The Paris Review's Blog, page 730

March 6, 2014

Dennis Wilson Was a Good Editor

Charles Manson’s Lie: The Love and Terror Cult was released forty-four years ago today.

Dennis Wilson was the only Beach Boy who surfed. Accordingly, he embraced a more, let’s say, briny side of the beach-bum lifestyle—he’s the only Beach Boy you can picture actually sleeping on the beach, living out of the rusted trunk of some boat of a car, feeding the gulls, rolling spliffs, letting himself go. His excellent solo record, Pacific Ocean Blue, proves how undervalued he was in the band. But his work on “Never Learn Not to Love,” the B-side to 1968’s “Blue Birds Over the Mountain,” proves that he knew how to wield a red pen.

First, some obligatory exposition. It was Charles Manson—yes, the—who first wrote “Never Learn”; he called it “Cease to Exist,” and when his friend Dennis Wilson, that Beachiest of Beach Boys, asked to record it, he was thrilled. Or rather, he would be thrilled, he said, if Wilson agreed to one condition: he was not to emend Manson’s lyrics in any way.

He did, of course; he retitled the song, rejiggered the verses, tossed in a bridge, and quietly published the song as his own. Manson, as you can imagine, was pissed, and threatened to kill Wilson, but when the former turned up on the latter’s doorstep, it was apparently Wilson who beat the piss out of Manson, not the other way around.

As befits a story starring a cult leader, this is a tale full of apocrypha and lurid curlicues—hitchhikers, bullets, group sex culminating in group gonorrhea—but the lyrics, not the diseases, are our interest here. To compare, here are the lyrics to Manson’s “Cease to Exist”:

Pretty girl, pretty pretty girl

Cease to exist

Just, come an’ say you love me

Give up, your world

Come on you can be

I’m your kind, oh your kind an’ I can see

You walk on walk on

I love you, pretty girl

My life is yours

Ah you can have my world

Never had a lesson, I ever learned

But I know, we all get our turn

An’ I love you

Never learn not to love you

Submission is a gift

Go on give it to your brother

Love and understandin’

Is for one another

I'm your kind, I’m your kind

I'm your brother

I never had a lesson, I ever learned

But I know we all, get our turn

An’ I love you

Never learn not to love you

Never learn not to love you

Never learn not to love you

And here’s how Wilson punched them up in “Never Learn Not to Love”:

Cease to resist, come on say you love me

Give up your world, come on and be with me

I’m your kind, I’m your kind, and I see

Come on come on, ooh I love you pretty girl

My life is yours, and you can have my world

I’m your kind, I'm your kind, and I see

Never had a lesson I ever learned

I know I could never learn not to love you

Come in now closer

Come in closer closer closer

Submission is a gift given to another

Love and understanding is for one another

I’m your kind, I'm your kind, and I see

Never had a lesson I ever learned

I know I could never learn not to love you

Come in now closer

Come in closer come in closer

The elisions and changes are all sensible—most obviously in the turn from “exist” to “resist,” which retains all the chilling coercion but leaves all that existential engulfment stuff behind. In one word, it captures the difference between saying “I know it’s scary, but please be mine” and “Hi, I would like to subsume the whole of your being.” (Likewise, changing “brother” to “another” instantly absolves the song of any incestuous undertones.)

But what really impresses me about Wilson’s edit is how much he kept: this is no carve-up. Many are understandably baffled when they hear that the Beach Boys covered a song by Charles Manson, but when you look at how many of Manson’s lyrics remain untouched, you get a good sense of what Wilson saw in the source material: a song whose helpless, scary yearning makes it at once repulsive and affecting.

It can be hard to forgive the menacing intensity of the song, especially when you know who’s responsible for it. But pop music is teeming with overzealous lovers, and the deranged, over-the-top candor of such lyrics is part of their appeal. If you think you’re immune to such things, just look at these unvarnished, abject, terrifying lines of Mariah Carey’s, and try to pretend you haven’t sung along: “You’ll always be a part of me / I’m part of you indefinitely / Boy don’t you know you can’t escape me / Ooh darling ‘cause you’ll always be my baby.”

Unbelievably, Wonderfully Grand

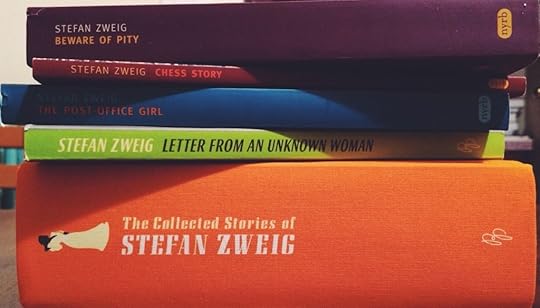

Wes Anderson, Stefan Zweig, and their sumptuous surroundings.

A still from Grand Budapest Hotel.

Looking at this year’s Academy Award nominees for Best Adapted Screenplay, Bill Morris at The Millions grumbled that “Hollywood screenwriters need to mix more fiction into their diet.” He can at least give a pass to Wes Anderson, whose new film, The Grand Budapest Hotel, is based not just on one novel but on an entire oeuvre—that of Stefan Zweig, an Austrian writer whose work Anderson has helped revive. In fact, Zweig’s influence on Anderson is so profound that the filmmaker compiled The Society of the Crossed Keys, a new anthology of Zweig’s work. Unfortunately, the collection is only available in the UK, but its constituents—Zweig’s memoir, the novel Beware of Pity, and the novella “Twenty-Four Hours in the Life of a Woman”—can be found separately in the US.

Both Zweig and Budapest find comedy and melancholy in the changing landscape of 1930s Europe, and Anderson is quick to admit his debt to Zweig. The film features two characters meant as stand-ins for the writer—there’s the hotel’s nostalgic, effete concierge, M. Gustave, and the unnamed “Author,” who appears throughout as a narrator and interlocutor. But Zweig’s influence on Anderson extends far beyond this latest film. Though Anderson says he came across Zweig’s books only six or seven years ago, the pair have long shared similar themes and aesthetics, even if Anderson didn’t know it.

For starters, consider their fastidious preoccupation with appearance. In an essay examining The Royal Tenenbaums against J. D. Salinger—another of Anderson’s literary influences—Matt Zoller Seitz established a concept called “material synecdoche—showcasing objects, locations, or articles of clothing that define whole personalities, relationships, or conflicts.” Anderson uses his meticulously designed mise en scene as visual shorthand for his characters. It’s how we understand the Tenenbaums from their wardrobe, their childhood bedrooms, and the way the opening scene itemizes the things in those rooms. It’s one of Anderson’s favorite storytelling mechanisms—think of Moonrise Kingdom, in which Sam Shakusky’s raccoon hat and glasses set him apart from the rest of the Khaki Scouts; think of Max Fischer’s red beret in Rushmore. In Anderson’s work, the exterior reliably informs the interior.

Sixty-seven years earlier, Zweig was taking the same tack. Take, for example, this character description from his last novella, Chess Story:

For the instant he stood up from the chessboard, where he was without peer, Czentovic became an irredeemably grotesque, almost comic figure; despite his solemn black suit, his splendid cravat with its somewhat showy pearl stickpin, and his painstakingly manicured fingernails, his behavior and manners remained those of the simple country boy who had once swept out the parson’s room in the village.

Zweig uses the man’s apparel as a point of entry—every article of Czentovic’s clothing is cataloged, and as the items pile up, we see that they’re larded with an assessment of his character.

Zweig applies this same material synecdoche to his environments. Post-Office Girl, the novel that has the most in common with The Grand Budapest Hotel—it’s set in an extravagant hotel, also during the beginning of World War Two—takes a working-class mail girl, Christine, and sweeps her off to a resort in the Swiss Alps. As Christine accustoms herself to the place’s fantastical decadence, Zweig takes a kind of inventory of her hotel room:

First she cautiously tries out the bed: will it really be all right to sleep there, on that effulgence of cool white? And the flowered silk duvet, spread out like down, light and pillowy to the touch. A push button turns on the lamp, filling every corner with its rosy glow. Discovery upon discovery: the washbasin, white and shiny as a seashell with nickel-plated fixtures, the armchairs, soft and deep and so enveloping that it takes effort to get up again, the polished hardwood of the furniture, harmonizing with the spring-green wallpaper, and here on the table to welcome her a vibrant variegated carnation in a long-stem vase, like a colorful salute from a crystal trumpet. How unbelievably, wonderfully grand!

It’s Christine’s sense of wonder and naiveté to the bourgeois lifestyle that establishes her character. And that’s just her room—the novel devotes many pages to chronicling the hotel’s extravagance. Post-Office Girl is full of these precise details, itemized in language as lavish and colorful as the things it describes.

Anderson has a similar fixation on privilege, especially as its seen through the eyes of the less privileged—Max from Rushmore; Zero, the bellboy who works under M. Gustave, in The Grand Budapest Hotel; and, in some ways, Ned Plimpton in The Life Aquatic. Such outsiders serve a useful purpose: they allow the audience to share in a material fascination with the worlds Anderson has created.

Anderson has a similar fixation on privilege, especially as its seen through the eyes of the less privileged—Max from Rushmore; Zero, the bellboy who works under M. Gustave, in The Grand Budapest Hotel; and, in some ways, Ned Plimpton in The Life Aquatic. Such outsiders serve a useful purpose: they allow the audience to share in a material fascination with the worlds Anderson has created.

Naturally, this mutual obsession with material wealth leaves Anderson and Zweig vulnerable to the same criticisms. At n+1, Christian Lorentzen has criticized Andersons reliance on “sets, costumes, characters, and neato conceits” over the felicities of plot. On Zweig’s end, Joan Acocella’s introduction to Beware of Pity notes that the author often drew fault when he tended toward “clanking narrative devices” and the “plump, upholstered quality to some of his writing.” And yet, as apposite as they are, these complaints feel small, even if the three brothers in The Darjeeling Limited carry literal baggage, and quite immaculately designed baggage, at that. When it comes to narrative, Anderson and Zweig prefer to let their lavish, intricate microcosms do the heavy lifting. But this is where they diverge: Anderson’s worlds are imagined; Zweig’s are real, and deeply remembered.

Perhaps this is why so many Anderson films come with frame stories. Since they’re contained in books or recounted by storytellers at a far remove from the action, the viewer can see that these are worlds Anderson has created, not attempts at realism. And he’s careful to set his films in openly imaginary locations. The Grand Budapest Hotel takes place in the fictitious Republic of Zubrowka; Moonrise Kingdom invented the New England island of New Penzance. The oceans of The Life Aquatic are filled with exotic, imaginary sea life; The Royal Tenenbaums takes place in an alterna-New York where everything is lettered in Futura. In a Wall Street Journal piece, Anderson admitted that he struggled to find a real-life location to film The Grand Budapest Hotel. He looked at old hotels in Austria, Hungary, the Czech Republic, and Poland before discovering the right set in Görlitz, Germany. In fact, the building ended up being an unoccupied department store, not a hotel.

In an interview with Anderson, George Prochnik, the author of a new Zweig biography, connects these location scouting difficulties with a sentiment at the end of Budapest, where Zero suggests to the author/narrator that the world of luxury and grandeur that M. Gustave represents may have disappeared well before the war: “The possibility is raised that the world M. Gustave inhabits may really have ceased to exist even before he entered it. There is a suggestion that the whole thing is a feat of imagination. I think this resonates with the embrace of illusion in [Zweig’s memoir] The World of Yesterday.”

In many ways, Anderson’s films concede the same thing. The worlds he builds are depicted through outlandish rose-colored lenses. In his introduction to The Wes Anderson Collection, Michael Chabon notes that Anderson’s universe is “a scale model of that mysterious original [world], unbroken, half-remembered.” He also sets his films in liminal spaces: a room at the Grand Budapest or Hotel Chevalier, a sleeper cabin on the Darjeeling Limited, a voyage aboard the Belafonte. These are transitional places, as if Anderson is acknowledging that their luxury is similarly temporary—or fabricated.

But if Anderson likes to invent and inhabit bygone worlds, Zweig actually lived in them, and the sense of loss is more acutely felt in his work. He wrote the aforementioned memoir, The World of Yesterday, while living in exile in Brazil; it’s both a nostalgic portrait of prewar Europe and a lament for its obsolescence. Ten days after turning in the manuscript for the book, Zweig and his wife overdosed on barbiturates in what appeared to be a suicide pact. Zweig longed for the world that had passed him by, one he knew could not return—one he perhaps remembered too fondly.

Kevin Nguyen is a founding editor at The Bygone Bureau, a contributor to Grantland, and an editor at Amazon Books.

Eternal City

Photo: Sadie Stein

The Whitney Biennial has generated any number of reviews—the more comprehensive ones will tell you about the distinguished curators, the three “biennials within a biennial,” the ambient sound installations.

So far, I have not read anything about the Apple.

On a chilly evening earlier this week, I attended a preview with a friend. It was, as others have recounted, crowded. “I thought you were the artist,” said a woman as I studied one of the pieces, a voluptuous ceramic by Alma Allen. “Because of the way you’re dressed, I mean.”

“Thank you,” I said. Alma Allen is a man.

By the door, a young woman was handing out canvas bags. “Just the ladies,” she said as we exited.

I waited until I was home to open my gift bag. Inside was a black box. “BCBGMAXAZRIA + WHITNEY MUSEUM OF AMERICAN ART,” said one side of the box. Another side said “Celebrating 25 Years of Style.” A third said, “25th Anniversary Chrome Apple.” And the fourth featured text:

This chrome apple epitomizes the eternal relationship between fashion and art. We present this gift to you in celebration of BCBGMAXAZRIA’s 25th anniversary and the 2014 Whitney Biennial Sponsored by BCBGMAXAZRIA.

No one dare accuse this box of false advertising. For inside was indeed a chrome apple, which was itself a small box, covered in spikes. I stared at it for some time. I took a picture and sent it to some friends. “Looks more like a durian,” commented one of them, accurately. I left it on the counter and went to bed.

The next morning, there it was. When I went downstairs to get my mail, I deposited the apple, in its explanatory box, on a small table in the lobby that serves as a tacit giveaway area for the building; it’s usually populated by books. This table has voodoo qualities. I have never seen anything there go unclaimed, be it an outdated Lonely Planet Madrid, an old VHS tape, The Kosher Cajun Cookbook, or a pair of light aerobics weights, although in the spirit of full disclosure, I myself am now the owner of those last two.

And yet, when I went downstairs again some four hours later, it was still there, sitting in solitary splendor. My brow knit with disgruntlement. I spied a four-year-old neighbor.

“Hi, Pablo!” I said. “Would you like this metal apple? See? It’s a little box. That looks like an apple.”

He inspected it gravely, suspiciously. “Why are there spikes on it?” he said.

“Because it’s … art,” I said.

“I don’t want it,” he said with brutal candor, and went upstairs.

“Your loss,” I muttered, and stuffed the box into my tote.

On the subway, I found myself seated near a family of obvious tourists carrying a large Build-A-Bear bag.

“I’m sorry to interrupt,” I said, “but I’d like to offer you a souvenir of the Big Apple. It’s from the Whitney Museum.” I proffered the box.

“No, thank you,” said the mother hastily, moving her little girl down the car away from me.

“See if I care,” I said too loudly.

I schlepped the apple around for the rest of the day. Come nightfall, I went into a Starbucks to use a bathroom, and my eye fell on the bag of the man ahead of me in line. It was the gift tote from the Whitney.

“I thought only women got that,” I said. It took some moments before he had any idea what I was talking about.

“Yeah, someone gave me hers,” he said. “But I didn’t get any of the stuff that came with it.”

“It’s not fair,” I said. Then the bathroom door opened, and my moment had passed.

Later that day, I went back to the Whitney to try to actually get a crack at the sound installations. “What’s that?” said the guard who was checking my bag. But he would not confiscate it. So I left it in the lobby.

How to Convert a Nonbeliever

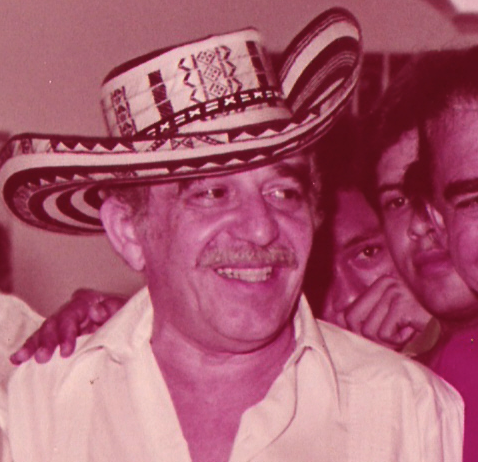

Gabriel García Márquez is eighty-six today.

Márquez in 1984. Photo by F3rn4nd0, via Wikimedia Commons

INTERVIEWER

You describe seemingly fantastic events in such minute detail that it gives them their own reality. Is this something you have picked up from journalism?

GARCÍA MÁRQUEZ

That’s a journalistic trick which you can also apply to literature. For example, if you say that there are elephants flying in the sky, people are not going to believe you. But if you say that there are four hundred and twenty-five elephants flying in the sky, people will probably believe you. One Hundred Years of Solitude is full of that sort of thing. That’s exactly the technique my grandmother used. I remember particularly the story about the character who is surrounded by yellow butterflies. When I was very small there was an electrician who came to the house. I became very curious because he carried a belt with which he used to suspend himself from the electrical posts. My grandmother used to say that every time this man came around, he would leave the house full of butterflies. But when I was writing this, I discovered that if I didn’t say the butterflies were yellow, people would not believe it.

—Gabriel García Márquez, the Art of Fiction No. 69

Death, and Other News

A depiction of one of Frederik Ruysch’s anatomical displays. Image via the Public Domain Review.

Sherwin B. Nuland, the author of How We Die, is dead.

In Los Angeles, a group of ghost hunters are chasing the dead.

The punk ethos of the Lower East Side is dead.

The Dutch anatomist Frederik Ruysch died in 1731, but his deathly sketches still haunt us today: “not only did he exalt the human anatomy as a wondrous product of creation, but he presented himself as a veritable artist of death.”

On the eastern seaboard, the hemlock is dying out. Though the tree bears only a superficial resemblance to the plant that killed Socrates, “it seems impossible to separate the hemlock tree from the hemlock plant’s poison, for a poet to keep the death of Socrates out of the picture—for death is in the forest, especially a hemlock forest, especially now.”

March 5, 2014

That Was the Month That Was

Photo: Jack Weir, via Wikimedia Commons

Before everyone gets too deep into March—what with its Madness; its Ides; its suspicious “in like a lion, out like a lamb” mentality; its trying Lenten sacrifices; its Prince Kūhiō Day; blah, blah, blah—let’s not forget dear old February, arguably the most hated month, if not the cruellest. At only twenty-eight days, it always gets short shrift, even during leap years; it’s as if we can’t wait to wash our hands of it. Well, we’re here to say: we’re going to miss it. It was a fine month, one for the books, and we have proof—below are some of the excellent long essays the Daily published. Now, onward, to Saint Patrick’s Day, Pi Day, National Potato Chip Day, and Save a Spider Day.

Sabine Heinlein: “We sat across from each other in a circle surrounded by several other convicted murderers and three Quakers who led the ministry. Richard looked ashen and frail, and yet I could see something glowing in him.”

David Pablo Cohn: “They could just once utter that coveted phrase in a loud, authoritative but calm voice: ‘Stand back, everyone—I’m a computer scientist.’”

Clifford Chase: “‘You may hear a cracking sound,’ said the oral surgeon, who was also named Cliff. He was inserting a pair of pliers in my mouth. I heard the cracking. Occasionally life plunges you into an experience that, for its utter intensity and obscure resonance, may as well be a dream.”

Rebecca Bengal: “In the midseventies demimonde of Memphis, things had a way of becoming totally and suddenly unhinged, and McGill was frequently the author of their unhinging.”

Andy Battaglia: “’Pour it a little more aggressively,’ he said through a mouthpiece to a production designer wetting the set with a strange, unidentified liquid. To the actress Ellen Burstyn, in the midst of a stubborn scene, he suggested, ‘I think we should not smile.’”

Sharon Mesmer: “I knew that the smudge was the result of the camera having been in motion when the photo was taken, but I felt that that smudge was my soul.”

Matthew Olshan: “People think of Washington, D.C., as a transitory place—a city of four-year leases, tourists, and revolving doors—an impression that dates back to the earliest days of the federal capital. The city fathers, desperate to counter the District’s reputation as a provincial backwater, fought back by building monuments.”

Adam Leith Gollner: “When we parted, on the boulevard du Montparnasse, I leaned over to give her a kiss on the cheek. ‘If you do find paradise,’ she said, turning to leave, ‘send me a grape.’”

Edward McPherson: “During the Civil War, St. Louis had slaves but was not southern. It is not western, like Kansas City, on the other side of the state, but it is not eastern, not really—just ask any transplant from the coast. It truly is Middle American, whatever that means. There’s the old joke: what kind of city would advertise itself as a jumping-off point, an exit door, a gateway to somewhere else?”

Harry Backlund: “We follow a naive, Chaplin-esque everyman through a huge city, dropping in and out of the lives of strangers: nursing a dying woman, farting on a group of businessmen, falling in and out of love with a prostitute.”

Miranda Popkey: “Picture a Venn Diagram; label one circle ‘Fans of the New England Patriots’ and the other ‘People Who Have Studied Sir Gawain and the Green Knight.’ The person who exists at the intersection of those two circles was sitting on a couch across from me, anxiously eating chips and guacamole.”

The Child Is Father of the Man

Once upon a time, a very nice couple whom I didn’t know very well threw some kind of party. I can’t remember what the occasion was, but I do know that they lived in a nice apartment near the Broadway-Lafayette F stop, and that I went to the party with a former boyfriend. It proved to be a memorable evening.

We made small talk with lots of nice people. At some point we found ourselves clustered together with two other couples, at least one component of each was an architect. Some public figure had just come out as gay, and one of the guests said something innocuous about the importance of being true to oneself.

“Oh, I agree,” said one of the women, blandly. “Take my father-in-law, for instance. It wasn’t until he got terminal cancer that he was able to tell the world who he really was.”

“What was that?” said my ex-boyfriend.

“A nineteenth-century baby.” she said. “His true desire had always been to dress in a gown and a bonnet. And when he had his fiftieth college reunion”—here she mentioned an Ivy League university—“he said he wanted to show his classmates who he really was. So my husband wheeled him around in a large pram, and he carried a silver rattle.”

There was a silence.

“Where did you get the pram?” I finally asked.

“Oh,” she said. “We had to get it made.”

We drank in silence.

Sometimes, when I feel tired or dispirited and want to stay home, I remind myself of this incident. Because life is full of wonderful surprises.

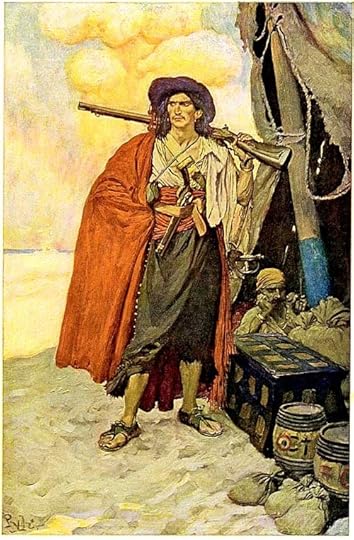

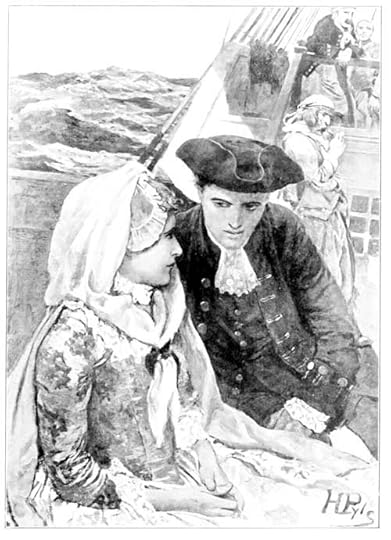

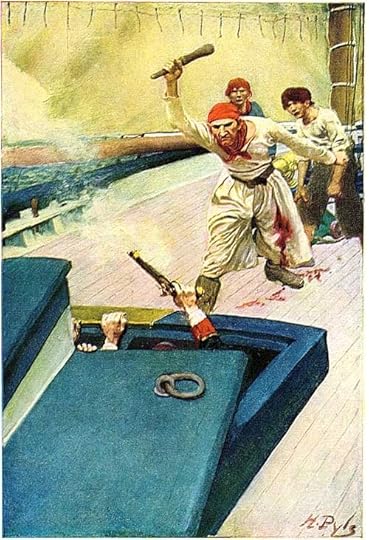

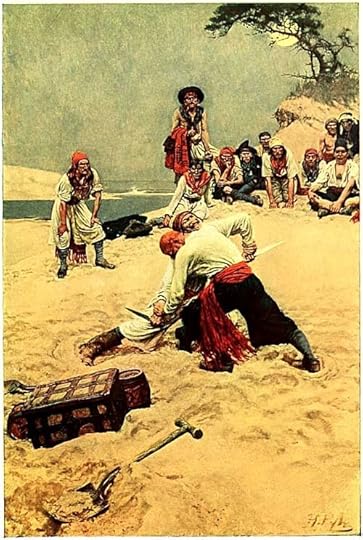

The Buccaneer Was a Picturesque Fellow

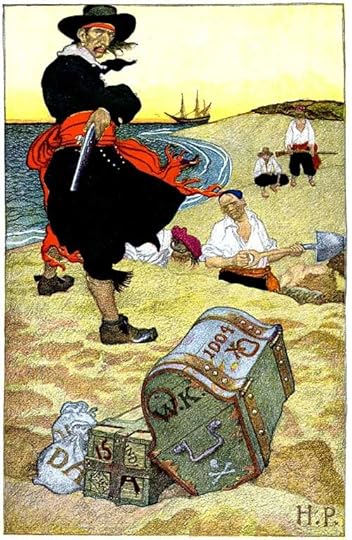

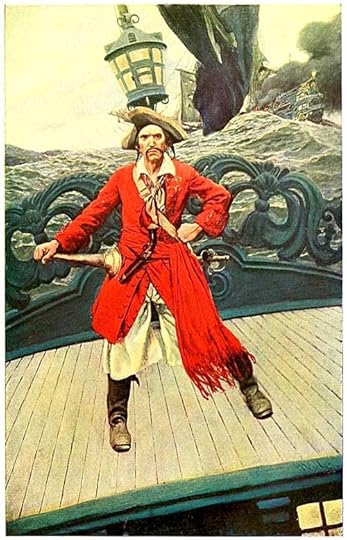

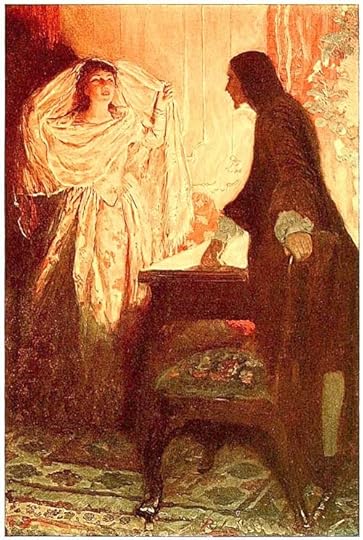

The author and illustrator Howard Pyle was born today in 1853. These illustrations are from Howard Pyle’s Book of Pirates , a 1921 compilation of his famous pirate stories; its preface is reprinted below.

Kidd on the Deck of the Adventure Galley

On the Tortugas

The Buccaneer Was a Picturesque Fellow

She Would Sit Quite Still, Permitting Barnaby to Gaze

Buried Treasure

The Bullets Were Humming and Singing, Clipping Along the Top of the Water

Captain Keitt

Extorting Tribute from the Citizens

I Am the Daughter of that Unfortunate Captain Keitt

Then the Real Fight Began

Who Shall Be Captain?

Pirates, Buccaneers, Marooners, those cruel but picturesque sea wolves who once infested the Spanish Main, all live in present-day conceptions in great degree as drawn by the pen and pencil of Howard Pyle.

Pyle, artist-author, living in the latter half of the nineteenth century and the first decade of the twentieth, had the fine faculty of transposing himself into any chosen period of history and making its people flesh and blood again—not just historical puppets. His characters were sketched with both words and picture; with both words and picture he ranks as a master, with a rich personality which makes his work individual and attractive in either medium.

He was one of the founders of present-day American illustration, and his pupils and grand-pupils pervade that field to-day. While he bore no such important part in the world of letters, his stories are modern in treatment, and yet widely read. His range included historical treatises concerning his favorite Pirates (Quaker though he was); fiction, with the same Pirates as principals; Americanized version of Old World fairy tales; boy stories of the Middle Ages, still best sellers to growing lads; stories of the occult, such as In Tenebras and To the Soil of the Earth, which, if newly published, would be hailed as contributions to our latest cult.

In all these fields Pyle’s work may be equaled, surpassed, save in one. It is improbable that anyone else will ever bring his combination of interest and talent to the depiction of these old-time Pirates, any more than there could be a second Remington to paint the now extinct Indians and gun-fighters of the Great West.

Important and interesting to the student of history, the adventure-lover, and the artist, as they are, these Pirate stories and pictures have been scattered through many magazines and books. Here, in this volume, they are gathered together for the first time, perhaps not just as Mr. Pyle would have done, but with a completeness and appreciation of the real value of the material which the author’s modesty might not have permitted.

Welcome to Paradise

The sounds of Key West.

Photo: Ann Beattie

Photo: Ann Beattie

Photo: Ann Beattie

Photo: Ann Beattie

Photo: Ann Beattie

What do writers want? (Forget whether they’re women or men, Uncle Sigmund. Forget money and fame.) They want quiet. Where do they go? They gather in Key West, Florida.

Sure, the subtlest sounds—the personally groaned sounds—begin with deep sighs, as other people discuss pools being dredged by the jackhammering of coral next door, leaf blowers switched on at eight a.m., drunks on the sidewalk talking to themselves even more animatedly as the police car pulls to the curb. Last night I hung over my balcony to hear a staggering gentleman informing the officer that he did have a destination. He was “gonna shuffle off to Buffalo.”

In the background, birds express opinions from people’s shoulders on late-night walks (“Pretty but what else?”—a bird clearly meant to call one’s life into question). All around the island cell phones go off, their ring tones arias from operas or a hip-hop version of “Battle Hymn of the Republic.” Dogs bark, cats hiss, and the bird on the shoulder of the guy in the trilby continues to wonder aloud what to expect after “pretty.” Maybe the fire truck, or the ambulance that makes just a few high-pitched noises, as if the vehicle itself is dying. As it races away, it’s sure to set off a car alarm.

In front of our house, a man and a woman stop to discuss what he thought she was saying just a minute ago. He can hardly proceed because she erupts: that is not at all what she was saying. A guy goes by on a skateboard, aiming it toward irregularities in the street that might offer the opportunity of throwing him into some of the bicyclists. (Some of them pulling very young babies in see-through carts on the back, only inches off the ground. The babies wear helmets, as if babies only die if they sustain head injuries.) There’s the whistle from the cruise ship, about to leave port! A loud, angry argument between two guys who seem to have argued before, since each anticipates the other’s wild hand gestures. A Harley comes through, making a noise strong enough to kill bugs without spray. And overhead, flying low, United Airlines rumbles through the sky … but it makes it, unlike the sea plane a week or so ago that dropped stuff on the airport tarmac that turned out to be its landing gear. Then it angled crazily into the grass alongside the runway, as whistles went off and the airport was shut down. So much for making that flight.

Meanwhile, the kapok tree in our back yard, so huge and ancient that foreign visitors make special trips to see it, is in stage three of its molting: “the bombs,” green pellets that hit our tin roof all night long. All day, too. This goes on for over a month. Background music drifts through our open windows from the bars; drunken voices shriek on the balcony of a rental unit across the street, and into it comes the shrieking brakes of the trash truck, very early every Monday morning, lifting up trash cans, crushing the contents, preparing for its ride out to Mt. Trashmore to dump stuff and make the mountain higher. If it keeps going, there will be no space between mountain and sky for the buzzards to circle.

The bars close at four, after which there’s a final exodus of motorcycles loud enough to contact other planets. Soon it will be dawn and the skill saws will be out, the tree removal companies that grind up those gumbo limbos on the spot. Some wussy babies in their strollers can’t stop crying. Down the street rattles the Conch Train, filled with tourists, who receive dubious, though loudly announced information about what they’re seeing as they streak through neighborhoods on what looks like an enormous awninged caterpillar, whizzed past by kids on rollerblades and bicyclists who have the instincts of downhill racers in an avalanche, quickly jumping a curb to go the wrong way down sidewalks. A large van is loaded on a tow truck and dragged away (“Yeah, I’d say it’s been parked there since about Thanksgiving. There was a dog used to be tied to it.”) Here comes a bed race down Duval street! There goes a teenager with a woman’s purse; with those sounds she’s emitting as her arm dangles limply at her side, I thought the kid might have grabbed a pig. Which wouldn’t be impossible. People walk them on leashes here. Egrets walk around town like the many citizens who’ve had hip replacement surgery, narrower of leg and whiter than the humans, but equally exaggerated and tentative in the movement of their leg joints. When an egret was walking up the steps to a store, I heard an owner say, “Let it in. How do we know it doesn’t have AmEx?” Roosters scream, and though it’s illegal to kill them, there are many contracts out on their lives. The street musicians are playing, the guys and girls with their tattoos depicting other things that make noise—pirates; bucking broncos; wolves—are climbing on their Harleys, the cruise ships are getting desperate, bleating “When You Wish Upon a Star” (not kidding) much more loudly, the second time they blow. Electric hedge clippers come out most any time of day. You just can’t keep up with the fast growth of the ficus hedges all around town.

Did Papa Hemingway go to Cuba to get away from it? Did Elizabeth Bishop use earplugs? Might this be why Tennessee drank? Did Jimmy Merrill ask the Ouija board for advice?

Key West is advertised as Paradise, but it’s the paradise of the sqealing pig in the daily rodeo wrestle, the thundering, enormous van blasting heavy metal, the church choir in a residential neighborhood that gets together now almost every night and loudly sings, voices and musical instruments amplified. Bang bang Maxwell’s silver hammer is driving nails into the boards of the house across the street; the big refrigeration trucks make mighty, house-shaking noise as they pass by, playing chicken with the more sedate UPS, FedEx, and other delivery trucks that must navigate the narrow streets.

Come one, come all! Certainly you’ve read the recent story in The New Yorker about the literary seminar and its strange goings-on? Bring your tired, your weary, your tubas, your most enormous vehicles, your apps that play opera, your dogs that bark, your babies who cry, your drunks who howl, and friends in flip-flops who’ll stub their toes on the irregular sidewalks and scream, “Ow!”

It’s warm, and the rest of the country, not so much. The celebration’s always going on, with drink mixers pulverizing ice and men slashing coconuts in half with swords. Who wouldn’t let out a happy cry of triumph? If you make it to Paradise, you can pick up the beat, dial it up, push it, get yourself a shrieking bird and a vehicle with a music system worthy of Jon Bon Jovi. Turn it up until that bass shakes free their heart stents, man! Then head off, honking with pleasure, screaming a few yee haaaaaaaws from the window, high-fiving the wind, en route to a night of heavily amped karaoke. Sing loudly your songs of heartbreak, let everybody know you’ve arrived. That baby’s gotta grow up someday! lol

Ann Beattie’s story “Janus” was included in John Updike’s The Best American Short Stories of the Century.

See London with New (Old) Eyes, and Other News

Canaletto’s Northumberland House, 1752, juxtaposed against contemporary London by Shystone.

“What does the term ‘successful writer’ mean to you?” (Sample answers from writers at AWP: “Joy,” “$ and Happiness,” “Having a great publicist.”)

“The list in our time (‘28 Places To See Before You Die,’ or else what?) makes its fantastical claim that order exists, that order can be known … but this is not true.” TPR contributor J. D. Daniels rallies against listicles in a piece we’re pleased to include in this listicle.

Today in juxtaposition: an artist superimposes Canaletto’s paintings of Venice and London against modern Google Street View photos of the cities.

Uncelebrated and yet indispensable: New York City voiceover artists. “You’re background, you’re furniture. You provide atmosphere. But let’s face it, you’re not important.”

“I’m just a normal guy … But where I go to work each day just might surprise you … Sorry. Didn’t mean to do that. It’s one of the risks of the trade, I guess. I write headlines for Upworthy.”

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers