The Paris Review's Blog, page 34

March 22, 2024

A Well-Contained Life

Photographs courtesy of the author.

What can’t be contained? Not much. We are given the resources, mental or physical, to contain our emotions and our belongings. Failing to do so often registers as weakness.

The smallest container you can buy at the Container Store is a rectangular crystal-clear plastic box available in orange, purple, and green. It can contain one AA or two AAA batteries, half a handful of Tic Tacs, or a folded-up tissue. The largest container you can buy at the Container Store is a four-tiered metal shelving unit. It can contain other containers.

Containers mediate us and our stuff. They create boundaries and allow our items to exist multiple feet above the ground. Most spaces are divided by containers. These containers might then be divided by additional containers. Containers form a scaffold, or an architecture. They make walls scalable and underbeds reachable. They allow you to put something down and know where it is the next time you want to pick it up.

One of the best ways to understand containers is to imagine a world without them. We would have piles. Bracelets, creams, stick-shaped kitchen items, fruit. Small things would get lost under big ones. Or, an alternative: a line of items that snakes through an apartment or house, up and down stairs and spiraling into the center of the room. When you want to find something, you simply walk along the line of items, confronting each individual thing.

We use containers to solve the problem of stuff. At the Container Store, containers solve other problems, too—problems we didn’t know we had. A Parking Guide provides you with a mat on which to park. A RollDown Egg Dispenser rolls your eggs. A Stackable Sweater Drawer creates a sweater-only space for sweaters. A Cheese Keeper keeps your cheese, and a Small Cube Sleeve serves as a sleeve for your cube.

There are plenty of analogies to choose from when describing a body, but one rather insufficient one is a container for our organs, blood, souls. The problem with this analogy is that our bodies are more than just containers. We can’t untangle our bodily experience from the feeling of existing in the world. In this case, the container is not a neutral scaffold.

Is this true at the Container Store, too? Many containers certainly try to be as neutral as possible, made from clear, thin acrylic, or a neutral-tone rattan. They sell a promise: Once you use me to sort your trouser socks, you won’t even know I’m there. The Container Store refers to their products as “organizational solutions”—a way of dealing with something rather than a thing to deal with. The thing itself is little more than the solution it offers.

And then you come to the hampers and think, If the hamper was simply a solution to the problem of storing dirty laundry, why must I choose whether I want it in plastic, canvas, or bamboo? And then you spot the Small Scalloped Edge Faux Rattan Bin and think, What’s keeping me from buying the Small Scalloped Edge Faux Rattan Bin, even if I didn’t have anything to put in it? After spending a certain amount of time in the Container Store, the containers that are meant to organize, divide, and store look less like solutions and more like stuff. Following this line of thinking is a great way to leave empty-handed.

The Container Store isn’t safe for the problem-less and adequately organized. The Container Store is better suited for the overflowing, the misplaced, and those lacking sectioned parts. Most of us do have a problem that the Small Scalloped Edge Faux Rattan Bin could fix. Only the bravest would buy it, place it on the table, and wait for it to find the problem for itself.

Isabelle Rea is a writer living in New York.

March 20, 2024

The Disenchantment of the World

Waste collection trucks and collectors in a landfill in Poland. Cezary p, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

The children’s author Paul Maar tells the story of a boy who cannot tell stories. When his little sister, Susanne, is struggling to fall asleep, tossing and turning in her bed, she asks Konrad to tell her a story. He declines in a huff. Konrad’s parents, by contrast, love telling stories. They are almost addicted to it, and they argue over who will go first. They therefore decide to keep a list, so that everyone gets a go. When Roland, the father, has told a story, the mother puts an r on the list. When Olivia, the mother, tells a story, the father enters a large O. Every now and again, a small s finds its way on to the list in between all the r’s and o’s—Susanne, too, is beginning to enjoy telling stories. The family forms a small storytelling community. Konrad is the exception.

The family is particularly in the mood for stories during breakfast on the weekend. Narrating requires leisure. Under conditions of accelerated communication, we do not have the time, or even the patience, to tell stories. We merely exchange information. Under more leisurely conditions, anything can trigger a narrative. The father, for instance, asks the mother: “Olivia, could you pass the jam please?” As soon as he grasps the jam jar, he gazes dreamily, and narrates:

This reminds me of my grandfather. One day, I might have been eight or nine, grandpa asked for strawberry jam over lunch. Lunch, mind you! At first we thought we had misunderstood him, because we were having a roast with baked potatoes, as we always did on the second of September …

“This reminds me of … ” and “one day” are the ways in which the father introduces his narrations. Narration and remembrance cause each other. Someone who lives completely in the moment cannot narrate anything.

The mismatch between the roast and strawberry jam creates the narrative tension. It invokes the whole story of someone’s life, the drama or tragedy of a person’s biography. The profound inwardness betrayed by the father’s dreamlike gaze nourishes the remembrance as narration. Post-narrative time is a time without inwardness. Information turns everything towards the outside. Instead of the inwardness of a narrator, we have the alertness of an information hunter.

The memory prompted by the strawberry jam is reminiscent of Proust’s mémoire involontaire. In a hotel room in the seaside town of Balbec, Proust bends down to untie his shoelaces, and is suddenly confronted with an image of his late grandmother. The painful memory of his beloved grandmother brings tears to his eyes, but it also gives him a moment of happiness. In a mémoire involontaire, two separate moments in time combine into one fragrant crystal of time. The torturous contingency of time is thereby overcome, and this produces happiness. By establishing strong connections between events, a narrative overcomes the emptiness and fleetingness of time. Narrative time does not pass. This is why the loss of our narrative capacities intensifies the experience of contingency. This loss means we are subject to transience and contingency. The memory of the grandmother’s face is also experienced as her true image. We recognize the truth only in hindsight. Truth has its place in remembrance as narration.

Time is becoming increasingly atomized. Narrating a story, by contrast, consists in establishing connections. Whoever narrates in the Proustian sense delves into life and inwardly weaves new threads between events. In this way, a narrator forms a dense network of relations in which nothing remains isolated. Everything appears to be meaningful. It is through narrative that we escape the contingency of life.

Konrad cannot narrate because his world consists exclusively of facts. Instead of telling stories, he enumerates these facts. When his mother asks him about yesterday, he replies: “Yesterday, I was in school. First, we had maths, then German, then biology, and then two hours of sports. Then I went home and did my homework. Then, I spent some time at the computer, and later I went to bed.” His life is determined by external events. He lacks the inwardness that would allow him to internalize events and to weave and condense them into a story.

His little sister wants to help him. She suggests: “I always begin by saying: There once was a mouse.” Konrad immediately interrupts her: “Shrew, house mouse, or vole?” Then he continues: “Mice belong to the genus rodents. There are two groups. Genuine mice and voles.” Konrad’s world is fully disenchanted. It disintegrates into facts and loses narrative tension. The world that can be explained cannot be narrated.

Eventually, Konrad’s mother and father realize that he cannot narrate. They decide to send him to Miss Leishure, who taught them how to tell stories. One rainy day, Konrad goes to see Miss Leishure. At her door, he is welcomed by a friendly old lady with white hair and thick, still dark eyebrows: “I understand that your parents have sent you to me so that you can learn how to tell stories.” From the outside, the house appears to be very small, but inside there is a seemingly endless corridor. Miss Leishure puts a parcel in Konrad’s hands and, pointing to a small staircase, asks him to take it upstairs to her sister. Konrad ascends the stairs, which seem to go on forever. Astonished, he asks: “How is this possible? I saw the house from the outside, and it had only one floor. We must be on the seventh by now.” Konrad notices that he is all alone. Suddenly, in the wall next to him a low door opens. A hoarse voice calls out: “Ah, there you arse at last. Now home on and come bin!” Everything seems enchanted. Language itself is a strange riddle; it has something magical about it, as if it is under a spell. Konrad pokes his head through the door. In the darkness, he is able to make out an owlish figure. Frightened, he asks: “Who … who are you?” “Don’t be so purrious. Do you want to let me wait foreven?” the owlish creature retorts. Konrad stoops to go through the door. “Soon you’ll blow downhill! Have a lice trip!” the voice chuckles. At that very moment, Konrad notices that the dark room has no floor. He falls downwards through a tube at breakneck pace. He tries in vain to find something to hold on to, all the time feeling as though he has been swallowed by some enormous animal. The tube eventually spits him out at Miss Leishure’s feet. “What did you do with the parcel?” she asks angrily. “I must have lost it along the way,” Konrad answers. Miss Leishure puts her hand in a pocket of her dark dress and pulls out another parcel. Konrad could have sworn that it was the very same one she gave him earlier. “Here,” Miss Leishure says brusquely. “Please deliver this to my brother downstairs.” “In the basement?” Konrad asks. “Nonsense,” says Miss Leishure. “You’ll find him on the ground floor. We are up on the seventh floor, as you know! Now go!” Konrad cautiously descends the small staircase, which again seems to go on forever. After a hundred steps, Konrad reaches a dark corridor. “Hello,” he hesitantly calls out. No one answers. Konrad tries again: “Hello, Mister Leishure! Can you hear me?” A door next to Konrad opens, and a coarse voice says: “Of course, I swear you. I’m not deaf! Quick, come wine!” In the dark room there is a seated figure who looks like a beaver and smokes a cigar. The beaver creature asks: “What are you baiting for? Come on nine!” Konrad slowly enters the room. Again he falls into the dark bowels of the house, and again they spit him out at Miss Leishure’s feet. She draws on a thin cigar and says: “Let me guess? You failed to deliver the parcel again.” Konrad musters his courage to say: “No. But anyway, I am not here to deliver parcels but to learn how to tell stories.” “How can I teach a boy who cannot even carry a parcel upstairs how to tell a story! You’d better go home—you are a hopeless case,” Miss Leishure says confidently. She opens a door in the wall next to him: “Have a safe journey dome and all the west,” she says, pushing him out. Again Konrad slides down through the endless twists and turns of the house. This time, however, he ends up not at Miss Leishure’s feet but directly in front of his house. His parents and sister are still having breakfast when Konrad comes rushing into the house, announcing excitedly: “I have to tell you something. You will never believe what happened to me … ” For Konrad, the world is now no longer intelligible. It consists not of objective facts but of events that resist explanation, and for that very reason require narration. His narrative turn makes Konrad a member of the small narrative community. His mother and father smile at each other. “There you go!” his mother says. She puts a big K on the list.

Paul Maar’s story reads like a subtle social critique. It seems to lament the fact that we have unlearned how to tell stories. And this loss of our narrative capacity is attributed to the disenchantment of the world. This disenchantment can be reduced to the formula: things are, but they are mute. The magic evaporates from them. The pure facticity of existence makes narrative impossible. Facticity and narration are mutually exclusive.

The disenchantment of the world means first and foremost that our relationship to the world is reduced to causality. But causality is only one kind of relationship. The hegemony of causality leads to a poverty in world and experience. A magical world is one in which things enter into relations with each other that are not ruled by causal connections—relations in which things exchange intimacies. Causality is a mechanical and external relation. Magical and poetic relationships to the world rest on a deep sympathy that connects humans and things. In The Disciples at Saïs, Novalis says:

Does not the rock become individual when I address it? And what else am I than the river when I gaze with melancholy in its waves, and my thoughts are lost in its course? … Whether any one has yet understood the stones or the stars I know not, but such a one must certainly have been a gifted being.

For Walter Benjamin, children are the last inhabitants of a magical world. For them, nothing merely exists. Everything is eloquent and meaningful. A magical intimacy connects them with the world. In play, they transform themselves into things and in this way come into close contact with them:

Standing behind the doorway curtain, the child himself becomes something floating and white, a ghost. The dining table under which he is crouching turns him into the wooden idol in a temple whose four pillars are the carved legs. And behind a door, he himself is the door—wears it as his heavy mask, and like a shaman will bewitch all those who unsuspectingly enter. … [T]he apartment is the arsenal of his masks. Yet once each year—in mysterious places, in their empty eye sockets, in their fixed mouths—presents lie. Magical experience becomes science. As its engineer, the child disenchants the gloomy parental apartment and looks for Easter eggs.

Today, children have become profane, digital beings. The magical experience of the world has withered. Children hunt for information, their digital Easter eggs.

The disenchantment of the world is expressed in de-auratization. The aura is the radiance that raises the world above its mere facticity, the mysterious veil around things. The aura has a narrative core. Benjamin points out that the narrative memory images of mémoire involontaire possess an aura, whereas photographic images do not: “If the distinctive feature of the images arising from mémoire involontaire is seen in their aura, then photography is decisively implicated in the phenomenon of a ‘decline of the aura.’ ”

Photographs are distinguished from memory images by their lack of narrative inwardness. Photographs represent what is there without internalizing it. They do not mean anything. Memory as narration, by contrast, does not represent a spatiotemporal continuum. Rather, it is based on a narrative selection. Unlike photography, memory is decidedly arbitrary and incomplete. It expands or contracts temporal distances. It leaves out years or decades. Narrativity is opposed to logical facticity.

Following a suggestion in Proust, Benjamin believes that things retain within themselves the gaze that looked on them. They themselves thus become gaze-like. The gaze helps to weave the auratic veil that surrounds things. Aura is the “distance of the gaze that is awakened in what is looked at.” When looked at intently, things return our gaze:

The person we look at, or who feels he is being looked at, looks at us in turn. To experience the aura of an object we look at means to invest it with the ability to look back at us. This ability corresponds to the data of mémoire involontaire.

When things lose their aura, they lose their magic—they neither look at us nor speak to us. They are no longer a “thou” but a mute “it.” We no longer exchange gazes with the world.

When they are submerged in the fluid medium of mémoire involontaire, things become fragrant vessels in which what was seen and felt is condensed in narrative fashion. Names, too, take on an aura and narrate: “A name read long ago in a book contains within its syllables the strong wind and brilliant sunshine that prevailed while we were reading it.” Words, too, can radiate an aura. Benjamin quotes Karl Kraus: ‘The closer one looks at a word, the greater the distance from which it looks back.”

Today, we primarily perceive the world with a view to getting information. Information has neither distance nor expanse. It cannot hold rough winds or dazzling sunshine. It lacks auratic space. Information therefore de-auratizes and disenchants the world. When language decays into information, it loses its aura. Information is the endpoint of atrophied language.

Memory is a narrative practice that connects events in novel combinations and creates a network of relations. The tsunami of information destroys narrative inwardness. Denarrativized memories resemble “junk shops—great dumps of images of all kinds and origins, used and shop-soiled symbols, piled up any old how.” The things in a junk shop are a chaotic, disorderly heap. The heap is the counter-figure of narrative. Events coalesce into a story only when they are stratified in a particular way. Heaps of data or information are storyless. They are not narrative but cumulative.

The story is the counter-figure of information insofar as it has a beginning and an end. It is characterized by closure. It is a concluding form:

There is an essential—as I see it—distinction between stories, on the one hand, which have as their goal, an end, completeness, closure, and, on the other hand, information, which is always, by definition, partial, incomplete, fragmentary.

A completely unbounded world lacks enchantment and magic. Enchantment depends on boundaries, transitions, and thresholds. Susan Sontag writes:

For there to be completeness, unity, coherence, there must be borders. Everything is relevant in the journey we take within those borders. One could describe the story’s end as a point of magical convergence for the shifting preparatory views: a fixed position from which the reader sees how initially disparate things finally belong together.

Narrative is a play of light and shadow, of the visible and invisible, of nearness and distance. Transparency destroys this dialectical tension, which forms the basis of every narrative. The digital disenchantment of the world goes far beyond the disenchantment that Max Weber attributed to scientific rationalization. Today’s disenchantment is the result of the informatization of the world. Transparency is the new formula of disenchantment. Transparency disenchants the world by dissolving it into data and information.

In an interview, Paul Virilio mentions a science fiction short story about the invention of a tiny camera. It is so small and light that it can be transported by a snowflake. Extraordinary numbers of these cameras are mixed into artificial snow and then dropped from aeroplanes. People think it is snowing, but in fact the world is being contaminated with cameras. The world becomes fully transparent. Nothing remains hidden. There are no more blind spots. Asked what we will dream of when everything becomes visible, Virilio answers: “We’ll dream of being blind.” There is no such thing as a transparent narrative. Every narrative needs secrets and enchantment. Only our dreams of blindness would save us from the hell of transparency, would return to us the capacity to narrate.

Gershom Scholem concludes one of his books on Jewish mysticism with a Hasidic tale:

When the Baal Shem had a difficult task before him, he would go to a certain place in the woods, light a fire and meditate in prayer—and what he had set out to perform was done. When a generation later the “Maggid” of Meseritz was faced with the same task he would go to the same place in the woods and say: We can no longer light the fire, but we can still speak the prayers—and what he wanted done became reality. Again a generation later Rabbi Moshe Leib of Sassov had to perform this task. And he too went into the woods and said: We can no longer light a fire, nor do we know the secret meditations belonging to the prayer, but we do know the place in the woods to which it all belongs—and that must be sufficient; and sufficient it was. But when another generation had passed and Rabbi Israel of Rishin was called upon to perform the task, he sat down on his golden chair in his castle and said: We cannot light the fire, we cannot speak the prayers, we do not know the place, but we can tell the story of how it was done. And, the story-teller adds, the story which he told had the same effect as the actions of the other three.

Theodor W. Adorno quotes this Hasidic tale in full in his “Gruß an Gershom Scholem: Zum 70. Geburtstag” [Greetings to Gershom Scholem on his seventieth birthday]. He interprets the story as a metaphor for the advance of secularization in modernity. The world becomes increasingly disenchanted. The mythical fire has long since burnt itself out. We no longer know how to say prayers. We are not able to engage in secret meditation. The mythical place in the woods has also been forgotten. Today, we must add to this list: We are losing the capacity to tell the story through which we can invoke this mythical past.

Translated from the German by Daniel Steuer.

From The Crisis of Narration by Byung-Chul Han, to be published by Polity Press this April.

Byung-Chul Han is a philosopher and the author of more than 20 books including The Burnout Society, Saving Beauty and The Scent of Time. Born in South Korea, he lives now in Germany and has taught at Berlin University of the Arts.

Daniel Steuer is an independent scholar and translator of numerous works, including fourteen by Byung-Chul Han.

March 19, 2024

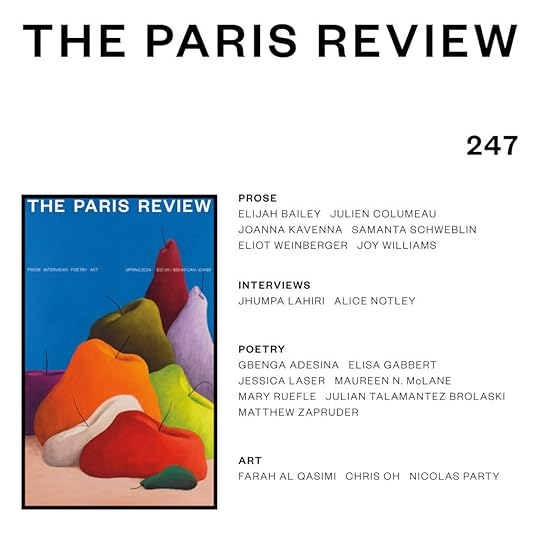

Announcing Our Spring Issue

Early in the new year, returning home from the office one evening, I picked up a story by the Argentinean writer Samanta Schweblin, translated by Megan McDowell. The opening pages of “An Eye in the Throat” place us in the thrall of an escalating family emergency, one that might belong to a work of autofiction. But in time, the nature of the story’s reality transforms. On finishing—I had to unclench my jaw and pour myself a drink—I realized that the narrative, like a tormenting Magic Eye, could be read in at least two distinct, and equally haunting, ways.

Like Schweblin’s story, several of the works in this issue seem to disclose, as if by optical illusion, a previously hidden plane of reality. Joy Williams gives us Azrael, the angel of death, who mourns the limited possibilities for the transmigration of souls as a result of biodiversity loss. In “Derrida in Lahore” by the French-born writer Julien Columeau, translated from the Urdu by Sana R. Chaudhry, an aspiring scholar studying in Lahore, Pakistan, is introduced to Derrida’s Glas (“You must read this,” his professor tells him, “it has fire inside it. Fire!”) and becomes a deconstructionist zealot. And in Eliot Weinberger’s “The Ceaseless Murmuring of Innumerable Bees,” bees become variously the symbols of socialism and constitutional monarchy, good luck and witchcraft, war and peace, and much else besides.

The subjects of our Writers at Work interviews, too, slip between worlds. Jhumpa Lahiri, in her Art of Fiction interview, describes “the woeful treadmill of needing approval” that drove her, at the height of critical and commercial success, to leave her American life behind. “It’s only when I’m writing in Italian that I manage to turn off all those other, judgmental voices, except perhaps my own,” she tells Francesco Pacifico, with whom, in Rome, she spoke in her new language. And in her Art of Poetry interview, Alice Notley describes the need, in her work, to go beyond conscious thought and the “scrounging” of everyday life—beyond, even, the grief of losing loved ones. “You might just freeze, but if you don’t, other worlds open to you,” she tells Hannah Zeavin, before adding, casually, “I started hearing the dead, for example.”

Perhaps a kind of doubleness is fitting for the spring we’re in: the season of hope, which is, this year as ever, filled with dread. When we asked the Swiss artist Nicolas Party to make an artwork for the cover of our new issue, he sent us not one image but two. Like in de Chirico’s The Double Dream of Spring, painted early in the First World War, each image exerts a kind of formal terror, at once seductive and monstrous. We decided that, for the first time in the magazine’s seventy-one-year history, the issue would have twin covers. Subscribers will receive the cover featuring a still life, an array of uncannily sagging apples and pears against rich blue. Buyers at newsstands and bookstores can pick up the version featuring a coastal landscape, albeit one in which the ocean is green and the sky a candy pink. If you’d prefer to alternate between realities, you can always have both.

Emily Stokes is the editor of The Paris Review.

March 18, 2024

“It’s This Line / Here” : Happy Belated Birthday to James Schuyler

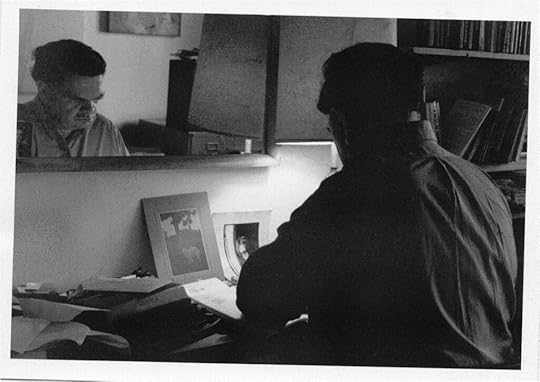

James Schuyler at the Chelsea Hotel, 1990. Photograph by Chris Felver.

I’d planned to write about one of my favorite James Schuyler poems in time for the centenary of his birth last November, but

Past is past, and if one

remembers what one meant

to do and never did, is

not to have thought to do

enough? Like that gather-

ing of one of each I

planned, to gather one

of each kind of clover,

daisy, paintbrush that

grew in that field

the cabin stood in and

study them one afternoon

before they wilted. Past

is past. I salute

that various field.

The tiny, beloved “Salute”—which is not the poem that I mean to discuss—both gathers and separates, does and then undoes what the poem says Schuyler meant to do but never did. (And isn’t this, the play of assembly and disassembly, to a certain extent just what verse is? How part and whole relate or fail to as the poem unfolds in time is a basic drama of poetic form.) Schuyler’s enjambments—at once distinct and soft, like the edge of a leaflet or the margin of a petal—are sites of hesitation where meanings collect before they’re scattered or revised.

For a second I hear “Like that gather-” as an imperative: Do it that way, gather in that manner, before the noun “gathering” gathers across the margin. I briefly hear “one of each I”—each of us is a field of various “I”s—as the object of the gathering before it becomes the subject who has “planned” it. (The comparative metrical regularity of “Like that gathering of one of each I planned,” the alternating stresses, haunts these enjambments, a prosodic past or frame the poem salutes and breaks with, breaks up.) I am always slightly surprised when “to gather one,” at the end of the seventh line, repeats “of each,” as opposed to modifying a new specific noun, at the left margin of line eight. (This break makes me feel the tension or oscillation between “each” and “kind”—and a kind is a gathering of likes—between the discrete specimen and the class for which it stands, the particular dissolving into exemplarity, when you write it down.)

There is so much repetition in the short poem—“one,” for instance, appears five times, undoing the singularity; here it’s a person, here a number, here a specific afternoon. It’s as if the vocabulary were being restricted, held constant, so Schuyler can test what relineation might do to the music and meaning, “studying” each tentative arrangement of the small words he’s gathered. (There is a sense of provisionality and casualness and plain speech here and most everywhere in Schuyler, but it coexists with the implication of archival formal order; there’s the prosodic backdrop I mentioned, but there’s also the near syllabic regularity of the lines—eight of the fifteen are six syllables, for instance—or that long u sound at the end of the fourth and twelfth and fourteenth line, which provides some sonic architecture.)

And then there is the crucial repetition of the tautology “Past is past,” a repetition (of a repetition) that affirms for me that the poem is testing how it might make difference out of sameness, transforming the phrase by delaying the verb across the break when it recurs. The past returns with a difference: “Past is past” does not equal “Past / is past.” So much depends on that nonidentity. The latter instance of the phrase, while still melancholy, has a heartbeat: the silence at the break is felt, possesses its own duration, the form happens in the renewable present tense of reading, so that—to take a phrase from Jack Spicer—the “thing language” of the poem overcomes its content, and the line no longer laments time that is simply lost. I don’t mean to make the poem sound triumphant, to imply that time is unequivocally regained, for a “salute” can be a salutation or an elegy (as in a funeral salute), and it’s the oscillation—I’m going to run with the word—between those modes that lends the poem its tender force. Still, one is grateful Schuyler only meant to gather specimens so that the field, in all its variety, is intact.

***

But I meant to talk about another poem, another flower, “The Bluet,” in time for his hundredth birthday.

THE BLUET

And is it stamina

that unseasonably freaks

forth a bluet, a

Quaker lady, by

the lake? So small,

a drop of sky that

splashed and held,

four-petaled, creamy

in its throat. The woods

around were brown,

the air crisp as a

Carr’s table water

biscuit and smelt of

cider. There were frost

apples on the trees in

the field below the house.

The pond was still, then

broke into a ripple.

The hills, the leaves that

have not yet fallen

are deep and oriental

rug colors. Brown leaves

in the woods set off

gray trunks of trees.

But that bluet was

the focus of it all: last

spring, next spring, what

does it matter? Unexpected

as a tear when someone

reads a poem you wrote

for him: “It’s this line

here.” That bluet breaks

me up, tiny spring flower

late, late in dour October.

Instead of beginning with the past, we start with “and,” in medias res, evoking the epic the poem obviously isn’t, although the question of stamina—of effort and its prolongation—seems consonant with the generic marker, and, from the perspective of something “so small,” unseasonably pushing through the soil is pretty epic.

It’s remarkable how much erotic or at least potentially erotic language the poem begins with, but without sex overwhelming the lexical field. I dare you to put the following terms in a Google search: “stamina,” “freaks,” “splashed,” “creamy,” “throat.” All this makes the “Quaker lady” sound a little like a freak, maybe in drag, but then such a reading is cut by the proximity of “lady” to “lake,” which makes it literary, idealizing, Arthurian (epic). So there is oscillation between scales, including of genre, and between the carnal and the courtly. And then “stamina” is also a plural of stamen, which is the pollen-producing male reproductive organ of the Quaker lady (of the Lake) in question. The grammar of the line keeps the botanical sexual sense from being the primary one, but it’s there. The words themselves waver between being plain and literary, thingly and allusive, while the diction is at once talky and taut, a little heightened.

I like that “held” at the end of the seventh line, how “held” just manages to hold the splash of sky before it spills over the precipice of the right margin. You can almost see it tremble with the effort, buttressed by the comma. All three of the words in the line end in d, and all the letters of “held” are held by “splashed,” as if they splashed out of the longer word. “[P]etaled” in the subsequent line seems to synthesize the sounds of “splashed” and “held,” and what a lovely definition of a petal: a splash of color that held, that holds, until it withers. (The l sounds of “petaled” will later be held still in “still,” after resting in “apple,” then break into a “ripple,” and then continue to ripple through the poem, viz. “oriental.”)

The “paintbrush,” that important kind of flower in “Salute,” is so called because it is said to resemble brushes dipped in bright red or orange-yellow paint. And I think the bluet in this poem is both an actual blue flower in the world and, invariably, the blue flower of art, the Blaue Blume of Novalis. There is another crucial oscillation, then, between nature and culture, between a particular blossom and a poetic symbol. Schuyler himself might discourage this reading: “All things are real / no one a symbol,” begins the poem “Letter to a Friend: Who is Nancy Daum?” and in an interview Schuyler said: “I’m not … interested in the idea of the rose as it occurs on and on throughout literature, I’m interested in roses, in Georg Arends, and a new rose.” But even in (these very Williams-like) disavowals of the flower as symbol, there is a blurry boundary between nature and convention: the “new rose” is brought into existence via the horticulturalist’s art, the flower is named for its “author” (Georg Arends), it is ornamental. And what could be more literary than to be fascinated by the name of the rose, obsessed as Schuyler was by the nomenclature of flowers? (Schuyler’s “Horse Chestnut Trees and Roses,” for example, is as much a celebration of the names of cultivars as the flowers themselves.) So while the flower is never merely a symbol in Schuyler, it could be said to symbolize the meeting of nature and culture, of the given and the made, of the discrete things and the kinds that language makes.

Maybe it’s more to the point to say that Schuyler’s description of the flower transforms it into art, and that this kind of transformation is his signature poetic activity; it happens again and again in his poems: he describes what he sees before him as if it were a painting so that observation of the natural world becomes ekphrasis. That’s why—to skip down a little—the leaves are likened to a rug, crossing outside and inside, nature and culture, and those leaves “set off” the gray the way a painter or sharp dresser uses one color to set off or complement another, why the air is like a made thing, too, if one you eat, and why the bluet is called “the focus,” the way art critics say something is “the focus of the composition.” Schuyler’s words are paintbrushes, what he describes becomes a painting (though he treats it as already painted)—paint, a medium that splashes and then holds. There are examples of this everywhere in his books. In “Evenings in Vermont,” for instance, a rug again mediates between inside and outside, art and nature: “I study / the pattern in a red rug, arabesques / and squares, and one red streak / lies in the west, over the ridge.” In “Scarlet Tanager,” the bird in the tree provides “the red touch green / cries out for.” In “A Gray Thought,” “a dark thick green” is “laid in layers on / the spruce …” And so on. Touches, layerings: color as paint, natural phenomena perceived as art.

There is a mild modernism here that reenchants the world—barely, briefly—by converting what’s merely there into significant form so that the landscape becomes a history of small artistic decisions. Whose decisions, whose touches and layerings? Not God’s, and not quite Stevens’s “major man” reinvesting the world with meaning through the powers of poetic imagination. But not not that either: It’s more like a minor man, who has looked at a lot of good paintings, and also looked—in a lot of pain—out of the window (another frame) of Payne Whitney (the mental hospital where Schuyler spent some time; “Salute” was written in Bloomingdale Hospital in White Plains). Williams said “no ideas but in things,” Stevens said that poetry’s power is “the power of the mind over the possibilities of things,” Schuyler oscillates between them. Schuyler is closer to Williams in the attention to mundane speech and the mundane things at hand (e.g., a Carr’s cracker; which is not to say Stevens had no concern with dailiness, or “ordinary evenings”), crucially closer to Williams in enjambment as the foundational poetic technique (I think of Spring and All: “so that to engage roses / becomes a geometry—”). But Schuyler is a little more like Stevens in the project of imaginative redescription: bluet, blue flower, blue guitar. The literary genealogy doesn’t really matter (and one could configure it differently); my point is that the magic of Schuyler is that you feel nature becoming art as you read. Or you feel the effort to make it so, its fluctuations, often its failure.

Of course, he’s not describing an actual painted image, but making a poetic one; Schuyler is composing the scene, the small decisions are his, but it feels like he’s engaging another medium, and so the poet’s act of creation is smuggled in, as if he were just looking at somebody else’s representation of the view. This gives his voice a kind of secondariness, a kind of modesty—I’m not the visionary, I’m just reviewing the visions for Art News (where he was an associate editor). This in part accounts for how his tone is simultaneously matter of fact and metamorphic. Schuyler makes his writing seem like he’s “reading” a painting, but this kind of secondariness actually becomes a species of immediacy because his ekphrastic language also describes his own verbal form, the poem we’re reading: the splashes and holds, the falls from margin to margin. This means that Schuyler’s “reading” and our reading of Schuyler correspond, our acts of attention are calibrated across time.

(I assume it’s obvious that I’m not suggesting Schuyler is the only poet who makes the world seem like a made thing, like art, or that he’s the only poet whose unfolding perceptions are transferred to poetic form so that, as we attend to his work, author and reader are in a sense coeval; on the contrary, some version of such transformations and transfers are present in the writing I love across genres and eras. But that’s why I’m trying to describe and celebrate Schuyler’s specific, quiet style, his techniques and tonalities; in his minor way, he makes contact with something fundamental.)

(And here I might mention that, while they are very different writers, Schuyler’s tendency to reframe nature as art is a characteristic shared with his friend, the brilliant Barbara Guest, and while Schuyler’s talkiness and dailiness have more in common with O’Hara—who couldn’t, as he wrote in “Meditations in an Emergency,” “even enjoy a blade of grass” unless he knew “there’s a subway handy, or a record store or some other sign that people do not totally regret life”—Schuyler is in many ways closer to Guest in his tendency to redescribe nature as culture, to present the merely contingent as arranged. As with Schuyler, this transformation in Guest often involves a window—a frame through/in which natural phenomena might appear as the touches or layerings of the compositional. Art and windows are often paired in Guest, as in her great poem, “The View from Kandinsky’s Window,” or the title of her collected writings on art, Dürer in the Window. Has someone written an essay on the windows of The New York School? I think of Ashbery’s “October at the Window” or “The New Higher”—“… the window where / the outside crept away”—and O’Hara’s small “Windows”: “this space so clear and blue / does not care what we put // into it …” One way Schuyler has a significant aesthetic affiliation with these other writers—as opposed to just a social one—is in his experiments with what one can put into the window: “put into” because the frame of the window stands for the transformation of contingency into composition. For his part, Schuyler is clear and modest—sometimes to the point of quiet comedy—about the centrality of the window to his compositions. Interviews get answers like this when they ask him about his method: “[T]here are things all through the poem that are actually what I’m seeing out the window in Southampton,” “The things described in it are what I was seeing out the window in the house in Maine,” and so on.)

But to return to lateness and its undoing: “Past is past,” “late, late”—belatedness is the traditional theme that “Salute” and “The Bluet” indulge and, in their small way, defeat or, better, gently suspend. The bluet can be assigned to the last spring or the next one, that doesn’t matter, since it’s happening now, unexpected as a “tear” (rhymes with dear) that we’re not entirely sure isn’t a “tear” (rhymes with dare, like the torn or jagged right margin of a poem) until it’s tuned—made decisively lacrymal—by the “here” arriving at the left margin in the third to last line. “Tear” itself remains suspended between being a drop (recalling the drop of sky the flower holds) or something rent “so as to leave ragged or irregular edges” until it drops over the irregular edge of the poem. “It’s this line / here.”

Except it isn’t, or it is and isn’t: “this” refers (at least at first) to the fourth to last line, the “here” begins the third to last. The line about the line that caused the tear is torn across the margin, it’s in both places at once, or it’s in neither place, a Schrödinger’s cat of a line. Last line, next line, what does it matter? One way it matters is that the formal irony—the way the line break renders “this” and “here” paradoxical, undecidable—means that these deictics seem ultimately to refer to the unnameable break itself, that little moment of hesitation that we use a virgule to denote in prose, a felt silence, the white space that is the drop of sky or teardrop no longer held or contained within the terms of the poem; emotion is instead expressed by formal motion. (Dramas of lineation are further heightened by the fact that this poem—like “Salute”—is a single stanza; there are no larger breaks, no other species of segmentation, competing with the irregular margins.) “Past is / past,” “It’s this line / here”—all of poetry is for me in these little delays, catches in the breath, delays that both formally enact belatedness and, by making it felt in the embodied present tense of reading, undo it.

In both instances—“Past is past” is a cliche; “It’s this line / here” is quoted speech from a friend or lover—Schuyler is breaking up received phrases, found language, showing how lineation, how art, can alter the given, how secondariness isn’t just lateness but an opportunity for imaginative transformation. The person Schuyler quotes has to point to the line that moves him; it escapes description or paraphrase. (I think of the “him,” whatever the biographical facts, as a lover because of the erotic language earlier in the poem, where the drops of sky, why not just say it, might also be sexual fluid.) It’s a wonderful feedback loop of reading and writing (or a Möbius strip in which the two become a single practice): Schuyler writes the poem that moves the lover, Schuyler is moved that the lover is moved, the lover’s language about being moved—indicating a line we never see—is then so movingly arranged, broken up in a second poem that breaks me up each time I read it. So mere belatedness is replaced with a chain of feeling to which we readers can add links. Another poet would sound self-aggrandizing—look how my poems move men to tears!—but what I hear is Schuyler’s melancholy gratitude, admiration, for that openness, receptivity, which his poem communicates, makes available in the “/ here” of poetry. (Schuyler’s “this line / here”—the indication without quotation of the line in question—reminds me of Denise Levertov’s “The Secret,” another poem in which the poet is moved by readers’ capacity to be moved, and in which the adventure of enjambment—the way poetic form happens—is celebrated for its inexhaustibility: “Two girls discover / the secret of life / in a sudden line of / poetry. // I who don’t know the / secret wrote / the line …”) That “/ here” is what I hear described in Schuyler’s thank you poem to Kenward Elmslie for the gift of a letter opener in “A Stone Knife,” a poem that recalls “Salute,” and that both celebrates and enacts the renewable “surprise” of poetic form:

the surprise is that

the surprise, once

past, is always there:

which to enjoy is

not to consume. The un-

recapturable returns …

***

Schuyler’s breaks, his sense of the line, are precious to me, and yet he was matter of fact to the point of dismissiveness about how they came to be. “I don’t really know how I happened to get into writing such very thin poems,” he told an interviewer. “I was writing in very small notebooks that I carried around with me, and it was easier just to write like that …”

I think I started it because I wrote in John Ashbery’s living room—I was on my way to Southampton and Vermont—a poem called “Who is Nancy Daum?,” which is in The Crystal Lithium, and I had written that in a very small notebook, thinking that I could rearrange the lines if they weren’t long enough for whatever lines I intended. It was the kind of notebook you carry in your jacket pocket. And then when I came to type it up, I thought I would leave it the way it was, in jagged lines.

Some feel this is evidence that Schuyler’s poems are haphazardly composed, and so it’s some kind of misreading to be moved by this or that “line / here,” but I find this casual account of lineation entirely compatible with the complex and delicate effects his enjambments produce. When a painter decides on the size of a canvas to stretch, we don’t then discount every other compositional decision she makes as random. That’s how I think of those notebooks in which so many of the poems I love were made: that Schuyler was often negotiating a miniature, objective margin in real time as his acts of observation unfolded strikes me as another way we might meaningfully speak of him as painterly (often a supremely meaningless adjective for a poet), another way the presence of a frame structured his compositional technique, whether he took the notebook en plein air or worked indoors, looking back and forth from notebook to window. Notebook and window, his two frames. It makes me think of one of my favorite of his uncollected poems, another poem that echoes “Salute,” and its pasts that are and aren’t past: “A Blue Shadow Painting,” dedicated to Fairfield Porter, that begins by describing “an evening real as paint on canvas.” When the painter in this poem loads his brush and concentrates, it’s “as though he saw neither the work in hand nor the subject”—he makes quick, perhaps only semi-conscious decisions in the time of composition, thereby managing to store some of that time in art, where it awaits us: “The day / is passing, is past: multiple and immutable came to live / on a small oblong of stretched canvas … ”

***

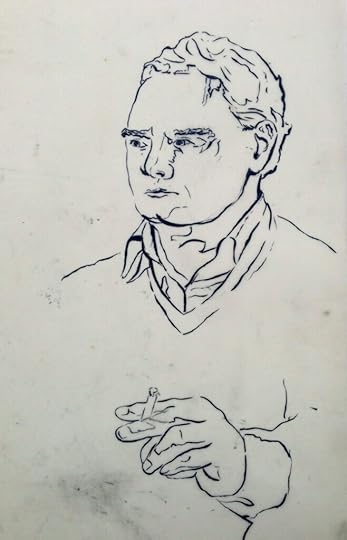

Darragh Park, Portrait of James Schuyler, 1996, ink on acetate, 10 x 8″. Private collection.

There are, of course, a range of forms (and moods and modes) in Schuyler—long poems, poems with very long lines, poems that incorporate a lot of white space, not to mention the novels—but my Schuyler will always be the miniaturist of “Salute” or “The Bluet” (or “Korean Mums,” and other flowers). In these poems in particular Schuyler possesses a kind of soft Midas touch in which everything his eye alights on becomes art, becomes composition as he describes it, and then his own compositional decisions—especially his enjambments, his unexpected tears (rhymes with stairs)–bring our attention in line with his, so that we feel we are looking together across time, and so the past is not merely past, but always present in the form, available as the present of form, which is never consumed.

But again I feel I’m making him sound too triumphant, as if losses were ultimately overcome. I say it’s a Midas touch because often in Schuyler the poem, the art, is a document of emotional suffering and isolation. The drama of part and whole so central to poetry is also a drama, in Schuyler, of holding it together; the threat of falling apart is emotional, not just technical. (I’ve always been struck by the injunction: “Compose yourself,” a cruel and revealing thing to say to an upset person.) Sometimes the lines seem to tremble with the effort; sometimes the desire to bring the outside inside, to press nature into art, has a quiet desperation, as in these last lines of the last poem I’ll quote in its entirety, “February 13, 1975,” one of the poems written in Payne Whitney:

Tomorrow is St. Valentine’s:

tomorrow I’ll think about

that. Always nervous, even

after a good sleep I’d like

to climb back into. The sun

shines on yesterday’s new

fallen snow and yestereven

it turned the world to pink

and rose and steel blue

buildings. Helene is restless:

leaving soon. And what then

will I do with myself? Some-

one is watching morning

TV. I’m not reduced to that

yet. I wish one could press

snowflakes in a book like flowers.

So many of the oscillations I’ve described are happening softly here. Do you read the first line as talky, as matter of fact, or as iambic tetrameter, evoking a traditional prosody that the poem will then break up? (I hear the last line of the poem as echoing and revising the meter; to my ear, it’s trochaic tetrameter, though my friends hear it differently.) There is the plain speech (and ghosts of made phrases: nothing new under the sun; “yesterday’s news” is almost there in the sixth line) coexisting with the archaic literariness of “yestereven.” This casualness, the talkiness, is also cut by the sonic relays—”into,” “new,” “blue,” “soon,” “do,” “reduced”—that help hold the form together. The world becomes a made thing when the sun turns it into “steel blue / buildings.” (And even the small surprise of “TV” at the left margin of the third to last line, where “morning” reveals itself to be an adjective and not the object of someone’s watching, is another instance of nature becoming culture.) And again we have the temporal tensions, glitches across the margins, as in “yesterday’s new / fallen snow.” What was new yesterday is already old, the new fallen is the recently belated, especially if you make the “new” pause for a moment before it falls. The poem (like every poem?) is late and early (like a spring flower in October) as it is written in lonely anticipation of tomorrow, Valentine’s Day, and all this leads to the fantasy of art existing outside of time, of a “yet” that could be pressed, the snow preserved between the pages like a flower one planned to gather.

And is not to have thought to do / enough?

Ben Lerner’s most recent book is The Lights. This talk was delivered as part of a new semiannual lecture series at the Poetry Society of America in Brooklyn.

March 15, 2024

The Celebrity as Muse

Sam McKinniss, Star Spangled Banner (Whitney), 2017. Courtesy of the artist.

1. The Divine Celebrity

“There isn’t really anybody who occupies the lens to the extent that Lindsay Lohan does,” the artist Richard Phillips observed in 2012. “Something happens when she steps in front of the camera … She is very aware of the way that an icon is constructed, and that’s something that is unique.” Phillips, who has long used famous people as his muses, was promoting a new short film he had made with the then-twenty-five-year-old actress. Standing in a fulgid ocean in a silvery-white bathing suit, her eyeliner and false lashes dark as a depressive mood, she is meant to look healthily Californian, but her beauty is a little rumpled, and even in close-up she cannot quite meet the camera’s gaze. The impression left by Lindsay Lohan (2011), Phillips’s film, is that of an artist’s model who is incapable of behaving like one, having been cursed with the roiling interior life of a consummate actress. Most traditional print models can successfully empty out their eyes for fashion films and photoshoots, easily signifying nothing, but Lohan looks fearful, guarded, as if somewhere just beyond the camera she can see the terrible future. Unlike her heroine Marilyn Monroe, Phillips also observed in a promotional interview, Lohan is “still alive, and she’s more powerful than ever.” It is interesting that he felt the need to specify that Lohan had not died, although ultimately his assertion of her power is difficult to deny based on the evidence of Lindsay Lohan, which may not exude the surfer-y, gilded vibe he might have hoped for, but which does act as a poignant document of Lohan’s skill, her raw and uncomfortable magnetism.

“Lindsay has an incredible emotional and physical presence on screen that holds an existential vulnerability,” Phillips argued in his artist’s statement, “while harnessing the power of the transcendental—the moment in transition. She is able to connect with us past all of our memory and projection, expressing our own inner eminence.” “Our own inner eminence” is an odd, not entirely meaningful phrase, used in a typically unmeaningful and art-speak-riddled press release. What the artist seems to say or to imply, however, is that Lohan’s obvious ability to reach inside herself and then—without dialogue—vividly suggest her depths onscreen acts as a piquant reminder of our own complexity, the way each of us is a celebrity in the melodrama of our lives.

What makes Lindsay Lohan art and not a perfume advertisement, aside from the absence of a perfume bottle? The same quality, perhaps, that makes—or made—Lohan herself a star, as well as, once, a sterling actress. All Phillips’s talk of transcendence and the existential may be overblown, but then stars tend to be overblown, as evidenced by the superlatives so often used in descriptions of Hollywood and its denizens: “silver screen,” “golden age,” “legendary,” or “iconic.” “Muses must possess two qualities,” the dance critic Arlene Croce claimed in The New Yorker in 1996, “beauty and mystery, and of the two, mystery is the greater.” At first blush, Lohan might not have seemed like an especially mysterious muse, with her personal life splashed across the tabloids and her upskirt shots all over Google. In fact, her revelations are a trick, the illusion of intimacy possible because she has enough to plumb that we can barely touch the surface. We can see her pubis and her mugshots and the powder in her nostrils, but it is impossible for us, as regular, unfamous people, to know what it feels like to be her.

“When [Lohan] bats her eyes over the Gagosian Gallery logo at the end of Phillips’s short film, millions of art world dollars immediately alight upon our shores,” the late and cantankerous art critic Charlie Finch wrote in a review of Lindsay Lohan, later noting that the film also acts as a salute to “the cosmetology industry as treated cosmologically.” “Few beauties have (ahem) not required the surgeon’s knife as little as Lindsay,” Finch continues, “but her lips sure appear to be as (allegedly) collagen-injected as those of Melanie Griffith, Meg Ryan, or Cher. Score another point for Richard Phillips, patron saint of female models everywhere and their cutting-edge search for visual perfection.” It was certainly permissible to write about a female subject in a rather different tone in 2011, and the titillated focus on cosmetic surgery here now feels quaint. Still, whether or not Finch is being facetious, he is right about Phillips’s willingness to lavish his attention on the hard work stars do to keep themselves suitably celestial, ensuring prominent places in the firmament of fame.

In the same year, Phillips mounted a show at London’s White Cube that featured portraits of a host of other desirable famous people, including Zac Efron, Robert Pattinson, and Miley Cyrus, all of whom the gallery’s write-up described as “secular deities.” In each image, Phillips carefully renders a wallpaper-style repeated pattern of a high-end designer monogram—for instance, the Louis Vuitton “LV”—behind his subjects, meant to replicate what are known in the trade as “step and repeat” backdrops from red carpets, but also intended to highlight the astronomical and enviable value of the figures he depicts. The works, which he called a comment on “the marketability of our wishes, identity, politics, sexuality and mortality,” are not necessarily anti-celebrity, and in fact the flatness and the faux naïveté of Phillips’s brushwork lends them the impression of a brilliantly executed bit of fan art.

Actors and actresses are often rumored to be smaller than the average person, maybe because of the adage that the camera adds ten pounds, or maybe because they are increased to a Godlike scale regardless when they are projected on a screen, making their real size more or less irrelevant. Certainly, there is no other quality that magnifies an individual like charisma, helping to explain why we continue to be shocked to learn that, say, Marlon Brando was a little under five foot nine. Phillips’s canvases, which render what are in effect premiere headshots at about ten times the size of actual life, perform the same alchemy the cinema screen does, minus the narrative and the individuating sheen of cinematography. They show Chace Crawford or Leonardo DiCaprio for what they really are: supersized, halfway between a spokesmodel and a god, as inseparable from commerce as a Louis Vuitton handbag. Asking what differentiates Lindsay Lohan from a perfume advertisement, aside from the lack of purchasable perfume, is, in other words, redundant: Lohan may be hard to understand or to completely tame, but she was still at one time a big seller, and just like an artwork her intrinsic value is and always has been subject to trends, market fluctuations, her ability to look good in a well-appointed room. Disappointingly sublunary, to think that a star might be no more than a product—but then it is equally depressing to think that the same is true of a supposed artwork.

2. The Decaying Celebrity

In 1974, in Florence, a Californian hippy couple were visiting the Uffizi when a strange thing happened to the heavily pregnant wife: as she stood admiring a da Vinci, she began to feel her baby moving, as if he too had been struck by the genius of the work. “Allegedly, I started kicking furiously,” Leonardo DiCaprio told an interviewer at NPR in 2014. “My father took that as a sign, and I suppose DiCaprio wasn’t that far from da Vinci. And so, my dad, being the artist that he is, said, ‘That’s our boy’s name.’ ” That I first encountered this origin story as a child at the height of Leo-mania in the nineties, in an unofficial souvenir book about the then-twenty-one-year-old actor and heartthrob, feels entirely apposite: it is a clever bit of mythmaking, an anecdote that might just as well have belonged to classic Hollywood and the era of Photoplay or Screenland as to the first, faltering days of the online age. DiCaprio’s father, an underground comics publisher who associated with both Timothy Leary and the graphic artist and world-renowned macrophiliac Robert Crumb, foresaw Leonardo’s future status as an artist even if he was not certain of the medium he would work in. Many of us who were prepubescent when Leonardo DiCaprio first rose to real prominence are eminently aware of his nineties image as the ultimate nonthreatening (very nearly nonsexual) sex symbol, so rosy-faced and champagne-haired and softly pretty that that he might as well have been a handsome girl, but the ardor of his swooning fanbase did not cancel out his reputation in adult critical circles as a genuine early master of his craft. Consider the cool, casual way he delivered Shakespeare in Romeo + Juliet (1996), Baz Luhrmann’s loony, technicolor adaptation of the play: young, alive, unmistakably Californian, he spoke all his thee’s and thou’s with the throwaway inflection of a person fluently communicating in a second language they had practiced all their lives.

As it happened, DiCaprio ended up with a more literal link to art in later life, becoming a collector of such scale and (to use Phillips’s word) eminence that, in spite of his being a supposedly frivolous Hollywood A-lister, the art world takes him fairly seriously. Unlike, say, collecting classic cars or couture clothing, the maintenance of an art collection has the dual benefit, for a celebrity, of conferring cultural cachet and trumpeting their tremendous wealth (provided, of course, that their selections knowingly and tastefully run the gamut from aesthetically desirable to conceptually rigorous, haute-contemporary to historical). DiCaprio—who does not seem to have an art buyer in his employ, and who therefore presumably actually cares about the pieces he acquires—is catholic in his tastes, collecting works by artists like Basquiat and Picasso as well as other, much newer works by relative unknowns.

It may be the comprehensive breadth of his collection that has led to his being courted, then immortalized, by more than one prominent artist. Elizabeth Peyton has painted him twice—the first work, Swan, was produced based on a photograph by David LaChapelle in 1998, and the second, Leonardo, was created after DiCaprio sat for her in 2013. In Swan, the actor is at the vertiginous height of his babyish loveliness, and he is depicted with a swan’s neck draped around his shoulders, ruby-lipped and pouting, his eyes bluer than any human being’s and his skin as pale and as bloodless as a vampire’s. In Leonardo, he looks stolid and serious, his flat cap pulled down to hide a little of his famous face. There is an evident difference in the style of both these works: Swan is more abstracted, closer to a fantasy than to a fact, and Leonardo has a detailed intimacy that makes it more recognizably an image of its subject. In addition to the maturation of the painter, it is reasonable to imagine that her first portrayal of DiCaprio, especially because it has been drawn from a heavily stylized fashion image, has more to do with how she imagined him at a great, awestruck distance in the nineties, and the second is a more accurate and less starry record of what it is really like to meet one’s hero, i.e., sometimes not as glamorous as one might think.

In her list of the top ten cultural objects of the year for Artforum in 1999, Peyton cited Leonardo DiCaprio’s brief appearance in the 1998 Woody Allen film Celebrity as an artistic highlight. Playing a young A-list actor with the generic, haute-American name Brandon Darrow, DiCaprio is required to stand in for all of Hollywood’s excesses, and he does so with aplomb, strutting through an Atlantic City casino and snorting cocaine off the back of his delicate hand with such assurance and such grace that it is easy to see why he was a phenomenon in the late nineties. His cameo is “ten electrifying minutes of seeing Leonardo be what he really is,” Peyton rhapsodized. “Usually we have to see him being nice and innocent. Here he is a huuuuge star: powerful, arrogant, and beautiful.” That combination of power and beauty is what the painter aims to capture in her subject in Swan, and the cruel and foppish pursing of his lips suggests a little arrogance too. Although Peyton has reproduced her young DiCaprio from an editorial photograph, her choice to use the image with a swan may be a subtle nod to Zeus, who in Greek myth disguised himself as one in order to fuck Leda, as if he were a celebrity disguising himself to hook up with an unfamous fan.

In 2019—by which time he was very powerful indeed, even if he was also significantly less beautiful—DiCaprio commissioned the Swiss artist Urs Fischer to produce a portrait of his family, presumably hoping to usher his art-appreciating mother and father into the annals of art history in much the same way he himself had been immortalized in those earlier works by Peyton. Fischer chose to render the DiCaprio family at a larger-than-life scale, not in paint or marble but in wax, as part of an ongoing series of candle works. The piece, titled Leo (George & Irmelin), shows two melded Leonardos, one being embraced by his mother, Irmelin, and one apparently engaged in conversation with his father, George, in a setup meant to reference the son’s status as the child of separated parents. The figures, brilliant white with light pink and baby blue touches, are designed to melt into liquid once the wicks that emerge from their four respective heads are lit, and inside they are pitch-black, making the piece a rather bleak portrayal of a shattered family unit.

Looking from Elizabeth Peyton’s Swan to her later Leonardo, it is possible to see a record of another kind of dissolution, from the smooth and stainless early Leo to the older, less cherubic incarnation, a transformation that seemed to happen at DiCaprio’s behest as he eschewed stylists and personal trainers in his off-set downtime—a destruction of his ultrasaleable and almost feminine cuteness in favor of a more crumpled human guise, not overexercised or neatly shaven or attired in designer clothing but more versatile, more real. Paradoxically, in spite of his profile as a Hollywood actor never having been more serious or more prominent, in Leonardo and in Leo (George & Irmelin), his image is not necessarily that of a “huuuuge star,” but of something closer to the thing he “really is”: a very famous middle-aged man who has been touched by time in more or less the same way as an average and unfamous one, his youthful luminousness having melted like pale wax. The writer Osbert Sitwell once observed that those who sat for portraits by John Singer Sargent looked at the results and “understood, at last, how rich they were.” One wonders if DiCaprio looked at Urs Fischer’s rendering of him as a thing of obvious impermanence, a fleeting source of light, and finally understood that no amount of wealth would stave off death, however many twenty-four-year-olds he slept with.

3. The Martyred Celebrity

In 2017, the painter Sam McKinniss produced a portrait of the late Whitney Houston entitled Star Spangled Banner, based on a shot from Houston’s transcendent performance of the American national anthem at the Super Bowl in 1991. The piece is a spotless invocation of the blend of tragedy and majesty that now characterizes Houston’s story. She is framed in close-up, her lips parted either in preparedness to sing or in the aftermath of having unleashed her soaring, immaculate voice, flawless as crystal, and the fact we cannot tell which of these moments is depicted hardly matters—all that does is that this face, this mouth, is the place from which once emanated something of such holy beauty that it’s easy to imagine Houston feeling heavy with the knowledge of her staggering ability, so that the sheen on her skin might signify exertion, but might also indicate that she is nervous.

Interestingly, Houston’s version of the anthem was not live, but prerecorded: in the video McKinniss uses as a reference, she is singing, but into a dead mic, making the performance itself a constructed simulacrum of the experience of seeing Whitney Houston sing, and the painting of this moment an effective simulacrum of that simulacrum. Watching the clip, it is easy to slip into the belief that what we’re seeing is reality, and that there is no space between the ecstatic vocal we are hearing and the one emerging from her body. This is perhaps the quality that makes a good celebrity, and makes good art, and makes good art about celebrities: it’s magic, the ability to cast a spell or an illusion without letting the one being hypnotized know that they’re being fooled.

McKinniss has often maintained that he paints swans because swans are, in their own way, celebrities, reasoning that their long affiliation with romance makes them so soppily familiar, and so loved, that they might as well be A-listers in their own right. It is this sentimentality, I think, which gives Star Spangled Banner its almost inexplicable power. How does one explain the presence of a feeling in a painting? The easiest thing to point to is the source material, which has been carefully selected to show Houston in a moment of potential and personal triumph; less easy to point to is the exact method with which McKinniss manages to capture the glimmer of vulnerability in her eyes, the wonder in the slackness of her mouth.

McKinniss’s painting brings to mind another artwork about an extremely famous, abundantly talented woman who met an untimely, tragic end—namely, Andy Warhol’s fading silkscreen of Marilyn Monroe, her tight smile and slender, embowed brows replicated and then ghosted, faintly, into nothing, into death. Painted in 1962, the year Monroe died from a barbiturate overdose, Marilyn Diptych is based on a publicity still from the Henry Hathaway 1953 film Niagara, and as with McKinniss’s choice of source material for his Whitney Houston painting, the decision to use this particular shot is charged. In Niagara, Marilyn plays a beautiful adulteress named Rose who, like Marilyn, is doomed, more or less from the film’s first frame, by her sexuality. She is hoping to abandon her jealous and violent husband, George, in favor of a lover who will keep her in the forefront of his mind like an especially catchy love song. Like Marilyn’s own second husband, the baseball player Joe DiMaggio, George has captured and attempted to domesticate a femme fatale, and cannot understand why marriage has not been enough to curb her appetite—the addition of a diamond to her finger not, as it turns out, being equal to a neutering or a lobotomy. Murder, as is often the case for a man like this, is decided on as the appropriate solution. When advertisements for Hathaway’s film boasted that it contained “the longest walk in cinematic history”—the walk being Marilyn’s undulating sway, captured on 116 unbroken feet of celluloid—they failed to mention that this walk was her character’s attempt to escape death. (Her imminent demise, of course, was what made the exercise so piquant and so titillating, whether or not audiences wanted to admit it to themselves.)

In taking Marilyn Monroe as she appeared circa Niagara—her first true lead, and a role that would help calcify her reputation as a woman who was just too hot to be allowed to live—Warhol forces us to rewind to the first reel of the picture, showing her vividly rendered in yolk yellow and rose pink, a slash of cerulean blue over her eyes, and then repeats the image until minor variations become clear. Marilyn’s career, too, was quite often a series of repeated images with minor variations, her astounding comic talent and nearly untapped ability to render delicate and trembling emotion typically forced into the unyielding shape of sexy airheads, gold-diggers, and girls with no aspirations outside marrying rich.

In the diptych’s second half, the same picture reappears in black and white, and rather than subtle dissimilitude, each new version is marked by an obvious degradation, as if it has been eroded or destroyed. A dark smudge, like a grave contusion, runs vertically through one column, and another is so highly contrasted that very little remains of the subject other than her most essential features, showing Marilyn Monroe as she might be spoofed in a newspaper cartoon, or used to advertise a beauty product.

“You’re a killer of art,” Willem de Kooning once supposedly slurred drunkenly at Andy Warhol at a party, making a familiar accusation before doubling down with something slightly different: “You’re a killer of beauty.” If the former is debatable, the latter is a curious accusation to level at a man most famous for loving surfaces, perfection, plastic. It is, though, an accurate reading of Marilyn Diptych, a work that is fundamentally about the public’s ravenous consumption of, and then destruction of, the beauty of an actress who was given little opportunity to prove what else she could provide. You’re a killer of beauty, the repeated, fading faces seem to say to those who look at them, the work’s tone far closer to that of the pieces that make up Warhol’s Death and Disaster series than that of his more conventional Hollywood portraits. Marilyn Diptych is Marilyn Monroe as a car wreck; as a jet crash; as a desolate electric chair. Like McKinniss’s Star Spangled Banner, it succeeds in its determination to depict something essential of its subject, making visible to the naked eye what we might previously only have been able to experience with the gut or the heart. Unlike McKinniss’s painting, what it communicates is not the radiance or the talent of the woman at its center, but the obverse: the insidious and unstoppable leeching of those qualities by an unfeeling industry, a media with a thirst for tragedy and a slavering audience, until what remains is so faint we can no longer perceive it as the image of a woman at all.

From Trophy Lives: On the Celebrity as an Art Object, out from MACK Books this month.

Philippa Snow is a critic and essayist. Her work has appeared in publications including Bookforum, Artforum, The Los Angeles Review of Books, ArtReview, Frieze, The White Review, Vogue, The Nation, The New Statesman, and The New Republic.March 14, 2024

At Miu Miu, in Paris

Photograph by Sophie Kemp.

Inside the Palais d’Iéna, it was dark-colored carpets and dark-colored walls. Chocolaty and rust-colored and warm. There was music that was playing and it was ambient, it was a shudder of synthesizers, it sounded like a womb. A loop of a video made by the Belgian American artist Cécile B. Evans was projected on screens set up on all sides of the room. I was not sure what to do during this time before the show started. I decided that a good thing to do while waiting for the fashion show to start was to orient myself in the space. I watched girls take selfies. I walked past the pit where photographers organized themselves, setting up their cameras. I was pacing, you might say; I was walking fast and with very little purpose.

Photographers swarmed actresses and actors walking in to the venue wearing full Miu Miu looks—things like teeny-tiny plaid shorts and a navy blue blouse with a puritan collar, or a red two-piece with a miniskirt that is kind of like an evil badminton uniform. Miu Miu girls and theys, I observed, are chic in a way that is like, I’m a pixie, I know my angles, I’m very charming about it. I have never felt like that in my life. Speaking of knowing your angles, I kept getting in the photographers’ shots. Sorry miss, do you mind moving, you’re in the shot, they said to me. I was happy to oblige. Sydney Sweeney walked in with her handlers, glamorously wearing sunglasses inside. Raf Simons, the legendary Belgian designer and co–creative director of Prada, got caught up in the photoshoot of a famous K-pop star, and a friend I was talking with swore she heard him say, Jesus Christ. I wrote a note in my phone that said: have u ever watched a really famous person being interviewed b4? its rlly weird lol. They enter a room and they are swarmed by a whole swath of people. How do they come up for air? I was having trouble with that at that moment, coming up for air.

I also felt, among other things, that I had a new appreciation for the music of Drake, the chanteuse. How does the song “Club Paradise” go again? No wonder why I feel awkward at this Fashion Week shit! No wonder why I keep fucking up the double-cheek kiss! Ha ha ha.

Photograph by Sophie Kemp.

I made it back to my seat. The Cécile B. Evans video installation morphed on the screens. The actress Guslagie Malanda, who starred in the movie Saint Omer, was in the video reading a kind of prose poem, and there were animations of flood water running through some bleachers and pixelated images of wind, a quasi psychedelic montage. The models entered the runway, one by one. They wore oversize leather gardening gloves and bubble skirts and nurse uniforms and perfect black dresses with cutouts on the sides and little leather sneakers and little pointy-toed Mary Janes. Wool overcoats and Gigi Hadid in (faux) furs. Int’l Klein blue stockings paired with a blazer that looked like it was maybe burnt orange suede—kind of the same color as a Goldfish snack cracker.

My favorite part was the middle section of the show—when the dresses became these sort of severe diner waitress / nurse outfits and the models were wearing fuck-me pearls, styled with little sunglasses that looked like the ones I remember my father wearing while manning the grill in the summer at my childhood home, rotating hot dogs with a big metal poker. Kind of a classic fashion-girl move—to deconstruct something classique by way of adding something masc to the mix. I was doing that too, honestly. I was wearing a beautiful, backless floor-length dress from a hip New York designer and also a disgusting Dickies jacket. I am not going to lie. I wore it because I wanted someone to notice me. Instead, I felt like a praying mantis with googly eyes.