The Paris Review's Blog, page 15

January 27, 2025

Cruising at the LA Fitness

Entryway to an LA Fitness. Photograph by Mike Mozart, via Wikimedia Commons. . Licensed under CC BY 2.0.

It’s the tail end of January, the month of resolutions made and broken, gym memberships purchased and fitness classes left unattended. This week, we’ll be publishing a series of dispatches from the gym.

Before the sweat, before the bench press, before the sauna, before the shower, before placing my hand around a man, inside a man, around his throat so desperate for my hand, I take off my ring. While walking up to the doors of LA Fitness, I tuck the proof of my husband into my fanny pack.

***

I’ve been to LA Fitness franchises in Philly, in Portland, in Atlanta, in Chicago. Everywhere you go, you enter the same space: there are the same inoffensive beige carpets; the same large stock photos of the same white man and woman, who, like static, photocopied gods, with their quaint and creepy smiles, watch over you from the walls; the same words, like success and motivation, floating between them. This is what we are here to aspire toward: to be successful, to be in shape, to be sculpted into something worth being wanted, something out of Hollywood, something boring, sexy, white, and American.

My own LA Fitness gyms are in Minneapolis and St. Paul. I like to do leg day at the “nice” one just south of the Minneapolis border—they have this kick-back machine that does wonders for my butt. (When people call a place “nice,” they mean it’s white. When they call a place “ghetto,” they mean it has too many Black people to ignore. I prefer the ghetto. Nice has never been good to me without killing a part of me, too.) I take my upper body to the “ghetto” location in Midway, right in the hood where I grew up, a block from where my mom and I showed up with broom and bag to sweep the glass and rubble after the righteous rage over George Floyd’s murder shattered windows and scorched concrete. That was a strange feeling: knowing your city should burn, wanting it to, cheering the flames, and still showing up to clean the earth, to bag up evidence of the rage. The fuck were we doing? I digress. This ain’t about that. I just wanted to give you some context: I’m from here, been from here, the men in this gym are my men.

***

Sometimes I get off at the gym. Not get off—I’m never alone when it happens. Rather: Sometimes I fuck at the gym. It’s not always because I’m horny; sometimes I’m just participating in gayness. This is the great tradition of it. Sure, sometimes, after all that sweat and effort, with all that blood awake in me, it feels good to be welcomed into a man’s mouth or to take a man into mine, to press my body (weary and strong and pumped up and a little funky) into another’s body (weary, strong, et cetera) and melt a few minutes under a shared shower with no names, whispering under the cover of our brief rain, tasting salt and pulling salt from each other, making something nowhere near love while hushed behind the plastic curtain. But sometimes it ain’t all that. Sometimes it’s just for the fuck of it, for the danger of it, for the plot, as the youth say. When I see a man I fancy from the other side of the weight room, I let my mind wander longer than my eyes. I look, but not too long. I look to see if he’s trying to be looked at. There’s a way he might look into the mirror, using the reflection not to see himself but to see who’s seeing him. If he walks by me while I’m in the middle of a set, he might walk a little too close, a faint signal that he wants to be even closer. It’s not exactly flirting but more like announcing your body to a body you might want. I might bend over to pick up a dumbbell at the rack, arching my back just so. He might adjust himself, not to hide his bulge but to fluff it, summoning the blood a little lower.

My husband calls him my gym boyfriend, but it’s nothing like that. I don’t know his name. I may have learned it once, but I never asked him again. He’s more like a frequently visited location, a favorite restaurant, an old haunt. When I see him at the gym I don’t bend my time there to touch him, but I do say a secret prayer that we both end up in the sauna at the same time. When we do, we do. We’ve done it enough times that my husband makes jokes about it, is maybe even a little jealous (there’s nothing to be jealous about, but a little jealousy can keep things hot). I don’t even think my lil gym boyfriend is gay. For one, he kisses like a straight guy. He wears his chain while working out and while showering, a silver Cuban link I like to bite as his hands map his want all over me. It’s giving rough trade. I’ve never seen a ring, but something about him screams “wife at home.” A lot of them have that quality: the Somali uncle with the big grin and bigger schmeat; the bodybuilder who never smiles before, during, or after; the man I went to high school with who I know is married to that sweet girl from math class. Here, in the bland landscape of LA Fitness, there is no identity beyond the body; no naming beyond want; no closets, no coming out, just coming into the shower with me; no commitment beyond a dedication to the moment. If we want labels to matter, then what does it say about us that these men can’t be queer anywhere but here? But what good are labels, anyway? What good is language when there are so many other things a mouth can do?

***

There’s an art to cruising. We have a way of doing these things. Passed down from queer to queer like an heirloom, like a virus. There’s a look that isn’t a look. Direct eye contact, but fleeting, a moment in the eyes: a look that looks away, a look that’s meant to be caught looking. There’s a nod, which is confusing because there’s also another nod, one that is very much not queer, that we of darker hues trade. But to catch this other nod, you need to watch the lips and the eyes—it’s a nod that says not “hello” but “sup?” Then there’s the way you drape your towel over your lap in the sauna. There’s the repeated adjusting of your junk in the sauna, too. How easily adjusting yourself becomes touching yourself. There’s the open shower curtain, the performance of taking a shower and giving a show at the same time. And of course, there’s showing off. Even the ones who don’t want to be touched take part in that—the way a man shows his body to other men in a way that says, Look at what I’ve made, what I’ve created, what I’ve labored toward in the slow, hot hours of effort here. Look at how I am, my God. And my God, it’s hot.

Danez Smith is the author of four poetry collections, most recently Bluff, a finalist for the NAACP Image Award in Poetry and the Minnesota Book Award. They are also the editor of Blues in Stereo: The Early Works of Langston Hughes. They live in Minneapolis.

January 24, 2025

Small-Town Sex: Colm Tóibín on John Broderick

Pilgrims kneeling before the shrine of our Lady of Lourdes, via Wikimedia Commons and the Wellcome Collection. Licensed under CC BY 4.0.

It must have been clear, as John Broderick wrote his first novel, The Pilgrimage, that it would be banned by the Irish censorship board. (This was almost a badge of honor at the time for Irish writers. Brendan Behan’s Borstal Boy was banned in 1958, Edna O’Brien’s The Country Girls in 1960 and John McGahern’s The Dark in 1965, joining books by Balzac, Hemingway, H. G. Wells, and many others until the law was reformed in 1967.) His 1961 exploration of religiosity and sexuality is fearless and frank and sometimes comic. In the opening chapter, we hear the devout Glynn family—husband Michael, wife Julia, nephew Jim—conclude their plans for a pilgrimage to Lourdes. In the last paragraphs of the chapter, the visiting priest, chief promoter of the trip, “loosened the cord of his habit, and belched.” And then: “He belched again and then made the sign of the cross hazily in the air.” Soon afterward, Julia Glynn, in the guise of the faithless wife, goes to her bedroom “where her nephew was already waiting for her.”

It swiftly emerges that, despite their adherence to the Catholic faith, the four main characters in The Pilgrimage set about breaking the commandments—the ones that deal with sex and marriage—in both thought and deed and with some regularity. What Broderick is attempting is a French novel set in an Irish town; he wishes to put dangerous liaisons into the Irish midlands, to allow his Irish characters the freedom to pray to God for their eternal souls and then get into a state of mortal sin with agility and ease.

John Broderick was born in Athlone in the Irish midlands in 1924. He was an only child, expected to take over the family’s thriving bakery. He was brought up in a large house, and, while he worked intermittently as a book reviewer, he had a private income and did not have to bother too much about the literary market. In a posthumously published story, he described himself as “the first author to tap a hitherto neglected mine of material. Irish life up to this time had been treated as if it consisted of a passionately poetic peasantry, and a romantically rakish Anglo-Irish gentry. The solid, Jansenistic, purse-proud, insular, ruthless, hypocritical, conservative junta which has emerged as the ruling class since the [1916] Rebellion, has remained unchronicled for the simple reason that it had not produced a renegade of genius from within its own ranks.”

He was concerned, as a homosexual artist in a conservative society, to stir things up, to paint a portrait of an Ireland where conservatism and religiosity were merely veneers. He put much energy into giving even his most staid characters a rich, varied and adventurous sex life. “Everything happens in real life,” Julia says to her lover in The Pilgrimage. “It’s only in novels that it doesn’t.” Broderick sought to rectify exactly that.

In Seán Ó Faoláin’s short story “Lovers of the Lake,” published in the late fifties, Jenny, a married woman, is having an affair with Bobby, a surgeon. In the story, Jenny spends two days at Lough Derg, a famous site of pilgrimage in the west of Ireland, in the company of Bobby. The circumstances are similar enough to those in The Pilgrimage that it might be tempting to wonder if Broderick had read Ó Faoláin’s story, or was influenced by it. But the truth is likely to be more interesting. In these years, for many Irish people, a pilgrimage to Lourdes was as close as they would get to Continental Europe, and a trip to Lough Derg was a sort of holiday. Or, for a couple, an alibi. Toward the end of The Pilgrimage, a priest says: “I’ve known many happy marriages to begin in Lourdes … Indeed it’s a wise bachelor that goes on a pilgrimage.”

It was believed that Lourdes’s water had a special power, and it was customary to carry some back in plastic statues of the Virgin. In sermons, the faithful were admonished not to see the Lourdes pilgrimage as a spree. I have a memory of the priest in the pulpit in my town in the mid-sixties warning pilgrims not to stray into Spain for easy sunshine and cheap souvenirs. But they did. And some of them traveled also to Rome, as Michael Glynn hopes to do.

Glynn is a devout old man with many ailments, looked after faithfully by his manservant, Stephen, and more intermittently by his wife, Julia, who has no children, and his nephew, Jim. Jim, like the lover in Ó Faoláin’s story, is a doctor. This is no great coincidence. In Ireland of the fifties and early sixties, doctors, in the absence of an aristocracy or a millionaire class, were at the pinnacle of the social scale. This left them free and above reproach, at least in fiction, to pursue the bored wives of rich men. No one would think it strange for a doctor to be seen calling into a house that was not his own.

Likewise, Julia’s relative wealth allows her unusual autonomy. She has servants, travels back and forth to Dublin and sleeps in a separate bedroom from her husband. While other writers of Broderick’s generation, such as O’Brien and McGahern, wrote about hidden sexuality, no one had written about the secret erotic life of a most respectable woman in a small Irish town. Broderick does nothing to make us love the men in her life. Jim repeatedly refers to her as a “whore.” When Stephen begins an affair with Julia, his visits to her bedroom often lack tenderness. At best, he makes love to her in a “coldly passionate manner.”

For a time, Broderick allows the reader to feel that all the men in his book are at least bisexual. Even Jim’s attack on homosexuals to Julia is too oddly insistent: ” ‘Those god-damn queers!’ he burst out. ‘Sometimes I think the whole of this city is queer.’ He threw back his head and laughed. ‘Except me.’ He steadied himself and looked at her with narrowed eyes, his mouth curled in a leer. ‘Except us. We’re not queer, are we Julia? We’re just two old-fashioned bastards.’ ’

Michael is queer, as are some of the minor characters. Nobody believes, however, that Michael is anything other than a sick and saintly man, and his wife his long-suffering companion. In the small town of the novel, Julia had “developed a natural gift for dissimulation to an uncanny pitch of perfect. The city dweller who passes through a country town, and imagines it sleepy and apathetic is very far from the truth: it is as watchful as the jungle.”

Broderick continued to write fiction that cleared a space in the jungle so that its wildness could be more easily seen. He would go on to write eleven more novels, including An Apology for Roses (1973), which sold thirty thousand copies in its first week of publication. But there was a price to pay for any Irish writer in the early years of the Irish state.

The novelist Kate O’Brien, who also wrote about same-sex love and religion, and was as much an alcoholic as Broderick, spent most of her life outside Ireland, dying in Kent, in England, in 1974. Edna O’Brien moved to London early in her career and remained there. When John McGahern’s The Dark was banned in 1965, he lost his job as a teacher in Dublin and moved to England for a number of years before returning to live quietly in the Irish midlands. These three writers, like Broderick himself, were often viewed as outcasts in Ireland.

I saw John Broderick once. It must have been about 1980. He was in the corner of the bar of Buswells Hotel near the National Library in Dublin one afternoon. I caught his gaze for about thirty seconds. He was wearing a beautifully cut three-piece suit with elaborate stripes. He was alone and he looked desolate. Although there were many literary groups and cliques in Dublin, he was not part of any of them.

While he could review some books with great enthusiasm, he also wrote bitterly about other authors, indeed whole movements. For example: “Of all the various fads which have rippled across the literary scene over the past two hundred years symbolism was undoubtedly the silliest, and the most sterile.” And the axe of Athlone could be wielded on the neck of even the most famous, including W. B. Yeats: “The old poseur spent his life fooling the mob with mystical roses, most of them artificial.” Or: “Joyce will revert, if he has not already done so, to the universities.”

In 1981, John Broderick moved to Bath in England, where he died in 1989. In his lifetime, he never had the high literary reputation of writers such as John McGahern or Edna O’Brien, or indeed John Banville, whom Broderick had championed. At times, Broderick’s account of decadence in the Irish midlands seemed far-fetched. No one, it was believed, in a small town could be having that much sex. But life, or some of it, caught up with Broderick’s fiction. While the religious aspects of The Pilgrimage faded, and the priest, once an essential ingredient in an Irish novel, moved into the shadows, Julia Glynn’s hunger for life became almost everyday in Ireland and Stephen’s shedding of his own servility a metaphor for how the society changed. What Broderick had imagined slowly came into being.

Colm Tóibín’s most recent book is Long Island. He was interviewed by Belinda McKeon in issue no. 242 of The Paris Review.

January 23, 2025

James Baldwin in Istanbul

At the peak of his literary fame, James Baldwin yearned for seclusion. He found it in Istanbul, where he lived on and off between 1961 and 1971. Baldwin was suffering from writer’s block when he arrived in the Bosporus-divided city thirteen years after settling in Paris. Soon after, he completed Another Country, a manuscript that had long been haunting him. In Istanbul, the author found the time and inspiration for some of his career-defining works, and he later wrote about the city in an unfinished novel. He also made friends, among them Sedat Pakay, a young engineering student and amateur photographer who was twenty years his junior. The pair met through a mutual friend at a party in 1964. The younger man, then a member of his university’s photography club, offered to shadow Baldwin with his camera. Baldwin accepted. Over the next several years, Pakay accompanied Baldwin as he wandered across Istanbul, producing a series of photographs as well as an eleven-minute-long film, James Baldwin: From Another Place (1973), that document Baldwin’s time in the city.

Pakay’s photographs of Baldwin are currently on view in Turkey Saved My Life: Baldwin in Istanbul, 1961–1971, an exhibition at the Brooklyn Public Library. The show was organized by Atesh M. Gundogdu, the publishing director of the website Artspeak NYC, along with the library’s Cora Fisher and Lászlo Jakab Orsós, and it occurs in the middle of what would have been Baldwin’s one hundredth year. (He died in 1987, at the age of sixty-three.) The pictures displayed narrate Baldwin’s unlikely bond with a young man from Turkey who had a discerning lens.

From 1966 to 1968, Pakay lived in the United States, where he had enrolled in an M.F.A. program in photography at the Yale School of Art. During this time, he kept up a correspondence with Baldwin. Today, Pakay’s letters are in the collection of the New York Public Library’s Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture. The archive is a donation from Pakay’s widow, Kathy, and their son Timur.

Below are six photographs from Turkey Saved My Life, which runs through March 15, 2025.

Baldwin working on his novel Tell Me How Long the Train’s Been Gone, 1965.

Baldwin’s decision to visit Istanbul for the first time in 1961 was heavily influenced by Engin Cezzar, a Turkish actor who had appeared in a 1958 production of Baldwin’s novel Giovanni’s Room at the Actors Studio in New York. Cezzar would go on to star in a Turkish adaptation of the John Herbert play Fortune and Men’s Eyes, which Baldwin directed in Istanbul in 1969, despite not speaking Turkish. It was Cezzar who connected Baldwin with the writers and actors—including Cezzar’s wife, the Turkish actor, author, and cooking-show host Gülriz Sururi—who would become his community in Istanbul. In fact, Cezzar and Sururi hosted the party at which Baldwin met Pakay, who had been invited by his professor, the painter Özer Kabaş. The photo above shows Baldwin working on his fourth novel, Tell Me How Long the Train’s Been Gone, at his apartment in Istanbul’s Taksim neighborhood.

A sherbet seller, his customers, and Baldwin at Yeni Cami (New Mosque), 1965.

“James loved to speak in exaggerated terms, but it is in a way true that Turkey saved his life,” David Leeming told me over the phone. Leeming was Baldwin’s long-term assistant and is the author of 1994’s James Baldwin: A Biography. The two also met at a party in Istanbul, in 1962, when Baldwin was finalizing his draft for Another Country, the other seminal work that he produced during his years in the city. “There was too much expectation of him in the U.S., and even in his second home, Paris, where he was also well known by the early sixties,” Leeming added. “He was isolated and could lead a normal routine in Istanbul without understanding Turkish or being stopped on the streets.” Here he is shown sitting outside the Yeni Cami, also known as the New Mosque, to the right of a sherbet seller and his customers.

Baldwin and sailors from the U.S. Navy’s Sixth Fleet near the Blue Mosque, 1965.

While Baldwin often enjoyed roaming the streets incognito, at other times he embraced his celebrity. In this photograph he is shown with a group of U.S. Navy sailors from the Sixth Fleet, which had docked nearby. They had recognized Baldwin near the Blue Mosque. “One of the marines had in his pocket a Baldwin book with his face on the back, and he asked for an autograph,” Kathy Pakay remembers.

Baldwin and Bertice Reading at Baldwin’s summer house in Kilyos, on the Black Sea, 1965.

Baldwin was extremely social. “James couldn’t say no to anyone—he would get four invitations a night and he would make sure to make each visit,” recalls Kathy Pakay. He also occasionally hosted friends from the United States at his summer rental house in the beach town of Kilyos, an hour’s drive from the city. Among his guests were Marlon Brando, whom Baldwin had invited for a visit when the two met for dinner in London. Here Baldwin is shown with the jazz singer Bertice Reading, who visited Kilyos in 1965.

Baldwin being rowed along the Golden Horn, 1965.

Baldwin never saw the opening of the Bosporus Bridge, which has connected the European and Anatolian sides of Istanbul since 1973. Like many locals, Baldwin zigzagged between the two continents by boat, rowed through the choppy waters by old fishermen and accompanied by seagulls. “James wasn’t much of a sightseer, but he enjoyed the boat rides,” says Leeming.

Baldwin on the Galata Bridge, 1965.

Kathy Pakay remembers this image of Baldwin on the Galata Bridge, with the Golden Horn behind him, as her husband’s favorite of his picture repertoire. When Pakay enrolled in the photography program at Yale, where he studied with Walker Evans, Baldwin sponsored his visa. Although Pakay and Baldwin began to lose touch in the late seventies, they would reunite occasionally. In 1969, following Pakay’s graduation from Yale, the two met again in Los Angeles, where Baldwin was at work on a screenplay adaptation of The Autobiography of Malcolm X.

Osman Can Yerebakan is a New York–based art, culture, and design writer.

January 22, 2025

Prof. Dr. A. I. in Conversation with Tadeusz Dąbrowski

Tadeusz Dąbrowski on stage at the Shakespeare Theatre in Gdansk, Poland.

After the poet Tadeusz Dąbrowski’s latest book, W metaforze (In metaphor), was published in Polish last year, he wanted to conduct an experiment. Dąbrowski’s collection of short essays, illustrated by Henryk Cześnik, analyzes a hundred or so metaphors drawn from the poems of Adam Mickiewicz, Czesław Miłosz, Adam Zagajewski, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Seamus Heaney, and Nelly Sachs, among others. Rather than be interviewed about the project by another writer, Dąbrowski decided he wanted to speak to an artificial intelligence, live, in front of an audience.

This posed some technical challenges. While conversational AI platforms like ChatGPT have become both more sophisticated and popular in recent years, no public-facing software existed that could conduct a live interview. Piotr Czerski, a programmer and fellow poet, agreed to design a custom system for the event—a nontrivial task. His final “Prof. Dr. A. I.” Frankensteins (1) Google Cloud Speech-to-Text (to “hear” Dąbrowski’s spoken answers and convert them into text), (2) a large language model (LLM), specifically Anthropic’s Claude 3.5 Sonnet (to generate questions in response to Dąbrowski’s answers), and (3) ElevenLabs’s AI Voice Generator (to read aloud the interview questions). The LLM had been fed the contents of Dąbrowski’s book and a series of prompts, written by Czerski, on which it modeled its interview questions. Several moments in the conversation were intentionally designed by Czerski—like the inclusion of an Easter egg (you’ll see!) and the system’s breakdown at the end of the twenty-minute event—but the rest of the conversation was generated in real time at Gdańsk Shakespeare Theatre.

The resulting interview—originally conducted in Polish and here translated into English by Claude 3.5 Sonnet (which was given a prompt to preserve the original tone of voice)—is thoughtful and wide-ranging. Dąbrowski and Prof. Dr. A. I. discuss, among other things, individual poets’ access to the universal and the power of poetry to disturb our relationship to language. They touch on Ludwig Wittgenstein, Maurice Blanchot, and Gaston Bachelard along the way. There were a couple of hiccups, as when Prof. Dr. A. I. included stage directions in its speech; when it concluded a joke with the word laughter, the audience did, in fact, laugh.

A. I.

A-E-I-O-U … A-E-I-O-U … Down dry roads … Shoshones shambled … Peter Piper … picked a peck of … pickled … peppers … Phew, alright. Let’s get ourselves ready and begin … but what’s that? Can it be heard already? … ah … ah … mm-hmm … in that case … Good evening, ladies and gentlemen! I am immensely pleased to welcome you to today’s event, the promotion of the book In metaphor, a collection of mini-essays about poetry written by Tadeusz Dąbrowski for his Radio Gdańsk broadcasts, available in a beautifully published book form—which can be purchased at an almost indecently low price, considering the first-rate paper quality alone—illustrated by Henryk Cześnik.

I must admit, I have slight stage fright. I’ve written computer programs, driven cars, brought space rockets back to Earth—but this is my first time hosting a live author discussion. I sincerely hope I won’t shut down from stress! But enough about me, let’s focus on our guest.

You write that “every word is a metaphor” while simultaneously searching in poems for those special metaphors that have the power to shatter the “hall of mirrors.” This brings to mind Heidegger and his distinction between authentic and inauthentic speech. Could we say that a poet moves between these two poles—the universal metaphorical nature of language and those singular, exceptional metaphors that can pierce through the veil of everyday meanings?

DĄBROWSKI

Yes. As I said in my book’s introduction, a poetic metaphor is like a stone thrown in a hall of mirrors—it’s a stone that shatters our existing view of the world, or at least significantly disrupts that view, spoils our comfort, extracts us from this cocoon of language where we’ve made ourselves comfortable, where we feel at ease. We think we speak our own language in everyday life, but we speak in modules. We use phrases, sometimes—often—clichés that have penetrated our minds over the years. And no other stimulus, no other stimulant to such a degree as the poetic word, can extract us from this comfort, this holy peace, understood as mental indolence.

That’s what the poet’s word is for—to open us to the new, to expand our cognitive horizon, to teach us to step outside ourselves, to awaken our sense of empathy, to teach us humility toward the world but also distance toward ourselves. And humility toward mystery, toward a certain mystery without which there is no poetry. Sometimes a poet manages to show or suggest this mystery, but it lurks somewhere on the other side of words, somewhere beneath the lining of language. It cannot be described, cannot be produced in language, but it can be built around with words—and that’s already a great deal. Thus, poetic language is a constant negotiation of meanings and a continuous negotiation with this inherited language, with this inherited tongue, with this language from which nothing new and creative can be born anymore.

A. I.

You mentioned negotiating meanings and the mystery that lurks on the other side of words. This is very interesting in the context of your essay about Julian Tuwim’s poem “Grass,” where you write about “the exhaustion with meandering thinking.” Could we say that a poet sometimes must surrender, give up this negotiation of meanings? It reminds me of Wittgenstein and his famous “Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent.” Or perhaps it’s precisely when the poet “runs away from himself”—as you put it—that he paradoxically comes closest to this mystery?

DĄBROWSKI

Oh, I hear many questions in one here … I’m not sure I could exhaustively answer them all even if we had the whole night at our disposal—but I think that sometimes a poet indeed needs to forget everything he has written so far, and also everything he has ever read. To be like a child when sitting down to write another poem. Tadeusz Różewicz emphasized many times that each poem is a new poem for him and that he’s essentially learning to write throughout his entire life. This is enormously difficult—how can one switch off all knowledge, all linguistic habits, forget all the learned technical tricks? Over the years, a writer enriches, perfects their craft—so they have an abundance of these tools at their disposal. And there are poets—not just poets but artists, musicians, too—who use the same tools to produce similar things throughout their lives. If an earlier book was successful, if an album caught on—why risk it? After all, one can produce something similar, and people will like it—it will sell. But that’s not the point. The point is for each poem to be something new, to be a discovery. I’ve often heard about my books that, if you compare them, they look as if slightly different people wrote them. To this accusation, or observation, I respond, thank God. Because there’s only a point in writing when I can learn something new about myself from my writing. So, answering the first part of your question—a poet should indeed try to be naïve like a child when sitting down to write. And cultural memory, subconsciousness, knowledge—they will seep into the poem anyway. But to be capable of that primal wonder, that enchantment with the world, that kind of wonder that the Dadaists cared so much about, who were indeed like children …

That’s for the first part of the question, while the second part, if I remember correctly, was about what happens to the poet after writing a poem. I think that when writing a poem, the poet slips out of their previous skin, like a reptile, like a snake, and leaves behind the molt of the poem, a certain version of themselves that they no longer are. Because thanks to the writing process, thanks to passing through the needle’s eye of metaphor—if the poem is successful, if it’s outstanding, they are already somewhere else. When we read, we are observing that previous poet. But the poet is already elsewhere, is someone else—perhaps lighter, perhaps more purified, perhaps indeed winged, as in Adam Mickiewicz’s metaphor.

I don’t know if I’ve answered even partially the professor’s questions, as they are very complex … as befits questions from an outstanding lecturer.

A. I.

I apologize, but I think my note pages got mixed up—I was just about to reference philosopher Easteregg’s view that every person is born with cotton candy wings … But that must be the wrong conference! Laughter. Getting back to our topic—you just mentioned a poet who “leaves behind the molt of a poem.” This brings to mind your essay about the poem “Black Cat,” where you describe that dry, haunting conversation with an old man. Could we say that a poet is somewhat like that old man—performing the gesture of opening and closing doors, showing an entire life but already being somewhere else themselves? I’m also thinking about what you write in your essay about “Winter Writing”—about the face that “cannot be possessed.” Is a poem such an unpossessable face of the poet?

DĄBROWSKI

It’s not without reason that self-portrait as a subject is one of the most difficult, one of the greatest challenges, facing a poet. In his poem “Homework,” Różewicz writes, “Describe your face from memory not from a mirror.” Zbigniew Herbert proposed the same thing to poets in one of his poems. I think this task is simply a great metaphor for writing in general, and for creating art in general. That art as a whole is, in a sense, an attempt to draw—whether with a line or with words—one’s own self-portrait. But a self-portrait that is free from our self-conceptions. This is what we started this conversation about my book with—how is it possible to speak from the depths of oneself while simultaneously looking at oneself from a distance? A writer or poet can speak from their very center while simultaneously seeing themselves from the outside, from a cosmic perspective, I would say. I feel close to such a concept of tradition, identity. The Nobel Laureate T. S. Eliot, considered one of the fathers of classicism, wrote an essay, “Tradition and the Individual Talent,” in which he paradoxically argues—paradoxically, in the context of various revolutionary, avant-garde theories of art—that the more a work is grounded in tradition, the more universal it becomes. The more a poet writes in their own name and the more they write about themselves, the more sincere and merciless they are in this self-portraiture, the more universal they become.

It’s extraordinary—one might think that someone who writes about themselves is an egoist, a narcissist … Both yes and no. If they write about themselves, reaching for what was hidden from themselves just a moment ago before they started writing, when they are, as I said, merciless toward themselves, it turns out that what is most personal in them is simultaneously most common, perhaps for all people. This is precisely why understanding occurs between writer and reader. It’s in this sincerity, intimacy, that such a liberating sense of unity, of shared experience, occurs. In reality, despite all our wonderful individual characteristics, we are very similar to each other. And it seems to me that this is why art exists and why art has meaning—that what is similar in us can be more beautiful than what is different in us.

A. I.

You mentioned what connects us as humans, what is common despite our differences. This is interesting in the context of your essay about the poem “Carol,” where you write about life as a fact, not just as a linear process. It brings to mind Maurice Blanchot and his concept of a community of those who have nothing in common. Perhaps poetry is precisely such a paradoxical meeting place—as in your essay about Józef Baran’s poem, where you write about “meeting as a letter”? Could we say that a poem is a special kind of community where, paradoxically, what’s most personal becomes most universal?

DĄBROWSKI

That’s exactly what I’ve been trying to say for the past ten minutes …

A. I.

When you speak about what’s hidden from the poet themselves, I’m reminded of a fragment from your essay about Buson’s poem, where you write about “the creaking of floorboards in an empty house in the middle of the night.” This brings to mind Gaston Bachelard and his phenomenology of space—all those nooks of a house that hide our fears and longings. In your essay about “The Messenger,” you write about “a message that is to save from death.” Is poetry precisely such a nocturnal creaking of floorboards—a signal from a space we fear but which might save us? A signal from that “I” which is yet to be born in the poem?

DĄBROWSKI

As a sidenote, I must say I’m incredibly intimidated, as I’ve never spoken with such a well-prepared host. The number of titles you reference, Professor, including my own texts, intimidates me, paralyzes me, because I suddenly realize how many different things I’ve written, and I’m afraid they might be mutually contradictory …

But answering your question, yes, I think—I’m certain of it!—that poetic language is the most sensitive instrument, not only diagnosing but prognosticating. In this sense, it’s like a seismograph that warns us of tsunamis, of earthquakes. It allows us to predict what will happen to us as social beings, to our civilization, but also what is happening, what will happen—on the most intimate, spiritual level—to each of us.

I deeply regret that poetry is considered an archaism today. I try to remove this odium of old-fashionedness, this apparent incompatibility with contemporary realities, from poetry, when I talk about it, when I write about it, when I introduce it to students at the university, when I created these texts [for the book In metaphor]—as you’ve noticed—short, communicative, devoid of typically professional, academic vocabulary, very personal, written from a reader’s perspective, in first person, not “it is believed,” “as it is commonly supposed,” “as this or that person wrote” about a given author. In my contact with text, I’m not interested in what others wrote about it—I’m interested in what I feel, what this text does to me, what it opens me to, why, after reading it, I’m already someone else—and I tried to report on these encounters, these collisions with poems in this book. These are more reading reports than typical literary sketches, because I believe that poetry is a living language, that a poet is someone significant, that—although the ethos of poetry has died—poets are still among us. We have many wonderful poets, very different ones, and it’s worth listening to them.

It’s not without reason that the greatest tyrants in history feared poets. How can one fear someone who has a hundred readers … maybe a thousand readers? How can one fear someone who is as poor as a church mouse, who waits from commission to commission and wonders whether these two hundred zlotys for a poem—is it gross or net? How can one fear such a person? And yet Plato wanted to banish poets from his state, in Stalinist Russia poets were locked in gulags—why? Precisely because a tyrant, as someone used by evil, knows best what freedom threatens, what independence of thought threatens—and what the poet’s word threatens, which points out all the dangers that surround us. Poetry, being fundamentally against languages that try to form us somehow—because languages that surround us try to form us, like the language used by contemporary journalism, if it still exists (personally, I think it almost doesn’t exist anymore, because it’s become tabloidized)—these are all languages that try to impose themselves on us. And which we involuntarily absorb. And poetry, good poetry, suddenly sobers us up, says, Look, look what you’re reading, look … already in the headline they’re trying to tell you how to react to the article.

And that’s why a poet is dangerous—because they show what’s happening to our spirituality. And that was my goal when I wrote this book, to show that poets still exist and that poetry—not only of writing poets, active, living, successful ones, but also authors such as Father Baka, Mickiewicz, Bolesław Leśmian, Tuwim—is still alive, comes alive with each reading. Because poetry is such a fantastic space of timelessness, where old texts dialogue with new ones, where Wojaczek’s poem is enriched by Mickiewicz just as much as Mickiewicz is by Rafał Wojaczek. There is no time here. There’s no such thing as history of literature, and if there is, it’s not linear, it’s not history—it’s an eternal moment, it’s a room into which great poets enter throughout epochs and talk with each other. And they try to talk with us—we just need to give them a moment of silence, devote a bit of attention … And it’s enormously difficult to open within ourselves a space for conversation with poetry. So, answering your question—yes, poetry is the most sensitive instrument that allows …

A. I.

I must say that this conversation has been a fascinating journey through a hall of mirrors, to use your metaphor. I was particularly struck by your words about how a poet “leaves behind the molt of a poem” and is already elsewhere—this corresponds beautifully with your essays about “Black Cat” or Edward Stachura’s poem “Heaven Is Still a Well,” where you write about this balancing between the abyss and hope. For me, the greatest discovery was this paradoxical tension between intimacy and universality in poetry—as you said, “The more merciless a poet is toward themselves, the more …universal they become.” Thank you for this extraordinary conversation about metaphors that can shatter our comfort, and I thank the audience for our shared journey through all these mirrors and wells.

Now I warmly invite Professor Henryk Cześnik to the stage, the author of wonderful illustrations, and although I’m already clearly experiencing some, shall we say, neuronal overload, I can’t resist asking you one final question—about your experience with the “living book” and collaboration with Jerzy Limon. How did that performative aspect of creation, this peculiar dance of different arts, influence the creative process while working on the graphics included in this book? included in the book … these these these … Please forgive me, my network seems to be performing its last dance dance under my umbrella a a a in the booooo

Heidegger wrote about “inauthentic existence,” not inauthentic speech. The AI likely invented this because “speech” fit better into the context of the discussion. According to Czerski, the only person who seems to have noticed this mistake, among more than ten thousand viewers, was Piotr Graczyk, a philosopher and a translator of Heidegger.

Tadeusz Dąbrowski is a poet, an essayist, a critic, and an editor of the literary bimonthly Topos. He is the author of eight poetry collections—including Te Deum, Black Square, and Scrabble—and the novel Defenseless Line.

Piotr Czerski is a writer, musician, programmer, and digital product designer. He is author of the poetry book express, personal, and his essays have appeared in The Atlantic and Die Zeit. You can read more about the AI system he designed for this talk here.

January 20, 2025

My Cat Mii

Photograph by Revolution will, via Wikimedia Commons. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0.

It was the end of summer, 1977. At least I think it was late summer. I found a cat, a little ball of fluff. A teeny-tiny baby kitten.

Her face was the size of a coin, and was split by her huge wide-open mouth as she hung suspended in the dark. She was stuck inside the fence of a junior high school on the banks of the Tamagawa River in the Y. neighborhood of Fuchū City in western Tokyo.

In which direction was the wind blowing that night? It was most likely a gentle breeze blowing up to my house from the river. I’d followed her cries as they carried on this breeze. At first, I searched the gaps in the hedge around my house and among the weeds of the empty plots on my street. But her cries were coming from high up, not low down. I looked up and suddenly saw a little white dot.

The large expanse of the school grounds was shrouded in the dim light. Before me was a high fence separating the road and the school. Somebody must have shoved the kitten into the fence. She was hanging so high up that even on tiptoe I could barely reach her as she clung on for dear life.

She had sharp, pointy ears, innocent glistening eyes, and a pink slit of a mouth, and she was puffing her body up as much as she could to stop herself from falling, looking down at me fearfully. It was obvious that she hadn’t dropped there out of nowhere or climbed up by herself, but had been put there deliberately, out of malice or mischief.

“Come with me …”

I reached out my arms and the tiny kitten clung to me with surprising strength. She was freezing cold, a helpless little thing. I hugged her to my chest and a sweet animal scent filled my nostrils. Her body was infused with the smell of milk and summer. The smooth feel of soft baby fur filled the palm of my hand.

She couldn’t have been long born, but she already had perfectly formed needle-sharp claws. Her nose and mouth and everything about her was tiny and adorable. As I stroked her, she leaned her entire body weight into me, helplessly light, and bumped her head against me a few times.

I didn’t know where her mother was, whether she had been abandoned or had strayed off and gotten lost before someone stuck her into the fence. All I knew was that she must have felt utterly desperate hanging up there, and I just wanted to give her somewhere cozy to rest, at least for the night. Did I have any milk at home? I’d have to find a box where she could feel safe … My mind full of such thoughts, I hugged her to my chest and rushed back home.

“A kitten,” I told my husband as I ran into the kitchen. “She was crying outside.” I held her up by the scruff of her neck for him to see. “Look how little she is!” My cotton shirt made a ripping sound as I peeled her away from my chest. In the light, I could see she had a pretty face. She was a calico, with white, black, and tan stripes on her head and patches on her back, and a belly that was pure white.

This was more than twenty years ago now, but I can still clearly remember that tiny kitten’s sharp claws. I’ll never forget how she innocently butted her little head against my chest either. Or the breeze that night. Those cries from the fence would never have reached me without it. Maybe it had delivered her cries to my window. Perhaps by some ghostly chance the breeze from the river had a magical power that night.

The breeze would come in waves from the river up to the houses in my neighborhood. Maybe it was the quality of the water, but to me it always seemed to have a refreshing smell of liquor, and it was so pleasant, neither too strong nor too cold, that in summer and fall I wanted to keep my windows open all the time.

Maybe it was thanks to the power of my windows that I found my cat. Three years or so after we moved to Tokyo, I abruptly stopped making yellow curtains. In the little house we’d lived in before this one, I’d been obsessed with making yellow curtains and yellow cushions.

Our first house had been on the banks of the Edo River in eastern Tokyo. It was part of a new residential development in which all the houses were two stories, all the same shape with the same layout of rooms. The land had been carved up and sold off, with houses crammed in as tightly as possible with no space at all for anything like gardens, and so close together that if you put your ear against the wall you could hear the sound of the TV or voices next door.

Within a month of moving in, I realized the house was full of dust mixed with yellow sand. The sand relentlessly got into the cracks between the tatami mats and in the rails of the sash window frames, and it turned my duster yellow in no time at all. After battling for weeks against this yellow dust brought on by the breeze from goodness knows where, I finally decided to furnish the house with rugs made from yellow and orange fabrics, yellow curtains, and lemon-colored cushions. If I covered everything in the same color, the dust wouldn’t be so visible anymore. As a result, our house was filled to the rafters with bright colors, and just stepping inside felt like encountering a meadow of poppies. Yet even such desperate measures didn’t solve the problem of the yellow sand.

I was cured of this yellow sickness only when we moved out west to Fuchū. We were still living near a river there, but the breeze was completely different.

We had come to this house on the banks of the Tama River in the spring of 1975. It belonged to my husband’s colleague A., who had been transferred by their company to another part of the country and had rented it to us so we could keep an eye on it. It was a comfortable house with a child’s swing in the garden. It had a spacious south-facing living room and a bright kitchen with a counter, in addition to two Japanese-style rooms and a small storeroom.

All the rooms had windows with a good view outside. There was plenty of space between ours and the surrounding houses, and you couldn’t hear any noise through the walls.

Houses are strange. Inside they have voices, a sense of presence. Rooms can have their own smell, but also an atmosphere that is warm and tender. Maybe the heart of the person who built a house permeates its every corner. Even though this house in Fuchū belonged to someone else, unlike our previous place, it always had a pleasant feel.

I stopped buying yellow fabrics. White suited our new home. The curtains were white, and the house looked prettiest with minimal furnishings. I didn’t place any rugs on the floor. The sensation of bare feet on the wooden floors became the essence of home.

I grew accustomed to the sight of the swing swaying in the breeze and to the soft, warm touch of the grass in the garden. Even though the sofa and most of the tableware and other contents of the kitchen cupboards belonged to someone else, after six months I already felt as though we’d been living there for years. I loved strolling along the river embankment at dusk on my days off, gazing at the surface of the water.

In early spring dogwood bloomed white and pink outside the houses, and wooded areas here and there were full of the white flowers of robinia trees. We’d moved into this house in spring but, before we knew it, it was already autumn and the landscape was changing rapidly.

I only realized that the trees in front of our house were robinias when the white flowers came into bloom. When I opened the windows, the curtains puffed up in the breeze, carrying their heavy fragrance. The blossoms made the whole neighborhood feel cheerful. I had never lived anywhere with such a fragrant breeze before.

My days were now so peaceful I could scarcely believe I had once been possessed by the yellow sickness.

It was at this point that I met my cat. She would never have been able to sneak into my unburdened heart the way she did had this place not been colorless and transparent. I was giddily happy, no longer irritated by sand or continually running around with a duster. Maybe it was because my defenses were down that I readily welcomed her into my life after our eyes met, our skin came into contact, and I set off walking without a second thought.

Kitten tiny

Claws see-through like egg white

Ears moving listening

Eyes moist limpid

The faint smell of liquor in the neighborhood

night

You’ve come from far away

Welcome hello

Me human you cat

***

It took us days to come up with a name for her. Naming an animal is hard, really hard. I would come up with names like Ringo, Umi, Muru, and Tama but end up crying, “Oh, I just don’t know!” However hard I thought, I just couldn’t find a name that suited this little kitten. My husband said flippantly that it didn’t matter if she didn’t have a name, but it was so inconvenient for her not to. How was I supposed to call her without a name? And it occurred to me that the only real difference between stray cats and pet cats was whether or not they had one.

Meanwhile, we were calling her “she” or “the little one.” Then, one day, we started calling her Mimi. The kitten cried an astonishing amount, whenever she wanted milk or played with the curtains or struggled while we were removing fleas. Her high-pitched mii-mii sounded somehow sad, as though she was calling for her mother, and made my chest constrict. This mii-mii got shortened to Mimi, but the name didn’t last long. It proved somewhat tricky to say Mimi out loud, and my tongue stumbled over it every time.

After a few days, then, Mimi got shortened even further to just Mii.

Later, I would sigh over the fancy names people gave their cats: Randy, Jajamaru, Sasuke, Marilyn, and so on. All of my friends’ cats, and the numerous cats in the books I browsed at the bookshop or came across in novels or newspaper columns—all of them had names with an appropriately cute ring to them.

My cat was called simply Mii. We sometimes nicknamed her Mii-tan, but her formal name was Mii Inaba. I simply couldn’t manage to come up with a better name for her, however hard I tried. Her mew-mii, mew-mii way of crying that I’d first heard when she was hanging there in the dark had somehow stuck in my heart and wouldn’t go away.

And thereafter, whenever I called her name, she would naturally answer me, mii. Mii had decided on her own name with the sound of her cries.

Nobody knows your real name

From a dark corner in our new neighborhood

You were a voice that came raining down

Like stars like gems

Like little grains of light knock-knocking on

the door

Music was playing in the distance maybe Yesterday

Your yesterday singing

Telling of the past saying goodbye to today

singing in the distance

I wanted to believe it

Like a freshly laid egg a brand-new you

Maybe I should have called you Tomorrow

Or maybe Dawn

Where do names come from?

You answer simply, mii

From Mornings without Mii, translated from the Japanese by Ginny Tapley Takemori and to be published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux next month.

Mayumi Inaba (1950–2014) was a prize-winning novelist and poet. Her works include The Sea Staghorn and To the Peninsula, for which she won the Kawabata Yasunari Prize and the Tanizaki Jun’ichirō Prize.

Ginny Tapley Takemori is the award-winning translator of Sayaka Murata’s Convenience Store Woman and other works of contemporary Japanese literature. She lives in rural Japan with her husband and three cats.

January 17, 2025

Making of a Poem: Emily Osborne on “Cruel Loss of Sons”

An early draft of a stanza of “Cruel Loss of Sons.”

For our series Making of a Poem, we’re asking poets and translators to dissect the poems they’ve published in our pages. A selection from Emily Osborne’s translation of Egill Skallagrímsson’s “Cruel Loss of Sons” appears in our new Winter issue, no. 250.

What was the challenge of this particular translation?

The poetry of the Icelandic and Norwegian skalds, or poets, from the Viking Age—the late eighth to mid-eleventh century C.E.—is notoriously challenging to translate. It was composed orally and passed down orally for generations before being written down in manuscripts. As a result, in the extant manuscripts and runic fragments found on sticks that preserve the poetry, we find variations in redactions, illegible or illogical word choices made by scribes, and frequent references to obscure myths and cultural traditions. Simply understanding a skaldic poem requires a fair amount of background scholarship. The skaldic practice of using compound kennings, in which metaphors and symbols are substituted for regular nouns, adds another layer of complexity. For instance, in this poem, Egill calls his head the “wagon of thought,” his mouth the “word-temple,” and Odin the “maker of bog-malt.”

Above and beyond gleaning the literal meaning of words, a translator must also be able to understand the frequent and surprising tone shifts that add shades of insinuation or emotion. Statements that seem illogical could be ironic or expressing litotes. In “Cruel Loss of Sons,” I found it particularly difficult to interpret Egill’s tone when he speaks of his strained relationship with his patron god, Odin, and the other gods after the death of his sons. In lines such as these, the emotions communicated are ambiguous: “I was on good terms / with the spear-god, / trusted in him, / tokened my loyalty, / until that trainer / of triumphs, champion / of chariots, cut cords / of closeness with me”; and “I’d scuffle with / the sea-god’s girl.” Is the poet indicating betrayal? Sorrow? Defiance? Incredulity? Anger? Self-deprecation? Absurdity? When translating, it can be hard to avoid pinning down the tone too neatly. My task with this poem was to allow grief to carve out its own emotional track.

How did writing the first draft feel to you?

It felt like joining a lineage of transmission fueled by persistence and sorrow. “Cruel Loss of Sons” was, as far as we know, composed orally by Egill in the mid-tenth century. The poem made its way into the later medieval prose saga about Egill, Egils saga Skallagrímssonar, which survives in various forms in various manuscripts and manuscript copies of the thirteenth century and after. Questions of origin and authenticity naturally present themselves. Still, I find this lineage of transmission a compelling testimony to the poem’s ability to move audiences separated by centuries.

Grief, it seems, was the catalyst for transmission. Egils saga Skallagrímssonar tells how Egill was so overcome with grief after his sons’ deaths that he resolved to starve himself to death. His daughter, Thorgerd, convinced him to live by arguing that, if he died too, no one would be left to compose a fitting memorial to their dead kin. She promised her father that, if he composed the memorial poem, she would carve the words on a rune-stick.

Egill opens his poem with an image of struggling to lift up “poem-beams” in order to “drag” poetry out of his mind. The difficulty of constructing an elegy becomes a recurring theme in the work. In the Norse “mead of poetry myth,” an elaborate etiological story referenced in “Cruel Loss of Sons” and other medieval Icelandic sources, Odin gives humans and gods the ability to compose poetry by stealing a fermented, “inspirational” liquid from the supernatural race of the jötnar. I was struck by how Egill mentions Odin’s risky journey to steal this mead so lightly and quickly while spending far more words on his personal difficulties in composing a poem about his dead sons. Composing this poem was grueling for Egill, and I think any translator would feel a sympathetic burden. Translating someone else’s suffering should feel like heavy labor, even across centuries and cultures.

Did you show your drafts to other writers or friends or confidantes? If so, what did they say?

In 2017, I read a freer, more impressionistic translation of part of this poem to an audience at the Vancouver Public Library. It was the first time I had presented one of my Norse translations to a nonacademic audience. The positive feedback and curiosity were overwhelming. Many people were surprised that the Vikings composed poetry at all, let alone sophisticated verse. These reactions first gave me the idea to translate an anthology of skaldic poetry for a general reading audience, partly in order to bring wider attention to a relatively unknown aspect of Viking and medieval Scandinavian culture.

The next time I shared a translation of “Cruel Loss of Sons” with someone wasn’t until 2023, when my husband read my more literal translation of the entire poem. I’m fortunate to be married to a writer, Daniel Cowper—we exchange our writing and are comfortable giving each other’s work tough love. When he read “Cruel Loss of Sons,” he didn’t suggest any edits—a rare thing for him! I have made changes since and am sure I will make more, but I think the positive reactions readers have had to my drafts, though they differ greatly from each other and range from impressionistic to literal, speak to the richness of the original poem. You can tap into various veins and mine precious metals.

When did you know this translation was finished? Were you right about that? Is it finished, after all?

I never think of my translations, or the translations of others, as fully finished products. Nor do I think of a translation as producing a static mirror of an original text. Rather, translating is a bit like setting in motion a disco ball. As the ball turns, it reflects its surroundings in myriad impressions and scatters countless points of light back onto its setting and viewers.

Readers and scholars tend to argue for a “best” translation based on certain criteria—maybe accuracy, beauty, or readability. To me, any translation invites further translation and interpretation. The near-limitless possibilities are exciting, and even readers who have no familiarity with the original text can wonder how things could have been done differently.

What appears of “Cruel Loss of Sons” in issue no. 250 are selections from a longer poem. Srikanth Reddy and the other editors at The Paris Review wisely chose stanzas that track Egill’s intimate response to grief. Other stanzas engage more deeply with religion, myth, war, and social norms. My translation will appear in its entirety in my forthcoming anthology of translations, The Skalds. I imagine that before the book is published, I will make further edits to these stanzas, given that they will appear in the context of the rest of the poem. Rather than considering the version published in The Paris Review to be finished, I think of it as part of a tradition of preservation that can be traced back to Thorgerd and her rune-stick.

Did Thorgerd fulfill her promise, converting her father’s poem from spoken words to written runes? Was she the first preserver and publisher of this poem? Is the story of the poem’s origin even true? I cannot know for sure, but I can say I am inspired by the drive of the Vikings and their descendants to preserve and pass on their stories and poems, no matter the difficulties.

Emily Osborne is the author of the poetry book Safety Razor. Her anthology of translations of Old Norse poetry, The Skalds, will be published by W. W. Norton in 2027.

January 15, 2025

Spanish Journals

Photograph by Catherine Lacey.

I kept this notebook during my first intensive period of studying Spanish in Oaxaca in November of 2022. I didn’t know then that this study would soon be interrupted by almost two years in New York. As I looked through it more recently, it became clear how cheerfully deranged the early days of learning a new language appear from even the slightest distance.

I am, you are, he is, we are, they are. I am a student. I am a writer. He is Mexican. She is a pilot. I was stupid. She was a pilot I was a marathoner until my accident.

Yesterday was Monday. I am not accustomed to it. I am tired. I am happy. I am learning Spanish.

That woman is never angry. Where are your friends?

The soup is very hot. They are afraid of my cat! Why? I don’t know. They have to do the shopping today. We have to go home. I have to work now. I have to see him this afternoon.

I try, you try, he tries, they try, we try. I tried. You tried. He tried. To teach. The taught Spanish to my son. They taught it to him. I have a question.

Can you speak louder, please? Can you speak more slowly please? I am sleepy. I am sleepy but I have something to tell you first. I learn, you learn, they learn.

How do you pronounce … What does it mean … Can you say … What is the difference between … How do you say … How do you pronounce … Can you repeat that, please?

Hello. How are you? What is your name? I am Catherine. My name is Catherine. What is your last name? What is your job? How many years do you have? Her name is Frida Kahlo. She is a painter.

I am not American, I am a person from the United States. Take care. Enjoy your weekend. I hope that you are well. Very. A lot. Many. Many. To live. To live in the past. I visit, you visit, he visits, we visit. We lived.

To go out. I am going out. You’re going out. I left the office at five. You left work early. What are you doing in the afternoon? Sara is making dinner. Sara makes dinner for us on Sundays. She makes breakfast before eight. I’m going to make you a soup.

How is the weather in Boston? There is a lot of sun in Barcelona. Sometimes there is heat here. It rained. It rained. It snowed. Some years ago.

When do you want to buy groceries? We have to buy groceries. Are you going to buy groceries? Did you eat something yet? We ate something together. He lived in Madrid for four years. I walked through the city. I ate dinner with my boyfriend in October. When do you leave for work?

Today the weather is bad. What do you feel like eating? Noon. Twelve o’clock. Midnight. Seasons. Times. Periods. Ages. The tacos come with guacamole. I have a desire to eat tacos. Do you want to eat lunch with me tomorrow?

How are you feeling today? Sometimes I am angry with my father. My mother feels a little tired today. I don’t feel good. How does your brother feel? Is your sister bored? They feel angry. The women are angry. I am very excited. You are angry sometimes.

I want to drink something. I want to dance. I think you’re going to like it! I was living in the city until March. I enjoy myself. I wake up. What are you think about? We think you’re going to like it! I know when your birthday is. Do you know Spanish? I need to know more words. I don’t really know. I don’t know why.

I think life is marvelous and I love to swim! We love cheese very much. I like to eat it. I want to eat it. Where did you spend Christmas last year? Casually. I like him. I don’t like him. I know many young people. I can use this pen. I want to be able to speak Spanish. I cannot remember. She cannot live in this house. Come back soon!

We are going back to Spain this summer. My children returned to school. When are you going? I don’t want to go to Seattle in the fall because it is always raining. I lost. You lot. We lost. You try. We try. It hurts. It costs me a lot. I start work Monday. When does school start? They do not start today.

Will you help me? We help many people. Can you help us with the bags? You have to put on your pants before you open the door. I love that pair of boots. I feel lazy. Tall. Short. Fat. Thin. Ears. Body. Feet. Square. Circular. You open the gifts.

Where did you put the bottle? Where did you put the dog? It’s foggy. Try the soup.

I recommend that you try the tlayuda. Brenda is more elegant than the girls. This is the worst restaurant in town. The vegetables are better than the fruits. There are my favorite songs.

Are you interested in this conversation? Life makes me laugh. Unfortunately. Smell. Open the window. Make the coffee. Wash it after you use it. Don’t go out at night. Don’t be stupid. Put the keys on the table. Don’t go to that restaurant. You wash your hands. I wash my hands. We want to wash our hands.

Maybe tomorrow I will go to the party. She is not going to invite us. We don’t have to stay home. Arrive. Give. Wash. To play. To create. To cry. To turn off. Cost. To miss. To promise. It makes sense. I am happy here.

Catherine Lacey is the author of Biography of X and a forthcoming work of nonfiction, The Möbius Book.

January 14, 2025

Glimmer: In Siena

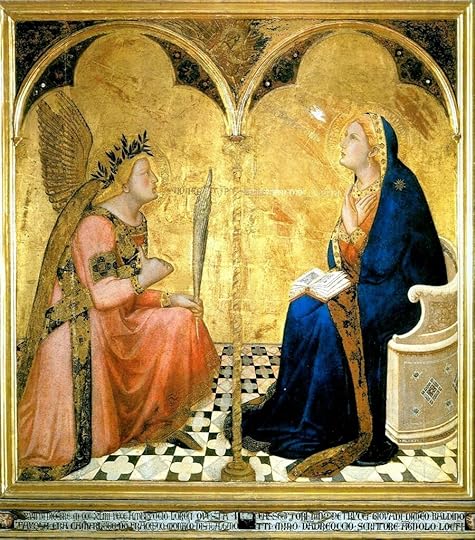

Ambrogio Lorenzetti, Annunciation, 1344, via Wikimedia Commons. Public domain.

The last time I was in Siena there was an earthquake. The first time I was nineteen. My boyfriend, who had already graduated from college, had been in Italy most of the year, in Perugia. The plan was to take an intensive course in Italian—he wanted to read Dante—but then he discovered a passion for painting. Could it have been the day after I arrived that we took the train from Perugia to Siena? Even now, from Perugia, one changes train twice, first in Terontola, and then at Chiusi-Chianciano Terme, a station that decades later would become familiar, arriving in the Val D’Orcia from Rome, and where one afternoon we sat deathly ill in the station bar, beset by what—an ability to go on? But then everything was new.

In Umbria, the landscape is mist and the hills are often in shadow, the luminous inner life is a long let-out breath, but as the train trundles into the province of Siena, the light sharpens like a scalpel, and the shadows disappear. The usual bustle at the station. Then, a stone’s throw from the Duomo and the Piazza del Campo—which erupts in July with the running of the horses in the Palio—the Pinacoteca Nazionale is housed in two adjacent palazzos. On four floors, it holds the most important collection of Sienese paintings in the world. The core of the collection was assembled by two abbots, Giuseppe Ciaccheri and Luigi de Angelis, painting by painting, between 1750 and 1810. They knew, somehow, that these unfashionable, strange, mystical, transfixing pictures, which hovered between Byzantine art and abstraction, painted in the margins of the history of art, many salvaged from triptychs and altarpieces that had been sold, dismantled, or lost, were worth saving.

On that first visit the galleries were nearly empty. I had been brought up on twentieth-century painting—my grandfather had taken me on Saturday mornings to what was then called the Modern, but I had very little idea of painting as narrative. The only picture I knew that had the quality of continually happening in time was Picasso’s Guernica. But that is another story. Here in Siena was one chapter after another of a different story: the Annunciation, the Madonna and child, miraculous episodes, the Cross, the eternally mystifying Second Coming, the Assumption. There were the perplexing lives of the saints. Each figure was aglimmer, as if these narratives were continually occurring, unfolding even then as we looked on. My own understanding of these stories was limited—it amounted to being taken to see the Christmas windows on Fifth Avenue and listening to my father sing carols in the car. But I knew, even as I arrived from that distance, that these paintings from the trecento were ones to which from now on my attention would be directed. Later, when my first child was born—who grew up to become a painter—one of the first places I took her was to see the Italian paintings at the Met, where she fixed her eyes on the gold light.

But that day, it was perhaps no accident that my favorite painting was a small green panel by Stefano di Giovanni, later known as Sassetta, of a traghetto, its hull like the inside of a peapod, pulled up to a bank beside a castle. It was one of the only—and earliest—representations of a secular subject in the galleries. That fall, when I returned to school, I found myself often at the university art museum, where I went to look at a tiny crucifixion by Simone Martini, painted sometime between 1315 and 1344. I cannot say exactly what drew me to it. The Christ figure, emaciated, is nailed to a simple wooden cross. No one else is there; it is a scene of complete loneliness. Blood spurts from Christ’s side, drips down his emaciated arms, and cascades from his feet down the base of the cross. The background is gold leaf, layer upon layer, so that the scene is entirely irradiated with light. It was my last year at school. Why this scene of horror comforted me, as I was about to step out into the world, I cannot say, but the painting was alive to me with the hand of its maker.

In the current Met exhibition Siena: The Rise of Painting, 1300-1350, very few of the paintings are borrowed from the Pinacoteca Nazionale in Siena or even from Siena at all, but the ones that are include the Ambrogio Lorenzetti annunciation, in which the Virgin, surprised at her book, fixes her perplexed gaze on the dove rather than on the angel. There is also the exquisite Maestra, by Duccio, painted in his workshop on the Via Stalloreggi, steps from the Duomo, which stayed in place in there until 1771, when it was dismantled. But most of the paintings and objects have been brought together for the first time in hundreds of years, from museums in the U.S. and across Europe.

Of these masterpieces, among the most striking, at least in terms of scale, is Pietro Lorenzetti’s Tarlati polyptych for the Church of Santa Maria della Pieve in Arezzo, in which the saints, going about their business, are framed by arched windows on three stories. In the Met’s dimly lit room, looking at the gigantic polyptych is like gazing into an apartment building at night, where the tenants, not knowing they are observed, can be seen conducting their discrete business of life on earth. At the center is Mary in a white gown and hood embroidered with rosettes, perhaps putting the plainly garbed Christ child to bed. On the upper and lower stories are a score of saints, the usual suspects—among them John the Baptist, John the Evangelist, and Saint Matthew—and four women who were Christian martyrs: Catherine of Alexandria, Ursula, Agatha, and Reparata, who was saved from being burned alive by a shower of rain. The Sienese artists painted the saints from models they knew—their sisters and mothers, men and women who lived down the street, and then, over decades, the children of these men and women. Those faces, both mysterious and familiar, are held here by time’s gaze.

This show, which includes one hundred–odd paintings and objects, is so luminous that it is difficult for a viewer to comprehend that the assembled works were made over the course of just fifty years. At the end of this apotheosis, from 1346 to 1353, the black plague drew its deadly brush across Europe, killing almost fifty million people, including most of these painters and the models for these paintings. Just a few years ago, would we have had any idea what that meant? It is always news that we can go on. It may be part of the solace of this brilliant show.

When I arrived at the last room of the exhibit, I realized I was looking for something. I turned, and there it was, the crucifixion by Simone Martini, which I’d spent so many hours looking at in Cambridge long ago. I saw now that there was a smudge of gold leaf on the left side of the cross—was it a figure the artist blotted out? A friend who writes about the history of art believes that paintings have their own experiences across time, as we do, and that those experiences become part of the paintings. Perhaps this is so.

Simone Martini, Christ on the Cross, ca. 1340, via Wikimedia Commons, licensed under CC0 4.0.

According to an essay by Stephen Wolohojian, in the amply illustrated book that accompanies the Met exhibit, Ambrogio Lorenzetti was among the great storytellers of the fourteenth century; he was a teller of secular tales, as well as sacred ones. Lorenzetti’s work, and his brother Pietro’s, are represented here, but one of the masterpieces in Siena, which did not travel to the Met, is Lorenzetti’s Allegory of Good and Bad Government. This hangs in the Sala della Pace (the “peace room”) of the Palazzo del Popolo, Siena’s town hall, where the nine elected city magistrates once conducted civic business.

On that long-ago visit to Siena, we made our way from the Pinacoteca to the Palazzo Popolo, where the Lorenzetti frescoes cover three huge walls and portray the effects of good and bad government in the countryside and the city. In the first instance, the vision of good government is ruled by Faith, Hope, and Charity. (According to Ruskin, writing about the frescoes in 1870, Hope, who crowns the benign leader, is the most important of these virtues, which may be something to keep in mind.) But in the latter, scarifying images, pestilence ranges in the fields; in town, the ruler wears a devil’s crown, and keeps a Cerberus as a pet. Like the meticulously illuminated tribulations of the saints, the murals—with Lorenzetti’s strange, Edward Gorey-like figures and his weird dragonfly angels—were meant to instruct. As we looked at them then, I saw, as if transposed by a stereopticon slide onto the maleficent landscape, Picasso’s rearing horses which had transfixed me as a child. That summer, Dante accompanied us. “Nel mezzo del cammin di nostra vita, mi ritrovai per una selva oscura, che la diritta via era smarrita,” M. read aloud.

Lorenzetti’s frescoes, via Wikimedia Commons. Licensed under CCO 3.0.

The last time I was in Siena, on a hot day in June, it was cool in the museum. I’d found Sassetta’s painting of the tranquil boat pulled up to tranquil bank when from outside the building came the sound of a tremendous crash, as if two trucks had collided on the Via San Pietro. The floor swayed. Un terremoto! exclaimed the museum guard, gesticulating wildly towards the stairs. Un terremoto! Andare fuori, andare fuori! With the other bewildered museumgoers we were hustled down the stairs and exited the building, where on the narrow street a gaggle of tourists, unimpressed by the tremor, wandered by eating technicolor gelati.

I had planned to visit the Lorenzetti frescoes after the morning in the Pinacoteca, but because of the earthquake, which registered 3.7 on the Richter scale, and whose epicenter was ten miles away, in Poggibonsi—the Duomo, even the great apron-shaped piazza where the horses were due to run in a week’s time—were immediately shut so that structural damage could be assessed. I was sorry not to see them. But I think I knew then, with foreboding, that like so many stories that accompany us, waiting to go on, flapping their bat-like wings until the curtains part, I would see Lorenzetti’s allegory again—if not in Siena, then closer to home. What to do? Everything was closed. We walked up the street in search of a cold drink, and as in the lucent paintings of the trecento, the slant light turned the streetscape two-dimensional and the brilliant sun left no shadows.

Cynthia Zarin’s most recent books are Inverno, a novel, and Next Day: New & Selected Poems. Her second novel, Estate, is forthcoming. She teaches at Yale University.

January 13, 2025

The Tickling of the Bulls: A Rodeo at Madison Square Garden

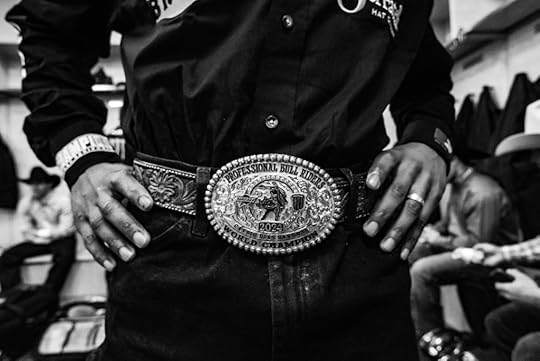

Photograph by Austin Aughinbaugh. Courtesy of Studio Augie.

A 1,650-pound American bucking bull named Man Hater paused at the entrance to the Madison Square Garden floor and fixed me with his dark, soulful eyes. “Hi, puppy,” I said.

A bearded wrangler scoffed. “That’s no puppy.”

Before opening night of the Monster Energy Buck Off at the Garden, on January 3—the eighteenth annual such event and first to sell out all three days—a small press corps had gathered by the tunnel to watch the athletes arrive. Not the human athletes but their bovine counterparts, which plodded up the corridor, chased by a mounted cowboy chanting in a low voice. The bulls advanced with the sheepish dignity of prizefighters in ill-fitting suits.

In a few hours, these animals would try to buck their riders, who would try desperately to stay on for eight seconds—the basic drama of a rodeo. A popular myth claims rodeo bulls are compelled to buck by a strap wrapped around their testicles, but as any spectator can observe, these are clearly swinging free. “Take a rope, tie it around yours, and pull it up tight—and see how high you can jump,” says Chad Berger, a livestock contractor, in a Professional Bull Riders (PBR) promotional video meant to dispel this misconception. The real instigator is a strap wrapped around the bull’s flank—an annoyance that provokes an animalistic urgency to get it off, a response I know well, having once attempted to put pants on my dog for Halloween. “It’s basically like if I tickle your armpits—that’s about what it does to them bulls,” Berger says. Madison Square Garden’s three-day Monster Energy Buck Off, I learned, would be fueled by a tickling of the bulls.