The Paris Review's Blog, page 30

May 20, 2024

Televised Music Is a Pointless Rigmarole

Herbert von Karajan directing Verdi’s Messa da Requiem in Milan’s La Scala theater. Aired in West Germany on November 26, 1967.

From an interview in Der Spiegel (February 26, 1968).

DER SPIEGEL

Professor Adorno, you once dismissed radio concerts as empty strumming and chirping. Does this characterization likewise apply to the performances of baroque concertos, classical symphonies, masses, and operas that are ever more frequently available for hearing and viewing on the first and second television channels? Is it possible to present an adequate performance of music on television?

THEODOR ADORNO

As an optical medium, television is to a certain extent intrinsically alien to music, which is essentially acoustic. From the outset, the technology of television occasions a certain displacement of attention that is disadvantageous to music. In general music exists to be heard and not to be seen. Now one can certainly say that there are certain modern pieces in which the optical aspect also has a certain importance. But at least in the case of traditional music—

SPIEGEL

Obviously on German television—aside from the third channels—only traditional music is performed …

ADORNO

—in the case of traditional music there is something unseemly about the whole thing, an unseemliness naturally occasioned by the fact that by analogy with its counterpart in radio, a piece of machinery like the television-production process has got to be constantly fed, that something has got to be getting constantly stuffed into the sausage machine. On the whole I believe that the very act of performing music on television entails a certain displacement that is detrimental to musical concentration and the meaningful experience of music.

SPIEGEL

We don’t believe that the receptive capacity of consumers of television is completely engrossed by the optical element. Don’t you think that the medium of television can also be acoustically stimulating?

ADORNO

I by no means wish to deny that the medium of television can also be acoustically stimulating, or even that its optical procedures can have certain benefits for music. Perhaps I can clarify this with an example: my late teacher Alban Berg was always toying with the seemingly quite paradoxical idea of having Wozzeck, which really is one of the last operas in a strict sense, made into a film, not, to be sure, out of anything like a desire to break into the so-called mass media—he had absolutely no interest in things like that—but because he believed that by filming the work one could make its musical events more malleable, so to speak, than is the case in normal opera performances. For example, through the techniques of the roving microphone, which of course correspond to the changing camera positions in the film, one could bring out the main voice at any given time more meaningfully, more malleably, than was possible in an ordinary opera performance in Berg’s opinion.

SPIEGEL

Admittedly, such possibilities don’t seem to be available in television. … The technical means, the execution, the craftsmanship involved gains primacy over the music.

ADORNO

Yes, one’s attention is drawn away from the essential things and towards the inessential ones, namely, away from the music as an end and towards the means, the manner, in which the keyboardists and wind players and string players are playing it. But I’d like to point out that these irritating practices are well established in the techniques of all forms of mechanical reproduction. In radio and in many gramophone recordings one also encounters a predilection for accentuating so-called principal voices or so-called melodies out of all proportion to their place in the musical fabric. This is the fault of the sound engineers, who subsequently engage in fundamentally quite unmusical procedures by surgically extracting these voices, which is quite in keeping with their—if I may say this—unartistic intuitions and is also congenial to the highly problematic taste of the public. … What results from this is that certain middle-of-the-road so-called euphony, that culinary seasoning of the sound at the expense of all the structural elements of the music.

SPIEGEL

The culinary element seems to us to be especially prominent in music broadcasts. A candlelit Karajan and Menuhin concert framed by the plush furnishings of a Viennese salon; Bach passions and cantatas in the obvious setting, a baroque church. As the distinguished vocal soloist is singing his part …

ADORNO

The listeners make furiously sorrowful faces …

SPIEGEL

… And the camera fondles lovably chubby-cheeked putti and Madonnas. Is this acceptable?

ADORNO

It’s horrible, the worst sort of commercialization of art. Here the mass media—which precisely because they are technical media are duty-bound to forgo everything unseemly and gratuitous—are conforming to the abominable convention of showcasing lady harpsichordists with snail-shell braids over their ears who brainlessly and ineptly execute Mozart on jangly candlelit ancient keyboards. I think it’s more than high time for purging the mass media of all this illusional kitsch and of the whole Salzburg phantasmagoria that’s forever haunting it. … It engenders an absolutely inadmissible image, above all because here an illusional element also supervenes; it’s as if one were present at some sort of shrine where a unique ritualistic event were being enacted in the hic et nunc—a notion that is completely incommensurable with the mass reproduction that causes this same event to be seen in millions of places on millions of television screens. … One can never shake the feeling that such things must be regarded as grudgingly doled-out servings of schmaltz within the politics of programming, wherein the so-called desires of the public, which I have absolutely no inclination to gainsay, are oftentimes employed as an ideological excuse for feeding the public mendacious rubbish and kitsch. I would also include in this kitsch the kitschified production styles applied to the presentation of so-called—I might have almost said rightly so-called—classic cultural artifacts.

SPIEGEL

Take for example Brahms’s German Requiem on the second channel. The images concurrently broadcast with it were of trees, forests, lakes, fields, monuments, and cemeteries.

ADORNO

The acme of wanton stupidity.

SPIEGEL

Professor Adorno, a pedagogical argument is also always trotted out in connection with this. According to this argument, televised music gives consumers a preliminary introduction to the work and thereby stimulates them to attend concerts or opera performances in person. What do you think of this kind of musical therapy?

ADORNO

It’s wrong. I don’t think there’s any such thing as a pedagogical path to the essential that starts out by getting people to concentrate on the inessential. This sort of attention that fixates on the inessential actually indurates; it becomes habitual and thereby interferes with one’s experience of the essential. I don’t believe that when it comes to art there can ever be any processes of gradual familiarization that gradually lead from what’s wrong to what’s right. Artistic experience always consists in qualitative leaps and never in that murky sort of process.

SPIEGEL

There’s yet another argument with which the cultural-industrialists rally to televised music’s defense. The fact that operas and concerts are reaching a mass audience via the television screen is something they equate with a cultural resurgence. What do you think of that?

ADORNO

Once again I regard this as a completely wrong argument. Although I have no desire to put in even the faintest of good words for some fusty ideal of interiority, it seems to me that above all something profoundly inauthentic is going on here, because the works themselves aren’t indifferent to the manner in which they are presented. A televised Figaro is no longer Figaro. Consequently, when the masses come into contact with it, they are no longer by any means coming into contact with the thing itself but rather with a predissected, cliché-ridden product of the culture industry, which gives them the illusory sense that they could become actively involved in culture. For quite some time now, so-called great, traditional music has been following the same trajectory as the one completed by Raphael’s Madonna della Sedia once it was hanging on the wall of each and every petit bourgeois bedroom.

SPIEGEL

So then, Professor Adorno, are you really of the opinion that for the time being televised music is a pointless rigmarole?

ADORNO

Indeed, I really am of that opinion. Televised concerts and televised operas are a complete waste of cultural activity.

SPIEGEL

Professor Adorno, we thank you for this interview.

From Theodor W. Adorno’s Orpheus in the Underworld: Essays on Music and Its Mediation, translated by Douglas Robertson, to be published by Seagull Books this July.

Theodor W. Adorno (1903–1969) was the author of Minima Moralia, Philosophy of Modern Music, and Prisms, among many other books.

Douglas Robertson is a translator of German-language literature.

May 17, 2024

New Books by Nicolette Polek, Honor Levy, and Tracy Fuad

Mural at the Amargosa Opera House. Carol M. Highsmith, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Gia wants to disappear. This is an ordinary desire while in pain. In moments of hardship, it is tempting to admire the ascetic. The imagined glory of solitude is that our inner life will become a source of endless pleasure. Of course, this is fiction. Everyone is touched by loneliness, while alone and in company. To bear it, we must find something from beyond to sustain us. This is what Nicolette Polek’s Bitter Water Opera seeks.

Polek’s debut novel, published last month by Graywolf, shows us the mechanics of a mind negotiating a rupture. It’s easy to say that Bitter Water Opera is about a breakup, but that would be a narrow view. As in real life, the relationship comes undone downstream from a more preeminent but obscured event in the emotional life of one or both parties. Gia’s relationship seems fine. It is sparsely characterized, mostly through memories of excursions dotted with palms and bougainvillea. But for Gia, this pleasantness is intolerable. She starts acting erratically, flirting with strangers. Soon after, she leaves both him and her post in a university film department. Her mental state is vague, made up of a loose association of memories, summoning trinket-like facts, like “the prevalent tone in nature is the key of E.” She has traded a life in exchange for something she has not yet learned to want. But what is to be done when desire turns its cheek to you? What is there to want when you’ve stopped wanting what you wanted? In the absence of wanting, it is helpful to find a human example to follow, try to insinuate yourself in their map of desire and its attendant habits.

Through the figure of the dancer and choreographer Marta Becket, Gia tries to summon a model for a life she could find agreeable. “Marta got through without needing, grieving, or waiting on someone, and now, after death, I was her witness, hoping that she, in some act of imitation on my part, could fix my life.” Becket was a real woman who abandoned her life as a ballerina in New York in favor of the oblivion of Death Valley, where she dedicated herself to running a previously abandoned recreation hall to showcase her one-woman plays and ballets. At the Amargosa Opera House, Becket performed her own choreography for nearly fifty years. In the early days, her only audience members were the faces of heroes and loved ones that she had painted into the trompe l’oeil mezzanines, from which they permanently applauded. Her husband, Polek writes, was off with the prostitutes in town, trying to withstand the fact that Marta did not need him. Eventually she became a cult figure, luring crowds, the press, and lost women like Gia into her orbit, even after death.

After Gia writes her a letter, the ghost of Marta enters Gia’s life, and with her a flurry of activity. The pair have full days together: painting, picknicking, hiking. For a while Gia pantomimes Marta’s actions, but it soon becomes evident that she is not yet ready to stand up to the task of living (she attempts to get back together with her ex-boyfriend). The ghost of Marta exits, taking her watercolors with her. Gia descends into catatonia. Towards the middle of the novel, Gia looks out over the pond outside a house in the country where she’s staying alone and sees the floating corpse of a dead deer. This visceral encounter with a rotting animal draws Gia out of the misty, desultory realm she has lived in for so long and forces her to contend with the bare facts of nature, and the nature of herself: she does not live the life of an embodied subject. Her central problem is her tendency for “limerence,” as she calls it, which leaves her chronically unable to connect with the present. But this insight is brief, and an epiphany does not cohere. “The smell faded for good, and with it my revelation.” Here she is confronted with the mystery of herself: something has peeked out from the curtain behind which her mind stages a secret play. It is a glimpse at something that will eventually be revealed in full, but she must wait. Insight tends to come soon after we are emptied out completely. As the epigraph notes, “Blessed are the poor in spirit,” for theirs is the kingdom of heaven.

—Hayley J. Clark

Being more “connected” than ever to the world, there can be a strange sensation in trying to determine where we end and where everything else begins. As Tracy Fuad writes in her powerful new book Portal, “I have imagined / The rootlets / Of new nerves / Extending / To carry sensation / Back to the crescent / Of numbness / Above the line / That marks the boundary / Of no dimension / In between us.” Life’s events are bizarre, but at the same time all too ordinary: they might be stalking an ex online (who has deleted the photos of you together), the contortions of learning a new language, or even the sensation of pregnancy. Fuad is the poet of this porous feeling, and she follows the tides of that ever-changing boundary. This condition, both banal and terrifyingly expansive, is addressed in a poem cleverly titled “Hyposubject”: “How do you feel when the world is big inside your head? // Another common moment.” What’s common can be elusive—we can forget how strange what we’re doing is—but then it proves to be a source of shared strength, if effort is taken to open its hidden possibilities.

This transformation of the everyday has much to do with the clarity of Fuad’s forms, which range widely but fit together seamlessly in the book’s structure: the long unspooling of short lines down the page in a ribbon, the single-line monostitches that open up space on the page and test each declaration. Together, they make a theme of the difficulty of managing discrete information, the struggle to find form within flux. Fuad’s excellent poem “Birth” was published in this magazine, but it’s the shortest poem in Portal—to me, one of Fuad’s great strengths is the mid-length lyric. Although she is capable of marvelous compression and precision (“After the storm, I step on a buried bird at the beach. Soft as a loaf of bread.”), the longer poems are true to the book’s title, which I think conveys a spirit of dilation. Once the portal is open, the poet must remain open to connections and continuations. At the same time, Fuad keeps her subjects clear and focused, from a meditation on German business customs and its language to a poem about the varieties of edible acorn on Cape Cod. Although the screen is always just a glance away, Fuad doesn’t feel bound to it—inch by inch, pixel by pixel, the poet’s attention recovers its agency. Nor is Fuad trapped in her first-person subjectivity—a stunning, more abstract sonnet sequence anchors the book, forging surprising intimacies from some of the book’s most “difficult” language.

Many writers either pretend that the phone glued to the hand doesn’t exist or are subsumed by it, mirroring its frantic language. Fuad finds a synthesis that is neither an evasion nor a surrender. As she writes, “When the self finally appears, don’t turn the self away.” With its inventive, precise language, Portal makes clarity from noise.

—David Schurman Wallace

Most twelve-year-olds online today have the kind of intuition for the infinite plasticity of word and image that you used to have to study semiotics to acquire. This is why we’re living through a Cambrian explosion of linguistic creativity; it’s also why Twitter eventually makes you feel like words are meaningless, and like you are dead or “deconstructed.” What makes Honor Levy the voice of a generation is her ability to take all those floating signifiers and dead metaphors, all these junk-bits of content rendered inert by their repetition—on Reddit, on Tumblr, in Shakespeare—and give them new life; in other words, meaning. And she makes it look easy! At their best, Levy’s sentences hopscotch through intricate sequences of signs with perfect control and infectious glee; all you want to do is sit back and watch them play. My favorite piece in her new collection My First Book is an otherwise traditional short story composed almost entirely of cultural references, and a virtuosic example of this sense for rhythm and quotation: “She’d stare up at him with her shining anime, no her shining animal eyes, her real eyes, realize real lies. Wondering what he was thinking. He’d stare into them and then he’d sit beside her, very close, take a breath and say, Damn Bitch, You Live Like This? like Max to Roxanne from A Goofy Movie (1995) from the meme (2016). They would smile. There would be butterflies.”

The story being told here is a tale as old as time: boy meets girl—except online. The simplicity of this conceit belies the beauty and intelligence of its execution. Like Instagram, and like one of the oldest scraps of internet syntax I personally remember, it’s so meta: “Love Story” shows us how the love story is itself a meme—the original one. “Odysseus and Penelope, Eloise and Abelard, Adam and Eve, Bella and Edward,” as Levy’s story goes. Their love is why we’re here, and their stories are why we fall in love. And Levy’s unnamed Zoomer Romeo and Juliet are acutely aware of this: their status as characters and images, as memes and as (thanks to xenoestrogens, diminishingly viable) genes, and the melancholy this can produce. Deep in her “Ophelia era,” she has to remind herself of her actual existence: “That is my body on the screen there. This is my body on the bed here.” Sometimes, when you know you’re just a vessel, you feel really empty. As the Wikipedia page for Metameme states, “It has been proposed that the degree of consciousness a society has about the very memes that form it is correlated with how evolved that society is,” and sometimes, knowing you’re at the brain-expanding final stage of humanity isn’t so fun. A “Withered Wojak,” he feels “depopulation, doom, the sun setting for the last time ever, a great ugliness, the end of history flashing before his eyes.” (These low points come after a poorly received nude.) A less courageous and more cynical writer, perhaps someone working on Euphoria, might have left the romance at that: poor alienated fucked-up Zoomers. But Levy knows we’re so lucky to see “all of the ends and the beginnings beginning and ending and beginning and ending and beginning and ending infinitely.” And our generation is lucky to have a voice that gives us a happy ending, or, at least, a happy way to end. <3

—Olivia Kan-Sperling, assistant editor

May 16, 2024

The Poetry of Fact: On Alec Wilkinson’s Moonshine

Abandoned shack in rural North Carolina. Photograph by Carol M. Highsmith, via Wikimedia Commons. Public domain.

The quantity and quality of consternation caused me by the publication of Alec Wilkinson’s Moonshine in 1985 is difficult to articulate. This utterance should prove probative. If we are in a foreword, an afterword, or perhaps ideally a middleword, we will shortly be in a model of muddle at the very end of the clarity spectrum away from Moonshine itself, with its amber lucidity, as someone said of the prose of someone, sometime, maybe of Beckett, maybe of Virgil, who knows, throw it into the muddle. The consternation caused me by this book is even starker next to the delight of reading the book itself before the personal accidents of my response are figured in. I will essay to detail those accidents, but I would like to first say something about the method of the writing.

Alec Wilkinson is one of two literary grandsons of Joseph Mitchell, the grandfather of the poetry of fact. “The poetry of fact” is a phrase I momentarily fancied I coined, but the second literary grandson of Joseph Mitchell, Ian Frazier, corrected me, and I have assented to his claim that he coined the phrase. One’s vanities are silly and dangerous. It is a vanity to think to say there are but two grandsons of Joseph Mitchell as well. There are doubtless dozens and, of course, granddaughters, too; what I mean is that Alec Wilkinson and Ian Frazier are the grandsons with whom I am most familiar, and most fond, and so it is convenient to sloppily say they are it.

What is the poetry of fact? Good question. Since I am not the coiner of the term and, at best, a dilettante in its practice, I may be excused, I hope, if my answer is wanting, but I vow to do my best. I, alas, have brought it up. When the justice of the peace who conducted my marriage, Judge Leonard Hentz of Sealy, Texas, asked if anyone objected to the imminent union, he looked up and said, of our sole witness, “Well, hell, he’s the only one here, and y’all brought him, so let’s get on with it.”

The poetry of fact is the ordering for power of empirical facts, historical facts, narrative elements, objects, dialogues, clauses, phrases, words—it is the construction of catalogues of things large or small into arrays of power. The power of the utterance is the point. The preferred mode of delivery is the declarative sentence, simple or compound, without subordination or dependent clauses—without what Mr. Frazier has called “riders.” Power in this instance—in any writing, really—is to be understood as a function of where things are placed. The end of a series or sequence or catalogue or paragraph or chapter or essay or book is the position of what we will call primary thrust. It is what will linger in the brain uppermost because it is lattermost. The beginning of an array, large or small, is the position of secondary thrust: the “first impression” that gets lost but never quite recedes. The middle of an array is the tertiary thrust—the middle gets lost in the middle, ordinarily. This is the middle’s job. Games can be played with these positions of emphasis. A sockdolager, to employ Twain, can be buried in the middle where, because it is a sockdolager, it is not exactly buried and may constitute a surprise. The emphatic middle, let us call it, installs an irony, raises an eyebrow whether anyone realizes it or not. An “unemphatic” end also installs an eyebrow. Strunk and White’s The Elements of Style is onto but the very tip of this iceberg with its Elementary Principles of Composition #18: “Place the emphatic words of a sentence at the end.” Were it “The words at the end of a sentence are emphatic,” they’d have been closer to the nuanced complexity of the poetry of fact, but let’s move on.

The poetry of fact requires interesting facts. The best-case scenario for interesting facts is an interesting person doing interesting things. Once such a person is located, if it can be the case that he or she can speak well about the doing, we are in a second power—colorful deeds performed by a colorful person, colorful squared.

The poetry of fact does not permit of the coy. By coy, I mean overt withholding that arrests the reader’s neutral expectations. The reader is not compelled to say “Wait . . .” or allowed to ask “And?” The reader certainly need never ask “What?” The reader is not working to follow. The reader is not tightroping in grammatical suspensions—or worse, logical suspensions—for the logic or the thought or the drift to evolve. The stuff is coming easily and naturally (seeming). The reader sees this, this, and this. The reader does not see if that, this, or while this, that. Withholding of a fact to achieve “suspense” is perhaps the cardinal sin. The stuff must come timely in a straight (seeming) line, and if done right, it is powerful largely because there is no frustration or difficulty of perception. The root scheme is what Hemingway was after. He wanted to strip writing of rhetoric and “thinking.” It is a pointillist technique that, as it goes, assembles a large, strong, obvious, digestible portrait. It is a pointillist technique that, as it goes, assembles a digestible, strong, obvious, large portrait. It is a pointillist technique that as it goes assembles a strong, digestible, large, obvious portrait. It is a pointillist technique that as it goes assembles a digestible, strong, obvious, large portrait. As it goes, it assembles a strong, large, digestible, obvious portrait via a pointillist technique. A strong, large, digestible, obvious portrait via a pointillist technique is assembled as it goes. Quod erat demonstrandum, and not well.

The poetry of fact does not permit opinion or comment or instruction toward inferences to be made by the reader. Inference is a function solely of the manipulations of the facts and the facts themselves.

Let us see now how this actually works when it is not being cartoonishly parodied. Here is the opening of Mr. Wilkinson’s Moonshine:

For more than thirty years Garland Bunting has been engaged in capturing and prosecuting men and women in North Carolina who make and sell liquor illegally. To do this he has driven taxis, delivered sermons, peddled fish, buck danced, worked carnivals as a barker, operated bulldozers, loaded carriages and hauled logs at sawmills, feigned drunkenness, and pretended to be an idiot. In the minds of many people he is the most successful revenue agent in the history of a state that has always been enormously productive of moonshine.

Three declarative sentences, each with an orienting beginning, a buried middle, and a hard, elevated end. The ordering of the sentences themselves demonstrates this secondary, tertiary, and primary emphasis. (This idée fixe of mine, I assure you, is about to bother us no more. I will break down this paragraph now and as a reward for your indulgence release us immediately to the book itself. A good introduction to a good book should release us in the first sentence—certainly a bad one should.)

These three sentences, remembered for their final thrusts alone, a hazy kind of natural default recall, announce together that liquor is sold illegally, that this selling is policed by a man who has pretended to be an idiot doing it, and that our idiot-seeming cop may be the best there is “in a state that has always been enormously productive of moonshine.” This is a curious phrase, asked to bear the weight of the entire opening paragraph of the book. “Enormously productive” is a fact, but it is rendered in a hue some distance away, on the palette of diction, from “moonshine.” Why Mr. Wilkinson ends his paragraph opening the book Moonshine with “moonshine” is comparatively easy to explain next to why his penult is “enormously productive.” Moonshine is funky and nefarious even in antonym, as in “Put it where the moon don’t shine.” What I mean by shift in hue with “enormously productive” might more commonly be called a shift in register; to stay in register with “moonshine,” we might expect “in a state that has always made a lot of moonshine.” Why has Mr. Wilkinson played with the paint, or the diction, like this? No one in this market would be expected to say, “I am in a state that has always been enormously productive of moonshine.” He would say, “We make a lot of moonshine here.” “North Carolina is full of moonshine and bootleggers.” “Yes, Hyram, we are enormously productive of moonshine.” “Why are you talking like a dick, Cecil?” “Because I am a poet. Do you want to fight?” I have taken us down what parlance today demands we call “a rabbit hole,” and I did not mean to. The difference in register constitutes a joke, a small one that is funny, as jokes should be, but that also in this instance says something about what we will call the code, which may be called instruction on how to read a book. The code here says, “This little play in hue of tone or in register of diction means that I am in charge here and aware of what I am doing and if I want to sound for a second a tad pedantic with an arch sound that makes of moonshine an even more heavy-landing word than it is, I will.” Wilkinson announces: Despite its flat-looking declaratory simplicity of affect, this is a thoughtful and intimately controlled book you hold, Reader. Watch it.

Let’s get out of the rabbit hole.

For more than thirty years Garland Bunting has been engaged in capturing and prosecuting men and women in North Carolina who make and sell liquor illegally.

Five words into the book, the odd and weirdly theatrical name Garland Bunting establishes the subject of the book up front (if it had not been coined better by my betters, I could have called the poetry of fact the art of up front), and five more words in, buried in the middle of this sentence, we see that Mr. Bunting captures and prosecutes men and women. Capturing men and women is an ironically emphatic element to be buried in a sentence; note that Mr. Wilkinson cannot responsibly say “capturing” without addending “prosecuting,” or we’d be misled into thinking Mr. Bunting up to illicit rather than licit engaging. Facts are not left out to achieve cheap effect. We have it established that we have a subject who does interesting things; all we need for the cherry-on-sundae ignition is Mr. Bunting’s capacity to talk well about what he does. The first thing we see him say is that he is shaped like a sweet potato: “small at both ends and big in the middle. It’s hard to keep pants up on a thing like that.” A self-deprecating fellow who captures people and can talk. Mr. Wilkinson discovered him in a newspaper article and called him up and asked if he could come down for a week to write about him. Mr. Bunting said, “A couple days maybe, but nothing like no week.”

The second sentence of the book is an orthodox catalogue, which is, really, the catalogue, all that is meant by the lofty “poetry of fact.” Good catalogue. Good catalogue is the correct elements allowed to coil for power. The coiling requires patience. The secondary/tertiary/primary infrastructure, to get Marxian about it, must be back-burnered in the brain while things logically and visually and sonically adjust themselves, like a snake settling in a box. When the snake is comfortable and on guard, draw a picture of him.

To do this he has driven taxis, delivered sermons, peddled fish, buck danced, worked carnivals as a barker, operated bulldozers, loaded carriages and hauled logs at sawmills, feigned drunkenness, and pretended to be an idiot.

Note, beyond the traditional placing of our sockdolager at the end—the pretending to be an idiot—the two longer phrases in the middle of the catalogue, longer and perhaps less visually immediate:

worked carnivals as a barker . . . loaded carriages and hauled logs at sawmills . . .

And note the separating of these arguably more diffuse elements with the strong, clean “operated bulldozers”—perhaps the literal center of this catalogue; the truest and lostest middle of it is a policeman on a bulldozer in pursuit, somehow, of a bootlegger. On a bulldozer! In a phrase trying to be concealed! It’s a world—this book—of paradox, structurally and otherwise. All that this inessential bloviation of comment I have expended at it does is demonstrate the fine control of quiet paradox Mr. Wilkinson writes with.

I have committed all this gobbledy trying to stop short of the gook in gobbledygook. It was hoped that you as reader would say to yourself at some point, You’d better cease this nonsense and get to the book. If you did, good. If not, we now approach with relief an end.

The publication of Moonshine put me in a world of consternation; this delightful tour de force hurt me because at the moment of its heaving onto the literary horizon in 1985, I was at work on a subject at the other end of Mr. Wilkinson’s and Mr. Bunting’s spectrum. I was at work on a subject who in nearly every way, legally and anthropologically, was in opposition to Mr. Bunting, and who in fact could have been one of Mr. Bunting’s targeted perps. Shortly after publication of Moonshine, my subject was busted for distilling liquor and growing marijuana on his swamp property in Red Springs, North Carolina, 168 miles away from Mr. Bunting’s Scotland Neck, and I do not know for a fact that Mr. Bunting did not do the busting but believe that my subject was taken down with lesser and more local force than Mr. Bunting represents.

Mr. Wilkinson had done with Mr. Bunting what I could not do with my subject. My subject did things as interesting as Mr. Bunting did, things the least interesting of which was the bootlegging and pot growing, and he could talk well about them. He was a native of the Lumbee Tribe with a degree from Brigham Young, by way of Vietnam and the GI Bill, and a Mormon wife and a kennel of dogs that generated the only living ever made by selling pit dogs and a career in Peeping Tomism, and he would, once the local whiskey still and pot charges were adjudicated and the Mormon wife had abdicated and the kennel had bankrupted, go on to do three years federal time for large-scale pot running in rental cars from the border of Mexico into the poor, low, murderous hills of Robeson County, North Carolina. “The government dudn’t care about the drugs,” he told me. “They want the money.” (It is not by whim that Mr. Bunting is called a revenue agent and not a liquor agent.) He had flown with suitcases containing halves of millions of dollars in cash to Switzerland, more at one point than one bank could, or would, accept. He would go down the street with what one bank did not accept to another bank that would. One day he said, “I’mone drop a bomb on you.” I said, “Okay.” He said, “Nuclear now.” I said, “Okay.” “Nuclear bomb now.” I said, “Okay, drop it.” He said, “Bisexual.” I said, “Who? You or—?” He said, “Me.” I said, “What does that mean?” He said, “What that means, buddyro, is that in the last eighteen years I have sucked six thousand dicks.”

I had this nuclear bomb, a huge sexual topography to explore,* and was discovering as we went the troubled history of the Lumbee to give it all some scope—and I did not write the book.

Because what I failed to say in all the maundering above, all the this this this and not if this, then this tertiary schmertiary, all the catalogic explications and the sly pedantic, is: This kind of writing is HARD. The gathering of fact alone will kill you. The coiling of the fact will then exhaust the dead. I did not write my book.

I lazed out on my book about my colorful cheerful bootlegging fighting-dog-breeding soldier-seducing Lumbee raconteur. Mr. Wilkinson did not laze out on his book, on his colorful cheerful potato-shaped policeman after my man. I thank him for his industry.

*When I later attempted to verify the six thousand dicks, my man said, “What?” I thought he would retract. He said, “I want to revise that count.” I said okay. He took a minute in a chair looking at the ceiling and said, “One thousand.” That is when I started really paying attention.

From the introduction to the new edition of Alec Wilkinson’s Moonshine: A Life in Pursuit of White Liquor, out from Godine Nonpareil in June .

Padgett Powell is the author of six novels, including Edisto, a National Book Awards finalist, and You & Me. His other books include three short-story collections and the essay collection, Indigo: Arm Wrestling, Snake Saving, and Some Things in Between. His awards include a Whiting Award in Fiction, the James Tait Black Memorial Prize, and the Mary Hobson Prize for Distinguished Achievement in Arts and Letters. He has been a professor of writing at the University of Florida since 1984.

May 15, 2024

Scrabble, Anonymous

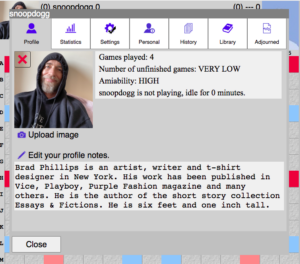

Images courtesy of Brad Phillips.

This morning, before breakfast, I played nineteen games of Scrabble on my phone. I won thirteen. It took less than an hour. Over the past twenty-five years, I’ve played Scrabble every day, predominantly on ISC.RO, a website hosted in Romania that allows for games that are no longer than three minutes. On my phone, I use the Scrabble app and play a bot set to “expert.” I had meant to play only two or three games today, but as has been happening since 1999, I found that impossible.

These facts embarrass me, and I’m concerned I might appear to be bragging, announcing that I can finish a Scrabble game against a highly skilled bot in less time than it takes to brush one’s teeth. I’m not bragging. I’m confessing to being addicted to an ostensible word game that occupies more space in my brain than I’d prefer. Addicts are necessarily experts when it comes to the things that enslave them. No sommelier or “mixologist” can testify to any aspect of an alcoholic beverage with more expertise than a run-of-the-mill drunk playing keno in a dive bar.

Run-of-the-mill drunk in a dive bar. I was one once. I’d wake up determined to have just two or three drinks, then have many, many more than two or three. As with playing Scrabble, doing otherwise felt impossible. In Alcoholics Anonymous, we’re told that it’s common to substitute one addiction for another. Surely, I tell myself, this new unmanageability is preferable to the old one. It’s possible I’m right. It’s also possible I’m wrong.

***

Scrabble is a family favorite game played on a board composed of two hundred and twenty-five squares. There are one hundred tiles, each printed with a letter (save the two blanks) that is assigned a numerical value. The most common letters (A, E, R) are worth one point. The most uncommon (Q, Z) are worth ten. Players start—and until the end remain—with seven letters that they use to create words by building on previously played words, hoping to place one or more of their tiles on any of the colored squares, thereby multiplying their score.

This morning—before those nineteen games, the instant I woke up—I realized that the letters in CAUTIONED can be rearranged to spell EDUCATION. This seemed vastly better than waking up with no memory of the previous night, worried about what I may have done or said. Nonetheless, the thinking is obsessive and constant. The unwilling, unconscious anagramming of words is the primary side effect of a life devoted to Scrabble. This is ultimately what the game is about: memorizing words with no concern for their meaning.

If you play Scrabble seriously, no question from an opponent is more tedious than “What does that word mean?” Despite being a game centered on words, Scrabble isn’t about words; it’s about strategy, probability, and memorization. Misunderstanding this fact about the game leads people to unpleasant realizations.

For example, in August 2023, Isaac Aronow wrote about Scrabble for the New York Times. He’d seen a nine-minute video posted by The New Yorker titled “Professional Scrabble Players Replay Their Greatest Moves” and, shocked that there were professional Scrabble players, became determined to get good at the game. Aronow stated that because of his job as a writer and an editor, words were “important” to him, and he believed this might be helpful in Scrabble. He then outlined the humiliation he experienced playing online and admitted to having been full of hubris. Aronow was not good and didn’t improve.

I am also a writer and occasionally an editor. I know that this has no effect on my Scrabble game. If anything, the inverse is true: having learned the word bezique from playing Scrabble, I once used it in a short story about a private detective working on a case in Lisbon.

When playing Scrabble, language explodes then settles quietly on your rack, having been decommissioned. Each letter is a weapon only in the service of point accumulation and can no longer convey meaning by joining with its fellow letters. A word on a Scrabble board is a mathematical fact, not a unit of expression.

Last Thursday I visited the New York Scrabble Club, affiliated with the North American Scrabble Players Association (NASPA), of which I am a member. It was my first visit. I joined the club in May 2023. For eleven months, I planned to go, then did not go. Unlike Isaac Aronow, I was not full of hubris. I was terrified.

Life online is mostly devoid of the fear that can permeate life lived offline. Thus trolls, and QAnon. On ISC.RO I’ve played famed figures in the Scrabble world without having to meet their gaze. Online I’ve often felt confident, even arrogant, about my ability to play high-scoring words in very little time. Among the members of the New York Scrabble Club, everyone can do what I do, and most, I imagined, could do much better than me. Realizing that I’d be shaking hands with them, saying “good luck” and “good game,” made me feel as vulnerable as I felt the first time I walked into a church basement for an AA meeting. But, I realized, there was something else that made me nervous.

I felt like I was going to do something wrong, something addicty, something I hadn’t done in a very long time.

***

The eleventh tradition of Alcoholics Anonymous states, “Our public relations policy is based on attraction rather than promotion; we need always maintain personal anonymity at the level of press, radio and films.”

Since this is the literal press, I apologize to friends for breaking with tradition.

The tradition is meant to safeguard the program, not the individual. An alcoholic is free to tell people they have a drinking problem. What they’re not supposed to do is tell those people that AA relieved them of their problem, because if they relapse, someone enslaved to alcohol but curious about the program may let that be the reason they don’t attempt it themselves.

I had meant for this to be an account of my experience meeting and playing against Scrabble players I’ve admired for decades. Using the “observe” function on ISC.RO, I have watched some of these players play in real time. Along with a dozen other people seeking to improve their skills, I have looked on as the world’s highest-ranked players lay down bingo (a word using all seven letters) after bingo, marveling at their ability to anagram the obscurest of words from vowel-heavy racks. I’ve spent untold hours analyzing downloaded boards played by world champions, and it’s worked: I’m a much better Scrabble player because of it, to the extent that I can no longer play against people who aren’t as obsessed with the game as I am.

But despite having played Scrabble for exactly half my life, despite having a fairly admirable win-to-loss ratio and having had friends and family tell me I’m good, I felt certain that my first experience at the New York Scrabble Club would be an ignominious one, soundtracked with mocking laughter from the regulars, whom I was both excited and scared to meet. As is almost always the case when I imagine the future, what happened was the opposite of what I’d expected. And because the environment felt something like sacred, because I dread the idea of anyone from last Thursday reading this and feeling exposed or viewing me as a tourist and an interloper, I’m employing a modified version of Alcoholics Anonymous’s eleventh tradition. The only name named is my own.

***

People attempting to recover from unhealthy obsessions unanimously report a tendency to overthink to the point of debility. Riding the subway uptown to the Scrabble club, I considered the ways I’d replaced one addiction with another.

I compared (played off the C, a bingo with OMPARED) and contrasted (played off CON, a bingo with TRASTED).

When addicted (played off the I, a bingo with ADDCTED) to a substance, thoughts of the substance become the background and foreground of your mindscape. As was the case with alcohol, my first and last thoughts of the day are usually Scrabble related (RELATED anagrams: ALTERED, REDEALT, ALERTED, TREADLE). These thoughts do not feel self-generated. Instead (DETAINS, STAINED, SAINTED …) I feel like I’m being harassed by my mind, forced to think about something I’d rather not be thinking about.

Addiction interrupts productivity. An alcoholic in the office takes long lunch breaks. Editing this essay today, on six different occasions I’ve stopped to open ISC.RO. Each time, I’ve played more games than I’d intended. As a result, my editor is still waiting.

By the time I exited the subway, I’d disabused myself of the notion that I am a “normal” Scrabble player. What this says about my status as someone in recovery from addiction, I don’t know.

***

That Thursday night, J—— S——, chairman of the New York Scrabble Club (also the 1997 World, 2002 National, and 2018 North American champion) gave me a copy of the helpful New Player Information handout he’d created. My heart was still racing from having met someone whose games I’d voyeuristically observed countless times when I read: “Don’t play scared. Don’t worry how good your opponent is …”

People like me must show up from time to time, sweating. I scanned the room. At fifty, I was close to being the youngest person in attendance, a drastic change from my usual social life, which mostly, sometimes drearily, involves art openings. There was an assortment of cookies on a table, two canisters of coffee, and maybe twenty-five people in attendance. I would play four games that night, each with a twenty-two-minute clock, and I was supposed to be matched against people of my skill level. But how would they know my skill level? I considered leaving before things began.

As I waited for the matchups for the first game to be announced, I looked at the competition. I couldn’t guess what these people did for a living. They couldn’t guess what I did, and most beautifully, they wouldn’t care. The same phenomenon exists in twelve-step meetings. You hear the same people share about their lives week after week and don’t know if they’re cardiac surgeons, state senators, or baristas. A common obsession is a powerful unifier, one that renders all other biographical information meaningless.

I took another look at the handout I’d been given. It advised me that the best letters to have on my rack were those in the word CANISTER. I’d learned something new without having yet taken off my jacket. The C, I’d always thought, apparently mistakenly, was a letter to avoid. With the other letters in CANISTER, I knew that I could play the following bingos:

RETAINS

STAINER

ANESTRI

STEARIN

ANTSIER

NASTIER

RETINAS

RETSINA

RATINES

A first for me was that this time everyone else in the room also knew about these words. These bingos were common, even pedestrian. Now aware that J—— S—— praised the C, I instantly saw three new bingos I wouldn’t ordinarily have noticed:

CREATINS

SCANTIER

CARNITES

I was a newcomer. A rookie. Unaware of the value of the letter C. My heart sunk.

Then I heard my name and instantly felt nauseous.

I swallowed hard and looked at my opponent, who smiled at me. There were maybe a dozen tables in the club, each with a plastic-coated, helpfully rotating Scrabble board, a bag of letters, and a chess clock. Growing up, we kept our Scrabble letters in a purple, faux-velvet Crown Royal bag. I saw three Crown Royal bags that night and felt that they knew me. They were me. Stalling for time, I got a coffee from the snack table and filled a paper bowl with Smarties and pretzels. Outside it was 2024, but inside it could easily still have been 1987, even 1975.

I approached my table.

A—— was markedly friendly and made banter, which I later learned is strongly discouraged. There should be, the New Player handout said, zero conversation unrelated to word challenges and scorekeeping during games. I suspected I’d been matched against A—— because I was new, because I was scared, and because I didn’t know the etiquette. A—— made me feel welcome. After he played ZEBU—and while he explained to me the proper technique for exchanging letters—I played ZINGIEST (played off the Z, a bingo with INGIEST). With twelve and a half minutes left on my clock, I was shocked to find I’d won my first game, 353–337. A—— congratulated me, showed me where the pencil sharpener was, and went to refill his coffee.

I went to the bathroom, splashed cold water on my face, then heard the matchups for the second game announced. Though I lost my second game (366–409)—to J——, a guy in his sixties with a welcoming, warm expression—experiencing defeat and having it be free of laughter or taunting from observers got me to relax. J—— had commented that I played fast and asked which tournaments I’d been in. I told him none, that this was my first time playing anyone I wasn’t in love with or related to. I looked for a sign that he was impressed but didn’t find one.

My next opponent, L——, told me, “This city isn’t what it used to be.” I agreed, despite not having lived in New York when it was what it no longer is. I won 368–312 and in my final game beat N——, 358–309.

I suddenly felt exhausted. I’d been far more anxious than I had realized and was suffering the aftermath of a flood of stress hormones. I looked around. People were engrossed in their fourth and final games, and those who’d finished theirs were watching. Two elderly men were animatedly consulting a dog-eared copy of a NASPA dictionary. A woman was rounding up pencils to be returned to the cabinet. As I walked toward the elevator, the oldest person there, a woman, asked if I’d be coming back.

“I heard you’re good,” she said, with the nicest smile.

I told her I would be back and that I’d had a great time. I felt embarrassed by how sincere I sounded, how much it meant to me to feel accepted.

While I was waiting for the subway to return home, three people I’d seen at the club approached me and introduced themselves. Riding the F train downtown, we looked at flash cards on one of their phones. Jumbles of vowels and consonants that could be anagrammed into words I’d never seen before. Ordinarily this kind of behavior—forgoing conversation to focus on an obsession—has felt unhealthy to me. Somehow, doing it with other people took the stain away, made it feel fun instead of abject. Back home, I compared and contrasted again. Sure, maybe it’s obsessive, and, yes, it looks and feels like addiction, but it’s just words and numbers and points, and no one steals from their mom or cheats on their partner; no one stabs anyone or blows their kid’s tuition. Substitution isn’t always a bad thing. Who says we need to live in perfect equipoise twenty-four hours a day, aggressively present, free of any and all distractions.

DISTRACTIONS, played off TRACT, a bingo with DISIONS.

May 14, 2024

Hot Pants at the Sodomy Disco

“Pedro Lemebel, one of the most important queer writers of twentieth-century Latin America,” writes Gwendolyn Harper, his translator, was “a protean figure: a performance artist, radio host, and newspaper columnist, a tireless activist whose life spanned some of Chile’s most dramatic decades. But above all he was known for his furious, dazzling crónicas—short prose pieces that blend loose reportage with fictional and essayistic mode. … Many of them depict Chile’s AIDS crisis, which in 1984 began to spread through Santiago’s sexual underground, overlapping with the final years of the Pinochet dictatorship.” Over the next few weeks, the Review will be publishing several of these crónicas, newly translated by Harper, as part of a brief series. You can read the first installment, “Anacondas in the Park,” here.

On the edge of the Alameda, practically bumping up against the old Church of Saint Francis, the gay club flashes a fuchsia neon sign that sparks the sinful festivities. An invitation to go down the steps and enter the colorful furnace of music-fever sweating on the dance floor. The fairy parade descends the uneven staircase like goddesses of a Mapuche Olympus. High and mighty, their stride gliding right over the threadbare carpet. Magnificent and exacting as they adjust the safety pins in their freshly ironed pants. Practically queens, if not for the loose red stitches of a quickie fix. Practically stars, except for the fake jeans logo tattooed on one of the asscheeks.

Some are practically teenagers, in bright sportswear and Adidas sneakers, wrapped in springtime’s pastel colors, healthy glow on loan from a blush compact. Practically girls, if not for the creased faces and the frightful bags under their eyes. Giddy from rushing to get there, they show up tittering each night at the dance cathedral inside the basement of an old Santiago cinema, where you can still see the black-and-gold Etruscan friezes and Hellenic columns, where the stench of sweaty seat cushions hits hard once you finally get past the burly bouncer at the door. That’s where spongers circle, hovering around any gay man who might cough up their cover. We’ll figure it out inside, they croon into ears with little dangly earrings. But the gays know that, once inside, the most they’ll get is “… have we met?” because every taxi boy heads straight to the bar, where the grannies flaunt their piggy banks, rattling ice in a glass of imported whisky.

The bar at a gay club is a good place to meet someone—it’s the area with the best light for spotting the witch who never sees the sun, always underground like the roots of an AIDS-ridden philodendron. The same one who cried sapphire tears, forgiving herself for all her dirty tricks, the spitting in drinks, the broken condoms, the falsified positive test results that aided and abetted a few girls’ suicides. Her schemes for infecting half of Santiago because she didn’t want to die alone. It’s that I have so many friends, she said. The same Miss Perverse who’s back again, more alive than ever, laughing luciferously with a drink in hand.

Here’s where they pour the gin and tonics, pisco sours, pisco sores, pisco colas, and loca-colas singing along to “Desesperada” by our darling Marta Sánchez, which always makes the disco babes go crazy. The girls in shorts who come up to the bar breathlessly asking for water with ice, elbowing the office worker who’s still wearing his tie and who keeps eyeing the door in case someone from his work shows up.

The club bar is for trading glances and putting one’s erotic goods on display in certain preferred brands of clothing—the ones that can be found at a thrift store, anyway. A Levi’s patch guarantees a luxury booty—a pair of cowboy glutes bursting out of its seams, fibrous in the tight motion of resting both cheeks against the bar counter. Practically masculine, if not for all the ironing and that soft detergent smell. If not for the hand-stitching inside the seams. Way too clean, like trying to make up for something, justifying their homosexuality in the powder-puff aroma that frames their movements. If not for those dense clouds of pansy perfume: Addiction by Paloma Picasso, Obsession for Men by Calvin Klein, Orpheus Rose by Paco Colibrí. If not for those aromatic names emanating from their aerobic stupor, they’d pass as extremely friendly heterosexual men, for sloshed little machos drooling on their buddies. If not for that “Ay, honey, I warned you,” “Ay, Chela, you deserved it, you witch,” “Ay, if only,” “Ay, don’t you think?” If not for the “Ay” that crowns or decapitates every sentence, they’d blend right in with the hordes at any old discotheque, dressed in denim and a white shirt with that little crocodile gnawing at the nipple.

Though gay discos have existed in Chile since the seventies, and only in the eighties institutionalized as a backdrop for the gay cause, mass-producing the Travolta model for men and men only. It’s possible that these homo-temples of dance have united the gay ghetto with far more success than militant politics, imposing certain lifestyles and a philosophy of macho camouflage that uses fashion to dress the full spectrum of local homosexualities in a single uniform. The folkloric fairies and freaks have survived only as little baubles hanging on homo culture, under the delusion of being a pharaohess fluttering in the dance club’s mirrors. A last dance that squeezes last sighs from a loca overshadowed by AIDS. The hot coal of a loca show that the gay market consumes in its business of sweaty muscles. Potentially only that spark, that humor, that argot makes for a politicizable distance. A wildflower petal drifting forgotten on the dance floor when the sunrise cuts off the music and their laughter, in a pale return to the city’s routines, blurs with the traffic on the Alameda.

This crónica will appear in A Last Supper of Queer Apostles by Pedro Lemebel, which will be published later this month by Penguin Classics, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group. Translated by Gwendolyn Harper.

May 13, 2024

Story Time

“Un Joyeux Festin.” Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons, licensed under CCO 4.0.

There was a time in my life when I went to many formal dinner parties. Were they parties, exactly? They were dinners orchestrated to celebrate something—a book, or an exhibition—or to raise money. Older and better-off friends often invited us to these events. I was young and newly married to my second husband. We had three and then four children, and pennies slipped through our fingers. For winter I owned a black dress with a keyhole neckline, and for spring a thrift-shop chiffon skirt and an embroidered tunic the color of spilled tea. I imagine our friends thought we would enliven the table.

As I said, we went to many of these dinners, but one evening put a stop to it. It must have been springtime, as I was wearing my skirt and tunic. My husband wore his tuxedo. Before we left the apartment there was the usual brouhaha about his bow tie. In the movie version of Peter Pan, starring Mary Martin, Mr. Darling (Cyril Ritchard, who in an thrill-inducing about-face, also plays Captain Hook) cannot tie his bow tie properly and the scene devolves: he must tie his bow; he must go to this dinner; if he does not, he will lose his job, and the family will be in the poorhouse! He practices by tying it around a bedpost, but, after all, the bedpost can’t go to the party! My children had watched this movie perhaps fifty times, and whenever we went out to these dinner parties they would circle their father as he tried to tie his bow tie, chanting, To the poorhouse, to the poorhouse! As usual, in this grim ambience, we left them to their very tall babysitter, Ann, a Barnard student who looked like an elongated Alice; in the afternoons, she often took them across the park to the Met to see the mummies.

The dinner was at a converted warehouse in Tribeca, a vast high-ceilinged room swathed with gray silk; the effect was a tent of fog. Large vases on each table were covered with moss—from them leapt silver branches entwined with fairy lights. At each place, a tiny silver vase held two or three flustered pink anemones. The party was to celebrate the installation of a huge winged metal sculpture that commemorated—I can’t recall. There were drinks, and hors d’oeuvres on trays. As usual, I hadn’t had time to eat during the day and ate too many of these too fast. I had also turned my ankle on a cobblestone when we arrived, so stood on one foot, regretting my stiletto heels. Stanley Kubrick’s last film, Eyes Wide Shut, had just opened, and the dim room buzzed with conversation: “And what did you think of Mouth Wide Open?” I heard one woman say to another, her diamond bracelets snatching the light.

I found my place card. The seat to my left was empty. It was to remain empty all evening, but the chair, with its ghostly inhabitant did not then fill me with a sense of foreboding, though it meant I would have to talk to the person on my right, exclusively. It transpired that my dinner companion was a man in his mid-eighties. He introduced himself. We established that we were both friends of so-and-so. He was immediately recognizable to me, even then, as a man who had lived his life adjacent to power. His evening wear was immaculate; he wore a forest-green brocade bow tie. He preferred the country to the city, he told me. It was wonderful to muck around in the garden. Recently, a friend had said to me that if she heard the phrase country house one more time she would scream. I thought of that. Which country? I asked. He had a place in Connecticut. His wife—was her name Patsy?—grew roses. Sad she couldn’t be here tonight, laid up with a cold. Prone to them. We agreed something was going around. Here on your own? he asked. I indicated my husband across the table, engaged in animated conversation. It was a large round table for ten people, and I could just make out his voice, as distant as a ship-to-shore radio. We moved on. Did I write, or paint, or what? he asked me. I admitted that I wrote for a magazine. Amazing what girls get up to, he said. His own daughter had gone to law school. How many daughters did he have? It turned out we both had three.

Off to the races. Fifteen minutes slid by. The first course, a cold soup, came and went. Never liked cold soup, he said, can’t see the point. In between the soup and the main course, the light dimmed. Slides of the huge metal sculpture with its lethal-looking wings glimmered on a huge screen. Applause. The wine was handed around for the third time, the tiny lights on the bare branches like embers. My companion leaned toward me. Did I like stories? I seemed, he said, very sympathetic. He wondered if people often said that to me. I had given up trying to catch my husband’s eye. It was too dim, and in any case he had his “I’m making a new friend” look on, which meant that later I would need to peel him out of his seat.

Tell me, I said. He leaned closer. When he began again, his voice had changed. He spoke more slowly, each word a glass bead. When I was a boy, he said, a boy away at school. He paused. In college, that is. My aunt and uncle had a place on Long Island. It was a big place, more of a farm, really. Big places, back then. Hedges, fences to be mended. This was in Easthampton. I’d come down to lend a hand. It was my father’s idea. Thought I needed to do something with myself. Could have been right. It wasn’t too bad really. I liked being outside, and there were parties at night. Swimming. Lots of drink, lots of young people around. I met Patsy at one of them. How nice, I said. He glanced down at my plate. Eat up, he said in his former voice. Then he returned to a whisper. Patsy, he said, not the point. I asked after the point. Never told her, he said. I looked inquiring. Not Patsy. When I was there, that summer, that July, he said, a terrible thing happened. I waited. One morning, I was taking the truck out from the hangar where my uncle kept the farm vehicles, and I backed up. You backed up? I asked. He nodded. He said, It was a Ford truck. It was a hot day. I waited. I backed up, he said, and there was a thud. He continued. There was a thud, and I stopped the truck and got out of the car. He paused. Then he said, In the road was a child. I had seen the child before. There was a cat that he liked to play with, a black-and-white cat, and I’d seen him playing with the cat the morning before. He was two years old, and he was the child of one of the farmworkers on the place. I said nothing. With the fingers of my left hand, I pleated and repleated my chiffon skirt. The child was dead, he said. I had hit him, and I had run him over. And then I drove off down the road, and I didn’t tell anyone what I had done.

I listened to this story with the rapt attention that was expected of me—as I had been brought up to pay attention, to be deferential to my elders, and to indulge the fantasy lives of men. This training had been a boon to me as a journalist. This particular evening, however, I stood up from my chair and walked around the table to my husband, and I said, in his ear, We have to go now. To his credit, he did not protest.

Later, removing his bow tie, he asked me, Did you believe him? For several months afterward, I spent a few hours every couple of weeks trying to find out whether a two-year-old child had been run over in Easthampton between 1930 and 1935, the span of years I calculated might be in play, but I found nothing. But it was the end of those parties, for me.

Cynthia Zarin’s most recent book is a novel, Inverno. Next Day: New and Selected Poems and a novel, Estate, are forthcoming from Knopf Doubleday and Farrar, Straus and Giroux, respectively. A longtime contributor to The New Yorker, she teaches at Yale.

May 10, 2024

The ABCs of Gardening

From An Encyclopedia of Gardening for Colored Children. Kara Walker.

A is for ABC book. An Encyclopedia of Gardening for Colored Children, a new book by Jamaica Kincaid and Kara Walker, is an alphabetical sequence of lavishly illustrated, crisp lyric essays that takes readers on a tour of gardening, past and present, and serves as a teaching tool for children to learn about flora while practicing their letters. But at its roots, An Encyclopedia is a postcolonial excavation of the tyrannical alphabetization that has formed America since its origins. As the historian Patricia Crain writes in The Story of A: From The New England Primer to The Scarlet Letter, her investigation of the alphabet’s chokehold on American letters, “The alphabet is the technology with which American culture has long spoken to its children and within which it has symbolically represented and formed them.” Teaching children how to use the alphabet might seem like a natural, lawful neutral activity: here are the building blocks that create our communication system. But alphabetization as the default mode for organizing subjectivity—“As easy as ABC”—is a recent, and surprisingly problematic, phenomenon.

B is for Bible. The New England Primer, the first reader designed for the American colonies and the foundational text for schoolchildren in the United States before 1790, presents the alphabet via Biblically themed and morally didactic rhyming couplets: “In Adam’s Fall / We sinned all,” the A ditty goes, and the letters march on a mostly tragic journey from there, with dour little images that illustrate each couplet. Today, ABC books do lots of things. Many use the genre to provide a parade of content: A is for activist; R is for Rolex. Alphabet books aimed at adult audiences often satirize the genre. The Cubies’ ABC, from 1913, skewers Futurist artists in alphabetical order, shooting them down in doggerel: “B is for Beauty as Brancusi views it. / (The Cubies all vow he and Braque take the Bun.) / First you seize all that’s plain to the eye, then you lose it; / Next you search for the Soul and proceed to abuse it. / (They tell me it’s easy and no end of fun.)” ABC books sometimes even undercut the well-trodden form itself, with a wink or some wishfulness. Michaël Escoffier’s Take Away the A: An Alphabeast of a Book! suggests an alternate universe for a world without each letter: “Without the D, Dice Are Ice” depicts dice clinking in drinking glasses. Kincaid and Walker’s Encyclopedia embraces all these modes, from instructive to subversive to lyric to sly. Here, A is for apple, but it’s also for “Apple and Adam, too,” and “also for Amaranth.” A gets three entries; S, T, U, and W each get two; the rest get one. The rule seems to be that there is no rule, bucking the alphabet’s insistence on pattern.

Colored in the new book’s title gives a jump scare. Segregation leaps to mind. But the chromatic anachronism colored is also a literal description of the book, with its densely saturated, Crayola-bright pages and Walker’s deft watercolors.

“D Is for Daffodil,” for example, shows the disturbing grip of the colonial imagination on Western culture and the way we think about flora and fauna. For centuries, children schooled in the British system, no matter where they lived, had to memorize William Wordsworth’s “I Wandered Lonely as a Cloud,” which features a rhapsody on a “host of golden daffodils” as a peak joy of everyday life—even though most subjects of the empire, as Kincaid observes, “were native to places where a daffodil would be unable to grow and so would never be seen by them.”

Entries in An Encyclopedia weave history and fantasy with pragmatic gardening instructions. Each page appears on a color-saturated sheet, rejecting the implicit notion of white as the default background for text, and Walker’s limpid watercolors gleam.

Familiar faces emerge while reading: the book cross-pollinates images and etymologies. Connections appear, if you’re looking out for them. “Orange” is Citrus sinensis because it originates in China; “tea,” botanically, is Camellia sinensis for its Chinese origins.

Gardening can be both a literal activity and an imaginative one. Take “M Is for Musa,” which, Kincaid explains, is the proper name for the banana (Musa × sapientum or paradisiaca). Kincaid keeps the writing practical, focusing on what a monocot is (a plant that emerges from its seed with one leaf), while Walker’s painting takes us to the imaginative: it’s legendary dancer Josephine Baker, shimmying in the famous banana skirt she wore in the Folies-Bergère revues in Paris.

How do Kincaid and Walker keep an ABC book appropriate for all ages? Keep the adults guessing (what kind of story will Kincaid reveal about the plant?); keep the children on track with rhythm and repetition; keep everyone captivated with word and visual games.

Illustrations help. “G Is for Guava” focuses on the guava’s deliciousness in three sentences, but Walker’s watercolor reveals a more sinister underbelly. A Black girl holds a cut guava to the skies while she’s standing on a box that says “For Export.” The white boy peering lasciviously under the Black child’s floating white dress suggests that the guava might not be the only item for export: slave narratives are always under the surface, even in the most innocent-seeming moments.

Jamaica Kincaid herself, in real life, is a master gardener—I highly recommend checking out @virtuouspomona, her flowers-only Instagram account, to drool over a ridge planted with seemingly endless daffodils, snaking like a long river over the rippling earth.

Lyric essays that grow from her gardening have become a specialty of hers over the past several decades.

My Garden (Book), for instance, is Kincaid’s 1999 collection of intertwined nonfiction sprung from her extensive garden at her home in Bennington, Vermont, which started as a tiny plot in the middle of her front lawn. The garden is both deeply personal and a site of postcolonial reclamation. Per Kincaid, “When it dawned on me that the garden I was making (and am still making and will always be making) resembled a map of the Caribbean . . . I only marveled at the way the garden is for me an exercise in memory, a way of remembering my own immediate past, a way of getting to a past that is my own (the Caribbean Sea) and the past as it is indirectly related to me (the conquest of Mexico and its surroundings).”

Naming each plant is a labor of love but also an act of violence.

Obsession with names is the B plot of An Encyclopedia, which both celebrates and interrogates the colloquial and Linnaean names we’ve thrust upon plants, and a recurring theme throughout Kincaid’s writing on gardens. In her 2020 essay “The Disturbances of the Garden,” Kincaid writes, “To name is to

Possess; possessing is the original violation bequeathed to Adam and his equal companion in creation, Eve, by their creator. It is their transgression in disregarding his command that leads him not only to cast them into the wilderness, the unknown, but also to cast out the other possession that he designed with great clarity and determination and purpose: the garden! For me, the story of the garden in Genesis is a way of understanding my garden obsession.”

Questions aren’t part of the traditional ABC-book pedagogy since, usually, children come to an alphabet book to learn how to read. But Kincaid introduces some interrogations. In “S Is for Solanaceae,” about nightshades that originated in South America yet have become indelibly implanted into European cuisine, Kincaid asks: “What is contemporary Irish history without the presence of the potato? What is Italian cuisine without the tomato?”

Reading An Encyclopedia feels like the literary equivalent of the internet admonishment “touch grass”: go outside, get off your screen, have a

Sensory experience. Or even a synesthetic one:

The toy behemoth Fisher-Price produced a wildly popular set of colored plastic magnetic toy letters in the late twentieth century: red A, orange B, etc. A study of grapheme-color synesthetes (people who map an individual printed letter with a consistent color) revealed that those who grew up with these letters had synesthetic alphabets that mapped onto the Fisher-Price colors.

Use this book at your own risk, then: you might not learn how to garden, but you’ll start asking yourself what is hidden in plain sight and noticing when the fruit that seems sweet reveals rot at the core and the roots go deeper than we could ever see from what they produce.

Vivid watercolors and plainspoken language—An Encyclopedia is for children—reinforce the book’s core message:

We celebrate the garden’s abundance, but we must unearth where it comes from and what it’s for.

Xanthosoma, or dasheen, is the first and only place where Kincaid’s “I” (“known to me, this author”) steps into the book, breaking the encyclopedia’s traditional fourth wall. She comes in as with a light aside.

Yet in her first-person moment, she is also at her most serious. The cod traditionally served with dasheen, Kincaid writes, has been overfished to the point of environmental crisis. Flora and fauna are fragile and fleeting.

Zen gardens promise to imitate the essence of nature and serve as meditative spaces, designed for human contemplation. An Encyclopedia of Gardening for Colored Children promises ongoing profusion and chaos, using the arbitrary linguistic hierarchy to reveal the troubled and growing, profligate and rotting turbulence that the garden tries to subsume.

Adrienne Raphel is the author of Thinking Inside the Box: Adventures with Crosswords and the Puzzling People Who Can’t Live Without Them, Our Dark Academia, and What Was It For.

May 9, 2024

Anacondas in the Park

Parque Forestal. Photograph by Arturo Rinaldi Villegas, via Wikimedia Commons. Licensed under CC0 BY-SA 3.0 Deed.

“Pedro Lemebel, one of the most important queer writers of twentieth-century Latin America,” writes Gwendolyn Harper, his translator, was “a protean figure: a performance artist, radio host, and newspaper columnist, a tireless activist whose life spanned some of Chile’s most dramatic decades. But above all he was known for his furious, dazzling crónicas—short prose pieces that blend loose reportage with fictional and essayistic mode … Many of them depict Chile’s AIDS crisis, which in 1984 began to spread through Santiago’s sexual underground, overlapping with the final years of the Pinochet dictatorship.” Over the next few weeks, the Review will be publishing several of these crónicas, newly translated by Harper, as part of a brief series.

And despite the man-made lightning that scrapes intimacy from the parks with its halogen spies, where municipal razor blades have shaved the grass’s chlorophyll into waves of plush green. Yards upon yards of verde que te quiero verde in Parque Forestal all straightened up, pretending to be some creole Versailles, like a scenic backdrop for democratic leisure. Or more like a terrarium, like Japanese landscaping, where even the weeds are subject to the bonsai salon’s military buzzcuts. Where security cameras the mayor dreamed up now dry up the saliva of a kiss in the bigoted chemistry of urban control. Cameras so they can romanticize a beautiful park painted in oils, with blond children on swing sets, their braids flying in the wind. Lights and lenses hidden by the flower in the senator’s buttonhole, so they can keep an eye on all the dementia drooling on the benches. Old-timers with watery blue eyes and poodle pooches cropped by the same hand that hacks away at the cypresses.

But even then, with all this surveillance, somewhere past the sunset turning bronze in the city smog. In the shadows that fall outside the diameter of grass recruited by the streetlamps. Barely touching the wet basting stitch of thicket, the top of a foot peeks out, then stiffens and sinks its nails into the dirt. A foot that’s lost its sneaker in the straddling of rushed sex, the public space paranoia. Extremities entwine, legs arching and dry paper lips that rasp, “Not so hard, that hurts, slowly now, oh, careful, someone’s coming.”