The Paris Review's Blog, page 29

June 6, 2024

Undisputed: Fury vs. Usyk

Screenshot of match highlights from DAZN Boxing.

At about 1 A.M. local time in Riyadh, on a Saturday in late May, Tyson Fury and Oleksandr Usyk met in the center of the ring for the chance to become the “undisputed” heavyweight champion of the world. It was the first time in twenty-five years—since the Brit Lennox Lewis beat the American Evander Holyfield—that boxing would be able call one man its sole heavyweight champion due to the money-spinning, head-scratching antics of its various governing bodies. Tyson Fury is a six-foot-nine behemoth and gift to nominative determinism. He has become arguably the most “notorious” fighter—in his era thanks in large part to his size, but also to his unlikely resurrection story. Having beaten the man who was then at the top of the business, the Ukrainian Wladimir Klitschko, in 2015, Fury looked to have announced himself as the new head of the heavies before unraveling completely into substance abuse and morbid obesity, spiraling to a point where he seemed lost to boxing, and almost to life. In 2018, he lost most of the unhelpful proportion of his bulk to come back and dethrone Deontay Wilder, a whip-cracking American heavyweight who had knocked most of his rivals cold. He’s since spoken of having made a suicide attempt at his lowest, and has become something of an advocate for mental health awareness, as well as the star of a Netflix reality TV series, large portions of which involve him driving to the local dump in a Volkswagen Passat.

Fury—the self-proclaimed “Gypsy King”—is of Irish Traveller heritage and tends to give tabloid journalists profanity-laden, libel-baiting copy. Bald, love-handled, with spindly legs, a Brobdingnagian among the citizenry, he is fleet-footed and elegant in the ring, like some big-game beast suddenly streamlined within its proper element. He had seemed cocksure as ever going into the weekend, having previously called Usyk, who is much smaller, a “rabbit” and a “sausage,” among other slightly feudal insults. Unlike in every other weight division, where ounces are a matter of debate and contract law, in the heavyweight division there is no upper limit.

Usyk has had other, even bigger things on his mind. Usyk is Ukrainian and had, following Russia’s invasion, for a time been on the front line. Usyk was urged to return to the ring to give his nation’s beleaguered but resolute populace something to cheer, so he brought a steely purpose, albeit a divided attention, to the clash. He formerly operated in the weight division below heavy, cruiserweight, and had been a unified champion there before bulking up to enter the more lucrative land of the giants. Impeccably well drilled and increasingly squat and solid, having grown into his new big-man status, Usyk seemed unmoved by Fury’s usual erratic rants. He also seemed unmoved when Fury’s father headbutted a member of Usyk’s entourage on the Monday of fight week, serving only to bloody his own head in the process.

A left-hander, or “southpaw,” Usyk is a stylist and had proved a conundrum too difficult to unpick for all his professional opponents so far, exhausting them with educated, relentless pressure and balletic footwork, forcing them to fight at a high pace and with maximum concentration, sapping them mentally as much as physically by requiring them to be constantly hyperalert. Usyk’s plan for Fury would be much the same. “Don’t be afraid. I will not leave you alone.” he had said to Fury in the lead-up. He had talked of there being no fat wolves in the forest—that it was the lion, not the elephant, who ruled the jungle. Fury, too, was undefeated as a professional.

The fight, in this era, could take place only in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. In recent times boxing has joined the list of sports being coaxed to offer up their glamour nights to the lure of Saudi riches; the term “sportswashing” has been heard in tennis, golf, darts, soccer, and Formula One of late, too. Ali fought in Mobutu’s Zaire, in Marcos’s Philippines, we are reminded. Boxing isn’t alone in selling its biggest occasions to the highest bidder, but it’s always been among the most enthusiastic, and rapid, responders when regimes hoping to present a face beyond their human rights rap sheet pick up the phonebook. It’s unfair, perhaps, to blame the fighters themselves, looking for life-altering money to undertake their life-threatening occupation. Boxing has been called “the red-light district of sport,” and its red light has been glowing especially bright since the authentic-seeming boxing fan Turki Alalshikh, chairman of the general entertainment authority in Saudi Arabia, opened up an apparently bottomless purse to make fights that fans have long been desperate to see. “His Excellency,” or “Mr. Turki,” as some of the fighters tend endearingly to call him, received a lot of thanks from all the major players this weekend. Only Jesus would be given more credit during the night’s in-ring interviews.

Usyk walked to the ring in Ukrainian costume, and Ukrainian colors—a fur hat with feathers, a fetching green military coat over his white shorts flecked with national blue and yellow; Fury sang and danced to a soundtrack of first Barry White and then Bonnie Tyler. In the ring he was wearing something green that looked like a cross between a kilt and a plus-size flower petal, with a faintly gladiatorial air to it. So far the big fights in Saudi have occurred in quiet, large, and purpose-built stadia, but there were more traveling fans for this one. The arena was peppered with mostly sporting celebrities and dignitaries. As the referee gave final instructions, Fury weaved his head like a charmed snake, flicked out his tongue.

The fight began a little cagily—both testing each other with jabs to the body, Usyk with the decidedly larger target to aim for. Fury was, as so often, full of feints and a little clowning for the gallery. The first big shot came from the smaller man, though. At the end of the first of the contracted twelve rounds Usyk caught Fury with a left which seemed to damage his nose; he would keep pawing at it, bothered by it, for the rest of the evening. As the fight started to settle into its early, feeling-out stages Fury began to meet Usyk’s pressure with hard right uppercuts, often to Usyk’s body. He held and leaned onto the smaller man—a practical, strategic take on affection, designed to start tiring Usyk out in time for the later championship rounds. Fury seemed happy to let Usyk come toward him and try to pick him off from range. By the middle rounds of the fight, it appeared to be working: Fury’s grander proportions looking like they might prove to be Usyk’s undoing; heavier shots starting to land more often, alongside more than the usual fits of taunting and mugging to the crowd; a sense beginning to form that Fury might even put a stop to Usyk’s night early. He was still having to work hard, however. While Usyk was clearly feeling Fury’s punches, especially heavy body shots in the fifth and a right to the head in the sixth which seemed—briefly—to stiffen his legs, he never looked in danger of hitting the canvas, or decisively wilting, and was forcing an uncomfortable pace.

Neither man had, until this night, encountered a problem in a professional ring to which they couldn’t find the solution. In the minute’s gap before the eighth Usyk kissed a crucifix handed to him by his cornerman—which launched various wild conspiracy theories on the internet about him using an inhaler—and came out with renewed vigor. He had more spring to his step and started to connect overhand lefts to Fury’s head. He ended the round having visibly damaged Fury’s face—a swelling began to form under the bigger man’s right eye, along with further damage to his nose. Fury seemed—for the first time—wincingly uncomfortable. If in the eighth Usyk got back into the fight, he won it in the ninth. With around half a minute to go, he got through with a huge left to Fury’s chin, which served to take away his legs. Fury spent the following seconds being hit from one corner of the ring to the next, his head rocked with punches, the great vessel of his frame veering around the canvas as if on a ship. He was punched into the corner and—momentarily—it seemed the referee was waving it off, but he was in fact administering a sympathetic standing eight count. Fury hadn’t gone down but only because his vast bulk hit the ropes each time he lumbered this way or that. He responded sheepishly to the referee’s instructions and was allowed to continue, the bell ringing to save him from further punishment at a point when he couldn’t have stood up to it. He was in another world, on another planet.

Fury managed to fiddle his way through a foggy tenth, where his legs were still a little shaky. That he recovered enough to be a threat in the fight’s final two rounds, and arguably even win the last, is to his credit and answered any questions about his remaining motivation at this late stage of his career. Usyk was declared the winner, on a split decision, having eroded Fury’s early lead with his explosive, violent revival—a verdict Fury railed against, claiming his rival had been favored because his nation is at war. It would, however, be ungenerous at best to pay much heed to words said in an immediate, concussed aftermath. The important fact is that Usyk is now the sole occupant of the seat at the top of the heavyweight mountain, his record still unblemished. He would dedicate the win to his nation and its children. “It was almost like destiny, wasn’t it?” Usyk’s cut man, Russ Anber, said later that night.

Ali once spoke of “the near room”—a sort of lawlessly alluring mental state he described to George Plimpton as full of “bats blowing trumpets and alligators playing trombones” that a fighter is occasionally aware of in the hardest moments of their hardest fights; to cross that threshold means committing to one’s destruction. Both Fury and Usyk will have caught glimpses of that place before, and if the contracts are honored they’ll fight a rematch in December where they may again move into its proximity.

There will be corners of the media who will use Saturday night to start their alternative history—one in which Fury was never any good; others who will delight in such a public rebuttal of his erstwhile claims to invincibility. I was reminded of the great Scottish sportswriter Hugh McIlvanney’s words when Muhammad Ali lost for the first time, against Joe Frazier, in another heavyweight battle of unbeatens: “They wanted a crucifixion, but if they think that is what they got they are bad judges of the genre. The big man came out bigger than he went in.” We don’t yet know how Fury will react to his first loss. For a man who has long been convinced there was no one good enough to beat him—a grand, lonely boast—it might be hard to start over. Or perhaps he’ll find a conflicted sort of company in knowing there is someone else like him, someone who’d been there all along.

Declan Ryan is a poet and critic in London. His debut poetry collection is Crisis Actor.

June 5, 2024

I Cannot

Licensed under CCO 4.0, Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Last year, a formal tone that sounded nothing like my speaking voice started to sputter out from my cursor and onto the page: “I cannot think about it now,” “I journeyed back to my abode.” Words elongated, and phrasings—strange ones—appeared. I watched the sentences extend, and noticed they were saying very little, but that they were saying this little in very mannered ways. “At the shore, attempting to reel in my kayak amidst the smooth stones and locally famous sea glass, I suffered a gigantic spasm of the muscles in my back, so painful I could not speak but to scream,” I wrote—not a terrible sentence, and not describing nothing, but when have I ever spoken the formulation “could not __ but to ___”? Or the word “amidst”?

When, last year, I saw in my prose that falseness and false formality, I wondered where it had come from. I seemed to be a few minutes away from using whence. I seemed to be searching for a rhythm that wouldn’t come, and reading overtatters of drafts later, I realized I was attempting to write prose in what was basically iambic pentameter, as if this classic formal constraint contained within it the key, the one key, to a sense of writing well, a sense so rare that year for me to find at all. From whence this sense of language-pressed-through-sieve? From where did it first flow, that impulse toward the cannot instead of the can’t, I wondered, and the immediate answer that occurred to me was, strangely but also obviously, the internet, which supplies phrases like “I am deceased” and “I simply cannot.” I thought to myself that I do not, anymore, use the internet to read very deeply.

Now, the internet can feel like a relatively arid version of its wilder self. I return to Instagram, where many nights this year I’ve revisited the video of the young man being possessed by an ancient burp who cracks his head hard into a garage door. Visual content dominates. But still, running alongside this video, and the many like it, are other digital testaments to experience—personal essays published in places fewer and further between, for less and less money, if any at all, places insistent on the very democratic, and also cheap, idea that all “I”s have a story to tell, and are simply waiting for their platform, that more content is better than less, and that writing is, in fact, “content” in the first place. If we are to look at, for instance, the Masterclass guide to writing personal essays, we are told, first and foremost, to strive for the importance of our own personal experience. A personal essay “serves to describe an important lesson gathered from a writer’s life experiences,” says Masterclass, and it should focus on a moment that “sparked growth.” Masterclass teaches us to write in an already-existent form in a proficient way. And it is a weighty idea—that all personal essays must be about growth-sparking moments. That all moments, written about, must be of importance. No wonder “cannot” essays, as I’ll call them, often seem characterized by what seems to be that particular stiltedness, that particular insistence on extension instead of contraction, that particularly “important”-feeling diction that I have noticed in my own recent writing.

We write “I cannot” instead of “I can’t,” we use formal tools of nomenclature. We might use white space, or a braided structure, to lend weight to otherwise innocuous phrases. We sometimes, or often, use the present tense, flattening us inside a moment in time alongside our narrator (I turn on the coffee machine. In the thick fog, I cannot see more than ten feet in front of my feet.) We use short, abrupt-feeling sentences (I walk to the store. [White Space] I buy glass cleaner. [White Space]). Our slight formality might turn towards the archaic—a friend recently sent me an essay that used the phrase “my monthly blood” to describe having one’s period.

In fact, we might use this kind of language in order to transmit a certain desired seriousness, like that carried by the word libation, otherwise seen/heard only on a certain kind of menu, in a certain blocky font. Indeed, a friend tells me libationhas been on the conversational rise since the early 2010s—about the time the “hipster-retro handlebar mustache,” in his words, peaked, and also around the same time that I lived in San Francisco, which felt like the epicenter of the mustache thing, the vegetable tattoo thing, the wood-grain thing. More than a decade later, I hear “libations” uttered casually by fresh-faced young men who do not, I think, mean to be serious. Yet neither do they mean to be ironic, exactly. I feel I recognize something similar in the word ladies, ever cheerfully condescending, ever hackle-raising—it too is on the rise, proliferating literarily at levels not seen since 1909, at least according to the Google Ngram Viewer, which notes 1822 as the high point for ladies, and 1978 or so as its low point (as of 2019, the word was used almost 200 percent more than in 1978). It’s like the language on wedding invitations, another friend suggests: attire instead of clothing, request the honor of your presence, tea-length. Like many phenomena noticeable for their formal gestures at nostalgic extremity—the starched high-collared dresses, breakfast cereal made from scratch, the handlebar mustaches—the slightly formal essays point toward, I think, the threat they are meant to oppose: a feeling that things are too much online, that things are too casual and must be elevated. Just as the suspenders and wood grain of 2010 gestured at, what, an increasingly digital sandedness to life’s corners, the formality-tinged essays of the 2020s gesture at a ubiquity of digital content made from reality; they are attempts to heighten or “craft” it into something seemingly more important, something smacking of authenticity in a way that is actually altogether very impersonal.

I am seeing someone else and we are done, he announced; My mother is looking at the television, which is on mute; in my third decade, I; Swimming has saved me over and over again. But this time it cannot; I am taking the long way to the airport to see my father; this is not a story I want to tell anyone else; I know that if I touch the sides they will be cold; I am trying to fix what cannot be fixed; I am anticipating . . . the gently pursed phrasings pile up, serious and austere, attempting, it sometimes seems to me, to sanctify something, to sprinkle a libation, really, across the digital altar, emphasizing the importance of this particular story, this particular writer’s life amidst the noise.

Amidst the tone of graven importance the writers of these essays, maybe there’s not much to say that feels new—or if there is, we are often side-stepping it. In her book Hole Studies, Hilary Plum points out how contemporary essayists, she says, write “I’ve been thinking a lot about . . .” and “then just virtuously mention a subject, not saying one thing of substance about it, moving on before we have to do any work.” On the flip side, there is the feigned overconfidence of aphorism, which supplies contemporary writers with what Adam Gopnik calls a “neat if slightly dubious finality.” Memory is a tantrum. Setting isn’t just place but time. Dying can be easy. These days, it’s harder to learn how to live. Aphorisms of this kind don’t always feel particularly exciting or convincing—they feel, instead, fairly rote, and like assertions the writer makes to establish a sense of authority when they don’t necessarily feel one.

Both overassertion and hand-waving seem to be sidesteps around saying something. Like that formal wall: Is it guarding something? It is as if it is constructed of exhaustion, and of the dregs of feeling, not feeling itself. And so, if the formality with which I seem to write, now—although I hope this essay is a kind of exorcism, to be honest—can be taken as a sign of something, I see it as maybe a guarding of energy. This kind of writing, somehow, has reversed, it has turned shallow amidst the depths of feeling of everything else. This type of writing has become, in this way, not a refuge, but a different manner of engagement. Perhaps formality—and this is another tic of the formal writers, by the way, the hopping, birdlike, never-settling perhaps—perhaps formality is simply a symptom of a writer seeing depth and gesturing toward it, but not really plumbing it, which would be messy, and uncertain, and risky. Not yet.

Recently, a poet friend mentioned that she thought the “I cannot” thing was the result of a flood of poets into nonfiction writing—“It’s all poets, now,” she said—who bring with them their Lyric. It all came back, she indicated, to rhythm, and to old and felt ways of stressing the importance of the material, as maybe my own failed strainings toward iambic pentameter suggested. She said that she would never use can’t in a poem—it would be too harsh, she said, not at all lovely. But I suspect there’s also a sense of guarding, again, with cannot—write “I can’t” and the “I” feels very bare and possibly, shamefully wrong, overexposed. It’s an idea that Gillian White gets at in her book Lyric Shame, which examines the “ambient shame” around and inside poems that feel “too credulous of [their] I,” maybe even too casual with its deployment. Indeed, writes Ben Lerner in Literary Hub, moving the argument toward contemporary nonfiction and regarding Claudia Rankine’s Don’t Let Me Be Lonely and Maggie Nelson’s Bluets, these essays, in their considerations of loneliness and alienation, actually “transpose” the lyric from “generic marker traditionally understood as denoting short, musical, and expressive verse” into “long, often tonally flat books written largely in prose.” “If a color cannot cure, can it at least incite hope?” asks Nelson in Bluets. And then a kind of aphorism: “We cannot read the darkness. We cannot read it. It is a form of madness, albeit a common one, that we try.”

Of course, “essay means ‘to try’ ” has become its own aphorism, so accepted among contemporary essayists that it’s easy to assume that all the lightly elevated language, the slight stiltedness to certain phrasings, are simply an extension of this idea—of trying to be heard, of trying to eke meaning from experiences we carry inside. Yet I can’t help but imagine, too, a different kind of trying: mundane, unsure, suggested, loose.

Lucy Schiller is an assistant professor of nonfiction writing at Texas Tech. Her work has appeared in The Iowa Review, the New Yorker, the Columbia Journalism Review, Speculative Nonfiction, West Branch, DIAGRAM, Popula, Essay Daily, and elsewhere. Her first book is forthcoming from Flatiron Press. She lives in Lubbock, Texas.

June 4, 2024

Top Three Rivers

The Nile River. Photograph by Vyacheslav Argenberg. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons, licensed under CCO 4.0.

“Top three rivers. Go.”

I wasn’t even sure I could name three rivers, let alone rank them, until Ruthie started rattling off her favorites. For most of dinner she had kept her twelve-year-old head buried in a stack of printer paper, only surfacing for the occasional bite of food. Her hair had grown into a long bob near her shoulders with a curtain of bangs that parted to reveal her face, resulting in us calling her Joey Ramone until her pleas of “Stoppppp” weighed more sincere than playful. She has since cut her hair.

There were eight of us in total: Ruthie, her parents, another couple, a gallerist and one of her artists, and me. It was a cold night in January, and we enjoyed a hearty meal of risotto, roasted vegetables, and salad. I had come to New York from Los Angeles to use a free companion flight certificate that was due to expire, and I was ten, maybe fifteen minutes late, prompting the low-hanging chorus of “Well, he came all the way from California!”

While I am not a regular, Ruthie’s dining room is one I have frequented over the course of her life, and it remains fondly vivid in my mind. It is a cozy, lived-in space full of both practical and whimsical elements that reflect her family’s sense of humor quite accurately. In the center is an oblong wooden dining table that doubles as a surface for homework between meals. The main source of light is an overhead barn pendant, mellowed out by a plastic kitchen colander placed over the bottom lip in order to dissipate the harsh glow of a bare bulb.

Behind the table is a border of cobalt blue paint framing the door that leads out to the backyard, as well as the window that overlooks it to the east. The wall flanking the dining table transitions into the living room, displaying art that doesn’t take itself too seriously—a few Martin Parrs, a Carroll Dunham, a print of a TV with a frozen still of Vanderpump Rules on the screen, and a few pieces by Ruthie’s artist father. It is a living, breathing room, malleable and fluid, constantly shifting to make space for wayward new additions that need to make sense somewhere, so they find a home on that wall. This time around, the latest piece of note was a small portrait our English friend had painted of Biden, the local opossum who had figured out the cat door and become an uninvited regular in their home. Ruthie named him.

It amused her to name this wild animal after our commander in chief, but I don’t know if at twelve she understood why it would be especially funny to adults that she would go with the name of the leader of the free world instead of say, Stinky, or Peanut. She had begun edging along the border of her childhood and her teen years, and that evening was the first time I noticed her occasionally flailing into one or the other.

We keep in touch via all the usual modern avenues, but a lot is missed when Ruthie is diluted to voice or text. Twelve is already an age when monumental changes happen seemingly overnight, and because I see her in such infrequent spurts it means I have no chance to acclimate gradually to them, and instead am slightly jarred when I discover her a little more empathetic or patient, worldlier or funnier.

Her curiosity remains childlike and genuine. She is still trying everything on, discovering what she likes, what she doesn’t, and what she’s indifferent toward, figuring out the world and her place in it. It’s refreshing, especially in contrast to the revolving door of adults the table has seated over the years, already settled on our chosen tastes and interests, leaving us with only nostalgia with which to frame ourselves.

That night, the adults discussed the Baltimore of a certain era and consequently The Wire, then we meandered further back to Sassy magazine, the heartthrobs of those halcyon years, and how we were all somehow friendly with various rockers of that patchouli era. We concluded that publishing was a den of sin, the art world was a den of sin, and that Hollywood was, well, you guessed it—a den of sin.

Ruthie started doling out sheets of paper around the table. She had been drawing a comic strip throughout the meal, workshopping a character with anger issues. He had Beetlejuice hair and a tic in which he would click his tongue against his front teeth, kind of like the thing dads do when they eat in public. Some of his speech bubbles contained tidbits plucked fresh from our conversation, and while the images were drawn by the hand of a child, her teasing was cheeky in a very grown-up way. We laughed with her, and she laughed at us. Her face disappeared as she flopped back under the secure shroud of her bangs.

We talked again about ancient history: the lineage of red hair through the Gauls, Gaelics, and Galatia, and she retreated out of boredom to the living room to play a game on her VR headset. In our quick reprieve from our PG audience member, we went straight into the seedy topics of sex, uppers, downers, and then, specifically, heroin. Those of us who once loved the stuff agreed that the high was defined by an awe of the simultaneity of everything. Ruthie knocked a rogue tambourine to the floor, deep in battle with digital zombies, then she returned to the table with a Seinfeld Lego set. It was a kit of Jerry’s apartment on a stage, and it was very detailed, complete with a bicycle, stocked with shelves of cereal, and a truss with stage lights running across the top. She seemed very proud of it, but less for the fact that she had assembled it and more simply because she was able to share it with us, almost like Hyman Roth passing around his solid gold telephone, or his birthday cake. Then came the rivers.

It’s always sad to leave these dinner parties, but this one felt particularly poignant as it came to a close. It felt like Ruthie had aged drastically over the course of the evening, and I could feel her inching towards tweendom. It felt as if it could potentially be the last time I would see this kid I loved so much as an actual kid. What if the next time around, Ruthie didn’t greet me at the door but instead I was shown in by some unrecognizable brute, vaping between one-word answers, telling me how my taste in music is trash?

Luckily, her track record so far is spotless, and each new version of Ruthie has only gotten better. Still, the future is terrifying because we tend to imagine the worst, and I forget that at the core she will always be Ruthie, sweet as pie, and that there’s no amount of haircut that can ever shrink her essential qualities. So I welcome all the coming variations on the theme that I love, and just so I’m prepared for next time, my top three rivers for Ruthie:

The Ouse—Ginny Woolf, come on.The Nile—play the hits.The LA River—it’s man-made but it’s mine.

Christopher Chang lives in Los Angeles.

May 31, 2024

Dorm Room Art?: At the Biennale

Walton Ford, Culpabilis, 2024. Courtesy of the artist and Kasmin, New York. Photograph by Charlie Rubin.

I touch down at Marco Polo on Wednesday afternoon, one among the many who have come for the preopening days of the Venice Biennale. The airport—with its series of moving walkways shepherding passengers toward the dock—will turn out to be the only place in the city where I manage not to get lost. The line for the water-bus into the city is easy to spot, and as we wait for the next boat to arrive I count fifteen Rimowas, five pairs of Tabis, and several head-to-toe outfits of Issey Miyake. The boat ride, unaccountably, takes an hour. I alternate between fending off seasickness and watching the Instagram Story of a microinfluencer who’d been on my flight and is already flying down the Grand Canal in a private water taxi.

My first stop after depositing my bags and downing two espresso is Walton Ford’s Lion of God. The show takes up the two full stories of a church-like building in the same square as the city’s opera house, which my boyfriend is telling me—with the sort of walleyed zeal that suggests it’s one of a handful of facts he memorized for the trip—burned down in the nineties. Inside, it’s surprisingly dark, the main floor cut up by temporary exhibit walls painted black, the lights so dim that the details of the building, and the historic paintings spanning the rest of the room, are almost completely obscured.

In other words, you have no choice but to turn your attention to Ford’s four enormous watercolors, which, despite the best of intentions, strike me immediately as somehow “dorm room.” Maybe it’s the richness of their color set against the black of the room, but I momentarily perceive these objectively impressive works (at least on a technical level) as velvet paintings. The subject is always the same—a lion with a skull in its mouth; a lion with a book in its mouth; a pentaptych of a thorn-impaled paw. Each painting seems to be a different scene from one unified narrative. It’s something biblical, clearly, and the name Jerome pops into my head, along with the fact that Venetian iconography is clearly lion-obsessed, but I can’t quite fit everything together.

Upstairs, a giant Tintoretto has been moved into the space specifically for the exhibit. It takes up the central wall, and shows Saint Jerome (I was right!) in a state of ecstasy as Mary descends from heaven. I stand before it, a sophisticated-looking group nearby. As it turns out, Ford himself is in attendance, and he strikes up a conversation with one of the women in the group. “I saw you looking at this one,” he says. He points out a faint, shadowed lion in the painting’s bottom right corner, which I’d failed to see, then gestures to the perimeter of the ceiling, where a few paintings have been carefully spotlit, highlighting the animals often buried in otherwise busy canvases. “I thought, what if you took all the people out,” Ford says, “and focused on the animals?”

That night, I plan to attend a party celebrating Frank Auerbach. I receive an email in the early evening, explaining that some guests are having trouble finding the Palazzo da Mosto and reminding me that the entrance is “actually down a very narrow, unmarked alleyway.” I manage to stumble upon the entrance, almost by pure luck—I see a propped wooden door in the distance, leaking yellow light.

In the main room, I learn that the palazzo, which has housed the same family for four generations, is also the site of the scene in The Talented Mr. Ripley where Matt Damon kills Philip Seymour Hoffman with an ashtray. I’m not exactly surprised—as anyone will tell you, Venice is a city of layers, a palimpsest. The room is lit, as far as I can tell, by rows of scented candles, the shadows they create giving everything a sort of unreal quality. I spot a few friends in line at the vodkatini bar, where overzealous guests are leaning forward and rocking the table. The bartender moves the table back and forth as a warning, sloshing a full vodkatini in the process. My friends and I watch as the crowd grows more boisterous, converging, eventually, on a vat of risotto and a tray of mini omelets that have materialized in a side room. “Germany is very good this year,” everyone is saying, “Germany is really amazing.” I wonder if Eurovision is on, or if there’s some wild economic news I’ve managed to avoid, before slowly gathering that this is in reference to the pavilion at the Giardini.

More people show up; more food emerges. A woman in a geometric hat spills her cocktail down my dress. I search in vain for the bathroom. I search in vain for water. Another round of vodkatinis. Someone says something about Auerbach’s impasto. Someone compliments my dress. I’m told the pope is coming. As the party wraps up, a woman clutches my arm, a smile on her face like a full moon. “It’s so perfect here,” she says, gesturing widely, as though she means to encompass in the entire city. “I don’t think it’s possible to get sick of a place like this.”

The next day I head dutifully to Germany. A long line has already formed, and once inside, I’m disappointed to discover there’s another, longer line to enter a little house within the pavilion. This, I take it, is the heart of the exhibit, and I join the sub-line, which has managed to grow in the meantime, looping around the little house. Admittedly, house might be the wrong word. It’s an ominous-looking, multistory curved structure, made of dark, claylike material. It’s speckled with windows, though they’re oddly reflective or maybe just tinted, and I can’t really see inside. After twenty minutes or so it’s my turn to enter the structure, and I find myself standing inside what appears to be an abandoned home. A few mute performers walk about aimlessly. A machine blows dust around. A spiral staircase leads me to the roof, where a naked man is lying corpsed against the wall. I’m unsure what to make of this. Back outside, I feel covered in a film of dust. I try to google the meaning of the little house, hoping for some early review that will piece it all together, but discover only that its walls are covered in real asbestos.

There’s more, of course, but it feels like more of the same—and maybe, I think, that’s the nature of an event like the Biennale. It’s surfeit; you can’t help but feel overindulged. You are always doing too much, and not enough. By the end of the week I’m listless and tired. On my last night in the city I’m shuffling home from dinner in the rain, stalled behind an elderly tour group, when the siren signaling acqua alta sounds. Workers begin setting up elevated walkways, and I watch a tourist take off her running shoes and wade barefoot into shin-deep water. My phone is dead and, convinced I’ve been walking in circles, I turn down a random alleyway and, for the first time in days, I am completely alone. I continue on as the siren fades into silence and then there it is: San Marco’s basilica, the square completely flooded, bright and still as glass.

Camille Jacobson is The Paris Review‘s engagement editor.

May 30, 2024

Feral Goblin: Hospital Diary

Hospital corridor. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons, public domain.

When I entered the emergency room at 3 A.M., I knew only that the fragment of crab shell in my throat could not be swallowed, extracted, or solved with marshmallows (the glottal escorts recommended online). The actual solution was morphine and emergency surgery; up until I recovered consciousness, my visit to the hospital represented some of the most pleasant hours of 2024. When I woke, it was to a body with several new ports of entry, established so that my most tender innards could be tethered directly to the hospital bed. My gown was essentially a garrote with modesty bib attached, and mysterious things had been taped to my arms and legs; a tube to nowhere emerged from one nostril. I spent what felt like multiple twilit days wriggling up and down the bed, orienting myself by proximity to beeps, until my exovascular system got so tangled the nurses (themselves attracted to beeps) came running. I had been out of surgery half an hour.

The nurses unwound me, retrussed me, and stupefied me with fentanyl just as a pack of surgeons materialized to deliver complex and consequential information about my health. A total of six surgeons comprised my “team,” and all six could have played background Kens in the Barbie movie. I remember humming to myself to drown out their talking; I do not remember repeatedly whispering “I’m asleep” while making eye contact with the lead surgeon, but I defer to his sober account. They summarized our morning: After extracting the fragment of crab shell in my throat, they found several smaller shards in my stomach, which they took for good measure. Then they glued shut the centimeter-long tear, as esophageal tissue is too fragile for stitches. They had pictures on their phones.

While the hole in my esophagus healed, the doctors commanded I eat by tube, and presently introduced the week’s single continuous meal: a beige substance in a wobbly bag that joined my proboscis at a threaded connection with which I was immediately desperate to tamper. My eating has qualified as disorderly since childhood, and my diet represents a deranged détente. I regard eating as a game to be won by wringing the most time and flavor out of the fewest nutrients. It is a game I play with vats of broth and salads big enough to stuff pillows; tubular delivery of calorically dense slurry to my stomach is absolute and demoralizing defeat.

The looming food replacement—Peptamen 1.5, manufactured by the Nestle corporation, who online brook requests for samples—resembled wood glue and smelled like vanilla synthesized by a chemist. I was scheduled to absorb two bags every twenty-four hours.

Forced feeding turned me into a feral goblin; I would not have behaved worse had I been hooked up to a bag of sewage. I clamped the tube with a bobby pin, but that set off alarms and invited scrutiny from the nurses; I then detached myself from the feed bag entirely, but I failed to find a stopper in time to keep it from leaking a buttercup puddle that fused my gown to the bed and earned me a vigorous, side-eyed sponge bath. Next I tried reprogramming the machine to feed me a single milliliter of substance every day (a thimble of sewage still vile but preferable to the utility bucket prescribed). The difficulty in this scheme was the vigilance required to restore the machine to regular settings every time a hospital employee entered my room. I considered confessing my interference to every nurse who looked as though she might “get it,” but I lost courage in rehearsal; there is no chill, low-key way to position either the death drive or the tenuous matrix of superstitions I relied on to distract from it. I doubted my ability to convince medical professionals that I alone am not helped but harmed by nourishment.

I had a very busy body in the hospital and, like an incapacitated president, could merely observe as its executive functions were delegated down the chain of command. The inefficiency of sustaining a life by committee is staggering; a single day in the hospital required the constellated efforts of a team of thirty. Incoming seemingly at whim were IV fluids, painkillers, antibiotics, medicine to cure me of salivation, and an enchanting pink papaya enzyme used to sluice my feeding tube. Besides hourly monitoring of my vital signs by Care Partners, nurses administered finger-pricking blood-sugar tests every three hours, a phlebotomist drew blood every six, and technicians irradiated my torso every morning at four. (Classical sadists managed the scheduling.) Last and sweetly least were visits from the Care Extenders, a fleet of hospital-issued teenagers in khakis who roamed the floor without supervision or particular skill. Every few hours one would appear in my room to ask if I needed “anything,” a category that seemed to include only ice chips and fiddling with the in-room iPad.

All of which is to say: anticipation of caregiving traffic made sleep impossible. I tried to watch TV but kept falling in love with the advertised food; I texted my friends asking to be DoorDashed crab salad, the greatest comedy masking the deepest pain, et cetera. As my mouth was airlocked without saliva, I repeatedly licked the only food I had in my possession, a wedge of Rice Krispies bar discovered at the bottom of an overnight bag last used at Christmas, but I found that in disuse my mouth had the native flavor profile of a limestone quarry. The more hours I spent awake, the longer each one got, until the interval between midnight and dawn dilated past the point of cohesion; I entered the realm depicted on childhood Trapper Keepers, a timeless void delimited only by a neon grid extending to the horizon. I jolted awake at the constriction of a blood pressure cuff and discovered my feed machine running, my bag of glue depleted. On the morning of my fourth day of hospitalization, I called the internal social work department and left a message inquiring into discharging myself against medical advice.

A surgeon-delegate arrived within minutes and dismissed all other hospital personnel in the room. His preamble contained three phrases that all meant “Now I will tell you the truth.” It was essential that I remain in the hospital, he explained, because while my esophagus had likely sealed cleanly, the slight chance that it hadn’t left me vulnerable to imminent heart failure in the wild. Just four more days, he said. But in the half hour since early release had occurred to me, it had attained inevitability, and I was pained to consider the prospect of four more days unbroken by sleep or solid food. They were willing to work with me, he said, in three different ways. He asked what I liked to do in real life.

Make tiny contraptions out of resin and fishing lures, shown to no one; incubate and raise various barnyard and exotic fowl; eat crab recklessly. Those were the real answers. Instead I tried to imagine what a wholesome autonomous human would say and came up with “Going to CrossFit class every day,” a counterfactual that if nothing else provided my surgeon with the opportunity to respond mercifully by ignoring it. “Do you like dogs?” he asked “We could try to schedule a therapy dog for you. Or how about Reiki? Or a massage?” I had expected a stick and so was unprepared for the carrot offered instead; I found I didn’t want to be a goblin anymore, and I agreed to the schedule of captivity. Standing in the threshold of my hospital room and readmitting the various people waiting to Care for me, my surgeon offered a final cryptic kindness. “I’ll let the nurses know you’re cleared for courtyard.”

It was the dog I wanted most, and I spent the day buoyed into tolerance of the hospital routine, giddy at the imminent visit. I suspended my campaign against nutrition, which freed me to sleep; when I awoke, it was with my capacity for appropriate behavior freshly restored, and I greeted even the 4 A.M. X-ray tech with the good news of my dog and sundry perks. “They said you’d get all that today?” he asked, then held up one finger, left the room, and remotely doused my torso with ionized photons. “Doctors promise anything to keep you from leaving early.” When the day nurse came on shift, she clucked and confirmed the technician’s skepticism; she had only ever seen a dog in the children’s ward and, moreover, did not care for dogs. “They cleared you for courtyard, though, so you can go down to the lobby after bloodwork at eleven.” She emptied a syringe of Pepto-Bismol into my wrist IV as I assimilated this news.

At the appointed time, and at a pacing reminiscent of movie scenes depicting the hours preceding coronations and swan songs, my ports were disconnected and my gown shed. Nursing attendants guided my raised arms through the armholes of a T-shirt and my feeding tube and head through the collar. I was granted an hour on the courtyard, gateway to the world.

I was through the courtyard and off hospital grounds within minutes, speeding both to maximize my time and avoid prolonged observation. Simply walking felt phenomenal; I met the sunshine, breeze, and variegated branding positions of corporate America with childlike wonder. In a grocery store, I gazed upon all my favorite snacks; in a coffee shop, I bought a single shot of espresso and then scurried away, holding it up to my face and huffing atomized caffeine. On a park bench, in my last ten minutes of liberty, I watched a rippling black pit bull slip her collar and sprint toward the grass, where she dove and rolled jubilantly. “Damn it, Khaleesi,” muttered her owner, an elderly man hobbling after her at top speed who nonetheless nodded kindly at my idiot grin.

I was discharged on schedule, three days and eight courtyard forays after admission. In tomograph and fluoroscope, my esophagus was once again a perfect tube, the luminous doodles of my digestive and circulatory systems crisply defined and exactly where they belonged. The surgeon who’d promised me the dog, scarce since our negotiation, arrived to perform the final step of my release, the removal of my feeding tube, and clearance to eat and drink. I received the most perverse mercy of the whole week when he shone a penlight up my nostril to determine whether my tube had been sewn into my nose. God being good, it was not. He told me to close my eyes and, with a resolve that redeemed all earlier treachery, pulled a foot-long and hideously hot silicone worm out of my nose. My sinuses burned with stomach acid, my discharge papers were signed, and I returned to the world with untrammeled glee.

Freedom and retrospection softened my memories of the hospital, and the next day I emailed the head surgeon to thank him for saving my life and allowing me to leave. Would it be possible to send me the photograph of the crab shell he’d removed, to be hung above my desk as a reminder of the banality of evil? Six minutes later, one of his nurses responded with boilerplate text and this chilling portrait of my enemy.

Kate Riley’s story “L. R.” appears in the Winter 2022 issue of the Review.

May 29, 2024

Anne Elliot Is Twenty-Seven

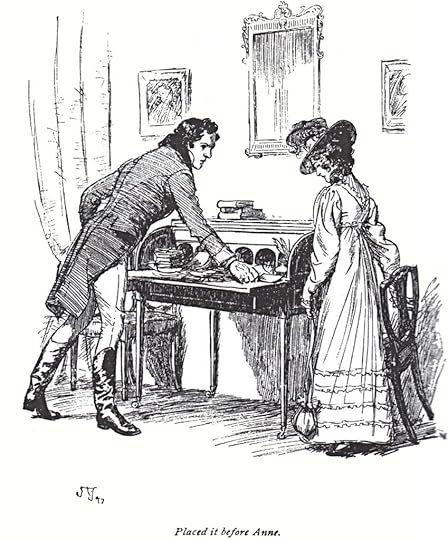

Hugh Thomson, engraving for chapter 23 of Persuasion, 1987: “He drew out a letter from under the scattered paper, placed it before Anne with eyes of glowing entreaty fixed on her for a time.” Public domain.

Anne Elliot is twenty-seven. She’s been twenty-seven since 1817, the year Jane Austen’s Persuasion was published. I, meanwhile, was somewhere around sixteen when I first read the book in my old childhood bedroom, with its green walls and arboreal wallpaper. I left the book alone after that, for almost twenty years, because it made me too sad. But when I turned twenty-seven I felt Anne Elliot slide into place alongside me. And when I turned twenty-eight, I felt her fall behind me.

Persuasion starts after the end of a love story: Anne Elliot and Frederick Wentworth were briefly engaged eight years prior to the book’s beginning. Under pressure from an older family friend, Lady Russell, who did not view Wentworth as a suitable social match, Anne jilted him. But the years pass by, and the two are unexpectedly reunited. Anne has never stopped loving him; Wentworth, now a captain in the navy, has never forgiven her. “She had used him ill,” Wentworth broods to himself, “deserted and disappointed him; and worse, she had shewn a feebleness of character in doing so, which his own decided, confident temper could not endure.” He’s done with her, he tells himself after they see each other again: “Her power with him was gone for ever.”

Of course, he’s wrong. Over the course of Persuasion, he falls back in love with her (or maybe just admits he’s never stopped loving her) and she proves her steadfastness. They forgive each other—he for her weakness and she for his hardness—and Wentworth will eventually throw himself on Anne’s mercy in one of Austen’s most romantic scenes, proclaiming himself “half agony, half hope.” She takes him back, they marry, and all is happily ever after. Why did this story, which is so happy, make me so sad? Why did I forget so many details of Persuasion’s story over the years, but unfailingly remember that Anne Elliot is twenty-seven? When I was twenty-eight, I told a friend that I was in limbo between Anne and Edith Wharton’s Lily Bart, who is twenty-nine. Now my Lily Bart year, too, has come and gone.

***

References to age pepper Persuasion’s early pages—I couldn’t tell you the ages of any other Austen characters off the top of my head, but in this novel, they are prominent and unavoidable. Anne’s shallow older sister Elizabeth is twenty-nine. There’s their father, Sir William, who “had been remarkably handsome in his youth; and, at fifty-four, was still a very fine man.” Austen makes the point that Elizabeth and Sir William look good for their respective ages very clear (while Anne looks prematurely old); but their youthful buoyancy indicates something insubstantial about their natures. Anne has aged because she is conscious of her own past and her own mistakes; her sister and her father’s lack of introspection makes them, in comparison, eternal children.

But why is she twenty-seven? Are we watching Anne Elliot be rescued from the cliff’s edge of spinsterhood? Is that why she’s twenty-seven? It’s one answer, certainly: Anne’s supposed to seem like someone who is too old to marry, whose life has passed her by because of her tragic mistake. She’s doomed to spinsterhood—until she receives unexpected salvation in the book’s final pages. This interpretation is propped up by the 2007 film adaptation, in which someone says that, at twenty-seven, he doubts she’ll ever marry. Readers today simply have to update her age to keep pace with inflation, and call her forty. Yet at the risk of anachronism, I’ve never found this reading that interesting, or even (forgive me) persuasive. Anne Elliot’s being twenty-seven does not loom over her like a sell-by date. And Elizabeth, who is “handsome as ever,” also does not seem consumed with anxiety over marriage.

Since they are not properly alive, people in books can be any age—they can be five hundred and two as easily as they can be twenty-seven. An age does not just fix a character in their book’s internal timeline; it establishes characters in relation to each other. In Great Expectations, decrepit Miss Havisham is, however improbably, in her mid-thirties when Pip first meets her as a boy, but if we understand her as somebody who has willingly thrown her youth away, her age makes a little more sense. Juliet, in Romeo and Juliet, is thirteen, which puts her firmly still under the control of her mother and father. Middlemarch’s Dorothea Brooke is nineteen, as is Jane Eyre, but their respective husbands are around forty-eight and forty. The near-thirty-year age gap between Dorothea and Mr. Casaubon is one of many signs that they are ill-matched in marriage; older, discouraged by his failures, Casaubon experiences her youthful enthusiasm almost as mockery. Jane’s Mr. Rochester’s age, on the other hand, marks him out as somebody who is old enough to have damage and a dark secret or two. The gap in their ages is a gap in experience. An older woman would recognize Casaubon’s insecurity, for instance, for what it is—vindictive resentment that cannot be healed by adoration. Inexperienced Jane offers Rochester the chance at a new life unstained by his past mistakes. (Or, at least, he thinks she does; things don’t turn out that way.)

But certain ages—numbers—do loom, and thirty is one. In other novels, we see this benchmark and others—the marrying age—exerting their own pressures on the plot. Lily Bart views the approach of thirty with palpable fear and desperation. “I’ve been about too long—people are getting tired of me; they are beginning to say I ought to marry,” she comments in the book’s early pages. For Lily, that the clock is running down is clear. But if one feels the tick tick tick of the clock while reading Persuasion, it’s not because its cast is running out of time. Anne is not afraid of the future. She’s afraid of the past.

More significant than Anne Elliot’s numerical age are the eight years that pass between her jilting Wentworth and their reunion. Eight years is a long time—more than enough time to forget an attachment, no matter how sincerely felt. “Once so much to each other! Now nothing!” she laments to herself at the same meeting where Wentworth thinks about how she did him wrong. “Now they were as strangers; nay, worse than strangers, for they could never become acquainted. It was a perpetual estrangement.” Anne is conscious of the happy couple that they had been and the ghostly happy couple they could have become. She is haunted by her real past and the unreal potential present.

In all of Austen’s novels, she commits herself—fully—to two incompatible truths. The first is that people never change. The second, that they can and do. Austen seems skeptical of reform; she takes people as they are, and how they are usually leaves a lot to be desired. Her series of almost-salvageable cads—there’s practically one in each novel—testifies to the ways that the desire to change (or the appearance of the desire to change) is much easier to summon than actual change. But most of her romantic couples have to forgive each other—sometimes for betrayals and misunderstandings that seem small potatoes (as is true, I think, of Elizabeth Bennet and Mr. Darcy); sometimes, as in the case of Anne and Wentworth, over much more serious matters. That forgiveness would be meaningless if it were not accompanied by real reformation on of character.

Persuasion, as a novel, depends on both Anne and Wentworth changing and remaining unchanged. When Wentworth says to Anne, “You did not use to like cards; but time makes many changes,” she responds “I am not yet so much changed.” Then she stops herself, “fearing she hardly knew what misconstruction.” She wants Wentworth to know she hasn’t changed, but she also needs him to know she has changed and will not break faith with him again. She needs to know he hasn’t changed, but to forgive her, he will need to change.

Or has Anne changed? After she and Wentworth are firmly reunited, she tells him that she’s not convinced she did the wrong thing by deferring to the advice of her elders, even if that advice was wrong. “If I had done otherwise,” she comments, “I should have suffered more in continuing the engagement than I did even in giving it up, because I should have suffered in my conscience.” Which might just mean that she was nineteen then, and that now, more than eight years later, she is no longer a child who should abide by the wishes of her betters. Both her dutifulness then and her choices now, she says to Wentworth, correctly represent who she is, the person that Wentworth has loved despite himself all this long time. She regrets what she did. But she would probably do the same thing again, if she were nineteen again. Luckily for her, we’re all nineteen only once, at most.

***

Anne Elliot is twenty-seven. When I was thirty, sitting with a friend in a noisy West Village bar, she said, I like Persuasion. It’s Austen’s novel about late-in-life love. Without thinking, I replied: Anne Elliot is twenty-seven. What? my friend asked.

It’s true, I insisted. She’s twenty-seven.

Fuck you, she said. (As I recall.)

When I first read Middlemarch, I was younger than Dorothea; now I’m just about halfway between her age and Mr. Casaubon’s. One day I’ll pick the book up again and discover that Casaubon, too, is in the rearview mirror. In one sense, keeping track of ages in this fashion is just a literary parlor game. I don’t need to be nineteen to get swept up in Dorothea’s passion or be in my late forties to understand Casaubon’s paranoia. But in another sense, it’s just one reflection of what it means to live alongside books, reading and rereading them. When I see Dorothea, I see not just the character but the versions of myself that responded to her. In these books, inevitably, I find ghosts of myself; I see where I was wrong; I gain sympathy for some figures and lose it for others. (I was, for instance, much more sympathetic to Casaubon back when I was closer to Dorothea’s age.) This practice might be “bad reading,” but it’s how I read nonetheless.

What gives Persuasion its “late-in-life” feeling is regret—which is represented, in part, through age. When Wentworth, engaging in a short-lived flirtation with another woman, Louisa Musgrove, chooses to praise her character, he compares her to “a beautiful glossy nut, which, blessed with original strength, has outlived all the storms of autumn. Not a puncture, not a weak spot any where.” While the quality he intends to praise is her firmness of character, what he really praises here is her lack of personal history. Indeed, a nut that never falls from the tree, which is never split open, is a nut that dies before it lives. Wentworth mistakes having never been put to the test for having never failed.

In one of Austen’s more vicious little jokes, Louisa will later jump off a high place expecting Wentworth to catch her. He does not. Even the unpunctured nut gets kicked off the branch eventually. Regret is a feeling we only really experience as we get older and discover our own capacity not only to make mistakes but to do harm. Wentworth, for instance, has much to regret in his treatment of Louisa, whose heart he trifles with and whose body he fails to catch. It comes out all right in the end, but that’s just luck, not the product of conscientious atonement.

I once went to a stage adaptation of Persuasion with an ex-boyfriend. A dangerous thing to do, you might think, but I recall no heavy subtext in the air from either of us. We had really, finally, at last settled into being friends. In the play, adapted from the novel by Sarah Rose Kearns, Anne is constantly replaying her last conversation with Wentworth before they parted. Kearns places this conversation on Anne’s birthday: thus Anne, when left to her own thoughts, lives out a seemingly endless loop of happy birthdays that grow more and more deranged as the show continues. Every day brings Anne further away from the things she can’t unsay and the choices she can’t unmake. Her very distance from her regrets leaves her stuck deeper and deeper in the past.

Here, Wentworth really does end up saving Anne—not from a future as an old maid but from her inability to break out of this cycle of self-reproach. Age isn’t just a number and a biological fact, though it is both of those things. Age also represents how far we’ve come from the things that seemed like they would last forever—and that, in lingering alongside us, do last forever as memories and as scars, even if we wish they wouldn’t. We lose everything to the devouring past eventually. But we keep it all, too.

The eight years Anne and Wentworth have spent apart are a real and irrevocable loss, one the novel makes sure we keenly feel. But had they stayed together, they would have had much to forgive one another for anyway. Like in the old screwball comedies where people divorce so they can remarry, what reveals their love to be sturdy and unbreakable is that once they broke it. Anne’s constancy is revealed by her betrayal, Wentworth’s devotion by his coldness. They both had to fall from their trees and grow so they could meet again—not as different people, but as precisely who they always were.

My ex-boyfriend and I went out after the show to talk about the adaptation and get a drink. We had a good conversation and went our separate ways. Then we got back together. (That’s the power of art.) Time is always turning the present into the past. But every now and then, when you least expect it, it brings back something you’d left behind. What happens after that—whether you make good on your second chance or reprise your old mistakes in a stupider key—is the rest of the story.

B. D. McClay is an essayist and critic. She has written for Lapham’s Quarterly, The New Yorker, The New York Times Magazine, and other publications.

May 28, 2024

At the Webster Apartments: One of Manhattan’s Last All-Women’s Boarding Houses

All photographs by Tess Little.

I am greeted by the same sight that greeted tens of thousands of young women before me, the same sight that greeted a younger self when my cab from JFK pulled up a decade ago, that greeted the department store girls arriving in the city with their belongings in trunks a century before that, and all the residents between and since: a red-brick facade towering over West Thirty-Fourth Street, its name proudly chiseled into stone, THE WEBSTER APARTMENTS.

In 1923, the New York Times described this facade—“its white trimmings, its wide and numerous windows.” Now the trimmings have dulled to gray. From the sidewalk, I can catch a glimpse of the chiffon curtains in those wide windows.

Charles Webster was the cousin of Rowland Macy and head of Macy’s department store. Upon Webster’s death in 1916, he left one-third of his wealth to build and maintain a hotel for single working women in Manhattan’s retail district—somewhere the Macy’s shop clerks could lay their heads at the close of each day’s shifts. Rent would be kept low enough for their meager earnings, with the apartments not run for profit. And so the Webster’s doors opened in November 1923 and, from then, its four hundred bedrooms were always occupied at near full capacity.

It was one among many such boarding houses established during New York’s great era of commerce and industry. But over the next century, as other women’s residences closed one by one, the Webster stood tall on West Thirty-Fourth, a monument to the old ways of living. Still women-only, still affordable—until, that is, the building was sold off last April.

I lived at the Webster roughly a decade ago, while working as an intern in a museum design firm just off Wall Street. It was the low rent that brought me there: $285 a week for a room, including bills, breakfast, and dinner (up from $8.50 to $12 weekly in 1923). The fact that the building was women-only seemed, to me, a historic quirk—a small sacrifice to live somewhere so central, so affordable on my intern’s wage. At the same time, I’d just turned twenty, I’d never lived outside of the UK before, I didn’t know a single person in the city. Perhaps I’d find friends among the other twentysomething interns staying at the Webster. Certainly, my mother was pleased I ended up there, safe among other women.

Over the years, the experience stayed with me; I began writing a novel set in the building and embarked on a research trip with the notion I might take another room. This was when I learned of the Webster’s sale. The residents had just moved out, and the new owners, Brooklyn-based nonprofit Educational Housing Services, were renovating—but they opened their doors to me so I could explore with my camera and notebook.

As with the organization’s other property, the building will be run as coeducational student housing. It isn’t being demolished, merely modernized—and more bathrooms will be added, to accommodate more than one gender. For now, though, the Webster Apartments sit empty.

LOBBY

I thought I’d find the place gutted, abandoned, but inside the lights are glowing. There are still beige couches, coffee tables, a vase of red flowers carefully positioned. The only traces of construction work are occasional holes in the walls, as though someone swung a hammer around the place to check what it was made of.

Just off the lobby lies a utility closet, and in that closet is a cupboard of keys. Most hang on numbered hooks, one for each of the bedrooms. They come in different styles, some silver, some brass—perhaps because replacements were cut, with residents losing keys over the decades.

PORTABLE TYPEWRITER, reads a label over one of the hooks. WINDOW BARS, says another.

It is hard to reconstruct the lives of the women who spent time here—the Webster’s old website, made in 2002, proudly declared “We are not a transient hotel,” but it was only ever a pausing place. Occupants were not “residents” but “guests.” During my time, a guest could stay for no less than a month and no more than five years. Such a stay will leave few traces—the guest packs her belongings, vacates her room for the next occupant, and it is as though she was never there at all.

Still, you can perform a kind of archaeology, learning the pattern of those lives through the Webster’s architecture, from newspaper articles, photographs, records of other, better documented, women’s residences. And then there are the memories. Beneath an article announcing the building’s sale on Hell’s Kitchen news site W42ST, an outpouring of comments: one woman who arrived at the Webster in 1962 from Cuba, another who lived here in 1979 while attending secretarial school. Someone else is looking for information on a woman who died here in the eighties.

No air-conditioning in the bedrooms, the former guests reminisce. One fan affixed, high. Meals taken together in the cafeteria, and the Lincoln Tunnel traffic disturbing sleep, just as it disturbed my own through the sweaty summer of 2012.

BLUEPRINTS

Behind the lobby, a warren of offices, a green garden room. Each door has been left unlocked. In one room I find sheafs of blueprints, records of all the Webster’s incarnations, piled and curling. The nearest blueprint, detailing an electrical modernization, dates to 1956. Every city is designed by architects, but Manhattan was made by them: stacking such a population on such an island was a feat only achievable with all these systems, calculations, decades of engineering.

The history of women’s boarding houses runs in tandem with the history of the city’s socioeconomic evolution. From the nineteenth century on, as the industrial revolution picked up pace, demand for female labor grew—at first in mills and factories, then in offices, as secretaries or telephone operators. Unmarried women flocked to the city to fill these vacancies, but they were paid far less than male employees and thus struggled to make rent. Hotels for working women were established to meet this need—and to address growing concerns of a moral crisis surrounding this influx of unbridled women. Unsurprisingly, then, the first women’s residences were religious endeavors, housing the needy while policing behavior. The wealthy benefactors of the Ladies’ Christian Union imposed strict rules on their working-class residents: mandatory bedtimes, morning prayers, codes of cleanliness.

After this, more houses were built to accommodate the hierarchy of female employment. There was the Trowmarket Inn in Greenwich Village for under-thirty-fives earning less than $15 per week, a “pleasing … restfully simple” home, as described in a 1909 article in The Designer and the Woman’s Magazine—this catered to workers from factories and milliners. There was the Hotel Martha Washington on Twenty-Ninth and Madison, established in 1903 for businesswomen. There was the Barbizon on the Upper East Side, which opened in 1927, for those with careers in the arts; in practice, this meant residents from wealthier families, the college-educated, actresses, models, fashion journalists. It’s the Barbizon that looms largest in the public narrative about female residences, dazzling others out of sight. You hear about that dollhouse, with its swimming pool, badminton courts, art studios. You hear about famous residents—Grace Kelly, Joan Crawford, Liza Minelli—sweeping through the marble lobby. You can study the Life magazine photo shoot of Rita Hayworth posing in the gymnasium, or read about the fictional Amazon Hotel in The Bell Jar, where Sylvia Plath’s protagonist threw her clothes off the roof, just as Plath threw hers from the Barbizon.

And then the Webster, for all the shopgirls. Over time, its guest demography shifted; by the twenty-first century, the Webster was full of fashion interns. (Only a short stroll to the Garment District, after all.) In the Martha Washington, there was a tailor shop, a millinery, a manicurist. In the Trowmarket and Webster, there were sewing rooms for residents to mend their own clothes.

IN THE BEAU PARLOR

While most working women’s hotels weren’t as restrictive as the Ladies’ Christian Union, there were still rules that policed reputation and respectability. On the whole, residents had to be unmarried, provide proof of occupation and character, and abide by various regulations. To the very end, last year, one law remained unchanged at the Webster: no men past the ground floor, unless for a brief visit (a father viewing his daughter’s bedroom, say) and only if accompanied by staff.

Beside the lobby sits a long line of alcoves—small rooms with only three walls. These were the “beau parlors,” designed to be watched over at all times. No gentleman callers on the residential floors—but they could be entertained here. The Webster’s cardinal rule was, they said, never about keeping women under lock and key. No curfews, not a convent. A 1917 New York Times piece reporting on Charles Webster’s donation ends with a quote from the directors: “The Directors of the Webster Apartments all believe that marriage is the ultimate goal of all single women.” Hence the beau parlor.

Along with the beau parlors, the original architects included another space off the lobby to host dances and lectures. Now a tall construction ladder sits in the corner of that wide room on what must have once been a stage. In recent decades, the beau parlors had become “meeting rooms,” decorated with diamanté-framed mirrors, chandeliers, aspirational slogans: DREAM BIG, STRIVE FOR SUCCESS.

When I lived here, courting seemed distant, foreign. I wondered whether men had dropped by with calling cards, how many beaus a girl could collect. I can’t remember ever witnessing guests entertaining men in the meeting rooms, or trying to sneak dates past the lobby. Instead, the building as a whole was courted: predatory club promoters knew hundreds of young women were living here, mostly foreign or small-town girls in the big city for the first time. You’d find flyers in the postal slots: LADIES FREE ENTRY.

And while the Webster’s strict rules kept men far from residential floors, they didn’t necessarily keep guests safe. Because you couldn’t bring a gentleman caller upstairs, you’d have to spend the night at his, no matter where he lived or how little you knew him. It would be revealed to the others the next morning: Who arrived at cafeteria breakfast and who did not. Who had woken up on Staten Island with no memory of how she got there. Who turned up at dinner a few days later, much to the relief of her friends.

ELEVATOR

The signs are still fixed firm in their frames, erratically capitalized: “Please Note: Male Visitors may not use Elevators without staff escort.” Until they were automated in 1963, the elevators had to be operated by Webster employees—another opportunity for monitoring residents. Only for the women, to ascend.

The first passenger elevator was installed in 1857 in New York City. Though initially an ornate novelty for luxury hotels, a few decades later the invention would make possible the city’s soaring heights, all those office buildings reaching to the clouds. From the Webster’s roof, you can see the Empire State Building, with its seventy-three elevators, looking down upon West Thirty-Fourth. If the city’s skyscrapers are symbols of aspiration, then the elevator is the individual’s ambition, their steady climb to the top.

Not all who stayed in women’s residences would make the metaphorical ascent. That painful gap between hopes and reality (for many, for most). In Lone Women, a 1957 series for the New York Post, Gael Greene profiled residents lingering on at the Barbizon—those for whom the lucky break or marriage proposal hadn’t come and probably never would. Greene herself had resided in the dollhouse a few years earlier, but she’d found a career and departed.

The younger Barbizon girls named older residents, with derision, “the Women.” I remember older guests at the Webster—a group of fifteen or so among the hordes of twenty-somethings. We didn’t give them nicknames, but we did call the building itself the Spinster, the Dumpster. We did ask each other: How could you wash up in a place like this toward the end of your life? A place meant for young women stepping out into the city, at the beginning of it all. We never considered that the Webster might have held opportunity for older women too—maybe these guests weren’t down and out, but enjoying rooms of their own.

Beneath one of the articles announcing the Webster’s sale, a comment from a retiree: Could the Webster explain how she might apply for residency?

CAFETERIA

Though built for “Lone Women,” the Webster was not a lonely place. Each guest had her private bedroom, and that was it. Bathrooms were shared, no kitchens for guests to use; breakfast and dinner were taken collectively, at specific times.

Online, Webster guests recall all those mornings and evenings and weekends together. We lounged in beau parlors watching The Bachelor and Gossip Girl, they say. We shared couches in the dark of the TV room, listening to the clunk of the vending machines behind. We lay in rooftop deckchairs to catch the August sun.

I once came across a photograph from 1934, and there was the same scene, fixed in sepia—the women chatting in the Webster’s roof garden, resting arms on each other’s legs.

Down in the basement, I pass the industrial kitchen, the engine of the place, with its steel machinery. From the corner echoes an eerie clink—the pipes, I tell myself. In the dining room, lights flicker, ceiling fans whir. Ominous, to enter a space designed for many and find it empty.

There are still cornflake dispensers, toasters, stacks of trays—all sitting in exactly the same positions they occupied during my breakfasts here. Each morning you would line up for the coffee machine. You’d learn which foods you liked (the yogurt and granola) and which to avoid (fried eggs, greasy in their ramekins). You’d find your friends at their usual table. And if, like me, you ran out of money every now and then, you’d also steal a few slices of cinnamon-raisin loaf, wrapped surreptitiously in a paper napkin, to toast at the office for lunch.

BEDROOMS

The Webster has thirteen floors in total. The second houses the communal TV room. Two relics nestle in the corner, telephone booths: local call 10¢.

Along the corridor from the TV room, all the bedroom doors ajar. My own bedroom was somewhere above this, but it was just like the others. The desk, sink, wardrobe, drawers, the single bed (naturally)—a setup not dissimilar to those captured in an archived Barbizon brochure or in early twentieth-century photographs of a YWCA home. Whether catering to the elite or the working-class, women’s residences reserved decorative flourish for the floors that men could enter.

Nowadays, descriptions of women’s boarding houses often concern themselves with men: where they were and were not allowed to roam, with the bedroom as the ultimate forbidden zone, the no-man’s-land. Little is said of women who didn’t seek male beaus—who may have found love, companionship, desire on the floors above. In her 1980 book Amantes (translated into English as Lovhers), the Quebecois poet Nicole Brossard writes the Barbizon as a lesbian-feminist utopia. Her task is announced within the text: “to find again every day life of lesbian / fictions of writing of obscurity.”

Brossard collages her poems with fragments from other women writers. The verses circle the female body, city landscapes, and slowly, through the layers, a story emerges. Her lovers find each other:

when midnight and the elevator

in us rises the fluidity

our feet placed on the worn out carpets

here the girls of the Barbizon

in the narrow beds of America

have invented with their lips

a vital form of power

In the Webster bedrooms, sheets and pillows are still strewn across the mattresses. Plastic roses stand in jars on every desk, along with a welcome note: Enjoy your stay.

Tess Little is a writer, historian, and Fellow of All Souls College, University of Oxford. Her writing has appeared in various places, including The White Review, The Mays Anthology, and posters outside a London tube station. She is currently working on a history of women’s liberation activism, and a novel entitled Girls! Girls! Girls!

May 24, 2024

“What a Goddamn Writer She Was”: Remembering Alice Munro (1931–2024)

Alice Munro. Photograph by Derek Shapton.