The Paris Review's Blog, page 20

October 25, 2024

On Writing Advice and the People Who Give It

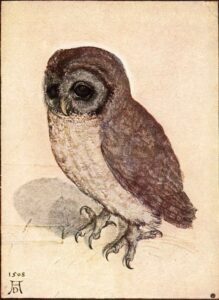

Drawing by Stephanie Brody Lederman, from Heroic Couplet (The Hustle), a portfolio that appeared in The Paris Review issue no. 75 (Spring 1979).

The Canadian writer Sam Shelstad’s third book, The Cobra and the Key, is a funny and charming satire of writing advice and the people who give it. The book is in the form of a writing manual, and its prologue begins:

Imagine you are standing in a gymnasium with numerous wooden chests spread out across the floor. Each chest contains one of two things: either a cobra, or a story. As much as you do not want to interact with the dangerous snakes, your curiosity is too great. It’s human nature to crave stories. We need them. So you gamble and open up one chest. It’s a story. You sit down and read, relieved to have avoided an encounter with one of the cobras and grateful that you get to enjoy a story. Once finished, however, you find yourself feeling anxious. The story was fine, but nothing special. You need to open another chest in the hopes of finding another, better story. In fact, you will not be satisfied until all non-snake chests have been opened and you have recovered every possible story. And so, inevitably, you open a cobra chest. You are bitten and the poison slowly kills you.

Straight-faced, grandiose, slightly lunatic—this man is our guide. A hundred and fifty-three short chapters follow, covering such topics as “Getting Started,” “Plot,” “Style,” “Point of View,” “Revision,” and so on.

I think what confuses me so much about those who have prescriptions for how to write is that they assume all humans experience the world the same way. For instance, that we all think “conflict” is the most interesting and gripping part of life, and so we should all make conflict the heart of our fiction. Or that when we think of other people, we all think of what they look like. Or that we all believe things happen due to identifiable causes. Shouldn’t a writer be trained to pay attention to what they notice about life, what they think life is, and come up with ways of highlighting those things? The indifference to the unique relationship between the writer and their story (or between the writer and the reason they are writing), which is necessarily a by-product of any generalized writing advice, is part of what makes the comedy in this book so great. As a teacher, “Sam Shelstad” is so literal, and takes the conventions of how to write successful fiction on such faith, that when he tries to relay these tips to his reader, the advice ends up sounding as absurd as it actually is.

“Events shouldn’t just happen,” one chapter begins, “they should be the result of your character’s decisions. An effective way to ensure this is to replace all of the ‘and thens’ in your story outline with ‘therefores.’ Let’s say, in your outline, you write, ‘Paul eats an ice cream cone and then he robs a bank.’ Now change this to ‘Paul eats an ice cream cone and therefore he robs a bank.’ The revised version is an example of successful cause-and-effect plotting, since now we know Paul robs the bank because he ate the ice cream cone. It’s not some random event that Paul robs the bank: his decision to rob the bank is a direct result of him eating an ice cream cone, and the scene where Paul robs the bank will now feel earned.” I have never wanted to follow writing advice more, to see what it creates.

Sam’s lessons are interrupted—sometimes intentionally, sometimes because he can’t help himself—with musings on his affair with Molly, an older woman from his mother’s writing group, and with accounts of his trials in getting his 1,200-page novel, The Emerald, published. (“It’s the perfect title … What is this emerald? … What happens to it? With two words—one, really—I’ve already grabbed your attention and filled your mind with interesting questions.”) Somehow everything is balanced so lightly, wittily, and warmly in this book: the absurdity of teaching writing, the vanity of the writer, and the very touching and human conviction that even if we have no idea what we’re talking about, that doesn’t mean we aren’t the best person to help.

Sheila Heti is the author of eleven books, including Pure Colour, Motherhood, How Should a Person Be?, and, most recently, Alphabetical Diaries. She is the former interviews editor of The Believer.

October 24, 2024

Remembering Gary Indiana (1950–2024)

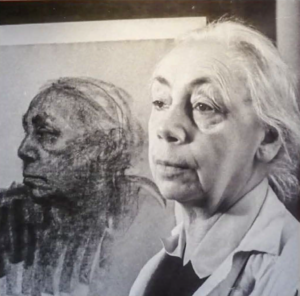

Gary Indiana in front of his Los Angeles apartment building, 2021. Copyright Laura Owens.

We at the Review are mourning the loss of Gary Indiana. We are grateful for his work, and to have published an Art of Fiction interview with Tobi Haslett in issue no. 238. At a recent launch party, he gave a reading of several James Schuyler poems he loved, including this one. We hope to be adding remembrances in the coming days.

One thing I should put out there before giving my first last thoughts about Gary Indiana is that it doesn’t matter what I think. I learned this from him. My estimation of Gary comes so late in the game as to be worthless: he’d downed the same drinks and smoked the same cigarettes and had the same conversations about the same famous names with so many younger writers before me that it was a testament to the vastness of his appetite and perhaps also to the vastness of his loneliness that he still insisted through his eighth decade of life on doing what he did, which was—between making books and essays—hanging out deep into the night and pretending we had a culture. I’d often wake up the mornings after to find an email continuing our discussion—a multiparagraph missive sent from irmavep1@gmail.com—and I always meant to ask him if he’d ever been in touch with the person who’d created the original email address named after Irma Vep, that femme fatale and anagrammatical “vampire” played by Musidora. He loved Les vampires, and crime films and fiction of all kinds. This was our major subject—noirs, antinoirs, procedurals, detection—and now it’s his dead body locked alone in the top-floor room. Gary Indiana, the alias, the self-invention, was smart, mean, honest, and usually correct; the man behind the mask, I never met; again, I was too young and also, maybe, too straight, so instead of his bared heart, I got the writerly complaint. I think with all the art people and music people and fashion people and so on in his life, he just liked to sit down with another person who was baffled by the language. His true crime or true-enough crime trilogy is a masterpiece and deserves the Library of America today, agents and editors and rights issues be damned; publishers were always fucking Gary over. But despite a battered career, he knew who he was. One night at the Scratcher, we were joined by Ben Wizner, the ACLU lawyer representing a fresh-faced whistleblower named Edward Snowden. An inveterate hater of the U.S. intelligence community for, among other things, its invention of AIDS (Gary had a lot of theories), our own homegrown Elf King stood up at the table and declared, “I want you to tell Edward Snowden that the greatest living American novelist would like to suck his dick.” The message was delivered. A pity the mission was never accomplished.

—Joshua Cohen

I was supposed to take him to a party tonight. He was doing all right until last week. He’d been in and out of cancer treatment for a couple of years, but things seemed to be going well, however many jokes he would make about being on “the off-ramp of life.” He was planning to go to France to make a movie. I told him I would come with him whether he gave me a part or not. A couple of weeks ago he dug up an essay he’d written about Curzio Malaparte but never published, so I sold it to an editor I know, with a new magazine that’s paying pretty decent rates. The editor was happy to have it. Gary called me last Wednesday morning and said, “Christian, they sent me all this fucking paperwork, and I just can’t do it. I feel like shit. You have to do it for me.” It was my birthday. Our last conversation: a present. The last few days were all phone tag. I told him I would do it. I asked him to forward me the emails. He wrote back: “I certainly can’t do that.” I got the contracts from the editor, and he said, “We have one edit.” They wanted to change the phrase “transigent literary incubus” in the first sentence of the essay to “capricious literary incubus,” because they thought readers would have to look up transigent. I looked up both words and told them that Gary was using transigent in a very precise manner, to indicate the way Malaparte would accommodate whoever was in power at the time wherever he was at the time, Mussolini or Stalin or Mao. Gary liked to make us look up words. He was always right. He drew on all the resources of the English language with great exactitude, humaneness, and sympathy. So I said stet. They stetted it. They sent me the contracts and tax forms. I was planning to bring them over today to get his social security number and then take him to the party. Oh well. We’re going to miss him, to put it mildly.

—Christian Lorentzen

Joshua Cohen was awarded the Pulitzer Prize in Fiction for The Netanyahus: An Account of a Minor and Ultimately Even Negligible Episode in the History of a Very Famous Family.

Christian Lorentzen is a writer and editor. He has a newsletter on Substack.

A Painter Is Being Beaten: Freud and Kantarovsky

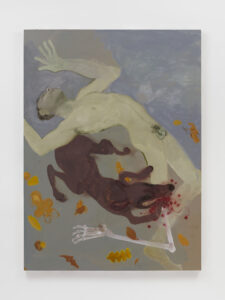

Saya Kantarovsky, Removal, 2018, oil and watercolor on linen, 55 ¼ x 40 ¼ in. Copyright the artist, courtesy the artist. Photograph by Adam Reich.

“A Child Is Being Beaten” is the strange title of Freud’s 1919 paper on sexual fantasy. This sentence, one of sadomasochistic, masturbatory enjoyment and announced from an unspecified source, indicates the phantasmatic scene admitted to by several of his patients. What are these beating fantasies? Freud says it is “not clearly sexual, not in itself sadistic, but yet the stuff from which both will later come.”

He’s trying to reach back to some primordial core of our subjectivity, centered on sexuality, the first outlines of guilt, and the desire for punishment. Also: the place where the prohibition against incest barely holds up in its commandment. The paper feels utterly wild—so many surprising elements are condensed into the phantasmatic image of an adult beating a child (usually a paternal representative, though sometimes the mother is present). Importantly, Freud notes, these aren’t the musings of perverse patients but rather the revelation of common daydreams—perhaps even unconscious universal scripts, that graft childhood experience with cultural mores.

Emulsion, 2017, oil, watercolor, and pastel on canvas, 85 x 65 ⅛ in. Copyright the artist, courtesy the artist. Photograph by Robert Glowacki.

The fantasy is first a way of admitting sexual enjoyment, in tandem with the punishment and guilt one may feel for having it. There are also the outlines of a traumatic memory, according to Freud, of seeing other children punished, and wondering about this particular scene: What is loved and hated by these adults, what is good and what is bad—what, in essence, makes for authority? A potential identification with power is offered by the fantasy, the desire to be the one who beats, set against the one who is beaten. This impulse does the work of hiding a feeling of subjection, of utter helplessness; what we feel when our desire for another is so strong that we risk being harmed by them.

In the fantasy, we are everywhere and nowhere in the plot lines—the beater, the beaten, the voyeur. Such a diffusion of roles allows us to shirk responsibility for our manifold desires—pretend they aren’t our own, or that the other person simply wanted what we gave to them. Facing the pleasure or aggression of others dead-on is disconcerting, so the fantasy provides distance. It charts the multiplicity of places we occupy at any given moment, while we try to stay in our body, retain our feelings of excitement. Or don’t. Or, better, can’t. This was one of Freud’s earliest insights; as he states in The Interpretation of Dreams:

The fact that the dreamer’s own ego [ich] appears several times, or in several forms, in a dream is at bottom no more remarkable than that the ego [ich] should be contained in a conscious thought several times or in different places or connections—e.g. in the sentence “when I [ich] think what a healthy child I [ich] was.”

Freud reminds us that, to children, sex sounds like rhythmic beating, heavy breathing, scary moaning. Pregnancy and birth are likewise terrifyingly incomprehensible. Beating is not only the action of masturbation—beating off, and excitement’s periodicity as well—it is also a stand-in for the experience of insufficiency in the face of the reality of sex. Or in the face of all reality: the open face of wonderment in a child, versus the closed, supposedly knowing faces of adults.

Annus Horribilis, 2020, oil and watercolor on linen, 102 ⅜ x 78 ¾ ins. Copyright the artist, courtesy the artist. Photograph by Pierre Le Hors.

“Beating” comes from Freud’s use of schlagen in German, which is an odd choice, because in addition to describing a violent blow, it also suggests the beats of music—more than other English words like hit, or strike. Freud seems to be telling us about how reality imprints itself on us, how it enters our senses—and also, how we absorb culture. It happens in beats, in blows, in morsels, fragments—never all at once, and rarely a complete process. He is drawing our attention to the linguistic, figurative, sensorial aspects of a life present in tonality, mood, aesthetic qualities—items that are meant to be felt and thus go beyond cognitive understanding. So beating is also about the way a body absorbs. In the realm of culture, this receiving has been tied to the father figure—one that is, and has always been, violent.

Breath, 2020. Oil and watercolor on linen. 74 ¾ x 55 ⅛ in. Copyright the artist, courtesy the artist. Photograph by Pierre Le Hors.

In typical Freudian fashion, we are getting closer to incest. How? Because incestuous wishes to merge with our parents, as well as visions of primal scenes, remind us of our separation from one another and the sheer fact of generational difference, even as we try to breach the boundary. A parent’s infanticidal wishes extend from a universal hatred for procreation (children are a reminder that we will die, as they will likely outlive us) and yet we procreate. This is why Freud constantly returns to the story of Oedipus Rex. It is a story of not only the love and hatred bound up in any given family, but also one of contradictory wishes rooted in the dawn of human life— a history that each of us still struggles with, and cannot escape.

In the beating fantasy, this imagined “sex,” as worthy of punishment, returns us to the sex that led to our own creation. It is a veritable existential breakdown. The fantasy is also then a scene of sheer narcissism, while paradoxically also a scene that explodes you—going where one was not and could not be, to a time before one was born—to this wrenching scene of one’s own conception.

According to psychoanalysis, we should be prohibited from getting too close to this place. Like the dream’s navel that touches an even greater unknown, Freud says, we locate the point where wishes rise like mushrooms from their mycelium. Don’t reach back too far! Hover around this point, but don’t believe you can crack the lock box. The narcissistic image—”I am the desired one, the chosen one being beaten”—must be struck down. It is not that we are beaten, or escape being beaten, we are everyone: victim, aggressor, onlooker, and worse, we are also beating ourselves.

Fighting with his disciples (who wanted to discover the beginnings of the unconscious), Freud argued that this movement backward was a move toward self-dissolution. It was an imagined return to the womb, a wish to find the origin of a world full of goodness (that doesn’t exist), like some kind of safe space where we are each the precious one, desired, sanctioned to live. All these imaginary topoi, before the caesura that drags us into the world, kicking and screaming.

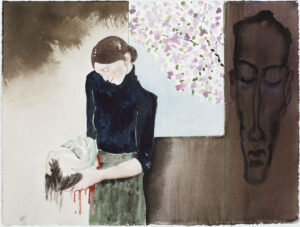

ASMR, 2020, watercolor and ink on Arches paper, 11 ¼ x 14 ¾ in. Copyright the Artist, courtesy the artist. Photograph by André Carvalho and Tugba

Carvalho – CHROMA.

Thus, the beating fantasy is also a fantasy of being born. Well, let’s not get ahead of ourselves. I’m a psychoanalyst. Everything reverts into its opposite—it’s also a fantasy of dying, of having been beaten to death. This was its more important underside for Freud. The difficult recognition of our mortality. I told you it was wild.

***

Why am I telling you about all this arcane psychoanalytic knowledge in a book about an artist? The story of Freud’s beating fantasies is also part of our tale, the origin story of Kantarovsky and myself. The first time we met, I had just finished speaking about masturbation fantasies in a lecture. His tone imparted a kind of urgency, and I took an interest in his work. And there it was: Kantarovsky as the boy being beaten, the boy beating himself, beating another—this whole phantasmagoria of negative pleasure upon which the minor joys, the ephemeral moments of happiness, rest. Sometimes that background needs to be placed in the foreground. More often, Freud said, what we call pleasure is in fact the removal of unpleasure. Sanya also told me that so many of his figures break the fourth wall, soliciting the viewer with a plea: Help me. One can’t help but think of the opening of Nathanael West’s Miss Lonelyhearts, letters that all say, Help me, “stamped from the dough of suffering with a heart-shaped cookie knife.” Or a heart-shaped painter’s brush …

This is what I put before you in my exegesis on Kantarovsky and beating fantasies: the improbable will to break yourself, your body, your mind, to locate this inkling of tenderness that is there, but always just out of reach or focus. All representation, all figuration, seems to collapse in on itself at this Archimedean point—what you say but can’t express, what you see but can’t perceive (or say you perceive), what you know but can’t really believe. Most are seduced by the idea of saying, seeing, knowing. It takes someone as suspicious and worn down to finally remove himself in the way Kantarovsky does in these works. As he said to me, “Everyone is trying to get out of their own way … but paradoxically, they’ve also already disappeared.”

How to stay with this painful stirring? In Freud, the artist always did this best, somehow working at the limit of repression while, as he said, keeping repression intact. They never know what they are doing. Kantarovsky always eschews knowing what he is up to. This isn’t a posture—at least when it’s this real. For Freud, artists work with what is painful in themselves, deriving satisfaction from it in the form of the final product, but rarely wanting to know with any clarity what the object they produce is about. Freud admired this doing-not-knowing. He said it must be the same for the true scientist. He considered this practice the epitome of what civilization can achieve beyond pure destruction.

Self Care, 2020, watercolor on Arches paper, 14 ¾ x 11 ¼ ins. Copyright the artist, courtesy the artist. Photograph by Pierre Le Hors.

One cannot get a sense for Kantarovsky’s paintings without understanding that they are on the hunt for this fragility. Also, that they are wild and speculative in the same way as Freud was in this paper—not only with their supposed content, but with paint, with brushstrokes, with materials as well. What appears to belong to individuals at their most grotesque, or desperate, or depraved—my masturbation fantasy, my neurosis, my pain—are shown as the only keys to the universe, best delivered to an audience through the complexity and negative consciousness of material mediums. As Angie Keefer wrote of Kantarovsky,

Kantarovsky’s paintings are good faith representations of bad, which demonstrate, paradoxically, that there is no such thing. That’s because bad faith constructs rely on oversimplifications, eliding difference and specificity to substitute one thing for another: a straw man for a disputant; a category for an individual. Therefore, bad faith representations tend to collapse under good faith consideration—i.e. scrutiny—that niggling executor of nuance, complexity, and specificity.

And it turns out that this universe is not so much made of our failing attempts to create categories and other species of judgment (to finally “appear”)—this would drag him into the world of narrative-based figurative painting—but rather, an effort that is reduced to materials, gestures, and sensation, and spills out into pigments, paint, watercolors, lacquer, splotches, erasures, and a whole prismatic array of colors.

Here, Kantarovsky can’t hold still. Unrelenting and almost attention-deficient, he must use everything in the history of painting at his disposal. He also does so with a demeanor opposite to his subject, painting with glee and optimism, with brazen exuberance.

***

A final word on melancholia. In 1917, a few years before Freud wrote “A Child Is Being Beaten,” he turned his attention to “Mourning and Melancholia.” The outlines of the beating fantasy appear there. Freud tries to understand that melancholic who berates himself, beats himself so adamantly, insisting on his worthlessness. “We see that the ego debases itself and rages against itself, and we understand as little as the patient what this can lead to and how it can change.” But, by looking at what mourning achieves, we might try to intuit what is taking place for the melancholic patient: namely, the acceptance of the loss of something or someone loved, an acknowledgment that they are deceased and need to be given up by an unconscious that refuses death. Freud writes,

Just as mourning impels the ego to give up the object by declaring the object to be dead and offering the ego the inducement of continuing to live, so does each single struggle of ambivalence loosen the fixation of the libido to the object by disparaging it, denigrating it and even as it were killing it. It is possible for the process in the Ucs. [unconscious] to come to an end, either after the fury has spent itself or after the object has been abandoned as valueless.

He notes that, between the two outcomes, it is not clear to him which is more successful or what they lead to. Though he acknowledges that, with the second, the ego might rejoice in an outcome that declares itself superior to the object given up. It’s another of those moments in which you see Freud smile wryly, because this renewed narcissism would set the foundations for another melancholic battle in the future. The expenditure (or draining) of rage then would be preferable. He says this without saying it.

In psychoanalysis, the most enigmatic, intense, and ambivalent battle around loss and separation is the one fought with the mother. Certainly, a kind of rage at the mother for what she couldn’t do or be for you; a rage that enlarges her as an image that must be taken apart, dismantled. As the psychoanalyst Adam Phillips has noted, the wish to be understood may be our most vengeful demand, “the way we hang on, as adults, to our grudge against our mothers; the way we never let them off the hook for not meeting our every need.” Only in reckoning with this universal melancholic rage against mothers can we perhaps locate new forms of tenderness—toward ourselves, but also toward women and children.

“A Child Is Being Beaten” was Freud’s next attempt to speak to this wish, this ambivalence, this violence, and this search. For what is beating if not also the rhythmic stroking of a mother? The necessity that she say no countless times, the longing for contact that can never fully be met, the feeling of an obstacle that was never a material one. Kantarovsky’s latest works are poised on this edge. It’s a world of mothers and small children, ghosts, intimate encounters, bodily embraces, endless longing, and fears that break not on the side of anxiety but of shame. Kantarovsky’s palate changes. There’s something even more internal to the works, as if we aren’t only inside the mind, but within a body.

Badgirl, 2023, oil on canvas, 15 ⅗ x 39 ½ in. Copyright the artist, courtesy the artist. Photograph by Jeffrey Sturges.

Huge portions of his canvases are now blank, monochromatic, or become dark spaces. He’s painting over something. Getting rid of it. Only leaving slight traces. Moving away. Separating himself even more strongly. The feeling is decidedly domestic, even when otherworldly. I feel as if I’m being brought into an uncanny space, which, as Freud noted, implies feeling not at home in something that is decidedly one’s home. He also said it must have to do with mothers, our original home. The image sequence of this monograph ends in this minimal space, with a gesture toward tenderness, the mother figure. Leaving behind the whip. Just a crack, nothing more. But you can almost smell her—as if the painterly materials he’s now exhausted change form, aerate, enter the senses differently. Not as a blow, but as a breath.

From Sanya Kantarovsky: Selected Works 2010–2024 , to be published by MIT Press this month.

Jamieson Webster is a psychoanalyst and the author, most recently, of Disorganization and Sex and Conversion Disorder: Listening to the Body in Psychoanalysis. She is also the cowriter, with Simon Critchley, Stay, Illusion!: The Hamlet Doctrine. She teaches at the New School for Social Research.

October 23, 2024

Pull-Up Diary

Photograph courtesy of Mitchell Johnson.

July 14, 2024

I went to the neighborhood gym for the first time today. Until now I was driving, sporadically, to the university gym where I get in for free, but only sporadically. So I paid forty-five dollars for a month of entry to this one. I’m trying to get stronger. Bigger, too. It sounds boring because it is. I am a twenty-seven-year-old gay man who has started going to the gym. I have all the standard gym desires: strength, size, beauty, health. The trouble is that these are poorly defined, with few benchmarks. So I have come up with a more specific goal, too: I would like to do a pull-up. Overhand, unassisted. Right now I can kind of do one if I start with a little jump, but when I try a true pull-up, the best I can do is retract my shoulders and bend my elbows a little before my strength gives out.

The neighborhood gym is run by a Ukrainian family. The daughter, no older than fifteen, signed me up. It’s small and not very nice; the dingy locker room reminds me of my middle school’s. Mercifully, though, it’s uncrowded. Today I’m starting with assisted pull-ups on the assisted pull-up machine, which has a pad for your knees and a counterweight to help lift your body up. I tried it with forty pounds of assistance, then fifty, and then finally, at sixty, I could complete five. Then I did the rest of my workout, with various machines and weights and benches, and walked home.

July 16

I am mostly allergic to routine. An old roommate once noticed that each night, after brushing my teeth, I would leave the toothbrush in a different spot in the bathroom.

Three years ago I bought a pull-up bar from Target. I had the same goal then as now. When I installed the bar, I assumed I’d be able to do a few pull-ups right away. Not so. My failure surprised me. I thought pull-ups were a more achievable physical feat, like touching one’s toes. It seems intuitive that a body should be able to lift itself. Not so.

The pull-up bar still hangs in my kitchen doorway, taunting me. Every so often I make an attempt. It’s become one of several objects that remind me of aborted self-improvement projects: a notebook half filled with morning pages, a yoga mat gathering dust in my closet.

Today a friend came over to my house, saw the pull-up bar, and tried it. “It’s so hard!” she said, her legs flailing. “It hurts my insides.”

July 31

Went back to the gym after ten days out of town. On vacation in Oregon, with my family, I didn’t work out a single time. On the plane home, I watched an episode of Succession with Alexander Skarsgård in it and thought, I’d like to look like him. He probably works out even when he’s on vacation. But he’s rich, of course, and likely does other extreme things like steroids and blending chicken into smoothies. Still I would like to look more like Alexander Skarsgård than I currently do. I’m 6’3, almost his height, but far skinnier.

Today I felt weaker than before the trip, but maybe that was in my head. I set the assisted pull-up machine to sixty pounds and could complete only four before my arms gave out. I moved on, humbled, to the leg press.

I’ve googled “how to do a pull-up” a few times, which has inspired Instagram to start showing me Reels about it. One man with shoulders like cantaloupes explains proper technique. Arms no narrower than shoulder width, he says. You don’t want your body just dangling loosely in space. Tense your core, move your shoulder blades back and down. You want your body to behave as one singular unit.

He makes the motion look instinctual, fluid. He’s like a frog in a documentary jumping off a leaf in slow motion. For a moment, he is totally integrated. A vector of pure movement, unfettered from his own hulking body. He floats.

When I attempt it in the gym, I feel disjointed, my arms and shoulders and back each feebly trying to hoist me. My person hangs limp. Dead weight.

August 2

Another tip from Instagram: Instead of trying to pull yourself up toward the bar, imagine you’re bringing the bar down to you. Hold it in your hands and imagine breaking it overhead, like a stick. There are all kinds of tips in this vein. Pull-ups are a matter of both strength and technique, and it is hard to tell in what proportions. Videos like this are appealing because they make it seem intellectual, a problem that can be solved with better theory.

I tried envisioning breaking a stick in the gym today, per the influencer. I tried it unassisted, on the normal pull-up bar, because it seemed like this new mindset required total faith. The machine and its counterweights might interrupt the clarity of my vision. My hands white-knuckled around the bar. I moved my shoulder blades back. Stick, I thought. You are breaking a stick in your hands. I floundered in front of the girl at the front desk and a man sitting in a chair by the window. Face hot with shame.

August 5

Grip strength is a concern. Sometimes what falters is not the shoulder or back muscles but the tiny ones in your fingers. “The best way to start is by hanging,” my boyfriend, who can do a pull-up, texts me. If I can hang from the bar for thirty seconds, then I should try retracting my shoulder blades and activating my core and hanging in that more stressed position for thirty seconds.

I hang for thirty seconds. Then I retract for thirty seconds. My body starts shaking, but my grip lasts. Then I try to pull completely up, a Hail Mary I already know won’t work.

August 7

Machine still set to sixty pounds. Seven completed with great effort, then some dumbbells, cables, etc. “Arm day.”

When I ask him, my friend Colin tells me he can do ten pull-ups. He recently started going to the gym, too, more often than I do, but for the same gay reasons. We are both nearing thirty.

“Sometimes I get worried about symmetry,” Colin says, because his left arm is a little smaller and weaker than his right. Henry, his boyfriend, chimes in to say he thinks these concerns about bodily symmetry sound fascist.

August 9

Going to the gym is mostly a slog, drudgery in service of vanity. It is stultifying to lift objects surrounded by mirrored walls. In my earbuds a vapid podcast plays and beyond that, on the gym’s speakers, Pitbull. The only redeeming thing about the gym is that it’s erotic, which for me manages to redeem it almost entirely.

I ogle. Today there was a short, buff man doing cable rows and grunting, back arched with his ass pointing skyward in tight shorts. There was also a tall, curly-haired man on the bench press, who wore a sweatshirt for the first set and then stripped to a tank top once his arms were plump enough to show off. Fantasies of illicit sex in the locker room. I wondered if they saw me and what they thought. My physical appeal has always been more fey, twinkish—like a Renaissance apprentice, or a canvassing Mormon. I’m not sure it plays here.

I’ve been reading Edmund White’s 1980 book States of Desire: Travels in Gay America. In Los Angeles he visits a gay gym, with a row of Nautilus machines “as gleaming and forbidding as the blades of the Cuisinart.” They call it the assembly line. Gay men in LA, White writes, “have to be well built; they expect good mileage out of themselves and easy handling.” Nearly fifty years later and far beyond LA, in a tiny Ukrainian gym on the north side of Chicago, the desire remains the same. Reading White’s description, I feel implicated in a long, tiresome lineage.

August 11

I’ve been going to the gym about three times a week, and each time I do the assisted pull-up machine, I am stuck at sixty pounds. Sometimes I can lift myself at fifty, but then only once. A pull-up is binary; one can do it or one can’t. Until I’m on the other side, it feels like I’m making no progress.

Instagram Reels is full of men. They tell me that leg workouts increase testosterone, improving performance for the rest of the body. They tell me that releasing the weight is as important as lifting it, so I try to go down slowly. They tell me I should eat my body weight and then some in grams of protein, which I don’t count, and that I should take various supplements I’ll never buy. Many of them are gay. The ones who aren’t might as well be, so earnestly are they obsessed with the male body. Physically they are often attractive but just as often uncanny, all veins and bulging lumps. Steroid use seems rampant. Everyone talks about this, but still: The standards these men adhere to seem obviously unhealthy—not to mention ever inflating. I wonder when homosexuals will reach peak size.

August 15

Pull-up is an embarrassing word, and I don’t like to say it. Today I remembered a prior association I had with it: It’s the brand of diaper worn by toddlers after they graduate from their first diapers. I was made to wear them for years as a child because of my bed-wetting. So the word is classically overdetermined, evoking multiple humiliations, indexing my bodily failures.

I saw an acquaintance at the gym today, a guy who lives in my neighborhood. He’s huge, bursting out of his tank top. His arms are the size of legs. Straight, despite his mustache, and loves his girlfriend a lot. A scholar of Walter Benjamin and an anarchist. I wonder why he goes to the gym so much. I like to imagine he’s preparing for the revolution, but maybe it’s shallower, just for looks. Maybe his girlfriend loves it, and they have crazy sex.

September 3

Two weeks without a workout. I went to protests of the Democratic National Convention, then caught a brief illness, then had a multiday depressive episode in which I leaned further into many bad habits: smoking, long naps, watching more Reels. Optimized people loop on my screen, exalting various high-protein meals and cheery kettlebell hacks. Now it is after Labor Day and thus time to change everything. Starting now, I will lead a worthwhile life. A girl in my phone standing in a stark white kitchen tells me the new moon has the potential to bring me blessings, if I set my intentions now.

Trying to get serious. A vigorous attempt today on the kitchen bar brought me what I will generously call halfway up. Halfway up! Progress!

Later that day

I went to the gym and to my surprise was able to complete one pull-up on the machine at only forty pounds assistance.

September 6

This month, my boyfriend’s gym across town is celebrating its thirty-third anniversary with free guest passes every Friday, so I tag along. He thinks the owners are Christian and are making a big deal out of thirty-three because that’s how old Jesus was when he died. The front desk staff and much of the clientele do seem religious. It’s a huge facility next to a hospital, filled with old people rehabilitating and younger people at the weight racks and treadmills. Everyone trying for eternal life.

The place is much nicer than my gym, with various heated pools and saunas and stretching machines. He takes me to a pull-up bar and demonstrates a pull-up at my request. Then I try and fail. Use your core more, he says. Pull with your back, not your arms. I get a little higher. Breathe out on the way up. He describes a feeling of inner lift, emanating from my midsection, that is impossible for me to imagine.

Afterward, he says it’s likely harder for me because I’m tall, which restores my ego. We do some other exercises and go to the steam room.

September 8

Every day, new Reels, offering new pull-up programs. A Scandinavian woman with beefy, cabled arms, in a blue Lycra top and matching yoga pants, outlines one:

“If you can hang from the bar for thirty seconds, then you’re ready for scapular rows. And when you unlock ten scapular rows, then you’re ready for scapular pull-ups. And when you unlock ten scapular pull-ups, then you’re ready for Australian rows. And when you unlock ten Australian rows, then you’re ready for jackknife pull-ups. And when you unlock ten jackknife pull-ups, then you’re ready for jackknife top hold. And when you unlock a ten-second hold, then you’re ready for band-assisted pull-ups. And when you unlock five band-assisted pull-ups, you’re ready for band-assisted top hold. When you unlock a ten-second hold, you’re ready for negative pull-ups. And when you unlock five negative pull-ups, then you’re ready for your first pull-up.”

Another video, of a different woman in a chartreuse sports bra and black compression shorts, demonstrates a “viral floor pull-up hack” that involves lying face down on a towel and pulling herself around her apartment with her arms.

Watching these exhausts me. I confront the flimsiness of my own desire; I want it but not nearly that much.

September 10

At dinner with some friends, we discuss the most normatively gendered aspects of our personalities. Someone mentions her long-running interest in spinning wool; another his love of baseball. One woman says how much she likes having things carried for her. I mention the gym, my quest to do a pull-up. The guy who loves baseball, who is also the only other man at the dinner, says, “I want to do a pull-up, too!” It makes me wonder how many men can even do one, and after dinner I look it up and the answer is only 17 percent. There’s no data for the percentage of men who want to do a pull-up, but I wouldn’t be surprised if it’s close to 100. Every man I’ve asked about pull-ups has had an opinion.

September 16

Reel of a gray-haired woman, sixty-five years old, taken over the course of five weeks as she attempts to lift her chin over the bar. By week five she is all the way up, beaming, accomplished.

I’ve been trying to do a pull-up, on and off, for nine weeks. On the bar in my kitchen, I can now pull myself, generously speaking, halfway up. Elbows bent at an almost right angle but no farther. From underneath the bar, I imagine my life above it. I imagine that hoisting myself up will feel like flying, like cumming, like winning a big award. In truth I know it will be satisfying but not entirely. Then I’ll want to get to two, then five, then ten.

If I had kept a more consistent routine, I would likely be more successful by now (a lament I have for any number of things). I tried to write a book this summer, too, and got only what might be generously called halfway. Every summer I set big goals, envision profound changes, and then the season slips away.

Mitchell Morgan Johnson is a writer who lives in Chicago.

October 22, 2024

Arachnids

Colored engraving of a large scorpion, Buthus granulatus. Courtesy of the Wellcome Library, London, and Wikimedia Commons. Licensed under CC0 4.0.

1.

In the weeks before I left for Mexico, the flies showed up. My apartment became overrun with them, the size of small red grapes, five to ten ripe orbs at a time buzzing around in any given room. A fly or two had never bothered me, so I was able to balance my pacifist instincts with a more rigorous approach to housekeeping; I took the trash out every other day, and if I saw an errant roach in the bathroom I would kill it, the way you wash a glass in the sink without thinking twice. The flies radicalized me. They wheeled through the apartment, attacking every cubic foot of open space, refusing to be ignored. It sent me into a fugue state of bloodlust. I wondered if there was a corpse they were drawn to that I couldn’t see. Maybe I was the corpse.

I became obsessed with stalking and killing every last one of them, fantasizing that if I could annihilate them all before the sun went down, the problem would be solved. But it never worked. I slaughtered twenty-five at a time—my windows, ceiling, and rolled-up copies of The New Yorker splattered with gore. I’d wipe down nearly every wall and window in my apartment to keep other flies from coming back for the blood and guts. But they always returned.

But I never killed the spiders in the apartment, as a rule. I reasoned that they would help keep the place clean by catching flies. They didn’t. I resented them for not pulling their weight. “Do better,” I whispered, gently but not kindly, crouched over one little

translucent creature

coterminous with the dust

behind my bookcase.

2.

I took the trash out again before I flew to Mexico City to meet Andrés, bringing along a copy of my book for his family in Chiapas.

On the far side of the Plaza de las Tres Culturas—Andrés insisted we go straight from the airport—pyramids decked out with little spirals carved into the stones, like the phonemes of fingerprints. At the top of the square there was a massive Spanish colonial cathedral built with those same stones, stolen from the pyramids, punched through with blue windows glowing in the rain like the frozen blood of blacklight. Finally, across from the pyramids, a towering block of public housing—on its roof, in 1968, President Ordaz had sent snipers to shoot the students gathered there to protest his government in what became known as the Tlatelolco Student Massacre. This place is a microcosm of what goes on here, Andrés told me: Teotihuacan, the Aztecs, the Spanish, the communists, something keeps getting violently overthrown.

In the morning we headed to Coyoacán for breakfast. It was September 19, the date of not one but two devastating earthquakes, in 1985 and 2017. To commemorate this uncanny twin anniversary, and in honor of the thousands killed by a combination of terrible luck and criminally shitty infrastructure, the city now runs an annual earthquake drill. Sirens went off as Andrés and I were having coffee. We walked outside into a small plaza, led by smiling volunteers in orange vests, and stood patiently, waiting for nothing to happen.

From under our feet, a silent chord rippled through us. We looked at one another. “Do you feel that?” I said. Slowly at first, gathering force, a hanging lamp swung

like a pendulum,

the planet twisted inside

its elastic shell

and then the ground went still. Purple jacaranda blossoms fluttered from the trees. Several people in the plaza crossed themselves. Later, a researcher calculated that the odds of a third earthquake happening in Mexico City on September 19 had been somewhere between 0.000751% and 0.00000024%. As we finished breakfast, Andrés looked at his phone and shook his head. His father had texted: “The dead are kicking.” We hit the road.

3.

Andrés and I met in a freshman English class, gleefully arguing about the Iliad. It was a deep and occasionally caustic bond. After we graduated, he and his brother Juan and I shared an apartment in Brooklyn. Juan and I never quite took to one another. He was a painter—brooding, strange, and quietly volcanic. When we first met, he asked if I would make art as the world were ending—that’s the kind of question he asked people when he first met them. It was a test. My answer—probably not—was a drop of poison in our relationship. I had little patience for this brand of purity and found his pious death drive clownish and immature. We lived together for a miserable year in the depth of the 2008 recession and then parted ways—Andrés and I to grad school in different cities in the Midwest, Juan back to Mexico to paint.

I wrote an elegy called “The Art Buyer,” not long after receiving word that he had slipped on a rock and fallen into a waterfall he’d been painting in Las Nubes, a remote part of the Chiapas rainforest by the Santo Domingo River, where Andrés and I were now driving. Or was it an elegy? I loved Juan, but the love felt strangely vacant, like a doorway you keep expecting someone to darken. It was that kind of poem. One problem with elegy is that it tends to valorize its subjects, erasing ugliness in all directions, including in the poet—I tried to foreground my strain with Juan in my own poem, which Andrés liked. He likes conflict and disagreement. I like to remind him of it.

At some point many years ago, I bought Andrés a copy of The Mooring of Starting Out, a collection of John Ashbery’s first five books, which he never read. I found it on his shelf as we were packing and threw it in the car. We argued about it.

“The problem with Ashbery is he’s too American,” Andrés said, driving us through the weaponized vegetation on the road between Puebla and Oaxaca, having never so much as read a whole poem, trying to bait me. In college, at the height of the Bush administration’s war in Iraq, I’d once tried to disavow my status as an American. The country was nothing but a bunch of jingoistic pigs, I claimed, and I wanted nothing to do with it. He was livid. “Of course you’re American,” he replied, shaking his head. “You’ve benefited from this country your entire life. Claiming you haven’t only proves it.” He wasn’t always right, but he was that time. And that’s how it is with us. He playfully asked me to fight him once, then punched me in the head so hard he fractured his hand.

He wasn’t wrong about Ashbery either. Particularly in the early books, Ashbery is the consummate expat—imbued with a folksiness artfully deranged by tangled, sublimated desire and grief, perhaps even violence. Some attribute this to Ashbery’s sexuality, others to the death of his own younger brother in childhood. Andrés had sniffed out the microtonal dissonance of a sublimely gifted, uneasy agent of American empire. It is difficult not to sense the covert action and longing that charge from the poems’ margins. Even when he is faithfully describing a painting, his presence changes it.

Humoring me, Andrés listened intently as I read aloud from the book. I reached “These Lacustrine Cities,” the opening poem of Rivers and Mountains, and came to its final lines: “You have built a mountain of something, / Thoughtfully pouring all your energy into this single monument, / Whose wind is desire starching a petal, / Whose disappointment broke into a rainbow of tears.”

He was silent for a moment behind the wheel. “Whoa,” he said.

As we made our way into the mountains of northern Oaxaca, a cop pulled us over. Andrés rolled down the window. He stared at her blankly—she didn’t frighten him enough, or she frightened him too much. There was a thin burst vessel in the white of her eye. She searched our car on the side of the road. As she flipped through Andrés’s passport, her face was stony. But when she saw mine, she looked up at me and smiled. Then she sent us on our way.

We drove for three days, wending deeper into the forest, sometimes going hours out of our way to avoid roadblocks and checkpoints.

On the third day we entered Chiapas. Around a bend in the road, a group of masked men flagged us down. I shot Andrés a look.

“They’re Zapatistas, not Narcos,” he said, rolling his eyes, telling me to chill. He said hello and handed the men a few pesos. One gave us a pamphlet. They let us go with a friendly wave.

Hours later, we were driving along a lush ravine. Below, the Santo Domingo plunged between mountains.

“I want to show you something funny,” he said.

He drove into a parking lot near a series of lakes. Deep mineral deposits had colored them a shade of otherworldly blue, like the stained glass windows on the cathedral at the Plaza de las Tres Culturas. A slimy length of black rope hung awkwardly over the water.

I asked what the rope was for.

“You’ll see,” he told me.

We entered a small gazebo with a sign bearing a faded painting of a toucan and the words BIENVENIDOS A GUATEMALA, directly aligned with the rope over the lake.

What is a line? It’s not that borders aren’t real—they’re just imaginary. Here in the rainforest, standing before an unmanned gazebo, they seemed almost childish. If they didn’t result in mass death and dispossession it would be funny, the imposed psychosis of the whole operation coming into slapstick relief, a monstrous clarity—

enter here, not

here or here. This side is space

but this is domain.

We strolled through the gazebo into Guatemala. A dog emerged from the woods and followed us as we passed small houses and shacks, chickens running between the yards. Then it got bored with us and loped back into the forest.

4.

We continued until we pulled into the village of Las Nubes, paid for our cabin, and drove down a steep hill to the river. Summer was over, and there was no one else there. Hibiscus and bird-of-paradise flowers hung everywhere, and the spiked sunset skins of lychee covered the ground. A line of ants carrying hacked up bits of leaf five times the size of their bodies stretched into the forest. Toucan chatter fizzed from the trees. Beyond the cabins was the Santo Domingo, a faint roar. We dropped off our things in the cabin. Andrés warned me to zip my bag. “I accidentally brought a tarantula home once.”

We reached the path to the falls at dusk. We would perform our ritual in the morning—this was just to get a feel for the place. The river had overflowed, and we had to remove our shoes and lift them above our heads. The water rose to our waists. “I’ve never seen it so high,” Andrés said. The path sloped up and we stepped onto a stone platform fortified with rough mortar. There was a railing.

What can I say about what was beyond it? The water gave the most ferocious display of physical force I’ve ever witnessed firsthand. Mist gripped my throat from the inside; it sensed us, and we were of no particular interest. Above us, a cave pinched the river’s flow into a space the size of my bedroom, shooting through in a bone-crushing current that bloomed and tumbled down below us, widening hundreds of yards. This bottleneck accounted for the river’s relentless power. The entire landscape looked ready to crumble. From this close up, the roar of the water erased almost every other sound. In the small space above the cave, a hole punched clean through a mountain, a doorway waiting for someone to darken it, swallows flickering back and forth, whitewater leaping behind their hollow silhouettes. Spray dripped down our faces. On the cliff overlooking the whole scene the rock’s discoloration formed the unmistakable shape of a massive skull.

Andrés pointed to the railing. In this spot, for two years, some drips of acrylic paint from Juan’s last painting had endured the elements. But the river’s atmospheric cataract had by now stripped them away, save for one tiny speck of sky blue.

The clouds turned gunmetal as the sun went down. It was time to get back to the cabin. We waded through the water, a brown spider the size of my hand gripping a nearby tree trunk. We ran up to the cabin and the sky cracked open. There was no electricity, and it was dark. We lit cigarettes under the awning as rain bombarded the roof. When he took a drag, I saw tears in Andrés’s eyes, but they didn’t fall. “This place is so him,” he said. Frogs called out a rough symphonic drone. The hands in his wristwatch

phosphoresced, small v

rhyming with the glowworm

crawling at his feet.

We entered the cabin by the light from our phones. I opened the bathroom door to take a leak. On the floor, in the weak magnesium glare, I saw a large black scorpion.

5.

Andrés let out a low sigh, and I choked back a scream. I had never seen one in the flesh. Usually when we confront something we fear, reality turns out to be softer than the monstrosity our psyches have concocted for us. But the scorpion was precisely as horrifying as I’d imagined, a creature plucked directly from childhood nightmares. “It must have come in through the shower drain,” Andrés whispered, though there was no one around for miles. “They travel in pairs.” We didn’t see its mate.

We quickly hatched a plan: We would place a cup over the scorpion, and in the morning we would slip a piece of paper underneath and transfer it outside. But when we dug through our bags, we found we didn’t have a cup or any other tools to deal with the situation at hand.

“If Johnny were here he would just let it be,” Andrés said. “He let them crawl all over him. Never even killed a roach.” I recalled Juan staring at a silverfish in our shared bathroom with a dark beam of murder emanating from his face, but I held my tongue.

We turned our flashlights back to the floor. The scorpion was gone.

We looked everywhere—behind the toilet, in the corners, and, shielding our faces, on the ceiling. Then I turned my flashlight to the corner by the door. At eye level, between the second and third hinges, spiked black feet rippled slowly up the jamb.

A pincer reached around the wood, and a long, segmented, prehensile tail dragged a venomous little knife behind it, curling.

“Cute of Juan to let this crawl on him,” I said. “But what about you? Do you want to wake up with this in your bed?”

He considered it for a moment. “I don’t.”

There was only one option.

“I’m sorry,” Andrés whispered. I pulled the door hard, slammed it shut, my knuckles white on the knob. When I opened it again, the scorpion’s dead weight fell from the jamb to the floor with a sickening click. Our light fell on the little creature, intact but slightly flattened, motionless on the ground. Andrés sighed. Johnny would have let it live.

“Are you sure it’s dead?” I said.

“I don’t know man, it looks pretty fucking dead,” he said.

“It does look dead. It’s dead.”

He ripped out a page from his journal to scoop up the body.

The tail curled. A pair of pincers reached up through the damp air.

In a single motion, Andrés pulled off his boot and slammed it on the ground five times until the scorpion was a black smear on the tile.

“Now I’m pretty sure it’s dead,” I said. I was uncomfortably aware of my pulse. Andrés brushed black exoskeleton and guts onto a ripped notebook page. When you neutralize

the the you fear most

back to its indefinite

article, there is

nothing you can do but confront it in your dreams. He checked his sheets, crawled into bed, and immediately fell asleep, breathing heavily. I lit a candle, sat down at a desk, cracked a lychee open, and listened for what was talking in the rain’s static on the roof. I wrote this down. A green and black spider crawled across my notebook. I picked it up, cracked the cabin door, and sent it out to make a home between raindrops. I returned to the desk. Wind blew hot wax across the words. A second spider appeared on the page.

6.

The water had risen overnight from the rain, and by dawn, when we were back at the river, it reached up to our chests at the lowest point of the trail. We approached the platform and lit three votive candles. “These will go out in two minutes with all the mist,” Andrés said, “but whatever.” We stepped to the edge of the platform, and he nodded at me to start.

I read the “The Art Buyer” slowly, almost shouting each word so Andrés could hear, though he was right next to me. “Poetry has done its work on you,” I read, though I did not remember writing that. As soon as my voice hit the air it sounded like a whisper. The pages of the book turned pulpy as I read, the text blurring in the moisture. When I ripped them out they tore smoothly, without a sound, like flesh from a steamed fish. One by one I threw them in long, slow arcs into the Santo Domingo, which instantly whipped them away; they seemed to dissolve just before hitting the water.

When I finished, we grinned. We were drenched. The cliffside skull above us stared into the clouds. The candles had melted into a pool of wax. We left them burning.

All this actually happened, but none of it is real, except as poetry. I render this border almost automatically, without trying, starting with the word “I”: Here I am, in this line of text, where I am not. But this line is porous—it has holes that no one can account for where poetry, reality, the living and the dead, slip back and forth undetected.

“Reading you reading me,” Andrés texted me the other day, after looking at an early draft of this account, “I feel perhaps distant, oracular. Priestly maybe. Which is fine, it’s a role I can certainly play. But we have all kinds of disagreements that your more mythological retelling of the trip occludes.”

“You love disagreement as an aesthetic ideal,” I texted back.

“I don’t agree!” he replied. I laughed.

The day after we left Las Nubes, as we were driving through Chiapas, a tiny chapel on a steep hill appeared up ahead of us. Apparently San Andrés walked there, Andrés told me, and sometimes people burned offerings by the chapel.

I asked him to pull over.

At the top of the hill I took the remainder of the book from my backpack—“The Art Buyer” now torn out—spreading it over the ash as Andrés watched, lighting the damp pages that somehow still burned, the flame turning blue and green as it crept up the spine and touched the cover, and when the poems crossed from one state of matter to the next the distance was next to nothing

through the air’s net, gray letters

legible for one

or two seconds in the breeze.

A light rain began to fall.

Daniel Poppick is the author of The Police and of the National Poetry Series winner Fear of Description.

October 18, 2024

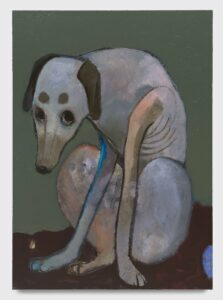

Do Dogs Know What Art Is?

Photograph courtesy of Laura van den Berg.

Do dogs know what art is?

Oscar is a big, “free-spirited” Lab mix. My husband and I adopted him when he was just a few months old. We’ve lived together as a little family for over a decade. When Oscar was a puppy, I did a one-semester residency at Bard College. I used to walk Oscar off-leash on campus, and one afternoon he bounded up to what looked like, from a distance, a small pond. He got into the water—which seemed, in hindsight, a little shallow for a pond—and started splashing around. Within minutes, a furious campus security officer was running in our direction, waving his arms. Turns out the “pond” was actually an installation called Parliament of Reality by the renowned Icelandic Danish artist Olafur Eliasson, though I will forever think of it as the first place I ever saw Oscar swim.

How different our experiences with art must be. My initial response is usually cerebral—a judgment, an idea, an association—but when something really moves me I feel it in my body. Once, at a Korakrit Arunanondchai installation in Paris, I fell briefly asleep on a giant beanbag wedged deep inside the light and noise of the exhibit and woke up sobbing. It took me hours to return to earth, and when I did I felt a lightness, as though something had been exorcised. Dogs, meanwhile, are creatures of sound and smell. Oscar moves with his snout to the grass, pausing for deep, forensic sniffs. His impressions are peopled by the smells of everyone who’s made contact with this same patch of earth. Canine perception is collaborative. Dogs are pack animals; they are always among.

When Oscar was younger, I would sometimes grow impatient with how much time he could spend smelling one little spot. Then a dog trainer told me, “Imagine someone says, ‘I’m going to take you to an incredibly beautiful place, and we’re going to go for a walk. It’s so beautiful there, you’re going to love everything you see. And then when you get there the person puts a blindfold on you. That’s what it feels like for your dog when you don’t let them stop and smell.’ ”

Now we live in the Hudson Valley, and Oscar and I walk around the Art Omi Sculpture and Architecture Park in Ghent most mornings. Art Omi spans a hundred and twenty acres of rolling green fields dotted with large sculptures and installations. Oscar seems to like interacting with the art, and his way of interacting seems ideal to me—kinetic, bodied, hyperpresent to the granular details of scent and texture. It’s the way more of us might experience art if we were not weighed down by the tug of the future, the call of a looming to-do list. He loves weaving through the colorful Pac-Lab, each wall of the maze hand-sculpted from clay by the artist Will Ryman. He sniffs his way through the maze—some of the walls are painted primary colors, others are black or white—tail held high. Dogs belong to the moment; he takes his time. Cameron Wu’s Magnetic Z looks to me like an abstracted castle or a ship. A long ramp swoops around the back, forming a snail-shell shape; stairs lead to a pyramid tower. The first time Oscar came across Magnetic Z, he climbed into the tower without hesitation. He has a thing about wanting to climb. He likes to find the highest point, whatever it is, and look around—or, more accurately, smell around. His nose will twitch, especially if there’s a little wind.

One morning we came across Beom Jun Kim’s Other Places, which is deep in what’s called the Architecture Fields, one of the more remote parts of the park. Art Omi describes Other Places as a “sunken outdoor room carved into the earth.” From above, it looks like three squares of descending size nested inside one another. Each square provides a shallow ledge for visitors to sit on. The grass covering the ledges has a tufted, almost hairlike look to it. Other Places does not go that deep, but the incline down is sharp. A pale swatch of dirt awaits at the very bottom, in the narrowest part of the hole. This is a site-specific commission, installed earlier this year, and yet it has a forgotten aura about it, like part of a structure or a design that someone started and then abandoned. Or like something Jeff VanderMeer’s team of explorers might discover inside Area X, mysterious and a little menacing.

The first time I found Other Places, I was sure Oscar would want to use his goatlike agility to climb down into the dirt bottom. The description noted that visitors were meant to “leave their imprint on the grass surfaces … a physical embodiment of memory and forgetting.” The hairlike grass was yellowed in places from the strong summer sun and all the bodies that had already descended into the sunken room. Still, I thought I should discourage Oscar from going in. He delights in making any hole he finds bigger. Some serious small-town dog drama unfolded at Art Omi last year—after an unspecified biting incident at the park, dogs were banned from entering for most of the day. Major pushback from dog people culminated in a public town hall, after which dogs were swiftly reinstated, though there’s a lingering feeling of dogs being on thin ice.

I didn’t need to worry. Oscar was not himself in the presence of Other Places. He trotted around this strange gash in the earth, ears pinned; he sniffed the grass. He looked skittish and wary and not at all like the same dog who, upon seeing the ocean for the first time, ran in so far that waves crashed over his head. He held out one paw, as though he were testing a force field I couldn’t see. I sat on the second-lowest ledge, then dropped down to the lowest ledge and wedged myself into the dirt square at the very bottom. I felt the strangeness of being below the surface of the earth. I looked up. The clouds were passing overhead with an uncanny briskness. I was visited by a vivid memory of the basement in my childhood home—the creaking steps, the pooling shadows, the film of dampness on the walls.

A sharp blast of sound pulled me out. Oscar was hovering around the edges of the hole, bouncing around and barking. He didn’t like that I was down there, and he didn’t feel like he could follow me. I had felt comforted down in that hole; he had felt disturbed. Our experiences with Other Places were beyond what the other could understand—which is sometimes how it goes with art. After I climbed out, he raced back to the main path, eager, it seemed, to put distance between us and that hole. It occurred to me that normally Oscar’s the one who explores the art while I play the role of attentive observer—watching, taking photos, calling to him when it’s time to go, brushing insects and grass from his fur. When I get up to write in the mornings, he follows me to my office, where he naps on a dog bed next to my desk. When we’re out on the trails together he likes to stay close. I wonder if my subterranean descent felt like a loss to him, or a threat. He needed to pull me back to where I belonged.

Laura van den Berg is the author of six works of fiction, most recently the novel State of Paradise.

October 17, 2024

Baking Gingerbread Cake with Laurie Colwin

Photograph by Erica Maclean.

In the Laurie Colwin novel Family Happiness, a mother and daughter get on the telephone to discuss the menu for an upcoming family dinner—either a roast leg of lamb or roast beef, with potatoes and, the mother says, “those lovely cold string beans of yours for a second vegetable.” Colwin writes: “On both sides of the line, mother and daughter settled down for the conversation they enjoyed most: what to serve with what for dinner.” The two agree to decorate the table with quince branches and have apple pie for dessert. The scene is quintessentially Colwin: it’s relatable, but glamorous too. It paints a picture of a kind of idealized family life that few people actually experience. I’m especially struck by the phrase “second vegetable” and all that it implies about a particular culinary tradition: Some people think two vegetables at dinner is de rigueur, but I’ve encountered those people only in books.

Colwin’s other novels include Happy All the Time and Another Marvelous Thing. Photograph by Erica Maclean.

Colwin, born to an upper-middle-class Jewish family in Manhattan, wrote five novels and enough essays for Gourmet Magazine for two collections of food writing before her death in her sleep in 1992 at age forty-eight from an aortic aneurysm. Home Cooking, one of those collections, has been pressed upon me countless times when people learn I write about food. Despite Colwin’s early death, she has remained in print, and all her books have been recently reissued. Colwin was married to Juris Jurjevics, the founder of Soho Press, and both her adult child, RF Jurjevics, and her longtime friend the writer and academic Willard Spiegelman say that her two interests—fiction and food—were really two facets of an overriding interest in people. She loved to bring people together over dinner, talk to them, and get their life story. “Laurie often had people in the kitchen before a meal, and she would often start her inquiries there,” RF Jurjevics told me recently over the phone. “My father told me that how he knew Laurie was going to begin in earnest was when she would ask her subject, re: their romantic partner, ‘So, how did you two meet?’ ”

Gingerbread in process: my recipe, which is different from Colwin’s, starts out with a liquid batter. Photograph by Erica Maclean.

The idealized domesticity—the mother and daughter on the telephone discussing vegetables—that crops up in Colwin’s work, however, is only the beginning of the story, and was elusive in her own early life. The daughter from Family Happiness, Polly Solo-Miller Demarest, turns out to have been people-pleasing for a lifetime, most especially in her relationship with her mother. Polly wants to have a “perfect” and “effortless” life like the rest of her family, but she is secretly having a tortured affair with a solitary Downtown painter who wears “briary” fisherman sweaters. Colwin’s mother, Jurjevics says, was “difficult.” She was a grande dame who served dinner with crystal, and her relationship with her daughter was “fractious,” added Spiegelman. The family moved around a lot, often living in wealthy, manicured suburbs, which left Colwin feeling suffocated. She became allergic to all forms of pretension, dropped out of college after two years, and set up in a tiny studio apartment with no kitchen sink in Manhattan’s West Village, determined to chart her own course.

My gingerbread cake calls for adding the flour mixture to the wet ingredients—the last step before putting it in the oven and hoping the baking soda reaction doesn’t cause a volcanic overflow. Photograph by Erica Maclean.

Colwin’s food writing was an even more overt way of distinguishing herself from her mother than her fiction was. Her tiny studio apartment features prominently in Home Cooking. She writes about making veal scallops or an ill-fated pot roast for her guests (she could fit three but no more in her apartment) and then washing the dishes in the bathtub afterwards, or serving her home-cooked meals on a folding leatherette card table scarred by a cigarette burn—about as far from white tablecloths and crystal in the suburbs as one could get. The joy of food, and eating food together, Colwin insisted, could be almost entirely separate from status and even one’s material circumstances. Legions of fans have stepped into the kitchen after her, responding to her warmth and approachability.

Wrap the springform pan in tin foil and bake on a baking sheet to prevent overflows. Photograph by Erica Maclean.

I recognize some things about Colwin’s attitude toward cooking. One memory of my childhood is of a special pillow my mother sewed, green, with frogs and stripes, for me to sit on, on the counter, while she baked. This was in a tiny house with a huge yard in Mableton, Georgia, a modest suburb of Atlanta. My mother would talk to me while I sat on the counter, and allow me to taste the cookie batter in its various stages: finished was best, but the curdled step after the eggs went in had a certain intensity. In the late afternoons after baking, if we had time before my father came home from work, she would take me out walking between the towering rows of her vegetable garden and tell me stories: thrilling, terrible stories that starred a larger-than-life villain—her abusive alcoholic father, a big man in a small town in rural Pennsylvania, who beat his children with his belt and punched them with a fist that wore a flesh-cutting class ring. These stories were full of cool fifties cars with custom paint jobs. But when her father came home drunk to beat her mother, she would step in, bait him, draw him off, and bring him onto herself. Her mother was occasionally hospitalized. My mother was—and still is—enormously fiery and brave.

She was also averse to convention. She cooked when she wanted to, cleaned when she had to, made elaborate Halloween costumes, threw crazy kid parties, sold tile murals from a kiln in our backyard. She didn’t want to do anything everyone else was doing; she scorned it. If I told her about my longing for life to look like the happy parts of a Laurie Colwin novel, she’d say, What bullshit, and, Oh please. As a daughter responding to her mother’s character, I—naturally—love it when things are orderly, do serve dinner with crystal, and yearn for the kind of romanticized, conventional, generationally intact family that exists as the ideal in Laurie Colwin novels, even if the real picture is more complicated. I think caring what people think is fine, and even nice, part of living in a shared society. And it’s funny to me how much of my staking-out of my own ground has occurred in the kitchen. I don’t know if daughters always attempt to distinguish themselves from their mothers through their kitchen habits, but I have.

My finished cake is rich, sticky, moist, chewy gingerbread perfection, and has a slightly crunchy top. Photograph by Erica Maclean.

A well-loved recipe from Home Cooking that RF Jurjevics mentions to me is a gingerbread cake with chocolate icing, which Colwin originally made using the tiny baking trays from a toy kitchen of Jurjevics’s childhood. Later, the writer said it was her favorite cake to make for her own birthday. I have a favorite gingerbread cake of my own; in fact, one of the ways I rewrite my unconventional childhood is by having traditional meals—my tart crust, my salad dressing, my hors d’oeuvres strategy (chips! It’s easy, and I think getting people drunk early makes for a better party). I like to imagine, probably delusionally, that people expect these things from me, and that they feel they’re participating in a kind of social order when they come to my house and encounter my elaborately plated dinners and seating cards. I was eager to try my gingerbread cake recipe against Colwin’s, and even a little nervous: it felt like competing with a giant.

Colwin’s batter started out with the butter and sugar creamed together, and was thicker. Photograph by Erica Maclean.

The two cake recipes are very different. Colwin’s is more like a conventional cake. She calls for butter creamed with brown sugar, followed by a specialty ingredient—Steen’s 100 Percent Pure Cane Syrup—and relies on a heaping tablespoon of ginger powder, plus allspice, cinnamon, and clove for the gingerbread flavor. Mine uses Grandma’s Molasses, but calls for some specialty ingredients in the flavoring—an extra-strong ginger root powder I bought at an Indian grocer, plus Chinese cinnamon. I also add pureed ginger root, which really gives a spicy, fresh kick, and use olive oil instead of butter, which creates a deep, sticky, moist texture. My batter is nearly liquid and my cake cooks for an hour. Colwin’s batter is thick, and her cake can take as little as twenty minutes in the oven.

Colwin’s classic gingerbread cake from Home Cooking asks for chocolate frosting, a strange combination that I liked, though not all tasters agree. Photograph by Erica Maclean.

Both cakes were good, but, and I say this with little pleasure, four out of four tasters preferred mine in texture, moistness, and flavor. Having tried several of Colwin’s recipes, I often find them too approachable, even with the occasional niche ingredient like the Steen’s cane syrup to glam things up. (Cane syrup is made from raw pressed cane juice and has a lighter and more delicate flavor than molasses.) Colwin’s style was different from my version of today’s elaborate DIY home cooking, which is generally more laborious but can often be rewarding. My recipe has many more ingredients and steps than hers does, and even requires that the springform pan be wrapped in tinfoil to prevent overflow during the volcanic baking soda reaction that occurs when the batter hits the hot oven.

Dueling specialty ingredients: Steen’s 100 Percent Pure Cane Syrup, which is much milder than molasses; my extremely powerful ginger root powder. Photograph by Erica Maclean.

Polly Solo-Miller Demarest, according to the man she is having the affair with, is “the truest, safest, and most loving person he had ever known.” She may hail from an upper-crust Manhattan setting where the Solo-Millers “dress” for their weekly Sunday breakfast—an environment at times stultifying and intoxicating in its ideal. But Colwin knew that the warmth was the essential part, and it was with this that she approached her kitchen and invited others in. I hope I’m doing the same—plus starched napkins, seating cards, and fancy gingerbread. And if I’m not, my daughter will tell you about it in twenty years.

Laurie Colwin’s Gingerbread with Chocolate Icing

For the gingerbread:

1. Cream one stick of sweet butter with ½ cup light or dark brown sugar. Beat until fluffy and add ½ cup molasses.

2. Beat in two eggs.

3. Add 1 ½ cups of flour, ½ teaspoon of baking soda, and one very generous tablespoon of ground ginger (this can be adjusted to taste, but I like it very gingery). Add one teaspoon of cinnamon, ¼ teaspoon of ground cloves, and ¼ teaspoon of ground allspice.

4. Add two teaspoons of lemon brandy. If you don’t have any, use plain vanilla extract. Lemon extract will not do. Then add ½ cup of buttermilk (or milk with a little yogurt beaten into it) and turn batter into a buttered tin.

5. Bake at 350°F for between twenty and thirty minutes (check after twenty minutes have passed). Test with a broom straw, and cool on a rack.

For the chocolate icing:

1. Cream ½ stick of sweet butter. When fluffy add four tablespoons of unsweetened cocoa.

2. If you have some, add one teaspoon of vanilla brandy (easily made by steeping a couple of cut-up vanilla beans in brandy—another excellent thing to have around), or plain vanilla or plain brandy. Then add about a cup of powdered sugar, a little at a time until you get the consistency you want.

—From Home Cooking by Laurie Colwin

Photograph by Erica Maclean.

Spicy Gingerbread Cake

1 cup boiling water

¾ cup chopped, peeled ginger root

1 cup sugar

1 cup good flavored olive oil

1 cup molasses

2 tsp baking soda

½ tsp salt

2 large eggs, at room temperature

2 cups flour

1 tsp ground cinnamon (or Chinese cinnamon)

½ tsp ground allspice

½ tsp ground cloves

Pinch of ground nutmeg

Pinch of black pepper

Whipped cream to top

Preheat oven to 350°F. Line bottom of a nine-inch springform pan with parchment paper. Grease the paper and the sides with butter. Tightly wrap the outer sides and bottom of the pan in a double layer of aluminum foil, and place on a rimmed baking sheet.