The Paris Review's Blog, page 21

October 8, 2024

My Enemies, A–Z

Ann-Margret in Tommy (1975). Screenshot by Molly Young.

A list of all my enemies, in alphabetical order.

ADMIN

All the tasks I dread because I’m too weak or lazy to (a) find a way to not do them or (b) use my imagination to render them interesting.

BELATEDLY LEARNING A FOREIGN LANGUAGE

Studying a new language when you’re thirty-seven is an unbelievably inefficient use of time. It takes me weeks to grasp what a five-year-old child could pick up without even trying. This isn’t true of anything else I do in my spare time, like gardening or baking. I could crush a five-year-old’s learning curve in both of those things.

When trying to speak a foreign language I am always catapulting myself out of a frying pan and into a fire. Last year, in Mexico, for instance, someone asked why I wasn’t speaking Spanish and I replied, “Because I’m afraid I will accidentally be rude”—except what I actually said was “Because I’m afraid I will accidentally become horny.”

COFFEE HEART

Some call it tachycardia. The New York Times named it “coffee heart” in a 1905 article with the fantastic title of “SMALL BOY HAS ‘COFFEE HEART'” and the subtitle “Child of Eight Is in City Hospital Slowly Regaining Health. HEART BEATS TOO FAST. Muscle Was Wearing itself Out — Drank a Dozen Cups a Day.”

The article is about an eight-year-old named Johnnie Murphy, whose heart was apparently beating at “twice the normal rate” after its owner got into the habit of drinking nine to twelve cups per day. A suspiciously timed mention of the coffee substitute Postum at the end of the article raises the likelihood that the whole thing is sponcon, though there’s no way to be sure.

CONSPIRACIES TO ROB US OF OUR DIGNITY

They’re everywhere. Too numerous to list. And growing by the day.

DEPRESSION

In one of his letters Henry James refers to depression as “the azure demon.” An interesting color assignment, azure.

EUROPEAN CLOTHES DRYERS

Not all of them, obviously—just the two most recent ones I happened to meet. Both machines were programmed to be eco-friendly, which meant they automatically sensed when clothes were dry (meaning extremely damp) and stopped tumbling. If I restarted the dry cycle, I could fool them for one to four minutes before they were onto my tricks and shut themselves off again.

FDA FOOD DEFECT LEVELS HANDBOOK

In theory I worship this government website, as I admire anything that is humble in presentation yet vastly utile. But in practice it has undermined my lust for such delicacies as pitted dates and potato chips. And what is an enemy but something or someone who steals your lust for living?

What the site does, helpfully, is share the FDA’s guidelines for how much of a given contaminant (mold, rodent hair, parasites) can be included in a given food item (pineapple juice, macaroni and noodle products, canned tomatoes) before it exceeds the threshold of acceptability. Meaning that, thanks to the FDA, you can gobble your Skippy safe (“safe”) in the knowledge that it contains fewer than thirty insect fragments per hundred grams. Don’t look at the entry for Maraschino cherries.

HARSH VERBIAGE

All sorts of pain can be contained in the name of a unit. For example, to be alone is not a bad thing, but to be a “party of one” is awful.

JELLYFISH LARVAE

To be clear, mature jellyfish are not an enemy. Whether it is an ethereal comb jelly basking in the shallows or a hubcap-size lion’s mane bobbing through hurricane waves, the phylum Cnidaria is one batch of organisms that puts man-made attempts at compositional beauty to shame. That said, the larva of a certain jelly—I haven’t pinpointed the species other than “some bastard who populates a specific point break on the western coast of Mexico”—has a practice that elevates it to the status of enemy.

The swarming larvae are invisible and harmless if they happen to brush up against a human arm or leg. However. If they work their way into, say, a bikini top or pair of trunks, they will rebel at the presence of friction and lash out in a manner that feels like a million microscopic volcanoes erupting. When you paddle tearfully back to shore and rip off your swimsuit you will find that the larvae have left a perfect blistering outline of where your swimsuit once was. Now that I type this, it occurs to me that I’m describing an act of comic heroism, not villainy. When it comes to jellyfish larvae, the enemy might be Me.

LOOKING THINGS UP ONLINE

Also known as “having a bad memory.” The real problem with googling every tiny query that arises is that it has caused the cost of an answer to plummet. All you have to do to is type, e.g., “Is a porpoise a dolphin?” or “What does ethodological mean?” into your phone and wait one instant for the information to arrive. And then, having paid so little, you proceed to forget whatever you learned almost in real time.

NAUSEA

The lowest form of mindfulness.

OTITIS EXTERNA

A stunning name for a crude antagonist.

PODCASTS

In truth I love podcasts. I love having voices piped into my ears, love soothing my nerves with gentle chatter. The only problem is that if I’m not alone with my thoughts … I tend not to have them.

PROCTALGIA FUGAX

Proctalgia fugax sounds like the name of a Thomas Pynchon character or a parasitic fungus but it is neither. It’s a truncheoning pain that occurs in the lowermost back area during periods of stress, anxiety, or pregnancy. Proctalgia fugax brought itself to my attention during a recent pregnancy. I wish nothing would ever “bring itself to my attention.” Only bad things do.

QUEST DIAGNOSTICS

In most cultures it is considered polite to make eye contact with someone before you exsanguinate them.

[REDACTED]

This entry is censored because it is the name of a person. For all of last year I wished him harm. More recently I’ve been wishing I could stop wishing him harm … which is wonderful progress.

SPREE (WORD)

Used almost exclusively in the contexts of crime and shopping—but why?

T-SHIRTS THAT SAY WHERE THE WEARER ATTENDED COLLEGE

An objectively uncool category of clothing.

UNISOM

The only over-the-counter sleeping aid that renders me unconscious, but at a steep cost: it thwarts dreaming. Sleep without dreams is hardly worth it. I do enjoy thinking of the name Unisom as a portmanteau of Unified and Somnolence, as though the tablets might work by consolidating all of one’s disparate torpors into a dense nocturnal block.

WRITER (IDENTITY)

If I’m honest, I don’t know why my brain puts certain words in a certain order. One day I will get worse at doing so, and I will continue to get worse until eventually I stop, and that will have been my career.

Molly Young is a book critic for the New York Times.

October 4, 2024

Bernadette Mayer on Her Influences

Photograph of basalt by Marek Novotňák. Licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

The first big influence on my writing was Nathaniel Hawthorne. My teacher in senior year of high school had written her doctoral thesis on The Marble Faun, if you can imagine that—and she was a nun! I went to one of the bookstores on lower Fifth Avenue in Manhattan and bought a complete Riverside Editions set of Hawthorne’s writing. Later I added a volume, Septimius Felton; or, The Elixir of Life, two volumes of Nathaniel Hawthorne and His Wife, and Twenty Days with Julian and Little Bunny. I had become addicted to his long, elegant prose sentences, which I studied and even diagrammed; a habit as old-fashioned as nuns. If you read the introductory essay to The Scarlet Letter, “The Customs House,” you will see what I mean. In it Hawthorne says that Hester Prynne became a social worker. As far as I know, Hawthorne did not write poetry, but he was an excellent candle-waster, in more ways than one. His writing made it clear that words have a magical quality to take you to another sphere but then you see that it’s only a book you are holding. I already had synesthesia in the form of seeing letters as different colors, so in many ways I was grateful to the author of The Scarlet Letter. Perhaps it was Hawthorne who inspired me to see prose as poetic.

Next come the Steins: Gertrude, Albert, and Wittgenstein. I’ll begin with Ludwig Wittgenstein. If there is a book by a philosopher about language, you’d better read his. You might discover you are writing in a private language: or that the color red means something to you and something else to others. Here’s a little poem by Wittgenstein:

Look at a stone and imagine it having sensations

[. . .]

I turn to stone and my pain goes on

Wittgenstein points out, or seems to, that one can know what somebody else is thinking but not what we ourselves are thinking. But all philosophy is written or spoken in words or thought in words. Of course, the idea of whether we think in words has not been answered. Deer don’t talk to themselves, but they might think in words and not know it. Around this time, Wittgenstein says, in parentheses: “(A whole cloud of philosophy condensed into a drop of grammar.)” Sounds that no one understands might be called a private language. Talking and thinking are not the same. But what of writing? Carl Safina, a writer on animal communication, says that if a lion came up to Wittgenstein and said something, it would be hard not to know what it meant.

Was the telephone book a book that had meaning? Is there a telephone book now? What if I changed my name to Bernadette Telephone Mayer? Or Bernadette Book Mayer? Would you be more or less likely to have a grilled cheese with me? Did Wittgenstein really rewash all the dishes at somebody else’s house? An image is not a picture, but a picture can correspond to it. Woman learns the concept of the past by remembering, but how will she know again in the future what remembering feels like? Maybe the stone is not as red as this day.

Gertrude Stein talked about roses a lot but they were only red. All tomatoes aren’t red either. Even blood isn’t red except in the air of the earth.

The writing of John McPhee, who works as a journalist, is startling in many ways. He has written books about Bill Bradley, geology, the Swiss Army, canoes, the Pine Barrens, oranges, art, and nuclear energy, reveling in the vocabularies of every subject and in words like “Berriasian” or “oolitic.” He has a great method of writing, using index cards. He publishes much in The New Yorker magazine.

Another great writer, someone not everyone knows, is Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz, who lived in a convent in that age when, if a woman wasn’t getting married, she carried on her life safely and knowledgeably, and, rather interestingly, behind closed doors, where she could study and write.

Catullus, of course, has been an inspiration for his way of communicating, using slang language, and insulting politicians. In fact, for insulting anyone in verse, even your best friend, Catullus is the best person to consult if you want to learn how to level insults well, not like how it’s done by certain past presidents of this country.

Everything I read will have an influence on me, so I’ll just mention a few of my more overwhelming influences as a writer of poetry: Louis Zukofsky, whose love of syllables and Latin and Anglo-Saxon words appears in poetic usage. Larry McMurtry, whose manipulation of emotion is both surprising and masterful, and Sappho, without whom I doubt we’d know what love might be. Let’s all have dinner together.

I was taking a class with Bill Berkson at the New School when he told me I wrote too much like Gertrude Stein. This was quite prescient of him since I had never read Gertrude Stein, so I hurried to. Here’s a description of “Cold Climate” from Tender Buttons:

A season in yellow sold extra strings makes lying places [so you can see the resemblances].

Tender Buttons is a hoot in many ways.

Stanzas in Meditation is another great book of poetry by this Stein. It’s like reading Shakespeare and for some it needs a translation. Maybe it’s a private language. Gertrude Stein taught us that the meaning is/isn’t a physiognomy (from Wittgenstein). If you want to include Hawthorne too, you could say phrenology. This Stein studied with William James and learned about stream of consciousness, that meaning is not the cat’s pajamas. Write a list of all the things meaning is not. You could begin with the bee’s knees. Many people think of poetry as words with rhyme and meter. But the battle to use everyday speech in poetry began with William Carlos Williams. Along with rhyme and meter seems to go meaning. So you can only have meaning in poetry if it’s metrical and rhyming, except when it’s like a Cubist painting or Kandinsky maybe.

In Einstein’s autobiography there is a section beginning “What, precisely, is ‘thinking’?” This is Einstein’s contribution to us as writers. The quote was republished in The New Yorker, in which it existed as narrow columns, giving me the idea that the beginning and end words of each line would make an interesting poem, which they do. We are grateful to Einstein for saying in his clear way what thinking is for all of us, and Gertrude Stein would be happy to know that thinking is not exactly remembering. I can’t think of anyone better to follow the expectations of life hanging together both in terms of living and writing. Another surprising illustrator of the very same thing is Emma Goldman, whose autobiography in two volumes is called Living My Life. No matter your political orientation, Goldman’s erudite prose and explication of her daily doings are urgent to keep in mind.

Reading the New York Times Science section on Tuesday and Science News provides you as a writer with ready-made poems, plus this is all stuff you need to know which exists besides your daily doings. For instance, if you walk in Central Park, it’s useful to know the glacial history of that neighborhood and that there once was an African American village there in the swamp on the Upper East Side. It would be useful to the world to write poems about science, if they’ve got to be about anything.

From Other Influences: An Untold History of Feminist Avant-Garde Poetry , edited by Marcella Durand and Jennifer Firestone, to be published by MIT Press next month.

Bernadette Mayer (1945–2022) published her first book, Story, in 1968. From 1980 to 1984, she was the director of the Poetry Project.

October 3, 2024

The Dreams and Specters of Scholastique Mukasonga

Watchers by Bradford Johnson. From Painting Past Photographs, a portfolio that appeared in The Paris Review issue no. 168 (Winter 2003).

“Every night the same nightmare interrupts my sleep.” With this sentence Scholastique Mukasonga begins her debut Cockroaches, a memoir that came out in French in 2006. That year, Mukasonga was fifty. She had been living in Normandy since 1992, when she moved there hoping to find employment as a social worker. She left Rwanda after a childhood marked by rising violence, shortly before the Tutsi genocide wiped out nearly her entire family. The nightmare with which she opens Cockroaches involves running away from a violent mob, not daring to look back—“I know who’s chasing me … I know they have machetes. I’m not sure how, but even without looking back I know they have machetes …”—then waking up with a start right as she is about to fall.

Especially in the cadences of its original French (“Toutes les nuits, mon sommeil est traversé du même cauchemar”), the book’s opening sentence jumps out as an allusion to the work of another famous, autobiographically minded frequenter of Normandy: Marcel Proust. Proust immortalized the Norman town of Cabourg under the fictional appellation of Balbec, and In Search of Lost Time opens with a temporally ambiguous admission of chronic sleeplessness that begins: “Longtemps, je me suis couché de bonne heure.” Proust’s narrator goes to sleep early yet sleeps fitfully. He dreams of beautiful women but also of chimerical specters from French history that presage the imminent demise of the many worlds to which he has belonged. These worlds include the airy sphere of French aristocratic milieus but also—so troublingly that Proust’s narrator barely admits it—the French Jewish community surrounded by an ever more virulent anti-Semitism.

Mukasonga’s allusion bears a manifold, if quiet, irony. It calls out the profound inequalities that separate her from the earlier writer whose cares and pleasures are worlds apart from the stories she goes on to tell. Proust’s narrator, Marcel, wakes from dreams that riff on his recent reading—“a church, a quartet, the rivalry between François I and Charles V”—at least as often as they dredge up one of his “childish terrors.” Mukasonga’s dreamscapes are monotonous by comparison, the past that haunts her welded to one central catastrophe. But at the same time, the allusion highlights the improbability of the life into which she has been cast, which finds her in the bourgeois setting of a private bedroom in northern France: a setting as familiar to Proust as it would have been alien to her parents. More abstractly, she ties her narrative back to Proust’s to suggest that her prose, like his, explores the blurry interstice between memory and dreaming. Her narrators chase after the past, a rapidly vanishing specter; they also flee from its swallowing presence, which continues to fill their minds with arabesques of variations on what actually happened, almost happened, could well have happened to them.

Like her other works—including Sister Deborah, the English translation of which is forthcoming from Archipelago later this month—Cockroaches is a reckoning with history, a steadfast commemoration of a community and culture that others tried to eradicate. But even in her debut, which many early critics read as a straightforward work of testimony about the Tutsi genocide, there is a deeply self-questioning quality to that work of commemoration. The narrator always wakes from her nightmare just as she is about to perish at the hands of her pursuers, who have already killed the other Tutsi girls fleeing alongside her. She thinks, “I know I’m going to fall, I’m going to be trampled”; and yet each night she reopens her eyes and her surroundings contradict this conviction. Why was she chosen to survive, and who did the choosing?

Mukasonga’s writing obsessively tries to answer this question, to justify but also to understand the reasons for her survival. Being spared from the genocide looms over her as an unaccountable miracle and as a heavy burden of mourning. Like the biblical prophet Jonah, spewed from the stomach of a whale, Mukasonga depicts her writerly vocation as something imposed upon her from the outside. She struggles to incorporate this calling into her sense of herself as a migrant and formerly colonized subject caught between radically different cultures, worlds, and histories.

Mukasonga’s writing is as striking for the bracing clarity and directness of her sentences as for the restlessness of its experimentations with genre: though she almost always writes about or around the Tutsi genocide, she never writes the same kind of story twice. Cockroaches presents itself as autobiography. The Barefoot Woman, her following book, enters into the perspective of her own mother while seeking to document the lives and beliefs of Tutsi women more broadly. From this widening scope, Mukasonga moves on to ever more overtly fictional work in which the epistemic framework of Western realism gradually makes space for, and struggles against, the polytheistic world of Tutsi belief systems. In her celebrated first novel, Our Lady of the Nile, and in the later Kibogo, Mukasonga stages conflicts as well as convergences between Tutsi spirituality and the Catholicism of Belgian colonizers and missionaries to Rwanda. Her represented worlds contain, for every Belgian priest or Rwandan Catholic convert who seeks to tamp out indigenous religious practices as the stuff of “witchdoctors,” a local priest fascinated by the similarities between biblical proverbs and local oral traditions, or a community that continues to practice their forbidden rites in secret. Mukasonga’s characters oscillate between these different belief systems, and occasionally try to combine them, as they search for meaning and comfort in environments riven by irrational human passions and prejudices as well as powerful natural forces like droughts and plagues. What deity, Rwandan or Christian, has elected to protect them today, and to what end? Her novels’ worlds are riven with a spirituality whose connections to particular moral or cultural systems remain unstable, and which her characters can never translate into patterns that quite make sense to them.

Sister Deborah takes on these themes even more explicitly and boldly than Mukasonga’s prior works. A slim volume, it has the condensed force and geographical sweep of a much longer novel. Like the earlier, still untranslated Cœur tambour (Drum heart), Sister Deborah takes place between the African and North American continents. The titular Sister Deborah, one of its two narrators, is a Black American Pentecostal Christian who finds that a divine spirit speaks through her. What spirit is it, though? Deborah wonders if it is “the Holy Spirit of the pastors,” but the figure that appears in her visions is a nursing Black mother: “I saw a large black woman, like a giantess, and she took me in her arms.” The tongues in which she speaks under this deity’s influence appear to be Rwandan, so Sister Deborah and her pastor move to Rwanda to prepare for the coming of this mother figure. There, Deborah eventually sheds her Christianity and becomes Mama Nganga, an outsider whom others consider a dangerous witch. While undergoing this slow transformation, Sister Deborah miraculously heals a young girl, the novel’s other narrator. This girl grows up and goes on to trace a version of her healer’s steps backward: she leaves her Rwandan village to become educated in Europe and is finally named a professor at Howard University. From this American academic perspective, she returns to the African continent and seeks out the former Sister Deborah to interview her.

What can the two women say to each other, and how can they understand each other? Do their life stories work in unison or merely run parallel? Sister Deborah presses on these questions of cultural translation, which are also Mukasonga’s own: questions of faith and syncretism but also of faithfulness to one’s origins. “When I see myself today in Washington, D.C., in my office at Howard, the Black Harvard,” writes her younger narrator, “I sometimes wonder who I am: Ikirezi, the sickly little girl from Nyabikenke, or Miss Jewels, the eminent Africanist, heeded and esteemed by her peers? … I begin to suspect that some unknown mysterious power emanating from the hands and cane of Sister Deborah, instead of my intellectual capabilities, has led me down a path that until now was forbidden to black women.” The paths lives take, Sister Deborah insists, are mysterious and unstable. And it would be disingenuous to claim that we do not yearn to explain these mysteries to ourselves, to mold these accidents and contingencies into narratives that make sense to us.

Though Mukasonga’s explicatory frameworks are religiously inflected, she does not lay blame for the histories she has lived through at the feet of a distant god. The world was not created as vast, syncretic, and mysterious as her generation found it. Her own survival was sponsored by some of the same colonial institutions that contributed to her society’s fracture and her family’s tragedy. Her characters’ dreamlike visions limn the contours of the global networks that have forced them, like Mukasonga herself, into a violent, compulsory transculturality in which individual lives become radically unpredictable. Writing about and for the Tutsi relatives she lost, Mukasonga also speaks with shattering immediacy to her Western readers, challenging them to see her family’s fate not as a faraway tragedy but as a specter created by conditions that implicate them. The many-named deities who cast her characters’ lots might not be controllable or knowable; still, in more than one sense, they are human creations.

Marta Figlerowicz is an associate professor of comparative literature at Yale University and a 2024 Guggenheim Fellow.

The Paris Review Daily recently published an essay by Scholastique Mukasonga, “The River Rukarara,” translated by Mark Polizzotti.

October 2, 2024

The River Rukarara

Map of Richard Kandt’s expedition to find the source of the Nile. From Caput Nili by Richard Kandt. Public domain, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

I was born on the banks of the Rukarara, but I have no memory of it. My memories come from my mother.

The Rukarara flows in my imagination and my dreams. I was just a few months old when my family left its shores. My father’s job required our relocation to Magi, a village at the top of a tall, steep incline that overlooks another river, the Akanyaru. Beyond the Akanyaru is Burundi. For us to go down to the river was out of the question. Mama forbade her children to climb down the hill, even the intrepid boys, for fear of seeing us tumble to the bottom, where crocodiles and hippopotami crouched in the papyrus, waiting to devour us—not to mention, she added, the Burundian outlaws who lurked in the swamps along the banks, ready to spirit children away in their canoes and sell them to the Senegalese, who traded in human blood. For me, as for my brothers and sisters, the Akanyaru remained an inaccessible stream visible far below, like a long serpent amid the papyrus that barred our access to the unknown world stretching beyond the horizon—a world in which other rivers surely flowed, other rivers that I swore to myself I’d explore someday.

When my family, like so many other Tutsi, was deported to Nyamata, in the Bugesera district, the truck convoy carrying these “internal refugees” had to cross an iron bridge over the Nyabarongo River. Neither the unbelievable din nor the jostling of the vehicles on the metal overpass could trouble my sleep in my mother’s arms. But Gitagata, the settlement village to which we were assigned, was far from the Nyabarongo. I went with the other girls to fetch water from Lake Cyohoha or, for solemn occasions, at the source of the Rwakibirizi, whose copious flow seemed to surge by the grace of an improbable miracle in this arid landscape. The deportees mentioned the Nyabarongo only to curse it. With its clay-reddened waters like a bad omen, it seemed the liquid wall of our prison, and that iron bridge, which I had to cross to and from school in Kigali, was the site of every humiliation and brutality, perpetrated by the soldiers at the guard post. At school, I learned that the Greeks, to get to hell, had to cross a black, freezing river called the Styx; I knew of another that led there: the Nyabarongo.

In our exile in Nyamata, my mother spoke constantly of the Rukarara. When one of my two youngest sisters, the ones born in Nyamata, got sick, my mother, Stefania, lamented: “Poor little things, they’ll never be healthy, they’ll never be lucky. I didn’t wash them in the waters of the Rukarara.” We, the older ones, who were born near the river (I myself had just barely made it in time), were inoculated against all sorts of ailments, against most of the evil spells that others would surely try to cast on us, and against all the poisons with which the envious would season our food; we might even, my mother hoped, avoid some of the inevitable misfortunes that weaved the fabric of every life. For her, the most effective baptism was not the one we’d received from the priests, but the one she had administered by washing our newborn bodies with the far more beneficial waters of the Rukarara.

According to Stefania, the banks of the Rukarara abounded in riches and treasures. Its waters, which filled the cattle troughs, had always protected cows from the plague epidemics that regularly decimated Rwandan herds. She disconsolately compared the half-barren, drought-ridden fields of Bugesera with the unparalleled fertility of the lands irrigated by the Rukarara. If my mother had been able to read my father’s Bible, no doubt she would have added the name Rukarara to those of the four rivers that, the Good Book told us, flowed from the primordial stream in the Garden of Eden.

It’s true that the Rukarara must have harbored many mysteries. The river’s source was in the heart of the great virgin forest of Nyungwe, at the edge of which we’d built our enclosure. Nyungwe was the monkeys’ domain. My mother bitterly defended our fields against their constant incursions. “No use fighting them,” she would say, “they’re too strong. But they do have wise leaders.” She claimed to have negotiated with their chief the amount of tribute that they would skim off our harvests and that, like it or not, we had to pay them. She made sure the pact was maintained, but at the troughs, the monkeys always went ahead of the cows. At night, at the hour when tales were told, Stefania revealed to us that the monkey king held his court at the source of the Rukarara. The monkeys chased away any other animal that attempted to drink from it, and they themselves respected its purity by merely dipping in leaves, which they then licked to slake their thirst.

A few years later, nearly all the members of my family who had remained in the Rukarara valley were massacred. The survivors reported to my mother that the river ran red with blood and corpses floated on its current.

***

“I was born on the banks of the Rukarara.” In the worst days of exile, I would repeat that sentence to myself, as if seeking reassurance that I indeed came from somewhere. For me, the river’s name was a more certain identity than the one that would be written on the travel permit granted by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees in Bujumbura, which everyone was desperate to get.

Before dawn, the crowd of refugees, so numerous that they blocked the streets, besieged the old colonial villa that housed the offices of the HCR. Some, especially the women, their babies crying on their backs, were waiting for the sacks of rice allotted to families. Others were there to claim a promised sewing machine with which they could set up shop in the Kamenge quarter of Bujumbura, to which the Burundian tailors already in business responded with intense hatred. But most came to procure a mysterious certificate that would allow them to obtain other certificates that would ultimately result, after countless procedures, if all the necessary conditions were met and all the documents duly assembled, in the issuance by the Burundian authorities of a residence permit or, for students and intellectuals, of a travel permit, which we hoped would open the doors of Senegal or the Ivory Coast or, better still, Belgium or even France or Germany, or, while we’re at it, why not the United States or Canada, especially Canada, yes, Canada …

The guards around the HCR offices enforced a haphazard discipline, letting through those who shouted, bullied, and shoved their way up to the fence, and barring entry to others who had patiently stood in line all day. Sometimes a man would exit carrying a sewing machine on his head, and everyone would applaud; the unsuccessful ones would hurl a litany of abuse at the international authorities, whom they accused of blatant partiality and persecution—always the same persecution, dogging them without respite … Little boys sold, for two francs, a handful of peanuts in a cornet of newspaper or, when the sun parched people’s throats, ice cubes of orange Fanta diluted with a fair amount of water from the Mutanga River, which serves as Bujumbura’s sewer.

I reached the gate ten minutes before the offices were due to close. A guard shrugged and let me through. Behind the window grille, the HCR employee, no doubt a Senegalese or a Malian, kept his head down while asking the ritual questions on the form.

“Family name?”

I answered “Mukasonga,” even though it wasn’t really a family name, since we don’t have them in Rwanda. It’s your father who names you, that’s all.

“Muka-what?”

I spelled it out.

“First name?”

“Scholastique.”

He raised his head slightly. “That’s a name?”

“Yes. Like ‘scholastic,’ but with an –ique.”

“Fine, I’ll put ‘Scholastic.’ Born where?”

I heard myself answer: “On the banks of the Rukarara.”

This time, the functionary leaned back in his chair and gave me a long once-over.

“And where is this Ruka-whatever?”

“Between Gikongoro and Cyangugu.”

“Fine, I’ll put Cyangugu, that one I know. I’ve been there, it’s next to Bukavu.”

I finally obtained the travel permit from the HCR. It was a declaration of statelessness: it forbade me from returning to Rwanda and closed me off from most other countries, whose embassies, upon seeing this paper marked with the infamous stamp of the refugee, would, naturally, deny me a visa.

In my despair, I closed my eyes and found myself back on the imagined banks of the Rukarara.

The Rukarara was, in a sense, inscribed on my flesh. I had only to plunge my hand into the bushy thickness of my hair and, feeling along my skull, trace the long furrow of a scar—a scar I more or less owed to the river. When Stefania would delouse her daughters on Sunday afternoons, she couldn’t help recounting yet again the circumstances surrounding the mark. Her fingers would slowly follow the bulge of skin the scar had left behind; then she would tell the story of the accident.

I had, she would say—and she still blamed herself for it—escaped her watch for only an instant. “You could never stay still,” Stefania sighed, “even before you knew how to walk!” I had thus ventured on all fours into the field on the edge of the river. My big brother Antoine was digging a channel to irrigate the sweet potatoes. He hadn’t seen or heard me coming and, while trying to pry out a clump of earth, he planted his hoe in my skull. Panic-stricken, my brother rushed toward the house, shouting my name, and ran into my mother, who was just as frantically searching for me. “I saw your skull split open,” she said, “and it wasn’t blood that was pouring out but a white froth, your brain, your brain escaping from you!” Stefania was proud of how she’d treated my injury: she had cleansed it with water from the Rukarara, then filled the gaping wound with mud scooped from the riverbed. Later, no doubt to encourage the wound to heal and scar over, she had gone to the middle of the current, where the river ran deepest, to collect some black silt, with which she slathered my head from brow to nape. I had to stay that way for several days. Each morning she anxiously checked the gash until, one day, she saw that all the black silt had been absorbed and the wound definitively scarred over. “That’s what saved you,” she would say exultantly. “The water and mud of the Rukarara saved you, but it might also explain why you always have something to say, why you can’t sit still, like the Rukarara. You will go far, my daughter. Perhaps Antoine’s hoe reversed the flow of your thoughts!”

***

For a long time, the Rukarara remained for me simply the river that bordered my family’s enclosure and fields. What became of it beyond that valley didn’t interest me. It was only while writing my novel Our Lady of the Nile, in which I imagined a girls’ school that I perched atop the crest of the Congo-Nile Divide and which I located as close as possible to a presumed source of the Nile, that I realized my little Rukarara might be connected to that mighty waterway.

Just like Veronica, one of the characters in my book, I tried to follow the fine blue line on the map that represented the Rukarara. It wasn’t easy to distinguish from the other rivers and tributaries that descended from the crest. The Rukarara, for its part, flowed directly from the Nyungwe forest, ran south, bifurcated capriciously toward the east upon meeting the Mushishito, then went back up in a northeasterly direction to merge with the Mwogo River and thus become the Nyabarongo, which encircled the heart of Rwanda with its majestic curve (the Nyabarongo, which the kings bearing the name Yuhi could not ford). Joining with the Akanyaru, it took the name Akagera; then, after combining with the Burundian Ruvubu, it finally poured into Lake Victoria, from which issued the river called the Nile.

After all these transformations, my beloved Rukarara thus becomes the Nile! It was even celebrated as “the most distant headwater of the longest river in the world,” as I discovered on the internet. I learned that a team of “explorers,” led by an Englishman and two New Zealanders, had set out to retrace the Nile to its source on small inflatable boats. The expedition left from Rosetta, near Alexandria, on September 20, 2005, and was expected to reach the source about ten days later. Was it in Burundi or Rwanda? That hadn’t yet been determined. After an encounter with the Lord’s Resistance Army in Uganda, which resulted in the death of a man who came to the party’s aid and the wounding of the “explorers,” the expedition was postponed until March 2006. The “explorers” ascended the Rukarara and, after continuing on foot once the stream became too shallow for their boats, arrived at a trickle of water bubbling up from a muddy pool at an altitude of 7,966 feet. That minuscule source of the Rukarara was proclaimed the most distant source of the Nile, whose length had until then been estimated at 4,108 miles and now went up to 4,174: thanks to my Rukarara, it grew by 66 miles!

Not to devalue the deeds of those “explorers”—though I do find it anachronistic to speak of explorers in the twenty-first century—but the Rukarara had been recognized as a likely source of the Nile well before then. In mid-August 1898, a German named Richard Kandt also reached the source of the Rukarara and declared it the source of the Nile. He wrote as much in letter XXVI of his book Caput Nili.

Here are a few notes gathered as I read excerpts of this book, like a bouquet of flowers cast into the Rukarara in Kandt’s memory:

Richard Kantorowicz was born on December 17, 1867, in Posen, Prussia (now Poznań, Poland), into a family of Jewish merchants. He began medical studies but didn’t complete them; even so, he was known as “Doctor.” In an effort to assimilate, he converted to Protestantism and changed his name to Kandt: Dr. Richard Kandt. In Berlin in 1896 he studied anthropology, ethnology, and geography. He dreamed of becoming an explorer and, toward that end, learned Swahili. It is said (though this might be apocryphal) that while in the Vatican Museum pondering a statue depicting the Nile as a bearded man, he decided, like so many others before him, to seek the sources of the great river. Felix von Luschan, who was then an assistant at the Berlin Ethnological Museum and is best known as the inventor of a chromatic scale for classifying skin color (ranging from no. 1 for the whitest skin to no. 36 for the blackest), told him about Rwanda as a possible place to look. After fruitless attempts to find sponsors for his expedition, he decided to finance it himself, borrowing against his inheritance.

His solitary trek defied conventional wisdom: Oscar Baumann, the Austrian explorer, had maintained that the Ruvubu, in southern Burundi, was the most likely source of the Nile. But Richard Kandt was betting on the Nyabarongo.

In March 1897, Kandt disembarked at Dar es Salaam. Staying just long enough to obtain the necessary authorizations and assemble his caravan—one hundred and forty porters, three guides, three servant boys, seven askaris (African soldiers)—he then headed inland. He stopped for several months in Tabora, where he bought a house. On March 29, 1898, he departed for Rwanda. His first action was to visit King Yuhi Musinga, whose court was in Mukingo, near the western border of the country. He was impressed by the densely populated land and its inhabitants, especially the Tutsi. Their physique and bearing corroborated the portrait sketched by the first European to enter Rwanda, Count von Götzen, which Kandt summarized as: “A caste of Semitic or Hamitic origin, whose ancestors, originally from the southern regions of Abyssinia, had conquered all the territory between the lakes … [and] whose giant stature—six and a half feet—recalled the world of tales and legends” (Caput Nili, letter XXIII). Kandt evidently subscribed to anthropological myths already woven around the Tutsi, rumors that would cling to them like the Shirt of Nessus.

The closer Kandt got to the capital, the more caravans he saw carrying tributes of foodstuffs and products to the royal court. On May 16, 1898, he reached Mukingo, seat of the royal residence.

In a flowery paragraph, Kandt describes the confluence of those many tributaries toward the royal enclosure:

Strange image: hundreds of black silhouettes, their lances gleaming in the sun, the bright colors of the multicolored cloths and several litters festooned with yellow braids, long caravans with pots and baskets—very much like streams flowing toward a lake—clear lines of innumerable intertwined paths on the yellow-green crests and slopes, passing by huts and courtyards, between fields of ripe millet and banana plantations, paddling across reed-filled swamps and lazy streams, converging in ever larger groups, and finally coming to rest like a giant, multicolored serpent around the outer enclosure of the Residence. (Caput Nili, letter XXIII)

After some procrastination by the court notables, Kandt was admitted into the royal residence for an audience with the mwami, the king. According to the information he’d been able to gather, Yuhi Musinga should have been around sixteen years old, but to his stupefaction, they introduced him to

a man of about forty, his eyes half-closed with sleep and with the copper-hued skin of an Indian. And yet, he was wearing the kingly attributes: a headband about eight inches wide made of white pearls, from which hung six zigzagging lines of pink pearls. From the upper edge of this strange headpiece, thick tufts of long, white, silky monkey’s fur fell onto his nape. From the bottom edge fell about fifteen braids of artfully mixed white and red pearls that covered much of his face down to his upper lip. He was dressed in a short, finely tanned pagne that covered his posterior and that, in front, was folded back twice in the area of his genitals, the leather directly on his skin, with a flap at the upper edge onto which was sewn a decoration consisting of rows of hundreds of small pearls. From the lower edge of the leather hung about twenty strips of woven snakeskin … On his arms, he wore a hundred fifty or two hundred copper or pewter bracelets, most of them bearing a fat blue pearl or small sleigh-bells cast from the same metals. Around a hundred iron wire bands encircled his ankles, which accounted for his heavy gait. (Caput Nili, letter XXIII)

The conversation, as interpreted by Kandt’s cook, was held with a dignitary. The king did not participate, merely giving an occasional nod. Kandt requested provisions for his men. He was promised some. After a quarter of an hour, discouraged by his interlocutors’ obvious lack of interest, Kandt withdrew and rejoined his camp. Later, once Kandt had won Musinga’s trust, it was divulged that the fake mwami was actually Mpamarugamba, a powerful ritualist of the cult of Ryangombe, master of the Spirits, with the power to block the harmful forces that these mysterious white visitors no doubt brought with them and thereby protect the person of the king, whose youth made him vulnerable.

The Rwandans took their time coming up with the requested provisions. But, faced with the white man’s impatience, the court eventually complied. Kandt could finally head out toward his intended goal.

First he passed through a highly populated region covered in banana plantations. Trees were few and far between, only a few large, solitary ficuses, noting that they were “devoted to the memory of a deceased tribal chief.” After “two weeks of pleasant walking,” he reached the confluence of the two rivers that would give birth to the Nyabarongo: the Mwogo and the Rukarara. The two waterways looked very different:

Like a tired, trembling old man, the Mwogo comes from the south, winding among the marshes … while the Rukarara leaps over stones and stumps like an unbridled flood, fresh and clear as youth. (Caput Nili, letter XXVI)

As Kandt noted, the Rukarara’s current was much stronger than that of the Mwogo, which suggested that he should follow the Rukarara to reach the possible source of the Nile. While this was the obvious choice, it didn’t appeal to him, for the source of Rukarara was reputed to be located in the middle of “a harsh, inaccessible jungle.” But the expedition pushed forward nevertheless, hugging the river’s increasingly steep banks as closely as it could. The houses, formerly so numerous, became scarce; on the fifth day, they disappeared entirely as the expedition penetrated “into the darkness of the virgin forest.” The chill surprised him, and the members of his caravan even more so: one servant boy woke Kandt in a panic to show him his water bucket, covered “with a layer of ice an inch thick.” In the morning, frost whitened the grass and trees, and on the following nights, Kandt abandoned his tent to sleep between two large fires, where they installed his bed.

It was in mid-August that Kandt finally reached his goal:

At that point, the Rukarara was no more than a rivulet about twelve inches wide, springing from a gorge with no egress, embedded in lush vegetation. I went in the next day with a native and several of my men. It was very difficult. It took us nearly an hour to go five hundred feet. But with hatchets and machetes, we managed to clear ourselves a path, wading into the swamp up to our waists, advancing on all fours in the glacial waters, painstakingly climbing the gorge; after several hours of punishing efforts, exhausted, soaked, and covered in mud from head to toe, we reached a small basin at the bottom of the narrow pass from which the source emerged from the earth, not bubbling up, but drop by drop: CAPUT NILI. (Caput Nili, letter XXVI)

In reality, judging from the tourist map I have here in front of me, the source that Kandt had just discovered was not that of the Rukarara but of one of its minor tributaries. The map labels it “Kandt’s Source”; the actual source of the Rukarara is starred as the “Source of the Nile” a bit farther north.

I’ll leave Dr. Richard Kandt to his fate, he who, before the missionaries, was the only European to live in Rwanda: botanist, cartographer, unofficial resident on behalf of the German authorities, and then, in 1907, official Imperial Resident, mainstay of Musinga’s power, and founder of Kigali, where you can visit his restored home (now the Kandt House Museum); on holiday in Germany when World War I broke out, called up for service, gassed on the Eastern Front; he succumbed in the military hospital in Nuremberg on April 29, 1918.

I’d rather imagine Richard Kandt in his camp in Rwanda: Night has fallen. The songs, laughter, and shouts of the porters, exhausted after a long day’s march, slowly die down. He has taken the bath that his servant boy has drawn for him, dined absent-mindedly on a filet of the antelope he killed the day before. As every day, he tries to read a page of Nietzsche, whom he greatly admires, but Zarathustra’s words get jumbled as Kandt’s thoughts drift back to the troubling encounters he’s been having since entering Rwanda. Who are these people, whose “discreet, reserved, serious, even blasé attitude” contrasts so sharply with the open, exuberant welcome he’d received up to now? And why are those young dandies of the court so disdainful of the richly brocaded silk fabrics, “the long Arab cloaks, the short multicolored jackets ornamented with rich silver threads,” and even the red uniforms of the Prussian hussars that he offers them? Why do they prefer “fabrics with dark, discreet patterns, preferably monochromatic”? Are they the barbarians that the members of Kandt’s caravan laugh about, who don’t know the value of precious silks and opt instead for simple cottons? Or are they like that aristocratic woman to whom Kandt described “magnificent Parisian finery,” and who answered that the jewelry was no doubt very beautiful but “more suited to a banker’s wife”!

Spotting the royal residence from the top of the cliff, why did he feel like a pilgrim making a long, arduous trek to the holy city?

Finally we scaled the last cliff and from its summit we saw the sovereign’s residence on the opposite crest. It’s a vast complex of round huts with a close tangle of interwoven enclosures surrounding large courtyards. The posts of the enclosures are fig trees which have taken root and which, with their large crowns of leafage, give the ensemble an attractive color. Huts of all sorts form a huge circle on the crests and slopes of the hills, the largest ones for the nobles, the smallest for the vassals … But your eye is constantly drawn back to the residence itself, which provokes a strange impression and awakens in me familiar images coming from hazy memories, without my being able to determine what period in my past they relate to. I search my memory during a brief rest stop the caravan takes to regroup. I rack my brains, and am not comforted by the faces that emerge as if from a long sleep, from a buried corner of my mind …

And finally I’m overcome by a feeling that has come to me several times during this journey, when I’ve witnessed particularly strange things: the dark, oppressive feeling that I’ve already seen and felt all of this in another, forgotten life. (Caput Nili, letter XXIII)

When he finally enters the royal enclosure, it’s like penetrating a medieval fortress: “The imagination begins working again and, in that remote part of Africa, brings to life the pennants of knights and pages, as if they were springing from ancient prints or books.”

But those “hazy memories,” the “dark, oppressive feeling” that Richard Kandt experiences—and reproves, since he is of course convinced of his superiority as a white man, not to mention a citizen of the German Empire—vis-à-vis those “Watutsi giants,” are but the funhouse-mirror image by which Europeans will constantly view Rwanda and its inhabitants. The greatest misfortune to have befallen Rwandans is to live at the source of the Nile, where, since antiquity, a myth had risen of a primordial land, a lost, unattainable paradise. To seek out the sources of the Nile, Caput Nili quaerere, was apparently, for the Romans, an expression that meant “to seek the impossible.” Rwanda was the one of the last remaining blank zones on the map of Africa that explorers delivered to colonialization. Maybe, just maybe, this final terra incognita harbored the last marvels, the last Mysteries, of a continent that was otherwise profaned by the sordid banality of colonial life. At the sources of the Nile, one could invent—short of actually encountering them—creatures straight out of Fables, a quasiprimordial race able to reenchant an Africa that had been debased by industry and mercantilism. And the Tutsi, so tall, with such elegant features, such imposing bearing, were tailor-made to play the part … Instead of Rwandans, one saw Egyptians directly descended from the pharaohs, Ethiopians related to the Queen of Sheba, Jews split off from the ten lost tribes of Israel, Coptic Christians who just needed to have their memories jogged …

So did Dr. Richard Kandt, born Kantorowicz—Jewish, intellectual, and a solitary explorer to boot, and for all those reasons subject to the sly contempt of soldiers and missionaries—really come so close to recognizing those fascinating, disquieting Tutsi as distant brothers? Were the huts of Mukingo really, for him, a ghostly image of Jerusalem?

***

I note with relief and a twinge of disappointment that the Rukarara has today returned to the ranks of ordinary rivers. They built a hydroelectric plant on it, which doesn’t seem to be yielding as much as anticipated, but at least the people who live nearby might someday hope to enjoy the benefits of electricity: the schoolchild studying under bright neon lights, the young intellectual recharging his phone, the rich man and his cronies spending their evenings guzzling shish kebabs and beer served by a charming young Rwandan girl, in front of the TV.

The source of the Nile itself is now accessible to tourists. A tour operator can give you directions. You leave from the Gisovu Tea Estate, but it’s best to telephone twenty-four hours in advance to reserve a guide. It is recommended to go up to Gisovu from Kibuye on the edge of Lake Kivu rather than from Gikongoro. From Gisovu, a path leads you to the source (the real source, not Kandt’s) in less than an hour. We’re assured that the walk is not strenuous.

It’s regrettable, for Rwandans and for anyone interested in Rwanda who, like me, doesn’t read German, that this book—Caput Nili, eine empfindsame Reise zu den Quellen des Nils (Berlin: Dietrich Reimer Verlag, 1904)—has not yet been translated. Only a few excerpts were quoted in French by Bernard Lugan in the journal Études rwandaises (vol. XIV, October 1980), published by the Université Nationale du Rwanda. I’m grateful to my friend Henri Moncomble, a professor of German, for translating the excerpts from letters I, XXIII, and XXVI of Caput Nili quoted in this piece.

In his biography of Monsignor Classe, Un audacieux pacifique (Namur: Grands Lacs, “Collection Lavigerie,” 1948), Father A. Van Overschelde dips his pen into the most anti-Semitic of inks to sketch a portrait of Kandt: “Richard Kandt was a Jew, very intelligent, a minor poet, short, stunted, with olive skin. The bile that caused this color was not merely beneath the skin: he was evil. His stature and perhaps also his ancestral habits did not incline him to act openly. He excelled at destroying from the shadows, with little swipes reminiscent of felines” (70).

Translated from French by Mark Polizzotti.

Scholastique Mukasonga was born in Rwanda in 1956. She settled in France in 1992, two years before the genocide of the Tutsi swept through Rwanda. Her groundbreaking books include: the debut novel Our Lady of the Nile, Cockroaches, Igifu, and National Book Award-nominated The Barefoot Woman and Kibogo. In 2021, Mukasonga won the Simone de Beauvoir Prize for Women’s Freedom.Mark Polizzotti’s latest book is Why Surrealism Matters (Yale University Press, 2024). His translations—of Scholastique Mukasonga, Patrick Modiano, Arthur Rimbaud, Gustave Flaubert, Marguerite Duras, André Breton, and others—have won the Oxford-Weidenfeld Prize and been shortlisted for the National Book Award.

October 1, 2024

An Excessively Noisy Gut, a Silver Snarling Trumpet, and a Big Bullshit Story

Each month, we comb through dozens of soon-to-be-published books, for ideas and good writing for the Review’s site. Often, we’re struck by particular paragraphs or sentences from the galleys that stack up on our desks and spill over onto our shelves. We often share them with each other on Slack, and we thought, for a change, that we might share them with you. Here are some of the curious, striking, strange, and wonderful bits we found, from books that are coming out this month.

—Sophie Haigney, web editor, and Olivia Kan-Sperling, assistant editor

From Hélène Cixous’s Rêvoir (Seagull Books), translated from the French by Beverley Bie Brahic:

I lie, I say I’m going to the hairdresser, secretly I’m off to see you, I am on my way right to the day when the Question peeps up, I no longer know which day that was. Dispatched on the instructions of Time, of Age, like a sprite ready to demand the Shadow’s identity card, proof of domicile, like the spirits of dates delegated to persecutions, of retirement dates, of warrants of life, of entry into silences, of fateful anniversaries

Day broke, the tale was back on the road, I followed it

From The Silver Snarling Trumpet, a memoir by Robert Hunter, the primary lyricist of the Grateful Dead, written in the sixties. The manuscript was long thought to be lost, but his wife recently rediscovered it in a storage unit. It will be published in full by Hachette:

It was the people who made the “scene” revolve; wonderful, inexhaustible people we thought … until we began to question things that perhaps we ought not to have questioned, things such as, “Can we live this way forever?” Perhaps we could have if we hadn’t asked, but by the very act of becoming conscious that a question existed, an answer became imperative. Part of the answer seemed to lie in the realm of whatever it was that society demanded of us … and what it demanded was our lives. Given impetus by this snatch of what seemed to be an answer, we began to ask the question of one another, and from there, it was only a small step to becoming frightened. And that, of course, was the end of being carefree, for we had begun, if only by the act of questioning, to care.

Others came along, others who would have belonged with us before, except that we began to question them too. Not seeing fit to acknowledge that such a question existed, they took over our philosophy and our guitars, our beards and cigarette butts, and left us with the world.

I remember coffeehouses and empty pockets, the unplanned, unending parties … the bad wine, the music that is inseparable from the impoverished decadence, and wonder sometimes if it was a fair trade.

From Elsa Richardson’s Rumbles: A Curious History of the Gut (Pegasus Books):

To quieten his patient’s obstreperous belly, Darwin devised a specially tailored course of treatment: she was to swallow ‘ten corns of black pepper’ after dinner, take a daily dose of crude mercury and allow a ‘small pipe’ to be occasionally inserted into her rectum to ‘facilitate the escape of air’. This dispiriting prescription would seem to imply that they were dealing with a purely physical problem, but in his notes Darwin pointed to another possibility: an excessively noisy gut, especially in a young woman, was often a symptom of ‘fear’.

From Jean Giono’s Fragments of a Paradise (Archipelago), translated from the French by Paul Eprile:

On L’Indien the captain started to curse. Calmly. At his pipe. At his lighter. At a button on his tunic. Just for the fun of it. The officers were cursing, but not in anger, and the crew began to indulge in the sheer pleasure of cursing. One evening when the moon was out, Hourdeau, on the night watch, went looking for the cabin boy, who’d gone to sleep on a stack of tarpaulins. He wondered where that little fool had gotten to. Then Hourdeau went below, took off his boots, and started to curse, calmly. First at the candle. Then at a flask of rum in the pocket of his peacoat. He went back up on deck, not worried, simply wanting to find the cabin boy. He called to him to windward. As it left his mouth, the boy’s name had no substance. It was immediately torn away. But what had real substance, and hit just the right note, was an old swear word he recalled, which he started to repeat with glee.

From Paper of Wreckage: An Oral History of the New York Post, 1976-2024 (Atria). “Wood” here refers to the front page of the New York Post:

David Rosenthal: Murdoch was very harsh with all the editors. He went around to every editor, whatever your purview was, and made you recite what your lineup was for the next day. He really wanted to get down into the weeds. I mean, what was your tenth or eleventh story that you had for the next day? I have a very firm recollection, because it shook me up, of going through the whole lineup, which was fairly standard, it was not a busy day. I came down to the bottom of the list, I said, “Oh, yeah, we have the shooting of a bodega owner in Brooklyn. It turns out, it looked like a drug deal gone bad with the owner of the store or some shit like that.” I just then went on to the next thing. He said, “Wait a minute, go back for a moment. Tell me more about the bodega murder.” I told him what little I knew. He said, “This is what we want to do. We want to get a reporter and photographer out to the wake tonight. And we want to hire a priest to say some prayers, ‘Brooklyn mourns’ that kind of thing. And we want to make a picture of that.” You could have heard a pin drop in the room. I actually said, “We don’t really do that.” He said, “Oh, yes, you do.” I said, “I don’t remember ever doing that”—because I’m a fool, you know, I know nothing. He says, “You’re going to do it. Otherwise,” he said, “when I’m stuck for a wood at 4:30 in the morning, I’m going to call you at home and ask, ‘What do you suggest?’ Do you understand?”… I went out of the meeting very shook … I forgot which photographer it might have been. I said, “You’ve got to get out to Brooklyn. I’m sorry. This is like a bullshit story. But it’s now a big bullshit story.” Aida [Alvarez] got me some copy, from what I remember. What would have been two graphs turned into books or something like that. I don’t think we ever did get the priest. Then we worked the cops on it. It was nothing. It wasn’t even a sympathy story because it was a drug deal that went bad, as I recall. It wasn’t the typical crying heart story. It was a fuckup story. I don’t think they played it as wood but they played it big the next day.

From Deborah Levy’s The Position of Spoons and Other Intimacies (Farrar, Straus and Giroux):

I have measured out my life with the sea urchins that have pierced my feet with their spines. I have now lost my fear of sea urchins. I don’t know why. There are other fears I would prefer to lose, after all. I know they have to survive in the wilderness of the ocean; their cousins are the sea star and they can grow for centuries. There are sea urchins that are almost immortal, older than the mortal mothers and their mortal children fleeing from wars on boats that sometimes sink. Life is only worth living because we hope it will get better and we’ll all get home safely. If we were to measure the love of mothers for their children with coffee spoons, there would never be enough spoons for that kind of love.

September 27, 2024

Hannah Arendt, Poet

Hannah Arendt, 1958. Photograph by Barbara Niggl Radloff. Münchner Stadtmuseum, Sammlung Fotografie. Licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

For a while there in the late nineties, it seemed to me like every other book of poetry that I flipped open in the bookstore was prefaced by an austere epigraph from the writings of Ludwig Wittgenstein. Plato, Rousseau, Nietzsche, Sartre, and Wittgenstein—for all their many differences—enjoy a special status as “poets’ philosophers” in the annals of literary history. Other lofty thinkers fly under poets’ collective radar; I have yet to come across a volume of verse prefaced by a quotation from David Hume. What makes some philosophers, and not others, into poets’ philosophers remains a mystery to me. But I’ve never really thought of Hannah Arendt as one of them.

Unemotional, anti-Romantic, and doggedly insistent on expunging unruly feelings from collective life, Arendt may seem to possess the least lyrical of temperaments, but a new volume of her poetry reveals that the author of sobering works like The Origins of Totalitarianism and The Human Condition was writing ardent and intimate verse in her off-hours. We’re pleased to feature Samantha Rose Hill’s new translation, with Genese Grill, of an untitled poem from Arendt’s manuscripts in our Fall 2024 issue.

Now housed in Arendt’s archive at the Library of Congress, the poem is dated to September 1947, six years after the philosopher’s arrival in the United States. Though she had by then settled on New York’s Upper West Side, Arendt reflects upon what she’d left behind on her life’s journey in this wistful poem:

This was the farewell:

Many friends came with us

And whoever did not come was no longer a friend.

The bracing conclusion of Arendt’s opening stanza lands with the impact of a practical realist’s rebuke to a sentimental fool: Friendship is companionship; therefore, whoever is not a companion cannot be considered a friend. (There’s something syllogistic to the philosopher’s adoption of tercets for this poem’s form.) In her introduction to What Remains: The Collected Poems of Hannah Arendt, which will be published later in December, Hill chronicles how Arendt’s notebook of poems accompanied her through a succession of farewells: when she fled Germany after her release from the Gestapo prison in Alexanderplatz in the spring of 1933; when she left her second life in Paris to report to the internment camp at Gurs seven years later; and when she escaped on foot and by bicycle to Lisbon, where she boarded the SS Guinee for Ellis Island on May 22, 1941. “This was the train: / Measuring the country in flight,” Arendt writes, “and slowing as it passed through many cities.”

From its melancholy opening to its bemused conclusion, Arendt’s poem reflects the emotional passage of many who leave home to take up residence in a foreign land. It begins as an aubade, or song of parting, and it ends with the enigma of arrival:

This is the arrival:

Bread is no longer called bread

and wine in a foreign language changes the conversation.

For the German speaker newly arrived in America, bread is no longer Brot. One irony of Arendt’s historical displacements lies in how her original German word for bread is now effaced by “bread” in the English translation. A further irony is to be found in the poem’s final line, where “a foreign language” intrudes on what would otherwise read: “and wine changes the conversation.” The essential purpose of wine—at a dinner party, for instance—is to change the conversation. But what is wine in a foreign language? When many of your dinner guests are, like you, serial émigrés who’ve fled Europe in the political wake of World War II, wine serves an additional purpose; anyone who’s found themselves a little more tipsily fluent at a dinner party abroad will understand how “wine in a foreign language changes the conversation.” Arendt made a home away from home for herself—and for others—in New York at 317 West Ninety-Fifth Street and, later, at 370 Riverside Drive, where she entertained fellow expatriates like Hermann Broch, Lotte Kohler, Helen and Kurt Wolff, Paul Tillich, and Hans Morgenthau. The slightly slanted rhyme of “Stadt” with “Gespräch” that concludes the poem in Arendt’s original German links the author’s mid-century Manhattan to the bonhomie of intellectual exchange; “city” sounds a little like “conversation” in the poet’s mother tongue.

Arendt’s poem, then, tells the story of her farewell to Europe and her arrival in the United States in a dozen lines of verse. But it’s also a self-aware work of art that quietly asserts its own place in the German poetic tradition—the bread and wine invoke the literary sacraments of Friedrich Hölderlin’s celebrated poem “Brod und Wein.” (“Bread is the fruit of the earth, yet it’s blessed also by light,” writes Hölderlin. “The pleasure of wine comes from the thundering god.”) German poetry, for Arendt, was a constant presence in both heart and mind. “I know a rather large part of German poetry by heart,” she said in a 1964 interview on German national television. “The poems are always somehow in the back of my mind.” She wrote her first poems when she was a teenager; some of these early literary efforts were addressed to her teacher—and lover—at the University of Marburg, Martin Heidegger. Those early love poems remained secret, like the affair that produced them, until after her death. Reading them now, we can see the intimate association of poetry and philosophy during this formative period in Arendt’s life. Yet her poems, unlike her philosophy, remained a private affair for Arendt to the end. We don’t know if she ever showed her poems to her close friends Robert Lowell, Randall Jarrell, and W. H. Auden in New York; to our knowledge, only her second husband, the poet and philosopher Heinrich Blücher, read her verse. The final poem to be found in the Library of Congress archive is labeled “January 1961, Evanston.” Its author was about to depart from a residency at Northwestern University to attend Adolf Eichmann’s trial in Jerusalem. What she saw there may have marked the end of poetry for Hannah Arendt.

Srikanth Reddy is the poetry editor of The Paris Review.

September 26, 2024

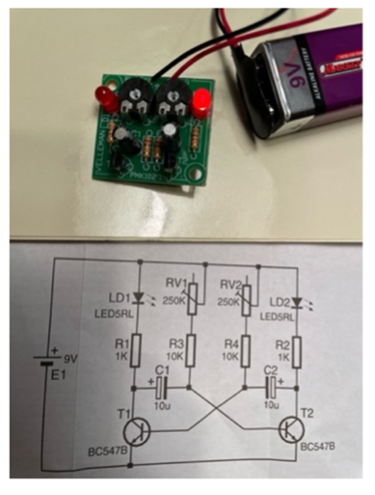

Control Is Controlled by Its Need to Control: My Basic Electronics Course

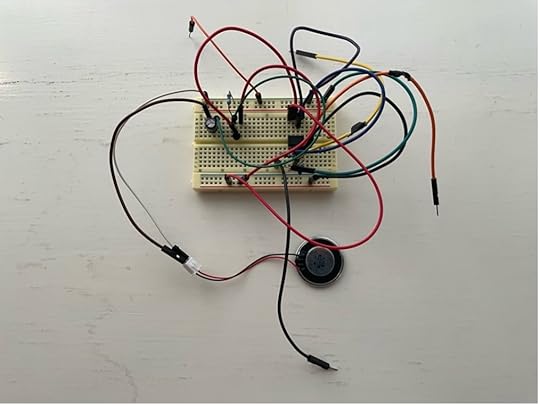

Photograph by J. D. Daniels.

Let me begin by insisting that I learned nothing.

What is left of it now, my electronics project, other than the names of these things? A solderless breadboard, and another one, and another one. A fifty-foot roll of twenty-seven-gauge insulated copper wire. Tactile switch micro assortment momentary tact assortment kit, not clear to me what that means. All these jumper wires with their connector pins, I tend to blank on their correct name and call them pinner wires. (When I was a kid, a pinner was a tightly rolled joint. Its opposite was a hog leg.) All the resistors in the whole world, and enough alligator clips to fill the Everglades, and a couple of bags of fuses, and a sack of capacitors, and a box of transistors, and my multimeter.

Starting Electronics, Electronics for Beginners, Electronics for Dummies, Getting Started in Electronics. Schopenhauer is right again: “As a rule the purchase of books is mistaken for the appropriation of their contents.”

An Eveready super heavy-duty 6V carbon zinc battery, with its classic black cat logo.

Red and green and yellow and blue LEDs. Even the kid who dropped out of my electronics class knew that Shuji Nakamura had solved the challenge of the blue LED. And why was that a challenge? Don’t ask me, man, I’ve got troubles of my own.

***

Here is my Ohm’s Law Simple Circuits Workbook. What is the voltage in this circuit? What is the amperage in this circuit? What is the resistance in this circuit?

I took my workbook to Florida. Creamy yellows, pastel blues and pinks, bleached whites, stucco, cinder blocks. The flat low buildings and the giant sky. Ibises, herons, egrets, sandhill cranes, crows and vultures. The world of the backward baseball cap.

I was in the Sarasota-Bradenton airport bar. They’d seated us on our plane, then led us back off it. A four-hour delay, they told us. I wasn’t calm, more like numb, but numb was close enough to calm for me to be helpful to the other passengers, who were angry or panicked. They told me about the important appointments and opportunities they were going to miss because of our delayed flight. “I don’t know why I’m telling you this,” they said to me, one after another. I sat in the bar, ate a sandwich, and solved problems in my Ohm’s Law Simple Circuits Workbook. But our four-hour delay became a thirty-six-hour delay, and a horse walked into the bar. I stopped solving problems and I started causing them.

***

Electronics, for three reasons.

One. My COVID lockdown pod included the writer of an electronics textbook. All behaviors are contagious.

Two. Chris Miller’s fantastic Chip War, the 2022 Financial Times Business Book of the Year, with its description of extreme ultraviolet lithography in the manufacture of integrated circuits.

Three. The bonkers ending of Norman Mailer’s The Deer Park, where God says to Sergius: “Think of Sex as Time, and Time as the connection of new circuits.”

All right, I will.

***

I was doing okay until my parents lost their house in Florida to Hurricane Ian the same month my girlfriend was diagnosed with cancer. Suddenly I needed someone to tell me what to do. I needed rule-governed activities.

I started with chess. An ice-world of rules, I told myself, to sustain me in my burning-down life. I took mate-in-one puzzles to the waiting rooms of oncologists and thoracic surgeons, to chemotherapy and immunotherapy infusions. Mate-in-ones are considered a pastime for children. One book had a cartoon squirrel on its cover.

I read Irving Chernev’s Logical Chess: Move by Move, Every Move Explained and The Most Instructive Games of Chess Ever Played and replayed classic games on my little folding chessboard at the dining room table after dinner and read Chernev’s commentary, while she snored on the sofa in a heap of her falling-out hair. She hadn’t cut her hair before treatment, and now it was falling out everywhere, making a mess and driving her crazy, but by now her scalp hurt too much for us to cut it.

On Sunday mornings I played chess with my next-door neighbors David and Austin, now and then stepping away from a game to drive my girlfriend to the emergency room.

***

I thought electronics could be the same way. Predictable outcomes, repeatable results, the artist’s dream of science. I took an electronics class because I wanted someone to stand at the front of a classroom and tell me what to do.

I told one doctor, “I wasted my education. I should have gone to medical school like you, because now I am a full-time nurse, but I don’t have the temperament, the technology, or the support team. I don’t have the expertise, I don’t have the peer group. Because I studied the poetry of Edmund Spenser, like a big dummy.”

An example of my bedside manner: “Will you shut up? I am trying to empty the blood out of your lung drain.”

I stayed up late, watching introductory instructional videos about basic electronics, about resistors. I tried not to drink too much, and failed. Farts were funny, until she farted blood. Until the weight loss, until the sigmoidoscopy, until the colonoscopy, until.

As the immunotherapy-induced rash on her leg worsened, I saw with mirthless self-awareness that the title of the book I was reading, Christ: A Crisis in the Life of God, was doing double duty as Cancer: A Crisis in the Life of John. In tonight’s performance, the role of God will be played by John. But I don’t have the temperament or the technology.

I was having trouble reading, but I could still listen to stories. One afternoon between doctor’s visits, I found myself listening to a sexy one. “I’m too stupid. I’m just a stupid little girl who needs her daddy to tell her what to do. Please. It’s so hard. Everything is so hard. Oh, I’m so stupid, Daddy, tell me what to do. Tell me what to do.”

It was soon obvious to me that I was the girl in the story I was listening to. I disowned my own fear and helplessness and projected it outside of myself, refusing to recognize it as mine, flattering myself that instead I was the omnipotent authority the helpless girl was pleading with. But I was the one who was pleading.

That is not pornography, it is a famous prayer. I’m too stupid, Daddy, please tell me what to do. Our Father who art in heaven, tell me what to do.

***

I was the only nonscientist in the electronics class. It was held in a fifty-thousand-square-foot open facility just over the bridge. Battery engineers, software designers, X-ray technicians. I kept my mouth shut. I think I was assumed to be a scientist, too.

I had an awfully good time. But I didn’t understand much of the lectures, and I didn’t understand most of the questions the other students asked, and I rarely understood the answers to those questions. I listened to the fans of the solder fume extractors.

Photograph by J.D. Daniels.

Here’s the “joule thief” I built by following instructions.

Photograph by J.D. Daniels.

What does it do? It does whatever I tell it to do.

It “can use nearly all of the energy in a single-cell electric battery, even far below the voltage where other circuits consider the battery fully discharged (or ‘dead’).”

Yet again I have built myself. The golem scratches its head.

***

“On Margate Sands,” T. S. Eliot wrote, “I can connect / Nothing with nothing.” I can connect metal to metal with metal: I am good at soldering. I put on my safety glasses, turned on my fume extractor fan, clamped my circuit board, unrolled my little coil of solder wire, heated up my soldering iron, and got to work. One of our teachers said, “We have a winner!” My girlfriend thought it might be due to the summer I had spent learning about welding. I’d taken two safety courses to be allowed to use the metal shop, then a MIG-welding intro, then a more focused and thorough welding course, then a kit course, if you want to call it that, where we all built the same project, a simple grill. Cutting, grinding, drilling and punching, the vertical bandsaw, the belt grinder and belt sander, the hydraulic ironworker, tack welding and stacks of tacks, drag welding, fillet welding, butt welding, cutting and patching, rooster tails of sparks thrown across the room by the angle grinder, pounding headaches from arc flash. I had performed adequately, not excelling but not having any accidents, unlike two of my welding classmates, who were always setting something on fire. Those classes had been years ago by now. But I thought it might be true that I had learned not to be paralyzed by a fear of burning metal.

Then, too, my electronics classmates, as friendly and smart and funny and good-looking as they were, seemed like they might be that commonly sighted species, the Northeastern achievatron. They wanted to get it right the first time and get an A-plus, a gold star, whereas I was confident I was going to do it wrong. So what. I’ll try anything once. I’ll go first. Here, hold my beer.

***

Tell me what to do. I followed instructions and I built little toy desk models. A forty-two-cylinder diesel radial engine model, based on the Zvezda M503 from Soviet missile boats. Before that, a U12 based on the GM 6046 twin-straight-6 from the Sherman M4A2 tank, an H16 based on the Formula One 1966 U.S. Grand Prix winner Lotus 43, and an X24 based on the Rolls-Royce Vulture. I built a toy model of a Schmidt coupling, a constant-velocity joint, a double universal joint, bevel gears, a slider-crank linkage, a sun and planet gear, a Scotch yoke, and a Chebyshev lambda linkage.