The Paris Review's Blog, page 25

August 5, 2024

Seven Adverbs That God Loveth

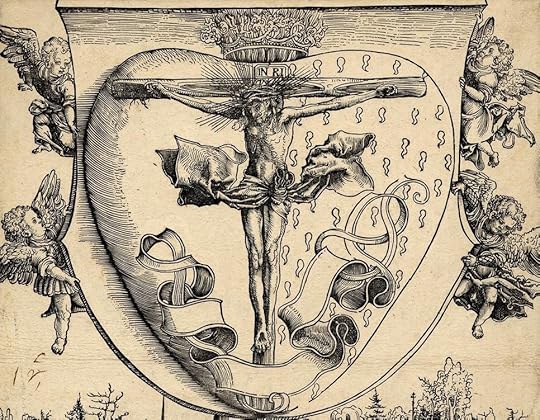

British Museum, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

I think I am temperamentally a mystic. I feel very drawn to this form of experience and this mode of conceptualizing and, in particular, the deepening and layering of concepts with experience and experience with concepts that can be seen in mystical traditions. Skepticism is not an instinctual or default response for me. If someone tells me something, I am inclined to believe it, no matter how strange it sounds. Maybe I’m just gullible, particularly when it comes to profound experiences that I have never really had, or never had in the way that I would really like. Maybe I’m just a bad philosopher. The thought has certainly crossed my mind.

For example, I believe that Julian of Norwich had Showings, or revelations of Christ; that George Fox, the founder of the Quakers, was carried up to heaven; that William Blake was visited by Angels in his dark little dwelling off the Strand in London; that Wordsworth had a total sensuous apprehension of the divine in nature during his ascent of Mount Snowdon; and that Philip K. Dick had an intellectual intuition of the divine in February 1974. This list could be continued. In fact, it could be nicely endless.

I don’t doubt these things, at least not at first, and I sometimes wonder whether I (as someone who teaches philosophy as a day job) should always be cultivating skepticism or praising the power of critical thinking. There is a defensive myopia to the obsession with critique, a refusal to see what you can’t make sense of, blocking the view of any strange new phenomenon with a misty drizzle of passive aggressive questions. At this point in history, it is at least arguable that understanding is as important as critique, and patient, kind-hearted, sympathetic observation more helpful than endless personal opinions, as we live in a world entirely saturated by suspicion and fueled by vicious judgments of each other. I’m not arguing for dogmatism, but I sometimes wonder whether philosophy’s obsession with critique risks becoming a form of obsessional self-protection against strange and novel forms of experience. My wish is to give leeway for strange new intensities of experience with which we can push back against the pressure of reality. All the way to ecstasy.

I am powerfully drawn to the way mystics experience what they experience, and then think, speak, and write about that experience. But it can be quite hard to describe, particularly to skeptical eyes who might see mystics as simply crazy, which in a way they are. Mad with God (whichever God that might be). So, I’ve decided to frame my approach to mysticism around seven adverbs that might get us closer to seeing the phenomenon. For—as the old Puritan saying goes—God loveth adverbs.

Mystics can be said to think and to work in the following seven adverbial ways:

1. Obliquely

2. Autobiographically

3. Vernacularly

4. Performatively

5. Practically

6. Erotically, and

7. Ascetically

Adverb one, obliquely: that is to say, enigmatically, negatively, through unsaying, oxymorons, antitheses, paradoxes, exaggerations, and subtractions. The writer of The Mystical Theology, who is known to us as Dionysius, who was possibly Syriac and not Greek, is the progenitor of apophatic or negative theology. He writes excessively of “super-essential darkness” or “darkness beyond radiance” to describe God. The anonymous, but Dionysius-inspired and Dionysius-translating, late-fourteenth century author of The Cloud of Unknowing, writes, “Of God himself, can no man think.” The Cloud author’s English translation of The Mystical Theology is simply and beautifully called Hid Divinitie. If God is hidden, then God must be approached obliquely, negatively. God transcends all affirmation.

It is the indirection of much mystical writing that interests me. Maybe indirection is the best direction to take in writing. What we can see in so many mystical texts, to borrow from my friend Eugene Thacker, is a logic and a poetics. This is a logic of saying and not saying, a non-negative negation, or a series of what we might call ascending negations, which is a way of approaching or adumbrating what Saint John Chrysostom calls “the incomprehensibility of God,” or the cloud of unknowing that separates us from the divine.

Mystical logic with respect to God is not a series of descending affirmations, from some postulation of God or substance down through some purported chain of being, from angels to humans, animals, and stones. It is rather a series of ascending negations, moving up from here below obliquely and superlatively, putting a cloud of forgetting between us and all creatures and peering up through a cloud of unknowing.

This logic of negation is also a poetics which places emphasis on a series of figures, like darkness, the desert, cloud, mist, sea, shadow, abyss, radiance, and the whole palette of colors that can be seen in my favored mystic, Julian of Norwich. Here, the intellectual insight into God is conceived on analogy with empirical sight. It is a multiplying of vision, from the perceptual to the conceptual. There are, for example, many climatological motifs in the poetics of mysticism, even a conceptual environmentalism. But this environmentalism is not literal or empirical but figurative and conceptual, where metaphors endlessly enrich and enliven experience.

***

Adverb two, autobiographically: the birth of autobiography, especially female autobiography, occurs with mystical writing. The “I” in Julian is the first “I” of an Englishwoman. The second is Margery Kempe, a generation later than Julian (they met in 1413; Margery wanted the counsel of Dame Julian, as she called her). The earliest stories of women’s lives we possess are in many cases the lives of the mystics: sometimes these were written directly by the mystic, as with Julian, Marguerite Porete, or Teresa of Avila, sometimes they were recorded by Brother Scribe, as with Angela of Foligno, Christina of Markyate, Christine the Astonishing, and many others.

Importantly, if there is an emergence of the autobiographical “I” in mystical writing, then it has the structure of “I is an other,” as Rimbaud said. The I finds its voice and itself through its relation to the otherness of God. Maybe this is why autobiographies without God are often so dull (one thinks of the contemporary tyranny of memoir) unless they stage autobiography as the self ’s conflictual, dialectical relation to itself, the division within the self that still inhabits the form of the religious narrative.

I am thinking here of Rousseau’s Confessions or, even more acutely, of his second of three autobiographies, Rousseau, Judge of Jean-Jacques, which takes the form of Rousseau interrogating himself. Or think of Nietzsche’s stunning self-presentation in his 1886 Prefaces and Ecce Homo, where Nietzsche is always doubled, at war with himself. Autobiographies without an “I is an other” structure are doomed to dullness, unless extraordinary things have happened to you.

***

Adverb three, vernacularly: that is, in the local spoken language. Julian describes herself as “unlettered,” which probably meant that she didn’t know Latin and wasn’t literatus. But other mystics, like Angela of Foligno from the thirteenth century, were probably entirely illiterate and relied on Brother Scribe, a devoted monk. Julian’s book is the first book in English by an English woman, but the same is true of Hadewijch of Antwerp in Middle Dutch, Porete in Old French, Mechthild of Magdeburg in Middle Low German, and Eckhart’s sermons in Middle High German. Medieval mysticism, especially in northern Europe, is the emergence of the vernacular as a religious language.

Of course, the use of the vernacular is an implicit challenge to the authority of the Catholic Church and its use of Latin. One can see this in England with John Wycliffe and the Lollards and the rise of what is called Lollardy, and their insistence on the use of the translated Bible from the late fourteenth century onwards, which is linked to popular insurgency against the powers of Church, King, and State—the Peasants’ Revolt of 1381. (Incidentally, one of the prime causes of the Revolt was a pandemic, namely the Black Death.)

Mysticism is often linked to what emerges in the Reformation in the early sixteenth Century with Luther, who also translates the Bible into German. Luther is antimystical, committed to the “alien” nature of grace, and opposed the so-called enthusiasts of the Reformation, like Thomas Muentzer and the Anabaptists, who stressed the immanence of God in every person. Although this is a much more complex issue than I am allowing here, which requires considerable historical nuance, the Reformation opens a different space for mysticism. The turn to the vernacular permits a democratization of religious institutions and a progressive laicization, an undermining of clerical power which can be traced with a particularly wild intensity in America (in groups like the Quakers, the Shakers, the Baptists, and the Mormons, and even all the way to Scientology).

***

Adverb four, performatively: We can approach this issue by following Michel de Certeau, who was an interesting fellow, both a Jesuit priest and a psychoanalyst. For de Certeau, mysticism is not a domain of knowledge or a series of texts whose truth is evidenced with reference to some exterior reality, like the substantiality of God. Nor is mysticism simply authorized through an appeal to visionary experience.

On the contrary, mysticism is a style, a set of practices, a way of speaking and acting that are self-authorizing. Mysticism is performative. It is a certain form of writing and speaking which does not just record experience, but which produces experience, new forms of experience that might not have been previously lived. Mystical writing is a heterology, where the presence of the speaker as subject is an effect of utterance made possible through the other speaking through the subject, where that other is usually God. “I is an other” is the basic mode of production for mystical texts. Mysticism is a heterology where God and the I become one, enter into a zone of indistinction. This lack of distinction between the I and God, which is premised on the annihilation of the Soul, is the strangely passive activity of decreation.

***

Adverb five, practically: The point about the performative dimension of mysticism can be put differently, and this is at the core of the work of the fascinating theologian, Amy Hollywood. She understands mysticism as it develops within monasticism, particularly from the Rule of Saint Benedict, from the sixth century. Mysticism develops in relation to rigorous religious practices, specifically the practices of reading (of scripture), preaching and participation in liturgy, especially the recitation of the Psalms. Importantly, these practices of reading, meditation, prayer, composition, and contemplation are both spiritual and physical practices. As Hollywood writes, “the Benedictine’s life is one in which the monk or nun strives to make every action a ritual action.” Mysticism has to be understood in relation to the cultivation of such practices. Perhaps such practices are the best that we can hope to attain when the world has fallen to pieces. I will return to the question of ritual and devotional practice.

Another, very simple, way of putting this point is that mysticism is not some noetic or intellectual activity, or some state of belief or nonbelief, or even some theoretical apprehension of the divine. Rather, mysticism is a practical matter, a matter of organizing one’s life around a set of practices which are ritually organized. It is about living according to a rule, however that might be understood.

This is the meaning of asceticism. Askesis is sometimes translated into Latin as studium, which is both spiritual and bodily. This is what it means to study, to be a student. Here is a speculative thought: we can also link the theme of practice to the origins of monasticism in Saint Antony and the Desert Fathers. One of the widely read books in the history of Christendom, much more widely read than Plato or Aristotle, was Athanasius’s Life of Antony. Despite five extended periods of exile, Athanasius was Bishop of Alexandria for forty-five years and was responsible for establishing the canon and order of twenty-seven books that make up the New Testament and which has been used ever since. The Life of Antony was a deliberate rewriting of Plato’s Apology, where Socrates becomes Antony, the philosopher becomes the monk, the pagan becomes the Christian. It was a huge hit.

Antony engages in a withdrawal or retreat from the city. Here, the city is Alexandria, which was the Manhattan of the ancient world—a commercial island city off the coast of a vast continent, set up by foreign, colonial powers, with a voracious appetite for everything. Antony goes first into the necropolis or city cemetery and from there into the desert, which is seen as a temple without walls. This is anachoreisis, a retreat into solitude, where the monk is the monos, the solitary. The idea here is that one can find God in the desert by withdrawing into a cave or into a cell. A cave is a cell. The desert is a kind of mystical laboratory where one can find God, a figure which is retained in changed form in the idea of the hermitage and the anchorhold. The point is that withdrawal is a practice.

In the Desert Fathers, the fruit of withdrawal can be hesychia, quiet, stillness, silence. It is the cultivation of apatheia, passionlessness or equanimity. The aim here is achieve a disinterestedness in existence, to become corpse-like, dead to the world. And in this retreat, the monk must constantly struggle with acedia, the noonday demon, or listlessness and sloth. Such is what we call depression, which Julian beautifully calls in Middle English hevynes, the heaviness with which the self is attached to itself, riveted to itself.

It is only by spending time with the noonday demon, the heaviness of depression, that God can be felt, heard, and communicated with. The downward plunge into dereliction and despair is what permits the “straining forward,” or ekeptasis, into God. It is only through listlessness that one might both listen to and lust for God.

***

Adverb six, erotically. I’d like to spend a little more time and space on this adverb, as it is so important for understanding mysticism.

For mystics, everything turns on the love of God. The divine is not some entity—some desiccated abstraction—that invites belief or disbelief, assent or dissent. No, God is to be erotically enjoyed. It is fascinating how much mystics place an emphasis upon the enjoyment of God, a listening which is a lusting. This can be felt more closely in the French term jouissance, which is an enjoyment which delights and pleases but also carries clear sexual connotations.

Marie of the Incarnation (1599–1672), a French missionary in Quebec, wrote, “God alone was my only enjoyment.” God is a source of spiritual pleasure, but also physical delight. This is why Christ is so important and the doctrine of the Incarnation is so vital. Christ is a sensuous being with a sensuous mother and a super-sensuous father. Our lived communion with Christ occurs through the Eucharist, where his flesh is eaten, and his blood imbibed.

The element of liturgical devotion that dominates all others for medieval mystics, particularly female mystics, is the Eucharist. The relation to God, the communion with God, takes place through the mouth. God is orality and enters one’s mouth with a kiss. The famous French mystic, Madame Guyon (1648–1717), writes, “We must remember that God is all mouth.” These words are taken from a commentary Guyon wrote, allegedly in a day and a half, on the Song of Songs. The most important text for Jewish and Christian mysticism, which also turns up in Sufism, is the Song of Songs.

This is not the place to do justice to the intense eroticism of the Song of Songs, this ancient, near-Eastern, nuptial drama, originally composed in Aramaic. The love described in the Song by a young woman—the Shulamite—and a young man is clearly sexual. But it is not sexually explicit. Instead, the Song uses a powerful language of agrarian simile. Her belly is like a stack of wheat, her hair is like a flock of goats streaming down Mount Gilead, her breasts are like two fawns or clusters of grapes. His abdomen is like a block of ivory, his lips are like roses, and so on.

Within Judaism, the Song as interpreted allegorically, not as the love between a girl and a boy but as Israel’s love for God and God’s love for his chosen people. Within Christianity, the Song of Songs is the mystical book par excellence, where the Church—the universal Catholic Church—takes the place of Israel and the two lovers are transformed into God in the person of Christ and the soul expressed through the community of the Church. The Song becomes an ode of love between Christ and the soul. Christian mysticism can be understood as a millennia-long meditation on the meaning of such love.

Already in the third century, Origen interprets the Song allegorically as an epithalamion between a bridegroom, understood as the logos or Christ as the Word of God, and the bride, understood as the soul. He insists on the distinction between eros and agape, or love and charity, where eroticism becomes chaste, and fleshly lust becomes refined love. But, in the medieval Christian tradition, everything passes through Bernard of Clairvaux, who wrote eighty-six sermons on the Song of Songs between 1135 and 1153, reaching only verse four of chapter three of the Song.

Bernard’s sermons are beautiful, subtle, densely layered palimpsests of quotation and allusion, where he allegorizes each sensuous detail in the Song—references to fragrance, ointment, myrrh, and aloes—as expressions of the soul’s itinerary toward a loving union with Christ. But matters become even more compelling when the affective force of Bernard’s sermons on the Song authorizes and licenses an entire tradition of medieval mystical interpretation which is intensely felt and deeply personal.

In Hadewijch’s Book of Visions (ca. 1250), the union with Christ is described in physical terms: “Then he came to me himself and took me completely in his arms and pressed me to him … Then I was externally completely satisfied to the utmost satiation. At that time I also had, for a short while, the strength to bear it. But all too soon I lost sight of that beautiful man.” One can find echoes of this intensely erotic relation to Christ in a significant number of fascinating female mystics, obviously Julian but also Angela of Foligno and Teresa of Avila (1515–1582), down through Madame Guyon and Marie of the Incarnation in the seventeenth century.

But it would be a mistake to think of the eroticism of this tradition of affective piety as restricted to women. Building from the Song of Songs, the fourteenth-century English mystic Richard Rolle (circa 1300–1349) describes the fire of love, the incendium amoris, in terms of heat, sweetness, and song. The effect of song, sound, and music, especially the Song of Songs, induces a sweetness of love that is felt through physical heat and compared to jewels and gems like topaz. In “The Spiritual Canticle” of John of the Cross (1542–1591), the spiritual marriage of Christ and the soul is compared with the kiss that opens the Song, “There I, being alone, ‘kiss you,’ who are alone.” Once again, God is all mouth and when his love flows into us, it is sweeter than wine. In this connection, we could also think of Saint Francis, with his open, porous, stigmatized body receiving the love of God. Or, indeed, Henry Suso’s identification of both himself and Christ as female.

The obvious eroticism of the Song of Songs develops into a complex tradition of affective piety where the path of the spirit opens through the body and where Christ is a transfigured mystical body: a material body, a spiritual body, and a political body through the community of the church. Many mystics have a fiercely erotic connection with God through the person of Christ. Think perhaps of the many medieval images of the lactating Christ who feeds us from his breast or with the blood of his side wound, what Amy Hollywood calls “that glorious slit.”

To put it mildly, the gender of Christ is fluid, at once masculine and feminine, neither and both, a most queer God. One of great virtues of the mystical tradition is that it allows, and indeed encourages, a more complex topology of sex and gender, of new behaviors and rich potentialities.

***

Adverb seven, the final adverb, ascetically. To my mind, mysticism is ascetic not despite its eroticism, but because of it. And this is a line of thinking that is perhaps puzzling for us: there is not a contradiction between eros and askesis, between love or lust and denial or discipline. Rather, there is a relation of complementarity where spiritual discipline permits the possible transfiguration of love. And it is love’s transfiguration which is of ultimate importance.

This is the reason why I am sympathetic to the allegorical reading of the Song of Songs that begins with Origen and continues through into Saint Bernard and the medieval female mystics. What is going on in the Song is not some banal literalism which sees it in terms of sex, but a transformation of the carnal, another thinking of the erotic, a distillation, what psychoanalysts would call sublimation. What is glimpsed here is some other lineament of desire, that would allow for other possibilities of enjoyment, even and especially the enjoyment of God.

I am curious about the meaningfulness of asceticism today. The forms of ascetic practice in which people engage are legion: hot yoga, ceaseless meditation, extreme fasting, various forms of detox, excessive exercise, and compulsive forms of routine-following, which was particularly acute during the COVID-19 pandemic. Or asceticism becomes pathologized, as with anorexia, bulimia, and other behavioral “disorders.”

We are still strongly drawn by the desire for asceticism, it seems to me. We are fascinated by the extremity of mystical practice—think of the wildly self-destructive antics of female medieval mystics like Christine the Astonishing described earlier, the self-mortification of monks, stylites, anchorites, and the bands of itinerant flagellants in the early Middle Ages. But we find such behavior and its metaphysical demands too rigorous and weighty for our softer secular souls. For us, the purgation of sin has become a juice detox, and flagellation has become our relation to a bad selfie posted on social media.

We are also, I think, deeply puzzled by the way in which mystical practice conceives of the relation between the spirit and the flesh, mind, and body. We have all apparently become holists or monists, where we are all body and body is all that there is. We are endlessly encouraged to listen to our body, let the body do the talking and keep the score. This would be nice if it were true. But it isn’t. We are not identical to our bodies, but rather our experience of our selves is eccentric, divided from itself. Body holism is a new ideological discourse, which is refuted every time we get sick or sit in the dentist’s chair, or—even better (or, actually, worse)—are plagued by hypochondriac symptoms, conversion disorders of the type that have become remarkably widespread: a pandemic of genuinely felt illusion.

Mysticism is an attempt to describe another relation to the body, centered around some distinction between spirit and flesh, pneuma and sarkos. Mysticism is about the spiritualization of the flesh and the fleshly, incarnate nature of the spirit—to understand this requires a certain asceticism. We do not coincide with ourselves. Only psychopaths coincide with themselves.

With these seven adverbs, we can begin to approach the strange and compelling phenomenon that is mysticism, although we have barely even scratched the surface. At its core is love. What mysticism offers is an elevation and transfiguration of love. Its meaning is love. At the very end of her Showings, Julian of Norwich famously writes,

And from the time that it was revealed, I desired many times to know in what was our Lord’s meaning. And fifteen years after and more, I was answered in spiritual understanding, and it was said: What, do you wish to know your Lord’s meaning in this thing? Know it well, love was his meaning. Who reveals it to you? Love. What did he reveal to you? Love. Why does he reveal it to you? For love. Remain in this, and you will know more of the same. But you will never know different, without end.

From Mysticism, to be published by New York Review Books in September.

Simon Critchley has written over twenty books, including works of philosophy and books on Greek tragedy, dead philosophers, David Bowie, football, suicide, and many other subjects. He is the Hans Jonas Professor of Philosophy at the New School for Social Research in New York and a Director of the Onassis Foundation.

Seven Adverbs that God Loveth

From Prabuddha Dasgupta, a portfolio in The Paris Review issue no. 200 (Spring 2012).

I think I am temperamentally a mystic. I feel very drawn to this form of experience and this mode of conceptualizing and, in particular, the deepening and layering of concepts with experience and experience with concepts that can be seen in mystical traditions. Skepticism is not an instinctual or default response for me. If someone tells me something, I am inclined to believe it, no matter how strange it sounds. Maybe I’m just gullible, particularly when it comes to profound experiences that I have never really had, or never had in the way that I would really like. Maybe I’m just a bad philosopher. The thought has certainly crossed my mind.

For example, I believe that Julian of Norwich had Showings, or revelations of Christ; that George Fox, the founder of the Quakers, was carried up to heaven; that William Blake was visited by Angels in his dark little dwelling off the Strand in London; that Wordsworth had a total sensuous apprehension of the divine in nature during his ascent of Mount Snowden; and that Philip K. Dick had an intellectual intuition of the divine in February 1974. This list could be continued. In fact, it could be nicely endless.

I don’t doubt these things, at least not at first, and I sometimes wonder whether I (as someone who teaches philosophy as a day job) should always be cultivating skepticism or praising the power of critical thinking. There is a defensive myopia to the obsession with critique, a refusal to see what you can’t make sense of, blocking the view of any strange new phenomenon with a misty drizzle of passive aggressive questions. At this point in history, it is at least arguable that understanding is as important as critique, and patient, kind-hearted, sympathetic observation more helpful than endless personal opinions, as we live in a world entirely saturated by suspicion and fueled by vicious judgments of each other. I’m not arguing for dogmatism, but I sometimes wonder whether philosophy’s obsession with critique risks becoming a form of obsessional self-protection against strange and novel forms of experience. My wish is to give leeway for strange new intensities of experience with which we can push back against the pressure of reality. All the way to ecstasy.

I am powerfully drawn to the way mystics experience what they experience, and then think, speak, and write about that experience. But it can be quite hard to describe, particularly to skeptical eyes who might see mystics as simply crazy, which in a way they are. Mad with God (whichever God that might be). So, I’ve decided to frame my approach to mysticism around seven adverbs that might get us closer to seeing the phenomenon. For—as the old Puritan saying goes—God loveth adverbs.

Mystics can be said to think and to work in the following seven adverbial ways:

1. Obliquely

2. Autobiographically

3. Vernacularly

4. Performatively

5. Practically

6. Erotically, and

7. Ascetically

Adverb one, obliquely: that is to say, enigmatically, negatively, through unsaying, oxymorons, antitheses, paradoxes, exaggerations, and subtractions. The writer of The Mystical Theology, who is known to us as Dionysius, who was possibly Syriac and not Greek, is the progenitor of apophatic or negative theology. He writes excessively of “super-essential darkness” or “darkness beyond radiance” to describe God. The anonymous, but Dionysius-inspired and Dionysius-translating, late-fourteenth century author of The Cloud of Unknowing, writes, “Of God himself, can no man think.” The Cloud author’s English translation of The Mystical Theology is simply and beautifully called Hid Divinitie. If God is hidden, then God must be approached obliquely, negatively. God transcends all affirmation.

It is the indirection of much mystical writing that interests me. Maybe indirection is the best direction to take in writing. What we can see in so many mystical texts, to borrow from my friend Eugene Thacker, is a logic and a poetics. This is a logic of saying and not saying, a non-negative negation, or a series of what we might call ascending negations, which is a way of approaching or adumbrating what Saint John Chrysostom calls “the incomprehensibility of God,” or the cloud of unknowing that separates us from the divine.

Mystical logic with respect to God is not a series of descending affirmations, from some postulation of God or substance down through some purported chain of being, from angels to humans, animals, and stones. It is rather a series of ascending negations, moving up from here below obliquely and superlatively, putting a cloud of forgetting between us and all creatures and peering up through a cloud of unknowing.

This logic of negation is also a poetics which places emphasis on a series of figures, like darkness, the desert, cloud, mist, sea, shadow, abyss, radiance, and the whole palette of colors that can be seen in my favored mystic, Julian of Norwich. Here, the intellectual insight into God is conceived on analogy with empirical sight. It is a multiplying of vision, from the perceptual to the conceptual. There are, for example, many climatological motifs in the poetics of mysticism, even a conceptual environmentalism. But this environmentalism is not literal or empirical but figurative and conceptual, where metaphors endlessly enrich and enliven experience.

Adverb two, autobiographically: the birth of autobiography, especially female autobiography, occurs with mystical writing. The “I” in Julian is the first “I” of an Englishwoman. The second is Margery Kempe, a generation later than Julian (they met in 1413; Margery wanted the counsel of Dame Julian, as she called her). The earliest stories of women’s lives we possess are in many cases the lives of the mystics: sometimes these were written directly by the mystic, as with Julian, Marguerite Porete, or Teresa of Avila, sometimes they were recorded by Brother Scribe, as with Angela of Foligno, Christina of Markyate, Christine the Astonishing, and many others.

Importantly, if there is an emergence of the autobiographical “I” in mystical writing, then it has the structure of “I is an other,” as Rimbaud said. The I finds its voice and itself through its relation to the otherness of God. Maybe this is why autobiographies without God are often so dull (one thinks of the contemporary tyranny of memoir) unless they stage autobiography as the self ’s conflictual, dialectical relation to itself, the division within the self that still inhabits the form of the religious narrative.

I am thinking here of Rousseau’s Confessions or, even more acutely, of his second of three autobiographies, Rousseau, Judge of Jean-Jacques, which takes the form of Rousseau interrogating himself. Or think of Nietzsche’s stunning self-presentation in his 1886 Prefaces and Ecce Homo, where Nietzsche is always doubled, at war with himself. Autobiographies without an “I is an other” structure are doomed to dullness, unless extraordinary things have happened to you.

Adverb three, Vernacularly: that is, in the local spoken language. Julian describes herself as “unlettered,” which probably meant that she didn’t know Latin and wasn’t literatus. But other mystics, like Angela of Foligno from the thirteenth century, were probably entirely illiterate and relied on Brother Scribe, a devoted monk. Julian’s book is the first book in English by an English woman, but the same is true of Hadewijch of Antwerp in Middle Dutch, Porete in Old French, Mechthild of Magdeburg in Middle Low German, and Eckhart’s sermons in Middle High German. Medieval mysticism, especially in northern Europe, is the emergence of the vernacular as a religious language.

Of course, the use of the vernacular is an implicit challenge to the authority of the Catholic Church and its use of Latin. One can see this in England with John Wycliffe and the Lollards and the rise of what is called Lollardy, and their insistence on the use of the translated Bible from the late fourteenth century onwards, which is linked to popular insurgency against the powers of Church, King, and State—the Peasants’ Revolt of 1381. (Incidentally, one of the prime causes of the Revolt was a pandemic, namely the Black Death.)

Mysticism is often linked to what emerges in the Reformation in the early sixteenth Century with Luther, who also translates the Bible into German. Luther is antimystical, committed to the “alien” nature of grace, and opposed the so-called enthusiasts of the Reformation, like Thomas Muentzer and the Anabaptists, who stressed the immanence of God in every person. Although this is a much more complex issue than I am allowing here, which requires considerable historical nuance, the Reformation opens a different space for mysticism. The turn to the vernacular permits a democratization of religious institutions and a progressive laicization, an undermining of clerical power which can be traced with a particularly wild intensity in America (in groups like the Quakers, the Shakers, the Baptists, and the Mormons, and even all the way to Scientology).

Adverb four, performatively: We can approach this issue by following Michel de Certeau, who was an interesting fellow, both a Jesuit priest and a psychoanalyst. For de Certeau, mysticism is not a domain of knowledge or a series of texts whose truth is evidenced with reference to some exterior reality, like the substantiality of God. Nor is mysticism simply authorized through an appeal to visionary experience.

On the contrary, mysticism is a style, a set of practices, a way of speaking and acting that are self-authorizing. Mysticism is performative. It is a certain form of writing and speaking which does not just record experience, but which produces experience, new forms of experience that might not have been previously lived. Mystical writing is a heterology, where the presence of the speaker as subject is an effect of utterance made possible through the other speaking through the subject, where that other is usually God. “I is an other” is the basic mode of production for mystical texts. Mysticism is a heterology where God and the I become one, enter into a zone of indistinction. This lack of distinction between the I and God, which is premised on the annihilation of the Soul, is the strangely passive activity of decreation.

Adverb five, practically: The point about the performative dimension of mysticism can be put differently, and this is at the core of the work of the fascinating theologian, Amy Hollywood. She understands mysticism as it develops within monasticism, particularly from the Rule of Saint Benedict, from the sixth century. Mysticism develops in relation to rigorous religious practices, specifically the practices of reading (of scripture), preaching and participation in liturgy, especially the recitation of the Psalms. Importantly, these practices of reading, meditation, prayer, composition, and contemplation are both spiritual and physical practices. As Hollywood writes, “the Benedictine’s life is one in which the monk or nun strives to make every action a ritual action.” Mysticism has to be understood in relation to the cultivation of such practices. Perhaps such practices are the best that we can hope to attain when the world has fallen to pieces. I will return to the question of ritual and devotional practice.

Another, very simple, way of putting this point is that mysticism is not some noetic or intellectual activity, or some state of belief or nonbelief, or even some theoretical apprehension of the divine. Rather, mysticism is a practical matter, a matter of organizing one’s life around a set of practices which are ritually organized. It is about living according to a rule, however that might be understood.

This is the meaning of asceticism. Askesis is sometimes translated into Latin as studium, which is both spiritual and bodily. This is what it means to study, to be a student. Here is a speculative thought: we can also link the theme of practice to the origins of monasticism in Saint Antony and the Desert Fathers. One of the widely read books in the history of Christendom, much more widely read than Plato or Aristotle, was Athanasius’s Life of Antony. Despite five extended periods of exile, Athanasius was Bishop of Alexandria for forty-five years and was responsible for establishing the canon and order of twenty-seven books that make up the New Testament and which has been used ever since. The Life of Antony was a deliberate rewriting of Plato’s Apology, where Socrates becomes Antony, the philosopher becomes the monk, the pagan becomes the Christian. It was a huge hit.

Antony engages in a withdrawal or retreat from the city. Here, the city is Alexandria, which was the Manhattan of the ancient world—a commercial island city off the coast of a vast continent, set up by foreign, colonial powers, with a voracious appetite for everything. Antony goes first into the necropolis or city cemetery and from there into the desert, which is seen as a temple without walls. This is anachoreisis, a retreat into solitude, where the monk is the monos, the solitary. The idea here is that one can find God in the desert by withdrawing into a cave or into a cell. A cave is a cell. The desert is a kind of mystical laboratory where one can find God, a figure which is retained in changed form in the idea of the hermitage and the anchorhold. The point is that withdrawal is a practice.

In the Desert Fathers, the fruit of withdrawal can be hesychia, quiet, stillness, silence. It is the cultivation of apatheia, passionlessness or equanimity. The aim here is achieve a disinterestedness in existence, to become corpse-like, dead to the world. And in this retreat, the monk must constantly struggle with acedia, the noonday demon, or listlessness and sloth. Such is what we call depression, which Julian beautifully calls in Middle English hevynes, the heaviness with which the self is attached to itself, riveted to itself.

It is only by spending time with the noonday demon, the heaviness of depression, that God can be felt, heard, and communicated with. The downward plunge into dereliction and despair is what permits the “straining forward,” or ekeptasis into God. It is only through listlessness that one might both listen to and lust for God.

Adverb six, erotically. I’d like to spend a little more time and space on this adverb, as it is so important for understanding mysticism.

For mystics, everything turns on the love of God. The divine is not some entity—some desiccated abstraction—that invites belief or disbelief, assent or dissent. No, God is to be erotically enjoyed. It is fascinating how much mystics place an emphasis upon the enjoyment of God, a listening which is a lusting. This can be felt more closely in the French term jouissance, which is an enjoyment which delights and pleases but also carries clear sexual connotations.

Marie of the Incarnation (1599–1672), a French missionary in Quebec, wrote, “God alone was my only enjoyment.” God is a source of spiritual pleasure, but also physical delight. This is why Christ is so important and the doctrine of the Incarnation is so vital. Christ is a sensuous being with a sensuous mother and a super-sensuous father. Our lived communion with Christ occurs through the Eucharist, where his flesh is eaten, and his blood imbibed.

The element of liturgical devotion that dominates all others for medieval mystics, particularly female mystics, is the Eucharist. The relation to God, the communion with God, takes place through the mouth. God is orality and enters one’s mouth with a kiss. The famous French mystic, Madame Guyon (1648–1717), writes, “We must remember that God is all mouth.” These words are taken from a commentary Guyon wrote, allegedly in a day and a half, on the Song of Songs. The most important text for Jewish and Christian mysticism, which also turns up in Sufism, is the Song of Songs.

This is not the place to do justice to the intense eroticism of the Song of Songs, this ancient, near-Eastern, nuptial drama, originally composed in Aramaic. The love described in the Song by a young woman—the Shulamite—and a young man is clearly sexual. But it is not sexually explicit. Instead, the Song uses a powerful language of agrarian simile. Her belly is like a stack of wheat, her hair is like a flock of goats streaming down Mount Gilead, her breasts are like two fawns or clusters of grapes. His abdomen is like a block of ivory, his lips are like roses, and so on.

Within Judaism, the Song as interpreted allegorically, not as the love between a girl and a boy but as Israel’s love for God and God’s love for his chosen people. Within Christianity, the Song of Songs is the mystical book par excellence, where the Church—the universal Catholic Church—takes the place of Israel and the two lovers are transformed into God in the person of Christ and the soul expressed through the community of the Church. The Song becomes an ode of love between Christ and the soul. Christian mysticism can be understood as a millennia-long meditation on the meaning of such love.

Already in the third century, Origen interprets the Song allegorically as an epithalamion between a bridegroom, understood as the logos or Christ as the Word of God, and the bride, understood as the soul. He insists on the distinction between eros and agape, or love and charity, where eroticism becomes chaste, and fleshly lust becomes refined love. But, in the medieval Christian tradition, everything passes through Bernard of Clairvaux, who wrote eighty-six sermons on the Song of Songs between 1135 and 1153, reaching only verse four of chapter three of the Song.

Bernard’s sermons are beautiful, subtle, densely layered palimpsests of quotation and allusion, where he allegorizes each sensuous detail in the Song—references to fragrance, ointment, myrrh, and aloes—as expressions of the soul’s itinerary toward a loving union with Christ. But matters become even more compelling when the affective force of Bernard’s sermons on the Song authorizes and licenses an entire tradition of medieval mystical interpretation which is intensely felt and deeply personal.

In Hadewijch’s Book of Visions (ca. 1250), the union with Christ is described in physical terms: “Then he came to me himself and took me completely in his arms and pressed me to him … Then I was externally completely satisfied to the utmost satiation. At that time I also had, for a short while, the strength to bear it. But all too soon I lost sight of that beautiful man.” One can find echoes of this intensely erotic relation to Christ in a significant number of fascinating female mystics, obviously Julian but also Angela of Foligno and Teresa of Avila (1515–1582), down through Madame Guyon and Marie of the Incarnation in the seventeenth century.

But it would be a mistake to think of the eroticism of this tradition of affective piety as restricted to women. Building from the Song of Songs, the fourteenth-century English mystic Richard Rolle (circa 1300–1349) describes the fire of love, the incendium amoris, in terms of heat, sweetness, and song. The effect of song, sound, and music, especially the Song of Songs, induces a sweetness of love that is felt through physical heat and compared to jewels and gems like topaz. In “The Spiritual Canticle” of John of the Cross (1542–1591), the spiritual marriage of Christ and the soul is compared with the kiss that opens the Song, “There I, being alone, ‘kiss you,’ who are alone.” Once again, God is all mouth and when his love flows into us, it is sweeter than wine. In this connection, we could also think of Saint Francis, with his open, porous, stigmatized body receiving the love of God. Or, indeed, Henry Suso’s identification of both himself and Christ as female.

The obvious eroticism of the Song of Songs develops into a complex tradition of affective piety where the path of the spirit opens through the body and where Christ is a transfigured mystical body: a material body, a spiritual body, and a political body through the community of the church. Many mystics have a fiercely erotic connection with God through the person of Christ. Think perhaps of the many medieval images of the lactating Christ who feeds us from his breast or with the blood of his side wound, what Amy Hollywood calls “that glorious slit.”

To put it mildly, the gender of Christ is fluid, at once masculine and feminine, neither and both, a most queer God. One of great virtues of the mystical tradition is that it allows, and indeed encourages, a more complex topology of sex and gender, of new behaviors and rich potentialities.

Adverb seven, the final adverb, ascetically. To my mind, mysticism is ascetic not despite its eroticism, but because of it. And this is a line of thinking that is perhaps puzzling for us: there is not a contradiction between eros and askesis, between love or lust and denial or discipline. Rather, there is a relation of complementarity where spiritual discipline permits the possible transfiguration of love. And it is love’s transfiguration which is of ultimate importance.

This is the reason why I am sympathetic to the allegorical reading of the Song of Songs that begins with Origen and continues through into Saint Bernard and the medieval female mystics. What is going on in the Song is not some banal literalism which sees it in terms of sex, but a transformation of the carnal, another thinking of the erotic, a distillation, what psychoanalysts would call sublimation. What is glimpsed here is some other lineament of desire, that would allow for other possibilities of enjoyment, even and especially the enjoyment of God.

I am curious about the meaningfulness of asceticism today. The forms of ascetic practice in which people engage are legion: hot yoga, ceaseless meditation, extreme fasting, various forms of detox, excessive exercise, and compulsive forms of routine-following, which was particularly acute during the COVID-19 pandemic. Or asceticism becomes pathologized, as with anorexia, bulimia, and other behavioral “disorders.”

We are still strongly drawn by the desire for asceticism, it seems to me. We are fascinated by the extremity of mystical practice—think of the wildly self-destructive antics of female medieval mystics like Christine the Astonishing described earlier, the self-mortification of monks, stylites, anchorites, and the bands of itinerant flagellants in the early Middle Ages. But we find such behavior and its metaphysical demands too rigorous and weighty for our softer secular souls. For us, the purgation of sin has become a juice detox, and flagellation has become our relation to a bad selfie posted on social media.

We are also, I think, deeply puzzled by the way in which mystical practice conceives of the relation between the spirit and the flesh, mind, and body. We have all apparently become holists or monists, where we are all body and body is all that there is. We are endlessly encouraged to listen to our body, let the body do the talking and keep the score. This would be nice if it were true. But it isn’t. We are not identical to our bodies, but rather our experience of our selves is eccentric, divided from itself. Body holism is a new ideological discourse, which is refuted every time we get sick or sit in the dentist’s chair, or—even better (or, actually, worse)—are plagued by hypochondriac symptoms, conversion disorders of the type that have become remarkably widespread: a pandemic of genuinely felt illusion.

Mysticism is an attempt to describe another relation to the body, centered around some distinction between spirit and flesh, pneuma and sarkos. Mysticism is about the spiritualization of the flesh and the fleshly, incarnate nature of the spirit—to understand this requires a certain asceticism. We do not coincide with ourselves. Only psychopaths coincide with themselves.

With these seven adverbs, we can begin to approach the strange and compelling phenomenon that is mysticism, although we have barely even scratched the surface. At its core is love. What mysticism offers is an elevation and transfiguration of love. Its meaning is love. At the very end of her Showings, Julian of Norwich famously writes,

And from the time that it was revealed, I desired many times to know in what was our Lord’s meaning. And fifteen years after and more, I was answered in spiritual understanding, and it was said: What, do you wish to know your Lord’s meaning in this thing? Know it well, love was his meaning. Who reveals it to you? Love. What did he reveal to you? Love. Why does he reveal it to you? For love. Remain in this, and you will know more of the same. But you will never know different, without end.

From Mysticism, to be published by New York Review Books in September.

Simon Critchley has written over twenty books, including works of philosophy and books on Greek tragedy, dead philosophers, David Bowie, football, suicide, and many other subjects. He is the Hans Jonas Professor of Philosophy at the New School for Social Research in New York and a Director of the Onassis Foundation.

August 2, 2024

The Private Life: On James Baldwin

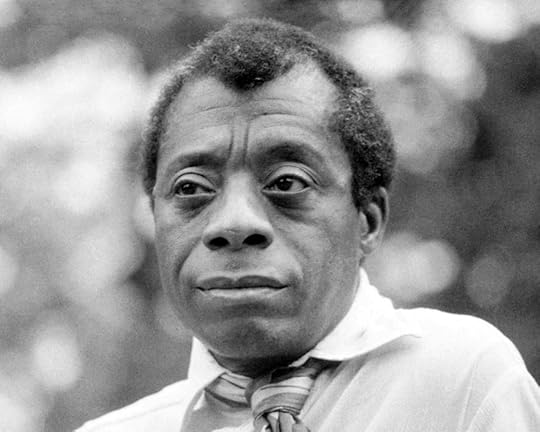

JAMES BALDWIN IN HYDE PARK, LONDON. PHOTOGRAPH BY ALLAN WARREN. Via Wikimedia Commons, licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0.

In his review of James Baldwin’s third novel, Another Country, Lionel Trilling asked: “How, in the extravagant publicness in which Mr. Baldwin lives, is he to find the inwardness which we take to be the condition of truth in the writer?”

But Baldwin’s sense of inwardness had been nourished as much as it had been damaged by the excitement and danger that came from what was public and urgent. Go Tell It on the Mountain and Giovanni’s Room dramatized the conflict between a longing for a private life, even a spiritual life, and the ways in which history and politics intrude most insidiously into the very rooms we try hardest to shut them out of.

Baldwin had, early in his career, elements of what T. S. Eliot attributed to Henry James, “a mind so fine that it could not be penetrated by an idea.” The rest of the time, however, he did not have this luxury, as public events pressed in on his imagination.

Baldwin’s imagination remained passionately connected to the destiny of his country. He lacked the guile and watchfulness that might have tempted him to keep clear of what was happening in America; the ruthlessness he had displayed in going to live in Paris and publishing Giovanni’s Room was no use to him later as the battle for civil rights grew more fraught. It was inevitable that someone with Baldwin’s curiosity and moral seriousness would want to become involved, and inevitable that someone with his sensitivity and temperament would find what was happening all-absorbing.

Baldwin’s influence arose from his books and his speeches, and from the tone he developed in essays and television appearances, a tone that took its bearings from his own experience in the pulpit. Instead of demanding reform or legislation, Baldwin grew more interested in the soul’s dark, intimate spaces and the importance of the personal and the private.

In 1959, in reply to a question about whether the fifties as a decade “makes special demands on you as a writer,” Baldwin adopted his best style, lofty and idealistic and candid, while remaining sharp, direct, and challenging: “But finally for me the difficulty is to remain in touch with the private life. The private life, his own and that of others, is the writer’s subject—his key and ours to his achievement.”

Baldwin was interested in the hidden and dramatic areas in his own being, and was prepared as a writer to explore difficult truths about his own private life. In his fiction, he had to battle for the right of his protagonists to choose or influence their destinies. He knew about guilt and rage and bitter privacies in a way that few of his white novelist contemporaries did. And this was not simply because he was Black and homosexual; the difference arose from the very nature of his talent, from the texture of his sensibility. “All art,” he wrote, “is a kind of confession, more or less oblique. All artists, if they are to survive, are forced, at last, to tell the whole story, to vomit the anguish up.”

Baldwin understood the singular importance of the novel, because he saw the dilemma his country faced as essentially an interior one, as his fellow citizens suffered from a poison that began in the individual spirit and then made its way into politics. And his political writing remains as intense and vivid as his fiction, because he believed that social reform could not occur through legislation alone but required a reimagining of the private realm. Thus, for Baldwin, an examination of the individual soul as dramatized in fiction had immense power.

***

Baldwin’s reputation as a novelist and essayist rests mainly on the work he did in the decade before 1963, a decade in which he was passionately industrious. The year 1963 seems to have been a watershed for him. He wrote hardly any fiction in that year. It was a time in which “the condition of truth” could not be achieved by solitude or by silence or by slow work on a novel.

Baldwin began the year by going on a lecture tour for the Congress of Racial Equality, known as CORE. In the first few days of January, he met James Meredith, the first Black student to enroll at the University of Mississippi despite being denied admission by the state’s governor. Meredith noted how quiet Baldwin was, but he was also amused by Baldwin’s version of the dance known as the twist.

Also in January of 1963, Baldwin met Medgar Evers. They began to travel together in Mississippi, investigating the murder of a Black man and visiting the sort of churches that Baldwin’s stepfather, the model for the Gabriel of Go Tell It on the Mountain, would have preached in.

When Baldwin returned to New York, where he lived in a two-room walkup on West Eighteenth Street, he became involved, with Lorraine Hansberry and others, in various protests. He also had a busy social life. His biographer David Leeming writes: “He still had the ‘poor boy’s’ fascination with the rich and famous … and they were just as fascinated by him. He found it difficult to refuse their frequent invitations. In short, the work was not getting done.”

In the spring of 1963, to find peace, Baldwin traveled to Turkey, which had become one of his havens.

In May 1963, back in the U.S., Baldwin spoke in nine cities on the West Coast over ten days, earning around five hundred dollars a speech, all of which went to CORE. In that month, his face appeared on the cover of the mainstream magazine Time. Three days later, when a friend gave a party for him at a restaurant in Haight-Ashbury, “literally hundreds of people struggled at the windows … to get a glimpse of him,” Leeming reports.

Two days later, Baldwin was in Connecticut, and then, on two hours’ sleep, he went to New York for a meeting with Attorney General Robert Kennedy. On May 12, Baldwin had wired Kennedy, blaming the federal government for failing to protect nonviolent protestors who had been beaten by police in Birmingham, Alabama. Now, on May 24, Baldwin and other activists, including Hansberry, Lena Horne, and Harry Belafonte, met Robert Kennedy at his home. The meeting went nowhere. Its main result was to increase the FBI’s interest in Baldwin.

In this same year—1963—as Baldwin made speeches, attended meetings, and stayed up late, he had many plans for work, including a book on the FBI. James Campbell writes in his biography: “Baldwin never produced his threatened work on the FBI, but he had, as usual, a multitude of other plans in mind, including the slave novel—now retitled ‘Tomorrow Brought Us Rain’—a screen treatment of Another Country, a musical version of Othello, a play called ‘The 121st Day of Sodom,’ which [Ingmar] Bergman intended to produce in Stockholm, and a text for a book of photographs by … Richard Avedon.”

Baldwin worked on the Avedon text after the assassination of Medgar Evers on June 12, 1963. It has all the hallmarks of his best writing: the high tone taken from the Bible, from the sermon, from Henry James, and from a set of beliefs that belonged fundamentally to Baldwin himself and gave him his signature voice: “For nothing is fixed, forever and forever, it is not fixed; the earth is always shifting, the light is always changing, the sea does not cease to grind down rock. Generations do not cease to be born, and we are responsible to them because we are the only witnesses they have.”

In August, Baldwin flew some members of his family to Puerto Rico to celebrate his birthday. Then he went to Paris, where he led five hundred people in a protest to the U.S. embassy, returning to the U.S. in time for the March on Washington at the end of the month. In September he went to Selma to work on voter registration. The following month he went to Canada. In December, he traveled to Africa to celebrate the independence of Kenya.

When Baldwin was asked how and where he had written his play Blues for Mr. Charlie, he replied: “On pads in planes, trains, gas stations—all sorts of places. With a pen or a pencil. … This is a hand-written play.” It was the only writing he completed in 1963.

***

Part of James Baldwin’s fame arose from his skill as a television performer. On camera, he used clear, well-made sentences. At times, he spoke like a trained orator, channeling his views into sharp wit, fresh insight, irony, with impressive verbal command. What he displayed was an intelligence that could quickly become grounded and combative and political once the television lights were on.

In some early appearances such as one on The Dick Cavett Show with the Yale philosopher Paul Weiss, Baldwin’s arguments were too complex for the short time he had been allotted. Because his delivery was slightly halting—he was articulate in bursts—he was too easy to interrupt, and he was always at his best when he could speak without interruption. It was as though he was sometimes too thoughtful for television.

This, of course, also gave him an edge. It meant that he was not mimicking politicians or TV regulars. He sought to challenge, and to set about thinking aloud. There were moments when he loved a simple question so that the answer could be ruminative and complicated. He used a context such as a talk show to state the most difficult truths in a style that belonged to the sermon or the seminar more naturally than the television studio.

He knew how to slow down, so that the camera lingered on his face as he prepared himself to say something difficult. He had a way, when he was about to offer an opinion that might seem extreme or unpalatable to his host or his audience, to hesitate, to let the camera see him thinking, and then to return to fluency.

At times, Baldwin’s manner in television interviews and in public debates could be scathing and indignant. But he could also be calm and self-possessed. In a 1963 debate in Florida, for example, even though his fellow panelists were hostile, Baldwin remained polite. He was ready to talk about the private life, the creation of the self, in a way that no one could argue with, since he himself had set the tone and the terms. He was also ready to make clear that the lives of white people, too, had been maimed by segregation. But what was most notable is how he moved his face towards the light, how he spoke with authority, and how at home he seemed to be in a television studio.

There were times when Baldwin appeared like a method actor playing out the part of thoughtfulness, working out as the camera rolled how a man considering things carefully might appear.

While he could be provocative, he was also measured. He exuded a sort of melancholy wisdom. At times, he managed to sound optimistic, especially in a panel discussion in August 1963, at the time of the March on Washington, when he was in the company of Harry Belafonte, Marlon Brando, Sidney Poitier, and Charlton Heston.

When Lionel Trilling wrote of the “extravagant publicness in which Mr. Baldwin lives” and wondered how Baldwin might find “the inwardness which we take to be the condition of truth in the writer,” Trilling was still in a world where it was presumed that writers should be quiet and stay home. And Trilling was not alone in believing that Baldwin was destroying his talent by going on television, writing articles, giving speeches, and being distracted by whatever was happening on the street.

But Baldwin belongs to a group of writers, born in the twenties and early thirties, who wrote both fiction and essays with a similar zeal and ambition; they did not see nonfiction as a lesser form or reporting as a lesser task. It was not easy to make a judgment on whether they were mainly novelists or, more likely, essayists who happened to write fiction. Also, it was often hard to make a judgment on what constituted their best work.

For example: Norman Mailer’s The Armies of the Night and his Miami and the Siege of Chicago, both works of imaginative and original political reporting, may equal his best novel, The Executioner’s Song. So, too, V. S. Naipaul’s long essay on the dictatorship in Argentina, “The Return of Eva Perón,” and his autobiographical essay Finding the Center may match in power his novels A House for Mr. Biswas and The Enigma of Arrival. Joan Didion’s Slouching Towards Bethlehem and The White Album may be better than her novels A Book of Common Prayer and Democracy.

These writers—Baldwin, Mailer, Naipaul, Didion—traveled, took an interest in life, and accepted commissions from editors. And all four understood that if writing is a display of personality, then their literary personality was, no matter what form they used, lavish enough to blur the distinction between reportage and high literary fiction.

But there were also times when all four of them took on too much; their interest in a subject was sometimes not equaled by their account of it. Baldwin’s book on the child murders that occurred between 1979 and 1981 in Atlanta, The Evidence of Things Not Seen, is slack and rambling; Mailer’s Advertisements for Myself and Marilyn: A Biography are not quite readable now, their egotism bloated and out of control; Naipaul’s travel books often present someone too mean and irascible, more interested in showing off his own crankiness than in exploring the world outside. And Joan Didion’s book Salvador might have been helped by more research.

What is fascinating about Baldwin’s occasional journalism and speechmaking is how uneven it is, and how rapidly this can give way to insights and sharp analysis and then a glorious, sweeping, seemingly effortless final set of statements and assertions.

While he worked fast on these stray pieces for magazines, Baldwin refused to settle for a simplified version of his own oppression. Instead, he combined irony and urgency in the same thought, seeking a manner that took its bearings from somewhere high above us, perhaps even from his own unique access to the word of the Lord.

“In a very real sense,” he wrote, “the Negro problem has become anachronistic; we ourselves are the only problem, it is our hearts only that we must search.”

In “As Much Truth as One Can Bear,” a New York Times Book Review article from January 14, 1962, when others might have been concerned about the police or about housing, Baldwin wrote about private loneliness as though it were the most pressing problem facing Americans: “The loneliness of those cities described in [the work of John] Dos Passos is greater now than it has ever been before; and these cities are more dangerous now than they were before, and their citizens are yet more unloved … The trouble is deeper than we wished to think: the trouble is in us.”

Sometimes, in his journalism and in his speeches, Baldwin was amusing himself. He took words such as equality or identity and concepts such as whiteness and examined them with a mixture of mischief and a sort of Swiftian contempt.

For example, in an address to Harlem teachers in October 1963, he sought to explode the myth of the original, heroic, white settlers in America: “What happened was that some people left Europe because they couldn’t stay there any longer and had to go some place else to make it. That’s all. They were hungry, they were poor, they were convicts. Those who were making it in England, for example, did not get on the Mayflower.”

In an essay called “The White Problem,” published in 1964, Baldwin wrote scornfully about the vast difference between the white and black American celebrities. He wrote, “Doris Day and Gary Cooper: two of the most grotesque appeals to innocence the world has ever seen. And the other, subterranean, indispensable, and denied, can be summed up, let us say, in the tone and in the face of Ray Charles. And there never has been in this country any genuine confrontation between these two levels of experience.”

He sought to elevate what was complex, multifarious, intricate. In 1966, he wrote: “Much of the American confusion, if not most of it, is a direct result of the American effort to avoid dealing with the Negro as a man.”

Since he had it in for easy and fixed categories, he was bound eventually to become eloquent about how his society dealt with the idea of men and masculinity.

In the early sixties, Baldwin spoke in an interview with Mademoiselle magazine about sexuality in his customarily challenging tone: “American males are the only people I’ve ever encountered in the world who are willing to go on the needle before they go to bed with each other.”

While early in his career Baldwin did not speak directly about his own sexuality, others were ready to offer hints and innuendos. A 1963 Time magazine profile, for example, described Baldwin as a “nervous, slight, almost fragile figure, filled with frets and fears. He is effeminate in manner, drinks considerably, smokes cigarettes in chains.”

When Lionel Trilling worried about Baldwin’s “extravagant publicness,” the implications of the word extravagant would not have been lost on many readers. And when Norman Mailer wrote of Baldwin that “even the best of his paragraphs are sprayed with perfume,” he would not have been easily misunderstood. Also, the extensive FBI file on James Baldwin includes the sentence: “It has been heard that Baldwin may be a homosexual and he appeared as if he may be one.”

Baldwin, in his own writings, was often careful. He liked complex connections, strange distinctions, ambiguous implications. Thus, even in a time when gay identity was becoming easier to denote or define, Baldwin resisted the very concept of gay and straight, even male and female, insisting in an essay in 1985 that “Each of us, helplessly and forever, contains the other—male in female, female in male, white in black and black in white. We are part of each other. Many of my countrymen appear to find this fact exceedingly inconvenient and even unfair, and so, very often, do I. But none of us can do anything about it.”

Religious elements in the civil rights movement were suspicious of both Baldwin and Bayard Rustin, a prominent organizer and activist who was close to Martin Luther King Jr. While King was not personally bothered by Rustin’s homosexuality, some of his colleagues were. One of them suggested that Baldwin and Bayard “were better qualified to lead a homosexual movement than a civil rights movement.” Baldwin’s homosexuality may have been one of the reasons why he was not invited to speak at the March on Washington in 1963.

But these were minor irritations compared to what happened when Baldwin’s fellow activists began to absorb fully the implications not only of Giovanni’s Room but also of Another Country. This third novel, published in 1962, became a bestseller. Its Black hero, Rufus, in the words of the Black Panther leader Eldridge Cleaver, was depicted as, “a pathetic wretch who indulged in the white man’s pastime of committing suicide, who let a white bisexual homosexual [sic] fuck him in the ass, and who took a Southern Jezebel for his woman.”

Cleaver, in his book Soul on Ice, published in 1968, wrote, “It seems that many Negro homosexuals … are outraged and frustrated because in their sickness they are unable to have a baby by a white man. … Homosexuality is a sickness, just as are baby-rape or wanting to become the head of General Motors.” Later, in an interview with The Paris Review in 1984, Baldwin said “My real difficulty with Cleaver, sadly, was visited on me by the kids who were following him, while he was calling me a faggot and the rest of it.”

It would have been easy then for Baldwin to have gone into exile, disillusioned and sad, to have written his memoirs and become nostalgic about the glory days of the civil rights movement. Indeed, he was planning to write a book about the murdered leaders Medgar Evers, Malcolm X, and Martin Luther King.

But this is not what happened. As the sixties went on, Baldwin became energized and excited by the Black Panthers, whose leaders he first met in San Francisco late in 1967. The three leaders—Huey Newton, Bobby Seale, and (despite their antipathies) Eldridge Cleaver—were, David Leeming writes, “as far as Baldwin was concerned, the future of the civil rights movement. … Baldwin admired the radicals; he saw them as part of the larger ‘project’ of which the old civil rights movement had been only a stage.” Baldwin wrote a preface to one of Seale’s books and supported Newton when, soon after their first meeting, he was arrested and imprisoned.

He also became more militant in his television interviews. For example, in an interview with Dick Cavett aired on June 16, 1969, he said: “If we were white, if we were Irish, if we were Jewish, if we were Poles, if we had in fact, in your mind, a frame of reference, our heroes would be your heroes too. Martin would be a hero for you and not be a threat, Malcolm X might still be alive. Everyone is very proud of brave little Israel, a state against which I have nothing—I don’t want to be misinterpreted, I am not an anti-Semite. But, you know, when the Israelis pick up guns, or the Poles or the Irish or any white man in the world says, ‘Give me liberty or give me death,’ the entire white world applauds. When a black man says exactly the same thing, word for word, he is judged a criminal and treated like one and everything possible is done to make an example of [him] so there won’t be any more like him.”

***

Two weeks before he died, the poet W. B. Yeats wrote a poem called “Cuchulain Comforted,” which began with a series of statements free of metaphor. The poem was written in terza rima, a form that was new for Yeats. Unusually, this poem did not need many drafts. It seems to have come to him easily, as if naturally. In earlier Yeats poems and plays, Cuchulain, a figure from Irish mythology, had appeared as the implacable, solitary, and violent hero, prepared for solo combat, free of fear. Now he has “six mortal wounds” and is attended by figures, Shrouds, who encourage him to join them in the act of sewing rather than fighting. They let him know that they themselves are not among the heroic dead but are “Convicted cowards all by kindred slain // Or driven from home and left to die in fear.”

Thus, at the very end of his life, Yeats created an image that seemed the very opposite of what had often given vigor to his own imagination. His heroic figure has now been gentled; his fierce and solitary warrior has joined others in the act of sewing; instead of the company of brave men, Cuchulain seems content to rest finally among cowards.

This poem is not a culminating statement for Yeats, but a contradictory one; it is not a crowning version of a familiar poetic form, but an experiment in a form—terza rima—associated most with Dante. Instead of attempting to sum up, it is as though Yeats wished to release fresh energy by repudiating, by beginning again, by offering his hero a set of images alien to him, which served all the more to make the hero more unsettled, more ambiguous.

How fascinating to see a writer abandon bold self-assertion and, however briefly, find a tone that is compassionate and genial and tender.

There was, however, no such moment in Baldwin. From the beginning, he displayed his own vulnerability, his own softness, sometimes as a weapon but mostly as a way of transforming an argument so that it was not a contest to be won but rather a question to be reframed—to be moved from the narrow confines of the public realm back towards the unsettled (and unbounded) space of the self, the questing, uneasy spirit.

Adapted from On James Baldwin by Colm Tóibín, now available from Brandeis University Press.

Colm Tóibín’s most recent book is The Magician. He was interviewed by Belinda McKeon in issue no. 242 of The Paris Review.

August 1, 2024

I Got Snipped: Notes after a Vasectomy

From Five Paintings, a portfolio by Olivier Mosset that appeared in The Paris Review issue no. 44 (Fall 1968).

Popop, who came home to raise me after his release from Holmesburg Prison in ’88, would have never let a white man in a white coat lay a hand on the D, let alone the vas deferens, had he the context to differentiate between the two. He never mentioned any experiments either. If he had, he wouldn’t have seen the wanton use of his body as some epic reveal of treachery but another quotidian instance he might describe by way of an exasperated sigh, shrug, or “Duh, dickhead” hurled at some scholar with the “real” details, or social reformer come to reimagine us in their image, to correct our supposedly devious sexual habits before it was too late, which often meant well before our twelfth birthdays. Given the early onset encroachments of power, that old black adage on suspicion and physicians was never an abstraction at home.

I got snipped anyway.

And I was late, by any reasonable measure, thirty-two with too many kids climbing up my leg, three boys and one girl whose temperaments have long since broken and rebuilt me in their images, the first of whom arrived too soon after his mother stopped taking birth control and forgot to tell me. And I’ve never met people more averse to independent play. Shouts of “Daddy!” and “Dada!” puncture my every attempt to think, coming on as tickles or itty-bitty terrors between each typed word, and so I write this from two worlds at once, where promises of the near future—the local pool or doggie park, Rita’s Water Ice, the school track, the bike trail, or playing Diablo and Super Smash Bros.—defang the demands on my attention for ten or so minutes at a time. The interstices allow collective laughter over new word enunciations—a six-year-old’s “feastidious,” or a question of the utmost importance: Who taught the twins to say “Fresh to def?” My daughter, twelve, takes credit, and my oldest son, two years her senior, is above it all until we remind him how the ticklish remain so, even chin hair deep into puberty. It’s there, between the laughter and all my pleading—“Stop, no, don’t” and “Put that dog down!” and “Stop chokin each other!”—that I give myself over to thought, which is writing, and in this case or every case, correlated with what the children mean to me, and what I might mean to them, and what it meant to ensure that I might conceive children nevermore.

The doctor was quite brown, if that counts for anything in this context, and not one of those people whose entire personality is dedicated to the hatred of children, who seem to be multiplying on every blunt “side” of the political spectrum. Gentler than most lovers, he cupped my testicles and said that everything would be all right. And in this man’s supple embrace I drifted off into a blissful nondream of future agency.

My homie Drake—no, not the former child actor with the slimthick sandworm sex tape, but a real person—had already sworn by it as a matter of ideal if not yet action, watching and waiting for some of us to go first before sliding into the VA hospital with his trademark gusto. In his episode of Hot & Single last year, it was the second bullet point on a little red billboard advocating his potential fuckability:

Fashion photographerHas a vasectomyThinks liking art is a personality

This was much like when we all joined the army in our teens, unable to afford rent, or love—despite whatever J.Lo might have said in 2001—and made another friend go first. It was Bruce that time, exchanging three or so horrible jobs for one in which you might support the empire less obliquely or lose your life, but be fully clothed and have a place to live, groceries for your mom and them, who damn sure weren’t gonna be fed otherwise. None of us had any children yet, though we certainly longed for a kind of family we almost didn’t have.