The Paris Review's Blog, page 722

March 28, 2014

What We’re Loving: Strokes, Sex Appeal, Splenetic Surfers

Emmanuelle Devos in a still from Just a Sigh, 2013.

If you saw American Hustle with your parents, as I did last Christmas, you will have noticed something that set it apart from pretty much every Hollywood movie of the last few years. I refer to the sex appeal of Amy Adams. Her hotness was a blast from the past, and not just because of the disco décolletage. For some reason, Hollywood doesn’t really do sexy these days, at least not in female roles—and certainly not compared to the French. Just think of Lola Créton in Goodbye, First Love or Adèle Exarchopoulos in Blue Is the Warmest Color—both playing teenagers with a soulful teenage horniness that’s taboo in American movies—or Marion Cotillard as a double amputee in Rust and Bone, or best and most recent of all, Emmanuelle Devos, the fifty-year-old star of Just a Sigh, who’s never looked better (which is saying something), and who smolders so intensely for Gabriel Byrne that the poor guy just sort of disappears off the screen. Until the actual love scenes, you hardly notice: this is a one-woman show. —Lorin Stein

Rodrigo de Souza Leão died shortly after the publication of All Dogs Are Blue, an autobiographical novel detailing his time in a Rio de Janeiro mental asylum. Souza Leão uses a kind of language his schizophrenia has taught him, creating a poetry that’s at one moment absurd—his two recurring hallucinations are Rimbaud and Baudelaire—and the next heartbreakingly self-aware. (“Is it the kiss of Judas? Will I betray my father in my madness?”) It’s an innovative, original book, though not an easy one to read. But then, as Souza Leão writes, “The truth can be a sloppy invention and still convince everyone.” —Justin Alvarez

When will spring arrive‽ Isn’t all this cold weather lovely though⸮ I love it—I hope it never ends؟ If you’ve been feeling that we have a lack of punctuation marks at our disposal—we don’t have a way to represent, for instance, an ironic question—then why not revive the obsolete irony mark⸮ It has a long history of failure in mainstream typography that you can read all about in Shady Characters: The Secret Life of Punctuation, Symbols, and Other Typographical Marks, by Keith Houston. But if you believe that to point out irony to an intelligent reader would defeat its purpose wholesale, perhaps you would prefer the percontation point, which was invented by the English printer Henry Denham in the nineteenth century—it’s meant as a visual indication of a rhetorical question. Or the interrobang, which combines the feeling of the exclamation point with the function of the question mark. Or my favorite, the love point, used to denote deep affection. —Anna Heyward

Geoff Dyer was not killed, or even, apparently, seriously impaired by his recent stroke, and he writes buoyantly about the experience for the London Review of Books. Ten days into his new life in Venice Beach, his vision went weird and his coordination abandoned him, and he stumbled about half-blind in perfect weather. His is a kind of coming-of-age story that reminds you how many such stories make up a life, whatever your age. —Zack Newick

If Girls has begun to grate, tune in to Broad City, written by and starring Ilana Glazer and Abbi Jacobson, produced by Amy Poehler. In many ways the anti-Girls, Broad City follows also-IRL best friends Ilana and Abbi as they blunder their way through New York: buying marijuana “like a grownup,” for example, involves the stashing of said marijuana in a very grown-up body part, while attending a roof party full of beautiful people has deeply weird consequences involving a pair of bearded DJs. Though the show is more sketch comedy than high-concept, the chemistry and timing alone of these two feckless oddballs make for some refreshingly killer comedy. —Rachel Abramowitz

On May 3, 1987, the Butthole Surfers played a show in Trenton, New Jersey that has since become the stuff of legend. This week, I read “How Did It Come to This?,” an oral history of the concert published online a few years ago. The Buttholes, as fans call them, really knew how to pull out all the stops. (And how to put them in; Gibby Haynes, their frontman, liked to remark onstage, “Don’t you hate it when your dad walks in and you have a wine bottle up your ass?”) They poured lighter fluid on the cymbals and lit them on fire; “there was the naked woman onstage and then Paul from the Buttholes pulled his pants down and was flipping his dick around.” When a security guard tried to put a stop to the madness, Gibby Haynes covered him in lighter fluid, too, and threatened to ignite the guy. For anyone interested in the singularly splenetic alt-rock subculture of the late eighties, this is an invaluable resource—and it is, in the extremity of the events it describes, almost endlessly quotable. “The Butthole Surfers’ music was totally over my head,” says one attendee. “It just sounded like a jet landing—forever.” —Dan Piepenbring

Facts First: An Interview with Michele Zackheim

From the cover of Last Train to Paris.

Michele Zackheim’s new novel, Last Train to Paris, follows the adventures of Rosie Manon, the fearless foreign correspondent for the Paris Courier. Spanning the better part of a century, from 1905 to 1992, the story takes us to the Paris and Berlin of the midthirties and early forties, during one of the most fascinating and shameful periods in modern history, the years leading to World War II. Zackheim was moved to write the novel following a strange discovery—in the thirties, her distant cousin was kidnapped and murdered in France by Eugen Weidmann.

I spoke to Zackheim via e-mail and telephone over a period of three months. Our conversations touched on her family history and writing methods, and the formidable research she brought to her new novel.

All of your books share a certain preoccupation with World War II. Why?

My family lived in Compton, California, an area that was declared vulnerable to an enemy attack. I was only four years old when World War II ended, but I remember small details—a brass standing lamp with a milk-glass base that was lit at night while my parents listened to the menacing news on the radio. The sound of night trains, which ran on tracks a block away. And of course—and this is hard to admit—my only sibling was born in 1944. Because I was the eldest, and because before her birth I had already experienced grim hardships, an intense sibling rivalry was born. I have to assume that she became part of my unconscious interest in war. These memories, along with the emerging news from concentration camps after the war, and my parents’ outraged and mournful whisperings in Yiddish, created an unconscious anxiety that I’ve been making work about all my adult life.

You wove the story of your cousin’s murder through your novel. Was the expansion and departure from the initial incident a natural progression for you?

I often start out writing nonfiction. But there’s a problem. It’s boring for me not to embellish—actually, it’s no fun. I did try, however, for a short time, with this book.

When I discovered that a distant relative of mine had been murdered in Paris in 1937, I was intrigued. I had discovered this story in a New Yorker essay by Janet Flanner. And then, to my surprise, I discovered that Colette and George Sand’s daughter, Aurora, was part of the story, too.

The only problem was that it would require me to stick clearly to the facts, as I needed to do with Einstein’s Daughter: The Search for Lieserl. That book was carefully vetted by the publisher—they were looking for factual errors, but my editor quickly learned that I could easily, unintentionally, be carried away by my imagination.

So I much prefer to invent my stories, even if they are originally based on fact.

In your novel, both Colette and Janet Flanner attend the trial of Ernest Vosberg—as they did Weidmann’s trial. Does it bear a close resemblance to the original trial?

Yes. In my writing I followed the trial with close attention. Both Flanner and Colette had attended the trial as reporters—Flanner for The New Yorker and Colette for Paris-Soir. I quoted verbatim from their news stories. The two lawyers are truly represented, as is much of their dialogue. I could not have written their arguments any better. They were brilliant.

How did Rosie’s character develop?

Rosie’s character developed backward and inside out. I first wrote the story in a male voice—a character named Jimmy Corso. I molded him into a sensitive man who was assailed by self-doubt, and at the same time, very curious. I liked him enough. Kent Carroll, the publisher of Europa Editions, bought the book. And oddly, I wasn’t excited—I was depressed. I felt as if I had created a paper doll and, although I missed the primary characters in my other books when I turned in the manuscripts, I didn’t miss Jimmy. Finally, I called Kent and told him that I didn’t want the book published. I needed to write it in a woman’s voice.

I gave Rosie the same professional qualifications as Jimmy. She has the same vulnerable nature, which makes them both sensitive in their interviews and observations of events. They have the same tough demeanor—impenetrable—and they have a similar family history. But I wrote Jimmy too soft for a man of that time, in that profession. When I transformed his voice into Rosie’s, she, being a woman and an outsider, made more sense, was more real.

Miriam, Rosie’s mother, is an archetype of anger—jealous, dominating, a mother who can neither love nor let go of her daughter. Have you known parallels in your life?

My own mother was an artist, a woman who never had a chance. She blew anger out of her nose like a dragon. On the other hand, she was charming and had many friends. As a child, I could never understand the opposition of her feelings. She was a talented woman. She had nowhere to go, except to take care of her children and be at home for her husband, who brought home the paycheck. I often get her mixed up with my grandmother. Their rage was communal.

Even as an older woman, my grandmother was a beauty. She roamed a few bedrooms in her time. One of her trysts was with Eugene Debs. She had a gorgeous sense of color and space. In New York City, during the twenties and thirties, and even until after the war, the family moved each year because the first month’s rent was free. By the time I became conscious of her apartment, she had accumulated threadbare Persian rugs from the streets or from thrift stores. They covered the floors and the daybed and were draped over the other worn, upholstered furniture. I always felt in her home as though I were in a story from the Arabian Nights. And she was angry. Very angry.

You came to writing from a background as a visual artist. Do you think in words or images?

I think in images, not words. It may be that I see interior sensations on the faces and in the movements of my characters within the visual context of their situations. A sudden jerk of the head, a change in a facial expression, a reflection of light on a wedding band.

For the new book I’m working on, I first determined who the characters were. Then I went on the Internet and searched for photographs of people who fit my imagined characters. I printed them out and placed them in frames that I’ve positioned on my desk. For six months now, I’ve been catching glimpses of them as I work, as I dust my desk, as I answer the telephone. Their images have become imprinted on my imagination.

Compared to the women, the men in the story have weaker personalities, yet they are competent and often lovable. Do you think this male portraiture is representative of life, or was it written to serve the purpose of your narrative?

The time in which I based the story was a confusing time for men. World War I had ended and another war was looming. I think that the idea of men having to face violence yet again put them in a difficult position. In Europe after World War I, there were thousands of villages of women left in mourning. Few men could be found—a reminder of what might lie ahead. I think that men are as varied in their cultural psyches as women. But many act as brutes, like the wine-soaked Mr. Ramsey in the newsroom, or the Nazi bodyguard who slams Rosie against a shiny black car. Men’s behavior fuels Rosie’s rage. So why should Ramsey deserve sympathy when he has made her life so miserable? On the other hand, why not? Today, I think women are more sympathetic toward men than Rosie is because we are more educated about the nuances of being a man. When Rose’s story takes place, the subject is still in stark black and white.

Were you influenced by any particular writers as you were creating this novel?

As the epigraph of Last Train to Paris, I use this quote from Mark Twain—“Get your facts first and then you can distort ’em as much as you like.” His semi-autobiographical book Roughing It influenced me. Well, that’s not altogether true. What really influenced me was an old brown writing desk with a green felt surface. Although I was born in Reno, Nevada, we lived up the mountain in Virginia City. My father was a schoolteacher at the First Ward School. When we left Nevada, he was given a desk and told that it had once belonged to Mark Twain.

My mother painted it a viridian green, and I remember my father telling her not to paint the bottom, because he had been told that Twain had signed his name there in pencil. Sixty-five years later my mother died, and I shipped the desk to New York. My husband took off the paint. While he was working on it, I looked for the signature. I found many, but no Mark Twain, nor Samuel Clemens. So I was influenced by the mystery of Twain’s imagination—and how you can make a book from an old wooden desk.

Emancipation Carbonation

A still from the famous “Diet Coke Break” ad, 1996.

The typo of the day, from a story in the Atlanta Business Chronicle—

Just one month after Diet Coke rolled out the first frozen carbonated beverage in the brand’s 31-year history, the product—Diet Coke FROST Cherry Slurpee—has been removed from stores because it did not free properly.

Lesson learned: brain freeze does not bring deliverance, even when it comes from a refreshing Diet Coke.

We Must Protect the Children, and Other News

Presented without further comment: John Updike’s shorts.

What if The Road, The Corrections, and Wonder Boys were children’s books? (The illustration of Alfred Lambert falling from the cruise ship is especially well done.)

Speaking of satirical children’s books: in the UK, Penguin has proven its humorlessness by suing the author of We Go to the Gallery, a brilliant parody of the Peter and Jane series. One panel is seen above. The lawsuit avows that We Go to the Gallery “pollutes the idyllic brand of Ladybird books … their argument is now fundamentally moral, not legal, and as such is an act of senseless and repressive censorship.”

And speaking of questionable litigation: here’s the history of late-night TV ads for unscrupulous lawyers. “There was an era before ads like these were allowed—and a big bang after which they couldn’t be contained. And now, the legal world is in a subtle, possibly endless civil war over how attorneys should advertise their services (and whether they should advertise at all).”

Today in interspecies communication: scientists can now translate dolphin whistles in real time.

March 27, 2014

Michael Bruce’s “Elegy—Written in Spring”

Edinburgh Castlehill in spring. Photo: Marianna Saska, via Flickr

Michael Bruce has a purchase on the springtime. He was born on March 27, 1746, just as spring was coming to Scotland, and his most enduring poem is “Elegy—Written in Spring.” The guy knows greenery.

Bruce—a Scotsman, as you may have guessed—was the son of a weaver; growing up, “his attendance at school was often interrupted because he had to herd cattle on the Lomond Hills in summer, and this early companionship with nature greatly influenced his poetry.”

And so it did: “Elegy” is a plain-and-simple celebration of companionship with nature; it’s unadorned and all the more beautiful for it. Bruce wrote the poem toward the end of his life, and its last stanza, which turns to gaze at death, is quietly devastating, especially since it comes after so many words devoted to the bliss and beauty of pastoral Scotland. The images here are classically, achingly bucolic: flowers, plains, furze. Verdant ground, ample leaves, and dewy lawns. On a day like today, when, in New York, the new season struggles to shuck off the dreariness of the last, “Elegy” is an ideal balm. If only it could bring the balmy weather with it.

‘Tis past: the iron North has spent his rage;

Stern Winter now resigns the length’ning day;

The stormy howlings of the winds assuage,

And warm o’er ether western breezes play.

Of genial heat and cheerful light the source,

From southern climes, beneath another sky,

The sun, returning, wheels his golden course:

Before his beams all noxious vapours fly.

Far to the north grim Winter draws his train,

To his own clime, to Zembla’s frozen shore;

Where, throned on ice, he holds eternal reign;

Where whirlwinds madden, and where tempests roar.

Loosed from the bands of frost, the verdant ground

Again puts on her robe of cheerful green—

Again puts forth her flowers; and all around,

Smiling, the cheerful face of spring is seen.

Behold! the trees new deck their wither’d boughs;

Their ample leaves, the hospitable plane,

The taper elm, and lofty ash disclose;

The blooming hawthorn variegates the scene.

The lily of the vale, of flowers the queen,

Puts on the robe she neither sew’d nor spun;

The birds on ground, or on the branches green,

Hop to and fro, and glitter in the sun.

Soon as o’er eastern hills the morning peers,

From her low nest the tufted lark upsprings,

And, cheerful singing, up the air she steers;

Still high she mounts, still loud and sweet she sings.

On the green furze, clothed o’er with golden blooms,

That fill the air with fragrance all around,

The linnet sits, and tricks his glossy plumes,

While o’er the wild his broken notes resound.

While the sun journeys down the western sky,

Along the green sward, mark’d with Roman mound,

Beneath the blithesome shepherd’s watchful eye,

The cheerful lambkins dance and frisk around.

Now is the time for those who wisdom love,

Who love to walk in virtue’s flowery road,

Along the lovely paths of spring to rove,

And follow nature up to nature’s God.

Thus Zoroaster studied nature’s laws;

Thus Socrates, the wisest of mankind;

Thus Heaven-taught Plato traced th’ Almighty cause,

And left the wond’ring multitude behind.

Thus Ashley gather’d academic bays;

Thus gentle Thomson, as the seasons roll,

Thought them to sing the great Creator’s praise,

And bear their poet’s name from pole to pole.

Thus have I walk’d along the dewy lawn;

My frequent foot the blooming wild hath worn;

Before the lark I’ve sung the beauteous dawn,

And gather’d health from all the gales of morn.

And, even when winter chill’d the aged year

I wander’d lonely o’er the hoary plain:

Though frosty Boreas warn’d me to forbear,

Boreas, with all his tempests, warn’d in vain.

Then, sleep my nights, and quiet bless’d my days;

I fear’d no loss, my mind was all my store;

No anxious wishes e’er disturb’d my ease;

Heaven gave content and health—I ask’d no more.

Now, spring returns: but not to me returns

The vernal joy my better years have known;

Dim in my breast life’s dying taper burns,

And all the joys of life with health are flown.

Fisheye (Riblje Oko)

Happy birthday to Joško Marušić, a Croatian animator whose fantastic 1980 short, Fisheye, often swims into my mind when I order seafood. I once came across the film on YouTube, very late at night—which is, as connoisseurs know, the best time to fall down the YouTube mineshaft.

Fisheye is an inspired blend of the macabre and the mundane. Its premise is simple: instead of people going fishing, fish go peopling. At night, these jowly blue creatures of the deep take to the land, a murderous glint in their eyes—they feast on the residents of a sleepy coastal hamlet. While they’re well-bred enough to use forks, they seem to have forgotten that forks are intended for use with food that has already been killed. And they spareth not the rod: children are maimed, old ladies clubbed. If this doesn’t sound like your cuppa, give it sixty seconds; you may find yourself, as I did, transfixed. Is the film best paired with a psychotropic substance? That’s not my place to say. (Yes.)

Marušić belongs to what’s known as the Zagreb School of Animation. In a 2011 interview—informative despite its clunky translation—he says,

The Zagreb School of Animation had its specific technological and “worldview” coordinates. The technological characteristic of the School was the so-called “limited animation,” which, in digest, means a complete commitment to stylization. It is customarily contrasted with the Disney-style “full animation”, where all characters are animated according to the strictly delineated canons of [“realistic”] animation. The School introduced the genre of animated films for adults, films pregnant with cynicism, auto-irony, and the relativization of divisions between people. In all great conflicts, our sympathy is with the “small man” who is most frequently subject to manipulation. This “small person” exists in all classes and all societies, and verily constitutes the most numerous sector of society, but remains powerless because he or she is not “networked.”

No Grownups Allowed

Photo: Dick Rowan, 1972

There are certain places—mostly playgrounds—that post signs advising visitors that no unaccompanied adults will be admitted without a child escort. Sometimes, these are practical concerns: jungle gyms and ball pits are not made to bear a grownup’s weight (This is to say nothing of creeps.) But maybe they are also meant to give kids a sense of specialness in a grown-up world.

There should be far more of these signs. In fact, they should be expanded to include “No unaccompanied adults on grounds of preserving their dignity” and “No unaccompanied adults on grounds of Baby Jane-style macabre-ness.” Signs for both these categories would bar adult entry to petting zoos; most merry-go-rounds, with special dispensation for the kind with brass rings; and any restaurants clearly intended primarily for little girls. (These prohibitions sort of apply to groups of wild teenagers who scare little children, but of course they know exactly what they’re doing and run the world.) It is not that I don’t understand a need for nostalgia and childlike wonder. But over the weekend—while I was accompanied by young children, may I add—I saw a young French woman texting as she rode the Central Park Carousel, so.

All of which brings us to the “Power of Poison” show and how, a few days ago, I found myself standing in front of a model witch stirring a fake, steaming cauldron, while surrounded by school groups. Which is great, if that’s what you want. It is a really interesting show, in fact—once you can swallow the sky-high “Special Exhibition” entry fee—which gets into the science, history, and lore of poisoning, while presenting a bunch of hands-on workshops and multimedia demonstrations by museum docents. If I were a child, I think I would have loved it. “Let the lady see,” one of the teachers instructed a little boy, and I had the grace to be embarrassed.

It is a funny thing to wake up one day and be “the lady,” a grownup who is defined by not having a connection to a child. It is not something one envisions. Sure, anyone can ride the carousel for three dollars. But when my friends asked me if I wanted to ride with their three-year-old, I shook my head, because I knew she would feel safer with one of her parents, and would say yes only to be polite.

It is, of course, dangerous to start thinking about The Catcher in the Rye every time one is in Central Park, or the Museum of Natural History, or feeling lonely for childhood. I felt sheepish when I pulled my old, middle-school copy off my bookshelf. But:

Then the carousel started, and I watched her go round and round … All the kids tried to grasp for the gold ring, and so was old Phoebe, and I was sort of afraid she’s fall off the goddam horse, but I didn’t say or do anything. The thing with kids is, if they want to grab for the gold ring, you have to let them do it, and not say anything. If they fall off, they fall off, but it is bad to say anything to them.

Of course, the old Central Park carousel burned down in 1950. The Catcher in the Rye was published in 1951, and the current one would not yet have been open. The new one also doesn’t have brass rings. But blurring these lines is what fiction is for.

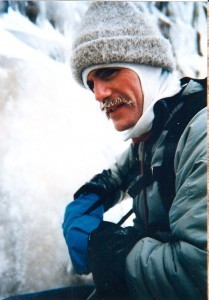

Finding a Life on the Edge

William Rich Holland, the author’s father, at Cape Elizabeth, 1983.

Every spring my mother flies out from her home in Walla Walla, Washington, to spend ten days with me in New York. Because her visits are often the only uninterrupted stretch of time we have together every year, they go mostly unplanned. “It isn’t vacation if you have to plan!” Mom has been known to say.

But when she made her way East in May 2012, just after my twenty-ninth birthday, her trip had an explicit purpose. It was my father’s fortieth reunion at Colby College, and she and I would be attending in his stead to represent his legacy and all that he had left behind.

In April 1989, at the age of thirty-nine, my father, Bill Holland, disappeared in an ice climbing accident in Jasper National Park, Alberta, Canada. While he was attempting an unroped descent off Slipstream—the three-thousand-foot frozen waterfall that runs along the treacherous east face of Mt. Snow Dome—he fell through a cornice of ice and, as the accident reports later concluded, likely into a crevasse. A subsequent weeklong storm system dumped an estimated thirty feet of snow in the area, delaying initial rescue attempts. By the time a search party could safely enter, the snowfall had been so significant that Parks Canada was eventually forced to abandon recovery efforts. My father was never found.

At five, I couldn’t imagine what had happened to my father on Slipstream. I couldn’t fathom the enormity of the mountains that took him, couldn’t grasp the idea of “cornice,” couldn’t picture a crevasse. I imagined instead a kind of one-dimensional character like the cartoons I watched on Saturday mornings, plummeting slowly backward in half time, enveloped in a silent whiteness. There was no sound of body on ice, no struggle, no final image of a lifeless man that my five-year-old brain could conjure up. In my mind, his body never came to rest.

As far as I was concerned, my father was not dead. All we had was the official report, filled with vague details of the incident: that he and his partner had disagreed on which decent route to take; that the weather had set in; that, in the blinding wind and snow, he’d neared the edge, gotten too close, made a misstep, fell. But words on paper mean little when you need sinew and substance. And what is death to a child but a great vanishing act? Without a body, there was no proof.

And so, in August 2010, after years of living in the shadow of that myth—of believing that he’d staged the whole thing and run away—when my mother called while I was grocery shopping and said the words, Laurel, they found your father, there was, in the nauseating silence before she could elaborate, a hesitation. Alive or dead? I had thought.

As it turned out, two college kids working for Brewster Bus Company that summer had found my father’s body while hiking at the base of Snow Dome on a day off. Even after all that time, he was fully intact—body, clothes, gear—with the rope he should have used in the decent still slung over his shoulder. It was hardly the homecoming I’d dreamed of for so long. But after twenty-one years, he was finally home.

The recovery of my father gave me permission to let go of the mistruths that had guided me since his disappearance, but it also revealed how much of him was still missing. With the few artifacts I had—letters, journals, photographs—I’d spent my youth Scotch-taping together a composite of him: I had tried, mostly in vain, to comprehend who he was, what shaped him, what drove him to climb. When I learned of the Colby reunion, I knew I’d find answers there, and maybe, if I were lucky, a part of him as well.

* * *

1988

The younger son of a registered nurse and a salesman for DuPont, my father wanted for nothing as a child. He attended Mercersburg Academy, summered in Maine, knew the comforts of a civilized and cultured life. He loved the outdoors and spent his boyhood, as boys do, climbing trees, hunting, fishing. But when, just after his college graduation in 1972, his best friend, Daryl, took him rock climbing for the first time, his entire life was recast. Seduced by the rocks, their steepness and height, my father fell in love. After the climb, he scribbled a manifesto of sorts on the front inside flap of his mountaineering guidebook:

In remembrance of my early years,

Spent in joy-drugged dreams of glorious peaks

Unclimable [sic], yet one day climbed;

To that hour, with the limits breached

I saw the Master, the mountain, and myself as one;

To that time when Life, the father, and Death, the son

Shared secrets, told stories and exposed lies;

Finally, to that moment I gained my precarious perch,

And saw the endless mists of truth come clear,

All in the eternity of a minute,

I dedicate this first ascent.

After graduating from college, my father spent a significant chunk of his errant twenties in western Canada studying its geology and obsessing over rock- and ice-climbing routes until he’d learned them by rote. By 1980 he had climbed nearly every peak in the Jasper area—Mt. Assiniboine, Popes Peak, Mt. Temple. He’d even made a successful assault on Snow Dome in the late 1970s. The Canadian Rockies were the training ground for the formidable alpinist my father became. And though he made his way back to the East in the early 1980s to start a life and a family, a part of him remained there forever.

All my life, I’d been told stories of my father’s incredible adventures in the outdoors, of his countless victories, his scores of near misses. Everyone—my mother, my uncle Tom, all the climbing buddies my father left behind—spoke of a man who derived profound clarity and a deep sense of self from his time in the mountains. Climbing for him was a meditation. It required problem-solving, precision, trust. “Being that close to death,” he once said to my mother, “you might as well be touching God.”

Despite his fierce intellect and borderline genius IQ, my father almost categorically defined himself in external terms: by his athleticism, his mountaineering coups, his physical capabilities and the limitations he often pushed to surpass. Around the time of his accident, he had been diagnosed with what was then known as manic depression, the most complicated case his psychiatrist had ever seen. From my own memories, I recall a vivacious man who trained neurotically for bicycling races, who played the guitar until his fingers bled, who once deconstructed the engine of his silver Scirocco and spent two sleepless nights putting it back together again. It was a condition defined more by its mania than its depressive episodes, but if he strayed too long from the mountains, the repetition of daily ritual and domestic routine often sent him into bouts of depression little could overcome. “There’s got to be more to life than paying the mortgage,” he once remarked to his older brother, Tom. Compromise and balance were never his friends.

My mother has often said that climbing was the great equalizer of my father’s condition. It forced him to focus acutely, whether on problem solving or survival, and with it came an incredible high. The more he climbed, the farther he could distance himself from the nadir of depression. But at thirty-nine his body was beginning to age. Because of prior bouts with frostbite and the extreme physical strain his body was constantly enduring, his hands, feet, and spine were painfully deteriorating. When he sought out a medical opinion, his rheumatologist gave him five to ten years before arthritis would take hold and he would be completely debilitated. For a man who derived a sense of self from what he could do rather than who he was, the thought of losing his ability to climb, to ski, to move in the way he knew how was a crisis of existential degree.

Obsessed with the notion that he could elude the inevitable, he ran faster, climbed harder, took more and greater risks. It was that fear—the fear of losing foothold on the person he thought he was—that drove him to Slipstream in the spring of 1989.

My father, it seemed, had been in perpetual search of himself. I knew his struggle with manic depression was part and parcel of his genetic fabric. But as I dug deeper, I wondered, too, if it wasn’t, at least in some measure, environmental—if this propensity to question himself and the world around him had been spurred by experience.

The fall my father entered Colby—September 1968—was a time of seismic changes in the social and political landscape: in race and gender relations, in academic methodology and the approach to higher learning. At Colby it was the last year that dormitories still had house mothers, when the house-sponsored panty raid was an annual event, and when acceptable classroom and dining hall attire—even mid-winter in Maine—consisted of dresses and skirts for women, coats and ties for men. But change was floating in the ether. An excerpt from the Fall 1968 Colby Alumnus captures the zeitgeist:

A permeating distrust emanates from that subculture—studentry—a distrust of authority and its products. It minds us of that commercial: But mother, I want to do it myself! No, nothing’s to be done for them. Maybe milieu, facilities, human begins, situations, all will help them sniff out whatever they’re after. Perhaps some will do it in a pattern of some sort, or in a design. But these may not be immediately recognized. In a way, it’s like that theorum [sic] of Dr. Wayne Butteau. Every experiment turns out right—but not necessarily as you expected it would—nor do you have to understand it.

At six feet two inches tall, my father, with his thick mop of dark brown hair, striking jaw line, and deep-set blue eyes that drooped slightly at the edges, was undeniably handsome. But when I look at photos of him from his college years, the images of the preppy kid with a lacrosse stick and slicked-back haircut in the fall of 1968 hardly resemble the leather-clad, guitar-playing ape who appears in the 1972 Colby Oracle. By the end of his sophomore year, he had grown his hair long, had learned to smoke pot, and had purchased a motorcycle, which, much to the chagrin of his roommate, he was constantly tinkering with in their common room at Kappa Delta Rho.

As his time at Colby pressed on, the change portended in the ’68 Alumnus continued to unfold. Anger over both the Vietnam War and the poor treatment of African American students mounted on campus. The relationship between the student body and the administration soured, and by 1970 students were taking over college buildings and demanding action. For the greater part of his four years there, Colby was literally overturned and run by its students. Woodstock, which he attended high and alone that famously rainy August weekend in 1969, was representative of everything my father was and went through as a twentysomething. It was a free and spirited time—but it was also a formative one, and the continued lack of academic structure for a young man with a manic predisposition gave way to a struggle between settling for the status quo and wildly defying it.

* * *

The author and her father, 1988.

The weekend my mother and I spent at Colby in the spring of 2012 opened a door to my father’s past I didn’t know existed. We visited his old haunts and met his former friends, from whom came an array of blackmail-worthy stories. There was the time he pushed his desk out the second-story window of his freshman dorm; the time he and a frat brother arranged for a back-alley exchange of LSD in downtown Waterville, but were robbed by the dealers; the time he purchased a tanning lamp in anticipation of a date with a Smith girl, but then nearly gave himself second-degree burns from lying under the UV light too long. Everyone expressed a heartfelt fondness for the charismatic guy they called “the Dude.”

The year my father and his classmates graduated from Colby was the year of the Watergate scandal, the year when the last American ground troops were withdrawn from Vietnam, and the year the Equal Rights Amendment was passed by the U.S. Senate. In a tumultuous time, his class had managed to find cohesion and solidarity. These were the people, I realized, who had been his family.

A few weeks after the trip to Maine, I was on a subway platform when I noticed someone had scribbled on one of the benches: COLLECT THE PARTS OF YOU THAT WENT AWAY. I thought about my father and how, for nearly all my life, I’d been amassing the parts of him that had gone missing. Until the spring of 2012, I hadn’t appreciated how much his view of the world stemmed from his college experience. He, like so many of his classmates, was a product of his upbringing and of his time. If the mountains were his home, Colby was where he grew up. The weekend in Waterville two years ago gave me that piece of my father. But I am still looking for the rest.

Laurel Holland is a writer and former actor in Brooklyn. She is currently writing a memoir, Spindrift: The Memoir of a Climber’s Daughter. Follow her progress on Tumblr at spindriftdiaries.tumblr.com.

Meet Me in Treasondale, and Other News

Before there was MFA vs. NYC, there was Flannery O’Connor, discussing the merits of an MFA program: “It can put [a writer] in the way of experienced writers and literary critics, people who are usually able to tell him after not too long a time whether he should go on writing or enroll immediately in the school of Dentistry.”

The love letters of a young Ian Fleming reveal him to be a jealous, sadistic romantic: “I would have to whip you and you would cry and I don’t want that. I only want for you to be happy. But I would also like to hurt you because you have earned it and in order to tame you like a little wild animal. So be careful, you.”

Beware intemperance! Exhumed from the Library of Congress: a 1908 map depicting “the negative consequences of drinking and ungodliness, using an imaginary set of railroad lines, states, towns, and landmarks.” Highlights: Selfishburg, Hypocrisy Heights, Lewd Castle, Whiskeyton, Gossip Center, Presumptionville, Treasondale, and Embezzle City.

John Coltrane’s tenor saxophone will join the collection of the American History Museum. (This year also marks the fiftieth anniversary of his seminal album A Love Supreme.)

On CNN’s coverage of Flight 370: “This willingness to fixate on one big story and sensationalize it reflects CNN’s growing embrace of the phenomenology of news. It’s an approach that emphasizes the viewer’s experience of singular news events as much, if not more than, the news itself.”

March 26, 2014

Stupid Is

Do people still read The Stupids, that classic series of children’s books written by Harry Allard and James Marshall in the seventies and eighties? They must, right? They’re too good. Making fun of fools may not be officially acceptable these days, but few books are so perfectly calibrated to a child’s sense of humor. And I don’t imagine most children are in any danger of confusing the Stupids’ aggressively literal naïveté with real-life intellectual deficits. As the School Library Journal opined in a starred review of The Stupids Step Out, “Even youngest listeners will laugh with smug superiority as they follow these good natured dummkopfs from departure to journey’s end.”

But one naysayer—who gave the book a one-star review on Amazon—had this to say:

My seven-year-old recently brought this book home from his school library. I found it very offensive, because I think it teaches children that it’s funny to call others “stupid.” I cannot think of a circumstance in which it is appropriate for a child or an adult to use this word towards another person. I was so upset that I wrote a note to the school librarian.

In fact, “stupid” is an awfully harsh word. I was reminded of this yesterday when I stopped into a deli to buy a packet of cold medicine. There was something of a line, headed up by an older woman with a Russian accent, tall, elegant, and swathed in a mangy fur, who was screaming angrily at the hapless owner, “No plastic! No plastic! Are you stupid?! I said no plastic!” When he managed to interpret her wishes and eventually handed her a paper sack, she responded, “I SAVE ENVIRONMENT,” which seemed debatable, but as we know, every little bit helps.

Then, near my house, I snapped a picture of the following sign, in the window of a local furniture store:

“The Stupidity Ends This Week.”

But does it? Does it ever really end?

Here is what was strangest about the incident at the deli. After the vigilante environmentalist received her bag and, somewhat mollified, proceeded to sail out, an old man, who had been eyeing her with distinct admiration, sprang forward to get the door.

“Allow me, madam!” he said, his extravagant bow completely untinged with mockery. The lure of the forbidden, I suppose.

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers