The Paris Review's Blog, page 733

February 26, 2014

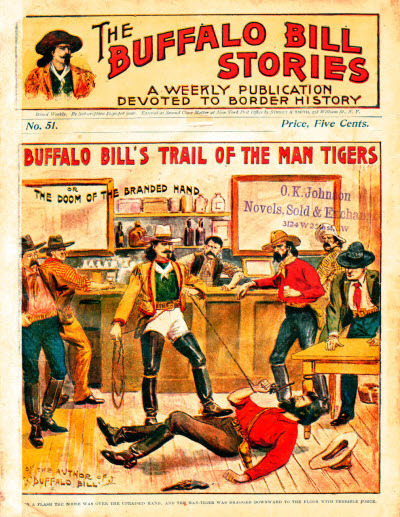

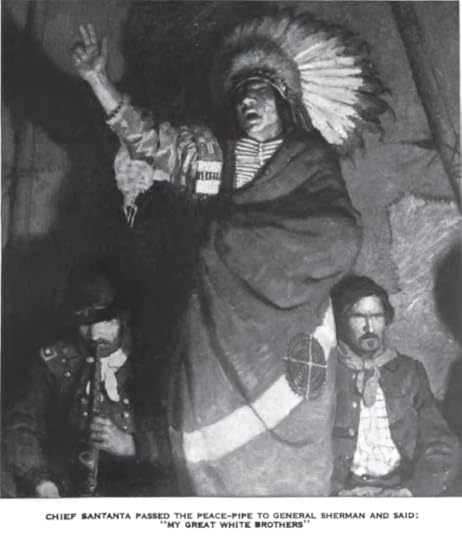

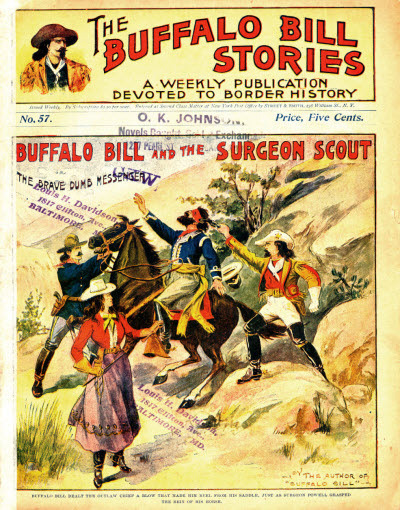

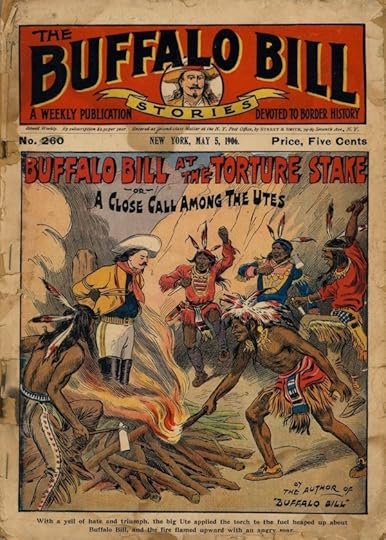

Best Western

Happy Birthday, Buffalo Bill.

Postcard, Courier Lithography Company, ”Buffalo Bill” Cody, 1900, National Portrait Gallery, via Google Art Project

“Buffalo Bill's Last Scalp”, Ornum and Company’s Indian Novels, 1872

No one did more to shape our concept of the American West than William Frederick “Buffalo Bill” Cody, the hunter, would-be cowboy, and showman whose traveling revue, “Buffalo Bill’s Wild West and Congress of Rough Riders of the World,” helped create the dime-novel image of frontier life that persists to this day. Cowboys, injuns, tipis, headdresses, firewater, peace pipes, weathered wide-brimmed hats, fearless feats of derring-do, stagecoach heists, impossibly accurate gunplay, bucolic campfires, tremulous harmonicas, bareback rides across windswept prairies, vast herds of grazing bison, virile stallions, lawless lands, hootin’, hollerin’, spectoratin’—the whole whooping metaverse came straight out of Bill’s fringed leather pockets. Today, his story exists in a kind of liminal space between history, mythos, and stagecraft; no one really knows what’s true and what isn’t. But however he lived, the dude gave us the Western, and he reminds of simpler times. He staked his massive celebrity on the speed with which he could dispatch a herd of buffalo—think about that.

These illustrations pay fitting tribute to the Buffalo Bill zeitgeist: its bumptious individualism, its rugged sense of adventure, and, yes, its racial insensitivity. Except where noted, they come from the first of his two autobiographies, 1879’s The Life and Adventures of Buffalo Bill, and from Buffalo Bill Stories, “a weekly publication devoted to border history” from the early twentieth century. As bigoted as some of these images are, though, it’s worth noting that Bill hired many Native Americans to tour in his troupe—“show Indians,” as they were pejoratively known—and he shared in their horror as the West he knew was tamed, subdivided, denatured, and “civilized.” Quoth Wikipedia: “He called [Indians] ‘the former foe, present friend, the American,’ and once said, ‘Every Indian outbreak that I have ever known has resulted from broken promises and broken treaties by the government.’”

A Millionaire’s Money Can’t Buy

Photo: nikoretro, via Flickr

“I didn’t even know you could still get that!” exclaimed a rather fabulous looking tiny woman in a turban and plaid coat. I had ordered a date-nut bread sandwich with cream cheese. We were on line at the Chock Full o’ Nuts kiosk located in my neighborhood Gristede’s.

This supermarket is notable partly for its mysterious principles of organization: spices, for instance, can be found in three different aisles in the store. When I need something that defies obvious shelving classification—liquid smoke, say, or rice noodles—I come here, just to challenge myself. (In those two cases, I failed and ended up having to ask for help. The items were in, respectively, the salad dressing and “International Foods” sections.)

Anyway, I had gone to the Chock Full o’ Nuts to get my usual: the “Chock Classic” sandwich, a bargain at $2.99, so rich and filling that it extends to at least three small meals. (For the uninitiated, the business did start as a nut stand in the twenties. A few years ago, Chock had to add the slogan “NO NUTS! 100% Coffee” to its packaging.) The sandwich was an economical standby on the menus of the restaurant chain, which used to be all over New York, and now serves as a reminder of Chock’s glory days. It was this that caught my neighbor’s eye.

According to Arthur Schwartz’s magisterial tome New York City Food, CFoN wasn’t just notable for its low prices, cleanliness, catchy jingle, and high quality. The stores were also known from the beginning for their integrated staff.

[William] Black, a Jew, who is said to have deeply felt the anti-Semitism of New York City in his youth, was an early activist for racial equality. He focused the public’s attention on this in 1957, when he hired the retiring Brooklyn Dodgers star, Jackie Robinson, who had broken the color barrier in baseball. As head of personal and community relations, Robinson became vice president of the company.

The famous Chock Full o’ Nuts café policy of no tipping stems from Black’s views on equality. He thought tipping was degrading. He preferred to pay a fair wage, and he gave his employees a health plan, which was revolutionary for restaurant workers.

Black, an immigrant, had founded Chock because discrimination kept him from finding work as an engineer. After his success, he became a philanthropist, donating then-record sums toward medical research. The chain was sold after Black’s death, the restaurants closed, and, long story short, Chock now belongs to another company. They brought back small cafés a few years ago, selling coffee and pastries. On the otherwise modern (and somewhat dismal) menu, the sandwich is an anomaly, but it’s worth seeking out as a good-value snack, even if your money is now going to Massimo Zanetti Beverage USA. Oh, and you may now tip.

Once I had confirmed the continued existence of the sandwich to my neighbor on line, we got into an enthusiastic discussion of date-nut bread, the chain (she was a regular in the fifties, when she worked as a secretary in Midtown), and New York generally.

“They’ll have to drag me out in a body bag,” said the woman, Doris. “No one’s getting me to Miami!” Which seemed like an attainable goal, as these things go.

Out of earshot of the teenager who worked there, I mentioned to Doris that I didn’t think the current iteration of Chock was very good.

“Awful, awful!” she agreed cheerfully, eating a cheese Danish with relish. “But everything is different now, right?”

When I got home, I read up a little on Chock Full o’ Nuts, and saw the following on Wikipedia: “The current youngest franchise owner is Corey Torjesen of Staten Island, New York, who opened a Chock Full o’ Nuts franchise at the age of nineteen with his own money, which he saved up from a newspaper route.”

I am, as I write this, eating a Chock Classic.

Elliptical Orbit: On Mircea Cartarescu

In the summer of 2011, I spent every afternoon Google-mapping the Chicago neighborhood where I grew up. I pulled the shades down, turned the air conditioner up, and typed the intersections that define Back of the Yards—named for its proximity to the Union Stockyards—into the search box. I was in the early stage of a nervous breakdown, obsessively attempting to revivify the past, the only place where, I believed, continuity existed. Fifty-First and Loomis was my embarkation point: the intersection where our family doctor’s office was located. An unfilled prescription, from 1965, that I’d found in my deceased mother’s jewelry box provided the office’s address. My mother and I had had a contentious relationship, but that summer I fantasized about opening her grave and throwing her skeletal arms around me—“I thought even the bones would do,” to quote Plath. I used the objects from the jewelry box (grocery lists, a Revlon “Moondrops” powder compact, old Sears charge cards, blue crystal rosaries, a Coty lipstick) to reconstruct her existence, and finding that prescription was like finding the key to a long-locked door.

Going to the doctor had been a kind of family outing—every three months, to get my grandmother’s diabetes checked—and I wasn’t sure if I had dreamed those odd excursions to that tiny office. My mother would go downstairs to get my grandmother dressed: clean hairnet; heavy girdle and thick support pantyhose; rhinestone brooch; nice dress instead of a stained shift; black orthopedic shoes instead of house slippers; and dentures, from the glass on the bathroom sink. Then she’d run upstairs to get my sister and me ready, dabbing Chantilly perfume on our wrists.

Uncle Stas would drive us there, my sister and I in the backseat with our grandmother between us, our mother in the front, arguing in Polish with Stas during the five-minute (yes, five-minute) drive. Now, as I looked at the office on Google Maps, I saw that the front door and windows were boarded up and noticed a bright, transparent smudge in the doorway. I knew that the smudge was the result of the camera having been in motion when the photo was taken, but I felt that that smudge was my soul: intense remembering had projected it back there, and it had been captured between the boards over the waiting-room windows, behind which my sister still sat next to my mother, pointing at ads for Catalina swimwear in the big Look magazine open on their laps, next to my grandmother with her legs crossed primly at the ankles, clutching her purse, next to my uncle grinding his cigarette out in a tall, metal ashtray stand.

I’d felt slightly ashamed of my retrieval attempts. Wasn’t I just wasting time and beating myself up over the bad relationship I’d had with my mother? And how would this indulgence in nostalgia benefit me as a writer? With forty years’ experience as a poet, I was pretty adept at translating difficult experiences into language, but where would I go with this one? It seemed that the only way to go was toward memoir, though I’ve never really been a fan. (Yet another grandmother story?) Still, I felt compelled to follow the trail of images (into darkness, it seemed), and my intuition—still functioning despite the roadblock of anxiety—kept calling to me to pay attention.

Had Blinding, Mircea Cărtărescu’s apotheosis of remembering, been available in English back then (as it is now, newly translated by Sean Cotter), I would have found in it a guidebook—a grimoire, really—for the journey. The book begins as a multilayered memory-mapping of the narrator’s Bucharest childhood but becomes something much larger and more complex. For starters, Blinding is the first volume, subtitled “The Left Wing,” of a 1,352-page trilogy. Together, the three books form an image of a butterfly: two wings and the abdomen, the left wing having a feminine nature corresponding to one’s mother, the right wing a masculine one corresponding to the father. In discursive sections interposed between the forward-moving (though dreamlike) plot, the narrator, also named Mircea, soliloquizes on the idea that all of us bear, in our bodily frames, the indelible stamp of our dual origin, existing “between past and future like the vermiform body of a butterfly, in between its two wings”; and, he writes, “one gesture in childhood takes up more time and space than ten years of adulthood.”

How revelatory it felt to read that. I’d recoiled from describing in both my poetry and my fiction the two-flat on Racine Avenue that my great-grandfather had built after he’d arrived from Poland in 1908 and where my grandmother, my mother, and I had all grown up, even though moments lived there years and years ago were still clear and present, even magical. I had steadfast memories, for instance, of my dad prying open a heavy sewer cover, oddly located next to the steps on our side of the house, and the two of us gazing into the moving waters as a dead lady in a wedding gown floated by. Or rifling through my grandmother’s dresser in her dark, musty bedroom and finding a small box containing an object so strange I risked revealing my illicit activities to find out what it was (according to her, a thorn from the Crown of Thorns: “I was so sick, Polish priest give me”). Or watching (did I dream this?) as she made a rainbow appear over an old wooden bowl full of rainwater collected for three weeks from between a trio of evergreens in the front yard. How could I flow those images into form, and keep their odd resonances?

Mircea, the narrator, provides just such a model for mapping the remembered/dreamed geography of childhood:

I had moved to the block on Stefan cel Mare when I was five, and the immensity of its stairways, hallways and floors had given me, for some years, a vast and strange terrain to explore. I went back there many times, in reality and dreams, or better put, within a continuum of reality-hallucination-dream, without ever knowing why the vision of that long block, with eight stairways, with the mosaic of its panoramic window façade, with magical stores on the ground floor: furniture, appliances, TV repair—always filled me with such emotion. I could never look at that part of the street with a quiet eye.

Reading that, you might think Blinding is a memoir. It does partake of some features of memoir, but its method of remembrance is chimeric. Its many linked stories, for example, are the imagined memoirs of characters other than the narrator, in particular Mircea’s mother, Maria. She is an artus figure in this feminine “wing” of the trilogy: her story narrates, contains, and launches the stories of other characters; she is both a ghostly and wholly palpable presence. When I saw Cărtărescu at a release event for the English translation, he mentioned that wherever he lacked information about his mother, he envisioned it. In an early section, the narrator Mircea “en-visions” his mother, via her dentures, on a twilit Bucharest street:

“Ah, Mamma,” I whispered in the crazed silence. I stared at the dentures for a few more minutes in the darkening light, until the dusk turned as scarlet as blood in veins, and the dental appliance began to glow with an interior light, as though a gentle fluorescent gas had filled the curved rubber gums. And then my mother formed, like a phantom, around her dentures.

Scenes like this make it easy to believe that words working in the service of imagination can make the dead live again.

I prefer Blinding’s Romanian title, Orbitor, because it contains the word orb, which suggests what both the narrator Mircea and I are doing: lingering, in our memories, around an earthly place (Mircea in Bucharest, me in Back of the Yards), just as an orb—a term used by ghost hunters to indicate a spirit—might be observed doing. The Romanian title is also suggestive of the way the mind’s eye instinctively gravitates toward certain places, like a planet around the sun:

Everything is strange, because everything is from long ago, and because everything is in that place where you can’t tell dreams from memory, and because these large zones of the world were not, at the time, pulled apart from each other. And to experience the strangeness, to feel an emotion, to be petrified before a fantastical image always means one and the same thing: to regress, to turn around, to descend back into the archaic quick of your mind, to look with the eyes of a human larva, to think something that is not a thought with a brain that is not yet a brain, and which melts into a quick of rending pleasure which we, in growing, leave behind.

If the invention of writing changed storytelling forever (rendering memory unnecessary), then a written work in which poetry gives rhythm to action (to paraphrase Rimbaud) can return readers—and writers—to a place where memory’s instructive and restorative functions can be learned and utilized. For me, that bright smudge in the doorway might have been my soul yearning for a look into the past, but it also might have been me trying to scry a way into a kind of writing that begins in memory but opens out into something much larger and more sophisticated, something both ordinary and extraordinary—like childhood itself.

I remember one hot, bright day from the summer of 1969: the wind had shifted direction and a breeze bearing the hideous stink from the stockyards blew toward our house. My mother, her hair in pin curls under a polyester babushka, flew down the porch stairs, screaming for my sister and I to help her pull the sheets off the line and hang them in the basement (she preferred they’d smell like the damp basement rather than dead flesh). We protested because we were busy playing “moon landing”: our red wagon was the lunar exploration module and the yard was the moon’s surface. But I noticed that if we stood between the sheets and looked up, squinting, as Ma whipped them off the line, the sun, directly above us, would flash in colored lightning streaks. And if we closed our eyes tight, we’d see negative images of the sheets and the trees behind our eyelids. We were no help that day, but that night, in our beds, we talked endlessly about our discovery: that ordinary things like bedsheets and sunlight and eyes (and as I later learned, unfilled prescriptions) can be keys to extraordinary places.

Sharon Mesmer’s most recent poetry collections are Annoying Diabetic Bitch (Combo Books) and The Virgin Formica (Hanging Loose Press). A selection of her flarf poems appears in the second edition of Postmodern American Poetry: A Norton Anthology. She teaches creative writing at NYU and the New School.

Snuffing Out Anachronisms, and Other News

Not so fast, Abe. Image via Anachro.net.

“The Cotton Club was also shooting in New York. The night we were shooting the Marshmallow Man, some guy said to me, ‘This is insane, what’s this movie?’ I said, ‘The Cotton Club, man. That guy Francis, you can’t stop him.’” In honor of Harold Ramis, an oral history of Ghostbusters.

What do you do when your students’ literary touchstone is Law and Order: SVU ?

Online, Steven Soderbergh has released Psychos , “a feature-length mashup of Hitchcock’s original 1960 movie and Gus Van Sant’s controversial shot-for-shot 1998 remake.”

At last, screenwriters can stop anachronisms in their tracks with the Anachronism Machine. “It maps the script’s words and phrases against a Google database consisting of the full texts of six million books and spits out a graphical rendering of the likely anachronisms the script is guilty of.”

The first entry in an A to Z of forgotten books: “When it appeared in 1923, André Maurois’s Ariel was one of a new breed of what reviewers of the time took to calling ‘romance biographies.’”

February 25, 2014

The Great Round World and What Is Going on in It

Excerpts from the February 25, 1897 edition of The Great Round World and What Is Going on in It, a “weekly newspaper for boys and girls” published in New York.

There is a little flurry in Siam.

The Czar of Russia is quite ill, and every one feels sorry that he should be sick now.

Did you ever see a house move? If you have not, you have missed a very funny sight.

A great sea monster has been washed ashore on the coast of Florida, and men who study natural history are much interested in it.

At last active measures are about being taken in reference to the terrible Dead Man’s Curve.

For some time past the Fire Department has been seeking for some engine powerful enough to throw water to the top of the very high buildings—the skyscrapers, as they are called.

We gave an account, in an earlier number, of Lieutenant Wise and his efforts to make kites strong enough to lift soldiers into the air.

Katonah has a railroad depot, and a post-office, and thinks a good deal of itself.

The strikers have been beaten because of their lack of money.

This plague is supposed to attack only the dirty and unwashed, and as the majority of these pilgrims are filthy beyond description, it would be certain to fasten upon them.

All the Parts Combined

Diagram from the Colt Revolver patent, 1836

178 years ago today, in 1836, Samuel Colt was granted a U.S. patent for his revolver, which he called “a new and useful Improvement in Fire-Arms,” those most brutally useful of devices. As EDN (Electrical Design News) noted last year, Colt’s design “was a more practical adaption of Elisha Collier's earlier revolving flintlock. It included a locking pawl to keep the cylinder in line with the barrel, and a percussion cap that made ignition more reliable, faster, and safer than the previous designs.” (This is much more edifying when you learn what a pawl is: “a pivoted curved bar or lever whose free end engages with the teeth of a cogwheel or ratchet so that the wheel or ratchet can only turn or move one way.”)

If you can refrain from asking yourself what sort of man would want to invent a more efficient killing machine, Colt’s patent is worth reading, or at least skimming, for the sense it gives of technical writing in the mid-nineteenth century: it’s a strict, unvarnished account of how a thing works, surprisingly direct in its syntax, and full of great machine-age terms like pawl, arbor, shackle, ratchet, and mainspring. Today, when technical writing is a muddle of jargon and pleonasm, it’s pleasing to see how accessible this patent is—all the more so because it’s such a famous invention. Granted, this isn’t scintillating reading by any stretch of the imagination, but if you sat down with a tall urn of coffee and summoned your very best self’s powers of concentration, you could actually learn how to craft and operate a fucking gun.

Take this sentence, for example: “Fig. 9 is a spring, which holds the rod, Fig. 5, toward the hammer, that the connecting-rod may catch in a notch at the bottom of the hammer to hold it when set.” See? Lucid, if not limpid. In other places, the simple declarative sentences accrue in rapid sequence, achieving an almost poetic cadence, or at least an admirable degree of compression:

Fig. 1 represents the mainspring. Fig. 2 is the stirrup to connect the mainspring with the hammer. Fig. 3 is the hammer. Fig. 4 is the lever for setting the lock. Fig. 5 is the discharging-trigger. Fig. 6 is the adopter. Fig. 7 is the spiral spring to draw back the adopter. Fig. 8 represents all the parts combined.

Compare that simplicity to the language of more contemporary patents, such as this one, for a “remotely operable machine gun charging apparatus,” granted last year:

Positional information with respect to the hook member 82 is generated by the forward and rearward switches 136 and 138 which are schematically depicted in phantom in FIG. 3A. When the hook member 82 is in its forward “armed” position, a bottom side portion of the stage structure 74 depresses the forward switch 136 which responsively transmits a position confirmation signal 156 to the armament control panel 132 and also causes the forward position indicator light 144 thereon to be illuminated.

Patents see language in its most utilitarian form. There’s a part of me—and I realize I may be quite alone in this—that’s captivated by the precision demanded of technical writing; this part of me could stand to read the stuff for hours. I can see myself, in old age, amassing a collection of, say, old radar systems manuals and reading them in my easy chair until I nod off. Such writing tends to bristle with potent nouns, all of them carefully calibrated, intensely compound, and entirely free of emotional valence. “Forward position indicator light.” “Position confirmation signal.” “Armament control panel.”

The appeal in this sort of thing, if you don’t see it, is summed up in of one of my favorite DeLillo quotations, a somber but delirious compilation of high-impact nouns from his short story “Human Moments in World War III”:

As the surface features unfurl I list them aloud by name. It is the only game I play in space, reciting the earth names, the nomenclature of contour and structure. Glacial scour, moraine debris. Shatter-coning at the edge of a multi-ring impact site. A resurgent caldera, a mass of castellated rimrock. Over the sand seas now. Parabolic dunes, star dunes, straight dunes with radial crests. The emptier the land, the more luminous and precise the names for its features. Vollmer says the thing science does best is name the features of the world.

Chase Twichell’s “To the Reader: Twilight”

Detail from Felipe Galindo’s Magic Realism in Kingbridge, which appears in the Poetry in Motion series accompanying Twichell’s poem.

The MTA has an initiative called Poetry in Motion, which brings verse to riders of the New York City subway. The last time I was groped on the subway, I was reading one such poem: “To the Reader: Twilight” by Chase Twichell. It is an enjoyable, accessible poem—they tend to be—but it felt strangely apt.

It is a truth universally acknowledged that any woman who rides any public transport for any length of time will, at some point, come into close contact with a covert masturbator. I should amend that, actually: it is universally acknowledged among women; men are always surprised to learn that this is a quotidian reality of distaff urban existence.

“Was it a very crowded train?” asked my mother, the first time it happened to me. I nodded tearfully. “Was it a businessman in a suit? It always is,” she said grimly. I was fourteen at the time, looked twelve, and found the experience exceedingly disturbing. We did not yet have poetry in the subway.

“Next time it happens,” said my mom, “shout ‘PERVERT! PERVERT!’ and everyone will turn on him.”

This advice, in retrospect, demonstrated a touching faith in the vigilantism of the average New Yorker. It also depended on a certainty that rarely exists in such situations. After the fact, somehow, you are always sure. But in the moment, packed like sardines in a crowded car, with a crafty pervert moving with the train’s undulations, there is always reasonable doubt.

In recent years, to address the problem of sexual harassment, the MTA has started airing public service announcements that sound as if they were composed by someone’s prudish maiden aunt. “A crowded subway is no excuse for an improper touch,” the announcer used to chide—more lately, perhaps because “improper touch” was too memorably vague, he substitutes “unlawful sexual conduct,” and encourages victims of said ungentlemanly conduct to report the cad to the authorities, who will, presumably, give him a sound horsewhipping to curb his animal high spirits.

If I could write these announcements, they would be more blunt. “Yes, you are being masturbated against by that businessman,” my announcement would say. “No one does that by mistake; most of us go to extreme lengths to avoid that contact, no matter how crowded the train. And it’s not an umbrella, or the edge of a briefcase; you know it isn’t. Here’s the test: grind your heel into his instep. If it stops, well, there’s your answer. In my mother’s ideal world, you would confront him, and by shaming him, you might spare another woman the same unpleasantness. Maybe one day you will. I suppose we all need to harden ourselves in different ways; it’s just a question of deciding how. (That’s not a pun.) Once I got out at the next stop just to end it, and until I could, I kept my eyes fixed on the flowery cursive of the civic poetry, and I was distracted by the image of snowy mountains and chilled by the thought that I could shout and maybe no one would care, and I was grateful for it. I think ‘Poetry in Motion’ is a good idea.”

Whenever I look

out at the snowy

mountains at this hour

and speak directly

into the ear of the sky,

it’s you I’m thinking of.

You’re like the spirits

the children invent

to inhabit the stuffed horse

and the doll.

I don’t know who hears me.

I don’t know who speaks

when the horse speaks.

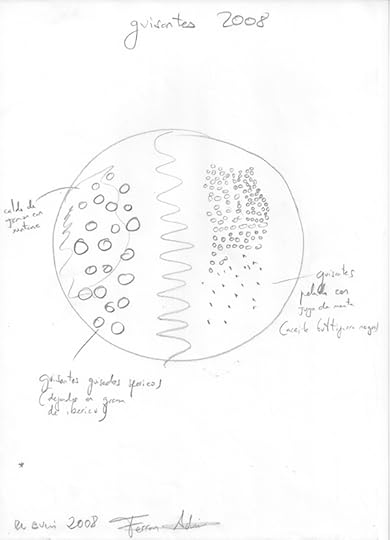

Sketches from the elBulli Kitchen

Detail from Ferran Adrià, Plating Diagram, c. 2000-2004; Colored pen on graph paper; courtesy of elBullifoundation

Ferran Adrià, Theory of Culinary Evolution, 2013; crayon, paint stick, and colored pencil; sixty drawings, each 11 11/16 x 8 1/4 inches; courtesy of elBullifoundation

Albert Adrià, Ferran Adrià, and Oriol Castro, from Notebooks Related to Creativity, 1987-2011; Ink on paper; Courtesy of elBullifoundation

Detail from Ferran Adrià, Plating Diagram, c. 2000-2004; Colored pen on graph paper; courtesy of elBullifoundation

Ferran Adrià, Theory of Culinary Evolution, 2013; crayon, paint stick, and colored pencil; sixty drawings, each 11 11/16 x 8 1/4 inches; courtesy of elBullifoundation

Ferran Adrià, Creative Pyramid, 2013; ink on paper, dimensions variable; courtesy of elBullifoundation

Ferran Adrià, Theory of Culinary Evolution, 2013; crayon, paint stick, and colored pencil; sixty drawings, each 11 11/16 x 8 1/4 inches; courtesy of elBullifoundation

Ferran Adrià, Plating Diagram, c. 2000-2004; Colored pen on graph paper; courtesy of elBullifoundation

Marta Mendez, Pictograms, 2001/2013; Archival pigment print on Hannemuhle paper; fifteen prints, each 12 x 12 inches; courtesy of elBullifoundation

Ferran Adrià, Plating Diagram, c. 2000-2004; Colored pen on graph paper; courtesy of elBullifoundation

Marta Mendez, Pictograms, 2001/2013; Archival pigment print on Hannemuhle paper; fifteen prints, each 12 x 12 inches; courtesy of elBullifoundation

Ferran Adrià: Notes on Creativity, on view at the Drawing Center in New York through this week, seeks to claim the status of artist for one of the most innovative chefs working today. Adrià gained fame at the now-shuttered Spanish restaurant elBulli, where he sustained a three-star Michelin rating for fourteen years and garnered comparisons to another famous Catalan, Salvatore Dali. To call a chef an artist can smack of hyperbole, but the new vanguard in contemporary cuisine, led in no small part by Adrià, is defying previous definitions of gastronomy. But despite the surge in technique—and for that matter, cost—food’s ephemeral, basic-need status inclines art purists to consider it a flash in the pan. Notes on Creativity resolves these tensions with sketches and notes that indicate the complex, restless work of Adrià’s kitchen, to say nothing of his mind.

The objects on display—ledgers, notebooks, scrap paper—illuminate the extent to which cooking is a creative process, as impassioned and compulsory as any. While he ran elBulli, Adrià kept detailed records, filling stray pieces of paper with plating ideas, loose concepts, and flavor profiles. In these ephemera we see the evolution of Adrià’s style over decades, and his determination to articulate his designs. The sketches are a window into the expanse of Adrià’s imagination, in particular the plasticity of his process. As it turns out, he is just as likely to start with a visual impression of a dish, figuring out the flavor components later, as he is to begin with an ingredient—an approach that seems like the culinary equivalent of Ginger Rogers doing Fred Astaire’s moves backward and in heels.

Though Adrià has received the lion’s share of attention at elBulli, his collaborations are prevalent throughout the exhibition. Adrià championed the use of foam and mists in food, but it was the designer Luki Huber who figured out how to present and plate them. The star chef’s innovation often found expression in reshaping classic recipes. A corkboard displaying his staff’s reinterpretations of Peach Melba suggests he nurtured this thinking in others. In this light, El Bulli’s kitchen can be seen as something resembling a Renaissance workshop, with a dynamic culture of invention and instruction.

As art objects, the works are uneven. Huber’s food conveying devices—to call them simply plates would be a misnomer—are intriguing as design objects, but Adrià’s tree charts, which explicate his theories of food evolution, range from opaque to overwrought. Notes on Creativity could have used some editing, but in its totality, even the weakest drawings have value—they show us the font of Adrià’s creativity, which, once uncapped, is difficult to dam.

Lilly Lampe is a writer and art critic based in Brooklyn. Her writing has appeared in Art in America, ArtAsiaPacific, Art Papers, Artforum.com, and Modern Painters, among others.

Notes on Creativity will travel extensively after its time at the Drawing Center.

Specialists of Every Stripe Are Flummoxed, and Other News

What does it all mean? Image via the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library

“‘They shouldn’t be allowed to read it at all,’ Julian suddenly said. ‘They’re the editors,’ I said. ‘They’ve commissioned this thing. And they have to read it.’ ‘No. They will only prejudice it.’” The beguiling story of ghostwriting for Julian Assange.

“To cunt a text is to adore it.” How to cunt your favorite poets, including samples of Cunt Chaucer, Cunt Wordsworth, and Cunt Olson. A fun arts-and-crafts activity for you and your kids.

Why was the Coen brothers’ excellent latest, Inside Llewyn Davis, snubbed by the Academy?

What we know about the Voynich manuscript: it’s 246 pages, it was discovered in an Italian monastery in 1912, it consists of words and illustrations, it’s … well, it’s a manuscript. What it says, or whether it says anything at all, remains a mystery, even to linguists, chemists, historians, and physicists.

Perhaps forensic linguistics holds the key: “an investigative technique that helps experts determine authorship by identifying quirks in a writer’s style. Advances in computer technology can now parse text with ever-finer accuracy.” Aspirant criminals: write blandly.

February 24, 2014

Makeup Forever

Max Factor with Renée Adorée

As John Updike wrote in a 2008 New Yorker piece, Max Factor was “the inventor of modern makeup.” Not only did this former beautician to the czars concoct the first movie makeup (it held up under hot lights) and bring commercial cosmetics to the average American drugstore, he also invented lipstick, mascara, lip gloss, false eyelashes, and foundation. Most original of all, in its way, was his invention of “Color Harmony”—i.e., the concept that your makeup should match your hair and complexion. In the early days of one-size-fits-all beauty, this was a paradigm shift, and it is memorialized in his office building at 1660 North Highland, now the Hollywood Museum, where you can still visit his original four rooms: for blondes (blue-hued; the ribbon was cut by Jean Harlow), redheads (green, Ginger Rogers), brunettes (pink, Claudette Colbert), and brownettes (peach, Rochelle Hudson).

For this was the idea: when a starlet walked into one of these rooms, she could look in the mirror and tell immediately whether she was meant to go blonde (as both Harlow and Marilyn did, in the blue room), or perhaps red, like Lucy. “For Redheads Only,” reads the sign on the door of the room off the museum lobby, and while I had always privately fancied that I might look ravishing with russet locks, it cannot be denied that the green-hued walls gave me a distinctly bilious cast. Color Harmony confirmed that, as nature intended, I was an unglamorous brownette.

When I visited the museum, it was early in the day. But I had a few fellow patrons: a nice older gent with a very taut face, dramatically dark brows, and smooth, tobacco-colored hair; a lady of a certain age with a Veronica Lake coiffure; and a pair of younger fellows, both sporting rouge, who informed me that this had been their first stop off the plane. They were headed for the Brunette Room. I turned right at Brownette.

The brownette is an antiquated concept, but distinctions used to be made between raven-haired, dark-eyed beauties and their lighter counterparts. Apparently even in its heyday (Factor coined brownette in the late twenties) the term was controversial. Writing in a February 1939 “Hollywood Beauty Secrets” column, his son wrote,

In undertaking an article on the proper make-up practices for brownettes, I am immediately stepping into a field which is very regularly conducive to arguments. The reason for this is that many feminine appearances which really should fall under the brownette classification of natural hair and complexion coloring are quite of-ten wrongly considered by their possessors to be blonde or brunette. The brownette is one whose natural complexion and coiffure tints actually should be placed in a range definitely in between the blonde and brunette degrees of coloring—and statistics prove that forty-eight per cent of the world’s women come under this brownette classification.

He then further confuses the issue by insisting that Merle Oberon and a few other popularly supposed brunettes are in fact dark brownettes, whereas lots of blondes are light brownettes. By his own admission, “the distinction here is an extremely fine one.”

As a Factor coinage, brownette seems to have died with that company, but even on its home turf, I couldn’t help thinking it got the lamest of the four rooms, even if Rochelle Hudson was a WAMPAS Baby Star in 1931 and would feature in the OG Imitation of Life. Still, I did feel at home in that peach room—the others were in the more glamorous blue room, looking at the Marilyn stuff, or communing with Joan Crawford in pink—and was interested to read that the brownette color harmony demands were for “rachelle powder, blondeen rouge, vermilion lipstick, gray eyeshadow (or brown shadow for those with hazel eyes), black eyebrow pencil and eyelash make-up, blush make-up foundation, and rachelle make-up blender.”

When a docent came around and asked me if I had questions, I did: What about stars who were not white? He hastened to explain that Factor had indeed done the makeup for all actresses of the era; Lena Horne had gotten her own color scheme, “Dark Egyptian.” There was a head shot of Anna May Wong, signed to Max Factor. But of course, this did not extend to commercial makeups: there would be no devoted cosmetics lines for women of color until the 1970s, which was also, not incidentally, when the Max Factor empire was in decline.

Interviewed in 1959, Max Factor Jr. was asked to make beauty predictions about the world fifty years hence.

“I firmly believe that in the future women of fifty years or more will look as appealing as girls of twenty. We are keeping in touch with scientific experiments in Europe on youth-giving cosmetics.”

Factor also foresees the extensive use of cosmetics by men fifty years from now, and for the same reason; to keep young. Men who live longer will want to work longer; hence they’ll need to avoid looking aged. Among the Factor predictions: A pill which will forestall the graying of hair.

There is a film one can watch at the museum that details the history of the company. Darryl Hannah is the narrator. One of the main talking heads is RuPaul. Which is to say, his prediction was kind of accurate. On the other hand, Max Factor, then owned by Proctor & Gamble, was discontinued in 2010. And last year, one of the heirs to the fortune was sentenced to fifty years for serial rape.

“It’s a real taste of Hollywood glamour, isn’t it?” said the Veronica Lake lady as we stepped into the sunshine. I guess it was. In any case, I bought some vermilion lipstick.

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers