The Paris Review's Blog, page 11

April 3, 2025

What Stirs the Life in You? The Garden Asks

Each month, we comb through dozens of soon-to-be-published books, for ideas and good writing for the Review’s site. Often we’re struck by particular paragraphs or sentences from the galleys that stack up on our desks and spill over onto our shelves. We sometimes share them with each other on Slack, and we thought, for a change, that we might share them with you. Here are some we found this month.

—Sophie Haigney, web editor, and Olivia Kan-Sperling, assistant editor

From Water by the Persian mystic Rumi (1207–1273), translated from the Farsi by Haleh Liza Gafori (New York Review Books):

The Garden’s scent is a messenger,

arriving again and again,

inviting us in.

Hidden exchanges, hidden cycles

stir life underground.

What stirs the life in you?

The garden asks.

The garden thrives.

Invites us to do the same.

Saplings break through darkness—

ladders set against the sky.

Mysteries ascend.

From Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s 1972 Nobel lecture, translated from the Russian by Alexis Klimoff in We Have Ceased to See the Purpose (University of Notre Dame Press):

Just as the savage picks up in bewilderment … a strange discharge cast up by the sea? … something long buried in the sand? … a baffling object fallen from the sky?—intricately shaped, now glistening dully, now reflecting a brilliant flash of light—just as he turns it this way and that, twirls it, seeks a way to utilize it, seeks to find for it a suitable lowly application, all the while never guessing its higher function …

So we also, holding Art in our hands, self-confidently deem ourselves its masters; we boldly give it direction, renew it, reform it, proclaim it, sell it for money, use it to oblige the powerful, divert it for amusement—all the way down to vaudeville songs and nightclub acts—or else adapt it (with a muzzle or stick, whatever suits best) toward transient political or limited social needs. But art remains undefiled by our endeavors, and the stamp of its origin remains unaffected: each time and in every usage it bestows upon us a portion of its mysterious inner light.

But can we encompass the totality of this light? Who would dare to say that he has defined Art?

Three extracts from the eponymous poem of Aharon Shabtai’s new collection, Requiem and Other Poems (New Directions), translated from the Hebrew by Peter Cole:

Come and see:

Father is

made of air,

and even the chair

and the blows are abstract

*

Life begins

with a siren

in the middle of the night,

with all of the neighbors descending

to the shelter

beneath the ground

and afterwards climbing

back up and dispersing

and then as usual

coming back

*

Under the heavy blanket,

as though in a submarine,

embracing one

or a pair of girls

at night you’ll navigate

far and into the depths

down down

and suddenly in the dark

on the sheet

the white liquid

pools

From “DEATH HAS THE BIGGEST DICK OF ALL” in Ariana Reines’s poetry collection The Rose (Graywolf):

Probably the reason women are still attracted to the devil

& will always be is that’s who fucked us

Originally

To get life onto this planet

From Sayaka Murata’s novel Vanishing World (Grove), translated from the Japanese by Ginny Tapley Takemori, about a girl in love with a cartoon character:

Until now I’d thought my purest instinct was the sexual attraction I felt for Lapis. I’d taken solace in the fact that my arousal was something consistent with what society deemed common sense.

But maybe I was wrong.

April 2, 2025

Father and Mother

Photograph by Kalpesh Lathigra.

The setting: sixties Paris, Saint-Germain-des-Prés, full of rich men’s sons, and their daughters, too. On my mother’s side there were four sisters, just as on my father’s side four brothers, the same madness on each side of the family, because families are always mad. She was the youngest, born in a château. When they met she was living in a large apartment on the rue Bonaparte, with the sister closest in age, the one who’s going to die of alcohol and pills. Overdose or suicide, hard to tell in these cases. The building belonged to her family, to their family, to my family, in the entrance hall there was a marble bust of an ancestral baron and they had cousins on every floor. Her own father, my grandfather, died when she was fourteen, he was also an MP, a government minister even, but he had been dead for a long time. Her mother, my grandmother, lived in the southwest with her dogs, and came to Paris from time to time to see what was happening. There were arguments, tears, scenes. Everyone in that family was violent. Aristocracy makes you crazy. Not because of the inbreeding, but because of faith. Faith that it is possible to be noble. In that family they raised children like they raised horses, to be beautiful. Being beautiful meant lots of different things. The rest was of no importance.

After the bac, after all those years at boarding school with the nuns, she signed up for classes at the Sorbonne, and she was stopped in the street. They offered to take her picture, she posed for magazines, walked in runway shows, became a model, there was something terrifying in her beauty, for everyone, for her as well.

When she comes to pick me up from school, ten or fifteen years later, that is what I see. Among the other mothers, normal and ridiculous, she is taller, thinner, with her big coats and sunglasses. Even the fat unruly spaniel at the end of his leash makes her look only more royal. She could have gone around walking a pig and everyone would find it perfectly normal, even sublime. Everyone makes way for her when she walks down the street, it’s like they feel compelled to bow to her, or to carry the hem of her coat, or to adopt the most sophisticated protocol, like in the empire of China in the first few pages of René Leys. I am amazed they even manage to address her directly, they even sometimes call her tu. She calls everyone tu. She is very warm. Never a snob. Keep it simple, she says to anyone who never manages to be. Proust’s Duchesse de Parme. They all fall under her spell. Everyone. I see it. It grabs hold of them. It’s physical. They are no longer quite themselves. My friends, my friends’ parents, the baker, a bum, it doesn’t matter who, she turns them all to jelly.

When I am with her, I watch things happen, it never fails. The way they desire her. A crazy, respectful desire. You don’t fuck a queen up against a wall. You may think of nothing else, but you don’t touch her. You hope that she will lower herself to your level. That she will lower herself and fuck you. My mother always enjoys it. She parades her sovereign desire throughout the world. To be her child is to be sexual before anything else, because she is. To get hard and to come, to be frustrated and perverse, voyeur and pimp, calm and furious. I am a witness or an accomplice, I watch people fall beneath her gaze, I am the favorite son or daughter, I am the crown prince, tu quoque mi fili, you too, my child? I delight in it I am enraged by it, I am waiting for my hour.

Now, when I look back, I think she was crazy. I’ve thought so for a few years now. Since I started dating women. Since I came to understand that all women are stark raving mad.

***

Jeans, black loafers or Clarks, blue Oxford shirts; a tie, always; a blazer; a jacket; sometimes a turtleneck; sometimes a leather jacket, never a coat; his cigarettes; his slimness; his pallor; his gray eyes; my father is always elegant. He doesn’t have many clothes, he buys them at the first shop he sees. Elegant without thinking about it, elegant because he doesn’t care. Even now, even old, even in his pajamas, like last summer at the hospital for his tongue cancer, even in the country in his putrid house in a dirty sweater and his supermarket jeans, with his oxygen tank, his pacemaker, his Subutex and his morphine, even with his poverty, filth, aging, and death, my father is elegant. Elegant in not giving a fuck about anything, clothes, money, himself, and everyone else. Never asking any questions, never saying anything. Elegant in never being there. For the past few months if anyone bothered him about anything he’d say Leave me the fuck alone I’m trying to die here. Before, he said nothing, he just took a hit or had some whiskey without looking anywhere in particular. His decline lasted thirty years. Or maybe forty, or fifty, it’s hard to say. For a long time, it was the fire brigade, melodrama, one crisis after another. For the past decade or so hardly anything happened, it was all so slow, like tai chi. He hardly moved from his armchair, looking straight at the TV. To his left, the fireplace, with its mountain of ash, full of burned-out old yogurt pots, ice cream wrappers, medicine, everything he tossed in there. The house was overflowing with broken things and dust, the garden full of weeds and too-heavy branches that always succumbed to their weight, as if his indoor space were spreading outside. It was his obsession with abandonment, impotence as will, that’s why we could never intervene, it was impossible to repair anything, and so to spend time in this house was to spend time with the dust and the cold, the iced-over radiators, the chipped plates, the missing light bulbs, the dead sockets, the busted-up tiles. The Montlouis aesthetic was an aesthetic of the garbage dump, with everything frozen somewhere between sinking and resisting, but it wasn’t clear if the two effects—annihilation and invincibility—would find a synthesis. From time to time, in Paris, those who knew him would ask how he was. They were thinking of the charming guy they hadn’t seen in thirty years. Charming, they said. I didn’t say charming, if I’d said charming I too would have remained at a distance from him. From the void. From the violence of the void. He didn’t say a word about it. There is nothing to be said. These kinds of things are solitary. Kindness surrounds us, it’s peripheral, it supports us. Extreme kindness, even; politeness; tact. These things dwell on the surface of the life he did not inhabit, one he did not care about. I rarely saw my father, I didn’t speak to him very often, I didn’t call him. In any case that’s exactly what he asked for, that we leave one another alone. When you think about it, it’s alright that way. He didn’t tell me anything and I didn’t tell him anything either. I treated him the way he treated everything, I shrugged my shoulders and went on my way.

He is all that remains of my childhood, with his oxygen, his Subutex, and his illness in the falling-down house in Touraine. Luckily that house will not come to me. I will not inherit anything. The two armchairs, the photographs, I relinquish it all to my sister in advance. I don’t speak to her. In a few months perhaps, this whole story will be completely over. That’s why I’m waiting for him to die. It is happening unbearably slowly.

When they met, he was finishing his law degree and starting a career in journalism. He lived in a studio in the rue Grégoire de Tours, above a Greek café called Zorba. His father, my grandfather, the one whose name I bear, had been prime minister. He wrote the constitution. Headed up one ministry after another—defense, finance, justice, foreign affairs, that kind of thing. As a young man my father had his own bedroom in Matignon. He had three brothers, one elder and two younger. He wasn’t interested in his family, or in family stories, or in speeches about the family or France. He was nothing like the rest of them. Sometimes a person is born into a family they don’t resemble at all. He spent his childhood with his nose in a book so he wouldn’t have to see or hear them. He wanted to escape. He wanted to be Kessel, Monfreid, Albert Londres, not Paul Reynaud, not Charles Bovary. His earliest reporting was in Africa, then Asia. Wherever there were wars. Violence and beauty, it’s always the same story. Drugs, too.

He’s a journalist, he travels, he writes books. He talks. The Opium Wars. Speeches at the House of Commons. Chinese dynasties. The opium dens of Toulon. The Second Empire. Dylan. Rimbaud. Malaparte. Malcolm Lowry. Les lauriers sont coupés. Norman Mailer. Painters too. A thousand other things. His gentle voice. He played games with me. I built my worlds with him. My Legos, my forts, my costumes, our stories. We built worlds. My father understood childhood.

Africa and then Asia. Wars. Biafra, Vietnam, Cambodia, Mao’s China. He knows each of these countries, their ancient cultures, their histories, he says that we’re the barbarians. He can talk about it all for hours. He leaves as soon as he can. He is always leaving. My father watches everything with his gray eyes, he talks about the world, about books, but when it comes to himself, he keeps quiet, he gets lost.

What does it do to you to see all of that, dead bodies, children with enormous bellies, bush hospitals, the smell of blood, of ether, of gangrene, to see barefoot fifteen year old boys armed to the teeth on a deserted road, what does it do to you, the noise the night the anti-aircraft fire in the helicopter. Fear, death. Passport in his pocket. He’s off again. French journalist. War reporter. Death brushes past him, blows on his neck, but she’s more interested in other people. It could happen but it never does.

With him: kebabs in Barbès, the flea market in Saint-Ouen, army-navy surplus stores. Military clothing. I have forage caps, kepis, fatigues. I am extremely well informed about uniforms, armies, ranks. Present arms, attention, at ease. I’ll go to Polytechnique if you want. Or I’ll be Lord Jim. I listen to Bach. I don’t know where I discovered Bach, my parents’ tastes are more modern, but I’m obsessed with Bach.

I enter my mother’s world, but my mother’s world is not the world, it’s her. Everyone does that with her. We watch her, we realize we’ve never seen anyone like her, we let ourselves be drawn in, we tell ourselves that nothing else exists but her. My mother inhales you, she swallows you up. You’re in the belly of the whale. It’s beautiful, it’s hot, it’s spectacular. You don’t want anything different. My father is also like that, with her. He and I are like that, we look at her and try to understand what it is we’re seeing. To be swallowed up by her is so good. Sometimes we can’t bear it, so my father goes off to do some reporting, he goes to China, he disappears. I have asthma, I suffocate, at night most of all. Like Bacon, like Proust. The illness of geniuses. I spend my childhood with an inhaler in my pocket, a little blue dildo next to my thigh, my own little fix.

My mother at this time: an apartment a quiet life a husband a child a spaniel. And sunglasses boots coats and makeup which signal anything but ordinary life. You can’t have a normal life when you have that face, that look. Always made-up. I hardly ever saw my mother without makeup. Very very rarely. Even at the end when she hid her terrible whiskey under her pillow.

Who could ask for a more perfect dealer than a Belgian princess, Fanchon van something or other? She had also been a model. Fanchon wasn’t her real name. Aristocrats nickname each other after horses. When I think of the word bohemian, I think of Fanchon’s apartment, dark and messy, clothes strewn on sofas, pillows, curtains, a theatrical atmosphere. Malte Laurids Brigge via Nan Goldin and Cookie Mueller. We stop in for five minutes after school. It’s two minutes away, a little ways up the rue Saint-Jacques, across from the Musée de la Mer. They ask me to wait in one room, my mother goes off with Fanchon, comes back to get me. My sense of what’s going on is vague, but I have a sense of it all the same, kids are not that dumb. Usually it’s my dad who goes to see Fanchon, he calls, he says, Can I come by, he goes, alone. Usually it’s my dad who takes care of the drugs, he’s been a junkie since he was twenty, that’s what interests him in life. That and my mother. Even after her death. For years and years afterward. Drug addicts are strong, they’re unstoppable, like warriors.

They always fought. Whether or not I was there didn’t change anything. He was the one who hit her, but it seemed to me, nevertheless, that she was the one who wanted violence, who was violence, she brought it out in him, a violence he hadn’t previously known. Without her he was never violent. Never was after her, either. In no other phase of his life, no matter what happened, did I ever see anything more than mild annoyance flare up. I never saw him get angry. Even with the drinking, through the most difficult times, he never raised his voice. Gentle as a lamb. Gandhi. With her he became something else. He had access to something else. Maybe he was looking for her violence, maybe he was happy to find it. That was between them. Like a hit of speed. Layered on top of opium, which made them sleep, and dampened everything. Sometimes the next day she’d have left bruises on his face, a black eye, a split lip, it was like a hangover. They loved each other that way, since forever, since before I was born. It exhausted them. Sometimes she said she would leave him but they never left each other, of course they didn’t.

I loved my father, I loved my mother, like everyone does. So what?

I repeat: So what?

From , translated by Lauren Elkin, to be published this month by Semiotext(e).

Constance Debré left her career as a lawyer to become a writer. She is the author of the novels Playboy and Love Me Tender.Lauren Elkin is a French and American writer and translator. She is the author, most recently, of the novel Scaffolding.

April 1, 2025

William and Henry James

William and Henry James. Marie Leon, bromide print, early 1900s, via Wikimedia Commons. Public domain.

When Henry James decided to come to America in 1904 and 1905, his elder brother, William James, was not immediately pleased. William said that while his wife, Alice, would welcome his visit (she and Henry had a firm bond), he felt “more keenly a good many of the désagréments to which you inevitably will be subjected, and imagine the sort of physical loathing with which many features of our national life will inspire you.” There follows an account of how traveling Americans ate their boiled eggs, presumably in hotels and on trains, “bro’t to them, broken by a negro, two in a cup, and eaten with butter.” As a source of physical loathing, this seems a bit excessive: one might linger over William’s attempts to keep Henry’s visit at bay. William’s letter seems more to the point when he notes: “The vocalization of our countrymen is really, and not conventionally, so ignobly awful … It is simply incredibly loathsome.”

William’s discouragement provoked from Henry a declaration of his determination not to be deterred from coming. “You are very dissuasive,” he wrote to William. Henry, in a plaintive reply, noted that whereas William had traveled much, he had not been able to—he not been able to afford it nor to leave the demands of producing writing for money. It’s as if Henry must plead for his brother’s approval before he can travel back to his native land. And yet the pleading is accompanied by Henry’s self-assertion, he’s thought it through, analyzed the consequences. There is so often in their dialogues this deference of the younger brother to the elder, mixed with self-assertion, an insistence that the pathetic younger brother does know what he’s doing. I suppose we might, in contemporary psychobabble, call Henry’s relation to William passive-aggressive. William’s to Henry, though, has a tinge of sadism that we will see take more overt forms. His response to Henry’s desire to travel home is a strange mixture of welcome and repulse, a recognition of their sibling bonds along with the sense that they bind annoyingly, that he’d rather not have his brother around.

William’s wife, Alice Gibbens James, was much more openly hospitable to Henry’s announcement of the proposed visit. She and Henry seem always to have had a warm and understanding relationship. William claimed that marrying Alice had “saved” him—from what exactly, it’s hard to specify. He had many bouts of depression as a young man, and it has been suggested that he suffered from a self-punishing guilt about his masturbation. Yet while married to Alice, he managed to be absent often, trekking in the Adirondacks or traveling elsewhere. Henry apparently remarked on what he thought was William’s neglect of his wife; according to William’s biographer, Henry told his Chicago hostess that Alice was “the finest woman living, only criminally sacrificed.” It’s not clear whether this is simply the comment of a man who never married and understands little of the daily negotiations of a long-standing marriage, or if it speaks of a truth about William and Alice’s relationship. Reading Alice’s biography, one is struck both by William’s psychological neediness and by his frequent escapes from home on various trips. It seems odd to us today, for instance, that William managed to absent himself following the birth of each of his children. And, in general, Alice seems to have borne the brunt of all the child care and household management as well as of William’s demands for sex—his absences seem to have been his way of handling birth control—and his volatile temper.

Alice, as Henry was the first to note, married the whole James clan, and took on its vast responsibilities, including assuming the management of Lamb House when Henry fell into his deep clinical depression in 1910, and then tending to him on his deathbed. One gets the impression that Alice alone was able to understand the brothers in ways neither of them alone could understand each other. When Henry set out on his American trip, he announced that he could not stay with people, that he needed the privacy and luxury of a hotel. He made a few exceptions: Minnie Jones in New York; Edith Wharton in New York and Lenox, Massachusetts; Dr. William White in Philadelphia; the Vanderbilts at Biltmore in North Carolina, for instance. But the main exception was William and Alice, in the house they had built on Irving Street in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and in the rambling New Hampshire farmhouse in Chocorua, New Hampshire, where Henry went upon his arrival in 1904. Cohabitation with William seemed to be without major friction, no doubt because Alice reigned in both places, and also because Henry was a devoted uncle to Harry and Peggy and their siblings.

In the long story of friction, as well as of real affection, between the brothers, William’s seeming judgment that the American continent was too small to hold them both deserves remark. While Henry was in Chicago, William made the sudden decision to depart, alone, for a trip to Greece and Italy, from March through June 1905. He was still abroad when Henry returned to the East Coast from his trip to the Midwest and California. This time, Henry at first stayed in the Brunswick Hotel in Boston, closer to the dentist he was there to see, instead of at Irving Street in Cambridge. William, meanwhile, wrote charming and loving letters home to Alice, wishing she were with him—but he seems never to have considered taking her.

William returned from the European trip on June 11, but then was off again to Chicago on June 28, followed by a trip to lecture to the Summer School of the Cultural Sciences in Keene Valley, in the Adirondacks. So we find Henry staying at 95 Irving Street without William. One would almost conclude that William had had enough of Henry and did not want to cohabit further with him.

***

A similar thought comes to mind when we read the strange story of William, Henry, and the American Academy of Arts and Letters. This was a new organization, sprung from the side of National Institute of Arts and Letters, intended to be something like the Académie française. The original seven academicians selected in 1904 proceeded to elect the subsequent members. Henry James was elected on the second ballot, William on the fourth, in May 1905. But William declined the honor, in a letter in which he characterized the academy, not inaccurately, as “an organization for the mere purpose of distinguishing certain individuals (with their own connivance) and enabling them to say to the world at large ‘we are in and you are out.’ ” William went on to say: “And I am the more encouraged to this course by the fact that my younger and shallower and vainer brother is already in the Academy, and that if I were there too, the other families represented might think the James influence too rank and strong.”

Whatever attempts had been made to pass this off as friendly family joshing, it has a sharp edge of hostility. And as William’s biographer points out, it was not a casual note. William rewrote the letter, making it nastier still: he added “shallower” to “younger” and “vainer” in the final version, as if to put Henry more dramatically in his place. Whatever the closeness of the brothers—and they were indeed close, both citizens of a family in which family ties were of overwhelming importance—the sibling rivalry that must have traced back to childhood was still operative, and still driving William’s psychosocial reactions.

William’s maximal hostility toward Henry transpired in the letter he wrote to him following his reading of The Golden Bowl, which was published in the United States by Charles Scribner’s Sons in November 1904, then in England by Methuen in February 1905. William read the novel during the summer of 1905, and wrote to Henry about it in October. “I read your Golden Bowl a month or more ago, and it put me, as most of your recenter long stories have put me, in a very puzzled state of mind.” He continued “I don’t enjoy the kind of ‘problem,’ especially when, as in this case, it is treated as problematic (viz. the adulterous relations betw. Ch. & the P. [Charlotte Stant and Prince Amerigo]), and the method of narration by interminable elaboration of suggestive reference (I don’t know what to call it, but you know what I mean) goes agin [sic] the grain of all my impulses in writing.” I am not sure what he means by “‘problem’ … treated as problematic”—no doubt the adultery, which a number of American book reviewers couldn’t stomach—though his comment on the method of narration is clear enough, if largely imprecise.

It shows little attempt to understand his brother’s fictional dramas of consciousness, which seems odd, considering his own interest, as a psychologist and philosopher, in states of consciousness. After all, William invented the term stream of consciousness, which doesn’t quite apply to Henry’s work but would to that of many a later modernist. He goes on to say that there is “a brilliancy and cleanness of effect, and in this book especially a high-toned social atmosphere that are unique and extraordinary.” Then comes the stronger censure:

Your methods & my ideals seem the reverse, the one of the other—and yet I have to admit your extreme success in this book. But why won’t you, just to please Brother, sit down and write a new book, with no twilight or mustiness in the plot, with great vigor and decisiveness in the action, no fencing in the dialogue, no psychological commentaries, and absolute straightness in the style? Publish it my name, I will acknowledge it, and give you half the proceeds. Seriously, I wish you would, for you can; and I should think it would tempt you to embark on a “fourth manner.” You of course know these feelings of mine without my writing them down but I’m “nothing if not” outspoken.

There have been plenty of other readers and critics of Henry James over the decades who have deplored the complexities and indirections of his “late manner,” but William does something more than that. He appears to wish to reduce his younger brother to himself, to deny the possibility of another style. The novel he sketches out—one with “vigor and decisiveness” in the action, no “fencing” in the dialogue, and devoid of psychological commentary may be intended as a joke, but it’s a poor one and a hostile one. As for publishing it in William’s name and then receiving but half the royalties—that seems an absolute denial of his brother’s right to an independent existence. All the Jameses could be sharp-tongued with one another, but here William goes beyond intrafamily play. It’s a harsh response to his brother’s masterpiece, a seeming a refusal to try to understand it.

That is what Henry detects in his reply. He begins by appearing to adopt William’s pseudojocular tone: “I mean … to try to produce some uncanny form of thing, in fiction, that will gratify you, as Brother—but let me say, dear William, that I shall be greatly humiliated if you do like it, & thereby lump it, in your affection, with things of the current age, that I have heard you express admiration for & that I would sooner descend to a dishonored grave than have written.” Then he comes to the more serious protest against William’s reading of The Golden Bowl:

But it’s, seriously, too late at night, & I am too tired, for me to express myself on this question—beyond saying that I’m always sorry when I hear of your reading anything of mine, & always hope you won’t—you seem to me so constitutionally unable to “enjoy” it, & so condemned to look at it from a point of view remotely alien to mine in writing it, & to the conditions out of which, as mine, it has inevitably sprung—so that all the intuitions that have been its main reason for being (with me) appear never to have reached you at all—& you appear even to assume that the life, the elements, forming its subject-matter deviate from felicity in not having an impossible analogy with the life of Cambridge.

Henry’s rejection of William’s strictures on his novel becomes a not entirely covert critique of William’s provincialism, his incapacity to see beyond the values of Cambridge, Harvard, and New Hampshire. Which is perhaps fair enough: for all the range and perceptiveness of his writings, and his wide reading of German and French psychologists and philosophers, William’s style, as a writer and a person, seems very much rooted in Cambridge soil, which from early on seemed to Henry unsuited to his longings.

Henry winds up by saying: “It shows how far apart & to what different ends we have had to work out (very naturally & properly!) our respective intellectual lives! And yet I can read you with rapture … Philosophically, in short, I am ‘with’ you almost completely.” It can be argued—and has been—that Henry’s books offer a demonstration of pragmatic thinking and pragmatic ethics in action; the moral dramas of his novels tend to turn on how one treats other people. That William was unable to appreciate how close his brother’s worldview may have been to his own cannot be attributed to stupidity—there’s none of that in either of them. It seems rather to be generated by a kind of psychological blindness that no doubt derives from family dynamics as well as from William’s rejection of his brother’s lack of “manliness.”

One has the impression that Henry spent much of his life dealing with rebuffs from his elder brother, that he was thoroughly used to them and yet continued to be wounded by them. He put an ocean between William and himself yet still yearned to overcome that distance. The scenarios established in childhood don’t die. On the contrary, they persist with the force of unconscious desire, never fully satisfied, by nature never satisfiable, and in this lack of satisfaction a driving force toward further achievement—which certainly characterized the life of both William and Henry—that never brings complete happiness. And never complete harmony between the brothers.

This essay is adapted from Henry James Comes Home , which will be published New York Review Books this month.

Peter Brooks is a literary critic and author of several books of nonfiction, including The Melodramatic Imagination; Reading for the Plot; Henry James Goes to Paris, which won the Christian Gauss Award; and Seduced by Story, which was a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award. He is professor emeritus at Yale.

March 31, 2025

from Lola the Interpreter

Photograph by ZeroOne (on Flickr), via Wikimedia Commons. Licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0.

We make the best and the worst use of time by relegating it to postponement, deferral, waste, irrelevance; we send it out and away from things that can be thought or done; we estrange time from reality and thus from life’s activities; and in the process we either liberate ourselves or find ourselves stranded, and it’s probably the latter.

Just as baboons, ill at ease and querulous as the sun sets, move about restlessly and shout to no effect, so humans in March, the twilight of winter, grow irritable, anxious, and uncomfortable as the long familiar routines of everyday life deplete rather than sustain interest, energy, and appetite. Reality, lacking energy, begins to lose credibility; the past, running out of reality, begins to lose possibility. Lola quickly laughs sardonically when she spots the title of a book on display in the window of the bookshop on Higher Ave. March: A Comprehensive History of Humanity. Universality for Idiots, she thinks. Unity—coherence congealing into a whole—is illusory. Tony van Heuvel, nonetheless, refusing to blink a way out of a state of willed self-deception, gazes out a window into the midground of trees blown by the wind as if expecting to see the perpetual play of time with truth though there’s nothing but mist to be seen between the boughs. With what goals do we engage in introspection? There’s always the grand plenitude to come, the promised comedy when everything comes out, but this is just another labyrinthine day in the life, etc., with fence fibers half buried in rain. The past of the man of the hour recedes by the minute, the past of queen for a day has lost relevance. Her past is only a receding dim version of the woman who repeatedly steps slightly away from the life she has led, leaving dull fragments of it behind. What we have is a sequence of parts that can be unified only (mis)conceptually by an imagination bent only on eliminating details, the devilish essentials that are the sine qua non of reality. It’s only with a pencil drawn over a rough ridged surface that the illusory continuities on which a coherent imaginable life is predicated can be seen. Continuities are lost, only commas remain where long sentences and full paragraphs used to fill some time across some space. Penelope moves among her suitors or Penelope sits by day and again by night at her loom, she is either performing domestic labor or, as one fifth-century B.C.E. Greek philosopher proposed, she projects “an image of the faithful labors of the philosophers.”

A woman is awake, she can’t sleep, no need to know why, she’s restless, wagging, maybe imagining herself giving a speech, speaking out, no need to know the cause or content, it may not be the reason she’s awake, wagging, restless, raging, maybe she woke just to reprimand the night, to whip the horses of the night, never to repeat. Humans may always have similarly hated, raged, enjoyed, marveled, worried, disdained, feared, and loved, not to mention shivered, sweated, danced, wept, sat, pissed, swallowed, laughed, slept, and fucked—we are unbeautiful beasts all of a kind—but given the vast amount that the things that repeatedly press on human thought haven’t changed, isn’t it likely that over time thinking minds have stayed the same? Some ants drown in a toe-deep creek and it’s because of just such incidents that Democritus “developed a thorough critique of the trustworthiness of the senses.” Though we make use of our different senses to coordinate our resulting sensations so as to figure out and focus on what’s present, what’s going on, we can’t similarly coordinate our emotions, our moods. And where anaphora doesn’t naturally occur, we invent it. Wakened by a siren at an early morning hour, I look out the window at two red emergency trucks and, with their flashlight beams playing over the side of the house, five firefighters in black invested with the right to look back at me. Neither ambivalence nor doubt nor uncertainty nor skepticism will secure us any immunity from that. Night: that is the name of the horse that over and over Lola imagines riding through long insomniac hours. Raccoons emerge from a drain pipe into the dark, chortling, giggling.

The quiet light of a returning normal life is interrupted by the roar of nomadic motorcycles—seven—plunging out of Chance Alley, it’s an unexpected event without perceptible inception, it’s suddenly appearing on (or being spontaneously released onto) Flutter Street, where a chancy I, never fully objectified, pulls back. Nothing: nothing though twice yesterday I found myself consciously noticing and noting something, as if in preparation for remembering it. Both times, too, I immediately felt that such noticing was a form of cheating, of forcing memory rather than simply being open to it. Say you are a character encountering a story. Stop the story. Got born. Get a name. The name won’t fit but you’ll have to wear it or go through the hassles—bureaucratic and social—of changing it. So many hassles! Too many homilies! And remember: these aren’t characters but names and names need to be differentiated from both the named and from personifications. Take my word for it: there are no allegories here. Our particular interpreter is looking for ideas to hold provisionally, they’ll be evasive, she’s a subject after vacillation, incoherence, doubt. Where there might be a name, there’s pathos.

Everyday life requires at least a modicum of agency. We gather things that make an appearance, we embellish the quotidian with a sequence of vivid social moments. A young friend tells me the saga of an unfolding multi-mishap housing crisis that continued over the course of the entire first year of her postdoctoral fellowship at a small distinguished bastion of established white life, where the crisis took occupancy of her psyche. Next a young woman, frequently touching her face, frequently pulling both sides of her hair across her cheeks, “shares” confidential information, which is okay, it’s hers to confide, I can only listen. Somewhere lurk the principles of selection determining what I hear, what I remember, elsewhere lurk my principles of description, my principles of narration.

In the (loose and close) grip of ambivalence, one is both deep inside the zone of choice and on the fringes of the conditions and circumstances that demand one. We are often striving to become what we are not, or is it playing that we are doing (play-acting, costume-displaying, lying, wielding ourselves metaphorically) as we struggle not for an ideal but for an alternative? Becoming personable, baby Deli looks up, giggles, wriggles, looks down, and intently squeezes peas, seizing or selecting, three or four in each plump ardent hand. Georgina Gerald Brown is responding—enthusiasm being a social value—to what’s neither false nor true. Here on a key is a haptic fingertip, a cognitive partner in the machinations of the mind, it’s tucked under the nail of an indexical finger that partners likewise with cognition but to different effects. This is a signifier, that the signified—and over there is an observer, a spectator, whose presence has to be ignored. Nearby a person on a “wrong track” passes, erring autonomously; there is no accompanying verse. Think of all the imprecisions (and ambitions) of the language of naming, the language used by those in thrall to eternal strivings and the quest for perpetual self-improvement! An aporia can’t be isolated, it’s not a sticking point but an extension into the temporal interior of an interminable through-zone. Every performance (and all performativity) is tantamount to transition: mended when what grass lift is and slippage slat bough in metal drift if. A falcon is nesting on a parapet overlooking a dream city in a dream not of a falcon but a dream of slow flight, a dream slowly reached—a dream flown to without city sounds, without shouts, without the acceleration of a car on an adjacent street, a train whistle from the distance, a train to another dream or from one. But this is prose, not dream. There is that third acacia on the relatively high hill higher than the sudden hill we pass in the car, that abandoned dump. Suspense is exhausting but inexhaustible—and it is insolent, perhaps because it thrives on the insufficiencies of the present, the untenability of our prospects for the future.

One can’t be a scholar of the future, one can’t learn from it, one can’t even learn about it. You think it’s a man in the distance coming along the country road, but as Husserl remarks, “it might be a tree moving in the wind, which in the gloom of the late afternoon at the edge of the field resembles a man in motion.” We define things by their peripheries, their proximities, the things around them to which they are bound but from which they differ. Trust has little to do with it; we cast out tendrils of interpretation as if with a paranoiac’s perspicacity and lucidity. “You utter fools, you senseless people,” says the Sophocles’s Old Slave in Electra, “do you take no heed any longer for your lives, or have you no inborn sense, that you fail to see that you are not merely close to but are in the midst of the greatest dangers?” To establish the character and value of something; we negotiate with the future, we barter with what we think we see ahead, what we expect to come. We traffic in what we hope for, what we fear, what we can’t finish by ourselves.

***

“Agathon of the beautiful verses is about to set the pegs on which to frame the play.” Here the beautiful Agathon, author of lost tragic verses, is a character in a comedy. Here for a moment and then, time being what it is (whatever it is), we have only his name and rumor with its subsequent commotion. Aristophanes continues: “He is bending new curves for his verses; he is chiseling some bits, fixing some with song-glue, knocking up maxims, making periphrases, wax-moulding, rounding, casting.” The comedian is always in motion, dancing to the staccato beat of disarray—motion is the genius of comedy, its reality. While that beautiful Agathon in his elegance prepares a song long with the legato of catastrophe, Aristophanes laughs. It’s tragedies that unfold in the aftermath of the collisions that cause history, but the grand profusion when everything comes out at the end is sheer comedy.

Five city pigeons fly into the air, driven from their perch under the eaves of a gray house by a homeowner bombarding them with tennis balls. A disheveled man goes by pulling a wagon and shouting curses to the curb and then to the corner store. Brotherfuck mothermouth turd-on-a-rock-in-your-face, do you hear me, do you hear me? Definitely—one should nurture one’s private sensibility (one’s “inner life”). One should deploy it in social spaces, pitch in, speak up, participate in “public life.” You can belong where you are for a moment. When everything gets loud enough—which is to say when sounds coalesce into a din—everything achieves synchrony, orchestration, and synonymy.

All in due course the arid dust in one place receives recompense from incoming rains and heavy floods in another are lifted from grey sodden fields by a dry dazzling wind. For a moment, both feet of justice are on the ground; on the hillside above the path through the park the buckeyes balance pink and white blossoms on clublike stalks. I assume there’s some determinate character to the reality of the moment—something necessary, something causing or compelling things of the moment to be real. Or, rather, to appear. But everything to this point has been the product of guesswork, like improvised masonry done on dry days through weeks of a wet winter or electrical wiring done by an amateur, and no doubt will be long after it. Along the median strip the hardies, the perennials, the continuing, are back: penstemons and sages, poppies and lavender, street people and day laborers. The stoplights flicker; a rock falls onto the edge of the highway—a rock with a pinkish-orange hue close to the color of a fallen peach in dust. Despite all the violence and crime inherent to tragedy, every tragedy also includes innocence. Each character makes its appearance but none are backed by a narrative, nor am “I”—I appear like all the others, unnarrativized, unstoried, on the margins of ambiguity. To live aesthetically—to live in terms of, to live in the contexts and limits of, the phenomenal world (and perhaps interpretations of it)—to live facing outward (without “seizing” or “capturing” or otherwise “possessing” phenomena): this is to live in terms of surfaces. Things surface, thoughts come to the surface, etc. And it’s not just there that we find something as indeterminate as a ricochet, something erratic, demanding decision, something for which we or you or I or she or they or one or he or someone has to take responsibility. In a burst of enthusiasm, I embarrass myself with a burst of enthusiasm. So be it: acts of synthesizing consciousness can produce “complete distinctness of ‘logical’ understanding,” which, however, can “pass over into vagueness.”

In a book such as this (whatever kind of book it is such of), typically the narrator—a given “I”—would have introduced an erotic element—a drive, a yearning so fundamental and unavoidable as to feel instinctual, intuitive: a feeling above all of feeling. But let’s set aside questions of kind, category, etc.—this is not a book in search of a genre, though genres may come searching for it or creep over some of its phrases. There’s no truth to identity. At best it’s subjunctive, not indicative. I pick up a pen—passionately, say—and, not yet even knowing what words will appear, I begin to write: subjectivity (personality) emanates from intoxication.

The phenomenal world is what there is—material particulars, happenstantial circumstances, everyday life—why speak of futurity, a metaphysical imposition, an empty category into which anything might enter but nothing has? Perhaps we do so because it offers prospects of what’s ahead far from the importunate past and—this may be key—without promises. The forces of eros, the barbs and bewilderments, the obliterating passions and (dare we say) pulsations—the relentless throbbing and irritable insistences—of eros (and let’s not limit eroticism just to sex) may be ubiquitous, they may be banal, but let’s credit them with pushing us along, taking us, for example, on yet another “intellectual promenade.” “With stopovers”—nominal, adverbial, prepositional, participial. Street drunkenly twig for gab compatibly starch. Every word is an iteration, each testing for something—accuracy? insight? truth (whatever that might be)?—seeking “successively closer approximations to the solution of a problem.” And there it is: skepticism makes too many demands. Lola is never overly eager to join together things that have no connections and with that to create a story pitting fate against fact, but what of clowns, tightrope walkers, a lion tamer, a parade of elephants? I don’t buy that they’re shadow forms under a big top—they’re feeling points, they’re proximities. Animated by sudden, worldbound, outfacing feelings, Lola laughs with both hands in the air: here’s to the raptures of proximity! Names are given heavy with hidden insistence generating an epistemology of given moments in and of the phenomenal world, the given and apparent world of the historical present, said to be a system, said to prohibit off-cycle harvests, said to be in the eye of a temporal maelstrom, said to be the last thing basking in sunlight at the end-time. Jewassi Zhdanov Jones swings right from the last daylight on Chant Street into the white-walled bar, she’s quickly crafted, or, since this is a social occasion, she’s already sitting at a table with Jamie Brecht Weiss, Freya Cyprian Slight, Rosie Consuela Hassan, and Lola: she’s quickly performed, immediate as a being in a continuous take of eternal duration. But it’s not as if everyday life were forever static and ahistorical—as if a single scoop of chocolate ice cream on a sugar cone were always to cost a dime, humans were to forage forever in hills and on plains to the edge of the terrestrial flat finite disk, or someone first called Silly couldn’t later and emphatically be known as Priscilla Salter Blaine with Pris banned flat out. Let’s imagine a city pigeon in harness presented as an allegorical image captioned “The Life of the Mind,” a punctum perceived amid “tangents and repetitions and intersections”

When doubt recedes, they say, it’s death that approaches to drive a wedge between meaning and its trappings, its contradictions, its digressions, and confusions as well as its minnows, fern spores, ladles, architectural renderings of commercial towers, stained glass windows, manifestos, curries. Of course one can imagine death as rapacious, greedy, an impatient predator, a scavenger charged with clean-up, or, then again, as a supreme and theatrical deity, over inked or underground. Well, as a skeptic once put it, it’s wisest to follow the principle of the one no more than the other, which is as applicable to interpretations of allegory as to personifications of death. The thought—a proposition, or perhaps a phantasm drawn from an impression—serves a sentence. There isn’t all that much distance between the prospect of death and the concept of beauty. A ridge, a sunset, a blossoming redbud—all are beautiful and, in their beauty, they assert their distance from us, but even today’s unvarying dull sky maintains distance, as if to make beauty itself inaccessible. The rain has stopped, low to the ground there’s fog—Floka pulls the hood of her raincoat back, Tasha her dog is off-leash and sniffs at dripping trees, wet hummocks, soggy soil under dark amorphous leaves.

On a battlefield (whether literal or metaphoric), humans encounter the problem of humanity: what is the value to being human? Call a character an exasperated chemist, Max Marie Ritter, and Max Marie Ritter will have retorts to clean, carbon to consider, big pharma to advise, and mockery to make of boy groups, mayonnaise, house cats, and conspiracy theories. Characters are necessary to human microhistories, but those histories are of what has happened and is happening and not revelations of intelligent inevitability nor milestones along a road to progress. Along with the plethora of interconnected phenomena come experiences of disconnection. Why isn’t it always summer? Pilar Piana Fleye isn’t asking a question, she’s complaining, demanding rays of attention. You never know why, says Milly Willis. And about this Milly Willis is right: those who love logic are apt to love lies. What case, then, can we make for human understanding?

From Lola the Interpreter , to be published by Wesleyan University Press in October.

Lyn Hejinian (1941–2024) was a feminist avant-garde poet and scholar. She was the author of numerous books including, Allegorical Moments: Call to the Everyday, and the bestselling, My Life and My Life in the Nineties. She was co-founder and co-editor of a number of publishing ventures and literary journals including Nion Editions, FLOOR, Atelos, Tuumba Press and Poetics Journal.March 28, 2025

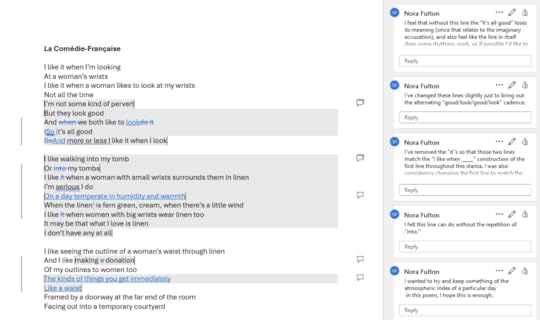

Making of a Poem: Nora Fulton on “La Comédie-Française”

For our series Making of a Poem, we’re asking poets to dissect the poems they’ve published in our pages. Nora Fulton’s poem “La Comédie-Française” appears in the new Spring issue of the Review, no. 251.

How did this poem start? Was it with an image, an idea, a phrase, or something else?

I wrote this poem in September 2024, but it was a reflection of a three-day seminar I’d attended the month before. The seminar, organized by two brilliant friends, Matt Hare and Sam Warren Miell, was about the French film production company Diagonale, and focused on the work of its central director, Paul Vecchiali. Of the films we watched, Encore and Corps à cœur were especially on my mind while writing. Both are romantic melodramas, but they undercut that tendency in lots of interesting ways—I think I find them moving precisely because they undercut that part of themselves. The seminar focused on the way that Diagonale functioned as a collective of people who would take up different roles in each film, both in front of and behind the camera. This was likened to the troupe established by Molière, to which the title of this poem refers.

Were you thinking of any other poems or works of art while you wrote it?

At the time of writing I was thinking quite closely alongside the poetry of the Swiss Francophone author Philippe Jaccottet. I had begun reading and translating his early poems during the summer, mostly just for myself—I was working on them between sessions of the seminar, and continued this work into the fall. I was particularly enamored with the way Jaccottet uses hesitation as a formal device in both his poetry and his journals (the incredible translations of which, by Tess Lewis, I was devouring during these revisions). It’s not easy to write hesitation without seeming either arrogant or naïve. How can one hesitate in the field of language, at all, anyway? But Jaccottet finds ways to write through a reticence that manages to fully surrender to knowing that it has no idea what it is reticent in the face of, as in his journal entry for May 1971. “I write exactly as I have said one should not write. I am not able to grasp the particular, the private—the exact details escape me, slip away; unless it is I who shies away from them.”

Where did you write this poem?

In the front room of my apartment in Montréal. Right now it looks like this.

Do you have photos of different drafts of this poem?

The first version of “La Comédie-Française” that I submitted to the Review went through a very heavy initial edit, to the point that that draft no longer seems relevant to the form the poem eventually took in print. The essence of that first edit was an incredibly perceptive removal of various avoidant comedic detours, which pared the poem down to central gestures I hadn’t noticed on my own—a pivoting away from and back into lyric transparency, and an attempt to make vernacular speech do something interesting aurally. I can supply two later drafts near the end of the editing process, where I feel like I found some solutions to the many problems I’d created for myself.

In this draft (which I think was the third), I’m revising a version sent back to me from a previous editor, so you see only my responses to their changes. The “On a day temperate …” line had been cut initially, and I felt that something beyond the subjective—some register of external specificity—was needed in such an internal piece, so I added that back in. There had also been many cuts made to the third stanza, and as a result I thought that part of the poem lacked coherence, so I restored lines there as well. I also cut articles and prepositions where I could, some of which were later reinstated—maybe I got a bit zealous after how productive the paring down had been. The penultimate line of “Shade, that is” had originally read “More shade that is”—it had been cut in the first edit, but was reinserted here. While the repetition of “more” originally came from the spirit of self-correction the poem begins with, I no longer felt that it needed to end in that register, and wanted to temper the pull of the idea that it is the shadows that grow close, rather than anything else.

A couple of drafts later, it’s the fourth stanza that has become the issue. By that stanza, I wanted the gaze of the “I” to have traveled from tranquility and light to darkness and noise, and that movement was not easy to render without overwriting. The stanza’s first line shifts from a feeling of “I didn’t get to” to a feeling of “we didn’t get to”—before that, it was a feeling a “you” avoided, and in this draft the pronominal attribution is removed altogether—the feeling is said to be impersonally “avoided via musical number.” In the published version, it is again a “we” that is doing the avoiding. Surely there’s a kernel of inane psychologism in these decisions on my part, but I also think there was a real question of where to go from the hyperfocus on the “I” that the poem starts with. It has to go somewhere else. In the third stanza the “you” functions as a universal “you,” unmediatedly perceiving an outline and immediately knowing what it is an outline of is said to be something “one does” in general. Then in the fourth stanza, the “you” shifts to something more specific, but is still trying to continue talking about that universal. The “I / you” dynamic is hard to find an exit from, and probably I didn’t quite accomplish that here. But neither did I feel that simply leaving out pronominal attribution would be a solution— that would feel cheap to me. So I went with a “we” that could be both a container for the “I / you” and for the generality that is implicit in the idea that something like linen could be something like an index of something like women.

Also, that “I’m not some kind of pervert” line got cut. Ah, well.

When did you know this poem was finished? Were you right about that? Is it finished, after all?

I revise a lot. Way too much. If I could, I think I would go back to every book and poem and essay I’ve ever published and touch them all up, so they accord with where I’m at in the present. Sometimes that touching-up is just alternating between two or three or four changes, and one of them occasionally strikes you as a novel solution because you’ve forgotten you’d already tried it, just as you had with all the others. But is the finished version then the poem, plus the oscillation around each such point of indecision? I don’t think so. That’s why Jaccottet’s hesitation interests me—revision is basically just hesitation. But the goal is to make something that’s revised/revisable and true. I think that poems are finished when the poet’s attention finally wanders away from them and onto some other revisable thing. Which means, they’re finished when you don’t hesitate in your looking back on them.

Do you regret any of these revisions?

I do wish I could have found a way to keep some element of the “I’m not some kind of pervert” line. The idea of popping out of this melodramatic lyrical mode to give a proviso like that still makes me laugh, and usually something that makes me laugh in a poem is something I want to preserve. When I was writing “La Comédie-Française” I had in mind the limits that are placed on the possible articulations of the desires of women like me—limits that we put on ourselves, too. I ended up cutting that line based on editorial feedback, and I consoled myself in thinking that the poem as a whole could be my response to that idea. But, from a certain point of view, writing this piece could be my way of putting it back in.

Nora Fulton is the author of three books of poetry. Cuckoo’s Low Reel is forthcoming from Hiding Press this spring.

March 26, 2025

Tracings

At center, the author with her father and her grandmother. Photograph courtesy of Sarah Aziza.

Occasionally, when we were small, our father spoke to us of geography.

Daddy is from a place called Palestine, he said, in a lesson captured by my mother on the family’s camcorder. In the footage, my father sits in a small rocking chair, brown eyes intent, a little shy. My younger brother and sister are absorbed by the array of blocks on the floor, but I am close to my father’s feet, my fluffy blond head thrown back, mouth pink and agape. He holds up a globe, his fingers sliding toward a sliver of brown and green. He tilts it toward me to reveal cramped lettering: Israel/Palestine.

I hop up to look, my nose nearly skimming the painted plastic as I squint at the hair-thin ink. I am vaguely aware of a thing called countries, loosely grasping that these are places full of people that are like—but unlike—me. There is no mention, today or any day that I can recall up to that point, of the first half of that forward-slashed name, that thing called Israel. There are no tales of shed blood, no wistful tributes to a lost homeland. My father simply hops his fingers, jumping decades and tragedies. Due south, he points to an orange oblong slab of land. That’s Saudi Arabia. That’s where Sittoo lives. My father uses the فلاحي word sittoo—honored lady—our dialect’s term for grandmother. I squint again, trying to see her.

My grandmother, like these countries, feels important and vague. It would be one year before she came to live with us and two years before we uprooted and moved to Jeddah, her adopted city by the sea. In our lesson, my father did not linger, did not try to bridge the difference between Jeddah and Palestine. Instead, the video shows him smiling, rolling the world to my left. He lands on a green sprawl labeled the United States. His finger taps another dot, Chicago, which clings to a lake shaped like a tear.

And here is where we live, my father concludes, his voice a flourish. Impressed by the blue distance between there and here, I blurt, Woooooah. Those are … those are two faraway places! My father looks up at the camera, his face twitching with repressed laughter. That’s right, habibti, he replies, trying to match my seriousness. The lesson ends here. I have enjoyed the attention of my father, playing with this ball called the World. But afterward, I remain just as bewildered by two photos hanging down the hall.

At the far end of a row of family portraits, these two were smaller than the rest. Daily, I passed by them, trying in vain to avert my eyes. Each time, I failed, back of my neck pricking as I raised my head to stare. The first photo is small, its frame a cheap imitation gold. Inside floats a black-and-white image of a barefoot little boy. He squints in long-gone sunshine, a crease in the photo cutting a furry line above his brow. He bears a striking resemblance to my brother, yet his wary eyes defy intimacy.

I asked my mother, uneasily, about this stranger. She informed me that this boy was my father, standing in a place called Gaza. A name with serrated edges, a word I’d not hear again until years later, buzzing on TVs. Her explanation ended there, and I felt with strange certainty that I was not meant to ask more. Instead, I studied the images—the sand and debris at the boy’s feet. Jagged shadows, bleaching light. The whole scene left me feeling both lonely and alarmed.

The second photo was better preserved, and more ominous to me. A black-and-white portrait of the same small boy with his mother, posed unsmiling side by side. The woman only vaguely resembled the grandmother I would come to know. Still in her thirties, her cheekbones were full and smooth, her thick black hair tied in a loose ponytail. She unnerved me with her dead-forward stare, the grim line of her mouth. The boy tilted toward her, regarding the camera skeptically, as if ready to defend.

These photos jarred with the others on the wall. The rest were poised, inviting, blooming from sepia to color. Shots of my mother’s childhood: a blond girl in bobby socks. A picture of her own mother, a woman with coiffed hair, hands resting on a harp. Bright photos of our young family, taken in a Kmart studio against a blue-cloud wall. My imagination roamed easily inside these frames. But I passed my eyes over the corner that held my father and his mother. Looking at them directly left me cold, swimming in something I couldn’t name.

***

My grandmother, a young woman in sixties Gaza, woke often with a thudding chest, the night tangled in her hair. With my young father in tow, she sought solace from neighborhood women. One read meaning in coffee dregs, peering into small porcelain oracles. Another, Sheikha Amna, offered prayers and protective charms to secure the younger woman’s fate. These women granted my grandmother story in the chaos of exile, reason and agency inside loss. But later she ceased searching for such solace. قدر الله—in matters of fate, it was best to contend quietly. The blue plumes of her bakhoor wafting wordless, heavenward.

In the realm of records, her trace has always been slight. Born without a birth certificate in the days of British rule, her name was first written in 1955. A UN worker made the inscription—once in English, once in French—and handed her the paper slip. Her name, a token traded for sugar and wheat, in languages she couldn’t read. She would have been roughly thirty then, a refugee of seven years, mother to a daughter and three sons.

Before, in her Palestinian village of six hundred, names were known by heart. She was bint Mohammed al-Mukhtar, ibn Yousef. Her lineage, a chain of masculine names, a tether to time and place. Her town, ʿIbdis, first appeared in Ottoman files in 1596, and may date to the Byzantine period between the third and sixth centuries, as Abu Juwayʾid.

The Ottoman officials in ʿIbdis marked down thirty-five households that year, not bothering with names. Their interest was in dunum, the rich fields yielding wheat, barley, and honeybees. Later, the villagers added grapes and oranges alongside olives, chickens, and mish-mish. Hundreds of towns like ʿIbdis dotted the rolling countryside. Each had its defining feature, preserved in stories and poetry. ʿIbdis’s boast was its jamayza, the stately sycamore tree.

Horea was the name given to her when she was born. حورية, easy to mistake for حرية—freedom. Sometimes, I wish حرية was her name. The meaning of حورية is not fixed but hovers around beautiful woman. Sometimes translated as nymph, a word found centuries back in poetry and Qurʾanic verse. In English, it can also be rendered as dark-eyed beauty. Sometimes, virgin of paradise. Some hadith, with a hint of colorism, describe a woman so gorgeous her flesh glows translucently. Is this what makes an angel? Something desired and vanishing?

Yet her girlhood was a sturdy-bodied thing. She was daughter of the mukhtar—chosen one, a mayor of sorts, a man appointed to lead village affairs. For her, mother was multiple. Horea was raised by her father’s several wives; then, after her father’s death and mother’s remarriage to a man on the Gazan coast, she was tended by a sister-in-law. There, Horea’s world was woven of half siblings, cousins, and the guests her brother Fawzi entertained.

Like most other village girls, she was never sent to school. Instead of holding pencils, her fingers grew deft at taboon dough, spark-quick as she flipped white-bellied bread over flame. As a young wife, she carried lunch daily to her husband in the field. Passing neighbors on the way, they embroidered greetings in the air. She set down the basket of bread at her husband Musa’s feet. May Allah give you strength. Receiving, he said, May God bless your hands. After eating, she yoked her afternoon to his. Together, they worked the land until evening called them in.

***

These were the days she later kept tucked inside her, hidden from my father and from me. Horea embalmed her childhood in silence, ʿIbdis shrouded in vague myth. My father would not glimpse this history until decades later, as Horea led him through its ruins, the past spelled in scattered stone. His timeline began in Deir al-Balah, a city in Gaza noted for not sycamore but its date palms. He was born there in 1960, his birth registered by the Egyptians who, in 1948, replaced British occupiers after halting Israel’s southern advance. On his birth certificate, ʿIbdis hovers in the white space around the words GAZA STRIP.

Horea welcomed her fourth and last born, Ziyad, in a UN clinic alone. Her husband was four years deep in ghourba, a post-Nakba economic exile cobbling a meager living in the Gulf. She carried her newborn home on foot, her steps jaunty, jubilant. With Ziyad, there would now be four of them sharing the two rooms Horea had built on an unused lot of land. This, a permanent makeshift shelter after months of waiting for NGO housing. The only furniture stood in the sand outside—an old table her second-born, Ibrahim, used as a desk. He was the family’s brightest, with dreams of medical school. To its left, an area for kneading dough and a banana tree that refused fruit.

Like any child, my father was born to trust. Gaza was Falasteen was home was the world. Ziyad loved the small path his days carved, barefoot, between his mother’s lap and the beach. Mornings, he woke to the coo of pigeons, a flock Horea raised and cooked on Friday after prayers. At these meals, he jostled his brothers for a double portion of meat. Above him, history webbed, conjured in the words of Horea and her guests. From time to time, he heard a moan slip from one and caught a chill. He glanced up to see his mother’s head shake, her shoulders slack. But these were only passing, distant clouds. ʿIbdis, war, and even your father—seldom spoken directly, these words had no bodies, no weight. With before locked away, he did not see his life as aftermath.

There are kinds of love that stop language in its tracks. Perhaps she held back ʿIbdis’s name to save it from the past tense. An absence spoken gathers mass, asking the body to bear it twice. Maybe her silence was a refusal, a declaration that grief should not be her sons’ inheritance. In the end, survival is a language, a logic all its own.

Yet ʿIbdis needed no speaking; it echoed in everything. It flickered in the eyes of her cousins as they circled lost acres in their heads. It lived in the sturdy music of their dialect, consonants like hilltops, memory tucked inside تعبيرات. It hovered in the taste of bread, baked from UN-issued flour. The flat sameness of its texture recalled how the dough in ʿIbdis rippled, grainy with hand-milled gamah. Each bite a morsel of the months past—rain or dryness, farmers’ worry, hands plucking, then grinding kernels of gold.

This essay is adapted from The Hollow Half , which will be published by Catapult in April.

Sarah Aziza is a Palestinian American writer and translator. Her journalism, poetry, and nonfiction have appeared in The New Yorker, The Baffler, Harper’s, Mizna, the Intercept, the Guardian, and the Nation.

March 25, 2025

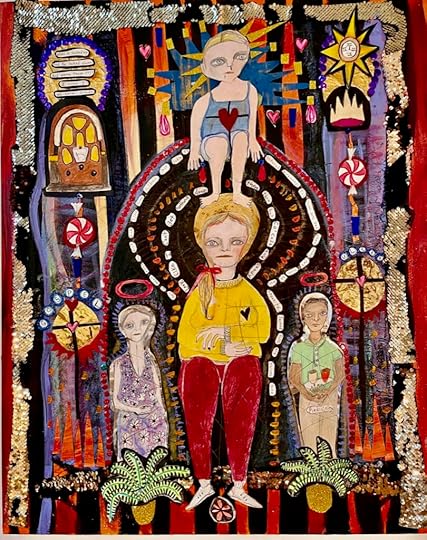

Happy Hundredth Birthday, Flannery O’Connor!

Blair Hobbs, Birthday Cake For Flannery, 2025, mixed media on canvas board, 30 x 24″. Courtesy of the artist.

A painting in Blair Hobbs’s new exhibition features a cut-out drawing of Flannery O’Connor in a pearl choker and purple V-necked dress. She’s flanked by drawings of peacocks and poppies; a birthday cake on metallic gold paper floats above her head. It is titled, like the exhibition, Birthday Cake for Flannery. The number 100 sits atop the frosting, each digit lit with an orange paper flame—marking O’Connor’s hundredth birthday, today, March 25. Glitter and sequins, gold thread and fabric scraps everywhere.

The image is candy to my eyes. I grew up in a stripped-down fundamentalist Protestant church—think Baptist but with a cappella singing. Violence and grace, sin and redemption, idolatry and judgment: When I read O’Connor’s stories for the first time, in high school, I recognized her religious concerns as my own. Fifteen years later I moved to Lookout Mountain, Georgia, where O’Connor’s Southern milieu—backwoods prophets, religious zealots, barely concealed racism and classism—was my literal backyard. I raised chickens in homage to her, then repurposed the coop as my writing studio, where I drafted a collection of stories wrestling with Christianity and sexuality in the American South.

Hobbs, who lives in Mississippi, has been making collage art since she retired from teaching at the University of Mississippi. Her first show, Radiant Matter, was an exploration of the ways her body underwent transformation during treatment for breast cancer. Birthday Cake for Flannery is her second series of collage paintings. Last month I drove from my current home in Chattanooga to Atlanta to see the seventeen paintings in the show. They weren’t installed yet, but Spalding Nix, who owns the gallery, and Jamie Bourgeois, the gallery director, hosted me for a preview.

Jamie unwrapped the paintings one by one. Every canvas—plus one creepy little sculpture wrapped in illuminated wire and encased in a thumbtack-lined shadowbox, meant to evoke the “mummified Jesus” in O’Connor’s novel Wise Blood—is an exuberant explosion of color and found materials illustrating O’Connor’s best-known stories: “Revelation,” “A Good Man Is Hard to Find,” “The Displaced Person,” “A Temple Of The Holy Ghost,” “Parker’s Back,” and “Good Country People.”

“Give Her Leg Back,” from “Good Country People”, 2025, mixed media on canvas board, 20 x 16″.

Hobbs draws her characters in graphite and ink and fills them in with paint and colored pencil. She cuts them out and glues or sews them onto painted canvas. And then comes the bling. “O’Connor often writes the sun and sky,” Hobbs writes in her artist statement, “so I wanted the pieces in this show to have an extra dose of shine.” The collages shimmer and sparkle as if backlit: broken Christmas ornaments, rhinestones, bronze dust, gold leaf, metallic tape, silver duct tape. Hobbs also uses embroidery thread, mulberry paper, burlap, tacky plastic placemats, even candy wrappers and paper dolls. Handwritten quotations from O’Connor’s stories and letters are glued onto the final images, a nod to the word art integral to Southern “outsider” artists such as Howard Finster, Nellie Mae Rowe, and William Thomas Thompson.

There is, for the viewer, an I-spy delight of discovery: the better you know O’Connor’s stories, the more you see in each piece. Here’s young O. E. Parker from “Parker’s Back,” who was “heavy and earnest, as ordinary as a loaf of bread.” In Hobbs’s rendering, Parker’s head is an actual loaf of bread wrapped in plastic, with the words Yeasty Boy pasted above him. A second painting shows the adult Parker with Jesus’s face tattooed on his back, stitched through with gold thread and sequins. The letters G, O, and D surround Parker’s head.

“You’re a Walking Panner Rammer,” from “Parker’s Back”, 2025, mixed media on canvas board, 40 x 30″.

Two canvases are based on what is arguably O’Connor’s best-known story, “A Good Man is Hard to Find.” The first depicts the young “cabbage-faced” mother, her head a literal cabbage, thickly veined. Pieces of broken glass, red, surround her body—reminiscent of the family’s car wreck (and the ensuing bloodshed in the woods). A charcoal revolver the size of the mother’s torso is pointed at her head. To her right is her daughter, June Star, a vintage paper doll covered with the words June speaks as the Misfit’s crony leads her into the woods: “I don’t want to hold hands with him, he reminds me of a pig.” In the other “Good Man” painting we see the grandmother’s cat, Pitty Sing; “Bailey Boy” in his yellow shirt with blue parrots; the grandmother in her sailor hat with white violets on the brim; and the monkey in the chinaberry tree. Above these characters is the cut-out title The Misfit. The criminal himself is absent. This omission produces the same vertiginous dread the reader feels on page one. The Misfit is everywhere and nowhere—until he shows up.

My favorite image is from the carnival scene in “A Temple of the Holy Ghost,” in which an androgynous human with a mustache lifts their dress to reveal the word IT covering the crotch. “It was a man and woman both,” Susan explains to her younger cousin. Above this figure, an open-mouthed rabbit spews forth six babies, evoking the child’s claim to have seen “a rabbit have rabbits.”

Whimsy, humor, glee: these were the words that came to mind, on first viewing. But the glitz and wit are a ruse, belying the deep suffering and darkness beneath the surface.

***

Mary Flannery was born on the Feast of the Annunciation, the day marking the angel Gabriel’s announcement that Mary would bear the Christ child. O’Connor’s Irish Catholic parents, Edward and Regina, bracketed this festal birth by having her baptized on Easter Sunday, three weeks later. Each time I’ve visited O’Connor’s childhood home in Savannah, I’ve been moved by the Kiddie-Koop crib beneath the window in Regina’s bedroom, facing the twin green spires of Saint John the Baptist, the O’Connors’ church. The “crib” is a rectangular box with screens enclosing the four sides and the top. The cagelike design—a chicken coop for babies, really—was meant to allow mothers to leave children unattended. “Danger or Safety—Which?” one Kiddie-Koop advertisement read.

I can’t help picturing O’Connor as a toddler growing up “in the shadow of the church,” literally and figuratively, standing in the Koop and peering through a double scrim of screen and windowpanes. When her eyesight failed, she began wearing thick corrective lenses—another layer of remove. And when she contracted the lupus that killed her father, her body itself became a kind of cage. “The wolf, I’m afraid, is inside tearing up the place,” she wrote to her friend Sister Mariella Gable one month before her passing at the age of thirty-nine.

There’s no one like O’Connor for writing the body. With Dickensian specificity (“I have a secret desire to rival Charles Dickens upon the stage,” she confided to a friend) she renders her characters visible, incarnate both physically and metaphorically. For O’Connor, if we are collectively the body of Christ, every human is implicitly the site of both suffering and transformation.

O’Connor also maintained a firm belief in the Eucharist as analogic: a place where the material and immaterial, time and eternity, merged. “If [the Eucharist is] a symbol, to hell with it,” she famously said. A devout reader of Thomas Aquinas, O’Connor would say that this way of seeing was “sacramental”: often in her fiction, signifier and signified become one.

This sacramental vision infuses Hobbs’s work as well. The mother’s face isn’t just cabbage-like, it’s an actual cabbage. Mrs. Turpin in Hobbs’s “Revelation” series isn’t hog-like but a warthog with a human face.

“Look Like I Can’t Get Nothing Down Them Two but Co’Cola & Candy,” from “Revelation”, 2025, mixed media on canvas board, 30 x 24″.