The Paris Review's Blog, page 36

February 23, 2024

Philistines

Welcome to Disney World! Photograph courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

1.

Once I had to go to Disney World with my small children. On the way to the airport our taxi driver exhibited signs of Obsessive Disney Disorder—when he found out where we were going he started obsessively describing and listing and explaining everything that had to do with Disney World, even though he was a grown man.

We stayed at the Portofino Bay Hotel, a Disney-owned property that is a replica of the storied village on the Italian Riviera. There were imitation Renaissance churches and Mediterranean piazzas clustered around a fake harbor with old Fiats parked on the cobblestones and fishing boats moored in the fake bay. Outside cafés ranged on the harbor, serving espresso under green-and-white striped awnings. Italian cypresses were planted along the pools. If you didn’t know it was a Disney replica of a real place, it would have to be characterized as being extremely tasteful and lovely. So you did tend to get confused between: Is this a theme park of Italy or is it just lovely and pleasant.

There is a REAL Florida out there that is TRULY historic. I madly drove out to find the REAL Orlando, forgetting my phobia of freeways. After almost getting killed (horns blasting at my side, cars swerving out of my way), I did find the real Orlando. It is situated on several lakes lined by turn-of-the-last-century Victorians and bungalows. I went to the history museum. The number one industry in central Florida is cattle. Has anyone in Florida ever seen a head of cattle? No. But maybe that was before Disney.

I went to my first theme park. Not Disney World but another theme park we noticed from the side of the road. Our small children were foaming at the mouth to go to theme parks, they were in the promised land, their dreams were all coming true: theme parks. This one looked maybe more palatable to me than Disney World. It was called the Holy Land Experience. It was founded by a Messianic Jew and meant to replicate Jerusalem in the year A.D. 66. The buildings were ocher-colored like the desert sand with a roseate glow, amid papyrus groves and palms. The background was the I-4 freeway and the giant Mall at Millenia across the street.

You’re directed to a tent among the palms where an Alec Guinness look-alike wearing the garb of an ancient priest starts giving a scholarly lecture on the difference between the tribe of Levi and the Levitical priesthood, whatever that is, nonchalantly tossing off pedantic theological distinctions. You start thinking that the guides must be scholars or priests in real life, because they seem very learned and sad. They shuffle about in their flowing robes throwing bits of food to the birds, looking as if they just stepped out of the Bible. The gift shop sells books that have titles like Three Views on the Rapture: Pretribulation, Prewrath, or Posttribulation. Ha!

Then, in the tradition of theme parks everywhere, a booming narration begins from a recording. But unlike at theme parks everywhere, this recording is reciting Hebrew prayers and explaining the prewrath version of the Rapture—whatever that is.

The next show is in the “Scriptorium” and deals with cuneiform texts, Babylonian tablets, Hebrew scrolls, and other biblical antiquities. What about the poor sapsuckers who got roped into this thinking they were going to Disney World, more or less, now trapped in the Scriptorium discussing the condemnation of Spanish rabbis in fifteenth-century Oxford?

It was sort of ike an old-fashioned wax museum. The brochure calls it a “highly-themed” (translation: you’re in a theme park), “climate-controlled walk-through experience.”

Doors and gateways opened electronically at each new chamber while the booming prerecorded narrator intoned about the bondage of religious traditionalism, the early reform movement that produced the daring first translation of the Latin Bible, and other things like that. Again I pitied the sapsuckers who came to ride on little trains and see life-size stuffed animals, instead stuck in the Scriptorium discussing the bondage of sin.

At the end there was an incredibly cheesy finale inside a replica of the Hagia Sophia with sleazy portraits painted on velvet of religious figures and plush curtains electronically rising in successive waves, accompanied by the booming prerecorded baritone narrator quoting scripture, with the Ten Commandments written in neon on the ceiling (in Hebrew), culminating in an explosive tribute to Jesus Christ.

The high-tech epilogue involved a careening computer room meant to simulate modern times while the omnipotent voice still droned on about the word of God. This led to the gift shop. Mad rush to the gift shop to buy Bibles and prewrath explanations of the Rapture. The cashiers, who also appeared to be preaching, were dressed in the flowing robes of monks.

I asked one of them if the workers here were theological scholars or had religious affiliations. She said they were Christians. But your founder is Jewish, I mentioned. He’s a Messianic Jew, she pointed out.

“So do all denominations work here?” I pursued.

“Oh yes, we have everything—Christians, Jews—so long as they’re Christian.”

The children were richly satisfied. For some reason, children love theme parks no matter what they are about, even if what they are about is Babylonian tablets and outraged Spanish rabbis in the fifteenth century.

We ate lunch at the Oasis Palms Café. Two guys dressed as Roman soldiers cruised by, looking like something left over from the set of Spartacus.

2.

“Mom, would you want to have Slime poured on your head?” asked one of my daughters, then age four. We were taking them to a place where this might actually happen.

MGM Studios, supposedly the least crowded part of Disney World, celebrates the film industry, according to my husband. The Disney film industry, to be more precise. Contradictory to the buildup from my husband, it was the most crowded place that I have ever seen, aside from Bourbon Street on Mardi Gras Day.

It all starts in the parking lot. The parking lot itself is so crowded that you lose hope of ever fully traversing it. Then you come to a tram. Even at the tram there are waves and waves of lines.

Eventually you arrive at the entrance gates on the little tram. Finally you enter the park. Well the upshot of it all is this: After about six hours of waiting in really long lines for the dorky, anticlimactic and in some cases sort of quaint little shows, my husband said we could leave. My heart rose and I headed toward what I thought was the exit.

I noticed even more dense crowds forming. Barricades appeared. I darted quickly out into the street to leave. I was stopped by officious Disney guides saying, “You can’t be here right now.”

Why not? Because the parade was starting. The one where Mickey Mouse and Donald Duck and other characters come through. A screeching girl chattered inanely on a loudspeaker about it.

“You can’t be here right now,” they said repeatedly with stern yet scary affectless expressions.

“Well then where am I supposed to be? I’m trying to leave this place.”

“You can’t be here right now,” said officious people in red jackets tensely.

Behind the barricades the dense crowds surged. The officious Disney people kept harassing me. Security people told me to leave the street, so I had to press into the crowd behind the barricades.

The crowd surged like a giant wave covering me. I took a step through a solid mass of people. When my feet left the ground one of my shoes was gone. I cowered down to retrieve it.

“Is this your bracelet?” asked a man pointing to a crushed shard on the ground.

Now, when you’ve been to Mardi Gras Day every year as a small child you know what it’s like to get trapped in a mob. But it isn’t an angry mob. This was an angry mob. It wanted Mickey. It wanted Daffy. It wanted the flesh from my body. Finally I surged through to the back.

I told my story again to a couple of Disney people standing under an official gazebo. “I’m trying to leave this place,” I said, “and I’m trapped.”

“Go that way,” said officious people in red coats. “Try over there,” they said vaguely.

One of them took pity on me and volunteered to escort me to Guest Relations—which sounds like a euphemism for something ominous. It was adjacent to the entrance/exit, and I sat there forlornly. They wouldn’t let you broadcast an announcement to search for your lost family, otherwise there’d be a hysterical stream of announcements constantly drowning out Mickey and Daffy.

After experiencing stark anxiety and regret for a while about how I might never see them again, lost in Disney World—they showed up on their way out from the parade. They loved it, they adored it, they saw Daffy, they saw Goofy, everything was peachy.

I went back to the hotel and healed. I read while drinking espresso at outside cafés in the sun. They went to another theme park the next day but I sat that one out. I waited for them at the dock of the little harbor built to look like Italy, which indeed it does, and Florida healed me. It did. It was the weather, the sun, the green. Can the blue sky be fake? Theme parks make you exist in a questioning netherworld of reality.

Nancy Lemann is the author of Lives of the Saints, The Ritz of the Bayou, and Sportsman’s Paradise. “Diary of Remorse” was published in the Fall 2022 issue of the Review.

February 22, 2024

Cooking with Franz Kafka

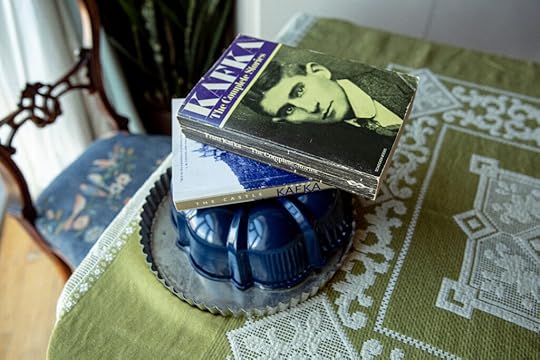

Photograph by Erica Maclean.

In Franz Kafka’s first published story, “Description of a Struggle,” the narrator is sitting in a drawing room at a rickety little table, eating a piece of fruitcake that “did not taste very good,” when a man walks up to him. The man is described as an “acquaintance,” but we soon realize he is a double, or another part of the narrator’s self. The acquaintance has fallen in love and wants to boast about it. “If you weren’t in such a state,” he scolds, “[you] would know how improper it is to talk about an amorous girl to a man sitting alone drinking schnapps.” The comment seems to threaten an unchecked appetite. What would the lonely, schnapps-drinking man do if tempted by the girl? The struggle that follows, metaphorically speaking, is between the sides of the protagonist’s character—on one side, the man who desires to stand apart from society and guard his creative self, and on the other, he who wishes to fit in and reap the pleasures of fruitcake and amorous girls.

Photograph by Erica Maclean. Fruitcake batter, from Kafka’s “Description of a Struggle.” The protagonist consumes it sitting at a tiny table with “three curved, thin legs … sipping my third glass of benedictine.”

The tension in Kafka between appetite and its fulfillment is a crucial aspect of the writer’s work. Kafka’s characters are often hungry—the performer from “A Hunger Artist” has made starving himself into an art; Gregor Samsa from The Metamorphosis slowly stops eating and wastes away. But their hunger is often not for the foods of this world. Gregor refers to himself as hungering as for “an unknown nourishment.” The hunger artist’s last words are a confession that fasting was not difficult for him because, he says, “I couldn’t find the food I liked. If I had found it, believe me, I should have made no fuss and stuffed myself like you or anyone else.” Instead the characters seek the deeper forms of sustenance—emotional, societal, sexual, spiritual—and don’t find them.

Pretzels like these, crusted with salt and caraway seeds, are a reward of belonging to the power structure in Kafka’s The Castle.

The authors of the book Kafka: A Manga Adaptation agree on the centrality of hunger to Kafka’s work. The Japanese brother-and-sister duo Nishioka Kyōdai chose it as the unifying theme for their collection, along with what they call “power and economics.” The book was published last November by Pushkin Press, in a translation by David Yang, and its flat, emaciated characters, with their blank faces and all-black button eyes, display the condition of people in Kafka’s world, starving for something good. But why, and what? It’s the manga artists’ view that the food on the page is telling, and they often devote full panels to it. Despite Kafka’s extremely unappetizing imagination, food appears regularly in his stories and novels—and looking at it, and cooking it, might tell us something about what the characters really hunger for.

In The Metamorphosis, the food is controlled by Gregor’s family. His father, mother, and beautiful young sister, Grete, spend most of the story seated at a table outside Gregor’s room, eating. Gregor, in his grotesque new form, is not allowed at the table. Yet he finds himself on the morning of his transformation to be “much hungrier than usual.” Terrible as his metamorphosis is, it frees him from work and from being useful to his family, suggesting that he is showing a more authentic self. Incidentally, Kafka in his lifetime refused to specify what kind of creature Gregor was and forbade any drawing or representation of him. The Nishioka manga respects this and depicts the story from Gregor’s perspective without ever drawing his body. This absence opens the realm of possibility—we don’t know what Gregor’s transformation truly means, only how it is perceived by himself and others. An unknown winged creature longing for an unknown nourishment could be anything, including an angel.

Photograph by Erica Maclean. Food-grade lye, a caustic ingredient necessary to make the crunchy pretzels from The Castle.

The Metamorphosis contains many indelible food scenes, including an early one when Gregor’s sister, Grete, who at first seems like she might be able to relate to him in his new form, brings him an assortment of dishes to try. He can’t manage the “dish filled with sweetened milk with little pieces of white bread floating in it” that was a favorite treat before, but he is drawn instead to an assortment of grotesque and rotten foods. He finds himself “sucking greedily” at cheese he’d “declared inedible two days before” and then quickly, “one after another, his eyes watering with pleasure,” consuming the rest.

Photograph by Erica Maclean. In The Metamorphosis, the family’s lodgers are fussy eaters and take a critical attitude toward the meat-and-potatoes dinners they are served.

This promising avenue, however, is choked off by his sister’s increasing disinterest in him and by his family’s wholesale rejection of his new self. Later, when he tries to leave his room, his father throws apples at him. Kafka writes that “the little, red apples rolled about on the floor, knocking into each other as if they had electric motors.” This weaponized and surreally mechanized food does Gregor terrible damage. One apple sinks into his shell and leaves him “in a complete derangement of all his senses.” The Nishioka manga spends a page on the apples alone, depicting them on a wood floor whose hand-drawn grain has a creepily uniform and unnatural appearance that is also suggestive of the machine-made.

Kafka’s connection between work and technology as the forces promoting our alienation and misery seems prescient. The machine-apple is a minor note in The Metamorphosis, but we see machines everywhere in the writer’s oeuvre, from the torture machine of “In the Penal Colony” (which also serves food!), to the bureaucracy on display in The Castle. Bureaucracy itself, in this novel, can be seen as a kind of metamachine for work, and the castle’s functioning is eerily similar to that of the modern corporation.

Moreover, the structure of The Metamorphosis suggests an absent ideal, wherein Gregor could be his authentic self—perhaps doing meaningful work—and also be included in the social order and at the family table. The Castle suggests something similar. Its hero, K., flounders in endless, abstract application to work for the invisible powers that run the mysterious castle. Getting such work will also allow him to settle in the village outside its gates and lead a family life. However, K. constantly sabotages his own efforts. When he gets a taste of a forbidden fruit, like the cognac he steals from a castle official’s sleigh, he barely partakes of it and lets it dribble away.

One element of the brilliance and ongoing power of Kafka’s work is the intensely packed and folded layers of its symbolism. No symbol is ever just one thing; the fruitcake of “Description of a Struggle” is a lure to taste the fruits of corruption; the apple in the sophisticated later work is both fruit of the family’s participation in the machine and a placeholder suggesting the absent nourishment that Gregor longs for. I wondered what would happen if I made these foods—would they be doubly delicious, both alluring and sustaining, or as grotesque as the rotten food spread and as absent of flavor as the fruitcake?

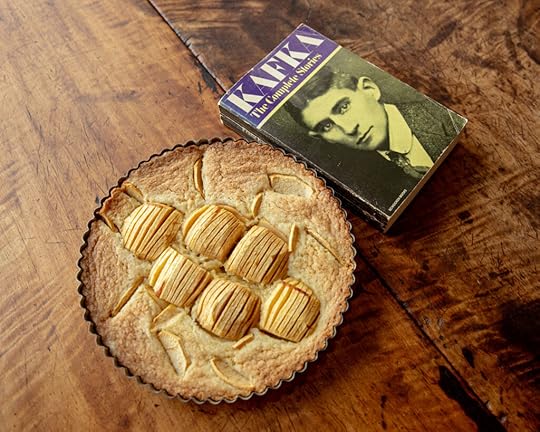

I chose to make the sausage and potatoes served to the lodgers in The Metamorphosis, depicted in a panel of the Nishioka manga being carried by Gregor’s mother and Grete in faceless and stylized lockstep, surrounded by more sinister wood grain. This was the food of exclusion, served to three men who have disturbed the family home and taken Gregor’s place. I made a German apple cake, also from The Metamorphosis, with the apples visibly embedded, as they were in Gregor’s shell. Other snacks were caraway seed–encrusted pretzels crunched by an official in The Castle—a symbol of power and its tasty reward. And lastly, of course, I made a fruitcake.

Rarely have the results of any cooking experiment been so definitive. I did quite a bit of experimentation—there just aren’t perfect recipes for old-fashioned, technique-driven things like fruitcake and pretzels on the internet. But post-experimenting, with refined recipes, I produced classic, simple foods that were almost unbelievably good. For my meat and potatoes dish, I used high-quality sausages of a few varieties, including some from a Polish butcher near my house in Brooklyn, and I bought a biodynamic sauerkraut from a health food store to mix with the roasted potatoes. A sheet pan plus oil, salt, and pepper makes this one of the most delicious three-ingredient meals on earth. My apple cake was also simple but outstanding. Most cakes require a painstaking emulsion of liquids in order not to break the batter. For this one, the recipe instructed me to mix all the dry ingredients together with the softened butter, making a batter that was more like cookie dough, and pat it into a tart pan with the bottom of a glass before arranging the apples on top. The tender, pillowy results made me wonder why anyone makes cake in any other way. And the flavor was mysteriously ambrosial—various tasters guessed honey, almond, or marzipan—despite my using nothing more than the most standard flour-butter-sugar mixture.

Photograph by Erica Maclean. “No-one dared to remove the apple lodged in Gregor’s flesh, so it remained there as a visible reminder of his injury.”

The pretzels and the fruitcake were not simple but were even more satisfying. Pretzels are made from yeast dough, which is tricky to time, and they aren’t easy to roll out and shape without some experience. Once the pretzels are shaped, the authentic kind are dipped in a bath of a food-grade lye solution that gives them their leathery brown skin and flavor. They’re then sprinkled with toppings and painstakingly dried out in the oven. My recipe below is the culmination of much trial and error, but once perfected, my pretzels were addictively salty and crunchy and gave me a bizarre food high. Pretzels, in the modern world, are underrated.

There are no happy endings in Kafka—you can have either your soul or the fruitcake. In one of the several fragmented sections in “Description of a Struggle,” titled “Proof That It’s Impossible to Live” one character tells another that “one day everyone wanting to live will look like me—cut out of tissue paper, like silhouettes, as you pointed out—and when they walk they will be heard to rustle.” I’m not sure this is true of us; there is a stubborn animality to us that persists, despite our new technologies. But it is true of our things, evermore shoddy and false and disconnected. Take my fruitcake. The internet is full of fruitcake recipes. I tried several and never found one that made a cake you’d want a second piece of. So then I went offline, making elements myself, such as candied fruit peel, and choosing the fruit and nut assortment based not on a recipe but on what I could find that was made in the smallest batches and least industrially. The dried fruit, I thought, should be tart, boozy, and pretty; the nuts should be rich and fresh, and the batter should be just enough to hold it together. Working in this vein, after many tries, I made a wildly good cake that I personally couldn’t stop eating. In my book, if not in Kafka’s, it was not absent goodness but goodness itself.

Pretzels with Caraway Seeds

For the dough:

1 cup plus 2 tbsp warm water, 110 to 115°F

2 tsp light brown sugar, divided

1 1/4 tsp active dry yeast

1 1/2 cups white flour

1 1/2 cups bread flour

1/2 tsp salt

For the lye bath:

4 cups water, room temperature

2 tbsp food-grade lye

For the topping:

2 tbsp coarse sea salt

1 tbsp caraway seeds

In a small bowl, combine 1/4 cup warm water and 1/2 teaspoon brown sugar. Add yeast and stir to dissolve. Let sit five minutes until yeast is foamy. (If it doesn’t puff up, discard and use different yeast.) Once the yeast is proofed, in the large bowl of a stand mixer, stir in the remaining 1 1/2 teaspoon brown sugar, both flours, and salt. Add the yeast mixture and 3/4 cup warm water. The dough should be soft and pliable. If it seems too stiff, add more water and knead using the dough hook attachment for five minutes, until the dough is smooth and elastic. Place in a lightly oiled bowl, covered, and set inside your microwave with the door slightly ajar so the light stays on. (This mimics a proofing box and is a trick for raising bread in colder climates. If you’re in a warm climate, the countertop is fine.)

While the dough is rising, which can happen in less than forty-five minutes, prepare the lye bath. Lye is a caustic substance and could damage your skin and eyes, and there are many warnings and safety guidelines available on the internet about working with it; I recommend these. It’s essential that you use food-grade lye, available on Amazon, which makes the pretzel’s hard, blistered skin. Lye is also corrosive to containers, so you want a nonreactive plastic container for the following step. Tupperware-style plastic containers say which kind of plastic they are on the bottom, and you want number two plastic (HDPE, or high-density polyethylene) or number five plastic (PP, or polypropylene). Taking all relevant safety precautions, fill the container with water, add the lye, and use a silicone spatula to stir to dissolve.

Prepare to shape and bake. Set out a baking sheet lined with parchment paper and butter it liberally, otherwise the lye-dipped pretzels will stick to the paper. Preheat the oven to 325°F. Set a small bowl of water on the countertop where you’ll roll out the pretzels. Combine the salt and caraway seeds for the topping. When the dough has doubled in size, cut it in quarters, then shape each quarter into an even log, knocking out as little air as possible. Cut each log into fifths. Cover the unused dough with a damp towel and prepare to roll out and shape. The objective is twenty long, thin rolled strands of about fifteen to eighteen inches each. However, the rolling can be challenging since the dough quickly gets stiff and overworked. Starting with your thumbs in the center of the ball, quickly and smoothly press down while rolling the dough back and forth on the countertop. (I didn’t need to flour my workspace, but it might depend on your dough.) You want to coax the dough into shape before it loses too much air. No pinching, pressing, or pre-shaping, or it will become hard to work with. As the dough strand lengthens, flatten your hands until you’re using both palms to roll, and you can really apply a lot of pressure. If the dough becomes too tough and springy, set it aside for five minutes to rest.

When the dough strand has reached the desired length, twist it into shape. There’s a good tutorial on shaping with photos available here. In brief: Take a rope of dough and make a U shape. Cross the arms over once, then cross again in the same direction to make the twist. Then bring the arms down to the belly of the U, dab each one on the underside with a little bit of water, and press them firmly to create the pretzel shape. Cover and let rise again for twenty minutes. Then uncover and let sit for fifteen more minutes to form a skin. Ideally, at this point you’d freeze the dough for at least twenty minutes to make it easier to work with during the dipping process, but I ran out of time, and it was fine.

When the pretzels are ready, dip each one into the lye bath for thirty seconds, using a slotted spoon or tongs, then place the pretzel on the greased parchment. When all pretzels are dipped, sprinkle with the topping. Bake for twenty-five minutes, then rotate the pan and bake for forty minutes more. (The steam created during baking will neutralize the lye and make the pretzels safe to handle and eat.) The timing is less important than getting the dough completely dry and crisp. You can determine doneness by tapping the pretzel with your finger or by sacrificing a pretzel to test and breaking it. If they’re browning too quickly but aren’t yet crisp, remove them from the oven and allow them to cool while reducing the oven temperature to 300°F. Return to the oven and bake ten more minutes and check. If still not done, continue baking, checking every five minutes until crisp.

Sausage and Potatoes

3 sausages, German style, cooked or uncooked

4–5 large white potatoes, peeled and cubed

Olive oil

Salt and pepper

1 cup sauerkraut

Preheat the oven to 400°F. Arrange the potatoes on a sheet pan, drizzle generously with olive oil, season with salt and pepper, and toss with your hands to combine. Arrange the sausages on top of the potatoes and bake, uncovered, thirty minutes, tossing occasionally, until the sausages are cooked through and the potatoes are crispy and browned. If your mixture includes cooked sausage, it will puff up and burst, but that’s fine. Five minutes before the end of the bake time, add the sauerkraut to the tray and toss to combine. Serve warm.

Fruitcake

Fruitcakes are better with age, and many of the ingredients suggested here are better made over the course of several days. Start at least two weeks ahead of the time you wish to serve or gift your cake.

For the fruit and nuts:

2 cups high-quality* mixed dried fruit: apricots, large golden raisins, dried pineapple, red and green candied cherries

2 cups rum

3/4 cup soft, chewy Medjool dates, chopped

1/4 cup mixed candied peel, chopped (use only if homemade, otherwise substitute crystallized ginger)

1 1/2 cups chopped nuts (recommend a mixture of pecans and pistachios)

*NOTE: The key to a delicious fruitcake is delicious dried fruit. You’re looking for a combination of tart, sweet, juicy, and pretty in your fruit choices. The types of fruit you use matter less than choosing fruits that will look and taste the best.

For the batter:

1 stick butter, room temperature

1 cup dark brown sugar, packed

1/2 tsp salt

3/4 tsp cinnamon

1/8 tsp allspice

1/8 tsp nutmeg

1/2 tsp baking powder

2 eggs, room temperature

1/4 cup golden syrup

1 tbsp cocoa powder

1 1/2 cups flour

2 tbsp water

Chop the apricots or other larger dried fruits in your two cups of fruit mixture. (I like to leave the colorful candied cherries whole for visual appeal.) Place the mixture in a covered, nonreactive bowl and cover with the two cups of rum. You want the fruit to be fully submerged. Cover and let sit for eight hours or overnight or even longer. (You are not soaking the dates or the candied peel.)

When it’s time to assemble the cake, preheat the oven to 300°F. Grease a nine-by-four-inch loaf pan. Place the butter and brown sugar in the bowl of your stand mixer and whip until fluffy and well-combined. Add salt, spices, and baking powder and whip to combine. Add the eggs, one at a time, scraping down the bowl between each addition, followed by the golden syrup. Add the cocoa powder and flour and stir until just combined. Add the water, the dates, the nuts, and two cups of the fruit mixture, scooped out of the liquid but not drained, and stir until combined. (The fruit will swell up with soaking, so you may have more than two cups. Reserve for another use.) Spoon the batter into the pan and bake for forty-five to seventy-five minutes, until a tester entered into the cake comes out clean. Eat immediately.

German Apple Cake

Adapted from Bon Appetit.

1 stick butter, cut into pieces, room temperature, plus more for greasing the pan

1/4 cup breadcrumbs

2/3 cup sugar

1 tbsp lemon zest

1 tsp baking powder

1 tsp salt

1 cup flour

1 egg, fork-whisked

1 tsp vanilla

3 medium, firm, tart apples, such as Granny Smith

Preheat the oven to 350°F. Butter a nine-inch loose-bottom tart pan and dust with breadcrumbs, tapping out the excess. Whisk the sugar, lemon zest, baking powder, salt, and flour together in a large bowl. Then make a well in the middle and add the egg, vanilla, and butter. Stir until the dough comes together in large clumps, then knead gently with your hands until it comes together in a mass. Flour your hands a little if the dough is too sticky.

Gently press the dough into the prepared pan, flattening with the bottom of a glass or measuring cup and using more flour if it sticks. Peel, quarter, and core the apples. Place them cut side down on a cutting board and make thin, parallel crosswise slices in each quarter, taking care not to cut all the way through, so the apples stay in one shingled piece. Arrange the apples in concentric circles over the entire surface of the dough, trimming to fit if necessary (you may have some extra pieces). Bake forty-five to fifty-five minutes, until the apples and crust are golden in color. Check after thirty minutes to make sure the cake is not browning too quickly; if it is, cover with a piece of tinfoil. Cool and serve.

Valerie Stivers is a writer based in New York. Read earlier installments of Eat Your Words.

February 21, 2024

Stopping Dead from the Neck Up

Gustav Klimt, Tannenwald, 1901. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons, public domain.

Today we are publishing a previously unpublished poem by the poet, critic, and editor Delmore Schwartz. Schwartz was hailed as a promising short story writer and poet in the generation that included Robert Lowell, Elizabeth Bishop, and John Berryman; a longtime editor at the Partisan Review, he was the youngest person ever to win the Bollingen Prize in 1959. (Some of Schwartz’s poems and letters were published in the Review in the eighties and nineties.) The poem below was discovered without a date, but is immediately recognizable for its recasting of Robert Frost’s “Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening” from an alcoholic’s perspective. This riff is made poignant by the fact that Schwartz’s later years were characterized by mental illness and alcoholism. He died, largely isolated, at the Chelsea Hotel in 1966.

Whose booze this is, I ought to think I know.

I bought it several weeks ago.

It stands there stolid on the shelf

Making me feel lower than low

Reminding me how I am low,

Making me think of Crane and Poe.

My fatlipped mouth must think it queer

To stop without a single beer,

To stop without a single beer

The deadest day I ever spent

In boredom and in self-contempt,

Sober, sour, discontent.

My fingers have begun to shake,

My nerves think there is some mistake.

The only other thought I think.

Is how I failed to be a rake,

A story which should take the cake.

The booze stares at me like a brink.

But I must wait for five, I think.

Long hours must pass, before I drink;

Long hours and slow, before I drink.

The Collected Poems of Delmore Schwartz will be published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux in April.

February 20, 2024

The Review Wins the 2024 National Magazine Award for Fiction

Illustration by Na Kim.

We are thrilled to announce that The Paris Review has won the 2024 ASME Award for Fiction, marking the second year in a row that the magazine has received the honor. The three prizewinning stories are Rivers Solomon’s “This Is Everything There Will Ever Be,” a disarmingly warm portrait of “just another late-forties dyke entirely too obsessed with basketball, dogs, and memes”; “My Good Friend,” Juliana Leite’s English-language debut, translated from the Portuguese by Zoë Perry, a story written in the form of an elderly widow’s Sunday-evening diary entry (“About the roof repair, I have nothing new to report”) that turns into a story of mostly unspoken, mutual decades-long love; and James Lasdun’s “Helen,” in which a man writing about his parents’ upper-class milieu in seventies London—the time of the IRA’s mainland campaign in Britain—stumbles upon the journals of a family friend, a woman who lives in what the narrator calls a “state of incandescent, almost spiritual horror.” All three stories will be unlocked from behind the paywall this week, and you can also listen to Rivers Solomon’s story on our podcast here. Enjoy!

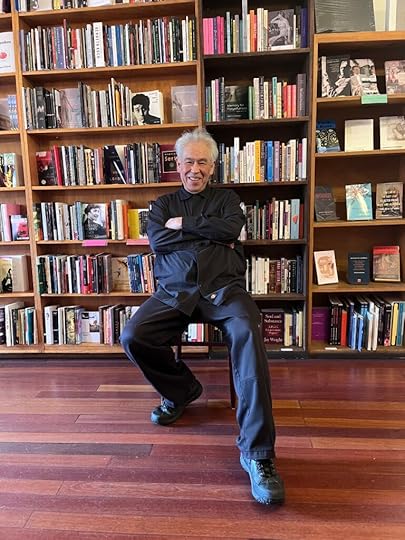

Reading the Room: An Interview with Paul Yamazaki

Courtesy of Stacey Lewis / City Lights.

Paul Yamazaki has been City Lights Bookstore’s chief buyer for over fifty years, responsible for filling the shelves of the San Francisco shop with the diverse range of titles that make City Lights one of the most beloved independent bookstores in the United States. Founded by Lawrence Ferlinghetti in 1953 and once a hangout for Beat poets, today the bookstore and publisher specializes in poetry, literature in translation, and left-leaning books relating to social justice and political theory. Yamazaki was the recipient of the National Book Foundation’s 2023 Literarian Award for Outstanding Service to the American Literary Community and has mentored generations of booksellers across the United States. This interview was compiled from conversations held between Yamazaki and friends of Chicago’s Seminary Co-op Bookstore.

INTERVIEWER

What a joy it is to be here with you today at City Lights on this foggy Saturday in San Francisco. Walking in the front door, I feel like I instantly know where I am. How do you choose which books to put in the browser’s line of sight, how to signal what the bookstore stands for?

PAUL YAMAZAKI

It’s all about developing a conversation between the books. When they’re placed side by side, they talk to one another. Our goal when you walk in is to make sure that, right away, you see books you haven’t seen in other spaces and you see books you already know, in a slightly disorienting way. Right now I’m looking at Jane Jacobs, Lewis Mumford, and Mike Davis grouped together—what a great party to be invited to.

INTERVIEWER

City Lights was founded here, by Peter Martin and Lawrence Ferlinghetti, as the country’s first all-paperback bookstore, and it maintains a dedication to progressive politics and modern literature. Please describe this eccentric corner building in North Beach.

YAMAZAKI

City Lights, since its inception in 1953, has been at 261 Columbus Avenue, which is at the corner of Columbus and Broadway in the northeast quadrant of San Francisco, at the intersection of three distinct immigrant and migrant communities. To the south is the Chinese community, and to the north, the Italian immigrants established a community. To the east was the international district, which was a community of many types of itinerant professions, including seamen, theatrical performers, saloon keepers, prostitutes, and prospectors of all types. The cultural, class, and racial diversities of these communities contributed to the fact that there was a range of housing types at various affordability levels in the neighborhood, which provided cheap rentals for writers and artists.

The other important institution that was close to City Lights was the San Francisco Art Institute, whose faculty and students were important contributors to the bohemian flavor of this part of San Francisco. Every building on the block between Broadway in the north and Pacific on the south burned to the ground during the 1906 earthquake. Our building, 261 Columbus, was one of the first buildings to be completed in the reconstruction. It’s somewhat hyperbolic to say there isn’t a right angle in the building, but it’s metaphorically so. You’re walking through the same doorways that legends like Allen Ginsberg and Diane di Prima walked through. There’s a resonance there. Imagine this space in 1953—350 square feet, filled with magazines and books and people.

INTERVIEWER

You’ve expanded several times since then.

YAMAZAKI

Yes, City Lights now takes up three floors. It feels bigger than it is. There are eighty feet of frontage with generous window displays; they provide the main rooms with glorious light. We have changed some things, but the feeling is the same. The ceilings are twenty feet high, with tight stairways and exposed brick walls. It’s astounding that we haven’t lost anyone to those staircases over the decades! The lower level is a subterranean world, with alcoves and archways that make it feel like it’s in another century. At one point, that basement was an evangelical church. There’s an iconic photo of Lawrence Ferlinghetti here in front of a twenties sign from the church days—“I am the door.” Serendipitous psychedelia. Originally the ground floor was a travel agency run by two Italian brothers. The space that used to be a separate building next door was a topless barbershop.

INTERVIEWER

What guides your curatorial decisions?

YAMAZAKI

It’s a dynamic process. Each bookseller investigates their own subjectivities and their own responses to the texts while still understanding the context of the institution, how we arrived at this point. For example, people are surprised by the fact that we don’t carry most current bestsellers—we could sell many copies, but from our perspective, they are not consistent with our values.

INTERVIEWER

Instead, you have Fred Moten’s In the Break: The Aesthetics of the Black Radical Tradition on display.

YAMAZAKI

My faith in the reader is profound. Our role is to bring them to a new door, to a new room. We are trying to choose the best of what’s out there. How do we arrive at the best? Reading and conversations with other readers, other booksellers. If a book comes into your hands and you find yourself moved by it, ask, How did this find me? Answers to that question will always be fruitful and will always make you a better bookseller. People presume from our fairly healthy selection of critical theory that we are a highly educated, deeply knowledgeable staff. I can testify that this is not the case. But we are curious.

INTERVIEWER

How many titles are you considering in a given year?

YAMAZAKI

At least fifty thousand. There is no way that we could encompass all of that. Even if we could, it wouldn’t lead to a very interesting bookstore. I’ve been at state bookstores in Beijing, and they do that, and it’s fascinating. It’s intimidating, but it leaves it up to the reader to navigate. What we do as booksellers is create an environment where there’s a framework for that sort of navigation. I’m awestruck by buyers of bigger stores like Elliott Bay, which is nearly twenty thousand square feet. I don’t think I could buy for even a five-thousand-square-foot store. I have an almost obsessive quest for excellence in detail and execution.

INTERVIEWER

What are the factors that go into the buying decisions you make?

YAMAZAKI

For a buyer in a store, I think it’s helpful trying to envision where a book will be in the store: How is it going to fit on your shelves? Will it be face out, spine out? Will you display one copy, five copies? How many linear feet do you have to fill in the particular area where it belongs? Our most conventional shelving is poetry—A to Z—but almost everything else is distinctive, not just in naming, but in how the books are in conversation with each other. Should we arrange it regionally, break continents down by country? There are many legitimate approaches. What we excel at is that we are able to have this shimmering conversation. You can only put in thirty-three thousand titles. We carry 1.3 copies per title. It is so easy to get into a backlist buying frenzy and make it very tight to shelve. That section is already at 120 percent capacity. My colleagues are ready to kill me because it takes them ten minutes to shelve two books.

INTERVIEWER

And you have to be mindful of the browser’s experience when the shelves are that tightly stocked.

YAMAZAKI

Because there are so few face-outs, you have to be willing to explore, to invest time and curiosity, and hopefully you’ll be able to come back and start to get a sense: when you see a colophon for a certain publisher, does that excite you? Is there a conversation happening in this section which intrigues you? You’ll be able to create your own personal library in this bookstore that is forever changing. It will be part of a constantly shifting display. The surface of the ocean always looks the same. If you look at it closely, it’s always changing.

INTERVIEWER

Do you think in terms of what will help keep the store in business?

YAMAZAKI

You develop an internal map of measurements. I like to compare what we do to preindustrial navigators. We’ve always said, “I have a feeling about this, a feeling about that,” but now we’re combining our micro-observations with a bit of empirical knowledge. Now you can look at productivity per linear foot. We need to explore strategies for becoming fiscally sustainable while recognizing that the real goal is to guide our readers to a more expansive horizon. If you offer that portal, even if their initial impression might be that what you’re recommending is arcane or dense or difficult, if your assessment of the book is accurate, you will find a reader—not just a reader but a delighted reader.

INTERVIEWER

City Lights has taken notable risks in publishing, famously putting out Allen Ginsberg’s Howl and Other Poems in 1956.

YAMAZAKI

A poem like “Howl” puts complexity directly in our faces. It’s hard to put ourselves back sixty-seven years ago to see the level of courage that Allen had to write that poem and put himself out there. And for Lawrence to publish it. It’s still a challenging poem, all these years later. We’ve never been looking for comfort.

INTERVIEWER

Is that generative discomfort part of City Lights’s legacy?

YAMAZAKI

If we look at the streams of art and literature through the three hundred years of the development of capitalism, our task is to challenge those notions of authority, to challenge those strictures. The artists who have brought points of vision and beacons of hope within a capitalist system have always been problematic. The challenge to the reader, then, is how to parse all of that? How to develop your standards of aesthetics and morality? I feel very strongly that those cannot be received, they must be developed.

INTERVIEWER

Looking around the store, I wonder which books mean the most to you? Which ones do you go back to again and again?

YAMAZAKI

The Man Without Qualities I’ve started at least two times, but I never got past 750 pages. The book I reread the most is Moby-Dick. I would love to reread Karen Tei Yamashita’s novel I Hotel. Karen is one of the most gifted writers of this century. She never approaches a story the same way, which is one of the reasons, I think, that she’s not better known. I Hotel is ten novellas, each approached in a different way and yet each of them still tells the story of a small group of Asian American radicals in the late sixties. Of really significant books written in the twenty-first century, I think it is one of the most underread.

INTERVIEWER

Why do bookstores matter?

YAMAZAKI

We are about the process of discovery. There has never been a year where there hasn’t been something that has threatened our existence as an industry or made life as booksellers challenging. Some of the most exciting and challenging bookstores are no longer with us. I’m thinking of Midnight Special in Los Angeles, St. Mark’s Bookshop in New York, Hungry Mind in Saint Paul, Minnesota, and Cody’s Books in Berkeley. Not to be able to go to those stores any longer, at least in my topography, makes the world much smaller.

Three Lives in the West Village of New York City and the Green Arcade in the Hub neighborhood of San Francisco were the two jewel-box bookstores that bracket the continent. They were both wonderfully expansive and deep—Three Lives still is!—despite what many of us would think of as confining spaces of six hundred to eight hundred square feet.

INTERVIEWER

And yet we’ve also seen a lot of stores open in recent years.

YAMAZAKI

Yes! To see Word Up or Mahogany—or the changes at Point Reyes or East Bay—those are amazing stores that give me hope. Any time I walk into a store that has relatively new leadership I feel delight. Each store has its particular environment. It’s hard to articulate. The world disappears except for those eight hundred square feet. Each store has its own way of embracing you, embracing the reader, and creating a sense of the universe expanding. For anybody curious and interested in printed matter, the more bookstores you go into, the more you’ll realize how many different ways there are to be curious. That helps us set a foundation to be more knowledgeable about the world we inhabit. At a great store you can look at twelve well-selected, serendipitous linear inches and find a universe.

From Reading the Room: A Bookseller’s Tale, to be published by Ode Books in April.

February 16, 2024

Porn: America Moore, Chloe Cherry, Bianca Censori, Maison Margiela

Screenshot of Baz Luhrmann’s movie for the Maison Margiela Artisanal Collection.

America has a perfect round ass. We watch her mount a McMansion staircase from a low angle, the framing as deliberate as it is haphazard. The camera is handheld. America has been ironing; the green polo shirt she was pressing, however, looks like it was made from the kind of polyester blend that’s spared wrinkles no matter how badly you treat it. She carries the green shirt in one hand. With the other she grips the metal railing for balance. Her stilettos click loudly on the terra-cotta tile. Each step is measured. In the background, a sparse but funky beat.

The home in which America Moore performs is Mediterranean, or maybe Tuscan. The walls are a luscious cream with butterscotch undertones. Iron balusters with rounded knuckles adorn a winding staircase spanning at least three floors. The statement windows flanking the staircase are tall, narrow, and arched. The camera struggles to compensate for the sunlight beaming through them, resulting in blown-out portions of the image. America disappears momentarily behind a support beam that’s been drywalled over and painted the same tea-stained-paper shade as the walls. There’s a potted fern at the edge of the frame.

The action between America and her costar remains contained to the staircase, though we catch glimpses of a living room suite beyond the fern. Two cream sofas with wooden feet are arranged opposite each other, creating a conversational setup. Between them is an oval coffee table placed on a rectangular area rug that’s an ebony shade of brown. In some frames, in which just a corner of the rug is visible, it could be mistaken for soil strewn on the tile floor. It’s difficult to discern the material of the coffee table, as one of the decorative objects resting on it produces a glare that obscures most details. Perhaps it’s polished mahogany. The configuration of furniture positioned to face the table includes a Biedermeieresque upholstered stool the performers also avoid, though it is perhaps the piece that would best accommodate a scene. We know America doesn’t live here. Most likely someone has rented the house for the shoot.

—Whitney Mallett

As in the teen TV drama Euphoria, whatever plot there is in porn is insubstantial. Personally, I always let the pool boy say his lines to the bored housewife because I enjoy this artifice in the same way I do the lead-up to a real kiss: no matter what’s said, I know what’s going to happen. Chloe Cherry does, too. Every day at 11:11 and whenever Cherry finds a penny on the ground, she repeats a mantra of gratitude: “I am wealthy, I am healthy, I am thriving, I am rich, I am famous, I am loved.”

Cherry was born not with that SEO-friendly nom de plume but under the Christian name Elise, in the famously Amish region of Lancaster, Pennsylvania. Souvenir shops in Lancaster are stocked with bonneted, faceless dolls, which the Amish give to little girls because, per tradition, “all are alike in the eyes of God.” This is the material culture against which the contrarian Cherry chose to exaggerate her already giant facial features: eyes, teeth, cheeks, lips.

Cherry starred in an adult parody of Euphoria before joining the actual show as the streetwise, dope-sick sex-trafficking victim that brought her from Pornhub to HBO. She says this had nothing to do with her casting. This frictionless self-invention through porn reminds me that women are magical, sex work is work, and life is a gift. The camera adores Cherry not because she’s pretty and skinny but because she has an unbeatable attitude, and she’s better than any of her peers at showing it a good time. Perhaps work can love you back!

One gets the sense watching Cherry that she is at once laughing and fucking her way to the bank, her good humor evident in the impishly titled She Is Sunburned but Still Horny, a film she wrote and produced herself. When Cherry is cumming she often mimics ahegao, an expression of pleasure derived from Japanese hentai, crossing her eyes in a heavenward gaze and letting her long tongue drape from her mouth. It looks so good on her, even though it’s not the immediate physiological expression of an orgasm, but rather a reference to cartoons. Is all sex acting? No, but great sex is. Are the stakes of sex higher—is sex realer—when the camera intervenes? Definitely, yes. What’s a nympho to do in this world? Live her best life.

It should be said that Cherry makes some rookie errors on Euphoria, her TV debut. Her emotional range is restricted to one doe-eyed, vacant stare, an incredulous look whose function is to seduce. She’s incredibly good at making that face, and it’s fun on the show because Euphoria is a poor vessel for realism. A heroin addict who never nods off, Cherry as Faye cannot help but break the fourth wall: It’s me bitch, the chick from Naughty Book Worms Vol. 57. When we watch Cherry play a hooker on HBO, we are in fact watching her get off on how easily fame can come to hot girls who fear nothing. Which is also what she’s getting off on in, say, Two Cocks are Better Than One.

—Signe Swanson

The best thing to happen so far in 2024 is Kanye West’s January 6 Instagram birthday tribute to Bianca Censori: a (since-deleted) series of posts showing his “super bad iconic muse inspirational talented artist masters degree in architecture 140 IQ” wife in an array of outfits that occasioned the Page Six headline “She’s enslaved to him.” (Actually, most of Censori’s styling seems to be done by her longtime best friend, Gadir Rajab, and the article concedes that “not all think Censori is under West’s mind control, with some noting that she is an adult and can think for herself.”) The main styling concept for Censori seems to be, simply, “no pants this year,” but yes to gimp masks, full-body tights, and small strips of black tape. West himself has been favoring all-black outfits that say “POLIZEI.” People are so mad! A couple of weeks later, West posted a paparazzi photo of Censori getting into a car, wearing a camisole that said “WET” (since revealed as a Yeezy product—twenty dollars). The paparazzi pic is a genre with which we’ve mostly lost touch; instead, we see celebrities on Instagram, the medium with which West’s ex-wife, Kim Kardashian, is synonymous. But all of Censori’s best outfits—memorably, the purple pillow held strategically over her midsection on one outing in Italy; or the stuffed animal she clutched to similar ends at a party in Dubai—would be aesthetically and sexually impotent were they presented to us within her home. Their impact comes from the fact that she actually wore that, in public! Never mind that West, of course, turned out to be the one directing the photographers waiting outside that tanning salon. At a time when our image culture is saturated by the uberpornographic yet wholly unsexy selfies of the Kardashian-Jenners, “real” moments of direct-to-consumer domesticity staged in their mansions, Censori’s papped pictures shows us that the erotic actually requires exteriority.

I thought of Censori and West while watching footage of John Galliano’s 2024 Margiela couture show, a thirties-inspired spectacle presented on the last day of Paris Couture Week this January. If the collection itself, which hinged on the ultratight corsets also favored by the couple, was a thesis on clothing-as-fetish-object, the runway show, like “WET,” was an homage to streetwalking. The evening began with a black-and-white film interlacing a series of soft-core vignettes (bondage via corsetry, a street chase following a passion-fueled jewelry robbery), out of which the first model seemed to literally stumble, appearing before the audience, breathless, as the film’s thief-protagonist. The models who followed walked jerkily, as though filmed in the low frame rate of an old silent movie. This was a runway fantasy situated not in the past, but within film itself. Galliano’s primary inspiration was Brassaï’s voyeuristic photography of Parisian nightlife; in the show’s faux-speakeasy setting, the insistently anachronistic glare of the audience’s own cameras rendered every onlooker a street photographer. Surrounded by iPhone screens, the models’ prosthetically cinched waistlines recalled not so much the century past as the surgically enhanced hourglasses of the Kardashians. It was these moments—in which the contemporary was made to appear in the past, and vice versa—that gave a real edge to what might have otherwise have felt like a cute historical cosplay. Like West, Galliano tells us that fashion requires a crowd. It does not take place at home. Although his show was billed as “a walk through the underbelly of Paris, offline,” it reads as a canny commentary on the present articulated through outmoded technologies, as well as a reframing of the “social” medium as explicitly “public.” Both the Margiela collection and West-Censori’s styling project were meant to be sexy, which they are. But they’re exciting because they seem to signal, finally, a cultural shift: not only out of the 2016-era suppression of sex but back into the world, back into mediation, and away from false interiorities and intimacies of all kinds. At least, that’s my fantasy.

—Olivia Kan-Sperling, assistant editor

February 14, 2024

My Year of Finance Boys

Sg1959, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

I shouldn’t have been surprised that the hedge fund analyst knew me better than I knew myself. It was his job to predict distant developments, covert motives, hidden risks, and shortly into our brief relationship he turned his powers of divination on me. After I told him I was writing a novel about finance, he suggested that I’d been drawn to him partly for mercenary reasons: that I was, in a word, dating him for research. He took it in stride—he lived and breathed all things mercenary—but he did issue a polite warning.

“Never put anything I tell you in writing,” he said.

I’d like to think that, in his predictive genius, he also knew I would eventually ignore this warning.

***

The hedge fund analyst, whom I’ll call Jake, was the last in a string of finance boys I dated during a peculiar if productive period of my life. Almost as soon as I’d embarked on my novel about finance, I’d begun scanning dating apps for Patagonia vests and Barbour jackets. I wanted investment bankers, private equity associates, traders. I maintain that my motives were not as Machiavellian as Jake would go on to imply. I’d decided my novel would treat the technicalities of finance lightly, and I was already doing research sufficient to my purposes: auditing finance classes at the university where I was a graduate student, reading textbooks, conducting interviews. But Jake was probably right that my creative and libidinal impulses became, for a time, precariously interfused.

My interest in finance men as romantic material was as mysterious to me as my interest in finance as material for a book. I’d never earned enough for money to be anything but a source of panic. I had no idea what a derivative was and thought bear and bull meant the same thing. The distinction between a 401(k) and a Roth IRA was lost on me and in any case irrelevant because I had neither. And yet at some point during my years in New York, I became curious about the world of finance, then dazzled by it, and then—as my interest concentrated itself on the men who operated its levers—transfixed. Maybe the political convulsions of 2016 had awakened my class consciousness and spurred me to learn more about the people who shuffled the world’s capital. Maybe, as I neared thirty, I’d grown tired of financial precarity and subconsciously begun a search for a mate who would ease my misery. Maybe I saw in these men an obscure point of recognition. All I knew was that my curiosity would persist until I satisfied it.

There was no shortage of finance guys on my dating apps of choice, and they made themselves readily discoverable. On Tinder, Bumble, and Hinge, they often cited their employers and alma maters, and the moment I saw “Deutsche” or “Wharton” I swiped right. But even on Grindr, where a profile might be limited to a single mirror shot and a headline reading “Hung vers,” they were easy to spot—they had a signature, beguiling blandness. As I studied their neat haircuts and plain handsome faces, as I read their hyperminimalist messages (“Good u”; “Not much”) and inspected their skimpy bios (a Statue of Liberty emoji, a weightlifting emoji, sometimes a string of airport codes and accompanying travel dates), I tried to imagine my way into their evocatively dull lives. Seventy hours a week spent at a trading desk absorbing cold light and thin filtered air, lunch at Sweetgreen or maybe Dig, an interlude of bench presses and selfie replenishments at Equinox, dinner with the Bowdoin ’08 crew at Westville, an hour lying in bed messaging with the likes of me, then porn, then sleep. For reasons mysterious to me I thrilled to the idea of this moneyed monotony. I swiped some more. I asked when they were free.

On my very first outing, I had the fortune or misfortune to have many of my preconceptions confirmed. His name was Andrew, he worked at Goldman Sachs, and he was, to my jubilation, supremely boring. He’d gone to prep school in New England and college in California and now lived with roommates in the West Village, though he had his eye on a one-bedroom in a glass monstrosity in Tribeca. He was tallish, blond, inconspicuously good-looking, and responsibly dressed: the kind of person who lives in your memory only as a pleasing, gleaming outline, devoid of eyes.

He described his life in a white-noise murmur. He told me about a presentation deck he’d recently been tasked with putting together. He told me about the challenge of assessing new markets. He told me about his fraternity days, his weeks on Fire Island. He told me about his life’s dream. He wanted to clamber up the ranks of investment banking, he explained, and then start a company of his own. “I went to the Harvard of California, and now I’m at the Harvard of finance,” he said. “I want to do something unexpected.”

We were well into our second drink before it dawned on me that our date was not going especially well, and that we would almost certainly not meet again. I alighted upon this fact as if returning to the present, which raised the question of where I’d been. Andrew probably wondered the same thing. I’d mostly smiled at him and said little. I can’t imagine that I was emitting palpable pheromones. My interest in him was intense, but it was strange and abstracted, and very likely he saw me as a strange and abstracted person. But this didn’t bother me, and the fact that it didn’t bother me offered me the first clue as to the utter bizarreness of my experiment. I didn’t want to date these men, or at least not Andrew; I simply wanted to soak in their flavorless presence. I’d conjured a fantasy of a finance boy, and here he was, in the flesh, as radiantly banal and enthrallingly uninteresting as I’d expected him to be. I felt as if I were staring into a void whose howling depths could power not just one novel but a hundred.

After we said goodbye, I walked for a while through Midtown, staring up at the kind of corporate towers in which I imagined my fantasy finance boys worked. Everything in my aesthetic education had taught me to find these buildings ugly. They were cold, faceless, feats of commanding presence that conveyed nothing so much as absence, nullity given form and made brilliant. The more I stared up at them, the more I saw in their synthetic, frictionless surfaces echoes of Andrew’s synthetic, frictionless life, and the more I understood the novelistic challenge before me. I might be enchanted by the void I’d sensed in Andrew, I might be tickled by the idea of being such a vacuum myself, but a vacuum wouldn’t carry a novel. How to imbue an outwardly dull person with vibrancy? How to locate color and flair in a life of hollowness and obliterative efficiency? Why should a reader be interested in these finance boys? Why was I interested? I went back into the field.

There followed several months of what Jake would go on to call research. I had a fling with a former investment banker who now operated an Airbnb business that appeared to be illegal. I had a fling with an M.B.A. student who went to great pains to deepen his voice and who once showed up to my apartment at midnight with a twenty-ounce coffee. I had a fling with a McKinsey consultant who fired off work emails during our dates and who, I’m pretty sure, decided to break things off after he noticed that my bathroom ceiling was covered in mildew. I had a fling with a veep at Morgan Stanley who ended his days by watching My 600 lb. Life.

In each of these men I saw the same enigma. Something about their jobs seemed to have drained them of personality, blunted their curiosity, thinned out their speech, as if the drama of being a person had been shrunk to a matter of market efficiency, as if after thousands of hours of sitting in conference rooms and hunching before Bloomberg terminals they’d mistaken their spreadsheets, pitch books, white papers, and cash flow statements for materials out of which to assemble a soul. It didn’t occur to me then to wonder if I might be projecting this blankness onto them, or to wonder what purposes of my own such a projection might serve. All I told myself was that I had to go further. I went back on the apps. And then I met Jake.

On our first date he took me to a “speakeasy” in the Village, and I put that word in quotes because the whole bar was in quotes: conspicuously nondescript entrance, bartenders dressed in vaguely steampunk outfits pouring ingredients from brown glass medicine bottles, hazardously dim lights and lurid red accents meant to evoke, I supposed, the glamour of Prohibition. Jake bought us drinks and asked about my life with a clipped precision that made me feel as if I were sitting for a first-round interview. I waited for his eyes to glaze over at the mention of my writing, but to my surprise he listened attentively.

“I love that,” he said. “That’s fascinating.”

I shrugged. “You sit at a desk and type,” I said. “It’s all in your head. From the outside, there’s really not much romance.”

Jake had gone to law school and put in a few years at a corporate firm, but he’d soon left for his current hedge fund, believing finance to be infinitely more engaging than the law. He loved ideas. He was delighted to be on a date with a fellow “intellectual.” He was hungry for book recommendations, though it became clear that his literary tastes tended toward the subgenre of TEDx: Daniel Kahneman, Nassim Nicholas Taleb, Yuval Noah Harari. And yet of all the finance boys I’d gone on dates with, Jake presented the most serious challenge to my preconceptions. He had a fitful, furtive, vaguely paranoiac demeanor, and the more he drank, the more his eyes shone with a searching, apprehensive need. He was a person, in other words, intensely so. Three hours later we were back at his apartment.

All evening Jake had courteously answered my questions about his work, but now he deflected. He didn’t want to work in finance forever, he said. He’d organized his life according to a program of delayed gratification. He’d opted for an “inexpensive” apartment ($1,800 a month) so that he could focus on paying down his law school loans and funding his 401(k). He hoped to land enough sensational deals now to obviate the need for full-time employment and pave the way for an early semiretirement. He opened his laptop and showed me a dream house he’d recently spotted on Zillow: a glass-and-concrete mansion perched on a bluff in the Rocky Mountains that was going for $26 million. The house wasn’t to my taste—it seemed like the home of a Dracula decked out in Patagonia—but I certainly understood the fantasy. I too entertained scenarios in which I sold a book for a mint and escaped to some beautiful, terminal destination: a place whose austerity would complement the austere labor, the unromantic sitting and typing, that had gotten me there; a place whose solitude would give outward form to the solitary headspace in which I worked; a place where I could assume what I suspected was my natural state and be alone.

Jake shut the laptop and looked at me with daunting candor. “I’ll see you again,” he said, “right?”

I knew at once that Jake was asking of me something more complicated than I’d been prepared to give to any of my other finance boys, and for a moment I hesitated. But then I said yes, and when he asked me the same question after our next date I said yes again, and by the end of the month he was calling me his boyfriend.

I enjoyed having a “hedge fund boyfriend.” I told my writer friends about him and luxuriated in their reaction, a pleasing mixture of disgust and titillation. I thought about him while I sat writing alone in my room, and the mere fact of my connection to him, to his scrubbed professionalism and lofty salary, seemed to take the sting out of the bleakest aspects of my life: the mice that were forever darting out from under my kitchen cabinets, the roaches that were forever scurrying out from under my drying rack, the money that was forever disappearing from my checking account. When I walked through the city with Jake at my side the corporate buildings overhead seemed less alien. I felt like a participant in their ugly force in a way that I never had before. I besieged Jake with questions. I looted his bookshelves for finance explainers and investing guides and took notes. I studied his clothes and replicated his drink orders. I felt buoyant, like I’d stepped outside of myself, into that zone of nonself where, as a fiction writer, I most loved to be. If I never took the gradations of our relationship too seriously, it was because I never thought of myself as doing anything other than playing.

Very soon, however, Jake and I encountered our first point of friction. Jake liked to go to upscale restaurants, but he did not, despite his awareness of the vast difference between our incomes, believe he should pay for me. Between my graduate teaching stipend and my freelance work I made about $40,000 a year. I couldn’t keep dropping seventy-five dollars every time we went out to dinner.

“I’m wondering,” I said to him one night, “if maybe we can introduce some variety into our hangouts?”

Jake looked at me, all curiosity.

“Maybe we don’t always have to go out to dinner?” I said.

“What would you like to do instead?”

“Maybe we could eat more casually?”

The light of understanding shone in his face. “It’s too expensive,” he said.

“Maybe?”

He nodded. “I’ve actually been thinking,” he said, “that dating you could have an incidental benefit for me. I’ve been trying to spend less money anyway.”

A chill settled on my skin. I didn’t love the idea of my poverty being an “incidental benefit,” but I’d been reading his books, writing down things he said, clocking his mannerisms and persuasions. I was aware that dating him had an “incidental benefit” for me too—and that in my case this benefit might in fact be the primary one—so I said nothing.

“Tonight,” he said, “we’ll go somewhere cheaper.”

Somewhere cheaper turned out to be the restaurant extension of a famous cheese shop. No single item on the menu was in itself particularly expensive, but the dining approach was “small plates,” and by the end of the meal I’d been confirmed in a long-held theory: that there is no class enemy more fearsome than a restaurant serving “small plates.” My half of the bill: seventy-five dollars.

There emerged other points of friction. On any given night Jake drank enough for three people, and keeping up with him had put me in a state of perpetual hangover. Our sexual chemistry, never robust, soon waned. Jake also took it for granted that he was smarter than me, which I didn’t mind; in many respects he was. But I’d grown tired of his habit of subjecting me to longueurs about behavioral theory and defenses of his centrist politics. His grinding work stress often thrilled me, from a novelistic standpoint as well as an erotic one, but at times it could be genuinely disturbing. One night before going to sleep he saw a belittling email from his boss—from what I could tell, it either concluded with or consisted entirely of the words “Google it”—and immediately he got out of bed to draft a reply. I told him to wait until the next day, but he ignored me, and when I got up to pee at four in the morning he was still out in the living room, in his underwear with the lights on, staring at his phone.

By far the biggest difficulty, though, was our growing mutual awareness that Jake cared about the relationship much more than I did. When his parents came to town he told me he wanted me to meet them; I gently declined. He proposed trips we could take together; I brushed him off. The more time we spent together, the more glaring the imbalance became. He looked at me moonily, pawed at me puppyishly, made abortive efforts to engage me in conversation. But I was cold and I was only getting colder. I’d withdrawn from him at some point, disappeared somewhere, and he was struggling to pull me back.

The problem, I knew, was that my writing was finally going well. The time I’d spent immersing myself in the lives of my finance boys had unlocked something. I’d landed on a vocabulary, a pitch, a momentum by which I could transform my rough outline and inchoate ideas into a living, breathing document. I woke up each morning in my apartment eager to get to my desk. All my energy, my attention, my interest and lust for life were reserved for those hours in front of my laptop. I somnambulated through my meetings with students, my dinners with friends, my nights with Jake. I was happy, and to protect my happiness I presented the world with a flatness of expression not unlike that of so many of my finance boys. What I’d said to Jake on our first date was true. It’s all in your head.

It was in this state of contented disengagement that I met up with Jake on what would turn out to be one of our last nights together. We went to dinner with a friend of his from law school. The friend was cheerful, animated, solicitous: he seemed to detect the frigidness between Jake and me and did what he could to inject the evening with warmth. But I looked at the menu and saw the same preposterous prices. I listened to Jake hold forth on various topics with the same heedless, patronizing egoism. I looked out the window and envied the passersby. I knew it then: the experiment was over.

When we returned to his apartment Jake and I had our first full-on fight. I don’t recall the particulars, but it was essentially a recapitulation of my familiar complaints—yet again he’d talked over me, yet again he’d shown insensivity by taking me to a restaurant beyond my reach. But even I knew my grievances were arbitrary, disconnected almost totally from the base truth: I’d lost interest in him.

He apologized, defended himself, apologized, defended himself, but the more he talked, the more he seemed to see the conversation’s futility. Eventually he put his face in his hands, bent forward, and began to sob. His crying had a programmatic, theatrical quality, and I suspected that he was simply pretending, that if I pried his hands from his face I’d see no tears. But this did nothing to diminish my pity. Fictional tears are no less desperate than real ones; pretending has a sadness all its own. If my time as a fiction writer, if my year of play-dating finance boys, had taught me nothing else it had taught me this.

I should mention here that the reason Jake and I had gone out to dinner was that it was his birthday.

***

Our parting was amicable. We agreed to remain friends. Jake said he hoped he could still bother me for book recommendations, and I said I’d be disappointed if he didn’t. But a few days later, after the pangs of nostalgia and regret had largely abated, I returned—with a deliberation that enlivened me but had also begun to frighten me—to my novel.

I wrote ferociously, developing a plot around a finance student who flunks out of investment banking in part because of the weight of his imposter syndrome and his stubborn self-alienation—his inability to square the performance of a self with the work of being a real human being. Yes I was interested in capitalism, in class, in money’s outsize role in politics, and yes these were serving as the thematic buttresses for my book. But my fascination went deeper, and now I looked it in its strange face. The hollowness I’d sensed in my finance boys, I saw, that I’d sometimes invented where it didn’t exist, was really my own. And the emptiness I’d attributed to the world of finance was really the emptiness of the world I knew best.

In Jake’s mind the life of a writer had a color, a vibrancy, a flair. But to me it was an almost inhumanly cold endeavor, and I treasured it not despite but because of this. I never felt freer, never more powerful, than when I was hovering in the thin ether of pure sentience, a nonself in a nonplace, driving my characters to delight and destruction, orchestrating their financial ruins and romantic paroxysms from the safety of my anonymous omniscient perch. I thought of my time in that nonplace as my “real life,” and when I was in the grip of it I had little to offer the three-dimensional world or the people around me. The book, I knew, would take years to finish, and I resigned myself happily to an extended stay in that zone of detachment. Why I craved this detachment, and whether my desire for it was the cause or the effect of my decision to be a writer, were questions I couldn’t then answer, and still can’t.

***

Almost exactly a year after our breakup Jake surprised me with a text: Would I come to his birthday party? I hadn’t spoken to him in months, and I’d quit my habit of seeking out men in the field. But I’d be lying if I said I didn’t still harbor some residual curiosity. I imagined the crowd, felt my skin tingle, and said yes.

Jake had since moved to a freshly constructed tower in Midtown that, from the street, I would have taken for an office building. I rode the elevator to the top-floor event space he’d reserved, hung my jacket on a rack, and walked into a room that looked like a vast operating theater. Double-height ceilings, blinding white walls, lights so bright I found myself squinting. The crowd was modest but respectable: thirty or forty people, some standing by the floor-to-ceiling windows, others queuing at the bar, where two shirtless muscle boys poured drinks. I spotted Jake, but he was holding court among friends, gesticulating wildly to titters of delight, and I decided to visit the bar.

There I ran into Jake’s law school friend, who caught me up on everything I’d missed. Apparently at some point in the past year Jake had become very rich. I assumed some phenomenal deal had gone through. “We used to be at the same level,” the friend said, “but now—now.”

Once I’d retrieved my drink the friend guided me toward a circle of very tall, very beautiful gay men. To judge by the Teflon sheen of their faces every one of them had undergone Botox. They introduced themselves and then promptly resumed their conversation, which concerned shoes. They took turns placing their feet at the center of the circle and basking in remarks of approval. I looked back at Jake, but he was still regaling his friends. I heard one of the beautiful men say “Bottega Veneta” and walked away.