The Paris Review's Blog, page 710

April 30, 2014

Playscale

Detail from the cover of From the Mixed-Up Files of Mrs. Basil E. Frankweiler

If you get the chance before September 7, make a point of checking out the New York Public Library’s exhibit “The ABC of It: Why Children’s Books Matter.” Even if you need no convincing on this score, you’ll love it: the exhibit is divided into a series of roughly chronological sub-categories—“Artistry of the Picture Book,” “From Page to Stage”—and illustrated with a wealth of amazing original sketches and manuscripts from iconic children’s books. Then there are the artifacts; you can see P. L. Travers’s parrot-head umbrella, and the original Winnie the Pooh stuffed bear, surrounded by his menagerie of equally well-worn friends.

If you are someone who loves children’s books, you may find yourself overwhelmed by the onslaught of Proustian reveries the show inspires. It feels a bit the way psychics say hospitals and graveyards feel to them—too many memories and associations and forgotten feelings clamoring to be heard at once. Certainly you will have to leave and come back.

I am sure I am not the only one who was especially riveted by one section in particular, on the children’s books of New York. There they all are: The Snowy Day, of course, and In the Night Kitchen, and The House on East 88th Street. (That’s the first Lyle Crocodile book.) And then there are the chapter books. Stuart Little, All-of-a-Kind Family, Roller Skates.

They had first editions of Harriet the Spy (1964) and From the Mixed-Up Files of Mrs. Basil E. Frankweiler (1967.) It had never occurred to me that they had come out in such relatively quick succession—closely enough that one child might have read both on publication—or that, along with 1957’s The World of Henry Orient and maybe even Eloise, they formed a sort of subgenre of their own: the golden age of the Urban Child.

Everyone has read Louise Fitzhugh’s story of the independent-minded girl-spy who spends her days recording impressions of her uptown world, and the E.L. Koningsburg classic of two children who run away and live in the Metropolitan Museum. Henry Orient is probably better remembered these days as the inspiration for the 1964 Peter Sellers film. But like the other two, it chronicles the exploits of independent girls in Manhattan. As in the others, the girls are rich. They attend Brearley. Their parents are largely absent. Like Eloise and Harriet, they are raised primarily by nannies—a sort of mid-century take on the classic orphan narrative.

All these characters are complex, somewhat insolent, defiant, desperate for attention and love, and very much a product of their times. Theirs are inner lives created in reaction to the strictures that surround them. Their parents’ world is ruled by convention; the same privilege that creates their loneliness allows for the freedom of adventures. Heirs to Holden Caulfield? Probably—or maybe even Phoebe Caulfield. Within ten years, their parents’ society would have changed completely—and today both the freedom and the benign neglect that characterize the girls’ lives is as exotic as it is oddly appealing. The other thing that’s noteworthy about all these books is that, from a modern vantage point, we see the protagonists being screwed up before our eyes, and they don’t know it. Will these characters be okay? Not necessarily. Eloise, however, might have some good times with a few of her husbands.

Ditching Dickensian

Giving the lie to a critical crutch.

Illustration: Robert Ingpen

Copies of Donna Tartt’s The Goldfinch now bear an impressive gold foil sticker declaring it the “WINNER of the PULITZER PRIZE.” Before that accolade, though, critics had already branded the novel by using and abusing the adjective that’s launched a thousand blurbs—Dickensian. Despite, or perhaps because of, the ubiquity of the word in appraisals of the novel, such assessments are rarely issued without caveats. NPR’s Maureen Corrigan apologetically notes that the term “is one of those literary modifiers that’s overused”; in the New York Times Book Review, Stephen King somewhat ruefully acknowledged that he wouldn’t be the last to employ Dickensian to describe Tartt’s novel. He was right.

For all this critical concurrence, it’s less than clear what we mean by Dickensian, or, for that matter, by any adjective with a particular author at its root. Francine Prose leads her review of The Goldfinch with this very question: “What do people mean when they call a novel ‘Dickensian’?” As Prose notes, a number of answers present themselves—Dickensian can signify sentimentality, an attentiveness to the social conditions, a cast of comically hyperbolic characters, a reliance on plot contrivances, or even simply a book’s sheer length. (I suspect one rarely means the relatively slim A Tale of Two Cities or Hard Times when one labels a novel Dickensian.) In other words, the proliferation of the senses of Dickensian makes one wonder if it, or other such words, are critically useful at all. As Cynthia Ozick has recently complained with regard to Kafkaesque—another perennial—the word “has by now escaped the body of work it is meant to evoke.”

Dickensian and its variations have been with us since at least 1856, when the OED identified the Saturday Review as referring to a “Dickensian description of an execution.” Variants of the term blossomed throughout the nineteenth century: Dickenesque, Dickensy, Dickensish, Dickeny. And their uses, unsurprisingly, run the gamut. Sometimes they indicate a certain comic sensibility; sometimes they refer to sordid working conditions, or to grotesque characterizations, or to acuity of social observation. And the implications of such words were not always positive or even value-neutral: the novelist Elizabeth Gaskell laments that a story of hers is to be published in a “new Dickensy periodical.” But if these senses of the Dickensian often ran counter to one another, they came, at least, at a time before Dickens had been fully packaged into an available cultural touchstone, when his reputation had yet to be established critically and in language itself.

Of course, we confer a special kind of canonical status when we adjectivize an author’s name. It’s an acknowledgment that his or her work has broadened the collective cultural imagination to the point where a new way of seeing or describing the world needs to be monumentalized in language. But in time, these coinages inevitably obscure or diminish a writer’s achievement. Regardless of how sophisticated one’s sense of Dickens’s oeuvre might be, the popular use of Dickensian conjures, whether we like it or not, shivering orphans, cloying sentimentality, fortuitous coincidence, and virtue rewarded.

At the same time, and more interestingly, it delimits and cheapens the work of the alleged Dickensian. Donna Tartt does salt The Goldfinch with references to very specific Dickens novels, at which moments she might as well be proleptically writing the headlines of The Goldfinch’s reviews. But to lean on Dickensian is to deflect attention from, for instance, the horrific realism with which Tartt treats the central violent trauma of The Goldfinch, and the fallout of its psychic afterlife. In this specifically, she departs from Dickensian models, which more often than not promise recoveries and prosperity for his formerly unlucky protagonists. Dickensian denies, then, as it must, a certain amount of Tarttness. And isn’t it in part the critic’s job to suss out what that Tarttness might be?

This is not to say there’s no place for comparative claims in reviews. But to title a review “Donna Tartt’s twenty-first-century Dickens” runs the risk of overdetermining a reader’s expectations. When we conflate Tartt’s playful Dickens references with imitative artistic ambition, the so-called “Dickensian” aspects of the novel might command our attention, or weigh on us more heavily than the text wants.

Even if we grant that Dickensian isn’t a particularly productive word—even if we admit it be inimical at some level—what can explain the sense of joy or relief that accompanies many of these reviews, charting Tartt’s Dickensian affinities? Reading over my own cursory list of Dickensian attributes, I’m struck by how directly some of them respond to contemporary questions of both reading and culture more broadly. To those fretting over the supposedly stultifying effects of digital media, a Dickensian novel promises to repay sustained, readerly attention—promises to help us rediscover the joys inherent in narrative, the joys supposedly known to nineteenth-century readers. To those concerned with the insularity of literary culture, anything Dickensian is an invitation to a broader, more demotic readership. To those irritated by the preponderance of detached, ironic, sensibilities, Dickensian works augur the return of unabashed sentiment, or at least of sincerity. And to those alarmed at American socioeconomic conditions, so often compared to those of the Industrial Revolution, Dickensian gestures toward a more socially alert, inclusive fiction—witness The Wire, which was so often saddled with the descriptor that the show ran an episode called “The Dickensian Aspect.”

And the Dickensian has recently gained currency among New Yorkers in particular, as Mayor Bill de Blasio repurposed the notion of “a tale of two cities” to describe socioeconomic disparity. (The willful slipperiness of this appropriation speaks to the vagueness of Dickensian in and of itself—what were those “two cities” again?) De Blasio’s office doubled down on Dickens at the recent mayoral inauguration, where Harry Belafonte decried New York’s “Dickensian justice system”—and de Blasio, in keeping with his “two cities” theme, chose Lorde’s “Royals” as his campaign anthem, a song the New York Times was quick to label—guess?—a “Dickensian anthem.”

But the adjective’s life as a social lament is distinct from its ebullient employment by critics. Even if we don’t want a Dickensian New York or a Dickensian America, it seems there’s still a hunger for Dickensian fiction: an unvoiced or unrealized yearning for the literary Dickensian. We’re delighted at the opportunity to bestow the word on any fat new novel that bears even trace elements of Dickens’s heritage. Maybe Dickensian speaks more about a longing in our literary culture, in other words, than about the aesthetic qualities of a particular novel. But why do this at the expense of the very novels fulfilling that longing? The best way to liberate the Dickensian—and the truest way to see it in other works—is to disavow the word entirely.

Matthew Sherrill is a Ph.D. candidate in English literature at Rutgers University, where he is completing a dissertation on British poetry and the history of evolution. He studiously avoids Byronic and Keatsian, even as he sometimes lets slip a Wordsworthian.

On Epitaphic Fictions: Primo Levi

The final entry i n our three-part series on writers’ epitaphs. Read yesterday’s installment here, and Monday’s here.

Primo Levi’s grave, in Turin.

The poet and memoirist Primo Levi was buried in Turin in 1987. According to a notice printed in the New York Times shortly after his funeral, “His grave was marked with a simple marble headstone giving his name and the dates of his birth and death.” At some later date, a sequence of six numbers was carved into the stone in the space below his name, the same sequence that had been tattooed on Levi’s left arm upon his arrival at Auschwitz.

I have not been able to discover whether or not Levi himself had left instructions in his will, or had told family members, that the sequence 174517 should be inscribed on his stone. In her biography of Levi, The Double Bond, Carole Angier explains that the six men who lowered Levi’s coffin into the grave were all concentration or death camp survivors, and that among the mourners who followed the body to the cemetery were scores of Holocaust survivors “wearing neck-scarves marked with the names of their camps.” Could the revision of his stone have been the wish of Levi’s “survivors”? However it was, the sequence is the most striking and original part of his epitaph, and, set against even a bare skeleton of Levi’s life story, its use here offers us redeeming fictions. On the marble face of his headstone, the sequence is a kind of postlinguistic, numerical poem.

Levi wrote that his experiences in Auschwitz made him a writer. The implication is that his transformation into a writer began with his being written upon. If this is true—if Levi really would not have written if he had been given a different life—then his poems in particular would seem to trump Theodor Adorno’s edict that “To write poetry after Auschwitz is barbaric. And this corrodes even the knowledge of why it has become impossible to write poetry today.”

When Levi extended—or was forced to extend—the blank page of his left forearm, the gesture expressed the gradual erasure of his identity begun months before, according to protocols such as a proscription from appearing in public without wearing a yellow star, an eviction from a home, the loss of employment, the commandeering and looting of personal property, the restriction of physical movement and freedom of association. Piercing and inking of his skin with a tracking number—174517—was a first draft but also a final draft: those numbers would last for his life’s limited forever. The tattoo was also a revision: it altered an individual human being, a Jewish man, once a citizen of occupied Italy, into an item on its way toward disposal. Levi was “Primo,” the first, numero uno, and then he was 174517. Yet the deliberate revision of Levi’s headstone after his burial both recapitulates and undoes the Nazis’ attempt to revise a man into a thing.

When Levi extended—or was forced to extend—the blank page of his left forearm, the gesture expressed the gradual erasure of his identity begun months before, according to protocols such as a proscription from appearing in public without wearing a yellow star, an eviction from a home, the loss of employment, the commandeering and looting of personal property, the restriction of physical movement and freedom of association. Piercing and inking of his skin with a tracking number—174517—was a first draft but also a final draft: those numbers would last for his life’s limited forever. The tattoo was also a revision: it altered an individual human being, a Jewish man, once a citizen of occupied Italy, into an item on its way toward disposal. Levi was “Primo,” the first, numero uno, and then he was 174517. Yet the deliberate revision of Levi’s headstone after his burial both recapitulates and undoes the Nazis’ attempt to revise a man into a thing.

In marble rather than skin, the inscription of this sequence 174517—which now keeps track of nothing, and supplements rather than replaces his name—is an astonishing act of appropriation. Below his name and literally over his dead body, the numbers now flaunt Levi’s survival. This epitaph says, Nobody burned the body that lies beneath this stone.

Levi had published a poem titled “Epitaph,” in the voice of a fictional “Micca the partisan.” Having been “discarded for a not unserious crime,” Micca speaks from the earth where he had been buried “by my tearless companions.” But Levi’s fictional partisan addresses no grandee on a horse; “Epitaph” is addressed to an ordinary “passerby,” and not so much reader as auditor:

Passerby, I don’t ask you or others for forgiveness,

Or for prayers or tears or particular memory.

I ask only one thing: that this peace of mine will last,

Without new blood, filtering through the clods,

Penetrating down to me with its deadly warmth,

Waking to new sorrow these bones already now made stone.

(translated from the Italian by Harry Thomas and Marco Sognoni)

Primo Levi

Yeats’s vision of a reader mounted on horseback is self-aggrandizing, and his admonishments are oddly dismissive. By contrast, Levi’s Micca is respectful, solicitous even, and honest if vague about his betrayal of his countrymen. He’s in no mood to bark imperatives. But Micca’s request that no more blood flow over this particular ground is even more idealizing than Yeats’s commands. The critic George Jochnowitz writes of Levi, “[He] believed in facts. His commitment to reality was linked in his mind to his opposition to fascist theory.” And yet his poem “Epitaph” offers us not facts, but exorbitant fictions: the cold ground speaks, exhorting warm flesh and bones to stop spilling blood where it is not wanted.

This fiction strikes me as the opposite of barbaric—but then, the word barbarian is a kind of fiction, too. The really scary people are civilized. And one of the ways we know they are civilized is that they make things up about death.

Ah, Bless, and Other News

Heinrich Zille, Die Witwe, 1929.

The winners of this year’s Best Translated Book Awards: in fiction, László Krasznahorkai’s Seiobo There Below, translated from the Hungarian by Ottilie Mulzet; in poetry, Elisa Biagini’s The Guest in the Wood, translated from the Italian by Diana Thow, Sarah Stickney, and Eugene Ostashevsky.

Jenny Diski, bless her, on aging, or something like it: “I must accept that I was old because my hairdresser says, ‘Ah, bless,’ in response to whatever I say in answer to her questions. ‘Are you busy today?’ ‘Just regular working.’ ‘Ah, bless.’ ‘How was the weekend?’ ‘A friend came to stay.’ ‘Ah, bless.’ The other day, when she asked, I said: ‘I’m being interviewed by a journalist from Poland.’ ‘Ah, bless.’ … The ah-bless alters or confirms whatever it’s responding to, and in my mind’s eye (altered and confirmed) I see a small, nondescript old lady going bravely about her business. There are other signs that I am no longer young, but the ah-bless is the most open and public.”

In 1968, Charles Simic witnessed a group of disgruntled poets settle things the old-fashioned way—with fisticuffs. “I stood on the porch watching in astonishment with the Chilean poet Nicanor Parra and the French poet Eugène Guillevic. They were delighted by the spectacle and assumed that this is how American poets always settled their literary quarrels; I tried to tell them that this was the first time I had seen anything like that and it scared the hell out of me, but they just laughed.”

A series of photos compares public spaces in North and South Korea. (The shot of the Pyongyang Metro is especially poignant.)

Guillaume Nicloux discusses his new film, The Kidnapping of Michel Houellebecq, starring, yes, Michel Houellebecq: “He is also really annoying to the captors. He is always asking for wine and cigarettes, he asks for another visit from the prostitute, he is really tiresome for them. He gets angry. He begs our sympathy, but at the same time he behaves really badly.”

April 29, 2014

Going, Going …

May 1 is the last day to apply for our writer’s residency at the Standard East Village, in downtown Manhattan. As our Writer-in-Residence, you’ll get a room at the hotel for three weeks’ uninterrupted work. The residency runs for the first three weeks in July; applicants must have a book under contract. The applications will be judged by the editors of The Paris Review and Standard Culture, and you can find all the details here. But hurry!

Anthony Trollope, Postman Detective

This man could ride like the wind. A cartoon portrait of Anthony Trollope by Frederick Waddy, 1872.

Anthony Trollope’s novels made him a household name in Victorian England. But reliable sources have told the Daily that Trollope was more than a top-rate writer: he was also an extraordinary postal worker.

Anthony’s older brother, Thomas Adolphus Trollope, has the inside poop. The elder Trollope, born today in 1810, wrote a memoir called What I Remember. (It ran to three volumes, suggesting he was not an amnesiac.) The first volume finds him recounting the daring exploits of his younger brother, who, in his days as a courier, once took justice into his own hands:

He had visited the office of a certain postmaster in the southwest of Ireland … and had observed him in the course of his interview carefully lock a large desk in the office. Two days afterwards there came from headquarters an urgent inquiry about a lost letter, the contents of which were of considerable value … There was no conveyance to the place where my brother determined his first investigations should be made till the following morning. But it did not suit him to wait for that, so he hired a horse, and, riding hard, knocked up the postmaster whom he had interviewed, as related, a couple of days before, in the small hours. Possibly the demeanour of the man in some degree influenced his further proceedings. Be this as it may, he walked straight into the office, and said, “Open that desk!” The key, he was told, had been lost for some time past. Without another word he smashed the desk with one kick, and—there found the stolen letter!

Yes, neither snow nor rain nor heat nor gloom of night stayed that courier from the swift delivery of honesty and virtue. Even abroad, Trollope was such a fastidious, reliable postman that not even a sore bottom could keep him down, his brother writes:

I have heard from him so many good stories of his official experiences, that I feel myself tolerably competent to write a volume of “Memoirs of a Post Office Surveyor.” But for the present I must content myself with one other of his adventures. He had been sent to South America to arrange some difficulties about postal communication in those parts which our authorities wished to be accomplished in a shorter time than had been previously the practice. There was a certain journey that had to be done by a mounted courier, for which it was insisted that three days were necessary, while my brother was persuaded it could be done in two. He was told that he knew nothing of their roads and their horses, &c. “Well,” said he, “I will ask you to do nothing that I, who know nothing of the country, and can only have such a horse as your post can furnish me, cannot do myself. I will ride with your courier, and then I shall be able to judge." And at daybreak the next morning they started. The brute they gave him to ride was of course selected with a view of making good their case, and the saddle was simply an instrument of torture. He rode through that hot day and kept the courier to his work in a style that rather astonished that official. But at night, when they were to rest for a few hours, Anthony confessed that he was in such a state that he began to think that he should have to throw up the sponge, which would have been dreadful to him. So he ordered two bottles of brandy, poured them into a wash-hand basin, and sat in it. His description of the agonising result was graphic! But the next day, he said, he was able to sit in his saddle without pain, did the journey in the two days, and carried his point.

Hoosier State

Robert Indiana’s LOVE sculpture, on the corner of Sixth Avenue and Fifty-Fifth Street.

Once, when I was working as a waitress, a mother came into the restaurant with her two little boys, whom we’d seen before. I must say, they were not particularly appealing children—they were wild and hard to control, and frequently cruised around the interior of the restaurant on scooters. On this day, one of them, about four years old, climbed atop an empty table and wouldn’t get down.

I said, “Honey, you have to come down from there.”

To which he said, “Fuck you!”

So I lifted him down bodily.

He ran to his mother in tears, screaming and whining. His mother said, “Sweetheart, the lady only did that because she loves you.”

Yesterday, I had lunch with a friend at one of my favorite restaurants, in West Midtown. It’s an inexpensive French bistro that has been around since 1973; you know when you pass the Robert Indiana LOVE sculpture that you’re almost there. The proprietors treat their regulars—many of them older, many of them eating alone at the small tables—with unsentimental respect and courtesy. When one of the regulars is housebound, they pay the homeless man who panhandles outside to bring food to his or her apartment. That’s not why I go there—I just like the food.

Yesterday, my friend and I both needed comfort. We were in Midtown and we craved croque monsieurs. Our destination was obvious. And when I passed the giant LOVE on the corner of Sixth Avenue, my heart sang.

Writing about that famous Robert Indiana, Megan Wilde said, “The word love was connected to [Indiana’s] childhood experiences attending a Christian Science church, where the only decoration was the wall inscription God is Love. The colors were an homage to his father, who worked at a Phillips 66 gas station during the Depression.” As Indiana himself said, “My goal is that LOVE should cover the world.” He got that wish, sort of.

The restaurant’s proprietors are sort of brusque. Yes, the sometimes-delivery-man takes his meals there, but there is nothing coddling about the experience. Do I “love” this restaurant? I don’t know; it so obviously doesn’t try to be loved that the word seems besides the point. Do I “love” that iconic sculpture? A little bit, maybe, despite myself, only because I know I am about to experience the luxury of taking a place that is nourishing and undemanding and everyday for granted.

When that little boy climbed back onto that table, and fell off, and banged his elbow, and cried, I wasn’t happy. This is the human instinct, I guess: care and tenderness for the dependent is innate. But did I love him? Most certainly not.

The Message in the Meaningless

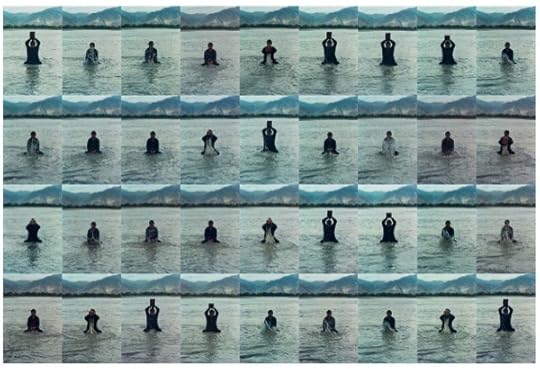

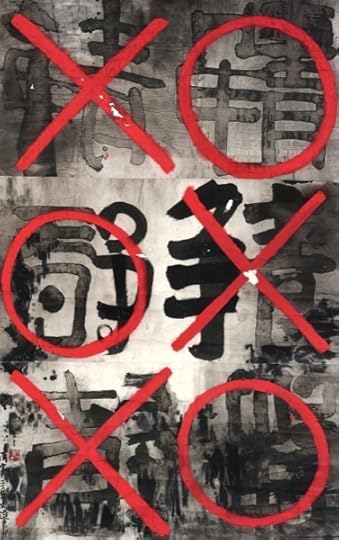

Zhang Huan, Family Tree,

2001, nine chromogenic prints. Photo: © Yale University Art Gallery.

Song Dong, Printing on Water (Performance in the Lhasa River, Tibet),

1996, thirty-six chromogenic prints. Photo: Eugenia Burnett Tinsley.

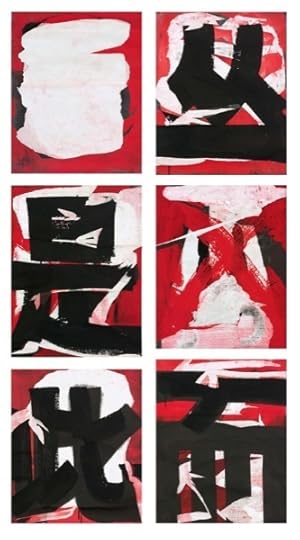

Wu Shanzhuan,Character Image of Black Character Font, 1989, six unmounted sheets; ink and color on paper image. Photo: Courtesy of the artist.

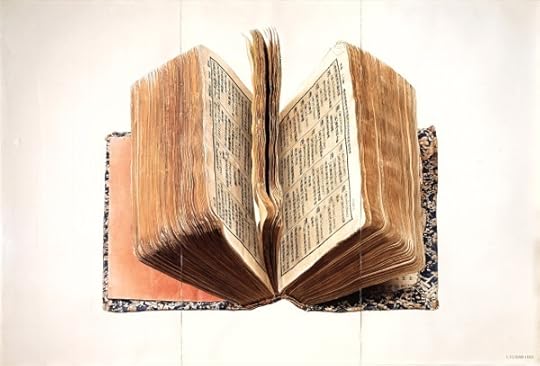

Liu Dan, Dictionary, 1991, ink and watercolor on paper. Photo: courtesy of Sotheby's.

Gu Wenda, Mythos of Lost Dynasties Series—I Evaluate Characters Written by Three Men and Three Women, 1985, hanging scroll; ink on paper. Photo: Courtesy of the artist.

Cai Guo-Qiang,Project to Extend the Great Wall of China by 10,000 Meters: Project for Extraterrestrials No. 10, 1990, accordion album of twenty-four leaves; ink and gunpowder burn marks on paper. Photo: Courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Wang Dongling, Being Open and Empty, 2005, hanging scroll; ink on paper. Photo: Courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Ai Weiwei,

Stool, ca. 2007. Photo: Courtesy of the artist.

Zhang Jianjun, Scholar Rock (The Mirage Garden), 2008, Silicone rubber. Photo: Courtesy of the artist.

Late last year, the Metropolitan Museum of Art unveiled “Ink Art: Past as Present in Contemporary China,” the institution’s first survey of contemporary art from the country. Situated within the museum’s Chinese art galleries, the exhibition interspersed the old with the new, adding context—or, perhaps, simply conserving space. In the permanent Ming Scholar’s retreat, an aubergine rubber scholar rock by Zhang Jianun cast a long shadow over its limestone brethren, while unusable furnishings by the artist-activist Ai Weiwei—a wobbly stool constructed like craniopagus twins, and a table folded at the middle so its four legs have become two legs and two arms—seemed poised to animate and wander away from their sixteenth-century predecessors. Resistance to tradition is a prominent theme in Ink Art, as is the importance of writing in—subtext, of course—a country with an active policy of censorship.

The exhibition looked at the evolution of China’s calligraphic traditions, but its most powerful statement came with works that play on an idea of language, rather than on actual words. Song Dong’s 1996 performance Printing on Water (Performance in the Lhasa River, Tibet), in which the artist futilely stamped the water’s surface with a large wooden seal, alludes to the hopelessness the act of writing can evoke, particularly if it leaves no trace. The final two works in “Ink Art” are also concerned with meaningless writing—but they combined to create a more comforting message. Xu Bing’s installation Book from the Sky filled the last room with scrolls covered in block-printed Chinese characters. The text cascaded in soft arcs across the ceiling, wallpapering the room and coming to rest in neat piles on the floor. The careful organization evokes a calm—which is abruptly displaced when one learns that the text comprises four thousand nonsense characters. Most Western viewers wouldn’t be able to read the text anyway, but the realization that no one can is transformative. An expanse of gibberish becomes an inhabitable space of words: the viewer is absolved from the act of reading.

For anyone who has engaged in the struggle of communicating through writing—namely, every literate person—the idea of writing for its own sake, rather than for meaning, is incredibly alluring. This isn’t an anti-intellectual position; the creation of a nonsensical non-language consisting of thousands of characters is surely a Herculean task of perseverance and ingenuity. Consider Xu Bing’s Book from the Sky as a counterexample to Borges’s Library, where an endless expanse of rooms containing infinite numbers of incomprehensible books led to chaos. For Borges, the search for a message in the mess leads to insanity; for Xu, the lack of message allows for a focus on, and celebration of, writing as a visually aesthetic art form.

The final work in the exhibition, Cai Guo-Qiang’s Project to Extend the Great Wall of China by 10,000 Meters, took meaningless writing to incendiary levels. In 1993, Cai and a team of volunteers laid a ten-kilometer fuse leading from the edge of the Great Wall to the Gobi Desert and lit it from one end, videotaping the process and the results. The explosion was visible from outer space. As the charge traveled, sparks and smoke lit up the night sky, painting a line like brushwork across the terrain. The sound—like the hiss of cymbal vibrations punctuated by tympanic explosions—echoed on the plains, bouncing off the crevices of the earth. Though Project to Extend’s ambitions are predominantly architectural, when paired with Book from the Sky it becomes a monumental act of writing. Like Book, there is no literal message, yet if Book is a celebration of writing’s visual form, Project exults in its action. The traveling charge, moving with the swiftness of a pen or brush, creates the eloquent impression of writing: full of drama, force, destruction, and creation.

Lilly Lampe is a writer and art critic based in Brooklyn. Her writing has appeared in Art in America, ArtAsiaPacific, Art Papers, Artforum.com, and Modern Painters, among others.

On Epitaphic Fictions: Robert Louis Stevenson, Philip Larkin

John Singer Sargent, Portrait of Robert Louis Stevenson, 1887

There is very little that’s puzzling about Philip Larkin’s two-penny upright “This Be the Verse” (1971):

They fuck you up, your mum and dad.

They may not mean to, but they do.

They fill you with the faults they had

And add some extra, just for you.

But they were fucked up in their turn

By fools in old-style hats and coats,

Who half the time were soppy-stern

And half at one another’s throats.

Man hands on misery to man.

It deepens like a coastal shelf.

Get out as early as you can.

And don’t have any kids yourself.

“This Be the Verse” is arguably the best-loved English poem of the last half of the twentieth century. Funny, frank, transgressive—human—the poem has stood up admirably in pub, alley, and classroom. (Of how many humans with fancy titles can this be said?) But what about that awkward title? How did a writer as good as Larkin fuck up his forms of to be?

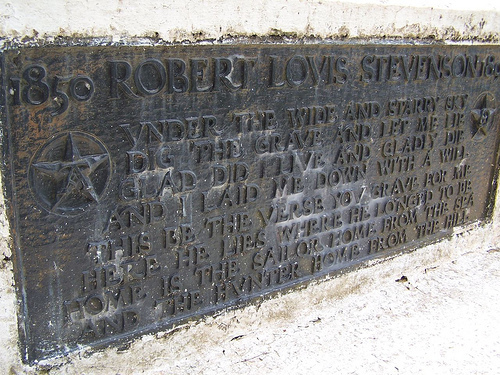

The title’s oddness is no empty gesture. The words “This Be the Verse” point us toward one of the sweetest, un-Larkin-esque poems in the language, Robert Louis Stevenson’s self-composed epitaph. When it’s published in an anthology, it usually appears as two stanzas called “Requiem,” but on Stevenson’s tomb, the epitaph is presented as a single block under his name and dates, without punctuation or title:

Under the wide and starry sky,

Dig the grave and let me lie,

Glad did I live and gladly die,

And I laid me down with a will.

This be the verse you grave for me:

Here he lies where he longed to be,

Home is the sailor, home from sea,

And the hunter home from the hill.

“Requiem” offers us several moving fictions. The principal inducer of make-believe here is the utter smoothness and rhythmic consistency of the poem. (That second “the” on line seven is a plaque-maker’s error.) The sounds this text makes—one almost bursts into song reciting it—correspond to conventional notions of what it meant to write beautiful English verse in the late-nineteenth century.

But Stevenson suffered from tuberculosis, and the beauty here evinces a tubercular’s desire for a calm and musical passing, his wish to skip the bits of lung hacked up in the back of the throat, the blood-spattered kerchiefs and pillowcases. The most striking fiction in the first stanza, perhaps, is the fiction that one is as glad to die as one has been to live. Line three—with its mellifluous repetition of all the sounds that occur in “glad did I live” in the phrase “gladly die”—doubles down on this fiction, which is backed up by the punning end of line four, where “will” sounds out Stevenson’s sense that these lines are his final testament, a strong-willed, perhaps even willful, presentation of his legacy. See how the word “grave,” which arrives in line two as a noun, reappears, in line five, as a verb? Stevenson’s epitaph transforms a hole in the ground into an active making.

Stevenson’s fight with tuberculosis was more retreat than attack. A Scot, born in Edinburgh, he wrote beautifully from many places in whose climates he sought relief from the symptoms of his disease: Dorset, Davos, coastal California, Hyères, the Adirondacks, Hawaii, New Zealand. He died and was buried in Samoa, about 9460 miles from his birthplace, so Google tells me. In light of that fact, few lines pluck at one’s heartstrings so strongly as the sentimental fiction, “Home is the sailor, home from sea / And the hunter home from the hill.” Even on his own tomb, Stevenson tells us the story we want to hear regarding our own eventual resting places, though he must lie so far from home.

Larkin’s use of Stevenson’s words hides the epitaphic frame of “This Be the Verse” in plain sight. (I have found, on a long-disused thread, a famous poet’s admission of how even she, in the days before the Internet, had for nearly a decade never bothered to look up the reference.) His use of the phrase indicates that Larkin’s speaker, too, is concerned about what somebody will “grave” on his headstone, which, like Ben Franklin’s headstone, is only a notion—it doesn’t yet exist, and won’t for some time. (Larkin’s actual headstone would end up bearing no epitaph.)

Photo: Keith D, via Wikimedia Commons

The fictions in Stevenson’s “Requiem” are generous, if sentimental. Are the fictions of “This Be the Verse” as generous? I think so. Their generosity derives in part from Larkin’s inversion of Stevenson’s sentimentality, and in part from his dipping the speaker’s instructions in irony. Larkin tacitly invites us to imagine coming upon “They fuck you up, your mum and dad” on a headstone, under anybody’s name, two dates, and a hyphen. (The hyphen is itself a moving figure, so compact is the rectangular mark that stands for a life.) Our laughter at “This Be the Verse” expresses our surprise at finding such inappropriate diction carved in a so upright a font, and taking so stern a posture.

Larkin’s poem places his speaker in a continuous series of generations, each human member of which may live for only a hyphen’s length—but that’s long enough to realize that human misery is general, that our discrete pain and suffering is part of something greater. The command that follows the only vivid image in the poem—misery deepening “like a coastal shelf”—is a non sequitur. “Get out as early as you can.” We can hardly follow it any more than we could follow Yeats’s imperative, “Horseman, pass by.” Misery loves company, but in our experience of “This Be the Verse,” the misery is only fiction. The laughter we share when we read Larkin’s imagined epitaph is real.

Daniel Bosch is Senior Editor at Berfrois . His sonnet sequence “To a Barista” is at The Common ; his meditation on race and invocation will appear later this week at The Morning News .

Searching for Cervantes, and Other News

We’re going to find this man—with radar. Juan de Jauregui y Aguilar, Miguel de Cervantes, seventeenth century.

In Spain, forensic scientists have begun to search for the remains of Miguel de Cervantes—using the power of radar.

Dave Eggers wrote a rhapsodic introduction to the tenth-anniversary edition of Infinite Jest. But in 1996, when the novel was first published, he had less enthusiastic things to say. (The phrase “wildly tangential flights of lexical diarrhea” is especially damning.)

If we blame Helen of Troy for starting the Trojan War, are we not slut-shaming?

In China, the Uighur writer and scholar Ilham Tohti “has been charged with separatism for the peaceful expression of his views on human rights.” A long list of writers has signed a petition demanding his release.

Have you been searching for the proper periodical for the young arriviste in your life? “Teen Tatler knows what its readers are destined for: a cokey phase where they fuck a member of a dynasty pop-rock band, before a lifetime of medicated bliss on the arm of some kind of viscount.” Subscribe now.

Let’s remember our nation’s historic first sperm bank—it all started in the Iowa of 1952, with two doctors, some bull semen, and a lot of dreams…

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers