The Paris Review's Blog, page 18

November 22, 2024

Mallarmé’s Poetry of the Void

Édouard Manet, frontispiece for L’Après-midi d’un faune. Public domain.

The following is drawn from one of three texts accompanying Florian Hecker’s Resynthese FAVN, a ten-CD box set to be released by Blank Forms in December. Hecker’s work points back to Stéphane Mallarmé’s 1876 poem L’Après-midi d’un faune—and its subsequent musical and choreographic interpretations by Claude Debussy and Vaslav Nijinsky—in which a faun, straddling reverie and reality, recounts a sensuous meeting with several nymphs. It is unclear whether the experience was an illusion; asks the faun, “Did I love a dream?” Hecker, in turn, asks listeners to examine their own sensory perceptions, destabilizing the language of Robin Mackay’s libretto within the hallucinatory textures of his composition. This text, adapted from Meillassoux’s essay “The Faun, Hero of a Dyad,” translated by Maya B. Kronic, is a close reading of Mallarmé’s rhymes.

What L’Après-midi d’un faune presents is a fully developed form of the poetic art: a form that resulted from Mallarmé’s discovery of the “Void” ten years earlier, as he put it in a 1866 letter to his friend the poet and physician Henri Cazalis. The tension inherent to his project from the moment of this “negative revelation” stems from the fact that it is combined with a refusal to renounce the vaulting ambitions of early Romanticism. Victor Hugo and Alphonse de Lamartine assigned to poetry the unprecedented task, following the example of the Psalms, of configuring a new religion to succeed an outdated Catholicism: a religion of modern man, heir to the universalist rupture of the French Revolution. Mallarmé never renounced this ambition, as can be seen in his Le Livre (probably written between 1888 and 1895), in which his own poetry becomes the centerpiece of a future ritual that resembles a kind of civic Mass.

But Romanticism had staked its legitimacy upon the poet’s divine inspiration; how could Mallarmé uphold its ambitions when his art was based on a Void, on primordial nonmeaning, on the eternal absence of any divine referent capable of sanctioning the superior meaning of his verse? In his unfinished tale Igitur ou la folie d’Elbehnon, written in 1869, Mallarmé tackles this question for the first time, in a dramatic and particularly sombre way. In Igitur, the Void is said to be “infinite,” but in a malign sense: it levels all attempts at poetry, whether successful or mediocre, since it renders all of them equally futile. This situation comes about when Igitur descends into the vaults of his ancestors as an “absolute,” i.e., convinced, like the Romantic poets in whose lineage he follows, that poetry is either absolute or it is nothing—and that in the latter case it is merely an elevated form of entertainment. It therefore apparently makes no difference whether or not he rolls the dice—the symbol of the poetic gesture in this tale—whatever the outcome of the dice roll might be. The results may certainly differ in terms of aesthetic value—after all, a perfect line of poetry is not just any line—but there is no longer any difference in terms of their claim to absoluteness: even the most perfect of lines betokens nothing other than its chance origin, which harbors no inherent destiny. Hence Igitur’s hesitation as to whether to repeat his gesture, and Mallarmé’s own hesitation about the ending he should choose for his fable: in one ending Igitur rolls the dice and gets a twelve (the number of the alexandrine, symbol of perfect verse), a result greeted by the furious hissing of his ancestors (hostile to the perpetuation of their art in the name of the Void alone); in the other he shakes the dice in his hand only to lie down upon the tomb of his ancestors—signaling his renunciation of writing.

Igitur thus constitutes an initial failure in the attempt to construct a coherent poetics of the Void capable of overcoming its nihilistic threat. Faune, on the other hand—not the aborted theatrical version of 1865 but the poetic version of 1876—will represent a significant breakthrough in this regard. It will be a matter of responding to this challenge by placing poetic writing in relation to its now undecidable nature: poetry must henceforth proceed from the poet’s very uncertainty about the absoluteness of his art. Instead of arguing, as in Igitur, that the infinity of the Void derives from the equal futility of all available options, Mallarmé will try to show that the fecundity of the Void owes to the fact that it induces inescapable doubt, and that poetry can be born of the new rhapsodist’s perpetual enquiry into whether his act is capable of laying a new foundation—something of which he will never be sure.

How is this shift possible? The Void is the nonbeing of any originary Meaning. And yet we participate in this Void through significations: these give rise to fictions (unicorns, mermaids, the “nixies” so dear to Mallarmé), which express our longings for that which is not of this world. But there is nothing beyond the world—unless perhaps the very nothing of which fictions speak. Are fictions pure chimeras, or do they indicate our ability to resist complete reduction to what Mallarmé calls “merely empty forms of matter”? This point is undecidable: the Void is nothing, but the Void also designates our capacity to aspire to that which, being nothing, exceeds the real in which everything comes down to being. Hesitation now begins to mean something different: Igitur had hesitated because the two options before him (writing for nothing, no longer writing) were equally futile. His hesitation had no value in itself: it was merely a failure to decide, an inability to choose because of the equally disastrous nature of both options. The Faun, on the other hand, makes of hesitation the very locus of a new poetry. The poetic absolute becomes the always incomplete art of the contrary hypotheses that poetry generates about its potential greatness and its potential nullity—about whether or not the Void can lead us out of the world toward the nothing to which it has been reduced. Having ceased to pledge itself to the infinite being of God, Poetry is not consequently doomed to collapse into the nonbeing of the Void: between being and nonbeing there is the peut-être, the “perhaps.”

Not even the greatest aesthetic success, therefore, can guarantee that a poem will be (absolute) Poetry—but neither can any success entirely dismiss the possibility that it might be destined for something greater than the mere metrical beauty of its verses. To produce a Poetry of the Void, then, is to describe the poet’s relationship with the ambiguous being of his song: has it taken place, is it still something that elevates us and raises us above our condition, or is it merely a pleasant diversion? This is no longer a poem of elevation (Hugolian, Promethean) or one of the fall (Baudelairian, Icarian), but one of conjuncture and conjecture. Conjuncture: a verse has in fact taken place, with all the hallmarks of success. Conjecture: Is it a bearer of absolutes, or merely a sign of the mastery of a given procedure?

This song of uncertainty is not, however, a poetics of anxiety or torment, for that would sound resonances with the all-too-familiar song to a God sensed in moments of ecstasy—without ever gaining any assurance of his existence in the throes of such ecstasy. No, it is a poetics of enquiry which constructs a network of possibilities that are patiently explored, to the point of forming a labyrinth that will reconcile the poem with its own verses. It involves the construction of a definitive alternative which however cannot be said to lack an answer to be sought within its two terms, because nothing can be superior to it. The Void is the infinity that fuels the obstinate exploration of a continually preserved possibility: always, something may have taken place.

The hypothetical encounter between the Faun and the naiads therefore stands as a figure for the experiment that the poet makes with his verse, with no guarantee of success: Did Poetry take place? From now on, the poet must doubt not God, but the status of his own writing.

However, we need to demonstrate what it is that leads us to believe that the Faun, through the intermediary of the two nymphs, is indeed addressing the verses that the poet has just written. To do so, we shall seek to establish the following thesis: the duo of naiads symbolizes the duo of rhymed verses. Rhyme, insofar as it may have taken place—but may not have, except in a banally aesthetic way—this is what we believe the whole of Mallarmé’s Faune addresses, with rhyme standing as a symbol for poetry itself.

***

In June 1865, Mallarmé announced to Henri Cazalis that he was “rhyming a heroic interlude, whose hero is a Faun.” At that point the poem was intended for the theater, even though Mallarmé was already aware that it was probably unsuited to any traditional kind of performance: ‘This poem contains a most lofty and beautiful idea, but the verses are terribly difficult to do, because I am making it absolutely scenic—it is not a work that may conceivably be given in the theater; it demands the theater.” In September of the same year, he went up to Paris to submit a first version of his text—”Monologue d’un faune”—to the Théâtre-Français; Banville and Coquelin rejected the play, for lack, they said, of the “necessary anecdote.” This “heroic interlude” contained at least three scenes, of which we have today a late copy: “Monologue of a Faun” from 1873–1874, fragments of a “Dialogue of the Nymphs” (Iane and Ianthé), and an “Awakening of the Faun.”

In a letter to Cazalis on April 28, 1866, Mallarmé announced that he would get back to writing the poem over the summer. However, there is no further mention of Faune in his correspondence in the ensuing years, and the project seems to have been abandoned until 1875. In that year Mallarmé resumed work on the Faun’s monologue alone, which, under the title “Improvisations d’un faune”—now a poem rather than a stage play, as the disappearance of all the stage directions attests—was sent in June to the publisher Alphonse Lemerre for the third issue of Parnasse contemporain. The poem was rejected by the selection committee, but Mallarmé had it published the following year—in April 1876—in a further modified form, under its definitive title L’Après-midi d’un faune, in a deluxe edition illustrated by Manet.

There are three versions of the scene of the Faun, then, only the last of which was published during the author’s lifetime: “Monologue d’un faune” (1865), “Improvisations d’un faune” (1875), and L’Après-midi d’un faune (1876). What are the most significant changes from one version to the next?

The poem depicts the meditations of a Faun, who, upon awakening, believes—but cannot be sure—that he has enjoyed a romp with two nymphs whom he managed to briefly seize hold of before they escaped him. The entire monologue consists of the various hypotheses advanced by the Faun in order to decide upon the reality of this encounter. In the 1865 version, the Faun discovers the truth of the erotic tryst by means of a “female bite” on his breast: a truth which, had the play been completed, would have been confirmed by a dialogue between the escaped naiads. In the poems of 1875 and 1876, on the other hand, the Faun is no more able than the reader to determine whether the encounter was real or fantasized. The principal change between these last two versions concerns the first line. The 1875 “Monologue” began with:

Ces nymphes, je les veux émerveiller

(These nymphs, I would enthrall them)

In this case, then, the Faun—with his flute—is still singing a song of seduction to the nymphs, and the nymphs in their reality are the principal object of his desire. The 1876 poem, on the other hand, begins as follows:

Ces nymphes, je les veux perpétuer

(These nymphs, I would perpetuate them)

In this version, the aim of the song is to prolong the dreamlike feeling with which the Satyr is still imbued when he awakens—to the point of using poetry alone to compensate for the absence of the nymphs, whose reality, in the end, no longer matters.

As early as 1865, the poet had sought to exhibit the essential principles of his writing by way of the relation that the Faun sets up between his fantasy, the existence of the naiads, and the “twin reed” (his flute) through which he expresses, musically, the essence of his desire. So there can be no doubt about the reflexive dimension of the eclogue. Indeed, such reflexivity is the commonplace par excellence of commentaries on Mallarmé. Paradoxically, however, we have perhaps not yet done justice to the degree of reflexivity of this writing, which in its detail sometimes goes far beyond what is usually admitted. Lucidity sometimes arrives belatedly: it is now, wearied as we are of essays on the autotelic nature of Mallarmé’s work, that we shall have to discover what we think we know all too well, by demonstrating that we still have not realized the extent to which the Mallarméan poem refers only to itself, and the great originality with which it does so.

Commentators have generally accepted that Faune underwent a decisive change at the moment at which the nymphs, now entirely hypothetical, began to symbolize Mallarmé’s rejection of a poetry subservient to the description of objects, in favor of an art capable of perpetuating an impression in its own right—an impression whose reality becomes irrelevant once the poet begins to focus solely upon the power of his idealized fantasy. The naiads, then, symbolize the nature with which this now autonomous art of the Satyr has ceased to concern itself. But we must go further than this. This interpretation identifies the nymphs with reality, while the Satyr would be at the level of the aesthetic reworking or replacement of this reality. Yet this approach fails to observe a quite obvious point: nymphs were already a privileged symbol of poetic fiction in Mallarmé’s work. In this poem, then, Mallarmé is not talking about a material, natural event distanced from us by a fleeting mode of appearance that renders it uncertain: he is evoking creatures that are already fictional, to which he adds undecidability. What is striking, then, is the doubling of fictionality implied by the Faun’s relation to the hypothetical naiads: it may be that a fiction has taken place, but nothing remains to attest to it. Or, even more remarkably: a being who is already quite obviously fictional—the Faun—wonders whether the fictions he has encountered—the nymphs—are not dreams of fictions, fictions dreamt up by a fiction—chimeras to the power of two … One could hardly diminish the object any further without its disappearing altogether. But then what is supposed to be designated by these naiads—these doubled phantasms which we may doubt were even so much as fictions?

It is their duality that points us in the right direction: the nymphs are desired and interrogated by the Faun always in terms of the sapphic relation that is the subtext to their insistent pairing. We should therefore see in them a transparent allusion to rhyme—and more specifically to feminine rhyme, which in French has the advantage of being both sonorous and visual (via the silent e), and thus of being grounded in the written word as well as in oral speech. A rhyme is a pair of lines eternally joined by the affinity between their conclusions, yet eternally separated by the white space between them. Union and separation, a love without fusion which compensates for the “harm of being two” specific to modern poetry, so unlike ancient poetry whose verses are single and find in themselves alone the principle of their unity. Verse is therefore Fiction, since it subjects things to the principle of the sonorous approximation of words which, entirely conventionally, designate them. The question posed by Faune therefore consists in determining whether or not there is any reliable criterion for recognizing when a rhyme is truly poetic. Did rhyme take place—or was there just a hollow assonance, a homophony that imagined it was a distich, a vain dream of poetry? Was there Fiction, i.e., the power of Verse freed from the shackles of reference so as to transport the Self into the absolute Void by means of pure chimeras? Or was there only a phantasm of Fiction—a phantasm of Verse, of Rhyme, of Poetry? The essential difference, as we have seen, is that the 1875 and 1876 versions—unlike the 1865 version—refuse to reassure the poet that his intuition of Beauty did in fact take place. Literature thus enters into a relationship of undecidability with what constitutes its essence, symbolized no longer by Woman as Muse, but by Women Intertwined around the void of their reciprocal chasm.

Quentin Meillassoux is a professor of philosophy and the author of After Finitude: An Essay on the Necessity of Contingency and The Number and the Siren: A Decipherment of Mallarme’s Coup De Des, among other books.

Maya B. Kronic is the author, most recently, of Cute Accelerationism and Head of Research and Development at the publisher Urbanomic, which aims to engender interdisciplinary thinking and production. Their essay “Return of the Faun (Formulations)” examines the afterlife of Mallarmé’s poem in the context of Hecker’s FAVN.

November 21, 2024

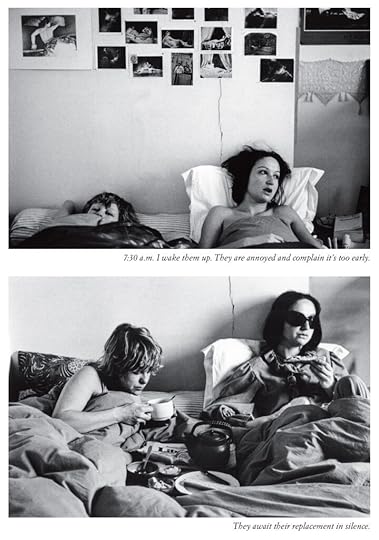

Sixth and Seventh Sleepers: Graziella Rampacci and Françoise Jourdan-Gassin

In one of Sophie Calle’s first artistic experiments, she invited twenty-seven friends, acquaintances, and strangers to sleep in her bed. She photographed them awake and asleep, secretly recording any private conversation once the door closed. She served each a meal, and, if they agreed, subjected them to a questionnaire that probed their personal predilections, habits, and dreams. The following text is Calle’s narrative report of her sixth and seventh guests’ stay, and is the fourth and final in a series of excerpts from the project to be published this week on the Daily. Previous installments: “Third Sleeper,” “Fourth Sleeper,” and “Fifth Sleeper.”

I do not know Graziella Rampacci. Françoise Jourdan-Gassin gave me her telephone number. She immediately agrees to sleep without asking for any more details. She will come Tuesday, April 3, from midnight to 8 A.M.

I know Françoise Jourdan-Gassin. She had declined to participate. She simply came to accompany Graziella Rampacci whom she’d recommended I invite. She decides at the last minute to share the night with her friend.

Tuesday, April 3, at midnight, they take over for Gérard Maillet. Françoise says to Graziella, “What if I slept with you?”

G: Oh! That would be wonderful!

F: Are you inviting me?

G: I’m inviting you. This will be my first time sleeping with you. Bizarre, considering how long we’ve known each other.

F: To know someone for eight years and never sleep together.

G: I’ve wanted to for so long, Françoise.

Then we leave the bedroom. They wait for Gérard to come out, dressed in my father’s robe, before they get settled. They change the sheets. Graziella brought red pajamas with a jabot collar. I serve them a glass of champagne. I leave.

Listening to the tape, I hear:

F: A nice welcome!

G: This will be great!

F: Can I air out the bedroom? It smells like sweat!

I understand from the sounds and silences that they’re moving between the bathroom and the bedroom. The bed must be empty.

G: Do you like my pajamas?

F (with a whistle of admiration): You don’t sleep in just anything!

I enter. Graziella asks for sunglasses. I propose they answer a few questions.

Names, ages, professions?

“My name is Graziella Rampacci. I’m twenty-seven years old. I was born in Nice. I make dresses. I like to read, I like to come here, I like to act. It would be better if I slept less—I could read more.”

“My name is Françoise Jourdan-Gassin. I’m a painter. Twenty-five years old.”

Do they have any requirements at night?

F: Just a clean bed.

Françoise is a light sleeper, Graziella is a heavy sleeper.

Françoise talks in her sleep, Graziella doesn’t talk.

What they have in common: Sleep is a source of pleasure for them both. They can sleep while a stranger watches, in a bed situated in the middle of the room. They are disgusted by the idea of sleeping in sheets used by someone else. They like to sleep alone. Graziella can’t stand it when a partner jumps her as soon as they get into bed.

Françoise is faithful to her bed. Graziella sleeps anywhere, anytime. When she agreed to come sleep here, she thought that the experience would last eight days, eight days in the bed.

I leave the room for a brief moment.

Listening to the tape, I hear:

G: I love this questionnaire.

F (in a whisper): I’m going to tell you something—

She must have noticed that the recorder was on because she goes quiet. Gérard enters. He’s looking for his boots. He asks the two women whether he’s disturbing them. They say no, not at all. He would like to witness the interview, without saying anything. They answer that they have nothing to hide. I return.

Have they ever participated in a similar experiment?

F: No.

G: I’ve slept in strangers’ homes. Apart from the structure, the feeling is the same.

Do they consider the act of sleeping a job?

F: Yes, I promised. I have to do it. It’s a job.

G: What we’re doing tonight, I find it enjoyable, so it’s more like a game.

Do they consider it an artistic act?

G: No.

F: Yes.

Can they recount some memories of sleep?

Graziella tells me about a nightmare from five or six years ago. She was surrounded by her father, her mother, her sister. Spiders with human heads sat on her shoulder. They spoke in her ear. A language of onomatopoeias. Their heads were big on one side, flattened on the other. This nightmare never recurred, but it haunts her. Then she tells me about a dream. A boy she knows undressed then removed his skin. Inside, there was fire.

What do they think of their predecessor? (He leaves in a hurry.)

F: I find him charming.

G: I don’t think anything. (He returns.)

What are their motives for agreeing to come?

G: I like to meet new people. I’ll gladly leave the house for that.

F: At first, I didn’t want to. I changed my mind, for no real reason, on the way. I was here; it was easy.

They don’t regret coming. They are happy to be together. For their breakfast, they want tea and toast.

At two in the morning, Gérard takes his leave. I photograph them during the night at regular intervals. Graziella changes position each time I take a photo but doesn’t open her eyes. Françoise is nestled at the end of the bed, in darkness.

7:30 A.M. I wake them up. I bring them breakfast. They complain—it’s too early. They would like to listen to Bizet’s Carmen. They are silent.

At eight, they welcome Henri-Alexis Baatsch, in charge of the next shift. Graziella doesn’t know him; Françoise had already met him. After brief introductions, he leaves the bedroom so they can get up. They take a bath before they go. At 8:30 A.M., I walk them to the door. I thank them for coming to sleep.

From The Sleepers , to be published Siglio Press in December. Translated from the French by Emma Ramadan.

Sophie Calle is an artist, writer, photographer, filmmaker, and performer whose work often makes use of Oulipian constraints. A retrospective of her work, Overshare, is currently on view at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis, Minnesota.

Emma Ramadan is an educator and literary translator from French. She was awarded the PEN Translation Prize for her translation of Abdellah Taïa’s A Country for Dying, and has received the Albertine Prize, two NEA Fellowships, and a Fulbright. Her translations include Anne Garréta’s Sphinx, Barbara Molinard’s Panics, and Marguerite Duras’s Me & Other Writing.

November 20, 2024

Fifth Sleeper: Gérard Maillet

In one of Sophie Calle’s first artistic experiments, she invited twenty-seven friends, acquaintances, and strangers to sleep in her bed. She photographed them awake and asleep, secretly recording any private conversation once the door closed. She served each a meal and, if they agreed, subjected them to a questionnaire that probed their personal predilections, habits, and dreams. The following text is Calle’s narrative report of her fifth guest’s stay, and is the third in a series of four excerpts from the project to be published this week on the Daily. Earlier installments: “Third Sleeper” and “Fourth Sleeper.”

I barely know him. We saw each other, one time, several years ago now, at the home of a mutual friend. That friend told him about my idea. Gérard Maillet calls me to offer his services. He wants to be paid—a symbolic sum. He says he’s unemployed, that any time works for him. He’ll sleep Monday, April 2, from 5 P.M. to midnight.

He arrives Monday, April 2, at 5 P.M. He waits until Rachel Sindler has left the bedroom to get settled. I show him the set of clean sheets. I leave.

At five fifteen, I return. He’s in the bed. He hasn’t changed the sheets. His shoulders are bare. His head rests on the pillow. He asks about my use of the formal “vous.” I explain the necessity of keeping my distance from the sleepers. He tells me about his complicated relationship to work. He has a hard time accepting the idea that intellectual labor is labor. So he finds it especially interesting to be encouraged to consider sleep as a form of work. That’s why he asked to be paid. But the people he spoke to about it, who don’t share the same hangup … He doesn’t finish his sentence. He tells me about one of his friends, a Mobylette courier, who said, “If that girl has time and money to waste, there are better things to do.” He, the friend, would have organized a soup kitchen for drug addicts. Apparently that’s his obsession—soup kitchens for drug addicts. Gérard Maillet continues. Throughout his monologue, these words often recur: perversion, forbidden, superfluous, eroticism.

He comments on the bed, which is warm. On the smell of perfume.

At eighteen, he met a superb woman, a model. She lived two hundred meters from his high school. And one day he found himself in her home, in her bed. It earned him a prestigious reputation among his friends. They said, “Gérard, what a stud!”

“What actually happened is that we slept like brother and sister. I don’t know why exactly.”

I propose that Gérard Maillet answer my questionnaire.

What is his name? What is his age? Can he give me a brief description of his past?

“Gérard Maillet, twenty-six years old. I have two brothers. Until the age of eighteen, I lived in Paris, with my parents. What else can I say? Still in school. A series of odd jobs. For the last three years, contracts for sociological research.”

Gérard Maillet adds that now he has a two-bedroom apartment in the twelfth arrondissement. He calls it an upgrade.

Is sleep a source of pleasure or a waste of time for him?

“It’s a refuge, a way to regulate internal tensions. I’m a hedonist. Sleep is important to restore our health, turn the page, and—” I interrupt him.

How would he describe his sleep?

“I would say, ecological. As soon as I decide to go to bed, it happens.”

Does he need absolute darkness to fall asleep?

“It’s not a necessity, more of a habit and a form of security. The dark is—” I interrupt him.

Does he talk in his sleep?

“No, but I grind my teeth.” He tries to continue, but I cut him off once again. I want everything to move faster. It’s not information or a conversation that I’m looking for. He seems to understand. His responses become more brief.

I obtain the following information: He sleeps in the fetal position. He doesn’t have a difficult time waking up. He doesn’t like to sleep in a bed situated in the middle of a room. He can fall asleep despite noise as long as it’s regular. My presence does not risk disturbing his sleep. He does not disguise himself for sleep. The used sheets do not disgust him. He likes to sleep alone. He can’t stand sleeping with clothes on. He can undress in front of strangers. He does not pee the bed. He bathes often. He wears cologne. He doesn’t masturbate in the morning upon waking, or at night before going to sleep. He likes animals. He thinks that the same smells can be either erotic or unpleasant. His fondest nocturnal memories are not of nights sleeping. He doesn’t have noteworthy dreams to recount. For him, sleep is priceless. He wants me to wait in the room until he falls asleep.

Is he aware that he is performing a job by coming to sleep?

“I am convinced.”

Does he have the impression that he is making art?

“No. I am participating in a job. It’s not for me to say whether it’s art. The purpose is none of my business.”

What would be appropriate remuneration for his presence in this bed?

“A certificate to the effect that I performed sleep labor. Written proof that I was employed. A signature.”

Payment?

“Yes, symbolic.”

What does he think of the person who preceded him in this bed?

“It was a pleasant meeting. A positive start.”

How does he imagine the person who will replace him?

“I have very little imagination.”

6 P.M. The questionnaire is over. I thank him for responding so conscientiously. I wish him a pleasant sleep. I leave the bedroom.

Soon after, I return. He’s sleeping. I sit in an armchair that I leave only for brief moments. I remain by his side. He turns his back to me. I watch him. His presence in my bed seems in no way implausible. I hardly dare move. I watch over him. I’m not tired; it’s relaxing to watch him sleep. I photograph him every hour. At 11 P.M., I wake him up.

I place a tray of food on the floor: ham, eggs, macaroni. I return to my armchair. I call him softly. He doesn’t move. I repeat his name. He lets out a sigh, turns around. He sits up.

Me: Did you have a good night?

Him: Yes, I did my best.

Me: I was here the whole time.

Him: Good.

We speak more and more softly. Meanwhile, his meal gets cold. He asks for water and I go fetch it. I sing in the stairwell. When I return, he yawns languorously. I tell him that I listened to his breathing. He asks if he snored.

“No, you were breathing softly. I could have fallen asleep.”

He asks me not to record the rest of our conversation. I obey. He confides.

At midnight, the arrival of Graziella Rampacci, who will take the next shift, and Françoise Jourdan-Gassin, who accompanies her. Graziella goes immediately, at my request, to the bedroom occupied by Gérard Maillet. Françoise and I wait a few moments before joining her.

Listening to the tape:

Gérard yawns, stretches, coughs.

Graziella knocks three times on the door. She enters.

Her: Hello, I’m here to take your place.

Him: Very good.

He says he didn’t really have time to sleep. She pities him for having to come during the day. She wouldn’t have been able to. She adds, “Well, I was told to come in here, so that there would be contact. I’d like to know what we’re supposed to talk about, you, a stranger who’s just woken up, and me, tired from a long and difficult day.”

He thinks that the obvious common ground is the bed. Graziella admires the paintings hung on the wall. He finds the bedroom intimate enough for …

Accompanied by Françoise, I enter, after knocking. I ask whether they’ve met.

Him: I didn’t even introduce myself—Gérard.

Her: And I’m Graziella Ram-pa-cci.

I want to take a photo of Graziella and Gérard together. She asks if she should lie down. We leave the bedroom, let him get dressed.

My father’s robe has been left on an armchair. He puts it on. He goes to take a bath. Meanwhile, the two young women settle into the bed after changing the sheets.

A half-hour later, Gérard Maillet returns to say his goodbyes. He wants to stay in the bedroom while I interview them. They agree.

At two in the morning, he leaves. I walk him to the door. I don’t pay him. (I will rectify this oversight.) I thank him for granting me a few hours of his sleep.

From The Sleepers , to be published Siglio Press in December. Translated from the French by Emma Ramadan.

Sophie Calle is an artist, writer, photographer, filmmaker, and performer whose work often makes use of Oulipian constraints. A retrospective of her work, Overshare, is currently on view at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis, Minnesota.

Emma Ramadan is an educator and literary translator from French. She was awarded the PEN Translation Prize for her translation of Abdellah Taïa’s A Country for Dying, and has received the Albertine Prize, two NEA Fellowships, and a Fulbright. Her translations include Anne Garréta’s Sphinx, Barbara Molinard’s Panics, and Marguerite Duras’s Me & Other Writing.

November 19, 2024

Fourth Sleeper: Rachel Sindler

In one of Sophie Calle’s first artistic experiments, she invited twenty-seven friends, acquaintances, and strangers to sleep in her bed. She photographed them awake and asleep, secretly recording any private conversation once the door closed. She served each a meal and, if they agreed, subjected them to a questionnaire that probed their personal predilections, habits, and dreams. The following text is Calle’s narrative report of her fourth guest’s stay, and is the second in a series of four excerpts from the project to be published this week on the Daily. You can read the first installment here.

She’s my mother. I call her on the phone at 10:30 A.M. She agrees to replace Maggie X., who was supposed to arrive at ten but didn’t show up. She will sleep on Monday, April 2, from 12 P.M. to 5 P.M.

She arrives at noon. The bedroom is empty. She gets in the bed immediately. She’s naked. She doesn’t change the sheets, but she does remove the duvet cover as well as the bolster. She asks for a whiskey. She says, “If I had run a brothel, I would know interesting people—Arabs with oil wells.”

I propose that she answer a few questions.

What is her name? What is her age?

“My age? Let me think … Rachel Sindler, not quite forty-five years old.” She adds, “Make sure to write down the names and their spelling. As for their age, I know people who lie about it. Do you ask for ID?”

Can she give a brief description of her past?

“A spotless past, all honor, bravery, marriages, children, amusement, vacation, anxieties, reading, music, walks, beach, sand. That’s it.”

Is sleeping a waste of time or a source of pleasure for her?

“Sleep—pleasure, pleasure, pleasure.”

Does she consider herself a professional sleeper?

“More like a temp. I’m not a professional. I don’t sleep as much as I’d like.”

Does she follow a ritual before going to sleep?

“For a long time I wore a sleep mask. But it’s beginning to annoy me. I don’t wear it anymore. And I read the newspaper. It depends whether I go to sleep sober or inebriated. When I’m drunk, I crash. Sober, I read Le Monde. Before the end of Le Monde, it’s over, it’s done, I’m already asleep.”

Does the door need to be open or closed?

“I thought for a very long time that the door had to be closed, but now I’ve realized that it can be open.”

How would she describe her sleep?

“Light.”

Does she ever pee the bed?

“No, never. No, I have no memory of that.”

Does she have a difficult time waking up?

“Annoying, but not difficult.”

Does my presence, or being photographed, risk disturbing her sleep?

“Hard to say. No one has ever photographed me while I sleep.”

Does she ever disguise herself for sleep?

“No.”

Does she often sleep somewhere other than her own bed?

“Very rarely now.”

Is she disgusted by sleeping in sheets that have already been used?

“A little bit.”

Does she like to sleep alone?

“Yes.”

Does she have any contagious diseases?

“Uh? No … apart from syphilis, no.”

Does she bathe often?

“Ah, every day.”

Is she averse to certain smells?

“Sweat. Shit. Vomit.”

Does she masturbate? If so, at night or in the morning?

“Not right when I wake up, anyway. At night before going to sleep, but rarely.”

Does she have a fond memory of a particular night?

“No. There have been plenty of amazing nights, but one night specifically? Let’s say that the nights when I slept ten consecutive hours were fantastic.”

Does she remember her dreams?

“I never remember my dreams. Except, recently, a rather odd dream. I was on the pope’s balcony, St. Peter’s Basilica, and all the lovers I’ve had in my life were gathered on the square. And that caused a stir because best friends recognized each other. Strangers, men from completely different social backgrounds—they were all surprised to find themselves there together. They hadn’t suspected a thing. I’d been pretty sneaky. They were waiting for me to appear. I came out on the balcony and said, ‘I didn’t realize there were so many of you!’ And everyone applauded and whooped. Voilà.”

Can she tell me about a nightmare?

“I don’t know if it’s a nightmare. Falling from a cliff into the sea and descending to the bottom. I felt myself literally glide. Down to the bottom, bottom, bottom of the sea. Very anxiety-inducing and, at the same time, pretty incredible.”

What are her motives for agreeing to come sleep?

“Well, I don’t live far and I don’t have much going on.”

Has she ever participated in an experiment of this kind?

“No.”

Is she aware that this is a job?

“No.”

Does she have the impression that this is an artistic act?

“No.”

Does she imagine the person who will replace her?

“Yes, I imagine him as handsome, manly, with an enormous cock.”

How does she envisage their meeting?

“He opens the door. He sees me. He falls in love at first sight. He’s blown away.”

What reasons does she think I have for organizing this?

“Nutcase. A project that seems a priori a bit gratuitous, but which may lead to something else.”

Did she want to refuse?

“A bit.”

So why did she accept?

“I don’t live far and I don’t have much going on.”

What nice thing can I do for her?

“Buy me a pretty dress.”

I inform her that the questionnaire is over. She adds, “What did the others say?” I don’t answer.

She goes to sleep at 12:45 P.M. I photograph her regularly. She changes position often. At four thirty, I wake her up with a glass of champagne.

At five, the doorbell rings. It’s Gérard Maillet, who has arrived on time. We head to the bedroom immediately. We enter. Rachel Sindler is reading the newspaper. I tell her, “Your replacement is here.”

She gives him a very big smile.

Rachel: Hello, how are you?

Gérard: Good.

R: Ready for bed?

G: Yes, I’m ready.

R: Well, I’ll pack my bags then!

G: No need to rush.

R: Okay, I’ll get dressed. Give me two minutes. I hope you like Guerlain Shalimar.

We leave the bedroom. Rachel Sindler joins us almost immediately. They shake hands. I walk her to the door while he gets himself settled. She is clearly enchanted by her replacement: “So this is what we have to do to meet people …”

From The Sleepers , to be published Siglio Press in December. Translated from the French by Emma Ramadan.

Sophie Calle is an artist, writer, photographer, filmmaker, and performer whose work often makes use of Oulipian constraints. A retrospective of her work, Overshare, is currently on view at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis, Minnesota.

Emma Ramadan is an educator and literary translator from French. She was awarded the PEN Translation Prize for Abdellah Taïa’s A Country for Dying, and has also received the Albertine Prize, two NEA Fellowships, and a Fulbright. Her other translations include Anne Garréta’s Sphinx, Barbara Molinard’s Panics, and Marguerite Duras’s Me & Other Writing.

November 18, 2024

Third Sleeper: Bob Garison

In one of Sophie Calle’s first artistic experiments, she invited twenty-seven friends, acquaintances, and strangers to sleep in her bed. She photographed them awake and asleep, secretly recording any private conversation once the door closed. She served each a meal, and, if they agreed, subjected them to a questionnaire that probed their personal predilections, habits, and dreams. The following text is Calle’s narrative report of her third guest’s stay, and is the first in a series of four excerpts from the project to be published this week on the Daily.

I do not know him. A mutual friend gave me his contact information. I call him and tell him briefly about my project. He is hesitant. First, he wants to know if I have a bathtub. He wants to sleep ten hours, at night only. Finally, he agrees. He will come Monday, April 2, from one to ten in the morning.

Monday, April 2, Bob Garison arrives at the agreed-upon hour. After the two women who preceded him leave, he takes a seat in the dining room. He accepted the principle of the game but has difficulty submitting to the ritual. He wants to “make himself at home.” He delays the moment of getting into the bed. He says he’s in no rush.

I do not want to call into question the proceedings of the experiment, its reasons, its rules, but how can I explain the importance of this bed being continuously occupied to a man who disregards the necessity of it. I let him do as he pleases.

He decides to take a bath. He leaves his clothes on the floor. (During the night, I rummage through his pockets, for no reason, just to rummage. They are empty. Then I gather and carefully fold his clothes.)

At two in the morning, he finally gets into the bed. I propose that he answer a few questions.

Can he give me a brief description of himself?

“Okay. Robert Garison, thirty-two years old, American, trumpeter.”

Is sleeping a source of pleasure for him?

“It’s one of my primary activities.”

Does the door need to be open or closed?

“Doesn’t matter.”

Does he talk in his sleep?

“I don’t think so.”

How does he think he sleeps?

“I don’t think about it.”

Does he use an alarm?

“They should be banned.”

Does he have a difficult time waking up?

“Not difficult, but it does take me an hour or two to wake up.”

Does my presence in the room risk disturbing his sleep?

“That depends on you, if you’re noisy.”

Does my gaze risk disturbing his sleep?

“The gaze alone? No.”

Does he ever disguise himself for sleep?

“No! Why? Are there people who disguise themselves? As what?”

Has he ever participated in an experiment of this kind?

“No.”

Can he tell me a fond memory of sleep?

“No.”

Can he tell me a bad memory of sleep?

“Probably, a night when I was kept from sleeping, for example, on the overnight train to London. That train is always annoying.”

Does he dream?

“Yes, I remember my dreams as soon as I wake up but forget them for eternity if I don’t engage with them in some way after.”

Why did he agree to come?

“Curiosity. I like meeting people.”

What does he think of the people who preceded him?

“Very nice. Am I supposed to think something? Yes, they were very nice, but I don’t know why they were together. Do they normally sleep together, those two?”

He adds, “I appreciated the bath too. What bothered me was that I didn’t want to be forced to arrive at a specific time, to sleep right away. I don’t schedule my time like that. But it worked out.”

What would he like for breakfast?

“Do you have an espresso machine? No … okay, I’ll take a coffee and a pain au chocolat. Does that work?” He adds that he likes to flip through the Herald Tribune in the morning.

At 2:30 A.M., I leave him. I did not dare ask him any more intimate questions. This is my first unknown sleeper. I lack the audacity.

During the night, I photograph him several times. He moves very little. My presence does not seem to disturb him. At ten, I wake him up by taking a photo. I bring him his coffee. I forgot the pain au chocolat and disregarded the newspaper. He wants to get up immediately. He does not ask my permission. The young woman who should take over, Maggie X., does not show up, and he refuses to wait. While he is here, the bed remains unoccupied for a long time. Going forward, I’ll be more firm.

At 10:30 A.M., I walk him to the door. I thank him for coming over to sleep.

I call Maggie’s place and learn that she has just gone to bed. She must not be disturbed. I contact my mother who lives at the end of the street. She agrees to come over right away.

From The Sleepers , to be published Siglio Press in December. Translated from the French by Emma Ramadan.

Sophie Calle is an artist, writer, photographer, filmmaker, and performer whose work often makes use of Oulipian constraints. A retrospective of her work, Overshare, is currently on view at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis, Minnesota.

Emma Ramadan is an educator and a literary translator from French. She was awarded the PEN Translation Prize for Abdellah Taïa’s A Country for Dying, and has received the Albertine Prize, two NEA Fellowships, and a Fulbright. Her translations include Anne Garréta’s Sphinx, Barbara Molinard’s Panics, and Marguerite Duras’s Me & Other Writing.November 15, 2024

What I Want to Say About Owning a Truck

Photograph courtesy of J. D. Daniels.

When I was seventeen, my father put me in charge of his black Nissan Hardbody pickup. Its driver’s-side brake light got smashed when I backed into a dumpster. I sealed it with red translucent lens-repair tape. (Can you say the word translucent if you are talking about your truck?)

My truck kept me out of the car-pool game, since it really seated only two. In the summertime I was happy to drive other kids around in the back on short jaunts from party to party, but nobody was going to ride sixteen miles one way from Fern Creek to our high school downtown in the back of a truck, on the Gene Snyder Freeway and I-65.

So I spent a lot of time in the cab of the truck by myself, smoking dope and listening to this or that cassette tape. At lunchtime, I’d walk out the side door of my high school to where I’d parked on Second Street by the art school annex, and Danielle and Allison and I would cozy up in the cab of my truck and roll one and do shotguns and listen to the Breeders. Sometime in 1992, John Scofield’s Grace Under Pressure got stuck in the tape player. When it comes to being trapped in a loop, you could do worse than to spend an hour with Bill Frisell, Charlie Haden, and Joey Baron. I’ve always been lucky. Sometimes I think I’m the luckiest man who ever lived.

***

I guess I had started working for System Parking down at the hospital complex, or was I back in the decal shop at Kentucky Trailer with Knox and Bad Tom and Other Tom, or had I started driving for Ermin’s Bakery by then, or by that time had I totaled Ermin’s box truck on Hurstbourne Lane—no, because by then I would have been in the house on South Preston, between the cemetery and the White Castle on Eastern Parkway, a couple of blocks from Uncle Pleasant’s, that would have been 1998, I was twenty-four, I was married. It was 1996, and I was still living over the corner grocery store, when Jimmy and Micah wandered past in the dark.

I was drinking by the open window on a summer night, listening to nothing. Jimmy and Micah walked down the street, singing a James Brown song, I forget what it was, he had been playing down on the waterfront. I sang some of it back out the window to them. They stopped, and we talked through the window for a minute, and pretty soon I went down the fire escape with three tall cans and we drank them sitting on the broken pavement of the parking lot.

And then Jimmy said, “Is that your truck?”

When people see your truck, they tend to see what you can do for them.

***

Jimmy and Micah and I got in my truck and drove a couple of blocks over to Micah’s nearly empty apartment, chucked his couch in the back of the truck, and drove to Thirty-Eighth Street, where we parked in front of a house with five sleepy-eyed girls sitting on a long porch and we hocked Micah’s couch for crack, something I wouldn’t have believed possible if I hadn’t seen it with my own eyes. Jimmy passed me a folded piece of aluminum foil. “I’m good, man,” I said, but Jimmy said, “It’s all I’ve got to pay you for your trouble.” I put it in my freezer and went to bed. The next afternoon, Jimmy came over and bought it from me. That was how it started.

After a month or so, a guy called Carlos dropped by, calm and frank, trying to understand who I was and what was going on in the neighborhood. I remember Carlos kept talking about Master P’s Ice Cream Man. That’s how I know it had to be 1996. Carlos looked around my kitchen, opening cabinets, looking at coffee mugs. He opened the closet and looked at the litter box.

Micah was in bad shape from the start, but Jimmy was keeping it together, more or less. He would walk down Hill Street to my apartment and climb up the fire escape and knock on my door. Britt and Sean had carved a pentagram into the door with a jackknife. We’d have a couple of drinks and record some blues on my TASCAM Porta four-track. Jimmy played my sparkle-blue Aria Pro II strat copy. I had cleaned toilets in Fern Creek all summer to be able to afford that guitar. Tim, who played for Human Remains and worked at the Preston Music Center in Okolona, taught me how to tune it, but my next lesson was canceled because Tim was back in Central State after cutting open his own forearm with a carpet knife, trying to find his bionic parts. That’s enough about the guitar Jimmy was playing. I was on the Telecaster I’d bought from that big music showroom on Bardstown Road, near the Toy Tiger and Showcase Cinemas and El Caporal.

Jimmy said, “If you release these recordings while I’m in jail, when I get out I will kill you.”

“Relax,” I said. “If anyone ever releases this, I will kill myself.”

***

The last time I saw Carlos, he said, “Are you trying to tell me you’ve never had three bitches at once? Because it can be arranged.”

The last time I saw Micah, he was holding an empty silver picture frame and crying.

The last time I saw Jimmy was at a birthday party for one of my girlfriend’s coworkers who had just gotten into law school. My little apartment, with its cinder block and plank shelving, was full of girls drinking margaritas.

I opened the back door and saw Jimmy wearing a tattered straw hat and a red T-shirt with its sleeves cut off. Next to him stood a bored girl.

“Jimmy, this is not a good time.”

“Don’t you want me to get a little tail before I go back to prison? Give me twenty dollars.”

“I’m not giving you anything.”

He shrugged and took off his hat. “Buy my hat for ten dollars,” he said. “Something to remember me by.”

“You know what? I will.” I put the hat on.

My girlfriend, smiling blandly, hissed into my ear, “Get this over with.”

He took off his shirt. “Now buy this for ten dollars.”

“Fine. You good?”

“I appreciate it.”

“Sure. Good luck, Jimmy.”

Now it was almost over.

One morning not long after, there was a knock at the back door. I opened it to see a man I didn’t know wearing a dark suit.

“Can I help you?”

“I just now come from my sister’s funeral.”

“Sorry for your loss. Why are you telling me this?”

He was holding a tiny velvet box. He opened it.

“My sister’s earrings.”

“I’m glad you have something to remember her by.”

“Buy them.”

“Do what?”

“Buy them, motherfucker,” he said. “Buy my dead sister’s earrings.”

***

I don’t think I’ll ever forget Layton calling me late one night. The last time I had seen Layton, he’d been cadging drinks at the Mag Bar.

“Hey,” the bartender said to me. “You can’t buy a beer for Crazy Horse.”

“Take it easy. I grew up with this guy.”

“Maybe you grew up. He tries it in here every night. He’s got to go.”

“It’s your bar.”

“That is a fact,” he said.

“It’s all right, Long John,” Layton said. “Drive me home.”

But I didn’t drive Layton home. Instead he stumbled off, and I drank beers and played Golden Tee and shot some nine-ball with my friend Jay.

That was the last time I saw Layton. The last time I heard him was on the telephone. My girlfriend had bought an antique red wooden chair with an attached table for the phone, a kind of designated telephone chair, and her black-and-white cat had commandeered it. Her cat’s name was Delilah and she was aloof or aggressive unless the telephone rang, in which case she jumped on the chair and was sweet and wanted all your attention.

“Hey, Long John. It’s me.”

“Layton? Are you okay?”

“Sure. Do you still have your truck?”

“I sold that truck years ago.”

“You got the number of the guy you sold it to?”

I did have that number, or at least I knew where I could find it, but I wasn’t going to turn Layton loose on Thordy. That old hillbilly had enough trouble in his life. It was easy to imagine the state of my truck now that it was in Thordy’s hands, such as Thordy’s hands were. When I met Thordy, he had four fingers on his left hand and three on his right. Management put Thordy in the repair shop with my dad, because my dad’s shop had the best safety record at the plant. I was sure that my old truck, Thordy’s truck now, which I had always kept clean, almost empty, would be full of scratch-off tickets and cigarette butts that he had tumped out of an overfilled ashtray. I wonder what Thordy ever did about that Scofield and Frisell cassette. Thordy was a country-and-western man.

J. D. Daniels is the winner of a 2016 Whiting Award and The Paris Review’s 2013 Terry Southern Prize. His collection The Correspondence was published in 2017. His writing has appeared in Esquire, n+1, the Los Angeles Review of Books, and elsewhere, including The Best American Essays and The Best American Travel Writing.

November 14, 2024

“Multiple Worlds Vying to Exist”: Philip K. Dick and Palestine

Detail from the cover art of the first edition of Martian Time-Slip (1964).

1.

Imagine a present-day reader reaching for Philip K. Dick’s 1964 novel Martian Time-Slip in search of transport, out of the here and now to a psychedelically paranoid near-future Mars. This person might be disconcerted to find two characters discussing traveling to a zone called New Israel—specifically, to a Martian settlement called Camp Ben-Gurion:

As Otto and Steiner walked back to the storage shed, Steiner said, “I personally can’t stand those Israelis, even though I have to deal with them all the time. They’re unnatural, the way they live, in those barracks, and always out trying to plant orchards, oranges or lemons, you know. They have the advantage over everybody else because back Home they lived almost like we live here, with desert and hardly any resources.”

“True,” Otto said. “but you have to hand it to them; they really hustle. They’re not lazy.”

“And not only that,” Steiner said, “they’re hypocrites regarding food. Look at how many cans of nonkosher meat they buy from me. None of them keep the dietary laws.”

“Well, if you don’t approve of them buying smoked oysters from you, don’t sell to them,” Otto said.

Then, a page later:

Steiner felt guilty that he had talked badly about the Israelis. He had done it only as part of his speech designed to dissuade Otto from coming along with him, but nevertheless it was not right; it went contrary to his authentic feelings. Shame, he realized. That was why he had said it; shame because of his defective son at Camp B-G … Without the Israelis, his son would be uncared for. No other facilities for anomalous children existed on Mars …

When Dick became my chosen writer, at age fourteen, in 1978, with Martian Time-Slip, one of my two or three favorites among his novels, the presence of the Israeli settlement on Mars didn’t resound in any particular way. My initial responsiveness to Dick’s work was to delight in his mordant surrealist onslaught against the drab prison of consensual reality—he was punk rock to me. It took me a while to grasp how Dick’s novels, those of the early sixties especially, function as a superb lens for critiquing the collective psychological binds of the postwar embrace of consumer capitalism. Yet to say that he seems to devise his critiques semiconsciously, by intuition, is an understatement. Dick thought he was bashing out pulp entertainment, and he sometimes despised himself for doing it. At other times—and Martian Time-Slip was one of those times—he injected his efforts with the aspiration to raise his output to the condition of literature, employing all the thwarted ambition of a young novelist with nine or ten literary novels (or, as an SF writer would put it, “mainstream” novels) in his trunk, which his agent had been unable to place with New York publishers. Dick had an extrasensory power, however; he was a freaked-out supertaster of repressive and coercive elements lurking inside the seductive and banal surfaces of Cold War U.S. culture and politics. This meant that science fiction opened up his particular capacity for fusing ordinary experience—the emotional and ontological crises of his human characters—to the implications of the hegemonic power of the U.S., which coalesced in the period in which Dick wrote, and which defines our present century. Reality’s surface shimmers open beneath Dick’s gaze. It’s this that led Fredric Jameson to compare him to Shakespeare. This wouldn’t have happened had he stuck to the earnest social realism of his unpublished novels.

Dick’s use of the name New Israel in Martian Time-Slip is pretty stock. Dick traveled beyond North America only once, to a conference in Metz, France, where he delivered a legendary speech titled “If You Find This World Bad, You Should See Some of the Others”—baffling his French fans by opening an early window into the mystical, visionary search that would preoccupy him for the remainder of his life. Then he went home to Orange County, California. His impression of Israel may essentially be derived from Leon Uris’s Exodus, or from some other heroic fifties representation; he principally employs the Israelis in Martian Time-Slip as an anonymous and implacable counterpoint to the abject ineptitude of the U.S. colonists—to highlight the haplessness of their attempts to farm and irrigate the harsh Martian desertscape. As in the excerpt above, the Israelis present a mirror for shame. This matches, of course, a typical midcentury U.S. liberal’s reaction formation, after the discovery of the German and Polish death camps: the Jew as shame trigger, with the survivors idealized for their resilience and strength.

2.

I kept faith with Philip K. Dick through my twenties, even as I expanded my reading in contemporary fiction and, in an autodidactic fashion, began to absorb a certain amount of philosophy, criticism, and theory. The immense reward was to begin to experience Dick as not only a satirist of consumer culture and technocratic optimism—like some kind of more psychedelic version of Mad magazine—but also as a social and political novelist, and an articulate (if sometimes gnomic) diagnostician of the morbid condition of U.S. empire. I had help, of course. The Rosetta stone, for me, was Kim Stanley Robinson’s The Novels of Philip K. Dick, written as his doctoral dissertation in 1982, under the guidance of his advisor, Fredric Jameson. Through Stan’s book I was to some extent absorbing Jameson before I knew I wanted to try. (I call him Stan because he’s a friend; we first met at a bookstore in Berkeley called the Other Change of Hobbit, when I pressed a hardbound copy of the dissertation into his hands to sign.)

Later I turned directly to Jameson, who makes superb use of science fiction generally and Philip K. Dick specifically. The stakes he sets out are the largest stakes possible: “If the historical novel ‘corresponded’ to the emergence of historicity,” he writes in Postmodernism, or, The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism, “… science fiction equally corresponds to the waning or the blockage of that historicity, and, particularly in our own time (in the postmodern era), to its crisis and paralysis, its enfeeblement and repression.” I take this to suggest that Dick’s novels, which so often concern themselves with multiple or alternate future realities, are also arguments about nostalgia and trauma. The novels ostensibly concern themselves with the future, but as Dick’s readers know, they often involve attempts to reconstruct or secure some former world that has been wrenched away from the characters in some episode of traumatic rupture: an explosion, an emigration (whether voluntary or forced), a drug-induced spell of hallucination. In Jameson’s fundamentally political interpretation of Dick’s work, these are arguments about which of our multiple alternate or phantasmic “pasts” we must reject, and which we might embrace, before we can achieve a bearable present.

Of course, Philip K. Dick attracts philosophers like flies to sherbet. In my experience, this usually goes well, for both flies and sherbet. A terrific new example can be found in French philosopher David Lapoujade’s Worlds Built to Fall Apart: Versions of Philip K. Dick. Lapoujade’s reading of Philip K. Dick flows mainly through the framework of an older French philosopher, Étienne Souriau, no longer living, whose neglected writings Lapoujade has made it a mission to resurrect. Dick and Souriau seem to have been thought-cousins of a very unusual kind, though it doesn’t seem likely that Souriau would have read him. Lapoujade’s English translator, Erik Beranek, gives a nice introduction to Souriau’s thinking:

Souriau’s philosophy aims to shift the emphasis from a single, preexisting reality … For Souriau, a stone exists, a person exists, and a tree exists, but a forest exists in a manner all its own, separate from the individual trees; likewise, a fictional character like Don Quixote, the idea of a nation, and the unmade film to which an already written screenplay refers all have their distinct modes of existence. Particularly important within Souriau’s analysis of these different modes are virtual existences, which is to say incomplete existences or existences in the making that seem to call for an intensification and development of their own reality … looking at them as existences that make a claim on their own future development. As a result, he is able to push away from the traditional primacy of the already fully constituted to show a picture in which the world remains something in the making.

Beranek goes on to describe how Lapoujade pushes Souriau’s analysis into an explicitly political dimension:

Lapoujade turns his attention to those existences that find themselves dispossessed of their reality; that is, those beings that find themselves to have less reality than others who control what has been determined as most real. If existences need to make a claim on their own reality and right to exist, what happens when an existence is prevented from doing so by other forces within its world and is therefore stripped and dispossessed of the very reality to which it makes its claim?

“Others who control what has been determined as most real.” For anyone newly confronting the extent to which understanding of the history of the Palestinian people has been shaped for the American media, this phrase cannot help but burgeon with implication.

In Lapoujade’s description, the worlds Dick constructs are always on the point of collapsing, precisely because they are worlds whose appearances are determined by a clash of multiple realities—or multiple arguments about the past—vying for control.

As with much science fiction, we find stories of colonization—off-Earth colonization—throughout Dick’s writings. Often, it’s Mars, as in The Three Stigmata of Palmer Eldritch, Martian Time-Slip, Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?, and “We Can Remember It for You Wholesale.” In other novels, like The Crack in Space and The Unteleported Man, the destination is beyond the solar system.

Those stories of colonization that uncover political implications that might matter in thinking about Palestine are, of course, those in which an indigenous population exists before the arrival of Dick’s settler population. The most disturbingly relevant, by far, is Martian Time-Slip. This isn’t because of the presence of the Israeli settlement, though that does feel like a tell—a stray signifier that also functions as a kind of neon arrow directing us to pull off the road and pay attention. It’s because in this novel, the indigenous Martian population—they’re called Bleekmen—aren’t even aliens. They’re nomadic foragers capable of interactions with the settlers on a variety of human-to-human levels: linguistic, professional, and sexual. They are specifically defined as human; they arrived and naturalized to Mars at some unspecified earlier time. However, their marked cultural differences, and their deep acclimation to the conditions of Mars, allow the Earth settlers a margin for apartheid exclusion based on a muddling of the notion of the “alien” and the “human”—or, to be more precise, these qualities allow the settlers to affirm a population’s humanity while systematically violating their human rights.

The critic John Huntington wrote in Rationalizing Genius that “in popular SF, imagining the alien often consists of including or excluding it from the narrator’s sense of what is normal. There is, of course, literature in which beings somehow alien to the author—like Mrs. Moore and Dr. Aziz in A Passage to India—may develop in complex ways because their alienness is not their essence.” Martian Time-Slip conforms precisely to Huntington’s description. It more closely resembles E. M. Forster’s novel than it does a tale of alien encounter, because it isn’t one. In A Passage to India, Mrs. Moore is the white Christian woman whose certainties become cosmically rattled in the Marabar Caves incident, in which a permanently ambiguous series of events gives rise, catastrophically, to an accusation of rape. Mrs. Moore’s subsequent flights of cosmic openness to the implications of her metaphysical revelation, to oneness with the universe, are a contest between Forster’s Orientalism and his critique of the racist paternalism of the British Empire. The analogue to Mrs. Moore in Martian Time-Slip is Jack Bohlen, one of Philip K. Dick’s exemplary Everyman characters. Bohlen makes his living on Mars as a service repairman, tickling dust-choked mechanisms back to life and trying to balance the pressures of bad bosses and a stale marriage (on its “realist” side, Martian Time-Slip is a typical early-sixties novel of infidelity, not so distant from John Updike or Richard Yates) against the fact that the schizophrenic autistic-savant son of one of his neighbors (named as the “anomalous” child who is being cared for in the Israeli settlement) is causing him to hallucinate a nightmare future in which all the Earth settlements have collapsed into bleak, horrifying ruin. The boy in the book, Manfred Steiner, is like the book’s author, a canary in the coal mine, a kind of helpless supertaster of the nightmares to which the colonial project has doomed them all. The boy is also instinctive kin to the indigenous Bleekmen, with whom he shares some kind of collective psychic capacity to live outside conventional Western notions of individual consciousness, and outside of time itself.

Like the Malabar Caves, the visionary nightmares induced in Jack Bohlen by this anomalous child begin to drive him crazy—with insight. What he sees is that the U.S. colonial project on Mars, a kind of interplanetary real estate development scheme with the ominously revealing name AM-WEB (Kim Stanley Robinson translates this as “AM” for American, “WEB” for the snares of capitalism) contains its own death drive. With its prerequisite of denying the full humanity of the Bleekmen, the settlement of Mars is, ultimately, an antihuman project, full stop. Even poor Bohlen, a repairman, a tinkerer, is maintaining the status quo of the settler culture. Even a guy who just wants to mind his own business is inherently complicit.

Lapoujade: “The colonist isn’t just the person who appropriates the land and its inhabitants; she also imposes a new reality on them.”

The Israeli military hero and politician Moshe Dayan: “Jewish villages were built in the place of Arab villages. You do not even know the names of these Arab villages, and I do not blame you because geography books no longer exist, not only do the books not exist, the Arab villages are not there either. Nahalal arose in the place of Ma’alul; Kibbutz Gvat in the place of Jebata; Kibbutz Sarid in the place of Haneifs; and Kefar Yehoshua in the place of Tal al-Shuman. There is not one single place built in this country that did not have a former Arab population.”

Perhaps some among us—those who feel distant enough from the violence to slog through our days without surrendering too many of our cherished myths, without being jarred too much from our attempts to give and receive ordinary comfort to our loved ones, are somewhat like Jack Bohlen. Those of us who abreact and give our energies to protest—the students shattering the calm of our campuses, the no-fun social media friends seeding our streams with confrontational images of the carnage funded by our dollars—are the equivalent of Manfred Steiner, that helplessly visionary child who shrieks in the face of those notions we employ to sustain our complacency.

In the case of Palestine, the first necessity is to grasp the enormous ideological machine that has been necessary to blur the fact of the Nakba. The Palestinian American psychoanalyst and professor Jess Ghannam (on the Ordinary Unhappiness podcast): “We’re talking about seventy-five years of uninterrupted trauma, inherited from generation to generation, from family to family. … [The situation in Palestine] made me rethink the whole concept of trauma. … If you ask an eight-year-old child today in Gaza, ‘Where are you from, where is your family from?’ they never tell you the city that they’re currently living in—they will tell you the city that their great-grandparent was dislocated from in 1948.”

I learned the word Kristallnacht before I can remember. I was in my fifties when I first heard the word Nakba. Ideally, one goes on learning.

3.

I want to inoculate my interpretation of Martian Time-Slip against the protest that Philip K. Dick himself, had he lived long enough to learn of it, would reject it out of hand. In fact, there’s almost no question he’d have done so. Dick inherited a grain of antiacademic suspicion from the outcast milieu of SF writers that gave him his professional home and provided him with the consolation of friendships with other formidable intellects, from Robert Heinlein to Ursula K. LeGuin. He was, at times, bewilderingly wrong, allowing his own intuitions to lead him to disastrous conclusions, causing him to feud about feminism with Joanna Russ and to accuse Stanisław Lem of being an agent for the KGB. There’s a great chance that Dick, steeped in his obsession with the historic evils of the Third Reich, might never have modulated that heroic picture of the founding of Israel.

Though one is, ideally, always learning. So, who knows?

In my 1998 novel Girl in Landscape, I attempted to triangulate Martian Time-Slip with two other influences: the Westerns of John Ford, particularly The Searchers and The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, and Forster’s A Passage to India. It wasn’t that I thought I could improve on Dick’s novel, but there was something I wanted to explore in shifting his Martian frontier a few degrees closer to Ford’s settlers on the frontier, and to the British Raj. (An Anglophile reader as a kid, I’d soaked up a lot of colonial narratives: Greene, Maugham, Orwell, et cetera.) My conscious decision was to hook these materials to the archetypal science fiction vision of a frontier Mars—not only Dick’s but Ray Bradbury’s too.

So, my off-Earth colonists landed on the desert planet. Their settlement is a tenuous and fragile proposition set amid the dusty ruins of an indigenous culture which—like Ford’s Native Americans, and Forster’s Indians—remains present yet is somehow totally defined by the settlers as residual, a living relic of the past. I called them the Archbuilders.

When the book was few years old, I got a call from my agent. The French director Leos Carax was interested in making a film from the book. I’d seen two of his films and was in awe of his artistry. Carax would be in New York soon, and hoped to meet to discuss his proposition. I was given a date and time to find him for coffee at the Ace Hotel.

Here’s how I’ve always told this story previously: the morning of my meeting with Carax was a comedy of errors. Which it was, truly. I mistakenly arrived an hour early. There was a chance I’d spoiled it all right there. Carax wasn’t ready. I waited in the lobby and he emerged, grudgingly, perhaps a bit jet-lagged—in any case, not in the right mood. Yet we tried. We sat over coffee. I mistakenly thought Carax wanted me to write the film for him, which I had already told myself I didn’t want to do—or, rather, had thought I shouldn’t want to do—and before I realized I might, I’d already declared I didn’t, and annoyed him.

Here’s the part of the story I caused myself to remember by writing this: I believe now that there was another way I disappointed Leos Carax, besides obnoxiously announcing I wouldn’t write the screenplay. Carax told me he wanted to rework my story about Mars to make explicit reference to the Palestinian territory. I’ve always believed films are different from novels, and that filmmakers should feel free to transform the materials they adapt—in fact, this is one of the reasons I’d determined I shouldn’t be the screenwriter, in order that Carax not feel bound to the particulars of my novel. He should do with it whatever he wished.

Nevertheless, in mentioning Palestine, Carax surprised me. And my surprise was visible to him. And, I think, a disappointment to him.

I told him it was a great idea. Still, he’d seen my confusion. Though I’d wished to pursue the anticolonial thread running through John Ford, E. M. Forster, and Philip K. Dick, and though I’d set my fever dream in a desert landscape, I hadn’t followed my own implications to the contemporary framework that Carax felt I must obviously have had in mind. I’d only accidentally written about Palestine. For Carax, I suspect, that was unfortunate.

4.

It took me a long time to see that if Philip K. Dick was authentically of use as a political philosopher, this would be because one could discern, within his bleak diagnosis of the traumatic collapse of stable reality and the dire prospect of maintaining steady contact with the human in a world of corporate simulacra, within his fundamental (and for me, for so long, attractive and necessary) dystopianism, a grain of utopian desire. A grain of utopian belief, of utopian imperative, even. In fact, the utopian desire in Dick’s novels had been sustaining me all along, without my understanding it well enough to name it—until I came across Lapoujade and Souriau.

You may find, as I do, that you need to read Souriau quite slowly—you may also agree with me that the reward for doing so is considerable. Here is a paragraph, as translated by Beranek and Tim Howles:

It is certainly of great consequence for every one of us that we should know whether the beings we posit or suppose, that we dream up or desire, exist with the existence of dream or of reality, and of which reality; which kind of existence is prepared to receive them, such that, if present, it will maintain them, or if absent, annihilate them; or if, in wrongly considering only a single kind, vast riches of existential possibilities are left uncultivated by our thoughts and unclaimed by our lives.

Lapoujade, in more accessible language, routes such insights through Philip K. Dick, writing that, in Dick’s novels, “the world must be continuously produced.” Elsewhere, Lapoujade remarks: “Empathy is what allows one to circulate between worlds.” Here, then, may be one definition of the ineffable process Souriau calls instauration: the conscious and continuous affirmation of the plurality of existences other than our own.

To return to Jess Ghannam (again on the Ordinary Unhappiness podcast): “One of the ways in which psychoanalytic theory is so deeply powerful is that, when it’s done well, instead of being attached to a single, unconscious fantasy as the only way to have desire realized, you have opportunities to have multiple kinds of fantasies, so that … you have a more complex repertoire of opportunities to have desires realized. … Something really phenomenal will happen—not just for the psychoanalytic community for the world community, if you begin to see Palestinians and Palestinian children as human beings, as legitimate and entitled to the same kind of rights as any other human being, and entitled to the ability and the capacity to thrive and play. That’s going to help us get out of this mess. … We have to make psychic space for thinking about things in a much richer, complex, nuanced way, and if we don’t do that, we’re headed for something really horrific.”

What is Dick’s vision of utopia? What vision is possible in such a world as he and Souriau describe, this world of absolute instability among rival realities? In effect, the question contains the answer: in Dick’s novels, again and again, the veil of a unitary reality is ripped off, in favor of the revelation that we live in an existential abyss—one that is also an existential plurality. However painful the transition may feel, the true nightmare isn’t this abyss of infinite possibility but the attempted imposition upon it of a single viewpoint. Dick’s books are full of tyrannical characters, possessing nightmare capacities to infiltrate all minds to produce fascistically unified worlds. We have no choice but to overthrow them.

This essay derives its essence, though not its present form, from a talk given at the Philip K. Dick Festival in Fort Morgan, Colorado, on June 15, 2024.

Jonathan Lethem is the author of Brooklyn Crime Novel and twelve other novels. He teaches at Pomona College and lives in Los Angeles and Maine.

November 13, 2024

The Grimacer of Beaune