The Paris Review's Blog, page 706

May 12, 2014

The Birth (and Death) of Edward Lear

You’d think it would be easy to invent nonsense words. After all, the real lexical bummer is usually the burden of definition: your average neologism has to mean something. Nonsense words, on the other hand, are not merely devoid of but entirely divorced from meaning—creating them should just be a matter of aesthetics. Throw a couple consonants together, make sure there’s a vowel in there someplace: voila. And yet—

Hlerkjer—not a very good nonsense word.

Grimblurp—better, but still aesthetically lacking…

Runcible—now, that’s quality nonsense.

Runcible is a creation of Edward Lear’s, arguably his pièce de résistance—though it faces stiff competition from the likes of tilly-loo, Yonghy-Bonghy-Bò, tiniskoop, cheerious, chuprassies, meloobious, gromboolian, mumbian, bruffled, dolomphious, borascible, fizzgiggious, himmeltanious, tumble-dum-down, spongetaneous, and blatter-platter. Lear, born today in 1812, was a prolific painter and illustrator, but the poem—especially the limerick—is where he really left his mark. In such volumes as The Book of Nonsense; More Nonsense Songs, Pictures, Etc.; Nonsense Botany; The Quangle-Wangle’s Hat; and Scroobious Pip, he cultivated an ear for twaddle, malarkey, and piffle that remains largely unrivaled in letters to this day. His nonsense words have a certain authority to them, so much so that one feels compelled to define them—and on the tongue they have an inimitable springiness, an Anglo-Saxon lilt. When Lear’s characters aren’t named after nonsense or spouting it, they tend to be pursuing it in some form or another, as they do here, in the first stanza of “The Jumblies”:

Runcible is a creation of Edward Lear’s, arguably his pièce de résistance—though it faces stiff competition from the likes of tilly-loo, Yonghy-Bonghy-Bò, tiniskoop, cheerious, chuprassies, meloobious, gromboolian, mumbian, bruffled, dolomphious, borascible, fizzgiggious, himmeltanious, tumble-dum-down, spongetaneous, and blatter-platter. Lear, born today in 1812, was a prolific painter and illustrator, but the poem—especially the limerick—is where he really left his mark. In such volumes as The Book of Nonsense; More Nonsense Songs, Pictures, Etc.; Nonsense Botany; The Quangle-Wangle’s Hat; and Scroobious Pip, he cultivated an ear for twaddle, malarkey, and piffle that remains largely unrivaled in letters to this day. His nonsense words have a certain authority to them, so much so that one feels compelled to define them—and on the tongue they have an inimitable springiness, an Anglo-Saxon lilt. When Lear’s characters aren’t named after nonsense or spouting it, they tend to be pursuing it in some form or another, as they do here, in the first stanza of “The Jumblies”:

They went to sea in a Sieve, they did,

In a Sieve they went to sea:

In spite of all their friends could say,

On a winter’s morn, on a stormy day,

In a Sieve they went to sea!

And when the Sieve turned round and round,

And everyone cried, “You’ll all be drowned!”

They cried aloud, “Our Sieve ain’t big,

But we don’t care a button, we don’t care a fig!

In a Sieve we’ll go to sea!”

Far and few, far and few,

Are the lands where the Jumblies live;

Their heads are green, and their hands are blue,

And they went to sea in a Sieve.

If Aesop had written his fables on a steady regimen of opiates, they might have turned out like Lear’s poems.

I came to Lear not through runcible—which remains, especially when paired with spoon, a vital part of the popular imagination—but by way of “The Death of Edward Lear,” a 1971 short story by Donald Barthelme in which Lear invites his friends and associates to join him at his deathbed. (He puts on quite a show, in one sense, and not much of a show at all, in another.) Barthelme, of course, was a purveyor of his own grade-A nonsense; you can read “The Death of Edward Lear” as a sort of winking memorial, even if it lacks for limericks. As is often the case with a Barthelme story, its humor begins to accrue a sense of sadness, an existential weight, as it goes on:

People who attended the death of Edward Lear agreed that, all in all, it had been a somewhat tedious performance. Why had he seen fit to read the same old verses, sing again the familiar songs, show the well-known pictures, run through his repertoire once more? Why invitations? Then something was understood: that Mr. Lear had been doing what he had always done and therefore, not doing anything extraordinary. Mr. Lear had transformed the extraordinary into its opposite. He had, in point of fact, created a gentle, genial misunderstanding.

Thus the guests began, as time passed, to regard the affair in an historical light. They told their friends about it, reenacted parts of it for their children and grandchildren. They would reproduce the way the old man had piped "I've no money!" in a comical voice, and quote his odd remarks about marrying. The death of Edward Lear became so popular, as the time passed, that revivals were staged in every part of the country, with considerable success. The death of Edward Lear can still be seen, in the smaller cities, in versions enriched by learned interpretation, textual emendation, and changing fashion. One modification is curious; no one knows how it came about. The supporting company plays in the traditional way, but Lear himself appears shouting, shaking, vibrant with rage.

Biographies in Bronze, by Fredda Brilliant

From the cover of Biographies in Bronze

I am ashamed to admit that, as recently as one week ago, I’d never heard of Fredda Brilliant. My life was the poorer for it. Born in Poland to a Jewish family in the diamond trade, Brilliant was an actress, novelist, screenwriter, and activist who died in 1999. According to the dust jacket of her 1986 memoir-cum-art-book Biographies in Bronze, “She also composes the music and lyrics for songs which she herself sings at concerts, radio, and TV.”

She was best known, however, as a sculptor and personality. As the Independent related in her obituary,

Nehru once said of Fredda Brilliant that when at work she looked like a mad woman—in day-to-day life she would without restraint sing out loud in public—tears would flow as easily as laughter and anger. She promenaded around the Sussex village of Henfield dressed in long black dresses, tasselled shawl about her shoulders and brilliant headscarf encircling her dark hair and small face—in winter she would wear a fur coat to the knees.

The dust jacket intrigued me, yes, when I came across Biographies in Bronze on the dollar cart at Unnameable Books. But it was not until I actually opened the book—specifically, to the picture of Brilliant’s bust of one Tom Mann—that I knew it must be mine.

Here is the author’s caption:

Tom Mann, an old Communist, who also knew Lenin, was a pioneer Trade Union Organizer. He helped to start trade unions in Australia and China. He became the leader of the Amalgamated Engineering Union.

In 1938, at the age of eighty-four, whenever he came to a sitting, he would bring me a bunch of flowers from his garden, picked by himself. It was very sweet but he didn’t seem to realize they were more weeds than flowers. Whenever I asked him about how he started to organize these trade unions he would always reply: “You can read about that anywhere. But I’ll tell you about Peeping Tom—as the girls called me.”

It’s all like that. Associative, gossipy, curiously flat.

The book contains no fewer than five introductions by notables, including Brilliant’s husband, Herbert Marshall. “With a vision that is objective even as it is compassionate, and vibrant even as it is serene, Fredda Brilliant’s bronzes have become grand forms that tell the stories of their subjects’ inner lives. Hers are great works, reflecting a love for humanity and a passion for art.”

Brilliant did manage to attract a pretty amazing roster of sitters, from Gandhi to JFK. However varied the accomplishments of her subjects, they are, in her telling, almost uniformly moved to tears by her portraits of them. Emotions in her studio could run dangerously high—as when a pair of artists from the Georgian republic watched her model “Medusa,” the bust of a female colleague:

The two artists watched as I worked and seeing the results very soon these volatile Georgian artists behaved as if at a football match; they clenched their hands, stamped their feet, raised their voices, shouting:

“Give it to her! Give it to her, that sweet bitch!”

Their egging me on didn’t directly influence my work, however, but it did give me confidence to continue revealing what I saw without inhibitions, without second thoughts.

Of all her anecdotes, perhaps the most memorable involves the sitter whom she calls “Baby Bernstein,” and his mother, Ruby:

Alas, Ruby, had a nose beyond imaginary proportions. The type of nose the Nazis attributed to Jews. Yet her father, a Rabbi, and her mother and sisters had normal features. In spite of her intellect and a pleasant personality, I understood from her mother that the nose was a drawback to her getting married.

I pondered how to approach Ruby. I then took courage and told her to have her nose remodeled. But Ruby found all sorts of nonsensical excuses against it. I then approached her parents, explaining the psychological effect on her and the impact on others. We pressurized her until her nose was in harmony with her face. Shortly after, she married a Bernstein, of the Film and Television family. I was happy and felt inwardly good.

Then Ruby had a son. I was thrilled, and proposed a sculpture of him. The baby was then six weeks old. As I understand it a baby that old has no clearly focused vision. But it was lovely to watch him during breast-feeding —hypnotized, looking into mother’s eyes. A sort of first love! And it was a very succulent baby at that. The nose—beautiful.

Needless to say, I have ordered her next volume, Women in Power.

Recapping Dante: Canto 29, or Don’t Trust the Midas Touch

William Blake, Canto XXIX

We’re recapping the Inferno. Read along! This week: The price you pay for turning stuff into gold.

Having read the incandescent poetry of cantos 26-28, it’s difficult not to feel as though Dante really phoned it in with canto 29. In fact, canto 28 is so hard to shake that Dante dwells on it for the first thirty or so lines of canto 29, weeping at the thought of the mangled sinners he’d met. Virgil rebukes him for his compassion, as always, and emphasizes the importance of moving on: he tells Dante they’re running out of time to complete their quest, which must have been Dante’s way of upping the stakes. Will our heroes beat the clock?

Virgil also points out that this is the first time Dante has wept for sinners in such a way. Dante has an explanation—he isn’t weeping for all the sinners, but for his cousin, Geri del Bello, who was among those undergoing tortured back in canto 28. Geri was killed but never avenged, and for this Dante weeps. Virgil, ever quick with the quips, suggests that Dante doesn’t really care all that much about his cousin—instead of talking to him when he had the chance, Dante instead decided to chat with Bertran de Born.

As Dante and Virgil proceed over the last bridge of this circle, Dante describes the foul smell of the following ditch—rotting limbs, putrid skin, and all the stench of dead patients in plague-stricken hospitals. It is a powerful image, especially since one can imagine that by now, Dante is very familiar with the smell of rotting body parts. What Dante smells are the falsifiers, the corpse-like shades under punishment for forgery. Dante will speak with the alchemists, who are afflicted with a sort of super-leprosy.

As they cross the ridge and descend among the sinners, Virgil calls to two shades who are propped up against each other and scratching the skin from their own bodies. They are mangled and viciously maimed: think of the face-melting scene from Raiders of the Lost Ark. Virgil asks if any among them are Italians—indeed, these two are. The first sinner is Griffolino D’Arezzo, who was punished for his alchemy but killed for a different reason: he swore to Albero di Siena that he knew how to achieve flight, and when it was revealed that he was lying, Albero had him burned. At that point, Dante turns to Virgil and makes fun of the Sienese by saying they’re even more fatuous than the French. Ouch! I hope health insurance in Hell covers burns.

Another Sienese alchemist, Capocchio, speaks up—he was also burned alive. Capocchio is believed to have been an early acquaintance of Dante’s; the two may have met when they were both students. He speaks with the same sort of dark wisdom and ethereal regret that all the great sinners of the Inferno have mastered—but Capocchio does it in just a few lines, as opposed to, say, Ulysses, who required a whole monologue. Capocchio gives us an abridged version of the classic Inferno sinner’s memoir.

To catch up on our Dante series, click here.

Alexander Aciman is the author of Twitterature. He has written for the New York Times, Tablet, the Wall Street Journal, and TIME. Follow him on Twitter at @acimania.

Endangered Opera

Ferruccio Furlanetto in a publicity still from the San Diego Opera’s Don Quixote.

The half-ton red-velvet curtain fell for what may be the last time on a San Diego Opera performance in mid-April, to a sold-out matinée of Don Quixote. Before the show, patrons drank wine outside, talking about the sad turn of events and snapping photos to mark the occasion: funeral selfies, opera style. In the final minutes of the final performance, Ferruccio Furlanetto—as a lanky and, even by operatic standards, gorgeously expressive Don Quixote—collapsed on a cluster of boulders under a starlit sky, relinquishing his last breath, and with it, his perpetual quest for a better tomorrow.

In March, the Opera’s board of directors voted to fold the forty-nine-year-old company, citing financial problems. After the announcement, which surprised many, came a media storm with all the musical metaphors you could hope for. (Would the fat lady sing? Would there be a reprise?) There were social media campaigns and T-shirts; candlelight vigils; protesters, one in a death mask; a large, last-ditch donation, and a series of smaller contributions from first-time donors; and then there was a genius twist. Someone closely read the opera’s bylaws and discovered that everybody who donated at least $101 toward the current season was considered an association member with voting rights, which meant they could make decisions and recommendations. A second board vote postponed the closure to May 29 and bought some time for fundraising. For the past month and a half, problem solvers have been hunting for ways to keep the San Diego Opera running. Ditch the massive theater? Save the chorus? What is necessary, and what is sufficient, to create opera?

Some would have you believe that San Diego did not, does not, deserve a quality opera company. A few weeks before that final show, I had a drink at the downtown hotel piano bar, with its cream-paneled walls, where I sometimes go with my husband for après-opera cocktails and people watching. Word came around to the opera and why we thought it was folding. Low sales. High costs. Lack of donors. Mismanagement. “But it’s San Diego, too. You know how it is,” said Frank, the bartender, from Cleveland. The old “city of sun-kissed surfer-idiots” argument maintains that San Diego is simply not intellectual enough to sustain an opera.

This is the line that’s muttered by those who wish there were a thicker cultural life here: more bookstores, more challenging public art, a classical-music station that plays more than light hits and movie scores out of Tijuana and one that plays static-corrupted symphonies out of Los Angeles. The news satirist in our city’s alt-weekly, the San Diego Reader, photoshopped this message onto the Civic Theatre’s marquee, where opera names and dates are usually posted:

Good-bye you cretinous sun-addled troglodytes

Enjoy your crappy sports teams and their fancy new venues.

To the satirist, someone commented online: “The Opera isn’t the only ‘arts,’ ‘music’ or ‘culture’ in San Diego. There’s plenty of all three all over the city and the vast majority is self sufficient.” QED.

Another theory: Only New York, Paris, Berlin, and Milan deserve quality operas. For the rest of us, there’s the MOOC model to arts appreciation: via high-definition simulcasts, operas appear in cinemas across America, well within reach of the casual fan. But if you want to sit sixty rows away from someone’s real, live, quivering uvula, pay up and head to a major city. This is the essence of the argument floated by the San Diego Opera’s longtime general manager, Ian Campbell. He didn’t send people to the movie theaters or to New York outright, but he cited fundraising pressures and said grand opera can’t be done anymore, not in this city. “The demand for opera in this city isn’t high enough,” he told the Los Angeles Times. Operas are falling left and right. Orange County. Baltimore. Cleveland. Spokane. New York City. In San Diego, the opera was known to be well run, despite its closure; if even a competently managed opera can’t survive, can we trust our theaters and other arts venues to be viable in the long run? This is a chapter in a longer story, the same story that tells of the merging of language and classics departments into “humanities” departments, the adjunctification of academia, the focus on educational ROI over the intrinsic merits of studying, say, Faulkner. The question becomes not “how can we stop this,” but “which city will lose its opera next?” A headline in the Chicago Business Journal asked: “Could it happen in Chicago?”

A third section of the commentariat contends that San Diego was swindled. It deserves and desires an opera—as proved by the success of its grassroots fundraising and its citizens’ collective refusal to watch the opera go quietly—but greed has prevailed. After the company announced it was closing, reporters uncovered evidence that Campbell and his ex-wife, Ann Spira Campbell, a fundraiser, were receiving robust paychecks, bonuses, and contract terms, even during the economic downturn. Some say his pay and pension are a fair exchange for managing the company successfully for decades. Others see his flush contract as another nail in the coffin, and many people have blamed him in large part for the closure. Campbell refused to consider the possibility of carrying on the opera with diminished production values—the classic “claim artistic integrity to save your cushy retirement package” line. He’s stopped giving interviews, but I’m curious to hear his point of view.

San Diego has been in a similar situation before—in 1996, the symphony here went bankrupt. It was embarrassing. It was tragic for the city’s art lovers. But the symphony found two angel donors, in the form of the tech magnate Irwin Jacobs and his wife Joan, who brought the organization back to life in 2002. They’ve since donated more than $120 million. In its new form, the symphony takes some risks. They recently played with Megadeth’s David Mustaine, and while the combination didn’t sound pleasing, it was a vital step toward introducing people to the symphony and constructively challenging the mission of a metropolitan orchestra.

I remember what this city was like in 1998, two years into that bankruptcy. It was so boring I left. I believe I used to use the word “provincial”—I was that kind of teenager. I moved back from Cambridge in 2008, when I was almost done with grad school and able to submit chapters from afar, because several of life’s arrows pointed that way and I decided to follow them. I arrived to find a city strikingly attuned to culture, with a creative and artistic infrastructure that attracts and holds people’s attention. We have inventive, versatile theaters and classical music ensembles; bookstores, farmers markets, craft beer, bike lanes; and a newspaper that has, despite that industry’s contraction and the consequences thereof, continued to publish criticism and author interviews. I have not been bored a day since I got back.

At Don Quixote, as the curtain fell for what may be the final time—the message “We are not giving up!” burned into the supertitles—some, including me, wiped away tears. I sang with the children’s chorus in high school. I’ve covered the arts here off and on for a decade. For one story, the costume department made me up with a costume, makeup, and a wig. For a different project, I was embedded with them for two weeks, reporting from backstage on the action building up to the opening night of Faust. I talked with the set builders, the singers, the gentleman who raises and lowers that thick velvet curtain. I find it hard to believe the opera can’t be saved. And it’s harder, for me at least, to imagine a San Diego without the San Diego Opera.

If it closes, San Diegans will have to start driving 122 miles to the Los Angeles Opera; several hundred people will lose a significant chunk of income or their full-time jobs; chorus singers and symphony musicians may be forced to relocate, taking their creativity, their passion, their espresso-drinking and rent-paying dollars with them; and the citizens of this city will have one less venue for storytelling and community. San Diego won’t just be a city without an opera. It will be a city with private wealth—with tremendous intellectual and creative capital and a regional population of millions—which once had a great opera and let it slip away.

Roxana Popescu is a writer and journalist based in San Diego. Her articles and criticism have appeared in The New York Times Book Review, Newsweek, The International Herald Tribune, The New York Times, Forbes.com, and elsewhere.

Please Hire Walt Whitman, and Other News

The guy needs a job. Portrait of Whitman by Thomas Eakins, 1887.

In 1847, Charles Dickens founded a “home for homeless women”: he “flung himself into organizing every detail of it, from the food to the flower garden, and the piano around which the women would gather for wholesome evening entertainment … when he learned London society was particularly shocked about the piano, [he] spread a rumor that there would not just be one but many pianos, one for each woman.”

And in 1863, Ralph Waldo Emerson wrote a recommendation letter for Walt Whitman, who sought a government clerkship: “He is known to me as a man of strong original genius, combining, with marked eccentricities, great powers & valuable traits of character: a self-relying large-hearted man, much beloved by his friends; entirely patriotic & benevolent in his theory, tastes, & practice.”

A look at Alt Lit, “an online writing community that emerged in 2011 and harnesses the casual affect and jagged stylistics of social media as the basis of their works … Its members have produced a body of distinctive literature marked by direct speech, expressions of aching desire, and wide-eyed sincerity. (‘language is so cool. i can type out these shapes and you can understand me,’ or ‘Yay! Dolphins are beautiful creatures and will always have a wild spirit. I have been very lucky because I have had the awesome experience of swimming with dolphins twice.’)”

The problem (or at least a problem) with superhero movies: “the visual and rhythmic sameness of the films’ execution … Despite their fleeting moments of specialness, The Avengers, the Iron Man and Thor and Captain America films, the new Spider-Man series and Man of Steel treat viewers not to variations of the same situations … but to variations of the same situations that feel as though they were designed, choreographed, shot, edited and composited by the same second units and special effects houses, using the same software, under the same conditions … Shots of people fighting inside and atop collapsing and burning structures all feel basically the same.”

Misha Defonseca’s 1997 Holocaust memoir, which sold millions of copies in Canada and Europe, is entirely fabricated; a court has ordered Defonseca to return $22.5 million.

May 9, 2014

What We’re Loving: Lovers, Lizards, Lowry

The Jesus Lizard, in a photograph from The Jesus Lizard Book.

I don’t usually go in for collections of letters; it’s hard to imagine sitting down and reading one cover to cover. But I couldn’t resist picking up a volume of love letters between Christopher Isherwood and Don Bachardy, in large part because it’s titled The Animals. It sounded sweetly romantic, and it is. Isherwood, some thirty years older than Bachardy, is Dobbin, an old workhorse; Bachardy is Kitty. Though they discuss all manner of subjects in the body of the letters—dinners, friends, business, and art—they are topped and tailed (no pun intended) with joyful, intimate love: “I feel a need to tell Kitty today how dearly Dobbin loves him and how faithfully he waits and guards the stable until Kitty’s return. Dub has been quite off his feed since Kitty hasn’t been there to tempt him with morsels held by those pure paws.” Bachardy sometimes even includes cutouts of fluffy white kittens in his missives. Apart from the adorableness, there is, of course, other great stuff here: not least, Isherwood’s coining of the word psychofiesta. —Nicole Rudick

“You’re eighty-two years old. You’ve shrunk six centimeters, you only weigh forty-five kilos yet you’re still beautiful, graceful and desirable. We’ve lived together now for fifty-eight years and I love you more than ever. I once more feel a gnawing emptiness in the hollow of my chest that is only filled when your body is pressed next to mine.” That’s the beginning of philosopher André Gorz’s Letter to D, written to his dying wife. A year later, the couple took their own lives, together. The book itself is slim—as the friend who sent it to me wrote, you can read it on the crosstown bus—but it contains a fully realized true love story. —Sadie Stein

Nothing grates like a self-mythologizing coffee-table book, but in the case of the Jesus Lizard’s new book—called, simply, The Jesus Lizard Book—you can forgive any aura of congratulation. These guys deserve to pat themselves on the back. One of the finest, most primal rock bands of the nineties, they drew a cult following in that they seemed to be, in fact, a cult, with David Yow the deranged high priest and David Wm. Sims his brooding voodoo-deacon. If the spectacular photography in The Jesus Lizard Book is to be believed, their shows resembled nothing more than that scene in Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom where some poor dude has his still-beating heart removed in an elaborate ritual. (In the world of the Jesus Lizard, everyone is in the Black Sleep of Kali Ma.) Granted, Yow could be an oblique shock-jock—“I had a tendency to pull my balls out and hold them glistening up to microphone,” he says—but at his best, he was as compelling a frontman and lyricist as anyone in music. The gritty economy he brought to, say, “Karpis”—“Alvin’s feelin’ restless, cellblock H / A carton of smokes for ten minutes of pleasure”—tells an unmistakably terrifying story without having to spell anything out. —Dan Piepenbring

While reading through an interview—blind item!—that’s running in our upcoming issue, I was led by a series of Google searches to a would-be epitaph written by Malcolm Lowry:

Malcolm Lowry

Late of the Bowery

His prose was flowery

And often glowery

He lived, nightly, and drank, daily,

And died playing the ukulele

The “Death by Misadventure” tag in his coroner’s report calls the ukulele bit into question (or does it?)—and Lowry’s actual tombstone, it turns out, isn’t quite so literarily engraved—but the verse did remind me of another of my favorite would-be epitaphs, that of W. C. Fields. When asked by Vanity Fair, in 1925, to contribute to a piece called, fittingly, “A Group of Artists Write Their Own Epitaphs,” he came up with this, a riff on his running (and playful) disdain for the City of Brother Love: “Here lies W. C. Fields. I would rather be living in Philadelphia.” —Stephen Andrew Hiltner

Discovering Mary Ruefle was like meeting someone for the first time I seemed to have known forever. Her arguments were my arguments. Her pain was my pain. A trick of déjà vu set in, even though I was reading her essays for the first time. Stephen Sparks writes about Ruefle’s Madness, Rack, and Honey in the latest issue of Music & Literature , “What about a book whose effects can be felt forward and backward, today and yesterday?” The issue explores Ruefle’s work, along with the Brazilian novelist Clarice Lispector and the music of Maya Homburger and Barry Guy. I read the issue cover to cover—I love the line from Lispector’s last interview, “We’ll see if I can be born again … I’m speaking from my tomb”—and I found myself returning to Ruefle’s work to see, as Sparks puts it, her “ability to think by means of the poem, through the poem.” Isn’t this why we write anyway—in hopes that while we may not figure out what we mean, the reader just might? —Justin Alvarez

Last week I went to watch King Lear with my mother. I often make the mistake, when reading Shakespeare, of taking him too seriously, but when seeing his plays performed, even the serious ones, I have more than once had the rather obvious realization that Shakespeare was funny. Thinking about these nuances I frequently miss reminded me of a video I’d seen a few years ago about the original pronunciation of Shakespearean English. (There’s a recent Studio 360 interview with the father/son team from the video as well.) As it turns out, our pronunciation of Shakespeare hides a lot of meaning and, sometimes, humor. The best example, I think, comes from As You Like It: “And so, from hour to hour, we ripe and ripe / And then from hour to hour, we rot and rot / And thereby hangs a tale.” An elegant statement about time and mortality, sure. But in the original pronunciation, “hour” sounds like “ore,” or “whore,” “ripe” like “rape,” and “rot” like “rut.” The meaning we understand is still there, but the line becomes a bawdy joke—“from ’ore to ’ore, we rut and rut.” It must’ve played well to a boisterous, standing-room-only crowd of drunken Englishmen in hose. —Tucker Morgan

Three Angry Women

Last weekend I had brunch with my mother, and she related an incident from the day of the interboro bike race. My mom was walking through Central Park and found her way, and the way of several other pedestrians, blocked by an apologetic young race marshal, who explained that certain paths were closed to accommodate cyclists. “But this is my circuit!” screamed an elderly woman. “Pardon my French, BUT I’M SCREWED!”

“It was extremely unpleasant,” said my mother. “I guess my generation can take yet another bow.”

Several days later, I was at the AT&T store, where a salesperson was patiently answering my questions about my newly upgraded phone. A lady of perhaps eighty, wearing black orthopedic shoes and carrying a cane, came in and sat down in the chair next to mine. From what I gathered, the young man helping her (“Franz”) was trying to explain that a cellular plan would be less expensive than the landline she currently used. “But I need my phone on my bedside table!” she kept saying, and refused to accept the fact that the cellular phone could, indeed, sit on her bedside table, or indeed anywhere else. Where would she plug it in? She demanded. Her outlet was under her bed! The young man seemed unfazed by this inquisition. And yet, after a few minutes she screamed, “If you keep wasting my time, I’m going to beat the crap out of you!”

And then yesterday I was in an office building where one of the elevators was out of commission. A passing maintenance man explained that there was a routine elevator inspection going on; we could use the elevator just down the hall. “No, I will not!” shouted the (yes) elderly woman standing next to me. “I pay my fucking taxes!”

(There was also the woman who screamed, “Don’t even think about it, honey!” when she thought I was trying to take her seat on the bus, but that was sort of different.)

“What is it with foul-mouthed old ladies, anyway?” said my mom, when I related these most recent encounters. Then, cheerfully, “One hopes, at least, that, say what you will, you will never have to deal with that with me!”

Hulk, the Brazilian Outsider

Hulk playing for Brazil at the 2013 FIFA Confederations Cup. Photo: Agência Brasil

The 2014 World Cup, which begins on June 12, is all about Brazil. It is the host country, its team is the favorite, its players and manager are the focus of a huge majority of the two hundred million people who live in the nation and millions more who live outside it. Thirty-one other national teams will be arriving in the country next month, some of them with arguably as good a chance of winning the tournament as Brazil. But until the Selecao—or the Selection, as the Brazilian team is called—gets knocked out of the World Cup, every other team will be a guest in its house.

At nearly every position on the field, Brazil fields some of the best players in the world from the best teams in the world: its star, the forward Neymar, who plays for Barcelona during the club season; its playmaker, Oscar, who plays in London for Chelsea; its defenders Marcelo and Thiago Silva, who play for Real Madrid and Paris Saint-Germain, respectively. The only thing the team doesn’t have this year is a Ronaldo; as the British writer John Lanchester pointed out before the 2006 World Cup, the team then nearly included four of them—“Ronaldao, Ronaldo, Ronaldinho, and Ronaldinhozinho: big Ronald, normal-sized Ronald, small Ronald, and even smaller Ronald.”

In place of all those Ronaldos, though, Brazil has Hulk—its starting right winger, who has a build far different from most any other soccer player in the country, or the world, for that matter. On the pitch, his upper body looks like someone tried to wrap an undersize jersey over a brick house. Hulk plies his trade at Zenit St. Petersburg, in Russia, almost as close as a Brazilian can get to soccer Siberia as the United States. He’s also somewhat removed from the country’s samba school of soccer, a style of play the nation prides itself on and that is commonly referred to as Jogo Bonito, or the Beautiful Game. It’s best represented this year by the creative footwork of Neymar and Oscar, who dodge and dart every which way while maintaining control of the ball as if it were on the long end of a yo-yo attached to their toes instead of their fingers. This isn’t Hulk’s game; his is more the battering ram.

Yet Hulk himself disagrees. “I don’t think my style of playing is different from the classic Brazilian style,” he says over the phone from his apartment in St. Petersburg, with the help of a translator, while his two young boys—Ian, five, and Tiago, three—run riot in the background. “I like to dribble. I like to turn heads with the ball. Maybe only my physical state can make someone wrong about my style of playing.”

“Hulk has technique,” says Juca Kfouri, Brazil’s best-known soccer journalist and a columnist with Folha de S.Paulo, “although it’s unrefined.” Kfouri compares Hulk to the powerful striker Vava, from the World Cup teams of 1958 and 1962. The Brazililan novelist Sergio Rodrigues finds Hulk’s style more reminiscent of Gil, from the 1978 team, who, like Hulk, used to dribble in from the right and fire left-footed cannonballs from a distance. “We do have strong, powerful players in Brazil football,” Rodrigues says. “It’s just that they are usually not the best.”

Or the most popular. “Hulk might walk down the street in Rio de Janeiro and Sao Paulo without being recognized,” Kfouri says. For a man who is nearly six feet tall and two hundred pounds, that would seem hard to do.

Hulk’s hulking statue.

Hulk, whose given name is Givanildo Vieira de Souza, grew up in Campina Grande, a city in the northeastern state of Paraiba, one of the poorer areas of the country, with a severely dry climate. Nearby beaches and the discovery of dinosaur tracks and prehistoric rock carvings draw tourists, yet the area is more known to the rest of Brazil as a place people emigrate from. Hulk did just that, at sixteen, when he moved to Portugal for a year of soccer training. Two years later he landed in Japan, where he helped the club Tokyo Verdy get promoted from the league’s second tier to its first. In 2008, he moved back to Portugal and spent four years with the club FC Porto. The team won the league championship three of those years, and Hulk led it in scoring twice. He was so important to Porto that a statue of him, shirtless, in his trademark-goal celebration pose—an imitation of Lou Ferrigno’s TV Hulk in full flex—now stands in the team’s museum. (Hulk’s father was a fan of the television program, and nicknamed his son after it.)

“That’s the first people ever heard of him in Brazil,” says Rodrigues, whose first novel to be translated in English, Elza: the Girl, will be published this fall, and who will be covering the World Cup for the Brazilian weekly Veja. “It was a bit of, ‘Oh, it’s Portugal. It’s easy to do that in Portugal.’”

When Scolari took over as manager for a second time, in late 2012, Hulk became a fixture in Brazil’s starting lineup, after he’d moved yet again, this time to Russia. Scolari placed him on the right wing, mirroring Neymar on the left, with the injury-riddled striker Fred parked in between them. Scolari seems to like that Hulk’s wrecking-ball moves and powerful left foot give the Brazilian team a second option in the rare instances that Neymar and Oscar’s skilled acrobatics aren’t working.

The fans haven’t necessarily agreed. In a friendly match in Rio de Janeiro prior to last summer’s Confederations Cup, Hulk was booed for taking the place of the more beloved, and technically proficient, homegrown player Lucas Moura, who currently plays for Paris Saint-Germain and didn't make the final cut for this summer's team.

“I went out of Brazil very early, so the people in Brazil didn’t know me well. So they didn’t support me so much,” Hulk says. “I was never intimidated by this because I always knew that I had to go to the field and do my job. But when we had the Confederations Cup last year everything changed, and now it’s the opposite way.”

Indeed, the booing stopped, and when Hulk left the field he was more often applauded than not. Brazil won the tournament—beating the likes of Italy and Spain—and Hulk played well throughout, but he didn’t score. “It’s one of the reasons people feel suspicious,” Rodrigues says. “The Confederations Cup was Neymar’s playground, and Hulk was just one of the sidekicks.”

Brazil hosted the World Cup once before, in 1950, before it had ever won any of its five championships. Its national team breezed its way to the final that year, where it lost in a shocking upset to Uruguay. The country still hasn’t gotten over it. “It’s one of those national traumas,” Rodrigues says. “It’s like the Kennedy assassination. It’s that bad.”

In the years that followed, Nelson Rodrigues, the country’s most respected playwright—who was also a soccer journalist—coined the phrase complexo de vira-lata, or “the mongrel complex,” to define the inferiority issues that plagued the nation following the loss. If Neymar doesn’t shine at this year’s World Cup, Brazilians will count on Hulk to do so instead. But if neither of them do, it will likely mean someone from somewhere else did, and who knows what complex could result from that.

David Gendelman is research editor at Vanity Fair. Follow him on Twitter at @gendelmand.

Acrobats and Mountebanks

This week, Project Gutenberg made available Acrobats and Mountebanks, an 1890 book that explores the circuses, fairs, carnivals, and hippodromes of nineteenth-century France. Written by Hugues Le Roux and Jules Garnier, and translated from the French by A. P. Morton, the book features 233 illustrations of clowns, trainers, tamers, equestrians, equilibrists, acrobats, gymnasts, contortionists, fortune-tellers, dwarves, elephants, carousels, Ferris wheels, and all the trappings of classic mountebankery. It’s worth perusing for the drawings, a selection of which are presented above—but it’s also, after more than a century, still an astonishingly funny read, full of sharp observations and acerbic asides. Here, for instance, is a passage on dwarves:

No one should wonder at the fact that many people are more interested in the abnormal than in the beautiful. But this trait being once recognised, the dwarf is more wonderful than the giant; man is such a complicated machine, that in watching these microscopic creatures who gesticulate and speak like ourselves, we feel something of the same astonishment that would strike us if we found the seconds marked by a miniature watch which we could only see through a magnifying glass. For this reason the dwarf show is one of the most popular booths in the fair.

Every one knows that there are two kinds of dwarfs—those who are naturally dwarfs, and those who, as children, were at first of average size and growth, but whose development was abruptly checked. In their case the limbs which no longer grew, were yet capable of enlargement. As a rule the head is enormous. Monsieur François, from the Cirque Franconi—the partner of Billy Hayden the clown, the tiny circus rider—is a typical specimen of this class of dwarfs, who are called noués to distinguish them from the perfect miniature of humanity. They are physically deformed, but in all other respects they resemble other men. François, for instance, is very intelligent. I shall always remember our first interview two years ago in Erminia Chelli’s box at the Cirque d’Eté.

“How old are you, Monsieur François?”

“Twenty.”

“I am older than you are, M. François; yet, as you know, I am not celebrated.”

M. François shook his head … “You see not every one can be a dwarf.”

And on entering a lion’s cage:

I, who now address you, have entered a black-maned lion’s cage quite recently. Oh! do not exclaim at my heroism …When the beast, who at first grumbled a little, was sitting up and seemed composed again, my companion called to me:

“Come in, now!”

I went in cautiously at the back, taking two steps forward, so that I might still be nearer to the door than to the lion. I must own that the desert king did not honour me by even turning his head. He was talking to his tamer. The two gentlemen left me standing, and I looked rather like a bootmaker waiting for orders from a nobleman.

Man is a coward. The lion’s contempt gave me courage. I advanced a step so that I could touch the leg of the beast.

“Oh!” I said, “how silky it is!”

It was not silky at all, it was abominably harsh.

Since then I have reflected upon the feeling which could have induced me to utter this falsehood, and the result of this self-examination is so humiliating that I will confide it to you as a penance. In fact “how silky it is” was prompted by an instinct of base flattery—a courtier’s compliment—the toadyism of a coward who felt himself nearer to the lion than to the door.

The boldest individuals, who put their heads two or three times a day into the lion’s mouth, have told me that the best way to withdraw it from the gulf is, first of all, not to open the acquaintanceship with this experiment; and, secondly, to perform it with great nerve.

Nerve, that is the great secret of the lion-tamer, the sole cause of his authority over his beasts. When he has studied a subject for some time, endeavouring to master its character—and amongst the higher animals the character is very individual, very accentuated—one morning the man quietly walks into the cage. He must astonish the beast and over-awe him at once. As to the training, it consists—and here I quote the words of an expert in such matters—in commanding the lion to perform the exercises which please him; that is to say, to make him execute from fear of the whip those leaps which he would naturally take in his wild state.

There is one fact which no one would suspect—that it is easier to train an adult lion taken in a snare than an animal born in a menagerie. The lion of the booth is in the same position as sporting dogs which play much with children; they are soon spoilt for work. Pezon possesses five or six lions which he has brought up by hand. As a rule they live with the staff of the menagerie on terms of perfect familiarity, but this frequently leads to tragic accidents.

Lions, even lions in a fair, will devour a man in fine style.

Can I say that the fear of such an accident is ever sufficiently strong to make me pause on the threshold of a menagerie? No. I cherish, and, like me, you also cherish, the hope that some day perhaps we may see a lion-tamer eaten.

And, maybe most fetchingly, on the appeal of carnival food:

Do you remember, my dear friend, the drive we took outside the shows and bands, one fine Easter-Tuesday, brilliant with sunshine? You dared not leave your brougham, you were so alarmed at the hoarse roar of the crowd, the explosion of crackers, the shrieks of the women in the swings. Still you had one great desire that you would not own to me, half dreading a reproof, a wish evoked by a most appetizing odour which made your nostrils dilate.

“I am sure you are longing for some fried potatoes,” I cried triumphantly at last.

Ah! who would ever forget the glance with which your eyes rewarded me for guessing your fancy!

Let’s Hear It for Refrigerators, and Other News

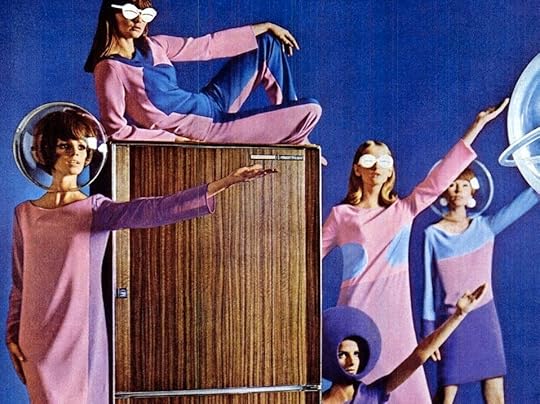

From Life, November 19, 1965. Via the Appendix.

BREAKING: FLAUBERT NOT A REALIST, SAYS EXPERT TESTIMONY

Nathaniel Mackey has won the Ruth Lilley Poetry Prize: a cool $100k. Don Share, editor of Poetry magazine, says, “The poetry of Nathaniel Mackey continues an American bardic line that unfolds from Whitman’s ‘Leaves of Grass’ to H.D.’s ‘Trilogy’ to Olson’s ‘Maximus’ poems, winds through the whole of Robert Duncan’s work and extends beyond all of these. In his poems, but also in his genre-defying serial novel (which has no beginning or end) and in his multifaceted critical writing, Mackey’s words always go where music goes: a brilliant and major accomplishment.”

The rise and fall of the conventional romance novel: “By the seventies, Harlequins became known for their lush language, which often evoked settings that sounded like Thomas Kinkade paintings: ‘The rolling tide of summer grass had engulfed the small meadow in a sweet-smelling flood of lambs’ tails, coltsfoot, feverfew, the drifting pollen from them like pale yellow dust on Linden’s bare arms as she lay full length among them.’” Now self-published erotica, much of it hardcore enough to make your average Harlequin heroine blush, have eaten into sales.

We take our refrigerators for granted, but history reminds of the glories inherent in artificial refrigeration, which used to blow people’s minds.

Google now offers a street view of the Grand Canyon: “On the virtual river you can fast-forward downstream, avoiding the soaking rapids and searing sun, putting in and taking out as you please. But part of the Grand Canyon experience is surrendering to the flow of the river and committing to the journey. Anyone who has traveled in canyon country knows how much the terrain can change in a matter of seconds during an afternoon rainstorm, or in the hours between noon and dusk, as sunlight glistens and fades upon the canyon walls. To these subtle but vital gradations, Google’s roving digital eye remains conspicuously blind.”

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers