The Paris Review's Blog, page 19

November 8, 2024

On Augusto Monterroso’s The Gold Seekers

From Ayé Aton’s portfolio Afrika in the new Fall issue of The Paris Review.

Augusto Monterroso’s The Gold Seekers is a fun mix of personal archaeology and literary autobiography in an erudite yet concise package. I love a short book full of rabbit holes for me to follow long after I’m finished, I love reading in translation, and I love prose that doesn’t conform to any particular genre. The Gold Seekers fits the bill. On the surface, it’s a memoir of the Guatemalan writer’s bohemian childhood through the twenties into the thirties. But the narrative of Monterroso’s early life occasionally strays into his later years or departs entirely from his material existence to ruminate on literature, film, Central American history, obscure Italian poets, and much more. The memoir, with its detours and vignettes, reads like a book of experimental essays, the unifying subject matter being Monterroso’s excavation of the people and events that helped him form an early idea of himself, an idea inherently tied to taste—how he relates to his world through his developing sensibilities and ethics. The sections on Central American history contextualize Monterroso’s later self-theorization as an “ignored” writer whose political exile in Mexico from his adopted Guatemala rendered him a “citizen of nowhere,” seemingly unnoticed by the wider literary establishment despite the fact that he became a favorite of writers like Calvino for his imaginative yet succinct short stories. Monterroso’s memoir is also characteristically slim; the turns of his capacious mind are rendered from Spanish into lyrical English by the translator Jessica Sequeira, and the whole book, including a foreword by Enrique Vila-Matas and a translator’s note by Sequeira, totals under a hundred and fifty pages.

A descendant of Guatemalan and Honduran aristocrats, Monterroso was born in Tegucigalpa, the capital of Honduras, into a family that prioritized art even as their material circumstances and political clout declined over the years, requiring them to move around quite a bit. “My childhood became a mirror-like double in that environment of fantasy, imagination, and unreality in which my parents had surrounded themselves,” he writes early in the book. We are introduced to music teachers (whom he and his brothers do their best to annoy), traveling performers (with whom he sometimes falls in love), august relations (whose manners he occasionally corrects), and films shown in the cinema his father manages. There is plenty of material from his youth for Monterroso to sift through. Questions of curation, of curating one’s very sense of self, prevail throughout the text. One of my favorite chapters begins with the lovely sentence “It’s possible to choose your most remote ancestors” and goes on to describe Monterroso’s admiration for the forgotten late-Renaissance poet Janus Vitalis, who, through a circuitous correspondence with a retired Spanish librarian, Monterroso discovers may actually be a distant relative. The text is full of such apparent diversions, but collectively they constellate the work’s core—an exploration of how one chooses the self one becomes, even in the face of what one cannot choose (one’s place in time, geography, circumstance). Ultimately, our choices about to whom and what we give our energy, our intellect, and our love are the best shot we have of identifying who we are.

Matt Broaddus is the author of Temporal Anomalies and Deeper the Tropics. His poems “The Answer is Beef” and “Topos” appear in the new Fall issue of The Paris Review, no. 249.

On Mohammed Zenia Siddiq Yusef Ibrahim’s BLK WTTGNSN

Otis Houston Jr., Untitled Cellphone Photograph (2022), from issue no. 240 of The Paris Review.

I love density. Compression is nuclear. Big family, small house—no room (Jeezy). Used to act up when I went to school—thought it was cool, but I really was hurt (Meek Mill). Free Gaza, we on the corner like Israelites (Earl Sweatshirt). It’s opaque / and then it is violent (Ibrahim, “Wittgenstein Tried to Warn Us About Lions”). Poetry is a drama of gaps and leaps but also of gather and charge. One can’t be too precious about it.

BLK WTTGNSN, Mohammed Zenia Siddiq Yusef Ibrahim’s forthcoming collection from Tiger Bark Press, is density itself, a kind of reconstructed surrealist epic of black critique that overwhelms with its range and slices with its imagination. Ibrahim’s work has refreshingly little to do with the platitudinous, overly carved (to use my friend S.’s phrase) contemporary poem that sometimes goes viral when bad things happen and people want to confirm their confusion or mystify their position. This book is bold, serious, and so funny, even when it flows like blood and smoke.

The collection, described in its first part as an “investigation,” moves through the Austrian analytic philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein’s claim that the “sense of the world must lie outside the world” and confirms something of its jagged fractiousness only to leap past it in invention. From a para-Socratic dialogue in which the disesteemed rapper and popular podcast host Joe Budden is compared to General George Patton to an encounter between the fictional meth lord Walter White and Wittgenstein, these poems are driven by an immersion in damaged life and the martial, mass-industrial emanations of its pop cultures.

But Ibrahim’s critical operation leverages collision over incision. In the book’s restless, referential form, I feel the pulse of the internet, but also the geopolitical sprawl of violence within which the poems are always multiply located. That’s how we end up with lines that seem tossed up from a weird weed dream (“My nigga, you’re in a mental hospital because of Ludwig Wittgenstein?”), passages of strange, ornate beauty (“science teachers from the / ’50s who blow their brains out in a rust / sky desert just to spite the automatic / cathedrals of an atomic moon”), and an anecdote about a pair of Lithuanian concentration camp inmates whose mutual hatred precedes and exceeds their incarceration.

“The ridiculous and / messy; the slow drip into / The other,” Ibrahim writes. And he’s right. That’s how we’re living these days—we should read about it so we can think about it.

Benjamin Krusling is a writer and an artist. They are the author of the collection Glaring and the chapbook It got so dark. Their poem “pray for paris” appears in the new Fall issue of The Paris Review, no. 249.

November 5, 2024

Philadelphia Farm Diary

Elana the goose. Photograph by Joseph Earl Thomas.

September 1, 2024

Elana thinks the world is coming to an end, but I remind her how this is a fundamental problem of perspective. She is both right and wrong, and so am I. Elana, insofar as I can tell, contains the multitudes most other three-year-old Sebastopol geese and humans above the age of thirty lack.

When I open the coop, this Amish-made shed, painted blue with little herb planters beneath the windows, she tawdles out, screaming, as geese often do. Her adopted babies (three gray “African” geese) and a duck trio waddle out after her; they test their lungs against the air, honking and such over the sounds of slow traffic on Penrose Avenue, the warblers waiting to share their food, four dogs barking on the other side of the yard, those big black vultures competing for pool water, and my neighbor’s white cat, everybody’s nemesis, lurking at the edges of our fence and licking its lips at the thought of baby birds. The nearly last living rooster is sexually tepid, but eager for food, guiding all thirteen hens to the snacks I’ve dispensed, clucking them over to what he’s “found.” Elana grooms my pants leg, then unties my retro number 8s as if desperate to return to summer, to the sandals that ferried my bright green bare toenails out to her like so many flecks of potential vegetation. Failing, she looks up at me quizzically, or, like, Where the fuck is my food, nigga?

The backyard is pure dirt. That hanging obstacle course I installed over six hours for the kids at the height of the pandemic hangs limp between two lantern fly-ridden trees. Beyond this, the original shed. Field mice scatter at the sound of my approach, and I let down Zagreus the cat (spawn of Hades), plump and insouciant, who stares at them, bored. She follows me inside, dodging nails on the weathered little ramp, and meows as I toss handfuls of bugs and worms on the ground from an orange Home Depot bucket; they’re light and crunchy in my hands. A groundhog scurries off into my neighbor’s yard. This is .23 acres of Elkins Park, Pennsylvania, a pseudo-suburb made up mostly of white assimilated Jews; but now, as we negroes approach a thirty percent population density my black neighbors and I cackle at the dog-whistled concerns about “where the neighborhood is going.”

The sound of Elana’s chirping as she gulps from the hose is simply pleasant. Her minions splash in the kiddie pool. Sometimes I sit down for a minute and wish the fowl would devour me.

September 5

Today, two ducks fuck just outside my bedroom window, a soon-to-be-dead silky rooster and four geese circling them and crowing/hissing/clucking/honking as cloacas kiss at the center, with some eloquence, considering the shitty green water over which they buss down, beautiful, like the sound of palmate feet patting down mud. When I open the window, they all scurry off like teenagers caught skipping early classes to learn how their bodies work.

The geese sprint back to the window, greedy-ass Betty the hen tagging along in the hopes she might snatch up some greenery from the hand that feeds. Once, I gave in to my son Eli’s begging, and let him take the birds some watermelon on his own; I watched from the very same window as Betty leapt into his arms, scrambling the watermelon and sending him fleeing into the house yelling, “Daddy! Daddy! Betty attacked me!”

She reminds me of those aggro chickens in The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time, but she looks a bit more like an imperial chocobo rocking a dark harness around her neck, greedy-ass Betty, waddling up to anybody’s open hand who might have flashed greens or watermelon, parsley or carrots, peas or broccoli. She was indignant all summer, pecking at cat-eye nail polish, confused as to why the clack of her little beak wasn’t followed by anything like pleasure. Worse things happen every day. When she was a chick with twenty-four of her chirping homies in the brooder at the foot of my bed, Betty was the first to hop on out like a grown-up and get half-swallowed by the puppy, Rize, who, before her first real taste of chicken flesh thought it all was just a game. Eli doesn’t remember those years ago when he was four and his pursuer was just a tiny curious marshmallow with a beak. Now, he runs in circles around the fire pit clutching mealworms in one hand and asparagus scraps in the other, yelling “Betty chill! Chill Betty! Oh my God!”

These days Eli and his twin brother prefer gathering eggs and dishing them out to neighbors and friends, fetching black pepper or Adobo from down the street when I run out in the middle of making dinner. In this form of equivalent exchange, they come to feel useful.

The backyard is pure dirt. Photograph by Joseph Earl Thomas.

September 7

I suppose I thought I was building something. A place where, rather than sucking up mold in Frankford, my family, or those who chose to—wherever choice is a valid category—might thrive on a time-out from power, the proliferation of drug addiction, and the failures of social reform or divine violence. I didn’t then imagine myself becoming like my grandfather at first, welcoming in all who need and then growing exhausted, mean, or resentful in the aftermath, having failed to help anyone else or myself, having failed to build anything tolerable or work hard enough to one day not have to work so hard anymore. When he died early of complications from HIV/AIDS and everything else, he’d still never stepped foot in my place; flattened to the floor of his room when we found him, he’d held steadfast to the prospect of his own home, surprising as it was through bone-shattering labor that he might ever own such a thing. Today I watch said home burn completely through on Instagram and in the group chat; a fire started by the guy squatting there took the life of one cat and incinerated the dingy couch where my mother once slept, under which I’d found, at my angriest, some young boul’s discarded gun. I’m fifteen minutes away now and feeling much closer than I ever chose to be.

What had happened was, after ten years of tryna buy a house with the VA home loan and being thwarted by racism and cash offers, I stumbled across a rancher in Elkins Park with six barred Plymouth Rock chickens in the backyard. I asked my realtor if we could add them to the deal, and, despite the weirdness of the request, he relented, the sellers consented, and there we were, a flock.

We made upgrades: fencing, a bigger coop, Kaina’s tulips in the vegetable garden, more asparagus and collard greens, watermelon and kale, flowers in the wooden boxes along the fence.

And not two years later whiteflies will have decimated the collards and the asparagus will be growing wildly all over; I’d even find a tall stock in the front yard next to a pumpkin my children planted under mulch; green onions will have bolted, flower boxes grown dilapidated, and Elana will have lost a lover and a chunk of her left wing to a family of neighborhood foxes whose faces, when I catch them one day peering through the fence seem to scream to me, “Just to get by,” like Talib Kweli. Friends and family will have cried over dead chickens both named and nameless, and Freya the hundred-pound Ridgeback who likes to sleep with my other son Max will have hunted one of our own, bringing her back to me battered and bloody and hardly holding on, whereupon for the first, but most assuredly not the last time, I will be forced to finish the job.

September 12

Today I’m in too much pain to do most anything and have trouble walking to the bathroom. Sciatica or some shit, the busted hip from that time I got hit by a car in Guatemala, a lack of rest from the recurring nightmares about money. I’ve been growing less mobile too fast, less capable of overdoing physical tasks. I have no qualms asking for help, just a shortage of helpers. My mother wants to fill in, as black mothers often do for black boys, helping. But she has never done this before, and my obligation to raise her in my home is also raising my blood pressure too high to sustain a life past fifty. Things are filthy in the yard, but the birds are alive, my mother is alive, and we have a place to be.

September 16

The children tend not to see the birds fucking, which feels like a pedagogical loss. Filming them feels too pornographic. Kaina hated springtime’s sexual flurry when we were together, watching the first rooster, her namesake, grip the back of a hen’s head and pin her into submission. Some hens go half-bald, their feathers snatched up from fighting, over the rooster or over food, or being fucked too frequently by said rooster.

Kaina always broke up the activity whenever she could. If we humans fucked at the edge of my bed, a bird or two might approach the window next to my bare ass and Kaina would shoo them away. “Get the fuck outta here, Elana,” she’d say, laying on her stomach, my hand still taut on the back of her neck.

Today, rain makes many pools of mud out back, and while the chickens take shelter under our biggest tree, the ducks and geese party through the storm; they hop around in short gallops and take flight over the pool, quack, and toss their bills into the mud, shucking up old oyster shells and worms, tearing whole weeds up by their roots or otherwise yelling at a car or two passing by under the bleating patter of raindrops.

September 19

Elana laughs when I read her Tony Tulathimutte’s Rejection in the morning. I wonder out loud if she feels rejected by me when I’m traveling for work, the way my daughter does whether she says so or not. We’d gotten used to COVID, when I was earning the Ph.D. and teaching eight classes online, the era where my children could find me at home, fortunately or not, all through the morning, the evening, and the night, always knowing I was just out of arm’s reach. Elana jumps up on the firepit where I sit, and just when I think she’s come to cuddle, that she might sense some melancholy the way Ken the bernedoodle does, she tries to eat my earrings, pull hairs from my beard.

A vulture, interloper. Photograph by Joseph Earl Thomas.

September 21

Today I find a yellow-bellied flycatcher chick in the front yard, having fallen from our main tree, closest to the road. The flock first regarded these little brown jawns (LBJs) as a menace, invaders crossing the fence to sop up free layer-feeder pellets, but the chickens have gotten so bored of them they just let it happen now. Rize carries the chick around in her mouth like a football, dodging the other dogs and slobbering this way and that. It’s a little wet, this bird, and terrified, while Rize prances around. There’s no blood, but the parents circle me, chirping to high hell about their child. And I know I’m supposed to leave the babe alone, let it find its way some way. Most likely this fledgling was attempting to fly for the very first time; letting it die feels ridiculous. I place the chick at the top of a playground I’d built for the kids a while back, worried that it would get eaten alive by beaks and bills the size of its whole body were it just on the other side of the fence.

September 22

In the morning I find the warbler on the ground again, hopping about in the mulch over dog toys and feces, children’s toys and water bottles, cardboard boxes and toilet paper rolls that the twins had used to make their robot costumes. Fuck it, I think, and take the little guy out back where I laid down the feeder pellets and mealworms while all the other LBJs scatter and make way, Elana and them approaching the weakened baby with amused pity. Fuck is this? she chirps, turning her head sideways like that meme of a Pitbull’s confuzzlement. But instead of being brutal like I thought she would, Elana nudges the baby with her bill and then just walks away. She spots Bob, the strawberry-stealing chipmunk strolling out of the shed, and chases him down with her wings spread before coming back to yell at me like, You finna do something about this shit?

September 23

I’m groggy this morning, having slept little if at all, but I force myself up. The guilt of not beating the sun makes me anxious. I know for a fact that if I’m unable to read or write a lick before these wild-ass kids emerge, then the whole day is already over. Outside the little warbler is gone. Not a trace of him anywhere, and I fill the kiddie pool, where the ducks play like any other time, and dish out some worms and veggies and weeds out back before opening the coop. I could hear the crowing, quacking, honking for freedom from across the yard, but strangely, when I open the side door they don’t just start rushing out. Even when I call them, mainly Elana and Betty, no one moves. So I prepare myself for death. This is what happens. Often, when a bird dies, the rest of the flock turns timid for a bit. A month ago, Arthur, our soft boy rooster who followed my daughter around and didn’t care about food, who’d hop onto your lap or shoulder if you stood still, eventually tried to play with a stray cat. When I found him he was hardly put together, but I tried to patch him up and hope for the best. That next morning I found his body.

Today, I have no choice but to open the main coop doors, which are sometimes stuck because of pine bedding piled up against one, heavier if Elana’s been spilling all the drinking and bathing water on the ground because some chicken looked at her the wrong way. There’s no smell. But as soon as I turn the handle, dozens of warblers scatter out. Others knock into windows desperate to escape; some are slow on the uptake, just munching on feeder pellets or drinking water like nothing; a few are trapped in nesting boxes next to the main egg-layers—four Golden Comets the kids all named Jared after their mom’s new partner—and the Jareds are seriously perturbed, making that noise they make whenever you move a too broody hen. There are so many warblers flying out over my head, fleeing into perches and through spider webs, bouncing off the walls with a wooden knock each time. Frantic. Elana walks right between my legs and out the door like there’s nothing to see; there is nary a dead bird, eaten by the worms and weird fishes, just a strange confluence of winged desperation.

But no sign of the little guy either, who days before fell into the yard and Rize’s mouth. By the time I get all the warblers out of the coop, Eli is outside barefoot again, as he often is whenever he senses I’ve left the house.

“Daddy,” he says. “Are you okay?”

And I tend to take a deep breath before turning around. “Yes, Eli. I’m okay. Everything is okay,” I say.

Joseph Earl Thomas is a writer and gamer who lives in Philadelphia. He is the author of the memoir Sink and the novel God Bless You, Otis Spunkmeyer.

November 1, 2024

A Pretty Girl, a Novel with Voices, and Ring-Tailed Lemurs

Each month, we comb through dozens of soon-to-be-published books, for ideas and good writing for the Review’s site. Often, we’re struck by particular paragraphs or sentences from the galleys that stack up on our desks and spill over onto our shelves. We often share them with each other on Slack, and we thought, for a change, that we might share them with you. Here are some of the curious, striking, strange, and wonderful bits we found, in books that are coming out this month.

—Sophie Haigney, web editor, and Olivia Kan-Sperling, assistant editor

From Kathryn Davis’s Versailles (Graywolf):

I was a pretty girl; I glittered like the morning star. My red lips would open and it was anyone’s guess what would come out. A burst of song. Something by Gluck, a pretty girl in pain maybe, impaled on the horn of the moon. The Kings of France, starting with Charlemagne. A joke.

From N. H. Pritchard’s The Mundus (Primary Information), a work originally begun in the sixties and described by its author as “a novel with voices,” “an allegorical romance, a poem in prose form,” and an “exploded haiku.” Paul Stephens, in his afterword, recommends that it is best “viewed, read out loud, meditated upon—possibly chanted or even absorbed as a collective trance.”

From Izumi Suzuki’s Set My Heart On Fire (Verso), first published in Japan in 1996 and translated by Helen O’Haran:

“Very womanly thing to say. Women are such realists.” Sabu had a different opinion to the comic-book artist.

From Katherine Rundell’s Vanishing Treasures (Doubleday):

Lemurs are strange in the way that the reclusive and wealthy are strange; having had the island of Madagascar to themselves evolve in, they have idiosyncratic habits. Male ring-tailed lemurs have scent glands on their wrists, and engage in “stink-fighting,” battles in which they stand two feet apart and wipe their hands on their tails, then shake the tail at their opponent, all the while maintaining an aggressive stare until one or the other retreats. It feels no madder than current forms of diplomacy. It’s not unusual for female ring-tailed lemurs to slap males across the face when they become aggressive.

From Jane DeLynn’s In Thrall (Semiotext(e)):

“I hope you don’t hate me for saying this, but it’s true … someday, way off in the future, when you’ve moved far away from home, perhaps into a city you’ve never been to (or maybe even heard of), a city perhaps where no Jews live—for sometimes I see you in a strange country and at other times in a small town in California, a small town with white walls and no history—you may miss [your parents], you may miss [their voices], and when you call home to hear it (out of your terrible loneliness), you’ll be in New York City (though you’re ten thousand miles away), and you’ll turn into a child again, even if you’re an old woman like myself. Yes, it’s a terrible irony, but you’ll miss that voice, you’ll tell yourself you’d do anything in the world to hear it again, even for a moment—you’ll wish for it perhaps more than you’ve wished for anything you’ve ever wished for in your life—but even if you flew halfway around the world to hear it, even if you could unpack your bags and settle back on the Upper West Side, you could never hear it again, not really, for it belongs to your past, and you’re moving, however much you want to avoid it, into your future, a future you can’t even delay very much, for it’s there, leaping at you, and you want that too! You want it and you don’t want it—this is how you always seem to feel about things—I mean deep inside—you want them and you don’t want them—except this one time, perhaps the only time in your life, when you’ll want something utterly—with your whole being, and it will be this voice, the voice of your past, the voice of yourself. But you won’t be able to retrieve it, nobody can retrieve it, for it’s lost in the past where your childhood is, your real childhood—not the one you feel like you’ve been living all your life (for, of course, you’ll feel like a child all your life: who doesn’t?) and not the miserable childhood you tell yourself you lived (what adult doesn’t make a myth of his unhappy childhood to redeem the utter misery that is adulthood?)—but the real childhood, the one that happened and the one that you, of course, can never remember: for it’s stuck in the pores of your skin, it’s lost in the marrow of your bones, it swirls around in your blood until it reaches every cell in your body, it flies into the air with every breath you take—you can’t know it because it’s you, there’s nothing else to know, and it will be this way forever! And out there, amidst your bright-white buildings and strange flowering plants in the town that has no past, you won’t be able to remember any of this, for the ‘you’ that was will have gone new places and dreamed new dreams (after a point there’s no room for old ones)—and then, my dear, and only then, will you know what it means to really cry.”

Suzanne and Louise

Originally published in 1980, Suzanne and Louise tells the story of two sisters—one widowed, the other never married, recluses in a hôtel particulier in Paris’s fifteenth arrondissement. The author, who is also their great-nephew, is one of the few who visits them.

Suzanne takes a certain pride in having risen from the poor, uncultured working class to her position as the wife of a well-to-do shopkeeper, in having completed her studies and become a musician, after having traveled far and wide, reading Proust and listening to the “great works” of music. Louise respects this accession (her exclusion). “I quit after elementary school,” she says. Before entering Carmel, and then working at the pharmacy for her brother-in-law, Louise worked in Rheims for an insurance company. Louise loves frothy things: sparkling wines, sentimental magazines (on her bedside table, Nous Deux is next to Catholic Life), operetta music.

Ten years separate Louise and Suzanne. They were not raised together. And yet they share the memory of a poverty-stricken childhood spent in the country, with a railroad switchman father and a mother from a penniless bourgeois family.

Louise does everything: the cooking, the laundry, the cleaning, the shopping. It’s she who dresses and bathes the partially disabled Suzanne. The water she throws on Suzanne’s body is always too hot, the food she serves her overcooked and cold. The pair of scissors she uses to clip Suzanne’s toenails often cut into her skin.

Not necessarily in “narrative order,” some minor events that end up disturbing their daily routine: a bell ringing, a bad dream, the dog dying. Suzanne refuses to take her daily walk for no reason. Louise overhears her talking to herself. Suzanne pays Louise, very little. Louise is her only heir. Louise puts her salary in the collection box during Mass. She squanders her money on wine and wishful thinking. No one will ever know why Louise entered Carmel, forty years ago, and why she left, eight years later.

The play.

One Sunday, behind Louise’s back, Suzanne says to me, “That play that you wrote about us, I’d really like to read it, after all.” She asks me to bring her a copy the following Sunday, and to hide it underneath my blazer when Louise comes to let me in, since she thinks Louise won’t appreciate it. When I hand her the stack of stapled photocopies, she immediately hides it, without even looking at it, in a drawer of her bureau, saying, “If I die in the meantime …” Suzanne never calls me, out of a concern for saving money, perhaps, or for fear of bothering me; I’m always the one who calls. But that Monday evening, as soon as Louise has left for Mass, Suzanne telephones me, and in a trembling but determined voice, says:

“My heart is racing. I already tried calling you last night, but you weren’t home. So, listen, you might not be happy about this, but you’re going to have to change some things. First of all, our names aren’t Louise and Suzanne, our names are Hortense and Patricia. We don’t live in a mansion in the fifteenth arrondissement, we live in an apartment in a modern building, next to the Jardin des Plantes. We didn’t used to be pharmacists, we ran an old hardware store. Also, change the dog’s name, Whysky is too specific, someone might recognize him. Call him something like Sardanapalus. You say that I took a hundred francs from the drawer every day—you must be crazy! We’ll have the taxman after us. And then, that thing about the safe hidden behind a painting, you can’t keep that in, someone will come here and torture us until we tell him where it is, regardless of what’s inside … Take out that bath scene, too, it will hurt Louise’s feelings … You know, when I say all these things, it’s not for me, I don’t care, it’s for your sake, you know, you’re just asking for a defamation suit …”

Suzanne’s legs.

Today, for the first time, Suzanne allowed me to photograph her legs, at the foot of the sofa that’s fitted with a slipcover, she took off her slippers, she lifted her nightgown above her knees and said “Call the photo Legs of a Cripple,” and I said, “No, it will be called Suzanne’s Legs.” “Well, so much for my modesty,” she said. Next time, I’ll photograph Louise’s naked legs and feet, next to that huge bone with red teeth marks that Whysky chews.

Photography.

I think things other than lenses make “good photos,” ethereal things, of the order of love, or of the soul, forces that pass through and inscribe themselves, fatally, as the text that gets written in spite of ourselves, dictated by a higher voice …

From Suzanne and Louise , translated by Christine Pichini, to be published by Magic Hour Press in November.

Hervé Guibert (1955–1991) was the author of twenty-five books and published extensive texts and criticism on photography, primarily with the French newspaper Le Monde. His bestselling novel To the Friend Who Did Not Save My Life was inspired by his close friend Michel Foucault and the two men’s experiences living with AIDS, which tragically ended Guibert’s life at the age of thirty-six.

Christine Pichini is an artist and translator based in Philadelphia.

October 31, 2024

Bite

Photograph by Emet North.

We travel to Lake Clark, Alaska, in a four-seater prop plane—my partner and I, the pilot, and the housekeeper for the residency where we’ll be staying. When asked which seat he wants, the housekeeper says, “I’ll take the leg room, I’m a big bitch.” I think, Queer? I ask about his work and over the racket of the plane he shouts that he performed for a decade as a drag queen at a famous Los Angeles bar. He quit during COVID. “People are gross,” he says. Though later he will tell me it was performance itself he tired of, finding it antithetical to intimacy.

My partner, R., and I have come to the residency with the intention of inhabiting new metaphors for intimacy. In our application, we wrote, “In 1991, Lynn Margulis coined the term holobiont to describe miniature ecologies consisting of a host organism and their microbiome. The human is a holobiont—more than half of the cells in our body have nonhuman DNA.” We wrote, “In this project, we will ask how this theory of the holobiont can create possibilities for queer joy.” We’ve considered, for example, replacing the phrase “I’m full” with “My gut bacteria have multiplied by a billion and are satiated.” We know we will sound ridiculous. As we fly, I try to inhabit this new mode of thinking. I put a hand on the back of the seat in front of me and think, Look at those microbial skin communities. But the thought glances off; it won’t stick.

When we arrive, the manager of the residency gives me a choice of daily chores—laundry or knocking down spiderwebs from the eaves. I choose the spiders.

Niche is the word I have in mind the next day as my hands swing a broom at a rack of antlers. The housekeeper walks past, playing Mariah Carey on a personal speaker. “The reason you have that job,” he says, “is that I refuse to do it. I refuse to destroy another being’s home. You are going to come away with a fine sense of guilt.” The last resident who spidered experienced an existential crisis. The spiders are tenacious. They rebuild.

As is typical of species living on islands or mountaintops, each member of the lodge has an expansive niche. There are eleven of us—five residents, six staff. The plumber is also the first responder. The chef also carves the decorated wooden spoons used to ladle water onto the rocks in the sauna. The Sierra Club masculinity I expected is largely absent, replaced by possible queerness. The wilderness guide (also the guest-services coordinator) has multiple partners and talks openly about sex work. The landscaper tells us that all the Los Angeles queers are currently listening to country music. When the handyman-cum-helmsman-cum-woodworker takes off his boots to cool his feet in the lake after a long hike, his toenails are painted a vibrant blue.

At dinner that night, the housekeeper asks R. and me how he can tell us apart. We laugh. At the residency, we move as a unit—from writing desk to paddleboard, from paddleboard to hammock, where we read the same books. We arrive together at dinner. We shower together. I worry this could be unhealthy. I was once called toxic, and ever since I’ve maintained a certain vigilance. When I read articles about healthy relationships, they emphasize maintaining your sense of self, enforcing clear boundaries. R. shrugs at these maxims, says, “It’s ableist to think a healthy relationship can only look like one thing.” The self, hard boundaries—these are precisely the things we’re hoping to trouble. “It has become increasingly clear that individuality is a myth,” we wrote in our application, referencing Scott Gilbert, who deconstructs six categories of individuality and argues that every body is an ecosystem, a multispecies assemblage. In this sense, our Alaskan we is a victory.

The insects are the first to distinguish between us. After dinner, walking along the lakeshore, I wonder out loud if I’m being gendered by the mosquitoes. Studies steeped in binary sex insist that mosquitoes are more drawn to men than to women, because of their larger size and higher metabolic rate, unless the woman is pregnant, in which case they are most drawn to her. R. and I are neither men nor women and neither of us is pregnant, but when we walk through the same patch of forest, I emerge with a dozen swelling bites, and they emerge with none.

Two weeks later, three welts appear in a line on my left hand. I don’t know what bit me, don’t feel the bites themselves, but my fingers become uncomfortable, then stiff, then fully immobile. Theories as to who did it abound among the lodge’s residents. An overwhelm of mosquito bites. White sox flies. An extreme reaction to devil’s club. A spider. This last hypothesis appeals to me, because it suggests some karmic justice. It is week three of the residency, and my hands have knocked down some two hundred webs. I’ve come to know the spiders—the red-and-black-bodied one who weaves above the solar panels; the long-armed brown one, whose tattered web once caught and held an adult wasp; the fat gray one spinning high on the eaves, who waves their front legs at the broom as it comes.

The pain swaddles each finger. Not pure like the pain of an ant bite, that thrilling one-note zing, but something discordant and serrated. I had thought I was stoic, but this, like so many of my ideas of myself, proves untrue within partnership. At night, I thrash until I wake R. “It hurts,” I say. I tremble. I refuse to walk the four hundred yards to the shared kitchen for ice. I scratch, and the pain doubles down, cutting deeper. I yelp. I am dramatic, entranced by this aspect of partnership, new to me, the useful performance of physical pain.

For relief, I submerge the bites in the lake water, which the salmon scientists have measured at thirty-eight degrees. The opposite of pain is pain—a searing, water-chapped cold.

Does the creature that bit me experience a similar discomfort? Arthropods have nociception, so they know when they are injured, but as one entomology article asks, Is it pain if it doesn’t hurt? To an insect, tissue damage might register as a neutral sensation like the press of a railing against a rib—present, but neither good nor bad. There is no biological reason why recognizing tissue damage must be painful, no biological imperative for suffering.

The physicist Randy Baadhio insists that pain is a quantum thing, a harmonic oscillation which travels from cell to ready cell via resonance—like a seismic wave or an earthquake. On the third night, the worst night, I think I feel pain like that—the shaking in my hand a seven on the Richter scale, causing stone to crack, structures to collapse. When the bite punctured dermal cells, the hand’s ecosystem was overrun with thousands of neutrophils, which left their cradle of bone marrow for a riverine system of blood vessels. Now, in the fingers, the neutrophils morph like salmon do in the residency’s bay—changing color, growing a long jaw. This physical change is brought on by a chemical gradient— for the neutrophils it is due to an excess of cytokines, for the salmon to a lack of salt. In both, the transformation is a sign of maturation, of readiness to fuck and fight. Neutrophils fight by tossing highly reactive oxygen molecules toward a harmful microbe, which is destroyed in an explosion upon impact. The interstices of our hand are dotted with fireworks that no one can see. I say “our hand” because the appendage—swollen, immobile—seems to belong as much to the microbes as to me.

This is what I remember wanting to tell R. that night—I had done it, had inhabited, for a few hours, our innermost ecologies. I’d felt the microbes move through the channels of our hand. I called R. to where I stood, to tell them about this, mosquitoes biting my exposed legs and face, hand in the cold water.

R., who came bleary-eyed and panicked to the door, remembers it differently—the redness of my hand, my body contorted. R. has a different word for the enraptured preoccupation of those days—misery.

The next night, R. says, “You have to let me sleep, okay?” I agree. My nights are patterned—ice pack, cold water, moments of calm and moments of frustration. I’ve kept R. awake. “Is this toxic?” I ask. They say, “It’s toxic to ask over and over whether something is toxic.”

Some painful venoms have low toxicity. In these, the pain is a false signal, a lie. In other venoms, toxins are injected alongside pain-producing compounds. Metalloproteinase, which causes dermal cells to wither. Potassium, which depolarizes cell membranes. In these cases, when toxins are present, the pain is denoted “true.” I can’t write down, here, whether the pain in our hand is true or false. The neutrophils know, as they migrate toward the bites; their measurements are both sophisticated and inhuman, though their DNA is human DNA. They know precisely how the ecology of our hand has changed. Within the hand lies evidence of a split world—the pain is only true or false, not both. But I don’t know which. Practically, it hardly matters. It’s been several days. My hand is swollen, but I’m otherwise fine. If the venom was toxic, the toxin is localized—not systemic, not deadly. Not something, I argue to R., that merits a trip to the clinic.

Karen Barad, in her essay “Nature’s Queer Performativity,” writes that toxicity, like queerness, like gender, is an ecological identity—temporary, fluid, performative. I perform genderqueerness, and whether that gender is true or false, my person is changed. Our hand performs pain, and whether the pain is true or false, the venom toxic or nontoxic, our hand is changed.

This is the argument R. uses to insist that we should make the trip to the clinic.

Everyone can tell, by this point, who is who. I am the irritable, wounded one, the one skipping dish duties to submerge our hand in the lake. I am the one talking at dinner about a wasp that stings predators with a contorted penis.

R. is the one tying my shoes and cutting the sleeve of my rain jacket wider. R. is the one explaining my symptoms to the resident first responder. “Regardless of toxicity,” the first responder says, “the pain of swelling is true. Pressure on your nerves,” he says. “The nerves can withstand it, but only temporarily.” I return to him when the pain subsides, thinking this is a sign of healing, but he says, “A silent neuron is a dead neuron.” Then there is the rupturing of capillaries, small puddles rising to discolor the skin of our fingers. R. is the one asking about nearby clinics. R. is the one who, when I talk about the bite as intimacy, says, “You barely leave the cabin.” This is true. Our hand pulses a warning when I try to hike. Our hand can’t hold a paddle. Our hand sears in the hot water needed to wash dishes. I’ve been taken off the chore list. I’ve dropped out of the lodge’s ecology. “Intimacy,” R. says, “with who?”

Aged neutrophils return to the bone marrow, where they were born. The word for this is the same word used for salmon returning to their birth sites: the neutrophils are homing. In the bone marrow, if the body is uninjured, unstressed, the aged neutrophils are ingested by local macrophages, and their biomaterial is used to create new neutrophils. When infection or injury is present, senescent neutrophils may not be ingested but instead reenter the bloodstream, migrating back to the site of infection. I like this image of longevity, of the aged cells continuing.

When I say this to R. in the morning, they reply, “It looks worse.” The swelling has moved past the wrist into the arm, the whole limb red and spongy. “You need steroids,” R. says. But I am curious. I want to let it play out. I say I trust the microbes. “This is an allergic reaction,” R. says. “By definition, it’s not something you can trust.”

Maybe I don’t want to go to the clinic because the microbes don’t. From what I’ve read, you cannot overstate the effect of microbes upon your decisions. Suddenly craving blueberries? That’s your microbes after a little fiber. Woozy with love? Microbes flooding your brain with oxytocin. Like the smell of someone of the same gender? You’re not queer—your microbes are, attracted to the pheromones her microbes create after ingesting her odorless sweat. An article in Frontiers in Nutrition—“Romantic Relationship Dissolution, Microbiota, and Fibers”—even hypothesizes that the sadness felt after romantic relationship dissolution “might be related to decreased microbiota diversity … which could be corrected with the ingestion of dietary fibers with an additional antidepressant benefit.”

If I go to the clinic, if I accept steroids, our hand will shrink. I will lose my sense of the ecological, the new lens offered by pain. “Isn’t this what we wanted,” I say to R., “what we were trying to achieve? Inhabiting a new metaphor?” “You can’t sleep,” R. says. “You can’t work. I’m leaving in two days, who’s going to tie your shoes? If this is what it looks like to understand your body ecologically, that metaphor is dysfunctional.” “In this world, maybe,” I say. “In a world defined by individuality, maybe.” R. says, “You’re miserable, I’m miserable.”

The clinic is in the same building as the post office—across the lake, at the end of the runway, a ten-minute walk from the boat ramp, past a burger stand run by Billy Graham’s son and two hangars for the National Park Service. The nurse prescribes steroids and tells me to come back if symptoms don’t improve in forty-eight hours. If our hand requires a trip to the hospital in Anchorage it will cost four hundred dollars to get there, which I don’t have. She tells me to be careful. “If you’re bitten again by the same thing,” she says, “you could be in trouble.” She is talking about allergy, airways, anaphylaxis. But the relationship she describes between immune system and venom reminds me of infatuation. “Keep an eye on it,” the nurse says as I leave, as though she understands how alien our hand has become.

The day after we visit the clinic, R. leaves for a conference. My pain goes with them—or, at least, I lose my motivation to act it out. Our hand throbs, but there is no reason to whimper, to thrash in an empty bed. On the steroids, the topography of our hand shifts—our bones are once again visible, small buttes on the side of the hill of our wrist. I can straighten our fingers. Our hand still aches, still holds heat. The wrinkles are deeper and differently ridged—excess skin folding back on itself, just as valleys changed by flooding remain changed long after the waters have receded.

On the summer solstice, the residents of the lodge light a bonfire. They make time-lapse videos. They dance, easy with one another, secure in their niches. Their ecologies spiral around me, never quite touching me. I dance without pain, again experiencing myself as a singular being. I toss back tumblers of tea made from raspberry leaves without considering my gut bacteria. This continues until a sound artist approaches to ask if I miss R. “When does she get back?” he asks. I correct the pronoun out of habit—“They get back in a few days.” He bends toward me, lowers his voice, says, as though offering intimacy, that they-and-them pronouns are hard for him. “Isn’t it plural,” he says, “grammatically? Aren’t you a writer? Help me understand how it’s grammatical to use they and them for one person.”

Without thinking about it, I’ve lifted our hand. I’m rubbing the skin that surrounds the bites where new bacteria amass on the crusted welts.

I am quiet long enough that he apologizes. He didn’t mean to offend me. I drink a last tumbler of sun tea and retreat to my cabin. Even there, in the quiet, I can no longer feel the microbe communities pulsing. I call R. When they pick up, I’m crying. “What’s wrong?” they ask, and I tell them I’m alone.

R. returns three days later. They ask how my hand is before asking how I am. My hand is desolate. Healing is an accumulation of small deaths—bacterial cells combusted, dead cells sloughed. I’ve been considering the nurse’s words, that the microbes within the hand remember what bit it. I want to kindle that spark of recognition. I say, “I need your help.” They raise one eyebrow, an expression of skepticism.

The next day, we paddle to a secluded spot along the pebbled beach, and behind a tangle of driftwood I strip away my clothes. In a moment, I will lie my body down on the pebbles that shelter dozens of spiders. R. is the only one who will see me: we are far from the lodge, and the salmon scientists come only on Tuesdays. Nonetheless, this is a performance. I perform readiness, willingness. The spiders perform absence—they crouch in slivers of shadow, disappear into crevices. The pebbled beach, usually overrun with spiders, performs stillness. Performances help with courage. If a spider bites you during a performance, is the bite even real? Has it happened in real life, that place of lasting consequences? To insist upon performance, there is a camera. R. holds it. R., who has said, “I hate every part of this plan. I want it on record that I’m doing this because I love you. If a spider crawls on you, I’m going to lose my mind.”

The first itch is a conjuring. I lift my ankle. Nothing there. How long has it been? I ask. Forty seconds. Spiders live seven years on average. Forty seconds of my life equate to ninety minutes of theirs. How long until their fear gives way to curiosity? A tickle at the base of my neck, which I swat. I regret the swat. Nothing crunches beneath my fingers, so perhaps this itch was also a phantom. How long? Sixty seconds.

Later, returned to internet access, I’ll learn that the spiders of Alaska are not so venomous. None of their bites regularly cause major reactions in humans. R. is unsurprised. “Everything in Alaska that bit you bit me,” they say. When I apologize for my unwillingness to go to the clinic, for the way the bite came between us, they’ll say, “It didn’t. You were miserable, so we were both miserable. That’s intimacy.”

But on the beach: something moves in the corner of my eye, and my body jerks, wanting to flee. R. breathes in. A large wolf spider moves jerkily across the pebbled beach, attending to the motion of the air and to light. It tracks along the shadow of my wrist, nearly touching my skin. I wait for it to mount the boulder of my lower arm, and at that moment our hand pulses. Later I’ll learn this is a reaction to sunlight, to heat, but I believe then, with jubilation, that it’s a response to the spider, a microbial readiness.

I’d like to write it this way: the spider walked the length of my arm, the hydraulic tick of their legs making the nerves sing. Their eight eyes met four. R.’s eyes and mine watched them with breath held. But in truth, the spider, perhaps drawn by a vibration elsewhere or startled by my minor movements, scuttled beneath a rock, retreating into conspecific community, and after six minutes I, too, retreated. Went for my clothes, for R. No spiders crawled on me. But for an hour or so after, the flesh of my back held the imprint of the pebbles. The microbes on my back were temporarily more like the beach, more like the spiders.

Morgan Thomas’s first book, Manywhere, was published by MCD in 2022. Their work has appeared in The Atlantic, The Kenyon Review, American Short Fiction, and elsewhere. Their short story “Everything I Haven’t Done” appeared in issue no. 249 of the Review.

October 30, 2024

Sleep Diary

June 29, 2024

Bed at midnight. Awake at 3:12 A.M. Back to sleep around six, awake again at 8:39 A.M. Very hot out.

June 30

Bed at one thirty. Up at six thirty. Realized these are my final hours in my apartment before I move tomorrow. Not much sleep, but for good reason. When I already know that my sleep is going to be abbreviated, it’s easier to make peace with the specter of fatigue.

This apartment has a skylight, and my bed lies directly beneath. All the time, it gives the sensation of soaking in a sun shower. It is as if I am sometimes being cursed by God’s blessing. No air conditioning, so I freeze tomatoes in the icebox, as I call it to myself—I live alone—and then put them on my belly and heart to cool.

The past few weeks, when I’ve been up in the night and sensed morning coming, I’ve tried to locate the darkest corner of my studio apartment. This just means I’ve moved my top mattress layer, a cotton Japanese futon, to the floor. Restless, with one pillow and one sheet, I escaped the skylight. With my body this close to the floor, I can feel the rumblings of the building below me, the deep hum of the subway underneath, and the trucks outside, all the sound so bass-tone that I forget I’m even listening. Makes me think of the way that they say mushrooms speak to one another from underground, or of the sound of a whale.

July 1

Bed at midnight. Up at eight. Miraculous!

July 2

Bed at two. Up at four. Really wanted to make a snack, but I have no food here. Strange, to be hungry somewhere new. Back to sleep at five ten or so. Up at eight with a profound yearning for toast.

Four or five years ago, I often began to wake, full of beans as they say, sometime between two and four in the morning. It started in late winter, so I tiptoed around my house in wool socks. I was spooked by how energized I felt and by the quiet. Then the inevitable, anxious fantasy: Was I awake because something bad was supposed to happen to me? Gradually, I began to notice a rhythm. My body would activate, I would spend as many hours awake as needed, and then I would sleep hard till the day began. Waking up, I felt washed ashore.

July 3

I didn’t sleep well. In the garden of a bar on Washington, one of my dearest friends turned thirty. I love birthdays and the relief I feel when someone transcends this freakish decade. I didn’t drink much and came home early to walk the dog. There I go again: trying arduously to do things right.

I have the habit of, after a bout of indulgence and whimsy, gravitating toward self-imposed rules. There are some things that I know would make my life easier, and they sound tremendously boring and weirdly arduous: no blue light before bed. Have “wind-down time.” Take magnesium, bitch! Conventional wisdom advises against eating before bed, but I learned to release that expectation long ago. I am sorry for the confusion my digestive organs must experience, but a nighttime snack is one of life’s great joys.

The truth is that I am having a bout of summertime sadness. I am experiencing heartache that I imagine as a cyanotype: silhouetted, shadowed, beautifully blue, activated from staying out too long. On my first beach trip of the summer, last month, I burned the skin under my bikini top, at the bottom of the curve of my belly, and at the tops of my thighs. The burns have stayed, turning darker and looking like a comically unflattering contour. I bathe in vitamin E oil and imagine heat radiating from each spot holding the sun.

July 5

Tired myself out at work. Though I am a chef by trade, my job this summer is being a waitress. It is challenging but in a totally different way than I have ever known. I think it’s all the carrying of plates and performance. Restaurants give you something to wash off in the bath. Asleep, heartily, at one thirty. Up at nine. Proud of myself.

July 6

Should you purposely dehydrate yourself before bed so that you don’t have to get up in the night?

July 11

Bed very late. Awake at five, ravenous. I make my sunrise meal: important to eat something warm. Slice of bread, olive oil, in the pan. I don’t have a toaster. Handful of greens, squeeze of lemon. Let them get soft, then scramble one egg with feta cheese. No coffee yet—there’s a chance, after this meal, that you can get back to sleep. I do, and I awake feeling full.

July 13

Mercifully sleepy at ten thirty. Max the dog, who is my ward for a few days, sighs and splays at the foot of the bed. There is enough of a little breeze for a sweatshirt at bedtime. I imagine myself in Goodnight Moon.

Up to pee at two thirty. A thunderstorm begins, and I stand in my kitchen, sweatshirt hood on my head: a little monk, waiting for water to boil, staring out the window at the thumping rain. Back to sleep at three thirty. Challenging, searing dreams. I had a baby and it made me really happy, but no one celebrated her much. The birth had been a lot easier than I had anticipated it ever could be. Still, she and I both felt ignored—me more than ever, because she was so delightful. At seven, feeling different. I am half-nude and obvious; I took the sweatshirt off in my sleep.

July 17

Ate a pickle before bed at one. Woke at seven thinking inexplicably of the word Cascais.

July 19

Slept through the night. I was thinking this morning about how some people freak out when they can’t sleep. We fear that if we don’t sleep, we won’t be able to arrive as the person that we are supposed to be in daylight.

The irony is not lost on me: in attempting to decipher sleep, I am analyzing what is perhaps the most passive thing we can possibly do. Reminds me of that embarrassing law of nature that the more you try to control something—particularly yourself—the more defiant, unbridled, and intense the thing becomes. Kind of pitiful when the attempt to govern touches sleep, interrupting a mystery that takes care of itself—our brains going somewhere else, cells replenishing, eyelids flickering.

Happening all the time, terribly unknowable, and the closest, of course, that we get to death.

July 20

Big night out in Sunset Park. This morning, I chugged a coconut Electrolit. In a terrific mood, I bought flowers—daylilies, with blackberry branches mixed in. Profoundly beautiful and insanely expensive. I trotted my way home and luxuriated in the gift of a day off. Deep sleep throughout the afternoon as if I were jet-lagged or unwell.

July 21

What an indulgent feeling, for wakefulness to activate as the sun sets. Another garden, soft little lights, everyone blowing cigarette smoke out the corners of their mouths, away from one another’s eyes. Another birthday, another big night out. Two is quite enough, it turns out. Bed at three, up at ten. We stopped at the bodega on our way home, and I got a tremendous sandwich called the Iron Man. Halal chicken, sour peppers, white sauce, avocado. I ate half of it before rolling into bed.

July 23

Bed at 11:23 P.M. Up at 8:17 A.M. I never have trouble falling asleep, I realize. Just the staying.

July 24

Delightfully asleep at ten. I woke at midnight and ate a crumpet. I recently learned about something called revenge bedtime procrastination, where you engage in leisure activities in the night that you might not have been able to squeeze in during the day. Interesting. Watching tragicomic, brain-cleansing shows birthed from the Bravo universe. Organizing something useless in one’s apartment. The profound act of scrolling. Having a nightcap.

Being awake gives one ample time to consider habits and their relation to time. On a sundial, the gnomon is the upright part that casts the shadow. Gnomon, in ancient Greek, means “one who knows or examines.” At night, there is no sun with which to locate shadow; in a way, a person becomes the gnomon. What kind of incapacitated waiting is necessary to know something new? I’ve decided that it feels much more worthwhile to imagine that I have been awakened so that I can learn something I couldn’t quite squeeze into daytime. During the day, we can tell the time by the sundial’s shadow, and it dictates what we do and when we do it. At night, everything is shadow—ten could be four could be one could be three could be twelve. The only standing thing is us.

I’ve also wondered at the inverse: perhaps each hour means something specific. This is where the traditional Chinese organ clock comes in. Chinese medicine’s twenty-four-hour body clock is divided into twelve two-hour segments of the qi (life force) moving through the organ system. Each set of hours, then, corresponds to an organ—but also an emotion. The hours of 1 to 3 A.M. are when the liver most productively regenerates. The liver filters the blood but also regulates emotions like anger and resentment. The hours of 3 to 5 A.M. are the hours for the lungs. Not only do the lungs govern our respiration, but in traditional Chinese medicine, they also correspond to channels of grief and worry. I’ve developed a fondness for treating this clock as its own index of nighttime clues. Any flare in the dark as a potential explanation for awakeness resonates like a firework.

July 26

Upstate. A 10:25 P.M. bedtime. Melted into sleep, awakened at seven with color in my cheeks.

July 28

Back home. Bed at midnight. A random light turned on on its own at 5 A.M. I swear to God! I tried to change the bulb but remembered that I was tired. I slept fiercely until ten.

July 30

One can’t underestimate the presence of Love Island (both domestic and international) in my somatic life. I brought my watching to the postwork bath. Then to before bed, activating an unnerving and hyperactive part of my brain. Now the characters—once I have the strength to power them down—trot around, glistening and stressful, in my dreams. Especially the hot snake wrangler, Rob. But today I decided: no more Love Island before bed. If I really need to watch, I can wake up early. This idea is so pragmatic that it embarrasses me, which feels productive.

July 31

Bed at one. I drifted away, and then at two or so the light turned on by itself again. Maybe my apartment is haunted. Maybe I am being sent a sign. What type of omen is this? My brain chews the cud of various abstract interpretations for this spontaneous occurrence. Wondering up at the overhead, I am mystified. I fiddle around and realize that if I turn the light’s dial in the opposite direction, it releases a satisfying click. Perhaps the illumination was a mechanical error then. I suppose it was just the cross breeze.

Rosa Shipley lives in Brooklyn. She writes the Substack Palate Cleanse , on food, culture, and wellness.

October 29, 2024

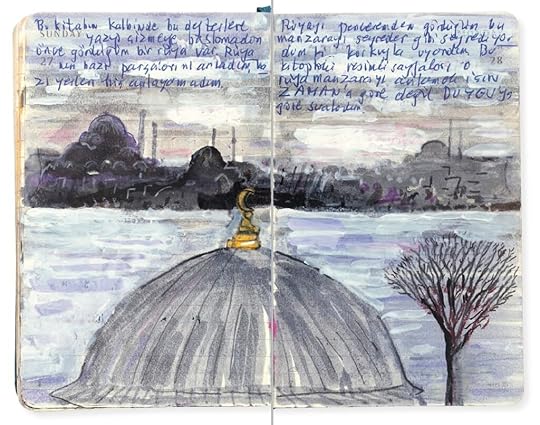

The City Is Covered in Snow: From the Notebooks of Orhan Pamuk

At the heart of this book there is a dream I’d had before I ever started writing and drawing in these notebooks. I have managed to make sense of some parts of the dream, but others I still don’t understand.

I was watching the dream unfold as if it were the view outside my window when I suddenly woke up, afraid … To help me understand that dreamscape, I have arranged the illustrated pages of this book not in CHRONOLOGICAL but in EMOTIONAL order.

Morning: the city is covered in snow. It’s sticking. Even on our balcony, it’s thirty or forty centimeters thick. Ash is sleeping in the other room. I am inside my novel. I have been reading a great deal about Ottoman telegraph offices. I’ve bought so many books lately! A snowy hush reigns over the house and the city. It’s still falling, so visibility is low. And I have to confess: I am so happy. About the house, about the snow, about Ash sleeping inside, etc. etc. I am hopeful that I won’t get into any more trouble, that I will be able to live in Istanbul, and that everything will be wonderful, just like this snow. My interview with La Repubblica has been published with the headline “Terrorism Must Not Become an Excuse to Undermine Democracy.” Marco sent it to me.

The snow and the cold are really striking. That greenish snowy blue … The color of the sea. The snow falling in tiny flakes. My protagonist, the Major, has now arrived at the Telegraph Office … Now I’m writing about the history of the telegraph service. It’s great fun. But slow going. Ash keeps going up and down between here and flat 16: in the SNOW, the city is quiet. Thanks to the snow, I have been able to step back, if only for a day, from the dreadful political situation we find ourselves in. In the evening a walk with Nuri on our tail –> out on the icy snowy streets … We had to wade through freezing puddles in the Taksim Square. Ash’s feet froze. The streets are cold, no tourists or anyone else around. It’s just us, the people of Istanbul. The metro isn’t too busy either. We got off at Etiler. Sevket, Yesim, Zeynep: who is looking for a job as she finishes her Ph.D. at Harvard … Sevket also talking about politics. None of us had anticipated this imperious, foam-at-the-mouth rhetoric, this terrifying Orwellian atmosphere of authoritarianism! We hadn’t expected it to happen so soon …

In the morning, snow again. Falling in huge flakes. As Ash sleeps and the day only just begins to break, I sit at my desk and write a detailed description of the telegraph coup. I am perfectly content. In fact I can just about admit to myself: the feeling of inwardness brought about by SNOWFALL, that feeling of being left to ourselves, is a kind of comfort. In ISTANBUL, we find comfort in the beauty of snow.

Orhan Pamuk is the author of twelve novels, the memoir Istanbul, three works of nonfiction, and two photography books, and the recipient of the 2006 Nobel Prize in Literature. Memories of Distant Mountains will be published by Knopf on November 24, 2024.

October 25, 2024

On Writing Advice and the People Who Give It

Drawing by Stephanie Brody Lederman, from Heroic Couplet (The Hustle), a portfolio that appeared in The Paris Review issue no. 75 (Spring 1979).

The Canadian writer Sam Shelstad’s third book, The Cobra and the Key, is a funny and charming satire of writing advice and the people who give it. The book is in the form of a writing manual, and its prologue begins:

Imagine you are standing in a gymnasium with numerous wooden chests spread out across the floor. Each chest contains one of two things: either a cobra, or a story. As much as you do not want to interact with the dangerous snakes, your curiosity is too great. It’s human nature to crave stories. We need them. So you gamble and open up one chest. It’s a story. You sit down and read, relieved to have avoided an encounter with one of the cobras and grateful that you get to enjoy a story. Once finished, however, you find yourself feeling anxious. The story was fine, but nothing special. You need to open another chest in the hopes of finding another, better story. In fact, you will not be satisfied until all non-snake chests have been opened and you have recovered every possible story. And so, inevitably, you open a cobra chest. You are bitten and the poison slowly kills you.

Straight-faced, grandiose, slightly lunatic—this man is our guide. A hundred and fifty-three short chapters follow, covering such topics as “Getting Started,” “Plot,” “Style,” “Point of View,” “Revision,” and so on.

I think what confuses me so much about those who have prescriptions for how to write is that they assume all humans experience the world the same way. For instance, that we all think “conflict” is the most interesting and gripping part of life, and so we should all make conflict the heart of our fiction. Or that when we think of other people, we all think of what they look like. Or that we all believe things happen due to identifiable causes. Shouldn’t a writer be trained to pay attention to what they notice about life, what they think life is, and come up with ways of highlighting those things? The indifference to the unique relationship between the writer and their story (or between the writer and the reason they are writing), which is necessarily a by-product of any generalized writing advice, is part of what makes the comedy in this book so great. As a teacher, “Sam Shelstad” is so literal, and takes the conventions of how to write successful fiction on such faith, that when he tries to relay these tips to his reader, the advice ends up sounding as absurd as it actually is.

“Events shouldn’t just happen,” one chapter begins, “they should be the result of your character’s decisions. An effective way to ensure this is to replace all of the ‘and thens’ in your story outline with ‘therefores.’ Let’s say, in your outline, you write, ‘Paul eats an ice cream cone and then he robs a bank.’ Now change this to ‘Paul eats an ice cream cone and therefore he robs a bank.’ The revised version is an example of successful cause-and-effect plotting, since now we know Paul robs the bank because he ate the ice cream cone. It’s not some random event that Paul robs the bank: his decision to rob the bank is a direct result of him eating an ice cream cone, and the scene where Paul robs the bank will now feel earned.” I have never wanted to follow writing advice more, to see what it creates.

Sam’s lessons are interrupted—sometimes intentionally, sometimes because he can’t help himself—with musings on his affair with Molly, an older woman from his mother’s writing group, and with accounts of his trials in getting his 1,200-page novel, The Emerald, published. (“It’s the perfect title … What is this emerald? … What happens to it? With two words—one, really—I’ve already grabbed your attention and filled your mind with interesting questions.”) Somehow everything is balanced so lightly, wittily, and warmly in this book: the absurdity of teaching writing, the vanity of the writer, and the very touching and human conviction that even if we have no idea what we’re talking about, that doesn’t mean we aren’t the best person to help.

Sheila Heti is the author of eleven books, including Pure Colour, Motherhood, How Should a Person Be?, and, most recently, Alphabetical Diaries. She is the former interviews editor of The Believer.

October 24, 2024

Remembering Gary Indiana (1950–2024)

Gary Indiana in front of his Los Angeles apartment building, 2021. Copyright Laura Owens.

We at the Review are mourning the loss of Gary Indiana. We are grateful for his work, and to have published an Art of Fiction interview with Tobi Haslett in issue no. 238. At a recent launch party, he gave a reading of several James Schuyler poems he loved, including this one. We hope to be adding remembrances in the coming days.

One thing I should put out there before giving my first last thoughts about Gary Indiana is that it doesn’t matter what I think. I learned this from him. My estimation of Gary comes so late in the game as to be worthless: he’d downed the same drinks and smoked the same cigarettes and had the same conversations about the same famous names with so many younger writers before me that it was a testament to the vastness of his appetite and perhaps also to the vastness of his loneliness that he still insisted through his eighth decade of life on doing what he did, which was—between making books and essays—hanging out deep into the night and pretending we had a culture. I’d often wake up the mornings after to find an email continuing our discussion—a multiparagraph missive sent from irmavep1@gmail.com—and I always meant to ask him if he’d ever been in touch with the person who’d created the original email address named after Irma Vep, that femme fatale and anagrammatical “vampire” played by Musidora. He loved Les vampires, and crime films and fiction of all kinds. This was our major subject—noirs, antinoirs, procedurals, detection—and now it’s his dead body locked alone in the top-floor room. Gary Indiana, the alias, the self-invention, was smart, mean, honest, and usually correct; the man behind the mask, I never met; again, I was too young and also, maybe, too straight, so instead of his bared heart, I got the writerly complaint. I think with all the art people and music people and fashion people and so on in his life, he just liked to sit down with another person who was baffled by the language. His true crime or true-enough crime trilogy is a masterpiece and deserves the Library of America today, agents and editors and rights issues be damned; publishers were always fucking Gary over. But despite a battered career, he knew who he was. One night at the Scratcher, we were joined by Ben Wizner, the ACLU lawyer representing a fresh-faced whistleblower named Edward Snowden. An inveterate hater of the U.S. intelligence community for, among other things, its invention of AIDS (Gary had a lot of theories), our own homegrown Elf King stood up at the table and declared, “I want you to tell Edward Snowden that the greatest living American novelist would like to suck his dick.” The message was delivered. A pity the mission was never accomplished.

—Joshua Cohen

I was supposed to take him to a party tonight. He was doing all right until last week. He’d been in and out of cancer treatment for a couple of years, but things seemed to be going well, however many jokes he would make about being on “the off-ramp of life.” He was planning to go to France to make a movie. I told him I would come with him whether he gave me a part or not. A couple of weeks ago he dug up an essay he’d written about Curzio Malaparte but never published, so I sold it to an editor I know, with a new magazine that’s paying pretty decent rates. The editor was happy to have it. Gary called me last Wednesday morning and said, “Christian, they sent me all this fucking paperwork, and I just can’t do it. I feel like shit. You have to do it for me.” It was my birthday. Our last conversation: a present. The last few days were all phone tag. I told him I would do it. I asked him to forward me the emails. He wrote back: “I certainly can’t do that.” I got the contracts from the editor, and he said, “We have one edit.” They wanted to change the phrase “transigent literary incubus” in the first sentence of the essay to “capricious literary incubus,” because they thought readers would have to look up transigent. I looked up both words and told them that Gary was using transigent in a very precise manner, to indicate the way Malaparte would accommodate whoever was in power at the time wherever he was at the time, Mussolini or Stalin or Mao. Gary liked to make us look up words. He was always right. He drew on all the resources of the English language with great exactitude, humaneness, and sympathy. So I said stet. They stetted it. They sent me the contracts and tax forms. I was planning to bring them over today to get his social security number and then take him to the party. Oh well. We’re going to miss him, to put it mildly.

—Christian Lorentzen

Joshua Cohen was awarded the Pulitzer Prize in Fiction for The Netanyahus: An Account of a Minor and Ultimately Even Negligible Episode in the History of a Very Famous Family.

Christian Lorentzen is a writer and editor. He has a newsletter on Substack.

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers