The Paris Review's Blog, page 6

June 24, 2025

What Goes Wrong When We Write Ghazals in English

Bradford Johnson, Auto Arborescent (Blue). From the portfolio Photographs of Past Paintings, which appeared in issue no. 168 of The Paris Review (Winter 2003).

Everybody likes ghazals. Or they do when they learn what they are: A ghazal is a poetic form originating in and strongly associated with the Islamic cultural sphere. It is a medieval thing—or what Westerners would call medieval. Many famous Persian poets are famous for their ghazals. Likewise, Arabic poets, Turkish, Urdu … The ready-to-hand comparison is with the Italian sonnet. Ghazals are a lot like that: song length, rhyme heavy, lots of lovey-doveyness, lots of over-the-top cosmic reasoning.

It took forever for modern English-language poets to pick up on the existence of the ghazal, but once the word got out, plenty of smart people started trying to write original ghazals in English, with differing commitments to the formal rules. I’m one of these poets.

This piece is about translation, but it’s also about writing original poetry in one’s own language while following the rules developed for a different language. I want to talk about English ghazals, but (for lots of good reasons) I’m going to start in left field … with haiku.

You know all about it. Three lines, seventeen syllables: five and seven and five. Lots of people, that’s the one thing they know.

But ask the editors of Modern Haiku what they think of that. They will say: naive. And sure enough, open any issue of Modern Haiku or any other high-profile English-language haiku magazine. You won’t find any five-seven-five.

See, people who are serious about the art of haiku all know a Japanese syllable is not equivalent to an English syllable. This is because English absolutely teems with one- and two-syllable words—and words of five or more syllables tend to come off as supercalifragilistic. Meanwhile, five-syllable words in Japanese are perfectly commonplace.

English Japanese

cuckoo hototogisu

cricket kirigirisu

And so on. Or put it this way: An English syllable tends to have more information in it than a Japanese syllable does. This is why, when you translate Japanese haiku word for word into English, you get way fewer syllables, like

you fire burn

good thing will show

snowball

This is why I was taught that, instead of going by the numbers, you should follow the Japanese principle that’s at stake, which is extreme minimalism. If English had been the first language of the people who invented haiku, the rule would have been three-five-three or maybe four-six-four. They would have considered five-seven-five too roomy. The concept behind five-seven-five in Japanese is that it leaves zero space for filler. It forces parataxis.

There are other things that could be said here. The different status of stressed syllables in English compared to Japanese, the smaller palette of vowel sounds in Japanese—and so on. But all to say: These differences matter. The person who translates Bashō into an English five-seven-five is mistranslating. What happens—what has to happen in order to achieve syllabic parity—is they translate the meaning and then add syllables to fill out their five-seven-five. So you get a floobery haiku, which should be a contradiction in terms.

Ghazals—it’s a similar problem.

The rule says: Couplet after couplet should end with the same word or phrase and with a rhyme sound right before the repeated bit. Can this be done in English? Yes. But has no one noticed that it’s an awkward mess when you do it in English? Could it be that the grammar of English differs from the grammar of Urdu and Farsi and Arabic in important ways, making it a bad idea to imitate the formal specifications at the expense of the principle that animates them?

I’ll give an example in a minute, but first I’m going to say something deep and deeply upsetting: Contrary to what you were told by teachers all your life, the formal parameters of poetry are not arbitrary, are not rules for the sake of rules, are not there as barbells for the poet to lift to show how strong she is. No, they are all designed to play to their languages’ strengths. They secure desirable effects—that is their warrant and their glory.

Because of the syntax of English, it is easy/graceful/elegant to start sentence after sentence with the same word, but it is not easy/graceful/elegant to end sentence after sentence on the same word. You wind up ending on some weak prepositional phrase that you would never be tempted to deploy in that way, except for the rule. You get no pleasure writing it; the reader has no pleasure reading it.

It should worry people very much that if you translate Urdu ghazals into, say, English, simply repeating back in English what the Urdu verses say, it is virtually never the case that the words at the end of the Urdu strophes stay at the end in English. What does that tell you?

Look, you don’t have to learn Urdu to see my point. All you need is to look at an Urdu ghazal transliterated into Roman letters. You will see the repeated phrase; you will see the rhymes. Let’s do this.

Here is an authentic ghazal by my favorite twentieth-century Urdu poet, Firaq Gorakhpuri (1896–1982). Unless you speak Urdu, you’re not very likely to have heard of this guy. That’s why I picked him. I’m hoping somebody will do a new translation of his poems. Here is my source text:

Photograph courtesy of Anthony Madrid.

I love that photo. And now here is the ghazal, with the repeated phrase in italics and the rhymes in bold:

Humnawa koi nahin hai woh chaman mujh ko diya,

Hum watan baat na samjhen woh watan mujh ko diya.

Muzhda-e-Kausar-o-Tasneem diya auron ko,

Shukar, sad shukar, ghum-e-Gang-o-Jamun mujh ko diya.

Par farishton ko dieye tu ne, tau kya ghum iska,

Yahi kya kum hai, ke insaan ka chalan mujh ko diya.

Wahdat-e-aashiq-o-maashooq ki tasweer hoon main,

Nal ka eesaar, tau ikhlaas-e-Daman mujh ko diya.

Mil gaya tujhko jamaal-e-rukh-e-rangeen ka chaman,

Dil-e-sozaan ka yeh tapta hua bun mujh ko diya.

Khatam hai mujh pe ghazal-goi-e-daur-e-haazir,

Dene wale ne woh andaaz-e-sakhun mujh ko diya.

Shair-e-asar ki taqdeer na kuchh poochh Firaq,

Jo kahin ka bhi na rakhe woh fun mujh ko diya.

And, now, here is K. C. Kanda’s translation (2000), in every detail identical to the text below; I have altered nothing:

I am given such a grove where fellow-warbler I’ve none,

Such a country is my home when none understands my tongue.

To others you have held the promise of the wine of paradise,

Thank God, to me is given the grief of Ganga and Jamun.

If angels are endowed with wings, I’m unconcerned.

That you have made me man, is my recompense.

The unity of love and beauty lies in me condensed.

I contain the love of Nal as well as the troth of Daman.

To you is given a radiant face, garden-like abloom,

To me is given a barren heart that desert-like doth burn.

I represent the ultimate in the field of modern verse,

The style given to me by God is the envy of everyone.

Ask me not the poet’s fate in the modern age,

Thanks to my poetic gifts,—I have been undone!

I’m not saying that’s a great translation. But anyway, can you identify, in the English version, the phrase that is repeated verbatim at the end of every Urdu couplet (“mujh ko diya”)?

It’s not easy to spot! Let’s see what happens if we feed those three words through Google Translate:

مجھ

mujh = me

کو

ko = to

دیا

diya = given

It translates, roughly, to “to me is given.”

Look at the poem again. Now you can see: it’s part of a verb construction, bound up in a bunch of idioms. No surprise to find it at the end of the line in the original because Urdu is an S-O-V (subject-object-verb) language. English, unfortunately, is S-V-O. Which means: When it goes into English, that V has got to move.

Are you starting to see? If English syntax allowed you to elegantly end sentences with the main verb, you could end your ghazal couplets with a more satisfactory word or phrase. But, in English, satisfactory endings tend to be nouns. And if you end every couplet with the same noun, how are you going to get that ghazal dynamism, where each couplet becomes its own thing, every charm on the charm bracelet different?

I know, I know. I’m overstating. I’m acting like all this is “always” when I should be saying “most of the time.” Also, I’m needing you to trust me that the Firaq poem instantiates a typical phenomenon in Urdu ghazals.

I’ve been gazing at this stuff for twenty years, this whole time trying to figure out how one could follow the spirit of the ghazal form without getting shipwrecked by the IKEA instructions, so to speak. I’ll share a couple ideas. In order to do the rhyme so that it’s subordinated (i.e., not allowed to act like any kind of rhythmic end stop), you could do something I call “hand-off rhyme.” The last word of line 1 (in a couplet) could rhyme with the first word in line 2. Or, if not the first word, almost the first word. The rhyme will still be audible, but it will run by you the way it does in Urdu.

And since the repeat word is so hard to install at the end without messing everything up, what about untying it from the end but making it a very sticky-outty verb or adjective or adverb, such that the reader will be able to experience it as a repetition clear as anything?

Let me see what happens if I retranslate the Firaq, above.

My portion is a stand of trees, and I am the only songbird in it.

The minute I sing, my portion on earth is an uncomprehending stare.

It is for others to drink and to cherish the wine of Paradise.

The paradox is my portion is to drink from these Hindu rivers.

If the angel’s portion is a pair of wings, what is that to me?

You see I’m content that my portion be the shape of a humble man.

… That’s not that bad. I’m stuck with repeating a noun, but the rhymes aren’t forced, and the verbal repetition is not only respected, but made to deliver.

Anyhow, you can cut me some slack; these are improvisations. And if you’re thinking portion sticks out too much, then you really are understanding my point. Firaq did not put a noun in that slot, and maybe by this point you’re starting to see why.

At any rate, these are the questions the writer of an English ghazal should contemplate.

There’ a part of me that longs to quote some choice specimens of original English-language “ghazals” from respected national magazines over these past ten years or so, but that would be like when I show my students examples of rhyming couplets written by beginners. Every other line: godawful awkwardness. Every other line: words and phrases the poet would never have used in a million years, except they had to hustle that rhyme word to the end of the line.

All this is bigger than ghazals, of course. Bigger than haiku. I’m saying we have to graduate from pastiche and mimicry to something higher. We have to stop looking at somebody like Firaq and saying, I must do what he did. We should be saying to ourselves, I must do what he meant.

Firaq! you are bones, you are no more to be found. Yet, listen to my words.

The birds in the trees are asking that all this be forgiven me.

Anthony Madrid’s writing has appeared in The Best American Poetry, Boston Review, Conjunctions, The Georgia Review, Harvard Review, Lana Turner Journal, and Poetry. He is the author of three books, I Am Your Slave Now Do What I Say, Try Never, and Whatever’s Forbidden the Wise.

June 20, 2025

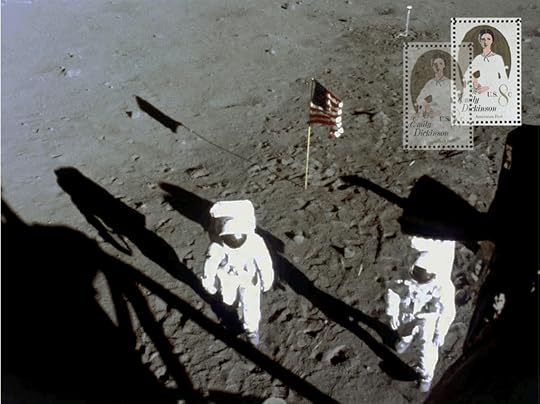

Dickinson’s Dresses on the Moon

Collage. US Postal Service, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons. Project Apollo Archive, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Look closely at any moon landing photograph and you will find fine gray plus signs in a grid across each one—plus signs that allowed for distortion to be corrected + for distance and height to be calibrated from space as well as on the moon’s surface. That could stitch a panoramic sequence of images + plot the moon. Each Hasselblad camera the astronauts brought was fitted with a clear glass plate etched with this precise network, a réseau of stitches—pinning the moon to the moon to keep its surface and the vast black horizon in line. Reseau: a grid + a reference marking pattern on a photograph or sewing paper + an intelligence network + a net of fine lines on glass plates + a foundation in lace.

+++

Look closely at many Emily Dickinson poems and you will find + signs that indicate a variant in a line. A variant may appear + above a word + to the side of a line + underneath a word + at right angles to the poem + stacked at the end like a solution to an equation. Whole poems + sequences may be variants of one another. Dickinson did not choose among her variants, offering them as concurrent alternatives— evocative lace constellations left for us to hold up to our future sky as we try to align the wild nights + noons of her poems + epistolary impulses. Stitched across the surface of her work—plus signs that allow for + stray signals + distortion + that calibrate interior vastness.

+++

Rather than the stunning aluminum-coated fabric of the Mercury crews stepping out of comic book frames of imagined interstellar travel, the astronauts who planted their feet on the moon were outfitted in the same glaring white as a wedding dress. A color in the future that will become as synonymous as silver with the zeitgeist of sixties space-age fabrics—avant-garde apparel made of paper and metal and mirrors and all that lamé, every garment a mise en abyme reflecting and replicating a future possible. Silver and white, twin colors that wax and wane in popularity across time, reappearing again and again when we most need to transport ourselves beyond whatever present moment in which we find ourselves suspended. Colors that carry us across the thin gray twilight line that separates us from a speculative future.

Fifty years into that future, it’s difficult to undo the images of those sonogramic white suits. The ghostly bulk of the astronauts’ bodies adrift on the moon now an afterimage in our collective consciousness. The exterior garment as luminous and otherworldly every day and intimate as the era’s conic Playtex bras. Chosen in part for the fabric’s superlative heat resistance, in part because its less reflective surface kept astronauts safer from the risk of dazzling themselves with their clothing while facing the unfiltered sunlight. Underneath this bright white micrometeoroid layer, underneath the layers and layers of nested silver insulation, the main pressurized body of the space suit is a simple Earthly blue.

+++

The year we landed on the moon a documentary is screened detailing the seemingly impossible technological processes involved in getting us there. Over looped footage—a modified sewing machine moving stitch over stitch over a seam—a sheet of mylar pulled from a roll until its silver fills the screen—a pair of gloves being constructed blue finger by finger—there is audio of women talking. Chatting back and forth with each other as if they were doing any day’s work. The hidden intimacy of the moon is in this small loop: the space suits with their otherworldly specifications had to be sewn one by one.

The seamstresses hired to help fabricate the space suits first had to learn how to read engineering blueprints, to understand construction and seam lines from drawings rather than the pattern of a previous garment. There was no previous garment to take apart, no way to learn where hidden seams and extra protection from friction might be required. No lines or creases or details to close read what happens to fabric on the body when worn on the moon, the intricacies or possible failures of a former design. The seamstresses had to sew the space suit together in their minds. Undo it to imagine it again as flat fabric. Understand how to cut, piece, dip, coat edges of ever more wild fabrics to keep them from fraying, tearing, coming undone in space while being worn.

Given the unfathomable demand for stitches so meticulous they would allow a body to safely endure a lack of breathable air, the seamstresses learned to sew at a level of precision even the most spectacular Earth garment would never call for. They learned to sew with almost no use of straight pins to tack together their fabrics and keep them from slipping as layer after layer of delicate fiberglass heatproof fabric was run through the machine. That even a single misplaced stitch might call for a suit to be fully restarted. Learned an errant pin and an infinitesimal hole in the pressurized suit were the only difference between—and—. And no Earthly rehearsal before the seamstresses’ trick of turning flat fabric into an airtight heirloom was performed live by astronauts in front of a national audience.

Pinned down in grief, and imagining I have landed on the moon, I hear them. Their voices bounced down fifty years in the future like stray signals from the night sky. As if I am overhearing a garment in process across multiple moments in time.

+++

Emily Dickinson’s one white dress is a copy. Of which there are actually two. Dickinson’s one white plus twin replica dresses—make three. Three white dresses are not literary lore. They are the beginning of a bedtime story: In the great green room there were three white dresses, three dresses in white that were acceptable to be worn around the house though not around town, sewn in a nineteenth-century style called a wrapper housedress, meant for housework and harder wear and more often than not made of darker fabric. Though obviously not Dickinson’s. Even if by then white cloth was considered easier to clean than fashionably bright aniline dyes and prints, might even have been considered more practical, her many white dresses still invited hot gossip. After all, other than brides and mourners, who only wears white? Dickinson’s unlikely white dress is often speculated to be bridal, as if she considers herself wed to her poetry—or to God—or to herself. Dickinson’s one white dress, in which she was always talking to death.

But a historical artifact cannot be taken apart at the seams in order to make a pattern for twinning, cannot have its stitches cut one by one. To make a new pattern from an existing garment that must remain intact is called “lifting” or “rubbing off.” The dressmaker hired to twice replicate and lift Dickinson’s one white dress had to imagine the pattern from seeing the dress already put together. Had to take it apart in her mind. Plan it backwards. The language of producing a facsimile dress is the language of the writer at work: drafted, corrected, proofed. Though only the first was likely a collective effort, drafted, patterned, and stitched in a room with other women in intimacy.

It’s difficult to know when entering the exhibit of her house which dress has been pulled out intact for display—the dress that embodied Dickinson’s body or the dress that suggestively embodies her mind. The dress and the story we tell about her round and round. Hard to know in which she’s hidden herself. In a white dress where would she hide? Three white dresses, each with fourteen yards of trim like the frill of a stamp’s edge along the collar, the cuffs, the unexpected note-size pocket with its envelope-flap closure. Only one with original embroidered lace. The iconic, dead-ringer dresses, one or the other, resting on a dress form in the East bedroom, arms bent as if about to take off. Her fair copy is kept safe in a glass case across town.

+++

How many worlds can a garment inhabit at one time? Let me reverse some of its stitches. In the city where I will be born an inventor will begin a humble company making latex bathing caps and swimwear. The company will grow larger, move cities, divide itself into different cells, some for the war effort and some for more commercial manufacturing. After the war, women from surrounding towns will be hired to work on the lines at a newly announced division, Playtex, stitching bras and diaper covers and latex-dipping “living” girdles. Twenty plus years into the future, it’s seamstresses at Playtex who are initially tapped to move over to the handcrafting of space suits for the NASA astronauts.

Every other company’s proposal for dressing and encasing the interstellar body in a military-engineered solution will fail. Their armor-like designs incapable of mimicking the human form or allowing a body to move with enough grace in low gravity. Hard-shell relics unsuited to carrying anyone to the moon. Playtex’s flexible rubber girdle and the bra’s nylon tricot was, is, and will be the secret to fitting women’s earthly bodies into the restrictive garments of Dior’s postwar New Look and the astronaut’s bodies into space suits. A garment that holds both a future and a past body in its fabric. An impossible, other-worldly, fantastical body achievable only through an adept understanding of how to alter the figure underneath the architectural lines of the clothing. In other words, through the illusion technology of undergarments.

Much of the language for the technical components and construction of the lunar space suits will be of the body: bladder, ribbed rings, webbing, joints. A language of intimacy and interiority. A language the seamstresses will already understand. Closer to earlier forms of embodiment in which we clothe a spirit with a body—a space suit: both an embodied body and an intervention of the body. The interior of the space suit touching the exterior of the body. The exterior touching endlessness. Each latex-dipped component a well-guarded technique to a fragile body dazzling us while bouncing through airlessness. Each of the space suit’s seventeen concentric sheets of mylar glued by the seamstresses, thinner than single-thread lace. A body kept safe in the vastness of space through couture handiwork—a reseau of women rendering the moon possible with precision stitching and cutting and gluing. An abundance of hours.

+++

At any given time just one of Emily Dickinson’s white dresses is planted in her bedroom like a flag on the moon, stiff and awkward, trying to float on a breeze that does not blow. A room that has been celebrated for housing a mind that looked like no one else’s mind ever. A mind capable of making poems like lace, full of gaps and pauses and absences. All those variants letting us listen in as she works out a live problem on the page. All those em dashes with dots over the top, turning connective pauses into birds, inviting us to leap from one space to the next. To keep the vast horizon of her mind in line. As if her words were signals bounced from places more vast than we can imagine—reflected off the moon’s surface—returned to us overheard.

+++

Listen closely to any worn garment and you will find fine lines that mark details of construction + patterns of wear + indications of more than one wearer. Signs of possible variation + annotation + distortion—initials embroidered along a pocket + the strain in a buttonhole that might indicate a garment was worn during early stages of pregnancy + the ellipsis of holes showing stitching has been undone—seams and hems let down + let out + in. These lines will allow you to draw the garment + take it apart in your mind + translate its cut and composition onto the page. Create an image + a pattern + help calculate the relationship of one part or one wearer of a garment to another.

Listen. I am reading the garment out loud.

+++

For over a century there has been just one verifiable photograph of Dickinson. In the iconic black and white silver daguerreotype, she is not wearing the white dress. She’s a teenager fixed in a dress she will live in forever. And that dress is made in an undefinable dark printed fabric with a slight sheen. Not surprising, given dark fabrics were considered more suitable as it kept sitters from becoming spectral blurs—there and not there. But people will mostly forget this first dress. There’s nothing spectacular or singular about it. The daguerreotype era produces millions of replica dark dresses. There’s no narrative we can attach to its common folds. The white fabric arrives in the future.

One hundred years of one documentary photograph and one surviving white dress going round and round, depicting Dickinson as an ethereal-looking teenager superimposed over an ethereally dressed adult. Even as it’s been told round and round that neither her family nor her considered the image a particularly good likeness. Until a second possible daguerreotype is uncovered. In the image there are two women, two dresses. One dress a griever’s black speculated to be worn by a recently widowed friend. The other, when magnified, revealed to be checks—a grid of fine lines woven through the fabric. A pattern that was considered best for daguerreotypes, a perfect contrast in the folds between light and dark. Like the original, the portrait is so small it requires intense forensic attention to gather information about the possible wearers and their dresses.

The Dickinson Museum textile collection is searched. A possible copy of the pattern and sheen of this second daguerreotype dress is found. Fabric with light gray and white threads creating a reseau on a stunning blue background. Swatches of a blue dress that were saved, deconstructed and stitched onto paper backing to be reused, along with other snips of bright dress silks and plaid satins, as part of a hexagon quilt block. A match that might verify Dickinson is the wearer and begin to unfasten the afterimage of a monochromatic era of Victorian mourning wear.

Difficult to then undo the collective image of Dickinson the artist in her singular, sonogramic white dress. What would we do with her, would we recognize her if she came to us in blue? This new future possible Dickinson would be a Dickinson in process and in sequence—stitching and unstitching—patterning her poems and not yet on the moon. A variant twin Dickinson that changes ages, changes dresses between acts from dark to blue to white—who might allow for distortion, for distance between the first dress and the last and now. A panoramic view of her materiality that pins herself to herself. In the absence of a physical dress, we have to reimagine her in a blue wider than the sky, in the long seconds she was suspended and exposed—there and not there—sitting impossibly still as the camera’s lens remained open, arm around a mourning friend, before the salt fixes and gathers her back into black and white like moonlight on the daguerreotype’s silver surface.

+++

So many needle holes and needles + errant pins left in Dickinson’s poems. Not all for sewing. Some used to wound + puncture + stab + mark. And the way she chose to stitch her poems—leaving audible pinholes in their fabric—morse code notes poked straight through the pages—that allow us in the future to take all those undone white sheets, restitch and unstitch them back together in sequence. A panorama of poems + a mind in the gray line between daylight and darkness. Undo each poem + dress and what’s left are the ellipsis of pinholes—dots and dashes—traveling across the fabric + page.

The dressmaker hired to multiply Dickinson’s one white dress first would have made a toile, a practice or draft dress made in muslin, meant to be taken apart to turn into a pattern that could be twinned and twinned and twinned, turning one dress into many. Meaning there are or were likely four possible dresses: the original, the two replicas, and the toile that would have been undone—a speculative future dress + a ghost of the final dresses returned to its prestitched state. A toile is a garment made to be altered, to never be worn. Each of these duplicate heirlooms that will never contain Dickinson’s or anyone’s future body. Or her reason for adopting such dazzling fabric for workwear. Dickinson’s multiplying variants + dresses + pinholes, turning her into many, keeping mourners from creaking across her soul. Dickinson, who was constantly more astonished that the Body contains the Spirit + or that clothes could then contain the body at all.

What a pity that instead of a flag we did not plant a copy of Dickinson’s paper white dress on the moon—symbol of the common poem—+ which, like the moon, affects us all, unites us all. + Each month going round and round—turning from light to dark to the moon’s silver glint and back again depending on whether it’s waxing or waning. As if underneath her one luminous white dress is its exact space-black lace replica waiting to hurtle back to Earth.

Cori Winrock is a poet and multimedia essayist/artist. Her second collection of poetry, Little Envelope of Earth Conditions, was awarded Editor’s Choice for the Alice James Books Prize. Her debut book, This Coalition of Bones, received the Freund Prize.

June 18, 2025

Rehearsal Scenes

The New Chamber Ballet in rehearsal. Photo by Diego Guallpa.

Three dispatches from the New Chamber Ballet’s poet in residence, Diane Mehta, who has observed their rehearsals nearly every week for the past year and a half.

1: The Lift

In the delicate center of the action, each dancer rests her head on the other woman’s shoulder. Expectation slows, tragedy softens, the center holds. They are barely touching. The lean is superficial; they do not need each other yet. This is the prelude to the enormous tension that comes next.

The lift, when it comes, originates in the deepest part of the hips and resembles the ritualistic crouch of a sumo wrestler. The lifter’s thighs look enormous, but she is slim. She plants her legs below her shoulders and extends her arms. The trick is to hold up the rear without sticking it out so that the dancer being lifted settles onto the lifter’s back without a hitch. The memory of the playful lean in the beginning returns.

Each dancer depends on the other to be precise and reliable in a way that life is not. The arriving dancer leans back across the shelf of her partner’s lower back and is immediately secured by an arm clamped around her waist. Her own arm grazes the floor. Her leg points up like a traffic light. When I flatten the image, I see Demoiselles d’Avignon, Picasso realizing that the shape of one woman combines pieces of many. The two ballerinas resemble a chair with a straight back for two people, a love seat in wood.

It is the last week of rehearsals, and the musicians are here with the composer for the first time. The three pairs of ballerinas struggle to balance one another, then switch to new partners. It is a lesson in creating an approach and making adjustments with each companion. Every weight-sharing experiment in becoming one body is improvised because no amount of training can anticipate what has unfolded this morning, when these minds and spines crossed the street or exited the subway. No lift—not next take this rehearsal nor one two months later—will ever be the same as the one in progress now

Watching the women sweat, I realize that an enormous strength is being distributed. Their bodies are talking so loudly that I can hear them: Don’t fall! Put your hip here! Leave me because I’m leaving! When a dancer slides precariously to the off-ramp of her partner’s rear, the partner tilts a hip ceiling-left or ceiling-right or lowers her back to prevent her from falling off and to help her get higher. The tension is explosive because they are really in the middle of the motion of falling down while staying together. What is amplified is need. The work of caring for someone is a duet, and it changes you. Being in the lift will be the centerpiece of the performance.

The choreographer seems pleased. No one is defeated, no one has succeeded; they are becoming a shape. This is the slow motion of mechanics with the interference of time, gravity, and music. The journey from lean to lift travels from the beginning to the end of a marriage, from childhood to experience, and I am already thinking that when I leave I’ll notice that the day is mild and crowds mingle at the corner—but all of life is already here, in a sun-boiled studio with sixteen-foot-high ceilings and windows that swim across two walls, repeating themselves in the mirror.

2. The Floor

From a distance, it might have looked like childbirth, when you shoot up on all fours to loosen the pain of the beast you are carrying, but it was only a dance between the floor and her. The two-minute routine she is performing is a kind of Pinocchio story: a wooden surface being brought to life and invited to be a legitimate partner. Her job is to make this solo into a duet.

The relationship between a human partner and the floor is intimate but physically demanding. It is about gravity. It is a ballet dancer’s collaboration with the inanimate and the floor’s experiment in becoming an invisible partner who responds to her body parts as they touch down and lift away.

She flings herself on the sprung vinyl floor like a tossed doll. Prone, she fixes her head in the center and begins the counterclockwise floorwork sequence, moving her body on and off the floor: she spins, rolls, softens, jerks her hips into the air while the floor holds down her shoulders. (“I have waited a century for a partner like you,” the floor yells.)

She has fierce muscles that ripple down her back and hips, and her spine is fixed in space while she turns. With the emotional progress of the music—the tempo quickens, the violin gets louder and drops out for the high notes on the piano—she widens her strides to build momentum and lift into a shoulder stand, cheek to floor, while her skirt falls to her knees and her legs scissor open into a split. We are watching all the ways in which a woman becomes more than her desire, and we, the audience, recede into perversions while she folds her legs and continues on her way.

In the mythologies of love we rely on, hearts pound: blood in, blood out. She is the opposite of every reclining woman in a painting. The lines of her body twist like Egon Schiele’s erotic expressionist figures. Her relationship with the floor is not the ceremonial collapse that happens in Pentecostal churches and Yoruba rituals, yet I wonder if she is possessed. I fall into the trance of trying to memorize each movement as it springs away. A sequence is an erasure of moments that came before, yet every move is another beginning.

She is a protractor. The pencil (the dancer), with the aid of a mechanical tool (her body), makes dozens of circles of equal diameter. Watching her recalibrates our own relationship with the floor. We see her spinning on a flat surface that itself seems to be spinning, the two partners tied up in physics and the jagged Newtonian world where everything is at work: momentum, inertia, conservation of energy, torque.

The two minutes have ended. She reverses direction, and in a slow vertical ascent, she corkscrews her body up. By the time she reaches her full height, en pointe, she has raised the tip of her pointer finger, bent it loosely in a rendering of Michelangelo’s muscled God’s gesture to Adam—and in an enormous transfer of power, she hands off her solo to another dancer.

3. The Fight

The action of love is forward motion. Two dancers slide toward each other on the floor and sit on their knees. The music stops. The violin breaks into the scene—fast, high-pitched. The woman in blue strikes, and the dancer in purple blocks. They jab with openhanded strikes. They lean into each other at maximum force with their forearms as they block. If they sever the connection, everything collapses. All four arms are constantly in rotation, like oars. The sequence resembles kung fu—close range but designed to keep an opponent at a distance.

If there is an opponent for these dancers, it is air: they move it between them like a miniature tornado. Then they become the tornado. They are thousand-armed Achilles in a blur on the battlefield, the chaos of swords clashing. The women on the outside pirouette and circle the purple and blue dancers on the floor, as if to egg on the audience for the evening’s entertainment. (“Sailors fighting in the dance hall!” belts David Bowie in “Life on Mars?”) Purple and blue let go at the same time and redirect the momentum of their upper bodies to the left and right of one another, as if dodging strikes.

Choreography is a way of organizing chaos. There is no pattern without chaos, no love without fight. The lean is a kind a lift, but the movement is horizontal. Each body depends on the other, and each dancer’s job is to pay attention to her partner’s gestures and timing. They let go at the same moment. Blue pulls her weight backwards, which brings purple forward, and blue wraps her around her own body. Who is the cobra, and who is the prey? They are still on the floor, tied up in each other. Blue lets go and purple picks her up, then blue wrestles purple to the floor and purple rolls away.

All along, they face one another, not the audience. Dancing is about moving with another human. Performance is theater, while rehearsal is a conversation that the dancers are having for and with each other. They tolerate one another five hours a day, five days a week, fifty weeks a year, sometimes for a decade or more, and that is love. I do not see their legs tremble, but I know they are using every muscle to fight gravity while continuing to jab and block in the process of standing up. Purple strikes an arabesque. Blue moves in quickly to embrace her, and purple folds up her legs. They are Aeneas cradling his father when Troy is burning or the stranglehold in a bronze by Henry Moore or the mothers in Mary Cassatt’s paintings who always love their children so much. They are Virgil wrapping his mother-father arms around Dante in the Inferno and leaping to escape certain death. This is the choreographer cradling all the dancers in his heart to give them comfort and strength. This is my own child in the early years, when it was easy to keep him safe.

Is the purple dancer the father, the mother, the lover? It is so intimate that I don’t notice the three outside dancers sitting cross-legged on the floor with serious expressions. The purple dancer slides down the blue dancer, deflating onto the ground. Suddenly everyone is laying down except the blue dancer who struck first. She grabs a different dancer by the forearm and pulls her off the floor. She falls back without looking, certain she will be caught, before they begin to fling one another around. There is no end to the tension in the choreography of interacting with people we love.

Miro Magloire and Diane Mehta’s first collaborative ballet premieres June 20–21 at the Mark Morris Dance Center.

Diane Mehta was born in Frankfurt and grew up in Bombay and New Jersey. She is the author of Happier Far: Essays and two poetry books: Tiny Extravaganzas and Forest with Castanets. She has written for The New Yorker, Kenyon Review, VQR, A Public Space, and The Southern Review.

June 17, 2025

Catching up with Geoff Dyer

Young Geoff Dyer and a lawnmower. Photograph courtesy of Geoff Dyer.

Geoff Dyer’s new memoir, Homework, was originally called “A Happening.” There would have been something of a joke to this discarded title; from one point of view, nothing much happens in the book. There’s an indelible ordinariness to this coming-of-age story, which, with a few detours, follows Dyer’s early life until he reaches the age of eighteen, in the world of working-class Gloucestershire of the sixties and seventies. Any readers hoping for shocking revelations about the author’s childhood will not find much to titillate them. But of course from another point of view, everything happens. Dyer—has written many books, including Out of Sheer Rage, Jeff in Venice, and most recently The Last Days of Roger Federer—describes in great detail the period in which he became himself, in all the erudition, playfulness, and creativity we might already be familiar with. (Out of Sheer Rage, nominally a book about trying to write a book about D. H. Lawrence, is essential reading for any writer of nonfiction: a funny, moving account of the creative process in its frustrations and joys.) In Homework, Dyer turns his attention to his early life, down even to the accessories his Action Man figurine wore: “the plastic lace patterns on Action’s boots; the khaki elastic strap of his carbine; the little buckle on the helmet strap and the plastic niche into which it was anchored; the genetic logo embossed on his back: Made in England by Palitoy under Licence from Hasbro © 1964.”

Even more impressive is Dyer’s ability to give narrative life to this archive of detail, half a century later. His mother and father are sharply drawn characters, along with the rest of the family. “It was said of Joe that if you filled a bath with beer he’d drink it,” Dyer writes about an uncle. “(I heard this said many times. In Shrewsbury few things were said only once. Everything was repeated over and over.)” Anecdotes are recycled, gaining a kind of mythic status, like “little Audrey Stanley” who used to work with his mother in the school canteen. With these repeated sayings and formulations and anecdotes Dyer conjures something deeper than detail: the lost world of his childhood, but also the lost world of the particular time, place, and class he inhabited. (“Class itself is not a thing, it is a happening,” E. P. Thompson writes, a quote Dyer includes as a postscript to the book, for indeed, it is something that happened to him.) Dyer’s Art of Nonfiction interview appeared in the Paris Review in 2013. We caught up on the phone a few weeks ago about Homework—and about how he managed to render childhood without being boring.

INTERVIEWER

This is a highly detailed, specific memoir about your early life, but also one that describes a bygone era in a particular time and place. How did you balance those two threads, of the personal and social history?

GEOFF DYER

One of the earliest impulses I had was to do something like Annie Ernaux’s The Years, a kind of generational autobiography. I thought it would be cool to do a Gloucestershire, English version of that French book. It ended up being quite different, but the key thing is that there’s nothing interesting about my story. It’s not like I’m a celebrity whose life people are interested in. Also, there are no great revelations. I haven’t discovered I have an illegitimate brother. There’s no abuse. It’s just my story, which is pretty uneventful. But it contains a larger social history of England and a particular phase of English life which I believe is worth preserving. It was my wife who kept saying that I should write this book for that reason, not just out of self-indulgence. The paradox, and it’s a well worn one, is that I could write this larger social history only by telling my own story. When I was discussing this with my American editor, he said, “Should you have an introduction that makes it clear that this is really a book about class?” And I said no, because every detail in the book is so steeped in class. However microscopically, if you look at the evidence, it’s all there.

INTERVIEWER

How did you go about the process of remembering, in such a high degree of detail?

DYER

Obviously I am the world’s leading authority on the subject matter of this book, which is my childhood and adolescence. But with any kind of writing, it’s always about the detail. There were scenes and details that, for whatever reason, often no reason at all, have remained very vivid in my memory. I don’t know why—they weren’t special moments, but they lodged in my mind. In their mysterious way they were my “spots of time,” as Wordsworth calls them in The Prelude. But whereas he offers an explanation of their significance—you know, “This efficacious spirit chiefly lurks …”—I’ve not been able to determine their significance beyond the fact of their tenacity and, on that basis, I happily submitted to their insistence, their quiet lobbying, on the right to be admitted. Also, when I was about seventeen or eighteen and, through reading, became interested in trying to write, I had nothing to write about but my adolescent and family life, and I kept those pages. The writing was of zero literary value, of course, but it comprised a wonderful archive of details I could use.

INTERVIEWER

Were there other kinds of research or self-research involved?

DYER

I never think of anything I do as involving research. It always feels to me like having a hobby. I know a great deal about Bob Dylan, for example, because I’m interested in Bob Dylan, but I don’t do research on Dylan. The other thing is that it has never been easier to write an autobiography or to write about recent history—pictures of every little thing you’ve ever owned are on the internet. I’m an inept user of the internet, but I was amazed at the amount of data about the clutter of my life—of my g-g-generation, as the Who put it—preserved in Cyberia. Now, what none of this can do—this virtual prop cupboard—is give us narrative. That’s provided by people and by the emergence of an individual consciousness at a particular moment of history—moment in, this instance, in the extended sense of the period from 1958 to 1977.

INTERVIEWER

There’s quite a bit in the book on your collecting of objects as a child and a teenager—Action Men, model airplanes, bubblegum cards, records. How did you think about these objects, as tools for memory but also as things that might be put literally in the book?

DYER

The objects are part of a larger universal specificity, as it were. It was related to Ernaux’s project in The Years, where there’s a lot of information about various gadgets that became available at defining moments for her generation. The mistake some memoirists make is to write “We would go down to the shops,” or “We would go for walks.” It’s all generalized. But the continuity has to be particularized, and the objects in this book are all tied to particular moments. It’s about substantiating a time and place. In The Age of Innocence, for example, you hear all about the furnishings of a room, but something is always happening in that room, and the stuff happening is complex human and economic interaction. What’s happening in my book—in my rooms—is more self-centered, but I am the locus of social and economic forces. Sticking with toys for a moment, my fondness for inventory is such that my American editor Alex Starr said, “I’ve had enough of all these toys, can’t we move on to the human relationships?” And I said, No, you don’t understand, because you have brothers and sisters. But if you’re an only child, it’s things that you have relationships with. There’s a line in Billy Collins’s poem “Autobiography” in his book Water, Water—he’s an only child, too—where he writes of an ironic ambition to compile “a catalogue raisonné of my toys.” In this book, I surrendered to the same urge. To make a piece of writing interesting, obviously, the catalogue needs to be imbued with narrative potential. In my case that potential lies in the way toys and cards and the solace they bring to the only child is replaced by books and the discovery of reading in my mid-teens, which whooshes into the vacuum left by my having grown out of a kid’s toyhood. And reading and school lead to Oxford and to an eventual understanding—which came to me only in the period after the book ends—that the process I had been through was actually one defined by class, by social and economic forces which had been at work on everything in the book—the stuff, the things, the people, the culture, the history, that had formed me. This is made explicit by the quote from E. P. Thompson which appears at the very end, as a kind of closing epigraph, because I only understood this process retrospectively, in my mid-twenties, beyond the completed timeframe of the main part of the book.

INTERVIEWER

Childhood can often be a boring subject. How did you think about making it interesting?

DYER

It wasn’t boring to me, but then of course when you meet bores in real life, they’re not bored by what they’re saying at all, even as they’re boring the pants off anybody who is obliged to listen. But yes, I’m in full agreement—when I read biographies, I always skim through the childhood stuff. It’s not until we get to adolescence that it becomes interesting. And of course all the stuff about grandparents is even more boring. I can’t make any progress with Proust, all that childhood stuff is so boring—I just find myself thinking, Go kick around a ball or something. I’ve never had any interest in having children, and in fact have never had any interaction with other people’s children. So on the one hand childhood bores the crap out of me, but I’m interested in the idea of the formation of the self. What makes that interesting to the reader? It depends on the quality of writing and perception—which, I suppose, is what people say when they’re banging on about Proust!

INTERVIEWER

How did you approach structuring this book?

DYER

Originally, I had the idea of it being an extended version of this map of Cheltenham I had made for an anthology. That map, which appears in a box set called Where Are You, is a version of the Ordnance Survey maps of my part of the world. But instead of a symbol where the post office would be, in my map I had a symbol like a fist, in the place where I got punched in the face. Or there were lips to show where I’d had a romantic episode. I liked the idea of the memoir being arranged spatially like that, but unlike with the anthology version, the explanation of those sites—the so-called legend—was going to be much longer, and the words would have taken over. It would have been a very unconventional way of doing a memoir. I wrote a lot—I always think that’s the important thing, to amass a lot of material—and I kept coming up against this structural premise. Instead of being enabling, that structure started to feel like an impediment to arrangement. So I ended up defaulting to the most old-fashioned way of all—proceeding chronologically from my birth, and ending up where it ends, at the age of eighteen. There’s a Roy Fuller poem called “The Ides of March,” which includes the lines “And now I am about / To cease being a fellow traveller, about / To select from several complex panaceas, / Like a shy man confronted with a box / Of chocolates, the plainest after all.” So, after having found a complex panacea, I ended up with the plainest after all.

INTERVIEWER

Tell me about coming to the ending. The final section includes a long passage on your mother’s birthmark, which was a source of great shame to her in her youth, and which she always kept covered. You describe it to someone as “the most important thing in her life,” and writing about it as a kind of betrayal. How did it feel to write about it?

DYER

I knew always that the end was going to involve my mother’s birthmark. It was very upsetting to write about. The element of betrayal to it was because of the completeness of my parents’ privacy and because it so defined my mum’s entire life. I would never have written about it while she was alive. The only thing I would say to justify it is that writing is a private thing for me. I’m always writing my books for me. I want them to end up being published, obviously, but I never write in public, never write in cafés, and I never do a proposal. I often feel while writing that it’s just about articulating to myself something which is important. But I’m conscious, as I’ve started doing public events for the book, that I’m not able to talk about my mother’s birthmark, partly because I know I’ll become upset about it, and because when you’re doing a public event you’re there to entertain the troops. So that would be inappropriate.

INTERVIEWER

Will you write another memoir, picking up at the age of eighteen after you’ve gone to Oxford?

DYER

Absolutely not. Alan Hollinghurst is a great writer, of course, but I think the Oxford scenes in Our Evenings prove that a scene of punting in Oxford is really undoable. It’s often a good idea to stop at some point with autobiography. When celebrities write memoirs, it’s best if they stop when they make it. After that, as Steve Martin said, it all becomes “And then I met …”

INTERVIEWER

Are there memoirs of childhood you love?

DYER

Yes. Martin Amis’s Experience, Mary Karr’s The Liars’ Club, Mary McCarthy’s Memories of a Catholic Girlhood, Tobias Wolff’s This Boy’s Life … It’s not a genre that I’ve turned to that often, really. In general, I go to memoir for a literary experience, not to find out about a life. Another, which I would almost call a first-person biography, is An American Childhood by Annie Dillard. That both is and isn’t an impersonal memoir. I reread it recently with my students because I was teaching a whole course devoted to Annie Dillard, and it’s really a remarkable and at times inscrutable book.

INTERVIEWER

Was there any change in how you saw your younger self by the time you finished writing the book?

DYER

I feel very close now to my fourteen-year-old self, but that’s a path that my writing had been taking anyway. The humor in my later books is sometimes very adolescent, which strikes me as a good sign—immaturing with age.

Sophie Haigney is the web editor at The Paris Review.

June 16, 2025

“Everything is Enchanted”: Andy Kaufman and Paul Reubens

Left: Andy Kaufman as Latka Gravas in Taxi, 1979. Public domain, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. Right: Paul Reubens as Pee-wee Herman, 2009. AP Photo/Danny Moloshok.

Andy Kaufman and Paul Reubens both appeared on the hit TV show The Dating Game, but not as themselves. If you had tuned in on a Wednesday night in 1978, you might have seen a rather weird bachelor amid the usual roll call of dudes with disco medallions. While the other contestants were all throwing scripted innuendos at one lucky lady, there was Andy Kaufman! Except it wasn’t him, not exactly. He had shown up as his squeaky-voiced Foreign Man character, Latka Gravas, whom he would soon make famous on NBC’s show Taxi (1979–1983. But no one knew who that was yet. On the show, it all got pretty discombobulating. He was grinning like a boy who’d just discovered what fire could do to his Action Man; he deliberately misunderstood the jokes, and squealed “I won!” when he didn’t win, all somehow earning him the gleeful indulgence of the studio audience. What the hell was that?

A year later, a certain Pee-wee Herman was on the same show, a then-unknown overgrown boy in a glen plaid suit and red bow tie, played by a twenty-seven-year-old actor called Paul Reubens. Looking like Buster Keaton’s unhinged son, sounding like a hyperactive imp on a sugar high, he had the audience giggling like drunk hyenas soon, too. Crashing The Dating Game wasn’t some sort of elaborate scheme Andy and Paul hatched together, but it’s nice to think about them in split screen: two cartoonish instigators of live-action anarchy, tricksters without any malicious purpose, making comedy out of these unusual characters.

It’s a good time to investigate the paradoxes and special strangeness of Kaufman and Reubens, who are oddly alike in some ways and so different in others. Two fascinating new documentaries try to puzzle out the stories of these two much-missed entertainers. (Reubens died at age seventy after a battle with cancer long-kept secret, in 2023; Kaufman died of lung cancer in 1984, when he was just thirty-five.) Matt Wolf’s Pee-wee as Himself and Alex Braverman’s wacked-out portrait of Kaufman, Thank You Very Much, provide the best accounts of what powered their singular shenanigans, not to mention the trouble they got themselves into once they crash-landed in the world of showbiz.

Personally, I like to imagine a documentary about both of them. Or a great buddy movie, maybe with Nicolas Cage as Andy and Timothée Chalamet as Paul. Two Inscrutable Jews! Andy Kaufman from Great Neck, Long Island, and Paul Reubens from Sarasota, Florida. Two oddball products of Eisenhower-era suburbia, who spent their childhoods in staring contests with the TV, bewitched by fun-for-all-the-family entertainment: The Howdy Doody Show, I Love Lucy, The Little Rascals. Kaufman, the Philip Roth–level satyr with a sweet tooth (“He was kind of a sex addict,” his former partner Lynne Margulies cheerily remembers in the documentary); and Reubens, the willowy boy who dressed up as a princess on Halloween.

In a 2009 chat with Reubens for Interview magazine, Paul Rudd observed the Kaufman-esque vibe of that Dating Game appearance and wondered whether he was an influence. “I was very influenced by him. I liked his work, and I knew him a tiny, teeny bit,” Reubens said. I couldn’t find any quotes of Kaufman talking about his contemporaries. That wasn’t really his style.

But among other things, Andy Kaufman may have been the architect of Reubens’s Saturday morning TV masterpiece, Pee-wee’s Playhouse. Kaufman made a six-minute skit called “Uncle Andy’s Funhouse” for the TV show Buckshot in 1980. Kaufman’s best friend and coconspirator, Bob Zmuda—a man who used to run around the Central Park Zoo with Kaufman, screaming, “The lion’s out!”—once called it “a kids’ show for adults” that never got made into a full-grown show. An IMDb trivia page claims that before he died, Kaufman approved of Reubens mutating the Funhouse into the Playhouse before he died. While the formats are similar, the two shows are weird worlds unto themselves, two “houses” that are alike in their eccentricity but it may be the only contest where Kaufman comes out looking slightly more “normal”: he runs upstairs in a hula skirt to yell at his parents (actors); Pee-wee chats with a talking globe. They’ve both disappeared into characters that seem to have beginnings and no ends.

***

Inscrutability can be a performer’s best friend—it makes everything more real and unpredictable—but Kaufman’s and Reubens’s careers also offer lessons in its potential risks and pitfalls. In the interviews with Matt Wolf that make up Pee-wee as Himself, combined with thousands of hours of material from Reubens’s personal archive, Reubens comes off as, yes, a total sweetheart and a congenital mischief-maker, teasing and bedeviling Wolf at every turn. It’s wild fun to watch, but you also know he’s also hiding things he feels the need to conceal, including the cancer diagnosis he kept secret from the public and from Wolf. Previously deeply private about his sexuality, he discusses his deep romance with the handsome painter Guy Brown before the creation of Pee-wee. Severely freaked out by how he “lost [his] entire personality by being involved with someone else,” he swore off any long-term romantic relationship, dedicating himself to his career. His famous creation materialized not long after, partially shaped by Brown’s mischievous spirit. But Reubens was in love and ached from the loss. He’s close to tears when recalling Guy’s death from AIDS-related illness four decades earlier.

Reubens also admits he’s quite the control freak, and secretive as a Cold War spy. “I’m not a trusting person,” he tells the director, straightforwardly. Fathoming the reasons for this isn’t exactly rocket science. “My career,” Reubens observes, “would have absolutely suffered if I was openly gay.” Eventually, he stops cooperating with Wolf on the documentary, uncertain about whether it will tell the story he wants, keen to shape the entire thing himself.

Maybe Reubens is sometimes coy because he’s baffled by the inexplicably charmed story of Pee-wee Herman. The character was solid gold right from the beginning, a hit with audiences as soon as Reubens slipped into the outfit he found in a cardboard box backstage at the Groundlings headquarters. He was ready to show you his cool toys, offer wisdom (“I was using my imagination. I was being creative. You can do it at home, too”), cackle with glee, or yell a snotty playground insult: “Act your age, not your IQ!” By 1981, he was the star of a sellout show. De Niro and Scorsese came to check it out one night, maybe taking notes for The King of Comedy (1982).

Soon he was a real pop-cultural phenomenon, he was on on school lunch boxes; he was a doll you could get for Christmas. But in retrospect, none of that success seems to have been guaranteed. Reubens was a CalArts alumnus enthralled by the Warhol superstars. After college he was all set to join an offshoot of the legendary anarchist drag collective the Cockettes. He played a “mermaid version of Cher” in a trippy video long before Cher appeared in a movie called Mermaids (1990). In Super 8 footage of Reubens as a stoned sylph wreathed in sequins and fur, experimenting with various drag looks, it’s giving Rrose Sélavy via Peter Hujar. He referred to his Pee-wee act as “performance art” plenty of times.

And then there’s the matter of his two arrests: the first for public exposure in a Florida porno theater while Pee-wee’s Playhouse was on hiatus in 1991; the second on trumped-up child pornography charges in 2003. He owned a vast quantity of vintage erotica, much of it stashed in unopened boxes. Keen to make headlines during election season, the LAPD desperately isolated one potentially ambiguous image out of thousands and tried to skewer him with one count on the reduced charge of obscenity. Reubens protested his innocence in both cases and pled no contest.

You might say he became a victim of his own too-successful character. Reubens was wholeheartedly invested in and identified with being Pee-wee, almost never interviewed or making any sort of public appearance out of character. Wolf’s documentary includes footage of Connie Chung referring to Herman’s lawyer in a news bulletin, as if the character had been arrested, Reubens not even mentioned. The wicked dissonance between the public sprite and the meth-lab Gandalf in his infamous Florida mug shot felt acute indeed. Was it Borges or Liz Taylor who said, “Fame is a form of incomprehension, perhaps the worst?”

And indeed, forty years later, nobody seems to know who Andy Kaufman really was, either, not even Zmuda. Remembering Kaufman from our own deranged present in Thank You Very Much, Zmuda says, “It was like working for Harry Houdini. They weren’t jokes, they were illusions.”

Kaufman was a great actor: fearless, able to convince you he really meant whatever he did. And yet he didn’t seem interested in playing anybody that didn’t come out of his head. But that’s a flaw only if you’re interested in the usual way of doing things. It’s fun to imagine Kaufman doing what Reubens did in Blow (2001), for example, and giving a sly and sensitive performance as a campy, drug-trafficking hairdresser. But maybe he would’ve shown up as somebody who wasn’t even in the script, just for fun. Why does the performance have to stop “here” rather than “there”? And decided that, anyway?

If Kaufman felt that what he was up to was performance art, of course, he wasn’t telling. There’s no record of him talking about Fluxus; there’s just his friend Laurie Anderson in Thank You Very Much telling the story of hanging out with him at a Coney Island funfair and deliberately antagonizing ferocious carnival workers. Performance art, a goof, a mad risk, or all of the above. He went on TV and told David Letterman about three men who’d mugged him recently, and announced he was going to adopt them as his adult sons. Or he slow danced with his beloved Grandma Pearl. Maybe it was just a private game he was playing, and he was totally untroubled by anything other than his own personal definitions of success and failure. Consider this scene from Julie Hecht’s account, in her book Was This Man a Genius? Talks with Andy Kaufman (2001), of trying to profile him for Harper’s Magazine at his peak, circa 1979. It sounds like hanging out with Don Quixote. Author and subject show up at a Manhattan restaurant just before closing time. He tells the maître d’ they have a reservation, but in the voice of a fusty aristocrat.

“I’m very sorry but I just phoned and was told I would be served if I arrived before one.”

“It is almost one now,” said the maître d’.

Sir Andrew of Kaufmanshire retorts in his faux-British accent, “Almost—but not yet one.” Dinner is served. Robin Williams noted on the 1995 TV special A Comedy Salute to Andy Kaufman, “Andy made himself the premise, and the world was the punch line.”

***

Does anybody else feel high? Perhaps it isn’t a surprise to learn that Reubens and many members of the production design team on Pee-wee’s Playhouse were sustained by plenty of Cali weed. The set for the show was one of the great artworks of the eighties. Every inch was psychedelic, from the acid-flashback patterns in the carpet to the butterscotch-colored sphinx on the roof, which was designed by the William Blake of LA’s punk artists, Gary Panter. Pee-wee is talking to a hot Black cowboy who was in Apocalypse Now. (Laurence Fishburne!) Ah, the walls are melting. Is Chairry a mint-green talking chair or a mint-green talking hippo? Every episode’s secret word makes the whole set explode (“Fun!”), just like when you and your pals get tickled into Jell-O by a stoner in-joke.

Meanwhile, led astray by too much On The Road in his teens, Kaufman ran away from home and spent a year living in a Long Island park, transmogrifying from nice boy to wastoid on a diet of brain-frying substances that would’ve spooked Dennis Hopper. LSD, DMT, STP, Dexedrine, rivers of booze “every day!” as he recalled in an interview. “Every day!” Luckily, Transcendental Meditation tweaked those brain waves to a different frequency, and from 1969 onward, he was almost a parody of a new age person in his squeaky-clean disavowal of anything remotely “toxic.” (Except when he was being his lounge singer alter ego, Tony Clifton, bellowing like a hungover sea lion—then it was time for cigarettes and whiskey.)

Pretty much everything Kaufman did was trippy, though, because he messed with the whole concept of funny. Once, at a comedy club, he ate a bowlful of chocolate ice cream onstage. The act was the classic Cheshire Cat switcheroo: the normal way of doing things was suddenly revealed to be nonsense. You could toil for years to nail three minutes of sassy one-liners, or you could go somewhere can name. Like Syd Barrett asked, “What exactly is a joke?”

At the same time, much of their material was uncannily familiar. Reagan was in the White House and everybody was getting flashbacks to the fifties. Cute surfaces, strange depths: all-American aesthetics rendered darkly or sweetly perverse. David Byrne wandering around Texas in a Stetson like a Martian at a barbecue in his movie True Stories (1986). The Norman Rockwell suburbs seething with psychosexual nightmares in Blue Velvet (1986). Cindy Sherman, the all-American girl from Glen Ridge, New Jersey, mutating every time she raided her dress-up box. Was she a scared bobby-soxer or a femme fatale from a film noir that you half remember? Pee-wee materialized with a delicious party bag full of chaos. What was he up to? Like Kaufman, he was creating demented echoes of his childhood programming, equal parts vaudeville and avant-garde, simultaneously wholesome and weird, a heartwarming tribute to tradition and a sly parody of it. Look at Kaufman lip-syncing to the theme song from Mighty Mouse: “Here I come to save the day!” Or see the touching spectacle of Kaufman talking with Howdy Doody on his 1977 special Andy’s Funhouse, as if the puppet were a real person: “The first friend I ever had.” If they make you feel like you’re zonked on psychedelics, it’s partly because they crack open a portal to a certain childlike wonder. It’s a world in which, as Glenn O’Brien pointed out in his epic exegesis on Pee-wee for Artforum, “everything is enchanted.”

As soon CBS gave Reubens the green light, he was on a mission. He tells Wolf that he knew at once that “I can be the beacon of being like, It’s okay to be different.” No big deal was made out of the fact that the cast was multiracial at a time when this was extremely rare. When Reubens confesses “there was gay subtext in Pee-wee’s Playhouse,” he can barely hide his mirth: a big reveal of the most obvious thing in the world. Who’s that knocking at the cherry-red door at the height of the ultrahomophobic Reagan era? A who’s who of LGBTQ royalty: Cher! Grace Jones! Little Richard! And that’s just the Christmas special. It was kind of radical, given that the president didn’t even say the word AIDS until 1985.

As gentle as he could be, Kaufman had a compulsive appetite for creating scandal and confusion that was baffling then and would be career suicide now. The man who canceled himself! A troll before troll meant that. He got himself voted off SNL for being so infuriating. Imagine somebody today publicly seeming to turn their comedy career into a side hustle while they become the “Inter-Gender Wrestling Champion of the United States,” a loudmouth schlub who insists he fights only women on various TV wrestling franchises, taunting the audience, feasting on their boos and getting rewarded with a hailstorm of popcorn and Coke.

Everybody’s grown familiar with the concept of actors staying in character off set but this was way before all those stories about Daniel Day-Lewis making his own canoe for The Last of the Mohicans. You’re falling fall through a whole other trap door when you remember that Kaufman caused all this trouble as “Andy Kaufman.” It’s not as if many people were even in on the joke. The actress Carol Kane told me that after he was pile-driven by Jerry “The King” Lawler during a wrestling match and bundled off to the hospital, the cast of Taxi “thought he was actually in [the] hospital, and we sent him magazines and fruit baskets. And then Danny [DeVito] watched the tape of the match and slowed it down—it was fake!”

Some people still think Andy Kaufman isn’t dead. He’s been sighted, among other places, at a Walmart in New Mexico. Zmuda cryptically suggests that “if he wasn’t dead, he’d be faking his death.” Is he secretly watching Nathan Fielder’s reality-mangling antics on The Rehearsal and giggling with approval? Why did he work as a busboy while he was on Taxi? He was like some mythological creature that exists just to bewilder people and bask in their responses.

Underneath all the chaos, there may have been peace, maintained by a deep internal purpose. Thank You Very Much points out the influence of Transcendental Meditation: The straitjacket of the self does not exist. Rather than lamenting what you supposedly are, explore what you could be, whether that’s Elvis, a wrestler, or somebody who screams “You’ll Never Walk Alone” while thrashing a hi-hat on The Mike Douglas Show. Forty thousand dollars is only a financial loss; it doesn’t mean real failure. Accept good or bad reactions as beautiful in their own way. “Let be be finale of seem,” in the words of Wallace Stevens, but in front of a live studio audience, ideally. “He was so courageous,” Kane told me, “because he never broke character. He was so honest and true to whatever he wanted to construct as an artist. He never let on. He never winked.”

***

I called Kane, the sui generis Upper West Side Good Witch from such classics as Scrooged (1988), Carnal Knowledge (1971), and Addams Family Values (1993). She knew them both. She acted with Kaufman as Latka’s girlfriend, Simka, on Taxi, and was pals with Reubens for years, stepping out with him for his first public appearance in LA following his infamous Florida arrest. They had dinner at a restaurant; the press was there. “Paul arranged it all,” she said. “He did it very elegantly.” Happily recalling Kaufman, she said, “He felt that rehearsal was not the best thing for his particular process. During the week you had to rehearse with a young man with a cardboard sign around his neck that said andy on it. He was a lovely young man but the chemistry wasn’t the same.”

How were Kaufman and Reubens alike? Were they alike? “Kindness,” Kane said, “is something they had in common.” Giving people delight is a very generous act. See Andy’s wide-eyed boy-at-the-carnival glee when he’s chatting with Orson Welles on The Merv Griffin Show. He was a goofy kid from Great Neck, and now he’s talking with a legend as if he were talking to his grandpa. There’s footage of him, toward the end of his life, greeting a happy crowd at the Improv in Los Angeles. He’s the cheeriest person you’ve ever seen in a punk leather jacket and a Travis Bickle Mohawk. (And probably the only person whose Mohawk was concocted from post-chemotherapy hair.)

In the heartrending audio that concludes Wolf’s film, recorded by himself the day before he died, Reubens declares that his work as Pee-wee was “based in love and glee.” Kane said, “Paul was one of the sweetest people on the face of the earth.” The sweetest moment in Wolf’s documentary comes when we see Reubens as Pee-wee at the 1991 MTV Video Music Awards. “Rave response” would be an understatement of the audience’s reaction. He tries to goof with the crowd, telling them again and again, “Shut up! Stop!,” but the roar keeps coming. An expression moves across his face that isn’t an especially Pee-wee one: he’s touched, as if he’d just stumbled into a huge surprise party being thrown in his honor. But he recovers and asks, in that trademark whine, “Heard any good jokes lately?”

Kane told me her two old friends “were magical, both of them, in different ways.” Different brands of magic; similar kinds of spells. They conjured up wild new spaces to perform inside where things were multicolored, discombobulating, hysterical. Just like in the theme tune for Pee-wee’s Playhouse, “you’ve landed in a place where anything can happen,” and you can make it into your home. Magical indeed.

Charlie Fox is a writer and artist who lives in London. His book of essays, This Young Monster, is published by Fitzcarraldo Editions. He curated Flowers of Romance for Lodovico Corsini in 2024.

June 13, 2025

Miss Bingley’s Burberry Bikini

Mia Goth’s eyes look naked. In every image, no matter how many times this face is reproduced, the vulnerability startles. Doe-eyed, doll-eyed, fair brows, hardly any visible lashes, she is sweetness in a rancid world and, in Autumn de Wilde’s 2020 adaptation of Emma, my favorite Harriet. She may deviate from some of the specifics of the Harriet that Jane Austen writes in Emma. Her eyes are brown, whereas Harriet’s are blue. Goth is not plump, but she is soft. It’s through Harriet that Austen writes the soulfulness that undercuts her story’s satire. This is what Goth delivers—Harriet’s “flutter of spirits.”

Being a Regency-era gentleman’s “natural child,” Harriet never had the privilege of innocence. Not knowing whose daughter she is, she has had to be okay with the unknown—a foil to Emma’s need to be in control. Goth shares a likeness with Brittany Murphy, whose Tai is Harriet’s proxy in Clueless. Both actresses are bubbly, blissful, but present to the universe’s darkness—it’s not the same as being naive, even if the qualities are sometimes confused. While there’s no bloodshed in de Wilde’s costume drama, Goth brings something from her scream queen résumé: her ability to edge between purity and madness. She plays Harriet with an openness to the intensity of desire and an appreciation of its absurdity

There’s a tabloid soap opera that Goth’s casting conjures, her real-life entanglements mirroring an Austenian plot tailor-made for TMZ. In 2018, seventeen months before the Emma remake’s release, when Goth was promoting a film with Robert Pattinson, their respective exes Shia LaBeouf and FKA twigs were in the news for being photographed together. “Awkward,” reported People. LaBeouf and FKA twigs eventually broke up (there’s an ongoing lawsuit about his alleged abuse of her), and LaBeouf and Goth got back together. Today, they’re married. Like Harriet, maybe Goth could have played her hand differently and landed a better match. Harriet wedded a farmer, Goth a canceled movie star. On both fronts, you could say, in the end love won—but at what cost? Austen is a cynic, after all.

—Whitney Mallett

We will never be free from Pride and Prejudice. Its tale of class-traversing romance has remained so ardently with us that Darcy and Elizabeth’s love has become the blueprint of a type of romantic narrative itself. For over two centuries, every weird, pretty brunette in art and literature (her beauty always orthogonal to her braininess) who has received great romantic providence has been a daughter of Lizzie Bennet. We would have no horny One Direction fan fiction without Pride and Prejudice; there would be no Fifty Shades of Grey, most definitely no Twilight; it’s likely that brunettes would possess none of the cultural purchase we enjoy now had Jane Austen never given it to us.

We certainly wouldn’t have Bride and Prejudice, Gurinder Chadha’s 2004 Bollywood adaptation of the 1813 novel and perhaps my favorite thing to come out of Austen’s infinitely elastic multiverse. Much of its success is owed to Aishwarya Rai, whose perspicacious Lalita Bakshi (the movie’s Lizzie Bennet) is perhaps a woman of greater beauty than Austen intended. In the book, Lizzie is a little plain; her “fine eyes,” as Darcy puts it, are her primary attraction. Casting Miss World 1994 as the second-prettiest sister would make the metaphysics of their romance totally unrecognizable were it not for the racial difference that Chadha’s adaptation introduces into it. It doesn’t matter that Rai is Bollywood’s Bellucci with limpid green eyes, nor that her brown hair is dyed a curious auburnish shade in the movie—she’s not white, and Darcy is, so her generational beauty is still relegated to the status of subaltern brunette.