The Paris Review's Blog, page 24

August 22, 2024

Death Is Very Close: A Champagne Reception for Philippe Petit

Photograph by Sean Zanni/PMC.

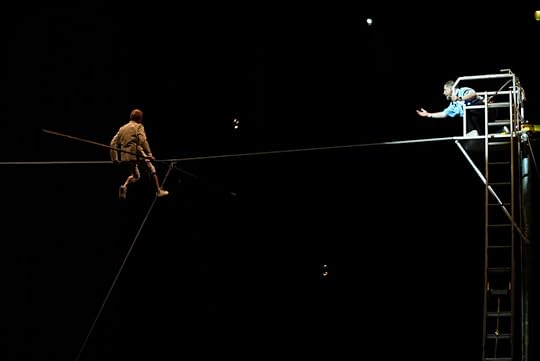

There was an air of subdued anticipation at the Cathedral of Saint John the Divine as we waited for Philippe Petit to take the stage. A clarinetist roved through the church improvising variations on Gershwin in spurts, making it hard to tell if the event, which was being held to commemorate the fiftieth anniversary of Petit’s walk between the Twin Towers, had begun. Eventually, the lights dimmed and we were told to turn off our phones, as even a single lit screen in the audience might cause Petit to fall from his tightrope. Music started, but so quietly that it seemed like it was being played from a phone, while a candlelit procession made its way down the nave. Large boards were set up, on which footage of the Twin Towers being constructed was projected. A group of child dancers imitated Petit’s walk along the ground, and were followed by a professional whistler. After we were shuffled through this sequence that felt like a performed version of ADHD, Petit finally appeared and began walking, first meekly, then quickly, to Satie’s “Gymnopédie No. 1,” wearing a white jacket laced with gold.

The original Twin Towers walk took place on the morning of August 7, 1974, after Petit and a group of conspirators broke into the World Trade Center while it was still partially under construction, and used a bow and arrow to span a tightrope between the towers. Petit walked, ran, lay down, and knelt on the wire, a quarter of a mile in the air, as the city looked on from below. It had taken more than eight months of meticulous planning to carry out the performance, including creating a mock-up of the distance between the Towers on a field in France, studying their engineering, and using various disguises and fake IDs to gain access to them. These heist-like aspects (it is referred to as “the coup”) have made it ripe material for movies including Man on Wire and The Walk, starring Joseph Gordon-Levitt as Petit and featuring CGI Twin Towers.

***

Three weeks before the performance, Petit held a reception in anticipation of the event on the eightieth floor of 3 World Trade Center. I exited the elevator into a space with perhaps the most impressive view of New York I’d ever seen. Under the influence of the height and temperature change (it was a hundred degrees outside that day), the vista was so impressive that it was almost addictive; it was hard to pull myself away from the windows, as though the space were designed to keep me there, like the interior of a casino.

The floor itself was open-plan and riddled with memorabilia from Silverstein Properties, the real estate firm owned by Larry Silverstein, which purchased the World Trade Center six weeks before September 11 and led the site’s redevelopment after the attacks. Littered around the space were newspaper and magazine covers about the rebuilding efforts, novelty-size ribbon-cutting scissors and fake keys, golden trophies and glass awards, posters for corporate events (“Dancing with the Silversteins”), pictures of Silverstein’s family, a red carpet with photos of runway shows that had taken place on the floor, works of art that had been made in the building’s studios, human-size scale models of the buildings, worn-out hard hats and boots, a full-scale I beam, American flags, emblems that commemorated every time a company like Uber or Spotify leased space in one of Silverstein’s buildings, the loudspeaker that George Bush used to give an address at Ground Zero, pieces of Petit’s clothing worn during the walk, and parts of a set from the show Succession, which apparently had been filmed there.

Outside the bathroom, a woman sat propped up against the wall, a victim of the heat, and was attended to by an employee who promised to bring her water. Inside the large windowless bathroom, an older man in white linen was standing at the sinks, scribbling notes on what looked like a piece of cardboard and talking to himself. He would consult his board, write something, then stare grimly, deadly, at himself in the mirror, before looking back at his board and beginning his recitation again. My presence didn’t seem to affect him at all.

Back in the main space, smooth jazz played overhead as champagne and hors d’oeuvres were served. Forty or fifty people circulated around me. Large, shiny real estate men mingled with aging artists; one group was talking loudly, nearly screaming, about how they’d just had lunch at Nobu, while another discussed the details of a recent real estate venture. An hour passed before the French cultural ambassador took to the stage to introduce Petit, whom I recognized as the man who had been talking to himself in the bathroom. He thanked the crowd, noting that he saw a lot of old friends in the audience. He began pointing to and naming some of them, causing others to raise their hands in hopes of being recognized. Clearly he’d forgotten some of them, as their hands remained in the air, as if they were desperate to be called on to answer a question. He pulled a red rose out of his pocket and said that he was going to balance it on the tip of his nose. “It is all about movement,” he said, before he placed the flower on his nose, splayed out his arms, and began walking from side to side. “The wire is never still, but moving, just like the buildings.” He moved his hands like a ball juggler.

Fifty years after the original walk, watching Petit gesticulate in an air-conditioned room with One World Trade Center behind him, it was hard not to feel that if the original event had been emblematic of the raw, unsupervised downtown New York of the seventies, this event perfectly encapsulated the downtown New York of today: every facet of life contained within a billion-dollar real estate development; a gluttony of high-efficiency glass, K-frames, and speculative investments.

After the talk, I spoke with Barry Greenhouse, who’d worked in the South Tower in the seventies, and had been Petit’s main contact in gaining access to the Twin Towers. Between roasted scallops, he told me about how he’d first seen Petit performing on the street in Paris, then saw him one day at the base of the Towers years later. Petit came and spoke to us briefly, and thanked Greenhouse for coming, before running off to the next group. Even offstage, he speaks and gesticulates quickly, almost as a form of misdirection. He has a clear gravitas and command of space, but arrives at that state almost by way of a frantic separateness; you get the sense that he isn’t really there, that he is moving ever farther away from you.

Still, the memory of him that stayed with me was the face I’d seen in the bathroom, and that I’d see again as he walked the tightrope. It’s a face that is like a death mask; gaunt, and filled with a particular worry, as if the severity of the situations he has put himself into over the years has imparted to him a certain darkness. The idea of death is embedded into all his performances; when you watch him cross the tightrope, half your mind is dedicated to thinking about him falling. The pleasure you get from watching is the feeling of your mind temporarily suspending that thought. What if he swayed too far to the side, if there was a gust? In the documentary Man on Wire, when describing the moment he shifted his weight from the South Tower to the wire, he says that he thought it was probably the end of his life, and that death was very close.

***

At Saint John the Divine, Petit sat at the edge of the rope on a metal platform that was fastened to a Gothic column. Satie continued to play as Merlin Whitehawk, a puppeteer, brought out a giant seagull made of wire on what looked like a fishing pole, a bit meant to re-create a scene that had happened between Petit and a real seagull during the original walk. Eventually Sting took the stage. “If blood will flow when flesh and steel are one,” he sang, as people in the flat church seating craned their necks to get a glimpse of him.

Petit walked, ran, lay down on, knelt, and sat on the rope over the next half hour before two fake policemen, dressed in loose, stripper-like fake uniforms, came to arrest him, ascending to the rope on a wobbly ladder; a slapstick that highlighted Petit’s particular form of artistry, which at times borders on vaudeville without ever fully crossing into it.

Petit picked the handcuffs and took the microphone to dispel some rumors about the original performance, including how long he’d actually walked (less than the initially reported forty-five minutes), and how long it had taken to plan the coup (months, not years). He apologized to his friend Jean-Louis Blondeau, who he said deserved much more credit for planning the original performance, and said that, after walking between the Towers, he’d become too egotistical to share the fame with those who had helped him. There was remorse in his voice, as if he sensed some end and felt the need to make amends. He left the stage to let Sting and others finish the show, only to come riding back out on his unicycle minutes later. Dressed now in black, he and Sting walked off stage arm in arm, with the rest of the performers in tow.

I watched the crowd leave as some—those who had paid five hundred dollars for their tickets—made their way to another private champagne reception at the back of the church.

Walking down Amsterdam Avenue in the light rain, I felt an intense alienation. Petit was impressive, but the performance was inescapably underwhelming. Simulating an original event that was impactful in part because of its spontaneity and illegality had only highlighted just how impossible that feat, or anything like it, would be in New York today.

The event that night had been replete with recordings of the New York Harbor and sirens (even as real sirens could be heard outside), in addition to the fake policemen and seagull puppet. All this had been done to evoke the 1974 walk, but part of what made that walk so profound was how ephemeral it was, how it had invoked the city to an almost sensational extent: it was the thousands of people who gathered on the streets below that gave it the aura of myth. Besides a few pictures, there is almost no documentation of Petit’s “coup” at all. It is this absence, not simulations, that reminds us most potently of what is gone. After 9/11, a good deal of what remained of the towers was sold as scrap metal to China to be melted down and reused; the debris that covered Lower Manhattan was trucked to the Fresh Kills Landfill in Staten Island. Below the nave in Saint John the Divine, in the basement’s crypt next to the children’s school, are fragments of the Twin Towers; below that, in the sub-basement, is a spring.

Patrick McGraw is the editor of Heavy Traffic .

August 21, 2024

Hearing from Helen Vendler

Helen Vendler in her home in Cambridge. Photograph by Stephanie Mitchell.

Earlier this year, the visionary poetry critic Helen Vendler died at the age of ninety. After her death, the writer and psychoanalyst Christopher Bollas—author of The Shadow of the Object, Cracking Up, and Meaning and Melancholia, among many others—collected a correspondence between himself and Vendler that unfolded over email during the last two years of her life, which began as Vendler was clearing out her office at Harvard in 2022. These emails, which have been selected and edited by the Review (with spelling and punctuation left unchanged), touch on the relationship between psychoanalysis and poetry; the experience of aging in all its forms; and the growth of a friendship, and understanding, between Bollas and Vendler.

January 22, 2022

Dear Christopher Bollas,

A friend of a friend quoted, in an email, your generous notion that what I do as a critic of poetry has a resemblance to the work of analysis. I take that as an amazing compliment. I don’t know where you said that, but I did see that one of the steps in your career was a PhD in English at an exciting time at the U. of Buffalo, and that you’ve written a series of books with intriguing titles, which (“now that I am old and ill”—Yeats) I may not get to immediately, but hope to see a couple of them once I finish the interminable task of clearing my office (now that we once again have access after the Covid ban).

Yours truly,

Helen Vendler

January 28, 2022

Dear Helen Vendler,

Well, I guess if you live long enough, along with the ordinary suffering (and the somewhat dispiriting knowledge—and now sense—of the ending), one may be visited by something remarkable, enlivening, and utterly unpredictable.

So when I saw your name on an e-mail yesterday, it was simply … well, I do not have words.

Except. Thank you. It is so kind and generous of you to write.

Your work has inspired me for so many decades and I have in most of my books used your revolutionary intelligence.

In my view, you understand unconscious thinking better than anyone. And I say so.

I gather you are clearing out your library (as am I) so I could send you a few of my books but you will not have room and frankly I am not a writer. That I have written a few books does not make me one and so I can spare you that.

But this last week when listening to a father talking about his son—they were at an impasse—I asked: “Have you read Sandburg’s Chicago Poems?”

I was as surprised by what I said as I suppose was he as I never recommend anything to analysands.

But he ordered it, he read it out loud to his adolescent, who grabbed it and took it to his room.

Does life get better than this?

With appreciation,

Christopher Bollas

January 28, 2022

The mot juste—“dispiriting”: it rang so true.

Congratulations on the Sandburg insight. Yes, such happy moments suffuse the day they occur—and years afterward. And for the lucky recipient they can be life-changing.

I would take the gift of a book very kindly. You choose.

I attach a new essay on a little-known poem by Hopkins that wrestles with “the selfless self of self”—of interest to you, perhaps as to me—a phrase that had long troubled me.

Yours,

Helen

P.S. No need to reply; but your offer of a book is delightful. You ARE a writer: nobody but an instinctive writer would have written so many serious books!

January 28, 2022

Dear Helen,

Would you be so kind as to send me a postal address so can send the book?

Best,

Christopher

P.S. Your wonderful essay, The Selfless Self of Self, brought back to mind the puzzle that certain essential words—like “self” or “jouissance” or “amae”—are deeply known by those speaking their language but no one can define them. Which I think is rather the point. My French friends insist that “self” cannot be translated into French and when I try to explain it, of course, I am in hot water. But these essential terms fascinate me because I think the word is almost the “thing”; it conveys an internal experience of knowledge that cannot be described.

January 28, 2022

Helen Vendler

58 Trowbridge St.

Cambridge, MA 02138

Thank you. Will I learn about “unconscious thinking?” I hope so. Helen

In a Facebook status, Vendler writes that she has Covid.

February 9, 2022

Dear Helen,

I am so sorry to hear you have covid and only hope it is the more moderate kind.

I wanted you to see a few paragraphs about your work in a manuscript that has been on my shelf for many years. (It can take ten years for me to finish a 50k manuscript.)

So, you will see yourself in a “work-in-progress” because you have asked how I could possibly use your work in the realm of psychoanalysis. You know more about unconscious thinking than anyone I know although I gather this is unconscious knowledge. All the better!

And odd fact of my unconscious. I have (in memory) merged Wyatt and Marvell. I connected “Time’s wingèd chariot hurrying near” with “They flee from me that sometime did me seek.” For at least a decade I thought this was Marvell.

I think I can see the connecting threads.

Christopher

February 12, 2022

I’m still waiting to read further in your book. But I see that for me you illuminate the links between achieved work by an artist and a successful preceding unconscious assemblage and consolidated genre of unconscious thought, and that that is why “inspiration” does not seem self-generated by the artist. That style is in fact the materialization on the page of a hidden (to the artist) internal web of unconscious thinking that has required time to form itself is I’m sure true, and that this revelation, by disposing of the idea of external inspiration, deeply depressed Hopkins is what I was groping after in the close of my piece on Hopkins.

You must know Keats’s ode on indolence—the best picture of “wise passiveness” that I know. His successive “visions” of what he imagined his unconscious was seeing and assembling could be much clarified if you took them on. I’m not at all sure I read them securely in my Keats book. Thanks so much for this!

H.

April 4, 2023

Dear Helen,

I do hope you are well.

I have been “enlisted” to speak with officials in European governments about Ukraine and Putin. The conversations and participants are all confidential but one of the most disturbing features of what is taking place is the utter lack of understanding of human psychology. These are intelligent people stuck in an adolescent frame of mind and they have no clue this is the case.

Am trying to finish up a book but hard to find the spirit.

Best,

Christopher

April 4, 2023

Deep in your gripping Oedipus. Still my livre de chevet, learning so much seeing things from your angle! Delay from health issues, but ongoing immersion in your pages.

I bet the “lack of understanding” in the officials is easily matched by higher-ups everywhere. It helps to be a mother, even better to be a single mother with no money for babysitting. Even better to be one who swore she would reject every aspect of her parents’ idea of child-raising. Even so, I had no idea how to teach young people when I started out. “Full-grown lambs” says Keats in “To Autumn”; the oddity of that phrase (“Why not say ‘sheep?’”) taught me that my students were “full-grown babies,” and I understood them much better.

With Rene’s thanks for the Bollas Reader—an excellent introduction to your originality—

Yours,

Helen

April 4, 2024

For “Rene” read “renewed.” Predictive spelling a devil’s gift. H.

May 9, 2022

Dear Helen,

Have enjoyed your lectures on You Tube.

Best,

Christopher

May 9, 2022

Dear Christopher,

I am sorry to have been delayed in writing more about the joyous experience of reading you. I’ve been sadly occupied arranging for hospice in home for my closest friend, whose health proxy I am. That was accomplished last Sunday, and I am relieved that it has been done. I think the end will come soon, so I grasp at this free day to write my delayed thanks.

It was the eeriest thing, reading your essay called “Psychoanalysis and Creativity,” where I saw the parallels between your remarks as a listener and my experience as a reader (and necessarily a listener too). The “gravitas” that brings the separate particles of experience into that grouping that you call “psychic genera” and from which you can glean, after hours of listening (more for that than for content as such), a sense of the map of the intermixed feelings and thinking processes of the analysand, also works exactly for the generation of style in poetry (which people generally don’t read for, being more interested in semantic content, philosophical implications, historical relevance, etc.).

It made me genuinely happy to see the parallels in lifting what may seem (but is not) accidental into visibility. The unknown known is a wonderful way of putting it. I think that the poets may be able to know more of the unknown known than the analysand, since the composition of poetry is a way to elicit it in symbolic form. And your explanation of the multiplicity of things to be inferred from words, gestures, emotions—and the tendency of those things to arrange themselves like iron filings to a magnet (as Donne says—“And Thou like adamant draw my iron heart”—) has its strict analogue in the way in which, after one immerses oneself (ideally) in everything an author wrote, those magnetic forms arise in my mind as “explanations” of stylistic gestures in a poem. One can’t command them; they have to rise as the result of a long process.

The frustration of not being able to understand something by will alone makes me remember a summer in which I was working very hard to understand Stevens’s long poems. I would teach summer school all morning, return and be with my son from noon till 7 (when he would fall asleep), and then going to my library office after the arrival of the babysitter, and work till late. It was a taxing schedule, but usually I could make progress. One night I was so despairing of figuring out 3 lines in Stevens’s last long poem that I burst into tears; then I suddenly heard a young voice behind me at my open office door in the deserted Smith library saying “Oh Mrs. Vendler, I’m just taking my sister—” and then broke off in an apology, seeing the tears running down my cheeks. I imagined she thought she was interrupting some tragic experience, and I didn’t want her to think that, so I said unthinkingly, “I’m all right, I was upset because I just couldn’t understand a passage in Wallace Stevens.” She probably thought anyone who wept for that reason was very peculiar. But in reading your passages in various essays where you say, “I was pondering X” or “I was piecing together,” or some other phrase intimating how much thinking you have to do to glean the visible off the impalpable in the analytic process, I felt that your thinking resembles mine—though for different reasons and for different results. And the “evidence” is often so “accidental”: I remember thinking about how Stevens used the definite and indefinite articles, and being frustrated because they were not included in the (predigital) Concordance.

I was struck by your comments on the artificial creations (adobe architecture, “Cape Cod”) of places in Orange County towns, as the opposites of architecture that has grown out of forms within temporally growing mentalities. My son has a house in Laguna Beach, and I’ve spent enough time there to know exactly those “theme park” constructions, as well as those like our “Sturbridge Village” in Mass., replicating a pioneer town with docents in historical costume. It’s a repellent sight if one has read any writings of the era. And, as you say, it’s all “fake”—not least because they have no Cotton Mather among the historical figures.

Of course, your reflections on everything from stand-up comics to serial killers are fascinating. Who hasn’t pursued comparable characterizations of comic or sadistic apparitions in culture? Your anecdotes (Ken Kesey and the Panthers) offer a moment of relief in the argument of a serious article, and your personal anecdotes are equally attractive on a written page. I often wish that the criticism of poetry offered that sort of relief to the reader, but I can’t manage it, not wishing to be intruding on Keats or Shakespeare. You’re working with human beings in actual life—so different from working with etymological and semantic and syntactic phenomena—but I wish I had your sense of relish of the human comedy (and tragedy). As you say, “A sense of humor … captures the intersection of two realities: the intentional and the unintentional— … breaking down one’s receptive equanimity upon encountering the ponderous”—and literary criticism is always leaning, if only slightly, in the directions of the ponderous. I love creative writers far more than scholars because of their disruption of the expected: I wish I had their wit. The “ironic fate” of any analytic session in its unwilled disruption of itself is a defense of listening with the third ear, which perceives that fate.

You have such interesting topics, but among them, the ways in which experience allows us—or drives us—to the invention of a “personal idiom” is particularly revealing. To think of selfhood as a “personal idiom” is very helpful to me, carrying, as it does, both verbal and visual implications. And your transformation of Freud’s “jokes” into excellent anecdotes (“rat” and “erratic” is my favorite) also enlivens your pages along literary lines. It’s always possible for a literary critic to miss such verbal play, and I’ve probably missed some in Stevens, and certainly in Shakespeare, who can’t help how much he loves them.

Well, enough. I’ll return to your articles; they even make me wish I had been in analysis. I didn’t understand it enough when I had friends in graduate school who were transfixed by it. But I did—twice—after bafflement, consult a therapist who clarified things from my past I thought I understood, but didn’t. I was being taught a new way of thinking, just by the intellectual reproof I took from her superior interpretation of the phenomena that had baffled me. She’s dead now, but I often think of the months I was lucky enough to have her in my life.

I treasure your “Reader.”

Thank you.

Yours delightedly,

Helen

Note from CB: Vendler likely meant the “unthought known,” a concept of mine, but unconsciously inserts her own interesting wording of the idea.

May 19, 2023

Dear Helen,

I hope this finds you well.

Here is a bit from a rough draft of the introduction to my notebooks (In the Stream of Consciousness) which will be published in 2024.

Best,

Christopher

“Shuffling off to Buffalo: English Literature and Psychotherapy Training”

In 1969 I drove east to the University of Buffalo where I was to do a PhD in English literature. At the time it was the most radical and creative English department in the country as Nelson Rockefeller—who called it the “university of the twenty-first century”—put a fortune into gathering a remarkable faculty. Many of the poets and writers from the Black Mountain School (which had closed) found their way to Buffalo, especially the doyen of that group, Charles Olson; as well as Robert Creely and Gregory Corso. They joined other poets and novelists—Robert Hass, Carl Dennis, and John Barth—and it was Hass who would change my way of thinking. In a seminar on Wordsworth’s “Prelude,” Hass and other faculty attending taught us how a poem thinks, an act of sustained immersion that of course demands that one suspend consciousness to simply allow one’s unconscious thinking to receive the logic of the poetic text.

Most great poems at first read elude consciousness. They are unconscious presentations and require hearing or reading again and again before one’s consciousness begins to gather—much less to consider and organize—some of that unconscious thinking. The subtitle of The Prelude is “Growth of a Poet’s Mind” and I think this work—along with Freud’s Interpretation of Dreams—became the background for my own views of unconscious thinking and free association.

To encounter any complex poem is remarkably similar to listening to any complex movement of patient association. The logic of a poem moves at times in cryptic condensations that are similar to free associative speech. The finest teacher of psychoanalytic thinking, in my view, is Helen Vendler. Read any of her books critically examining a poet and his or her work, and you find an evolution of Freudian method that is stunning. Her analysis of syntax opens up a perspective that allows us to see how and in what ways character is syntactical.

Buffalo had a strong contingent of French writers and philosophers such as Rene Girard, whose lectures on the “enemy twin” were complex musings on the psychic reality of the double: a forerunner of my own thinking on the borderline personality. Psychoanalysts such as Guy Rosolato (and others) would visit for some weeks. Rosolato’s detailed lecture on the movement of the phonemic—words echoing one another—was illuminating.

Our resident genius was Michel Foucault. His English was not great, and as my French was touristic I found his lectures hard to comprehend. But somewhere in my unconscious—my father was French—I seemed to understand him.

May 19, 2023

Dear Christopher,

A fascinating passage. Thanks for the kind nod to me. I look forward very much to the book. (A couple of typos here in proper names: “Creeley” and an acute accent on final e in Rene.)

You hope your note finds me well. Yes and no: I have some of the disabilities of being 90, and have consequently abandoned Cambridge for Laguna Niguel, CA, to live independently near my son and his family, who live in Laguna Beach. I think you’re somewhere nearby, if I recall correctly.

Yours,

Helen

May 20, 2023

Dear Helen,

Very kind of you to reply and thanks for the heads up about the typos.

I hope your move to Laguna Niguel is proving to be a good one. We moved from Santa Barbara to Venice a year ago in order to be near our son (he is a mile away or so) and we did that in the nick of time. I have had “ordinary” health issues for a near 80 year old but I hate regimented exercise (why count the blooming number of steps one takes?) and my frame of mind has let this old body down. But I am now exercising and improving and there is hope. I have declined spine surgery (severe stenosis) but I found a neurosurgeon and a neurologist who both agreed it was too risky. I made it clear I was not desperately afraid of death (loss of consciousness?) but I did fear dying. As soon as we made the decision I felt much better. Enjoying acupuncture and reflexology.

And a question that came to mind about six months ago. I asked myself “what ‘works’ of literature have changed the way you see the world?” Four came to mind right away: the Epic of Gilgamesh, Oedipus, Hamlet, Moby-Dick. I was surprised by the selection but it was fun to think about why these works and not others.

Life is endlessly interesting.

It would be wonderful to meet you one of these days. It is easy enough for us to visit you in Laguna or Laguna Niguel.

Best,

Christopher

August 7, 2023

Dear Christopher,

Forgive my belated reply to your last e-mail. I won’t even try to describe my excuses, both professional and personal. Almost every one of Hopkins’s letters begins with excuses, the basic one always being that the day’s demands filled up the day, which is pretty much true here, too.

I’d be delighted to have you visit, just to set eyes on you and hear your voice. I’m too infirm to make tea, and I live alone, so you’ll understand if I offer you and your wife cold drinks instead! Would you like to come on a weekend, when the traffic is not so fiendish?

I’m housebound, pretty much, so I leave it up to you to choose a date to visit. I no longer drive, and must use a walker, but also I have the fatigue of being 90, which is very strange: you just crash. I’ll attach a picture taken on my 90th birthday in my son’s house, just so you’ll recognize me. And what is your wife’s name?

Yours,

Helen

August 8, 2023

Dear Helen,

It is wonderful to hear from you and so kind of you to invite us for a visit.

We would love to come.

We will actually be in Laguna next week and could come by on Wednesday the 16th or Thursday the 17th if that works.

If not, then in October?

We go to our farmstead on the prairie (North Dakota) for September.

And 1 to 3 is perfect. You will see that I too hobble about (use a walker) and am in a new infantile stage which I try to make interesting. Certainly it is a curious time in the so-called “life span.”

When we do come to visit I will text you if need be. But I am rarely late.

You sure look a heck of a lot younger than 90 and it is good to see you!

My wife is Suzanne: English, architect.

Best,

Christopher

August 15, 2023

Dear Helen,

I am so sorry to say that I will not be able to see you tomorrow. I have been having vertigo for a few weeks now and my balance is so precarious that the decision was made on doctors’ advice that I stay put and just wait for … whatever.

I know you have health issues and reckon, like me, that you take it on the chin and just push on as best you can.

I hope you are able to visit the seashore, or the cliffs of Dana Point where one can gain a fine view.

My very best wishes,

Christopher

August 15, 2023

I’m so sorry; vertigo is awful (as I know from a friend with Menière’s disease). Of course I’m disappointed not to meet you tom’w, but when it’s possible, let me know. I hope your balance will return! There’s nothing worse than a bad fall; mine gave me a subdural hematoma.

My best wishes for your recovery, in return.

Helen

August 18, 2023

Dear Helen,

I am so sorry that I could not come to meet you.

I lost proprioception about 2 years ago and it has been an interesting struggle to find some way to reverse this. (I refuse to accept that this is “it” and I should just adapt).

I write now, however, to give some advice about the “hurricane” meant to descend. It is not true that we have not had the likes of this before: we have. (Laguna was flooded in the 1990s with town flooded all way up the canyon, etc.)

Perhaps you have been told what is important for you to have near you.

Please get bottled water or bottle what you have now as your water supply may be contaminated or compromised.

Close all your blinds that face the storm.

If you do not have a flashlight then do get one and have it near your bed along with cell phone.

Have food that does not require cooking.

You no doubt have a delivery account with Whole Foods or some such so you should be able to get what you need.

You are better on high ground and along the cliffs of the coast but you do not want to be in, say, Capistrano or downtown Laguna.

I reckon this is sensationalized but given climate change it may not be.

It should be rather beautiful and amazing. I loved the storms in Laguna.

Best,

Christopher

August 18, 2023

How kind of you, Christopher! I’m up on the ridge of a big hill and my son is on the top of the big bluff at Laguna beach, so we’ll be safe. I have no outside blinds, not lots of glass. I have sparkling water, milk, and OJ, plus plenty of food (and an instacart acc’t). I also have one of those “good for 3 hours of power” electrical lanterns and a superfluity of flashlights with intense light

I love storms, except for the destruction of trees post hoc.

Anent “adapting,” I feel like Millay: “I know. But I do not approve. And I am not resigned.” I’m very sorry that you have the trouble with proprioception. They are discovering new treatment methods every day, and I’m sure you have doctors that are at the top of the field: Are there new trials going on? My mother used to say, dismally, that Hope had to be practiced like a virtue, the surest sign of her own despair.

I hope you’re able to write: that does me a world of good. And my door is always open, needless to say, should your health improve.

Thanks for all the good suggestions. I’ll think of you if the thunder arrives. The 1938 hurricane blew down a big tree in our backyard as we three children begged our father to go out and hold it up.

Yours,

Helen

November 4, 2023

Dear Helen,

I hope this finds you well and enjoying the Dana Point sunrise.

I am sorry we could not meet up in the summer but I can come to Laguna this week or anytime really in November or early December if that suits you?

For a one hour visit and please there is no need to provide juice or tea. It would just be great to see you in person and say hello. Round 1pm?

I am around the house for another hour or so and then back after noon.

Best,

Christopher

November 4, 2023

Dear Christopher,

Terrific! But I have a series of scans and tests coming up through Nov 17th, and can’t foresee after that till I see the pneumonologist for the “wrap up” appt on the 17th. After that, any afternoon except Mon and Tuesday (fixed helper appts, lucky me). Sounds as if you’re doing better! It will be a pleasure meeting you and Suzanne if we can work this out after Nov 25.

As ever,

Helen

November 4, 2023

Dear Helen,

Good to hear from you and good luck with the scans.

Let’s see how it goes as we are quite flexible and can come for a visit in early December or if you prefer we could wait until January.

I am a bit better, thanks, as I have decided not to walk with a walker or cane or live in a wheelchair but “fight back” which feels better even if it is more hazardous. It was wonderful to be on the prairie although I found the airports and flight, etc., far harder than I expected. Still … this is an adventure!

Best,

Christopher

November 5, 2023

Congratulations. But I hope you use a quad cane!

Thanks for your kind indulgence.

I’ll write after seeing dr for “wrap up apt.” Don’t let our visit interfere with your Thanksgiving. Give yourself a day before and after, at least! H

November 6, 2023

I actually do not know the term a “quad cane” but I think I have seen the object and can imagine it.

I took a rather bizarre cane with me to Dakota. It is a single stick with a “seat” embedded in it which one can open and then just sit on it. Ugly as hell and ungainly. But it works if one is too tired to stand anymore and there are no seats or places to sit.

Am struggling to finish my “notebooks”: titled “Stream of Consciousness” as the publisher is eager to get on with it. But it is a risk. These have good moments but also very flawed ones. I think I want to publish the flaws because it is my own truth: of thinking, revising, contradicting myself, etc. etc.

An odd time.

Maybe a trip to Laguna will turn me around!

Best,

Christopher

November 6, 2023

Dear Christopher,

I too had one of those X-canes, but it wasn’t enough for long waits, so at airports I resigned myself to a wheelchair (not even realizing it brought you to the front of the security line). One of these days Elon Musk will undo the ADA and forbid wheelchairs on flights so as to save money: ever since Trump mocked the handicapped man, and the Trumpists laughed, things have gotten worse.

Do you know that predictive spelling for “I’ll” gives, as its first choice, “ill”?

Are there more “ill” people than “I” people? By body-count? Or by which of their weird protocols—“capital letters before lowercase,” perhaps?

I’ll be back in touch. You are courageous!

Helen

November 29, 2023

Dear Helen,

Would it work for you if we came for a one hour visit on Saturday, Sunday, or Monday the 10th, 11th, or 12th of December around 11 am?

If not, then I reckon we could come late January or early February.

There is no need to do anything other than let us in!

We do not need tea, coffee, or anything.

Best

Christopher

November 29, 2023

Any chance of a later, afternoon visit? I’m a night owl, hardly compos mentis before 1pm. (And ever such: I did my PhD thesis between midnight to 4am.)

But you may have lunch plans that would interfere with a later time: if so, we’ll stick with 11 am.

My “procedures,” so tiresome, came out well, nothing more than COPD, with portable oxygen for any day promising to be tiring.

Yours,

Helen

November 29, 2023

We can come anytime in the afternoon. How about 2pm?

Well … you have stamina amongst other gifts. When I applied for college my core worry was “how am I going to survive in a place where I hear they stay up until 11 pm?” I always went to bed at 9pm sharp. This anxiety vanished soon after I arrived. Such is the stream of life.

By the way, am musing over “I’ll” and “ill” which is fascinating …

Am working on “inner conversation” which I find fascinating and it is, as you know, utterly ignored by psychoanalysis. But surely this is our most important conversation. I loved Blanchot’s book on it. Bataille tried and of course Vygotsky. But … no one seems to get it or be able to represent it.

I believe that love of one’s self is so deeply important. And I think our conversations with our self are so crucial. Certainly in February of this year when my GI system simply stopped almost completely for a week and no one knew what to do I changed from the occasional yelp (it was painful) to a conversation. I literally spoke to my swollen abdomen as if it were an infant. And this helped. The pain came in surges every 15 minutes or so and so I did have respite. By speaking to my belly-infant I actually consoled my self. This is embarrassing but … what the heck? What does one have to lose at this point?

So Tuesday the 12th at 2pm?

We really look forward to it.

Best

Christopher

November 29, 2023

Tues 12 at 2 it is, thank you, H

December 8, 2023

Dear Helen,

I am so sorry to say that I have a rather bad cold (3rd day of) and have looked up how long I am infectious and it states that one is until all symptoms are gone: usually two weeks.

This means that I should not come to visit you until all the symptoms are gone and that won’t allow us to meet in the next weeks.

Perhaps we can chat on the phone?

I hope you are well.

Best,

Christopher

December 8, 2023

Dear Christopher,

I’m so sorry about your bad cold, just when you’re deep in the planning for your diaries. Somehow I shrink from a spectral voice. If a visit becomes possible, fine; if not, that’s OK, too. A pleasure shouldn’t become an obligation.

Yours with best wishes for your recovery!

Helen

Helen Vendler died on April 23, 2024. She and Christopher Bollas never met.

August 20, 2024

Self-Portrait in the Studio

All images courtesy of the author.

A form of life that keeps itself in relation to a poetic practice, however that might be, is always in the studio, always in its studio.

Its—but in what way do that place and practice belong to it? Isn’t the opposite true—that this form of life is at the mercy of its studio?

***

In the mess of papers and books, open or piled upon one another, in the disordered scene of brushes and paints, canvases leaning against the wall, the studio preserves the rough drafts of creation; it records the traces of the arduous process leading from potentiality to act, from the hand that writes to the written page, from the palette to the painting. The studio is the image of potentiality—of the writer’s potentiality to write, of the painter’s or sculptor’s potentiality to paint or sculpt. Attempting to describe one’s own studio thus means attempting to describe the modes and forms of one’s own potentiality—a task that is, at least on first glance, impossible.

***

How does one have a potentiality? One cannot have a potentiality; one can only inhabit it.

***

Habito is a frequentative of habeo: to inhabit is a special mode of having, a having so intense that it is no longer possession at all. By dint of having something, we inhabit it, we belong to it.

***

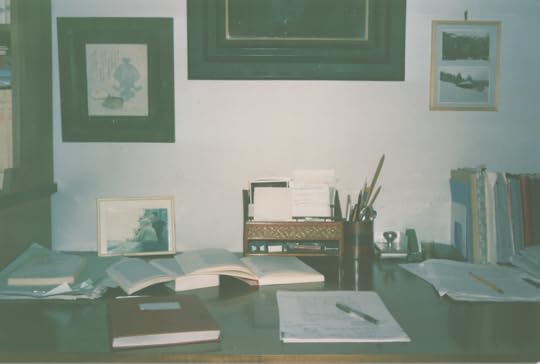

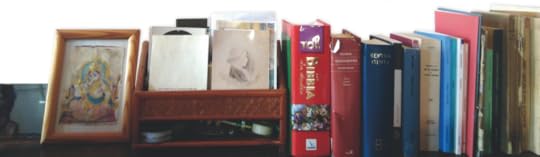

The objects of my studio have remained the same, and years later in the photographs of them in different places and cities, they seem unchanged. The studio is the form of its inhabiting—how could it change?

***

In the wicker letter tray against the wall at the center of the desk in both my studio in Rome and the one in Venice, on the left there is an invitation to the dinner celebrating Jean Beaufret’s seventieth birthday, on the front of which is written this line from Simone Weil: “Un homme qui a quelque chose de nouveau à dire ne peut être d’abord écouté que de ceux qui l’aiment.” The invitation carries the date May 22, 1977. Since then, it has always remained on my desk.

***

One knows something only if one loves it—or as Elsa would say, “only one who loves knows.” The Indo-European root that means “to know” is a homonym for the one that means “to be born.” To know [conoscere] means to be born together, to be generated or regenerated by the thing known. This, and nothing but this, is the meaning of loving. And yet, it is precisely this type of love that is so difficult to find among those who believe they know. In fact, the opposite often occurs—that those who dedicate themselves to the study of a writer or an object end up developing a feeling of superiority towards them, almost a sort of contempt. This is why it is best to expunge from the verb “to know” all merely cognitive claims (cognitio in Latin is originally a legal term meaning the procedures for a judge’s inquiry). For my own part, I do not think we can pick up a book we love without feeling our heart racing, or truly know a creature or thing without being reborn in them and with them.

***

The photograph with Heidegger to my left, in my studio on Vicolo del Giglio in Rome, was taken in the countryside of Vaucluse during one of the walks that punctuated the first seminar at Le Thor in 1966. At a distance of half a century, I cannot forget the landscape of Provence immersed in the September light, the white rocks of the boris, the great, steep hump of Mont Ventoux, the ruins of Sade’s Château de Lacoste perched on the rocks. And the feverish, star-pierced night sky, which the moist gauze of the Milky Way seemed to want to soothe. It is perhaps the first place I wanted to hide my heart—and there, untouched and unripe as it was, my heart must have remained, even if I could no longer say where—perhaps under a boulder in Saumane, in a cabin of Le Rebanqué, or in the garden of the little hotel where Heidegger held his seminar every morning.

***

What did the meeting with Heidegger in Provence mean to me? I certainly cannot separate it from the place where happened—his face at once gentle and stern, intense and uncompromising eyes that I have never seen elsewhere save in a dream. In life there are events and meetings that are so decisive that it is impossible for them to enter into reality completely. They happen, to be sure, and the mark out the path—but they never cease to happen, so to speak. Continuous meetings, in this sense, as theologians say that God never ceases to create the world, that there is a continuous creation of the world. These meetings never cease to accompany us until the end. They are part of what remains unfinished in a life, what goes beyond it. And what goes beyond life is what remains of it.

***

I remember, in the dilapidated church of Thouzon, which we visited on one of our excursions in Vaucluse, the Cathar dove carved inside the architrave of a window in such a way that no one could see it without looking in the opposite of the usual direction.

***

That small group of men who, in the photograph from September 1966, walk together toward Thouzon—what ever became of it? Each in his own way had more or less consciously meant to make something of his life—the two seen from the back on the right are René Char and Heidegger, behind them myself and Dominique—what became of them, what became of us? Two have been dead a long time; the other two are, as they say, getting on in years (getting on toward what?). What matters here is not work, but life. Because on that late sunny afternoon (the shadows are long) they were alive and felt it, each intent in his thoughts, that is, in the bit of good that he had glimpsed. What has become of that good, wherein thought and life were not yet divided, wherein the feeling of the sun on the skin and the shadow of words in the mind so happily merged?

***

Smara in Sanskrit means both love and memory. We love someone because we remember them and, vice versa, we remember because we love. In loving we remember and in remembering we love, and in the end we love the memory—that is, love itself—and we remember love—that is, memory itself. This is why loving means being unable to forget, being unable to get a face, a gesture, a light out of your mind. But in truth it also means that we can no longer have a memory of it, that love is beyond memory, immemorably, ceaselessly present.

***

A page from Nicola Chiaromonte’s notebooks contains an extraordinary meditation on what remains of a life. For him the essential issue is not what we have or have not had—the true question is, rather, “what remains? . . . what remains of all the days and years that we lived as we could, that is, lived according to a necessity whose law we cannot even now decipher, but at the same time lived as it happened, which is to say, by chance?” The answer is that what remains, if it remains, is “that which one is, that which one was: the memory of having been ‘beautiful,’ as Plotinus would say, and the ability to keep it alive even now. Love remains, if one felt it, the enthusiasm for noble actions, for the traces of nobility and valor found in the dross of life. What remains, if it remains, is the ability to hold that what was good was good, what was bad was bad, and that nothing one might do can change that. What remains is what was, what deserves to continue and last, what stays.”

The answer seems so clear and forthright that the words that conclude the brief meditation pass unobserved: “And of us, of that Ego from which we can never detach ourselves and which we can never abjure, nothing remains.” And yet, I believe that these final, quiet words lend sense to the answer that precedes them. The good—even if Chiaromonte insists on its “staying” and “lasting”—is not a substance with no relation to our witnessing of it—rather, only this “of us nothing remains” guarantees that something good remains. The good is somehow indiscernible from our cancelling ourselves in it; it lives only by the seal and arabesque that our disappearance marks upon it. This is why we cannot detach ourselves from ourselves or abjure ourselves. Who is “I”? Who are “we”? Only this vanishing, this holding our breath for something higher that, nevertheless, draws life and inspiration from our bated breath. And nothing says more, nothing is more unmistakably unique than that tacit vanishing, nothing more moving than that adventurous disappearance.

***

Every life always runs along two levels: one seemingly governed by necessity, even if, as Chiaromonte writes, we cannot decipher its law, and another that is abandoned to chance and contingency. There is no point in pretending there is some arcane, demonic harmony between these two (this is the hypocritical claim that I was never able to accept in Goethe), and yet, once we manage to look at ourselves without disgust, the two levels, though uncommunicating, do not exclude or contrast with each other; rather, they offer each other a sort of serene, reciprocal hospitality. This is the only reason why the thin fabric of our life can slip out of our hands almost imperceptibly, while the facts and events—that is, the errors—that lay its warp attract all our attention and all our useless care.

***

What accompanies us through life is also what nourishes us. To nourish does not simply mean to make something grow; above all, it means to let something reach the state to which it naturally tends. The meetings, the readings, and the places that nourish us help us to reach this state. And yet, something in us resists this maturation and, just when it seems close, stubbornly stops and turns back toward the unripe.

A medieval legend about Virgil, whom popular tradition had turned into a magician, relates that upon realizing he was old he employed his arts to regain his youth. After having given the necessary instructions to a faithful servant, he had himself cut up into pieces, salted, and cooked in a pot, warning that no one should look inside the pot before it was time. But the servant—or, according to another version, the emperor—opened the pot too soon. “At the point,” the legend recounts, “there was seen an entirely naked child who circled three times around the tub containing the meat of Virgil and then vanished and of the poet nothing remained.” Recalling this legend in the Diaspalmata, Kierkegaard bitterly comments, “I dare say that I also peered too soon into the cauldron, into the cauldron of life and the historical process, and most likely will never manage to become more than a child.”

Maturing is letting oneself be cooked by life, letting oneself blindly fall—like a fruit—wherever. Remaining an infant is wanting to open the pot, wanting to see immediately even what you are not supposed to look at. But how can one not feel sympathy for those people in the fables who recklessly open the forbidden door.

In her diaries, Etty Hillesum writes that a soul can be twelve years old forever. This means that our recorded age changes with time but the soul has an age of its own that remains unchanged from birth to death. I don’t know the exactly age of my soul, but it surely cannot be very old, in any case not more than nine, judging from the way I seem to recognize it in my memories from that age, which have thus remained so vivid and sharp. Every year that passes, the gap between my recorded age and the age of my soul widens and the feeling of this difference is an ineliminable part of the way I life my life, of both its great imbalances and its precarious equilibriums.

***

You can make out the title of the book lying on the left side of the desk on Vicolo del Giglio: La société du spectacle by Guy Debord. I don’t remember why I was rereading it—I first read it back in 1967, the very year of its publication. Guy and I became friends many years later, at the end of the eighties. I remember my first meeting with Guy and Alice at the bar of the Lutetia, the immediately intense conversation, the sure agreement about every aspect of the political situation. We had both arrived at one and the same clarity, Guy starting from the tradition of the artistic avant-gardes, myself from poetry and philosophy. For the first time I found myself speaking about politics without having to bang against the obstacle of useless and misguided ideas and writers (in a letter Guy wrote to me some time later, one of these glibly exalted writers was soberly liquidated as ce sombre dément d’Althusser . . . ) and the systematic exclusion of those who could have oriented the so-called movements in a less ruinous direction. In any case, it was clear to both of us that the main obstacle barring the way to a new politics was precisely what remained of the Marxist tradition (not of Marx!) and the workers’ movement, which was unwittingly complicit with the enemy it believed it was combatting.

During our subsequent meetings at his house on the rue du Bac, the relentless subtlety—worthy of a magister of Vico de li Strami or a seventeenth-century theologian—with which he analyzed both capital and its two shadows, one Stalinist (the “concentrated spectacle”) and one democratic (the “diffuse spectacle”), never ceased to amaze me.

***

The true problem, however, lay elsewhere—closer and, at the same time, more impenetrable. Already in one of his first films Guy had evoked “that clandestinity of private life regarding which we possess nothing but pitiful documents.” It was this most intimate stowaway that Guy, like the entire western political tradition, could not get to the bottom of. And yet the term “constructed situation,” from which the group took its name, implied that it was possible to find something like “the northwest passage of the geography of real life.” And if in his books and films Guy comes back so insistently to his biography, to the faces of his friends and the places where he had lived, it is because he obscurely sensed that this was exactly where the secret of politics lay hidden, the secret on which every biography and every revolution could not but run aground. The genuinely political element consists in the clandestinity of private life, and yet, if we try to grasp it, it leaves us holding only the incommunicable, tedious quotidian. It was the political significance of this stowaway—which Aristotle had, with the name zōē, both included in and excluded from the city—that I had begun to investigate in those very same years. I, too, albeit in a different way, was seeking the northwest passage of the geography of real life.

Guy did not care at all about his contemporaries, and he no longer expected anything from them. As he once told me, for him the problem of the political subject by now boiled down to the alternative between homme ou cave (to explain the meaning of this unknown argot term, he pointed me to a Simonin novel that he seemed fond of, Le cave se rebiffe). I do not know what he might have thought of the “whatever singularity” that years later the Tiqqun group would make—with the name Bloom—the possible subject of the politics to come. In any case, when some years later he met the two Juliens—Coupat and Boudart—and Fulvia and Joël, I could not have imagined a closeness and, at the same time, distance greater than the one that separated them from him.

In contrast to Guy, who read narrowly but insistently (in the letter he wrote to me after reading my “Marginal Notes on Commentaries on the Society of the Spectacle” he referred to the writers I had cited as “quelques exotiques que j’ignore très regrettablement et [ . . . ] quatre ou cinque Français que je ne veux pas du tout lire”), in the readings of Julien Coupat and his young comrades you would find the author of the Zohar mingling with Pierre Clastres, Marx with Jacob Frank, De Martino with René Guénon, Walter Benjamin with Heidegger. And while Debord no longer hoped for anything from his peers—and if one despairs of others one also despairs of oneself—Tiqqun had wagered—albeit with all possible wariness—on the common man of the twentieth century, the Bloom as they called him, who precisely insofar as he had lost all identity and all belonging could be capable of anything, for better and for worse.

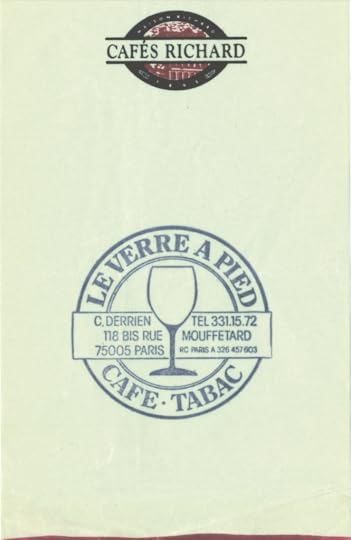

Our long discussions in the locale at 18 rue Saint-Ambroise—a café that they had left as it was, with its sign Au Vouvray, which still drew in a few passersby by mistake—and at the Verre à pied in Rue Mouffetard have remained as vivid in my memory as those that had animated the evenings at the farmhouse in Montechiarone in Tuscany ten years earlier.

***

In this farmhouse that Ginevra and I—following an unfathomable whim of that spirit that wanders where it will—rented in the Sienese countryside between 1978 and 1981, we spent evenings with Peppe, Massimo, Antonella, and later, Ruggero and Maries, that I can only describe as “unforgettable”—even if, as is the case with every truly unforgettable thing, there now remains nothing but a cloud of insignificant details, as if their truer meaning had sunk into the abyss somewhere—but the abyss, in heraldry, is the center of the shield and the unforgettable resembles an empty blazon. We talked about everything, a passage from Plato or Heidegger, a poem by Caproni or Penna, the colors in one of Ruggero’s painting or anecdotes from friends’ lives, but as in an ancient symposium, everything found its name, its delight, and its place. All this will be lost, is already lost, entrusted to the uncertain memory of four or five people and soon to be forgotten entirely (a faint echo of it can be found in the pages of the seminar on Language and Death)—but the unforgettable remains, because what is lost is God’s.

***

(What am I doing in this book? Am I not running the risk, as Ginevra says, of turning my studio into a little museum through which I lead readers by the hand? Do I not remain too present, while I would have liked to disappear in the faces of friends and our meetings? To be sure, for me inhabiting meant to experience these friendships and meetings with the greatest possible intensity. But instead of inhabiting, is it not having that has got the upper hand? I believe I must run this risk. There is one thing, though, that I would like to make clear: that I am an epigone in the literal sense of the word, a being that is generated only out of others, and that never renounces this dependency, living in a continuous, happy epigenesis).

***

From the window on Vicolo del Giglio you could see only a roof and a facing wall whose plaster, deteriorated in many places, left glimpses of bricks and stones. For years my gaze must have fallen, even distractedly, on that piece of ocher wall burnished by time, which only I could see. What is a wall? Something that guards and protects—the house or the city. Childlike tenderness of Italian cities, still enclosed within their own walls like a dream that stubbornly seeks shelter from reality. But a wall does not merely keep things out; it is also an obstacle that you cannot overcome, the Unsurmountable with which sooner or later you must contend. As every time one comes up against a boundary, various strategies are possible. A boundary is what separates an inside from an outside. We can, then, like Simone Weil, think of a wall as such, so that it remains thus up to the end, with no hope of leaving the prison. Or rather, like Kant, we might make the boundary the essential experience, which grants us a perfectly empty outside, a sort of metaphysical storage space in which to place the inaccessible Thing in itself. Or instead, like the land surveyor K., we might question and circumvent the borders that separate the inside from the outside, the castle from the village, the sky from the earth. Or even, like the painter Apelles in the anecdote related by Pliny, cut the borderline with an even finer line in such a way that outside and inside switch sides. Make the outside inside, as Manganelli would say. In any case, the last thing to do is bang our heads against it. The last—in every sense.

Translated from the Italian by Kevin Attell.

From Self-Portrait in the Studio, to be published this October by Seagull Books.

Giorgio Agamben is one of Italy’s foremost contemporary thinkers.

Kevin Attell teaches at Cornell University in Ithaca, New York, and is the author of Giorgio Agamben: Beyond the Threshold of Deconstruction.August 16, 2024

On Asturias’s Men of Maize

Asturias, ca. 1925. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

For millions of people in the Americas, our Indigenous heritage is something tinged with mystery. We look into a mirror and believe we see the Mayan, the Aztec, or the Apache in our faces. The hint of a high cheekbone; the very loud and obvious statement of our cinnamon or copper skin. We sense a native great-great-grandparent in our squat or long torsos, in the shape of our eyes, in our gait, and in the emotions and the spirits that drift over us at times of joy and loss. But the particulars of our Indigeneity, the weighty and grounded facts of it, have been erased from our history.

In my Guatemalan-immigrant childhood, the great Mayan jungle city of Tikal was a symbol of the civilization in our blood. Despite the humility of our present in seventies Los Angeles—my mother was a store cashier, my father a parking-lot valet—we were once an empire. My father suggested that a personal, familial greatness was there in our Mayan heritage, waiting to reawaken. I could not trace who my Mayan forebears were, exactly. But I knew the Maya were in me because I was a guatemalteco; or, in the hyphenated ethnic nomenclature of the time, a “Guatemalan-American.” Only now do I realize how deeply fraught the idea of being “Guatemalan” truly is. “Guatemala” is a way of glossing over the cultural collisions and the racial violence that produced a country centered in the mountain jungles and river valleys where Mayan peoples ruled themselves until Europeans came.

Men of Maize is Miguel Ángel Asturias’s Mayan masterpiece, his Indigenous Ulysses, a deep dive into the forces that made and kept the Maya a subservient caste, and the perpetual resistance that kept Guatemala’s many Mayan cultures alive and resilient. Like most people born in Guatemala, Asturias more than likely had some Indigenous ancestors, even though his father, a judge, was among the minority of Guatemalans who could trace their Spanish heritage to the seventeenth century. When the dictatorship of Manuel Estrada Cabrera (later the subject of Asturias’s novel Mr. President) sent the future author’s father and family into an internal exile in the Mayan‑centric world of provincial Alta Verapaz, the young Miguel Ángel fell deep into the great well of Indigenous culture for the first time.

In the 1920s, Asturias left for Paris to study. Soon he would become a member of a generation of Latin American thinkers influenced by the Eurocentric aesthetics and worldviews of the time: modernism, surrealism, socialism. In his own artistic practice, these ideas would fuse with the Indigenous spirituality and consciousness of the Americas. The life stories and the mythology of common Mayan and “mixed” folk of Guatemala would appear in his work, and influence it, again and again. In Men of Maize, he rejected the superficiality and sentimentality to be found in so many works about Indigenous cultures written by outsiders. The Mayan families in the novel are not hapless, helpless victims living out one tragedy after another in the face of the relentless march of modernity. Instead, in a frenzy of surreal stories and images, their ghosts and folktales and visions take over the narrative. Darkness comes streaming out of an anthill. A postman transforms into a coyote. Fire sweeps across the corn‑covered landscape, both as a tool of ruthless capitalism and as an agent of peasant retribution. In this fashion, Asturias reimagined the birth of Guatemala as a mad, disorderly event that unleashed countless personal and familial passions: betrayal, mourning, love, loyalty, and revenge.

It’s more than a little ironic that winning the Nobel Prize in 1967 made Asturias a symbol of national pride in Guatemala. By then, the writer had fled the country to escape the military dictatorship brought to power in a 1954 CIA‑backed coup. In the decades that followed, Guatemala’s elites assimilated Mayan Indigeneity into a soft‑focus narrative about the country’s national identity. Guatemala’s tourism ministry, Inguat, produced countless posters for airports and travel agencies depicting Mayan temples and stelae, and Indigenous women dressed in traditional textiles. In this “official” story, the nation’s Indigeneity was something colorful and harmless, a commodity to market to cash‑spending Europeans and norteamericanos.

My parents were in their mid‑twenties and living in Los Angeles when Asturias won the Nobel. For my father, especially, the writer’s triumph became yet another symbol of our inherent Guatemalan greatness. When we drove through Mexico on a family trip to Guatemala a few years later, he stopped somewhere along the way and bought several of his books. I remember, vividly, the beautiful woodcuts of their paperback covers, produced by the Argentine publisher Losada. On the cover for Hombres de maíz, a yellow face with enormous eyes stared out from behind black cornstalks. But I could not read that book, or any of the other Asturias books my father brought home. They were in Spanish, a language that was slowly dying in my U.S.‑educated brain.

When I returned to Guatemala in the eighties as a college educated, Spanish‑fluent adult, I mimicked Asturias’s artistic practice and began to collect the oral histories of my relatives. (Asturias’s first book, Legends of Guatemala, begins with the epigraph “For my mother, who used to tell me stories.”) I had my first grown‑up conversations with my maternal grandfather and my paternal grandmother, both people of striking Indigenous features. My grandfather had been born in Tecpán, Guatemala, a center of the Kaqchikel Maya; and my grandmother was from Huehuetenango, the capital of Guatemala’s Mayan north‑west frontier, the city and nearby villages home to the Mam, K’iche’, and other peoples. I asked them both the question so many young Latino people want to ask their elders: What are we? To what tribe or nation do we belong? Both answered: “No, we’re Spanish.” We were not Indian, they insisted, despite all the evidence to the contrary.

At the end of the twentieth century, it was still taboo for a person of “mixed” heritage to embrace their Mayan identity. Among the “Ladinos” (as the mixed population of Guatemala call themselves), Indigeneity remained associated with backwardness and passivity. “Indio” was an insult equivalent to “stupid.” These racist ideas endured despite all the books Asturias had written. Despite Mulata de Tal and Leyendas de Guatemala. Despite Men of Maize. Despite the shining gold medal handed to him by the Swedish Academy.

Four years after his father’s Nobel, Rodrigo Asturias, the novelist’s oldest son, founded a leftist guerrilla movement. He took as a nom de guerre the name of a character from the opening chapter of Men of Maize: Gaspar Ilom, the leader who resists the encroachment of outsiders on Indigenous lands. In the seventies and eighties, the Gaspar Ilom who was inspired by a fictional character built a real‑life army whose ranks grew to include legions of Mayan fighters. On the same trip to Guatemala on which I pressed my grandparents about our Indigenous heritage, I traveled through the countryside and saw bombed bridges and rebel graffiti—the calling cards of that largely Indigenous guerrilla army. What I saw inspired a scene in my first novel, The Tattooed Soldier, a book that tackled the legacy of the genocidal war that the Guatemalan government launched against a Mayan rebellion.

When I finally read Men of Maize, I saw echoes of my family story in every chapter. My grandfather had told me of a days‑long walk he undertook as a young man, sleeping in the town squares with other travelers along the way. In Asturias’s novel I read of “rivulets of local folk” on the highways, “their bedding stored away in cane baskets” so that they, too, could sleep along the road. Asturias describes a shaman’s ritual to induce “spider‑spells” that involves the sprinkling of red pinole powder, flour, and tortilla crumbs on a straw mat; I have a vague memory of being a boy and my mother taking me to see a woman doing something very similar. Soon I understood that our family’s Indigeneity was not a great black hole of mystery, but rather something alive and very real inside of me. In my memories, in our way of being.

Men of Maize describes the birth of a new people. Or, put another way, it describes the journey of an ancient people into a new age. A time when they don Western clothes and marvel at the miraculous interventions of their non‑Western deities in a Spanish‑speaking world. When they live and mix with German and Chinese immigrants and Americans and assorted other “whites,” and when they have adventures alongside these new peoples. In villages and towns that are as Mayan as they are European, in the hills and jungles and valleys of a country called Guatemala. I can see now what Asturias discovered a century ago: that “Guatemala” is a synonym for mixing.

From the foreword to Men of Maize by Miguel Ángel Asturias, to be published by Penguin Classics in September.

Héctor Tobar is a Pulitzer Prize–winning journalist, a novelist, and a professor at the University of California, Irvine. His books include Our Migrant Souls, the New York Times bestseller Deep Down Dark, and The Barbarian Nurseries.

August 15, 2024

Siding with Joy: A Conversation with Anne Serre

Photograph by Francesca Mantovani.

Anne Serre’s “That Summer,” which appears in the new Summer issue of The Paris Review, opens with an anticlimactic claim: “That summer we had decided we were past caring.” But the story that follows is packed with drama. Over the course of three pages, it chronicles interactions among four characters in a family—two of whom are institutionalized. There are two deaths. Serre’s narrator’s reflections on her family dynamics, charged and nuanced, are the main attraction. They bring to light entire dimensions of experience; when life has such a finely wrought interior, death is literally the afterthought.

“That Summer” previously appeared in French, in Au cœur d’un été tout en or, a collection of stories of similar brevity. That was not Serre’s first book of short-shorts, though her books available in English are made up of longer texts. They include three short novels—The Governesses, The Beginners, and A Leopard-Skin Hat—and The Fool and Other Moral Tales, a collection of novellas. All are translated by Mark Hutchinson, who is a longtime friend. Her untranslated works include Voyage avec Vila-Matas, which riffs on an experience of reading Serre’s Spanish contemporary, going so far as to feature a fictionalized version of Enrique Vila-Matas, and Grande tiqueté, written in a combination of French and a language Serre invented for the purpose. In her latest novel, Notre si chère vieille dame auteur, an elderly author whose death is imminent directs the process of assembling the manuscript that she has, already, left behind.

This interview was conducted primarily over email. A WhatsApp call was thwarted by “enormous storms” in the Auvergne region where, for two months out of the year, Serre lives, in a house that was also her grandparents’. As in Paris, she lives alone, something she has wanted since her adolescence. Asked if she would field a personal question, the author was encouraging. “Literature is personal,” she said.

—Jacqueline Feldman

INTERVIEWER

Are you in Auvergne right now?

ANNE SERRE

Yes, I am. As I’ve been doing every summer for a long time now, I’m spending two months of vacation here, in this region of mountains and small lakes, in the house I have inherited. Now that my whole family has passed away, the house belongs to me.

I don’t write here. I spend my vacation the same way I did when I was a child. I walk in the lanes and meadows, look at the scenery, swim in the lakes, and at night I read in bed. There are a huge number of books in the house—three generations’ worth. Basically, I do pretty much the same things I did when I was twelve or fourteen.

INTERVIEWER

Do you feel you need to be back in Paris in order to write?

SERRE

I don’t think it’s connected to the city of Paris. I just happen to live there for the rest of the year, and I live alone. I’ve always lived alone. My apartment in Paris is a bit like a big office, if you will. I work at my own pace, when I want, how I want, and however I please. For the time being, I’m alone in my house in Auvergne too. Not until August will some friends come for a visit. But the house is so filled with presences for me—my family, my father, my sisters, my grandparents, even my great-aunt and uncle who also lived here at one time—that there are too many people around for me to be able to write. Even if they’re only ghosts.

INTERVIEWER

Has it always been important to you to live alone?

SERRE

Yes, I always wanted to live alone. Even as a child or a teenager, when I thought about the future, I never saw myself getting married or living with someone as a couple. Which didn’t stop me from falling in love, of course. I like men and have been passionately in love, but I’ve always organized things so as not to live under the same roof as them. Since I never wanted children either, it wasn’t difficult.

INTERVIEWER

Does living alone lend itself to writing?

SERRE

Yes, I think that in my case living alone has been essential for writing. I’ve always been astonished that women writers I greatly admire could have a family life. Think of Nathalie Sarraute, for example, whose work is extremely demanding and required all her time—she had three daughters and was married. I always wondered how she managed it …

INTERVIEWER

In “That Summer,” many details of the family’s life are out of view. When the sisters don’t leave the island, Capri is described as being “petrified.” You have that title, in English, The Fool and Other Moral Tales, and I thought I might ask about morality. Even the first-person plural at the start of the story seems marked by a complicity, or the evasion of responsibility … Is it corrupting to be part of a family?

SERRE

Your question about “corruption” reminds me of Henry James, an author I’ve always loved, whose work is shot through with a strange feeling, never really explained, of something unspeakable you can’t quite put your finger on. There’s something on the moral plane that horrifies James (and perhaps horrified him during his childhood), but he doesn’t know quite what it is. In everything he writes, he’s trying to find it. This thing that horrified him, I think, is a form of inversion, the wrong side (but of what I don’t know) presented right side up or the other way around. It’s particularly noticeable in The Turn of the Screw. That’s where he comes closest to finding it. It’s what makes the book so fascinating, in fact.

INTERVIEWER

“I think, unfortunately, that I preferred him mad.” I wanted to ask you about this line, too, from “That Summer.” The narrator is referring to her father. What is the role of the perverse in your texts—if “perverse” is the right word?

SERRE

Most of my narrators use irony and self-deprecation, I think. It’s just the way my mind works. But I’ve certainly inherited this in large part from the English satirists and all those marvelous Irish writers from Sterne to Beckett, and also from Cervantes, Voltaire’s tales, and so on. I’ve always loved seditious fantasy and farce, enormities uttered with a smile, the narrator playing around with his role as storyteller and the tale being told. I like the detachment they allow in the face of tragedy—not to deny tragedy, but to bring out its grotesque side, since death will obliterate everything. That said, the narrator in “That Summer” is distinguished more by her candor. She likes the complex, conflicting emotions aroused by her father’s folly—and says so—no doubt because they allow her to perceive all kinds of interesting things she wouldn’t perceive in more straightforward, peaceful circumstances.

INTERVIEWER

There’s also a “slightly erotic” tinge to the father’s “joy” that can involve thinking he’s Alfred de Musset, George Sand’s lover. Erotic and family love occur together elsewhere in your oeuvre. Did you need both to form this story?

SERRE