The Paris Review's Blog, page 33

April 5, 2024

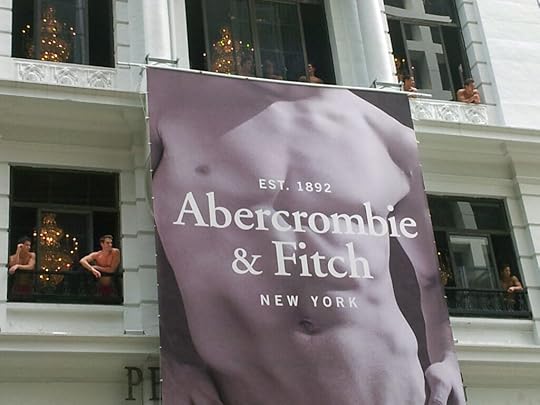

The Locker Room: An Abercrombie Dispatch

A&F Hong Kong store opening, 2012. 製作, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

In May of 2005, discontent with my job as a photo editor at a women’s magazine, I accepted an offer from a friend who did Bruce Weber’s casting to interview for a photo assistant position with him. At the time, Weber was doing the photography for Abercrombie & Fitch, working in tandem with the CEO, Mike Jeffries, to resurrect the brand. The photographs, in tonally rich black-and-white or vivid color, showed cheerful, cartoonishly chiseled, (mostly) white people frolicking, washing dogs, and generally playing grab-ass. They hearkened back to the scrubbed cleanliness of the fifties (with a sprinkle of Leni Riefenstahl); everybody looked like they had gotten a haircut the morning of the shoot. My friend described the photo assistants as a group of young men who traveled the world with Weber, making big money. On breaks, they’d show off for the models by playing shirtless football on the beach or jumping off cliffs into narrow pools of water. This seemed better than sitting at my desk arranging catering or reassuring Missy Elliott’s team that the mansion where we were going to photograph her did in fact have air-conditioning.

The day of my interview, I put on a gray sweater, a striped oxford, and A.P.C. New Standards. I wanted to look tidy, but not too uptight. As requested by the first assistant, I brought a CD of my pictures to demonstrate my photography skills. The office was open plan, with a large round table in the middle and twenty or so people milling about. Weber, a bandanna-ed Santa Claus type, shuffled around chatting with his employees, trailed by a pack of identical golden retrievers. I sat down with Weber’s first assistant, whom I’ll call Sean. Sean told me he had been photographed by Bruce (we kept talking about “Bruce” as if he were imaginary, even though he was standing a few feet away) when he was a NCAA wrestler. He had close-cropped blond hair, and the lingering musculature of a former athlete (I later came across Weber’s pictures of him and his teammates in the locker room, showering cheerfully). The job, as Sean described it, was to hand Weber an unceasing flow of Pentax 6×7 medium-format cameras that had been preloaded with film, focused and set to the proper exposure so he could photograph continuously without technical fuss.

We clicked through the CD of my photographs and he complimented my use of color. While we talked, I looked around the office at the other assistants, a variety pack of hunks. Among them were an Ashton Kutcher type, a Patrick Bateman type, and the all-American boy interviewing me. Wrapping up the interview, he told me that they needed to take a Polaroid because Bruce “needed to be able to put a face to the name.” I stood up and posed for the Polaroid, made with a vintage land camera. I knew this moment was to be my undoing. I am under six feet and, according to my sister’s 23andMe, our family is 99.3 percent Ashkenazi Jew. This type seemed absent from the roster. I suspected I was not there to fill that void. We shook hands, and I got in the elevator and left. After a few calls over the next few weeks, things tapered off and I never heard from them again. Sometimes I wonder if they saved those Polaroids, and if it would be possible for me to get mine back.

Shortly after my interview, an Abercrombie flagship store opened on Fifth Avenue and Fifty-Sixth Street. Aside from the overpowering stench of their cologne Fierce (an “irresistible blend of marine breeze, sandalwood, musk and wood notes”) and the moody lighting, both A&F retail signatures, the Fifth Avenue store was notable for its centerpiece, a mural called The Locker Room. This was painted by the artist Mark Beard, under one of his many aliases, Bruce Sargeant. (The name Bruce is inexplicably historically associated with being gay; for example, when the Incredible Hulk comics were adapted for television, Bruce Banner’s name was considered too fey, and changed to David.) The mural depicts an early-twentieth-century gym class in a style that evokes Thomas Eakins: young men in baggy loincloths or singlets, doing calisthenics and climbing ropes. Like Weber’s flawless crew of assistants, the romantically rendered athletes were perfect manifestations of the hairless-and-wholesome masculinity defined by his work for A&F. Homoerotic, suggestive, but never explicit. You could be spotting your pal as he climbed a rope or playfully pulling your buddy’s underwear down all in good fun! The photos from the store’s opening show the live version: groups of unnamed shirtless guys carrying around the (blond, rosy-cheeked) model Heather Lang, chastely kissing her on the cheek.

These festive days are now over. In July of 2023, Abercrombie closed its Fifth Avenue flagship and converted the Hollister (a sister brand) down the block to replace it. The CEO, Fran Horowitz, said of the consolidation: “It’s 180 degrees from the cavernous, dark club feeling of the past … This is the antithesis of that.” In the decades between my ill-fated interview and the store’s closing, Abercrombie saw a slew of sexual abuse scandals involving Weber and Jeffries. Weber was accused of molesting male models while photographing them (sticking his fingers in their mouths, et cetera) and settled their lawsuits for a undisclosed amounts. The allegations against Jeffries (and his romantic partner) involve a middleman named James Jacobson, recognizable by the snakeskin patch he wears over his nose, possibly due to a botched plastic surgery. Jacobson was said to have recruited hundreds of young men for Jeffries and coerced them into sexual favors by tantalizing them with the possibility of modeling careers. Very Epstein-like indeed, and coincidentally (or not?) Epstein was the money manager for Les Wexner, the man who not only brought Jeffries on to A&F but once owned Victoria’s Secret as well. Wexner (along with Dov Charney) was the architect of the New American Horniness that sprung up in the aughts and supposedly died with #MeToo, Hikikomori Zoomers, and the pandemic.

On a recent trip to Midtown with some time to kill, I found myself looking for the A&F store to revisit Sargeant’s mural. This was when I realized the store had moved, and that the mural had been uninstalled in 2018. (It was reconstructed in Beard’s studio, before being cut up into smaller paintings and shown at the Carrie Haddad Gallery.) The new A&F store has an open plan, ficuses, and bright overhead lights. The only art is bland travel photography. I wandered around, taking inventory of a tepid mix of preppy basics, Nirvana kids’ T-shirts for the children of Gen Xers, and a conspicuous lack of A&F logos. The strategy is working: the company’s stock went up 300 percent in 2023, their scandalous past is long gone. And Bruce? He seems to be doing fine. In a recent Instagram post, he shared a photograph of seven golden retrievers, including a new puppy, who, after much debate, was christened Spirit Bear.

A&F Hong Kong store opening, 2012. 製作, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

Asha Schechter is an artist and writer living in New York City.

April 4, 2024

Making of a Poem: Eliot Weinberger on “The Ceaseless Murmuring of Innumerable Bees”

Anne Noble, The Dead Bee Portraits #2. Courtesy of the artist.

For our series Making of a Poem, we’re asking poets to dissect the poems they’ve published in our pages. Eliot Weinberger’s “The Ceaseless Murmuring of Innumerable Bees” appears in our new Spring issue, no. 247.

How did this poem start for you? Was it with an image, an idea, a phrase, or something else?

First, I doubt it qualifies as a poem. It starts out as a simulacrum of a poem and then turns into an essay—or at least what I consider to be an essay, which is sometimes mistaken for a poem or a prose poem.

Its origin was a letter I received out of the blue from a photographer in Aotearoa/New Zealand, Anne Noble, whose work includes portraits of dead bees, some done with such devices as electron microscopes and 3D printers. She knew my collaboration with the Maori painter Shane Cotton (the essay “The Ghosts of Birds”) and asked me to write a text for a catalog of her photographs she was preparing.

At the time I wasn’t able to help, but a few years later—long after the catalog had been published—I found it was finally the moment to get to the bees.

Were you thinking of any other poems or works of art while you wrote it?

I spent a long time with bee-related writings and artworks, but wasn’t particularly thinking then of works that had no bees. However, my permanent models for an unadorned narrative are the Icelandic sagas and classical Chinese works called anomaly accounts (zhiguai), and my models for the condensation of large amounts of historical information are Charles Reznikoff and, in certain poems, Lorine Niedecker.

How did you come up with the title for this essay?

It comes from a line of Tennyson (“And murmuring of innumerable bees”) that is frequently given as the perfect example of onomatopoeia. (Though it’s an old joke that the same effect could be achieved with “and murdering of innumerable beeves.”) I added “ceaseless,” as there are a lot of bees from all ages flying through the lines in an incessant drone.

How did writing the first draft feel to you? Did it come easily, or was it difficult to write? How about the second draft? The third? How many drafts were there and what were the primary differences between them?

I have a strange way of writing. Most writers tend to write a great deal and then cut much of it out. I start with a few lines or a paragraph, not necessarily the beginning, and keep adding to the middle, beginning, or end. I very rarely delete a whole line or sentence, though I’m continually replacing words in them. Everything goes through many drafts, and the essay grows organically, like a crystal, even if the result is not especially crystalline.

When did you know this piece was finished? Were you right about that? Is it finished, after all?

There comes a moment when the writing achieves a state of rest and just sits there like a rock. Then you move on to the next thing.

I’ve never rewritten old things, but I have expanded them. My whole book Angels & Saints is an expansion of a one-paragraph essay I had written twenty years before—but I didn’t change the original paragraph.

Did you show your drafts to other writers or friends or confidants? If so, what did they say?

I’ve never shown an unfinished manuscript to anyone, and the finished ones generally go directly to the editor or publisher involved. And then I very rarely allow any editorial changes, except for the correction of genuine mistakes. You might say I have an authority problem, but I’m the author.

What was the challenge of this particular piece?

I tend to write about things I know nothing about, and there is of course a vast amount published on any given topic. Eventually I have to abandon further research, accept my ignorance, and start writing. After all, I’m trying to create a literary text, not produce an academic article.

In this case, early on I decided to avoid two enormous subjects connected to bees—honey and their current worldwide extermination. Since the poem/essay is largely about bees and death, war, politics, and religion, I thought the huge world around honey would be a distraction. And with death hanging over it, there was no need to get into the specifics of the present disaster, which is implicit.

For me, writing is not a “challenge,” in the sense of some sort of guy mano a mano with inner demons, ancestral masters, silence, or the blank page. There are people who just like their job.

Eliot Weinberger’s most recent books are Angels & Saints and The Life of Tu Fu, both published by New Directions.

April 3, 2024

A Sense of Agency: A Conversation with Lauren Oyler

Photograph by Carleen Coulter.

The one time I met Lauren Oyler in person was in New York in the spring of 2018. I had been closely following her work as a critic and admired her intelligence and fearlessness. That exuberant night, she sat mostly quietly, with a look of anger, through a long evening at a bar, which ended late, outside a pizza restaurant, over greasy slices. She was the girlfriend of a friend of mine, who was the reason I was there. The next day, I learned that after they had gone home, she had dumped him. All of this made a deep impression on me. Not pretending to be having a good time. Some sort of power she embodied, just sitting there stonily. I have a terrible memory, but I remember that night—and her at the center of it—so vividly.

That spring, it seemed like everyone was talking about her hyperarticulate critiques of Roxane Gay, Greta Gerwig, and Zadie Smith. She was unafraid to use the full force of her critical eye to scrutinize even those artists who were mostly widely praised. Several weeks after we met, she wrote a defense of my novel Motherhood in The Baffler, responding to various prominent American female critics who had negatively reviewed the book. I wrote to thank her, and in the years since, we developed a correspondence and a friendship.

Three years ago, she published her first novel, Fake Accounts, about a young woman who flees to Berlin and interrogates her relationships and herself, while a Greek chorus of ex-boyfriends occasionally chimes in with corrections to her self-mythology.Her new book of essays, No Judgment, contains six pieces, all written specifically for the book. She thinks about the history of criticism in the form of star ratings on Goodreads; about gossip and anxiety. I was struck by the pleasure vibrating from these essays; the evident joy she takes, and freedom she feels, in writing and thinking in the essay form. I was eager to ask her certain questions outside the structure of our friendship. She is a critic I admire, with strengths that feel different from my own; in other words, someone to learn from.

INTERVIEWER

I want to begin by asking you generally about the pleasures of writing—when did you discover them?

LAUREN OYLER

The first things I remember writing were journals and daily writing assignments in school, and then there were the private blogs I kept as a teenager. I think I wrote those online just because I preferred to write on the computer as soon as that was available. I was always a good typist and it was the dawn of the social internet, but I kept the blogs locked, or whatever we used to say, so the point was just that I wanted to be able to write fast and emotionally while talking to people on AIM at the same time. I don’t know if I found the pleasures of writing uncomplicated, even at the time—writing was a compensation prize for the various anxieties and miseries I experienced, and I kind of still feel that way. I wanted to be a painter, which I am not naturally talented at, but I always had a natural talent for writing and a unique relationship to language, and for some reason I kept developing it. You’re not supposed to say this—you’re supposed to say, “I am so lucky to have a career, I am no better than anyone else.” I know many very naturally talented people who aren’t ambitious, and I admire and sometimes envy them, but I have been very ambitious since I was fourteen years old. I don’t know why.

INTERVIEWER

How would you describe what these pleasures are for you, and how have you cultivated them since you first discovered writing, if that is the right word, cultivated?

OYLER

The pleasures are in problem-solving—particularly in criticism, where the problem is often how to avoid saying all the things you absolutely do not mean and instead to express something that you don’t necessarily know how to articulate at the outset of a piece—and then in making something new, despite the odds. I find formal experimentation almost euphoric when it works out, and of course there’s always the pleasure in finding the right word, and the satisfaction of composing something beautiful and/or interesting, whether it’s a sentence or a paragraph or a transition. But overall the pleasure is often about relief—wanting to write about a particular idea or work and then finally doing it, or wanting to explain something or understand something, and then finally getting there, more or less, through writing.

If cultivate is the right word, it would mean that I wrote all the time, in increasingly professionalized settings, so that having to earn money became less of a problem, and I studied others who do or have done it, even if all of this has often been painful or difficult, and even if at times I wasn’t even aware that I was doing it. I’ve also always pushed myself to do things that are uncomfortable for me as a writer, things that I might dread but that I know are good for me. I cannot remember the last time I didn’t cry while writing a magazine piece, for example, but I do them anyway. Almost every boyfriend I’ve ever had has earnestly told me many times that I need to stop doing magazine pieces because they upset me so much, and that I don’t even make that much money from them and I should focus on fiction because that’s what I love to write, and I really appreciate this, but I will not stop writing magazine pieces until I die, or until the industry itself does. I don’t know why. I love magazines. Career-wise, I’ve also learned how to conduct myself with editors. Until recently, when I’ve become more comfortable pushing back, I would take edits on magazine pieces that I profoundly disagreed with—this is usually the source of the upset—and this has meant I’ve always gotten more work, more opportunities to “cultivate” my writing. And until recently, I had to do many different kinds of writing and editing—I copyedited so much—to earn money, which helped me develop my strange relationship to language even more, the high-low, ironic-sincere register that many people are wrong to hate.

INTERVIEWER

Please say more. Why do they hate it and why are they wrong to?

OYLER

I think a lot of people want to be able to easily classify you. So if I’m using the word prelapsarian and the phrase “that sucks” in the same paragraph, or whatever—and saying “or whatever,” in order to create the effect of conversational speech—they don’t know where to place me. Or they say I’m strategically developing a persona, because they think no one could possibly be like this, because they know only one kind of person and they think everyone is exactly like them. Does it matter who I am? I’d argue that, unfortunately, today, yes, it often does.

Of course, there’s a tradition of blending slang with high-flown language in American writing in particular, and I go on and on about David Foster Wallace, but people didn’t like it when he did it either. I’m coming at it from a different angle—I grew up working-class, speaking a fairly specific regional American English, and while my family are very smart, they aren’t “intellectuals”—and I also work with argot from the teen’s and women’s magazines and internet writing that I grew up reading. I think some people don’t realize that I’m doing this on purpose; when I’m writing book criticism, I try to treat everything in a text as intentional, or under the author’s control, even if an effect is obviously the result of laziness, like “or whatever,” and I do wish more critics would do that. You can still write a pan that way—actually, pans that treat an author as fundamentally responsible for her work are the only ones that really stick. I love language and I want to use as much of it as possible, and I refuse to deny that one side or the other of it—as in “high-low”—exists. This is why I love novels like Mating and why I love Nabokov, because they show you so many new ways to use language. I would like my writing to do that for people, if they are willing to see it.

INTERVIEWER

One of the things that most excited me about your book was the clear pleasure you get from thinking in the form of an essay. Many people write essays because that’s the form they’re paid to think in—they’ve been commissioned to write something—but it struck me that the essay might be your ideal form. What is it about the essay form that you like so much, or that makes it so particularly useful for you?

OYLER

As I say in the book, my favorite form, to read and to write, is the novel. But I think that’s why I have more fun writing essays—there’s much less pressure, and I don’t expect so much from them. I don’t have an idea in my mind of how an essay should look or feel, what kind of texture it should have, whereas many of us have strong ideas about what a novel is and should be. You could say I don’t care as much about essays, which is not to say I don’t want them to be “good,” or rigorous, but I don’t care about cleaning up the edges so much, and that means my thinking can be more flexible in that form. There’s something about the novel that is always straining for timelessness, but essays can be more spontaneous and contemporary.

INTERVIEWER

Are there essayists you read when you were growing up who inspired your own work? Or critics in the contemporary world whose work you regularly seek out?

OYLER

I get a lot of permission, as they might say in therapy, from rereading my favorite essayists. I reread in an almost desperate way while writing essays—like, please, please, Ellen Willis, help me—and something that always strikes me when doing this kind of intensive purposeful rereading is how messy the great works of the past are. Elizabeth Hardwick—you know, she often doesn’t totally make sense, and it doesn’t really matter. David Foster Wallace—very repetitive, very tedious, often wrong. Who cares? I want an amazing paragraph, I want a sudden moment of clarity, I want an unusual transition or connection. It’s the trade-off you make for thinking that feels alive, and it’s one I’m happy to make.

You and I have talked about the frustrations of writing for magazines. For a piece of criticism, many magazines want you to have a thesis statement in neon lights, and that is something I’ve been trying to actively avoid doing. I think it’s just really unrealistic—both in terms of the craft of writing and in terms of how unwieldy the world actually is—and often not very fun to read. A good essay will have many arguments in it. The arguments in the essays I write accrue—they’re almost narrative, in that you start in one place and end up somewhere else. With a thesis statement, you have nowhere to go, or you start at the end and go in a circle.

INTERVIEWER

One thing that distressed me in your collection was the sense that someone as obviously intellectual as you are nevertheless does not carry around in her head a library of references and quotes from decades of reading and remembering what she read. It seemed clear that many of your references came from Google Books searches or internet searches. It made me feel the relative shallowness of the contemporary mind that many of us share, compared to the intellectuals of the past who had a world of references inside them. Is this something you feel, or are bothered about in any way?

OYLER

Let’s first please allow that I am thirty-three years old, so I’ve had only about a decade of reading that actually counts. It’s probably true that I read the way a “digital native” reads, which is to say broadly and not as deeply, because of the way our technologies of reading work. But I don’t know if you’re right that many of my references come from, like, bopping around Wikipedia at 2 A.M., which is not something I do. I do not memorize things, no, but I think it’s important to have a penumbra of references that you can use to make interesting moves, particularly in essays. I think it might seem that my references come from googling in part because I’ll often narrativize a somewhat base style of research—I’ll say things like “I was googling around and found this New York Times article about whatever”—in order to represent what life is like now, where you google around. But actually in many cases it may be that I encountered a text many years ago, remembered it vaguely, and then reproduced it with easily fact-checked internet research when it became useful to me. But why is that bad? The Google Book is not any different from the actual book.

And the internet is very useful for starting research—you look up some broad topic, find sources linked at the end of the Wikipedia article, go to those sources, find sources from those sources, and so on. I don’t see anything wrong with the first part as long as you do the second part rigorously. The internet is a tool and it’s with us forever, so we might as well harness its power for good when we can.

INTERVIEWER

I wonder, since not all writers read reviews of their work, what do you hope to learn by reading reviews of your own work?

OYLER

If I will be able to sell my next book, ha ha. I don’t think reviews actually contain this information, but these are what the stakes are for me. I also hope to learn what I hope to learn by reading reviews of anyone’s work, which is, What are the values of the moment? For better or worse, I’m attracted to what “people are talking about,” to the issues of the day, and if I often disagree with what “people” are saying, that’s fine, because I get a lot of ideas that way. The essays on autofiction and vulnerability in the collection are the result of having read both a lot of book reviews and a lot of reviews of my own work.

INTERVIEWER

I once wrote a negative review of a book in my early twenties, and for years I felt terrible about it. I decided that, from then on, I’d only write about books I liked or loved. I think this means I’m not actually a critic—I don’t have the stomach for it. I have recently been enjoying Merve Emre’s podcast, The Critic and Her Publics, in which she conducts interviews with critics before an audience of students and has the critic make a judgment of something on the spot. I thought her interview with Andrea Long Chu was especially compelling—Long Chu talked about how her harsher book reviews come out of “disappointment.” In looking back at some of the reviews that made your name, would you say that the motivating spirit was disappointment or something else?

OYLER

I agree with her that there is definitely an engine of disappointment in my earlier negative pieces. For me it might be a class thing. I taught myself to like what I like, it didn’t come naturally to me, so when I encountered writers who gesture toward the “literary” while also pandering to their idea of “the masses”—“the masses” that I am from—it would make me really mad. Most of the negative reviews I wrote were also assigned to me, so they also probably involved resentment that I was being asked to spend my time this way. I could have been stockpiling references!

INTERVIEWER

I am impressed by your ability to actually criticize, in depth and in public, people who are alive today. Can you explain what qualities you possess that allow you to do this?

OYLER

Confidence, certainly, but I don’t know where that comes from, and I don’t like to use the word that often because it implies little connection to the convictions that might produce the confidence. I’m confident in my criticism because I am pretty certain of both my interpretations and my stylistic choices by the time I write. A sense of agency? A democratic sensibility, or maybe just a sense of proportion? I don’t think many of the people who call themselves writers actually care about literary form or style or ideas expressed in writing. They care about being called writers. So my attitude about this is, fine, if you want to be a writer, I will treat you like one—I will assess your writing on the level of form and style and idea. I’m as qualified to do this as anyone else, and anyone else is welcome to do it to me. If you’re a serious writer, you should be able to withstand criticism and determine which criticism is legitimate and which criticism is made in bad faith, even if it stings.

INTERVIEWER

I have been teaching this year, and one thing I am noticing is that young people who want to be writers are drawn to writing in genres that my peers, when we were their age, were less likely to have dreamed of writing in—science fiction, romance, fantasy. We all wanted to produce Literature, classics, like the greats—a category my students perhaps rightly deny, or that to them is merely another genre. One of the students theorized that this was because of the weakening power of the gatekeepers, and another said it was because people have shorter attention spans, so a writer who wants to win an audience should put their ideas into a genre that seems easy and that people already love. Do you have any thoughts about this?

OYLER

I think gatekeepers still have power, but they don’t necessarily have as much money as they used to—or at least they say they don’t. They don’t dictate what sells. They chase what sells. So maybe you could say they have less power, inasmuch as there is now a populist swell of data that guides their decisions. And I think that for many people of the younger generations, making money signifies worth in a way that it didn’t for Gen X. Also, for younger generations, popularity signifies money, which signifies worth. This isn’t only because they’re or we’re shallow—it’s because of the deteriorating conditions of life in the U.S. and the UK, where it costs a lot of money to live barely comfortably. People want to have a nice life.

All that said, it may be that it’s also harder to hide from what’s popular now. There is also a widespread conflation of identity, and class, with what one likes, so you’re not supposed to be a snob about culture—you can’t flat-out reject Beyoncé or Marvel movies, or say you only read the greats—because that would mean you’re rich and out of touch, a coastal elite. It must be, too, that these kids like what writing sci-fi and fantasy would have to say about them, but I do not know what desirable qualities writing sci-fi and fantasy would represent …

INTERVIEWER

If you have a biggest fear for the culture—I don’t mean environmental catastrophe, I mean the world of our minds all together—what is it?

OYLER

I don’t know if it’s a biggest fear, but I think everything is really boring right now. I find it hard to muster the energy to write about contemporary culture anymore. There is also a lot of droning competence—work that is pretty good but that lacks a sense of purpose or strangeness, or any reason to actually look at it. Nor does any of this work seem to represent some horrible trend or tendency that it’s nevertheless fruitful to discuss, as bad writers of the very recent past did. Everyone seems to be going through the motions.

INTERVIEWER

I sometimes feel and can’t believe that I have such a good life, and I wonder, do you feel you have a good life?

OYLER

This is a good question. I’m very proud of my life, which is wonderful and which I fear losing or damaging. I’m very, very proud of my relationships and the way I travel. I’m proud of the taste I’ve developed, not just in books but in art and film and music, and that I have found people both in my life and through my work to share it with. I love my writing, which has gotten easier for me in the past couple of years and accomplishes what I want it to accomplish.

I just read your interview with Phyllis Rose in Granta, and you asked her a similar kind of question—whether her great second marriage was “luck.” It makes sense to me that you’d ask these kinds of questions—so much of your career has been about asking what a life should look like. On a political level, everyone deserves a good life that they must work really hard to lose or truly damage. I feel that I have worked, sometimes hard, to get and maintain what good things I have, given the advantages and disadvantages of the circumstances I was born and bred into, and I believe it is my responsibility to make the best and most of my life, precisely because there are billions of people in the world who also deserve to have the things I have. In general, one person’s sacrifice of moderate goodness—or, worse, any self-aggrandizing performance of guilt—does not make the lives of suffering people any better. That said, I’m against the rich, who should have to sacrifice much more, and I’m for radical political statements involving self-sacrifice or self-harm.

But I’m more interested in this question as it relates to the social world. When I say I’m very, very proud of my relationships, I mean that I try to be a loyal and transparent friend, I pay close attention to people and remember what they tell me, I am open and intimate while trying not to burden people with my problems, I apologize when I do something wrong—only when I’m actually sorry, though—and I am pretty much always fun and interesting to be around, possibly to my detriment. If I were a manipulative asshole, I would say I deserved to lose those friends. Like I said, I have a sense of agency.

INTERVIEWER

Finally, what is your favorite flavor of ice cream?

OYLER

Mint chocolate chip.

INTERVIEWER

Me too!

OYLER

If they don’t have it, I get whatever has the most ingredients. I’m a maximalist.

Sheila Heti is the author of eleven books, including Pure Colour, Motherhood, How Should a Person Be?, and, most recently, Alphabetical Diaries. She is the former interviews editor of The Believer, and has interviewed such writers and artists as Elena Ferrante, Joan Didion, Agnès Varda, and Dave Hickey.

April 2, 2024

Inheritance

Hebe Uhart. Photograph by Agustina Fernández.

Hebe Uhart had a unique way of looking—a power of observation that was streaked with humor, but which above all spoke to her tremendous curiosity. Uhart, a prolific Argentine writer of novels, short stories, and travel logs, died in 2018. “In the last years of her life, Hebe Uhart read as much fiction as nonfiction, but she preferred writing crónicas, she used to say, because she felt that what the world had to offer was more interesting than her own experience or imagination,” writes Mariana Enríquez in an introduction to a newly translated volume of these crónicas, which will be published in May by Archipelago Books. At the Review, where we published one of Uhart’s short stories posthumously in 2019, we will be publishing a series of these crónicas in the coming months. Read the first in the series here.

When I used to take walks along Bulnes Street and Santa Fe Avenue, a certain boutique would catch my eye. It always displayed the same series of colors: beige, dusty rose, baby blue—a small array of colors, and always the same ones on rotation, never a red or a yellow. Everything behind the display window was elegant but hidden in shadows; this included the owner, who seemed determined to fulfill her duties despite having so few customers. The owner’s silent manner and desire to pass incognito (as if showing one’s face were distasteful) led me, in one way or another, to this idea: she must have inherited her taste in clothing from her mother, and she was making sure to carry on its legacy. Well done, well done on that display window, but with so few customers, the shop was doomed.

On Corrientes Avenue, at the corner of Salguero, there is another window displaying sweaters paired with little vests (for when it gets chilly). Every week, the owners debut a new line of muted colors: grayish blue, blush, timid yellow. Delicate T-shirts that seem to say: This is the way things are. The garments are always the same shape and length; every week, the owners change the color scheme. It occurs to me that this taste is also inherited, passed down from a time when women dressed to please rather than to offend and when dialogues unfolded like this:

“Go ahead, dear.”

“You first—I insist.”

“How kind of you.”

“Let’s catch up, darling.”

As a friend of mine says, such women used to talk as if they had made a pact at birth. Nobody goes into that shop either; they go into the shop next door that sells skirts with studded red flowers, asymmetrical ones, others with ruffles. Because nobody cares about offending others these days; nobody cares much about anyone. Which is why the vendors at the shop with the muted colors don’t mind if their clothes sell or not; passersby call their sweaters “dainty little things.” One is inspired to buy those outfits and dress up in a different color every week, like the display window, to harmonize the soul, to have things change without really changing, to perform a ritual that ensures eternity.

Some dogs can be inherited, as can photos, promises, and schedules. The way one decorates one’s house is inherited, too. I once visited a house where everything was smooth and shiny as a bocce ball, not a painting or flower vase in sight. I hovered from room to room like a low-flying plane. This was because, in another house, the department of hygiene had come to get rid of some rats, bats, or kissing bugs. These problems no longer existed, but the fear survived.

In houses full of little folders from bygone days, the ancestors are present: they talk to each other, folder to folder, handkerchief to the doll on the bed. Certain ideologies are inherited as well. Some families are radicals, Peronists; others are communists. As much as they might deny the ideologies of their ancestors, many will inherit their customs and tastes. Families that come from the radical tradition tend to have good taste. They do not flaunt their wealth; they tend to be discreet about the real estate they own, critique mindless spending because it’s unbecoming, and if they are professionals, let’s say doctors or dentists, they have paintings of horses galloping in the office, but it’s always a discreet gallop, nothing out of control. In Peronist families, whims and desires are more permissible. If a member of the family has a craving for hot chocolate at four in the morning or spends all of their savings on meeting Mickey Mouse at Disneyland or shoots down loquats with a gun, the other family members will not openly disapprove, because they are not inclined to make value judgments—they are not constrained by the Platonic Form of the Good. The most curious houses belong to the descendants of communist resistance fighters. Even if these heirs no longer fight or say they don’t give a damn about politics, their homes contain the traces of revolutionary spirit. They cannot bear to dress sharp or get dolled up because that would mean assuming a privilege that is at odds with the proletariat. Their houses contain many old books, which were passed on to them by their grandfather; they don’t throw or give them away—it would be like throwing or giving away their grandfather. Nor do they use a feather duster to clean; it would be like feather-dusting grandfather.

They do not buy new chairs, because this would mean participating in consumerist culture—a frivolity that would distract them from their studies, from reading. It is permissible, of course, to buy new books, and radicals do so with a mischievous gesture, as if they have just ducked out of their grandfather’s lecture. They flaunt a new book as a Peronist would flaunt a new car.

Sometimes an inherited saying dances around in your head, one you have always hated. It is a reminder of the past, when young people would shed their coats in the first days of spring, and their elders would say, “Winter isn’t done with us yet.” And you were annoyed because that comment seemed to wish for, to beckon the cold. But now you find yourself saying, “Winter isn’t done with us yet.”

Anna Vilner’s translation of “Inheritance” will appear in a forthcoming collection of Hebe Uhart’s crónicas, A Question of Belonging, to be published by Archipelago Books in May 2024. The original Spanish version was collected in Uhart‘s Crónicas completas, published by Adriana Hidalgo.

March 29, 2024

I Love You, Maradona

Photograph by Rachel Connolly.

While reading Maradona’s autobiography this past winter, I found that every few pages I would whisper or write in the margins, “I love you, Maradona.” Sadness crept up on me as I turned to the last chapter, and it intensified to heartbreak when I read its first lines: “They say I can’t keep quiet, that I talk about everything, and it’s true. They say I fell out with the Pope. It’s true.” I was devastated to be leaving Maradona’s world and returning to the ordinary one, where nobody ever picks a fight with the Pope.

I started reading El Diego: The Autobiography of the World’s Greatest Footballer, ghostwritten by Marcela Mora y Araujo, on the basis of a recommendation by an editor I have liked working with. He said reading it was the most fun he’d had with a book. I came to El Diego with basically no knowledge of Maradona or even of soccer. I would have said I hated soccer actually. I hate the buzzing noise the crowds make on the TV. But from the very first page I found Maradona’s voice so addictive and original that reading El Diego felt like falling in love.

Maradona’s skirmish with the Pope goes the way of much else in the book. Because of his extraordinary talents and global fame, Maradona is invited to the Vatican with his family. The Pope gives each of them a rosary to say, and he tells Maradona that he has been given a special one. Maradona checks with his mother and discovers that they have the same rosary. He goes back to confront the Pope and is outraged when the Pope pats him on the back and carries on walking.

“Total lack of respect!” Maradona fumes. “It’s why I’ve got angry with so many people: because they are two-faced, because they say one thing here and then another thing there, because they’d stab you in the back, because they lie. If I were to talk about all the people I’ve fallen out with over the years, I’d need one of those encyclopedias, there would be volumes.”

Whether it be FIFA, money-hungry managers, angry fans, the Mafia, drug tests, or the tabloids, Maradona never takes anything lying down. He stews and stews, and this fuels him to play better and better soccer. There is an Argentinean word Maradona uses for this: bronca. Mora y Araujo explains, in an introduction in which she lovingly details the difficulties of putting Maradona’s unique voice down on the page, that this basically means “fury, hatred, resentment, bitter discontent.” But the difficulty of choosing a translation left her to simply leave bronca, and many of Maradona’s other favorite catchphrases, as they were. The result is a narrative voice which is totally distinct, and an overall energy out of sync with the pristine, restrained public image most celebrities seek to cultivate, especially in the social media age.

Maradona first learned to play soccer on the streets of Villa Fiorito, the extremely poor city on the outskirts of Buenos Aires where he was born. He played all day in the blazing heat and then when the sun went down too. Early on in the book he says: “When I hear someone going on about how in such and such a stadium there’s no light, I think: I played in the dark, you son of a bitch!”

I still don’t know enough about soccer to verify my impression that he is one of the greatest soccer players ever. But Wikipedia asserts this too. El Diego tells the story of his extraordinary rise through the world of small, local kids’ clubs to a glittering career which involved World Cups (one of which he captained Argentina for), a transformative stint for the Italian team Napoli, setting the world record for transfer fees twice, scoring a famous handball goal against England, and lots of other things I don’t really understand properly but felt enormously gripped by.

It’s an incredible life story, shadowed by, as well as his constant fights, a cocaine habit and a string of extramarital dalliances. But mostly I was gripped by the way he tells it. At one point, when FIFA bans him from a match, he says: “My legs had been cut off, my soul had been destroyed.”

I started El Diego in the airport, on my way back to Belfast for Christmas. A young man on my flight pointed at my book and asked me what I was reading. (I discovered over the next few weeks that reading the book in public places was a magnet for men.) I showed him the cover.

He said: Oh yeah I thought it said Maradona. You like football?

I said: Oh no I don’t know anything about football.

He said: Why are you reading it then?

At the time I told him it was because I wanted to read something different from what I usually read. If he’d asked me the same thing when I finished it, I would have said it’s not really about football. It’s about being in love. It’s about the little guy against the big guy, I would have declared. And believing in something. And respect. It’s about having a sense of who you are.

If the young man had not politely excused himself by this point, I would have told him I sent photographs of many pages of the book to everyone I know who has a slightly bad personality. Grotty, unwholesome types who have dysfunctional relationships with substances. People who have problems with authority and are incapable of being obsequious and are always getting into trouble. People who take things too personally. Which is to say, I sent pages to all the people I love the most in the world, saying: You need to read this.

I can’t really talk about El Diego without sounding like a fanatic. I think this can be true of any book or piece of art which we find resonates particularly with us. Enthusiasm can come off as a little crazed. Here especially, I think, because I am surprised at how much it did resonate, given that soccer is a world I previously felt I couldn’t relate to much at all.

Now that I have discovered Maradona as a thirty-year-old, decades after the rest of the world, I notice he pops up in places where I’d never noticed him before. In the Italian café I eat in around once a week I noticed a Maradona shirt behind the counter.

That’s Maradona, I said to the owner. He looked at me like I’d just asked him if he had heard of pasta.

Yes, he said slowly. He was the best. I nodded and sat down to eat. Soccer, I noticed, was on TV in the background, as it probably had been on all of my visits.

Rachel Connolly is a writer from Belfast. She has written essays and criticism for the New York Times Magazine, New York Magazine, the Guardian and others. Her short fiction has been published in The Stinging Fly and Granta. Her first novel, Lazy City, was published in 2023.

March 28, 2024

Syllabus: Diaries

Lahiri at Boston University, where she attended graduate school, in 1997.

“I’ve kept [a journal] for decades—it’s the font of all my writing,” Jhumpa Lahiri told Francesco Pacifico in her Art of Fiction interview, which appears in the new Spring issue of The Paris Review. “That mode, which involves carving out a space in which no one is watching or listening, is how I’ve always operated.” She described a class she recently taught at Barnard on the diary, and we asked her for her syllabus for our ongoing series; hers includes a wide range of texts which all carve out that particular, intimate space.

Course description

What inspires a writer to keep a diary, and how does reading a diary enhance our appreciation of the writer’s creative journey? How do we approach reading texts that were perhaps never intended to be published or read by others? What does keeping a diary teach us about dialogue and description, or about creating character and plot, about narrating the passage of time? How is a diary distinct from autofiction? In this workshop we will evaluate literary diaries—an intrinsically fluid genre—not only as autobiographical commentaries but as incubators of self-knowledge, experimentation, and intimate engagement with other texts. We will also read works in which the diary serves as a narrative device, blurring distinctions between confession and invention, and complicating the relationship between fact and fiction. Readings will serve as inspiration for establishing, appreciating, and cultivating this writerly practice.

Schedule

Week 1: Susan Sontag, Reborn: Diaries and Notebooks, 1947–1963

Week 2: André Gide, Journals and The Counterfeiters

Week 3: Franz Kafka, Diaries, 1910–1923

Week 4: Virginia Woolf, A Writer’s Diary

Week 5: Carolina Maria de Jesus, Child of the Dark

Week 6: Cesare Pavese, The Burning Brand: Diaries 1935–1950

Week 7: Bram Stoker, Dracula

Week 8: Robert Walser, A Schoolboy’s Diary; James Joyce, A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man

Week 9: Leonora Carrington, Down Below; Primo Levi, “His Own Blacksmith: To Italo Calvino”

Week 10: Annie Ernaux, Happening

Week 11: Lydia Davis, “Cape Cod Diary”; Sarah Manguso, Ongoingness

Week 12: Alba de Céspedes, Forbidden Notebook

Week 13: Alba de Céspedes, Forbidden Notebook

March 27, 2024

See Everything: On Joseph Mitchell’s Objects

Photograph by Therese Mitchell. Courtesy of Nora Sanborn and Elizabeth Mitchell.

A black-and-white photograph, three and a half by five inches, shows a figure in profile—a silhouette in suit and hat, alone on a giant heap of demolished buildings far above the cathedral tower of the Brooklyn Bridge. I found it in a stack of photos stored inside a small envelope with a handwritten label: “NY Downtown, Summer 1971.” The man’s expression is hidden, but his stooped posture and tiny scale against the massive pile make the picture feel lonely. His eyes are fixed on something beyond the frame, but the longer I studied it, the more I could see him staring at the Twin Towers, which, though unfinished, had reached their full height.

The man in the photo is the writer Joseph Mitchell, who was then in his early sixties, or “well past what Dante called the middle of the journey,” as he wrote in his notes. From 1938 to 1964, he published legendary profiles as a staff writer at The New Yorker, mostly portraits of ordinary people in disappearing worlds on the edges of the city. By 1971, he was a stranger to himself. Increasingly he wandered the city by day and at night, surprised by the intensity of his emotion. The beauty of commonplace images—“a sunflower growing in a vacant lot”—had become almost unbearably moving to him, and sometimes he stared for a long time at certain old buildings in the city, trying to understand why he felt so drawn to them.

For more than three decades, the story goes, he went to his office at The New Yorker on West Forty-Third Street almost every day, worked behind his closed door, and never submitted another story. But unpublished fragments—notes, drafts, letters, photographs, and found objects—attest to another Mitchell, one who would leave his desk to visit an old cemetery or enter a demolition site, where, he noted, he worked as hard as he ever did. In his published stories, he preserved lives that might have otherwise gone unnoticed, then he gathered objects from their threatened worlds. Mitchell couldn’t find one single way to describe what had changed—he called it “living in the past,” “living with the dead,” “living as in a dream, or, I might as well say it, as in a nightmare”—but he claimed to know the exact moment when he metamorphosed into an obsessed collector.

It was 4 A.M. on the Friday of October 4, 1968. Mitchell woke from uneasy dreams, then got out of bed as quietly as he could, so as not to disturb his wife, Therese, and set out from their 44 West Tenth Street apartment for the Fulton Fish Market, where “the smoky riverbank dawn, the racket the fishmongers make, the seaweedy smell, and the sight of this plentifulness,” as Mitchell wrote in his 1952 profile “Up in the Old Hotel,” always gave him a feeling of well-being. But urban renewal projects had doomed much of Lower Manhattan, and the wrecking ball was destroying whole blocks. (In the previous year, more than sixty acres of buildings were demolished.) The piles of rubble depressed him, so he went to the Paris Café at Meyer’s Hotel, which afforded a good view of the East River. He ordered coffee, found a spot at the bar, and as he observed people cooking fish on the riverbank and box fires built against the blackened posts of the elevated highway, he saw his oldest friend in the city, Joe Cantalupo.

Cantalupo was a white-haired, energetic New Yorker. He’d been working at the market since he was fourteen years old. Mitchell met him in 1931. Ever since, Cantalupo, who owned a carting business, had been his fish-market guide, and their shared reverence for the market—especially its old buildings—led to a mysterious union. That day, Cantalupo wanted to show him something, so they left the café and crossed South Street to arrive at one of the oldest sheds in the market, where, in a loft on the second floor, a large object was covered with a tarp. Cantalupo lifted the cover, revealing a halibut box filled with old papers. One of the fishmongers had told him to get rid of it, Cantalupo told Mitchell, according to his notes, but when Cantalupo came up there to dispose of the box, he’d found a cat inside—she was having a litter—and he didn’t want to disturb her. Cantalupo liked the market cats, so he kept on going up to the loft. Each time he did, the cats were still there, and each time, he would glance at the old bills and receipts, names he’d known since he was a boy—and it occurred to him that Mitchell might like to see them.

Mitchell spent the next three days looking obsessively through the fish-box papers. He took them back to his apartment, and when he picked up a brick from a destroyed Lower Manhattan building, he felt his spirits lift, so he took the brick home, too. The ruins exerted a strong pull on Mitchell, whose art worked by repetition. As a writer, he returned to the same subjects again and again, above all the waterfronts of New York and the people connected to them. In his profiles he had reached for what he called “the real true deep-down hidden” life in his subjects, many of whom had begun to die as the worlds around them vanished. Perhaps if Mitchell could bring the past home, in pieces, he could continue his pursuit of a deeper world; the objects could give him a future. Or perhaps he knew it was time to let go of the past but clung anyway. In any case, guided by Cantalupo for about ten years, Mitchell went from ruin to ruin, filling paper grocery bags with whatever caught his eye. At the end of each expedition, his suit was covered in dust.

Eventually, Mitchell’s vast collection filled every corner and covered every surface of his small apartment. He’d accumulated hundreds of architectural pieces, including cast-iron stars, Hudson River bricks, terra-cotta ornaments, finials from cast-iron lampposts, carved brownstone, egg-and-dart moldings, Greek keys, fret tiles, rosettes, stone decorations, U-shaped cast-iron pieces, a cast-iron fleur-de-lis. Some of these objects were stored beside the shelves packed with his collection of books: the red-cracked spine of a volume of Shakespeare’s plays, small blue volumes of Proust, seventeen books on the Jugtown Potters, every edition of Wildlife in North Carolina—North Carolina was his native state—and some two hundred and fifty books on Joyce, including a worn copy of Ulysses. He stacked piles of ephemera into boxes—a makeshift archive—alongside boxes of his daily notes, each page folded to the size of his pocket. Mitchell sometimes expressed feeling for these objects—”I’ve been looking at these cast-iron stars for years, wishing they could be saved”—and sometimes, after climbing through half-demolished buildings, his obsession bewildered him—”risking my life for two iron dogs when I already have six, seven, eight, maybe more of them at home.” But mostly he documented his finds in plain detail: “bricks from a demolition on Ferry Street, bricks from the Rhinelander Building, bricks from the World Trade Center, six bricks, more bricks, old bricks, red bricks with names all sunken in—KING, MALLEY, ARCHER, RICHMOND, ROSE.”

Mitchell wanted to write about his thirty-year search, but when he died in 1996 at the age of eighty-seven, the story remained unfinished, though many of its pieces survived. Some of them can be found in his papers at the New York Public Library and some are at the South Street Seaport Museum, but most of his objects and ephemera have been divided equally between his daughters—Nora in New Jersey and Elizabeth in Atlanta—who, after their father died, carried away three truckloads. Seeing some of them preserved at Nora’s and Elizabeth’s was at once moving and sad. When I called her father’s objects “fragments,” Elizabeth flinched. “Whenever I hear that word, I think of The Waste Land—’These fragments I have shored against my ruins.’ My father and I used to listen to a recording of it,” she said. “He was trying to stave something off, but he knew it wouldn’t work.” Earlier that day, I had found a typed letter to Mitchell from his old friend the writer and editor William Maxwell, sent after Mitchell’s father’s death in 1976, when Mitchell was almost seventy. Maxwell had read an interview with the poet John Hall Wheelock in the Fall 1976 issue of The Paris Review, some of which, he wrote, applied to both him and Mitchell: “Everything is in flux,” said Wheelock. “Our places are taken by others. The generations can’t be poured into one life span. It almost seems as if time was an invention to make it possible to provide space for more to come.”

When I saw the photograph of Mitchell on the heap of demolished buildings, I was up in Elizabeth’s attic, surrounded by pieces of his collection I hadn’t seen. It was the summer of 2023. That morning, Elizabeth, who is now in her seventies, helped me look through boxes until she needed a break, and for the last few hours I was alone with Mitchell’s things. A small open window let some air in, but the piles of idle objects overwhelmed me. I thought of Mitchell’s dictum to a friend, repeated later to me: “See everything, remember everything.” Through his observation, things could transform, the prosaic suddenly sublime. When he looked at a blazing winter sunset in North Carolina, he saw “colors as deep and mysterious as stained-glass colors, seen through a million limbs and branches,” and when he caught a shaft of red sunlight slanting through stained glass at Grace Church on Broadway and East Tenth Street, he saw “the red of a split-open pomegranate.” Just as I was about to leave, I noticed a few shards of yellow glass and then read Mitchell’s note, written in pencil on a piece of cardboard he had tied to the glass with string. “Yellow panes from windows high up on the west side of the Erie Lackawanna ferry house on Barclay Street. I remember seeing sunsets through these windows.” I lifted a shard to the attic window, let the afternoon light pass through it, and watched the glass turn gold.

Scott Schomburg is a writer based in New York City. His book on Joseph Mitchell is forthcoming in 2025.

March 26, 2024

With Melville in Pittsfield

View of Mount Greylock from Herman Melville’s desk in Pittsfield. Licensed under CCO 4.0, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

The fictional Pittsfield, Massachusetts, native Mack Bolan first appeared in Don Pendleton’s 1969 novel The Executioner #1: War Against the Mafia. A self-righteous vigilante (“I am not their judge. I am their judgment”), the by-now-lesser-known Bolan was the inspiration for the popular Marvel Comics antihero Frank Castle, also called the Punisher, who made his debut in 1974’s The Amazing Spider-Man #129 and who has been played by Dolph Lundgren, Thomas Jane, and Ray Stevenson in three movies and by Jon Bernthal in a recent Netflix television series. (Season one, episode one: Castle is reading Moby-Dick.)

Bolan’s and Castle’s origins are not the same. Castle’s family was murdered by the mob—that’s how the red wheel cranks into motion, that’s his permission to kill. But Bolan’s story is different. His father gets in debt to the mob, gets sick, and falls behind on loan payments. His sister, Cindy, starts turning tricks for the mob to help pay off her father’s debt. When Bolan’s little brother finds her out, he tells their father. Their father shoots his son, Bolan’s brother, wounding him, then kills his wife and daughter, Bolan’s mother and sister, before killing himself. War Against the Mafia begins with Bolan turning away from the fact that it was his own father, not the mob, who murdered his family.

Given that Bolan was from Pittsfield, where Herman Melville lived from 1850 until 1863, and given that Castle in 2008’s Punisher: War Zone snarls in a church, “I’d like to get my hands on God,” and given that “War Against the Father” could be another name for the satanic Captain Ahab’s pursuit of Moby-Dick as a murderous revolt against God the Father, it was no surprise to me that these overlapping references filled my head as I drove toward Pittsfield through blinding sleet. “You Are At 1724 Feet Highest Elevation on I-90 East of South Dakota,” said a brown sign near Becket, Massachusetts. Hence my elevated thoughts.

I have been to that even more elevated spot on I-90 in South Dakota. The year was 2016. I saw the sun rise as I drove through the Fort Pierre National Grassland on US 83. Then I turned east on I-90 at Vivian, ate breakfast in Presho, and drove through Kennebec and Lyman and Reliance and Oacoma (1,729 feet above sea level, five feet higher than the roadside sign in Becket) and Chamberlain and Pukwana and Kimball and White Lake and Plankinton and Mount Vernon and Betts and Mitchell and Alexandria and Hartford on my way to Sioux Falls, where I stopped at Bob’s Cafe for a dynamite two-piece fried chicken plate with beans and slaw.

I was born in Kentucky and I lived there for thirty years, and I know a thing or two about fried chicken. That chicken was the best thing that happened to me all day in Sioux Falls, better than Second Chance Auto Buy Sell Trade, Appliance and Furniture RentAll, Delux Motel, Paradise Casino, Booze Boys Discount Wine & Liquor, World Wide Automotive, Automatic Super Wash, Specialty Wheel & Tire, Brothers Auto Sales, MetaBank, J.J.’s Billiards, Easy Dough Casino, $$$ Jokerz Casino, Robson Hardware, Freedom Valu Center, West Side City Casino, Angel Nails, J & R Auto Sales, Interstate All Battery Center, or the W. H. Lyon Fairgrounds, and even better than Zort’s Fireworks, five miles northwest of Sioux City on I-29.

There’s not much I like better than driving in this country.

Lighting out for Mack Bolan territory, then, westward leading on I-90 through Natick and Cochituate and Framingham, Fayville and Westborough and Woodville and North Grafton, Charlton City and Fiskdale and West Brimfield, Palmer Center and Thorndike and Three Rivers and East Wilbraham, Ludlow and Springfield and Chicopee and West Springfield and Westfield, Woronoco and Woronoco Heights and Blandford, into Berkshire County and West Becket and East Lee, and north on 20 through Lee and Lenox and the Housatonic Valley to Arrowhead, on the southern outskirts of Pittsfield. Let’s see what Melville has to say about all of this.

Snow in the yards and snow on the roofs of Grafton, snow on the rocks, snow on the hills. A red-tailed hawk crossed left to right in front of my car so low I could see the brown and white marks on her belly. Snow on the banks of the stream at Auburn. Snow on the stonework underneath the power lines. Snow in the wide white fields. Snow falling on Charlton westbound service plaza. Coming into Palmer, the Quaboag River was partly frozen, white with snow. Coming into Wilbraham, Home of [illegible] Ice Cream, its sign was buried under snow. Coming into West Springfield, visibility got low at the Connecticut River. My car was encrusted with dirty road salt like a steak au poivre. I smelled like a french fry. Some of the huge spears of ice hanging from red and brown rock walls to the left and right were netted off, as if to discourage or prevent ice climbing. Made me want to do a bit of front-pointing.

The trucks roared past, dangerous in the wet snow. Home Depot, Rent Me Starting at $29. A cement mixer with J. P. Noonan Transportation flaps. A Herc Rentals flatbed. A J. P. Rivard flatbed out of North Chelmsford. A Ford Super Duty F-350 XLT pulling a trailer with three wrecked cars on it. Arpin America Moving and Storage, operated by Wheaton Van Lines out of Indianapolis.

The bear went over the mountain to see what he could see, but all that he could see was the other side of the mountain. So the bear came down the other side of the mountain, down, down, like Pip in Moby-Dick when he saw the foot upon the treadle—

carried down alive to wondrous depths … and among the joyous, heartless, ever-juvenile eternities, Pip saw the multitudinous, God-omnipresent, coral insects, that out of the firmament of waters heaved the colossal orbs. He saw God’s foot upon the treadle of the loom, and spoke it; and therefore his shipmates called him mad.

Andrew Delbanco tells us in Melville: His World and Work that it was during an 1850 hike together up Monument Mountain (elevation 1,642 feet) in Stockbridge, Berkshire County, that Nathaniel Hawthorne stoked Melville’s literary ambition anew, stirring him to revise his existing manuscript of Moby-Dick entirely and to set his sights higher, to proclaim rapturously that “genius, all over the world, stands hand in hand, and one shock of recognition runs the whole circle round.”

Melville meant himself. You want to be careful what you wish for. Inspiration means breathing. Fish breathe by drowning.

And Laurie Robertson-Lorant tells us, in Melville: A Biography, that when Melville moved to Pittsfield in 1850, “the Boston Daily Times picked it up and announced: ‘Herman Melville, the popular young author, has purchased a farm in Berkshire county Mass., about thirty miles from Albany, where he intends to raise poultry, turnips, babies, and other vegetables.’ ”

Here are some of the vegetables Melville managed to raise at Arrowhead. Moby-Dick; or, The Whale.—Pierre; or, The Ambiguities.—Israel Potter: His Fifty Years of Exile.—The Confidence-Man: His Masquerade.

Now see here. I have driven to Arrowhead—a big mustard-yellow house built in the 1780s on 160 acres, a secular shrine, profane, not divine, but genuine, actual, and legitimate—and looked out of Melville’s upstairs-study window at Mount Greylock, that “grand hooded phantom, like a snow hill in the air.”

Melville wrote, of this view:

I look out of my window in the morning when I rise as I would out of a port-hole of a ship in the Atlantic. My room seems a ship’s cabin; & at nights when I wake up & hear the wind shrieking, I almost fancy there is too much sail on the house, & I had better go on the roof & rig in the chimney.

It was snowing on the hill as I stood and stared at the white whale’s twin.

The whaling voyage was welcome; the great flood-gates of the wonder-world swung open, and in the wild conceits that swayed me to my purpose, two and two there floated into my inmost soul, endless processions of the whale, and, mid most of them all, one grand hooded phantom, like a snow hill in the air.

There she blows!—there she blows! A hump like a snow-hill! It is Moby-Dick!

Hot tears are in my eyes, the same eyes that saw the white whale, as I write this. Where today are the castaways of my youth, the rednecks of Fern Creek and Okolona and Fairdale and J-Town and Buechel and Newburg who loved Moby-Dick as only fundamentalists, trained to treat a book as holy, can love a make-believe story?

I can still hear Ronnie’s friend Dopey Mike howling “Thou all-destroying but unconquering whale; to the last I grapple with thee; from hell’s heart I stab at thee!” Dopey Mike was a bore, a dangerous bore. I never saw that dopey alchemist again after he spilled his wormwood-stinking homemade absinthe apparatus, alembics and all, and set Ronnie’s kitchen on fire. That was at Ronnie’s house down by the Moby Dick restaurant at South Third and Winkler, come to think of it. My ex-wife loved their breaded mushrooms. She hated their hush puppies, though. Back then I was a loud puppy. You don’t see a lot of alembics these days. Ronnie himself is a fugitive from justice, that’s the news from back home. Why then here does anyone step forth?—Because one did survive the wreck.

It’s no secret that Melville loved his big porch at Arrowhead.

When I removed into the country, it was to occupy an old-fashioned farm-house, which had no piazza … Now, for a house, so situated in such a country, to have no piazza for the convenience of those who might desire to feast upon the view, and take their time and ease about it, seemed as much of an omission as if a picture-gallery should have no bench … A piazza must be had. The house was wide—my fortune narrow; so that, to build a panoramic piazza, one round and round, it could not be … Upon but one of the four sides would prudence grant me what I wanted. Now, which side? … No sooner was ground broken, than all the neighborhood, neighbor Dives, in particular, broke, too—into a laugh. Piazza to the north! Winter piazza! … But, even in December, this northern piazza does not repel—nipping cold and gusty though it be, and the north wind, like any miller, bolting by the snow, in finest flour—for then, once more, with frosted beard, I pace the sleety deck, weathering Cape Horn.

Melville wrote a book about his porch, The Piazza Tales. That’s where you’ll find “Benito Cereno” and “Bartleby, the Scrivener.” I and the other pilgrims to Arrowhead stood on the sleety deck of Melville’s yellow winter piazza not in December but in February, still nipping cold and gusty, snow lashing our faces as we gazed across pale brown fields.

The true believers were nowhere in sight on that snowy morning. Our guide had a few questions. “Do you know a lot about Melville?” he said to me. “I had a real big fan here one time. Showed me up. Told me later he taught Melville at Michigan.”

“I just read the make-believe stories. I don’t know anything about the real man.” Which is not true. I munched on that Elizabeth Hardwick biography of Melville back in 2000. But what are you, the cops? Show me your badge.

A tall, good-looking man with a closely trimmed white beard wearing under his winter coat a black T-shirt with a picture of Bender, the robot from Futurama, said, “I don’t even know who Herman Melville is. I’ll be honest with you, I’m not sure why I’m here today.” Not one man jack of them had read Moby-Dick. Still, they had been drawn there by a mysterious force.

Our guide wasn’t a fan. He finished the tour and said, “Before we disperse, can we all agree that Moby-Dick is a hot mess?” It was a strange question to ask a roomful of people who had already admitted they hadn’t read the book. The heretics are in charge of this temple, I thought, but their devotion is more poignant because they do not believe. They do not have faith, but they have faith in faith.

I mostly managed to keep my mouth shut, which is not my strong suit. But as our guide rambled on about how he thought Moby-Dick should have been cut by half, such that it was only the exciting fish story shorn of whaling arcana, my evil spirit came upon me and opened my jaws. The part you hate is my favorite part, I said. He stared at me as if I were a madman. Which, of course, I am. But I saw the whale first. The doubloon is mine.

J. D. Daniels is the winner of a 2016 Whiting Award and The Paris Review’s 2013 Terry Southern Prize. His collection The Correspondence was published in 2017. His writing has appeared in The Paris Review, Esquire, n+1, the Los Angeles Review of Books, and elsewhere, including The Best American Essays and The Best American Travel Writing.

March 25, 2024

A Conversation with Louise Erdrich

Photograph by Angela Erdrich.

The Paris Review’s Writers at Work interview series has been a hallmark of the magazine since its founding in 1953. These interviews, often conducted over months and sometimes even years, aim to provide insight into how each subject came to be the writer they are, and how the work gets done, and can serve as a kind of defining moment—crystallizing a version of the writer’s legacy in print. Of course, after their interviews appear in our pages, many writers just keep going, and their lives undergo further twists and turns. Sometimes, too, there are gaps and omissions in the original interviews that can become clear as time goes on. This is part of why we’re launching a new series of web interviews called Writers at Work, Revisited. The first will be an interview by Sterling HolyWhiteMountain with Louise Erdrich, who was originally interviewed for the magazine in 2010.

***

Americans have most often viewed Indians through an anthropological lens; the desire to understand us through difference overtakes all else and creates a permanent distance between the seer and the seen. It is the oldest story in America, and over time has exerted such pressure on Indians that we’ve become explainers nonpareil in every facet of our lives—our fiction being no exception. Once you see it you cannot unsee it; the sheer amount of explaining directed at non-Native readers that takes place in Native writing is remarkable. The best of us, though, continue to do what good writers in this country have always done: produce fiction that is more in conversation with the aesthetic lineage of English literature than any particular audience or political question. From the start Louise Erdrich’s writing has had this quality, and her large body of work is a lodestar for the Native writers who have come after her, showing us how to write past America’s ideas and expectations about Indians into places both more tribally specific, and more human. Her work acts as the primary bridge between the writers of the Native American Renaissance—N. Scott Momaday, James Welch, Leslie Marmon Silko—and the explosion of Native writing currently taking place. Her characters, regardless of their culture or history, remind us of that great paradox of humanity, that we are all profoundly different, and very much the same. Perhaps most importantly her work reminds us that good fiction is made up of good sentences.

I had expected, because of her lack of public presence, to meet a writer who was something of a recluse. When I finally made it to Minneapolis, however, I found her to be open, self-effacing, funny, generous, and troublingly up-to-date on the politics of the moment—in both America and Indian country. She was also familiar to me in that way Indians are regardless of what tribe or geography they come from. She spends most days, when she is not traveling to various parts of the Midwest for familial and ceremonial reasons, working in her bookstore, Birchbark Books, one of the finest independent bookstores in the country. The store is the only one of its kind: owned and curated by a major Native writer, run by Native employees, where you can find a copy of Anna Karenina a few feet from abalone shells and sweetgrass. Louise was gracious enough to take time from her usual day of working in the back office to talk with me in the basement of the store.

—Sterling HolyWhiteMountain

ERDRICH

How’s your car? You were having some trouble with it.

INTERVIEWER

I got pulled over last night. I’ve never seen a cop so perplexed. He was skeptical about everything, which I get. I said, I’m moving out to Massachusetts for seven months, and I have to be in Minneapolis tomorrow morning for an interview. Here I am in this old truck I got from my sister that’s full of my junk. I didn’t have insurance. I was going to get it yesterday morning, but I started having engine troubles and forgot all about it. So I’m driving most of the night through endless North Dakota and into Minnesota at forty miles an hour—any faster and the engine would quit. He ended up letting me off.

ERDRICH

I hope you thought your novel out on that slow ride. I remember, when I started out, I was always writing poems about the desperate women in the breakdown lane, which was where I always found myself because I also had an unreliable car, a Chevy Impala station wagon. It would overheat, but a great car.

INTERVIEWER

This is after college? I’d love to hear about how you got started.

ERDRICH

Start the car? If the key didn’t work, I used a slot-head screwdriver and a hammer. Writing? I don’t actually know. I always wrote, then at some point I realized it was the only grown-up thing I knew how to do. After college, I was living in Fargo and got a seventy-dollar-a-month office at the top of a building that looked out on the horizon. That’s when I started Love Medicine, in that office.

INTERVIEWER

There’s a set of problems that belong only to Native writers, and I’ve noticed that Indians often end up working these problems out alone because they don’t have someone to talk with who understands. When I started writing it was hard to find Native writers I could look to. Did you feel that way when you started?

ERDRICH

I like what you said about the set of questions that belong only to us. There were fewer well-known Native writers back then. But there was James Welch and Leslie Marmon Silko, Simon J. Ortiz, Janet Campbell Hale, Paula Gunn Allen, Beatrice Mosionier, and of course N. Scott Momaday. Roberta Hill and Ray Young Bear were poets I admired. Joy Harjo was and is cherished by us all. There were more Native writers when you were coming up—you had Sherman Alexie. And Eric Gansworth—a formidable writer, intelligent and warm. Still, I know what you mean, because it’s not just writers who are Native. It’s writers with your own particular tribal background. Did you find writers online?

INTERVIEWER

Not at all. Because when I first got going, the internet was in its nascent stages … there was nothing! I didn’t know there was such a thing as a Native writer until I read Alexie’s first book, around the time James Welch came to speak in one of my classes at Missoula. You wrote a great introduction to the 2008 edition of Winter in the Blood, which is arguably Welch’s masterpiece. Did Welch influence your work?

ERDRICH