The Paris Review's Blog, page 28

June 21, 2024

“Intelligent, Attractive, Powerful Lesbians Conquering the World”

A letter from Marilyn Hacker to Joanna Russ.

The following correspondence between Joanna Russ and Marilyn Hacker is drawn from a new edition of Russ’s On Strike Against God (1980), edited by Alec Pollak, to be published by Feminist Press in July. You can read Pollak’s introduction to the work of Joanna Russ on the Daily here.

October 23, 1973

Dear Marilyn,

Your letter is lovely—esp. since now I can write two letters where formerly I would’ve written one: one to you, one to Chip.

Your book business is rather like my teaching, except teaching does leave more time & more ways one can cut corners, and so on. And you are beginning to sound just like Chip about London—I have this feeling that the two of you will turn up in NYC again—or I guess I should say the three of you.

And goodness knows, you BOTH need separate rooms. And the baby ought to have a velvet-lined cell where it can be put when both grown-ups have other things to do. Mind you, a nice cell, and a nest, too, but having seen your flat, I agree that it’s crowded.

God, it seems we all end up in the same place. A very close friend of mine, who used to get upset when I went on & on about MEN is now divorced; another came back from Canada more militant than I’ve ever been, and here you are saying just what we’re all thinking. I can’t read modern novels anymore (unless they’re by women), I can’t bear the conventional Didion sort of stuff, the usual Young Enraged Man simply seems to be writing from the other side of the moon or something. And I am worrying endlessly over the aesthetics of propaganda/polemic/didactic writing, trying to figure out (the worst problem currently) whom one is writing to. I think we both went through the business of I’m Not A Girl I’m A Genius, only they really won’t let one do that; it just won’t work. George Eliot is the most heartbreaking cop-out I’ve been able to find: every book I’ve read (tho’ I haven’t read Romola) breaks about halfway through. Her courage falters, her plot switches in midtrack like a locomotive suddenly on a switchback, and the scheme of the book crumples up. And it’s always where she comes to the conventional limits of femininity. Maggie changes into a different character in midbook in The Mill on the Floss (so does Tom, by the way)—Daniel Deronda is really two books—poor Gwendolen is left hanging in midair in the damnedest way while Daniel takes off for Zionism—and in Middlemarch, Dorothea’s first problem (what to do with herself ) somehow vanishes in the middle of a Love Affair. You can just see the book fall to pieces in each case. Only Adam Bede holds together—and there’s no stand-in for the author there. Brontë, seems to me, simply stuck to her own experience and let it dictate to her: she writes the Great Romance once (Jane Eyre, naturally the book everyone reads), lets her book split in two in Shirley, and breaks into the most bitter, passionate kind of subversion in Villette. Which is why, I am beginning to suspect, George Eliot (with her male worldview) is considered a Great Writer and Brontë isn’t. Or aren’t (both).

I don’t think it’s a matter of space but of fear. There’s Daniel’s mother in Deronda, the Jewish opera singer who hacked her way out of the ghetto and a ghastly father, even gave away her son so (1) she wouldn’t have to bother about him & didn’t want to and (2) so he wouldn’t be raised a Jew: it’s all there, the freedom, the ruthlessness, the price, the transcendent, necessary arrogance—and the author takes it all back by saying she isn’t LOVING. (!) Her life could be written, even in the nineteenth century, but Eliot didn’t. Brontë could have. I think Lucy Snowe is magnificent, tho’ I suspect some of the loose ends in the book might just come from Brontë’s early death. Was it published after her death? …

I’m happy with my teaching now, loathing my colleagues more than I can say (it wasn’t Cornell; it’s just the Type), and have just finished a thirty-eight-thousand-word novella in which my two Lesbian heroines end up practicing shooting a rifle in their backyard. I want to call it “On Strike Against God,” this being what some judge said in the nineteenth cent. to a group of striking women workers: that they were on strike not just against their employers but against God.

I would imagine you’d know by now—has Chip mentioned it to you?—that I’ve just about decided heterosexuality is, for me, the worst mistake I could make with the rest of my life. I was itching to tell you when I saw you in London but was too craven. And—not that I think you will immediately broadcast the news—do not tell anyone. I am not sure yet how I want to become publicly branded or by whom. And certainly if by chance any news of this should seep back to the academic community in which I live, that would most likely be IT.

The labeling still bothers me. I don’t feel like an anything sexually—and am quite capable of watching Christopher Lee on the Late Late Show (when I don’t have class the next day) and mooning about him all night. But I have more and more the feeling that my attraction towards men is compounded of a real witch’s brew of bad things—adoration, self-contempt, nostalgia, negativity—there’s something not-real about it, very imaginative and all that but still all in the head. While what I have felt for women has always been real, concrete, hooked to a concrete situation and person, and quite freeing. And very sexual. I keep trying to tell myself that the sex of the person I’m attracted to doesn’t matter, but that’s nonsense. It matters tremendously. Because all the power di!erentials, all the politics, all the pain & despair and God knows what of the past 34 years (by the age of two I was already being made into a sexist mess), simply can’t be wiped away. Maybe they could if the world around me did not constantly and endlessly reinforce them. (Which is a point I often tried to make to my analyst, without the slightest success.) I suspect you are right, and that we are all involved in very complex gender games, that people become hetero- or homosexual for very different, individual, and complicated reasons, and that men and women do so for extremely different reasons. But somehow all this has to be shoved into two labels. As a character says in that wonderful What the Butler Saw: “There are only two sexes, Preston, only two! This attempt at a merger will end in catastrophe.”

So I have fantasies (when I do) about men, but seldom. And none at all about women (except willful ones). And am not sleeping with anybody. And I keep losing the memory of my one rather pitiful and disastrous Lesbian affair, which was nonetheless magnificent, freeing, sensuous, beautiful, mind-bending, and real. I suppose the problem is that even with a Lesbian mind or soul or personality, I still walk around with a head full of heterosexual channeling. But it doesn’t seem to get below the head.

Of course there seems to be no way of making friends with any of the men here without getting my toes trampled on constantly. I try to turn a lot of it aside, or laugh at it, or ignore it, not wanting to fight a dozen battles a day, so eventually I explode and they are all amazed. I’m told I’m “oversensitive”—a quantified view of existence that has always puzzled me immensely! And alas there are so few people to talk to. And I’m tremendously gregarious at work. That is probably a writer’s problem: one can be either alone-and-working or gregarious, but switching takes time.

That may be why you’ve been so caught up in buying books—get into one head and you can’t get out into another.

My former lover and I are still very good friends, by the way. She has simply run shrieking from any sexual contact with anybody, apparently feeling so overwhelmable by people that she won’t sleep with anyone. And I do think feeling herself to be a (gasp, gulp) Lesbian did freak her out. But my goodness, I don’t feel any different.

Chip’s preface to Hogg impressed me a lot as you know, if you saw my letter to him—because of the connection it suggests—absolutely bedrock connection—between aesthetics and ethics. Aesthetics IS ethics, in another key, one might say. I find myself worrying endlessly over my novel and the new novella that somehow the structure isn’t right, isn’t tidy, isn’t “dramatic” or “good”—because indeed once you get outside the accepted values, everything changes, including one’s ideas of narrative. So the long, long short story (I think it’s really a short story in motion, if not in length) has no proper “ending”—it ends with a leap into the future, so to speak. Either one must leave that up in the air, as it were (Villette!), or end in defeat, which is a beautifully aesthetic ending, but hateful morally. Both the novel and the story end by, in a way, dumping themselves into the reader’s laps. And my OWN aesthetic sense, nurtured by unities and conclusiveness and dramatic resolutions which, in fact, are embodiments of accepted moral ideas, stirs uneasily and says, No, no, no. But (responds the other lobe of the brain) that’s what happened. How can one write about success in a situation in which success and the implications of it are still unrealized and fluid in actuality?

Suppose, for example, in The Left Hand of Darkness, Estraven hadn’t died? What a bloody moral mess Le Guin would have on her (I almost wrote “his”) hands! Here we have an alien hermaphrodite and a male human (who’s not quite real) in bed together. Worse still, living together. Could they live happily ever after? What would the real quality of their feeling for each other be? Could they get along? (Probably not.) Would they end up quarreling? (Their heat periods don’t match, let alone culture shock.) So the great old Western Tragic Love Story is called in to wipe out all the very human, very real questions, and we can luxuriate in passion without having to really explore the relationship. You see what I mean.

It just struck me that my 2 pieces, like Invisible Man, like Rubyfruit Jungle, like even Isabel and Sarah (which is cute but not that good) have no “endings”—the story ends either by saying; Here I Am—i.e. burning into you an image of the protagonist’s predicament (like Ellison and like my novel) OR by saying not “We succeed” but “We are now ready to attempt” or “We begin to attempt.” Which, studied by traditional criticism, is all very unimpressive, and “badly-structured.” Villette, it seems to me, ends with a Here I AM. You either end with “Now we actually begin” (or “It’s up to you, reader”) i.e. the rallying cry to the barricades—or we end with sheer lyricism, the power of one image, like the man in his room lined with electric light bulbs. One is a double-bind; the other is a promise or an appeal. And promises and appeals are certainly suited to propaganda. There have been lots of Unhappy Housewife novels in which (if she doesn’t go mad) the woman abruptly “solves” her predicament by denying it; I have 5 paperback books that do this, inc. Up the Sandbox, which is the worst. Also Diary of a Mad Housewife. They won’t make the leap. Polemics ought to end with a kind of prayer. I found myself writing at the end of my novel “Go, little book” etc. and last line “For on that day, we will be free.” (Schmalz, I tell you!) And in the novella, “I never challenged Daddy—til now.” But these are beginnings, not endings. So the aesthetic of polemic is going to be very very di!erent from the aesthetic of either comedy or tragedy. (Isn’t there something in German romantic writing that has this odd, “unfinished” quality? Because, in fact, it hasn’t yet happened? Shelley’s Prometheus ends with the lyrical faith-leap into The Image.) Oh tragedy is so beautiful. Jeez. Ugh. In my novella I said “You want a reconciliation scene? You write it.”

It really is aesthetically different. I suppose to poets it’s just as hard, but I envy you—you don’t have to produce PLOTS, you bastards.

Here I am, hung up on explaining to my friend here why I loathe and wish to destroy paternal middle-aged white men who tease me by flirting with me.

And a former Cornell colleague saying airily that Gilman et al. are silly people and why get angry at them?

Anyway, just came to me that in the novella, the process is as clear and plain as can be: (1) heroine has happy Lesbian love affair, after lots of initial worrying and reluctance (2) heroine “tries out” her feminism—integral to the affair and in fact what produced it—on 2 sets of friends (3) is repulsed by both (4) is radicalized (5) gets lover back (who has been going through same process) (6) prepares for Ultimate Revolution by learning to shoot rifle. Says her one wish is to “kill someone.” Not in hatred, but to make a change, a difference, a dent in the world. Could it be more dramatically/narratively put? Problem is that the ending is ethically the wrong sign—it shocked me as I wrote it. And what it will do to my colleagues if they ever read it is best left unimagined!

The pressure of the endings I didn’t write—the suicide, the reconciliation, the forgetting of the feminist issues (which I think far outweigh, or rather include, the Lesbian ones) kept trying to push me off my seat as I wrote. I kept saying to myself “That’s banal. That’s propaganda. That’s obvious.” (Oh how subtle failure can be!) But there was simply nothing else to do—anything else would have been false. In a vague way I remembered Frantz Fanon’s bit about having to shoot the oppressor just to make the tremendous discovery that The Man is vulnerable. But it was pure Russ, I assure you.

The aesthetic problem, as I see it, is that the “prepare to succeed” is itself tentative and complex—it’s not like an already settled issue, i.e. the Knights of Malta marching off to the Crusades. The real uncertainty of real issues comes in.

Goddess knows, it’s also the only kind of live literature now. All the old solutions have turned to fuzz & lint, as far as I am concerned. For women it was always (1) failure (2) the love affair which settles everything. Look at George Eliot, WANTONLY drowning Maggie so she can rehabilitate her. Oh, it kills me. This, from a talent as good as (or even better than) Tolstoy! Wuthering Heights gives us both the old tragedy and the new tentative hope-of-success—which is why, of course, all movie adaptations leave out Part II and no critic up until College English 1970 has spent any time at all on Cathy #2 and Hareton Earnshaw, except to say that the novel “declines.”

I am getting so that the very name “tragedy” or phrases like “the beauty of tragedy” make me grind my teeth. What excuses! Ah, one learns from suffering. Go tell it to Ralph Ellison.

And the happy ending of The Exception.

Still, it’s good to be writing now (if not living). All these beautiful pathetic heroines drowning & dying & getting poisoned or going interestingly mad. And all these heroes dying nobly, feh. Feh, feh, feh.

I must stop now—I haven’t yet got my rugs and my downstairs neighbors (who get up at 6 a.m.) come hallooing up the stairs if I type past 11. This spring I shall try to get a house.

Tell Chip that my new novella ends where he thought Female Man should end. (Actually I was getting there at the end of Chaos, when I had someone say “Just life” i.e. not a settlement or solution, just things going along.) Oof! If you have time, tell me what kind of poetry you’ve been thinking of. The whole business of propaganda is utterly fascinating to me.

It is the only live stuff.

Joanna

September 28, 1975

Dear Joanna,

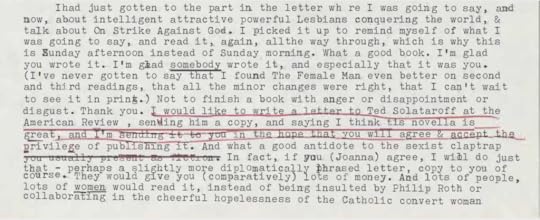

… I had just gotten to the part in the letter where I was going to say, and now, about intelligent attractive powerful Lesbians conquering the world, & talk about On Strike Against God. I picked it up to remind myself of what I was going to say, and read it, again, all the way through, which is why this is Sunday afternoon instead of Sunday morning. What a good book. I’m glad you wrote it. I’m glad somebody wrote it, and especially that it was you. (I’ve never gotten to say that I found The Female Man even better on second and third readings, that all the minor changes were right, that I can’t wait to see it in print.) Not to finish a book with anger or disappointment or disgust. Thank you. I would like to write a letter to Ted Solotaroff at The American Review, sending him a copy, and saying I think this novella is great, and I’m sending it to you in the hope that you will agree & accept the privilege of publishing it. And what a good antidote to the sexist claptrap you usually present as fiction. In fact, if you (Joanna) agree, I will do just that—perhaps a slightly more diplomatically phrased letter, copy to you of course. They would give you (comparatively) lots of money. And lots of people, lots of women would read it, instead of being insulted by Philip Roth or collaborating in the cheerful hopelessness of the Catholic convert woman short-story writer with eight children and a sexy but unsympathetic husband. (but Nature is beautiful, isn’t it?)

May I indulge in a few very small bits of lit-crit? I will.

Until the party scene, I was confused about Jean’s age & status (job). On second reading, I noticed that she is said to be considerably younger than her friends, who are later said to be in their mid-thirties. But on first reading I assumed she & Esther were coevals until the party, when I found out she was 25. Somehow things would have clarified themselves much more quickly (in terms of visualizing the characters &c) if she was said fairly early to be a 25-year-old graduate student (because I kept picturing her to myself as 35, profession to be revealed, simply, I guess because one assumes that people described first as my friend X are the same age as the speaker. The narrator’s past experiences given in the first pages place her in her thirties pretty definitely.

I’m probably not entitled to say this, but Stevie’s reaction, though perfectly believable seemed to me pretty atypical of what the average gay male reaction would be (Relieved? Congratulatory?) Which is not to exonerate gay males of sexism, or to want the episode changed.

Very minor point—when Esther goes back home, & describes having been attracted to a girl she saw walking in front of the library, this girl seems to be wearing the same outfit, or at least the same top, as Leslie was at Ellen & Hugh’s, though it isn’t said to be the same or similar. And it just made me stop a moment. I mean, if it was the same blouse, Esther would have noticed it. And if it wasn’t, its description made it seem so.

And last. The last pages are good, well-written, occasionally brilliant, threatening, strong, &c. But why are they addressed to men? I wanted this one to be for us, women. I can see the problem, that the book must end on a note of challenge, and you’re not looking to go out & shoot women, but there is still the implication that The Man is still so important that even this book, even in defiance, in hatred, in challenge, is addressed to him, that the person you see reading it is not a woman or a girl thinking here is something at last, but a man being Affronted.

Chip & Whi”es came back. Chip out again to see if an ambulance comes for a man who had a heart attack or epileptic fit in the park next door. Whiff is sitting on the floor at my feet, tearing a telephone book in half. Page by page, admittedly, but she’ll work her way up to more impressive feats. Trying to crawl these days, and obsessed by the problem. Betting (straight light brown) hair.

Will close now and post this.

Love, Marilyn

And what you were not saying two summers ago.

Like “The political is the personal!” Propaganda is an appeal to the future.

which is always a double bind, a no-win situation.

Joanna Russ (1937–2011) was a Hugo and Nebula Award–winning author of feminist science fiction, fantasy, and literary criticism. She is best known for her novel The Female Man and now for her darkly funny survey of literary sexism, How to Suppress Women’s Writing.

Marilyn Hacker is an award-winning poet, translator, editor, and lesbian activist. She is the author of nineteen volumes of poems, and her honors include the National Book Award, the Lambda Literary Award, the PEN Award for Poetry in Translation, the Robert Fagles Translation Prize, and the PEN/Voelcker Award for Poetry.

June 20, 2024

RIP Billymark’s

Photograph by Nikita Biswal.

Billymark’s West was a normal bar. That was its greatest virtue, probably. It had a pool table, a jukebox, booths, a beer-and-shot special. It was a little dingy and dark. There was a TV and, somewhat oddly, a lot of Beatles-themed memorabilia. The prices were not so bad, by New York standards, though drinks weren’t as cheap as they could have been, either. There was graffiti in the bathroom. It was in some ways the Platonic ideal of a bar, such that it might seem familiar to you even if you’d never been. It had its own story, of course: it opened in 1956 and was taken over in 1999 by two brothers, Billy and Mark, one of whom was usually at the bar. They were the kind of guys you would describe as “characters” in part because they were playing a well-worn role. Billy—whom I saw more often—would call me “honey” and then charge me a price for my Miller High Life that seemed, each time, to be made up on the spot. Sometimes he was gruff, but mostly he was jovial, and it appeared as though he knew everyone in the bar, in a vague sort of way. The patrons of Billymark’s filtered in from the odd mix of places nearby: Rangers games at Madison Square Garden, galleries in West Chelsea, trains at Penn Station, and the offices of The Paris Review a few blocks away. I liked going to Billymark’s for a drink after work, though I didn’t go all that often. Still, it was always a place to go, a place in the neighborhood that stood out mostly for how normal it was. When I found out the bar had closed a few weeks ago, I was bereft.

I understand that there are many people who are not always asking themselves, How can I get it back? But I am. Sometimes in fact this question feels like the animating force behind my emotional life—where did it go and how can I retrieve it? No one knows what it is, least of all me. Not long ago I was taking a train north toward Poughkeepsie and I was overcome with the memory of a previous train ride, on a Friday in July several years ago, toward a house in the woods where we stood one night on the porch and watched heat lightning and fireflies rise off the grass in the steam of a recent rain. Other more and less important things happened that weekend, but that is the image that came to me as I stared out the train window, along with the feeling that I could never get it back, any of it. I am speaking of what is generally called nostalgia, though I think the word is overused such that it conjures the gentle, moony feeling you might get listening to a second-rate James Taylor song. No, the feeling I am trying to describe is totalizing, characterized by sharp, surprising loss wrapped up with something like pleasure. That day on the train, I was so overwhelmed that I had to lie down.

Bars are good places to go if you want to chase feelings like this. Or bad places, depending on your perspective. But it’s true that people who frequent bars—who really frequent them—are often the kinds of people who are looking for something lost, and perhaps getting lost in that looking. This is related to the consumption of alcohol, which can feel at times like a shortcut to bygone days. It also has to do with the spaces themselves, which are designed to be familiar and to mimic, perhaps, other bars where we’ve been before while retaining their own particular magic. That’s what a good bar is like, anyway. There are fewer and fewer good bars, for all the obvious reasons, and Billymark’s was one of the last in the stretch of blocks around our office. I can’t really explain why, but it was an especially good one.

Billymark’s was the kind of bar that allowed you to feel like maybe you could get it back. It made me think I could get Beacon Hill Pub back—the first bar where I ever drank as a teenager, a place where in the eighties my father used to eat the hot dogs they would boil at closing time, or so he said, and where I once whiled away a Saint Patrick’s Day staring into the shockingly blue eyes of a stranger, wondering what would become of my life. That bar is closed. Billymark’s made me feel like I could get back the Chieftain, an old newspaper bar downtown in San Francisco which isn’t even gone but is gone from my life, or really I am gone from its. Other bars like these, where I have wasted my wastrel youth, all seemed contained, somehow, in Billymark’s. They seem contained, too, in the loss of it. Probably I should have expected this, from all those stories I used to hear about bygone days, but it’s been a surprise all the same: as I get older, there are more and more places I’ll never go again.

One time I went to Billymark’s to meet my friend Nick. I was going somewhere later, but I was also sad about something. He works in the neighborhood too. We decided to have a quick one. We had a Miller High Life and a shot, and then a second Miller High Life and a shot, and we talked for what felt like a long time. Then I walked out toward the subway smiling, into the damp of a February that like every February seemed like it would never end. Nick and I have gotten a lot of quick ones at a lot of bars, but they seem contained in that evening, the image I have of parting ways outside of Billymark’s into a new glow we had constructed through the sometimes-dark magic of that bar. I can’t remember what we said to each other now, nor can I now return to the booths where we said it, and so I find myself wondering once again: How can I get it back?

Sophie Haigney is the web editor of The Paris Review.

June 18, 2024

Announcing Our Summer Issue

As we were putting together this Summer issue of the Review, an editor in London sent me Saskia Vogel’s new translation of a 1989 book by Peter Cornell, a Swedish historian and art critic. The Ways of Paradise is presented as notes to a scholarly manuscript; the author, Cornell tells us in an introduction, was “a familiar figure at the National Library of Sweden,” where for more than three decades he was “occupied with an uncommonly comprehensive project, a work that—as he once disclosed in confidence—would reveal a chain of connections until then overlooked.” After his death, the manuscript was never found. “Which is to say,” Cornell writes, “all that remains of his great work is its critical apparatus.”

The footnotes that comprise The Ways of Paradise orbit certain preoccupations: the center of the world, labyrinths, flânerie, rock formations, Freudian repression, passwords, folds of fabric, aimlessness. As I followed the trails left behind by the mysterious man Cornell calls the author, I felt an emerging sense of relation between only tangentially related things. (I also felt a relief that the categories of “Fiction” and “Nonfiction” had already been banished from the Review’s table of contents in favor of the more-encompassing “Prose.”)

Taking note of connections, intended or not, is one of the pleasures of deep, patient reading—which is to say, one of the pleasures of reading for pleasure. And so I am always delighted when, despite our best efforts to avoid organizing an issue of the Review around a given idea or theme, a reader will point out that the most recent one was clearly all about this subject or was wrestling with that idea.

Which makes the kind of letter I am now writing—to announce our new Summer issue, out this week—a conundrum. I could flag its seasonal topicality (“That summer we had decided we were past caring,” Anne Serre writes in the issue’s first story. “It was just too tiring, rushing back and forth between mental institutions”). Or I could, like a savvy host at a drinks party, point out possible conversation starters: works in translation, maybe. Or romance novels (“I am a sucker for women carrying each other around,” Renee Gladman writes in “My Lesbian Novel”). Or the visionary (“It could be a dog crossing the street one morning with a string of wieners, which is something I’ve always wanted to see,” Mary Robison tells Rebecca Bengal in her Art of Fiction interview. “That’s my golden dream”).

But most of the time when we read, we are enjoying something we can’t necessarily name in advance. In Dreaming by the Book (1999), Elaine Scarry argues that when writers describe something, what they’re really doing is instructing the reader in how to make mental images—ones that appear “not just like a lazy daydream,” Scarry explains to Margaret Ross in her Art of Nonfiction interview, “but as an incredibly complex landscape of interactions.” There is no replacement for this powerful exercise, she says: “If you really want to take down someone’s, or a whole population’s, ability to think, you must do it by shutting down their practice of the fictional as well as their practice of the factual.”

Consider this issue of the Review, then, a chain of connections whose links are you, their reader. Soldiers, reportedly killed in combat, disembarking from a train in the eerie light of dawn, in a story by the late Argentine author Rodolfo Enrique Fogwill, translated by Will Vanderhyden. Odysseus sitting on the rocks by the edge of the sea, grieving his homecoming, in Daniel Mendelsohn’s new translation of The Odyssey. Scarry recalling how, as a child on summer vacation, each day she would await her grandfather’s return from the anthracite mines where he worked. “I would trace his path in the dirt over and over,” she says. “I’d think, Now he’s coming out of the mines, now he’s approaching me, when I look up he’s going to be there. No, he’s not there. He’s coming out of the mines, he’s approaching me. No, he’s not there.”

Emily Stokes is the editor of The Paris Review.

June 17, 2024

Rented Horrors

Illustration by Na Kim.

I was a fairly unsupervised child, living like a rat on the crumbs of adult culture, its cinema in particular. 1976’s Taxi Driver I saw for the first time at eight—rented and shown to me by a housemate of my mother’s—and what I remember most is the gamine Jodie Foster at a diner’s laminate tabletop: her cheer, and her will, her fistfuls of prostitution money. The relieving and misguided lesson I absorbed, likely because I felt particularly attuned and exposed to adult violence, was that childhood could be short-circuited. Soon after, thanks to a few errant adults in my life, I was renting the most obscene things I could find, studying the horror aisle of the Silver Screen Video in Petaluma as though it were the Library of Alexandria: containing and promising and threatening all. Unusual to my experience of these films was that their one-dimensional and sex-warped predators did not seem so different from the world reflected in my actual life.

A few years before, the month I turned five, my neighborhood had been infested by the FBI, who were searching for traces of the just-kidnapped twelve-year-old Polly Klaas. She was abducted in October of 1993 from a sleepover at her house, which was around my literal corner. What Polly became, in the child’s simplistic understanding, was the greatest celebrity: her face on every magazine and national news segment, the vigil always lit for her in town looking like an ancient shrine to the cruelest gods. It took almost two months to find her body. When the guilty man was finally tried, he famously declared in court that Polly had pleaded: Just don’t do me like my dad. Her ruined father lunged for him.

In the years I consumed most of the horror canon, I saw Sissy Spacek in her red shower, Tatum O’Neal with her hips electrocuted by sin up toward God, Jamie Lee Curtis in breast-bouncing flight. I watched the Pet Sematary trilogy, though the supernatural was never of much appeal—I was a girl, and I was curious about girls being killed. One could say that this curiosity was only an expression of internalized misogyny, and one might be very right, but this theory would exclude the great protection afforded me by the chance to experience this kind of hatred against women with no disguises, in private, with the ability to rewind and replay.

Decades later, I’d read the white feminists who castigated the slasher canon, Solnit and her derivatives who called for its expulsion, asking why it was that depictions of violent misogyny, the fetishization of the missing woman and the female carcass, had not been dismissed from the cultural record. By then it was too late to revise my response to genre’s blunt messaging, which had been a comfort when I was a girl, requiring even for the child little decoding. That bluntness was welcome among the subtleties of other monoculture staples: how a likeable male character on The Larry Sanders Show might meet jokey opprobrium for being “pussy-whipped,” or how, as in the dispiriting pablum of You’ve Got Mail (1997), a charming woman could find real love so long as she sacrifice her financial and spiritual purposes. The horror movie was also the beginning of my indoctrination into image culture, the fascination with the unidirectional, the film still or painting that could change me—and that I could never change. It did not occur to me until recently that this submissive solace came at certain personal costs. Back then these movies felt like an empowerment, because what I hoped to comprehend, in order to master, was the machinery of fear.

Something horror movies have always understood is how fear is a granular phenomenon, one whose most powerful vehicle is not the antagonist, but the onus he creates in the consciousness of the pursued: the woman whose survival depends on her never becoming paralyzed with terror, but also never relinquishing it entirely. After Polly’s kidnapping, after Polly’s murder, none of the children in our neighborhood could be seen outside locked houses. All the jewels of small-town Americana that had brought the families there became doubled with evil—the lacy eaves of the Queen Anne Victorians rendered gothic, the branches of huge oaks splitting the sidewalk at forty-five-degree angles violent. I’d always eaten the wild berries that grew through so many fences, dripping coastal dew on foggy mornings, but I remember, after that girl’s death, some neighbor slapping my hand away, certain that glistening black cluster was poisonous. For years after, school meant frequent assemblies. Fluorescent take-home packets, exhorting that we memorize certain phone numbers and signals of danger, were countless, and in a prefiguring of the brave or heedless woman I’d become, I left them crippled in the juice-damp bottoms of my backpack. Each child’s life, the language seemed to suggest, was now the child’s responsibility: there were numinous lurking forces that would always want to end it.

In 1995, a town over from where we lived, the first Scream movie was shooting—they had approached the high school there, but a rabid city council meeting that cited the Klaas case obstructed the possibility; the production found a nearby community center to pass as a school instead. Once it was in theaters, the adolescent older brothers and sisters of my friends seemed proud to point out the locations—in particular the stately houses, dressed by the scale of velvety hills and long, curving driveways—where Drew Barrymore and Neve Campbell had tried not to die. Our town was diseased with film shoots before and during my childhood: American Graffiti (1973), When Peggy Sue Got Married (1986), the remake of Lolita (1997), Pleasantville (1998), Basic Instinct (1993), not to mention a cameo in Reagan’s “It’s morning again in America” 1984 campaign agitprop; if you crossed the town line you could soon reach the church from The Birds (1963) and the beach from The Goonies (1985).

But our inclusion in the slasher renaissance of the nineties—portions of I Know What You Did Last Summer (1997) shot nearby soon after Scream—fed a unique carbonation of local spirit, maybe because of another precept of the genre: that the greatest evil comes for the greatest safety, or purity, traits long conflated in Hollywood with affluence and white beauty. When Polly died, much was made of how close-knit and idyllic the town had seemed before, of how newly these Caucasian mothers feared for their children. This seems to me now a cryptic confirmation of another great evil: the assertion that these lives were worth more than those already endangered by more systemic threats. Polly’s murder became a flashpoint in the legislation of California’s three-strikes law, for which her father platformed, and which incarcerated even categorically nonviolent multiple offenders, the majority of them people of color, for life.

Perhaps the area’s self-mythologized virtue was why parochial beauty seemed the right setting for Scream’s dead teenager in a miniskirt, electrocuted and hanged through a pet flap in the raised garage door. The girl’s mistake, in that scene, is to mock her killer, who has confronted her with a knife, for playing his role. “Please don’t kill me,” she sneers, “I wanna be in the sequel.” A then-novel feature of Scream was its cringey meta-awareness of the genre, delivered by an incel-ish teenage video-store-clerk character who reverentially expounds upon horror’s narrative strictures—for instance that anyone who has sex, or uses the phrase “I’ll be right back,” is sure to be slaughtered. That teenage girl’s death by electrocution and asphyxiation is the first in the film that is not a stabbing, suggesting mightier retribution to those who mock the archetype. In other words, she dies for not believing movies are real.

***

It was around the time Scream was shooting that my mother—an unusually tall, beautiful, and errant woman who still dressed in the dramatic capes and trench coats she had worn on the dark boulevards of cities where she’d lived before—was the prey. She was unlike many of the mothers I knew: single, poor, a smoker, a renter, free if not lascivious with nudity, a Wiccan, then a Buddhist. It began with a few occurrences I later heard her narrate to the police: one night, she had thought she’d closed the front door, but the front door had been open, beyond it my rope swing arcing through a windless night. On a phone bill she discovered many calls to paid phone sex lines, backdated to weeks before the event in question, which was this: around 3 A.M. one night, she woke up to discover her blankets had been removed. At the foot of the bed a man sat crouched, stroking her feet. As the story went, she chased him shouting out of the house through the back door, and he was a spectacular runner, leaping corner bushes, sending the wooden bench of the swing to flight again.

As later became true of my life, my mother had many friends, but no family. She had a surfeit of love but a scarcity of protection, which mirrored what she offered me. In sum, I was often alone. I can see my childhood much more than I can feel it—in fact, when urged to by professionals, I struggle to feel it at all—so the banalities of how I spent my time, and the specifics of the culture I sought out, are of talismanic interest to me. I know I walked much more than was popular for children to do, that there were often community Bettys and Rachels leaning out car windows at intersections, offering and then insisting on rides I always declined. Though among classmates I was affable and socially invested, I was fond of certain back passages: the narrow cobblestone alleys downtown, or the canopies of bramble that could be found at the borders of my elementary school, reached at recess by a bend in the chain-link fence. I liked to see without being seen. Perhaps I was imitating the safety and authority granted the observer or the stalker, but because in my hiding I never wished to hurt anyone—let alone be anyone—it feels more precise to say that I wanted to be a camera: to become its cool black glass, maybe something even further ungendered and bodiless. Ratified by privacy, I felt like the sight line itself, narrowing and focusing as the narrative demanded.

My fixation on a particular film, When A Stranger Calls Back (1993), was occasioned by the fact that I had a VHS copy—taped from TV and given to me by teenage neighbors—but its camp dealings with stalking and home invasion held lasting and relevant appeal. What I remember most is an audacious scene in which the protagonist, believing all her doors and windows have been secured, all closets verified empty, takes a moment to recalibrate in her spartan loft. As she passes out of frame, the camera settles on the exposed brick wall and reveals the architecture is breathing: the stalker has disguised himself, in elaborate ocher-and-charcoal makeup, to blend in with the bricks and divots. The eyes in the wall open and scan left and right, with joy and interest, seeing everything they need to without moving at all, as it goes tackily mythologized that the great director does. Fixed in his chair when the shot is finally right, all arrangements he takes in are his, all starts and struggles and ends, all limits. If I had likely focused on this film because of the man who had targeted my mother, later it came to echo an event in my own life: when I was a freshman in college, placed in a cinder block dorm of breezeways and little security, I woke a little before dawn to a figure in shadow at the foot of my bed. Nothing moved but his hand.

The strange thing about the memory is how little I recall, what I did or said to make the man flee. I know only that my roommate, whom he passed on his way out, screamed and ran to my side of the room. I don’t remember any real trauma afterward, any real trouble sleeping, and this must be because it did not seem remarkable—given the absolute resemblance to what had happened to my mother, and given the filmic images I had put in my mind, so much worse than this pathetic masturbating stranger. I learned later, from campus security, that the girl who’d slept on my mattress the year before had once woken to a man of the same description. He had stalked her all year, they said, and the tone with which they delivered this information suggested it should be cause for relief, or akin to it. But the air of the fact was also the faint breeze of dismissal. “You would never be kidnapped,” I remember the exquisite bully of my Girl Scout troop saying, on a camping trip in the Polly years, to a gangly, weak-chinned child among us. She well grasped the insult and wept, cloistered and gasping for an hour in her sleeping bag.

Why wasn’t my door locked? Perhaps few bothered in that sunny suburban dorm, perhaps it had been my roommate’s oversight, but I wouldn’t bet on either—namely because I had modeled myself after my mother, who, after all that had happened in the neighborhood, was foolish or fearless, had always left a window cracked for the cat. I remember her insistence on this detail, but I don’t know if she saw it as absolution or apology, to herself or to me. Sometimes grief imitates the dead it misses, but I think I’d shown myself stubborn long before she died, recalcitrant against precautions I wouldn’t have to take if my body were otherwise. Even after I was without the mother who would ask after my location, and likely in perverse service of that mourning, I went on walking through urban parks at night when it was the straightest path home, accepting the drink or the drug in good faith. I spent seasons alone, usually quite happily, in extraordinarily isolated places—where I did not know a person, where I did not hear my name.

There was another story about my mother and male predation, which is also another story about a brick wall. In the desolate Bronx of the seventies, she had slammed the skull of a man who tried to mug her against the nearby building once, ending the interaction. It is less relevant because of the act, and more because it was her still-awestruck male friend who delivered the information. She hid her eyes with a hand and giggled, hesitant to accept this as an achievement. I wish I’d understood the wisdom she subtly modeled then, which contravened the lessons of the horror genre. Any defense against violence was mostly an accident of norepinephrine and circumstance, saying little about the woman you were at all other moments, and had decided, through your life’s obligations to yourself and other people, to be. Your identity was staked to so much not relative to male predation, the bashful, witty kiss she gave me said, even men in general.

But at eighteen, woken by that man and unafraid, I only saw myself as lucky, if luck can be tenebrous—to have spent my childhood numbed by the real hatred in all that fake blood, which scanned more as a total transformation of the body rather than a consequence of any distinct, mortal wound.

***

Strangely, all that blood comes from a black-and-white imprimatur. In the trope of the stabbing hand that Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960) invented and all the slashers later adapted, the camera remains on Perkins’s flexed wrist, where it pumps with the mechanized regularity of an oil rig. In 1960 this was a concession to ratings: they could not show the slain Janet Leigh or much of her struggle, save that brief snatch into her eye. But in the desensitized decades that followed—the genre birthing itself in full color, those makeup artists surely keeping this in mind—the formula usually concluded to picture its victim only once all hope was lost, an often naked body slathered in pools of primary red. Consider the sound that accompanies Perkins’s grip, the top of the violins that composer Bernard Hermann keeps muted until the murder, in a score he symbolically called “monochromatic.” When Americans jokily mock this gesture, they tend to sync their shrieking with the mimed stabbing, suggesting that the sound represents the glint and motion of the knife. But I’ve always heard it as a thrum, like a biblical horde of mosquitoes, coming not for a trickle of blood but for some endless offering of it: more a spectacle of color than the female death it depicts. “Not blood,” Godard famously spat, when asked about the excess of it in 1965’s Pierrot le Fou. “Red.”

As a child horror fanatic, did I ever consider I might have felt drawn to all that female blood because other depictions of it were lacking? The last few years have seen a spike in menstruation imagery—usually sexualized, fetishistic, and foreboding—but it was not until my early thirties that I read any fiction not deploying it as a furtive upset or a burden, or in the context of heterosexual pregnancy. The phenomenon seems hardly to have changed in meaning, even for the Girlboss-y, Future-Is-Female, post-Wing cis millennials, from a symbol of shame, or at best inconvenience, to anything like power, or fertility. I’ve heard female friends say you ought to fear the men who beg to fuck you as much the repulsed who refuse to. If I don’t know what to believe on that count, I do feel certain about the horror genre’s relation to blood. It is no coincidence that the cinematic slaying of choice, even in a country with a gun problem, has always been a stabbing—phallocentric and protracted, leaving its victim a certain amount of time alone to die: alone with the body that has, apparently just by living, provoked its own gushing end.

***

The horror movie was the gateway to cinephilia for many—proliferating faster than any other genre in the history of Hollywood, targeting the same adolescent market who were the invention and target of twentieth-century advertising, raising two if not three generations on the sport of classifying similar entries against each other. I mostly stopped watching anything capital-H horror by my early twenties, though I kept up with what it influenced, and my feeling for the genre was replaced by a religious feeling for cinema itself, in a theater whenever possible, a ritual I still most love to experience alone. Because of how the horror movie trades on captivity and voyeurism, it is easy to argue for the genre as not only the entry to cinema, but a broader metaphor for the cinephile as a type.

Cinephilia as a condition was most classically deconstructed in the theorist Laura Mulvey’s “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema,” but if I read it now the argument neatly doubles as a reading of horror movies, as well as of their male fanatics, and where these films leave the women who also watch them. Describing the hedonism of the person in the dark theater, hermetically sealed from the morals of the world outside, Mulvey suggests this experience is both of “looking in on a private world”—like the horror film’s stalker or murderer does—and “blatantly one of repression…of [the viewer’s] exhibitionism and projection of the repressed desire onto the performer.” The person in the audience, Mulvey says, undergoes a graded process of identification with the image before him, just as the Lacanian child comes to recognize his reflection in the mirror. If I read this as applied to the horror villain, the boiling point of that repression is the moment of transgression: the projections acted upon, the phone line cut, the knife unleashed. The murderer, watching his prey, is a stand-in for the moviegoer watching the villain; it’s a perfect circle, one that leaves real women out. That the history of cinema is overwhelmingly male is no secret, but that its pleasures are particularly suited to the female captor in the audience—and that these pleasures deepen and complicate when the film depicts violent misogyny—may be less discussed. If you return to Mulvey’s original thought about projection but keep the horror movie in mind, something else becomes quite obvious: the moment that the male audience finally identifies with the image of the villain is also the point at which the real woman in the dark is finally, if temporarily, inviolate. She is alone with an entrapment that she has—unlike many other confinements in her life—chosen, and paid for.

When I was much younger, before seeing movies with men became a staple of my social life, my inclination after leaving a theater was to stay quiet, extend the hush of that entrapment. But by my mid-twenties I had populated my life with a number of film directors and editors and critics, men of a familiar pathology whom possibly I objectified: all of them I relied on to think rather than feel, to contextualize and classify a single film as a phenotype within an archetype. I was at first an amateur in this indexing, my encyclopedia less reliably recalled, and then I began to study: staples and arcana, four-hour screenings alone, Jarman and Akerman and the nurse exploitation boom of the seventies. The bickering geriatrics at Film Forum, the damp and bald eccentrics at Anthology. I’d never be a golden-key cinephile—I had another purpose, which was to write my own fiction—but I was hardly ever more joyful than the moment a screening started. It felt like love, or was better than love, how now I’d been found, and now I might change, without the burden of having to speak, or even to stand. The periods in my life when I saw the most movies were usually characterized by some furtive emotional dimension I did not feel equal to observing. There were friends I wouldn’t see because of what personal question they might ask, but I would always see a movie.

Seeing movies, in the way I saw them and with whom, also meant a certain degree of being seen. When sometimes one of these men, or their friends, remarked that I looked like Léa Seydoux or Michelle Pfeiffer or Glenda Jackson or Mariel Hemingway—a kaleidoscope of features different enough that I had to wonder if my beauty was even real, if my face was even fixed, or if either were mine—I tried not to think whether that was chief reason for the friendship, not the intellect I’d cultivated. A strange thing about female beauty is how, even if it changes and can act on your life—and I do feel ignoble to say that I have allowed it to hugely or ruinously act upon mine—you are never meant to admit to it. Perhaps, in the half life of the movies we’d just watched, it was easy for these directors to imagine: my crying at their cue, or awaiting permission to move my arms and legs from some splayed false death. The broken ankle of my feminism had always been an ease with female tokenism, and my appearance’s part in that tokenism I both begrudged and vainly, hideously, misogynistically accepted. Of course I glorified filmic beauty, of course I was flattered. And this was despite and because of the fact that in the horror movies I had chosen to parent me, this was the quality that typically invited targeted slaughter—the ultimate act of attention—and before that, status as a protagonist, at least as a main character. So many movie stars—texted a cinematographer I was once decided I was in love with, happy taking direction because of how instantly he declared he was in love with me—make me think of you. Soon after, about my upcoming period, from a set in another country: I can’t imagine the blood you must pour. I can remember rereading that text, in thin disgust or morbid fascination, and I can believe now, even if he might dismiss the thought, that the statements were not unrelated.

I came, in time, to feel afraid of him, that man, or of the illogical fact that I’d mistaken my long and real admiration for his work—his grotesque and claustrophobic and recognizably unamerican relationship with the faces he framed insanely, cropping them as if with butcher scissors—for something bidirectional, some respect we exercised for each other. He was an exception to a pattern of platonic relationships with male cinephiles I mostly kept that way, in part because I did not hope to taint those conversations after leaving the theater, as impersonal as they were impassioned. Some lasted years, became ultimately supportive, though when I squint it can seem peculiar: that our opinions were how we discovered each other, subtly and obliquely and much less than vulnerably. Those exchanges were always triangulated by the culture we’d swallowed in the dark, together or separately, recently or formatively, that triangulation multiplied by the cinephilic law that any single film be defined by its declension in film history. No matter how minor or campy or slapdash the screening, you could count on a discourse that attempted to tie it to the astonishing mass of the cinematic record. That bulk was the point, and it was also the fun.

***

Cinephilia claims a total scholarship of this bulk as its foundation, but like any claim of this nature, the realization of that goal is impossible. The more any scholarship of narrative art codifies its subjects, delineating traditions and schools so as to identify the deviations that birth others, it omits anomalies that feel insufficiently combustive with whichever zeitgeist. The bulk is the fun, but the game is how one sorts the bulk. The theorist Raymond Williams suggests that this kind of sorting of art is dependent on aversion or adherence to the dominant social character’s “structure of feeling”—an era’s popular methods of argument, the fictional images and narrative patterns that subtextually represent these conflicts, rather than the content of the arguments themselves. It’s a snaking piece of theory, one that can be applied only once an era has passed: measured by the contrasts of which works of narrative, supposedly most representative of how actual life felt, rose in the culture to meet, and shape, similar others. When I consider which renderings the female experience I did not consume earlier in my life, when they might have made a different person, the implications are much less academic than personal—astonishing as some serious illness that is long past, but not without consequence.

Agnes Varda’s Cléo from 5 to 7 (1962), for example, glorified a structure of feeling that let it ascend immediately to the feminist canon. I remember how it alienated me, when I saw it in my early twenties, that it didn’t make me feel as much as I was supposed to. The images of its protagonist—dreading the results of a biopsy, she enjoys a manic, episodic day around Paris, repeatedly shedding her fanciful clothes and changing theatrically in public into others—were felt, however subconsciously, to be in conversation with burgeoning second-wave feminism, its preoccupations with transforming external womanhood: bra-burning, armpit hair tufting in clouds, the condemnation of heels and the like. It could be called a picaresque, save the fact the harm inflicted by its protagonist is largely upon herself, which is to say, it is not exactly empowering. Notably, there is very little in the dialogue of Cléo that you could call overtly feminist, or even political, and her transformations are in no sense away from traditional femininity; in fact, they are toward it, into frillier hats and dresses. That the movie failed to move me must be because the threat of tragedy hinged on illness—physical turmoil, not mental autonomy. The landscape of the mind was mostly, or only, the place where the woman went to think about her body.

By the height of the second-wave movement, Claudia Weill’s arguably more feminist Girlfriends (1978)—which suffered funding issues and stop-and-start production over three years—met critical acclaim but swiftly fell into obscurity, likely because it had little to suggest or depict in the way of female presentation, or metamorphosis through it. It follows the steep estrangement of two previously inseparable women who move into separate, bittersweet fast lanes of career and family, each complexly conflicted about what she’s sacrificed. In contrast to Cléo, Girlfriends proffered no easily reproducible image of “feminism” that might have fit beside its Boomer activist counterpart of an easily reproducible slogan, the structure of feeling then hugely dominant. It is a melancholy film, but also coruscatingly funny, a quality which distinguished it from a then-voguish life-and-deathness about the female condition. It was only a woman in that type of emergency, I thought when I saw Girlfriends, much later than it would have been seminal, that I had been guided to study, and to become. That Cléo’s bodily emergency rose to canon, and Girlfriends’s furtive emergency of identity fell, was surely clinched by the fact that male-coded systems—medicine, law enforcement, heterosexual love—could help the first type of crisis, but had very little to do with the second.

While Girlfriends has gained a cult appreciation and many revivals (in no small part due to Kubrick’s fondness for it), it spawned few or no descendants in the late twentieth century. Claudia Weill went on to direct one feature that was panned, a number of TV movies, and later one episode of Dunham’s Girls; the film’s writer, Vicki Polon, is working through her seventies as an HR facilitator for dentists. Despite some critical praise at the time, the movie was a kind of sterile orphan in American cinema, not only furthering no lineage but seeming to come from none. In addition to exemplifying the popular structure of feeling, Cléo could be interpreted (as was the New Wave genre it belonged to) as a rebellious daughter of noir—the same fecund silences, the same stepping between clarifying light and emulsifying shadow, which further helped to situate it in canon. Because historiography is fond of cause and corollary, the more visible scholarship on “feminist cinema” in the two decades following Cléo readily included responses to it—Bergman’s Persona (1967), Fassbinder’s Veronika Voss (1983)—both of which deal with female psychology only as imperiled by corporeal trouble. If I picture the totality of cinema, a century and change as a family tree, it’s easy to see where one of these films sits: in conversation forever with other entries in a populated cluster. The other is a single point in the margins, only connected to others by the faintest line, even if increasingly linked to cousins as history maternally revises itself.

After the rise in streaming, cinematic history is rarely imagined or portrayed as tangible, but last summer I had the visceral experience of seeing it as a physicality. I went to visit a director friend in the bowels of a building where he was sorting through some fifty thousand VHS tapes, once the stock of a famed video rental shop in New York where he had worked in college. It took five escalators to reach the basement, and I remember saying, when I arrived, “This is the closest I’ve ever been to the center of the earth.” All the other people organizing the tapes alongside him were men, some of them middle-aged directors, some of them cherubic acolytes who aspired to become that, all of them plastic-gloved and quite happy to be there, matching tapes to cases, determining a system as they went. He was more relaxed than I’d ever seen him, absent the brilliant, birdlike agita that always seemed to be what moved him on brisk walks. Adjacent to the room of tilting stacks was a lightless shipping container, where I was briefly taken, stretching some fifty feet back and housing the merchandise not yet considered. I sat on the bare concrete floor of that basement in a dress, taken by their peace and industry but also increasingly confounded by the prospect of taxonomy: how it’s a peculiar task, when you think of it, taking the faithful custodian away from life at the same moment he attempts to describe it. “Do you dream of this?” I asked one of them, a little revolted at the prospect. “Every night,” he answered.

When I finally ascended into the weather outside, I wondered whether I’d just seen the most demonstrative possible literalizing of the cinephile. Perfectly cast as the sophisticated and adult apotheoses of the video-store-clerk caricature that Scream had depicted, they were comforted by patterns and titles and graphics almost interchangeable. I was walking under tall buildings then, thinking of different taxonomists I had loved and had always left, feeling as much in the cool shadow of that male procession as that of all the Financial District stone. The bird-watcher who had memorized a thousand names and went to far continents to learn others; the architect who would crouch to details as minute as a seam in a sidewalk to tell me what their classification meant, stunning me with how far the information reached—how the implications seemed to touch everything, but not everyone, around us.

I’d always found these qualities endearing until they were exasperating, when I might murkily consider how rarely taxonomy is blameless, how often it has been the tool of systematic oppression. You could argue that there are two families of bigotry, one fathered by simple ignorance and homophilia—I hate this group because they are unlike me, and so a threat—and another by a weaponized knowledge. I often recall the breathless section in Said’s Orientalism in which he describes the exhaustively researched books that the French and the English, arriving in Egypt and in India, presented to the leaders of the people they would colonize. With indexical concision, the gilded pages enumerated every observable aspect of the country they’d come to subjugate: the trees and the scriptures, the endemic diseases and the holidays, the funerary rites, the popular names for infants. We know this place better than it knows itself, they said, which was also a way of dehumanizing each person within it, each feeling anomaly whose life inevitably included behaviors and passions outside those pages’ classification. How often have I overheard some couple arguing, or been the target of similar vitriol, in which the accusation “This is just like you” arrives leveled as the greatest insult?

Certainly I had been guilty of worshipping those collectors I’d loved, but I still felt pride in how differently I went through the world, more clinched by sensations and hunches, a private investigator in my own life. I kept faith I’d be guided by an image that appeared and annotated the meaning of all that preceded, as Bresson dictated in his diaries that any frame he included must. Despite my boredoms with certain precautions, rarely had I missed the image portending violence—but when I wasn’t watching my own experience carefully enough, it was a dumbfounding cruelty to see the act-change in retrospect. I am thinking, for one, of a night in 2019 on which I was assaulted, in Rome, by a man who happened to be—or unsurprisingly was—a scholar of cinema.

The first quality of his I noticed, at an outdoor table where we had exactly two glasses of wine, was how he had the tendency of the academic or the polyglot to speak in elaborate, fully formed certainties only after he’d privately paused to determine them, looking elsewhere as he did. We’d met in a neighborhood I’d approved of because it was not near my hotel but also not near where he lived. It was good, he said, for walking. As a woman you develop certain superstitions against potential evils, and “the midpoint” has often been one of mine, a neutral territory as a safety: you have to pay, or think, to leave it. After the drinks we passed up and down hills, stopping at the low nasoni where I admired how athletically he hinged to drink over the mossy basins at his feet. We were discussing how, in Rome, many of the grand old cinemas are extinct: they were converted, around the turn of this century, into cavernous, lucrative bingo halls that prey on the elderly and the demented. Some time later, in a sloping plaza where we listened to a tilting cathedral’s mass, our subject became the scale of Pasolini’s movies—the way the low architecture of the Pigneto allowed that director to describe the misery of poverty, but also the expansive fantasies held by forgotten people, implicitly suggested in the selfsame visual gulps. At a certain point, I noticed he had not touched or in any way flirted with me. He was aware I was on tour to promote a translation of my recent novel, but when he perfunctorily asked after the facts of my day, and discovered I had been at certain TV and radio stations, he seemed confused, then silenced. Let back into his quiet as we continued to walk, he took turns that I automatically followed. Finally, on a loud side street where several bars spilled over from upstairs balconies, he stopped and pointed up to another, this one silent—the darkened doors shuttered, the neoclassical stone terrace giving off its cold patience.

“This is it,” he said. This is what, I asked. He thought he had mentioned, he said, how his family was remodeling a place just here. He had briefly referred to an apartment, but never where it was, nor that we had always been walking toward it. In a peculiar sequence of behavior, he unlocked the door, and then asked whether I wanted to see it. He was already entering the lobby, he was already ascending, and I was so taken aback that I followed. Upstairs there were centuried exposed beams, large sheets of plastic matted with particulate dust, and I watched him carefully opened the balcony doors before what happened did. At first it was fine, and then it was not; I said something, on the floor of the empty room, and then, instructed not to speak or move, I stopped saying it. I listened, instead, to the drunk young laughter of the people across the way. The bruises I examined later, with a clinical chill reminiscent of his, trying to classify which motions of his, or mine in reaction, had caused them.

The moment on the street had been the image that warped the others: he had wanted to walk so as not to look at me; the location had never been neutral; he had been gelid physically because he wanted control. He had never been confused about my work, but why I, who did not even live in that country, had certain honors for which he must have worked harder. Something I did not reflect upon until months later was the warm laugh he gave, once the assault had concluded, when I used the word brutal, and how he put a hand to my shoulder and called me a taxi—what this told me was how clearly he believed the event to have been consensual. While this is often the calculated lie told later by those guilty of sexual assault, more unusual was why he was capable of actually believing that, totally and immediately. It was not arbitrary that he’d spent his life articulating studious, autonomous power over images, ordering them to fit an argument. He was not like the lobby pugilist or the critic beleaguered by deadlines, not even much like the working director who might thrill at the practicalities of craft. Only four and a half years later, recalling the way he thought and spoke in private, richly cited paragraphs, how his very proprioception was synonymous with layers of film stills captured on the same Roman streets he’d grown up walking, can I recognize it: how he must have reached as close as anyone sane gets to feeling that they are changing the meaning of the movie by virtue of their watching it. I still don’t know if this makes him superior to me—who always submitted to the image, who could never quite change it—or if it makes him corrupted, or if it leaves him forsaken.

The taxonomist or the expert, the scholar or colonizer, is largely immune to threat or revelation. His knowledge situates any entity against its likenesses. But any matrix of fear—as well as any matrix of love—is always balanced on an emphatic novelty, however sometimes fanciful. “A crime like no other,” “A romance like no other.” These are ham-fisted movie loglines, and also similar to the hyperbolic phrases with which people narrate their lives in order to survive them. How banal or terrifying is it, that the saddest and happiest people run to the same sentiment: “I’ve never felt this way before”? If I’d isolated certain behaviors of that man and then grouped them, if I’d focused more on which type he represented instead of asking sincerely about who he was, maybe I would have solved it: been like the audience member in a movie who calls out advice and warnings, whom I’ve always despised as a fool, having taught myself to see any character as a fabricated surface, any image as intentional, coming toward me but not for me. To recognize isomorphisms—a “bad” man to a type of them, a film to its contemporaries—is a way of possessing the original object of comparison. But to be the possessor is also never to be the possessed, blessed occasionally with divinity. I never catalogue anything in my dreams, but once I swam off a porch, from some baroque and floating mansion, into an unending plane of water that appeared, with its lucid mirroring, to photograph the sky. It was a world without people, I understood—with fear, and with succor. My body was incomparable against it, and its perfect instrument.

***

Recently, I rewatched When a Stranger Calls Back, surprised to discover everything I hadn’t remembered, its innovative tensions with the genre’s formula. I had forgotten entirely that the antagonist, who hides in the wall, is revealed to be a ventriloquist—literalizing the pursued woman’s rapidly moving fear, rather than tying it to the person who provokes it, the movie’s ingenious coup de grace is to make the enemy bodiless, shape-shifting which corner it threatens from. The unusual fact of two female protagonists, one younger and one older—which is even more unheard of, a target over forty—had also slipped from memory. The maternal of the pair is played by an empowered and shoulder-padded Carol Kane, a survivor of assault who has assumed the protection of the younger woman. It is Kane the man in the wall is after, apparently enraged by this female solidarity; this bond itself is a phenomenon rarely seen in the horror genre, despite some characters’ first-act promises. Earlier in the film, teaching a self-defense course in a flickering community center, her waist-length hair echoing her gestures and emphasizing her actions like a chorus, the loving-if-hardened character contends: “You cannot say ‘I don’t believe in violence’ unless you also say ‘I don’t believe in living.’ ”

I must “believe” in violence—epistemic, visual, actual—and certainly in how each of these types of violence make the others possible, and likely, in perpetual recursion. What I do not appear to have believed in was living. What I mean is I did not pay that much attention to what was not the art I was consuming or making, that the most fulfillment and meaning came from decades in the psychic cave of the movies, the silence of galleries, the fourteen years of writing fiction that fed and housed me. Because I was practiced, even remunerated for disassociating from my own body and life, what that man did to me in Rome—and other similar violations, of which there are many, beginning with my father’s in childhood—feel far from the worst of what misogyny has given me.

That idea, my insistence that it’s the transgressions on my thinking I resent much more: perhaps that is the worst of it. The worst is that I can believe this and call it a native thought, not one informed by everything I watched that threw the woman’s body away, which must have urged me to make my mind the precious thing instead. As if I don’t remember sitting through a certain Altman film, at twenty-two or three, one of the last in an oeuvre I wanted to complete. As if this doesn’t mean watching a minor character, after he speechifies on his doeish girlfriend’s great sweetness and purity, gauge open her eye and face with a Coke bottle. As though the gore does not spill down her empire-waisted peach dress as her face in profile screams and gurgles, a carnage exacted for the benefit of a group of male characters seated in the foreground, and the fictional witnesses are not a sadistic mirror of the audience of men around me, and the moment in the fourth row does not slip almost psychedelic, becoming some exigent and ongoing forever in my mind. How quickly it changes, how feverish I feel, how enthralled everyone seems with some agreed-upon reality that makes no sense, the rules of which I need to learn, or have forgotten. What happens to the rest of my life if I get up to leave, instead of not moving at all, subservient to that terrifying covalent static in the theater, which I tell myself later is a laudatory response to high culture? What if I concentrate on the fact that this is not even a major plot point, that woman’s wet and bronchial scream, the distension of her eye socket?

When I began to write this, I believed the horror movie was the start of how I oriented my time, the primacy of the images that were not my life. Now I know it began with the photos of Polly, inescapable in 1993. If we memorized them closely enough, the adult wisdom went, she might be saved: she might live to become other images. But I think many of us children, the girls in particular, had another motivation, creeping and bodily. The reason is as sad and as unforgivable as what happened to Polly—whose exceptional beauty I was determined not to mention; whose great love was remembered to be theater, where she was magnetic with a slapstick charisma a little like Gilda Radner’s; who would now, improbably, be forty-three. Children retold the night again and again: how Richard Allen Davis held the knife to her throat at the sleepover, how afterward her friends lay there counting as he’d directed, their wrists bound by cut Nintendo cords. The Ford Pinto he drove, the gray hair he slicked back. So long as we went on interpreting these images, alongside the photos of Polly the family had released, they did not refer to us. Weren’t we like the woman in the theater who senses the male audience projecting onto what is projected, their throats catching and calves tensing as they list forward, becoming a part of the changing light?

I never cried when Polly was found, but I can heave and retch about it now, how we must have felt—however impermanently and guiltily, however aware of the sacrifice the dead girl had made for us, however ignorant of the ways our lives as women would later seem to contract—thrillingly, blackly, resolutely safe.

A fiction writer, critic, activist and essayist, Kathleen Alcott is the author of three novels and a short story collection, Emergency (W.W. Norton). Their work has appeared in The Best American Short Stories of 2019, The Best American Essays of 2024, Harper’s, The Guardian, Tin House, The Baffler, Zoetrope, The New York Times Book Review, Elle, and elsewhere. A recipient of a 2023 O. Henry Prize, Alcott also been nominated for the Joyce Carol Oates Literary Prize, the Mark Twain American Voice in Literature, The Sunday Times Short Story Award, and the Chautauqua Prize. They have taught at Columbia University and Bennington College; organized with Writers Against the War on Gaza and for healthcare justice; lived in France, Maine, Vermont, Austria, Arkansas, and California and recently returned to New York City.

June 14, 2024

The Measure of Intensities: On Luc Tuymans

Luc Tuymans, Polarisation—Based on a data visualization by Mauro Martino (2021).

Graphing is the practice of visualizing the abstract—the use of the coordinate plane not to map a territory or to demarcate a two-dimensional surface but to track a measurable quantity across space and time, quantities such as position, velocity, temperature, and brightness. Its invention can be traced to Nicole Oresme, bishop of Lisieux, courtier to Charles V, and scholastic philosopher-polymath who held forth at the College of Navarre of the newly founded University of Paris. His Tractatus de configurationibus qualitatum et motuum (Treatise on the Configurations of Qualities and Motions) from 1353 lays out early versions of what we now call functions and the x and y axes, which he referred to as “longitude” (the axis of the independent variable) and “latitude” (the perpendicular axis for plotting the values of the dependent variable). What made these pictures not merely illustrational but statistical “graphs” was Oresme’s radical insistence on presenting the variables in accurate ratio, with some accord of scale between the unit of measurement and the object or subject or process being measured. His key principle, at least when it comes to the visual, is: “The measure of intensities can be fittingly imagined as the measure of lines.”

Not content to have merely created graphing, Oresme also speculated about creating graphs of graphs, so-called complementary graphing that goes beyond the charting of an individual phenomenon into the charting of the relationships between sets or groups of multiple phenomena, an innovation that took the statistical combination of algebra and geometry just up to the border of what would become modern calculus.