The Paris Review's Blog, page 27

July 5, 2024

The Nine Ways: On the Enneagram

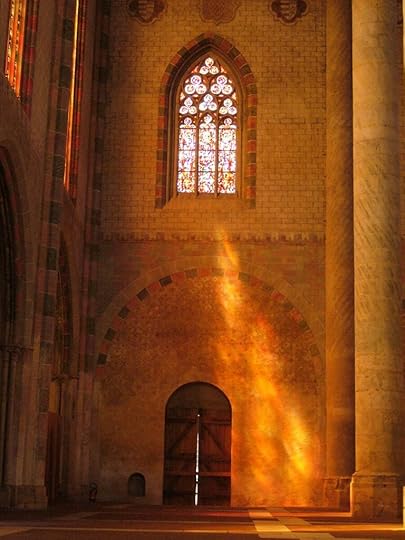

Light through stained glass. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. Licensed under CCO 2.0.

When I was a boy, the most obvious thing, in almost any situation, seemed to be something that wasn’t named. This unspoken thing usually had to do with desires or strong emotions that appeared to run under people’s words. In a stained glass window, the least striking element is often the very scene being depicted. People could have that quality when I was little, resembling stencils marbled with glowing hues. Where did their hidden longings end? Where did mine begin?

As I got older, I often lived like a cashier behind Plexiglas. I came to study people from a certain remove. That I had barely made my own wishes known, even to myself, became clear a few years before I turned forty, when, for the first time, I fell in love.

On an early date, the woman I fell for and I were joking about past lives. We sat at the counter of a breakfast place in Dallas, eating pancakes. She said she thought your previous life must relate to something you did a lot as a kid, because you were that much closer to the other side. I said I was probably a neurasthenic in a sanatorium in Europe writing thin volumes of philosophy. She said, “I think you were a dancer!” In fact, I love to dance, and as a child, danced all the time.

Around the time this relationship suddenly ended, my friend Sam told me about the theory of personality that is attached to the enneagram. If I had been introduced to this system seven or eight years earlier, I would have assumed it was stupid. Or if I hadn’t been so torn up and turned around, I might not have been desperate enough to take the enneagram seriously. What I found, however, was a deep and dynamic model, and one that spoke intimately to my intuition about what lurked beneath the surface.

In the months and years that followed, I would go on to consider every person I knew in the light of this system. I read extensively about the enneagram. I talked to friends about the model and then with friends of friends. I began to get referrals. Now I have a small practice where I do private enneagram-based coaching.

The word enneagram describes a figure that has existed since the time of Ancient Greece. It looks like this. There is some disagreement about who first appended a theory of personality to this shape. The Christian mystics known as the Desert Fathers, who lived in the Middle East in the third century, wrote about concepts very similar to those that animate the system now associated with the enneagram.

The first person to articulate a formal theory was the philosopher Oscar Ichazo, who presented the psychological model now called the enneagram in a series of talks given at the Institute of Applied Psychology in Santiago, Chile, and elsewhere in South America, in the sixties. In attendance was the psychiatrist Claudio Naranjo, who would later give his own interpretation of the subject at the Esalen Institute in Big Sur, California. From there, the enneagram was disseminated far and wide and appears today in a variety of forms, some more rigorous than others.

Ichazo’s core theory is that people, on the deepest level, wish to avoid a very bad feeling, an experience so awful it is what we imagine death is like. There are nine ways this terror can be imagined reaching us, and nine correspondent ways it can be avoided. The nine techniques of avoiding this universal fear are figured as points on the enneagram and exist in a complex and dynamic interplay with one another. In any individual personality, one of the nine is predominant.

The nine ways are often referred to using a kind of shorthand: 1 is the Reformer; 2, the Helper; 3, the Achiever; 4, the Individualist; 5, the Investigator; 6, the Loyalist; 7, the Enthusiast; 8, the Challenger; and 9, the Peacemaker.

It can be hard to pinpoint the right metaphor for the role these numbers are thought to play in a person’s psyche. The nine can be conceived of as parts, dimensions, or styles. I sometimes picture each number as being a corner in a very large room. Imagine the plane of this room’s floor is uneven, and the walls, as a result, are of irregular shapes and sizes. We may find something close to a natural comfort in one corner or in some nook nearby. The light from a window might amiably rhyme with that of a spot across the room. Some parts of the room might have high ceilings with bare white walls. Others, though narrow, might overlook a courtyard. If this place is big enough, its far corners might seem beyond reach or even nonexistent. We might hesitate to emerge from our favorite hideaways.

I offer this extended image to illustrate that while, as a numerical typology, the enneagram may seem like a tacky attempt to reduce human complexity, it is intended to do the opposite. By describing the contours of the corner we have mistaken for the full extent of who we are, the system invites us to enlarge our sense of self and to seek out renewed—really, restored—relationships with the world, other people, and our own life. In my case, that has meant seeking a better balance between the apparent philosopher and the hidden dancer. To return to the image of stained glass, working with the enneagram often means finding new stencils, in the mosaic of our lives, for the colors that already stream inside us.

I am moved by this model because it takes seriously how scary the process of being alive can be, and how possible.

Jacob Rubin, the author of the novel The Poser, is an associate professor at SMU. Piggy Bank, his first book of poetry, was recently published by Gold Wake Press. More information about his work with the enneagram can be found here.

July 3, 2024

Rorschach

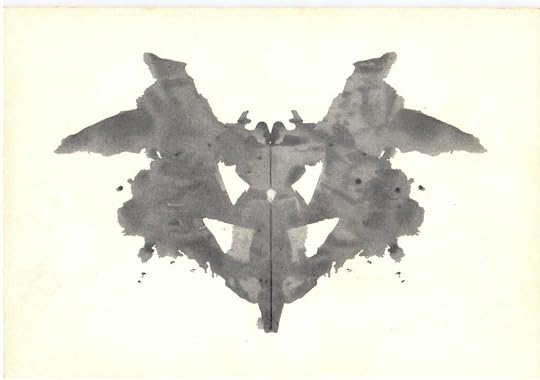

Rorschach plate that originally appeared in Psychodiagnostik by Hermann Rorschach (1921). Public domain.

Two monkeys with wings defecate suspending a ballerina whose skull is split. Her tutu reveals thighs from the fifties, toned. Their hands are on her poor wounded head; she has no feet. One of the monkeys, the one on the left, has a badly defined jawline. The woman has a perforated abdomen.

Two cartoon Polish men high-five. Their legs and their heads are red, to accentuate the fact that their heads are like socks. Their eyes are like their mouths, almost smiling at their mischief. They betray a body pact.

Two bald women with upturned noses, alien eyes, and prominent oval breasts. The separation between torso and hip through a knee and high heels propping up either two gardeners watering or two amphibians. On either side, fetuses in placenta or ghosts with their fingers to their lips, and with ribbons, evidently red, around their necks.

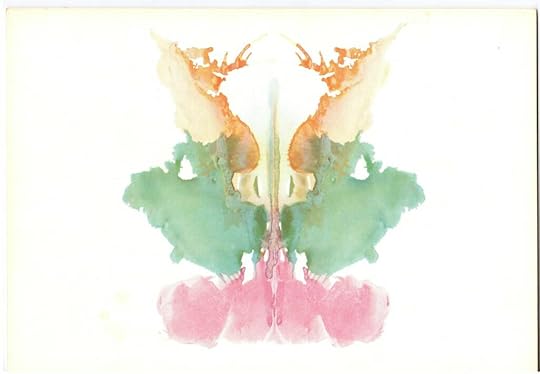

Rorschach plate that originally appeared in Psychodiagnostik by Hermann Rorschach (1921). Public domain.

Nothing. Or a monster with a half-hidden face, one eye visible, and something that splits its head. (Maybe a vagina.) You can see whiskers and cockroach pincers, Turkish shoes with stiletto heels and something unrecognizable between its legs. Or it’s a blurry monster that pulls them apart, and underneath, another monster or two that supports the first.

A butterfly walks with its feet warped, like it’s melting, dragging its wings. It has huge antennae and its back is to me; it sways to the right. Its expression is either looking off into the distance or perfect disappointment.

An extraterrestrial insect, thin, with four arms and two other small ones, its lower half unrecognizable. This part could also be two submarines with whiskered fish faces. It has a translucent shawl around its shoulders and its expression is of perversity or rage or desire or desire to kill.

Three open legs and a clitoris with a padlock. Could also be the profiles of two limp women with hands behind their backs.

Two possums climb a hill. At the base of it: two unhappy pigs and a playful devil or a very slim alien in an elegant shirt and suit jacket. A green bat with something else’s face, long, and above that a huge frog or anteater that consumes them all, with the help of the possums. This could also mean the frog ascends to heaven.

A swarm of hired pigs. Two Afrofuturistic hit women with tall hair wraps and two futuristic Ku Klux Klan members crossing swords.

From top to bottom: two emaciated men in hats dance, ludic, trophonic. Two insects fan them while riding on two other insects. Two marsupial mermaids drink a slurpee, intertwined, or play bagpipes while giving birth to fetuses in light or fish in amber. There’s a yellow-ocher ornamental set or something that doesn’t fully materialize; it has a torn root. Between them, something connects the mermaids’ nervous systems.

Rorschach plate that originally appeared in Psychodiagnostik by Hermann Rorschach (1921). Public domain.

Diana Garza Islas is a Mexican poet. A selection from her poem “Section of Adoring Nocturnes” appeared in the Summer issue of The Paris Review. Her Black Box Named Like to Me, in which this poem will appear, will be published by Ugly Duckling Presse in fall 2024. This poem was translated by Cal Paule. Paule is a translator, poet, and gender studies teacher.

July 2, 2024

The Host

I took the day off work to cook. Dad wore my apron and made the charoset and complained about how long it took to cut that many apples. Mom told me the soup tasted like nothing and made me go to Key Food to buy Better Than Bouillon. They were visiting New York to see my new apartment for the first time. Mom had always been in charge of preparing this meal when I was growing up, but for the first time, the tables were turned: I was hosting and we were eating at my house. She was older and more disabled now, which meant she could no longer use her hands to chop carrots and celery and fresh dill. So instead, she sat on a cane chair at the kitchen table she had just bought me from West Elm, tossing directions my way like a ringmaster.

Everyone said Passover would be weird this year. How could it not be? Tens of thousands of people were being systematically starved in Gaza at the hands of Israel. Our government was helping, weaponizing American Jews in its effort. It felt wrong to celebrate by eating ourselves silly.

I kept thinking about that one line—“Next year in Jerusalem.” It’s a line Jews have been reciting for thousands of years, way before the Nakba and the establishment of the state of Israel. But when I was growing up, I associated it with the directive that camp counselors and youth group educators had given me: to connect myself with Israel; to visit the country, “the homeland”; and to move there, should I be so inclined. This was a suggestion I now felt affirmatively opposed to, and resented having ever been taught. I didn’t want to think about propaganda at the dinner table. Whoever read this line aloud, I felt, would be encouraging the rest of us to contribute to a tragedy of displacement and violence.

By sundown, I was drinking my second cup of wine and Dad was studying THE NEW AMERICAN HAGGADAH so he could lead the seder in an abbreviated way for my friends, most of whom had gone to Catholic high schools and Jesuit colleges. Waiting around hungrily and impatiently until they arrived, Luke punctuated the silence by telling my parents the story about the time he enunciated the ch in l’chaim in front of an entire courtroom.

“Be there in 5-10,” Tim texted the group chat. “Princess Jake demanded an uber.” Tim had sourced a 6.6-pound cut of brisket from his workplace, a meat distributor specializing in biodiversity and humanely raised animals. Jake had cooked it with carrots and spices, using the skills he had been honing at his workplace: a restaurant in Greenpoint where the prix fixe menu started at $195 without the wine pairing. Zach came with the shmura matzah—“artisanal,” he called it. Eleni came with the wine. Tim arrived wearing a vest right out of Fiddler on the Roof. We call it his Jewish outfit. We all sat down at my new, big, rectangular table, me at the head and my parents at the other end. The dining area had two big windows, and the light was nice and yellow as the sun started to set. This was the first time my parents would meet these friends, some of my closest, and I was eager for everyone to drink their wine and settle in, for any awkwardness to melt away.

“ ‘Haggadah means “the telling,” ’ ” Dad began, reading from THE NEW AMERICAN HAGGADAH. I had asked Mom to bring the books from home, the ones stained with Manischewitz, that were blue, covered in paper jackets, and produced by the Maxwell House coffee company. But she couldn’t find enough for the nine of us, so instead she’d ordered copies of THE NEW AMERICAN HAGGADAH from Amazon. This edition was supposed to be “conventional.”

Lauren rolled in late with the latkes. Dad had been reminding me that latkes were not a Passover food but a Hanukkah one. I’d asked her to make them anyway, because everyone loves fried potatoes, and Lauren was an expert, having hosted a latke party every year she’d lived in New York. “What’s the difference between crème fraîche and sour cream?” Mom asked, plopping a spoonful of the former onto her steaming potato pancake.

“One is French,” Tim said.

“ ‘The Seder is a joyful blend of influences which have contributed toward inspiring our people, though scattered through the world, with a genuine feeling of kinship. Year after year, the Seder has thrilled us with an appreciation of the glories of our past, helped us to endure the severest persecutions, and created within us an enthusiasm for the high ideals of freedom,’ ” Dad read from THE NEW AMERICAN HAGGADAH. We took turns reading, as if we were in a classroom. The bottle of red followed.

“ ‘Maror, a bitter herb such as the horseradish root, reminds us of the bitterness of slavery in Egypt,’ ” Lauren read.

Jake went next. “ ‘Z’roa, a roasted lamb shank, reminds us that during the tenth plague the Jews smeared lamb’s blood on their doorposts.’ ” Ours was a chicken bone, cleaned and blanched.

“‘Beitsa, a roasted egg. In ancient days … our ancestors would bring an offering to the Temple,’” Luke read. Ours was raw, not hard-boiled.

“ ‘Charoset, a mixture of nuts, apples, sugar, and wine, reminds us of the mortar used in the great structures built by the Jewish slaves for the Pharaoh in Egypt.’ ” That one was me.

“ ‘Karpas,’ ” Tim read, in an outside voice, “ ‘a green vegetable such as parsley, reminds us that Pesach occurs during the spring.’ ”

“ ‘Hazeret, romaine lettuce, is on the Seder plate because it tastes sweet at first but then turns bitter,’ ” read Eleni.

“ ‘Some families have adopted the custom of placing an orange on the Seder plate,’ ” Mom began. “ ‘This originated from an incident that occurred when women were just beginning to become rabbis.’ ” I cut her off. We didn’t have an orange.

“What’s the orange?” Tim asked.

“It’s for women’s liberation,” I summarized.

“And we don’t have it?” he exclaimed. His teeth were purple from the wine.

I didn’t put an orange on the plate, because when I was growing up, we didn’t put an orange on the plate, and besides, my plate didn’t have a spot for an orange.

The last bottle of wine we opened was a dessert wine from 2016, which someone had brought to our apartment the weekend before, for a housewarming party. Tim made us swish our glasses with a little water to make sure we tasted the pours in all their purity. He planned to leave New York soon for Berkeley, where he would work on a wine harvest with a guy who wore a trucker hat. “This wine is made of dried grapes,” he said, “something you might drink at a christening ceremony.” It goes down thick like cough syrup, and tastes sweet like honey. It reminds me of that one time I tried mead.

My head was buzzing. I hadn’t had any water, though I had had several glasses of wine, as THE NEW AMERICAN HAGGADAH had commanded me to do. I examined my glass, the streaks of pink wine struggling to climb down its mouth, viscous from 2016 raisins. I was about to start clearing the plates when I realized that in doing the Reader’s Digest–style Haggadah, we’d skipped “Next year in Jerusalem.” I wondered if Dad had done this intentionally, but I wasn’t inclined to give him that much credit. I surmised it was probably an accident, an oversight caused by hunger and eagerness to get to the end. I didn’t bring it up. Perhaps the better way to think of it was as a coincidence, I told myself: a collision between my anticipation and Dad’s blunder, resulting in an outcome fortuitous for my psychological well-being. And this was the way it should be. After all, I was the host.

Alana Pockros is an editor at The Nation and the Cleveland Review of Books. Her writing has appeared in the New York Times, The Baffler, and elsewhere.

July 1, 2024

Three Letters from Rilke

Paula Modersohn-Becker, Still Life with Fried Eggs in a Pan, c. 1905. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Rainer Maria Rilke and the Expressionist painter Paula Modersohn-Becker met in the summer of 1900 in the German artists’ colony of Worpswede, which lies to the north of Bremen in a flat, windswept landscape of peat bogs, heather, and silver birch trees. Born just a year apart in the mid-1870s, Modersohn-Becker and Rilke were trailblazers in art and poetry at the dawn of the twentieth century. Their correspondence bears witness to their lively, ongoing dialogue and underlying creative affinities. Modersohn-Becker’s haunting portrait of Rilke, and Rilke’s meditative poem “Requiem for a Friend,” written in the aftermath of Modersohn-Becker’s untimely death, commemorate the importance each held in the other’s life.

Below are three letters from Rilke to Modersohn-Becker, written late in the year 1900.

—Jill Lloyd

Schmargendorf, Misdroyer Strasse 1

25 October 1900

My apartment has just now been completed. I don’t know which object did it; suddenly everything quietened down and it immediately became inhabited and familiar, as if no longer new—and yet … I would very much like to tell you how everything is, and where and why things are the way they are. Well, there is a small, unremarkable entryway, and a kitchen that will become interesting due only to my daily attempts at cooking (I have to prepare everything myself!); from the entryway you step through a small door and under a dark red curtain of heavy, woven linen (sold at Bernheimer’s in Munich as toile japonaise) into my very large study. There is a huge three-part window partially wedged into a bay as wide as the room itself. To the right of the bay, a glass door leads to a small balcony, while on the left the bay is joined by a blank wall to the wall of the study. Underneath the window there is a broad bench covered with a blue-and-red blanket from Abruzzo(!), and two steps in front of this bench, in the center of the room, is the main desk. There is a second, quite long desk set up as a working table for evening tasks—independent of the window, at an angle in front of the stove, and diagonally blocking the corner. To the left of the large window there hangs a narrow rug with a colorful border that keeps that corner dark, and in front of it stands the yellow samovar on a Russian base, surrounded by some Russian things, images, and holy icons. A very broad chair covered by a good, antique Turkish rug connects (to the left of the wall) to the cupboard for the samovar so that it’s easy to put down one’s glass of tea there. The Turkish blanket is stretched up the wall to the so-called ‘Rubens’—the Adoration of the Magi (oil painting—old, 2 meters long, 47 centimeters high)—and provides the backdrop for the best heirloom: a family crest in a precious silver frame. Then there is a small green table where I have to eat what I cook—and a small sideboard. Since I had to make do with a lot of existing things, including the gentle and not at all obtrusive wallpaper (dull yellow with blurred, quietly swaying carnations in pale red), I created particular backgrounds on which the pictures are hung and to which they are all connected in some way or other: for example the Turkish blanket underneath the crest and, on the opposite wall (which is dominated by an eight-unit bookshelf with an attached narrow bench), a precious green-and-gold cloth on top of which I have placed pictures of ancestors and forefathers… But what is the point of telling you all this? I realize that it will not amount to much more than what can be gleaned from a school essay or from old-fashioned travel accounts, or at best I will reach the level of stage directions for a theater … but I did not want to give you those, Miss Becker, but rather (I realize it late enough!) something of the play that is performed in this room, among these things, with them, for them … action, action! For heaven’s sake no description! And the play? … perhaps it hasn’t started yet?

Oh, my dear friend,—now the stage is truly set and, since it has been built of more than cardboard, it will probably last for a while … there are chrysanthemums; at the moment I don’t know where they are, but it calms me to know that they are here. It is evening. Silence. It seems almost impossible that you will not simply appear in my room at this moment—since everything has been set up and the pictures are hung on walls that, seen from the out-side, have now become the walls of my little home. I am waiting: waiting for you and for Clara Westhoff and Vogeler and for Sunday and for the song … and nothing is going to come. I know that nothing is going to come, and yet I wait. I am almost afraid to wish for others to come—there are the Russians with whom I am supposed to be working, and very seldom anyone else. But one morning I will truly wish for it and start working. Today, however, on this first evening in the finished rooms, I may just permit myself to sit—to be filled with longing and nothing else. My thoughts roam among your houses. My heart is suspended somewhere in the wind and rings out. My hands rest open and empty, like half shells from which the pearl has been removed. But do not mistake this for unhappiness, but rather for a kind of celebration that is gently ushering in my winter. I am grateful when I think of all that.

Yours, Rainer Maria Rilke

Today I am sending you a copy of the Revue de Paris with the play Mirage by George [sic] Rodenbach;—do you remember? And my kind regards! Also for your sister Milly and your little sister.

***

Schmargendorf

October 28, 1900

You have a knack for making letters as beautiful as evening hours. I read your letter frequently, and you should read and treasure what I wrote in response when you receive it, in the evening.

Strophes

I am with you, you Sunday evening ones.

My life is radiantly glowing and bright.

I am conversing, but compared to other times

all words have fled my lips and mind,

so that my silence rises up and blooms.

For these are songs: a beautiful silence of many,

that rises up from one person in rays.

The violin player is always alone,—

And, among the others, the slim player

is the most silent one, the one who does not speak.

I am with you, you gentle and attentive ones.

You are the columns of my solitude.

I am with you: do not give me a name,

so that I can be with you even from afar …

Just as great, sprawling gardens

sometimes bear words of foreign woods

on their quiet, darkening paths …

You are quite close to how I feel. I am

not mistaken. This hour now resembles

the hours with the white background.

Around me, the silence resounds with many sounds.

Music! Music! Orderer of sounds,

take what is scattered here at dusk,

lure pearls, rolled away, back onto strands …

Each thing locks in a prisoner.

Go, music, to each thing and lead

out of every thing’s doorway

the longtime fearful figures.

In pairs that hold each other’s hands

they follow you and go along the measures

with which we count the hours deep,—

they go, regally, their heads in wreaths,

from our rooms which had forgotten us.

I am with you, who listen to the sound,

that always hums and for which we sometimes exist;

we lost our fear that it will fade away.

Music is creation. Soul of song,

many things you turn into a structure,

by entering into those many things.

With you all women are one woman;

you link those—who are girls like silver rings

into cool chains that tie together spring.

To boys you give a sense that they could find a

spot toward which the world extends,

and old people already blinded by the day

live on only because they lean on you.

And men have longed for you.

I am with you. Among brothers, among trees,

one is as calm as when amongst you all.

I glean from dreams this sense of feeling soothed:

this being-without-fear of missing something

and this pleasure taken in what one knows.

Simple existence, offered to the heavens,

like ponds that stay forever open,

telling more beautifully of the wind’s experience,

and holding days and evening breeze,

safe above the abyss that is eternal.

I am with you. Am thankful to you both

who are like sisters of my soul;

for my soul wears a girl’s dress

and its hair is silken to the touch.

I rarely glimpse its cool hands;

for behind walls it lives quite far away,

as if in a tower not yet sprung free

by me, and hardly aware that I will arrive.

But I pass through the winds of earth

toward the rising wall,

behind which, in uncomprehended grief,

resides my soul … You know it better;

you’ve seen it, more familiar than myself.

You are the sisters of my bride.

……………

Be good to it.

Be kind to it, the blond sister here.

Speak to it with the rising moon.

Tell her of yourselves. Tell her about me.

I am waiting for a very beautiful hour, and the most beautiful, most open, and most receptive that arrives I will carry to Maid. For you must measure my capacity to give against what I have received. I am an echo. And you were a great sound whose concluding syllables I repeat from afar. Give my regards to Clara Westhoff with this Sunday letter.

Yours, Rainer Maria Rilke

***

Schmargendorf

November 5, 1900

How gloriously my place is turning out for me. Imagine, dear Paula Becker: I had on my desk a copper pitcher with slowly wilting dahlias the color of old ivory, just so that all that was needed to add to them to create a miracle were these fantastic and wonderful cabbage leaves. The miracle occurred and worked its magic.—On the bench attached to the bookshelf there was a tall, narrow vase with a few branches of rose hip arranged with heavy clusters of red rowan berries, and the fir branches were ringed by great yellow and golden chestnut leaves that are like the spread-out hands of autumn wanting to grasp the sun’s rays. But now that the sun’s rays no longer plod along but have grown wings, no chestnut leaf is going to catch a ray. Everything around me (I mean to say by means of this list) was prepared to receive the autumn with which you surprised and delighted me. There was already a spot ready, arranged by destiny, for each piece of your abundant autumn. Including the chain of chestnuts. Only in my house it does not hang on the wall; I sometimes take it out and pass it through my fingers like a rosary (you know about these Catholic prayer beads?). For each bead of such rosaries, one has to recite a particular prayer: I emulate this devout rule by thinking with each chestnut of something lovely that refers to you and Clara Westhoff. Which led me to discover that there are not enough chestnuts.

The first days of November are always Catholic days for me. The second day of November is All Souls’ Day, which up to my sixteenth or seventeenth birthday I had always, no matter where I was living at the time, spent in churchyards—often visiting unknown graves as well as graves of relatives and ancestors, and gravesites that I could not make sense of and that I had to think about during the lengthening winter nights. That was probably when the thought first occurred to me that every hour that we live is the hour of death for someone, and that there may even be more hours of dying than hours of the living. Death has a clock’s face with countless numbers … Now it has been years since I stopped visiting graves on All Souls’ Day. Now I only make a trip to visit Heinrich von Kleist out in Wannsee at this time of year. He died out there in late November; during a season when many shots resound in the empty forest, two heavy shots from his gun also rang out. They barely differed from the other shots, though they were perhaps a bit more forceful, shorter, more breathless … But in the heavy air all sounds become similar and grow dull amidst the many soft leaves floating down everywhere.

But I realize that this is no letter for you, and actually not one for me either. I long for you, dear friend. Farewell.

Yours, Rainer Maria Rilke

Soon I’ll copy for you the song “You pale child, each evening … ,” and then I will send it to you. It does not even exist if it’s not in your possession—especially that one, which first came into being with you, so to speak. During one of these evening hours. Please send my regards to Clara Westhoff and your sisters Milly and Herma. And do not be upset about this letter. Different types of letter will come again!

The Modersohn-Becker/Rilke Correspondence , translated by Ulrich Baer and with an introduction by Jill Lloyd, is forthcoming from ERIS Press this month.

Ulrich Baer is the author of of What Snowflakes Get Right: Free Speech, Truth and Equality in the University; Spectral Evidence: The Photography of Trauma; and The Dark Interval: Rilke’s Letters for the Grieving Heart. He teaches at New York University.

Rainer Maria Rilke (1875–1926) was an Austrian writer best known for his poetry collections The Duino Elegies and Sonnets to Orpheus, and a novel, The Notebooks of Malte Laurids Brigge.

Jill Lloyd is an art historian and curator. She has coedited numerous exhibition catalogues and is the author of German Expressionism, Primitivism and Modernity and The Undiscovered Expressionist: A Life of Marie-Louise Von Motesiczky.

June 28, 2024

“Perfection You Cannot Have”: On Agnes Martin and Grief

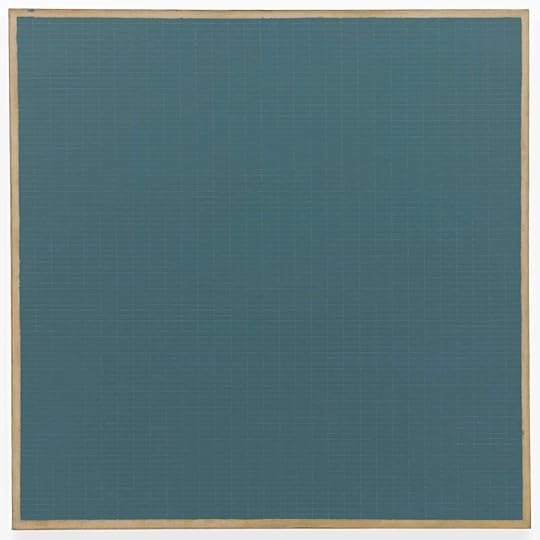

Agnes Martin, Night Sea, 1963. The Doris and Donald Fisher Collection at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. Copyright the Estate of Agnes Martin / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photograph by Katherine Du Tiel.

Sitting in the octangular room at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, surrounded by seven of Agnes Martin’s grid and row works, I settled first on Night Sea (1963), a turquoise blue painting laced with shimmering lines—a near-faultless impression of an ocean, as if illuminated for an instant by the moon or a lighthouse. Drift of Summer (1965), with its off-white grid, appears like a notebook crying out for ideas. Even the bright and broadly lined work Untitled #9 (1995), which Martin completed in her eighties, looked to me from afar impeccable, its colorful sections seeming to have been generated by a machine or a god. Here the spiritual resurfaced. In Martin’s grids and rows, the possibility not only of excellence—the apparent perfection of her lines—but of a grander, near-divine plan.

A decade ago, my mother died of metastatic melanoma, an illness that lasted about four years. It dragged our family across the country for radiation trials; it made the question “Where are you staying?” frequently answerable with either “Hospital room cot” or “Bed in hotel.” In the wake of her death, I sought out Martin’s grids. I saw them at SFMOMA but also at Dia Beacon, the Whitney, MoMA, the Philadelphia Museum of Art, Tate Modern, and the Peggy Guggenheim Collection in Venice, where Rose (1966) remains my favorite work of hers. The painting’s title at first seems a bizarre one: no flower is figuratively depicted. But in the painting’s cream-colored acrylic, as the lightness of its lines disappear in parts, a natural order underlies its beauty (a rose being, perhaps, beauty’s essence).

Combining linear rigidity and spatial abstraction, in Martin’s works I saw an idea of the world that is guided by plans and sure outcomes—a world made whole again. Martin’s own life was imperfect and traumatic (though she’d likely bristle at the word): she said she was raped as a girl on four occasions, dissociating each time; she lived a seemingly lonely existence, chafing against middle-class sensibilities. I figured she desired, like me, exactness and rightness, apparent salves for the broken. I supposed this aspiration was a core reason for her grids and lines. In fact, she suggested something of the opposite: to view the world as though it were perfect but to understand that it is not—and to see that perfection need not be pursued. “Perfection is not necessary. Perfection you cannot have,” she once said. “If you do what you want to do and what you can do and if you can then recognize it you will be contented.”

This spring I flew to Chicago to see three drawings of hers at the Art Institute. Some were not on view so I made my way to a back room, where a staff member had placed them in front of a bookshelf. Looking at them—Untitled (1961), Untitled (1964), and Untitled #8 (1990)—I got closer than I’d been before to any of her artworks.

Untitled (1964) was something of a mess. The work’s woven tracing paper is so thin that, as I got nearer to it, it looked increasingly ready to collapse beneath the weight of Martin’s pen and pencil and watercolors. The grid’s lines, bathed in a pink-red watercolor, appeared to be drawn and redrawn, the paint escaping from its confines. Untitled #8 (1990), however, is a pen-and-pencil-drawn piece with seemingly clean lines. On the internet, the drawing’s lines looked to me idyllically straight, Martin’s framing penwork weighted the same throughout, with a pencil-drawn grid appearing almost mathematically infallible. Indeed, this is how I’d considered Rose and so many of her other works: forms of excellence, a rightness I too could achieve.

But here, up close, in this silent back room, I saw that Martin had let her pen linger in a corner, pooling a light collection of ink. On the upper part of the grid, her pencil had skipped over a small bit of paper, creating a blank space. The drawing had looked mechanical from afar. Closely viewed, it was flawed and human.

Cody Delistraty is a journalist and writer. He is the author of The Grief Cure: Looking for the End of Loss.

June 26, 2024

37-08 Utopia Parkway: Joseph Cornell’s House

Screenshot from Google Street View. Captured in April 2023.

I said, What does it feel like in there? What do you mean, she said. I said, For example, is it light or is it dark? She said, It’s light by the windows. And then she said, It’s airy if the windows are open. Is that all?

She said it was a bad time. She would rather I not come inside the house. Boxes were everywhere. Everything was in the boxes. She said that her brother had died on New Year’s Day. More boxes. And that it was fine. She said she really didn’t have anything to offer me. She said she knew nothing about the previous resident Joseph Cornell, other than that he’d existed—and that a different man had lived in the house in between them. That it had been remodeled in the nineties. She had moved there for the street’s flatness—she appreciated flatness in a street. Utopia Parkway.

The artist Joseph Cornell lived a lot of his life at her home at 37-08 Utopia Parkway. Age twenty-six onward. The house is still small and gray. Gambrel roof. Clerestory windows. Sash windows. Tin door. Shingles and clapboard. Familiar, symmetrical face. Like the current resident, Cornell had a brother who died first, who lived there with him, in addition to his mother. Cornell, too, had had boxes everywhere.

I had knocked on a door to no answer and then left a note between the wipers and the windshield of a silver car in the driveway, overlaid on the glass above the inspection/registration and a sticker of Padre Pio—the friar, priest, stigmatist, and mystic. Just after I drove off, it snowed, then it rained, and I assumed the message had run off its page.

I got a call a few days later, around 10 p.m., from a no-caller-ID number. A voice said, Did you leave a thing on my thing? I knew it was her because she spoke like my mother’s family who’d once inhabited that same corridor of Queens.

I told her I was interested in the house itself. I asked if she would mind sending me photographs of the walls; or of the stairs to the basement, where Cornell had collected and organized materials (the clippings, the curios, the dolls); or of the view from the garden, where he took his visitors. Anything, really. She said, Sure. She never did.

***

The house is a Dutch colonial (revival)—fittingly, in Flushing, a part of Queens named after Vlissingen, a city in the southwestern Netherlands, a former island. It is believed that the word Vlissingen is in one way or another related to the word fles, which means “bottle,” fittingly, a recurring object in Cornell’s assemblages. Behind the house, there’s still a one-car garage, where Cornell often sat in a chair on wheels with the door rolled up, an object himself in a shadow box like one of his own—his open-faced homes for flecks of life, little chambers where sense and nonsense make temporary truce.

After I left the note on the windshield, I drove in a confused half snow to New Lake Pavilion for Cantonese dim sum. Waiting for the food, I swiped past little images of Cornell’s shadow boxes on my phone and I thought of the word cathect. I had just learned it the night before, from a poet who’d told an anecdote about her mother, who, while she was in medical school and raising two young children at once, would arrange flowers on Saturdays to calm herself down, to not think—it was a repetition that indexed feeling. She talked about cathecting flowers.

Cathect comes from cathexis: “an investment of energy”—libidinal, of course—“in a person, object, idea or activity.” It’s a word that was created by an analyst who was trying to translate Freud’s gestural use of a common German word: Besetzung—a word with a mutable definition: “(1) the occupation or invasion of a country; (2) the occupation of a building without permission (a squat); (3) casting in a play or a film role.”

I thought of the little eddies of Cornell’s infatuation concretized, translated into the arrangements of ephemera: the keys, the die, the maps, the seashells, the clocks, the birds, the book pages, the dime-store toys. The boxes seem to conjure the sequels to the lives of familiar objects. I swiped through more frames of the boxes as I waited for my check—and I thought, There goes Joseph, cathecting again …

I felt then that somehow each box I swept past was a room in the home on Utopia Parkway. That each box he made was an addition to the house. Expanding each day, a perpetual renovation. That he was his own architect, contractor, decorator, and dweller. Cornell lived with his mother in the house on Utopia Parkway; in his last phone call to his sister on the day he died, he said that he wished he “had not been so reserved.” Part of him wished he had left the house.

***

The current woman of the house didn’t send any photographs. I had no way of calling her back—she’d dialed with a vertical service code. I looked for any photographs of the house’s interior but instead came upon a series of comments spanning four years, left almost fifteen years ago, on a blog post that featured nothing but an image of the home’s facade. The softness of the blue light and the wholeness of the tree behind the house and the certain weather of its green suggested it was taken from a moving car, windows down, by someone passing the home at the end of a near-perfect end-of-summer day, the green so full you know it can’t hold on much longer.

First, a woman had commented on the image, saying she had lived next door to Mr. Cornell as a child, that he had given one of his pieces to her parents as a gift, and that after he died her parents had sold it to John Lennon and Yoko Ono for a thousand dollars. She said that at the time, this had been a lot of money to her parents, who had immigrated to the United States from postwar Germany. That she had just visited the Phoenix Art Museum and saw one of his pieces. “It brought back so many fond memories,” she said.

Then, five months later, in the fall, another woman added that she’d never known Joseph Cornell, but that her family had, and that her mother had often cooked for him and did light housecleaning. Her sisters Fran and Jeanette also did little things around the house for him, and her now-brother-in-law used to make the box frames for his art pieces. She was sorry she’d never met him. “His art was simple in material, but beautiful and complex in meaning,” she said.

In the spring, eight months later, a man added that he grew up about one block down the street. His brother used to help Cornell with yard work, and he was very lucky to have gotten a private showing of his art when he was around twelve, although not as lucky as the first commenter. He said Cornell was something of an éminence grise in the neighborhood. A very good man, but a recluse. No one had had any idea how important he would become.

Six months later, a new woman said to the first commenter that she thought she was her childhood friend who had lived next door. Was your father Gary and your brother Eric? Do you remember me? she asked.

Four years later, almost to the day, in the middle of spring, the first woman had replied. You are correct, she said to the third woman. My father, Gerhard, Gary for short; my mother, Ida; my brother, Eric; and I lived at 37-06 Utopia Parkway. She was trying desperately to put a face to her name. Did she live to the left of them in the beige house? She said that we live in a small world.

An hour later, she asked the third commenter, the man, if he had lived on Crocheron Avenue and Utopia Parkway with his mother and brother in the white apartments. He never responded.

***

After a few months of no word from the current woman in the house, I decided to go by the house again. I was driving from the airport. I looked for the white apartments at the intersection of Crocheron and Utopia, which must be a new color now. I also looked for the quince tree in the yard—there’s a story about Yayoi Kusama and Cornell embracing beneath a quince tree in the little yard behind 37-08 Utopia Parkway. Kusama says that as they kissed, Cornell’s mother threw a bucket of cold water over them, ordering them to stop. That she told him not to touch women. That they were a disease. Kusama said that it was an ideal relationship for her, that he was the romance of her life. That she disliked sex and that he was impotent. That they suited each other well. That he wrote to her many times and called her many times each day. That people would think her telephone was broken, and that she would say, No, no, it’s only Joseph Cornell calling me so often—but given the tree’s barrenness (it was late winter), I was unable to identify whether it was the quince tree at all.

I knocked. After a handful of seconds, a very small woman in a very long robe opened the wood door, and then the second tin door very slowly. She was wearing very furry slippers, red—and behind her there were no lights on at all. I told her who I was. The sun had barely set but she had the look of an animal just after waking. She said, Oh yeah. She spoke very slowly and quietly and her voice had no ring inside it—her words were almost toneless. She said that she’d send pictures to my email address. I handed her a box of sfogliatella, the pastry that looks like a lobster tail, filled with almond paste and candied peel of citron.

Driving down Utopia Parkway, I found myself guilty of cathecting. I found myself casting this woman with the toneless voice, in red slippers and a robe, in the role of Cornell’s mother, maybe, or of Cornell himself. I thought about the house with the woman inside and then about the invasion of a country, or squatting in a building without permission.

The interaction reminded me, later, of something I had not thought about for a long time. When I was seven, we moved into an apartment where the previous tenant had been an only child like me, exactly my age, and who, like Cornell’s brother, had had cerebral palsy. He was blind. There was braille on most of the door frames. At night, when I would get up to pee before bed, I would walk to the bathroom through the dark apartment with my eyes shut, and pass my right hand over the door frames and pretend that I was the boy who’d lived there before.

A few days after, the woman on Utopia Parkway sends me these four photographs and says that she hopes these will suffice, that she is sorry but the house is in disarray, that she is just trying to clean up, to just make repairs, to just get over death.

Eliza Barry Callahan is a writer and filmmaker from New York, NY. Her first novel, The Hearing Test, was published by Catapult. She teaches at Columbia University and is a New York Foundation of the Arts Fellow.

June 25, 2024

On Wonder

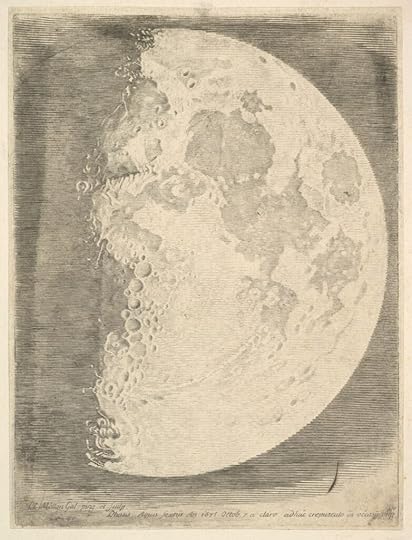

Claude Mellan (French, Abbeville 1598–1688 Paris), The Moon in Its First Quarter, 1635. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. From the Elisha Whittelsey Collection, courtesy of the the Elisha Whittelsey Fund.

I. The World Worlds

It’s probably not the most promising beginning to this talk for me to observe that my subject, like silence, has a way of disappearing the moment you speak of it. Love, anger, regret, even boredom—wonder’s antipodes—may entrench themselves in us more deeply over time, but wonder, I’d venture, is always already a fugitive affair. Maybe it’s a matter of developmental psychology; in the middle of life, I find myself becoming a nostalgist of childhood wonder. (These days I feel it mostly in my dreams.) Or maybe it’s civilization itself that’s outgrown its wonder years. We start out with the marvels of the ancient world—the Great Pyramid of Giza, the Hanging Gardens of Babylon, the Colossus of Rhodes—only to arrive, in our disenchanted era, at Wonder Bread. Any way you slice it, wonder is ever vanishing. Still, I suspect the occasional sighting of this endangered affect has something to do with why someone like me continues to write poems in the twilight of the Anthropocene. Of course, William Wordsworth said all this more eloquently and in pentameter verse, too. Maybe poetry is a faint trace of wonder in linguistic form. By following that trace for the next hour or so, I hope we’ll come a bit closer to wonder itself.

Let’s begin with an early wonder of the Western literary tradition. In Book 18 of the Iliad, the god Hephaestus forges a shield for Achilles, who’s lost his armor in the bloody fog of war. But as Hephaestus works the shield’s surface, this peculiar blacksmith—being a god, after all—simply can’t resist creating a world, too:

There he made the earth and there the sky and the sea

and the inexhaustible blazing sun and the moon rounding full

and there the constellations, all that crown the heavens

A little creation myth blossoms amid the slaughter, as Hephaestus hammers not only Earth but—within the brief passage of three dactylic hexameters—the totality of the known cosmos onto the shield as well. And he’s only just getting warmed up, really. Over the next 150 lines of the poem, Hephaestus emblazons the shield’s surface with a compact survey of ancient civilization, including the arts of war, law, agriculture, animal husbandry, astronomy, music, dance, and so on. A sensualist at heart, he sets this panorama buzzing all over with Epicurean minutiae: we see “bunches of lustrous grapes in gold, ripening deep purple”; we hear a boy plucking his lyre, “so clear it could break the heart with longing”; we even taste the savor of “a cup of honeyed, mellow wine.” Not bad for a piece of antiquated military equipment. Faced with such artistry, I can’t help thinking of the shield’s disabled maker as a kind of poet, like the blind Homer himself. Sure enough, Hephaestus incorporates a miniature epic into the shield’s pageantry, too, with its own besieged city, fraught war councils, interfering gods, and loved ones watching anxiously from the ramparts as a tiny surrogate Hector is hauled “through the slaughter by the heels.” No wonder Homer describes the shield as “a world of gorgeous immortal work.” It contains an entire Iliad and more within its gilt compass.

Beguiled by Homer’s art, some readers have even tried to reverse engineer real shields from this literary blueprint over the millennia. Probably the most spectacular example of all time was fabricated for display at George IV’s coronation banquet by the sculptor, draftsman, and Homer enthusiast John Flaxman in 1821. It’s a marvel of nineteenth-century British punctiliousness in low relief.

The Shield of Achilles designed by John Flaxman and cast by Rundell & Bridge.

Here we find bunches of lustrous grapes in gold, a boy with his lyre, and that cup of honeyed wine—all meticulously accounted for. And yet I can’t help feeling this luminous artifact offers, at best, only a low-resolution copy of the Homeric original. Let’s zoom in for a moment on those golden hounds at their masters’ feet to have a closer look.

I’m not sure why Homer enumerates the figures in this little tableau with such exactitude amid all the shield’s armies, crowds, and processions—“and the golden drovers kept the herd in line, / four in all, with nine dogs at their heels”—but it offers us a perfect opportunity to check Flaxman’s work for quality control. Four drovers? Check. Now let’s count the dogs. (You might think I’m being persnickety here, and with good reason, but bear with me just a little longer.) So where is that ninth hound? Marianne Moore once famously claimed that “omissions are not accidents.” It’s hard to say whether Flaxman’s missing hound is an omission or an accident, but it makes me wonder.

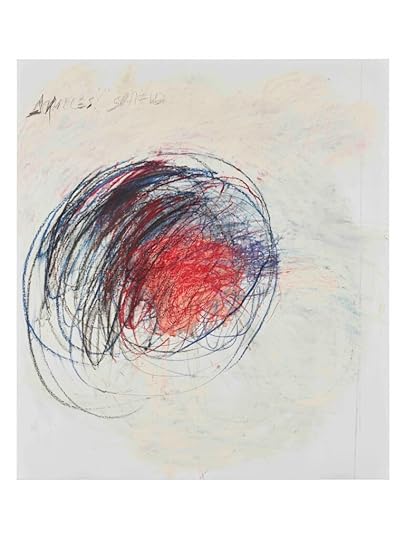

Listen carefully, and you’ll hear the poor beast—“barking, cringing away”—somewhere in the vaporous limbo between fiction and reality. “Paws flickering,” it’s a creaturely cipher for what’s lost when we translate the virtual into the real. The former U.S. Army cryptographer and Homer enthusiast Cy Twombly illustrates this loss in oil, crayon, and graphite in his postmodern Shield of Achilles a century and a half later.

Shield of Achilles by Cy Twombly, courtesy of the Philadelphia Museum of Art: Gift (by exchange) of Samuel S. White 3rd and Vera White, 1989, 1989–90–1. Courtesy of the Cy Twombly Foundation.

You won’t find our missing hound here, either—and that’s the whole point of Twombly’s abstraction. All those kinetic scribbles convey Homer’s energeia, or literary energy, but they also make an absolute hash of the shield’s pictorial imagery. Not even a cryptographer can code so much world into so small a space. Whether you reconstruct it like Flaxman or deconstruct it like Twombly, the shield of Achilles will forever remain an impossible object. It belongs to that wondrous category of things that are larger inside than outside, like a poem, or a person, or a world. “The world is not the mere collection of the countable or uncountable, familiar and unfamiliar things that are at hand,” writes Martin Heidegger in The Origin of the Work of Art, “but neither is it a merely imagined framework added by our representation to the sum of such given things. The world worlds.” Homer’s shield isn’t a picture of all the countable or uncountable things—star systems, ripening grape clusters, flickering hounds—that populate the world. As Flaxman and Twombly discovered, it can’t even be pictured at all. But it worlds.

“Glorious armor shall be his, armor / that any man in the world of men will marvel at / through all the years to come,” Hephaestus predicts as he hammers the glowing cosmos on his forge. If you were to survey the readers’ responses to this literary marvel over the millennia—from the anonymous commentators of antiquity to moderns like Alexander Pope and G. E. Lessing to undergraduate term papers in Humanities 101—you’d end up with something like a brief history of wonder in Western civilization. Describing the plowmen at work on the shield’s figured surface, Homer himself is the first among mortals to express wonder at its construction:

And the earth churned black behind them, like earth churning,

solid gold as it was—that was the wonder of Hephaestus’ work.

I can’t imagine a more gorgeous description of humanity’s passage through the dark field of world: “the earth churned black behind them, like earth churning.” But why doesn’t Homer say the shield’s golden surface churned like earth churning? This Möbius strip of a simile is a marvel in its own right. Spellbound by Hephaestus’s artistry, we forget the shield’s a shield in the first place—so we feel we’re watching soil behave “like” itself. It’s a kind of reverse alchemy, where gold becomes dirt, vehicle becomes tenor, and shield becomes world. Sometimes it seems there’s no escaping wonder before such worlding work. Of the golden women depicted in the shield’s wedding procession, Homer writes, “Each stood moved with wonder.” I’m not sure whether we should envy or pity these embossed figures, forever frozen in transport at the wonder they inhabit.

But there’s a serious glitch in the god’s plans for this “world of gorgeous immortal work.” Though Hephaestus prophesies that “any man in the world of men will marvel” at his craft, none of the many men in the Iliad—Trojan or Greek—ever marvel at the shield’s construction. Achilles’s fellow soldiers won’t even look at the god’s radiant work: “none dared / to look straight at the glare, each fighter shrank away.” Only a blind genius could invent such tragic optics. Homer embeds a gilded cosmos in the midst of the epic for his readers to marvel at through the ages, but the Iliad’s inhabitants remain forever blind to this wonder hidden in plain view. Beholding his gift from the gods, even Achilles—the only mortal who scrutinizes the shield’s figured surface—fails to wonder at the sight:

The more he gazed, the deeper his anger went,

his eyes flashing under his eyelids, fierce as fire—

exulting, holding the god’s shining gifts in his hands.

Rage (mēnis) is the first word of the Iliad, and we usually associate it with blindness rather than perception: “I was blinded, lost in my inhuman rage,” says Agamemnon during one of his many changes of heart in the poem. But Homer envisions something like a phenomenology of rage in this scene: “The more he gazed, the deeper his anger went.” For Achilles, anger is more than affect—it’s an adjunct of perception itself. Only once he’s “thrilled his heart with looking hard / at the armor’s well-wrought beauty” does he break off his furious gaze. Instead of blinding him, rage furnishes this exceptional character with a singular perspective on things.

Why does Achilles alone rage at this “world of gorgeous immortal work”? It may have something to do with his sense of vocation. In Book 9 of the Iliad, we find him in his tent, “plucking strong and clear on the fine lyre” he won in battle long ago, “singing the famous deeds of fighting heroes.” I can’t help feeling this armchair bard would have made a passable poet in a different world. (Isn’t every poet a sulky egotist with a hyperactive death drive, after all?) But Achilles is born to fight, not to sing. Anything that comes between him and his bloody vocation—including the “beautifully carved” lyre, “its silver bridge set firm”—must be cast aside for him to follow this calling. Not even life itself matters more to him than this grim occupation. “Hard on the heels of Hector’s death your death / must come at once,” his mother warns him, but Achilles only retorts, “Then let me die at once.” What’s the point of living if you can no longer kill? Achilles doesn’t work to live, he lives to work—Homer uses the word ergon, which means something like “labor,” to describe the hero’s exertions on the battlefield—and his business is death.

Wonder, for the Greeks, led to a very different sort of vocation. We see this illustrated in a scene from Plato’s Theaetetus, where Socrates plays his customary role of career counselor to a youth he’s interrogated to the point of utter perplexity:

Theaetetus: By the gods, Socrates, I am lost in wonder when I think of all these things, and sometimes when I regard them it really makes my head swim.

Socrates: It seems that Theodorus was not far from the truth when he guessed what kind of person you are. For this is an experience which is characteristic of a philosopher, this wondering [thaumazein]: this is where philosophy begins and nowhere else.

Funny how Theaetetus must first become “lost in wonder” in order to find himself. He learns “what kind of person” he is—a philosopher—from his brush with thaumazein. This beats any aptitude test I took in high school. For Plato, wonder “is where philosophy begins and nowhere else.” No wonder, no philosophers. Even Aristotle, who built a whole philosophical system from his lover’s quarrel with Plato, agrees on this point. “It is through wonder that men now begin and originally began to philosophize,” he observes in the Metaphysics, “wondering in the first place at obvious perplexities, and then by gradual progression raising questions about the greater matters too, e.g. about the changes of the moon and of the sun, about the stars and about the origin of the universe.” If this sounds familiar, it’s because we’ve come full circle, to the origin of the cosmos—the earth, the stars, “the inexhaustible blazing sun and the moon rounding full”—that Hephaestus hammered onto the shield’s bright circumference in the first place. But we’ve yet to consider those “greater matters” that form the astronomical rungs on the ladder of Aristotle’s ascent into thaumazein—the moon, the sun, the stars, and the origin of the universe. Let’s take the next step in wonder’s philosophical progression and look to the moon.

II. Worlds Beyond

Sooner or later, the moon pops up on pretty much every poet’s literary horizon. Whether you’re a Japanese courtesan, a Yoruban folk singer, or a Conceptualist cosmonaut, it’s as close as the art comes to a timeless universal motif. But how many poets ever make the moon feel new in their art? Nearly 350 years ago, John Milton managed to work a nifty little lunar renovation into the epic paraphernalia of Paradise Lost, as the irrepressible Satan—after nine days and nights in free fall from the battlefield of heaven—takes up arms once again:

His ponderous shield,

Ethereal temper, massy, large and round,

Behind him cast. The broad circumference

Hung on his shoulders like the moon whose orb

Through optic glass the Tuscan artist views

At evening from the top of Fesolè,

Or in Valdarno to descry new lands,

Rivers or mountains in her spotty globe.

Even the most pious poet can’t resist a bit of literary vandalism now and then. Emblazoning the full moon on Satan’s shield, Milton blots out the classical world of Achilles’s shield—just as Paradise Lost will, he hopes, eclipse the Iliad in the annals of literary history someday. “Massy” yet also “ethereal [in] temper,” Satan’s shield is another kind of impossible object, or hyperobject. It belongs to that wondrous category of things that hold dual citizenship in the realms of the material and the ideal, like a poem, or an angel, or the venerable moon itself. Since antiquity, astronomers had speculated about the moon’s ontology—was it composed of ethereal vapors, or massy like the earth?—until Milton’s “Tuscan artist” put these theories to the proof with the aid of his “optic glass.” Oddly, we don’t really see much of the moon on Satan’s shield. Superimposed on its “spotty globe,” we find a portrait of Galileo Galilei—the man in Milton’s moon—who, more than any poet or rebel angel, revolutionized our view of the heavens above.

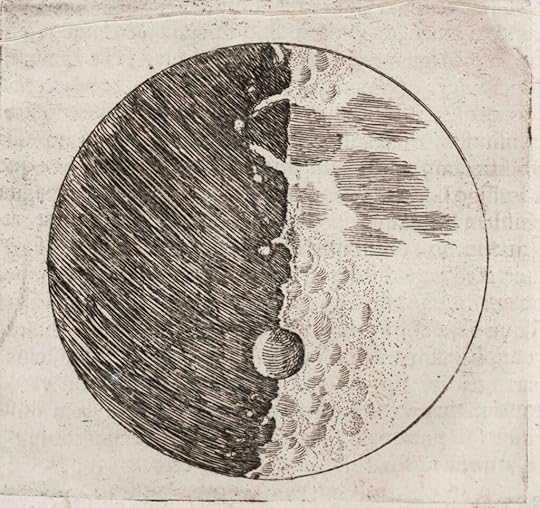

Milton visited Galileo—by then old, blind, and under house arrest—in Florence during the summer of 1638. (DreamWorks has been sitting on my script of this story for ages.) In his book The Starry Messenger, Galileo had published the first topographical drawings of the moon’s surface to appear in the West nearly three decades earlier.

Galileo’s moon sketch. Courtesy of Linda Hall Library of Science, Engineering & Technology.

Peering through his telescope, the Florentine astronomer marveled at a cratered and mountainous terrain that defied expectation:

The surface of the Moon is not even, smooth and perfectly spherical, as the majority of philosophers have conjectured that it and the other celestial bodies are but, on the contrary, rough and uneven, and covered with cavities and protuberances just like the face of the Earth, which is rendered diverse by lofty mountains and deep valleys.

Galileo discovered that the moon, too, was a world, “just like” ours. Look closely at that progression of topological nouns ending Milton’s lines, and you’ll see how the moon came of age as a world in this period—from a flat “circumference” to a volumetric “orb” to a mapmaker’s “globe.” In Galileo’s wake, the French engraver Claude Mellan’s moon maps would soon highlight the chiaroscuro curvature of the lunar orb.

Three representations of the moon by Claude Mellan, courtesy of The Elisha Whittelsey Collection, The Elisha Whittelsey Fund, 1960.

By the end of the eighteenth century, the moon had assumed world-like dimensions in the British artist John Russell’s aureate globe.

Moon globe by John Russell.

All this time, Earth was yielding its last blank spots—known as sleeping beauties—to the epistemological imperium of geography. But now another “spotty globe” offered “new lands, / Rivers or mountains” to be mapped—and the moon was only the beginning.

The moon on Satan’s shield heralds a revolution in the history of cosmological wonder. Galileo’s telescope revealed a host of worlds in the heavens above—new moons circling Jupiter, stars never before seen by the human eye—all swiftly incorporated into blind Milton’s literary vision of the cosmos. Paradise Lost stages a universal masque of wonder beneath this canopy of plural worlds. Awestruck, Adam delivers a Hamletic soliloquy on outer space, which makes of “this earth a spot, a grain, / An atom with the firmament compared / And all her numbered stars that seem to roll / Spaces incomprehensible.” Milton himself wonders if God might “ordain / His dark materials to create more worlds” from chaos someday. Satan, too, plays the amateur cosmologist, speculating that “space may produce new worlds” for his legions to invade following their expulsion from the kingdom of heaven. If you find Paradise Lost slow going, try reading it as science fiction. (Spielberg, what are you waiting for?) Nebulous monsters wing their way through star systems. Angels and demons alike imagine humans colonizing other planets. For the first time in English poetry, we view Earth from outer space—“that globe whose hither side / With light from hence though but reflected shines”—half cloaked in brightness, half in shadow. I could go on. But amid all this, the archangel Raphael warns Adam—and, consequently, Star Trek aficionados everywhere—to “dream not of other worlds, what creatures there / Live in what state, condition or degree.” Maybe wonder, like the moon, has a dark side.

Let’s not forget that the most wonderstruck character in Paradise Lost also happens to be the most fiendish by far. Unlike furious Achilles, Satan simply can’t stop mooning over all of creation. From the stairway to heaven, he “looks down with wonder” at Earth below; once he’s touched down on our planet, he gazes upon Eden “with new wonder”; when he first sees Adam and Eve, he’s overcome by “wonder and could love” them, too. Such vulnerability to wonder, on Satan’s part, is frankly endearing. I, for one, can’t help feeling sympathy for the poor devil when we last see him—at the conclusion of his final speech to the rebel angels in hell—still wondering to the bitter end:

He stood expecting

Their universal shout and high applause

To fill his ear when cóntrary he hears

On all sides from innumerable tongues

A dismal universal hiss, the sound

Of public scorn. He wondered but not long

Had leisure, wond’ring at himself now more:

His visage drawn he felt to sharp and spare,

His arms clung to his ribs, his legs entwining

Each other till supplanted down he fell

A monstrous serpent on his belly prone

I’ve felt this way after poetry readings myself sometimes. (Isn’t every poet a narcissistic angel in reptilian form, after all?) Satan’s ultimate object of wonder in Paradise Lost isn’t a newly discovered planet, or humankind, but “himself,” transformed into a serpent. You’d expect Satan to feel horror at this grotesque Ovidian metamorphosis—his cranium warping hideously, his arms fusing into his torso, his legs corkscrewing into a scaly tail—but this antihero’s wondrous journey through the cosmos ends where it began, in a failure to see himself for what he really is. Maybe dreaming too much of worlds beyond reach can make a monster of you.

Worlds swim through Paradise Lost like bubbles in a glass of champagne, but Milton cautions us not to lose sight of ourselves in this teeming universe. Who’s more blind to our world than the astronomer squinting into his telescope’s eyepiece? “They can foresee a future eclipse of the sun,” writes Augustine in his Confessions, “but [they] do not perceive their own eclipse in the present.” I suspect Milton had this sort of inner eclipse in mind when he described Satan’s dusky radiance following the archangel’s fall from heaven:

His form had not yet lost

All her original brightness nor appeared

Less than archangel ruined and th’ excess

Of glory obscured, as when the sun, new ris’n,

Looks through the horizontal misty air

Shorn of his beams or from behind the moon

In dim eclipse disastrous twilight sheds

On half the nations and with fear of change

Perplexes monarchs. Darkened so, yet shone

Above them all th’ archangel

Milton’s selenographic shield may advertise Galileo’s discoveries, but its spotty globe also reminds us that Lucifer—the erstwhile “bringer of light”—is, in truth, eclipse personified: “Darkened so, yet shone / Above them all th’ archangel.” Nothing discloses the dark side of wonder like an eclipse. I once saw one, through a piece of welder’s glass, in a derelict park on the other side of the world. Even the crows seemed perplexed by its disastrous twilight. There was an uncanny chill, as if a refrigerator door had swung open inside me. But the wonder of it all wasn’t that the sun had been blotted out overhead. What stopped my breath was the slow silhouette of another world gliding into view.

III. Worlds Within

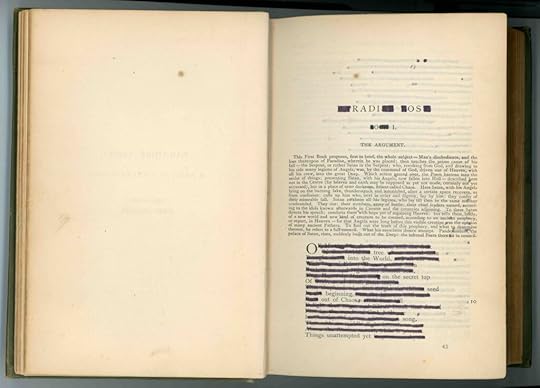

Three centuries after Paradise Lost first lit up the Western literary firmament, an American poet, cookbook author, and marijuana enthusiast named Ronald Johnson purchased an 1892 edition of Milton’s poem in a Seattle bookshop—and promptly began to black out most of the text from its pages.

Image courtesy of the Ronald Johnson Collection, Kenneth Spencer Research Library, University of Kansas. Used with permission of the Literary Estate of Ronald Johnson.

Why would anyone so meticulously deface an already outdated copy of the venerable Puritan epic? “I got about halfway through it, kind of as a joke,” Johnson later explained in an interview, like a sheepish delinquent caught spray-painting a cathedral. “But I decided you don’t tamper with Milton to be funny. You have to be serious.” What began as a little joke at Milton’s expense developed into a postmodernist masterpiece of literary eclipse in its own right. Blot out the first and last two letters of paradise, and you have radi. Lose the first and last letters of lost, and you have os. Even the title of the poem Johnson fashioned from this procedure—Radi Os—is ordained solely from Milton’s dark materials.

Before publishing this literary curio, Johnson scrupulously whitewashed the epic he’d defaced, yielding a photographic negative of his poetic eclipse:

Image courtesy of the Ronald Johnson Collection, Kenneth Spencer Research Library, University of Kansas. Used with permission of the Literary Estate of Ronald Johnson.

Nobody wrote Radi Os. The poem was wondrously erased into existence. Its author’s words are nowhere to be found in this work, and yet—like Milton’s Creator—he’s everywhere.

“There is another world,” the French poet Paul Éluard once said, “but it is inside this one.” I think Johnson would gently amend this to say there are other worlds, but they are inside this one. Turning the astronomical theater of Paradise Lost inside out, Johnson investigates the plurality of worlds within: “worlds, / That both in him and all things, / drive / deepest.” A little textual puzzle from ARK, the cosmological epic Johnson labored over for twenty years, illustrates the wondrous multiplication of inner worlds throughout this poet’s work:

earthearthearth

earthearthearth

earthearthearth

The literary critic Stephanie Burt has deciphered the secret messages embedded in this triple-decker concrete poem. Earth, earth, earth. Ear, the art hearth. Hear the art, hear the art. Sampling a jeremiad from the King James Bible—“O earth, earth, earth, hear the word of the Lord”—Johnson composes a manifold matrix of worlds (and hearts). It’s one thing to register the verse in universe and another entirely to construct a poetics of the multiverse. The erasurist’s decision not to delete the s that pluralizes his book’s title makes worlds of this difference. Radi Os isn’t a radio; it’s an orchestra of radios. Well, that’s not quite right. See that caesura fracturing the poem’s title? An imaginary number of broken “radi os” hums and buzzes inside this literary hyperobject. One radio may tune into a single frequency at a time, but a chorus of broken radios can broadcast everything from an infernal racket to the music of the spheres all at once. “You don’t tamper with Milton to be funny,” our holy fool may attest, but for all its radical theology, Radi Os is, in the end, a divine musical comedy.

Listen carefully, and you’ll hear a marvelously cracked piece of postmodern music playing behind the curtain of Johnson’s literary erasure. At a party with his students one night—so the story goes—the poet first heard a recording of Baroque Variations, by the composer Lukas Foss. At one point in the work, a xylophone spells out Johann Sebastian Bach in Morse code. Elsewhere, a highly trained musician smashes a bottle with a hammer. Johnson’s various enthusiasms must have lined up nicely that evening, because he embarked upon the “solitary quest in the cloud chamber” that would become Radi Os the very next day. In the dedicatory note to his book, Johnson quotes Foss’s liner notes for Variation I—on a larghetto by Handel—as a sort of key to his own work:

Groups of instruments play the Larghetto but keep submerging into inaudibility (rather than pausing). Handel’s notes are always present but often inaudible. The inaudible moments leave holes in Handel’s music (I composed the holes). The perforated Handel is played by different groups of the orchestra in three different keys at one point, in four different speeds at another.

Handel’s larghetto, from the Concerto Grosso, op. 6, no. 12, may very well be the most beautiful melody the composer ever wrote. It’s easy enough to find online, if you’d like to hear the “always present but often inaudible” original music behind Foss’s détourned Variation I sometime. Then listen to the Foss, and you’ll experience the otherworldly beauty of Handel under eclipse. It’s hard not to hear broken radios searching for a classical music broadcast in this perforated larghetto’s eerie harmonics and bursts of sonority. If you find Radi Os slow going, try reading it as the libretto for a post-structuralist space opera—lyrics erased by Johnson, score perforated by Foss.

The wonder of variations—in music, in poetry, in evolutionary biology, and elsewhere—is how one variation begets another, though you never know what you’ll beget. Perforating Paradise Lost, Johnson produced a literary variation on Foss’s musical variation on a Baroque artist who composed dozens of variations of his own—including Hephaestus’s favorite, “The Harmonious Blacksmith.” To see how Radi Os makes possible even further variations on itself, let’s look at the original passage in the 1892 edition of Paradise Lost on the page where Satan’s shield first appears.

Image courtesy of the Ronald Johnson Collection, Kenneth Spencer Research Library, University of Kansas. Used with permission of the Literary Estate of Ronald Johnson.

What if somebody other than Johnson—say, a young woman in rural New England on a snowy night long ago—were to compose her own holes in this dark material?

time

Can

thunder

Here

Here in my

unhappy mansion

but

that voice

Of

fire

scarce ceased

the

Ethereal

artist

in her globe

Of

marle steps

On and

on

It’s hardly “Because I could not stop for Death,” but you get the idea. There are innumerable poems encrypted in the “harmonious numbers” of Paradise Lost. I even hear echoes of the sadly underrated poet, Star Trek aficionado, and Ronald Johnson enthusiast Srikanth Reddy in this literary cloud chamber.

The mind is

a

matter

my

friends

of

voice

the edge

Of it

moving

like

glass

in

Rivers

but

burning

I could do this forever, and that’s exactly the point. You could, too. I suspect that’s why Johnson breaks off his own work at Book 4 of Paradise Lost, leaving nearly seven thousand lines of pristine Miltonic pentameters for others to cross out someday. “Radi Os kind of wrote itself,” said the author of this unfinished erasure. “I think it ended when it needed to end, and I didn’t need to add the rest.” An open-ended variation on Milton’s song, Radi Os invites us to “add the rest.” And why stop at Paradise Lost, for that matter? Compose your own holes in any book—Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, the Constitution of the United States of America, The Unsignificant—and you’ll unearth a manifold matrix of worlds within.

A literary multiverse, Radi Os is riddled with cosmological wormholes, theological rabbit holes, and typographical holes. From the “O tree,” a slant rhyme for poetry that opens the work, to the “O for / The Apocalypse” that trumpets the poem’s closing revelations, Johnson makes us see the hole in whole and hear the hole in holy. There’s a hole in wonder, too, though I’d never tumbled through it until I came across the following page in Radi Os:

Image courtesy of the Ronald Johnson Collection, Kenneth Spencer Research Library, University of Kansas. Used with permission of the Literary Estate of Ronald Johnson.

The first time I read this passage, I had no idea what lay behind it. But that floating little phrase—“the O / Of / wonder”—kept looping around in my head, so I dug up an old copy of Paradise Lost to read the Miltonic original and was wonderstruck. Almost three thousand years ago, a blind Greek poet pictured the world on an ancient shield. Two and a half millennia later, the moon spied through an optic glass eclipsed Homer’s world in a theological poem of Reformation England. In my own lifetime—I was four, astronauts had set foot on the moon’s surface only a few years earlier—a little-known American poet erased Milton’s spotty globe all the way down to a wondrous O. World, moon, O. The word for when things line up in this way is syzygy. The microscopic linkage of chromosomes necessary for reproduction in our species is one example. An eclipse—when three celestial bodies line up in astronomical space—is another. The word syzygy is itself a syzygy, which almost makes me believe in intelligent design as far as language is concerned. Read aloud its sequence of three identical vowels lined up in a row—y, y, y—and you’ll hear humankind grappling with the mystery of causation. Let’s not overlook that linked chain of o’s in “the O / Of / wonder,” either. It’s a syzygy, too. Why, why, why? Oh, oh, oh. We all live that song.

So many images flicker through this O in Radi Os—a full moon, a ghostly shield, a hole in a page from a timeworn edition of Paradise Lost—but I always return to a mouth open in wonder. When we see golden acrobats turning handsprings on an ancient shield, or when the mountains of the moon first swim into focus through a telescope’s eyepiece, we say “O,” hardly aware that our lips are assuming the shape of the signifier itself. The “O” of wonder, Johnson shows us, is the o in wonder. I can’t think of any other word where our writing system and the morphology of human speech enter into such wondrous alignment. But the mouth forms an O in arousal, and in hunger, and in death’s terminal rictus, too: “Thy mouth was open,” George Herbert says to Death personified, “but thou couldst not sing.” There’s no such thing as pure or simple wonder. When thaumazein forces our lips into an O, all those ancient drives—from Eros to Thanatos—move through us as well. The art of poetry traditionally originates in this inexhaustible, sonorous “O.” O muse, O Lord, O my love, O late capitalism, O etcetera—the O that Johnson plucks out of wonder invokes endless poetic variation. With all due respect to Plato and Aristotle, philosophy isn’t the only vocation that springs from thaumazein. If you look closely at the O of wonder, you’ll see a poem beginning there, too.

Srikanth Reddy is the poetry editor of The Paris Review. This lecture will appear in The Unsignificant: Three Talks on Poetry and Pictures, forthcoming from Wave Books in September.

June 24, 2024

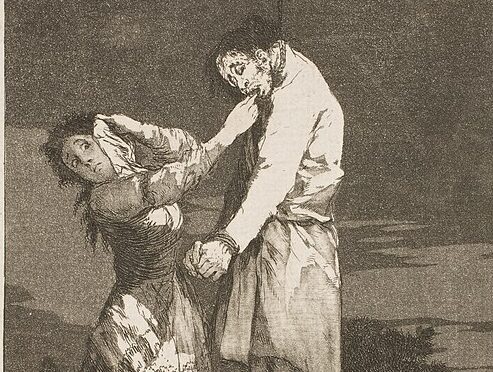

Swallowing: I Was Mike Mew’s Patient

Francisco de Goya, “Out Hunting for Teeth,” 1799. Public domain. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

I named her Holy Jemima when I was nine, or thereabouts. I liked the way the words sounded and it was meant cruelly. Holy Jemima was two years older than me, and her family—her mother, father, two sisters, and brother, making six—were in a cult.