The Paris Review's Blog, page 31

May 7, 2024

Second Selves

Vincent Van Gogh, Oleanders, 1888. Public domain.

I.

Jill Price has remembered every day of her life since she was fourteen years old. “Starting on February 5, 1980, I remember everything,” she said in an interview. “That was a Tuesday.” She doesn’t know what was so special about that Tuesday—seemingly nothing—but she knows it was a Tuesday. This is a common ability, or symptom, you might say, among people with the very rare condition of hyperthymesia—excessive remembering—also known as highly superior autobiographical memory, or HSAM. All sixty or so documented cases have a particular, visual way of organizing time in their minds, so their recall for dates is near perfect. If you throw them any date from their conscious lifetimes (it has to be a day they lived through— hyperthymesiacs are not better than average at history), they can tell you what day of the week it was and any major events that took place in the world; they can also tell you what they did that day, and in some cases what they were wearing, what they ate, what the weather was like, or what was on TV. One woman with HSAM, Markie Pasternak, describes her memory of the calendar as something like a Candy Land board, a winding path of colored squares (June is green, August yellow); when she “zooms in” on a month, each week is like a seven-piece pie chart. Price sees individual years as circles, like clock faces, with December at the top and June at the bottom, the months arranged around the circle counterclockwise. All these years are mapped out on a timeline that reads from right to left, starting at 1900 and continuing until 1970, when the timeline takes a right-angle turn straight down, like the negative part of the y axis. Why 1970? Perhaps because Price was born in 1965, and age five or six is usually when our “childhood amnesia” wears off. Then we begin to remember our lives from our own perspective, as a more or less continuousexperience that somehow belongs to us. Nobody knows why we have so few memories from our earliest years—whether it’s because our brains don’t yet have the capacity to store long-term memories, or because “our forgetting is in overdrive,” as Price writes in her memoir, The Woman Who Can’t Forget.

Price was the first known case of HSAM. In June of 2000, feeling “horribly alone” in her crowded mind, she did an online search for “memory.” In a stroke of improbable luck, the first result was for a memory researcher, James McGaugh, who was based at the University of California, Irvine, an hour away from her home in Los Angeles. On June 8, she sent him an email describing her unusual memory, and asking for help: “Whenever I see a date flash on the television I automatically go back to that day and remember where I was and what I was doing. It is nonstop, uncontrollable, and totally exhausting.” McGaugh responded almost immediately, wanting to meet her. Her first visit to his office was on Saturday, June 24. He tested her recall with a book called The 20th Century Day by Day, asking her what happened on a series of dates. The first date he gave her was November 5, 1979. She said it was a Monday, and that she didn’t know of any significant events on that day, but that the previous day was the beginning of the Iran hostage crisis. McGaugh responded that it happened on the fifth, but she was “so adamant” he checked another source, and found that Price was right— the book was incorrect. The same thing happened when Diane Sawyer interviewed Price on 20/20. Sawyer, with an almanac on her lap, asked Price when Princess Grace died. “September 14, 1982,” Price responded. “That was the first day I started twelfth grade.” Sawyer flipped the pages and corrected her: “September 10, 1982.” Price says, defiantly, the book might not be right. There’s a tense moment, and then a voice shouts from backstage: “The book is wrong.”

McGaugh and his research team also asked Price to recollect events from her own life. One day, “with no warning,” they asked her to write out what she had done on every Easter since 1980. Within ten minutes, she had produced a list of entries, which they included in the paper they published about Price, or “AJ,” as they called her in the case notes, in 2006. The entries look like this:

April 6, 1980 9th Grade, Easter vacation ends

April 19, 1981 10th Grade, new boyfriend, H

April 11, 1982 11th Grade, grandparents visiting for Passover

April 3, 1983 12th Grade, just had second nose reconstruction

It continues through 2003. The team was amazed, in part because the date that Easter Sunday falls on in any given year varies so much, and in part because Price is Jewish. McGaugh’s team was able to verify the content of the entries because Price has kept detailed journals since 1976. She’s protective of the journals; she doesn’t like anyone to read them and she doesn’t like to read them herself. But she showed them to the researchers, and she showed them to Barnaby Peel, the director of a 2012 documentary about hyperthymesia. The journal has “everything, everything, everything, everybody, everything,” she tells Peel in the film. It’s written in tiny print on calendar-grid pages held together with paper clips. “I don’t like lined paper,” she says—it feels too constricting. He asks her how often she rereads it, and she says, “I don’t reread any of it … I don’t need to, I don’t want to.” She’s defensive on this point because in 2009 the professor and science writer Gary Marcus wrote an article about her in Wired that she hated. In it he claimed that her incredible memory was really a form of obsessive-compulsive disorder, and the object of obsession her own life: “Why is her memory of her own history so extraordinary? The answer has nothing to do with memory and everything to do with personality. Price remembers so much about herself because she thinks about herself—and her past—almost constantly.” He noted that “one simple method” of improving one’s memory is keeping a journal. The implication, for Price, was that she was using her journals as a crib sheet, a study aid to memorize her days. “I don’t write this to remember,” she says to Peel. “I write it so I don’t go crazy.”

Hyperthymesiacs are prone to this kind of externalization, keeping some kind of ship’s log to document their memories. Aurelien Hayman, a Welsh student who was twenty at the time he was featured in Peel’s documentary, covered the walls of his bedroom with snapshots. Hayman thinks of photos as “the closest you can get to making a memory an object.” A picture is “a concrete memory”—a kind of verification that persists into the present and exists outside the head. Hayman’s memories, like those of others with HSAM, are already highly visual, anautomatic memory palace. “It’s like I could get a diary for 2009 and write it if I wanted to, retrospectively,” he says—he can see the “imaginary pen writing in events in this sort of mental calendar.” Bob Petrella, a stand-up comedian and TV producer, has a scrapbook-like album he calls by the recursive acronym B.O.B., “the Book of Bob.” He didn’t write it in real time, like a diary, but re-created it from memory in 1999. It includes highlights from his life and a ranking of years from best to worst; his favorite year was 1983, and then 1985 and 2004 are tied. Petrella clearly takes joy in the book and in his memories, unlike Price, who, by the time she was in her thirties, when she wrote to McGaugh, was deeply depressed and overwhelmed by her memories—by their volume, their hyperspecificity, their irrepressible immersiveness. Everyone has cues that will trigger certain memories, but for Price the cues are constant and the memories inescapable. “It’s as though I have all of my prior selves still inside me,” she writes in her memoir. If anything reminds her of a bad day, essentially she has to live the day again. She feels she is in those moments—living both the past and present, like a “split screen”—and the pain still hurts. She often falls into a pattern that she calls “Y diagramming,” going back over her choices and all of their consequences: “If I hadn’t done this, then that wouldn’t have happened … It has instilled in me an acute, persistent regret.” It’s the line of causation that haunts her—she can see all the causes going back for forty years so clearly. Hyperthymesiacs can seem to get lost in the past; the remembering takes so much time. (Borges’s “Funes the Memorious” is a fictional hyperthymesiac: “He could reconstruct all his dreams, all his half-dreams. Two or three times he had reconstructed a whole day; he never hesitated, but each reconstruction had required a whole day.”)

There have been periods when Price stopped journaling for a while, but eventually “the swirl” in her head, the cascade of days, would get out of control and she would realize she “had to go back and get all of that time down.” She’d then reconstruct the missing time day by day after the fact—she remembered the details whether or not she had written them down. It happens, the remembering, with no conscious effort. The journal is “a physical and emotional reassurance that the event really happened,” she writes. “I can’t accept living with just the memory. It has to be tangible—something I can hold on to physically, something I can handle.” By “handle,” I think she means both that she can touch it and that, because she can touch it, she can process and accept it; she can cope with the overpowering reality of reality. Most of us can cope with it, insofar as we can cope with it, because the reality passes so quickly and then begins to fade. (I think of Rilke, the end of “Portrait of My Father as a Young Man”: “Oh quickly disappearing photograph / in my more slowly disappearing hand.”) McGaugh’s team believes that Price’s condition is not an ability—a skill one can develop, like the people who memorize digits of pi or the order of cards in a deck—so much as a disability. Her brain is very bad at forgetting—Price claims she has never misplaced anything, never once lost her wallet or her keys—but forgetting helps us live. Life, experienced once, in its excruciating fullness, is enough. As Ernest Becker writes in The Denial of Death, “full humanness means full fear and trembling.” “Life itself is the insurmountable problem.”

In her memoir, Price writes about “the memory bump,” the spike in autobiographical memories that most people have between the ages of ten and thirty, a time that includes lots of novel experiences and during which people are actively forming their sense of themselves. She cites a study described in Psychology Today: “If you ask college students to tell you their most important memories, and then surprise them six months later by asking again, they will repeat stories at a rate of just 12 percent … Even when asked specifically, ‘What is your first memory?’ subjects will rarely mention the same one twice.” So even though we have more memories during this period, or perhaps because we have more memories, the importance we assign to our memories is in flux. Our personalities, our selves, are likewise in flux; we choose the memories that serve our going narrative at the time. These narratives seem to be culture-bound; that is, they follow templates we absorb from the culture. Americans, according to the psychologist Dan McAdams, are drawn to redemption narratives, which frame the star as a hero, and to their counterpart—the “contamination narrative,” the idea that a certain event ruined everything afterward. Price thinks her memory changed irrevocably when she was eight years old and her father moved the family from New York City, where she’d had an idyllically happy childhood, to California for a job. But her highly specific memory didn’t really feel excessive, didn’t come to be a burden, until her twenties, when her life became unstable. Her mother almost died during surgery; her grandparents fell ill and died; her parents started fighting and eventually separated. So much change and strife, recalled in all its particulars, was too much for Price. She did not have the luxury of “choosing” to forget what she couldn’t accept.

There’s something strange about HSAM I never see mentioned. Price’s father was an entertainment agent—he worked for the man who discovered Jim Henson, and she used to go with him to tapings of The Ed Sullivan Show, before they moved to California. Her mother was a dancer in a troupe that appeared on Broadway and TV in the forties and fifties. Price’s first job was in TV, and she says she’s “a TV fanatic.” (In addition to her journals, she collects all kinds of objects and data from her life, and indexes the data: “In 1982 I started to make tapes of songs off the radio that I labeled meticulously by season and year, and I kept that up until 2003. I still have all of those tapes. In late 1988, I started making videos of TV shows, and I have a collection of close to a thousand of them. I also started an entertainment log in August 1989 in which I wrote down the name of every record, tape, CD, video, DVD, and 45 that I own.” If memory is an index, Price also has an index to the index.) When Barnaby Peel quizzes Aurelien Hayman about what happened on June 17, 2008, one of the things Haymen mentions (after clicking his tongue while thinking, a sound like a Rolodex, or the numbers turning over on an old-fashioned flip clock) is that Joan Rivers was thrown off a talk show for swearing. He can call up the dates that specific episodes of Big Brother aired—but bristles at any suggestion it means he’s “obsessed” with the show. He says it means nothing to him. Bob Petrella worked in TV. The actress Marilu Henner is another of the few known people with HSAM. She describes her memory of a year as something like “selected scenes on a DVD.” “It’s like time travel,” she says on a CBS clip. “I’m back looking through my eyes.” In a 60 Minutes segment from 2010, an interviewer asks her about a random episode of Taxi filmed more than thirty years earlier, in 1978. (The show ran for five seasons, 114 episodes.) She instantly remembers the dress she was wearing and one of Tony Danza’s lines.

Why are so many of the well-known examples of hyperthymesia involved somehow with TV? Is it because TV helped them discover one another? Or because people who watch a lot of TV were more likely to hear about Jill Price and Marilu Henner and realize they weren’t alone? I thought so at first, but now I wonder if HSAM is actually a post-TV condition, a disease of modernity—if it is a disease. (Henner is a happy person—maybe it helps that she’s rich and famous—but most people with hyperthymesia have difficult lives. For Alexandra Wolff, it feels as if “there are no fresh days, no clean slates without association.” Another person with HSAM, Bill Brown, told an NPR reporter that he’d been in touch with most of the known cases, and that all of them had struggled with depression and very few—only two—had maintained long marriages.) In his book The Week: A History of the Unnatural Rhythms That Made Us Who We Are, the historian David M. Henkin discusses the invention of the week. Unlike years (defined as the time it takes the earth to revolve around the sun) and months (which are based on the cycles of the moon), weeks are wholly man-made. The seven-day week has been around for centuries, but according to Henkin, television schedules helped solidify weeks as the stranglehold unit of our lives: “Saturday afternoon movies, weekly sitcom serials, and colossal cultural institutions such as Monday Night Football played a far greater role in structuring the American week than Wednesday theater matinees a century earlier, because they reached so many more people and faced so little competition.” Maybe TV, as trains did before it, fundamentally altered how we think about time.

Jill Price has said that when she dies, she wants her journals, those external memories, to be buried with her body or “blown up in the desert,” a literally Kafkaesque request. It’s a refusal of the hope of “life” after death. If someone else could read her journals, Price’s days might be lived through yet again—a prospect she must find gruesome and also unnecessary. (Freud reportedly once said, after fainting, “How sweet it must be to die.”) A journal is an effigy of the self, or else is the self, the self that exists because we create it. I am no longer sure, for the record, what people mean when they say that the self is illusory. Isn’t it here? Here where I sit, and in what I am writing? Isn’t it just my singular memory? Price understands this. The self dies with the self.

II.

I’m interested in the journals of writers (I suppose anyone who writes journals is a writer) as sites of self-loathing, of disappointment and failure. In his preface to A Writer’s Diary, the volume of extracts from Virginia Woolf’s diaries that he edited, Leonard Woolf remarks that, even taken in full, “diaries give a distorted or one-sided portrait,” because “one gets into the habit of recording one particular kind of mood—irritation or misery, say—and of not writing one’s diary when one is feeling the opposite.” Max Brod writes something similar in his postscript to Kafka’s diaries, which he published against his friend’s wish that they be “burned unread”: “One must in general take into consideration the false impression that every diary unintentionally makes. When you keep a diary, you usually put down only what is oppressive or irritating. By being put down on paper painful impressions are got rid of.” We can use as a kind of confessional, a place to expurgate our worst thoughts—so we don’t “go crazy.” Susan Sontag’s son, David Rieff, in his preface to Reborn: Journals & Notebooks, 1947–1963, identifies the two primary moods of his mother’s notebooks as “pain and ambition.” He writes of wanting to argue with her as he read them, to shout, “Don’t do it,” the way Sontag had seen the audience at a performance in Greece shout out at Medea. These editors were close to the authors, and must have felt their own impressions of the authors as people were more correct, more complete, than the version preserved in the diaries. But I’m not sure that follows. Aren’t the grim, unflattering things you only share with your diary in a way your truer self? The self you are alone, in what Sontag calls “the ecstasy of aloneness”? Yet she also writes, “I know I’m not myself with people … But am I myself alone? That seems unlikely too.” If there is no one self, you can never be yourself, only one of yourselves.

Sontag was prone to making lists of resolutions, lists of qualities she hated, lists of books to read and reread and of art and films to see—lists as a method of betterment. The very first entry in her notebook from 1947 is a list of beliefs, which begins:

I believe:

• That there is no personal god or life after death

• That the most desirable thing in the world is freedom to be true to oneself, i.e. Honesty

• That the only difference between human beings is intelligence

She was fourteen years old—and already conceived of writing as commitment to belief. In 1948 she writes: “It is useless for me to record only the satisfying parts of my existence—(There are too few of them anyway!) Let me note all the sickening waste of today, that I shall not be easy with myself and compromise my tomorrows.” This is writing as a way of making truth more true, if not creating truth out of nothing. Her notebooks, she writes, coincide with her “real awakening to life”: “This has been a necessity for me for the last four years: to document + structure my experiences … to be fully conscious at every moment which means feeling the past to be as real as the present.” The journals are a sort of supermemory, a more reliable and permanent record of experience, and of consciousness itself, which can’t quite be captured outside writing, with a photo album, say—one could only guess at the moods and arrangements behind the pictures. Some writers keep a notebook as asidecar, a paratext, while writing another book, to capture ideas and excess material and feelings aboutthe process. A diary, then, is the footnotes to the project of our lives, to the self as a project.

Ten years later, in 1957, Sontag writes this (unconscious?) revision to her list:

What do I believe? In the private life

In holding up culture

In music, Shakespeare, old buildings

She adds, this time, a list of things she enjoys (music, again; being in love; sleeping) and a list of her faults:

Never on time

Lying, talking too much Laziness

No volition for refusal

This distaste for talking, her own speech, comes up again and again: “The leakage of talk. My mind is dribbling out through my mouth.” “I am sick of having opinions, I am sick of talking.” “Important to become less interesting. To talk less, repeat more, save thinking for writing.” Conversation competes with writing. In 1954 and 1955, the middle years of her marriage to Philip Rieff, the entries are scant. “Speech is so much easier + more copious compared to the labor of keeping a journal,” she notes. She’s not writing much because she’s not alone—there is somewhere else for the language to go. (I remember, during the early pandemic, when we saw fewer people, I felt overburdened by language; all these things I would say, they were trapped in my mind. And writing them down made me feel less lonely, even if I didn’t think anyone would read what I’d written.)

But Sontag doesn’t value what’s easy, and would rather put the language into writing. “From now on I’m going to write every bloody thing that comes into my head … I don’t care if it’s lousy. The only way to learn how to write is to write.” In 1957, when she separates from Rieff, the notebooks fill up again—there’s no one else to observe her. Being self-conscious, she writes, is “treating one’s self as an other.” (That’s one of those thoughts I had thought of as mine.) In an entry labeled “On Keeping a Journal,” she writes, “I do not just express myself more openly than I could do to any person; I create myself. The journal is a vehicle for my sense of selfhood … It does not simply record my actual, daily life but rather—in many cases—offers an alternative to it.” The journal forms a parallel universe, a better reality. I am struck by Sontag’s ambition not just for fame and success but for real moral excellence. She wants to be a person who deserves success. She really wants to change.

In 1960, she writes a number of entries on a trait she calls “X,” or “X-iness,” the need to be liked, to please and impress other people, which she sees as very American, and which encourages her “tendency to be indiscreet,” to gossip and name-drop (“How many times have I told people that Pearl Kazin was a major girlfriend of Dylan Thomas? That Norman Mailer has orgies?”). X is why she’s a“habitual liar”—“lies are what I think the other person wants to hear.” “All the things I despise in myself are X: being a moral coward … being phony, being passive.” “People who have pride don’t awaken the X in us,” she writes; pride is “the secret weapon,” the “X-cide.” She hasn’t solved this problem in herself by 1961; she’s still telling herself “to smile less, talk less” … “not to make fun of people, be catty.” “Don’t smile so much, sit up straight, bathe every day, and above all Don’t Say It, all those sentences that come ready-to-say on the tickertape at the back of my tongue.” It’s hard to imagine, despite all this evidence, that Sontag was ever a suck-up or a people pleaser, someone who smiled too much or too ingratiatingly. I have watched many times, though it makes me squirm, a clip of her speaking to Christopher Lydon, in 1992, with utter and withering contempt. Her only smiles are pitying. She dismisses all his questions as unserious. We can see she’s achieved it, fame of course but also pride, the vanquishing of X.

Gide also made lists in his journals, lists of commitments and theories of living (“One ought never to buy anything except with love” … “Take upon oneself as much humanity as possible. There is the correct formula”) and “rules of conduct.” From an entry in 1890:

Pay no attention to appearing. Being is alone important.

And do not long, through vanity, for a too hasty manifestation of one’s essence.

Whence: do not seek to be through the vain desire to appear; but rather because it is fitting to be so.

He frequently chided himself: “I must stop puffing up my pride (in this notebook) just for the sake of doing as Stendhal did.” When Sontag read Gide’s journals, she identified so deeply with his thinking that she wrote, “I am not only reading this book, but creating it myself”: “Gide and I have attained such perfect intellectual communion … Thus I do not think: ‘How marvelously lucid this is!’—but: ‘Stop! I cannot think this fast!’ ” Delightfully, Woolf felt the same, reading his journals in 1934: “Full of startling recollection— things I could have said myself.” (When I mentioned this coincidence to my husband, John, he looked at me wide-eyed—“That’s how I’ve always felt.”)“Recollection” is an odd word, here— did she mean recognition? It suggests she remembers Gide’s thoughts, experiences Gide’s thoughts as memories, the way she does when rereading her own writing. (“To freshen my memory of the war, I read some old diaries.”)

Woolf, like Sontag, would periodically go through and annotate her old journals after the fact, adding comments and asides and corrections of a sort. In late October of 1931, she notes the updated sales figures for The Waves (“It has sold about 6,500 today … but will stop now, I suppose”) in the margin of an entry dated January 26, 1930, where she’d guessed “[it] won’t sell more than 2,000 copies.” To an entry about Arnold Bennett she adds: “Soon after this A.B. went to France, drank a glass of water and died of typhoid.” In an entry dated April 27, 1925, Woolf notes that The Common Reader has been out five days and “so far I have not heard a word about it, private or public; it is as if one tossed a stone into a pond and the waters closed without a ripple.” But she claims she is “perfectly content” with this silence; she cares less than she has ever cared. (I love Woolf’s continual insistence that she’s indifferent to her fame and her work’s reception. In response to a “sneering review” two months later, she assures herself, “So from this I prognosticate a good deal of criticism on the ground that I’m obscure and odd; and some enthusiasm; and a slow sale, and an increased reputation. Oh yes, my reputation increases.” Once she knew she had fame she found it “vulgar and a nuisance.” I love the vanity of writers, and of famous dead writers especially.) In that same April entry, she digresses: “My present reflection is that people have any number of states of consciousness: and I should like to investigate the party consciousness, the frock consciousness etc.” In the margin, she has added, at some point, “Second selves is what I mean.”

Who is Woolf lying to, if she is lying, in these diaries? Herself, a little bit, the second self that is the diary, and the future Virginia, who might as well be another person entirely. In 1919, she writes, “I am trying to tell whichever self it is that reads this hereafter that I can write very much better.” Later that year: “What a bore I’m becoming! Yes, even old Virginia will skip a good deal of this.” At the age of thirty-eight, she writes:

In spite of some tremors I think I shall go on with this diary for the present. I sometimes think that I have worked through the layer of style which suited it—suited the comfortable bright hour after tea; and the thing I’ve reached now is less pliable. Never mind; I fancy old Virginia, putting on her spectacles to read of March 1920 will decidedly wish me to continue. Greetings! my dear ghost; and take heed that I don’t think 50 a very great age.

It seems we can’t help but imagine an audience when we write. Because a journal makes the self external, the self counts as an audience. But I also think Woolf and Sontag, in saving their journals, just must have imagined that others might read them as well. They must have, because they loved reading writers’ diaries. Sontag read Kafka’s diaries. Kafka read Goethe’s: “Distance already holds this life firm in tranquility, these diaries set fire to it. The clarity of all the events makes it mysterious.” (The next day he writes, “How do I excuse yesterday’s remark about Goethe [which is almost as untrue as the feeling it describes, for the true feeling was driven away by my sister]? In no way.” For Kafka, contra Sontag, writing the thing often made it less true, reduced the verity of pure thought to lies. “Nothing in the world is further removed from an experience … than its description.” The words spoil reality.) Plath read Woolf’s: “Just now I pick up the blessed diary of Virginia Woolf which I bought with a battery of her novels Saturday with Ted. And she works off her depression over rejections from Harper’s (no less!—and I hardly can believe that the big ones get rejected, too!) by cleaning out the kitchen. And cooks haddock and sausage. Bless her. I feel my life linked to her somehow.” So did Eudora Welty, who quotes or, rather, misquotes from Woolf’s diary in her Paris Review interview: “Any day you open it to will be tragic, and yet all the marvelous things she says about her work, about working, leave you filled with joy that’s stronger than your misery for her. Remember— ‘I’m not very far along, but I think I have my statues against the sky’? Isn’t that beautiful?” Woolf’s exact quote is: “It is bound to be very imperfect. But I think it possible that I have got my statues against the sky.” (This makes me think of Czapski: “There’s nothing easier than to quote a text precisely … It’s far more difficult to assimilate a quotation to the point where it becomes yours and becomes part of you.”)

A journal—any writing—is a chance at immortality, or if not eternal life, at least a little more life, a little more after death. Rieff notes that his mother died “without leaving any instructions as to what to do with either her papers or her uncollected or unfinished writing.” It makes sense because she didn’t really believe she would die, as he describes in his own memoir of Sontag’s terminal cancer. He contrasts her death to Simone de Beauvoir’s mother’s death, which she called “a very easy death”—with no internet, and differing medical ethics at the time, Beauvoir’s mother died in ignorance of the severity of her illness. Sontag had no such luck, and though she knew intellectually how slim her odds of survival were, she couldn’t help but hold out hope, even inside or beside her despair, and continued to make lists and notes and plans for travel and projects, “fighting to the end for another shard of the future.” She was willing “to undergo any amount of suffering,” according to Rieff, for a chance at more life, this despite her depression: she “wanted to live, unhappy, for as long as she possibly could.” Woolf, although she killed herself, seemed also to believe she might not die—in 1926 she writes, “But what is to become of all these diaries, I asked myself yesterday. If I died, what would Leo make of them?” If! Ernest Becker would say no one really does or can believe it: “Our organism is ready to fill the world all alone … This narcissism is what keeps men marching into point-blank fire in wars: at heart one doesn’t feel that he will die, he only feels sorry for the man next to him.”

Woolf wanted her diary “to be so elastic that it will embrace anything”—as she had said the previous year of Byron’s Don Juan, that the poem had an elastic shape that could hold any thought that came into his head, or as she said of the new form of novel she’d begun in 1920, which became Mrs. Dalloway, a form with “looseness and lightness” that could “enclose everything, everything.” Like Jill Price’s journals, the journals holding “everything, everything, everything, everybody, everything.” A comprehensive diary exposes the near infinity of detail in a life, even a life as short as Plath’s—the index to Plath’s unabridged journals is almost thirty pages long and contains entries for apartheid, Louis Armstrong, the Aztecs, Brigitte Bardot, bees, Sid Caesar, Alexander Calder, Un Chien Andalou, circumcision, Marie Curie, demonic possession, the Detroit Tigers, Amelia Earhart, the Eiffel Tower, Paul Gauguin, Adolf Hitler, need I go on? Perhaps a life actually is infinite, like the points between zero and one on a number line. You could always make the journal longer, write in a finer degree of detail, add in more sense and observation, that is, if you had the time.

Woolf also wanted her published books to be more like the diaries. “Suppose one can keep the quality of a sketch in a finished and composed work? That is my endeavor.” This is part of the beauty of journals—they remain forever sketchy, with the un-worked-over magic of first drafts. “It strikes me that in this book I practice writing; do my scales.” This in 1924: “And old V. of 1940 will see something in it too. She will be a woman who can see, old V., everything— more than I can, I think.” Here is a bit of the tragedy Welty referred to. By 1940 life was very difficult for Woolf, and not only because of the war, though the war is heavy too, inescapable as atmosphere: “One ceases to think about it— that’s all. Goes on discussing the new room, new chair, new books. What else can a gnat on a blade of grass do?” Her friends’ deaths have been hard: “There seems to be some sort of reproach to me … I go on; and they cease. Why?”

“It’s life lessened”—less life overall; their deaths seem to sap life from her. After Roger Fry’s funeral, she writes: “A fear then came to me, of death. Of course I shall lie there too before that gate and slide in; and it frightened me.” (How like Berryman’s lines: “Suddenly, unlike Bach, // & horribly, unlike Bach, it occurred to me / that one night, instead of warm pajamas, / I’d take off all my clothes /& cross the damp cold lawn & down the bluff / into the terrible water & walk forever / under it out toward the island.”) Seeing more, knowing more, having more to remember—it all has a cost, a weight.

Toward the end of her life, Woolf seemed to begin to view death as release from the fear of death. She writes more and more of death. On Sunday, June 9, 1940: “I don’t want to go to bed at midday: this refers to the garage.” (“The garage” is where Leonard had stashed away petrol, for use in the case that Hitler should win.) “It struck me that one curious feeling is, that the writing ‘I’ has vanished. No audience. No echo. That’s part of one’s death … this disparition of an echo.” On June 22: “If this is my last lap, oughtn’t I to read Shakespeare? But can’t. … Oughtn’t I to finish something by way of an end?” The war, she feels, “has taken away the outer wall of security”; “no echo comes back”; “I mean, there is no ‘autumn,’ no winter. We pour to the edge of a precipice and then? I can’t conceive that there will be a 27th June 1941.” (There wasn’t, for her.) On July 24: “I make these notes, but am tired of notes, tired of Gide.” On September 16: “Mabel [the cook] stumped off … ‘I hope we shall meet again,’ I said. She said ‘Oh no doubt’ thinking I referred to death.” On October 2: “Why try again to make the familiar catalogue, from which something escapes. Should I think of death?” She tries to imagine “how one’s killed by a bomb”:

I’ve got it fairly vivid—the sensation: but can’t see anything but suffocating nonentity following after … It—I mean death; no, the scrunching and scrambling, the crushing of my bone shade in on my very active eye and brain: the process of putting out the light—painful? Yes. Terrifying. I suppose so. Then a swoon; a drain; two or three gulps attempting consciousness—and then dot dot dot.

In her very last entry, written on March 8, 1941, she seems almost happy. She’s been to hear Leonard give a speech in Brighton. “Like a foreign town: the first spring day. Women sitting on seats. A pretty hat in a teashop—how fashion revives the eye!” She recommits to Henry James’s command to “observe perpetually.” Like Sontag she imagines a future, a prescription for old Virginia: “Suppose I bought a ticket at the Museum; biked in daily and read history … Occupation is essential.” “And now,” she concludes, “with some pleasure I find that it’s seven; and must cook dinner. Haddock and sausage meat. I think it is true that one gains a certain hold on sausage and haddock by writing them down.”

III.

A friend of mine told me her journals are not retrospective, a record of time past—instead, they look forward, a record of plans and ideas and projections, sources of excitement and hope. I once wrote in a notebook, “I hate hope, and yet …” (And yet what—I need it? I don’t believe in free will, but I can’t help behaving as though I have it. In that sense, free will is automatic. It springs eternal.) I once wrote in a notebook, “Underlining books makes me want to return to them and reminds me of hiding ‘treasure’ (coins or candy) in my room as a kid, to forget and find later.” I think I use notebooks for the same reason, as a way of hiding “treasure” for myself, for old E. I record events sometimes, date the entries sometimes—on September 25, 2021, I wrote: “I remember, the night before John’s father died, they said, He’s doing a little better. He ate all his peaches.” On September 15, 2021, I wrote: “I’m starting to remember the bleakness of 2020 fondly—well, not the bleakness exactly, but the moments of non-bleakness—making a lot of banana bread. Huddling around a kerosene camp heater on Mike’s balcony. Xmas.” To be more exact, I recorded the memories, not the events. (Woolf, in 1933: “It’s a queer thing that I write a date. Perhaps in this disoriented life one thinks, if I can say what day it is, then … Three dots to signify I don’t know what I mean.”)

But mostly they’re undated, mostly they are thoughts out of nowhere. In 2021, according to my notebooks, I thought a lot about Sartre’s bad faith, or mauvaise foi—the moments when we recognize the anguish of our freedom, which he called “negative ecstasy.” Kierkegaard called it “the dizziness of freedom,” those glimpses of the way out of the trap. Why do we always look away and never take that path out? I wrote “INERTIA & UNCERTAINTY” in all caps at the top of a page. I wrote “THIS CONNECTION BETWEEN JOURNALS & MEMORY.” I put asterisks next to the interesting thoughts, the thoughts that wanted more thinking, a map to the treasure. Proof that thoughts were had. The disconnected thoughts are always me, are they not? Proof of continuity? “In the diary you find proof,” Kafka writes, “that this right hand moved then as it does today.” We need proof of our lives, and we need it while we live.

I wrote in August, as shorthand, “Memory—New Orleans.” I know what I meant by this. WhenI was nineteen years old, I went to Mardi Gras with my brother, my roommate, and several other college friends and got as drunk as I’ve ever been, so insensibly drunk that I famously spiked a frozen hurricane, which, according to most recipes, already has four ounces of rum, with more rum from a flask, and blacked out standing up, such that I recall coming to in the arms of a stranger wearing skull beads. The beads were little skulls, memento mori. Later I looked so green in the very long line for the bathroom at Café du Monde that they let me skip to the front. I don’t remember getting back to the hotel that night. The next day, my roommate, who was sharing a bed with me, told me that I’d puked on the sheets, so she’d yanked them off the bed and thrown them into the bathtub, and when she’d tried to pull the little decorative coverlet over us for warmth, I had told her, “They don’t wash those.” I swear this was the first time I ever heard that hotels don’t wash the coverlets—when my friend told me I had told her so. My drunken mind had knowledge I didn’t. When I told John this story, he didn’t seem surprised. I guess when you’re so drunk you aren’t even there, you really are someone different. (Dot dot dot.)

Elisa Gabbert is the author of six collections of poetry, essays, and criticism, most recently Normal Distance and The Unreality of Memory & Other Essays. She writes the On Poetry column for the New York Times, and her work has appeared recently in Harper’s, The Atlantic, The New York Review of Books, and The Believer. This essay is adapted from Any Person is the Only Self, which will be published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux in June.

May 3, 2024

Dream Gossip

From Alice Notley’s zine Scarlet #1. Digitized by Nick Sturm as part of Alice Notley’s Magazines: A Digital Publishing Project.

“We asked our contributors to send us their dreams; most did not. A few did. One sent us some & then withdrew (“censored”) one. Dreams have gossip value—containing what didn’t happen that was so salacious. We offer this column as a random sampling of events in the night world; if you want to use it to remark on the nature of the poet’s (or the painter’s) soul, that’s your concern. We’re afraid that dream happenings are mere more of what goes on,” wrote the editors of the first Scarlet zine, Alice Notley and Douglas Oliver, introducing their new column, Dream Gossip. The first one featured dreams by Joe Brainard and Leslie Scalapino; a later column was illustrated by Alex Katz and prompted an essay by Notley on what we can and can’t learn from dreams. (Dream Gossip ran between 1990 and 1991, in the five issues of Scarlet, all of which have been digitized by the scholar Nick Sturm and are available here.) This spring, Hannah Zeavin interviewed Notley for our Writers at Work series. To mark the occasion, we sent a similar prompt to some of our contributors and staff, and are reviving Dream Gossip this week only. Welcome to our sampling of events in the night world!

—Sophie Haigney, web editor

Dream, April 9, 2024: I am eating chicken wrapped in cabbage at a table in my apartment. A book is open, possibly Middlemarch. The phone doesn’t ring but I pick up a landline with a coiled cord, and as I stare at the lines of text a voice on the phone says, “Nice place, but do you always just go looking into other people’s apartments?” Muffled but distinct, Beethoven is playing in someone’s car down on the street as they wait at the light.

—Dan Poppick

I was walking with C., deeply aware I was running late for dinner with my mother. She said, “Just walk me a bit further.” I did. We must have been in New York, because of the way the street looked at night, like it has rained even when it hasn’t. Eventually tried to beg off politely, wincing, pointing to a watch that wasn’t there. Then she tied a black truss around me, and from the truss was a leash, which she tied around her waist. I tried to turn on my heels and make it to my dinner. Impossible, obviously.

—Hannah Zeavin

We are trying to make it across town. There are a few of us and I who am in the dream know that I know them but the I that is dreaming has never seen them. We are moving from place to place, trying not to get caught in the crossfire, but the half light through which we move from place to place, from cover to cover, is lit by laser fire. There are sides here and they are fighting but neither side is from this place, which is my reservation. Neither of the sides are from this place and we don’t know who they are but they are not from this place and we are trying to get somewhere. The grasses of the plains are gone and what has come is sand. There is sand everywhere and a hot wind blows and drifts the sand and we move across sand drifted like snow across streets and we hide in the shadows of wreckage and wait for a chance to move while the sides battle and laser fire lights up the sky which is no different in color from the ground. The wind is constant and hard and drifts the sand and we move and it is night. We are going across town for some reason. The pink-and-blue neon of a gas station canopy lights the distance.

—Sterling HolyWhiteMountain

One more way in which I am inadequate: I don’t dream, or barely, or if I do I don’t remember it. But surely, I thought, if I have to … To try to induce a dream I did some edibles. I was sitting around with friends. “What is the most important quality for a person to have?” I said, stoned. One said integrity, the other said generosity, I said bravery. Then I went to bed, woke up, nothing.

The love of my life so far—he gets to keep that title until I find another one, as it is not in my nature to fake it—used to wake up every morning and tell me his dreams. At the start I would literally watch him while he slept, and he liked to fuck me so much that he would ask me to get on top of him in his sleep (please?). By the end his snoring got so loud that I couldn’t sleep beside him anymore, and he dreamed mostly about me fucking somebody else.

Last week, I slept with a man, and then instead of leaving spent the night. I thought, maybe in the morning he will tell me one of his dreams, and I can steal it. No luck.

—Holly Connolly

I recently dreamed I’d made an ice cream cake to look exactly like the face of Karen Black, brought it to a party, and then became distraught when people tried to cut into it (the point was to let it melt!).

—Kate Riley

I dreamt I was in high school, at a statewide conference of the California YMCA’s Youth and Government program; in Fresno, I assume, because that’s where those conferences are held. I was standing in a large convention hall where an Irishman was making an impassioned speech. The woman standing to my left called him a faker. “That’s not a real Irish accent,” she said to me. “You can always tell.” In spite of her suspicions, I was doing this thing called spirit fingers, a gesture I remember from California Youth and Government which symbolizes enthusiastic agreement with whatever is being said. Spirit fingers is where you make typing motions with one hand while raising it in the air. Upon waking I put my arm down and found it was sore, and then I wondered for the rest of the day what the Irishman had so thoroughly convinced me of.

—Owen Park

My dream was a book that doesn’t exist. It was read aloud to me by a male narrator and illustrated with photo slides. Called August Is Back, it was an autobiography of a glamorous Jewish Italian woman, written in old age. Her passions were food and sex. She was voracious!

And for a reason—growing up, she’d had a dear sister who died young. This made the author of August Is Back lean into living fearlessly and sensually. While she was clearly fab, her writing was so abruptly erotic that I felt embarrassed. She described at length the moisture on linen sheets after sex, the winking drip of overripe plums on the branch, and the satisfying mouthfeel of the word “climax.” Even in my dream, I found it a bit much.

The final image was of her with her husband, holding hands in their garden. It was shown to me in black-and-white—one of the vignettes. I can’t remember if he was still alive or had already died. She herself was close to death, I understood. She wore a rumpled, plaid skirt over big calves. I woke up thinking, Huh!

—Rosa Shipley

He was sallow, aristocratic, fat. Half in the dark, his face appeared at the reckoning, festive. “You will feel a flatness,” he said to me, his skin an ashy blue. “Eat the fruit. You must … eat the fruit.” Had I gotten something wrong? Was I too impatient for wisdom? Did I abandon my commitments? Was I ungrateful for beauty when it faded too soon? Was my hospitality conditional? Was I made lazy by the long summers? Did I grow greedy for epiphany? Did I ask for mercy when I had withheld grace? Did I conflate freedom with narcissism? Was I caught delighting in the disgrace of others? Was my empathy self-serving? Was I frugal with forgiveness? Was I unmoved by violence? A muffled animal wail ripped out of me, but I was not conscious of making it. No sound came out. Strobe lights flashed, as if we were in a nightclub. Up until my reckoning began, I had planned to live life unrejected in love, and I assumed I would be envied by multitudes.

—Geoffrey Mak

I dreamt I couldn’t find my way back to the office once I had stepped out into the hallway. The corridor was no wider than a large desk, with dizzying spiral staircases, something straight out of Gaudí’s mind: pink walls made of clay, doors with drooping frames in bloody maroon. After hours going around in circles, I realized I did know how to get back in from the outside and turned in the direction I thought led to the exit …

—Nikita Biswal

Gene and I were in rehearsals for a stage adaptation of Batman. I’m not sure which episode. It was a musical, and we were told by the choreographer that we should fly, even though Batman doesn’t really fly—only Superman flies. Maybe we were supposed to be bats. Anyway, I’d never flown before, but I stood on one leg and leaned forward until my torso and my lifted leg were parallel to the floor, like in yoga. Then I picked up the other foot so that my whole body was in the air and started cruising around the stage. A huge triumph.

—Jane Breakell

Dream. The police commit me to a mental hospital. A year goes by. I’m standing near the front gate when a man in a brown security uniform tells me that he’s a time traveler sent back from the future to torture and kill me, and that the screams I’m about to hear from inside the hospital will be my own as I’m dying, and that this fact of my other self dying will be the perfect cover for my real self, me, to escape this hospital and join the time-travel police, which, he says, has been the plan all along. He’s smiling. As he tortures my first self to death inside the hospital and I hear my screams as I beg for mercy, my other self finds the hospital supervisor. I ask her what kind of plan this is. Why is it so convoluted? Why did it take a whole year? She laughs at me.

Dream. James has a black cow that loves me. It stands up on its hind legs to hug me, sing to me, and dance with me.

Dream. I have pursued a bird to the rooftop in a green leafy neighborhood of a big city. A famous cult leader wearing sunglasses approaches, moving from roof to roof. He calls out: “I like to sell drugs, and I also like to steal birds.” An eagle lands on a branch over me. I’ve never been so close to an eagle before. I am knocked flat on my back, transfixed by wonder. A jaguar leaps into the treetops. I wait for the hawk to attack the jaguar. Now a second jaguar struts up and sits on top of me.

Dream. Trepanning, beheading, vivisection, amputation, serrated knives. I am pursued down unfinished wooden stairs into a muddy basement. Upstairs, there are two wonderful golden owls.

Dream. Scott admires my “sphinx implant.”

—J. D. Daniels

May 2, 2024

Emma’s Last Night

Photograph by Jacqueline Feldman.

There had been concern when Jean and Emma got together that he was too serious, macho. I perhaps had it wrong that he had in art school driven to Chernobyl, uprooted a tree, and brought it back to France—a foreigner, I was capable of wild misunderstandings—but this was the story that had come to seem defining. Now he made a dance out of crumpling a wrapper, hopping up to throw it in the trash. He snapped his fingers to the music. It was cheerful music, music from my country though not from my era. In a city famous for ways of living developed, cultivated to exquisiteness, over centuries, we were engaged, that night, in a rare shabby tradition, that of the apéro dînatoire. Emma was throwing one ahead of moving in with Jean.

Possibly the tradition was not exclusively Parisian. “They do it systematically in Greece,” Jean said.

On a cutting board were resting chocolate bread from Chambelland, a slab of Comté, a “beautiful” radish Jean had brought, and chips: “I have chips because you said there must be chips for the feuilleton,” Emma said to me, referring to my plan to write about the evening. Having touched down that morning I was making such demands on top of being welcomed back. Stefania, who came late, brought sticks of crabmeat, olives, and a two-liter bottle of Coke.

Stefania was “a musician and artiste d’art vivant,” Emma said.

“Easier,” said Stefania, “I’d say artiste sonore, performeuse.” Romanian, she had been living in Paris for four years and liked it, though her own apartment was, like Emma’s, too small. “That’s the toilet?” she asked.

“It’s not very far from us,” Jean commented.

“Sorry,” Stefania said, “but I have need. Put the music back on.”

Emma’s boxes were piled two high on a bed she called “the sofa” and Jean called “the divan.” Plants remained unpacked and cast exaggerated shadows. She had done such a good job, remarked Haydée. “C’est vraiment très bien rangé.”

A mover, Patrice, would be there tomorrow. “He is an artist,” said Emma, “and his art is to sleep in his car.”

“He has to find a place to shower every day,” Jean said, reframing.

There would be furniture already, the apartment would be new to both of them, the furniture too heavy to get rid of. There was a table that Emma thought they might use a tablecloth on. Haydée accepted Emma’s phone to see a photo. “Oh but it’s fine,” she said. “It’s very good, Emma. But the chairs, you took them away?”

There would be, the next day, a great duty of transferring boxes, which I, arriving in the group’s life always just in time to catch the end of something, had been excused from (the mover, Patrice, who had a bad back, would drive).

Emma, as I raced to get down what she said , wished that she could have a note taker for all of her soirées. Haydée thought the company could stand to get a little bit more novelesque. “We should invent characters,” she said.

Raphaël called, as if freshly invented—but he was a high school friend of Emma’s, and someone who had been helpful lately, with the lease. His voice came through the stereo in the place of music.

“Ah,” said Haydée, “your guarantor!”

“My guarantor is coming!” Emma said.

“Emma is supposed to be his mistress,” Jean said to me, disgusted with the system that had left him off this document.

Raphaël, when he arrived, asked Emma if she didn’t feel nostalgic. She did, and this meant she had been wanting, for some minutes, to fill every corner of the space awaiting disuse with our movement. She wanted us to sing. “Il faut passer à l’action,” said Stefania. Raphaël made suggestions Jean found ridiculous. “Dylan,” scoffed Jean, “Brassens, ça fait rire.” They “made” him “laugh” in a bad way. But Raphaël was taking lessons, singing lessons. Here he offered up a song in Spanish. I taped some of all of this later to play it loud, its overlay the well- or ill-timed interruptive rustle, flaws by then like a mutation taken in my absence, not exactly like this.

My first day back even the weather was suggestive of a possibility, not only the necessity, of remaining present while in transit, while the flow goes on around you. Stasis, not activity, was the delusion. As signs read—outside, around the city—“TERRACE OPEN.” Trees that smelled bad were in flower, the canal was brackish, I lingered mesmerized by tulips out front of a Franprix. A woman called back to her son. I heard the question clearly. “Do you want hot chocolate,” she asked, “or lemonade?”

Reaching Emma’s building just as she was getting home I’d praised her for throwing a party at all. Packing took me up until the very last moment, always. “I remember,” Emma said, referring to a summer night when I’d stuck her with old clothes; we’d taken boxes of my notes to store at Hugo’s, her high school friend who’d introduced us. “It’s boxes,” she cautioned now, a nicety, as we climbed the curving stairs. “J’ai l’habitude,” I of course said in reply.

Jean, third to arrive, had not long after emerged rather suddenly, flushed and unkempt, from Emma’s bedroom, where he had been apparently only pretending to nap. He was “interested” in stories I was telling, he said to Emma and me, in a tone of apology, “as we only hear them episodically. It’s interesting.”

Jacqueline Feldman’s On Your Feet, a bilingual experiment, was published in March by dispersed holdings. Precarious Lease, an account of a Parisian squat, is forthcoming from Rescue Press this fall.

May 1, 2024

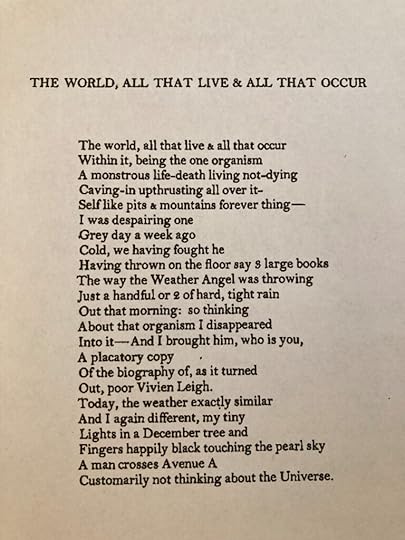

Between the World and the Universe, a Woman Is Thinking

Poem by Alice Notley, in the collection Grave of Light. Courtesy of Wesleyan University Press. Photograph by Sara Nicholson.

Poets have always known how inadequate language is. The speaker of this poem knows it well. No matter how hard she tries to capture the sublime or primordial essence of being, words fail her. Alice Notley herself has written about this in an essay, first published in 1998, called “The Poetics of Disobedience”: “I feel ambivalent about words, I know they don’t work, I know they aren’t it. I don’t in the least feel that everything is language.” Her poem “The World, All That Live & All That Occur” rubs up against the edge of the unsayable. Notice that it begins with “the world” and ends with “the Universe,” that its very structure points to the poem’s origin in and return to an infinite space beyond language. Paradoxically, impossibly, the poem is bounded by boundlessness.

The poem’s situation is simple. A woman is looking out a window on a rainy day in New York City, 1977. She remembers a fight from the week before. She watches a man cross the street. She is also contemplating the nature of being, what she calls “the one organism.” This is how she defines it: “A monstrous life-death living not-dying / Caving-in upthrusting all over it- / Self like pits & mountains forever thing.” She’s speaking fast. These lines have a powerful rhythmic velocity. As she struggles to articulate an ontology, the words get squished together into a hilarious pileup of modifiers. It’s funny, awkward. She knows her definition is inadequate, but it’s the best she’s got.

Between the world and the universe, a woman is thinking. Unlike the man in the street—and I think gender is important here, echoing back to the earlier “he”—she is thinking about it. At its heart, this poem describes a compressed moment in time, put into stark relief by her contemplation of the great organism of being. The moment contains a droplet of eternity; Avenue A is metonymic for “the Universe.” I hear an echo of William Blake’s infinite grain of sand, in which we see writ minutely a whole world.

The poem is full of contrasts. A wife and a husband. The thinking woman in the window, the unthinking man in the street. Men, who are bestial (they don’t think, and they throw stuff), versus women, who are philosophical. The “3 large books” parallel the “handful or 2 of hard, tight rain.” Books, which serve as both a symbol of their fight and their source of reconciliation. The organism, which is all contradiction: its “life-death” shoots up and plunges down at the same time. The word all in the title and first line, which functions as both a singular and plural noun. The word itself, broken into “it-” and “Self,” self and world. She describes the weather as gray when she’d been in despair, but today “happily” as pearl. The poem’s palette is all contrasting brights and darks. Tiny lights twinkling in a Christmas tree, her chiaroscuroed hand against a luminous sky.

I’ve always found this last image difficult to talk about. Maybe it’s the word touching, the fact that she tells us her fingers are literally touching the sky. She is merging with the organism, and the window has become a portal between her everyday life and a universal consciousness beyond. Or is it the odd word order—“fingers happily black touching” instead of “black fingers happily touching”—that so arrests me here. It takes my breath away. Something is happening at the poem’s atomic level. For Notley, poems enact a “vibratory setting-off” of language, a quantum field of movement, transformation, and condensed power. “It can’t be taught and can barely be discussed,” she writes. “It’s maybe like, instead of describing an object, making you hear its atoms spin.”

Notley is a difficult poet. First there’s the sheer volume of her work, nearly fifty books and chapbooks across six decades. Some of these are short, but others—Alma, or the Dead Women; Benediction; and The Speak Angel Series—are sprawling epics, hundreds of pages long each. Much of her work, especially post-2000, is not especially excerptible or anthologizable. She has discussed widely her interest in dreams, telepathy, trance states, and communication with the dead, from whom she takes dictation regularly. “I think most of my poems may be already written,” she says in her most recent book, Being Reflected Upon. These unwritten works are carved onto “a stele or slab” inside “a vast green ‘room’ / with no walls floor or edges” that she visits in dreams. She refuses to fall back on what others have said, to settle into a single mode or style—she is as suspicious of received ideas as Descartes—and the result is a furious integrity (“One must disobey everyone else in order to see at all,” she writes in “The Poetics of Disobedience”). Yet for all this, I find that many of her most difficult poems are short and unassuming, like this one. Inexhaustible. Poems whose atoms, magically, I can hear spin.

I love this poem because it is beautiful. But it’s also personal: I like reading about women thinking. Women like Isabel Archer and Anna Wulf, like the unnamed narrators of Ingeborg Bachmann’s Malina and Clarice Lispector’s Água Viva and Claire-Louise Bennett’s Checkout 19. I’m also a woman who likes to brood in windows. Where I live when I live in New York, there’s a window seat that looks out onto the entrance to a neighborhood park. It’s a powerful place to be anonymous. And as Notley’s speaker knows, it’s a good place to think. I like to think of her at the window of her then-apartment at 101 St. Mark’s Place, like a Weather Angel, perched from on high. She’s become a kind of goddess, dreaming the world into being. Dreams that, like so many great poems, are, according to Notley, “messy, embarrassing, truthful, sometimes clairvoyant.” Like this poem, “full of exquisite release.”

Sara Nicholson is the author of three books of poems, most recently April.

April 30, 2024

Alice Notley’s Prophecies

ALICE NOTLEY AT HOME WITH HER SON ANSELM, NEW YORK, 1984. PHOTOGRAPH BY SUSAN CATALDO, COURTESY OF ALICE NOTLEY.

In the new Spring issue of The Paris Review, we published an Art of Poetry interview with Alice Notley, conducted by Hannah Zeavin. To mark the occasion, we commissioned a series of short essays that analyze Notley’s works. We hope readers will enjoy discovering, or rediscovering, these lectures, essays, and poems.

I was not raised with any religion. We weren’t told that God was dead; having never existed, he’d had no opportunity to die. Instead, the material world had its own beauty, if occasionally cold or mathematical: the paradox of particle and wave, the litanies of astounding facts and figures (do you know how a snake sheds its skin?). It was a view of life ruled by information: sensible, finite, hard.

And so, when poets find the confidence to prophesy, I often doubt. If someone tells me in so many words that they are about to deliver me another Book of Luminous Things, as Miłosz memorably titled one anthology, my brow furrows, even if I remain curious. When I was in college, I was in a workshop with a poet who was writing their dissertation on “vatic” poetry of the twentieth century. After looking up the word, I always found it slightly amusing. How easily the mystic could be isolated, another device in the poet’s bag of tricks. Poets are used to the idea of other voices speaking through them (don’t get them started on the etymology of inspire), but an overreliance on a private line to a higher power can begin to feel cheap. There’s a reason Berryman called Rilke a jerk (though of course, pot, kettle).

But when I first read Alice Notley’s sprawling, twisting, hilarious, and deadly serious poem “The Prophet,” I regained a certain measure of belief. The poem, written in the late seventies, stretches across a dozen pages in long lines alternating with short, a little like Whitman’s exultations spilling over the margin. Who’s speaking? Hard to say—you feel the voice, but lines ricochet in different directions. Take the first two: “They say there is a dying star which is traveling in two directions. / Don’t brood over how you may have behaved last night.” Nearly opposite ideas—one cosmic, one personal—but somehow fusing. Then language rains down like brimstone. It seems to never stop, never waiting for you to “place” it—it’s the difference between a prophet in a white beard and white robes and another speaker who is at once more ordinary, more elusive, and more terrifying. Commands (“You must often luminously tell / The grossest joke you know to all those stiffs in the other room”), suggestions (“Perhaps you should / Call money ‘green zinnias’ ”), declarations (“Science has almost made it that you yourself hardly ever perceive / anything”), questions (“Why must your / Husband occasionally seem to think other women are more wonderful / than you?”), and observations (“When you / do the mistaking, / The taco-&-vodka man laughs wickedly”) intertwine and contradict, throwing up scenes and ideas and dismantling them just as fast. The poem is studded with New York scenes and TV-show flickers, but it’s also a mind voyaging through and beyond the quotidian, held together with confidence from a place you can’t observe.

And isn’t the prophetic something truly surprising, arriving from outside our impaired vision? Could we all have the ability to surprise if we were willing to loosen certain ideas about poetry that we think we require? Notley writes, “Don’t be afraid of your own mind, there’s an ocean there you know / how to swim in.” Surrendering to that potentially infinite flow brings inner and outer together, makes our ordinary coeval with that dying star. Luminous without the eye roll. “The Prophet” helps you to exist for a while in a place between meaning and not meaning—somewhere easy to get to, but maybe not so easy to stay in. It’s tempting to compare it to the oracle at Delphi, writhing through the fumes—I suppose she had a good time, too, and maybe a sense of humor in delivering all those reversible curses. As Notley’s poem says, either breaking down or going too fast for any consciousness (hard to tell): “You have remarkable power / Which you not using like sonofabitch.”

David Schurman Wallace is a writer living in New York.

April 29, 2024

On Being Warlike

IN FRONT OF SAINT VINCENT DE PAUL IN PARIS, 2005. PHOTOGRAPH BY ALEX DUPEUX, COURTESY OF ALICE NOTLEY.

In the new Spring issue of The Paris Review, we published an Art of Poetry interview with Alice Notley, conducted by Hannah Zeavin. To mark the occasion, we commissioned a series of short essays that analyze Notley’s works. We hope readers will enjoy discovering, or rediscovering, these lectures, essays, and poems.

This is another useless plaque for you all including the schoolchildren my brother may have accidentally mortared.

—Alice Notley, “The Iliad and Postmodern War”

We’ve long set aside the notion of “greatness” in literary studies because it smacks of (male) cultural hoarding, an analogue to the practices that allowed and allow some men on earth—be they emperors or billionaires—to extract the resources that would have otherwise sufficed whole populaces—see: the conquest of the Americas, with its genocidal and ecocidal sequelae; see: the forced mining of rare earths by endangered child workers in Congo so that ever-newer models of iPhones might succeed each other like a procession of pale and feeble heirs.

(As for me, a poet and mother writing this essay in the Rust Belt with one window open on the latest end of the world—a February day nearly thirty degrees warmer than the historical average—I don’t want to crouch in some bolt-hole like a prepper Scrooge McDuck on a tin-can pile of greatness. I can’t afford it. Then I read some billionaire is sending the world’s first cargo of junk to the moon by private rocket. Proof of junk concept.)

And yet, there is definite and definitive greatness to Alice Notley—a capacity, a surge, a stamina and a munificence; to me, her poetry, her poetic voice, unfurls a spangled aegis over the field of battle that is human existence over the past five decades on this planet. Long may it wave. Such an image, I’m aware, contradicts the anti-masculinist, anti-patriarchal, anti-militarist thrust of Notley’s poetry and her statements about her work. The truth is, this refulgent contradiction—Notley’s staunch anti-militarism versus what for lack of a better word might be called her “warlikeness”—her indefatigability, the relentless resourcefulness of her dismantling of the masculinist structures that support war, exploitation, destruction, and harm—might be the signature of her greatness itself, the reaction fueling its flight.

We can see this central contradiction at work in Notley’s talk “The Iliad and Postmodern War,” newly published in Telling the Truth as It Comes Up: Selected Talks and Essays 1991–2018 but written in the fall of 2002, amid the run-up to the 2003 invasion of Iraq. Notley reads the Iliad with the kind of exactitude of refusal that recalls to me a Greek goddess’s pinpoint rage at man and god’s casual violation of female precinct and prerogative—be it daughter, pet deer, city, or shrine. For Notley, the war-cult of her own moment and that of the Iliad are identical: “The Iliad is a sick book, the war against terrorism is our own sick poem.” She breaks with prose to pronounce a spell:

in the midst of all this

I say an internal ceremony

to kill my culture in me

as far back as I can

and including all of now as

it is currently understood.

This spell, for me, encapsulates Notley’s warlikeness. She wants to kill the war-addicted culture, a culture which is its “own sick poem.” Hers is a goddess-like impulse. But to me it is only warlike, because it is not, in the end, annihilative. Instead, its refusals and repulsions enact and require ceremonies that will themselves be the nascent impulses of new structures, new femme pluralities and possibilities.

To me, this lightbearing move, in which total refusal becomes paradoxically foundational, is Notley’s signature gesture, what she herself characterizes as Disobedience. Disobedience is an action of mind, ethics, and art borne out in her big book Disobedience, which follows a femme speaker and her would-be Virgil, a louche TV detective she calls Robert Mitcham, on a downbeat yet exhilarating journey through the City of Lights—an inversion of the subways of The Descent of Alette and a preliminary sortie, perhaps, into the fecund pluralities of the nocturnal Alma, or The Dead Women.

But for all the committed, exacting, marvelous forms this signature that Disobedience has allowed Notley to discover—now infernal, now urban, now Byzantine, now earthy, now desert, now cosmic—a critical quality is its inception into and proximity to war. In this sense the –like in warlikeness might indicate poetry’s tendency to similize; that is, to draw comparisons that double the conjectural space of poetry. Of course, this notion that writing could be double like this prompts Plato to view it with suspicion, as a pharmakon—both poison and cure—and, elsewhere, to ban poets from the Republic, on account that their “false” poems might reveal the weeping of shades of warriors in the afterlife, and thus reveal the painful truth about death, heroes, and war.

In doubling the imaginative space of poetry away from the pragmatic proscriptions of the militarized Republic and revealing true grief of war, Notley is disobedient to every one of Plato’s proscriptions. The choice is deliberate, and deliberately conveyed, in her brief talk on the writing of The Descent of Alette, “The ‘Feminine’ Epic,” delivered at SUNY Albany in 1995. There she describes the inception of Alette in the “state of extreme crisis” her brother underwent upon his return from the Vietnam War. Suffering from PTSD, he became addicted to drugs, entered rehab, and underwent therapy “to give some of the guilt back to the national community, where it belonged, but still died, accidentally OD’d a week after leaving that rehab.”

The pain and loss of her brother is the instantiating event in Notley’s career, in all its rage, generosity, and dazzling range. Discourse with, and/or proximity to, this ghost allows her to assume the alter ego Désamère and ventriloquize the delicate and formidable book of that name, and then to embark upon the explicitly katabatic Descent of Alette, the pointedly “feminine” epic. Notley puts on another alter ego—this time that of Alette—and goes into cosmic battle. In her talk, Notley discusses what she characterizes as the “feminine epic”:

Suddenly I, and more than myself, my sister-in-law and my mother, were being used, mangled, by the forces that produce epic, and we had no say in the matter, never had, and worse had no story ourselves. We hadn’t acted, we hadn’t gone to war. We certainly hadn’t been “at court” (in the regal sense), we weren’t involved in governmental power structures, didn’t have voices which participated in public political discussion. We got to suffer, but without a trajectory.

In this passage we can see the immediate pluralizing that will be key to Notley’s poetics, moving forward: “I, and more than myself.” The death of her brother, Albert, and the resulting pain and guilt, is the font of the anti-militarism, anti-patriarchy, and anti-masculinism that fuels five decades of her work, but from this warlike conceptus also grows an instinct toward plurality in its ethical, political, aesthetic, and choral potential—a “feminine” trajectory toward a starry firmament of voices, forms, and possibilities. As “The ‘Feminine’ Epic” concludes, “I’m writing currently as a unified, authorial ‘I’ who Must Speak. There may not be a story next time I write Epic, there may be something more circuitous than recognized Time and Story, more winding, double-back. There will certainly be a Voice.” This is an apt description of the larger and larger reach, the flexing, cosmic intimacy of Voice that has characterized Notley’s work since.

In “The Iliad and Postmodern War,” written some eight years after Alette, Notley provides an unexpected and striking figure for her work’s antiwar warlikeness: the Greek maiden Iphigenia, who in Euripides’s Iphigenia in Aulis is sacrificed by her father, Agamemnon, to appease the gods, raise a wind, and sail to Troy after Helen. Of Iphigenia, Notley remarks,

I don’t want to be that woman. Any part of whose existence is sacrificed to war. Whose brother is made into a killer by historical tradition. Whose country slaughters foreigners. Who must always appease a stupid deity, follow the dictates of a benighted even stupid male leader. And survive. And take it, take it, take it.

Yet Notley notes that Euripides also wrote a second play, Iphigenia among the Taurians, in which Iphigenia does not die. Instead, she is switched at the critical moment with a deer, which is sacrificed to Artemis in her place. She is spirited off to a remote island, Tauris, where a shrine to Artemis has been built after the goddess’s image, her likeness, has fallen from the sky. In this double play, then, doubles literally rain from the sky: a double (still wrathlike) Artemis, a double Iphigenia, a somehow always nocturnal double location, like a dream location—as Hypnos, the god of dreaming, is, in Greek myth, the twin to Thanatos, the god of death. Into dream’s double-region we may sail in our boats or fall with our images into night, into always more night. In Euripides’s second version, Iphigenia’s Furies-hunted brother, Orestes, oars ashore with a pal, and the two men are initially mistaken for Dioscuri, the double gods Castor and Pollux. He has PTSD-like panic attack on the beach, thinking the Furies are after him again. Eventually Iphigenia and her brother are able to recognize each other, are reunited and escape—into the night, into a deeper part of the dream, that death-alternative, that twin of Thanatos: Hypnos, dream, art.

Before all this happens, however, Iphigenia is granted a dream vision which she misinterprets—a long colonnade in which one column sprouts a rush of blond hair. While Notley doesn’t mention this passage in her talk, Iphigenia’s improbable and suggestive vision of an architectural structure blossoming with golden hair brings to mind the radiant, architectonic, urban, and prismatic forms that have structured Notley’s poetic texts for the past several decades, especially Wisdom and Other Women. It even anticipates that unexpected icon of Disobedience with which Notley closes her definitive 1999 essay, “The Poetics of Disobedience”—that of the ideal reader:

It’s possible that the reader, or maybe the ideal reader, is a very disobedient person, a head/church/city entity her/himself full of soaring icons and the words of all the living and all the dead, who sees and listens to it all and never lets on that there’s all this beautiful almost-undifferentiation inside, everything equal and almost undemarcated in the light of fundamental justice. And poker-faced puts up with the outer forms. As I do a lot of the time but not so much when I’m writing.

The ultimate figure of Disobedience, of alternative, gold-blossoming colonnades, unfurling a dream-space away from the masculinist militarism of the waking world, is the reader. Notley assigns to the reader her Disobedience while also distributing her infinitude, her stamina, her resourcefulness, her munificence, to the mind of the reader herself. Under the aegis of Disobedience, we oar away from war, by night, through dream, then into light.

Joyelle McSweeney’s tenth book, Death Styles, is now available from Nightboat Books.

April 26, 2024

On Elias Canetti’s Book Against Death

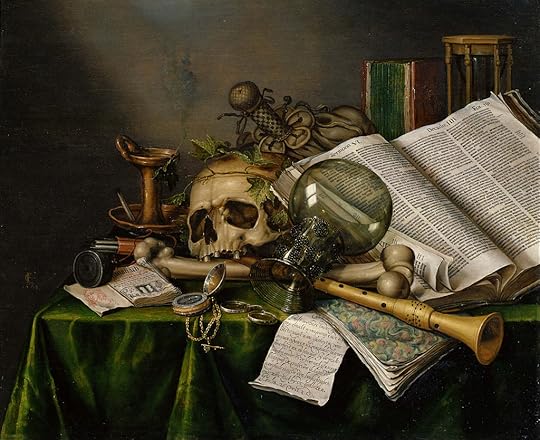

Evert Collier, Vanitas – Still Life with Books and Manuscripts and a Skull, 1663, oil on panel. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Read an excerpt from The Book Against Death on the Paris Review Daily here.