, clarifying obscurities, and vacillating back and forth between easily unmasked realities of everyday life and mysteries lying beneath the visible surface. In short, her dreams distilled the essence of a development which could only lead to public catastrophe and to the loss of her personal world, and expressed it all articulately by moving between tragedy and farce, realism and surrealism. Her dream characters and their actions, their details and nuances, proved to be objectively accurate.

Her second dream, coming not long after the dream of God and Self, dealt with Man and the Devil. Here it is:

I was sitting in a box at the opera, beautifully dressed, my hair done, wearing a new dress. The opera house was huge, with many, many tiers, and I was enjoying many admiring glances. They were performing my favorite opera, The Magic Flute. After the line “That is the Devil, certainly,” a squad of policemen marched in and headed straight toward me, their footsteps ringing out loud and clear. They had discovered by using some kind of machine that I had thought about Hitler when I heard the word Devil. I looked around at all the dressed-up people in the audience, pleading for help with my eyes, but they all just stared straight ahead, mute and expressionless, with not a single face showing even any pity. Actually, the older gentleman in the box next to mine looked kind and elegant, but when I tried to catch his eye he spat at me.

This dreamer understood perfectly the political uses of public humiliation. One guiding theme in this dream, among many other motifs, is the “environment.” The concrete stage-setting of the giant curved tiers of seats in an opera house, filled with fellow men and women who merely stare into space “mute and expressionless” when something happens to someone else, very skillfully depicts this abstract concept, with the extra touch of the man who seems from his appearance to be the last person you’d think would be capable of spitting on this young, vain, well-dressed woman. What she called the faces’ “mute and expressionless” look, the factory owner had called their “emptiness.” (Theodor Haecker, in a dream from 1940, twice mentioned the “impassive faces” of his friends as they just stood and watched him.) Very different people all hit upon the same code for describing a hidden phenomenon of the environment: the atmosphere of total indifference created by environmental pressure and utterly strangling the public sphere.

When asked if she had any idea what the thought-reading machine in her dream was like, the woman answered: “Yes, it was electrical, a maze of wires …” She came up with this symbol of psychological and bodily control, of ever-present possible surveillance, of the infiltration of machines into the course of events, at a time when she could not have known about remote-controlled electronic devices, torture by electric shock, or Orwellian Big Brothers—she had her dream fifteen years before 1984 was even published.

In her third dream, which came after she had been shaken by the reports of book burnings—especially the news she’d heard on the radio, which repeated the words truckloads and bonfires many times—she dreamed:

I knew that all the books were being picked up and burned. But I didn’t want to part with my Don Carlos, the old school copy I’d read so much it had fallen apart. So I hid it under our maid’s bed. But when the storm troopers came to collect the books, they marched right up to the maid’s room, footsteps ringing out loud and clear. [The ringing footsteps and heading straight toward someone were props from her previous dream, and we will encounter them again in many other dreams.] They took the book out from under her bed and threw it onto the back of the truck that was going to the bonfire.

Then I realized that the book I’d hidden wasn’t my old copy of Don Carlos after all, it was an atlas of some kind. Even so, I stood there feeling terribly guilty and let them throw it onto the truck.

She then spontaneously added: “I’d read in a foreign newspaper that during a performance of Don Carlos the crowd had burst into applause at the line ‘O give us freedom of thought.’ Or was that only a dream too?”

The dreamer here extends the characterization, begun in her opera-house dream, of the new kind of individual created by totalitarianism. But here she includes herself in her critique of the environment, recognizing the typical aspects of her own behavior: The book she tries to hide under a bed like a criminal isn’t even a truly forbidden book, only Schiller, and then it turns out she doesn’t even hide that—out of fear and caution she hides an atlas, which is to say, a book with no words at all. And even so, despite being innocent, she feels weighed down with guilt.

While this dream gently suggested that the formula “Keeping Quiet = A Clear Conscience” cannot apply within the new system of moral calculation, her next dream went quite a bit further in that direction. It was a complex dream, with less of a complete plot and harder to understand, but she did understand it.

I dreamed that the milkman, the gas man, the newspaper vendor, the baker, and the plumber were all standing in a circle around me, holding out bills I owed. I was perfectly calm until I saw the chimney sweep in the circle and was startled. (In our family’s secret code, a chimney sweep— Schornsteinfeger—was our name for the SS, because of the two S’s in the word and the black uniforms.) I was in the middle of the circle, like in the children’s game Black Cook, and they were holding out their bills with arms raised in the well-known salute, shouting in chorus: “There’s no question what you’re responsible for.”

The woman knew exactly what lay behind the dream psychologically: On the previous day, her tailor’s son had showed up in full Nazi uniform to collect on a bill for tailoring work she had just had done. Before the national crisis, of course, bills were sent by mail after an appropriate interval. When she asked him what this was all about, he answered, with some embarrassment, that it didn’t mean anything, he just happened to be passing by, and happened by chance to be wearing his uniform. She said, “That’s ridiculous,” but she did pay. A little piece of daily life—but in these times, ordinary everyday incidents were not just ordinary. The woman used this little story to explain in detail how things were operating under the new “block warden system”: the intrusions happening every day and protected by the Party uniform; the many private accounts being settled at the same time; individuals increasingly being encircled by the various little people—Grandpa Tailor, Uncle Shoemaker. All of these figures flitted like phantoms through her Black Cook dream.

The chorus in the dream, though, making her the typical accused person under a totalitarian system with her guilt presumed in advance—“There’s no question about what you’re responsible for”—is also, in German, a clear reference to Goethe’s “All guilt is avenged upon this earth”; it represents her own feelings of guilt at having given in to the pressure despite it being slight pressure, which she called ridiculous and the tailor’s son in uniform called just by chance.

Like the Don Carlos dream before it, this Black Cook dream describes in a very subtle way the first little compromise, the first minor sin of omission, that snowballs until a person’s free will weakens and eventually wastes away altogether. The dream describes normal everyday behavior and the barely perceptible wrongs that people commit, shedding light on a psychological process that even today, despite the best efforts, is extremely hard to explain: the one that makes even those who are technically innocent of crimes guilty.

I would add only that the line about undoubted guilt (“Die Schuld kann nicht bezweifelt werden“) appears in almost identical words in Kafka’s story “In the Penal Colony,” spoken by the officer: “Guilt is never to be doubted” (“Die Schuld ist immer zweifellos“).

This woman’s dreams, full of Orwellian objects and Kafkaesque realizations, tended to repeatedly treat the new circumstances of her environment as static situations: the neighbors with “expressionless faces” sitting around her “in a large circle,” she herself feeling “trapped” or “lost.” Once—in fact on New Year’s Eve, 1933 to 1934, after the customary New Year’s Eve ritual of telling fortunes from the shapes made by dropping molten lead into cold water— she dreamed not even situations but pure impressions, words without any images at all. She wrote the words down that night:

I’m going to hide by covering myself in lead. My tongue is already leaden, locked up in lead. My fear will go away when I’m all lead. I’ll lie there without moving, shot full of lead. When they come for me, I’ll say: Leaden people can’t rise up. Oh no, they’ll try to throw me in the water because I’ve been turned into lead …

Here the dream broke off. We could describe this as a normal anxiety dream—there is no pun in German between the metal lead and the verb to lead or a leader—although it is an unusually poetic one, whose horrors we can feel even without knowing any additional context. (It was used in a short story in 1950.) But the dreamer herself pointed out the scraps of rhyme from the Nazi “Horst-Wessel-Lied” woven into the dream (geschlossen / erschossen [“locked up / shot full”]), and added that she had felt this way, leaden and anxious, for months. If we want to interpret further, we might consider that her phrase “Leaden people can’t rise up” uses the verb aufstehen, the root of Aufstand, “uprising” or “revolution,” so the line has a deeper meaning that she didn’t see despite being so perceptive otherwise.

In any case, her hiding in lead matches the doctor’s hiding at the bottom of the sea as an expression of the wish to withdraw completely from the outside world.

From this handful of fables about a “life without walls,” told in their sleep , it is easy to reconstruct the real circumstances that motivated them. Each of them also represents an abstraction (for instance, the woman’s “environment dreams” exemplify “the destruction of plurality” as well as the feeling of “loneliness in public spaces” that Hannah Arendt would later characterize as the basic quality of totalitarian subjects). These dreams depict not just environmental shocks but the psychological and moral effects of these shocks within the dreamer’s mind.

Adapted from The Third Reich of Dreams: The Nightmares of a Nation, translated by Damion Searls, which will be published by Princeton University Press next month.

Charlotte Beradt (1907–1986) was a Jewish journalist and communist activist based in Berlin during the Third Reich. She fled to New York in 1939 as a refugee, creating a gathering place for other German émigrés, including Hannah Arendt.

Damion Searls is an award-winning translator and writer whose translation of Jon Fosse’s A New Name was short-listed for the International Booker Prize.

March 13, 2025

Self-Assessment

Alan Fears, A PATTERN OF BEHAVIOUR, 2017, ACRYLIC ON CANVAS, 40″ x 40″. From I’m OK, You’re OK, a portfolio in issue no. 229.

Around this time last year, the USB hookup in my car stopped working. I started to listen to the radio more and began to buy CDs again, something I hadn’t done much since I was a teenager. Greg Mendez played a concert in Nashville, and before he went on, I bought two from his merch table: his self-titled album from 2023, and Live at Purgatory, from 2022. I put them in my car. I try not to skip songs on either one. But I am happy when I hear him introduce the sixth track on Live at Purgatory, “Bike.”

It’s a short song. Mendez sings the lyrics only once. This is what I hear, which is different from what I see on Genius but is the same as in a handwritten lyric card I can partially see in a picture on Bandcamp:

I wanna ride your brother’s bike

I wanna stab his friends sometimes

I wanna tell a million lies

I wanna steal your partner’s heart

I wanna turn your pain to art

I wanna cry in your mother’s arms

I wanna wear your daddy’s jeans

I wanna drink the way he did

I wanna smoke menthol cigarettes

and I wanna fight

I wanna fuck on ecstasy

I wanna love, but what’s that mean?

I wanna go back on EBT

Those words take a little more than fifty-five seconds. It’s instrumental for a minute more. I only recently realized how short it is. It was a strange realization, because I love this song and talk about it to my friends, and would have thought I would have already noticed that it was so brief, or that it doesn’t have a chorus, or a bridge, or even more than one verse. But by the end of the lyrics, I am often so struck by his voice and by the way his voice says these things—which in his mouth are so beautiful, even if they are not necessarily beautiful things to say—that my mind has gone into outer space, and I guess the rest of the song, or its absence, has been lost on me.

Most of the lines follow the same pattern, aurally speaking, with an exaggerated, even artificial lift to Mendez’s last word. “I wanna ride your brother’s bike.” “I wanna tell a million lies.” “I wanna cry in your mother’s arms.” Some depart from the pattern or seem to move instead towards an elongated downturn in his voice, almost distended: “I wanna stab his friends sometiiiimes.” “I wanna turn your pain to aaaart.” The tonal structure almost follows an ABAB scheme, though not quite.

The exception is the second-to-last line. When Mendez says, “I wanna love, but what’s that mean?” his voice changes in quality: it is softer, less definitive. It is obviously asking a question, but I have also heard a sweetness, almost a wistfulness, a different wistfulness from the rest of the song. Maybe I have heard hope, particularly as it pairs with the guitar’s brief chord change. When set against the other lyrics, which seem to speak of pain, past pain, destruction, self-destruction, lost childhood, even self-hatred, the line has felt like a turn, or an allowance. And though the next, last line feels like a turning back—maybe not quite to the old pattern, but to an almost brash quality in his voice, and back to declaration—Mendez’s question remains alone: a quiet rest, or grace.

This December, “Bike” came on while I was stopped at an intersection. The second-to-last line sounded different. It suddenly occurred to me that Mendez’s voice, rather than earnest, might be bitter, maybe even cynical. Not “What is love? What does love mean? When will I know I have it?” but “What does it mean for me to say, ‘I want to love?’ What does it mean when I say anything? Do I even believe myself? Would anyone else?” His question seemed to point not outward, at existential wonder, but back at himself: to this person who might tell a million lies, who might exploit other people or take their things, whom he doesn’t know if he could trust to handle loving. I had never heard these lines that way before, even though his voice sounded the same as always.

I don’t know that I would have made much of my new interpretation if it had not been, at that time, only a week or two since I had taken my last available Lexapro, an antidepressant I’d been using at a low dose for five years, excluding the few months I swapped it for Wellbutrin. I had been curious if Wellbutrin wouldn’t make me so sleepy. I don’t remember if it made me less sleepy, but it did make me volatile; I switched back to Lexapro, and again I felt calm. Much of the stability, happiness, and connection I had built I attributed to the addition of Lexapro to my life, or at least to the person it allowed me to be. I didn’t think I would stop taking it.

But I was splitting my pills between my partner’s place and mine, imperfectly dividing three-month refills from a provider at the counseling center of the university where I had recently completed a graduate degree. I ran out more quickly than I thought I would, having miscounted the amount I had stored at my partner’s place. By the time I was able to get my new primary care provider to write me a prescription, enough time had passed that I understood the drug was no longer present in my body. I felt no different, and though I knew it was possible that this coasting wouldn’t last—that I would feel the loss of the medication in a few weeks, or maybe months—I was curious what would happen. It seemed possible that enough had changed in my life that I could live without Lexapro’s support, even if only for a little while. This felt like potentially new information, and information I would like to have. I made an appointment with a new psychiatrist. I thought the weeks until we were scheduled to meet would be a good length of time to conduct my experiment.

Because I was suddenly less medicated, I was alert, maybe over-alert, to any shift toward melancholy. In my car, listening to “Bike,” I wondered if the way I heard Mendez’s voice indicated a direction I did not want my perception to go. While it wasn’t necessarily unpleasant to hear something new, the difference pointed downward. I had heard his tender wonder. Suddenly I heard his self-disgust.

I have noticed that, when I am closer to experiences of depression—when I am in the middle of what I would call a depressive episode, or when I have just recently emerged—the centrifugal force of my own experience tends to draw in objects and other people, until I believe them all to be referencing a personal darkness not dissimilar from my own. This has happened enough that I know it to be temporary, if not false. I trust that when I inevitably feel better again, I will see things differently.

An example: Etel Adnan’s Shifting the Silence, which I bought and read in a happy part of my life. Her poems made me feel like I was looking at one of her paintings: held in their atmosphere, even if few of her words made much sense to me. From my first reading, I most remember a line about unrequited crushes—that they were like fallen angels, I think.

But when I read it again a year or two later, during my Wellbutrin months, I found myself focusing on a passage that suddenly seemed to say “depression.” I copied it down:

It’s gray outside, stormy. I am looking at the ocean, it’s some ten yards away, I wonder why its tide stops at a certain point, why it doesn’t enter my apartment, but I have to live my limitations, so I think that the ocean too has its own destiny.

There’s a pale yellowish band above the horizon. Why does a horizon exist? To lift my spirit?

Right now this passage feels not quite neutral, but maybe ambivalent. Maybe it’s about depression; it feels a bit morbid, or at least as if it’s about the ends of things. But maybe there is an upward lilt, as though the speaker might intend to make someone laugh. It is kind of funny to compare your limits to those of the ocean. Limitations can mean many things—can be cozy, even, or imbued with a humble sense of what’s possible on a human scale. I can imagine the last two questions as wry, posed to a lover beside the speaker on a balcony. The lover is looking at the horizon, or at the speaker, who is pointing and saying, See that? That’s there to cheer me up. The partner might laugh. There might be something calm about the melancholy, if not peaceful—at least something through which it is possible to live.

But that was not what I saw when my depression felt closer. Depression seemed to be the subject. Maybe it is; I don’t really know. Even now, of course, I am connecting the text to my experience, even if my experience does not feel quite as narrow as it has in other moments of my life. I have placed a partner in the text, where maybe there is none. I guess I am thinking about my partner; I guess that has made him what I see.

In September, my partner began to refer to some of my connection-making tendencies as “the coffee phenomenon.” This “phenomenon” describes a pattern he observes in which I ascribe all changes in my experience of the world to the effects of physical substances I am taking or not taking, most often coffee, though sometimes other things. If I am happy, it is because I drank coffee; if I am sad, it is because I drank too much coffee or not enough; if I have a lot of energy, it is because I drank coffee or because I haven’t been drinking coffee; if I am tired, it’s because I drank very strong coffee or because I need more coffee. When I am not as focused on coffee, I might focus on something else: whether I have gone running, maybe, or whether I’ve had any alcohol in the last few days.

The joke of the “coffee phenomenon” is not quite that it is wrong: I am sure coffee does affect me; I am sure exercise affects me, and alcohol too. But even if I account only for those three variables, my focus on coffee would eliminate the effects of the other two, which might fluctuate even though they are excluded from the calculus. If I am happy on a Saturday morning, for example, I could attribute that to having had coffee, but that would mean it is not actually so relevant that I have not gone running, which a week earlier I might have said most related to my happiness. And of course there are many more variables than these three. Psychotropic medication would certainly be another.

But when I brought up this concept to my partner—that I was curious about my new read of the Greg Mendez song, and whether it might be connected to my recent change in medication, or whether that was a misattribution—he was not so interested. At the time, I had gone only a couple of weeks without Lexapro, and I suppose it seemed possible that I would suddenly deteriorate, maybe more quickly than I could coherently intellectualize. He used the words playing with fire rather than experimenting. He said, “This isn’t an exercise.” He said, “You talk about depression like it’s giving birth—like you don’t remember how awful it was.” I saw his point. I asked him to tell me if I seemed different; that I would be careful, too.

It is easier, of course, to wonder how the absence or addition of Lexapro might affect how I respond to a present stressor—for example, the Department of State’s indefinite withholding of my partner’s passport, along with those of others who tried to update their gender markers while it was still possible—than to worry about the intentions behind that withholding, or the implications of that loss for our capacity to leave this country together, should the government continue to graduate its violence towards trans people. I still didn’t fully anticipate what it would feel like to see my partner explicitly targeted by the executive branch of the federal government, even though we live in Tennessee, even if it isn’t new to see trans people targeted. In bed I kept finding myself trying to press as much of my body onto his as possible, as though I could transmit protection through the warmth of my skin. I didn’t know if it was an accurate read of the circumstance or depression leading my mind too far when I kissed him and felt I should pay attention, thinking I could one day lose him, whether to some kind of detainment or to the psychological consequences of his experience. It was too much. I went back on Lexapro.

Live at Purgatory was still in my car. On the way to work, I again heard Mendez differently, or heard something new. The way he said “art”—“I wanna turn your pain to art”—sounded less like a drop and more like the gentle waver of his question–”what’s that mean?” I wondered if this was an aural clue, the answer hidden in the test: one meaning of love, at least for Mendez. It seemed possible, or at least relevant to me. I wanted to make art, too; I wanted to make something out of this thing we were experiencing. But I also felt that love was starting to mean other things, had already come to mean new things, and would mean newer things still. I wanted to know what it would mean in a week. I want to know what it will mean the week after this. And I want my partner to get his passport back.

Devon Brody is a writer living in Nashville.

March 11, 2025

The Prom of the Colorado River

Photograph by Meg Bernhard.

Alfalfa smells warm and earthy and sort of sweet, like socks after a long hike, but not in a bad way. It is soft, with oblong green leaves the size of a pinkie nail. I know this because on a chilly February afternoon I drove a hundred and forty miles to the Imperial Valley, one of the state’s largest farming regions, pulled over to an unattended field, and ripped up a clump. It was a brown day; the wind turbines in Palm Springs were spinning and a dust storm was brewing. The air was more humid than normal. Alfalfa grows everywhere around the West, but it’s peculiar to see vast green fields in this place—a low, dry desert where vegetation is scarce and water even scarcer. But the Imperial Valley, home to an accidental salt lake and a mountain made of multicolored painted adobe clay, is one of California’s weirder places. The Salton Sea’s gunky shoreline takes off-road vehicles prisoner. A roving mud puddle eats at the highway. Roughly a hundred and fifty thousand acres of alfalfa grow in a place that sees fewer than three inches of rain a year.

People love to hate alfalfa. It’s become the Southwest’s boogeyman, chief offender in the megadrought. Farmers use alfalfa for cattle feed because it’s high in protein, but the crop, a perennial, requires a lot of water—by one estimate five acre-feet per acre in the Imperial Valley. By comparison, Imperial Valley lettuce uses about three acre-feet per acre, while, on average, grapes across the state use about 2.85. (An acre-foot is about enough to cover a football field in water a foot deep; alfalfa, then, requires five of those per acre.)

I think about alfalfa a lot, but only in the abstract, as a crop that uses too much water and enables the existence of more cows, which burp methane and make the climate crisis worse. I wanted to see it up close, and I also wanted to speak with one of the West’s most fervent students, and defenders, of alfalfa. His name is John Brooks Hamby, and he’s the vice chairman of the board of directors for the Colorado River’s largest single user, the Imperial Irrigation District, also called IID. Unlike alfalfa farther north, which may see a couple of harvests a year, Imperial Valley alfalfa enjoys a long season, he told me when I arrived at a sterile IID office in El Centro decorated with photos of canals and footbridges. “We can get ten-plus cuttings here,” he said. “Really thick, dense stands.” Alfalfa is not the valley’s only crop; when I was visiting, lettuce was in season, as was celery. I’d apparently just missed the carrot festival in Holtville, where sixteen-year-old Ailenna Salorio was named the 2025 carrot queen. There are dates and lemons and broccoli and spinach and onions too. But alfalfa is king.

John Brooks calls himself JB. JB grew up in the Imperial Valley town of Brawley. There, as he tells it, his great-grandfather had come from Texas to dig irrigation ditches. His grandfather worked in land leveling, and his father went away for college but returned to grow and sell produce. At his parents’ wedding, guests ate his father’s asparagus, which he had to quit growing, JB told me, after NAFTA cut into California farmers’ asparagus profits. JB grew up tagging along as his dad checked fields and irrigated crops late at night. Water shaped the political and economic landscape of the Imperial Valley, whose water district has some of the oldest, most senior rights to the Colorado River.

JB is twenty-nine. He is bookish and talkative, fond of bolo ties and Navajo concho belt buckles, at ease with cattle ranchers and water scholars. He is also California’s lead negotiator on the Colorado River, which serves forty million people across seven Western states, thirty tribes, and two Mexican states. Each of the American states that the river feeds—including Wyoming, Colorado, Utah, and New Mexico, considered the “upper basin,” as well as Nevada, Arizona, and California, “the lower basin”—appoints a principal negotiator to hash out what water usage across the river ought to look like. The lower and upper basin negotiators always fight over who has to cut back on water. Alfalfa, as the symbol of California’s excess in a time of drought, is an easy target. This irritates JB. “You go into the grocery store, go into the whole dairy section. You have Fage or Yoplait, Horizon grass-fed milk, or you’re having any of the nonvegan ice creams. Beef. All of that comes from alfalfa,” he said. “It’s a foundational part of the food supply for both humans and animals.” Alfalfa earned $269.7 million for Imperial County in 2022. That year it sold for $325 a ton.

Photograph by Meg Bernhard.

***

I first met JB during the Colorado River Water Users Association conference—affectionately called CRWUA (pronounced “crew-uh”)—at the Paris Casino in Las Vegas last December. It was, at first glance, like any other Vegas conference: morning registration a few feet away from people who’d been up all night playing slot machines, panels held in windowless ballrooms, attendees milling around in lanyards, with a few casino-specific details like fake French boulevards, not to mention “toilettes” instead of restrooms. The Colorado River folks wore their western wear: cowboy boots, turquoise. Some wore cowboy hats, though the national finals rodeo was also happening in Vegas that week and it was hard to differentiate the cattle people from water people.

CRWUA, as JB put it to me later, “is the prom of the Colorado River.” “Everybody shows up. You’ve got the exhibit hall where you can do whatever. There’s the drinks” he said. The panels. “It’s the only time the entire basin comes together in one place.” By the entire basin, he meant negotiators, lawyers, scholars, water managers, conservationists, tribal chairpeople, consultants, engineers, hydrologists, cloud seeders, solar panel marketers, Bureau of Reclamation bureaucrats, and people with job titles like Colorado River Basin Salinity Control Forum director and Irrigation and Electrical Districts director.

I didn’t really meet JB; he was venting about the upper basin to a reporter friend of mine who was somehow still on good terms with him even though he’d investigated the Imperial Irrigation District’s water usage. My friend and his colleagues had found that, in 2022, one farming family used more Colorado River water than all of southern Nevada. JB argues that California, which has half the Colorado River basin’s population and the bulk of its agricultural activity, has been doing its part to be efficient with water, and other states need to follow its example. Last summer, Imperial Valley farmers agreed to leave their alfalfa fields fallow during the hottest part of the year, to conserve Colorado River water, in exchange for federal payment. “California gets it done,” JB said, on a public panel at the conference. He and the other lower basin states want the upper basin to cut their water usage if need be. He wants to avoid litigation over the river, which, if historical lawsuits foretell anything, could last the rest of his life.

I kept a mental list of terms I’d never heard before. Water masters and CRSP units and water-storage accounts and water credits. Water was bought and sold and saved, claimed and reclaimed. There was beneficial use to water, and abandonment of water, the doctrine of prior appropriation, otherwise known as “first in time, first in right.” The doctrine of public trust. The “virgin flow” was what happened when a river was allowed to run naturally. There was even water court.

The Colorado River starts as snowmelt in the Rocky Mountains and winds 1,450 miles through the Southwest. Centuries ago, it was a wild and muddy and biodiverse river, but as settlers came to the arid west, they dammed and diverted it. It turned blue. In 1922, the federal government apportioned the seven states (not Mexico or tribal nations) fifteen million acre-feet of water to divide among themselves annually; they believed the river carried as much as twenty million acre-feet of water. That year had been unusually wet, and normally, the river averaged only fourteen million acre-feet of water a year. Today it’s more like twelve million, and that initial water flow miscalculation is at the root of the Colorado River’s crisis. The river should flow into the Gulf of Mexico, but drought—plus a series of aqueducts, dams, and reservoirs meant to divert water for agricultural and urban use—have prevented the river from reaching its terminus. Now by the time it gets within a hundred miles of the ocean, it’s reduced to a trickle.

A century after the original Colorado River Compact was signed, Lake Mead, the country’s largest man-made reservoir, reached its lowest level ever. Vegas didn’t see rain for two hundred and forty days. Bodies, some decades old, starting surfacing in the reservoir. Observers blamed the Mob. Lake Mead got within two hundred feet of “deadpool”—the level at which the reservoir can no longer release water downstream. In 2023, it finally rained. Lake Mead was no longer in critical condition, but the West is still dry.