The Paris Review's Blog, page 713

April 23, 2014

Down to the Wireless

Mike Licht, Women of Wi-Fi, after Caillebotte. Image via Flickr

Someone in my building—or maybe two different people, I don’t know—rejoices in cruel, taunting names for his wireless networks: “MineNotYours” and “NoFreeLunch.” “I’m just going to go out on a limb here,” my old boyfriend once said, “and speculate that this person is an asshole.”

But is he? Riding in the elevator or passing neighbors in the hall, I often wonder who it might be—the retired nurse upstairs? The mild-mannered gentleman with the rescue dogs? The 103-year-old who sits with her nurse in the lobby? Does someone have a small, secret life as a righteous, anonymous enforcer?

A few are more transparent. “Miguel21” is not hard to guess; “AngieandTommyWirelss” too. I’m assuming “Yankees” belongs to the guy who’s always duded up in Bombers regalia. And presumably, anyone who cared could guess that “PymsCup” was mine.

Others have a whiff of intrigue. Who is “StinkyTofu”? Wherefore “ChouChou”? And is “CaliforniaDreamin” really so unhappy living here in New York? I hope not.

Such is city living: anonymity and proximity and small, petty mysteries and the occasional reminder of another’s tastes and likes and feelings. It is half misconceptions, of course. Back when I lived in Greenpoint, we just assumed that the hulking retired paratrooper with the penchant for Final Fantasy had the network called “Bonecrusher.” We referred to him this way as a matter of course, and without mockery. We had lived there for a year before we learned that, in fact, he was “MondayImInLove”—and, incidentally, that he loved The Cure.

This is not a decision one ponders much—at least, I didn’t. You choose it in a moment, try to think of something you’ll remember, perhaps. Some are happy to live with a string of numbers. And yet it is how you are known—or not known—by many of those physically closest. Or perhaps it takes on a life of its own. I know “NoFreeLunch” and “MineNotYours” is unnecessarily confrontational, unpleasant, even. I mean, we all have locks on our networks—no need to belabor the point, or engage in such gratuitous chest-beating. And yet, there is something I like about it. Every time I log on, there it is: an assertion of personality—that which is, or could be, or maybe only exists in this small, insignificant domain.

Vote for the Daily (or Else)

A still from Lyndon Johnson’s notorious “Daisy” attack ad, 1964.

You may not have known it, but The Paris Review is nominated for two Webby Awards: one for best cultural blog and one for best “social content and marketing” in arts and culture. The winner of the People’s Voice award is determined by popular vote; the deadline is tomorrow at 11:59 p.m.

We’re honored by the nomination and we hope we can count on your support, but we’re not one to beg for votes—we’ve run a clean, dignified, gentlemanly campaign, free of pandering, slandering, smears, and slurs. But what has that gotten us? Four percent of the popular vote.

Fuck the high road: we’re going negative.

As of this writing, Mental Floss leads the cultural blog category with sixty-six percent of the vote. They are, on the face of it, an upstanding publication. Their site currently features a video of an amoeba eating human cells alive; ours, by contrast, features a video of our associate editor being smacked in the face with a bag of water.

But who are these people, really? Can you trust a periodical whose title puns on dental floss for your cultural blogging needs? What does it mean to be a Flosser? We asked our friends at Urban Dictionary, and the answer will astonish you:

There you have it. These people are, by their very definition, unreliable. So how did they come by a whopping sixty-six percent of the vote, you ask? Easy: in flagrant breach of Webby campaign decorum, they ran a constant advertisement on the bottom of their site. The Daily would never stoop to such lows; we never advertise.

But it gets worse—the Flossers’ gall knows no bounds. A very reliable source indicates that they’re gaming the system:

Your choice, then, is clear. To quote another levelheaded campaign ad: These are the stakes! To make a world in which all of God’s children can live, or to go into the dark. We must either love each other, or we must die.

Vote for The Paris Review on April 24. The stakes are too high for you to stay home.

Shakespeare, Heartthrob

Reclaiming the Bard for the common man.

Tom Hiddleston as Coriolanus in Josie Rourke’s production at Donmar Warehouse.

There was a time when attending a motion picture was not an occasion but an event. Most of the great movie houses that might remind us—the Roxy in Times Square, Fox Theater in San Francisco, the Loews Palace in DC—are long gone, but the Music Box remains. A local landmark on Chicago’s North Side, the theater still has its Austrian curtains, house organ, and even a hoary legend: the ghost of Whitey, the house manager who ran the theater from opening night in 1929 until Thanksgiving eve, 1977, when he lay down for a cat nap and passed away in the lobby.

The Music Box is an 800-seat theater, more than three times the size of Donmar Warehouse, another theater nearly four thousand miles away in London. What brought the two houses together was Shakespeare’s Coriolanus. A recent performance at the Donmar was beamed live, and later rerun, to cinemas all over the world as part of Britain’s National Theater Live series. It was the first time the Music Box telecasted a production that completely sold out.

In Shakespeare’s canon, Coriolanus sits somewhere between rarely remembered plays like Pericles and Two Gentlemen of Verona and stock selections like King Lear and Romeo and Juliet. A story of pride and political intrigue plucked from Plutarch’s Lives, the play is a little like an olive: a bitter fruit from Rome and something of an acquired taste. Its title character is one of Shakespeare’s great creations—for an accomplished actor, a role almost as inevitable as Iago or Macbeth. T.S. Eliot called the play “Shakespeare’s most assured artistic success;” he admired it so much he wrote two “Coriolan” poems with an eye toward an unfinished tetralogy.

It’s unlikely enough that an art-house movie theater would sell so many tickets to a telecast of Coriolanus—but I should add that this was a morning matinee in Chicago on a frigid Sunday in February. When I arrived, then, I wasn’t exactly worried about finding a place to sit—but I was bewildered to discover a packed house where I expected an acre of open seats.

I found mine between two accommodating couples in the second-to-last row. At the other end of the theater, Coriolanus was already blasting the Roman peasants—you dissentious rogues—for daring to demand grain. For Shakespeare’s surliest character, he was quite comely, and considerably younger than the middle-aged men who typically inhabit the role. He was also the reason why the audience looked suspiciously like a pep assembly.

If the name Tom Hiddleston means nothing to you, you probably missed last summer’s Thor: The Dark World, in which Hiddleston reprised his role as Loki, the mischief-making demigod who has become the most successful villain in the Marvel movie universe. You almost certainly didn’t vote him MTV’s “Sexiest Man in the World,” a title he won last December in a 77-percent landslide. That victory was thanks to the very girls (and not a few boys) who were drawn to the Music Box that morning: they came not for Shakespeare’s gilded syllables, but for Tom’s sportive grin.

It has transatlantic appeal. The host of the telecast noted that the theatrical run at Donmar had sold out in twenty-four hours and that she had been surrounded at an earlier performance by “school kids” who “stood up and screamed their appreciation.” Her experience echoed my own and that of the handful of others who were drawn to the Music Box not for an international sex symbol but for the Sweet Swan of Avon. The sell-out was such a surprise to some regulars that a staff member took the stage at intermission to assure them the $15 tickets had not been handed out gratis (and to inform the irregulars that an encore performance would be scheduled ASAP).

I hope the grumbling was minimal. The last thing Shakespeare needs is votaries standing akimbo-armed before the front doors of the theater. Yes, the plays constitute some of the sublimest heights of human expression, but Shakespeare could also tell a good fart joke. If we sometimes overlook that, it’s because an aspic of expectation has embalmed the Bard. We don’t simply watch the plays—we bear witness, with the result that contemporary audiences can sit through entire performances with the kind of rigid composure better suited to being held at gunpoint.

It wasn’t always that way. Pick up Shakespeare in America, an anthology published by the Library of America this month to coincide with the Bard’s four hundred and fiftieth birthday today. A miscellany of poems, speeches, letters, and assorted ephemera, the book reminds us that, in this new England of ours, the admiration and appropriation of Shakespeare have most often been unabashedly demotic.

One of the first selections is an epilogue to Coriolanus by the Revolutionary War poet Jonathan M. Sewall. It was offered as an addendum to the play when it was performed for (and, perhaps, by) war-weary American troops stationed in Portsmouth, New Hampshire. Though Coriolanus is often seen as a tale of liberty reaffirmed and loyalty rewarded, Sewall draws a parallel between the American troops’ rebellion and that of the title character:

A diff’rent scene has been display’d to night;

No martyr bleeding in his country’s right.

But a majestic Roman, great and good,

Driv’n by his country’s base ingratitude,

From parent, wife, and offspring, whelm’d in woe,

To ask protection from a haughty foe:

To arm for those he long in arms had brav’d,

And stab that nation he so oft had sav’d.

If Shakespeare was called upon to consecrate the divide between the colonies and home country, he could also split Americans. My favorite selection in Shakespeare in America is an anonymous pamphlet describing New York’s infamous Astor Place Riot of 1849. A simmering feud between the American actor Edwin Forrest and British thespian Charles Macready came to a head when Macready was invited to perform Macbeth at the tony Astor Place Opera House. Across town, Forrest decided to put up the same play in the popular confines of the Broadway Theater. The dueling performances became a contest—who were the rightful heirs of Shakespeare’s legacy, the aristocrats or the people? The people, for their part, tried to hasten a decision by breaking up Macready’s first performance: “Rotten eggs were thrown, pennies, and other missiles; and soon, still more outrageous demonstrations were made, and chairs were thrown from the upper part of the house so as to peril life.”

The performance, understandably, ended early. Yet Macready, undeterred and urged on by the city elite, agreed to a second performance three days later, one that would be guarded by hundreds of police and “several regiments” of the National Guard. They were needed: fifteen thousand people converged on the Opera House to disrupt the performance, and a battle ensued that saw over twenty people killed and scores more wounded.

Though history doesn’t tell of a similar contest on the other side of the pond, Shakespeare’s plays there were hardly subdued events. The Globe itself was never so silent unless the theater had emptied, and patrons had no qualms about delivering parting shots to an especially poor performance. Like contemporary audiences for a Thor movie, they had paid money for diversion and delight. Hamlet—even Hamlet!—was entertainment before it was art. Indeed, it survived as art only because it first excelled as entertainment. The unruly devotion of Elizabethan audiences preserved the plays for us, and the revelry of the uninitiated—with its laughter, sighs, and shrieks of delight—better approximates their humor than the gray liturgy of “art appreciation.”

It also recalls what it must have been like at the first night of a new play, an encounter with something unknown and extraordinary. At the encore telecast—I went, the Donmar production is superb—I bumped into a friend. She knew little of Coriolanus. She simply trusted the playwright and admired the leading man. They had entertained her before; it seemed safe to conclude they would do so again.

We sat together in the oblong theater, under the cobalt colored ceiling where tiny lights twinkle to indicate the stars. I said nothing of what was to come, from the hugger-mugger over hungry bellies to war-by-other-means to, at last, the incarnadine conclusion. I wanted that experience of Shakespeare, if only vicarious, of something entirely unexpected. So we watched, and when the stage fell dark and the players assembled for a bow, we did what seemed natural: we cheered.

John Paul Rollert is a writer in Chicago. His work has appeared in The Los Angeles Review of Books, Boston Review, and The New York Times.

Solitude & Company, Part 3

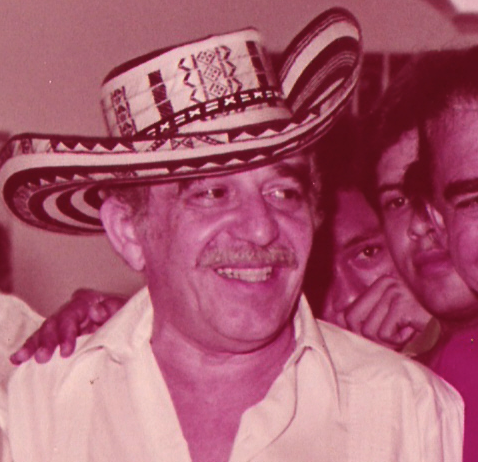

Photo: José Lara, via Wikimedia Commons

In our Summer 2003 issue, The Paris Review published Silvana Paternostro’s oral biography of Gabriel García Márquez, which she has recently expanded into a book. In celebration of García Márquez’s life, we’re delighted to present the piece online for the first time—we’ll be running excerpts throughout the week. Read the previous installments: Monday, Tuesday.

V

MARÍA LUISA ELÍO: After a lecture, a group of us went to Álvaro Mutis’s house. On our way there, I had Gabriel next to me, and he started talking. When we got to Alvaro’s house—he had a tiny apartment—everyone had heard Gabo’s story so they scattered in various directions. I was so moved by what he was telling me that I latched on to him and said, “Tell me more. What happens next?” He told me the entire story of One Hundred Years of Solitude. From the very beginning. I remember he told me about a priest who levitates, and I believed him. I said to myself, Why can’t a priest levitate? After he told me the entire book, I said to him, If you write this, you will be writing the Bible. He said, Do you like it? And I said, It’s amazing. And he said, Well, it’s for you. I guess he saw me listening with such innocence that he thought, I’m going to dedicate my book to this fool. At that point he hadn’t started writing the novel. He had written notes but nothing else. I know because the room that Mercedes had built for him so that he could write all day hadn’t been built. They lived in a small house on La Loma, and in their living room Mercedes had someone build a wall up to the ceiling to avoid the noise, with a door. She put a pine table and a typewriter in the room. The room was very, very small. There was room for his table, a chair, and some sort of little easychair. Those were the only things that could fit. Above the easychair there was kind of a picture, something that resembled a calendar, a very tacky calendar that Gabo had hung there. Gabo went in that room and wrote all day. She built that room because Gabo had said, “I have to withdraw for a year, and I’m not going to work. See what you can do to manage.” She managed the best she could. She got credit at the butcher’s shop—later on when Gabo was famous he went back to the butcher to thank him. We started visiting them every night, one night with a bottle of whiskey, another night with a piece of ham.

SANTIAGO MUTIS: Money ends, and Mercedes, so as not to bother him, pawns her hair dryer and the blender.

GUILLERMO ANGULO: Gabo has something that doesn’t exist in Colombia—discipline. Before getting married, I had a very unlucky night—I had two women. That’s one of the worst things that can happen to a man, because there’s nothing you can do. So I thought that Gabo would be the solution. So I went to him, and he said: “I have to correct chapter three.” I asked him if he had a contract he had to fulfill, to which he replied that he had imposed that deadline upon himself and he was going to correct that chapter that very evening. There was no way to convince him otherwise, no ifs-ands-or-buts about it.

ENRIQUE SCOPELL: He sent me a questionnaire when he was writing No One Writes to the Colonel, about two thousand questions. I’ve been involved in cockfights all my life. I’m the one in the cockfights, but only up to a point.

MARÍA LUISA ELÍO: He used to phone me. He would say, “I’m going to read you a fragment and you tell me what you think of it.” Or, “I’m going to tell you how the women are dressed. What else do you think they should wear? What color should the dress be”? Or, “I’m using this word here and I don’t know what it means. Did your aunts used to use this word, because mine did.” It was wonderful.

ENRIQUE SCOPELL: He’s very tenacious. He stuck to One Hundred Years for twenty years.

GUILLERMO ANGULO: He tried to write One Hundred Years early on. At the beginning he called it his mamotreto [bulky notebook]. It was not spoken of; he could not write it. He knew the novel needed a writer with more experience, so he waited until the day he became the writer capable of writing One Hundred Years. It has to do with command of technique. You need a great deal of technique to write a novel like that. He knows the tale; he has the characters and storyline; but he couldn’t write it. You have a novel that has to be typewritten, but you can’t type, so you have to wait until you learn to type it up; the novel is there, waiting.

ENRIQUE SCOPELL: He sent One Hundred Years to Argentina, Mexico, and Spain. And all three countries rejected it. The Spaniards and the Mexicans told him they were not interested, but the Argentines told him to devote himself to something else.

MARÍA LUISA ELÍO: I remember the day the book was published. We got crazy. He brought me a copy, then we went from bookstore to bookstore buying books for my friends and making him write dedications. Gabo told me, You’re heading for financial ruin. I was buying all the copies I could afford. We went to Gabo’s house and drank toasts with Mercedes. The following day, well, we didn’t have any money back then, neither do we have any nowadays, but we manage. You probably remember that there’s a passage in One Hundred Years … where it rained yellow daisies. Well, that day I bought a large basket, the largest I found, and I filled it with yellow daisies. I had on a gold bracelet, so I took it off and put it in the basket, then looked for a little gold fish and a bottle of whiskey. I put it all in the basket and we went to their house.

SANTIAGO MUTIS: Gabo traveled to Buenos Aires because he was a judge for a novel competition; coincidentally One Hundred Years had just been released the previous week. When he entered the theater they introduced him as the author of One Hundred Years, and the entire theater gave him a standing ovation. That’s where and how he started, and it has not stopped since. It wasn’t something he was looking for, but it struck him like a bull. The world came to his feet.

RAMON ILLÁN BACCA: When he won the prize for One Hundred Years my aunt’s comment was, “Oh! Who would have ever thought Tranquilina’s grandson could be so intelligent!”

ENRIQUE SCOPELL: That novel is no good. A lousy novel about local customs and manners. I’m sure people from Bogotá don’t understand half of it. There’s nothing imaginative about it. I mean, you can say this and that about Romeo and Juliet, but Christ! at least it’s about love.

SANTIAGO MUTIS: The entire world understands it because it is an epic, a bible. It tells the story of life itself from beginning to end—a human version, with a very Colombian truth. It is life as it is lived here. Colombia is a magical country; the people believe in that. When you go to a market fair in Villa de Leyva, the people spray the truck with holy water so that it won’t fall off the road. I think this is what happened with Gabo: the nation had an oral tradition, and that oral tradition started to get closed in a bit; the cities began taking on an important role. When the popular culture began to be threatened—to stop being oral—Gabo was there to pick it up. It starts to pass into literature; he senses it, starts to refine it—it’s his parents, his family, his land, his friends, it’s everything. Pop culture is the mother and father of art—that is Gabo.

RAMON ILLÁN BACCA: Here on the coast you hear so many things that are in a fashion magic realism, but are equally a part of the culture. For example, I’ll tell you a story that I relate in my novel. Professor Dario Hernandez was in Brussels studying piano, just like the rest of the well-to-do people of Santa Marta. He played before Queen Astrid. He returned in 1931 or 1932. Naturally, in the Santa Marta Club, which had just been inaugurated, they asked him to play something. So he played Claire de Lune. They asked him to play something else, so he played Chopin’s La Polonnaise. Then he played Sueno de Amor by Liszt. “So that’s what you went there to learn? Don’t you know how to play ‘Puya, puyards’?”—a local song. Dario got very insulted and he slammed the piano top down and said, “This town will never hear me play one single note ever again!" He lived until he was in his nineties. When he did that, he was thirty. He lived another sixty years, in a house he shared with two aunts. He put cotton on the strings of the piano so that the only thing people could hear was clap clap clap when he practiced every morning. If that’s not magic realism, then what is?

JOSÉ SALGAR: You cannot make up fantasies; you have to tell exactly what is out there. He used to listen to his grandfather tell tales, the magic-realist tales from the coast, so he had all of that in his head. Then his literature professors told him to read this and that, and he said to himself that if they could do that then he could do the same with his grandfather’s tales. That is the first spark of magic realism. Magic realism means saying things exactly—start from the truth and enhance it. This phenomenon, created by García Márquez, managed to embellish journalistic language. He added beauty to the truth. The most classic example might be the time when Gabo asked to speak with the pope about Cuban prisoners. A Polish countess in Rome calls him in Paris at five A M. and tells him to leave immediately because she has gotten him a seven A.M. meeting with the pope. So he leaves Paris and heads for Rome. I think that a friend loaned him a blazer, which was too tight on him. The guards let him in, and there was the pope all in white and Gabo all in black. They made eye contact. Gabo noticed a very shiny wooden floor and a table, which they went to. The doors were closed. Then they were alone. I remember that Gabo told me he thought, What would my mom say if she saw me here? That evening Mercedes asked him how it had gone and if there hadn’t been anything unusual. So the story begins. “I don’t know … but hold on, the thing with the button. I was wearing the blazer and, when the time came to bow, the button jumped off the blazer. I could hear it tinkling under the center table. The pope beat me to it; he bent down and I could see his slipper and then he straightened up and gave me the button. When we were leaving the room the pope did not know how to open the door. He had to call the Swiss Guard. They got us locked in and the pope could not get out.’’ The story got longer and longer, and he mixed the countess in with the rest and in no time he turned it into another One Hundred Years of Solitude.

RAMON ILLÁN BACCA: Well, everyone cooks with parsley, but there’s always one cook who takes it to an artistic level. Right? His genius lies in that.

JOSÉ SALGAR: Magic realism is a label people gave it after he became famous; he didn’t realize it because he was obsessed with only one thing: to tell the story. Why? It wasn’t to make money, and he wasn’t in pursuit of prizes. The reason for his writing was so that his friends would love him more.

Silvana Paternostro is a journalist who has written extensively on Cuba and Central and South America. She is the author of In the Land of God and Man: Confronting Our Sexual Culture and My Colombian War: A Journey Through the Country I Left Behind.

Read the previous installments of “Solitude & Company”: Monday, Tuesday.

The Logistics of Ark-Building, and Other News

Simon de Myle, Noah's Ark on the Mount Ararat, 1570

Will García Márquez’s unpublished manuscript ever see the light of day?

The eagerly anticipated third edition of the OED won’t appear until 2034—and it probably won’t be available in print.

“The ark is the first impressive man-made creation, the world’s first ambitious piece of technology. In the world of Genesis … a world of slick-talking snakes, cherubs with flaming swords, and guys who live to be eight hundred years old—the ark gives us something pragmatic, something with worldly dimensions. In other words, some literary realism.”

Meanwhile, in 1895: What compelled Paul Gauguin to take off his pants and play the harmonium? Science may never know.

Hey, hotshot: “the way we Americans casually, often unthinkingly, incorporate gun metaphors into our everyday slang says a lot about how deeply embedded guns are in our culture and our politics, and how difficult it is to control or extract them.”

April 22, 2014

United Nations

Giovanna Garzoni, Still Life with Bowl of Citrons, late 1640s.

We are currently in the midst of what will almost certainly not be referred to as the Great Lime Shortage of 2014. Following the decimation of the domestic lime crop in the 1990s, the United States is now largely dependent on foreign imports. And this year has provided a perfect storm of difficulties for growers. Quoth the New York Post,

A huge shortage is the result of a nasty cocktail of conditions in Mexico, where 97 percent of US limes are grown. Heavy rains knocked the blossoms off many trees, reducing yield. A bacteria that’s long been ravaging citrus trees in Mexico didn’t help either, but the real trouble came when criminals and drug cartels started looting the groves and hijacking delivery trucks.

A case of limes used to cost as little as $30; prices have shot up to as high as $200. And the limes are smaller—golf-ball-size fruit that doesn’t produce much juice.

The reaction, needless to say, is panic. People are looting and pillaging and smuggling. There is a black market; there is inflation. Slices of lime are being doled out or husbanded or hoarded like precious medicines in an epidemic. The resourceful are substituting cut versions of the juice, or creating new recipes. In the grand tradition of such things, the veneer of civilization has quickly eroded, and the lime-deprived populace is left clamoring, bestial, ruthless.

Of course, there is always lemon. Lemons are cheap and plentiful. If you’re concerned about scurvy, you ought to know that the lemon contains four times the vitamin C of its green cousin. It’s also less likely to leave a bartender’s skin mottled with phytophotodermatitis.

Time was, presumably, even the most pampered city dweller had a certain understanding that the earth giveth and taketh away; that what we eat—and plenty of livelihoods—are dependent on the vagaries of weather and blight. But, in the words of Time, even after the Florida lime groves were devastated by Hurricane Andrew, “people still wanted their margaritas and ceviche.”

And just in case the great graduate student in the sky doesn’t have quite enough material to work with, I leave you with this:

When asked if she’d try a lemon margarita, Bernadette, a 27-year-old from Jersey City, grimaced while drinking at Burning Waters on Thursday.

“I think I would throw the lemon wedge at them. What’s the matter with you? It’s not the same,” says Bernadette, who declined to give her last name because she didn’t want her United Nations colleagues privy to her drinking habits.

Slow Day at the Review

Here’s one way to kill time—and brain cells.

An Irresistible, Almost Magical Force

Johann Heimlich Wilhelm Tischbein, Goethe in the Roman Campagna, 1787.

There were no best-seller lists in 1809, but it was quickly clear to the German reading public that Goethe’s third novel, Elective Affinities, which appeared in the fall of that year, was a flop. His first, The Sorrows of Young Werther, had inspired a fashion craze and copycat suicides, and had fired the heart of a young Napoleon. His latest effort, on the other hand, received befuddled notices from critics and little love from the coterie of writers and philosophers drawn to the Great Man. Everyone from the Brothers Grimm to Achim von Arnim to Wilhelm von Humboldt agreed that the book was a bore, that its plot made nearly no sense, and that its treatment of adultery bordered on the distasteful.

At sixty, Goethe was not one to let bad reviews get him down. The universally beloved Faust had appeared in 1808, and by 1810, Goethe was to have completed his Theory of Colors as well as his autobiography, Poetry and Truth. Nonetheless, in the correspondence he sent out around the time of publication, Goethe found himself compelled to admit that he had as little idea as anyone else of what he was trying to accomplish with his most recent book, or of what it had finally become. Then as now, Elective Affinities is an incredible, deeply mystifying read, the headstone of a man who hoped to groom the wilderness of life into an English park where even loss, pain, and death have finally found their proper place.

It’s difficult to pinpoint what makes the novel so elusive, in our time as in Goethe’s. The book is neither long nor dense; its characters’ motives are not hard to fathom, its plot not difficult to follow. In fact, Elective Affinities is the rare book that opens by spelling out what will happen by its end. The protagonists, Eduard and Charlotte, are aristocrats who have overcome loveless marriages to find true love with each other. At the start of the story, they invite Eduard’s childhood friend, the Captain, to live with them, ostensibly to help out with various projects around the estate. Soon after his arrival, the Captain, a dilettante scientist, explains the principle of elective affinities to the couple—how the elements of a seemingly stable compound, such as limestone, will separate and form a new combination when introduced to sulfuric acid. With Charlotte’s beautiful but withdrawn niece Ottilie due to arrive shortly, the company observes how amusing it would be if, like the limestone and the sulfuric acid, Eduard rushed to Ottilie while Charlotte paired up with the Captain. (No points for guessing what happens next.)

Chemistry is, to be sure, hardly the most inventive metaphor for romantic feeling. And yet, as Charlotte observes, we often forget just how much of natural science, which we take to be the inalienable reality of our existence, is informed by the human experience it is meant to illuminate. Elements don’t elect to do anything; they just rush together blindly, machinelike. Nor are the “laws” of thermodynamics freely legislated—they just are. Everywhere Goethe’s characters look, they see portentous signs that give the action a sense of fatefulness, as though it were being propelled by an “invisible, almost magical force of attraction.” Eduard discovers that he and Ottilie have the same handwriting; a visiting Englishman reads from a novella that perfectly describes the plot up to that point. All the while, Goethe reminds us, via the supporting cast, how often we misread the world in order to dress up self-serving behavior for which we are reluctant to take responsibility. What begins as a rather slight take on the romantic tribulations of the moneyed class gradually unspools, in Goethe’s hands, into a meditation on the murkiness of the laws that rule us—on the “riddle of life,” as the narrator calls it, for which we only ever find the answer in one another.

* * *

The biggest obstacle between Goethe and his American readership has always been his style. Only Goethe could write a sentence like “He took note of all the beauties which the new paths had made visible and able to be enjoyed,” skipping, in typical Goethe fashion, right past the actual beauty to linger on the sensibility of organization that makes it possible. When his dialogue and scene direction are not delivering one perfectly crafted aphorism after another, they’re bare and utilitarian. (At a dinner party, Charlotte, “wishing to get away from the subject once and for all, tried a bold shift of direction and was successful.”) And then there is Goethe’s strangely limited vocabulary, which favors simple yet maddeningly untranslatable words—like bedeutsam—that never sound quite right, no matter how they are rendered. (“These wondrous events seemed to her to presage a significant future, but not an unhappy one.”) Goethe’s English translators have always turned the clarity and placidity of his prose into something flat and wooden—although, in their defense, Goethe was never really one to wrangle for le mot just to begin with. By the time of Elective Affinities, he dictated his works entirely to his secretary. The privy councilor to the Duke of Weimar was simply too busy to spend the day trying to decide if scarlet sounded better than vermillion.

It doesn’t help Goethe’s case that how his characters spend their days seems, for lack of a better word, insane. The newest Oxford Classics edition of Elective Affinities misleadingly promises a scathing critique of aristocrats “with little to occupy them.” If anything, Eduard and Charlotte have too much to occupy them. Their music-playing and constant replanning of the grounds of their estate seem straightforward enough; before long they are reorganizing their graveyard, examining old Germanic weapons, and planning birthday parties with all the seriousness of imperial coronations. In the book’s most famous scene, Charlotte’s party-girl daughter, Luciane, arrives home from boarding school and insists that everyone dress up and pose as their favorite painting. Just before that, she has Charlotte’s architect draw a mausoleum behind her while she pretends to be the queen of Casia, mourning for her lost husband. When that gets boring, she pages through an illustrated book of monkeys and compares each one to someone in the room. (“How can anyone bring himself to do such careful pictures of those horrible monkeys?” a horrified Ottilie asks her diary.)

A recent piece in n+1 astutely observed that though Goethe was enough of a nineteenth-century author that we expect to understand him easily, he was ultimately too much of an eighteenth-century author to really like. Nowhere is this clearer than in Elective Affinities’s very slippery sense of what it means to do something. Occupation, in the middle-class sense that would come to define the nineteenth century—making things, buying things, selling things—held little interest for Goethe. His great ambition, in his life and in his art, was to take the indefatigable work ethic of the bourgeoisie and apply it not to business, but to life itself, as only an eighteenth-century aristocrat could. Eduard and Charlotte don’t bother composing music or writing novels. The object of their artistic aspiration—as their fascination with botany, landscape architecture, and tableaux vivants attests—is reality itself. Considering that by the novel’s end two of the main four characters are dead, it might be persuasively argued that Elective Affinities is a meditation on the vanity of our desire to mold reality to our liking. But no matter how grim the plot, Goethe’s narrators are never shaken in their values. There is no surer sign that we are to admire one of his characters than when we learn that, through tireless labor, they have restored some room or building that has fallen into disuse, or that, by applying their considerable expertise, they have revealed the beauty dormant in a grove of plane trees or a garden path.

The great mystery, then, is that despite its fixation on death, loss, and the inscrutability of fate, Elective Affinities never wavers in its optimism. At no point does the narrator ever concede his claim to the final truth of life, which he offers to the reader piece by piece, in one brilliant aphorism after another. (To take just one example: Ottilie’s famous observation that no one is more fully a slave than when they believe themselves to be free.) It’s easy to confuse Goethe’s stoic acceptance of life’s vicissitudes for a lack of feeling. But in his first work to his last, renunciation has always gone hand in hand with emotion—as when Ottilie, in a sign of devotion to Eduard, hands him the portrait of her father she wears around her neck. For Goethe, true happiness is not simply a religious or ethical abstraction, but something palpable and real. Art’s ambition, as Goethe saw it, was to still the rush of the world to reveal those vertiginous instants when all of eternity seems to be gathered into what is nearest at hand, and, no longer ruing the past or fearing the future, we finally feel at peace. The highest feeling in Elective Affinities is not ecstasy, but serenity.

Goethe’s age was, in retrospect, the last time when literature might credibly have claimed that it could reconcile the different sides of life into a happy, harmonious whole. In a letter to Carl Friedrich Zelter in 1825, seven years before his death, Goethe wrote, “The world admires wealth and velocity—these are the things for which everyone strives. Railroads, the post, steamboats, and all possible modes of communication are the means by which the world overeducates itself and freezes itself in mediocrity. We will be,” he concluded, “with a few others, the last of an epoch that does not promise to return any time soon.” If Goethe is alien to us now, as he was to the crop of writers who replaced him in Germany, it is because we are the children of the “clever minds and quick, practical men” who took over the reins of history from the “enlightened” despots he preferred to see in charge. Just the same, it is a testament to the depth of feeling that suffuses Elective Affinities—an incredible patience with life, rather than a hatred of it—that Goethe’s optimism is still legible to us today.

Michael Lipkin is a student and writer living in New York City. His writing has appeared in n+1, The Nation, and The American Reader.

Solitude & Company, Part 2

Márquez in 1984. Photo by F3rn4nd0, via Wikimedia Commons.

In our Summer 2003 issue, The Paris Review published Silvana Paternostro’s oral biography of Gabriel García Márquez, which she has recently expanded into a book. In celebration of García Márquez’s life, we’re delighted to present the piece online for the first time—we’ll be running excerpts throughout the week. Read yesterday‘s installment here.

III

JOSÉ SALGAR: Gabo came to El Espectador with a bit of fame, but when he arrived it was the same as any ordinary reporter. He was a bit uncouth; he was from the coast, a hick, and very shy. He would arrive with bags under his eyes and his hair uncombed because he had been writing that thing. I told him we couldn’t work like that. I would tell him to wring the swan’s neck—that literature was a hobby and what he needed to do was incorporate those things that he was making up into real journalism.

JUANCHO JINETE: He wrote something about the wreck of a ship that belonged to the navy, which was carrying smuggled goods and threw one of the young sailors overboard. He wrote an article that no one dared to write in this country, because it dealt with the armed forces.

GUILLERMO ANGULO: It must have been around 1955, I went to El Espectador looking for him and they told me he had left to be one of their correspondents in Europe and was going to study film at Centro Sperimentale in Rome. He has always had a love affair with film. It’s been disastrous. There isn’t even one great film or script by Gabo. His ideas are wonderful, but his writing cannot be used to make movies. It seems to me a bit much to ask Gabo to be a great filmmaker in addition to a great author. I was going to study at the same place, so when I arrived there I went to look him up. He had left me a letter in which he explained where to get a hold of him: I should go to the second floor and I would run into a lady who sings opera wearing a towel wrapped around her head. So I went there and sure enough the lady showed up and I laughed and she got angry. I laughed because she came out singing opera with her head in a towel. Then I asked her about Gabriel García Márquez. She said, Who knows him? And she was right. Who had ever heard of him? Then Gabo sent me a letter telling me that he had left Rome for Paris. He was at 16 rue Cujas. I wrote him that I was going to be in Paris for six months and that we would see each other there.

PLINIO APULEYO MENDOZA: We drove from Paris to Eastern Europe in a Renault 4. We couldn’t get visas for the Soviet Union so we pretended to be part of a group of Colombian musicians playing in Moscow. We would sleep in the car. One day Gabo woke up and told me, “Maestro, I am very sad. I dreamed something very sad.” I asked him what that was, and he said, “I dreamed that socialism didn’t work.”

GUILLERMO ANGULO: I arrived at the Hotel de Flandres on rue Cujas. Across the street, there was a black Cuban poet [Nicolas] Guillen. He was exiled and living in a hotel more pathetic than mine. Every day he went out and returned with his bread under his arm. When I went to 16 rue Cujas the lady told me that García Márquez had left for a tour of the Iron Curtain. I was convinced that I would never be able to meet him. I asked for the cheapest room she had and told her that I would be staying for at least three months. She gave me a room on the top floor, which was very uncomfortable because that’s where the roof was, so that every time you got up you hit your head on the ceiling. One day I got a knock on the door and here was this guy wearing a blue sweater and a very long scarf that went around several times and he said: “Maestrico, what are you doing in my room?” It was Gabo and that’s how we met. I didn’t know. And I have a photograph taken right then and there. I moved elsewhere. Gabo was very, very poor, and while I was there he came every day to have dinner with me. I used to keep five subway tickets, and he would take two on his way out and ask me what to read because his train ride was about forty-five minutes and since I’ve always been an avid reader of magazines I had Cahiers du cinema and Paris Match. He would take what he wanted and bring it back the following day. And that’s how we became very close friends.

PLINIO APULEYO MENDOZA: His room had a typewriter that my sister had sold to him for forty dollars and on the wall with a thumbtack a picture of Mercedes, his girlfriend back in Colombia.

MARÍA LUISA ELÍO: Well, you know, he met Mercedes when she was a little girl. Once, when she was about eleven, she was in her father’s pharmacy when Gabo walked in and told her, “I’m going to marry you when you’re an adult.” And then, when she was older, he told her: “You should marry me because I’m going to be very important.” I think he knew all along.

GUILLERMO ANGULO: One day he got a postcard from his friends at La Cueva, with lots of palm trees and sunshine, in which they wrote, Jackass, you’re over there bearing the cold and here we are having a great time in the sunshine. Get your ass back here. And he thought, Goddamn assholes, instead of sending me some money. And he threw out the postcard.

ENRIQUE SCOPELL: Back then it was forbidden to send money by mail. Alvaro gave ninety dollars and I put in ten. Alvaro was more his friend than I was, because of the writing. The glue was bad and if you wet it you could unseal it, and Alvaro stuck the hundred dollars in it.

GUILLERMO ANGULO: Shortly thereafter, Gabo received a special-delivery letter: Since you’re so stupid we’re sure that you didn’t even notice that the postcard is a sandwich with one hundred dollars in it. Then he went down to where the hotel kept its garbage. Just imagine, condoms, all that junk, and he retrieved it. One hundred dollars. It was Saturday, and that was when changing dollars into francs at a good rate was very difficult. He was desperate because he was hungry, so he started to inquire where he could change the money. Someone told him about a friend called La Pupa who had just gotten in from Rome after getting paid her salary and should have a lot of money on her. So he went to see her—he was bundled up as usual, since it was wintertime—and La Pupa opened the door and a current of warm air from a well-heated room greeted him. La Pupa was naked. She was not pretty, but she had a great body and she would take her clothes off without any provocation. So La Pupa sat down— according to Gabo, what bothered him most was that she carried on as if she were fully dressed—and crossed her legs, and started to talk about Colombia and the Colombians she knew. He started to tell her his problem, and she acknowledged him and went across the room to where she had a little chest. He realized that what she wanted was to have sex, but what he wanted was to eat. So he went to eat and pigged out so much that he was sick for a week with indigestion.

JOSÉ SALGAR: They closed the paper and he got stuck in Europe. Then he wrote and told me everything about his love affairs and the painful experiences that he was having in Paris. Very long letters, and he would wind up begging me to get him the check that the paper owed him, since that was his only means of income. He called me the other day and asked me if I remembered anything about those letters. My answer was very sad. “Well,” I said, “I threw out everything that was sent to the paper and didn’t get printed.”

SANTIAGO MUTIS: What was it that Paris gave him? Paris gave him a brutal confinement, and a way to ask himself who he was, what he was doing. He falls flat on his face, and it defines him as what he has always been—a man from Barranquilla, from Cartagena, from Aracataca. Today’s Gabo—I don’t know why—is a Gabo who fabricates himself. Now he tells this story and it is literary, which doesn’t mean it’s true.

* * *

IV

RAFAEL ULLOA: He had achieved a certain prestige as a journalist. But he began making a name for himself when he got the Esso Prize for In Evil Hour. That’s where it all started, from that point on.

GUILLERMO ANGULO: I’m the one to blame for the first award Gabo ever received. One day I noticed that there was a contest being held, and the first prize was fifteen thousand pesos. Enough to buy a car—the first Volkswagens cost three thousand eight hundred pesos. Gabo already had made a name for himself as a journalist, and although he had not done anything major in the literary sense, people knew about Leaf Storm. He was already respected, based on expectations rather than anything tangible. He sent me his novel, which came bound with a necktie. It was called This Shitty Town. I did away with the title; I told them it was untitled. With a title like This Shitty Town I knew he would never get the prize. That was In Evil Hour.

JUANCHO JINETE: Then he won a prize in Venezuela, the Romulo Gallegos. He came to receive the prize and the news came out in the paper that he had given the award money to the revolution.

ALBERTO ZAPALETA: I’m a very good friend of the town where García Márquez was born. I got to know the house where he was born very well—it was covered by vines and the patio was full of weeds; there was half a façade in front. Then I found out through El Espectador that García Márquez had won the Romulo Gallegos Prize in literature for the amount of one hundred thousand dollars and that he had given it as a gift to political prisoners. Then he won another prize and he gave that money to some prisoners. However, he had seen the condition of the house where he was born was in; it was dilapidated—not to mention the town, which was in need of an aqueduct and a school. And there he was, giving the money to other people. So I wrote this song:

The writer García Márquez

He has to be made to know

That we have to love the land

Where one is born

And not dolike he did

He abandoned his hometown

Allowing the collapse

Of the house where he was born.

I ran into him in Valledupar and he greeted me and told me that my song was very good. He told me that he was upset for three months that the song had been so popular.

IMPERIA DACONTE DE MARCELES: He’s never been back to Aracataca. He showed up one night at midnight, in a car with tinted windows, and drove around the town with some friends, but he’s never gone back to Aracataca. With all he’s achieved, he’s done nothing for Aracataca.

Silvana Paternostro is a journalist who has written extensively on Cuba and Central and South America. She is the author of In the Land of God and Man: Confronting Our Sexual Culture and My Colombian War: A Journey Through the Country I Left Behind.

The Cosmonaut Survival Kit, and Other News

Почтовая марка СССР, 1980. Интеркосмос

Have booksellers discovered Shakespeare’s annotated dictionary?

Laura Ingalls Wilder collaborated with her daughter on many books in the Little House on the Prairie series, and it wasn’t always a cooperative arrangement. A letter from 1938 suggests the scope of their creative frictions: “Here you have a young girl,” Wilder’s daughter wrote to her about one character, “a girl twelve years old, who’s led a rather isolated life with father, mother, sisters in the country, and you can not have her suddenly acting like a slum child who has protected her virginity from street gangs since she was seven or eight.”

What was in your average Soviet cosmonaut’s survival kit circa 1968? Among other specialties: three balaclavas, a tripartite rifle/shotgun/flare-gun, and a pistol intended to frighten “wolves, bears, tigers, etc.” in the event of a crash landing.

A new app called Cloak helps you “avoid exes, co-workers, that guy who likes to stop and chat—anyone you’d rather not run into.” Which makes life a bit more miserable, it turns out: “‘All Clear: There’s nobody nearby’ reads like such a strange, sad message, such a lonely thing to have achieved through technological control of our social environments. Looking at that screen makes me want to place my phone face down on my desk, go out into the street, and walk around until I bump into someone I know.”

Christian Montenegro, an Argentinean illustrator, makes arresting drawings that look like eclectic contemporary woodcuts.

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers