The Paris Review's Blog, page 717

April 11, 2014

Show, Don’t Tell

Pio Ricci, Das bewunderte Geschenk (The Admired Gift), 1919, oil on canvas.

Recently someone gave me a book. It was a book, she said, that she knew I would love. She had read it and thought of me at once. It was a supremely kind gift. My heart sank.

There are few things more oppressive than the things you are supposed to love—books, movies, records, people—things that somehow match the shorthand you show the world and mirror back just how crudely you have caricatured yourself. When someone says I will like something, I tend to assume the something in question will be precious, tedious, and often aggressively eccentric. Sometimes I do like these things, which is the worst outcome of all.

In the case of this particular book, I already knew. This is an author whom people have assumed I have loved since I learned to read. Her novels, generally set on the Upper West Side or in Greenwich Village, are populated with the youngish, Jewish bourgeoisie of the Cuisinart generation: good educations, artistic leanings, and improbable names. Sometimes they have affairs with one another; often they are surrounded by antique china. This author has a cult following.

Back when I was young and idiotic, I, like many kids, defined myself as much by my aggressive dislikes as by my preferences. It seemed important to announce not merely that I loved the Replacements, but that I also hated the Who (whom I didn’t even hate). Dismissal was so easy, so satisfying, especially compared to defending what you love. When you are in the grip of the uncertainty and self-doubt of defining who you are, attack can be an easy escape—and hard to abandon.

We grow up. It gives me no pleasure nowadays to tear down anther person’s enthusiasm, still less something someone else believes I will love. How can anyone know the depths of another person? After all, if we put an itemized list of quirks and signifiers into the world—and, in the age of social media, this is often literal—like a lazy writer, can we blame anyone for reading us with as little care?

Then, too, maybe it is wrong to despise something—like a book that you’re supposed to love—for being only a part of who we are. We are all vast; we all contain multitudes, and some of them are tacky. No one is the list of quotes and likes on his Facebook page or the flippant description on his Twitter profile. But that can be part of it, too. Andre Maurois wrote that “in literature as in love, we are astonished at what is chosen by others.”

The Big Book

On photographer W. Eugene Smith’s unseen opus.

A spread from the facsimile edition of W. Eugene Smith’s The Big Book.

On September 2, 1958, W. Eugene Smith’s passport was stamped at the airport in Geneva, Switzerland. Hired by General Dynamics, he was there to photograph the United Nations Conference on Peaceful Uses of Atomic Energy, known as “Atoms for Peace.” He was to be paid $2,500 for two weeks of work (about $20,000 in 2014 money), plus a $20 per diem. Commercial work wasn’t Smith’s preference, but he needed the money. He needed some distance from New York, too.

A week later, on September 9, Smith’s long-awaited extended essay on the city of Pittsburgh hit newsstands in Popular Photography’s Photography Annual 1959. It was the culmination of a three-and-a-half-year odyssey that began with a three-week assignment and led to 22,000 exposed negatives, two thousand of which he said were “valid” for his essay. He staked his reputation on the work, evoking Joyce, Faulkner, Tennessee Williams, and Beethoven, among others, as influences for the “layers” intended in his Pittsburgh layouts. Two consecutive Guggenheim fellowships (the first one coinciding with his friend Robert Frank’s fellowship for the work that became The Americans) further raised expectations. After turning down $20,000 from both Life and Look magazines when they would not agree to his demands for editorial control, Popular Photography offered to put thirty-six pages of their Annual 1959 at his disposal for $3,500. Smith accepted.

Now the anticipated magnum opus was set to arrive. But rather than stick around to toast his achievement, Smith jetted to Geneva. He had anticipated a Pittsburgh flameout earlier that summer, in a letter to his uncle, Jesse Caplinger: “The seemingly eternal, certainly infernal Pittsburgh project—the sagging, losing effort to make the first of its publication forms so right in measure to the standards I had set for it … it is a failure.” Later, he wrote his friend Ansel Adams to “apologize” for “the debacle of Pittsburgh as printed.”

Smith wasn’t the only one who disapproved. Less than a week after the Annual appeared, the influential photographer and editor Minor White wrote a letter to John Morris, the executive editor of Magnum, Smith’s agency at the time, to complain about the waste of prime space given to the Pittsburgh spread. “Gene doesn’t have proper training in layout,” White wrote. Jacob Deschin, writing in the New York Times, was more charitable, calling the Pittsburgh essay a “personal triumph” for Smith and an “intensely personalized, deeply felt document.” He wrote, “Mr. Smith uses layout as an additional means of communicating his impressions of the city’s varied facets, its human and physical qualities … The approach is poetic, evoking the city’s character, the atmosphere of its everyday life, recalling the past and pointing up some of the bright signs of the future.”

But Deschin also cited the spread’s challenges: “Some readers may object to the details of the layout, such as the use of small pictures, rather than fewer and larger.” Smith had crammed eighty-eight images into thirty-six pages, along with a not insignificant amount of text. Additionally, the trim size of the Photography Annual was 8.5" x 11", compared to 11" x 14" at Life, where Smith had spent the last twelve years. His desire for meditative visual sequences had outstripped the available format.

In Pittsburgh, Smith had met a young avant-garde filmmaker named Stan Brakhage, who had been hired to make a film commemorating the city’s bicentennial. The two hit it off instantly. Each admired the other’s dedication and belief in the power of seeing, which, they both thought, was so often tainted by commercial pressures, popular culture, and human fears. Brakhage used Smith’s stills in his cut of the film (a cut never released and unavailable today; another director finished the film), and his cinematic philosophies spurred new ideas for Smith’s Pittsburgh layouts.

In Geneva, Smith shared a chalet with Brakhage, who was also there to document “Atoms for Peace.” They attended the conference by day and shared Scotch and conversation in the chalet by night. The thirty-nine-year-old Smith craved the fertile, boundless, uncompromising engagement offered by twenty-five-year-old Brakhage, who, in 1958, had completed the film Anticipation of the Night, which he’d considered ending with the scene of his own suicide, a thought that would have thrilled Smith.

It’s at this point that the biographical enterprise falls short; the true impact of the relationship between Smith and Brakhage can only be speculated. In June of 2003, I was at a café in Santa Monica with Carole Thomas, Smith’s girlfriend with whom he shared his Sixth Avenue loft from 1959 to 1968. She told me that “Gene was obsessed with this avant-garde filmmaker who used to come over to the loft,” but she couldn’t remember his name.

A few years later, my colleague Dan Partridge found a few minutes of recorded sound, among Smith’s 4,500 hours of loft tapes, in which Smith can be heard reading from a 1963 writing by Brakhage: “How many colors are there in a field of grass to the crawling baby unaware of ‘Green’?” I called Carole Thomas. She confirmed that the filmmaker had been Brakhage. A quick Google searched revealed that he had passed away earlier that year. Damn it. I reached out to Brakhage’s first wife, Jane Wodening, and to his widow, Marilyn Brakhage, both of whom confirmed the friendship between Smith and Brakhage but could not recall much else. Years passed. I moved on to other areas of research. Then last year, a copy of a May 1970 letter from Brakhage to Smith was found in the Brakhage archive in Boulder, Colorado, and the original was found in the Smith archive in Tucson, Arizona. The letter, signed only “Stan” and mostly a rave about Smith’s 1969 Aperture monograph, included this line:

Wonderful how clearly your face comes to me the instant I type your name -- your face … its particular intensity: and then I have a shift of backgrounds including the kitchen in that damn Swiss chalet, the nightmarish Atoms For Peace circus, and then most happily your loft in N. Y. -- your face remaining a constant thru all this, weathering these scenes with an etch of grace: see, I’ve almost got a motion picture portrait out of these memories.

In connecting dots between Smith and Brakhage, that’s all that I’ve found. But I believe that much about Smith’s next large-scale project can be gleaned from this small amount of information.

Smith returned from Switzerland embarrassed by Pittsburgh but emboldened to go even further with his ideas for sequencing still images. He embarked on a two-volume, 350-page retrospective book that eventually contained 450 photographs spanning his career to that point. It became known, properly, as “the Big Book.” It could also have been called “the unpublishable book,” the dummy, or maquette, of which was accessible only in Smith’s archive until an extraordinary facsimile of it was published last year by the University of Texas Press and the Center for Creative Photography at the University of Arizona.

Brakhage felt that words deadened the senses; the majority of his films are silent. Smith had strangled his Pittsburgh layout with overwrought text (“Steeple and microscope – how will they flourish in common?”); The Big Book contains no text. It opens with tender pictures of children, including Smith’s own, and closes with brutal images of carnage on the front lines of World War II, an arc Brakhage would have admired. In between there are some two dozen of his iconic images from Life magazine, and many more that are rarely, if ever, published in Smith monographs, including some of the most abstract and ephemeral work of his career, all woven together with no concern for chronology, subject, or theme. Images from the photo essays “Country Doctor” and “Nurse Midwife,” for example, aren’t confined to discrete sections. Journalism was thrown out the window. There was also no concern for making commodities of individual photographs, a growing trend in the art world at that time. What matters most in The Big Book are shapes and rhythms, patterns of tones, and an underlying sense of the foibles of human culture—the hungry, blind march toward death, often at the political and economic hands of fellow humans. These are all ideas Smith and Brakhage would have discussed over Scotch during those long nights in the Swiss chalet. The Big Book represents Smith’s most fully formed ideas for layout. Unrestrained by the strictures of print journalism, rejuvenated by Brakhage, Smith produced what would be the pinnacle of his sequential aesthetic.

The achievement owes much to Carole Thomas, who wandered into Smith’s life as a soft-spoken, eager, and brilliant art student in 1959 and stayed for nine years. Only eighteen years old, she already had a background in theater design, which made her the perfect partner for Smith, who often claimed theater was his most important influence, not photography. Thomas absorbed everything Smith’s overflowing passions could bear and she helped make decisions he couldn’t on his own. She also became a masterful darkroom printer in her own right. If Thomas had a flaw, it was being too young to realize that nobody would publish a book with 450 photographs over 350 pages. Still, she designed the most audacious product of Smith’s career. It would be her unseen opus, too.

A half century after Smith and Thomas finished their two-volume maquette, the Center for Creative Photography and University of Texas Press made a bold, complicated decision to publish a facsimile of the surviving original, rather than redesigning a new book based on it, by inserting pristine reproductions of Smith’s images in place of the maquette’s Agfa Copyrapid reproductions (essentially fifty-year-old photocopies of Smith’s original prints) that weren’t meant for publication. A third volume includes thumbnails of all 450 images made from Smith’s original prints, or negatives when his prints weren’t available, proving that they could have done what they chose not to do. You can hear cynics decrying, I want to see Smith’s vaunted printing technique represented here, not glorified photocopies, and certainly not for $185! But the right decision was made. This version gives life to an archival object, offering an opportunity to get as close to the work of Smith and Thomas as possible (short of holding the original maquette in our hands). Despite his facility, Smith was never about the precious print anyway. It was another of his contradictions. He was more about effort than outcomes.

Sam Stephenson is a writer working on a biography of W. Eugene Smith for Farrar, Straus and Giroux. He is also a partner in the documentary company Rock Fish Stew Institute of Literature and Materials, based in Durham, North Carolina.

Excerpt from The Big Book by W. Eugene Smith (Copyright © The Arizona Board of Regents, University of Arizona, Center for Creative Photography; photographs © 2013 The Heirs of W. Eugene Smith) used by permission of the University of Texas Press.

Relive the Revel

Frederick Seidel

Ben Lerner, Emma Cline

Ben Lerner, John Jeremiah Sullivan

Francine du Plessix Gray, Robert Pounder

Frederick Seidel

Gary Shteyngart, Brandon del Pozo

Gay Talese

Jeffrey Eugenides, Larissa MacFarquhar

John Jeremiah Sullivan

Jon-Jon Goulian

Jonathan Galassi

Jonathan Galassi

Kay Eldredge, James Salter, Jean McCulloch, Rex Weiner

Kedakai Turner, James Lipton

Lorin Stein

Roz Chast, Ben Lerner, Emma Cline, Lydia Davis

Roz Chast

Stephanie LaCava

Terry McDonell

Uma Thurman

Zadie Smith, Frederick Seidel

We’re still recovering from Tuesday’s Revel, where some five hundred people gathered to honor Frederick Seidel with the Hadada Award, presented by John Jeremiah Sullivan. Lydia Davis presented Emma Cline with the Plimpton Prize for Fiction; Roz Chast presented the Terry Southern Prize for Humor to Ben Lerner; and Martin Amis, Zadie Smith, and Uma Thurman all read from Seidel’s work. We could say a good time was had by all, but why not let the pictures tell the tale? It was a spectacular evening. You can read accounts of the fun from Page Six, Women’s Wear Daily, and Guest of a Guest. Be sure to take a look at all the photos here, too. See you next year!

Photos by Clint Spaulding / © Patrick McMullan / PatrickMcMullan.com

Kansas in Drag, and Other News

A photograph from Kansas City recently discovered by Robert Heishman.

Today is Rizzoli Bookstore’s last day in business on Fifty-Seventh Street. Visit their beautiful shop before it’s gone.

An unnerving correlation between philosophy and murder: “Countries with high homicide rates also have citizens who believe strongly in free will.”

Britain got rich on sheep. “Wool was the white gold of our economy in the Middle Ages: when Richard the Lionheart was ransomed by the Holy Roman Emperor, Henry VI, the Cistercian monasteries of Britain were asked for a year’s haul of fleece to pay for him.”

“Amazon has purchased Comixology, the largest retailer of digital comics.” Is your local brick-and-mortar comic-book store completely fucked?

Nobody wants to go to Colonial Williamsburg anymore. “Here’s an idea: market Colonial Williamsburg as so stodgy and weirdly Americana it’s cool, like taxidermy or trucker hats.”

In an old shoebox, an artist has discovered a series of strangely affecting photos from the Kansas City drag scene of the sixties.

April 10, 2014

In Extremis

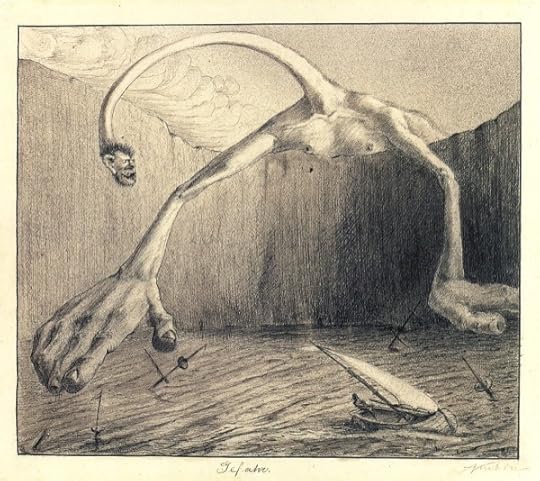

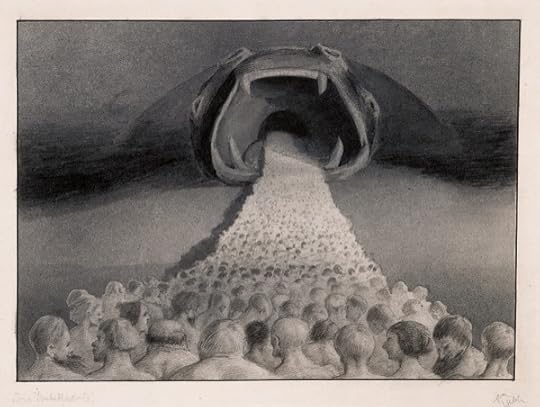

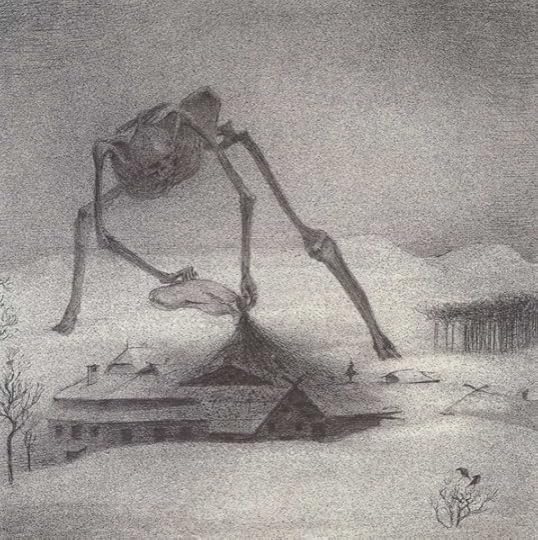

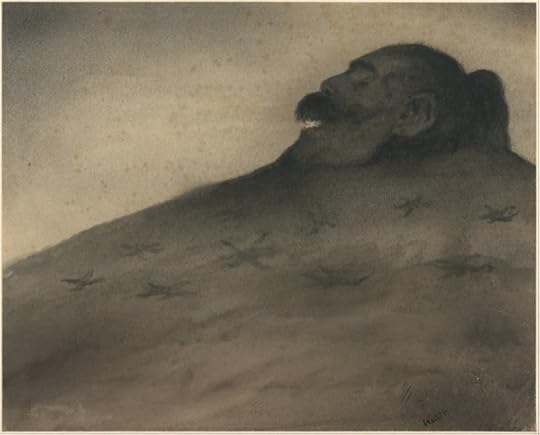

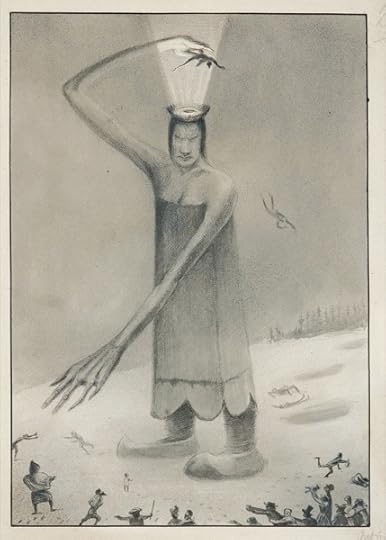

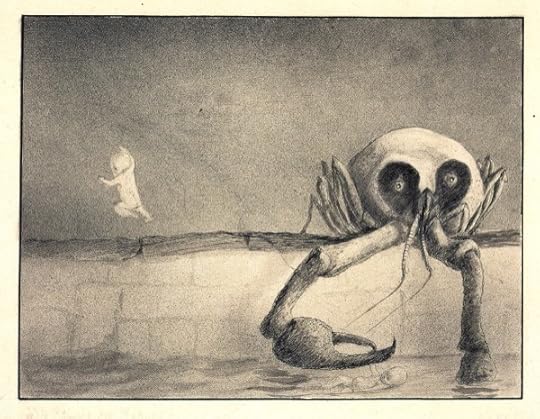

Self-Reflection, c. 1901-2

Danger, 1901

Into the Unknown, c. 1901-2

Epidemic, 1901

Dolmen, c. 1900-1

Black Mass, 1905

Siberian Fairy Tale, c. 1901-2

The Moment of Birth, c. 1901-2

Alfred Kubin was an Austrian artist and, to hazard a guess, a fairly tortured soul. Today is his birthday, and as a peg it’ll have to suffice, though I don’t imagine he was the type to put on a party hat. He was known to live in a small castle in Zwickledt, and his biography includes a nervous breakdown and a suicide attempt—the latter on his mother’s grave. His early drawings, shown here, often feature monsters, deformities, disfigurements, human bodies in decay—a grim phantasmagoria of the bleak, the macabre, and the merely unsettling, with a palette that tends toward soot. What keeps me looking at it is some element of detachment in his style, as if a savage disembowelment by a fantastical creature were no big thing; we’re not accustomed to seeing the brutal without the lurid. As Christopher Brockhaus notes, “these drawings revealed Kubin’s abiding interest in the macabre. Thematically they were related to Symbolism, as shown by the ink drawing The Spider (c. 1900–01; Vienna, Albertina), which depicts a grotesque woman-spider at the center of a web in which copulating couples are ensnared. This reflects the common Symbolist notion of the woman as temptress and destroyer.” Not surprisingly, Kubin admired Schopenhauer.

The artist was a novelist, too, and one book in particular, The Other Side, continues to haunt readers today. In an excellent appraisal of Kubin, Jeff VanderMeer offers a chilling synopsis of the novel, which he describes as Apocalypse Now by way of Hieronymus Bosch:

The Other Side tells the tale of a Munich draftsman asked by an old schoolmate named Patera to visit the newly established Dream Kingdom, somewhere in Central Asia. Patera rules the Dream Kingdom from the capital city of Pearl. The wealthy Patera has literally had a European city uprooted and brought to its new location, along with sixty-five thousand inhabitants. The narrator, after some hesitation, agrees to visit and travels with his wife through Constantinople through Batum, Batu, Krasnovodsk, and Samarkand—Samarkand being the last of any identifying landmarks on their journey.

The narrator soon finds that the Dream Kingdom is, well, a kingdom of dreams. People experience or live “only in moods” and shape all outer being at will “through the maximum possible cooperative effort.” A huge wall keeps out the world and “the sun never shone, never were the moon or the stars visible at night … Here, illusions simply were reality.”

Over time, strange rituals and aberrations have sprung up. Pearl also shifts in odd ways, and in this sense has a kinship with M. John Harrison’s far-future Viriconium, which also function from more of a metaphorical than a chronological foundation. This doesn’t bother the narrator at first, but as the city’s changes become more and more grotesque, it’s clear that the Dream Kingdom is faltering, descending into madness.

Philip Larkin’s “The Trees”

Photo: 4028mdk09, via Wikimedia Commons

It is spring now, and very hard not to feel in clichés. Especially with daffodils everywhere—and very cheap they are, too. “Telephone flowers,” a friend of mine calls them. I buy them by the armful; don’t you?

When I was thirteen, I wrote my first and last piece of fiction. It was about an old woman in a nursing home suffering from dementia and planning her garden through the winter. It was called “Living Time.” Even by thirteen-year-old standards, it was mawkish and I knew it. Because—the silliness of that act of ventriloquism aside—what new is there to say about spring?

Being hard on one’s own young self is not very fair, and it is also an act of cheap egotism; one would never indulge the same lack of generosity toward other children trying to express things, things that feel real and new to them. If these things have passed into cliché, it only means they have been true many times, and that is no sin.

Philip Larkin said, “Deprivation is for me what daffodils were for Wordsworth.” But then he wrote this.

The trees are coming into leaf

Like something almost being said;

The recent buds relax and spread,

Their greenness is a kind of grief.

Is it that they are born again

And we grow old?

No, they die too,

Their yearly trick of looking new

Is written down in rings of grain.

Yet still the unresting castles thresh

In fullgrown thickness every May.

Last year is dead, they seem to say,

Begin afresh, afresh, afresh.

New Candor

Rebecca Mead, Jill Lepore, and a new direction for biography.

A portrait of George Eliot by Frederick William Burton, 1864.

Feminism, Paula Backscheider explains in Reflections on Biography, transformed the study of history. “The arresting power of women’s deepest feelings, their comments about their own bodies, and the stark force of their drive to work” are part of the new candor, she says. And there are new things to consider: “How do you do justice to boundary-breaking acts, such as learning to read, or, as with [George] Eliot, not marrying?”

It was thanks to feminism that the relationship between biographer and subject took on a new life—for women to tell other women’s stories, they had to find ways to reconstruct those women’s lives. Ordinary women and their domestic lives became respectable subjects. Their diaries, letters, photographs, and other records could be taken seriously as evidence. Minor details, even in non-events, nuance the undertaking.

Reading Rebecca Mead’s intimate and scholarly My Life in Middlemarch, her memoir about George Eliot’s masterpiece, got me thinking about this shift in biography. What is it that compels one woman to explore the work and personality of another, often with centuries between us—and what are we trying to say?

Mead grew up in southwestern England, in a provincial town not unlike Eliot’s Coventry or the town of Middlemarch itself. And like Middlemarch’s heroine Dorothea Brooke, she too longed to escape the “provincialism of the soul.” For Mead, Middlemarch became representative of growing into one’s intelligence and, through it, outward into the larger world of ideas.

My Life eloquently tracks between Mead’s experiences and Eliot’s. This kind of approach is on the upswing. It has become acceptable to use your experiences as a lens through which to understand another writer. What emerges most powerfully in My Life is not Middlemarch, but Mead herself—it’s her sympathetic gaze, her connection to Eliot and her masterpiece, that hooks us. Joyce Carol Oates called Mead’s book a bibliomemoir (“a subspecies of literature combining criticism and biography with the intimate, confessional tone of autobiography”) in the vein of Nicholson Baker’s U and I, Geoff Dyer’s Out of Sheer Rage, and Phyllis Rose’s My Year of Reading Proust. However you slant it genre-wise, My Life is scented with the same close readings, scholarly elbow grease, forensic evidence collection, and leap-of-faith search for character and motivations that characterizes all serious—if formally now fluid—literary biographies.

My Life follows on the heels of Jill Lepore’s Book of Ages: The Life and Opinions of Jane Franklin, which reconstructs the stunted but brilliant sensibility of Ben Franklin’s sister through a miscellany of sources. Unlike the wildly prolific, well-archived, and canonized Eliot, Jane only produced a sixteen-page Book of Ages that she fashioned herself, and which recorded the births and deaths of her children. Scant letters remain. “It explains what it means to write history not from what survives but from what is lost,” Lepore says, emphasizing that she was writing not only a biography but “a meditation on silence in the archives.” Jane’s accomplishments, compared to Ben’s, were few: “He signed the Declaration of Independence, the Treaty of Paris, and the Constitution. She strained to form the letters of her name.”

What’s emerging in biographies of women, as both Mead and Lepore demonstrate, is another way of looking at the facts. In her 1985 essay, “Fact and Fiction in Biography,” the critic and biographer Phyllis Rose points out that as novels increasingly embrace fact, biographies increasingly try to embrace fiction. Facts, or the lack of them, can tilt you in different directions. Eliot has been amply written about, and Jane Franklin not at all. Mead telescopes the multitude of facts available on Eliot in ways that bring clarity to Eliot’s domestic life and her attitudes—all of which, Mead shows, illuminate the intentions of Middlemarch’s characters.

Lepore does the opposite: leaning on public records, Ben’s writings, newspapers, and Jane’s surviving letters, she recreates the world Jane Franklin lived in and then puzzles together the shards of information to fill in the facts. She guesses at what Jane read through her allusions to events in the papers, to sermons, and to political events leading up to the American Revolution. Lepore also makes it clear that her technique “borrows from the conventions of fiction.” She dwells on Jane’s girlhood silence instead of treating it as an obstacle. And she takes a magnifying glass to Jane’s letters, seeing a jab in the closing salutation to Ben’s wife: “your Ladyships affectionat Sister & most obedient Humble Servant.” (Jane usually signed off with “Your loving Sister.” “Must she curtsey?” Lepore asks.) We get a sense of Jane’s capacious and frustrated intellect in her recipe for crown soap. It is four pages long. “There is a good deal of Phylosephy in the working of crown soap,” Jane tells Ben, who requested it for his autobiography. Their father was a soap boiler, and this was the secret recipe.

* * *

It takes a certain combination of diligence and restraint for a woman to write about another woman. Perhaps she fills your imagination, and perhaps you lose your impartiality. But so what. What makes Lytton Strachey’s Eminent Victorians a delightful example of the biographer’s art, Rose observes, is its “ulterior intentions, its deliciously wicked absence of impartiality.”

Lepore and Mead, both dogged researchers, stick to the facts, but it’s the way they stick to them that betrays their biases. Both sort through nuances in their subjects’ correspondences in an effort to correct or expose. Mead is eager to correct a literary misreading or shortsighted approach to the work, and Lepore exposes the intellectual slights and social injustices that Jane endured. Their sensibilities undergird the narratives.

Such devotion is common with women, Backscheider observes: “Women often bring an overt intensity to the writing of lives about women that seems rather rare in male biographers.” Because women need to be discovered, they depend on other women to tell their stories. The two are in it together. And because the relationship is more equal, there’s reciprocity to it. These days, the biographer is a meaningful participant in the telling of a life, a trend that has shifted dramatically in the past century. The Bloomsbury men’s group believed the writer’s voice should predominate, until the New Critics demanded an “objective history presented in neutral tones,” at which point the biographer went invisible. Feminism brought the biographer back, Backsheider says.

Mead at first appears very much a subject of her own, though the more you read, the more you realize that she herself is a trope. Like Eliot, Mead longed to escape a provincial coastal town in England and build an intelligent, book-centric life. Mead’s frankness about these longings makes you wonder: If she’d married young, rather than in her mid-thirties, would she understand Eliot’s concerns about being a single woman in her thirties in quite the same way? If Mead hadn’t been compelled to sort out her feelings about caring for another man’s children, just as Eliot had, perhaps she’d have given short shrift to Eliot’s maternal feelings, and the ways in which they played out in her life and work. Mead transforms Eliot from a canonical writer to a woman with an urgency of feelings, a whip-sharp intelligence, psychological acuity, and self-possession that deepened over time and through her relationships. As is the fashion with many women’s biographies, Mead takes Eliot out of the grand dame spotlight and shapes her into a social being.

In the epistolary relationship between Ben and Jane Franklin, Lepore’s feelings about the inequities between the siblings come bitingly across. “A correspondence really is a kind of account, and not without its price,” Lepore says tellingly. Back in the eighteenth century, the recipient paid the postage. That is, unless you were Ben Franklin, deputy postmaster general of America. Because Jane was poor, and had to cover the cost of Ben’s letters, he warns her not to write. She asks to have their letters franked (prepaid), but he refuses and offers to reimburse her. It’s all a little thoughtless—you feel outrage at the slight. “He received her letters, but the letters themselves are lost,” Lepore says witheringly, an undercurrent of emotion beneath the facts. In a letter, he lists the six letters she sent him that year, all unceremoniously discarded. His four letters to Jane, of course, survive.

Mead, meanwhile, is adept in her treatment of Eliot’s famously bad looks. Mead is protective of Eliot; she spends a lot of time reflecting on other people’s perceptions of her. “She is magnificently ugly,” said Henry James, who famously called Eliot a horse-faced bluestocking. Mead finds a more beautiful aspect: She wore black velvet (gauche for unmarried women), she held her own among first-rank politicians and authors. And Mead scrutinizes what Backscheider describes as “women’s” evidence: an oil painting, a watercolor, a photograph, a pen-and-ink drawing. No doubt these are not flattering images, but Mead drily remarks that one chalk drawing of Eliot exposes her as, well, middle-aged. She ponders that for a bit, along with the fate of all women who in their forties begin to lose their ironed looks. Then, in a masterful move, she angles back to Middlemarch’s Lydgate, the doctor for whom, like Eliot’s would-be lover Herbert Spencer, beauty was sine qua non. Lydgate, of course, chooses the wrong woman, a shallow blonde rather than the woman with ideas. With this subtle reckoning, Mead feeds us an ironic twist and a new way of seeing. After all, Henry James and others fell in love with Eliot within minutes of hearing her speak, Mead counters. She feels defensive on Eliot’s behalf, and hints at what might be construed as Eliot’s self-defense: “I feel that way especially about representations of women,” Ladislaw says to a friend, about the deficiencies in paintings, in Middlemarch, “As if a woman were a more colored superficies! You must wait for movement and tone.”

If women are tireless investigators of one another’s lives and motivations, they’re twice so when looking at other women’s romantic dealings. “Edward Mecom was either a bad man or a mad man,” Lepore decides. “Every one of Jane’s children who had children named a child after her. Not one of them named a child after their father.” Lepore is an astute observer of silence. The fact that Jane never mentioned her husband until he died, while certainly able to express plenty of emotion about her children and about the books she read, suggests the marriage was a wash. “Marrying the man she did, when she did, determined the whole course of Jane Franklin’s life. Marriage determined the whole course of every woman’s life,” Lepore says.

“Since marriage is so often the context within which a woman works out her destiny, it has always been an object of feminist scrutiny,” Phyllis Rose explains in her prologue to Parallel Lives: Five Victorian Marriages. And while marriage is a perfectly good hinge around which to elucidate a life, writing about domestic life is fraught. “To write about women it was necessary to write about compromise and failure and to acknowledge that tragedy can be enacted in a bourgeois setting,” Rose says, nodding to George Eliot’s portrait of Dorothea Brooke.

Mead is attentive to all the varieties, shades, and failings of love in Middlemarch. “We each have our own center of gravity, but must come to discover that others weigh the world differently than we do,” she writes, recognizing that the marriage between Casaubon and Dorothea is at the heart of what Middlemarch teaches us about sympathy. “Throughout Middlemarch, Eliot has shown from different angles the demands that marriage makes,” Mead says as she considers the trials of young love, the “unbridgeable distance” between Dorothea and Casaubon, and the “romance of enduring love.” Mead also battles critics who find Ladislaw undeveloped, and suggests that his role might be “to show us what it is like to be fallen in love with—the delight of discovering oneself to be the object of love.” If this is what Eliot needed him for, perhaps that’s enough.

But the most sincere love story, Mead impresses on us, is the uncommon arrangement between Lewes and Eliot. Their liaison deserves the attention, and the admiration, that Mead pays to it, given the notoriety Eliot received for flouting social convention and for not marrying. It proved she had mettle. Eliot benefited from a power dynamic that fed her creativity: Lewes encouraged her to try writing a novel and provided her with a supportive working environment. He left Eliot alone to write a death scene one evening, after which she writes, “We both cried over it, and then he came up to me and kissed me, saying ‘I think your pathos is better than your fun.’”

Just as it is clear that without Edward Mecom, Jane Franklin might have amounted to something, it’s equally clear that without George Lewes, George Eliot might never have tried her hand at fiction. What does it mean to spend years with someone? Perhaps you want to get wrapped up in someone. Could this be what women are after, when writing about other women? Certainly you have a job to do, but perhaps you also have a commitment of caring. Giving women their due in history creates a kind of historical empathy, with the expectation that someone else might give us the same time and attention one day.

“We want people to feel with us, more than to act for us,” Eliot wrote to a friend, says Mead. Eliot took her readers seriously, and Mead suggests that we take ourselves seriously, too. “I have grown up with George Eliot,” she explains. “I think Middlemarch has disciplined my character. I know it has become part of my own experience and my own endurance.” Our subjects give us something, too.

On June 2 at Housing Works Bookstore, Diane Mehta will launch a VIDA roundtable on literary biography with Jill Lepore, Rebecca Mead, Ruth Franklin, and Salamishah Tillet. Follow her @DianeMehta.

Meeting Coleridge

Hazlitt’s self-portrait, 1802

William Hazlitt, born in England on April 10, 1778, had a diverse and storied career in the arts: he was an essayist, a philosopher, an art critic, a literary critic, a drama critic, a cultural critic, and—just to even things out—a painter. Despite their age, his essays remain surprisingly readable. They are, in their sense of purpose and their tweedy vastness, distinctly nineteenth-century English; Hazlitt’s subjects are so broad, so plainly monumental, that any undergraduate who dared to write on them today would be flunked immediately. (His essay “On Great and Little Things” begins, “The great and the little have, no doubt, a real existence in the nature of things.”)

Hazlitt also chose his acquaintances wisely, at least insofar as many of them wound up ascending into the canon: Wordsworth, Stendhal, Charles and Mary Lamb. His landlord was Jeremy Bentham. But then there was Coleridge, ah, Coleridge! In his 1823 essay “My First Acquaintance with Poets,” Hazlitt rhapsodizes about his first encounter with the poet, who would become a kind of distant mentor, though later there came the requisite falling-out. It’s a gushing account, endearingly thorough and fanboy-ish, full of deft turns of phrase—and it humanizes both men, reminding us that these two Dead White Guys were once … Living White Guys, with fears and ambitions and impressive heads of hair.

I was at that time dumb, inarticulate, helpless, like a worm by the way-side, crushed, bleeding, lifeless … that my understanding also did not remain dumb and brutish, or at length found a language to express itself, I owe to Coleridge … I could not have been more delighted if I had heard the music of the spheres.

I was called down into the room where he was, and went half-hoping, half-afraid. He received me very graciously, and I listened for a long time without uttering a word. I did not suffer in his opinion by my silence. “For those two hours,” he afterwards was pleased to say, “he was conversing with William Hazlitt’s forehead!” His appearance was different from what I had anticipated from seeing him before. At a distance, and in the dim light of the chapel, there was to me a strange wildness in his aspect, a dusky obscurity, and I thought him pitted with the smallpox. His complexion was at that time clear, and even bright … His forehead was broad and high, light as if built of ivory, with large projecting eyebrows, and his eyes rolling beneath them, like a sea with darkened lustre. “A certain tender bloom his face o’erspread,” a purple tinge as we see it in the pale, thoughtful complexions of the Spanish portrait-painters, Murillo and Velasquez. His mouth was gross, voluptuous, open, eloquent; his chin good-humoured and round; but his nose, the rudder of the face, the index of the will, was small, feeble, nothing-like what he has done … His hair (now, alas! grey) was then black and glossy as the raven’s, and fell in smooth masses over his forehead. This long pendulous hair is peculiar to enthusiasts, to those whose minds tend heavenward; and is traditionally inseparable though of a different colour) from the pictures of Christ. It ought to belong, as a character, to all who preach Christ crucified, and Coleridge was at that time one of those!

I ventured to say that I had always entertained a great opinion of Burke, and that (as far as I could find) the speaking of him with contempt might be made the test of a vulgar democratical mind. This was the first observation I ever made to Coleridge, and he said it was a very just and striking one. I remember the leg of Welsh mutton and the turnips on the table that day had the finest flavour imaginable …

The next morning Mr. Coleridge was to return to Shrewsbury … Asking for a pen and ink, and going to a table to write something on a bit of card, [he] advanced towards me with undulating step, and giving me the precious document, said that that was his address, Mr. Coleridge, Nether Stowey Somersetshire, and that he should be glad to see me there in a few weeks’ time, and, if I chose, would come half-way to meet me. I was not less surprised than the shepherd-boy (this simile is to be found in Cassandra), when he sees a thunderbolt fall close at his feet. I stammered out my acknowledgments and acceptance of this offer (I thought Mr. Wedgwood’s annuity a trifle to it) as well as I could; and this mighty business being settled, the poet preacher took leave, and I accompanied him six miles on the road. It was a fine morning in the middle of winter, and he talked the whole way.

Cryptozoology in Texas, and Other News

Photo: joanna8555, via flickr

Gabriel García Márquez was in the hospital last week, but now he’s out and on the mend, albeit in “delicate” condition. We wish him a speedy recovery.

Poor Comic Sans, the common man’s font, the bane of designers and typographers everywhere, has gotten a facelift: say hello to Comic Neue.

A news station in Texas has, with its “reporting,” stoked the flames of the legend of the chupacabra. “Jackie and Bubba believed they’d stumbled upon a Latin American vampire beast that guzzles the blood of livestock. They decided to take it as a pet.”

Are English departments in jeopardy? Some professors think so. “Literary studies is being ‘devalued and dismissed’ as a result of English departments’ being ‘reconceived as being primarily in the business of teaching expository writing.’ Furthermore, he wrote, there’s an insidious rush ‘to make literary studies an outpost of “digital scholarship.”’”

A new photo exhibit by John Goodman (no, not that John Goodman): “Together at last. Boxers and ballerinas. Those two great seemingly Yin-Yang forces of the physical—the soft, fluid Terpsichore and the aggressive Herakles …”

April 9, 2014

Already! (Or, Baudelaire at Sea)

Alfred Jensen, Tall Ship, late nineteenth century

Baudelaire was born on this day in 1821. You may know that he’s credited with coining the term modernité, or that he helped to shape our theory of the flâneur; but you likely did not know that he was a seafaring man, with an unslakable thirst for the ocean. (An irresistibly bad pun presents itself: Boatelaire. But let’s pretend I didn’t write that.) Here’s “Already!”, a prose poem translated from the French by Aleister Crowley.

ALREADY!A hundred times already the sun had leaped, radiant or saddened, from the immense cup of the sea whose rim could scarcely be seen; a hundred times it had again sunk, glittering or morose, into its mighty bath of twilight. For many days we had contemplated the other side of the firmament, and deciphered the celestial alphabet of the antipodes. And each of the passengers sighed and complained. One had said that the approach of land only exasperated their sufferings. “When, then,” they said, “shall we cease to sleep a sleep broken by the surge, troubled by a wind that snores louder than we? When shall we be able to eat at an unmoving table?”

There were those who thought of their own firesides, who regretted their sullen, faithless wives, and their noisy progeny. All so doted upon the image of the absent land, that I believe they would have eaten grass with as much enthusiasm as the beasts.

At length a coast was signalled, and on approaching we saw a magnificent and dazzling land. It seemed as though the music of life flowed therefrom in a vague murmur; and the banks, rich with all kinds of growths, breathed, for leagues around, a delicious odour of flowers and fruits.

Each one therefore was joyful; his evil humour left him. Quarrels were forgotten, reciprocal wrongs forgiven, the thought of duels was blotted out of the memory, and rancour fled away like smoke.

I alone was sad, inconceivably sad. Like a priest from whom one has torn his divinity, I could not, without heartbreaking bitterness, leave this so monstrously seductive ocean, this sea so infinitely various in its terrifying simplicity, which seemed to contain in itself and represent by its joys, and attractions, and angers, and smiles, the moods and agonies and ecstasies of all souls that have lived, that live, and that shall yet live.

In saying good-bye to this incomparable beauty I felt as though I had been smitten to death; and that is why when each of my companions said: “At last!” I could only cry “Already!”

Here meanwhile was the land, the land with its noises, its passions, its commodities, its festivals: a land rich and magnificent, full of promises, that sent to us a mysterious perfume of rose and musk, and from whence the music of life flowed in an amorous murmuring.

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers