The Paris Review's Blog, page 23

September 5, 2024

Portrait of the Philosopher as a Young Dog: Kafka’s Philosophical Investigations

Nicolas Gosse and Auguste Vinchon, Cynic philosopher with his dog (1827). Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Franz Kafka’s story “Investigations of a Dog” might be retitled “Portrait of the Philosopher as a Young Dog.” In any event, Kafka did not assign a title to the story, which he left unpublished and unfinished. It was Max Brod who named it Forschungen eines Hundes, which could also be translated as “Researches of a dog,” to give it a more academic ring. But the term investigations has its fortuitous resonances in the history of modern philosophy. The dog’s investigations belong to a great line of theoretical endeavors, like Wittgenstein’s Philosophical Investigations, with its retinue of animals, dogs included; or Husserl’s Logical Investigations, which launched his new science of consciousness, phenomenology; or Schelling’s Philosophical Investigations into the Essence of Human Freedom, even more to the point since this is how the dog’s investigations end, with the question of freedom, and the prospect of a new science of freedom. The word translated as “investigations” in these titles, Untersuchungen, is also used by Kafka’s dog, who speaks of his “hopeless” but “indispensable little investigations,” which, like so many momentous undertakings, began with the “simplest things.”

We are not in the standard Kafkian milieu of the trial but the university. The name Kafka is popularly associated with the horrors of a grotesquely impenetrable legal system, but there is another aspect to Kafka, which concerns knowledge. “Investigations of a Dog” presents a brilliant and sometimes hilarious parody of the world of knowledge production, what Jacques Lacan called “the university discourse.” And the contemporary academy might easily be qualified as Kafkaesque, with its nonsensical rankings and evaluations, market-driven imperatives, and exploding administrative ranks. But Lacan’s term was meant not so much to target the mismanagement of the modern university as to designate a broad shift in the structure of authority, a new kind of social link based on the conjunction of knowledge and power, the establishment of systems of administration operating in the name of reason and technical progress. And this is where Kafka’s dog comes in, to question this new order, to excavate the underside of its supposed neutrality, to propose another way of thinking, even, perhaps, a way out. The entry for “dog” in Gustave Flaubert’s Dictionary of Received Ideas reads: “Especially created to save its master’s life. Man’s best friend.” Kafka, a true Flaubertian, upends this cliché about canine fidelity to authority. His dog is not man’s best friend, but the truth’s; and he does not save his master’s life, but risks his own in seeking to free himself from domination and reveal the hidden forces at work in his world. Along the way of this fraught quest, some of the questions the dog will grapple with are: Can one actually be friends with the truth? What kind of dissident science might be built around it? and, Who are his comrades in this struggle?

Written in the autumn of 1922, less than two years before Kafka’s death at the age of forty, “Investigations of a Dog” was first published in 1931, in a collection edited by Max Brod, Beim Bau der Chinesischen Mauer (The Great Wall of China; lit., At the construction of the Great Wall of China). It was translated by Willa and Edwin Muir shortly afterward, in 1933; today there are six other translations in English. Speaking about the canine science of food, the dog remarks that “countless observations and essays and views on this subject have been published,” such that it “is not only beyond the comprehension of any single scholar, but of all our scholars collectively.” One is tempted to say the same about Kafka scholarship. “Investigations of a Dog,” however, was never one of Kafka’s more popular stories, and, despite the attention it has received, it is a work that I believe still remains to be discovered. Critical judgment has been mixed, sometimes reserved; it’s been called “one of the longest, most rambling, and least directed of Kafka’s short stories.” And it has also proved something of a puzzle for interpreters. No less an authority than Walter Benjamin remarked, in a letter to Theodor Adorno, that “Investigations of a Dog” was the one story he never really figured out: “I have taken the fact that you refer with such particular emphasis to ‘Aufzeichnungen eines Hundes’ [sic] as a hint. It is precisely this piece— probably the only one— that remained alien to me even while I was working on my ‘Kafka’ essay. I also know—and have even said as much to Felizitas— that I still needed to discover what it actually meant. Your comments square with this assumption.” The mistake in the title is amusing: Aufzeichnungen means “records” or “notes,” perhaps lecture notes, as if the story were a transcription of the dog’s seminar. Kafka’s dog as educator. In his correspondence with Benjamin, Adorno mentions the story in the context of discussing Kafka’s relationship to silent cinema (incidentally, it’s been suggested that “Investigations of a Dog” was partly inspired by a scene from one of Kafka’s favorite movies), and also the link between language and music, a key element of the dog story. Much of Benjamin’s commentary on Kafka concerns theology; against religious interpretations he insisted that “Kafka was a writer of parables, but he did not found a religion.” But what about a philosophy? Was Kafka the author of a new philosophy, or rather its mythologist or parabolist? Descartes famously wrote, “I advance masked.” What if Kafka advanced philosophically under a dog mask? “Investigations of a Dog” can be read as a picaresque tale of the adventures of theory, but more than that, it’s a speculative fiction-essay that lays out the conditions of philosophy in its relations to knowledge, language, community, and life. In the guise of writing about a lone canine’s attempts to come to grips with his own peculiarities and those of his world— that is, in chronicling the thinker’s dogged pursuit of his alienation, his refusal to “live in harmony with my people and accept in silence whatever disturbs the harmony”— Kafka comes closest to giving us his philosophical manifesto.

What if Kafka’s dog were an unlikely hero of theory for untheoretical times? What would it mean to philosophize with Kafka’s dog? To research like a dog?

***

“Investigations of a Dog” is one of the most accomplished of Kafka’s animal stories, along with “The Metamorphosis” (unidentified beetle-like vermin), “The Burrow” (unidentified burrowing creature, maybe a mole), and “Josephine the Singer, or the Mouse Folk” (mouse). It has a special connection to “Blumfeld, an Elderly Bachelor” (missing dog plus two celluloid bouncing balls), which is also one of the less-read stories in Kafka’s oeuvre; before “Investigations,” Kafka called “Blumfeld” his dog story. Its focus on knowledge and the academic world places it in proximity to “A Report to an Academy” (ape), whose protagonist Red Peter narrates his miraculous transformation from ape to human before a distinguished audience of scientists and academics. Yet the talking ape is an object of scientific study, a witness providing evidence, whereas the dog conducts his own inquiries and sets his research agenda; he is an investigator in his own right. Moreover, the dog disavows the scholarly world—he’s not part of the “Honored members of the Academy!” whom Red Peter addresses—in the name of another sort of theory.

The tale is narrated by the dog himself, who is never named, from the vantage point of his later years (we don’t know exactly how old he is). After some preliminary reflections on the nature of dogdom, and the present state of his work, he starts to reminisce about his life in theory, reckoning with his accomplishments and his failures, his colorful encounters and intellectual escapades. We learn of the philosopher dog’s youth, of how his curiosity and investigative instincts were first aroused by a shocking event: a concert by a troupe of musical dogs. Intrigued by this fantastical song and dance show, and especially by the musicians’ refusal to answer any of his questions—a refusal, he pointedly remarks, that contravenes canine law—the dog embarks on a quest to unravel the mysteries of the dog world. From the wondrous concert the young philosopher soon turns to the fundamental preoccupation of canine existence, namely food. Food is the subject of an overwhelming amount of scientific research, but there is one question that science is silent on: Where does food come from? “Whence does the earth procure this food?” The dog conducts a number of experiments to test the food source and probe the mysteries of nourishment. He’s ridiculed by his fellow hounds—when he asks about food, they treat him as if he’s begging for something to eat—yet they are not unmoved by his questions. The dog detects a certain disquiet in dogdom.

Later on, he investigates one of the strangest phenomena of the dog world, the so-called aerial dogs or Lufthunde. These pooches spend their days floating in the air—or at least such is the rumor, for the dog hasn’t seen them himself. They don’t labor like other dogs and are detached from the life of the community, though they claim to be engaged in important, “lofty” matters. Disdaining this self-styled superior breed as creatures that “are nothing much more than a beautiful coat of hair,” the lonesome hound wonders who his comrades might be in his theoretical endeavor. “But where, then, are my real colleagues?” The dog asks himself whether his next-door neighbor might be one of these colleagues. Though he is desperate for fellow researchers, the dog doesn’t care much for his neighbor, whom he considers to be a nuisance. On the other hand, perhaps they are actually devoted to the same cause, sharing an understanding “going deeper than mere words.” What shared understanding—secret, unspoken—unites the dog people? Are all dogs united in theory? The philosopher dog then assumes the role of cultural critic and reflects on the troubled state of dogdom and its history, melancholically concluding against the prospect of any real transformation: “Our generation is lost, it may be.”

Returning to his researches on nourishment, the investigator abandons his earlier experiments and adopts a more radical approach, one that goes against every fiber of canine being: he fasts. Fasting, he says, is “the final and most potent means of my research.” The dog dreams of the glory he will win with his daring philosophical project; instead, this new research method nearly kills him. The starving animal vomits blood, blacks out, then awakens to a radiant vision: a beautiful hunting dog is standing before him. The two enter into a cryptic dialogue, the hunting dog warning him that he must leave, the philosopher insisting to stay. Their exchange is interrupted when the hunting dog starts to sing. Or rather, a voice suddenly appears from out of nowhere, as if singing on its own accord. “It seemed to exist solely for my sake, this voice before whose sublimity the Woods fell silent.” What begins with the astonishing concert of the musical dogs ends with an uncanny voice in the forest, singing to the dog alone.

In schematic terms, the story contains six main episodes: the musical concert, experiments in food science, the aerial dogs, the neighbor, the fast, and the hunting dog. It also includes two parables: the parable of the sages, contained within the section on fasting, and the parable of the bone marrow, which presents, in cryptic form, the problem of the philosopher’s relation to the community, and reveals the philosopher’s own “monstrous” desire. The question of community runs throughout the story. However solitary his investigations may be, the dog insists that they implicate the whole of dogdom. Even further, he needs the other dogs to accomplish his theoretical aims: “I do not possess that key except in common with all the others; I cannot grasp it without their help.” What stands in the way of the realization of philosophy is the silence of the dogs, a silence that also afflicts the philosopher himself. This silence is both the greatest barrier to the dog’s investigations and their most formidable object. Canine theory turns out to be a theory of resistance to theory. The problem is ultimately one of language. The true word is missing, laments the dog, the word that could intervene in the structure of dogdom and transform it, creating a new way of life and a new solidarity. Siegfried Kracauer, in the first important commentary on “Investigations of a Dog,” highlighted the theme of the missing word as the crux of Kafka’s oeuvre: “All of Kafka’s work circles around this one insight: that we are cut off from the true word, which even Kafka himself is unable to perceive.”

The final pages summarize the results of the dog’s researches, sketching the outlines of an ambitious philosophical system that might be called, not without irony, Kafka’s “System of Science.” It consists of four disciplines. The two main ones are the science of nurture (Nahrungswissenschaft), which could also be translated as the science of nourishment or food science, and the science of music or musicology (Musikwissenschaft), which might be seen as representing the field of art and aesthetics in general—music, not literature, is the paradigmatic art in Kafka’s universe. Situated between these is a kind of transitional or bridging science, which investigates the link between the realms of life and art, or between physical nourishment and spiritual nourishment, which the dog calls the theory of incantation, “by which food is called down.” This consists of the rituals and symbolic actions performed by dogs for the procurement of food; in these practices of begging and supplication we may find the beginnings of a theory of institutions. Between vital necessity and artistic creativity, there lies the institution. All institutions are, at bottom, the songs we sing, and the rules for singing such songs, to obtain whatever it is we want, our desired “food.” Finally, there is an “ultimate science” (einer allerletzten Wissenschaft), the science of freedom, a prize “higher than everything else.” This is how the story ends, with the dog declaring that freedom “as is possible today is a wretched business,” yet “nevertheless a possession.” If the main canine sciences mirror the classical division between the servile arts and the liberal arts, artes mechanicae and artes liberales, the place of the science of freedom is not immediately clear. In the Dog University there is a School of Agriculture and a School of Music, and there is also a Faculty of Law, dealing in the incantatory arts. Where does the science of freedom fit into this? Is it a separate discipline, with its own object and specialized knowledge? Is it the queen of the sciences, the pinnacle of the system, or is it rather a maladjusted science, without a prescribed place in the whole? Kafka is usually considered an unsystematic or even anti-systematic author, a poet of the fragmentary and the unfinished who warns against the danger of totalitarian systems. So, what should we make of the dog’s philosophical system?

Although Kafka left “Investigations of a Dog” unfinished, the story gives the impression of being more or less whole. What is lacking, however, is an elaboration of the system. To take up things where the dog left off, to develop the conceptual architecture of the Cynological System of Science, means to address the following questions of Kafkian philosophy, which reflect the four-fold division of the system: What nourishes us? What is art? How does incantation structure our relation to others and the world? What is freedom?

If we put the story in the context of its times, Europe in the twenties, the dog’s aspirations for a new science resonate with the two new disciplines that emerged at the beginning of the twentieth century, one dealing with consciousness, the other with the unconscious: Husserl’s phenomenology and Freud’s psychoanalysis. Both addressed, in very different ways, the crisis of European sciences and civilization, at a time when talk of the decline of the West, borne out by the devastation of World War I, was at its height—this acute sense of crisis is echoed in the dog’s lament of his being a lost generation. In the case of phenomenology, Husserl’s new science took the form of a renewal of the ideal of philosophy as the queen of the sciences, capable of providing a rational foundation for the pursuit of truth, through its explication of the essential structures of consciousness. Psychoanalysis, on the other hand, constituted a new field, without a clearly defined place in the existing order of knowledge, studying and treating the pathologies of psychic life. Freud showed how these psychopathologies were rooted in subjectivity—a person’s fantasies and drives and singular history—but a subjectivity torn and divided against itself. His investigations were dedicated to uncovering the structures of the unconscious, that which resists the light of truth and makes a hole in knowledge. Mladen Dolar has argued that the dog’s new science is none other than psychoanalysis.

In 1917 Franz Rosenzweig published a two-page manuscript that he had discovered a few years earlier at the Prussian State Library in Berlin, while researching what would become his book Hegel and the State. He gave it the title “The Oldest System-Program of German Idealism.” Though the handwriting was undeniably Hegel’s, Rosenzweig thought the text’s tone and content indicated that it had been originally written by Schelling and later copied by Hegel, the facsimile being the only surviving version of the text. Since then, the fragment’s authorship has been vigorously disputed, with different scholars attributing it to Hegel, Schelling, and Hölderlin (it’s even been argued that the text was retroactively penned by Nietzsche). One of the slogans from the heyday of poststructuralist criticism was “What does it matter who’s speaking?” and this seems to apply to “The Oldest System-Program”: perhaps the dispute over authorship belies the fact that it’s Spirit itself that’s speaking. The short manifesto lays out a radical program encompassing ethics, metaphysics, nature, politics, history, religion, and art, culminating in a call for a new “mythology of reason” that would unite theory and practice and make of philosophy a living, popular reality. This is a system for the realization of freedom—for “only that which is the object of freedom is called idea”—through its intimate connection with truth and beauty. There is no evidence, as far as I’m aware, that Kafka knew this text, but the dog’s system-building aspirations, as well as Kafka’s own forays into writing a new mythology (by twisting the old myths, from Odysseus and Abraham to the Tower of Babel and the Chinese Emperor), ought to be understood in light of this odd philosophical fragment, a kind of vanishing Ur-text of German Idealism. What if Kafka’s dog were a fellow traveler of the German Idealists, even their most faithful companion: Kant, Fichte, Hegel, Hölderlin, Schelling, and a woolly, unnamed hound? Of course, 1917 was also the year of the October Revolution, which brought with it the ideal of a communist science dedicated to a total renovation of human subjectivity, the creation of a New Man. Nikolai Zabolotsky, one of the original members of the Russian avant-garde collective Oberiu (Union of Real Art), composed an unorthodox paean to this new society titled “The Mad Wolf”; it was written in 1931, the same year as the first publication of “Investigations of a Dog.” The poem depicts the founding figure of communist science as a visionary animal—not a dog this time but a wolf. “We are building a new forest … utterly wretched only yesterday,” declares the leader of the student wolves, echoing a verse of “The Internationale”: “We will build a new world that is ours.” This is also the dream of Kafka’s dog, to revolutionize canine existence, and, one might say, to usher in the birth of a New Dog: “The roof of this wretched life, of which you say so many hard things, will burst open, and all of us, shoulder to shoulder, will ascend into the lofty realm of freedom.”

From How to Research Like a Dog: Kafka’s New Science, to be published by the MIT Press this October.

Aaron Schuster is a philosopher and writer. He is the author of The Trouble with Pleasure: Deleuze and Psychoanalysis.September 4, 2024

Javier Fuentes Will Be the Paris Review Visiting Professor at the Bard Prison Initiative

Javier Fuentes in the offices of The Paris Review.

Last year, The Paris Review joined forces with the Bard Prison Initiative, which for twenty-five years has provided a full-time, tuition-free, degree-granting liberal arts education to students in unconventional settings, including several Upstate New York prisons and BPI’s microcolleges in New York City, one of which is located at the Brooklyn Public Library. In March, we announced the Paris Review Visiting Professorship—a position for a creative writer to teach the literature that has inspired them to BPI students—and were heartened to receive a great number of nominations from the community. We are now delighted to announce that the inaugural Paris Review Visiting Professor is Javier Fuentes, who will be teaching three semester-long courses at NYSDOC Eastern Correctional Facility in Napanoch, New York.

Fuentes, who was born in Madrid, is the author of Countries of Origin, a novel about an undocumented pastry chef who is forced to leave New York and start life over in Spain—and his love affair with a young man named Jacobo, whom he meets on the plane. Fuentes’s first course, called Physical and Psychological Spaces in Literature, will explore the way time and place structure narrative; his syllabus includes Gaston Bachelard’s The Poetics of Space, E. M. Forster’s Howards End, and The Yellow House by Sarah M. Broom. Also Kafka’s The Metamorphosis—“Not a book that you usually think of in terms of space,” Fuentes said. “But if you read it closely, the house that Gregor finds himself in and the objects around him really are the main characters.” Class starts on September 5 and will meet twice a week. We want to congratulate Javi, and to wish the best of luck to him and his students as they embark on the new semester!

Javier Fuentes Will Be the Paris Review Visiting Professor at Bard Prison Initiative

Last year, The Paris Review joined forces with the Bard Prison Initiative, which for twenty-five years has provided a full-time, tuition-free, degree-granting liberal arts education to students in unconventional settings, including several Upstate New York prisons and BPI’s microcolleges in New York City, one of which is in a Brooklyn Public Library. In March, we announced the Paris Review Visiting Professorship—a position for a creative writer to teach the literature that has inspired them to BPI students—and were heartened to receive a great number of nominations from the community. We are now delighted to announce that the inaugural Paris Review Visiting Professor is Javier Fuentes, who will be teaching three semester-long courses at NYSDOC Eastern Correctional Facility in Napanoch, New York.

Fuentes, who was born in Madrid, is the author of Countries of Origin, a novel about an undocumented pastry chef who is forced to leave New York and start life over in Spain—and his love affair with a young man named Jacobo, whom he meets on the plane. Fuentes’s first course, called “Physical and Psychological Spaces in Literature,” will explore the way time and place structure narrative; his syllabus includes Gaston Bachelard’s The Poetics of Space, E. M. Forster’s Howards End, and The Yellow House by Sarah M. Broom. Also Kafka’s The Metamorphosis—“Not a book that you usually think of in terms of space,” Fuentes said. “But if you read it closely, the house that Gregor finds himself in and the objects around him really are the main characters.” Class starts on September 5 and will meet twice a week. We want to congratulate Javi, and to wish the best of luck to him and his students as they embark on the new semester!

Against Rereading

Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. Licensed under CCO 4.0.

I was ten years old when I forgot how to sleep. I’d get into bed and focus very hard on trying to switch my conscious mind off, but the effort was self-defeating. I didn’t like spending so many hours alone, so I started waking my older sister up in the middle of the night to play the Game of Life, a board game in which you traverse a one-way highway leading from graduation to retirement in a tiny plastic car, amassing capital as you go. My sister enjoyed the game, too, but didn’t want to be woken up at 1 A.M. to play it. The solution my parents came up with was to allow me to read with the lights on for as long as I wanted. I didn’t like reading, at the time, but I pretended I did, to receive praise, like my sisters, who were known as “voracious readers.”

My sister, who was fourteen, had just finished reading a novel called The Power of One by a South African Australian author named Bryce Courtenay. I told my sister that I wanted to read this book. She said it was not a good choice. The book was for adults. I was too young. I wouldn’t get it. That night, I took the book upstairs with me, without telling my sister, and started reading. This is what I remember. There was a boy named Peekay. He lived in South Africa. He was sent to a boarding school somewhere in the desert where he was bullied. He met a Zulu man who taught him how to fight back. One evening, the man was beaten to death by a white prison guard. He battered the man’s face with a blunt object and then penetrated him with that same object until he hemorrhaged to death. I didn’t know what the word hemorrhaged meant. I was mostly ignorant of the political context within which the murder took place. I lay in bed trying to figure it all out and by the time I came close to finishing The Power of One, I felt like I had been through some major ordeal and come out the other side a new person.

I didn’t want the novel to end. I worried, as I approached the final pages, that I was going to lose everything I had experienced while reading it. I was anxious that, without The Power of One, my life would return to how it was before. One obvious solution was to immediately reread the novel and relive it all over. But there was something about rereading The Power of One that struck me as wrong or even perverse. I intuited that rereading this book would in some way ruin what had made the first time so profound and transformative. To my ten-year-old mind, reading the book once was a sign of love and reverence for the life force that seemed to animate its pages. I thought I had discovered how real reading worked: once, intensely, and then never again.

It was only years later, when I began studying literature, that I found out I had it backward. The correct and virtuous way to read, according to those who knew about reading and writing, was to reread. Rereading was that which separated the real reader from the average book consumer. Vladimir Nabokov, in his Lectures on Literature, said “a good reader, a major reader, an active and creative reader is a rereader.” On the first reading, you form vague impressions of the action based on broad and subjective intuitions. You skip sentences, miss details, and stumble forward through the plot in passive expectation. When rereading, you have time, according to Nabokov, to “notice and fondle” the particularities of the world that an author has rendered in words, like the texture of Gregor Samsa’s shell or the hue of Emma Bovary’s eyes.

As a student, I came to appreciate such granularity. Going over a text many times allowed me to fine-tune my initial intuitive judgments into something more comprehensive. There was an intellectual satisfaction in this, but I also felt, quietly, that rereading was not really reading. There was an immediacy, intensity, and complete surrender involved in the initial experience that could never be repeated and was sometimes even diminished on the second pass. Louise Glück wrote,“We look at the world once, in childhood. / The rest is memory.” I felt the same about reading. I still feel like this. And, to this day, when I read something that functions as a hinge in my life—a book that rearranges me internally—I won’t reread it. The Neapolitan Novels I won’t read again. Nor Swann’s Way. Nor 2666. And several others that I won’t mention because it’s embarrassing. After all these years, I still haven’t reread The Power of One. (It’s possible that if I did go back and reread The Power of One, I wouldn’t find the murder scene. Did I make it up entirely? Am I confusing it with another book or movie?)

This disinclination to reread the books I treasure alienates me not just from Nabokov, but from a vast pro-rereading discourse espoused by geniuses who regard rereading as the literary activity par excellence. Roland Barthes, for instance, proposed that rereading is necessary if we are to realize the true goal of literature, which, in his view, is to make the reader “no longer a consumer, but a producer of the text.” When we reread, we discover how a text can multiply in its variety and its plurality. Rereading offers something beyond a more detailed comprehension of the text: it is, Barthes claims, “an operation contrary to the commercial and ideological habits of our society, which would have us ‘throw away’ the story once it has been consumed (‘devoured’).” I’m not so sure.

If we take Barthes’s argument to its limit, we can imagine an ideal literary culture in which there is only one book and a community of avid readers returning to it over and over, unfurling its infinite field of potential in ever-more-elaborate interpretations. It reminds me of the Orthodox synagogue I attended growing up, where each year, sometime in October, the old men would finish reading the final portion of the Torah—with Moses standing on the mountain overlooking the Promised Land—and then start again at the Beginning. At the time, this hardly felt like “an operation contrary to the commercial and ideological habits of our society.” More a timeworn method for reaffirming tradition and safeguarding community. It could also get boring.

Rereading is, when you think about it in another light, a basically conservative pursuit: it is what makes canon formation possible, and canons are what keep the base structure of a tradition or a culture intact. This is why Harold Bloom was a rereading fanatic, and why rereading evangelists are always rereading the classics. One time through, for the great books, is not enough. They are “revisiting Proust” or “returning to Moby-Dick” or “dipping back into” Paradise Lost, as the English writer William Hazlitt does in his 1819 essay “On Reading Old Books.” He begins this essay by declaiming: “I hate to read new books” and then suggests that reading them is for women, who “judge of books as they do of fashions or complexions, which are admired only ‘in their newest gloss.’ ” Hazlitt, a man, has “more confidence in the dead than the living.” He returns to Milton, over and over, because he believes that this will inure him against the laziness, vapidness, and shallowness of modern culture.

This principle—that rereading might be a balm to society’s cultural decline—persists among contemporary rereaders, too. Within the wide array of pro-rereading literature—essays about rereading, memoirs about rereading, polemics about rereading—rereading is a kind of sacred discipline that is slowly being forgotten due to a surfeit of disciplined intellectualism. Elaine Scarry, for instance, laments in a recent Paris Review interview how students “these days” are no longer required to subject themselves to “Olympic feats of reading.” And by reading, she often means rereading; she says, in the same interview, that she is a slow reader but nevertheless, she persists. “It takes me many, many hours even to reread a book,” she says, but she does so anyway, to feel closer to those historical geniuses, like Newton, Hobbes, and Oppenheimer, who built the bomb and could also “recite passages of Proust verbatim.” Rereading, thus conceived, begins to sound a bit like a punishing self-improvement regime. I can imagine a life coach promoting rereading as part of a lifestyle package, along with nootropic supplements. “In this age of algorithmically powered novelty,” the Instagram ad might say, “reclaim your attention and build wisdom by rereading the Western Canon.”

In Vivian Gornick’s book-length meditation on the subject, Unfinished Business: Notes of a Chronic Re-reader, she describes returning to Sons and Lovers across the decades. In her teens, she sees herself in Miriam, the girl who only wants to be desired, then later as Clara, who has passions but is afraid of following them. In her mid-thirties, Gornick finds herself in Paul, the desiring seducer. And finally, when reading it again in her “advanced maturity,” she realizes that she has been reading the book wrong all along. The “richest meaning” of the text is not that sexual adventure is the central experience of life, as she had once imagined, but the opposite: sex is false liberation when pursued without constraint. For Gornick, the goodness of rereading is almost Aristotelian: she progresses from primitive ignorance toward a “richest meaning,” as if guided by a hermeneutic telos. And yet I find myself wanting to argue that her first interpretations of Sons and Lovers were just as rich and true as the latter ones, and in fact, perhaps by rereading and by all this painstaking reconsideration she has lost access to that specific type of youthful wisdom and intensity we bring to bear when we read something the first time.

Though great writers hold rereading in highest esteem, the most committed rereaders are those who are just learning how to read, i.e., toddlers. In “Beyond the Pleasure Principle,” Freud hypothesized that the toddler’s insistence on rereading derives from the infantile belief that pleasurable experiences can be repeated without loss: “he will remorselessly stipulate that the repetition shall be an identical one and will correct any alterations of which the narrator may be guilty.” Weshould grow out of this, Freud says, when we learn that “novelty is always the condition of enjoyment” and that the impression made by a first cannot be repeated and may ruin the once-loved story altogether. As Barthes admits, “To repeat excessively is to enter into loss.” (This seemingly self-contradictory quote can be found in “The Pleasure of the Text,” in which Barthes quotes also quotes Freud: “In the adult, novelty always constitutes the condition for orgasm.” I’ll return to this.)

Is the compulsion to reread a regression to this infantile state? A denial of maturation? Margaret Atwood suggests that it might be when she compares it to “thumb-sucking” and “hot-water bottles”; she admits that she does rereads only for “comfort, familiarity, the recurrence of the expected.” This also might be the reason why so much rereading apologia is written by those for whom the glow of youth has long passed by, as Hazlitt’s had when he wrote his essay. He admits that at least part of his enthusiasm for rereading familiar classics is a yearning to revisit “the scenes of early youth” in the hope that “may breathe fresh life into me, and that I may live that birthday of thought and romantic pleasure over again.” Like the loveless narrator in Dostoyevsky’s short story “White Nights,” he seeks to return to places where he was once happy, to try and shape the present in the image of the irretrievable past. It’s futile. He can’t recapture that first pleasure, and in fact, through repeating, ends up ruining reading more generally. “Books have in a great measure lost their power over me; nor can I revive the same interest in them as formerly,” he admits. He might have been better off reading something new, for a change, to help pull him out of his depressive reveries. Falling in love with a new book might be one of the adventures left to available to us as the flesh weakens—the spirit, hopefully, remains willing.

In the end, maybe the crucial difference between those who read once and those who reread is an attitude toward time, or more precisely, death. The most obvious argument against rereading is, of course, that there just isn’t enough time. It makes no sense to luxuriate in Flaubert’s physiognomic details over and over again, unless you think you’re going to live forever. For those who do not reread, a book is like a little life. When it ends, it dies—or it lives on, imperfectly and embellished, in your memories. There is a sense of loss in this death, but also pleasure. Or as the French might put it, la petite mort.

Yet, to rereaders, this might sound like nonsense. Why constrain a book to a mortal pulse when it could live forever, revived over and over through repeated readings? Rereading, they might argue, is a miracle, because it brings a book back to life. We see the characters breathe again. We see a world end and then be reborn. We experience the romance and seduction of a scene on repeat, unlike in life, where you do it once and then it’s over. In a life that marches relentlessly forward toward its end, rereading can seem like a weapon against the inevitable. But, of course, it isn’t. The same fate awaits us all, whether you’ve reread Proust or not.

Oscar Schwartz is a writer and journalist. He lives in Melbourne, Australia.

September 3, 2024

The Black Madonna

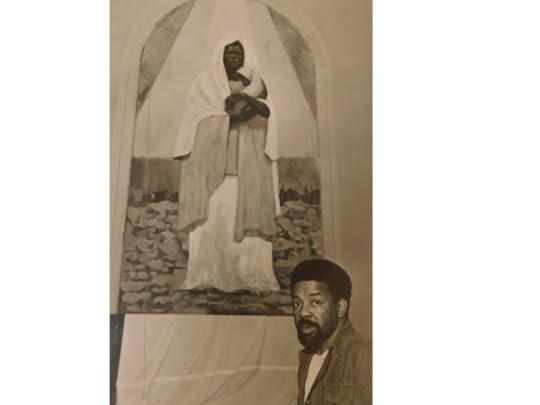

Glanton Dowdell. Photograph from the Albert B. Cleage Jr. Papers, courtesy of Kristin Cleage.

In 1959, at sixteen, Rose Percita Brooks had two choices: the navy or the nunnery. The way her grandmother Rosie beat her for kissing a boy on a couch in her home made the girl want to run into a convent. At least there she would be far from the old woman’s wrath. Whatever inspired Rosie’s cruel beatings may have been a holdover from an ancestor’s pain during slavery times, some ghost haunting the old woman. Rosie was not yet born when slavery existed in Memphis, but she would always moan joyfully in church, as though she had witnessed the first Juneteenth. It was clear when the spirit possessed her. She grunted more loudly than anyone else. Oh, that’s Grandma, Rose thought. She’s happy now. She’s got the Holy Spirit.

It was Rose’s grandfather who told his wife that the girl was in the living room with a stranger. They had flirted from opposite ends of the sofa until Rose accepted the boy’s slow departing kiss. That same evening, Rosie surprised the girl when she was changing for bed. As she recoiled from her grandmother’s blows, Rose thought of herself as an abused housewife, so wholly bound to her captor that she started to feel indistinguishable from Rosie. Would she ever escape her grandmother’s orbit? Rose bathed the woman, laid out her church clothes, and had nearly the same damn name.

“What are you doing with that man?” Rosie demanded. The worst thing the girl could do was lift her arms to protect her face. Rosie’s force increased each time the girl tried to shield herself from the blows.

The old woman’s rage pushed Rose Percita away. Her dreams of Howard University and Tennessee State receded. In Nashville, the navy recruited Rose before the sisterhood could. She gave them her loyalty and hoped they would be gentler than the marine corps or air force. Boot camp and a nearly fatal swimming test were her first obstacles. She was posted at a naval station in Arlington, Virginia, as a stringer photographer for a navy paper. Over the next four years, few aspects of life on the base escaped her notice. She and her sole colleague, a white man from North Carolina, ran the publishing operation—“a cute little thing up on a hill,” Rose would later call it, a world of their own.

The delight of developing film and watching outlines take form on the photo paper kept Rose’s mind active.

Clubs for noncommissioned officers and enlisted men adjoined the photo lab. One captain, a surgeon at Walter Reed Army Medical Center, charmed Rose. He would not let the usual rites of courtship stand in his way, however, and so he tied her up and “took it.” It was her first time. Rose could not hide her “little watermelon” for long. Her honorable discharge in 1963 stranded her again, as a twenty-year-old. She was an expecting mother with no income and no roof. One of Rosie’s daughters, the girl’s aunt, lived in Detroit and agreed to take her in. The aunt was just as mean as Rosie. Rose forgave it but could not live with it, and she fled to the home of her uncle. She then met and married a kind man, naming her son after him: Bernard Waldon, Jr. They called the baby boy Barney.

Rose Waldon. Photograph from the Albert B. Cleage Jr. Papers, courtesy of Kristin Cleage.

***

By 1967, Rose Waldon had been in Detroit for a few years, but she still could not afford to buy herself a washing machine and dryer. She would often take her three-year-old son to the laundromat with her. A man approached them one day by the laundromat entrance as they were walking in. Was he some kook? What did he want? The man introduced himself as the assistant at an artist’s gallery. He made a claim that Rose would start to hear more often in the North: he told her that she had a memorable face.

It was true. Her jawline was sharp and her cheeks reflected varied gradations of light. Each of her dimples was a shallow depression. The assistant asked Rose if she would like to model for a mural of a Black Madonna and child at Reverend Albert Cleage Jr.’s Central United Church of Christ. She did not know what the church was or why this man would think a mother with her child at a laundromat would accept his invitation, but when he explained what the church was about—that it envisioned self-determination for black people everywhere—she said, “Why yes, I would be honored to try that.”

Rose and the artist Glanton Dowdell developed an easy rapport during the first interview at his studio, the Easel Gallery. He was quite handsome with that beard, those wide eyes, and the baby-faced pucker to his lips.

He asked her where she lived.

Not far from the gallery.

Had she done any modeling previously?

She had not.

Well, she might consider it.

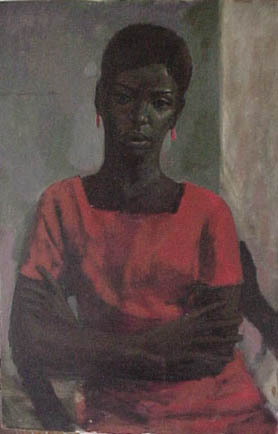

Glanton had her sit in the back of the studio as he drew a portrait study in charcoal. The oils came later. Rose was asked to find a beautiful outfit. She had a designer weave a pretty caftan that made it appear as though she moved like water over rocks. Some of their evening sessions were brief, with not much accomplished, Rose thought. But on Glanton’s canvas, she took on a new form. Her face was looking like the sculpted clay busts of Modernist black artists—William Ellsworth Artis’s Head of an African American Woman (1939) or Sargent Claude Johnson’s Chester (1931). The collaboration between the artist and his subject took one month. In the final image, Glanton captured not only some semblance of Rose but also of his earliest memories of growing up in Black Bottom, the poor enclave of blacks and immigrants that had once existed on Detroit’s east side, where the first sights he remembered were the brown legs, worn shoes, and swishing skirts of his mother and grandmother. Those women had “hummed, chattered, and laughed,” alchemizing Glanton’s hunger and want into something more bearable.

Glanton’s Black Madonna was too stocky to be a replica of Rose alone, and when she later walked into Central Church to view this woman who was herself and not-herself, she would observe her dark face on a woman with a “happy” body. It was hard to say who the original woman was or where the artist’s influence began. Was the shawl over the Madonna’s head what Glanton would later describe in his memoir as his own grandmother Annie’s “thick iron gray hair … over a deep, brown face”? Were her lips drawn tight because of Annie’s “awesome quietness” and her aversion to idle chatter? If Annie was in the painting, too, it was because the stories she had told Glanton when he was a child were, the artist wrote, “meant to define me to myself.”

Was Rose looking at herself, or at the mother figure that the women in her own family wished they could have been? Was this what she would look like in her thirties or forties, or was this the person she must try to become? When Rose first saw the Black Madonna, she began to cry, for the first time of many throughout that day. She understood at once the pride that the Muslims of Elijah Muhammad’s Nation must have felt when they grew their own food, as they were known to do in states across the South and Midwest, including in Michigan. The mural brought to Rose’s mind the landscape of a farm. The portrait had the power to sustain.

Rose could not see the future, but if she could have, she would have seen how the hard-jawed Madonna exhumed black people’s memories of their mothers, grandmothers, and other ancestral spirits. She would make people feel that they had seen someone like her before. The Black Madonna had the difficult task ahead of her of reminding black people that they could be united in a single image or purpose that reflected many conflicting selves. She was a divine archetype and an individual unlike anyone else. For all her poise and stillness, the Black Madonna was not static. She looked out, and in her eyes were glints of recognition.

Photograph from the Albert B. Cleage Jr. Papers, courtesy of Kristin Cleage.

***

Throughout history, Black Madonnas from Europe to Asia have usually been understood as alternatives to the norm. In Poland, an ancient Black Madonna icon housed at a monastery in Czestochowa became a beloved symbol of national independence and resistance against invaders. The original icon of Our Lady of Kazan in western Russia was a foot-tall wood painting adorned by admirers with precious stones and said to have inspired miracles and armies. Before the Crusades, the Black Madonnas of the Byzantine Empire were revered outside of the Roman church. The materials that Black Madonna statues were made from—meteoric stone; the wood of oaks, cedars, and fruit trees—were as diverse as the guises she was thought to have taken in various mythic traditions: Isis, Demeter, Saint Mary of Egypt, the queen of Sheba, the bride in the Song of Songs.

The mystery of the Black Madonna’s color had perplexed historians and priests for centuries. Had she been blackened by candle soot? Was it aged wood or paint? Was she darkened by the solar radiance of her love? Stained by soil after a burial, to hide her from Muslims during the Crusades? Few seemed to believe that her blackness made sense, despite her popularity in many parts of the world and the tendency of people to create art in their own image.

Years after Glanton Dowdell painted his mural, some New Age astrologers, spiritually minded feminists, and psychoanalysts inspired by the theories of Carl Jung would regard the Black Madonna as the archetype that best embodied the Aquarian age (though none of these people seemed to know about Glanton’s painting). The Age of Aquarius would be defined by the destruction of dangerous ideologies that threatened the Black Madonna, who for some became the symbol of a fertile, healthy earth. For different Utopian thinkers from the sixties on, the Black Madonna was understood as an enemy of capitalism, militarism, nuclearism, environmental degradation, white Christianity, and white supremacy. Her emergence from the black collective unconscious, when Glanton awakened her from a long dormancy with his brush, sounded the bells of kairos—the appointed time for what Jung in The Undiscovered Self (1958) called a “metamorphosis of the gods.”

caption tk

From The Black Utopians: Searching for Paradise and the Promised Land in America, to be published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux this October.

Aaron Robertson is a writer, an editor, and a translator of Italian literature. His translation of Igiaba Scego’s Beyond Babylon was short-listed for the 2020 PEN Translation Prize and the National Translation Award. His work has appeared in the New York Times, The Nation, n+1, The Point, and Literary Hub, among other publications.

August 30, 2024

Toys in the TV

There is another kind of television. It’s not quite live action, nor purely animated. It exists in three-dimensional space, yet people, in their conventional forms, are absent, and the stories and characters don’t fit neatly into our practical world. It makes sense that we find this kind of television in the children’s category, because that’s where we leave most irrational things.

Toys, especially ones designed for make-believe play, occupy a similar middle ground. Toys are real objects that you can touch, but they don’t work in the way nontoys work. You have a toy elephant, but you don’t have an elephant. You have a toy vacuum, but not a vacuum. If toys are soft, plush, rounded, and malleable, with holes and faulty parts, so are the worlds we create for them. We might watch this happen on TV.

Costume

The role of logic in the world of Teletubbies is unclear. Sometimes, the show seems overly dedicated to the principles that structure real life. Po learns that she cannot slide up the slide, because slides are for going down. Dipsy walks away from home, and therefore must walk back again. At other times, these rules are abandoned. Tinky Winky is able to fit a piece of Tubby Toast, a cow-print top hat, a large orange ball, and a scooter all in his small red purse.

Each episode of Teletubbies isolates a very simple action—one of the basic units of everyday life. The Tubbies look in the mirror, hold hands, or take turns sitting in a chair. There are four of them, the eight-foot-tall creatures, each with a unique color, signature accessory, and slightly differentiated personality. Actions sometimes produce consequences, and conflict (which itself is rare) will only sometimes find a meaningful resolution. When the Teletubbies can’t decide what to eat, for example, they go outside.

It’s beautiful here in Tubbyland. Like a normal field in the English countryside, but special. Decorated with plastic flowers and dotted with bunnies, the terrain is enhanced with small ski mogul–like hills. The Tubbies live in a grass dome that emerges from a depression in the landscape. Its interior is decorated in a futuristic style, with a toaster, a custard machine, and a control center fashioned with levers and buttons that have unspecified functions. The sky, which happens to also be our sky, is partly to mostly cloudy, depending on the day. If you look far enough into the distance, the grass becomes more muted and brown, where Tubbyland merges into ordinary farms.

Before long, the magical windmill spins, indicating that it’s time to watch TV on your stomach. Each episode, one of the Teletubbies is selected to have a short live-action segment broadcast on their stomach-screen. This is a great privilege and a curse: the honor of featuring the video, but the challenge of having to watch it upside down.

Each of these TV clips shows real-life children completing normal activities. Drawing cacti, digging for potatoes, having a barbecue. After the clip ends, the Teletubbies yell “Again! Again!” and the clip repeats. No, the recording isn’t messed up—the Teletubbies, like children, are naturally drawn to repetition, unconcerned that it disrupts the flow of the episode.

The Teletubbies like to watch us, and we like to watch the Teletubbies. Does it matter that somewhere, deep inside the Tubby, is a human actor (if you can call it that)? On the back of each Tubby is a raised piece of fabric covering up the closure of the suit. The separation between the headpiece and the body is equally obvious. These details beg to be edited out or smoothed. Yet these disruptions don’t point to the human inside the Teletubby as much as they suggest a different comparison: a toy.

The Teletubby suit itself—lumpy, soft, bulbous—withstands its human interior. It is more toy than human. This is intentional: the four-foot-long Flemish Giant rabbits were selected to make the Teletubbies appear comparatively toy-size. Yes, Teletubbies look like aliens, or babies, but they mostly look like toys.

Like all toys strewn across a playroom floor, the Teletubbies really do exist. There, in the field, being filmed in front of the camera. The set is real—so real that it was intentionally flooded by its owner after an influx of fans trespassed onto her cattle fields in an attempt to reach Tubbyland.

And like toys, the Teletubbies are also not real, not distinctly alive, with no place in our physical, human world. The Teletubbies, as we see them, are more than a sum of their parts (the actor, the suit). The hybrid Teletubby mirrors the process by which we animate toys through our imagination—giving them life and using them to test out what things are supposed to do and mean. Hence the logical holes poking through Tubbyland. This is all an experiment—these are just toys. Rules will be picked up only to be put down again. And again, and again.

Clay

Pingu, the penguin protagonist of his namesake series, lives his life through pure, raw emotion. He is a very bad penguin. Blind to consequences, he acts impulsively, triggering tears, wounds, and scoldings. His major irritants are typical of any young boy: a younger sister who gets too much attention, rules, bullies, the seaweed he has to finish before leaving the table. What is not typical of Pingu is that he’s made of clay.

Specifically: soft, matte plasticine with the texture of fondant. Few things are made of clay, but at the same time, clay can be made into anything. In Pingu, this means: tables, chairs, planks of wood, igloos, mailboxes, sleds, red balls, popsicles, lollipops, fish, fishing poles, hats, accordions, barrels, baskets, pillows, popcorn, packages, straws, stilts. A world made from clay is not realistic (everything has rounded edges), but in many ways, it is preferable.

In the South Pole dollhouse arena where Pingu’s dramas unfold, things stretch, bend, spread. The world we live in doesn’t really move like clay, but when it does, here on the screen, it moves better. It feels good to hold clay, to squeeze it, roll it, flatten it out, break it apart. It feels good to watch clay move like this, as if my hands were inside the screen. Clay needs human touch to warm up before it changes shape. Pingu needs our warm hands.

Meanwhile the characters speak in Penguinese, an uninterpretable language that sounds like talking but doesn’t say any words. Only the sensory qualities of language remain. It’s surprising how well this works: full exchanges decipherable only through tone and gesture.

It turns out that clay is perfectly suited for slapstick comedy. Pingu sleds down the hill so fast that he crashes inside a snowman—we watch the base of the snowman stretch as he tries to push himself out. He flips over his fishing hole like a Slinky, catching his friend Robby the Seal stealing his fish behind him. Luring the seal out of the ice hole with a piece of seaweed tied to a string, Pingu chases him by rolling his entire body into a perfectly cylindrical ball. When Pingu falls onto the ground, he flattens on impact.

Animators call the freedom of movement in claymation “squash and stretch.” Characters change shape as they move. This kind of stuff happens in cartoons all the time, but the effect seems more extreme in three dimensions—in the clay that we can feel in our hands.

Other fictional worlds limit their characters’ expression to movement of the eyes, mouth, and limbs, but Pingu characters emote with their whole bodies. When Pingu is surprised or overwhelmed, his body melts into a puddle. When he wants to intimidate someone, his torso stretches and his shoulders expand. His signature expression, “Noot Noot,” erupts from his beak as it stretches into the shape of a trumpet, expressing a range of extreme emotions from excitement to anger.

Though exaggerated, the reactive morphings of Pingu’s body never feel unrealistic. Emotion has a tendency to manifest physically. Emotion is a kind of exaggeration in itself—it stretches, it shrinks, it melts into the ground.

Pingu’s mischief brings consequences, then tears. Fat, white, opaque tears that rest for a moment on his face. Again: sadness is physical. Clay is soft, but not because it is gentle. Clay has a quality of softness that promises flexibility. The opportunity to be something, and then be something else. In the next few frames, tears roll away. Pingu bounces back.

Hands

Cookie Monster was discovered, in a way, on a game-show segment in the first season of Sesame Street, called “The Mr. and Mrs. Game.” A blue monster and his wife appear on a game show. His voice sounds like a used car salesman’s. When they win, they are offered the choice between ten thousand dollars, a new house, a three-week vacation in Hawaii, or a cookie. He chooses a cookie, and there’s no coming back from that.

Cookie Monster would not consider his timeless bit a bit. After all, the only way Cookie Monster can understand his world (the number three, the moon, the word there) is by thinking about it through cookies (three cookies, it’s a good thing the moon is not a cookie, there are cookies there). To the librarian’s dismay, he is unable to request a book without also requesting a box of cookies. His letter to Santa says it all: two dozen coconut macaroons, a pound and a half of “figgy newtons,” four dozen oatmeal cookies, banana cookies, chocolate-covered-marshmallow-with-jelly-inside cookies. He has to stop there because he has become so hungry he has eaten his pencil.

It takes two to “animate” Cookie Monster, who is a live hand puppet, unlike a rod puppet (Elmo) or a wearable puppet (Big Bird, Snuffy). Cookie Monster is also referred to as a bag puppet, which seems right—he is basically just a giant bag. One puppeteer uses both of their hands, one in Cookie Monster’s head and the other in the left arm, and another puppeteer controls his right arm. In review: Cookie Monster’s hands are human hands, his arms are arms, but then his head is also a hand. “The hand speaks to the brain as surely as the brain speaks to the hand,” you can read in a book called The Hand.

Puppets are fidgety. This has a physical explanation, because a human arm and hand have more mobility than a torso and head. It’s also a coping mechanism, making up for the absent faculties of facial expression and body language.

Cookie Monster flaps all over the place, repeatedly showing us the dark hole that is his mouth. No one’s face moves like that, which makes sense because what’s moving is actually a hand. Cookie Monster is grabby, catchy, punchy. It’s not a coincidence that these adjectives also describe actions completed by a hand.

In another children’s show, Oobi, the hand-mouth relationship is interrogated. Instead of placing their hands inside the puppets, the puppeteers’ hands function as the puppets themselves, with the sole addition of a pair of glass eyes. Picture a puppet, but naked. These puppets can do all the typical kids’ show things—play, explore, navigate simple conflict. They can also do all the typical puppet stuff: talk, look around, move up and down. The thumb sometimes becomes an arm, or a hand, scratching the side of the head in confusion. The mouth of the characters takes a break from being a mouth to become a hand and carry something—say, a toolbox—into the scene. We have decided, with certainty, on what our body parts can do for us. But then we find it’s easier to relate to a mouth that is actually a hand than to a mouth that is truly a mouth.

Something is off: these characters composed of human flesh feel more alien than the matted blue Cookie Monster. With a ratty, loose bag over his head, Cookie Monster looks like a well-loved toy. His movements are not dissimilar from those of a toy handled by a child, its body grasped and shaken around to imitate speech during play. Would you call eating all the cookies a character flaw? Cookie Monster might think about this, and then shake his head no. Which means that someone, under the blue fur, is waving goodbye, or maybe hello.

Isabelle Rea is a writer who lives in New York.

August 29, 2024

Le Bloc: An Account of a Squat in Paris

The squat. Photograph courtesy of Benoit Méry.

People stood out front as if waiting: smoking, talking. Of consecutive sets of doors, the first one bore a monogram in stenciled capitals: B-L-O-C. A grille resisted lifting, sticking. Just inside was a foyer, at the back of which stretched a crescent-shaped desk referred to by squatters as the Accueil, “reception.” Watch was kept. Behind that desk a crank could operate the grille.

“This is a building of the people,” the squatter Dominique, who had worked construction, told me, referring to its history as a public health agency and its suitability for heavy use. Hard floors swept clean. Banks of cabinets, their material a blond composite, lined the halls, which at rhythms of their own let onto rooms that had been government workers’ offices. These doors, green frosted glass, shut with a clang. They kept in the warmth of space heaters. Open, they let smoke and music circulate; they aired disputes. A squatter who was a woman—women were a minority at Le Bloc—drew my attention to gaps in the fabric or paper stuck up to cover certain doors. People liked to see feet coming in the hallway, company, warning. Each door wore a padlock.

Living quarters in this way took up the aboveground stories, thirty to thirty-five offices a floor. Into bathrooms, which variously came with pairs or rows of sinks, sitting or squat toilets, and mirrors, squatters had built showers. At least one room per floor served as a kitchen, but all did not have kitchen fixtures. The kitchen on the second floor, though it was much used, lacked a sink. A squatter who lived on the third floor told me they’d had, on that floor, to padlock the kitchen. Reputedly clean, it attracted the messier residents of other floors. After they finished making messes on their floors, they came and made a mess on the third floor. Though he characterized the padlock as a necessity, it embarrassed him, as the proper role for a squat, by which he seemed to mean its default action, the direction of motion within, was to open, he said, not close.

Hallways wrapped the building, graffiti serving as street signs. In a stairwell, French words for “Live Fast Die Young” marked off the third floor; a death’s-head labeled the basements. At least one of the artists spoke of signing pieces “Le Bloc” in the hope of getting work piling up to cohere into a movement, and while I don’t think this plan gained traction, the will was genuine; some artists developed a memorable brand: a skull and crossbones below which unfurled the legend, in English, LE BLOC SONS OF ANARCHY.

They had at least one motto: Tu dors t’es mort, “Sleep and you’re dead.” This was explained to me as a challenge, serving to encourage participants in a shared project of sleeplessness, and as a constraint on behavior, to dissuade them from falling asleep just anywhere.

On the ground floor was a gallery in two devoted rooms. Caravaggio had worked before with some of the artists in residence at Le Bloc, and the squat’s management was meant to take a cut of sales.

The first basement level, called the moins un, was used by the squatters for building-wide meetings as well as public-facing open houses. It surrounded a patch of greenery, the base of an atrium within which a disco ball had been suspended to cast, on sunny days, a fractured light. Picture windows contained this, a garden at the squat’s core.

The −2 was low ceilinged, utilitarian. Ducts snaked, silver prisms. DJs set up there, parties spilling over, and I heard some people even lived two stories deep.

The −3 had been a parking garage, as had the −4, where during the building’s occupation runoff of its every leak would end up, black pools.

According to the documents of their eviction suit, the squatters’ entry had been forced. But judges tasked with the case all failed to investigate the nature of this break-in. And the squatters maintained otherwise; as for other assertions about Le Bloc this one’s greatest value did not lie in correspondence to historical reality. “A trade secret,” one may have said.

Sometime in December of 2012 their neighbors, perceiving the occupation, alerted police. A bailiff stopped by, taking names; now it was 2013. Out of perhaps two hundred squatters (they gave higher estimates too), thirty-six at the most were, by the time of their court date that June, named as defendants. The bailiff, in the proprietor’s pay, was motivated to give a low head count, as one of the squatters explained to me; this one, in any case, did. A far underpopulated occupation was harder to defend, seeming less reasonable to the judge. As there might be damages to pay, squatters, for their part, considered it strategic to feature as defendants those of them who were insolvent.

With other first arrivals Caravaggio invited artists, everybody. The building’s occupants referred to its square meterage, a brag: “seven thousand,” “eight thousand,” they said, a figure that, reported in documentation of the later renovation, was, very precisely, 8,186. They developed a sense of themselves as historically important; when squatters called Le Bloc the biggest squat in Paris, one tended to believe them. When, somberly, a young artist called it the biggest in Europe, I understood her to be referring to the eviction, the year before, of the massive Tacheles in Berlin. (I was interested to read in promotional materials for a concert at Le Bloc the contradictory claim that Forte Prenestino, a squat in Rome and one band’s home turf, was in fact the biggest in Europe.) About Le Bloc’s early days, about its parties, I would hear even years later claims that struck me as outrageous; there was one about a sponsorship by Red Bull, the corporation, said to have installed dispensers for its product free of cost on every floor. Red Bull did not respond to my requests for comment; I was ready to forget this claim entirely but then found mention of Le Bloc in an article about Parisian nightlife on RedBullMusicAcademy.com, apparently a hub for sponsored content. The title of the French article dated September 2016, three years after Le Bloc’s eviction, translates to “A Permanent State of Party.”

Not every artist working at Le Bloc would sleep there. Many simply kept up studios in a range of disciplines. 3D printers filled one; jugglers practiced in a basement room. A craze built for a photography style referred to, in English, as light painting that, over the course of a long exposure, left the subject swaddled in strands of color swirling as if at that person’s command. So they set about immortalizing each other. A sculptor made installations out of Le Bloc’s trash. Preeminent were the graffiti artists, understood by squatters to be well known in graffiti artist circles. Empty cans stacked artfully into a grid were sprayed with paint, contributing another oeuvre. Despite the rate of repainting, certain murals were left alone by unspoken agreement. Despite the heterogeneity of expressive practices and a certain factionalism within the building, it was rare to see tags sprayed to deface a finished mural.

Beneficial, for any squat, was having neighbors on its side. Neighbors of all kinds were understood to side with artists. The squatters of Le Bloc, as early as January, distributed flyers, letters describing their practices. The −1 partitioned into alcoves in which these residents could exhibit even as it allowed for a view of the group: paintings, knots of musicians, “wellness” activities. An activity for children was set up, fans crowding heaped balloons that made them jump.

Some squatters from Le Bloc would have it registered, enabling the entity, and themselves really, to accept donations. Crucially, in collecting unsold food from supermarkets, this organization’s members would be able to ask the employees for leftovers directly rather than dumpster dive. A woman from the second floor went early in the morning, wheeling a shopping cart to be unloaded in a hallway near Reception. Free for the taking: yogurt, which stays good long after the date; packaged meat and sandwiches; vegetables with skin in such condition it would give way at a touch. Heads of lettuce crowded a cabinet opposite the second-floor kitchen, peeking out.

Thus the association Le Bloc was incorporated after several months of occupancy in a “declaration to the prefecture of police,” which squatters filed with that prefecture on May 28, 2013. Le Bloc, according to this appealingly breathless founding document,

responds to the flagrant lack in terms of [sic] artistic fabrication; cultural, social, and technical exchange; Le Bloc must respond at top speed to the recurring and endlessly unsatisfied needs of local artists and technicians in terms of spaces open to implementation, to creation, to information technology, and to practices in every discipline of artistic, technical, cultural, and social research.

The prefecture of police, as was standard, promulgated this notice, duly publishing it in a registry that June 8.

Wednesdays in the second-floor kitchen, volunteers and at least one salaried worker making up a “Squat Mission” of the NGO Médecins du Monde (“Doctors of the World,” spun out of the better-known Doctors without Borders) held office hours during which they gave advice and helped the squatters with their chores of paperwork. A common problem was that of domiciliation administrative, the address where, still today, a homeless person can receive the documents so important to the French welfare state. Addresses were available; you did have to know about them. A foreign woman with a toothache was advised to have it checked out by any means at her disposal.

Despite resorting to the state in such cases, or because the squatters knew the processes of recourse intimately, they were triumphant in describing social services that they provided to subjects the state couldn’t help, beating it at its own game. Housing was just the most obvious. They spoke pointedly about the irony they identified in a health agency’s shuttering of a building so manifestly able to serve as emergency shelter. That the agency had left behind archives of private data, health records, seemed to these squatters final proof of a fundamental indifference of which they’d always suspected their political leaders.

They had begun making their lives there around the time of a date in December 2012 coinciding with the 5,125-year cycle of an ancient calendar, widely reported as a “Mayan apocalypse.” The forecast was, for these squatters, the stuff of shared jokes. Le Bloc had begun at the world’s end, they would say. The squat picked up where the world had left off.

More often they spoke of “competences,” what each of them could do. During the first of weekly meetings squatters introduced themselves, I later heard, by tallying their skills, suggesting to the group that anyone interested in picking up a skill—screen printing, say—should come see them. I heard a squatter worrying, conversely, that the community was unable to properly to care for individuals who might, this squatter felt, require psychiatric attention. They lacked training, were “not social workers.”

Among themselves, they encouraged communal meals: they all liked to eat and drink well, and it was, in the same squatter’s opinion, shutting oneself in that led to violence, madness, all that which began in overreaction.

Voices swelled in halls, the glass doors grating. Fluorescents buzzed and flickered.

Caravaggio, who spoke in the accent of the suburbs (a way of speaking he adjusted for the benefit of my understanding, automatically correcting himself when, interviewed, he used slang), at last told me his work at Le Bloc wasn’t all “social” or charity. “If I hadn’t opened this,” he said, “I’d be in the street. And so would my buddy over there, and my other buddy”—the litany became joyful—“and this young man wouldn’t have any place to work …”

He was fat, a round face split by his laugh. My tape is messy with the voices of some friends of his and fellow squatters as he gamely let them draw out his responses. We sat at a table in a hallway, these others helping advance a discussion of incarceration to which Caravaggio, getting laughs, contributed harrowing tales, for my benefit pausing to gloss differences between the French prison system and the American. Of bystanders, he demanded hashish or tobacco. When I asked about children at Le Bloc, he shouted obligingly down the hall: “Mehdi, is your little girl around?” Apparently she wasn’t, but a man emerged, presumably Mehdi, and, letting out a wet laugh, started talking to both of us about something else: a history he shared with Caravaggio in “trashy” squats (à l’arrache) that meant the two men, finding themselves among “artists” at Le Bloc, were upwardly mobile, for them another occasion for hilarity. In the halls Caravaggio fielded and made requests, responding in Spanish to a woman who complained in Spanish that she had no money. Men interrupted our interview frequently to ask about a job on which, apparently, he was lead. Mosquitoes were breeding on the −4, where the pools of Le Bloc’s effluent had opened up and stagnated. Someone had set down plywood, bridges. A wall was fleshy with the eggs. The men would haul sacks of cement to this, the deepest sub-basement, where it was dark as well as swampy, and fill in the plashes.

“I can come back later if you’re busy,” I said.

“No, no, don’t worry,” Caravaggio said. “You’ll come with, and we’ll keep going. We’ll just be doing some construction work, and you’ll ask us all about what it’s for.”

It was understood in other Parisian squats that within superlatively populous Le Bloc, certain men enjoyed authority. Caravaggio did, for having opened the squat; so did others, for reasons less immediately clear. Useful to an understanding of Le Bloc is that many of the other squatters found these men intimidating. All called them tontons. The reference was to Les Tontons flingueurs, an old flick whose title is rendered in English as Crooks in Clover or Monsieur Gangster.

At Le Stendhal, gossiping, I brought up the matter with a squatter who told me delicately that while Stendhal squatters believed in direct democracy, Le Bloc had a more “representative” model. Visibly tontons commanded authority in settling fights. At one of the building-wide meetings that took place weekly they stood together to announce a rent hike, fifty euros a month to sixty.

The squatter Le Général said in the tontons’ defense that going to open up buildings did eat up resources. Scouting vacancies, they paid for gas. They had to buy brooms, a video projector, those sacks of cement, Caravaggio told me humbly. Another tonton said that a police informant warned him, once, about how tontons would get in real trouble if ever they made money off a party. The cop would’ve hated for that to happen. “He was a subtle cop,” the tonton added, not like other cops.

Caravaggio, orchestrating introductions—“In France, we give bisous, kisses, even to the boys”—brought me to this tonton’s room, on the fifth. In the association’s founding documents, some squatter had bestowed on “Big Vincent”—the very tallest of Le Bloc’s Vincents—a title. Caravaggio, for my benefit, used it, addressing Vincent as Monsieur le Président.

“You’re looking for how this place is organized?” Vincent said to me. “You’re looking for a unicorn. The problem is that the people here are marginal. They’re here because they reject rules. That’s fundamental. So it’s impossible to make up rules specially for these same people.”

“We make rules,” Caravaggio said, “but a minimum.”

They relaxed, eventually joking between themselves, men, about certain women at Le Bloc. I had a hard question, about the resolution of disputes. “On the subject of management,” I said, “someone mentioned a kind of internal court.”

“Oh yes,” Vincent said quickly, “that’s us, we get together at night, we go to the −4, and Le Général …”

I cut in, alarmed. “The −4?”

“But of course. You want to wale on somebody, better do it down below. It’s more discreet. It’s every Thursday night, this get-together.”

“He’s joking,” Caravaggio said, uncomfortable.

But I would have it confirmed by another tonton, by two tontons, that such a body did exist, created in response to complaints the squat’s government was insufficiently transparent.

***

The building’s size was a point of pride that many of them held in common, but it was not the only one. Caravaggio, early in our interview, rattled off the squat’s constituent ethnicities, in his brag an echo of that value shared with corporations. Squatters made appreciative reference to Le Bloc’s multiformity. Their origins were various and included Algeria, Chile, Côte d’Ivoire, Ghana, the overseas departments of Guadeloupe and French Guiana—which I will call by its name in French, Guyane, so as to avoid that possessive—Italy, Jamaica, Japan, Kazakhstan, Mauritius, Mexico, Morocco, Romania, Senegal, Spain, Togo, Uruguay, the U.S.S.R., and, even before my arrival, the U.S.

I kept hearing women at Le Bloc were treated well, a claim that gave itself the lie in its very syntax (in the cordoning-off of women and the looming question of the subject, a potential aggressor to whom cover had been granted). Still, though the tontons were not, in my woman’s experience, bien-pensant regarding gender, one French artist transitioning while living at Le Bloc felt well there. A few of the others, given the chance to correct a bailiff on the matter of the artist’s pronouns, did so with apparent eagerness.

Here and there lived an otherwise homeless Frenchman taken in by tontons some years previously on the conditions that he quit drinking and do the dishes. A petite, emaciated man with a beard ending at his chest and tons of bracelets, he was called Jesus.

One tonton, a thickset, dreadlocked Frenchman, unnerved me by only very late in my reporting addressing me in English that was perfect, even posh. Of some other tontons, he said: “The problem is that these people have trouble communicating, so they’re just going to get upset and smash people up, and I don’t think it’s the proper way of doing things.” He had gone to boarding school in Kent, he explained.