The Paris Review's Blog, page 719

April 7, 2014

Nothing Is Alien: An Interview with Leslie Jamison

When Leslie Jamison and I met outside the Glass Shop, an airy café in Crown Heights, I noticed her left arm was sporting a wide, wordy tattoo. It was in Latin, and she spared the embarrassment of translating it—“I am human; nothing is alien to me.”

Too often, Leslie says, people treat tattoos as an invitation to intimacy. Strangers on the subway ask her to relay the story of her tattoo without a second thought, much as they would, in offering a seat to a pregnant woman, ask for the details of what’s growing inside of her. But in Leslie’s case the tattoo does point to an intimate story—or rather, to a whole constellation of intimate stories that Leslie offers in her essay collection The Empathy Exams .

“I am human; nothing is alien to me” is the epigraph to the collection. It is a quote that has been casually misattributed to Montaigne, John Donne, Karl Marx, and Maya Angelou, but it actually comes from The Self-Tormentor, a play written by Terence, the ancient Roman slave turned playwright. It is the thread that connects such different yet equally luminous works as “Grand Unified Theory of Female Pain,” “Pain Tours,” and “The Devil’s Bait”—meditations on how to feel pain, both physical and psychic in nature, and how to regard the pain of others in a way that respects their humanity. Having read The Empathy Exams, I can begin to appreciate why Leslie has made the small, if painful, jump from writing about the body to writing on the body.

Leslie and I circled this conversation so many times at the Glass Shop that we decided to revisit it one morning in late October at my apartment in Brooklyn, and later that day, on the Metro-North to Yale University, where we are both finishing Ph.D.s in English literature. Most of the time, the tape recorder was on, but sometimes I switched it off so we could gossip idly, and forgot to switch it back on until Leslie was already halfway into a thought on feminism I wanted to preserve. But if this interview reads like the midpoint of a conversation that’s been taking place for some time now, that shouldn’t prevent you—the reader—from making sense of it. After all, you are human. This will not be alien to you.

The most ungenerous criticism of the collection that I could imagine is, Oh, she keeps putting herself in these positions to experience pain or woundedness so she can have something to write about. How narcissistic. I can see people thinking as they’re reading, She’s a real glutton for pain.

I guess that’s why it felt right to put “Grand Unified Theory” at the end of the collection. That idea of being drawn to pain is starting to emerge as a pattern in the essays themselves, and the final essay speaks to that directly. What position of pride do I have in relationship to these experiences?

There’s a basic and important distinction to draw between positions I inhabit as somebody who has experienced some kind of trauma and somebody who’s seeking out pain. Going to the Morgellons conference is a choice in a way that getting hit in the street isn’t. But the collection chooses to bring all of those experiences together in a certain way—what kind of appetite is being spoken to there? In certain ways, as a writer, you do profit off your own experiences of pain, and there’s a way of seeing that profit that’s wholly inspirational—in terms of turning pain into beauty—and a way of seeing it that’s wholly cynical—in terms of being a “wound dweller” in a corrosive or self-pitying way. The honest answer—to me—dwells somewhere between those views.

In the final draft of the Morgellons essay, I narrate the experience of having a parasite, but in an earlier draft I talked about how I deployed that story in Austin. Because I did deploy it. I was a little confused about how I was trying to deploy it, but it felt resonant to me, like I was trying to tell people, I have been looked at by a doctor in the same way that you have. There was some genuine empathy in that, but it was also instrumental—as in, I think you’ll trust me more if I tell you that I’ve been in some version of that position.

One of the things I noticed in reading the final essay, “Grand Unified Theory of Female Pain,” was that feminism as a word or a concept doesn’t come up that much, even though you’re articulating a theory of pain that is unique to women. When did you realize gender was going to play such a pivotal role in your writing?

Yale was one of the first places where I began to feel the role of gender in conversations, where I felt self-conscious about what I had to say. It felt like there were schisms along gender lines in terms of who was speaking with what kinds of authority and who wasn’t. It’s not like there weren’t a lot of exceptions to that, but up until then I had absolutely felt that being a woman hadn’t affected anything. It hadn’t affected where I’d been able to study or the awards I’d gotten. I just hadn’t felt it in the room before.

The world of academia sensitized me to inhabiting my female identity in a different way, but intuitively that essay had its roots in my life. That was where the urgency to speak was coming from—this question of how to speak from different kinds of injury without inhabiting the role of a victim, or falling into this feeling of shame about taking refuge in that role. Shame doesn’t exist as an emotion without the projected or perceived sense of judgment coming from somewhere else.

This is what Eve Sedgwick writes on shame. The performative utterance “Shame on you!” transforms and intensifies the relationship between the “you” that’s being addressed and the “I” that’s doing the shaming.

That traction is where a sense of electricity comes from. I was talking to a friend of mine, a filmmaker, telling her about someone who’d made fun of me for constantly taking recourse in the language of “heat.” I always talk about essays that way. I’ll say, I just try to follow where the heat is. I guess it’s a kind of unconscious sports metaphor.

Or it’s a narc metaphor. You’re trying to find out where the guns are hidden, where the essay is packing the heat.

Yes! Packing some emotional tension. My friend and I were talking about what that phrase means—“following the heat”—or what I mean when I say it, and I do think that there are certain emotions that feel to me like signposts, pointing at something important happening under the surface. Shame is definitely one of those emotions. Whenever we feel shame it’s a mark of some deep investment or deep internal struggle. But what I hadn’t thought about before this conversation is how the shame is also always pointing to some kind of conversation, some kind of argument that’s happening.

Absolutely. So other than the interlocutors that you flag—like Sontag, for example, who’s all over this essay collection—who are your projected interlocutors? Who’s on the other side of the conversation, shaming you?

That was actually something I struggled with a lot during different revisions of “Grand Unified Theory of Female Pain”—I was responding to something very ambient, something I believed in partially because of how many other women felt it too. I was afraid I was looking for scapegoats, voices saying, Don’t play victim. Sometimes the mouthpieces I found were women who had already internalized a larger or more nebulous imperative. What I see in Girls, for example, is this hyper self-awareness. When two girls accuse each other of being wounds—“No, you’re the wound!”—they’re quoting something without definite edges. They’re quoting this ambient energy of judgment all around them. They’re parroting something else. About three of four drafts into the essay, I found the medical study that I cite—“The Girl Who Cried Pain”—and it felt like proof that this nebulous effect is actually manifest in palpable ways.

Since I finished that essay, one of my best friends had an experience where she was in a serious amount of pain that wasn’t taken seriously at the ER for about ten hours—and that to me felt like this deeply personal and deeply upsetting embodiment of some of what was at stake in my essay. Not just on the side of the medical establishment—where pain is perceived as constructed or exaggerated—but on the side of the woman herself. My friend has been reckoning with her own fears about coming across as melodramatic. That’s the sense of urgency beneath the essay. I want to make a case for some world in which that fear is dissolved, that fear of being melodramatic.

Have you never had that moment of frustration with a friend where you think they’re talking too much about their woundedness? Is your empathy limitless?

The moments that really frustrate me are the moments where people seem to be asking for sympathy in this very coded—not quite passive-aggressive, more like passive-confessional way—when they suggest that something has been hard but refuse to outright say it. One version of this is talking about a really difficult experience in an intentionally coy or jaded way—where there’s not just a plea for sympathy but also a plea for admiration. Admire my stoicism. It’s a brittle crust performed over the feeling. But there are so many reasons people do that—deep pain or trauma makes expression difficult for a thousand reasons. I do think sometimes when I talk about my own medical history, I’ve just talked about it so many times that it doesn’t have a lot of affective charge anymore, and I think of friends who’ve had really hard things in their lives that make it almost more exhausting for them to go through the whole spectrum of their own emotions every time they talk about it…they genuinely don’t need any particular affective response from anyone, so they’re saving them the hassle. It’s not necessarily coming from shame or a passive aggressive plea for sympathy. It’s just a trodden path.

My parents are both physicians, and I’m always conscious of how they tend to quantify both the act of suffering and pain relief. Have you encountered different or competing ways in which other people conceptualize empathy?

My parents are both physicians, and I’m always conscious of how they tend to quantify both the act of suffering and pain relief. Have you encountered different or competing ways in which other people conceptualize empathy?

That makes me think about my own relationship to my parents’ professional lives. I’ve started thinking more about what my parents do and how it relates to what I write about, and how it relates to empathy more generally. My dad is an economist who does global development research—what he practices is a kind of quantifiable empathy, trying to empathize with systems rather than people. His research is devoted to trying to figure out cost-effective ways to ease global disease burden—and in a way that’s like trying to figure out what’s wrong with the system, what’s causing the most aggregate suffering, and then thinking about how to address that suffering in the most efficient way. The texture of it is so absolutely different from what I do and what I’m invested in, but I feel like his work prompts me to think about empathy in slightly different terms.

Do you show your essays to the people who are in them? The one that struck me in particular was Charlie, the marathon runner you visited in prison, in “Fog Count.” Were you nervous showing him that essay? What was his response like?

I had always intended to show that piece to Charlie, but when I was working on it with Roger Hodge—who edited it at Oxford American—he was very clear about that not being possible. Journalism 101, he said. You can’t show the essay to its subject. So I didn’t show it to Charlie and that made me feel anxious. He ended up loving the piece. But that piece is one where I’m corroborating his story more than I’m pushing back against it. There are moments that I see around Charlie—like the moment where I talk about feeling his anger in the margins—moments when I’m thinking a little outside the story he’s telling. But generally I’m supporting his account of his own life.

Another thing that made a big difference in Charlie’s situation is that he’s used to public attention—and he likes public attention—so having his life exposed wasn’t intrinsically violating. But when I write about my family—and I haven’t written about them much that’s been so much trickier for a lot of reasons. Regardless of the substance of what I’m saying, the simple fact of saying it—in a public context—can feel violating.

Does the same hold true for the piece about Morgellons disease, “The Devil’s Bait”? Because Morgellons sufferers like a group of people who actually would really appreciate the kind of attention that’s being brought to them. I started itching when I read that piece.

My dad has shown that piece to a couple of his colleagues who are doctors and some of them itched too! That felt like triumph to me. If I can make the doctors itch, then there’s some circuit of identification that’s been closed or connected.

You’re absolutely right about Morgellons patients—not only are they comfortable with the idea of being written about, they really want that. The pain of their disorder is the pain of misunderstanding and invisibility. Part of the reason I felt self-conscious was because I wasn’t giving them exactly the kind of visibility they wanted. There are fibers, it’s real. That wasn’t the piece that I was writing. I didn’t feel like I’d made any promises that I was failing to deliver on, but I’m also a pleaser. I think it’s really hard to be a people pleaser and a nonfiction writer. You don’t leave your personal self at the door when you write, and you still have to deal with all the personal ramifications of what you write. The part of me that wants everyone to love me all the time is very troubled by the idea that I would write something that someone didn’t want to hear.

What do you think is the right way to teach empathy?

The moments that seem truly empathetic to me take a different shape than what I would have expected. For example, I was talking to a cardiologist once about my heart condition—this was after I’d had a surgery that failed and I’d been on one medication that had failed—and I was going to see this doctor for a second opinion. At that point I was sick of spending time in hospitals—and I was sick of dealing with the condition—so I started getting emotional as I was telling him my story, and then I started getting more emotional because I felt ashamed about getting emotional. Some feeling like, People have to deal with such hard stuff, why am I crying about this? Which just made me cry more. My aunt was with me for that appointment, and the doctor just started talking to her instead—in this incredibly graceful way. He could see I just needed a break. He could sense what was going on with me—or making a guess about what I needed—and there was something about the specificity or the flexibility of that response that felt organically sensitive to what was happening between us in that moment. It didn’t come from some formula or sheet or set of rules.

Could we assign The Empathy Exams to medical students who want to behave more empathetically?

I think about that article published in the New York Times recently—that reading literary fiction makes you more empathetic—because it felt to me that there were meaningful results in those studies, but I wasn’t sure what they were. You read something for three minutes and then perform better on a test? It’s measuring something, but I don’t know what that something is.

It would seem that what fiction can do is bring you into some kind of continuous narrative—not just give you some three-minute injection of imagined experience. The difference between literary fiction and melodrama might be embedded in the idea that, with melodrama, you actually couldn’t feel as deeply in just three minutes, because anything you felt would be coming from some impulse or reaction that was already there—a situation or memory or archetype or stock response. So I don’t know what teaches empathy.

If you operate under the premise that everybody already has some experiences that could be sources of empathy for them—I wonder if there’s some process of coaxing people into tapping into that knowledge. Dissolving those boundaries between professional identity and personal experience is actually also part of what I’m trying to do with the collection. I want to blend the professional texture of journalism with the weird feeling of someone peeling off a Band-Aid in front of you.

An extended version of this interview appears in The Empathy Exams.

Recapping Dante: Canto 24, or Serpent, Ashes, Rinse, Repeat

Gustave Doré, Canto 24

We’re recapping the Inferno. Read along! This week: a swarm of snakes and a sinner with a sense of privacy.

Let’s begin by addressing the fact that these similes are getting out of hand. In the early parts of his poem, Dante’s similes were often only three lines long. Now—just as he did in the beginning of canto 22, when he describes battlefield scenes while traveling with the demons—he presents us with a long, roving simile about a peasant who sees the snow melt and knows it is time to herd his sheep again.

At the end of canto 23, Virgil realized there was no longer a way to pass from the realm of the lead-cloaked sinners to the next ditch—the bridge is out. This is one of the few indications (like the sinner crucified to the ground in 23) that the geography of hell changes over time. But soon, seeing that Dante is anxious and scared, Virgil devises a plan to get them over to the next area by scaling a few boulders. Dante, daunted and exhausted, admits that “were it not that on this side of the dike the slope were shorter—I cannot speak for him—I would have given up.” This is the sort of phrase that translators and scholars will laugh at, because it’s an example of Dante’s subtle, ironic sense of humor: he announces that he cannot speak for Virgil, and yet has done so for the entire length of the poem so far.

As the two climb, Dante stops to catch his breath. Virgil, strangely, does not rebuke him for being slothful, but speaks words of encouragement and tells Dante that fame does not come to the lazy. It’s a lovingly brusque bit of advice—it sounds almost like a reflection on Dante’s life beyond the poem, much like Prospero’s monologue at the end of The Tempest. Dante regains his courage and continues walking, and even tries to speak in order to show Virgil just how unwinded and energetic he is.

As they reach the next area, Dante hears a voice. He can’t seem to discern where it’s coming from—this won’t be resolved until the next canto. He struggles to see what’s in front of him, as it is very dark. Here, again, Dante gives us a rare glimpse into what hell might look like. Our contemporary notion of hell would suggest that the only source of visible light comes from high flames or the iridescent glow of boiling lava, which is almost ridiculous and cartoonish, but Dante never really addresses where light in hell comes from. Through the darkness, he asks Virgil to lead him to safety; the next thing Dante sees is a swarm of snakes jumping and attacking a fleet of running, naked sinners, which is clearly enough to make him forget about the eerie ghostlike voice. A snake darts through the air and bites a nearby sinner. Instantly, the sinner turns to ash, only to regain his human shape. (This might explain what happens to the sinners who are torn to shreds by the demons in the earlier canto.)

This sinner is Vanni Fucci di Pistoia, who stole ornaments from the chapel of St. James. He let someone else take the blame, and the fall guy was put to death. (Note to self: when choosing a partner for a heist, choose wisely.) Vanni Fucci, however, plays a strange role among the sinners that Dante meets—he’s one of the few who does not want to be interviewed, or even seen, in his current state. Many of the earlier sinners ask Dante to remind the world of their names, but this one seems ashamed to have been discovered. Filippo Argenti, in canto 8, spoke to Dante with a sort of sparring antagonism, but Vanni Fucci is almost furious. (The Hollanders point out a similarity between this scene and the Garden of Eden, where Adam does not want to be seen naked.) In an act of retaliation, Vanni Fucci tells Dante that in the near future, the white Guelphs will be attacked and chased out of Florence. “And this I have told that it may make you grieve,” the sinner says. Many times have sinners predicted Dante’s exile—clearly it’s a touchy subject—but the language of this prophecy is by far the most oracle-like. It’s also the last time a sinner will tell Dante about the poet’s future.

To catch up on our Dante series, click here.

Alexander Aciman is the author of Twitterature. He has written for the New York Times, Tablet, the Wall Street Journal, and TIME. Follow him on Twitter at @acimania.

The Original E-Book, and Other News

As obituaries and touching remembrances of Peter Matthiessen poured in this weekend, The New Yorker made some of his travel writing available to nonsubscribers—specifically “Matthiessen’s mesmerizing account of his journey, by ship, to the Amazon and throughout the wildernesses of South America.”

Tales of Faulkner in Hollywood: “‘Abandon hope, all ye who enter here.’ The quotation from Dante is what Faulkner considered a fitting road sign for drivers to see as they crossed the border into California.”

Before Americans loved baseball, we gathered to take in another grand national pastime: competitive walking. It was, if you can believe it, even stranger and blander than it sounds.

The irredeemably cheery mascots on cereal boxes are staring directly into your child’s soul, experts say. “Researchers found that children’s cereals are typically placed on the bottom two shelves and the mascots deploy ‘a downward gaze at an angle of 9.67 degrees.’”

For the origins of the e-book, look to the floppy disk. Specifically, look to Peter James’s Host, a novel published on two disks in 1993. It “has now become a historical artifact, accepted into the Science Museum's collection as a very early electronic novel.”

Archipelago Books turns ten.

April 5, 2014

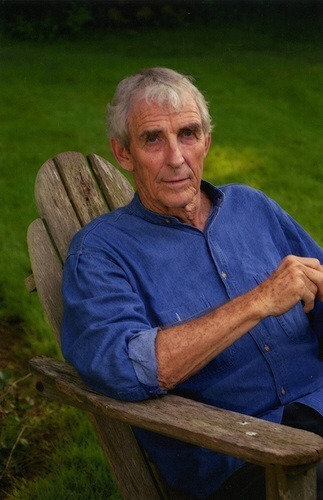

Peter Matthiessen, 1927–2014

Linda Gavin/Courtesy of Riverhead Books

We have received word that Peter Matthiessen, a founding editor of The Paris Review, died today after a long battle with leukemia. A Zen priest, novelist, environmentalist, and two-time winner of the National Book Award, Peter was a heroic figure to generations of readers, including our own. He lived a life of adventure but was, even in public, the first to admit his vulnerabilities and flaws. As a writer, he held himself to the highest standards—his own—even in the face of incomprehension or disregard. As the most senior member of our board, and the last living founder of the Review, he was unfailing in his encouragement and love of this magazine; we have lost a progenitor, a guiding spirit, and a cherished friend.

INTERVIEWER

You are one of the few writers ever nominated for the National Book Award in both fiction and nonfiction. Define yourself.

PETER MATTHIESSEN

I am a writer. A fiction writer who also writes nonfiction on behalf of social and environmental causes or journals about expeditions to wild places. I have written more books of nonfiction because my fiction is an exploratory process—not laborious, merely long and slow and getting slower. In reverse order, Far Tortuga took eight years, At Play in the Fields of the Lord perhaps four, and the early novels no doubt longer than they deserved. Anyway, I have been a fiction writer from the start. For many years I wrote nothing but fiction. My first published story appeared in The Atlantic the year I graduated from college and won the Atlantic firsts prize that year; and on the wings of a second story sale to the same magazine, I acquired a noted literary agent, Bernice Baumgarten, wife of James Gould Cozzens, the author of a best-selling blockbuster called By Love Possessed, whose considerable repute went to the grave with him.

INTERVIEWER

And when did you start your first novel?

MATTHIESSEN

Almost at once. It was situated on an island off the New England coast. I had scarcely begun when I realized that what I had here at the very least was the Great American Novel. I sent off the first 150 pages to Bernice and hung around the post office for the next two weeks. At last an answer came. It read as follows: “Dear Peter, James Fenimore Cooper wrote this 150 years ago, only he wrote it better, Yours, Bernice.” On a later occasion, when as a courtesy I sent her the commission on a short story sold in England, she responded unforgettably: “Dear Peter, I’m awfully glad you were able to get rid of this story in Europe, as I don’t think we’d have had much luck with it here. Yours, Bernice.” Both these communications, quoted in their entirety, are burned into my brain forever—doubtless a salutary experience for a brash young writer. I never heard an encouraging word until the day Bernice retired, when she called me in and barked like a Zen master, “I’ve been tough on you because you’re very, very good.” I wanted to sink down and embrace her knees.

Read Matthiessen’s Art of Fiction interview and his story “A Replacement,” and listen to him on the art of travel writing.

Peter Matthiessen, 1927 – 2014

Linda Gavin/Courtesy of Riverhead Books

We have received word that Peter Matthiessen, a founding editor of The Paris Review, died today after a long battle with leukemia. A Zen priest, novelist, environmentalist, and two-time winner of the National Book Award, Peter was a heroic figure to generations of readers, including our own. He lived a life of adventure but was, even in public, the first to admit his vulnerabilities and flaws. As a writer, he held himself to the highest standards—his own—even in the face of incomprehension or disregard. As the most senior member of our Board, and the last living founder of the Review, he was unfailing in his encouragement and love of this magazine; we have lost a progenitor, a guiding spirit, and a cherished friend.

INTERVIEWER

You are one of the few writers ever nominated for the National Book Award in both fiction and nonfiction. Define yourself.

PETER MATTHIESSEN

I am a writer. A fiction writer who also writes nonfiction on behalf of social and environmental causes or journals about expeditions to wild places. I have written more books of nonfiction because my fiction is an exploratory process—not laborious, merely long and slow and getting slower. In reverse order, Far Tortuga took eight years, At Play in the Fields of the Lord perhaps four, and the early novels no doubt longer than they deserved. Anyway, I have been a fiction writer from the start. For many years I wrote nothing but fiction. My first published story appeared in The Atlantic the year I graduated from college and won the Atlantic firsts prize that year; and on the wings of a second story sale to the same magazine, I acquired a noted literary agent, Bernice Baumgarten, wife of James Gould Cozzens, the author of a best-selling blockbuster called By Love Possessed, whose considerable repute went to the grave with him.

INTERVIEWER

And when did you start your first novel?

MATTHIESSEN

Almost at once. It was situated on an island off the New England coast. I had scarcely begun when I realized that what I had here at the very least was the Great American Novel. I sent off the first 150 pages to Bernice and hung around the post office for the next two weeks. At last an answer came. It read as follows: “Dear Peter, James Fenimore Cooper wrote this 150 years ago, only he wrote it better, Yours, Bernice.” On a later occasion, when as a courtesy I sent her the commission on a short story sold in England, she responded unforgettably: “Dear Peter, I’m awfully glad you were able to get rid of this story in Europe, as I don’t think we’d have had much luck with it here. Yours, Bernice.” Both these communications, quoted in their entirety, are burned into my brain forever—doubtless a salutary experience for a brash young writer. I never heard an encouraging word until the day Bernice retired, when she called me in and barked like a Zen master, “I’ve been tough on you because you’re very, very good.” I wanted to sink down and embrace her knees.

Read Matthiessen’s Art of Fiction interview and his story “A Replacement,” and listen to him on the art of travel writing.

April 4, 2014

What We’re Loving: Dead Poets, Dead Magazines, the Dead Zoo Gang

A still from Jean-Pierre Léaud’s 1958 audition for The 400 Blows.

In December of 1891, Walt Whitman contracted pneumonia. He was by then a celebrity poet and his deteriorating health had for a long time been media manna. The New York Times sent a reporter to Camden in 1888, and updates on Whitman’s health were published continually over the next few years—see 1890’s “Walt Whitman Has a Bad Cold.” By 1891, the end was within sight, and the paper published daily dispatches with headlines like “Walt Whitman Slowly Dying,” “Walt Whitman Still Lingering,” and “Walt Whitman About the Same.” Readers were made privy to such personal details as Whitman’s caloric intake (two oysters one day; a mutton chop another), his mindset (“he is perfectly rational”), and his doctor’s solemn belief that Whitman would last but a handful of hours more. He died on March 26, 1892. —Zack Newick

The best part of The 400 Blows is when Jean-Pierre Léaud ad libs an intake interview at reform school. Over the weekend a friend sent me the film test that got him the part. You can just feel Truffaut’s excitement at having found the child actor who would become his alter ego. The kid is pure heartbreaking charm. —Lorin Stein

Every couple of years, I revisit this documentary on the late broadcaster Victor Packer—hands down, one of the best things I have ever heard on the radio. Packer was, to put it mildly, a man of tremendous energy and varied interests. The portrait that emerges, by the Yiddish Radio Project, is that of an eccentric—but also of another era. It’s twelve minutes very well spent. (Packer, incidentally, is voiced by Christopher Lloyd.) —Sadie Stein

In “The Dead Zoo Gang,” a novella-length article published on The Atavist, Charles Homans tells the story of a group of international thieves known for robbing unlikely targets: taxidermists, antiques dealers, and natural history museums. They steal rhino horns to sell to buyers in Asia, and it’s been the work of law enforcement agents across the world to catch them—a difficult task, mainly because the thieves all seem to hail from an impenetrable subset of an already insular and poorly documented community, the Irish Travellers. Homans’s slow-building depiction of this community fascinates me. The Travellers are Roma-like nomads that exist on the outskirts of Irish society; they move from town to town in their trailers, congregating just once a year for, among other things, wedding celebrations so raucous they spawned a reality series, My Big Fat Gypsy Wedding. They speak a patois of Irish Gaelic and English and are organized in wildly complicated extended-family groups. And, most important, some of them—patriarchs whose net worth is estimated to be between 275 and 690 million dollars—appear to run scams and criminal activities (to say nothing of the odd legitimate business) on every continent except Antarctica. This a deep rabbit hole, but you won’t regret following it to its conclusion. —Tucker Morgan

Aspen, “the first three-dimensional magazine,” was published irregularly by Phyllis Johnson between 1965 and 1971. Lucky for us, UbuWeb has digitized the entire archive, with work by Marcel Duchamp, John Cage, the Velvet Underground—even films by Robert Rauschenberg and László Moholy-Nagy. Browse the full collection here. —Justin Alvarez

Our Spring Revel is next week, so I had to get my suit tailored—a new experience for me. (Another new experience: owning a suit.) As I handed it over to the kind Korean lady who will, God willing, make me look presentable, some lines from Mark Leyner’s Et Tu, Babe sprang to mind, and I had to hold back laughter. “In 1987,” Leyner writes, “I enrolled in a twelve-step program for people who pistol-whip their tailors. First I had to admit that pistol-whipping my tailor was, in fact, a problem. Today I take life one day at a time. Each day that passes without my having pistol-whipped my tailor is a victory … a solid step toward recovery.” I very suddenly couldn’t not imagine pistol-whipping this lovely Korean woman. I felt like a monster. My strain must’ve been visible; she asked if I was okay. I wasn’t. I’m still not. —Dan Piepenbring

One can only hope that the Police Blotter journalists over at the Brooklyn Paper moonlight as noir novelists. Their writing about the “Stiletto stabber,” a “high-heeled femme fatale and her gang of male goons” who stomped all over a man’s face on March 21, is as hardboiled as anything in Elmore Leonard or Dashiell Hammett. The jocularity of “the dental damage the deadly dame did” undoes any po-faced pretensions. Elsewhere, “rapscallions,” “bandits,” “crafty crooks,” “galoots,” “louts,” and “lowlifes” “skedaddle,” “brandish,” and “scram.” While the language belies the dreadfulness of the deeds—this is real life, after all—article titles like “Sands of Crime” and “Loosey Vuitton” suggest that a dash of gallows humor is the best antidote to such a dire beat. —Rachel Abramowitz

I’ve never liked the descriptor experimental in front of novel or writing, but in the case of Sergio Chejfec’s novel My Two Worlds, recommended and lent to me by Justin, it feels correct—Chejfec writes as if he’s testing the weight-bearing limits of normal prose. His narrator, a man a few days shy of his fiftieth birthday, walks through an unfamiliar city in Brazil, looking for a park and having trouble finding it. As he wanders the city in expansive and trailing sentences, his digressions and asides become the story, and the whole notion of storytelling, of using sentences to tell a story, comes under subtle scrutiny. —Anna Heyward

Every time I see that film still of Jennifer Connelly shielding her face in Russell Crowe-as-Noah’s chest, as he glares powerfully out at the apocalypse, I want to scream. It feels so indicative of Hollywood fare these days: there are movies about men that are supposed to appeal to men and women; there are movies about women that are designed only to appeal to women. So it is with fiction, too—the notion that there’s “fiction” and "women’s fiction.” Whose fault is it? Marketers! Here, a primer on “pinkification.” —Nicole Rudick

Lonely Hunter

A still from The Shop Around the Corner, 1940.

“That’s it!” someone exclaimed to her friend. “That’s the place where they meet!” She was standing in front of an Upper West Side coffee shop that figures in a pivotal scene in the 1998 romantic comedy You’ve Got Mail. They snapped a picture, they went in; I guess it was their destination. It takes all kinds, of course, and New York is all about finding your own city within a city. Hadn’t I passed a Friends bus tour in the West Village the week before?

I’ve always really disliked You’ve Got Mail, without being sure why. It’s not just that it’s twee and treacly, or feels dated. It’s not merely that it’s such a pale shadow of The Shop Around the Corner, the 1940 Ernst Lubitsch classic to which it is an ostensible homage. I remember seeing You’ve Got Mail when it came out and stalking out of the theater afterward, surrounded by my bemused high school friends, obscurely convinced that the filmmakers did not understand love. What I knew from love is unclear—I had never had anything resembling a relationship—but it’s certainly true that something about the film got under my skin. And now I begin to see that this something was, and is, about loneliness.

Like The Shop Around the Corner, the Nora Ephron rom-com centers around a pair of correspondents who fall, anonymously, in love—via letter, and, in the 1998 version, over AOL—but who hate each other in their real lives. And of course, the point is, the letters are their “real” lives.

In You’ve Got Mail, although the characters are ostensibly literary, the subject doesn’t come up too much in their cute, fast-paced, IM bonding. This is itself a departure from the original source material, albeit a natural one. The characters in The Shop Around the Corner (itself adapted from the Hungarian play Parfumerie) bond over classical music and, especially, Russian literature rather than snappy repartee. But even this is not the point.

In You’ve Got Mail, the Tom Hanks character is a big-box bookstore magnate driving Meg Ryan’s Upper West Side indie bookseller out of business. (Yes, I know: how quaint.) He is much richer than she, and her business is imperiled, but neither character is poor—and, critically, neither works for anyone else. Both have self-absorbed romantic partners who are easily discarded so that the leads can get together.

The Shop Around the Corner is a paean to loneliness: its sadness, yes, but also its power and its possibility. These characters are not bored urbanites who, with love at home, have idly logged on and fallen into flirtations. They are solitary young people who have deliberately set out to meet someone via a lonely hearts club, and find an escape from the grind of their jobs—in a perfumery in Miklós László’s original play, a luggage store in the Lubitsch film. Their lives are not their jobs; they are doing dull work for bosses, and probably always will. This is not a source of discontent; they find satisfaction in music and books, and as such, the epistolary romance is for these characters a lifeline. A couple of yuppies emotionally cheating on their partners just doesn’t have the same power.

Now, Jimmy Stewart and Margaret Sullavan were hardly everyman, and the 1940 Budapest portrayed on the sound stage is remarkably free of any geopolitical strife. But The Shop Around the Corner is realistic about the high stakes of loneliness. Is there a contemporary mainstream romance in which the characters don’t have the possibility of increased material success, and where the risk of being alone is considered dramatic tension in itself? And even when the characters are content with love, it is not exactly the end, in and of itself, that we have come to expect of modern movies. What these characters are looking for is companionship: people to share tastes and opinions with—an alternative to living, and being, alone.

The film is good because it is about risk: true risk, emotional risk. And the difficulty of exchanging the ideal for the real. Here is what Alfred Kralik, played by James Stewart, says in The Shop Around the Corner: “The boss hands you the envelope. You wonder how much is in it, and you don’t want to open it. As long as the envelope’s closed, you’re a millionaire.”

Fantasy has its place. The people who go to that café have their own kind—and that’s as real as anything. Besides, at the end of the day, that kind of romance is helping to support a small business, filled with actual people.

Andrew Pekler, Cover Versions

Andrew Pekler is an electronic musician based in Berlin; Resident Advisor has described his music as the “cold alien groove of a midnight jazz café reemerging in the world of clicks and bleeps.” I came to him by way of a video, “Composition No. 1 for Electronic Toothbrush, Voice, and Synthesizer,” in which he plays a Philips Sonicare toothbrush—with his mouth, in the usual way—to harmonize with a Moog Prodigy synthesizer. It’s an entrancing wash of beautiful, dentally hygienic sound.

Pekler works primarily from found materials. His latest album, Cover Versions, draws from the music and imagery of postwar exotica records—those kitschy aural forays to faraway lands, rife with congas, vibraphones, and theremins. With an eye toward a certain aesthetic, Pekler bought dozens of secondhand records and appropriated their music and their covers for his own work. Cover Versions was printed in a limited run of three hundred (all of them, alas, long since spoken for), each with its own individually designed cover; featured here are thirty of Pekler’s favorites. He explains his process:

I picked records out of bargain bins and charity shops. I was looking for cover art with certain motifs:

Couples in silhouette

Sunsets/sunrises

Ships/boats

Mountains/alpine panoramas/nature

Female faces in close-up

Candles

Rose petals/flower petals on pianos

Still life

Abstract geometric patternsUsing the records from those sleeves as sound sources, I recorded a dozen or so tracks. The tracks on Cover Versions are titled according to the records from which they were assembled.

Then I covered all the text on the covers with the multicolored lines and dots and circles—all materials from standard office supplies. For the back covers, I printed two-sided inserts with credits/track titles on one side and miniature images of some of the other covers on the reverse, taking up the idea of the generic “also available” inner sleeves that labels such as Atlantic or Impulse used to use.

All in all, I made three hundred covers. At the Laura Mars Gallery here in Berlin, I put together an installation that was basically a record shop, but one that sells only one record (in three hundred different covers). The records were sorted in sections according to their cover motif. Pretty much everyone who came in looked at every single record in the shop—and they kept turning the record around to look at the back, although all the back covers were identical.

Cover Versions Album Preview by Andrew Pekler

A Week (or More) in Culture: Mimi Pond, Cartoonist

We fly from our home in Los Angeles to York, Pennsylvania, so that my husband, the artist Wayne White, can begin building an art installation commissioned by York College of Pennsylvania. It will be constructed inside an historic former Fraternal Order of Eagles Hall in downtown York, now an organization called Marketview Arts. All of York is crazy historic, dating back to 1740! Temporary capital of the Continental Congress! Articles of Confederation drafted and adopted here! Home of the Underground Railroad! WHAT? This is a mind-blower for a history-loving girl from Southern California, where they tear down anything older than 1967 and replace it with a building made out of Popsicle sticks and Elmer’s Glue.

Our hotel, the Yorktowne, was built in 1926. And that’s not even OLD here. But it’s old-school enough that they still have actual room keys. And phone-booth rooms. And long spooky hallways. Three movies immediately come to mind: Barton Fink, The Shining, Groundhog Day. There is a tiny stuffed goat in the lobby.

I discover York to be a veritable museum of architecture: everything from Colonial-era buildings to stodgy Victorians that look like mini-Smithsonians to glamorous Art Deco storefronts. It’s simultaneously adorable and awe-inspiring and strange, since the place is kind of empty and mournful now, making me imagine I am in a graphic novel by the cartoonist Seth.

I discover York to be a veritable museum of architecture: everything from Colonial-era buildings to stodgy Victorians that look like mini-Smithsonians to glamorous Art Deco storefronts. It’s simultaneously adorable and awe-inspiring and strange, since the place is kind of empty and mournful now, making me imagine I am in a graphic novel by the cartoonist Seth.

Sunday, March 1

York is not only OOZING with historic architecture but also once was a bustling mini-metropolis, presided over by titans, veritable TITANS, of industry. They used to make BIG HEAVY STUFF here! Air conditioning! Steam en gines! Railroad manufacturing! Wrought iron! It reminds me that our nation was once a place where we MADE THINGS instead of a fourth-rate power that only produces reality television and fat people and crybabies. They still make enough things here—like potato chips and Harley Davidson motorcycles and barbells—that they bill themselves as “the factory tour capital of America.”

gines! Railroad manufacturing! Wrought iron! It reminds me that our nation was once a place where we MADE THINGS instead of a fourth-rate power that only produces reality television and fat people and crybabies. They still make enough things here—like potato chips and Harley Davidson motorcycles and barbells—that they bill themselves as “the factory tour capital of America.”

Yes, Hershey, Pennsylvania, is just down the road, and here’s a tip for you dirty-minded folks: no one here seems to think it’s funny when you ask if that’s on the “Hershey Highway.” I mean it. You’ll get blank looks. Plus? The factory tour at Hershey is a fake factory tour because the real plants (nontourable!) of the Mighty Hershey are spread out ALL OVER THE WORLD. This means No. Chocolate. River. CRUSHING DISAPPOINTMENT!!!!

One of the things I always do when in a new town is make a beeline to the the closest thrift store. At the one here, I find the ULTIMATE SOUVENIR, since Three Mile Island is only thirty-three miles from York.

Besides this sightseeing, Wayne and I have our noses to the grindstone. Wayne is from Chattanooga, Tennessee, and he always has the South in his back pocket. The galvanizing event for him here was that York was, in 1863, occupied by Confederate troops en route to Gettysburg—y’know, for that big do. General Jubal Early and his men held York hostage for three days, demanded a hundred thousand dollars, and finally settled for $28,000, some shoes, and food. It was a humiliating experience for the people of York at the time. So what is Wayne building inside the venerable Fraternal Order of Eagles hall? GIANT CONFEDERATE CARDBOARD PUPPETS, of course. I joke and tell him  that now he’s the Confederate general who has taken the town by storm and has requisitioned all the Yankees to do his bidding. Happily, the local Yankee art community here seems to have forgotten the trouble that General Early and his men put them through and flock to volunteer tirelessly and enthusiastically on Wayne’s project. Me, I find a quiet corner to work on part two of my graphic novel, Over Easy. It is so much cozier to work by the light of a Three Mile Island lamp. And you don’t even have to plug it in!

that now he’s the Confederate general who has taken the town by storm and has requisitioned all the Yankees to do his bidding. Happily, the local Yankee art community here seems to have forgotten the trouble that General Early and his men put them through and flock to volunteer tirelessly and enthusiastically on Wayne’s project. Me, I find a quiet corner to work on part two of my graphic novel, Over Easy. It is so much cozier to work by the light of a Three Mile Island lamp. And you don’t even have to plug it in!

Friday, March 7

As if finding the lamp weren’t exciting enough, tonight at our hotel there is a ballroom-dance competition. The first hint comes in the lobby, where they are selling gowns so sparkly and festooned they would make a drag queen blush. I have to rush up to the mezzanine-level ballroom to watch the spray-tanned, glittering dancers. It is breathtaking!

Saturday, March 8

When we leave the hotel this morning at 9:30 A.M., the dancers are either back at it, OR THEY’VE BEEN GOING ALL NIGHT. I like to think the latter.

On our first day off, Wayne and I head to Gettysburg, which is, for my husband, a kind of Mecca. (For me that would be a guided tour of all things relating to the Mitford Sisters or the Patty Hearst kidnapping, but never mind.) We take a bus tour of the battlefield. Interestingly enough, our tour guide is from THE OTHER SIDE—Atlanta—and has a decidedly Gomer Pyle–ish accent, but lordy does he knows his battles! The tour lasts two hours, with many stops at critical locations, describing in detail the troop movements of the three-day bloodbath, which I concentrate hard to picture in my mind: “So it’s like a giant fish hook! General Gregg’s troops are on top of the hill, that’s like the top of the fishhook, looking down as Pickett’s troops swing toward Round Top and the left flank, led by Stuart, accordions in and out, but it’s too little and too late… ” When he gets done with about a fifteen-minute blow-by-blow of this final, fatal choreography, my mind is spinning, and he gently asks, “Now, did y’all get that? Are yuh followin’ me?” I can only nod yes because I do not want him to start over. Back at the visitor’s center, there is a museum that jams even more information into my overloaded brain, particularly about the gruesome cleanup of eight thousand dead guys by Gettysburg’s beleaguered citizenry.

In the gift shop, you can buy just about anything Lincoln-related, from a classy bronze-ish bust to a T-shirt with his picture on it that says THAT IS SO 4 SCORE AND 7 YEARS AGO to a bobblehead Lincoln. Yes, I snark, but here’s a little-known fact about me: any time I hear the Gettysburg Address recited, I burst into tears.

On the way out, we drive around in our own car to check out some of the fifteen hundred or so different monuments on this battlefield, of which three hundred or so are major. The daddy of them all is the one erected by Pennsylvania, which has a truly awe-inspiring scale—a scale that must have inspired things back in York, which I’ll get to soon.

Monday, March 10

Just bopping around this town. I discover of all kinds of enchanting details, like this directory for the Fluhrer Building. I so desperately want to go to the Ladies Parlor!

Just bopping around this town. I discover of all kinds of enchanting details, like this directory for the Fluhrer Building. I so desperately want to go to the Ladies Parlor!

Also in the Fluhrer Building is a model-train store, which is appropriate not only because York has a history of being a big railway hub, but also because the town itself resembles a toy-train town. The store is jammed with everything you could ever want for your toy train town. Don’t you need this bunny on your tracks?

Word on the street is that model-train buff #1, Mr. Neil Young, shops here!

It’s time for York’s St. Patrick’s Day parade. Since Wayne and I lived in New York City for eight years, our St. Paddy’s Day tradition is this: we don’t leave the house. In this case, we work from nine to five at Marketview Arts, but one of the tireless volunteers goes out at lunch and brings back these people who were in the parade!

The Yankee reenactors took in Wayne’s comic Confederate puppets with surprising good grace and even played a little fife-and-drum ditty for us!

Monday, March 17

Our eighteen-year-old daughter, Lulu, arrives in Lancaster on the train from New York. In the beautiful Lancaster train station I see an Amish man and his son waiting for the train. Somehow I know you’re not supposed to take their picture so I don’t, but I notice that the son is wearing contemporary sneakers and they have a regular modern wheeled suitcase, and this is disappointing. Shouldn’t those be some nineteenth-century boots? Shouldn’t that suitcase be wicker?

Wednesday, March 19

After spending one day being her father’s cardboard slave, Lulu, who has been in the highly pressurized art chamber that is Cooper Union School of Art, decides to beat it back to the relative safety of school. Next to the freeway in Hellam, going back to Lancaster, there is a giant shoe, only with windows, which is an old tourist attraction called—what else?—THE SHOE HOUSE. Later I google it, only to find that, tragically, it is only open in the summer months. I decide to draw it without actually visiting it because … because who wouldn’t want to draw a giant shoe? This shoe, I note, is exactly the style of shoe that boys wore to go to the prom in 1973, when I graduated high school—only minus the windows.

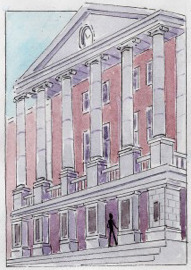

I am introduced to some of the local movers and shakers who are fully invested in protecting and restoring the buildings in this town. When I remark to one of them, Patti Stirk, that a former bank building across the square looks like Scrooge McDuck’s Money Vault she offers to show me two more buildings that prove this town used to have thoroughly outsize ideas of its place in the world.

There are three courthouses. The first is the quaint, tiny, colonial courthouse, which is actually a replica of the original and is strictly a tourist attraction. The current and third courthouse is a giant, ugly, contemporary pile. But the second courthouse, right next door to the Yorktowne Hotel, is where Patti leads me. Currently, it houses administrative offices, but when trials really took place here, you know it was enough to make a perp poop his pants! In 1900, when it was built, the population was thirty-three thousand. For a town with fewer than fifty thousand residents, this place packs a big-city, we-mean-business, badass punch. And it’s kind of hilarious that most of the insides are taken up with a vast corridor that makes you feel like you’re in a Bruce McCall drawing.

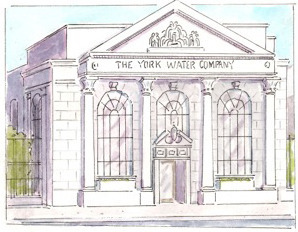

After this, Patti volunteers that her husband is the president and CEO of the York Water Company and do I want to see what that looks like? This is the upside of small towns: everybody knows everyone. (It’s also the downside, I hear.) But hell yes! The York Water Company is a privately owned public utility that has, without interruption, paid dividends to its stockholders since 1814, even throughout that 1863 CONFEDERATE OCCUPATION. Wow! The marble lobby is a vast room the size of my entire house. Its ceiling and walls dazzle with elaborate, Italianate, gilded frescoes. And this is just a place you go to pay your water bill. It’s all about the SCALE. THIS AIN’T NO STRIP MALL! THIS AIN’T NO DMV! THIS AIN’T NO FOOLIN’ AROUND!

After this, Patti volunteers that her husband is the president and CEO of the York Water Company and do I want to see what that looks like? This is the upside of small towns: everybody knows everyone. (It’s also the downside, I hear.) But hell yes! The York Water Company is a privately owned public utility that has, without interruption, paid dividends to its stockholders since 1814, even throughout that 1863 CONFEDERATE OCCUPATION. Wow! The marble lobby is a vast room the size of my entire house. Its ceiling and walls dazzle with elaborate, Italianate, gilded frescoes. And this is just a place you go to pay your water bill. It’s all about the SCALE. THIS AIN’T NO STRIP MALL! THIS AIN’T NO DMV! THIS AIN’T NO FOOLIN’ AROUND!

So, back in York’s golden industrial era, these crazy, out-of-scale mammoth public buildings must have had an enormous effect on its population of worker bees. Think about it: most of the labor force lived in teeny-weeny row houses like these. Imagine their sense of shock and awe when they’d go to the bank or the water company or the courthouse. There are still block upon block of these early- to late-nineteenth-century houses. People still live in them like it’s no big deal. I wonder if they’re still impressed when they go pay their water bill?

So, back in York’s golden industrial era, these crazy, out-of-scale mammoth public buildings must have had an enormous effect on its population of worker bees. Think about it: most of the labor force lived in teeny-weeny row houses like these. Imagine their sense of shock and awe when they’d go to the bank or the water company or the courthouse. There are still block upon block of these early- to late-nineteenth-century houses. People still live in them like it’s no big deal. I wonder if they’re still impressed when they go pay their water bill?

Sunday, March 22

At the Yorktowne Hotel, they’ve hung some pictures of the place when it was in its heyday. I say heyday because, sadly, now is not the hotel’s heyday. Now it’s just us saying, Hey! We might be the only guests! Anyway, remember how I mentioned The Shining? If you think this picture features a large bottle-to-guest ratio, you aren’t taking into consideration that these people are possibly stuck in this picture FOR ETERNITY. Wayne’s incredible installation, called F.O.E., opens on April 4. On April 5, we will be going back to Los Angeles. But you might want to make a trip to the Yorktowne Hotel, check that picture, and make sure we’re not in there.

Follow Mimi on Instagram at mimipondovereasy and on Facebook at Mimi.Pond.Over.Easy.

The Mall Is Dead, Long Live the Mall, and Other News

Photo: Facebook, UrbanExplorationUS, via architecturalafterlife.com

Yesterday was Zelda and F. Scott Fitzgerald’s wedding anniversary. Here’s a passionate, discursive letter she wrote him in the summer of 1930, after her breakdown. “The sheets were always damp. There was Christmas in the echoes, and eternal walks. We cried when we saw the Pope. There were the luminous shadows of the Pinco and the officer’s shining boots.”

A photographer’s thoughts on capturing the essence of Jane Goodall.

Today in philosophers on video: “A Shirtless Slavoj Žižek Explains the Purpose of Philosophy from the Comfort of His Bed.” “It just asks, when we use certain notions, when we do certain acts, and so on, what is the implicit horizon of understanding? It doesn’t ask these stupid ideal questions: ‘Is there truth?’”

And today in ruin porn: America’s abandoned malls.

Nowhere has launched a travel-writing contest—they’re looking for “old, novice, and veteran voices with a powerful sense of place in their writing.” The prize is a cool grand.

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers