The Paris Review's Blog, page 726

March 18, 2014

Flame

On April 8, at our Spring Revel, we’ll honor Frederick Seidel with the Hadada Award. In the weeks leading up the Revel, we’re looking back at the work Seidel has published in The Paris Review throughout his career.

Photo: Shreyas Joshi, via Wikimedia Commons

“Flame” appeared in our Spring 1981 issue, which included stories by Faulkner, Carver, and Gass; poems by Amiri Baraka and Maxine Kumin, both of whom died earlier this year; and an interview with Rebecca West.

The poem finds Seidel in a more earnest mode; mostly, it’s just really fucking pretty.

The honey, the humming of a million bees,

In the middle of Florence pining for Paris;

The whining trembling the cars and trucks hum

Crossing the metal matting of Brooklyn Bridge

When you stand below it on the Brooklyn side—

High above you, the harp, the cathedral, the hive—

In the middle of Florence. Florence in flames.

Like waking from a fever ... it is evening.

Fireflies breathe in the gardens on Bellosguardo.

And then the moon steps from the cypresses and

A wave of feeling breaks, phosphorescent—

Moonlight, a wave hushing on a beach.

In the dark, a flame goes out. And then

The afterimage of a flame goes out.

Buy your ticket to the Revel here.

John Ashbery Reads “A Boy”

Today the composer Christopher Tignor releases a new record, Thunder Lay Down in the Heart, whose title track is a twenty-minute work for string orchestra, electronics, and drums. The composition is named after a line from John Ashbery’s 1956 poem, “A Boy,” and it begins with a haunting new recording of Ashbery reading the poem in his Chelsea apartment, which Tignor has graciously allowed us to feature here.

Tignor says:

“A Boy” rang out to me while I was writing “Thunder Lay Down in the Heart.” My song titles usually come in response to the music, and I often find myself looking through books of poetry to turn my mind on in that way. When I was a student at Bard, I studied poetry with Ashbery—he was my advisor—and when I read this poem, I responded right away to the conflict between the protagonist and the visceral narrative tension of the storm: the sound, like thunder, of falling “from shelf to shelf of someone’s rage,” the rain at night against the box cars, the inevitable flood.

It’s precisely that kind of unfolding I hoped to embody in my musical work, with its own flooded lines, dry fields of lightning, and cabbage roses. A reviewer recently described the work as its own “vast electrical disturbance.” Hard to disagree.

Getting Slapped Around: An Interview with Dorthe Nors

Photo: Simon Klein Knudsen

This month marks the release of Dorthe Nors’s Karate Chop, the Danish author’s first work to be translated into English and her only collection of short stories. Karate Chop is a small, dark collection. It consists of fifteen stories, most only a few pages long. Nors’s work often sounds like a parable relayed by one of the wryer, more fatalistic disciples, the one who doesn’t particularly care about our moral edification. But beneath the droll delivery, there tends to be a quiet heartbreak. In Karate Chop, parents disappoint, animals suffer, and certain boyfriends or husbands simply need killing. That heartbreak seems to belong as much to Nors as to her characters. We’re left with the impression that she would spare her creations all the sordid hurt and discord if the world were somehow different or she were a little less clear-eyed. Things as they are, she can only encourage them to laugh off what they can, to bear the rest, and to remember that certain dark corners of the world are “vast and beautiful and desolate.”

I spoke with Nors on her final day in the U.S. following the book’s launch. She is warm and confiding and possessed of a Northern European glamour that favors dark sweaters and disdains what most New Yorkers would consider a major and ongoing snowstorm. Throughout the hour we spent together, she drank trucker-strength coffee and held her chin in her hand. She told me about bucking tradition with new forms, the finer points of Danish comedy, and how life finds a way of slashing us all.

After four novels, it’s a short story collection—your first—giving you a breakthrough into the U.S. market. Why do you think that form did it?

Without me realizing it, I found that the short story—this compact, intensive way of writing—suited my voice. The short story isn’t really part of our tradition in Denmark. This is the country of Hans Christian Anderson and Karen Blixen, but for some reason there’s this sense that we don’t want to dirty our hands with the short story. That’s why it’s such a blessing that this is happening for me in America, where there’s such a strong tradition for the form. I feel like I’m presenting my work to a nation without having to explain what I’m doing.

How did you first step outside that tradition and decide to give the short story a try?

I always thought that writing short stories would be too difficult, but I knew this teacher who worked with at-risk teenagers and he asked me to come write a story about his class. So I spent some time with these kids and cooked something up. Afterward, the teacher assembled the entire school to hear me read this story, and when I was done, the kids were actually cheering. They could see themselves in it and they loved it. That experience boosted my confidence.

I’ve heard that you wrote this collection in a two-week binge. That’s pretty crushing news to other writers. Tell me it’s not true.

I went up the west coast of Denmark, to the dunes, to stay in a cottage that belongs to the poet Knud Sørensen. And yes, I was there for two weeks, alone, and the stories just poured out of me. At the time, I was in love. That’s part of what brought those stories out of me like crazy—that energy and openness you have when you think you just met the love of your life. There was a joy in writing these stories, even though I was writing about battered women and such very bad things. You know, Johann Sebastian Bach, after his wife and kids died, wrote in his diary that he hoped their deaths wouldn’t take away his joy. What he meant was the joy of creation. He could write the most dark and beautiful things, but there was a joy in being able to do it. I felt that during those two weeks. It was a creative happiness.

The succinctness of these stories—I think the longest is about six pages—is striking. Is that how they came to you, or was it a process of chiseling them down?

Other things I’ve written were much more structured and planned, but with this book, the stories just came to me. For instance, with the story “She Frequents Cemeteries,” I remember I had just come home from an evening walk, sat down at my desk, and started writing. It took me thirty minutes and I had that story and realized that it just worked.

Once you’ve had the stories write themselves, how do you go back to working any other way? It must be addictive.

I went for very different experiences with my next books. They use the same language, the same precision that I found writing the short stories, but I needed to do something a bit more experimental, so that I could find out how to use this style to write longer pieces. These are kind of crazy books. The first was written like a diary. The love I felt when I was writing the Karate Chop stories didn’t work out. I decided that I would write these lists every day for one hundred days and post each entry onto the Internet—because people like to peep under the covers, you know?—and then later I’d edit them into a novel. After that, I did my latest book, which is written entirely in headlines. I wanted to see if you could write a deep, vivid story using the language of modern communication, the language of the Internet—headlines. It seemed to crack people up. It was a success in Denmark.

Let’s talk about your sense of humor, because there’s a deadpan comedy in all your stories, applied to some very dark subjects. Is there something peculiarly Danish about that contrast, or is it all yours?

There’s a certain amount of Danish irony in it. Danish is an easily bended and toyed-with language. The Danes love a good punch line, a good dry sense of humor that’s almost British, and we enjoy telling people stinging truths with a smile. There’s a nurturing kindness to it, but it still stings. There’s a line in the story “The Buddhist” that captures it. “He wishes both of them well. Yet he also wants to do them harm.” When you use that kind humor up against the darker themes, you spare yourself a lot of chapters, because you can say both things at the same time. And it’s the darker themes that always draw us. We don’t want to read a book about how bleeding easy things are. We like the complicated stuff. I hear from people that they read Karate Chop fast. They say it’s a page-turner. I think it’s this darkness that entertains them and pushes them to read on.

Your stories don’t tend to use much dialogue, but there’s a distinct and human voice in each one. How do you find and hone those voices?

I hear them when I’m writing. For me, if a short story works well, it has to have a very specific voice and a specific presence, and you have to stay with that presence or it loses tension. Writing a short story, I can only describe it as standing on a stage and singing without stopping. You have to just be there. That’s what it’s like to write a good short story, anyway. A bad one, you’re still on the stage but people are all over the place, standing in the corridors, drinking coffee, talking to one another, and you still have to stand there.

It would be tough to read this collection without wondering what’s haunting the author. Did writing these stories feel like a way of exorcising demons, so to speak?

It’s a way of dealing with them, or at least trying to process them. Writers who don’t have demons will find some, or they won’t be writing. There was a period, over a couple years, when I was living in artists’ housing so that I wouldn’t have to pay rent, but I had to move around all the time—in 2006, I had six addresses and also lived in New York. It was a stressful time. I met all these angels and devils. Eventually I just decided that I needed to stay in one place. I felt too full, too much had happened. I needed to process it all. And these stories were a part of that. They’re very personal.

It’s a way of dealing with them, or at least trying to process them. Writers who don’t have demons will find some, or they won’t be writing. There was a period, over a couple years, when I was living in artists’ housing so that I wouldn’t have to pay rent, but I had to move around all the time—in 2006, I had six addresses and also lived in New York. It was a stressful time. I met all these angels and devils. Eventually I just decided that I needed to stay in one place. I felt too full, too much had happened. I needed to process it all. And these stories were a part of that. They’re very personal.

I think that writers who don’t deal with those personal things, those demons, are a little cheap. That’s the problem with minimalist writing sometimes. It doesn’t have the content beneath it. Some minimalist writers, they want to have the literary language, but they don’t want to have the passion or they don’t want to risk too much. That kind of writing is cheap. It doesn’t dare to stand out there naked. When I see that kind of writing, I always wonder, as a reader, Am I not worth it? Why don’t you want to give me any of your skin?

Do you ever worry about overcompensating, putting too much passion, too many demons in?

There was a review of Karate Chop in the Los Angeles Times that explained it nicely. The reviewer said that if the emotions contained in my stories—enormous emotions—were allowed to take up more space, it would be too much. But they’re contained in this small form. They’re squeezed in so that they don’t overflow, so that the emotions don’t drown. But really, I don’t think I could be melodramatic. If I were, there might be a housewife on the outskirts who found it interesting, but everyone else would run away, including me. To write like that would be talking down to people. My characters get messed up because that’s what life is about. Literature should express that human condition—we’re all gonna get slapped around.

Several of these stories focus on relationships between parents and children. Is there something about that moment when a child first sees a parent as a real person—or even weak, bad—that you find particularly poignant?

Don’t we all remember that moment when our parents stopped being heroes? I do. I love my parents but I figured out they were human beings and that not everyone in the world saw them as the wonderful people I perceived them to be. But some of these stories didn’t start out with a parent-child relationship. The story “Duckling,” for example, was based on a man I knew. I was riding with him on the subway in New York, and we saw a homeless guy twitching across from us. He pointed and said, “This is how you can tell that humankind are actually beasts.” That was just the worst thing I’d ever heard said about a human being. And I thought, God, I hope this man doesn’t have daughters. How bad would that be? So I imagined him saying this horrible thing about his child’s mother, as he does in the story.

The men in your stories seem to be especially, and casually, cruel to women—wives, girlfriends, daughters. There’s an idea in the story “Karate Chop” that to be alive is to be careless of others. I found that very chilling and wondered how it came to you.

In “Karate Chop,” that idea comes from the character, Annelise, who’s telling us the story. She strives to see the good in everyone. She looks at the hand of the man who’s been beating her, and she sees that it’s soft and a little red over the knuckles, from the beating, and that it was once a child’s hand. Many of my characters are like that. They’re innocent, unaware of how bad the world can be. They fixate on how they want to see the world and get slashed about by what it really is. I have a lot of faith in humankind, but I’m aware of how screwed up we are and how we’re not good to each other and how we come with agendas and scars and dreams. We involve one another in these things. People get hurt by the human relationship. It’s our paradox—how much we need each other and how much we batter each other.

Do you set out to push your characters toward the line between normal life and something terrible? Are you trying to find out how far they’ll go and where they’ll break?

The Danish title of this book, Kantslag, actually means four different things. First, it means a karate chop. Second, it means a rimshot against a drum. Third, it is the chip that breaks off a piece of porcelain. And fourth, it means the battle that you experience on the brink of something new. That’s where I always put my characters, and it’s why I gave the book this title. They’re on the brink of revelation, or being pushed over the edge. I find that it’s when we’re on these borderlines that we start to think for ourselves.

Animals in Karate Chop don’t often get off too easily either. Is there something about that kind of violence that you find especially telling about a person, or a character?

It has a way of involving the reader. Look at the story of this giraffe in Denmark right now. Everybody’s talking about it. Meanwhile, there are thousands of people being killed in Rwanda again, but we’re talking about the giraffe. We relate to these animals for some reason. We find them innocent and pure. It’s crazy, but when we really want to feel empathy for something, it’s easier with animals, because they’ve never betrayed us, never forgotten to pick us up at school, never done any of the things that human beings do to each other. In the story “Mother, Grandmother, and Aunt Ellen,” the mother squeezes a rabbit to death—basically it’s the same thing she’s doing to her girls—but the rabbit gets to us much harder, because of this weird thing between humankind and animals.

There’s an eponymous heron in the book that seems like it might be an exception to all this supposed empathetic connection between man and beast.

I saw that heron once. That animal wasn’t innocent. I used to see it when I was walking in the Frederiksberg Gardens, in the gray weather, the sleet. This heron looked like death. That image was so specific, and I matched it up with an image of an older man I used to see, standing at the lake where they feed the birds, in the middle of all this shit and this army of herons. They seemed right together.

The sequence of the stories in Karate Chop feels deliberate and meaningful, more so than a typical collection. Was the right arrangement something you worked hard to find?

It was very hard. My very good editor and I spread all the stories out on the floor and just pored over them. You have to make sure that people enter the book in a certain way. It’s almost like a novel. The first story has to be a peek, and then with the second story you really grab them. That’s why “The Buddhist” is second in this collection. It keeps people reading. And you have to close the book right, too. The last line of the Wadden Sea was perfect for that: “She said the Wadden Sea was an image in the mind’s eye, and that she was glad I wanted to go with her into it.” It had to be the end. It’s a puzzle.

Two of the stories are set in New York, both of them looking at characters from the economic fringes. Is that the New York that stayed with you from your time here?

The poverty of some people in New York is so enormous compared to the richness of others. There are worlds next to worlds next to worlds. In my story “The Big Tomato,” for example, some people have the problem of their tomatoes being too big and other people have the problem of delivering these giant tomatoes on bicycles with no brakes. It’s like we’re not living in the same New York. But at the same time, it’s what I love about the city. It has a bowel and intestines. And drama. Although I’ll admit that sometimes I see things a bit wrong here. When I lived in New York before, it was summer. I haven’t been back in years, and when I got here on Sunday, I saw all these people wrapped up in big coats, looking miserable, and I thought, Wow, look at all the homeless people. The financial crisis has really crippled this city. But my friend pointed out that it’s winter, and that this is just how New Yorkers dress in the winter.

Has this experience—publishing in the U.S.—been very different from what you’re used to in Denmark?

Denmark is such a small country and the literary community is small, too. Everyone’s been married to each other or they’re someone’s kid. It’s extremely claustrophobic. And because it’s such a small country, we’re told to always keep our expectations low. We have this thing in Denmark called Jantelaw—this idea from the writer Aksel Sandemose—that says you should never think that you’re better than anyone, and if you step outside this small circle, this community, we’re gonna get you. But here, in the U.S., it’s been completely different. The generosity here is so much bigger. Fellow writers have been so good to me. There was Junot Diaz, and Fiona Maazel has helped me so much. I’m awestruck by it. There’s also a professionalism about the industry. Working with Graywolf Press and with Brigid Hughes at A Public Space, it’s been incredible. These people aren’t afraid to think big, to fly a little.

I’d be curious to hear your take, getting thrown into the American publishing world, on the future of the book. In the U.S., we seem to be in another period of deep anxiety. Are things any more optimistic in Europe?

It’s the same. They’re all scared of digitalization. They think it’s going to kill everything, but of course it won’t. That’s bullshit. People have always told stories. Writers just need to find a way to express their stories in the new language. That’s why I tried to write a whole book only in headlines, because that’s how we communicate now. You’ve got to get with the times and find a way to be creative with this, instead of crying in a corner. As a medium, the book is having a hard time now because it has to change its form, but it won’t disappear. I still want to read books and I know a lot of people who want to read books.

One problem I see is that the big publishers here are extremely keen on only doing the safe thing and therefore only dealing with books that can sell so many copies that they have to buy storehouses just to hold them. But there’s a market for good literary fiction. I don’t want to write the storehouse books. I don’t want to read them. I want the good stuff and I know a lot of people who want the good stuff. I don’t understand why the big publishers don’t take care of that market. There’s so little of it in translation, for instance. The ones that have the money don’t have the courage. They make their money on Fifty Shades, the big ones, so they don’t do anything for writers who write other kind of fiction. That’s just a pathetic attitude toward art.

How to Photograph the Inside of Your Body, and Other News

If this digestive tract thrills you, imagine what a kick you’ll get out of your own! Image via Beautiful Decay

The eccentric poet Bill Knott once faked his own death, but last week he really died. (Unless this is one hell of an elaborate ruse.) He wrote of himself: “my poetic career is nugatory … no editor will countenance my work; i’ve been forced to self-publish my poetry in vanity volumes; i am persona non grata and universally despised or ridiculed by everyone in the poetry world.”

The truculent, condescending subtext of the word actually .

Checking in with Alejandro Jodorowsky, everyone’s favorite cult filmmaker: “‘Maybe I am a prophet,’ he said in 1973. ‘I really hope one day there will come Confucius, Muhammad, Buddha and Christ to see me. And we will sit at a table, taking tea and eating some brownies.’”

One way to get a glimpse at the inside of your body: swallow a frame of 35 millimeter film, “folding each piece in a brightly colored capsule that allow[s] for the acids and bodily fluids to process the film with minimal risk of colon damage.”

Punishments of the future: “What happens to life sentences if the human lifespan is radically expanded?”

March 17, 2014

See Me

Adolescence, pen pals, and the Manson girls.

The Manson girls. Photographer unknown.

When I was thirteen, I had a yearlong correspondence by mail and over the phone with Rodney Bingenheimer. A peculiar icon of the sixties and seventies, Bingenheimer had opened a famous club on the Sunset Strip; he was a live-in publicist to Sonny and Cher, he accompanied David Bowie to London, and through his adjacency, his fandom, and his prescient taste, he eventually achieved fame himself.

We had met briefly on the sidewalk of my small hometown when I walked past a café table where he sat with a group of friends. He was a lackluster presence, not even as tall as I was—red hair cut into a chunky bowl, wearing a blazer over a shirt printed with a Red Army star. He was fifty-five then, though to my thirteen-year-old self he looked much older. His voice had the tremulous, feminine quality I would later read about in memoirs of the golden days of Los Angeles, his eyes slightly out of focus.

“Tell her she looks like my first love,” he half whispered to the group surrounding him, a group casually dressed, but alert with the nervous air of support people. They repeated his words to me, obediently.

“Give us your information,” one of his group said, all brisk business. “He’s very famous,” someone else said. “He invented the Ramones.”

Rodney blinked at me like a tired cat.

He seemed like the unpopular boys in my own grade, wounded in a vague way, his wrists as tiny as a child’s. Still, I wrote down my mailing address, vibrating with pleasure. Some girls, even at thirteen, probably knew not to do things like that. I wasn’t one of them. When I was offered any attention, I took it, eagerly. I look at pictures of myself at that age and wonder how plainly it was encoded in my face, the flash of a message: see me.

The letters from Rodney were as banal and girlish as the ones I wrote home from camp. The weather. Where he had eaten that day (often Denny’s). A snapshot of his car, a powder-blue Pontiac GTO, in front of a Tower Records in Los Angeles. Packets of photocopied images of his first girlfriend, Cathy. Her wholesome face on a magazine cover; the two of them pressed together in a photo booth. He wrote how he had loved her, and how I looked exactly like her. He said I should think about parting my hair in the center, as Cathy had. I squeezed lemon juice on my hair until it was crisp and sticky, and then I sat in the sun, hoping my hair would lighten to her shade of pale. I studied her face for signs of my own, noting her polyester miniskirts, the slim legs in tall boots. Her eyes rimmed in modish liner, the scarabs of her painted-on lashes.

He had been Davy Jones’s stand-in on The Monkees, he told me. I knew the name only because my mother had had a crush on Davy Jones when she was young, and on Ringo, too. It was better, she had told me, to have crushes on the uglier ones, because it was more likely they might want you back.

My mother didn’t ask where the letters came from. Maybe to her they looked innocuous enough: the envelopes covered in adolescent scribbles, the flaps shiny with stickers. She had six other children, four other daughters, all of us starting to learn the opaque equation of attraction, my father hissing at me under his breath to put on a bra.

* * *

Rodney and I spoke on the phone from time to time. He chatted as easily as a girl my own age. I told him about the eighth grade. About my friends. He wanted to know my favorite food (spaghetti). My favorite color (blue, but sometimes yellow). He wanted me to play his first love in the biopic Warner Brothers was making about his life. It may have been true that there were once plans, but in the years since, I have never seen evidence of such a movie. At the time, though, I was flattered. This was exactly what was supposed to happen: you were plucked from the obscure fug of your tiny hometown by the attention of a stranger, the mythic other who had decoded in you the precise features that added up to love.

My favorite books as a child: a girl lopes with wolves across flat Arctic lakes. A witch teaches her daughter how to practice white magic. A melancholy princess floats through the air. One morning, for whatever reason, these girls—described in the language of jewels, because that’s what they were—had been seen by someone else, had been handed the key to a deeper life. Getting people to look at you, I understood, was a way of getting things to happen.

An actual title of another of my favorite childhood books: Two Boys Noticed Me and Other Miracles.

Rodney Bingenheimer, 2011. Photo: Rick Hall

Rodney sent me band stickers and tour merchandise and five-page letters. He described going along on Seventeen magazine shoots with his first love, and he dropped names that meant very little to a folk music-loving thirteen-year-old: Captain Beefheart, Joey Ramone, Morrissey. He told me to listen to his radio show and he would say hi to me on the air. He asked me to send photos, but I had none I felt were pretty enough.

I can’t remember what I wrote back to him, but I must have written something, because his letters kept coming, on stationery printed with cartoon figures of a man on a moped or the Union Jack flag, in special air-mail envelopes I wondered at for their foreignness. He kept me updated on the movie. He called me from England, or Switzerland, where he explained he was having meetings with film executives. He told them all about me, he said, and they thought I sounded perfect for the movie. I would be famous, he said. I knew, even at thirteen, that it wasn’t true, but I let myself imagine it, too.

I stopped writing back when I got my first real boyfriend, a puddle-eyed hippie my own age who taped my baby pictures by his bed. Rodney’s letters and photographs went into the box in the attic that held my hemp friendship bracelets from camp, squares of poorly etched glass, and my eighth-grade yearbook, in which friends exhorted me to stay in touch, stay cool, never to forget the times we’d had. On my “Senior Page,” I declared that my ambition in life was to be a movie star and to “be fulfilled and happy in whatever I do.”

* * *

When I moved to Los Angeles as an adult to try to resurrect a lukewarm childhood acting career, I called Rodney Bingenheimer. By then I had read all about him in sixties memoirs—how he was a kind of token clown, rejected by even the groupies. I felt curious. I wanted to hear about Rodney Bingenheimer’s English Disco, I wanted to imagine him with Pamela Des Barres and Vito and Kim Fowley, scrabbling for love, inhaling Trimar off handkerchiefs. He never called back, though his phone number was still the same. I left two messages. I wonder sometimes if he was embarrassed about his letters, or had simply forgotten me, or whether, perhaps, I was now too old.

I did not become an actress, though I went on a lot of auditions for roles like rape victim. It was all the Christian money in movies, my agent had explained. Christians love a good rape, the ensuing opportunity for redemption. I’d gotten good at fake crying, a skill I further honed in an acting class in Culver City. The teacher, Judith, ran the class out of her garage. During my session, we were only doing scenes from Ingmar Bergman movies. The first day, sitting in a circle taking turns saying why we’d signed up, a plump girl with an oily forehead said she adored Ingmar’s work.

“I loved her in Casablanca,” the girl said.

I lasted less than six months in Los Angeles.

* * *

I kept reading about the sixties, but I grew less interested in good-natured Laurel Canyon crash pads, Rodney’s womanly face, Bebe Buell’s pet monkey. I became obsessed with the Manson girls. I was older than they’d been when they killed eight people, when they’d driven home on the Ventura Freeway, stopping at gas stations to clean blood off one another. I stayed up late into the night, reading the different books, watching the scratched videos on YouTube. In the photographs I saw of the girls—pictures striking for their strangely domestic quality—I recognized something of myself at thirteen, the same blip of longing in their eyes.

There was Susan Atkins, witchy and unrepentant, narrow faced and sort of perverse. Leslie, the pretty one—didn’t she know how pretty she was? Couldn’t that have saved her? Poor Patricia, with some kind of hair condition, her blunt man’s face. And Linda Kasabian with clarified features and an inescapable suburban sensibility: she named her baby daughter Tanya.

Those were just the ones who had been involved in the killings. But all the others: the girls who watched the children at a makeshift nursery by a waterfall. The girls who drove Doris Day’s son’s convertible to the grocery store dumpsters in Chatsworth to fill the trunk with melons and lettuce gone brown and wet at the edges. The girl who slept on two armchairs pushed together, watching over George Spahn, the blind eighty-year-old man who owned the defunct movie set where they all lived.

I thought if I knew what their days looked like I would understand what they felt. Did it help to know they passed the communal bowls of food counter-clockwise? That the dogs ate before the girls could? That Charles Manson had them hang bits of bone and feather in the trees so they could find their way around in the dark?

They drove homemade dune buggies around the ranch, Manson’s draped with a fur coat one of the girls had taken from her wealthy mother. They painted a school bus black and made porn movies with stolen NBC cameras. Angela Lansbury wrote her thirteen-year-old daughter Didi a note so if the police stopped her with Charlie, they knew her mother had given permission.

One August, I drove six hours south from Sonoma County to see the place where the girls had lived. The drive took me past the apocalyptic wind farms and down the bleached interstate, the exits littered with tomatoes that fall from the produce trucks. The ranch was ten miles outside of Los Angeles, in the commuter town of Chatsworth. I had to call my sister on the phone to give me directions to the place.

“Spahn,” I said. “Spahn Movie Ranch.” I heard her typing. “Wait, it’s loading,” she said. “It’s Santa Susanna Pass Road—” I found the place, across from a grim, corporate-looking Baptist church and adjacent to a baseball field. When I pulled my truck over, I saw the field was dotted with uniformed boys in the middle of a game, their avid parents watching from the low bleachers. What was this place I was going, my sister wanted to know. I told her it was where Charles Manson had lived with his followers.

“Is anything there anymore?” my sister asked. “No,” I said. And it was true—there was nothing. Just the scrubby rugged land, the eerie and jagged range of hills, like a real mountain range in miniature. I held up the book I’d brought, opened to a black-and-white photo of the ranch, and matched up the twin horizon lines. In 1969 there had been an entire movie set, a series of false-fronted western buildings: the saloon, Rock City Cafe, a jail, even an undertaker’s parlor.

Someone had left a grubby pair of men’s long underwear. There were a few rusted cans. The tall ragweed scratched my bare legs above my boots. All these things left behind were from people like me, and in that way were just distractions, the litter of the normal world.

I could have gone further onto the ranch land, like the people who write on the Manson message boards, message boards that never slow down or die. Some people had found a remnant of an old dune buggy, and there were breathless YouTube videos narrating the true pilgrim’s hikes into the upper reaches of the ranch: visiting the police lookout points, the place where they’d buried Shorty’s body. In the days after my trip, I watched those videos, and read the blogs devoted to tracking the Manson girls who are still alive, who now have families and jobs and ended up in places like Vermont and Arizona. In interviews, a few of them look wistfully into the camera. They speak fondly of their time on the ranch. It was something I could understand. They had been welcomed at the ranch, given nicknames both childish and aspirational. They had been held tightly and told they were unlike anyone else. I was not so different. We all wanted to be chosen in some way. Maybe it’s just an accident which women are chosen by violence.

I wonder all the time how easily things could have turned out badly for me; my life gone curdled and sour, ending viciously. The girls kidnapped by strangers, by handymen, by men who keep them in sheds or basements. If it hadn’t been Rodney Bingenheimer, a lonely and pitiable man, who had decoded my message—if it had been someone with more agency, someone like Charles Manson, who brushed his girls’ hair with his fingers and smiled at them, who told them to call him father. Or Jim Jones, cooing “darling” in his followers’ ears, and writing feverish letters to runaways like a jilted lover until they returned to the fold, to his ever-open arms.

I see it now, sometimes in my own face, but also in the faces of younger girls on the subway, their pinkies linked, their eyes darting and wounded. See me, they say. Their legs sheened with moisturizer, specked with faint bits of glitter. Braces thickening their mouths. The tightness of a pimple they worry slyly with their fingers, ashamed.

I try to smile at them, but it isn’t me they want.

Emma Cline is the winner of the 2014 Plimpton Prize. Her fiction has appeared in The Paris Review and Tin House. She is at work on a novel about the Manson Family.

Cat Fancier

From The Cat and the Devil.

“I sent you a little cat filled with sweets a few days ago but perhaps you do not know the story about the cat of Beaugency,” begins James Joyce’s The Cat and the Devil, first published in 1965. If you were lucky enough to get your hands on this book as a child, you know that the illustrations, by Richard Erdoes, haunt your nightmares for years, and that it’s quite impossible ever to think of James Joyce without visualizing the Mephistophilean entity pictured therein.

The story is based on an old French folktale: the desperate mayor of Beaugency makes a deal with the devil in order to get a bridge across the Loire. In exchange for the supernatural structure, the devil may claim the soul of whoever crosses it first. In the event, the townspeople foil the plot by sending over a hapless cat instead, and in the grand tradition of diabolical law, the devil is forced to abide by their reading of the contract.

James Joyce now has a second children’s book in print. The Cats of Copenhagen, published in 2012 by Dublin’s Ithys Press, is, like its companion story, based on a letter the writer sent his young grandson, Stephen. Both are playful, weird, lyrical, and, yes, completely straightforward. That said, in the opinion of some grownups, the books are not without subtext. As Anastasia Herbert, publisher of The Cats of Copenhagen, told the Guardian,

In early August 1936, Joyce had sent his grandson ‘a little cat filled with sweets’—a kind of Trojan cat to outwit the grown-ups. A few weeks later, while in Copenhagen and probably after hunting for another fine gift, Joyce penned ‘Cats’, which begins: ‘Alas! I cannot send you a Copenhagen cat because there are no cats in Copenhagen.’ Surely there were cats in Copenhagen! But perhaps not secretly delicious ones. And so the story proceeds to describe a Copenhagen in which things are not what they seem … For an adult reader (and no doubt for a very clever child) ‘Cats’ reads as an anti-establishment text, critical of fat-cats and some authority figures, and it champions the exercise of common sense, individuality and free will.

According to Maria Popova, Joyce was a passionate cat lover, and despised dogs in equal measure. Which makes it a bit strange that he would sacrifice his cat hero’s soul to the devil, but then, as we know, Joyce held an unromantic view of love. (“Love [understood as the desire of good for another] is in fact so unnatural a phenomenon that it can scarcely repeat itself, the soul being unable to become virgin again and not having energy enough to cast itself out again into the ocean of another’s soul.”) Besides, the Joycean devil seems happy enough with his bargain, a cat making for better companionship than a soul—and one presumes he has plenty of souls.

Here, in honor of the day, is a cat who looks like James Joyce.

Recapping Dante: Canto 21, or a Middle-Schooler’s Essay

This winter, we’re recapping the Inferno. Read along! This week: how to write a C- five-paragraph essay on canto 21.

Gustave Doré, Canto 21

As Dante enters the next ditch, he addresses his reader, saying he and Virgil have encountered things about which his “Comedy does not care to sing.” One has to wonder what Dante is seeing that makes him so overwhelmed. Upon reading the notes in the back of the book, a reader can discover that this area of hell is reserved for those who committed barratry, which, according to the American Heritage Dictionary, is “sale or purchase of positions in the state.” Because this sin is so similar to simony, which was punished in a recent canto, we can understand that Dante means for the reader to undergo a sequential experience—as our thoughts move from simony to barratry—and that the theme of this canto is motion. Following this theme, we can also see Dante go from a state of confusion and horror as the canto begins, and then to a state of fear as he encounters demons, and finally to a feeling of faith as he learns to trust the demons.

Dante spends a lot of time describing a vile lake that surrounds him and Virgil. It is made of boiling pitch—similar to modern-day tar—in which the sinners are forced to swim. The great detail he uses to describe this lake of boiling pitch (nine lines are dedicated to a small story telling the reader how it reminds Dante of Venetian ship makers) shows that he is clearly both captivated and terrified by it. Eventually, Dante sees a demon that further moves him into a mindset of absolute fear. He warns Virgil, who is less concerned. Dante then describes the way the beasts chase down a sinner who has come to the surface of the pitch, and how they rip him apart, because the sinners are supposed to stay below the surface. Already Dante has gone from a foggy notion of his surroundings to a very concrete sense of fear.

After the demons tear apart the sinner in a gruesome display, Virgil tells Dante to hide behind a rock for his safety. This is one of the only times in the book that Virgil has warned Dante to take cover and has given him instructions to ensure his safety. This fact sets this scene apart as one of extreme danger. Virgil then goes out, and as he is about to be attacked, he speaks to the leader of the demons and convinces him that he and Dante are on a divine journey and should not be harmed. After the negotiation, he calls out to Dante and almost mocks him for hiding, saying, “You there, cowering among the broken boulders of the bridge, now you may come back to me in safety.” This is the beginning of the third step in Dante’s transformation from fear to faith, as he learns that Virgil has secured them safe passage. The demons try to attack Dante, but the leader warns them not to, and puts together a team to take Virgil and Dante to their next destination.

Though the surroundings may appear safer than before, Dante remains apprehensive. When the demons escort the travelers, Dante begs Virgil to find another way to continue their quest, and wishes that they did not have to rely on the demons for help. Virgil assures him he needn’t worry. These words from his guide help put Dante into his final stage of faith, faith that the Demons might be there to help them in their divine quest. Finally, we see the demons make farting sounds with their mouths; the leader makes “a trumpet of his asshole,” indicating that between the demons there is a secret code that relies on farting noises. Dante must then realize that they are not out to kill him, but, instead, are goodnatured. To a reader, these demons become a source of comic relief, undoing the tension we felt when Dante was still mistrusting of them. It is clear that while at first he feared the demons, he has moved on to trust them.

In conclusion, canto 21 is evidently focused on the notion of movement: it offers a lot more action-based plot developments than previous cantos, and it also gives the reader a firsthand account of Dante’s transformation. Dante’s emotional range goes from confused, to scared, to accepting. From the many series of events that move the plot forward, to the emotional journey Dante undergoes, this canto has a great deal of momentum, and movement is one of its fundaments. It can also be said that as Dante grows, so does the Inferno as a book. As a result, not only do we see movement as one of the major themes of this canto, but the growth that follows this movement. Movement is not meant simply to take one from A to B, but to help one grow along the way.

To catch up on our Dante series, click here.

Alexander Aciman is the author of Twitterature. He has written for the New York Times, Tablet, the Wall Street Journal, and TIME. Follow him on Twitter at @acimania.

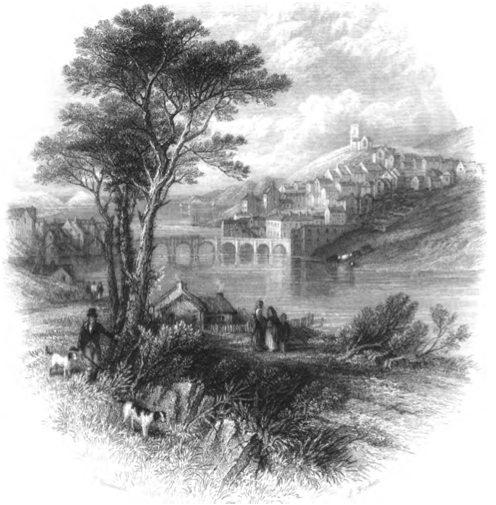

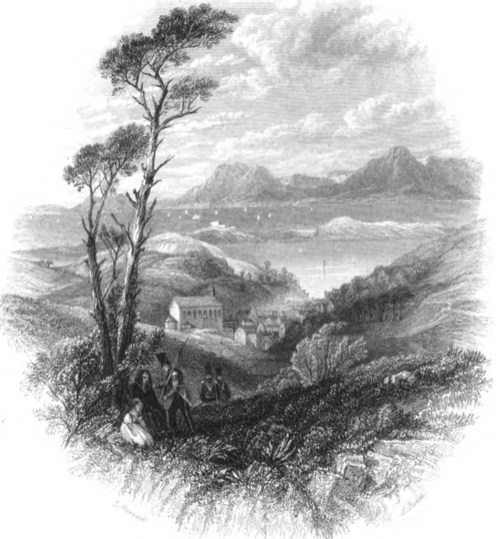

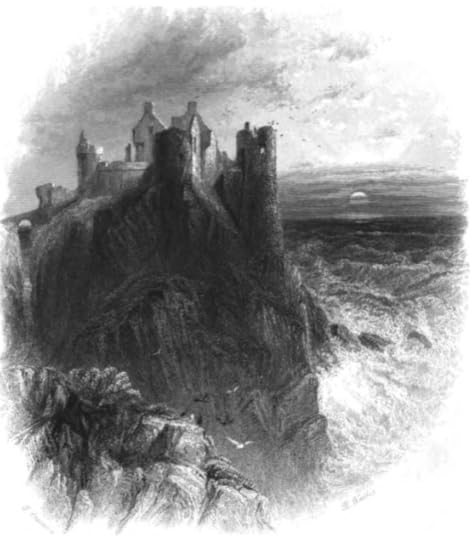

Ireland: Picturesque and Romantic

On St. Patrick’s Day, nineteenth-century illustrations of the Irish countryside.

Donegal Castle

McGillicuddy’s Reeks and the Upper Lake of Killarney

Killaloe on the Shannon

The Gap of Dunloe

Lower Lake of Killarney

Turk Mountain

The Irish Jig

Carrickfergus Castle

Fairhead

Lower Lough Erne

Irish Market Girl

Ballyshannon

Waterloo Bridge, Cork

Bantry Bay

Dunluce Castle

Londonderry

These remarkable illustrations are from Ireland: Picturesque and Romantic, an 1838 travelogue by Leitch Ritchie, Esq. But don’t be fooled: despite his book’s encouraging title and the meticulousness of these drawings, Ritchie was pretty hard on Ireland. His account, stuffy and imperial, presents a portrait of the Irish psyche scarcely more enlightened than a box of Lucky Charms, shot through with a kind of paternalistic shame:

The Irish are not lazy because they are Irish, but because, in the first place, they are only half civilized … their spirit is broken by ages of tyranny. They have crouched so long under the lash that they can hardly stand upright. They are brave from instinct, but cowards from habit; and the peasantry every day of their lives are guilty of as despicable acts of poltroonery, in their intercourse with the quality, as the serfs of the middle ages exhibited in their encounters with the knights.

Not, as you can see, ideal reading for St. Paddy’s Day—better to take the pictures and put someone else’s words with them. Here, then, is a more fittingly romantic tribute to Ireland: Patrick Kavanagh’s “Canal Bank Walk,” a sonnet written in 1958.

Leafy-with-love banks and the green waters of the canal

Pouring redemption for me, that I do

The will of God, wallow in the habitual, the banal,

Grow with nature again as before I grew.

The bright stick trapped, the breeze adding a third

Party to the couple kissing on an old seat,

And a bird gathering materials for the nest for the Word

Eloquently new and abandoned to its delirious beat.

O unworn world enrapture me, encapture me in a web

Of fabulous grass and eternal voices by a beech,

Feed the gaping need of my senses, give me ad lib

To pray unselfconsciously with overflowing speech

For this soul needs to be honoured with a new dress woven

From green and blue things and arguments that cannot be proven.

That’s more like it. Having been diagnosed with lung cancer, Kavanagh would take constitutionals along Dublin’s Grand Canal; he had disavowed hateful, negative verse and recast himself as a celebrant of “casual, insignificant little things.” In this later mode, he had a way of elevating the prosaic to the poetic, though I guess you could say that about most any poet. Paul Muldoon—who can, unlike me, speak with some authority about Ireland—puts it more compellingly in his Art of Poetry interview:

Kavanagh presented a version of Ireland that was still very much being lived, with the horses and the cartloads of dung. The winkers, and the belly band, and all the bits and pieces. The turnip barrow I mentioned earlier. The impedimenta of farm life, what happened at the crossroads. The world of these people seen from within and expressed from within in a way that really hadn’t quite happened for a while in Irish literature. The perspective of the peasant looking up to the man on the horse, rather than the Yeatsian perspective of the man sitting on the horse looking down.

Calling All Princesses, and Other News

Bell Telephones debuted the Princess phone in 1959. Image via Attitude Analyst

The OED has made its latest update. Among the new words added: wackadoo, toilet-paper (as a verb), cunt lapper, and assisted living.

Minneapolis’s Graywolf Press turns forty.

Evocative shots of New York’s 1964 World’s Fair recall a time when the future was full of wonder, typefaces were chunkier, and you could ride a giant tire like a Ferris wheel.

Why should you major in English? Because Barbara Walters and Mitt Romney did, of course!

“It’s little! … It’s lovely! … It lights!” An enlightening history of Bell Telephone’s 1959 “Princess phone,” “the first phone specifically created for teenage girls and women … in its beauty and its place in the home, [it] was the embodiment of perfect womanly qualities of the time.”

March 14, 2014

Paper Moon

Images via Amusing Planet

There is no time that is not hard and complicated. Disaster is never far away. But in the immortal words of Fred Rogers, “When I was a boy and I would see scary things in the news, my mother would say to me, ‘look for the helpers. You will always find people who are helping.’” This can be hard for grown-ups to remember when buildings explode or planes vanish out of the sky.

One of the true helpers, if you ask me, was Akira Yoshizawa, whose work stopped me in my tracks when someone shared it with me earlier today. “The grandfather of origami” was born on March 14, 1911, in Kaminokawa, Japan. Until his forties, he lived in poverty, choosing to devote himself wholly to the art of paper-folding. He was frequently inspired by nature.

With the publication of his first monograph, New Origami Art, in 1954, he gained substantial recognition, and shortly thereafter opened Tokyo’s International Origami Centre. By the time of his death, at ninety-four, his origami had been exhibited at the Louvre, he had been named to the prestigious Order of the Rising Sun, and his Yoshizawa–Randlett folding system, composed of the now-familiar arrows and diagrams, had become the worldwide standard.

While his craftsmanship and commitment were far beyond the reach of most people, Yoshizawa had an endearingly democratic streak; he often proselytized the meditative pleasures of origami. In his famous words, “Overall, I want you to discover the joy of creation by your own hand. … The possibility of creation from paper is infinite.”

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers