The Paris Review's Blog, page 702

May 22, 2014

Minutes from the Second Annual Meeting of the American Society of Microscopists

It’s late, and you’re still awake. Allow us to help with Sleep Aid , a series devoted to curing insomnia with the dullest, most soporific prose available in the public domain. Tonight’s prescription: “Minutes from the Second Annual Meeting of the American Society of Microscopists,” published in 1879 .

Eric Earnshaw, After Lunch, 1942

The American Society of Microscopists met in Second Annual Convention, pursuant to the final adjournment of the First Annual Session, in the Central School building, Buffalo, New York, at ten o’clock a.m., August 19th, 1879; the President, Dr. R. H. Ward, in the chair.

The Rev. Dr. Van Bokkelen, of Trinity Church, offered prayer.

Then, on behalf of the local Microscopical Club, Dr. H. R. Hopkins welcomed the visitors with the following address:

Mr. President and Gentlemen: let us exchange congratulations upon this the occasion of the second meeting of the American Society of Microscopists.

I most heartily congratulate each and all of you who have the pleasure of remembering that you assisted in the work of founding this society, and I also congratulate all of you who have the opportunity of attending the second meeting and of enrolling your names among the lists of its members. I also ask you to congratulate the citizens of Buffalo upon the fact that the second meeting of this society is held in our city.

I congratulate you upon the hearty cordiality with which you are made welcome by every member of your local committee, and the various societies and associations which that committee represents, and I ask you to congratulate us upon the cheering prospects that our expectations of the pleasure of listening to your deliberations are so near fruition.

Again I congratulate you upon the fact that there is an American Society of Microscopists, and I believe that the work of recording what Americans have done and are doing for the advancement of this department of science can safely be trusted to the future of the Society. With this thought in my mind, I must congratulate you upon the prospect of having with you one who has had the rare good fortune to teach the world how to make objectives, whose angles extend far outside the limits which authorities had fixed as the boundaries of the possible. Let us give all honor to the modest yet noble American, Mr. Charles A. Spencer, at once the father and the genius of Modern Microscopy.

Bright and pleasing to me as are these thoughts with which I would welcome you on this occasion, there are others which call for still more hearty congratulations. I sincerely congratulate you upon the nature of the study which this society is intended to facilitate and encourage. The labor of the Microscopist is a hopeful labor, and although discouragement and despondency will come to all, although many must fail and but few succeed, yet in the light of the glorious triumphs of the various makers and workers of the microscope, triumphs which, within the period spanned by the memory of many now present, have produced the high degree of perfection of our optical and mechanical appliances; triumphs which have given birth to whole departments of scientific knowledge, neither discouragement or despondency can long prevail. But, beyond and above the glorious inspiration which history gives us, are we not made hopeful by the feeling that the indomitable perseverance and faith which impels the student to strive and seek after new truths, is, of itself, a sign and a promise that to some patient worker nature is still waiting to reveal herself?

Therefore, I congratulate you upon the nature and character of the work you have in hand, upon the sublime patience, courage and glorious achievements of the lathers—upon the character, the zeal and the inspiration of your coworkers, and upon the organization which gathers all these elements and from them weaves the web of progress.

In behalf of your local committee, and the different learned and professional societies which that committee represents, I welcome you to Buffalo. May your meetings and deliberations be as profitable to you as they will be entertaining to us.

The Society recognized the reference to Mr. Spencer's name by a hearty applause. Dr. Hopkins at the conclusion of his remarks, introduced the Hon. George W. Clinton, of the Society of Natural Science.

Judge Clinton said that, in common with the preceding speaker and the gentleman who was to follow him, he regretted that custom compelled him to confine his words to those of welcome, and to subjects with which they were more familiar than he. He was glad, very glad, to see them there. He was sorry that he had not been able to prepare a more suitable address. He had merely jotted down a few notes which he might have altered. He did not know really what he ought to say about the microscope, the mighty instrument which they had come there to study and honor. In its simplest form, the lens, they were well aware that it had come down to us from remote ages. By the aid of this, man's intellect had discovered the telescope by which volumes had been learned of the stars. It had also given them the microscope by which the things of the “heavens below” have been and were yet studied. And in that study of the infinitesimal, it seemed to him a richer knowledge was secured than could be gained by the study of infinite vastness. In microscopy, science and art were so intermingled as to be difficult of separation. Was it a science or an art? Strictly speaking he should say that it was neither. It furnished food for all the sciences; it nourished all the arts. He was very glad to see the American Society here. He knew that the citizens of Buffalo held them in high esteem, and he was sure that their stay would be made as pleasant as possible.

Of all the sciences represented there was none more dependent upon microscopy than was his own (Botany). It was, therefore, with the utmost cordiality that he bade them welcome.

Dr. Thomas F. Rochester followed with the following words of welcome for the medical profession:

There is no pleasanter word to hear or to utter than welcome. And when, a day or two since, the speaker was designated to say it to those here assembled for the physicians of Buffalo, he felt that he was much honored in being made their representative to discharge a most agreeable duty. It is not, however, as strangers that we meet. There is in science a bond of fraternity at once broad and yet close and cordial. The scholar of one section is affiliated to those of others, however near or remote, not only by common pursuits and investigations, but also by that higher and loftier spirit which is evolved by intellectual progress, and develops of necessity a feeling of congenial and fraternal interest toward all who strive to make mind dominant over matter. In addition to these conveniences and effects of an educated and elevated intellectuality, there is between you and us a closer and more intimate tie, but not a more binding or exalted one—that is a professional one. A physician must either be himself a microscopist, or must have almost daily recourse to one, for the necessary information to practice his profession correctly and conscientiously, not to say successfully.

Nothing is hazarded in taking for granted that a large proportion of this audience consists of medical men. The microscope, at first a necessity for professional instruction and information, becomes a delight and attraction which captivates its employer and leads him on and on in the boundless fields of science, which it unfolds to him and illuminates with a beauty of design and structure of which no description can give an adequate idea, and of which the most abstruse thought and the most vivid imagination could never have conceived.

What the microscope has done, and is doing, for medicine can only be alluded to. By it alone we observe the minute homogeneous and wonderful processes by which the human body is evolved from a simple cell to the complete structure we call man. By its information we recognize diseases as local and parasitic, which for ages have been considered constitutional. By it, the various secretions and excretions of the body are examined, and it alone often determines whether important organs are functionally or structurally disordered. In chemistry, by determining form, it often enables the examiner to predict probable properties.

These things and many others the microscope has done for medical science. How much more, it is difficult to surmise. Your chief reason for gathering here from all points, many of them far distant, is to extend the knowledge and promote the use of microscopy. Such meetings, apart from their delightful social elements, must afford you great pleasure and information, and by every advance you make, is medicine correspondingly aided and elevated.

The late Valentine Mott, in his day the most celebrated of American surgeons, designed for himself a coat-of-arms, the subject being a closed hand with the forefinger extended and terminating in an open eye, indicating that his touch was so delicate and correct that it gave as positive information as vision. But what is this to the microscope ; which metaphorically covers us with eyes, which penetrate into the hidden depths of nature and bring out for our instruction and delight visions of wonder and of beauty and of power? As confreres, and as the promoters of this science of sight, again welcome, and thrice welcome.

To these cordial welcomes, Dr. Ward replied as follows:

It is no common pleasure to be able to receive and accept the welcome to this Society extended by you, and through you by the citizens of Buffalo, and to give voice to the reciprocation by our members to your words of courtesy and appreciation. We meet you under peculiarly pleasant circumstances. Those of us who had the pleasure some years ago of attending the Buffalo meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, will never forget that meeting as distinguished not only by its high scientific standard, but also by the cordial, thoughtful and delicate hospitality, which made the week memorable; and from the prompt acclamation with which the invitation to meet in your city at this time was accepted last year, I fear you may have acquired a reputation which will some time be troublesome. But for all this we have been pleasantly disappointed this summer. We expected the careful and convenient arrangements which your committee have made for our comfort and our work; but we never dreamed of their supplying us with the coolest, not to say coldest, weather that was ever seen in the midst of dog-days.

In one other respect our position is peculiar. Our Society is in its infancy, one year old, and just learning to walk. But though small in years, its size is considerable, its members are numerous, and those who are interested in it represent not only the various centers of scientific culture, but also the most quiet and secluded nooks in the country. We are brought together by an enthusiasm almost unknown in any other branch of science. We are stimulated by the study of those little things which led a philosopher to call God great in great things, greatest in the smallest.

We meet with the expectation of a most profitable session, and we thank you heartily for your interest and encouragement.

The Secretary, Dr. Henry Jameson, not having arrived, Dr. Carl Seiler, of Philadelphia, was elected Secretary pro-tern.

A recess was then taken for ten minutes, to give the members in attendance time to register their names, and to prepare applications of candidates for membership.

Still awake? Read more here.

Gatto Nero

Corinne May Botz, The Roehrs House, Franklin Lakes, New Jersey

Back in the day when video stores existed and I used to patronize them regularly, I depended particularly upon the judgment of a cinephile clerk named Will. One day, I went into his Brooklyn store and found someone different behind the counter.

I explained to him what I was looking for: A creepy psychological thriller/horror movie along the lines of Don’t Look Now, The Innocents, the original Wicker Man, Haunting of Hill House, Burnt Offerings, or Audrey Rose. (I added that, despite its mediocrity, there were things I liked about Skeleton Key.) In short, I tend to like a not-too-silly movie dealing with ghosts and the occult. I am especially drawn to those set in the 1970s, in which everyone is seemingly punished for the naivete of belonging to a happy family (just as a decade later one would be punished for being a teen girl). Catholic clergy is a plus. Hammer horror, serial killers, vampires, zombies, malevolent animals, and monsters of other kinds need not apply.

We discussed this earnestly for some time and he determined that I must rent the 1981 version of The Black Cat, loosely based on the eponymous Poe story. As he seemed to understand exactly what I was looking for, I was very excited and set aside a whole evening for viewing.

Well, The Black Cat was idiotic. Campy, goofy, and full of fake blood. I hope I’m not spoiling anything for anyone when I tell you it’s about an evil cat (black) who mauls people.

It is a funny thing—or maybe it’s not—but every time someone close to me has died, I have had an overpowering desire to watch ghost movies, read chilling stories, and, like a post-WWI Spiritualist, immerse myself in the uncanny. (Maybe it’s the result of growing up without religion, and with movies and books.)

Bereaved or otherwise, if your tastes run to the Gothic, I highly recommend Haunted Houses, a collection of first-person accounts edited and illustrated by the photographer Corinne May Botz. There are a number of spine-tinglers, and the combination of subtly evocative visuals and frank narration is eerie and engaging.

But there was one part that stood out especially for me, and not just because it concerns St. Barnabas Episcopal Church, near where I grew up (and site of an excellent annual rummage sale). The former minister testifies to the many instances of hauntings in the church, then says,

I don’t know how you scientifically deal with that. I’m sure there are ways of saying that it was a bad dream or a projection, but it happens and it’s not surprising believing in the communion of saints as I do. I think, “Yeah so? What’s so surprising about it?” There’s a fine line between the next world and this. It’s all one reality and we can’t divide it up, reality is reality. We know a little bit from Einstein about time, relativity and space, and that one interacts with the other. Time is a human construct anyway… who says there’s a great division about past, present and future? Who says we can’t visit those places in the so-called past? Now is all we have.

There is certainly plenty to argue with here, if one is so inclined. And as he implies, a certain degree of suspension—or faith—is required. But however much of a rationalist or skeptic one might be, it’s an interesting idea: that things are not uncanny unless they are breaking rules—and those rules themselves are sometimes constructs.

I forgot to return The Black Cat, and then the video store closed, permanently, shortly thereafter. The result is that I still own the DVD, which I just ran across in a box of old stuff at the back of my closet. Obviously, I watched it immediately. And something about it was very comforting; maybe I have come to enjoy suspending disbelief.

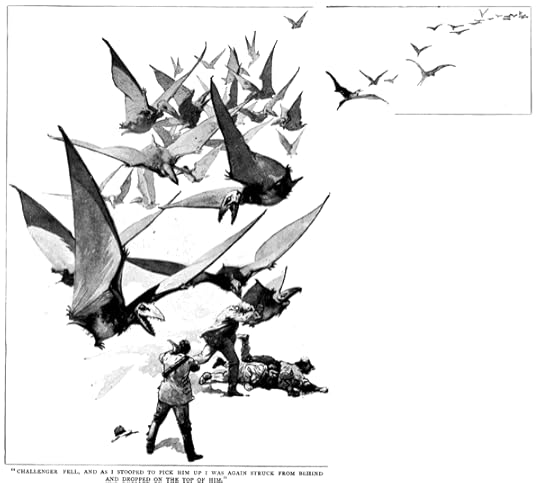

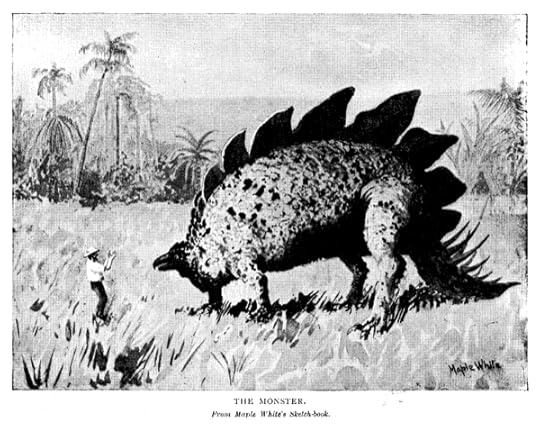

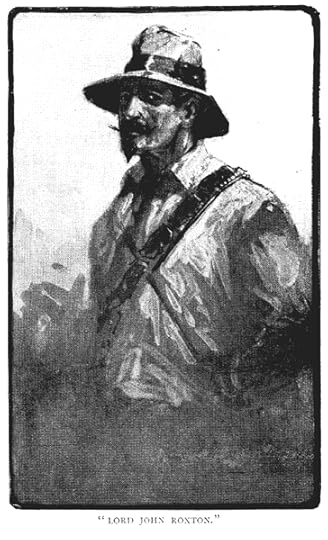

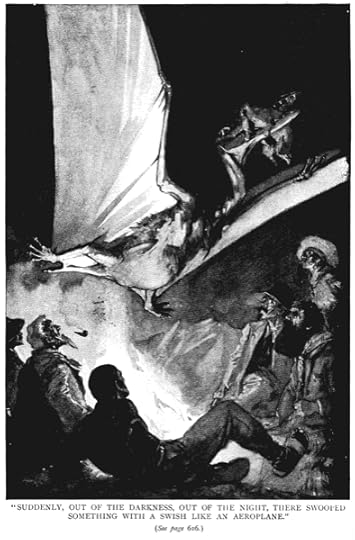

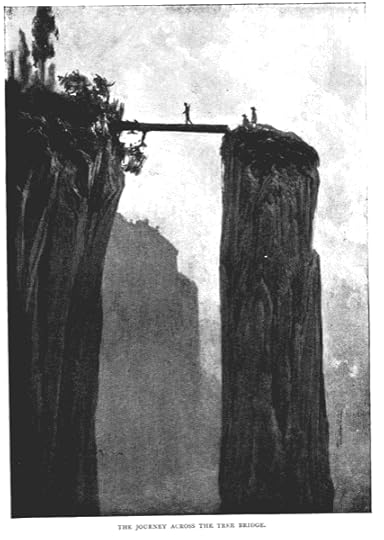

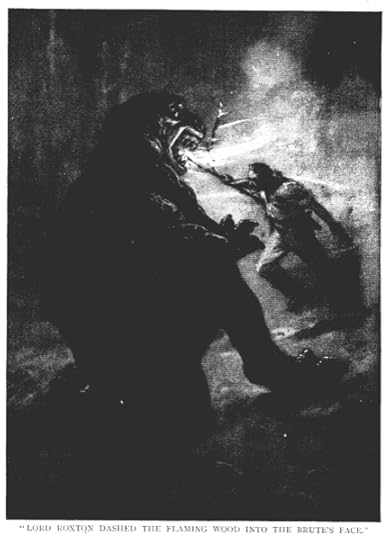

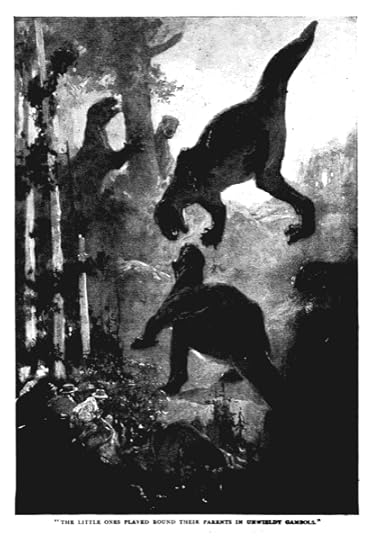

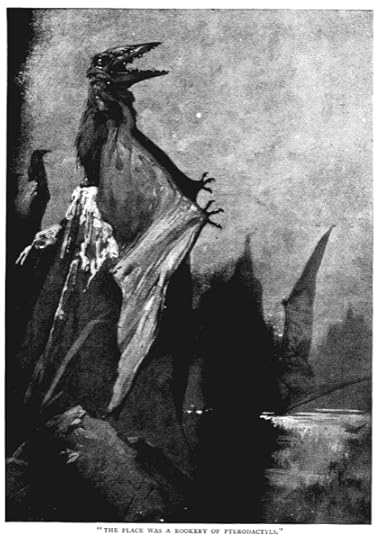

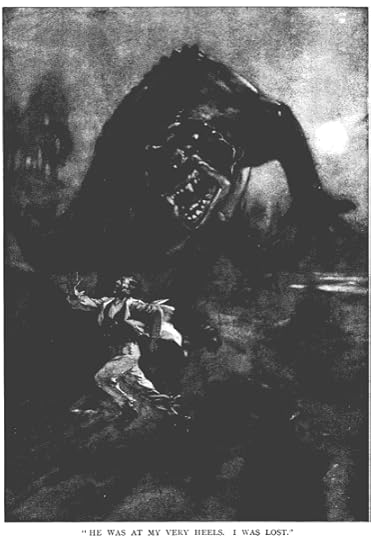

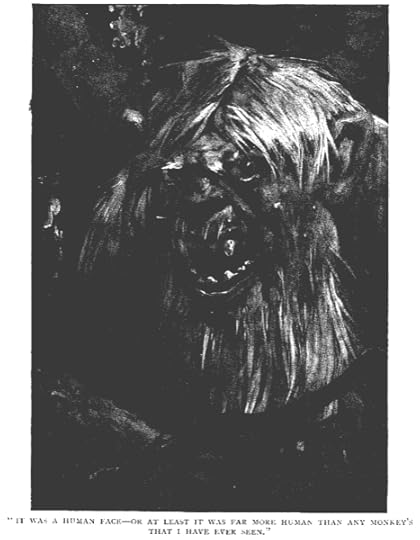

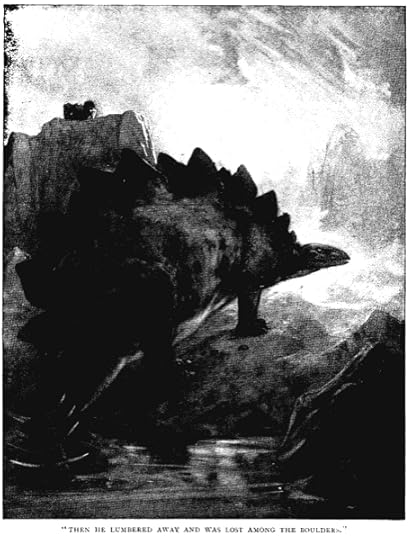

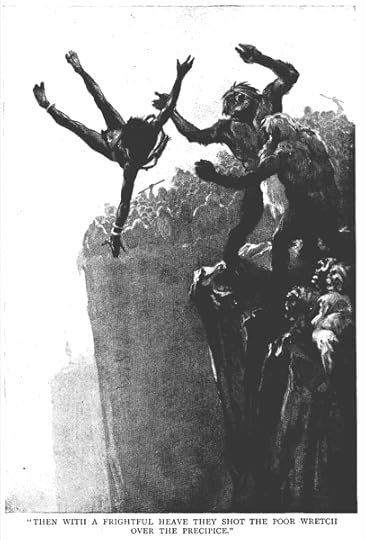

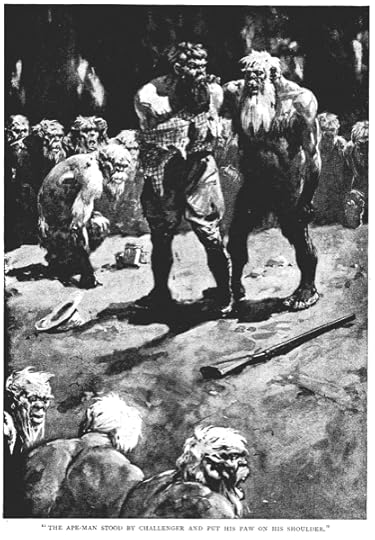

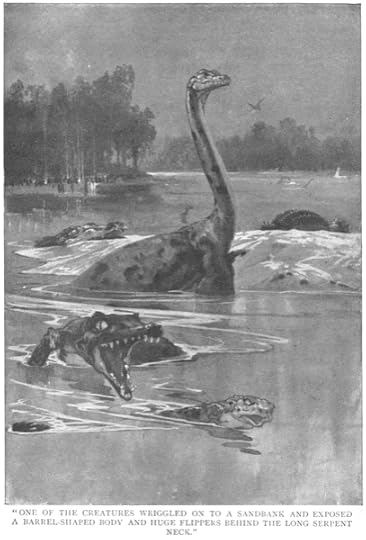

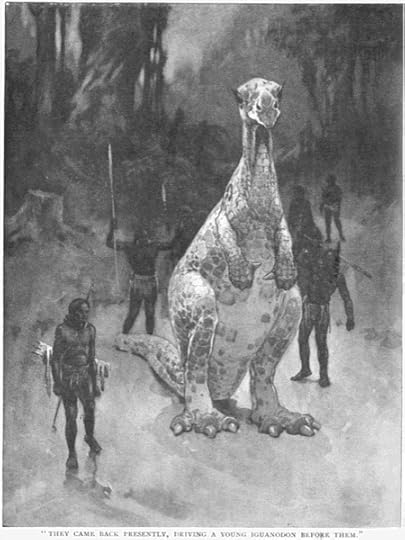

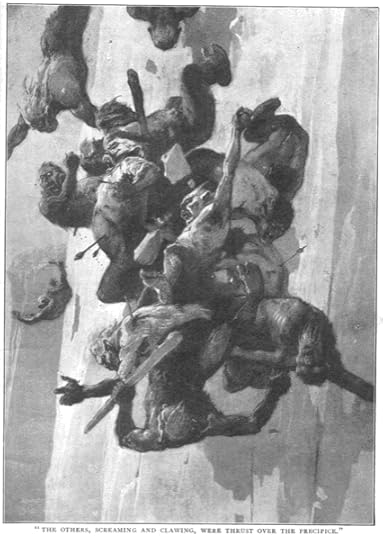

A Rookery of Pterodactyls

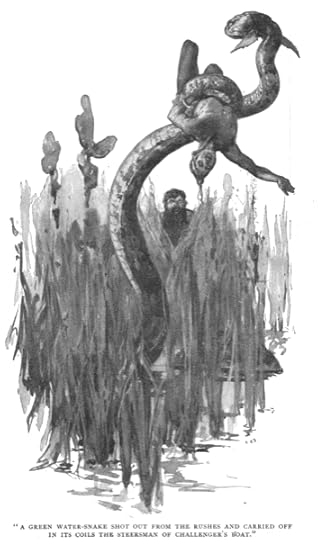

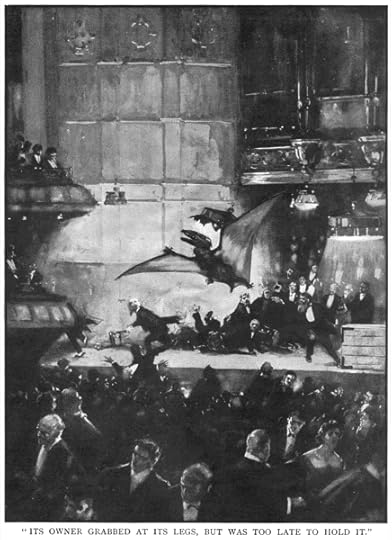

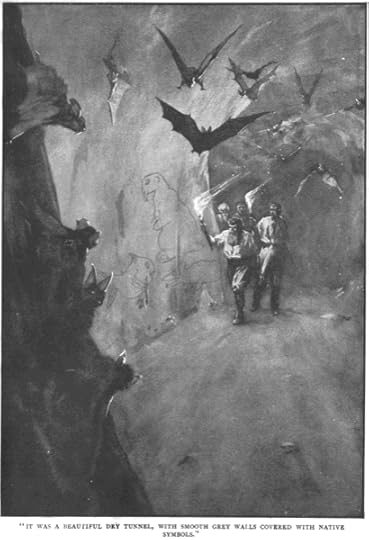

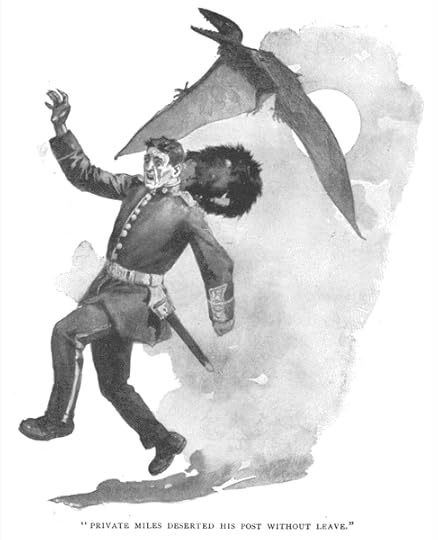

In celebration of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s birthday, have a look at these illustrations from the original serialization of his novel The Lost World, which appeared in The Strand Magazine from April through November of 1912. Conan Doyle’s novel tells of an expedition to South America, where—wouldn’t you know it?—dinosaurs still roam the earth. Everyone associates Conan Doyle with Sherlock Holmes, but The Lost World also left its mark on popular culture: though Conan Doyle borrowed a large part of its conceit from Jules Verne, it remains the paradigm for a sort of swashbuckling supernatural adventure, full of bumbling professorial types and out-of-their-depth journalists and strapping, granite-abdomened men in pith helmets. It’s served as the source material for everything from The Land That Time Forgot to Land of the Lost and plain old Lost, and, of course, for Michael Crichton’s The Lost World, the sequel to Jurassic Park.

This is no country for Jeff Goldblum, but these illustrations, full of terror and adventure, do seem like the sort of thing Steven Spielberg and George Lucas might have hanging in their offices—and there’s definitely something of that Industrial Light & Magic awe in Conan Doyle’s vivid description of a pterodactyl nest:

Creeping to his side, we looked over the rocks. The place into which we gazed was a pit, and may, in the early days have been one of the smaller volcanic blow-holes of the plateau. It was bowl-shaped, and at the bottom, some hundreds of yards from where we lay, were pools of green-scummed, stagnant water, fringed with bulrushes. It was a weird place in itself, but its occupants made it seem like a scene from the Seven Circles of Dante. The place was a rookery of pterodactyls. There were hundreds of them congregated within view. All the bottom area round the water-edge was alive with their young ones, and with hideous mothers brooding upon their leathery, yellowish eggs. From this crawling flapping mass of obscene reptilian life came the shocking clamor which filled the air and the mephitic, horrible, musty odor which turned us sick. But above, perched each upon its own stone, tall, grey, and withered, more like dead and dried specimens than actual living creatures, sat the horrible males, absolutely motionless save for the rolling of their red eyes or an occasional snap of their rat-trap beaks as a dragon-fly went past them. Their huge membranous wings were closed by folding their forearms, so that they sat like gigantic old women, wrapped in hideous web-colored shawls, and with their ferocious heads protruding above them. Large and small, not less than a thousand of these filthy creatures lay in the hollow before us.

The (Midfield) Engine That Could

Kyle Beckerman. Photo: Warrenfish, via Wikimedia Commons

There are eleven positions on a soccer team, each with its own character. None is more glamorous than the striker, whose job is to score the goals in a game that has so few of them. None is more romantic than the goalkeeper, who stands alone as the team’s last line of defense, the only player who can use his hands in a sport that depends on the use of the feet, the head, and every part of the body but the hands. None is more celebrated than the Number 10, known sometimes as the fantasista, the team’s playmaking superstar who’s asked to supply the creativity that can undo the most rehearsed and structured defense. Yet despite the spotlight that shines on those players, the midfield position situated just in front of the team’s defensive backline is perhaps the most critical of all. Depending on a coach’s preference, a team’s formation, or a player’s talents, that position can be a defensive one, an offensive one, or a blend of both. In most every case, though, it’s the pivot on which the rest of the team turns.

“There’s a reason why they call it the engine of the team,” said Taylor Twellman, a soccer analyst for ESPN. “It controls so many things. The game is determined on the strengths of your team in that position.” Traditionally, the role of that player has been a defensive one, and it often still is. Kyle Beckerman, who sports a powder keg of dreadlocks that makes him easily identifiable on the field, has filled the role for the United States team: his hard tackles and deft touch have made him one of the best holding midfielders, as the traditional name of that position is known, in Major League Soccer, where he is the captain for Real Salt Lake.

“The biggest thing is that it’s a transition position,” Beckerman said. In a game where possession changes hands (or rather, feet) constantly, this is no small thing. When your team is attacking, Beckerman said, “you’re trying to sniff out things before they happen.” This could mean making a tackle that would allow the rest of the team time to catch up to the play—and, at the same time, risking a mistake that would leave the team vulnerable behind him. The way Beckerman performs it, that tackle is often a hard one, straddling the line between a referee’s whistle and a yellow card, and usually incurring the wrath of the opposing team’s fans.

In the World Cup, Javier Mascherano, one of the best of these players, will fill this same role for Argentina, a team that fields one of the most explosive offenses in the world centered around Mascherano’s superstar teammate at Barcelona, the Number 10 Lionel Messi, and Manchester City’s celebrated striker Sergio Aguero. “With the attacking options they have, Mascherano’s going to play a vital role in Brazil,” Twellman said. “In that position, defensively you have to have an unbelievable tactical awareness of where you need to be in each defining moment. He’s got to make the right decision at the right time.” Those right times become one of a match’s recurring subplots. A split-second hesitation can change the outcome of the entire game.

The transition role works in the opposite direction as well, when a team starts its move forward on offense. As Twellman put it, “The modern version of that player is much better technically than thirty or forty years ago.” Though they’re both defense-minded, Beckerman and Mascherano handle the ball with an unconscious ease; it seems to roll off their feet effortlessly. Their outlet passes might not be the ones that lead immediately to a goal, but they are often the first step toward scoring. “You want the attacking guys to be creative, you want them to have imagination,” Beckerman said. “It’s trying to make their game easier. So a lot of times it’s getting the ball to the attacking midfielder where he has time and space to make the killer pass to the guy who scores.”

The more offensive a player’s abilities, the more that natural ease with the ball turns into gifted creativity, making him a constant threat. Italy’s Andrea Pirlo has demonstrated this as well as anyone in the world—he shined in Italy’s 2006 run to the World Cup championship, and he led the team to the Euro 2012 final, where it lost to Spain. As Pirlo plays it, the position is known as a deep-lying playmaker, and every time he touches the ball the game’s temperature rises.

It’s also what England’s Steven Gerrard has, to much acclaim, done this season for Liverpool. “Some people like to have a defensive midfielder next to a Pirlo, and some people think you can have the defensive midfielder ahead of him and allow the Gerrards of the world to roam and play those long balls over the top and be dangerous from there,” Twellman said. “Gerrard can still impact the game from that role of playmaking untraditionally. Where everyone thinks a playmaker’s a Number 10, he’s playing underneath the forwards in that quote-unquote Pirlo role.”

And then there’s the rare player who’s uniquely gifted on both sides of the ball. Manchester City’s Yaya Toure often lines up for Ivory Coast in front of the defense, yet at times you’ll find him changing the course of the game on the other side of the field as well. “He is your definition of a two-way midfielder,” Twellman said. “He applies pressure out of the midfield defensively, but what makes him so good is his ability to recognize, now is my opportunity to make that run forward … And he does it [for Manchester City] at an alarming rate in arguably the best league in the world.”

Twellman cites the former Manchester United captain Roy Keane, currently an assistant coach with Ireland’s national team, and Dunga, the captain of Brazil’s 1994 World Cup championship team and its 2010 World Cup coach, as two of the best players at that position in the last couple decades. Beckerman says he learned how to play it from American Pablo Mastroeni, who now coaches the Colorado Rapids, when the two were teammates in Colorado early in Beckerman’s career. It’s no coincidence that all three of those players have graduated to coaching. The position is inherently a leadership one. Whereas a goalie, a striker, or a winger might disappear from the match for long stretches of time, the deep-lying midfielder will rarely be uninvolved. Instead, he’s often at the center of its action, dictating the game, setting its tone.

David Gendelman is research editor at Vanity Fair. Follow him on Twitter at @gendelmand.

Beauty Is Not Truth, Truth Not Beauty, and Other News

Keats was wrong, scientists say, kind of. Keats’s drawing of the Sosibios Vase, c. 1819

Was Frank O’Hara the social-media whiz of his day? Well … “O’Hara’s Lunch Poems—like Facebook posts or tweets—shares, saves, and re-creates the poet’s experience of the world. He addresses others in order to combat a sense of loneliness, sharing his gossipy, sometimes snarky take of modern life, his unfiltered enthusiasm, and his boredom in a direct, conversational tone. In short, Lunch Poems, while fifty years old, is very a 21st-century book.”

With apologies to Keats, beauty is likely not, in fact, truth; nor, by transitive property, is truth beauty. “The discourse about aesthetics in scientific ideas has never gone away … Today, popularizers such as Greene are keen to make beauty a selling point of physics … the quantum theorist Adrian Kent speculated that the very ugliness of certain modifications of quantum mechanics might count against their credibility. After all, he wrote, here was a field in which ‘elegance seems to be a surprisingly strong indicator of physical relevance’ … We have to ask: what is this beauty they keep talking about?”

“The Chinese name diseases based on symptoms, so diabetes is known as ‘sugary pee.’” A few doctors wish to remedy this.

“Beginning in the late 1930s, Richard Edes Harrison drew a series of elegant and gripping images of a world at war, and in the process persuaded the public that aviation and war really had fundamentally disrupted the nature of geography … Harrison dazzled readers of Fortune with artistic geo-visualizations of the political crises in Europe and Asia. The key decision he made was to reject the Mercator projection, which had outlived its purpose.”

The anxiety (and ecstasy) of influence in Bob Dylan: “With the help of Google Books, Scott Warmuth, a fan from New Mexico, has been delving deeper into Dylan’s recent writing and finding all kinds of odd, uncredited borrowings. Passages from Dylan’s memoir, Chronicles: Volume One (2004), were taken from disparate sources: from H. G. Wells, Jack London, Hemingway, and Fitzgerald; from Tony Horowitz’s nonfiction book “Confederates in the Attic,” a travel guide about New Orleans, and an issue of Time, from 1961 … Dylan’s ‘appropriations were not random. They were deliberate. When Scott delved into them, he found cleverness, wordplay, jokes, and subtexts.’”

May 21, 2014

Robert Creeley’s “The Dishonest Mailmen”

Robert Creeley by Elsa Dorfman, 1972. Photo via Wikimedia Commons

I first came across “The Dishonest Mailmen” my sophomore year of college, when, having become so enamored of Robert Creeley’s oft-anthologized poem “I Know a Man,” I decided to buy a new edition of his collected poems—an indulgence, for someone without an income who was supposed to be reading Milton. (For the record, I carry around a lot of guilt about shrugging off Milton.)

I read “The Dishonest Mailmen” and identified with it immediately for reasons I didn’t understand, and indeed for reasons that specifically elude understanding. In its fifty-some words, it conjured equal measures of anger, tenderness, and apathy, an intoxicating combination … “for a student,” I almost wrote, but what I mean is for anyone. Still, there’s something in that couplet—“I see the flames, etc. / But do not care, etc.”—that remains to me the most profound evocation of a heart-heavy nihilism that seems to afflict people exclusively in their late teens. Mainly, let’s be honest, it afflicts white guys studying literature in their late teens, who don’t know what to do with themselves or how to talk to people or how to live unselfishly, and who are able to voice this not-knowing with increasing, brooding eloquence, and who are thus infuriating to themselves and others.

In Creeley’s poem, the offhandedness of that “etc.,” which appears three times, is a more compact whatever than whatever itself—more effective than an eye-roll or the lassitude in a plume of cigarette smoke. It summons all the disaffection and paranoia of any undergrad ever to loiter on the steps of some hallowed hall on some hallowed campus in some hallowed college town. “I don’t care, etc.”: exactly. It’s all that punk-rock acedia without the sneering. It’s a fact. It is, just as it says it is, “The poem supreme, addressed to emptiness.” When you’re nineteen, someone is always taking all your letters and putting them in the fire. But, again, wait, hell, it’s not just when you’re nineteen—we’re all encountering dishonest mailmen every year of our lives. We try to communicate and fail. We see the flames, etc.

When Creeley—who was, to give this post a belated peg, born today in 1926—reads the poem aloud, you understand better the small wonders he’s able to work with rhythm and enjambment:

As he says in his Art of Poetry interview from 1968,

I would be very much cheered to realize that someone had felt what I had been feeling in writing—I would be very much reassured that someone had felt with me in that writing. Yet this can't be the context of my own writing. Later I may have horrible doubts indeed as to whether it will ever be read by other persons, but it can never enter importantly into my writing. So I cannot say that communication in the sense of “telling someone” is what I'm engaged with. In writing I'm telling something to myself, curiously, that I didn't have the knowing of previously … I write what I don't know. Communication is a word one would have to spend much time defining. For example, can you make a blind man see? That has always been a question in my own mind. And if it is true that you cannot tell someone something he has no experience of, then the act of reading is that one is reading with someone. I feel when people read my poems most sympathetically, they are reading with me. So communication is mutual feeling with someone, not a didactic process of information.

That’s precisely what’s on offer in “The Dishonest Mailmen”: a mutual feeling of something neither the poet nor his reader knows.

They are taking all my letters, and they put them into a fire.

I see the flames, etc.

But do not care, etc.

They burn everything I have, or what little

I have. I don’t care, etc.

The poem supreme, addressed to

emptiness—this is the courage

necessary. This is something

quite different.

Chasing Away the Big Black Bird

Image: Richard Crossley

My buddy at work—I call him my buddy, but really he’s just the guy I hate the least—turned to me and asked which would be better: having one testicle or having three. I rolled my eyes and gave him the same answer I gave him every time he asks: three. I would prefer to have three testicles to having one because I’d rather be creepy than a little sad.

Then one night in the shower I discovered that my left testicle was the size and density of a small Cadbury Creme Egg. The doctor told me my testicle needed to come out immediately; it was malignant as hell. He probably did not actually say the words “malignant as hell,” but I went into shock almost immediately, and can only reconstruct events based on what happened next.

Twenty-four hours later, I was entering emergency surgery. The nurse asked if I’d like a prosthetic. “Would I!” I said. “Can I get two?” I was thinking of how awesome would it be to really double down and commit to this joke, surprising my work friend in the men’s room.

I also have a difficult relationship with my Virginian heritage—it would be perfect if I could have an actual Civil War–era musket ball put in there instead, to literally carry a heavy, awkward, and slowly poisonous reminder of our nation’s tragic past that I only talk openly about with my black friends when I am drunk.

But none of that happened. As it turned out, I wasn’t going to be creepy. I was going to be sad.

That first night after the surgery, I lay there in the dark next to my sleeping girlfriend. We met at an art gallery in Washington, DC, two weeks before I moved to New York. She is a forensic accountant, the sort of person who professionally pieces together evidence of systemic white-collar crime one e-mail at a time, except those e-mails are in Mandarin or Spanish. When I periodically complain that our lives are overly scheduled and I’d like to make room for some spontaneity, she says, “We can be spontaneous on the weekends.”

Now she rolled over in her sleep, clutching the pillow tight. Not me. That tumor snuck up on me when I wasn’t looking, and I’ve got to stay vigilant.

I thought it was going to be a soft, firm implant—like a miniature breast implant, artificial but at least a little squishy. Instead, it’s a dense silicone wad that pulled like a fishing sinker. I could feel what I imagined to be rough, angular edges on it, like a complicated die for the world’s saddest role-playing game. It hurt, scraping its living neighbor and the inner walls of my scrotum as I rolled over in bed. The doctors told me that my body would eventually encase it in tissue, giving it a more natural feel, but it could have used another trip through the rock polisher. Every jab and scrape was a reminder that something strange had happened—a private, alien footprint that only I could sense.

My girlfriend said “You know, we—women in general—never really care that much about the balls anyway. I’m probably not even going to really notice at all.”

She meant to be helpful and reassuring, but the terror transformed it, twisting her words into “It’s silly of you to be so sad about losing something so useless in the first place.”

The change was much more Freudian than physical. You don’t realize how much deep cultural programming you’ve absorbed about your testicles until you lose one. “Hey, don’t cut that guy’s balls off,” takes on a much more significant meaning, as does “man, that guy’s got a lot of balls.” I’ve always tried to live as boldly as possible, but was I just going to be a pretender now?

I lay back and looked up into the darkness. All my fear, doubt, and terror swirled, soaring like ragged ghosts in a tight circle emanating from my heart. They accelerated, blurring together and forming a black emotional waterspout with its tip in my chest. The other end of the spout bobbed up and down tentatively, then surged upward and opened a dark portal that seeped across the ceiling like a giant stain.

A giant black bird swooped down through the open portal and landed on my chest. It shuffled forward to put its dark beak into my ear and whispered:

“You’re not going to die tonight, but your life will never be the same. You have moved through a doorway, and it’s weird on the other side. You will never relate to other people the same way again. They’re going to try to talk to you, but you’ll never be able to connect. It’s going to be this way for the rest of your life. You’ll get used to feeling lonely, but it will never go away.”

I’ll be damned if that bird wasn’t right. My girlfriend is a cancer survivor, too. But she went through chemo and radiation, and I didn’t—she didn’t have any body parts chopped off, and I did. Our suffering is more or less the same size, but shaped very differently.

On the night that we met, I was wearing a fragrant T-shirt with a Pushead illustration of a fetal skeleton inside a bottle on it, while she had on a Christina Hendricks–esque wrap dress in a deep blue that set off a blood-red hair waterfall pouring down her back. I said, “Oh, hang on, you’ve got something stuck to your forehead there,” and she replied, “It’s probably just lint, stuck in the glue for my wig.”

“Oh,” I said, “is that not your real hair?”

She said, “Well, it grew out of somebody’s real head and I paid a lot of money for it, so I’d say that it’s my real hair now.” That’s how I found out that she was finishing radiation for Hodgkin’s lymphoma.

It’s not always that easy to communicate what I’m feeling, or to understand her when she says, “Everyone’s going to die, Jeff. Cancer patients just have more data.”

* * *

When other people learn you’ve had cancer, it makes the baggage that rattles around in their skulls fall right out of their mouths. They mean well and they want to comfort you, but the end result is much worse. People think that their favorite thing can cure your cancer, as long as that thing sucks a little bit: “Oh, I’m so sorry to hear that! Have you tried yoga? It can prevent all kinds of diseases, and it’s really good for you spiritually, too.”

A friend from high school sent me a text message—“Srry u hd cancer. U OK? Have U tried wheatgrass juice?”

Nobody comes up to me and says, “I’m so sorry to hear about your struggle. Have you tried getting really stoned and watching Pootie Tang?”

My girlfriend sleeps so hard that she smiles. While she sleeps sweetly next to me, the black bird comes back. It says, “You know, you’ve lost a lot of drive and energy. You’ve been skipping Muay Thai a lot lately, and when you do go to sparring class, you just kind of stand there and let people punch you in the guts. What’s going on with that?”

“Well,” I say, “It just doesn’t seem to matter if I block any particular punch or not. The blows are coming out of nowhere whether or not you’re ready for them, so why fight what’s coming at you?”

“I don’t know,” the bird says with a little smile, “it’s like you’ve been half-neutered or something.”

If this is all death is—lying in the dark, floating, forever, not warm or cold, just floating—then I could do that. I might as well. At least I wouldn’t have to hear about it from that stupid bird anymore.

It was CT scan day, a few months after my operation, and I was sitting in a waiting room at Sloan-Kettering, sipping a pinkish fluid meant to saturate my tissues with a contrast dye in order to provide the best possible image. It was mixed with Sunny Delight, in a halfhearted attempt to disguise the taste—instead, it tasted like the sweetened squeezings from an android’s gym shirt.

A couple entered. The man had hair that was perfectly silver at the temples and an anus-colored suntan, leading his stride with his sternum like the prow of a very expensive yacht. He looked personally responsible for the entire financial crisis. The woman, I could tell, had been gorgeous at one time, with flowing hair like a chocolate river flecked with gold foil. It absorbed the grim fluorescent light in the basement waiting room and excreted it as a honey-colored light. She had two fresh iceberg chunks for eyes, but cancer had ravaged her tanned body into a bathrobe wrapped around a pile of brown clacking antlers. Her breast implants had lost their body-fat camouflage and jutted out like twin thermostats in an old apartment.

They sat and she nestled into his chest. He fell asleep immediately with his head back and his mouth wide open.

“You know,” she said, poking him awake, “you might not be so tired if you weren’t out until all hours doing drugs with God knows how many other women.”

He harrumphed. “We discussed my habits very early in this relationship … I don’t think I should have to explain myself any further than that. I’m here to support you now, and that’s what’s important.”

“Your habits have other habits, you know,” she hissed. “You’ve got another nasty habit of not respecting my space, too. Like when I was at the apartment in Italy last month. You know I can’t think for myself when you’re around, and when I go there I need to be alone. But what do you do? You show up the very next day with all your friends and wreck my space, and the next thing you know, we’re all just doing blow and skiing like we always do. It never changes.”

He drew himself up, pushing her back, and said, “I’m really getting tired of all these accusations. I have never done a single thing I didn’t tell you I was going to do, and after all”—he paused to add a noble inflection to his voice—”I am here now to support you while you … fight cancer.”

“Well, good news, buddy, you’re free of that chore. Because we’re done—get out of my life, goodbye!” She turned and stomped out, slamming a door behind her.

As all this unfolded, at least four nurses appeared in the waiting room, pretending to peruse their clipboards. Now, another nurse shoved the woman back into the waiting room: “We’re not ready for you in here yet, honey. Just sit with your boyfriend until we call you.”

They sat there across from each other, seething through their nostrils.

And me, I just felt amazing. My heart soared. I had a touch of cancer, I’m short one testicle. But these people have money poisoning, and that shaves the buds off your heart’s tongue and it can’t taste excitement the same way that it used to. All you can do is rub cocaine and designer handbags and smoked salmon all over yourself, just to feel like you’re doing anything special anymore.

I ran up to the sidewalk as soon as the appointment is over, feeling the sun on my face for the first time that summer. I called my girlfriend at work, the same woman I’d been complaining to every day about feeling so lonely and alienated. She answered, and I said, “Oh my God, you are not going to believe the breakup that I just saw in the CT scan waiting room.”

“Try me,” she replied, “you see some great stuff in there. Let me shut my office door real quick and I want you to tell me all about it.”

And then, for just a little while, that big black bird flew away.

Jeff Simmermon is a writer, storyteller, and standup comedian in Brooklyn. He has appeared on This American Life and won The Moth's New York GrandSLAM in March with a version of this story. He produces and performs in “And I Am Not Lying,” a show featuring stand-up, storytelling, and burlesque, at UCB East. Follow him on Twitter @jeffsimmermon.

Underground

A sketch of Pope’s grotto.

Today marks the day of Alexander Pope’s birth, in 1688. We remember Pope as a poet, essayist, satirist, translator, and one of the most quotable men in English. He’s responsible for, among many other aphoristic gems: “To err is human, to forgive, divine.” “Fools rush in where angels fear to tread.” “What Reason weaves, by Passion is undone.” “Hope springs eternal in the human breast.” “A little learning is a dangerous thing.” And, yes, the phrase “Eternal sunshine of the spotless mind.”

In his time, he was also known for his amazing home, a Palladian villa at Twickenham surrounded by elaborate gardens and grottoes. Pope’s wealthy family was ostracized for its Catholicism, and his numerous health problems—he suffered from Pott’s disease, which stunted his growth to only four foot six—somewhat limited his social life. His home seems to have been a refuge, as well as a definitive indicator of his success.

The house, a Classical mansion surrounded by vast grounds, was grand enough, but it was the Homeric grotto that really got Pope’s heart racing. As he wrote at the time of its construction,

I have put the last hand to my works … happily finishing the subterraneous Way and Grotto: I then found a spring of the clearest water, which falls in a perpetual Rill, that echoes thru’ the Cavern day and night …When you shut the Doors of this Grotto, it becomes on the instant, from a luminous Room, a Camera Obscura, on the walls of which all the objects of the River, Hills, Woods, and Boats, are forming a moving Picture … And when you have a mind to light it up, it affords you a very different Scene: it is finished with Shells interspersed with Pieces of Looking-glass in angular Forms…at which when a Lamp…is hung in the Middle, a thousand pointed Rays glitter and are reflected over the place.

Later, he added, “Were it to have nymphs as well—it would be complete in everything.”

Photo via thelondonphile

After he visited a mine, Pope was inspired to decorate the grotto further with what the Twickenham museum describes as “ores, spars, mundic, stalactites, crystals, Bristol and Cornish diamonds, marbles, alabaster, snakestones and spongestone.” There were also rumors that he stole and cajoled some of these from neighboring sites, possibly defamatory in nature.

Apparently, the grotto was widely considered ridiculous. Lady Mary Wortley Montague mocked it:

Here chose the goddess her belov’d retreat,

Which Phoebus tries in vain to penetrate,

Adorn’d within with shells of small expense,

(Emblems of tinsel Rhyme and triffleing sense)

Perpetual fogs enclose the sacred Cave;

The neighbouring sinks their fragrant odours gave.

A sketch of the grotto by Samuel Lewis, 1785

Said Dr. Johnson, “A grotto is not often the wish or pleasure of an Englishman, who has more frequent need to solicit rather than exclude the sun, but Pope’s excavation was requisite as an entrance to his garden, and, as some men try to be proud of their defects, he extracted an ornament from an inconvenience, and vanity produced a grotto where necessity enforced a passage.”

But then, that’s the risk you run when you spend all your time with noted wits, I suppose. And in fact, grottoes were all the crack—indeed, Pope’s was so terrific that it apparently inspired several others.

The villa was demolished in the early nineteenth century, and nowadays the site is occupied by the modern buildings of the Radnor House School. Somewhat amazingly, the grottoes are still largely intact, if denuded of their mineral decorations, and are opened to the public a couple of times a year. Personally, I can’t imagine anything better—or, I guess, worse—to have under a high school than a vast, forbidden series of caves, underground passages, and totally hidden retreats. Anyway, if I were part of the Pope’s Grotto Preservation Trust, I might have my concerns.

Pope, however, might have approved. As he wrote near the end of his life, “Most men in years, as they are generally discouragers of youth, are like old trees, which, being past bearing themselves, will suffer no young plants to flourish beneath them.”

Books from the Met, Unsorted

Habiballah of Sava, A Stallion, 1601-6

Johannes Kip, from A Prospect of the City of London, Westminster and St. James Park, 1710

Alfred Stieglitz,

Camera Work, No. 14, 1906

Alphonse J. Liébert, Barracks Post, Place de la Bastille; Canal Tunnel and July Column, 1871

Gertrud Preiswerk, from the Bauhaus Archive

From La Caricature, a journal founded by Charles Philipon, 1830-35

Fishes, Seki Shūkō, from the Meiji period (1868–1912)

Le Jardin des Supplices, Octave-Henri-Marie Mirbeau, 1902

Manuscript Illumination with the Visitation in an Initial D, from a choir book, late nineteenth century

The Singer of Amun Nany’s Funerary Papyrus, c. 1050 BC

Artist unknown, Two Lovers in a Landscape, seventeenth century, Iranian

Yesterday, the Met released nearly four-hundred thousand images—394,253, if you’re counting—into the public domain. Verily this is a horn of digital plenty, and the museum has made it easy, even fun, to peruse: users can sort the images by artist, maker, culture, method, material, geographical location, date, era, or department. To give you a sense of the collection’s scope, I sorted it, not especially imaginatively, to show only books, which left me with an unwieldy 2,701 results—and then I dove in. Above are a few of the more striking images I found, all of them deeply miscellaneous.

There’s something enjoyable in a stochastic approach to browsing, though you’d be right to call it dilettantish. The pieces I found have nothing in common—no cultural background, no thematic unity, no philosophy or aesthetic, no chronology, not even a shared mode of production—except that they all come from books, and they were all created by, you know, the people of Earth. Imagine wandering a library in complete disarray, with no organizing principle and no particular ambition: all the context disappears, along with most notions of the cumulative, but it’s hard not to come away feeling humbled by the vastness of artistic accomplishment. If this is a cheap kind of awe, it doesn’t feel that way; a few minutes of randomized images did wonders for my sense of humanism, and I saw only an infinitesimal fraction of the collection.

You can peruse the Met’s online collection here, as purposely or as arbitrarily as you’d like. Bookmark it and return whenever you’re feeling misanthropic.

A Gadget for Lonely Hearts, and Other News

From “Slot Machine Sweethearts,“ in the May 1, 1955 issue of American Weekly; image via Gizmodo

Yesterday Dracula’s castle was for sale; today it’s Ray Bradbury’s house in Los Angeles, which is on the market for a comparatively reasonable $1.5 million. “His three-bedroom, 2,500-square-foot house, built in 1937, is painted a cheery yellow. It has three bathrooms, hardwood floors, and sits on a generously sized 9,500-square-foot lot.” This concludes today’s edition of Literary Real Estate.

The history of Red Lobster, which was recently sold to a capital equity group by its parent company, tells a hopeful but ultimately tragic tale of casual dining in postwar America.

The short story is “having a moment,” even in the UK: “In Britain we don’t have a culture of literary magazines that routinely publish short fiction. There are dozens in the US and this has helped the form to flourish.”

Curious new archeological discoveries in the British Virgin Islands: a witch’s bottle and some iron ammunition “magically used to stop violence.” Whether or not it succeeded is another story.

The 1955 equivalent of online dating: “Women would approach a machine that looked a bit like an old-school automat. The machine had photos of different men, each with a short description. She would put her coins in a slot and out would pop a more detailed note, describing just what kind of guy her potential suitor was. The woman would then take her letter to a love-agent who was able to make an introduction.”

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers