The Paris Review's Blog, page 16

January 9, 2025

The Illustrated Envelopes of Edward Gorey

Tom Fitzharris and Edward Gorey met one afternoon in 1974 when Fitzharris, long a fan of Gorey’s books and illustrations, bumped into him outside of the Town Hall, the performance space in Midtown Manhattan. Gorey—in his trademark fur coat, long beard, and sneakers—was immediately recognizable. The two struck up a brief but intense friendship. When Gorey was in New York, they met frequently, especially to go the ballet—Gorey planned his time in the city around the New York City Ballet’s performance schedule. His summers were spent in Cape Cod. It was in August of that year that Gorey began sending Fitzharris mail, richly illustrated both inside and out. Reproduced below are four of the fifty notes, quotations, and letters Fitzharris received over the course of their correspondence.

***

***

***

From From Ted to Tom: The Illustrated Envelopes of Edward Gorey , edited and with an introduction by Tom Fitzharris, to be published by New York Review Books in February.

Edward Gorey (1925–2000) was born in Chicago. He studied briefly at the Art Institute of Chicago, spent three years in the army, and attended Harvard College, where he majored in French literature. His many books include The Unstrung Harp, The Curious Sofa, The Haunted Tea-Cosy, and The Epiplectic Bicycle.

Tom Fitzharris was a close friend of Edward Gorey in the seventies. He currently lives in New York City and East Hampton and gives tours at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

January 7, 2025

A Diagram of My Life

GERALD MURNANE WITH HIS WIFE, CATHERINE, IN BENDIGO, 1989.

In his Art of Fiction interview, published in our new Winter issue, Gerald Murnane shows his interlocutor, Louis Klee, the chart he used until the mid-sixties to map out the major events and memories of his life—including his birth, James Joyce’s death, his childhood moves around the suburbs of Melbourne, the advent and return of personal crises (“nihilism,” “disaster,” “recover,” and “back to nihilism,” in one short stretch of 1960), his discovery of the writer and theologian Thomas Merton, his forays into poetry, and his courtship with the woman who would become his wife. From our interview:

MURNANE

Now, see this colored chart? Represented by about twenty-five colored lines is a diagram of my life. Gray is for vagueness. Everything, for me, has to be put in diagram or spatial form. The chart is a means of remembering. “88 River Street South,” that’s my address. Now, there’s when I met my wife. I knew her at teachers’ college a bit. We weren’t interested in each other then. But I met her again at the start of ’64. “C.L. 1”—that means the first time we went out together, in the middle of ’64. See there?

INTERVIEWER

Yep.

MURNANE

Right. And then all these lines are events in our courtship. And our courtship was a bit rocky. We separated at one time—it was her choice. And then, “Engagement to C.M.L.” All of them from then on are “C.M.L.” “At Brunswick with C.M.L.” “Marriage to C.M.L.”—then I abandoned the chart.

INTERVIEWER

Why is that?

MURNANE

Let’s say I’d struggled, as a person, to find out what the whole thing was about, and then I found somebody I was able to talk to, found someone to listen to me. I thought my troubles were all over.

A friend of the Review, Matt Benjamin, made the six-hour drive from Melbourne to Goroke, the rural town in Australia’s West Wimmera plains where Murnane lives, to scan the pages below.

Gerald Murnane was born in Coburg, Australia in 1939 and is the author of ten books of fiction.

January 6, 2025

Making of a Poem: Hua Xi on “Toilet”

For our series Making of a Poem, we’re asking poets to dissect the poems they’ve published in our pages. Hua Xi’s poem “Toilet” appears in the new Winter issue of the Review, no. 250.

How did this poem start for you? Was it with an image, an idea, a phrase, or something else?

While I was writing this poem, I was going back and forth from the U.S. to China to take care of a family member. There was a lot of “going” in my life. I was thinking a lot about things that would be “gone” soon.

I think the word go has a lot of depth. It means to go somewhere and it also means to use the bathroom. People will say “I need to go” to excuse themselves politely in a social setting. There’s a feeling of freedom associated with the term that’s somewhat illusory, since the verb by itself, lacking an object, does not actually “go” anywhere at all.

Were you thinking of any other poems or works of art while you were writing?

I used to read a lot on the toilet as a child, so the toilet is very much associated with literature for me. While I was writing, I thought of the first pages of To Live by Yu Hua, which has a scene where a man is trying to shit into a manure vat and his legs are frail and shaking. I’ve actually only ever read the first few pages of the book, but that image stayed with me. Later on, when I was editing “Toilet,” I remembered a passage in an essay by Tanizaki Jun’ichirō, where he talks about the beauty of Japanese toilets. That helped me realize that the peacefulness of a toilet setting must have been experienced by a lot of people over time, not just me, and could be considered a communal feeling. The toilet is a nice place to read because, I think, it mimics the private solace that a book offers; it’s like a personal cubicle where each person can be alone with their own imagination.

I was also writing “Toilet” alongside other poems about different household objects, because I’m working on a manuscript made up entirely of “object poems.” I had to think about how a toilet poem should be different from a table poem or a chair poem, for example, and those differences clarified the poem for me. I decided that a toilet poem should feel a little elegant and clean but at the same time gross.

Did you show your drafts to other writers or friends? If so, what did they say?

I did. A friend put a Post-it note with the last line of the poem above her toilet, which really made me laugh. I used to tell her to think of me when she peed. Later on, I started texting friends, “Let’s pee together soon” or “Pee well” as a joking way of saying “I miss you.” Another friend of mine put a “Reserved” seat placard on my toilet when she visited my house. That was very important to me as well, and I keep it there. There’s something of those friendships in the poem, which I think gives it its sense of humor.

But this is also a sad poem. There’s a lot of secrecy and privacy in the act of peeing. There’s a sense of shame and of the relationship to the body, which is a carrier of all this familial and historical trauma. I had to find a new relationship to beauty, was what I felt about poetry then. When I’m going through a hard time, there’s sort of a refrain in my head that repeats—something along the lines of, I want to live a beautiful life but I can’t help but notice there is something fundamentally disgusting about it all.

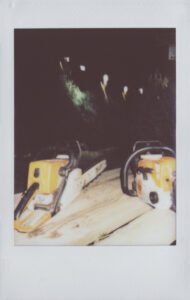

Recently, I started taking photos on 35mm of public bathrooms in both China and the U.S. I think these images eventually feed into my writing. Below are a couple taken in Nanjing. I like how you can see the seasons in them—some of these were taken near the end of summer, so you can still see flowers blooming, or that the sun is really bright outside.

Hua Xi’s poems have appeared in The Nation, The New Republic, and elsewhere. She is a Stegner Fellow at Stanford.

January 3, 2025

Battling Pictures, Equality, Inequality, and Vivien Leigh

Each month, we comb through dozens of soon-to-be-published books, for ideas and good writing for the Review’s site. Often, we’re struck by particular paragraphs or sentences from the galleys that stack up on our desks and spill over onto our shelves. We often share them with each other on Slack, and we thought, for a change, that we might share them with you. Here are some of the curious, striking, strange, funny, and wonderful bits we found, in books that are coming out this month.

—Sophie Haigney, web editor, and Olivia Kan-Sperling, assistant editor

From Antonio di Benedetto’s novel The Suicides, originally published in Spanish in 1969 and newly translated by Esther Allen (NYRB Books):

Leaning forward, I scrutinized the photos. Each showed a human body, fully clothed, lying on the ground. “I see that all three are dead,” I said.

“That’s not a particularly clever response.”

I could tell the biting tone was a warning. I needed to see better, and faster.

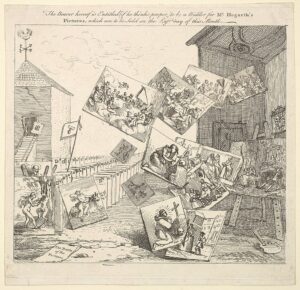

William Hogarth, The Battle of the Pictures, via Wikimedia Commons. Public domain.

Peter Szendy’s For an Ecology of Images (Verso) discusses “iconomies” of images: picture markets, places where images circulate and compete economically. It includes an extended commentary on William Hogarth’s curious 1745 etching The Battle of the Pictures, reproduced above:

The scene in The Battle of the Pictures is that of the auction market where one seeks—sometimes in spectacular or acrobatic fashion—the point of equilibrium between offer and proffer, the best price. But, on the other hand, the engraving also asks us to think about something else, through its near disappearance of human agents and its infinite multiplication of images (letting them proliferate until the image’s own vanishing point). It takes us to the limits of the iconomic market and points to what lies beyond and outside it.

Equality (Polity), an edited conversation between the economist Thomas Piketty and the political philosopher Michael Sandel conducted in May 2024 at the Paris School of Economics, begins with the following remark from Piketty:

Let me first state that I am optimistic about equality and inequality.

From Saidiya Hartman’s “Crow Jane Makes a Modest Proposal” in Five Manifestos for the Beautiful World (Duke University Press):

Like the quiet storm, [Jane Crow’s] modest proposal is easy listening, nothing but legible speech without any discordant tones or ugly feelings; it is assimilable, digestible, delectable as good negroes are wont to be. … No fuck it, no burn it down, no complete program for disorder, no riot, no unrepentant destruction. Just this metaphorical aptitude, this plasticity, this figurative capacity or talent for becoming whatever is required or nobody at all, just the tender gift of reproductive labor in service of the order, the embrace of her beautiful humiliation, the betrayal of her volition, the dulcet tones of submission, the vow to wait, to keep waiting and waiting until oblivion, the propensity to endure until hardly any of us are left standing, just the appeal father may I, master may I, man may I …

From Lyndsy Spence’s biography of Vivien Leigh, Where Madness Lies (Pegasus Books):

‘Oh, the bliss of not having to go mad, commit suicide, or contemplate murder,’ Vivien Leigh told the waiting reporters as she stepped off the aeroplane and on to the airfield in Colombo, Ceylon. … She was exhausted after the long flight by way of London, Rome, Beirut, Bahrain and Bombay. Her leading man, Peter Finch, took her by the arm and escorted her through the sea of reporters and curious faces who hoped to catch a glimpse of the star. The humidity was suffocating and the heat swept over her like a furnace. She stopped to catch her breath, before adding, ‘My character is … a normal healthy girl.’

December 23, 2024

Christmas Tree Diary

Friday, November 29, 2024

27 degrees

A twelve-hour opening shift and I dripped snot on the first customer’s debit card. But that’s Christmas tree season. Other than the barrel fire, there’s no place to get warm, so I wore fleece thermals with jeans on top, pockets full of pine needles already. Plus a hoodie and a blanket-lined denim trucker jacket that passes for hip. Ty doesn’t wear a coat, just three Carhartt hoodies on top of each other. Jack wears a knee-length puffer jacket from Goodwill. Brian wears a hoodie with the hood cinched tight around his face and his beard poking out. He looks the most like an elf. He also looks the most like Santa. Kids like to bring up one or the other. Sometimes we try to wear gloves, but they get caked in sap.

People are always asking why landscapers and construction workers are selling Christmas trees. The short answer is that trees are heavy and construction workers are strong, and that winter is cold and we’re mostly cool with that.

We’re set up across from a gay club in a rich part of Pittsburgh. Our boss started selling Christmas trees in this lot fifteen years ago. From that came a seasonal nursery selling flowers and shrubs in the summer, which led to a landscaping service, which became full-service contracting, which is why now you have a bunch of carpenters temporarily assigned to tree duty. We make good money in tips.

I work in the nursery during the warmer months and on jobsites when the plant business slows. Even I’m surprised that it’s here, just a rickety greenhouse and a few sheds dropped onto a sloping city lot in the neighborhood where the Mellons and Carnegies once built their mansions. Now luxury apartments, dorms for adults, are encroaching. It feels like one might rocket up from the ground at any minute, launching us out into the burbs, where rent’s cheaper.

The nursery’s vibe has been variously described as crunchy, folksy, chill, granola, and “aesthetic”: hand-painted signs fading in the weather, a long, rusty pergola full of wreaths made with tree trimmings and some handmade ornaments dropped off by their makers. We spread a ton of mulch, lean the trees on X-shaped racks scabbed together with scrap lumber, hang some floodlights, light a few barrel fires, and crank Casey Kasem’s Christmas Top 40. The same songs every day. Unless Brian’s working, then it’s Latin American Navidad songs or Christmas ska. It keeps him upbeat in the cold.

People want to believe that we grow the trees ourselves, but a thousand came from North Carolina on a semi driven by a Russian man who backed down the narrow street, slid out the truck with a cigarette in his lips, gestured to our fucked-up little city, and said, “This is craaazy, man.” The other trees come from farms in Western PA—broad, rolling hills so thoroughly strip-mined that little else will grow.

Only serious tree-heads come on opening day. This afternoon, an older woman walked through the entrance and immediately started freaking that all the good trees were already gone. I told her we had at least a thousand left.

“But I need a fat tree,” she said. “I don’t like fat people. But I like fat trees.”

Then her huge husband came in behind her.

Some people need to be shown something in order to truly see it. These customers tend to have a sleepy cast to their eyes. So you pull a tree from the rack, slam the butt down onto the ground to droop the branches (this is a pro trick), and hold it next to an inferior tree. I try not to compare two nice trees because it only makes things worse. That’s how I found her a good fattie.

I carried the tree through the narrow aisle of mostly identical trees and over to the operating table near the small parking lot where we load trees onto customers’ cars. I checked my blind spot for children and idiots and fired up the chain saw. This is the part most customers like. Sometimes they hover over the low table, like medical students, and we have to shoo them back. Other times they’re shocked by the noise and exhaust and disappear into the trees, as if the saw might jump from my hands and chase them down.

I nipped the bottom branches and made a fresh cut on the trunk to help the tree absorb water. Because they were watching, I ran my fingers over the fresh cut and nodded in thoughtful approval.

“It must be delivered during the day,” the husband said. “Not after dark.”

“Last year, you brought the tree at night, and a bat got inside our home.”

“That can’t happen again.”

“Yes,” I said, pretending to take notes. “No bats.”

No tip.

Saturday, November 30

23 degrees

Yesterday I made enough money in wages and tips to pay my half of the monthly mortgage.

This morning I found a pine needle in my butt crack.

Sunday, December 1

28 degrees

My favorite customers are young roommates because, without the weight of shared traditions, there’s no need to measure their tree against others, and because they wander in stoned or on impulse, taking selfies and negotiating their choice with a type of honesty I don’t usually see in couples.

My next favorite customers are tipsy old gays from the bar across the street, because they buy their geraniums from me in the spring, and because they like to tell me about parties they’ve thrown or gardens they’ve grown, and because when I rev up the chain saw they pretend it’s novel, as if to say, You play your part and I’ll play mine.

The best tippers are Patagonia-core couples, who always have roof racks on their Subarus and Australian shepherds in the back named River or Sequoia.

The next best tippers are Tesla bros. They get their trees delivered because you don’t tie a tree on a Tesla.

The worst tippers by far are lesbian couples, who are unimpressed by our chain saws.

The next worst tippers are people wearing scrubs. I don’t know why, but it’s true.

Having some jokes can help. Brian jostles the tree after it’s tied onto the roof and says, “Just keep it under ninety.” I like to tie a tree to the top of a car and say, “This is my twenty-mile-per-hour knot,” or “This is my forty-mile-per-hour knot.” Sometimes I take a little piece of twine, hand it to a child inside, and close the other end in the car door. I say, “This is holding the tree to the roof of the car. DO NOT let go.”

Their eyes usually go wide looking back at me, a weird little man with long hair and sap on his face, climbing all over his family’s nice car, tying knots with his filthy hands.

These are mostly rich city kids with no sense about anything. We have to pull them away from the fires and beg them back when using the saws. They go feral around the trees. They come in through the front gate, ignoring all the cheer, and take off weaving through the narrow rows of trees, tripping in the mulch and snow, thinking that maybe they’ve been let free in a tiny forest. They drop to their knees and crawl inside the racks, small tunnels of lumber and foliage, and when I pull a tree from the rack I’ll find a snotty, grinning face staring back at me from the darkness.

Monday, December 2

30 degrees

People who buy small trees are used to imperfection, but people who buy huge trees are used to getting what they want. This is a problem because our big trees are somewhat fucked up.

Every ten-footer I’ve unwrapped this year has had a weird bare spot about two feet from the base, a gap no ornament could cover. Deer don’t usually bother Frasier firs, but these look like scars from deer browsing. These deer were browsing in the dead of winter. They were browsing because they were starving.

Tuesday, December 3

30 degrees, snowing

The most annoying man on earth was wearing a Matisyahu hoodie and a pair of white sneakers, freshly scrubbed. He had three sons in prep school sweats and broccoli cuts who ignored him and stood around the fire, flashing their phones to each other and laughing in that particularly sinister way that teen boys laugh.

“Two trees” was the first thing he said to me. “The big one, ten feet at least. We put it outside, you know? So it’s got to have a real natural look.”

I grabbed the first tall tree I saw and showed it to him.

“Too scraggly.” He looked like he might have a fever. He was moving all jerky and weird, a contagious type of anxiety. Brian and I found him two that “would do.” I tossed the big one onto the operating table and started to cut. But then he started tapping me—a man wielding a chain—on the shoulder, shaking the branches he wanted trimmed.

Soon he moved over to Brian’s table and was lunging all in and out of Brian’s blind spot, sticking his hands near the saw, saying, “CUT THIS. AND THIS. NOT THAT.”

Eventually he threw his hands up and said, “That doesn’t look remotely straight!”

He walked into the aisles and by the time I had the trees tied to his roof he’d found a third tree he wanted wedged in the trunk.

“Tell me the price,” he said. “We might have to put some of these back.”

The tallest trees are $120. Seven-to-eight-foot trees are $105. Six-to-seven-footers are $85, five-to-sixers are $65, and tabletop trees—three-foot tops cut from larger trees, like baby carrots—are $45 with a red plastic stand. Reasonable people tell me these are decent prices.

I told the guy it’d be $270, plus a $1 credit card fee and tax.

“That’s completely insane,” he said. “But what can I say? I love trees.”

Wednesday, December 4

27 degrees

Today an eighteen-month-old baby with perfect angel cheeks sang “Jingle Bells” to me from her car seat while I tied a tree to the top of the newish Volvo.

Later, a little boy walked over to the barrel fire, looked inside, and said, “Orange flames. Poor combustion.”

Brian said, “You’re a smart kid.”

He said, “I know.”

Saturday, December 7

43 degrees

Some people want trees that look like trees they’ve had in the past. They hold up their phones to my face and say, “Got any like this?” And if I do, they’re grateful and kind.

Other people buy trees with bald spots or crooked tops because they feel bad for ugly trees.

Some people lose their minds for trees with lots of cones, or skinny trees, or trees that look “lime green.”

One of the guys told me that a few years ago, a couple picked out a tree with a bird’s nest in it and the nest flew off in the delivery truck. They sent a long, agonized complaint to the nursery’s email address, explaining that they’d suffered a miscarriage earlier in the year. When they saw the nest in that tree, they knew the coming year would be better. And now, they said, we had ruined their Christmas.

Sunday, December 8

53 degrees

New York Disease is when people have to tell you they used to live in New York. A guy in a camel-hair coat told me he lived in New York for eight years. In New York, apparently, you just have to carry your own tree home. I heard about it from a woman yesterday. And again from a couple last week. You wouldn’t believe how many New York blocks they’ve carried trees.

People with New York Disease need to share their thoughts on Pittsburgh, too. And you know what? They actually really like it, so far! They like the slower pace. They could never have a yard like theirs in Park Slope. Or twelve-foot ceilings. And it’s so neighborhoody. And it’s so down-to-earth, still really working class, you know?

Monday, December 9

47 degrees, light rain

Today everyone was kind and lovely and none of the smoke from the barrel fire got in my eyes.

Tuesday, December 10

42 degrees

There is nothing a cis man hates more than watching his wife watch another man use a chain saw. I find ways to ask if they have a chain saw at home—they tip me better to assert dominance.

Wednesday, December 11

38 degrees but windy as fuck

If I see someone looking at an ugly tree, I walk by and say, “I was thinking about taking that one home if nobody else got it today.”

And poof, it’s sold.

Saturday, December 14

42 degrees

I brought in some hot dogs and we cooked them over the barrel fire until they blackened and split, hissing steam that smelled exactly like summer.

We discussed:

Is Die Hard a Christmas movie?Is Eyes Wide Shut a Christmas movie?Is a tree still a tree after it’s cut?Does that make a Christmas tree a corpse?Is a dead body a person?I thought about this woman from a few days ago who wheeled into the lot right before closing time and smacked into a row of trees with her car. She jumped out all panicked, saying, “Did I hurt them? Did I kill them?”

I said to Brian, “Wait until she finds out we already cut them down.”

Sunday, December 15

37 degrees

We’ve sold most of the trees. Pine branches piled high as a van by the greenhouse and half a dumpster full of twine, straight to the garbage patch. My face is all leathery and red. So far I’ve made like twenty-five hundred bucks.

Earlier a lady walked in, stuck her face into a tree, and whiffed. She was holding her hands under her chin, like a prayer, and she shimmied with joy. People are always smelling the trees or the fire, then saying something vulnerable about their kids, or their parents, or a farm that no longer exists. But I like the smell of the chain saw the best. A punchy gasoline smell with a tinge of hot oil, wood chips, and burnt metal.

I grew up out in the country, and my dad used to heat our house with firewood. He’d load me and my sister into his truck and drive us out to the woods to cut. We’d run around with the dog while he worked. I loved the smell of the saw, the high whine of it, the damp trail of wood chips that seemed to follow him everywhere he went. But soon I got old enough to help. Old enough to hate it. Old enough to see it as something rednecks did. When I was sixteen, my dad took me to the little patch of woods we owned and showed me a dozen nice hardwood trees he’d spared. He’d saved them because they were valuable. And now we were going to sell them to help pay my college tuition, or at least buy my textbooks.

I’ve never tried to write about that. It’s just so sincere, so folksy. Like a fable. But now it’s Christmas and I want everyone in the lot to come and sniff the chain saws.

Jake Maynard is the author of the novel Slime Line. He lives in Pittsburgh.

December 20, 2024

The Best Books of 2024, According to Friends of the Review: Part Two

Wilhelm Amberg, Reading from Goethe’s Werther (1870), via Wikimedia Commons. Public domain.

Colored Television by Danzy Senna: among its subjects (not in order of importance) are LA, the vagaries of a writer’s life, and race—often in terms of a word that, coming from New Orleans, I am deeply familiar with, but which I thought I was not allowed to use. Until Danzy Senna said it was OK. More than OK. She prefers it to any less specific word. What is this word? Mulatto. The book’s heroine is writing a gigantic historical novel on this topic, which her husband describes as the “mulatto War and Peace,” and which is destined for failure—a failure resonant with universal poignance. Danzy Senna’s novel is deeply hilarious, though the passages I highlighted are not: “She’d never understood so profoundly how much being a novelist was at odds with domestic life, with sanity. … That kind of writing had no beginning and no end. It just crept around the house, infecting every element of family life.”

The new (posthumous) Gabriel García Márquez novel, Until August (translated by Anne McLean), which he did not think was good enough to publish, is so good that its essential García Márquez qualities put one to shame—the quality of his vision, the quality of his prose, of his emotional capacity, and basically of his entire life. No, it isn’t his best, but I reveled in the memory of a master whose mere scraps I scarfed up adoringly, such as: “torrential geniuses with short and troubled lives,” as he remarks of Mozart and Schubert.

—Nancy Lemann, author of “ The Oyster Diaries ”

Damir Karakaš’s Celebration, translated by Ellen Elias-Bursać, begins at the end of World War II. Its four sections—“House,” “Dogs,” “Celebration,” and “Father”—move from 1945 to 1935, then 1941 to 1928, and follow Mijo, a man whose yellow-brown uniform marks him as a member of the recently fallen Croatian fascist organization of the Ustaše. Exiled to the forest overlooking his home, a small Croatian village, Mijo awaits the moment when he can rejoin his family. It’s a novel that kept its hold over me long after I put it down.

—Ena Selimović, translator of Abdulah Sidran’s “ Scraps ”

Tara Selter, the protagonist of Solvej Balle’s On the Calculation of Volume (translated by Barbara J. Haveland), is stuck on the day of November 18, which she repeats endlessly. Trapped in time, she makes an official project of it. Looking becomes ritualistic. The day’s relentless sameness is double-checked, until she can predict the movement of birds. Wonderfully, this is the first book in a series of seven.

—K Patrick, author of “ Blue ”

Jamie Quatro’s Two-Step Devil is the rare contemporary work of fiction that takes the Deep South, with its essentially biblical figures of thought and speech, as seriously as the region should be taken. Set in 2014, the novel combines the lessons of literary Modernism with a kind of tricky gritty realism to produce a fable about sex trafficking in rural Alabama, one which, by its end, becomes a plaintive, painful, and surprising defense of the right to abortion. It is a prophetic book about the recent past and I have not read anything like it for a long time.

—Alec Niedenthal, author of “Schändung (Desecration)”

Mourning a Breast, the Chinese writer Xi Xi’s account of breast cancer, is perhaps the only illness memoir to address head-on how difficult it is to choose books to read in the hospital. (“Perhaps Dostoyevsky’s Crime and Punishment? But that was too heavy to hold. What about Donald Barthelme’s City Life? But Barthelme had passed away from blood cancer; I didn’t want to read him just now.”) The book, translated by Jennifer Feeley and first published in China in 1992, switches from short essays to stretches of dialogue, sometimes addressing the reader directly, like the narrator of a guidebook, sometimes following Xi Xi’s thoughts so closely it’s as though she isn’t worrying about the reader at all. Intimate, charming, and open, it is a book to be enjoyed in sickness and in health.

—Madeleine Schwartz, advisory editor

Morgan Võ’s debut poetry collection, The Selkie, is a wonderful, sometimes very funny book about the proximity of ordinary life to the production of mass death. It stars “the monger.” He sells fish. Are his wares alive? Not exactly, he explains, they just “keep / eating and shitting.” The monger mistakes a fish for a dollar bill and so it goes into circulation, gets worn thin, torn in two, then taped back together. Together, the fish and the monger do durational performance art, à la Tehching Hsieh and Linda Montano in Rope Piece. The monger shows the fish a DaBaby meme. In 2024, I read Võ’s poems again and again. I’m obsessed with the way they seem to search, as we all do, for words for extreme violence. In one, the monger goes to see Anthony Bourdain speak at a local library. “what do i have left / to say?” Bourdain-in-the-poem asks. “what do i do now?” In another, a fish corpse is found to contain a delicate scroll that reads “after // all // you // know // and // tibet // is // still // not // free?”

—Silas Jones, author of “Regular Decision”

Mariana Enríquez’s new story collection, A Sunny Place for Shady People, seethes and roils with a body horror that evokes the films of Richard Kern and David Cronenberg. Her monsters are real: misogynists, corrupt dictators. There is a surreal and visceral magic to these stories of cruelty, sexual violence, and poverty, brilliantly captured in Megan McDowell’s translations.

—Frank Wynne, advisory editor

La llamada by Leila Guerriero: I wasn’t expecting my favorite book of the year to be a crónica. I didn’t think it possible for a story so contemporary, so political, and so steeped in reality to be infused with the intensity of a thriller and with such poetic force. La llamada (forthcoming in English translation from Pushkin in spring 2025) is a master class in writing an impossible book. In our world of radicalisms today, few dare to explore with such tenacity the gray areas and contradictions that make up who we are. A hundred years from now, we’ll still be talking about this tour de force of Leila Guerreiro’s.

—Samanta Schweblin (trans. Alejandra Quintana Arocho), author of “An Eye in the Throat”

One of my favorite books this year is the late Dubravka Ugrešić’s A Muzzle for Witches, translated from the Croatian by Ellen Elias-Bursać and published by Open Letter Books. Ugrešić—the Neustadt International Prize for Literature–winning author of seven books of fiction and six essay collections to appear in English—was born in the former Yugoslavia, but when her homeland was riven by war in the nineties and she was forced into exile for her antinationalist views, she became a renowned if reluctant icon of resistance. Structured as an interview with the Bosnian-Herzegovinian theorist Merima Omeragić, this slim volume allows Ugrešić to expound on themes that have animated her work throughout her career—of exile and belonging, of nationalism and misogyny, of history, literary culture, and technology. She decries the scourge of autofiction that has writers “writing their own hagiographies,” comparing this self-aggrandizing and attention-seeking impulse to that of influencers and serial killers. “If literature is to survive,” she says, “it must move into a zone of invisibility and go underground.” But the book is not lacking in hope: Ugrešić sees literature as fundamentally about and fundamental to human connection. “One real reader,” she writes, “is enough to persuade me of the meaningfulness of my work.” Ugrešić is a brilliant thinker, a consummate stylist and literary trickster, and I can think of no better writer to read and recommend in these frightening and uncertain times.

—Will Vanderhyden, translator of Rodolfo Enrique Fogwill’s “ Passengers on the Night Train ”

Sandhya Mary’s Maria, Just Maria, translated from the Malayalam by Jayasree Kalathil, is about a “mad” little girl who is baffled by the world’s compulsive need to divide everything and everyone into normal and abnormal. Maria’s world is inhabited by a philosophizing dog; a grandfather who takes her along on his toddy-shop rounds; dead, “mad” ancestors; a jealous patron saint who gives his followers strange dreams; and other such audacious characters. She critiques, with great humor, joy, and innocence, a range of society’s absurdities, including competitive exams in schools, elections, and the hypocrisy of liberal politics. The novel is a call for a more inclusive, kinder world, yes. But it’s also a reminder that perhaps an appropriate response to reality is to go insane.

—Deepa Bhasthi, translator of Banu Mushtaq’s “Red Lungi”

This year, I often joked to myself that I was “off books.” Nothing, from Neil Postman’s Amusing Ourselves to Death to a rereading of Brideshead Revisited, was cutting it. Maybe it was my ambient anxiety about the state of the world, an imminent breakup, or the seventy-five-degree fall days, but all I could take in were science podcasts about lucid dreaming and white noise tracks on loop. Into this fog slipped Halle Butler’s Banal Nightmare. The novel, Butler’s third, is the story of Moddie, an overeducated and underachieving thirtysomething who, following a seismic breakup, abandons Chicago for her Midwestern hometown, where she tries to get a grip on her life. It’s a sharp book, with painfully real characters and perfectly pitched sentences. It’s also cruel, comically so. At first, it left me feeling more depressed, and then (somehow) happy. Happy that I wasn’t as constitutionally fucked-up as Butler’s gang of misanthropes, and happy to be reminded that fiction like this—so funny and smart—is there to pull me out of a state, make me feel less alone.

—Camille Jacobson, engagement editor

In the spring, before I began teaching and lost the capacity to read anything more robust than a play (no offense to plays), I read Isabel Waidner’s second novel, Corey Fah Does Social Mobility, whose eponymous protagonist has just won a prestigious literary prize for the Fictionalization of Social Evils. And yet the trophy itself eludes him: neon beige and UFO-like, it appears in his peripheral vision, always just out of reach. The novel’s narrative engine is fueled by the conceit of mythmaking. Everything, in Waidner’s treatment, is topsy-turvy. Corey Fah finds an unlikely companion in Bambi Pavok, who, like the Disney character, emerges from a forest, but with a very unorthodox background (and anatomy): she is the child of a wasteman and an alcoholic, with eight spider legs where we might expect four dainty hooves. The novel is wild, smart, and very fun.

—Maya Binyam, advisory editor

December 18, 2024

Learning to Ice-Skate

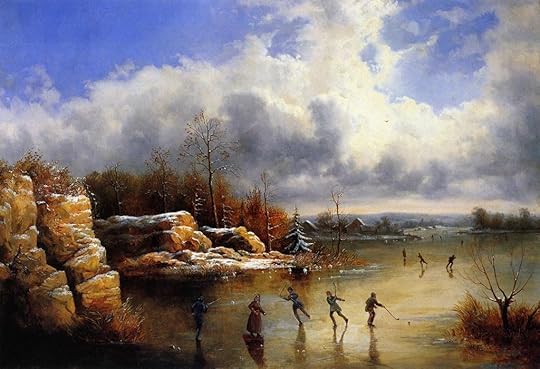

William Charles Anthony Frerichs, Ice Skating (1869), via Wikimedia Commons. Public domain.

In Stockholm it didn’t snow on Christmas or New Year’s Eve or at the beginning of January. The days were gray and, in the afternoon, just before it got completely dark, there was often a dank glow that turned the sky brown.

That December, we bought some cheap skates and went one night—in midwinter it’s most accurate to use the term one night even when describing something done during the day—to skate in Vasaparken, where they flood the grass pitches with water, turning them into a huge floodlit rink that never closes. I’d skated only a couple of times in my life and so many years ago that I’d lost any muscle memory my body might have had.

It was my first winter in Sweden. Before leaving the house, I watched some YouTube videos that explained the theory of ice skating. I enjoy tutorial videos. They’re a genre in their own right, the perfect fusion of two words with the same root: genre and generosity. People from all over the world teaching you how to change blinds, recover objects lost in washing machines, make a hem, or repair scratches on the kitchen counter. In spite of the evident goodwill of the people uploading the videos, it’s obvious that some tutorials are more useful than others. No one there can teach you how to skate.

I also watched a video showing how to ride a bicycle, which might sound utterly useless but was very moving: they filmed an adult woman who’d never learned to ride a bicycle and who, by the end of the video, was able to go a few feet on her own without any help. The happiness on her face as she rolled along reminded me of a moment in Michitaro Tada’s Karada, where the author recalls his baby standing up on her own for the first time. Tada writes that he never again saw an expression of such complete happiness as that of his daughter at that moment. Standing and walking on your own! Two of the most difficult things we ever have to do in our lives. We learn the trickiest, most embarrassing tasks in our early years, which is probably why we don’t remember doing so.

When I first stood on the ice in my skates, I had no stability. Your deepest urge is to keep both feet in contact with the surface, but to move forward on skates you have to do precisely the opposite. Vasaparken doesn’t have any walls or railings to cling on to. As soon as I was out on the ice, I was alone, stranded in a void. I hadn’t felt physical fear like that in a long time, the fear of doing something that my body didn’t know how to react to. But scared as I was, I can’t say that it was an unpleasant experience.

People skated past me quickly, enjoying the sensation of gliding along. One guy had a speaker in his backpack and was skating to reggaeton and vals. I thought that seeing all these people so obviously more skilled than me would make me feel bad, but to my surprise, I had the opposite reaction: as I saw them glide over the ice in long thrusts, I had the pleasant sensation that we were members of the same species. Anything they could do, I could do too. Of course, they’d been doing it for years. It was the same with language: if I’d been born in Sweden, I would be able to speak Swedish perfectly. What had happened to my infant body, which had come equipped for any potential human scenario?

I circled the rink a few times, and felt an entirely new sensation. As I clumsily made my way along, I suddenly felt roasting hot, while my heavy winter clothing felt as though it had been soaked in ice-cold water. This must be what cold sweat means, I thought.

***

Later, in January, it snowed and snowed and I was able to distinguish between three different kinds of snow, although I had no idea whether they had different names or were simply the same phenomenon happening at different intensities.

The seagulls and crows that flew over the city in the summer and autumn had disappeared. The only birds you see in winter are magpies; I saw two from the window, flying over the same roof. It’s commonly held that they steal shiny objects to take to their nests and although this has never been proved, I did once see a magpie with a pull tab in its beak.

They’re pretty, each with a streak of blue feathers on its back, and when they fly high they close their wings for a few seconds and look like twigs flying through the sky.

***

Three weeks after my first attempt at Vasaparken, we went to skate on a frozen lake for the first time, Rönningesjön, in the northwest of the city. We took the 11:06 A.M. train from Östra Station, right by the entrance to the university campus.

From the railway you can see fields, trees, and dry plains covered in frost, and every now and again a huddle of small houses made of red and yellow wood with white roofs whose gardens are as bare as the branches of the birch trees. Who could imagine that these are the same fields that explode with life in summer? Winter gives us a lesson in humility. It forces us to believe in the existence of things we can’t see.

A friend had bought some wooden stakes tied to a string with a plastic whistle that you wear around your neck. If you fall into the water, you stick the stakes into the ice to pull yourself out before blowing on the whistle to call for help. I heard that if you fall in the water and get disoriented under the ice, you shouldn’t swim toward the light but where you see a dark dot. That dot is the hole. The mere idea brought back the cold sweats.

The surface of the lake was smooth and completely firm, which made me feel safer. Underneath the thick layer of ice, everything was black: the water. For the first hour, I skated very slowly, sweating profusely. I fell three times and once, smacked my hand and the small of my back. I’d taken the precaution of keeping my backpack on to protect my head if I fell backward. The problem was learning to get back up.

A couple of hours later our Russian friends arrived. To my eyes, they looked like Olympic champions. They could even skate backward. Her skates were black and sculpted like ballerina shoes, not like mine, which were clunky and had plastic strips. As she skated next to me, however, I felt something change. We chatted as we went along, admiring the landscape and sunlight. It was two in the afternoon. A fine, cotton candy–like mist began to fall over everything, but the skies remained clear, blue turning to orange. We were immersed in the silence of the forest. It was all deeply beautiful.

I started to push harder and go faster, and little by little I began to lift my feet. The conversation distracted me from my body and, it seemed, my fear. I had assumed that I’d skate better alone, free of the gazes of others, but that wasn’t true: I got better when I was with other people, when I stopped paying attention to my legs and just chatted, letting my body do its thing.

***

It is February and the light is changing. In truth, it’s been changing for months, it’s always in flux, but recently it’s become more perceptible, to me at least. Last week I said that spring was around the corner and Fede laughed. It’s still just as cold, the temperatures are between -13 and -5 degrees Celsius and it has snowed almost every day in February. But the light is different and that’s enough for you to start thinking about the end of winter.

When it gets very cold, the snow glows at night. The flakes look like crystal and continue to sparkle even when you scoop them up in your glove. It’s a magical effect I’d never seen before and I suspect that it only occurs when the temperature is a long way below zero. Gabriel, our Mexican friend, calls it la nieve del pinche frio (the snow you get when it’s cold as a motherfucker).

We went to skate again on another frozen lake, this time in Hellasgården, to the south of the city. Along the path from the bus stop to the shore, patches of the lake were visible, surrounded by a forest of white birches. In winter, everything becomes achromatic.

As I got closer to the ice and the dock swimmers jump off in summer, which now served as a bench for people to strap on their skates, I felt my heart begin to beat harder and my abdomen and torso were soon drenched. I went out onto the lake hesitantly, but I didn’t fall. The first steps—or, rather, slides—are always clumsy, it’s not easy to get used to that strange friction under your feet. But after a few minutes on the ice, my feet were no longer so reluctant to lift from the floor. Fede was standing a few feet ahead with his arms open the way parents do when their children are learning to walk. I slid over to him and hugged him. It’s a wonderful sensation to feel that one has learned a new physical skill thirty years on from the last. Skating! Something I never thought I’d know how to do or enjoy. Next to us was a father teaching his four- or five-year-old son to skate. The man was about forty-five, the attractive Scandinavian type with grey hair—like the Norwegian writer Karl Ove Knausgård, whom Swedish writers hate. The boy was in one of those padded one-piece snowsuits that make children look like tiny factory workers. He was wearing new skates and kept falling down even though his father had him by the hand. The father moved on a few feet, showing him how to do it, with his hands behind his back and legs bent. The boy was still on the ice. He made progress slowly and with difficulty, but it was obvious that after a couple of sessions he would be moving along much more gracefully than me. I passed by in my slightly clumsy way and the boy stared at me. I was an oddity, an adult who didn’t know how to do what his parents did.

Of all the colors a winter sky can turn, the most beautiful is blue and the most awful is yellow.

Another attempt: this time on a lake in Farsta, to the south. The circumference of the lake made for a long circuit, more than twelve miles, and because everyone else skated faster and better than me I was often left behind, making my way as best I could against a tricky headwind that day. At one point, I stopped for a few seconds to admire the beauty of the landscape around me. I was filled with gratitude at the opportunity to see the forests and frozen lakes. My face stung from the cold and amid my aesthetic rapture, I lost my balance and fell to my knees on the ice. In that moment, I understood that humility and humiliation have their physical place in the metaphorical workings of the body, and that place is the knees. The knees, which bear the weight of the rest of the body when one falls to their defeat.

I was left so far behind and got so tired that I had to take off my skates and put on the boots I had in my backpack to walk back along the path to the side of the lake, stepping carefully where snow had gathered.

***

The light is really beginning to change now, it’s much more obvious in March than February. The days must be as long as they are in November, but the sensation is different, because we’re coming out of darkness. It’s a matter of intensity, like music. There’s still daylight at three in the afternoon and that seems incredible. The worst part is when the snow melts. In subzero temperatures dirty snow is very similar to wet sand; it has the same consistency and color. Now, the temperature has risen by a few degrees and all the streets are wet. One’s shoes get covered in mud and the grit they spread on the sidewalks so people won’t slip. In Sweden almost everyone has dirty shoes. Even if you live in the center, at some point you have to cross a park, patch of mud, or snowdrift. Swedes used to clean their shoes at the door with birch branches. Now everyone takes their shoes off before going into a house. And people prefer sneakers or boots with thick soles even when they’re dressed up or headed out to work. An Italian woman I met once said, “Swedes dress very well but they’re let down by their shoes.” Swedish women prioritize comfort. You see lots of well-dressed women in the city wearing elegant clothing combined with comfortable sneakers or tennis shoes. Once, in a restaurant, I saw a woman arrive in clunky boots covered in snow and replace them with a pair of doll’s shoes she had in her handbag. The skating rinks start to close at the end of winter—another reason why March can be a melancholy month. I worried that I wouldn’t be able to practice my new motor skills again until next year. I wondered whether my body would remember any of it the next time I strapped on my skates, whether my feet would know how to move. Or whether the cold sweats would return, and it would be like the seasonal skills I tried to learn when I was a girl, playing cards in summer, knitting in winter. They were rival crafts that fought for the same space in my brain: when one took precedence, I forgot the other.

I think that the peaks of winter and summer—although they seem convincingly endless in their splendor and apparent solidity—keep the sadness of the ephemeral in their hearts. Their solidity is just an illusion. Right now, I’m not longing for summer but the real winter, which is coming to an end.

The sound of running water is everywhere: all the snow and ice is running down the drains and gutters into the sewers. Everything drips. The spell is broken. For the first time in a long time, I hear the sound of rain.

Translated from the Spanish by Kit Maude.

Virginia Higa is an Argentine author and translator. Her first novel, Los sorrentinos, has been translated into Italian, Swedish and French. Her second book, El hechizo del verano, is a collection of essays about life in Sweden.Kit Maude is a translator based in Buenos Aires. He has translated dozens of classic and contemporary Latin American writers and writes reviews and criticism for various outlets in Spanish and English.December 17, 2024

Issue No. 250: A Crossword

Built by Adrienne Raphel using PuzzleMe’s online cross word maker

To print out the puzzle, click here!

To print solutions, click here.

Adrienne Raphel is the author of Thinking Inside the Box: Adventures with Crosswords and the Puzzling People Who Can’t Live Without Them, Our Dark Academia, and What Was It For.

December 16, 2024

A Sex Memoir

From Interiors, a portfolio by Claudia Keep in issue no. 246 of The Paris Review.

In my novels and memoirs I have written quite a bit about sex, even very outré sex. I’ve always insisted that I’ve approached sex as a realist, not as a pornographer. That is, I like to represent what goes through someone’s mind while having sex—the idle thoughts, the resentful thoughts, the comic aspects of the body failing to meet the acrobatic ambitions of the imagination—and the sometimes enriching, sometimes embarrassing or dull, often distracting or irrelevant or wonderfully intimate and tender moments of lovemaking.

I’m at an age when writers are supposed to say finally what mattered most to them—for me it would be thousands of sex partners.

There is still a prudishness about sex, not only in America but everywhere. Sex and comedy are the two subjects that are never taken seriously, though we think about sex constantly—and about comedy periodically, if we’re lucky, if only in the form of self-satire. I suppose prudishness guarantees paternity, so crucial in keeping bloodlines pure.

Gay men have seldom been candid about their sex lives and are even less so now that they are getting married and fathering offspring. Paternity is not the problem for them so much as respectability. Internet anonymity has facilitated new possibilities of “cheating” and hypocrisy.

It may seem absurd for an octogenarian to be writing a sex memoir, but it could be argued that he has decades of experience to draw on and an unimpeachable point of view, even if the horse he has in the race may have become feeble and hobbled. Because I am in my eighties, have most of my marbles, have been a practicing gay since age thirteen, and lived through the oppression of the fifties, the post-Stonewall exaltation of the seventies and the wipeout after the advent of AIDS in the eighties, the discovery of the lifesaving therapies of the nineties, the granting of gay marriage equal rights in the States in 2015 and the parallel right to adopt children, the brewing storm in the 2020s against everything labeled “woke” (trans people, drag, books, puberty-delaying drugs)—because I’ve witnessed all this drama and melodrama—I’m perfectly situated to view how we got here. The following piece is adapted from one of the chapters of my forthcoming memoir, The Loves of My Life.

The thing about gay life is that you have countless mini-adventures, which years later leave only the faintest grooves on your cortex. The handsome big blond with the sweetest smile and strongest Boston accent I’d ever heard, who wanted to get fucked only and moved out to San Diego, where he caught the eye of many a sailor, got infected with AIDS, and died.

The young Kennedy-style gay politician whom I invited to dinner after yet another bad affair, on the principle that I should shoot high and aim for the top. He came to dinner more than once, we had “sophisticated” (i.e., cold) sex, and he got AIDS and died.

My French translator, a skinny boy with an enormous dick and fat lips and an encyclopedic knowledge of the French classics from Rabelais to Benjamin Constant, called on me in New York and I immediately groped him—which he thought (rightfully) was disrespectful and unprofessional. I couldn’t explain to him how every male in New York was fair game. He got AIDS and died.

Bruce Chatwin. Robert Mapplethorpe sent Bruce over to visit me and we were still standing in the doorway when we started groping each other. I saw him many times after that, in London and Paris, but we never fooled around again. We had gotten that out of the way. Years later he contracted AIDS and died but couldn’t accept that he had such a banal disease and claimed he’d contracted a rare malady in China from whale meat or something. Maybe the subterfuge was caused by his being married to a woman.

The dear friend of mine who knew I was not-so-secretly lusting after him and, one afternoon in Maine, in an exquisite house built by Buddhist monks after their abbot had disbanded them, came into my room after a shower wrapped in a towel and asked for a back rub. I gave him a blowjob. That silent concession sealed our friendship and I never plagued him again. I wish I’d been that generous with older unattractive friends who lusted after me when I was young.

The doughy blond trick my age, thirty at the time, who spent the night gabbing with me after we had desultory sex. At dawn I said to him, “I’ll bet you were raised a Christian Scientist, as I was.” He asked me how I’d figured that out. “Because,” I said, “you’re an optimist and don’t seem to believe in evil. That’s such a fundamental part of Mary Baker Eddy’s beliefs—and her most unsettling error. Worse than her distrust of medicine.”

***

I was raped two or three times by clever older men, although we didn’t call it rape then. Only later did I realize I’d been fucked against my will. One importunate man was an English television producer with whom I’d spent many a social evening in London and New York. He was the sort of stereotypical P. G. Wodehouse gentleman who’d suddenly stop in the middle of the sidewalk, let his eyes dramatically unfocus as if he were having an attack of aphasia, and actually say with perfect articulation, and a look of astonished disbelief, “What?!”

Maybe an Englishman would have known how to reply, but I was disarmed, nonplussed. He invited himself up to my cockroach-infested, mold-in-the-coffee-cup studio apartment, despite my objections. I could dress myself presentably but my apartment revealed the depths of my poverty. Within seconds he’d wrestled me to the broken-back cot with the dirty sheets and peeled off my jeans and underpants and stuck his cock into my hole. He later told several mutual friends he’d never seen such abject squalor before. The next morning my rectum hurt, but I thought nothing more of it.

Another Englishman, a Cambridge don who was an authority on Arabic literature and who was visiting my university for a term, invited me to his apartment, got me drunk on martinis, and soon had my rump in the air, my legs bent back; after feasting on my hole he plunged into it and left me bleeding and unsatisfied on his bed. He put on his robe, washed away the blood and feces, went into the sitting room, made a cup of tea for himself, and took up a book. I pulled myself together and slunk away. For years afterward I bragged that I knew him.

There was a close friend of mine in London with an unheated apartment near Bond Street, in which I stayed in the sixties countless times. In 1970, when I lived in Rome, John came to visit me for a few weeks. He was what I called in those days “a character.” He hated the royal family with a passion. He seemed terribly repressed and proper, but when a lover told him, while they were driving through Scotland, that he was leaving him, John said in a clipped voice, “Very well,” turned the wheel, and drove them off a cliff. They both spent the next year in full-body casts. John had his nose broken and remade several times but he was never quite satisfied with it. Every morning he’d make tea and listen to the “wireless” chat shows, including the Woman’s Hour. He knew every bus route in London and even their late-night schedules. He was good at living on nothing a year; he made orange juice from powder in water. He ate something called cheesed cauliflower. He said ate as “et.”

Everything in London was foreign, starting with the fat, stubby key pushed into a low lock on the outer door—the “Chubb key.” We would take the tube to Hampstead Heath, past the house where he said Rudolf Nureyev lived with his lover, Peter O’Toole (or was it Terence Stamp? Probably neither). We ran about among the trees and bushes on the Heath, like the “mad things” we were. I wished my host, who was short and snug in his jeans and black leather jacket, wouldn’t speak in such a deep, camp voice (he was a trained actor) or refer to me as “Miss Thing.” We were just sliding out of the era of heavy-drinking Tallulah impersonators into the pot-smoking Village People period of the weight-lifting, hypermasculine clone. I lifted weights, and John told me that was unhealthy and that later it would all turn to lard, which was true. The first time I saw a mustache in a gay bar I said to my cruising buddy, “Eeeww … I’d never kiss a man with a mustache, would you?” Six weeks later we both had them.

I would do anything, look any way, that would get me laid. I couldn’t believe guys years later would advertise themselves by the boot brand or high-tops they wore. In France I remember men saying they were style santiags (cowboy boots) or crade (unwashed). Wasn’t the body or even the personality under the look more important than the accessories? I would wear anything from a red hankie back-left pocket (aggressive penetrator) to yellow back-right (piss swallower), if I thought someone, anyone, would like that. I suppose I believed one’s essence was enduring and unshod and of a neutral color and that accessories, so important to the poor and young, were immaterial.

I must have felt or been felt by hundreds of men on the Heath; I particularly liked deep soul kissing with a mustachioed stranger as the wind blew through our hair and the leaves above us shivered and the swift-moving clouds obscured the moon and stars. “Are you there, Miss Thing? Ready to go?” that bass, highly inflected voice would ask out of the darkness.

Daring myself, I asked the tall, slender, impossibly young man in my arms (he smelled of good soap) if he’d like to come home with us; our “flat” was on Marylebone High Street (which I’d learned to call “Marl-bun”). He said yes and my host, John, who resented snooty boys from Oxford and thought aristocrats should be beheaded, seemed a bit grim as we walked (downhill) all the way from Hampstead to Bond Street. Every hundred paces the Oxonian and I would stop a second to “snog,” much to John’s irritation, and the snooty trick never drew a breath, and kept talking about the beauties of “Keys,” which I finally understood was his college, Caius, at Oxford. At last we were in bed and he was “good value” as a sexual partner—lithe, loving, versatile. In the morning I asked him if he wanted a “scone,” which I pronounced as it was written.

He said, “I can’t bear to think I shared a bed with someone who speaks like that.”

“How should it be said?”

“ Skun.”

***

A young, slender redhead, taller than I was, came up to me at a trendy East Village café, the KGB, which was on the second floor, up a long, perilous staircase, and said in a deep voice, “Mr. White, I’d like to interview you about intergenerational sex. Would that be possible?”

“You bet,” I said, feeling like a starving dog at the door to a meat locker. It was 1985 and I was forty-five.

He was someone I would have been attracted to even in my first youth, when I was cute and picky. Well, to be honest, not so picky, since I scored with someone every night.

We made a date at my place for dinner, one I prepared with loving care. My Paris trainer used to say if you give anyone enough wine and pass the poppers, you can get him. I guess I’m too romantic for thinking about seduction techniques. I try never to impose myself on someone who doesn’t fancy older men (or let’s just say “the old”). I taught for decades but never slept with a student (one ex-student on graduation day). I let the other person make the first move.

He was a fascinating dinner companion. He had an unusual self-assurance and smiled knowingly as if he already understood what you were saying. It was the early days of the internet and he told one story after another—stories he’d researched for Plugged In or some such trendy magazine. The story that struck me most was of an American who met an Englishwoman online. Through constant rambling and intimate conversations, they found they were perfectly suited to each other, fell in love, and decided to marry. He flew to London—and discovered she was sixty and he thirty. The age difference, which they’d never established during their hundreds of hours online, seemed insignificant next to all their shared values and expectations. They married and lived together happily back in his native Akron, Ohio, to the astonishment of their friends and relatives, and both worked in the diner he owned. My date, Denver (not his real name), presented the internet as something spiritual, linking souls on the deepest level; of course we all know the cesspool of lying, vitriol, and unscrupulous subterfuge it eventually became, but in those pioneer years it promised to be a new, exciting utopia.

As if this scarcely believable story had been a preview of his own obliviousness of the barriers posed by age, he began to kiss me immediately after dinner. I’m lucky enough to have a functioning fireplace in Manhattan. I lit the logs I’d previously laid and soon we were naked on the floor beside the blaze. The thick red hair on his head and the sleeves of glinting red gold on his arms and the shield of pliant red on his chest and stomach, not to mention his burning bush, seemed too good to be true. We had memorable sex but afterward he complained I was somehow too experienced, too slutty, too quick and adept in assuming the position. He didn’t like how I’d expertly swiveled my ass up to his waiting cock. What he wanted was a timid, gray, recently divorced elderly man who would reluctantly give way to his ardor—someone wooden and naive, astonished by his own acquiescence, endowed with the purity of the until-recently-heterosexual, the clumsy paterfamilias who’d shamefully nursed forbidden fantasies of a fiery young redhead, someone who would finally surrender to the redhead’s passion but mutter later that that battering had really hurt, darn it. I felt I was being punished for not being a nerd.

I lost touch with him but discovered he was teaching in upstate New York and had become a sought-after screenwriter. From a movie magazine I learned where he was teaching. He’d also found a gray, tubby lover of a certain age. Denver brought the lover to a pizza party at my place. All the handsome, wasp-waisted, bumblebee-torso “boys,” forty years old and well launched in their careers as writers, filmmakers, and designers, clever and expensively coiffed and shod, though the clothes in between head and feet were “young,” generic, and off-the-rack—they were all buzzing around Denver with his red hair, low, resonant voice, growing fame, unimpeachable masculinity. They could scarcely believe they weren’t his type and that the balding guy alone in the corner was his chosen lover.

I found out that Denver’s father was a chauffeur for a car service and had ferried Joyce Carol Oates and me to New York more than once. There we were, brightly chattering and oblivious in the back seat while Denver’s father under his black hat with its badge and shiny bill drove us into the gathering February dusk. Little did we know this ideal young man had sprung from these quite ordinary loins.

***

There was the guy I met online who said he was a Scottish top. I asked him if he could wear a kilt while I bottomed for him. He lived in a worker’s cottage in Brooklyn, only one room on each floor. It was a square brick building with an Arts and Crafts wooden door—a multipaneled oak door with clear glass side lights. There was a fire in the fireplace, which had dusty blue tiles all around it.

The Scot was tall and slender and decked out in full regalia—a kilt, a short black jacket with silver buttons, high socks, a sort of pouch or purse on a chain around his waist, the sporran. I knew that under the plaid kilt there was a dick and hairy balls, no underpants. He was younger than forty and had a wide mouth full of white teeth, blue eyes as blue and large as a songbird’s eggs if they’d been made of crystal, a sharp nose, and an accent that was almost intelligible, though less and less so as I became more and more stoned on the joints he was feeding me. He seemed surprised and slightly vexed that I hadn’t brought any weed, as if I were just another freeloader bottom who expected to be kept high and well fucked. Which I was. Or so it seemed. He didn’t say much. I was worried that I’d made a faux pas. He ordered me to take off my clothes and kneel. I obeyed.

I could see his erection ticking up and dimpling his kilt. I always became hypnotized by cock when I was stoned; my nipples ached in anticipation of their being worked. I was so insecure about my body that my very shame felt erotic—vulnerable, despicable if despising was on the program, worthy of being punished, eager to be punished. His mouth, now that it was closed in an unsmiling line, was exactly as long and straight as each eyebrow, a Morse code of male beauty or maybe like the oblong pitches in a medieval hymnal.

He snapped his fingers and pointed to the tips of his black slippers, not bedroom slippers but the kind you traditionally wear with a kilt. I crawled over there, as big and awkward as Mr. Snuffleupagus on Sesame Street, a Muppet so large and unwieldy that it takes two people to operate him. The Scot, Robert was his name, sat on a high stool next to the fireplace and folded back the panels of his kilt to reveal his big erection, as Christ tears open his chest to display his red, red Sacred Heart. I began to slide my pot-dry mouth up and down on the veined shaft. He kept up a muttered narrative in his incomprehensible accent; he might as well have been speaking Plattdeutsch. Before long he had me in the room upstairs, his bedroom with its gigantic bed covered with a taut rubber sheet.

His older lover showed up and began to order me around in an accent I couldn’t place. He tried to fist me and I said I wasn’t quite ready for that. The idea excited me, but I’d never tried it. He said, “If I split you open, so what? Why do we all have this expensive health insurance if we never use it?” His accent sounded Slavic, which made it all the more sinister. I never did figure out his nationality. I thought his remark about health insurance sounded disagreeably fatalistic and bleak.

We had many rematches, the three of us. Once, I was ordered to bring a young fourth for the Slavic lover (he wasn’t really into old men). The guy I brought along was a handsome Mormon hustler/actor/poet/waiter; Robert and his lover suspected he was hired flesh and seemed to be against that in principle. I kept assuring them he was a friend, which he was, though in truth I did pay him—but they were dubious. The Slav sucked him and Robert fucked him, though normally he liked to dominate the elderly and the overweight. I couldn’t believe he didn’t prefer this healthy, happy, brawny blond with the beautiful skin and glittering smile, his slim waist and big chest, his low voice and the movements of an athlete, graceful but not intentionally graceful.

Another evening Robert wore tight-fitting leathers and he and the Slav shaved my body. On yet another evening we all went to a restaurant in the neighborhood and Robert waited in the men’s room for me to come in there and get fucked in a public place, but I was too stoned to understand what I was supposed to do. On another cold evening, he greeted me at the door to his house in a jockstrap and began to flog me. I bellowed my pain but both he and the Slav shushed me; they were afraid a neighbor passing by might hear my cries. They didn’t want theirs to be known as the House of Pain. Then we all moved to the bathroom upstairs. The Slav and I crouched in the tub, whereas Robert stood up on the sink and aimed his piss at one of us or the other. We both competed for it like seals begging for fish. I make it sound comical but it was as serious as a christening.

Then Robert broke up with the Slav, who’d become a serious drunk and fell down the stairs repeatedly. They sold their little house and the Slav moved back to Poland. Soon he was dead, I heard, from drink; maybe the breakup (or his retirement from his fascinating job) had destroyed him—or maybe he died just from the habitual progress of alcoholism (my AA friends and family members have taught me not to search for psychological reasons for alcoholism but to recognize it not as a symptom but as the disease itself).

Robert became a loving nonsexual friend, though I relished stories about his own exploits. He and his new lover went to a fisting colony in Normandy (it no longer exists), and there Robert pushed an entire football up a Frenchman’s rear; the man had to visit a local surgeon. Curiously, a whole queue of ass-hungry men were lined up before Robert’s door at the colony the next day. They, too, wanted to be worthy of a serious operation. In Berlin when Robert ran into the man who’d needed surgery, that guy was ready for a rematch—greedy glutes!

Robert is always courtly now—to the point of actually reading my countless books! In his huge penthouse apartment that looks out in all four directions at Manhattan, he has parties peopled with handsome young professionals and even a few women. Cute caterers are circulating with champagne and caviar. He couldn’t be kinder or more respectful. He praises my prose to his nonreading rich gay friends. I remember the first opera I saw as a child in New York. It was The Magic Flute at the Old Met. The hero had to pass through the frighteningly believable trials of fire and water to enter his father’s temple; that seemed like what I’d gone through to bask in Robert’s esteem (though secretly I was nostalgic for the trials).

***

Women? you ask. In the horrid old days we used to call them fag hags. The women who frequented gay men liked that they were around. The men tended to be good-looking, fun, muscular, always laughing, and good dancers. They went out almost every night, unlike their straight counterparts, who played only on weekends. Gay men could be flirtatious and (if you got them drunk and they were young) would even fuck you. Older ones or sober ones seemed more committed to their “lifestyle.” Gay guys would sleep with you and snuggle, pretend to be your boyfriend on an evening out with the boss or the visiting relatives from Amarillo. Gay guys would hold the door open for you and not expect you to split the bill. Occasionally you might meet an actual straight man with them when their little brother or college roommate was visiting. Or the straight black stud who was gay-friendly might end the evening with one of their girls. If you put on a few pounds or wore a dress twice, gay men would scarcely notice. All they required was that you be “fun.” Lonely beautiful women who were staying true to a fiancé in another city were attractive eye candy. In the old days before AIDS and before gays were so identifiable, a beautiful gal pal might lure a drunk heterosexual man into a three-way, especially desirable in the distant past when gays were attracted only to straights (“Why would I go to bed with another pansy? And do what? Rub pussies?”).

In those bad old days (the fifties), gay men were allergic to women, but in the seventies, after Stonewall, gay men started hanging out with women, just as after the feminist revolution women began to socialize with one another. I can remember in the forties when my mother thought it was an admission of defeat (or perversion) to be seen in public alone with another woman. Now gay men search out their female counterparts; an Australian friend is hosting a woman from Berlin, who, he says, “is a real slut—just like me!” My husband has a rich young lady friend who is a lesbian but currently with a man. My late best friend Marilyn used to say she preferred sex with men but that she could fall in love only with a woman.

Adapted from The Loves of My Life: A Sex Memoir, to be published by Bloomsbury in January.

Edmund White is the author of many novels, including A Boy’s Own Story, The Beautiful Room Is Empty, The Farewell Symphony, A Saint from Texas, and The Humble Lover. His nonfiction books include City Boy, Inside a Pearl, The Unpunished Vice, and The Flâneur. He has received the PEN/Saul Bellow Award for Achievement in American Fiction and the Medal for Distinguished Contribution to American Letters from the National Book Foundation.

December 13, 2024

The Best Books of 2024, According to Friends of the Review: Part One

Issunshi Hanasato, The Timeless Treasures of Literature (ca. 1844–1848), via Wikimedia Commons. Public domain,

One more year has passed: the humanoid robots are coming, my taxi has no driver (not even a metaphor), and ChatGPT tells me “there is hope even in the most hopeless times.” In our unreal reality, I’m inspired by a genre of compassionate absurdism: Roberto Bolaño, Jorge Luis Borges, Italo Calvino, Leonora Carrington, Toni Morrison, Thomas Pynchon. Another such writer is Enrique Vila-Matas, whose brilliant essay-fiction Insistence as a Fine Art (translated by Kit Schluter) came out this summer. Beginning in somewhat ekphrastic mode with Julio Romero de Torres’s painting La Buenaventura, Vila-Matas embarks on a playful defense of “insistence”: how authors echo themselves and others in their works; how these spiraling repetitions create an imaginary world more truthful than the adamantine pseudofacts of general reality. The publisher—Hanuman Editions—is also an expert practitioner of “insistence”: reimagining the legacy of Hanuman Books, a cult series of chapbooks produced between 1986 and 1993.

—Joanna Kavenna, author of “ The Beautiful Salmon ”

Joseph Andras’s writing favors the political: his novella Tomorrow They Won’t Dare to Murder Us, published in translation by Simon Leser in 2021, is narrated by a pied-noir during the Algerian Revolution, and in Faraway the Southern Sky, released in English this spring, the author traverses Paris to retrace the steps of Ho Chi Minh’s life there. Andras hunts down the houses where Ho Chi Minh allegedly resided and the offices where he worked, constructing a map of the relationship between France’s capital and Ho Chi Minh’s burgeoning radicalism. Descriptions of Paris’s underbelly intermingle with Andras’s account of a twenty-something-year-old who, dreaming of liberating his country, would one day dictate the assassination of his political enemies. The novel is a story of how ideologies transform but also, largely, of hope: “If the rebel intoxicates, the revolutionary impedes. … If the first is accountable only to himself, the other embraces humanity as a whole.”

—Zoe Davis, intern

Saskia Vogel’s translation of Linnea Axelsson’s Ædnan: A Novel in Verse does what you want a translation to do: take you inside a world and an experience that you couldn’t otherwise access, and make you ache for it. This epic follows three generations of Sami people in Norway as they try to preserve their way of life in the face of shifting borders and encroaching modernity. This spare and beautiful book will haunt you.

—Megan McDowell, translator of Samanta Schweblin’s “ An Eye in the Throat ”

Susie Boyt’s Loved and Missed is one of those books whose premise—the long-suffering narrator Ruth, in lieu of her absentee addict daughter Eleanor, raises Eleanor’s daughter—sounds so plainly tear-jerking that you go in with your guard all the way up and your heartstrings secured. But the book is written with such understatement and so little pity that it slips past all your tactical gear and shanks you in the lungs, spleen, and femoral arteries before double-tapping you, in the final chapter, with a POV shift that’s borderline unethical. Ruth is pissed off, elegiac, heroic, ironic, forbearing, and glum, but never saintly, and Boyt’s careful modulations of tone keep you off-balance: “I propped a tall red candle in an eggcup and lit the wick, sheltering it with the curve of my hand, the flame hot on my fingers until the fucking wind blew it out.” Your guard may go up again when you learn—to extend the parenting theme—that the author is Lucian Freud’s daughter and Sigmund’s great-granddaughter. Is it nepotistic? I think it’s nepotastic.