The Paris Review's Blog, page 26

July 22, 2024

Anthe: On Translating Kannada

Drawing by Deepa Bhasthi.

Anthe (ಅಂತೆ) is one of my favorite words in the Kannada language. Somewhat meaningless by itself, it adds so much nuance and emotion when appended to a sentence that we Kannadigas cannot carry on a conversation without using it. Depending on the context and the speaker’s tone, anthe can convey an expression of surprise or the understanding that gossip is being shared. It could mean “so it happened,” “that’s how it is,” “apparently,” or “it seems.” The latter comes closest to a direct translation, but is a frustratingly simple choice. Anthe will only ever half-heartedly migrate to English.

Banu Mushtaq, whose short stories I have been translating recently, and whose “Red Lungi” appears in the Summer 2024 issue of The Paris Review, employs anthe generously. Mushtaq’s characters use anthe when reporting something someone said verbatim or when guessing how something might have happened. In another instance, she uses echo words with anthe, another common characteristic of the Kannada language: one character utters anthe-kanthe to refer to hearsay. There are also a whole lot of ellipses in Mushtaq’s stories … her sentences often trail off … like so … She mixes up her tenses here and there. It is always deliberate, this nod to the idea that time is not linear. The awareness that we inhabit different time zones and dimensions and live in stories within stories is commonplace in India. These narrative tools give Mushtaq’s work a sense of orality, as if she is sitting across from you and telling you the story.

Whenever Mushtaq and I do talk in real life, she is narrating, she is reporting, she is discussing the oppressive political scene in India, she is going back to her youth, laughing about that one time there was a fatwa issued against her for a story—they wanted her to stop writing, she told them to go to hell—she is constantly relaying anecdotes and thinking out loud and living through stories. There is more anthe in her urgency to convey everything all at once than I can hope to store in my notes.

My favorite function of the word is how its repetition in every other sentence, each differently intoned, allows a musicality to slip into daily speech. It gives everyday Kannada its impu, or melody.

Kannada belongs to the Dravidian family of languages native to southern India, and it is spoken by an estimated fifty to sixty million people around the world. It is the official language of the state of Karnataka. Kannada literature has been published continuously, without any lapse, for fifteen hundred years. Poets have described Sirigannadam, or “rich-Kannada,” as a river of honey, as milk rain, as being as sweet as nectar, as truth, as an eternal language. As old and celebrated as it is, Kannada is just one of India’s hundreds of languages (estimates vary between 780 and 1,600, in addition to thousands of dialects). An aphorism in the Khari Boli language best expresses the country’s mind-boggling linguistic diversity: Kos-kos par badle paani, chaar kos par baani, meaning that the water in India changes every two miles, and language every eight miles.

Mushtaq’s mother tongue is not Kannada, and strictly speaking, neither is it mine. Hers is Dakhni, a fascinating mix of Persian, Dehlavi, Marathi, Kannada, and Telugu that is often wrongly called a dialect of Urdu. It is spoken in parts of southern India predominantly, though not exclusively, by the Muslim community. My mother tongue is Havyaka, a dialect that harks back to Old Kannada (a parental language that dominated from the ninth to the eleventh century C.E.) and is spoken by a small community of upper-caste brahmins along the Arabian coast as well as by a similar community in central Karnataka. (The two versions differ and are mutually unintelligible.) However, for various sociogeographical reasons, what I grew up with was a mix of Kannada varieties common to the Mysore region and coastal Mangalore. Both Mushtaq and I live in small towns where we regularly speak at least three or four languages and a number of dialects. This use of numerous sociolinguistic systems is, for a very large number of Indians, par for the course, and is certainly not just a function of class, caste, education, or intellectual leanings. I know a grocer in my town who speaks thirteen languages fluently.

Mushtaq’s decision to write in Kannada is hardly unusual today. The second half of the twentieth century saw many eminent multilingual writers choose to work in Kannada, the dominant language spoken on the streets, even though their mother tongues were Konkani, Telugu, Tamil, Tulu, or others, and they conducted their professional lives in English. Such multilingual proficiency is much rarer now—thanks to the colonial-era Macaulayism that continues to drive India’s English-forward education system, most of us might speak many languages but be proficient only in English.

Banu Mushtaq sprinkles her Kannada with Dakhni, Urdu, and scant Arabic. Each of these languages is also further influenced by local distinctions specific to Bayalu Seeme, a region of Karnataka characterized by open plains, where she lives. What enriches my translations, I like to believe, is a complete immersion in the culture of the text I am working with. I had an easier time translating my first two books, as they were in languages and from regions I was very familiar with. Mushtaq’s stories are set within India’s Muslim community, though her work is not from and for Islamic culture alone. Still, her references are a world apart from my own lived experiences. In trying to bridge the gap in my understanding, I found myself reaching for culture that shared linguistic, social, and aesthetic influences with the milieu of her stories. Somehow, this kind of immersion seemed to help me be better attuned to the subtleties in her text. I was introduced to the all-consuming world of Pakistani TV dramas, a vast subculture that overflows with intrigue, suspense, romance, and high-octane drama that thrills most desi hearts. I rediscovered Qawwali music, falling irrevocably back in love with Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan, Abida Parveen, Arooj Aftab, Ali Sethi, their ilk. Alongside my everyday dosage of Kannada-ness, I read about Islam. Reopened my Arabic notes from the lessons I once received from a maulvi saheb. Enrolled in a Nastaliq script-writing class in which we studied talaffuz (pronunciation) via Hindi films and poetry. I cannot say where and how this research helped my translation practice. But it has enriched my years like anything, as we say in India.

Any practice of writing and translation in this social terrain can become very political very quickly. The politics of language in India are, as one might expect, a source of severe passion and violence. While attention to the most prominent language in any state—Kannada in Karnataka, for instance—comes at the cost of the prominence, public usage, and funding for the instruction of several others, perhaps the greatest threat to linguistic diversity across India comes from the imposition of Hindi. Spoken mostly in parts of northern India, central government policy has historically forced the language upon other states, where it has often been violently rejected, especially in the southern states. These language wars have killed people, and emotions around imposition of one language at the cost of others, whether Hindi or a regionally dominant language, are always simmering below the surface. Why translate at all, in the face of so many complexities? This is a question we can no longer afford to ask. The Kenyan writer Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o calls translation “the common language of languages.” In India, linguistic hegemony is just one of the many dangers of the homogenizing policies of a far-right-wing-led government since 2014. When engaging with another language culture, one experiences, in learning a new word or phrase, a glimpse of a different world, however ephemeral.

In the hierarchy of who gets to translate, who gets to be translated, who gets funding for new translations … Kannada does not fare too well. Barely a handful of literary translations in the Kannada-English pairing is published in a year. This is miles behind literatures written in, say, Malayalam, Tamil, Bengali, Urdu, or Hindi. To translate at all, and then to translate from an underrepresented language, and finally to translate into English, with all its baggage, is riddled with layers of questions for which there can never be simple answers. I reach back for anthe, trying to see how complexities can often remain unresolved. Anthe refuses to let itself be easily carried out of Kannada, which in turn reminds me that it is okay not to have all the answers about translation and its politics.

One delightful side effect of all the language cultures we live with in India is how often we toggle between two or three languages when conversing. This reduces language to its basic function, as a tool to communicate with whatever words are within reach, stripping the need for “proper” articulation, throwing out all the rules. We alternate this pared-down approach with hyperbole and exaggeration, with repetitions of a word for a sense of emphasis— “I’ve told you a thousand times,” “small-small,” “round-round,” “two-two times …” This interplay of the utilitarian and the embellished, the functional and the ornamental, is also where I find the uniqueness of Kannada when I translate. It is important for me to retain these qualities—for instance anthe rendered as the inadequate “it seems,” which I’m sometimes told is not quite elegant enough English, because carrying these nuances is like speaking English with an accent. It reminds the reader that the text is from another culture. In translation, these expressions stretch the elasticity of the English language. In turn, Kannada gains another reader.

Deepa Bhasthi is a writer and critic who translates Kannada-language literature.

July 19, 2024

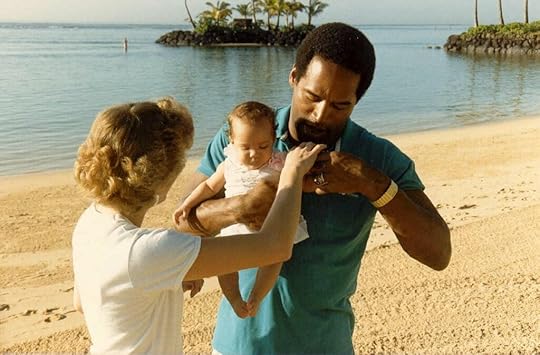

Driving with O. J. Simpson

O. J. Simpson, Nicole Brown Simpson, and Sydney Simpson at the Kahala Hilton Hotel in Honolulu, Hawaii, February 1986. Photograph by Alan Light. Via Wikimedia Commons, licensed under CC0 2.0.

My father and O. J. Simpson were passing ships in red Corvettes in Brentwood, Los Angeles. Circa 1977, the sunroofs of their nearly identical luxury cars open for maximum exposure, they would wave to one another like carnival jesters, my sister in the back seat squeamish at the irony, their white wives occupying the front seats in a Siamese dream, twin stars in the fantasy no one is aware of until it arrives in images. Such gestures were the requisite scenic signifiers for that era of post–New Negro black entertainers faced with the hedonism of psychedelia, blaxploitation, and the amphetamined economy of the Reagan years. They were transitioning from taboos to tabloids to well-adjusted, literal tokens, having made it to some sense of after all or ever after in a fairy tale blurring the wasteland upheld by the lucky-bland amusements of almost-suburbanites. Unkempt and illicit ambitions were their freedom and retribution.

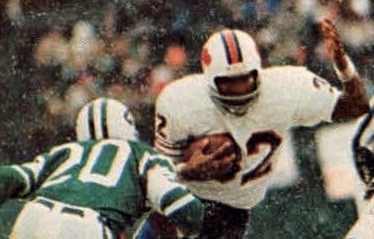

My father earned his living writing love songs that were ventriloquized by pop stars and peers such as Ray Charles; he agonized over the banality of spectacle in lyrics that rendered the banal uplifting. O. J. cradled footballs and ran very fast when chased, bowlegged, baffled at his own momentum. He accrued enough of it to become the first black athlete to garner corporate endorsements from companies like Hertz. He’d open in the typical format of vintage commercials, by reciting semi-didactic pleasantries as adspeak. Then he’d embody his embargoed alter ego, his own personal starship and space shuttle, and ramp up to cinematic sprinting through an airport terminal, wearing a three-piece suit and landing in a hideous car that made the Corvette with the top down seem like an inaccessible yearning, all while maintaining the plastic smile of a catalogue model. O. J.’s sad and vaguely distracted gaze revealed a self-deprecating narcissism contracted during the transition from being bullied as a child to outrunning everyone and every limitation he’d ever known. This was before it was acknowledged that the cerebrum of football players and boxers are often severely damaged and inflamed by the time they retire—and likely throughout their careers—in ways that can trigger bouts of rage, dementia, confusion, memory lapse, erratic dissociation. The talent, the miracle of divine intervention, that grants them access to white America’s lifestyle, in turn holds them hostage in pathologized exceptionalism. This makes it easier to understand the fatigued and dejected glaze over O. J.’s gaze as a mask dressing a festering internal wound.

My father’s gaze was similar, confident but strained and distant, almost plaintive. He’d spent some years as a welterweight boxer, which may or may not have contributed to his struggle with bipolar disorder and the constancy of lithium prescriptions of varying strengths—pharmaceutical cocktails, which, in addition to tempering his mood swings, siphoned the vigor from him, bending his will toward a docility more unnerving than rage. O. J’s double consciousness remained slicker and more protected; he made his icy sublimated anger into his signature charm even as it remained in part involuntary. As I write this, O. J.’s remains are being cremated in Las Vegas, and scientists have requested the opportunity to examine his brain for signs of chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE). The Simpson family is refusing. O. J. himself was convinced that he did suffer a level of chronic swelling consistent with the condition and severe enough to compromise his cognition and memory. There is no logical way to deny his intuition about this, considering the length of his career (he spent eleven years in the NFL and was a collegiate player before that) and the minimal number of blows to the head required to trigger a lifetime of chronic swelling. While considering O. J. and my father as twin victims of their own ambitions, I wonder how many blows to the skull, how many subtle fractures my father endured, and would I want to look inside and see the tissues ballooning for myself, would I allow doctors to dissect his brain for proof or defer to suspicion and leave space for the sacred/sacrosanct black-and-blank mystery of our destiny? I can’t be sure.

O. J. Simpson, then the Buffalo Bills’ running back, rushing the ball against the New York Jets on December 16, 1973, breaking the NFL’s single-season rushing record. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Some retired NFL players with severe cases of CTE become suicidal, go through with it, and shoot themselves in the heart so that their brains remain intact to be studied, blamed, perhaps so their souls are disabused of some turmoil. I imagine my father’s and O. J.’s waving hands in their twin Corvettes as their euphemistic version of throwing up reciprocal gang signs or channeling their shared elegance as ghetto mysticism. If they could get by with disguising themselves as happy-go-lucky all-American Negroes gentrifying Brentwood, they assured one another telepathically, they could exceed that. The excess could be lethal, or it could remain glorious; this was the risk of surpassing the confines of the lot they were handed at birth. Why settle for affability and sports cars, why not blend convention with sin and dysfunction and really have it all? They fade out into sunsets and party din, the lull of elite motors, the scoffing giggle of unimpressed bystanders.

***

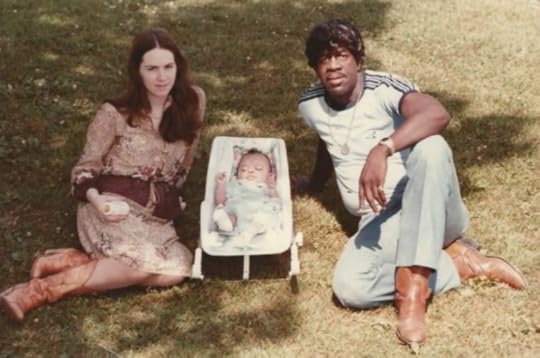

America needs black sociopaths, and breeds them, as much as she needs and breeds white ones and interracial love on her jagged and insincere path to approximating an egalitarian society stabilized by its consistent deference to spectacle. No renegade and formerly-oppressed minority group makes it in the USA without a few representatives or sentinels who are sanctioned to explore deviance with impunity alongside the so-called elite. And some invent an axis where desire, race, and criminality are forced to confront one another and try to survive or outwit the ensuing clash between ego and instinct. My parents met the same way O. J. and Nicole Brown did. My mother was a part-time waitress during college, and one night my dad was a lonely customer at the diner where she worked (as I imagine it, I hear Joni Mitchell crooning, “I am frightened by the devil, drawn to those who ain’t afraid”). They were married not long after that. Nicole Brown was waiting tables at an LA hotspot called The Daisy when O. J. came in one night. They were together from that point on, even though he was still married to his first wife during the early stages of their courtship. Neither woman knew her suitor was any kind of celebrity on first encounter. By all accounts, both couples began happy, and effortlessly transgressive. A young white woman, a much older black man with money and status. Children next. There I was, in the spring of 1982, less than a year after my parents met. Nicole gave birth to Sydney, her first child with O. J. in 1985.

“She doesn’t look like a black baby, O. J.,” Nicole Brown Simpson, captured on a now-retro camcorder, proclaims in the delivery room just after giving birth to their daughter, Sydney, in Los Angeles. Can a black star or his daughter be so lucky or sheltered or race-card-never-played-and-plagiarized as to experience emergence into human consciousness casually, instead of as casualty of close scrutiny for ruins? Unlikely. Nicole isn’t disinheriting her daughter in interrogating her lighter shade of brown; she seems genuinely concerned or perplexed, as if she might have inflicted an ambiguous pallor onto a soul who never asked for the burden of two worlds announcing themselves simultaneously as one skin. O. J. continues filming and celebrating, delighted and unfazed, as though he’d had a premonition about this auspicious event—the all-American and his gorgeous blond wife and nearly passing daughter are his paradise lost and recovered. He beams with the pride of a man reinvigorated by the birth of his child—he’s forty-one, a perfect age for a second wife and a second chance at a picturesque nuclear family. There’s omniscience in the delivery room, haloing it—Exhibit A.

Family photograph, 1983. Courtesy of Harmony Holiday.

By that same year, at the age of four, I was mistaking for adventures our family trips to precincts to have bruises examined by police officers. We didn’t get out much. Unless Dad was manic or hired to make some recordings; then we’d drive from Iowa to LA in two days without stopping. The red Corvette had been lost in the divorce from his first wife, but dad sustained the entitlement and urgency of a man who had once owned everything. He would leave us later that year, like one of those retired players who rips his own heart out after it breaks—a ruptured aneurysm, a burst of red light in the wounded cranium.

My mother and Nicole Brown were born the same year, 1959, the year Billie Holiday died, the year the spirit of integration Billie introduced by singing “Strange Fruit” at Café Society came back to warn us from the other side. So my mom and Nicole were both 35 in June 1994, when Nicole was brutally murdered. My mom remembers the night of the killings because it was also her dad’s birthday, but maybe the memory is so vivid because one sleight of the hand of God or the Devil and that could have been her. Night after night before my dad died it almost had been. He’d been dead seven years by that summer and she was a widowed single-mother alcoholic pre-K teacher raising two children in Los Angeles. The pictures of a bruised-up Nicole Brown Simpson were not unlike those of my mother’s blue-and-yellow face mending from a night of blows. You can make out both beauty and agony beneath their swelling and jaundice, a rebellion against being defined as victim, a subtle aggression akin to vengeance in the eyes that made them reluctant to beg for mercy too often. Like my mom, Nicole had tried calling the LAPD during outbursts, but O. J. often talked his way out of incrimination when officers arrived. And the gaze and policing went both ways in civilian life. As a white woman alone with black kids, my mom was often accosted in supermarket parking lots and asked if she had abducted us. We didn’t always say no so readily. I was somewhere else in the spirit, a fugitive, obsessed with dance lessons and dissociating from our chaotic household, where New Age practices like meditation, chanting to Enya, and eating meat substitutes made of tofu competed with her harder-to-kick habits—cocaine, liquor, and dangerous men.

It was always black industry-adjacent men, some as famous as or more famous than my father, some deadbeats chasing fame who saw my mother’s comfort with them as their come-up occasion. Though she had every intention of being a good mother, she was failing at that and at self-actualization by conflating the act of mothering with that of mating with an imitation of the deceased father of her children. But her efforts were sincere. Trying can be as valid as succeeding in the crucible of mothering and being mothered, I decided, in order to get through it. She was eventually fired from her job as a teacher at a private school where her students included the children of Jamaal Wilkes and other NBA players, after which she spent years in a debilitating depression lying to her parents and siblings, pretending she was still working, living on royalties from Dad’s music, some money I made when I was cast in commercials, and, when that failed, regular trips to the pawn shop to exchange expensive items my dad had given her for money toward the upkeep of some, if not all, of her habits. Like Nicole Brown, my mother dabbled in modeling, and I recall her headshots, which I placed in the plastic casing of one of my school binders as a kid, like a propaganda pamphlet—the one for French class, so that whenever we read passages from Les misérables and put new vocabulary words into morose Hugoesque sentences, there she was, judge and jury. That’s my mom, I would beam, reminding myself too.

As Sydney Simpson had been the night before Nicole was killed, I too was frequently performing at dance recitals in LA in 1994. One account, in a memoir written by Nicole’s best friend, who was in rehab when she died and spoke to her on the phone the night of the murder, tells us that Nicole had tried to enforce a boundary with O. J. at the recital. This enraged him. There are other murmurs suggesting O. J.’s son Jason, from his first marriage, might have been the real killer. He was supposed to cook everyone dinner after Sydney’s recital that night, the rumor implies, but they opted for the nearby restaurant Mezzaluna instead, leaving Jason dejected and resentful. At the time, he was on probation from his job as a chef for allegedly threatening his boss with a knife, and he was the only other family member for whom O. J. hired a lawyer. He had recently stopped taking his medication Depakote, which was prescribed to treat both the seizures and the intermittent rage disorder with which he’d been diagnosed. Some infer the notorious glove and hat were his, hence them famously not fitting, and that DNA evidence was either planted or matched because it belonged to the defendant’s son. Some suggest that he acted with his father’s blessing, or at least his knowledge. Some blame another man, Nicole’s handyman, who was also a serial killer who targeted blonds. It’s said that he confessed to the crimes, both to the police and to his brother, but was dismissed in favor of the blockbuster suspect. Still there are those who hold all of law enforcement accountable, the system that allowed for the televised beating of Rodney King, which had catalyzed the LA riots two years earlier, in the spring of 1992; insinuating that the not-guilty verdict was the retaliation of jurors and citizens given the chance to manipulate justice in their favor for once. I remember watching the riots on television while safely in West LA, which at the time felt like another country. It was hard, with what I’d already seen, to be shocked by violent eruptions. My eyes followed the slow-moving Bronco as if it was a whale in the sea about to come up for air or suffocate us all. The whole scene felt very matter-of-fact and in keeping with what I knew of my own father—pent-up and stifled black power would find its way to the center by any means necessary, was my sense of it. That cavalcade of crisis in the early nineties was almost a relief to me because I didn’t yet have the means to alert those around me to the fact that rage was always there, always coming, never letting up except when transmuted into song, dance, sprint, scream, and even then only temporarily alleviated. I watched calmly like watching a resurrection you know is coming.

During the slow-speed chase I’m on O. J.’s side in that I don’t want to see another black man who reminds me of my father die trying to outrun his demons: I want him to put the gun down. I rewatch the footage now and notice that when they do reach O. J.’s estate, before he turns himself in, his Bronco is intercepted by a distressed and flailing Jason—he approaches the car looking for his father as if he needs to confide something or get contraband to him. He’s histrionic and indelicate and promptly ushered away like a mendicant might be. Everybody is somebody’s decoy in this scene, and what was vaguely thrilling and confounding to watch on live television back then feels transactional now, and unremitting, an excessively long take with no one calling “Cut!”

***

The afternoon of the verdict, back from school where we celebrated and left our classrooms screeching approval and embracing like an innocent family member had just been freed, I’m running through the halls at home cheering, giddy, Freud has abandoned me, no one could tell me I wasn’t avenging some unnamed psychic baggage with that joy. I didn’t realize what I was rejoicing, reliving—my narrow escape from being the daughter in that legend, and the darker more elemental possibility that I was on O. J.’s and my father’s side, whether I liked it or not, in color and lore. I would defend them the way their wives had in front of their children, family, and friends even though I had endured the confusion of witnessing that self-betrayal as loyalty. Every witness became a helpless accomplice in the myth of peaceful reconciliation across racial and gender divides, in the name of love and one big happy lethal American family. I was one of those children, after all, watching her mother excuse her abuser to return to him for the good of her children, or so she told herself, and later even us, the cliché disclaimer that excuses so much pain in the name of union. Women in a battered women’s shelter were pictured on the evening news cheering gleefully on their sad sofa over the not-guilty verdict, like hired extras. I can’t remember my mother’s reaction on the day of. I never asked, or if I did I half listened to her answer and went on leaping and lingering in the perceived win. The redemption symbolism. Were my fellow travelers the men or the women or the children or none or all of them at once? How would we come to know who was good and who was evil in relationships that began as love and devotion and ended in death and dispersion? In a parallel universe my mom and Nicole wave at one another from sunroofs, and you can hear Nina Simone through a speaker somewhere reminding brown baby when you grow up, I want you to drink from the plenty cup. We oblige.

My mother is more of a ghost because she’s survived. When I was thirteen, not long after the O. J. trial, she had another daughter with an aspiring music producer who worked as a security guard by night but quit his job once he got serious with her. She bought him expensive studio equipment and for a couple of years he made mediocre demo tapes that, though I tried to ignore them, I found almost heartbreaking in their limitations. He was a veteran, skilled at crafts and household repairs, and eventually became a cobbler at Rancho Park Golf Course in LA. I found this heartbreaking, too, or maybe I felt betrayed at having to observe what felt to me, as a child who refused to lie to herself when I could help it, like a diluted version of my father encroaching upon my household, buying keyboards and samplers with my dad’s posthumous royalty earnings only to make songs that went nowhere.

He was trying his best and that somehow made it worse for me. My dad had the air of going from glory to glory even at his lowest points, swinging between triumphs—a new wife, a new hit song, a new idea, a new heir, a new commercial or film with his song in it. It’s made my sense of “you’ve either got it or you don’t” almost reflexive. I can feel it within aspirational people the moment I meet them, how far they might go and what trait will take them there, where they might self-sabotage and plateau at the limit of their talent. What it is that the best artists and athletes and even the most captivating philistines possess, is a manner of exerting the personal will, a willingness, that is akin to flying with no net beneath you to the tune of a corny jingle like Chet Baker’s “Let’s Get Lost,” or a sleeker sonic logo like Miles Davis’s version of “Bye Bye Blackbird.” When it is absent, exertion is futile. You’ve got it or you don’t, and it can include all the trouble that accompanies it, trouble which is often fetishized or mistaken for an indication of impending breakthrough. I tell myself I inherited it to get by. At Rancho Park Golf Course, my mom’s new common-law husband would run into the recently exonerated O. J. almost daily. They became friends. He’d fix and shine O. J.’s cleats, receive big tips and big disaffected Hertz rental smiles. It breaks my heart.

The day O. J. died I texted my mom “end of an era.” And we marveled at all the ways that’s true for us. I realized there’s no way she could have watched that trial in anything but irreverent despair, one of her modes, and when I celebrated the verdict unabashedly it was in part to neutralize her authority over me. No one seemed to care as much as I did, how that trial changed the course of pop culture, brought us the Kardashians, brought us to our knees, forced the conflation of heroism and disgrace to become an inescapable tenet of Americanism. We’ve since come to rely on the shadows of our favorite antiheroes to save us from ourselves or restore us to ourselves until justice for these American psychos we invent, then study, together, is that they allow others to experience their prevailing complacency as a virtue. At least they’re not all killers and pop stars who birth deeper ambiguity into the bloodlines of the descendants of slaves, the Greek chorus whispers, ignoring the collective obsession with the dark stars.

When I picture my father and O. J., black-on-white-on-red in the slurred sepia of nineteen-seventies West Los Angeles, the new Negro settlers, brash, elegant, perfect, ridiculous, free to express every formerly curtailed desire, I feel like a voyeur, like I might be their prop, doing exactly what they wished by writing this, by remaining ambivalent and refusing to condemn anyone. All that duality, all that beauty, all those you’re in danger girl stares have, for me, turned into nostalgia for the source of that danger. Then comes this reunion-scene-dread because there will be no reconciliation except with an absence, a cast of haunts. Could Sydney and I wave at one another from this treacherous distance, across terraces, like jesters, or searchlights dimming in thick fog? Then fade out into the grunge-era uniform of tutus and Converse high-tops, white lace socks, pink Capezio shrugs, aloof facial postures to compensate for trauma? So much of our right to a happy ending is tied up in the need for inconclusiveness to persist, and to allow for impossible forgiveness, the kind that demands we remain naive on purpose, never grow up, grow up so fast, stunted, endlessly elaborated. This inheritance of the sins of our fathers which we’ve turned into heartbreak, bravery, wave forms, music. It’s an infinitely renewable girlhood that skips like a broken record and loops not guilty, not guilty, we will not be guilty. Cut.

Harmony Holiday is a writer, dancer, archivist, filmmaker, and the author of five collections of poetry including Hollywood Forever and Maafa. She’s a staff writer for Los Angeles Times’ Image and 4Columns. She’s currently writing a biography of Abbey Lincoln for Yale University Press, a memoir on music, and a new collection of poems.

July 18, 2024

Costco in Cancún

Photograph courtesy of the author.

When we arrive at the Paradisus, I worry I have made the first of many mistakes. Has Costco failed us? A bland remix of Ed Sheeran wafts up from the swim-up bar in the central courtyard into the lobby. My parents do not drink. They do not like to swim. I worry that Ed Sheeran will follow us to our room.

I continue to worry. Three months ago, I called Ramona, a Costco Travel representative, and asked her a question. What is the most popular and well-reviewed of the all-inclusive vacations offered by Costco Travel? Mexico, she said. And then she qualified: Costco members have many different tastes, but most have unanimously enjoyed a stay at the Paradisus La Perla (Adults Only) in Riviera Maya, Mexico. Compared to other Latin American countries, Ramona said, many Americans reported that the Mexican resort felt “worth it.”

I was hesitant to join the crowds of U.S. Americans descending on the Caribbean, but Ramona maintained that Paradisus was the best option for my needs: parents who never vacation, mostly shop at Costco, and harbor a fundamental dislike of restaurants and an extremely low tolerance for what they determine is not worth their money.

So here I am, in Cancun, on an all-inclusive vacation with my family through Costco Travel, and it feels like the world of the wholesale warehouse has somehow been extended down the East Coast to the Yucatán peninsula, all the way to the poor woman in a white polo with the laminated COSTCO TRAVEL sign, who’d been sent to meet us outside of the airport.

If you ever get your hands on a limited-edition set of Costco Monopoly, as I did the week prior to our vacation (on sale at $19.99, down from $28.99), you will see that the normal properties bearing ordinary American street names have been replaced with global supercities in which Costco franchises have a large presence. It will also give you a sense of what it is like to be an envoy of Costco Travel. The board includes Mexico City and Los Cabos in the magenta section (after Montreal and before Seattle), but, tragically, not Cancún. Marvel at the depth of Costco’s lore, translated into Monopoly form: houses replaced with the red food-court picnic tables, hotels with warehouse franchises. My family determines which of the metallic character pieces each of us will play with: my mom, the shopping cart; my father, the forklift; my younger brothers, Nick (twenty-eight) and Duke (twenty-four), and I (twenty-nine): the dollar-fifty soda and hot dog, the Costco membership card, and the plushie bear, respectively. As our little pieces move around the board that is also the world, we simulate not the experience of being a Costco shopper, as you might imagine, but the experience of expanding Costco franchises as if you were an executive. The “Go to Jail” tile is replaced with “Go on Vacation,” adorned with the little “Costco Travel” logo.

We Go on Vacation. At the check-in desk, the concierge regrets to inform us that we have been assigned rooms that are not adjacent. We have actually booked two Junior Suite – Garden Views, Ernesto says, rather than two Master Suite – Garden Views, which is the only class of room that can be adjoining.

Well, my mom says, Costco told us we could be together, and we do not want to pay any more money. Ernesto offers us an upgrade for $1,250. My mom threatens to call Costco, pack her bags, leave, and get back on the plane. Ernesto says that he will see what he can do.

My memory of our adjoining Master Suite – Garden View rooms on the third floor of the Paradisus La Perla is now inseparable from a six-minute, twenty-four-second Facebook film that my mom recorded upon entering. Her voice-over glows from her victory over Ernesto. At the edges of the frame my brothers and I skirt out of view, barely missing the breadth of her camera rampaging through the rooms. I am already exasperated by her marveling. All three of us kids travel for work or are the kind of yuppies who valorize travel that doesn’t look like tourism, so we are either immune to the resort (Nick and Duke) or are a little embarrassed (me, the plushie) to be there.

Here are the adjoining rooms, my mom says, as she instructs my father to open the door to room 1327. She opens the coat closet, her reflection in the mirror briefly visible, then the hallway closet, and then the bathroom closet. She runs a hand along the heavy brown-leather furniture in our sitting room and sits to demonstrate its firmness. She rifles through the empty cabinetry in our twin kitchenettes, noting that the snacks and carbonated drinks in the mini fridge are all-inclusive. There is almost more cabinetry than in our actual house. On the Master Suite balcony, she points out the jacuzzi and then pans the iPhone camera down to the central courtyard, where Ed Sheeran still plays from the DJ’s speakers. Down there is the beach and the various pools, she says, and there’s even nice music.

***

After breakfast the next day, we wander the grounds. The floors are travertine. Throughout the open-air lobby, Noguchi-like tables with plush couches appear at regular intervals. There are unlimited free towels and you are not required to reserve a beach cabana. We are told that there are occasionally dolphins in the sea. A Nescafé-branded shack offers snacks and free coffee in between regularly scheduled mealtimes.

We settle on the beach. At our all-inclusive beach cabana, my mom takes pictures and then squints at her phone as she uploads them to Facebook. I copyedit her post, I swim. Costco Travel guarantees that an entire country will be just as sturdy and robust as the products in its warehouses. A service first introduced to its members in the year 2000, Costco Travel is an extension of the larger Costco strategy, first established in 1976 in San Diego, focused on using its “buying authority” to wrangle deals on bundles including flights, cars, hotels, and experiences and then “[pass] on the savings to Costco members.” To what extent Costco bullies or strong-arms those entities into unsustainable prices is undetectable from its online presence (implacable, family-friendly), but the sheer breadth of offerings (from Disney to Thailand to the Grand Canyon) and the kind of quality control it promises across them (virtually guaranteed) only makes one wonder.

Unlike Costco Travel’s promises, however, where the abatement of lack is total, at the Paradisus, the simulation of unlimited wealth frays at the edges. We are made aware of the funds we did not spend. Or the funds we could spend, if we would like a more deluxe experience. We have to make reservations ourselves instead of through the Personalized Steward promised at the Elite Tier; some of the restaurants require additional fees. When my mother’s Facebook post successfully uploads, we walk into a conspicuously labeled section of the beach called the Reserve—not a part of our non-Elite package—and are greeted by a stretch of sand that is identical to the one that we are on. We are gratified to learn that we have avoided being ripped off.

This is the Costco psychology: quality over brand; value over status. To be ripped off is to be taken for a sucker. It is to have your resources wasted, your hard-earned cash sucked into a delusion of taste, timeliness, or class. It is to be left with nothing; or worse, to be haunted by an alternate timeline in which you saved more money. Costco is a fortress against this loss, and the only vacation that my parents would allow is one that safeguarded against that mentality.

In Costco’s stores, this psychology is purveyed by the architecture. Foregoing the shelves that structure most supermarket or retail experience, Costco simulates the feeling of having infiltrated the storehouse itself, as if you’ve cut out the middleman to plunder the rations of a giant. Maybe he is named Kirkland? You wander the halls fearful that Kirkland and his ominous signature might return at any time to take back his plunder. A Costco haul feels like loot, like stealing, which, of course, is ridiculous, considering that a routine Costco haul can top two hundred dollars, three hundred, rather quickly.

Costco’s products exist elementally. Unlike at the supermarket, where commodities offer weak, febrile envoys, at Costco, commodities are presented as exemplary, body-building specimens. Enjoy the presence of not just Quaker Oatmeal but the platonic essence of Quaker Oatmeal, rendered in full fifty-two-count high fidelity.

When I wander Costco’s loosely marked aisles, sometimes I am struck by visions of lifestyle vignettes prompted by artful arrangements of commodities. For example, between kids’ electronics and outerwear, you can imagine the potential life of the person who would see the connections between the Phantom A8 Electric Scooter ($439.99, a one-hundred-dollar discount), the Tahari Ladies Wrap Coat ($38.99), Squishmallows 16” Assorted Plushie ($11.99) and Jona Michelle Kids Holiday Dress ($19.99, Sizes 2T–12); the person who would see the outdoor holiday party these products might furnish.

Sometimes these vignettes are more haphazard. You might see various commodity flotsam, selected and then discarded at a later point in one’s Costco voyage—the same Squishmallows 16″ Plushie beached on the shores of Nature Valley Crunchy Granola Bar, Oats ‘n Honey island; a Ladies’ Active Stretch Pant draped over pack of Costco Bakery Butter Croissants; Kirkland Signature Krinkle Cut Kettle Chips on a Coddle Aria Fabric Sleeper Sofa with Reversible Chaise, and imagine that no, today, I would rather not. Value, like aesthetics, comes out of self-restraint.

Here, however, in the Yucatan sun, stripped of this architecture, the Costco psychology (“Everything Is a Good Deal”) merges with the all-inclusive hotel psychology (“Everything Is Paid For”) in a sinister marriage of value and engorgement. This nexus of ensuring what you Paid For Is a Good Deal creates a relentless compulsion to feast: when the price of an experience has been prepaid, the value you derive from it is based on your ability to consume. Thus, you need to consume a lot to get your money’s worth. Sometimes consuming so much, for so little, is tiring. Sometimes constantly optimizing the best deal gets in the way of relaxing, particularly after the third or fourth all-you-can-eat meal. Or so I think. It is definitely fun the first few days. My parents treat the Paradisus like what it is: a buffet.

At the actual buffet, for dinner, a mere two hours after our Nescafé snack, there are trays of papaya, a man in a black chef hat serving pork loin, and a bowl of shrimp cocktail, red tails dangling off the crystal’s rim. From our own table, we inspect the other resort-goers. We are too shy to ask any other families if they are also here through Costco Travel, but we suspect as much when we see a Korean family at the cafeteria, walking around with loaded plates. Or might they be here through some other company, offering them an Even Better Deal for what they Paid For? When I survey the desserts with Nick and Duke, I notice that the shrimp cocktail is gone; the bowl is unadorned with tails, it is just a bowl of red sauce. We do a lap, scoop some papaya, consider another mini cupcake. When we are back, the shrimp has been replenished, their tails glistening under the buffet hot lights.

***

One our third day we are waylaid by a man named Armando who is dressed in loose-fitting cotton clothing and a name tag. He asks if we would like free massages. Leading us to an air-conditioned room, he says that his presentation will take thirty minutes. At the end, we will receive a massage voucher to be used at the resort’s spa, which is named YHI. YHI apparently does not stand for anything, other than an exhortation of relaxation, or prayer.

I do not want to listen to Armando. I want to go to the beach. My parents say the beach is going nowhere, and that a massage would be nice. Armando says he will make it quick. He opens his laptop and clicks through a presentation about how we can extend the experience that we have had here at the Paradisus, how we can ensure that we can come back this time next year for the same price. I sit through the session angry. My parents sit through it content knowing that they will be getting a free massage.

I parry Armando’s offers with the words “Costco Travel.” When he offers a timeshare option, I say again, “Costco Travel.” When he asks how much we paid for this vacation, he is unable to best the low price that Ramona has given us. This makes me feel like we are in an armored truck of value, impervious to the rest of the world’s scams.

Armando sighs. He recounts that he has a daughter at home and used to live in Austin, Texas. He found that there were more business opportunities in Mexico and now spends a portion of the year at the resort, selling packages to tourists. He says he didn’t grow up going on vacation but that this job has allowed him to make that possible for his family. He says we are a beautiful family. The receptionist will let us know about the vouchers. He thanks us for our time.

For dinner that night, Nick manages to secure us a reservation at Bana (Adults Only), one of the six all-inclusive dining experiences at the Paradisus. It is our first time eating outside of the general cafeteria, because without the Personalized Steward of the Elite Tier, reservations are more difficult to secure. All of the restaurants and amenities on the Adults Only side of the resort are twinned from the Family side of the resort, with the same architecture and same names, save for the threatening parenthetical. There is, for example, Hadar (Adults Only), the main cafeteria; Mole (Adults Only), the Mexican restaurant; and Chickpea, the healthy restaurant that is de facto Adults Only because of its menu. What happens at an Adults Only restaurant?

The portions are small but lavishly decorated. Some of the sushi is prefaced with the word firecracker and suffixed with dragon. Nick writes down our order on the Notes app so that we can remember the multiple dishes we request. The waiter is too eager to assuage us of our ordering shame, and we surprise ourselves and leave feeling not too full. A marathon, not a sprint, my mom says, much to my surprise.

***

Our appointment at YHI Spa is the next morning. In the hotel room, my mom lays out three different possible outfits before I tell her that she will have to remove them for the massage. I think she is a little nervous. I realize that my parents have never had a massage before. Why have I had so many? This makes me sad and suddenly grateful for Armando.

I feel more obliging now when my mom asks for a family picture in our bathrobes, or asks if we can keep the little soaps they give us in the waiting room. I help her film the sequel to her first Facebook film and document the various pools of the spa, the pool deck with its little rolled towels, and I smile back to the receptionist who smiles at us. My mom says the freeness of the massage sweetened the experience, and that it was really nice, and I realize she is right, and suddenly I am not embarrassed to be at the Paradisus but embarrassed at the highbrow distance that I had tried to graft on to my time at this middlebrow vacation. Ironic consumption is no different from earnest consumption; I am here now, and I am critical and I am also happy, and I breathe in this nice eucalyptus-scented sauna air together with her.

We move from the sauna to the cold pools. We reconvene all together at the outdoor hot tub, where a woman says that this is the first time she’s been away from her five-year-old the whole trip. We ask her if she came with Costco, and she says she didn’t know Costco offered things like this. My mom says Costco should sponsor this trip for all the free advertisements we give them.

Afterward, we lie in a cool, dark room in our bathrobes. We look at our phones. I sip cucumber hibiscus water. Part of the Costco Travel deal is that each of our rooms comes with a hundred-dollar gift card to use at our local Costco. I check my email to make sure that I have received the two promotional codes. I send them to my parents. It feels good that our vacation time on the beach has not gone to waste. It feels good that the Yucatan sun will finance an eventual future back in the Costco warehouse.

Simon Wu is a writer and artist. His first book, Dancing on My Own, is available from HarperCollins.

July 17, 2024

Doodle Nation: Notes on Distracted Drawing

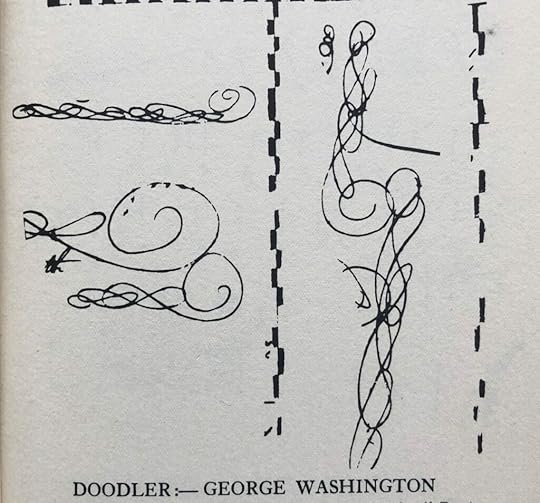

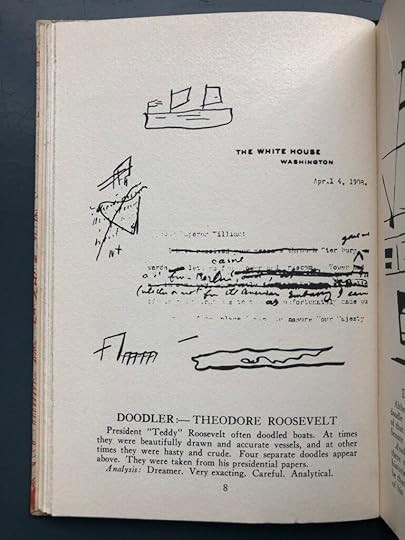

Some doodles by George Washington. Page from Everybody’s Pixillated: A Book of Doodles by Russell M. Arundel, 1937. Photograph by Polly Dickson.

Doodling today is not what it was. Or is it? Google “doodle” and you’ll find the Google Doodle—what Google calls a “fun, surprising, and sometimes spontaneous” transformation of its logo by a team of dedicated Doodlers to commemorate significant, and not so significant, days: from the seventy-fifth anniversary of the publication of Anne Frank’s diary to “Chilaquiles day.” You will also find a long list of apps that take Doodle as their name, including the ubiquitous scheduling tool. This recasting of the word in the age of the internet takes us far from the freewheeling squiggles, squirls, and whirls decorating the margins of telephone books and notepads—which is, perhaps, what doodling once was, in some near-unimaginable bygone era, when we worked with pens and pencils on paper, and when our attention and our hands wandered in different ways.

“Doodling” describes an activity of spontaneous mark-making by an agent whose attention is at least partially directed on something else. It’s the doodle’s apparent spontaneity and whimsy, but also its complicated relationship to attention—that most anguished-over of modern commodities—that makes it ripe for exploitation by the marketing strategies of app-based companies. That is: the doodle is usefully positioned, around the edges of our work documents and our conscious thought, to help us think about how our minds wander and about what those forms of wandering might yield. In a self-styled “doodle revolution,” which she introduces in a TED Talk and a book, Sunni Brown, founder of a “visual thinking consultancy,” explicitly attempts to capitalize on doodling’s wayward energies. Brown praises the potential of doodling for the workplace, coining a technique that she calls “infodoodling” as a tool for honing the attention of workers and thus increasing their “Power, Performance, and Pleasure” (plus, presumably, productivity—and profit). The goal is to “unlock” the potential of “visual language” to realize the full potential of our brains and “to help [us] think” in different ways. Brown’s self-styled revolution sits within a broader trend toward rehabilitating the act of disinterested drawing, as a kind of salve to our frayed modern attention spans. The doodle-curious consumer will find online a baffling array of derivative self-help- and wellness-flavored “guides” to doodling, full of promises to help us “Discover [our] Inner Whimsy and Find Moments of Mindfulness,” as the Daily Doodle Journal has it, or to “enhance your creativity,” according to another notebook of the same name. Doodling, or: how to cash in on the mind at play.

The activity of distracted drawing was first named “doodling” at a very particular moment: in the 1936 Frank Capra film Mr. Deeds Goes to Town. To be clear, the word “doodle” already existed. It possibly derives from the German dudeltopf, meaning “simpleton,” cementing a strand of aimlessness or surplus value that persists in its current form. Before the twentieth century, it was used to refer to a “simple or foolish fellow.” It is in a courtroom scene toward the end of Mr. Deeds Goes to Town that the word was coined in its current meaning: distracted drawing. The film’s oddball protagonist Longfellow Deeds has been proclaimed insane by his relatives for, amongst other things, playing the tuba and giving away his inheritance money. In his defense, Deeds argues that he plays the tuba to help himself think, and points out that everybody is subject to such inane, or insane, distracted fiddlings (or in the idiom of the film, “everybody’s pixillated,” meaning something like “away with the pixies”). Not least pixillated of all is the court psychotherapist, Emile von Haller, who has been trying to make a case for Deeds as a manic depressive. It is the psychotherapist’s own doodle that Mr. Deeds triumphantly exposes in the film, calling von Haller a “doodler,” which, he explains, “is a word we made up back home to describe someone who makes foolish designs on paper while they’re thinking”:

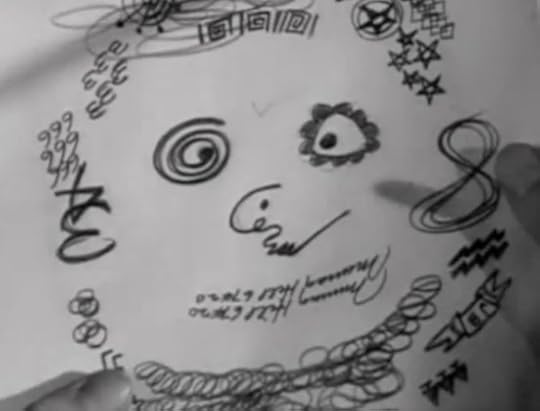

From Mr. Deeds Goes to Town. Screenshot courtesy of Polly Dickson.

Our modern understanding of a doodle thus has its premise in a fictional work. What Deeds shows us is the first doodle to be called a doodle, but of course it’s not one; it’s a drawing of a doodle. It’s as if here the scriptwriter has aimed to include all those archetypal forms that we are likely to find ourselves drawing when bored—stars, numbers, swirls, figure eights—drawing them together into the shape of a manic-looking face, such that it can be easily “read.” This gives it a satisfying finish, the snap of recognition. The fantasy of a doodle here, as a signifying system, bears witness to the investments we make in them—those investments have to do with clear, correspondent meaning. If it is mad it is also productive in a quiet and legible manner.

Whilst humans have presumably doodled for as long as they have written and drawn (the art historian Ernst Gombrich has studied the idle scribblings made by Napoli bankers on their ledgers in the fourteenth century), once psychoanalysis had begun to imagine the doodle as a key to understanding the unconscious mind, it was no longer possible to doodle innocently. Mr. Deeds Goes to Town, with its Austrian psychotherapist a parody of Freud, is a response to a frenzy for all things psychoanalysis in the thirties. Carl Jung, Hans Prinzhorn, and Alfred Adler had all previously written about the significance of our absentminded drawings or Kritzeleien (a word that is better translated as “scribblings”) in a psychotherapeutic context.

In Capra’s film, when Deeds asserts the universality of doodling and fidgeting, the doodle emerges, with its new name, from psychoanalytic papers into the Anglo-American mainstream consciousness. (Victoria Riskin has blogged about the “grave injustice” committed by the Merriam-Webster dictionary in failing to attribute to her father, Robert Riskin—the screenwriter of the film—the first use of the word in its current sense.) The doodle gained its name in a self-mockingly circular logic whereby the doodle is declared singular and meaningful only in order to show that the analyst himself is as mad as everybody else. All of this was in service of defending Longfellow on the charges of madness for having given his inheritance money away, drawing both money and doodles into the task of proving or disproving one’s madness. From this moment on, the doodle would continue to be caught up in an intensifying desire to make use of such drawings, to see what they might yield.

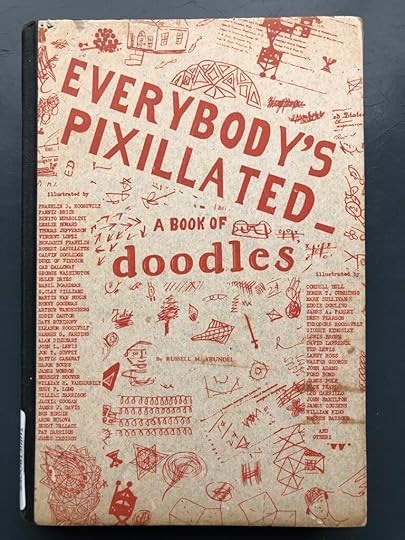

Cover of Everybody’s Pixillated: A Book of Doodles by Russell M. Arundel, 1937. Photograph courtesy of Polly Dickson.

A book that consolidated the word’s contemporary meaning is a strange, slim volume by Russell M. Arundel called Everybody’s Pixillated—a direct citation of Capra’s film—first published in 1937. Across its pages are reproductions of scrappy marginal drawings, documents of “priceless surrealism” sketched, scribbled, and doodled by presidents, senators, the Prince of Wales, lawyers, and other notable figures (almost all of them men).

Everybody’s Pixillated is both a paper exhibition of doodles and a whimsical manifesto in favor of paying attention to the chatterings of the unconscious mind. A case study at the heart of the book cements Arundel’s basic premise that doodles are pictorial clues to the secrets of what he affectionately terms “old man subconscious.” According to this story, a certain Private Marvin Shores liquidated his assets and buried the gold and silver bullion somewhere on his grandfather’s estate before going off to fight in World War I. When Shores returned in 1918, suffering from what was then called shell shock, his grandfather was dead and he had no memory of where he had buried his treasure. It was from the doodles he made during a telephone conversation—“crude drawings of rabbits, sketches resembling guns, and the word ‘booty’ ”—that a friend familiar with the secrets of “automatic writing” was able to help him unlock the location of his treasure: buried beneath an old rabbit hutch. Whether this little story is apocryphal or not does not really matter in the context of Arundel’s project. For it works as a founding myth of doodling and doodle-reading, justifying Arundel’s excavatory enterprise with the promise of unconscious treasure ready to be unturned. This version of doodling’s founding myth, like the scene in Mr. Deeds Goes to Town, is centered on capital. Paying attention to doodles will convert the apparent work of distraction back into attentional currency—and hard gold. This is the real work of making doodles mean.

Arundel’s doodle book takes Riskin at his word, and is premised on the notion that everybody is inhabited by the compulsion to doodle. “This is a pixillated book for pixillated people,” he declares mischievously in the foreword. It is, in one sense, the document of one man’s obsessive pareidolia: that state of mind perched tantalizingly close to the state of paranoia, in which meaningless or random marks are configured into a message or picture, as when we catch a glimpse of a face in a wall or a buttered slice of toast or in a coffee stain. His analysis of Theodore Roosevelt’s boats and scribbles is delivered with a poetic sparseness: “Dreamer. Very exacting. Careful. Analytical.”

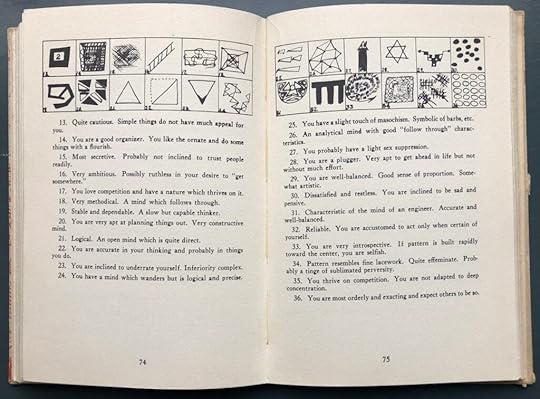

Page from Everybody’s Pixillated: A Book of Doodles by Russell M. Arundel, 1937. Photograph by Polly Dickson.

Are we mad because we doodle—even the most apparently rational minds amongst us, even those politicians whose drawings, some of them quite baffling indeed, feature in this book? Or are we mad because we are irresistibly drawn to such images and to the impossible task of decoding them? Here is another contradiction aroused by the doodle: that what seems like an intensely private activity can in fact trace our relationships to other people; that the doodle has a kind of social life.

Arundel was, by all accounts, something of an eccentric. Having worked as a lawyer at Capitol Hill, in the presence of the politicians whose scrappy papers he was able to salvage from the waste paper basket, Arundel was also the president of the Pepsi-Cola Bottling Company of Long Island, a keen hunter and fisherman, and, more surprisingly, founding father of the Principality of Outer Baldonia, a micronation in Nova Scotia that existed for twenty-four years. This odd episode in Arundel’s life is the story of a fabricated reality, an irresistible parody of nation building, that made Arundel into an unlikely hero of the Cold War.

In 1948, Arundel purchased for $750 a four-acre island off the Tusket Islands that he had come across whilst fishing. He called it Outer Baldonia, proclaimed himself Prince of Princes, and limited the citizenship of his newly founded principality first to men, then to tuna fishermen. Back in Washington, Arundel and his subjects managed to get their dubious male utopia onto an official map of Canada and drew up laws, a national flag, and a currency, the Tunar. They even sketched out a declaration of independence:

Let these facts be submitted to a candid world. That fishermen are a race alone. That fishermen are endowed with the following inalienable rights: The right of freedom from question, nagging, shaving, interruption, women, taxes, politics, war, monologues, cant, and inhibitions. The right to applause, vanity, flattery, praise, and self-inflation. The right to swear, lie, drink, gamble, and silence. The right to be noisy, boisterous, quiet, pensive, expansive, and hilarious. The right to sleep all day and stay up all night.

As a bit of hypermasculine silliness, this declaration of the legal rights of its citizens to lawlessness is written in the good-humored register of Carrollian hyperbole. It was also an immense feat of bureaucracy. When a writer of the Moscow Literary Gazette took (or seemed to take) the wording of the constitution seriously and declared Arundel a tyrant, Arundel responded, fully in the spirit of things, by formally declaring war on the Soviet Union. Needless to say, it all came to nothing, and in the seventies Arundel sold Outer Baldonia to a society for the protection of birds for a single dollar.

In both the doodle book and the fictional nation, Arundel rouses up the nonsensical underside of bureaucratic processes. Both are governed by a dreamlike, “pixillated” logic of overturning our expectations of paperwork. In the doodle book, he exposes the unexpected byproducts of writing, thinking, and paying attention; in the Outer Baldonia episode, he conjures up a fictional state that, on paper only, resembles a real one. Arundel was interested in the indiscriminate chatter that tangles and clusters at the edges of our conscious thoughts and decision-making processes. A significant portion of the doodle book is given over to an autographic history of the process of writing out an agricultural relief bill—or rather, the ways in which it is “doodled into shape”—and passing it through Congress and Senate. Arundel, in the guise of enthusiastic “doodlebug,” narrates this version through the doodles of its authors. Stately political processes, he shows, go hand in hand with the madcap arabesques, squiggles, and scribbles of politicians’ scrap paper. Doodling here is writing’s other self, its shadow form.

From Everybody’s Pixillated: A Book of Doodles by Russell M. Arundel, 1937. Photograph courtesy of Polly Dickson.

As much as they tell us about writing, doodles tell us about reading. They get at the heart of the critical act by seeming to solicit interpretation, then skittering away when we get down to the business of studying them. They might, after all, register no more than the inky imprints of the pleasures of mark-making or the necessity of testing the pen. Take a doodle too seriously, and you risk finding only your own desire for meaning bounced back at you. Despite Arundel’s tongue-in-cheek taxonomizing, and the earnest efforts of graphologists ever since, no systematic vocabulary for the understanding or critical interpretation of doodles, no Doodle Dictionary, has ever gone mainstream. And of course that’s the point. By telling us how to read them, Arundel is asking us a question about reading. It’s a fitting quirk of Arundel’s own life that in the Outer Baldonia episode he seems to have attracted, in the character of the Russian journalist, precisely the kind of exaggerated seriousness the doodle book flirts with (although, to be fair to the Russian journalist, nobody seems clear on whether he was engaging in satire of his own). For the book knows itself to be a kind of joke: its motive, he states on the first page, “is good humor.” “If the chart doesn’t happen to tell the truth,” Arundel reminds us, “just remember the foreword—‘This is a pixillated book for pixillated people.’ ”

Whether or not we see doodles as subversions of work, as what art therapist and historian David Maclagan (who has studied the history of the doodle) has called a kind of “graphic truancy” or “miniaturized graffiti,” or as hieroglyphs of hidden parts of the self, or as a way of unleashing hidden potential and maximizing our performance as workers—or as performing some other kind of work—the most fascinating things about doodles are the desires of their readers.

Pixillation attracts and engenders pixillation. This book about doodles is a book about how we pay attention to each other, about the forms of attention we are able to pay or give. Although Arundel’s book is a dazzling treatise on paying attention to parts of the human mind that cannot usually be caught and directed by such attention, at its heart, really, is the curious figure of the self-titled “doodlebug,” who pictures himself creeping gleefully between wastepaper baskets in the offices of congress, asking senators to hand over their scrap paper.

Polly Dickson is an assistant professor in German at Durham University. She is the author of Romanticism, Realism, and the Lines of Mimesis and is at work on a project on doodles.

July 15, 2024

At the Five Hundred Ponies Sale

Photograph by Alyse Burnside.

I arrived in New Holland, Pennsylvania early, around 7 A .M., and drove down the main street, taking in the produce stands, machine repair shops, and country stores that bear Mennonite names: Yoder, Yoacum, Yost. Cattle graze in unpeopled fields, and in one, three Staffordshire Draft horses stood obediently, harnessed to a plow, as though posing for a painting.

Lancaster County is home to many auctions, but the New Holland Sales Stables have been a mainstay of the Amish and Mennonite communities since 1920, and boast the largest horse auction this side of the Mississippi. The sale barn auctions more than 150 horses, ponies, mules, and donkeys beginning at 10 A.M. sharp every Monday, rain or shine, regardless of season, and even on holidays.

The barn opened at 8 A.M., so I made my way across the patchwork of Lancaster County’s small towns, through East Earl Township, Blue Ball, and Goodville, past a Christian playground manufacturer with replicas of Noah’s ark, a taxidermy shoppe called Nature’s Accent, Shaker furniture showrooms, saddleries, dozens of churches, and hand-painted signs advertising asparagus, tulips, watermelon, raw milk, whole milk, lemonade, onions, potatoes, homemade berry pies, salvation.

NEW HOLLAND SALES STABLES INC. was painted in faded red capital letters on the corrugated tin barn. The barn was made up of a large central building with a sale arena flanked by stadium bleachers, a concession stand, and an auctioneer’s booth located ringside. A line for the concession stand had formed at the entrance. “Get your hot dogs now, they’ll sell out by ten,” one woman said to her husband. A couple of old Amish men sat on a bench drinking coffee and spitting dip into empty cups or onto the dusty floor in front of them. One wore a thick denim chore jacket over a blue gingham shirt, muddy cowboy boots, and a white straw hat. This seemed to be the uniform—any place can attract regulars. His friend wore a lavender button-down under thick black suspenders. His floppy white hair hung past the brim of his cowboy hat, making it difficult to tell where his head hair stopped and his long white beard began.

I heard about the auction from a coworker of mine at the equine therapy barn in Queens where I used to work as a stablehand. He called it the Five Hundred Ponies Sale because of the large stock of horses available each week. I read a blog post titled “First Time Auction Advice,” which instructed New Holland auction-goers against wearing fancy clothes or bright colors. “The name of the game is ‘blend’. You don’t want to appear to be an outsider and draw unnecessary attention to yourself,” it warned. Most of the horses that find themselves at auctions come from breeders, or have aged out of their hard labor jobs or failed in their roles as birthday party ponies or lesson horses. Some are simply no longer wanted by their owners. The auction decides their next life. They might be sold again as pasture companions, kids’ horses, or carriage horses, and sometimes, they are sold to slaughter.

The horses waited in rows, tied to posts in the alleyways of the smaller barns attached to either side of the sale arena. Each eligible horse was assigned a number, which was printed on a sticker, then affixed to one side of the animal’s hips. I walked down the aisles looking at the horses to be auctioned. I touched their shoulders, their noses, their hindquarters. They flinched, then grew curious, stuck their heads out toward me.

Photograph by Alyse Burnside.

Some of the horses danced around anxiously or pawed at the ground. Others seemed like they’d been sedated—they hardly reacted when I reached out to touch them, their heads dipped down heavily into their hay troughs, eyes like wet marbles. A pair of chestnut Arabians tied to a post got spooked when a small boy cracked a whip against the concrete floor. Hooves beat against the ground, veins popped, nostrils flared. One of them reared and nearly bashed her face against the wooden rafters. A handler shortened her rope, tying her more tightly to the post; patted her hindquarters; and moved on.

At 9 A.M., the tack auction began. The auctioneer, a middle-age man in a gray fleece zip-up, took his seat in a booth at the front of the ring. The crowd trickled in, a constant drone shuffle of cowboy boots on the gritty floor. The room was abuzz with chatter until the auctioneer leaned forward in his folding chair, bringing his mouth to the large table mic in front of him, and began.

Show saddles, bridles, vet wrap, saddle pads, lead ropes, shovels, halters … even horseshoes—the vast umbrella of horse accessories and equipment could be bought at the tack sale. “If your horse needs it, we’ve got it,” the auctioneer sang. I took a seat at the very top of the bleachers. In the ring, a young Mennonite boy in a felt cowboy hat, double denim, and boots walked in a circle, showcasing the merchandise as the auctioneer began calling numbers. The higher the price, the tighter his circles became.

The woman next to me bought twenty-four bottles of fly spray, eight trailer ties, five seven-foot lead ropes, ten neon-green-and-pink water buckets, and eight children’s lassos—for a fraction of the price she’d pay at a Tractor Supply Co. or saddlery. “I hope you buy horses the way you buy tack,” the auctioneer joked. “I’m trying,” the woman said.

Behind me, a miniature pony began kicking wildly at her neighbors. She stood no more than four feet tall, her flaxen mane was long and crimped, her tail tied with a red bow—she was well-fed, shiny and dappled, with feet polished black like a Breyer Horse’s. As if by her demand, the horse auction finally began. There were two categories of horses for auction: “as is” and “sound.” A sound horse is physically fit for riding, while the “as is” designation guarantees nothing about the horse’s health. There was a vet on the premises to offer a preliminary look at any of the horses available, but he was on the auction’s payroll and couldn’t speak to their wellness aside from general impressions. Sound horses began at a thousand dollars, “as is” at a hundred.

It’s widely known that kill-pen dealers are regulars at auctions. Kill-pen dealers, or vendors who buy horses to sell them for slaughter, are contracted by companies in Mexico and Canada, where, unlike in the U.S., horses can be sold for meat. Or dealers will capitalize on the sympathies of horse rescues in the U.S., selling them for a higher price than they would make at slaughter.

I noticed two men leaning against the ring. One chewed gum like the Energizer Bunny, the other remained expressionless as he bid three hundred dollars on a thirteen-year-old Standardbred mare, “as is.” The slightest flick of his wrist caught the auctioneer’s attention. For a few hundred dollars a piece, two, then five, then seven “as is” horses belonged to him. It was clear this was not the man’s first euphemistic rodeo.

Then the first “sound” horse was announced. A six-year-old gray quarter horse pony with a broad face and short-cropped mane that stuck up like a mohawk. He belonged to the auctioneer himself, bought for his daughter who had since “tired of him,” he said with a chuckle. A young Amish woman wearing blue riding breeches under her long floral dress cantered him down the ring, stopped him on a dime, then spun him quickly and rode back to the gate. The bidding started at a thousand dollars. “Onethousandonetwotowandaquarterthreecanigetthreeandaquarter, once, twice, one, three, andaquarter.” With that, the auctioneer’s daughter’s horse was sold to a flinty-looking middle-age woman in stonewashed jeans, worn Wrangler boots, spurs, and a faded T-shirt that read, “I’d get a job but my horse needs me!”

The woman next to me bid on #408, a sixteen-hand Morgan mare. “Local and guaranteed to ride,” the auctioneer promised. She bid against the Energizer Bunny, who wiped his palm through his slicked-back hair between bids. He leaned against the fence on the other side of the ring, not far from the other dealer. They took turns raising the bid a whole, half, then a quarter, before she won out at $1,825. “Thank you,” she said to her husband as their new mare rode out of the ring. “Congratulations,” I said. “How many do you have?” But the woman was focused on the next eligible horse, not wanting to miss a thing. “Three … four now,” she replied, without breaking her gaze on the auctioneer’s darting wand. A too-thin red roan with small ears and a vulpine face stood at the gate with one foot cocked, dragging it slightly as he trotted in front of the bidders. He went for four hundred dollars to the man with the slicked-back hair. I watched a man across from me house two large hot dogs.

Over the next half hour, dozens of horses were showcased, the rest of their lives in our hands: the auctioneer’s, the handlers’, the crowd’s, the kill-pen dealers’. Buggy horses, yard ponies, off-the-track racehorses, “pasture puffs,” companion seniors, green horses with show potential, workhorses, a small Appaloosa pony with Dalmatian spots, a pair of donkeys advertised as “the very best lawn mowers you can get,” and a scruffy pony with one blue eye who looked just like my childhood horse, Shirley. Shirley I never tired of, but at some point it became too expensive for my parents to keep her, and I came home one day to find her gone. My interminable ache. It occurred to me, sitting there, that she might have ended up at an auction like this one, dancing and throwing her head back before a stone-faced crowd.

Photograph by Alyse Burnside.

Most people leaving the auction with new horses wore an air of something like excitement, but without obvious joy. Perhaps it was the daunting sense of duty, the labor that awaited them—preparing the barn for one more horse, hauling one more hay bale into the barn each day, one more farrier bill, one more horse to ride, to train. Cutting through this apprehension, a young girl stood in front of the barn with her new pony, the number 183 still pinned to his rear. She threw her arms around her pony’s shaggy neck, pealed with glee. Her father pulled his cell phone from his hip holster to snap a photo.

Those leaving without horses seemed like neighbors. They milled about drinking coffee and chatted about the week’s livestock, their wives, husbands, children, and how much rain there’d been already this season. An average Monday at the sale barn.

As I drove out of town, I passed horse trailers on both sides of the highway. Manes and tails blew through slats in the interstate wind. When I reached the New Jersey Turnpike, I turned, and they went wherever it was they went. As is.

Alyse Burnside is a writer living in Brooklyn. They’re working on a collection of essays about work, attachment, and horses. Their work has appeared in The Atlantic, The Believer, The Nation, DIAGRAM, and elsewhere.

July 12, 2024

Sad People Who Smoke: On Mary Robison

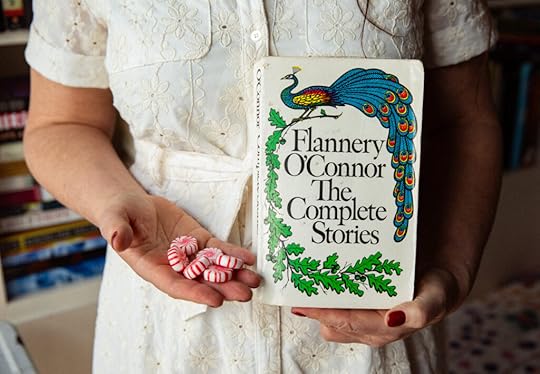

ROBISON, HER DOG, AND, CLOCKWISE FROM BOTTOM LEFT, HER BROTHERS, LOUIS, TOMMY, MICHAEL, DONALD, AND ARTHUR, 1982. PHOTOGRAPH BY JEAN MOSS-WEINTRAUB, COURTESY OF MURRAY MOSS, FRANKLIN GETCHELL, AND ESQUIRE MAGAZINE.

Mary Robison is interviewed by Rebecca Bengal in the new Summer issue of The Paris Review.

I am reading Mary Robison and thinking about smoking. Specifically, I’m rereading Robison’s 1979 debut, Days, a collection of short stories about sad people who smoke. There’s Charlie Nunn, the retired teacher who smokes while supine on the rug, letting ash accumulate on his unshaven chin. There’s Guidry, the alcoholic who rests the day’s first cigarette on his sink’s soap caddy as he shaves. There’s Gail, the bride whose father strikes a match on his trouser fly to offer her a light. These characters don’t smoke because they’re sad; they smoke because it’s the seventies. Still, I’m tempted to read all the smoking as symptomatic of a condition that afflicts characters across Robison’s oeuvre: a near pathological refusal to consider any moment but the present one.

When I first read Robison, I was also a sad person who smoked. That was seventeen years ago. I was an M.F.A. student living in my first New York apartment, a sixth-floor junior one bedroom ($1,300 a month!) just south of 125th Street on Manhattan’s West Side. I’d take my Camel Lights onto the fire escape, which offered a view of the shimmering Hudson. Unlike the characters in Robison’s stories, whose default mode is passive resignation, I was romantic; sadness and smoking were aspects of the “young writer” persona I hoped to cultivate. I’m embarrassed to admit that I once defended my habit to a girlfriend by explaining that cigarettes were my friends before she was around and that they’d comfort me after our inevitable breakup. All this is not to say that I wasn’t sad, or that I didn’t love smoking, but that both were integral to my conception of self.

Robison’s 2001 novel, Why Did I Ever, also became integral. On its surface, the story of Money Breton, a Hollywood script doctor and mother of adult children who takes Ritalin and drives around the American South, had little in common with either my life or the autobiographical first novel I was writing. But Money’s narration—pithy, sardonic, and unsentimental, but also stealthily poetic and fundamentally humane—struck a tonal balance I’d been struggling to achieve in my own work.