The Paris Review's Blog, page 705

May 15, 2014

The World’s Tiniest Comic Strip, and Other News

Detail from “Juana Knits the Planet,” a comic strip etched onto a single strand of human hair by the artist Claudia Puhlfürst. Image via Beautiful/Decay

St. Marks Bookshop has signed a lease on a new location: 136 East Third Street, near Avenue A. The plan is to move sometime this fall; “the owners are exploring a transition to nonprofit status.”

Philip Roth gave a talk at Yaddo yesterday—it will probably be his last. “After he gave a reading at Manhattan’s 92nd Street Y, Roth insisted that it was ‘absolutely the last appearance’ … Roth did not refer to those remarks on Wednesday. But when the Associated Press emailed his literary agent, Andrew Wylie, and asked whether Roth had given his last public talk, Wylie responded, ‘That’s his last.’”

The smallest comic strip in the world has been laser-etched onto a single strand of human hair.

A thought on International Conscientious Objectors’ day: “It occurred to me that conscientious objectors are underrepresented in the literature of war. There are many references to conscience: to soldiers who signed up but later doubted the rightness of the cause and to deserters, to those who were, by our standards, wrongly accused of cowardice. But references to actual conchies, as they were (not always affectionately) known, are thin on the ground.”

How does a work of art come to be considered great? The latest research in canon formation suggests that the “mere-exposure effect” and cumulative advantage play a larger role than intrinsic quality.

To the NSA’s growing list of offenses, we can now add “hideously outmoded graphic design, especially in PowerPoint presentations.”

May 14, 2014

Worry

Detail view of works from the exhibition ”Sophie Calle : Absence,“ Paula Cooper Gallery, New York, 2013; photo: Steven Probert; © 2014 Sophie Calle /Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York /ADAGP, Paris. Courtesy of Sophie Calle; Paula Cooper Gallery and Galerie Perrotin

Sophie Calle’s “Rachel/Monique” is currently on view at the Church of the Heavenly Rest on upper Fifth Avenue, a zip code the artist says the eponymous subject—her mother—would have appreciated, “because she always loved the Upper East Side.” The show, which wrests with the life and death of the woman most often known as Monique Sindler, is full of things she would have liked. Indeed, she liked being the subject of one of her daughter’s works. As Calle writes,

My mother liked to be the object of discussion. Her life did not appear in my work, and that annoyed her. When I set up my camera at the foot of the bed in which she lay dying—I wanted to be present to hear her last words, and was afraid that she would pass away in my absence—she exclaimed: “Finally!”

The space itself is austerely beautiful, and the show’s installation complements the neo-Gothic confines of the chapel—they’ll continue to hold services for the duration of its run. Madame Sindler’s last words were, “don’t worry” and that last one—souci—is a motif throughout, wrought in a lace hanging, written out in multicolored butterflies on a stone wall, represented by a bouquet—since the word also means marigold in French. The prettiness is disarming, but not necessarily misleading. There is no distinction made between prettiness and toughness, prettiness and the macabre, prettiness and death, even.

"Les Cils", 2013; two framed carbon prints; photo: Steven Probert. © 2014 Sophie Calle / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York /ADAGP, Paris. Courtesy of Sophie Calle; Paula Cooper Gallery and Galerie Perrotin

You sit in a pew and realize that instead of a prayer book, the rack holds the bound volumes of Mme Sindler’s selected diaries. Further into the chapel, audio plays: Kim Cattrall—a favorite of Sindler’s—giving voice to those same words. As is her wont, the artist does not spare herself; we hear her mother speak of her daughter’s “selfish arrogance.”

Calle shows us her mother’s coffin: filled with things she loved.

“Dead in a good mood” (detail), 2013; digital print and text panel; © 2014 Sophie Calle /Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York /ADAGP, Paris. Courtesy of Sophie Calle; Paula Cooper Gallery and Galerie Perrotin

Her white polka-dot dress and her red and black shoes, because that is what she chose to wear for her death.

Handfuls of sour candies, because she gorged on them.

Stuffed cows and rubber cows, because she collected cows.

Volume one of À la recherche du temps perdu by Proust, in the Pléiade edition, because she knew the first page by heart and recited it whenever she got the chance.

A postcard of Marylin Monroe with Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall, because Marilyn was her idol.

A postcard of Ava Gardner, because when people met her for the first time, that is who she claimed to be.

A Christian Lacroix silk scarf, because she was a coquette.

A book from the “Que sais-je ?” collection on Spinoza and Spinozism, because she began studying the subject a month before she died.

Mozart’s sonatas for violin and piano K. 376, K.377, K. 359, and K.360, because, at the end, Mozart was all she listened to.

A photograph of a sailboat on the Atlantic, because she loved the ocean.

Marlboro cigarettes and matches, because she smoked a lot.

Vodka, rum, and whisky, because she loved to drink.

Paper, a pencil, and an eraser, because she dreamed of writing.

A MoMA membership card, because of New York.

Photographs of the love of her life, her friends, her children, her brother, and a few lovers, because she loved them.

Photographs in which she felt she looked young and beautiful.

A photograph of a parasol pine, because it was planted at Courtonnes-les-Deux-Églises the day after her death, and it bears her name.

A few flowers—soucis (marigolds), because souci was her last word.

“Mother (The Graves, #4)”, 1990; black & white photograph; photo: Steven Probert. Courtesy of Sophie Calle; Paula Cooper Gallery and Galerie Perrotin

A tribute to her life, and loves, and that peculiar mixture of unselfconscious vanity and unselfconscious seriousness that we Americans so fetishize in French women. And yet, when I asked Calle about it at the show, she said this had not been one of her mother’s explicit wishes—“it was for us, things that reminded us of her”—and not one of the many details she had prescribed for her own funeral. Who is it for, you want to ask—I did ask—the artist or her mother? The living or the dead? But Calle doesn’t appear to concern herself with this sort of abstraction, nor with the nature of femininity, nor motherhood, nor the intersection of vanity and narcissism and art which has made her work such a lightning rod, and so curiously freeing to the viewer. Obviously, when you see the show you wonder about all of it. And you find it beautiful, in some ways you understand and in others you don’t. I asked Calle if she had taken to planning her own death; she has, a bit. You find yourself wanting to.

Calle says her mother had certain literary ambitions—vague ones. “She was too lazy to do anything about it,” says her daughter; in her diary, she bemoans the same—indeed, the journal becomes something of a monument to perceived futility. But she is a strikingly good writer. And now, a published writer—on terms that are at least somewhat her own. Similarly, because she died without fulfilling her dream of going to the Arctic, Calle went after her death—carrying in her suitcase her mother’s portrait, Chanel necklace, and diamond ring. It was nothing occult or superstitious. But then, what is superstition?

When I visited the exhibition, a few days before its formal opening, it was on the same evening that the church opened the chapel up to its parishioners; it was a full house. The minister joked it was the biggest congregation the church had attracted in a long time. Calle, who, prior to the show had never attended a service, apparently spoke from the pulpit. As her mother wrote, “My God, how brave people are in general and how hard it is for everyone to go on living.”

Strindberg’s Landscapes

Flower by the Shore, 1893

Vågen VIII, 1901

The Town, 1903

Wonderland, 1894

Tallen, 1873

The White Horse, 1892

Fact: August Strindberg could paint. Though he was always more renowned for his plays and novels, he was a prolific artist, producing more than one hundred works over the course of his life. In their brooding expressionism, his paintings were every inch as forward-thinking as his contemporaries—he counted Gauguin and Munch among his friends—and his work received enough notice that in 1894 he published an essay on his methods in a Parisian journal.

Strindberg, who died today in 1912, had an array of interests: at various points, he turned to painting, photography, telegraphy, theosophy, alchemy, and Swedenborgianism, a sect of Christianity that denied the Holy Trinity. The plenitude of his hobbies made him, depending on whom you asked, a polymath, a dilettante, or an insane person.

Strindberg tended to paint only in times of grave crisis, when he found himself too distraught to write. Maybe accordingly his landscapes are seldom sylvan, his seascapes seldom serene, and his skies seldom sunny. In 2001, Cabinet published a well-observed essay by Douglas Feuk about Strindberg’s vatic art:

In his paintings there is always a “motif”—often stormy skies, agitated waves, perhaps a lonely rock by the sea. But these landscapes or seascapes are still half-embedded in the material, like a world in the process of being created. Boundaries and differences are fluid: Air might have the same density as stone, and the rock seems mysteriously fused with the water—as if they were all but different manifestations of the same matter. In fact, the tactile surface in Strindberg's paintings is at times emphasized so much that not only does it provide an image of nature, it also, in part, gives the impression of being nature. In the painting High Sea, for example, there are sections that Strindberg has blackened with a burner, but also patches of a brownish-gray, rough structure that seem to be not so much painted as oxidized, or in other ways created by some elementary process of nature.

The Making of an American

Carl Van Vechten shaped and burnished the legend of Gertrude Stein.

Carl Van Vechten’s iconic 1935 portrait of Gertrude Stein

This year marks the centenary of the publication of Tender Buttons, Gertrude Stein’s collection of experimental still-life word portraits split into the categories of objects, food, and rooms, and which—excluding a vanity publication in 1909, which she paid for herself—was the first of Stein’s work to be published in the United States. Stein had hoped that this enigmatic little book would be her big break, the thing to convince the American people of her genius. That was not to be. Tender Buttons left critics bemused and made barely a dent on the consciousness of the wider reading public. There was no great clamor for more of her writing; Stein would have to wait another twenty years to become a household name. Nevertheless, the publication of Tender Buttons is now widely regarded as a landmark in American literary modernism, the moment when one of the most influential writers of the twentieth century first unfurled her avant-garde sensibilities before the American public.

That moment would never have arrived had it not been for the work of Stein’s most important champion, Carl Van Vechten, the man who arranged for the book’s publication. Little remembered today, Van Vechten was a pioneering arts critic, a popular author of tart, brittle novels about Manhattan’s Jazz-Age excesses, an acclaimed photographer, and a flamboyant socialite whose daring interracial cocktail parties were a defining part of Prohibition-era New York’s social scene. But his greatest legacy is as a promoter of many underappreciated American writers, artists, and performers who went on to gain canonical status. Names as diverse as Langston Hughes, Paul Robeson, and Herman Melville all felt the effects of Van Vechten’s boost. His first great cause was Gertrude Stein. He did more than anyone else to carve her legend into the edifice of the American Century, arranging publishing deals for her, photographing her, and publicizing her work, a task he continued long after her death.

Stein knew how crucial Van Vechten was to her career—not merely in the practical aspects of getting her work into print, read, and discussed, but in helping create and disseminate the mythology that surrounds her name. “I always wanted to be historical, almost from a baby on,” Stein freely admitted toward the end of her life. “Carl was one of the earliest ones that made me be certain that I was going to be.” Van Vechten and Stein were strikingly different, led wildly different lives. Hers was rooted in the domestic stability she enjoyed with her partner Alice B. Toklas; his was an exhausting whirl of binges, parties, and pansexual escapades. But they had two crucial things in common: the conviction that Gertrude Stein was an irrefutable genius and a love of mythmaking, an obsession with re-scripting reality until they became the central actors in the fantastical scenes that unfolded in their heads. When Stein played fast and loose with the facts in her memoirs, The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas, many were furious over her distortions. But Van Vechten understood that telling the literal truth about her life—or anybody else’s—was never Stein’s concern.

Van Vechten‘s self portrait, 1933

Indeed, one of those fabrications originated from an essay Van Vechten himself had written, about his experience of the remarkable Paris premiere of Le Sacre du Printemps two years earlier. That first performance of Stravinsky’s taboo-busting ballet was a defining moment in the emergence of modernism as an artistic force, and Van Vechten’s ecstatic review of it has been cited over the last century as a key eyewitness account of the event. But he never attended the first night: he had failed to get tickets and had to content himself with the second performance instead. Still, Van Vechten immediately understood the epochal significance of the occasion. He decided he would not allow such a trifling matter as the truth to prevent him from finding a place at the center of events. Gertrude Stein happened to be in the audience with Van Vechten for that second performance, and when he wrote her about his deception, he breezily reassured her that writers such as they “must only be accurate about such details in a work of fiction … I am not a bit muddled about the facts.” Stein could not have agreed more. In fact, she so approved of Van Vechten’s fiction that she embellished the story further in The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas, suggesting that the first night of Le Sacre du Printemps was also the occasion of their first meeting, and that after the performance she rushed home to write a portrait of her new acquaintance.Van Vechten and Stein had actually met in that summer of 1913 at the Parisian townhouse Stein shared with Toklas. Over the previous several months, Van Vechten, at this point a critic for the New York Times, had developed a fascination with Stein and her burgeoning legend—his friend, the shamanic Fifth Avenue salon hostess Mabel Dodge, had given him a copy of the prose poem that Stein had recently written about her, Portrait of Mabel Dodge at the Villa Curonia. Van Vechten, always drawn to novelty and exoticism, was immediately captivated by the thoroughgoing oddness of the writing, as well as the tales he had heard about the deeply unconventional woman responsible for it: a middle-aged Jewish lesbian in self-exile in France. On meeting Stein for the first time he was thrilled to discover that she was every bit as strange and marvelous as he had hoped she would be. He wrote his lover back in New York about Stein’s charisma and intelligence, as well as the delicious male nudes by Picasso that hung on her walls, some with “erect Tom-Tom’s much bigger than mine.”

* * *

After that first meeting Van Vechten’s interest in Stein swiftly morphed into an obsession. Back in New York he set himself the task of hauling her from obscurity and into the mainstream. Van Vechten’s encounter with this “cubist of letters,” as she was described in a New York Times article he wrote about her, came at a perfect moment for both of them. In the early months of 1913, many Americans got their first glimpse of artists such as Kandinsky, Matisse, Picasso, and Duchamp when the Armory Show exhibition of modern art hit New York with incendiary force. Stein’s links to these European radicals—“freaks,” as at least one American newspaper labeled them—generated much curiosity about her. Van Vechten, for his part, was at the beginning of his journey as a Manhattan tastemaker, loudly extolling the virtues of African-American theater, ragtime, and modern dancers such as Isadora Duncan. In Stein he found the perfect cause to champion: a unique artist whose mercurial work pulsated with the spirit of the age, but also one whose public image he could shape and bind himself to.

Early in February 1914, Van Vechten urged his friend and New York Times colleague Donald Evans to publish the manuscript of Tender Buttons through his new publishing house, the Claire Marie Press. A thousand copies were printed, but Evans suggested he did not expect them all to sell: “There are in America seven hundred civilized people only” Claire Marie’s brochure claimed, and it was “civilized people only” that the company said it was interested in reaching, which begs the question of whom exactly the remaining three hundred books in Tender Buttons’s print run were intended for. Of Stein’s work, Evans said that “the effect produced on the first reading is something like terror.” It was an unconventional means of promotion—but one that ensured Stein remained the very image of the aloof literary genius.

Van Vechten did a better job of bringing Stein’s writing to public attention with an article, “How to Read Gertrude Stein,” published in the fashionable arts magazine The Trend in August 1914. As the double meaning of the title suggests, it was intended to be an insider’s guide to understanding Stein’s work as well as her personality, framing Van Vechten as the man with an all-access pass to the great enigmatic genius of the age. Always a more assured critic of music than of literature, Van Vechten turned to musical referents for his most effective explanations of Stein’s writing, a tactic that countless others have followed in the intervening century. “She has really turned language into music,” he asserted; “Miss Stein drops repeated words upon your brain with the effect of Chopin’s B Minor Prelude.” The article also helped to develop and solidify Stein’s image as a guru-like figure, the sort of character Jo Davison would capture in his famous sculpture of Stein as Buddha some years later. “As a personality Gertrude Stein is unique,” Van Vechten wrote. “She is massive in physique, a Rabelaisian woman with a splendid thoughtful face; mind dominating her matter.” Stein wrote her charge to let him know that she was “very well pleased with your article about me.”

Considering Van Vechten’s hero-worshipping of Stein, it was more than a little strange for them both that over the next dozen years she remained a cult figure while his fame and importance soared—as a critic and a novelist, but most crucially as a trendsetter and the premier white promoter of the Harlem Renaissance. Success and celebrity never dampened his ardor for Stein, though, and he worked tirelessly on her behalf. In 1922 he came close to convincing Alfred A. Knopf to publish Stein’s Making of Americans, and references to her writing suffused his own literary efforts, which always attempted to frame Stein as the most important author of her generation, the light source from which all modern American writers took their nourishment. He even found opportunity to crowbar Stein into the heart of his infamous 1926 bestselling novel about the lives of African-Americans in Harlem, Nigger Heaven—a mind-blowingly insensitive title that caused every bit as much offence to black people then as it would now. The novel’s heroine is Mary Love, a young black woman with a passion for literature and European history, but who struggles to connect with what Van Vechten characterizes as her innate blackness, her “heritage of rhythm and warmth.” Accordingly, Mary develops an obsession with Gertrude Stein’s depiction of the black experience in “Melanctha,” Stein’s novella about an African-American woman from Baltimore. In fact, Mary has committed great chunks of the book to memory, and Van Vechten dedicates a page-and-a-half to her recitation of a particular passage. It is a preposterous moment in an often bizarre novel, but nothing better reflects Van Vechten’s fealty.

Van Vechten’s self portrait, 1934

Publicly and privately, Van Vechten lavished Stein’s work with praise, but in thirty-three years of friendship, Stein never returned the compliment. The mountains of letters the two swapped over the decades clearly show that Stein’s affection for Van Vechten was genuinely deep, but her faint praise for his literary work is hugely conspicuous. “What you have done is very clear and I like it” was her tepid response to Van Vechten’s novel The Blind Bow-Boy, widely thought to be his finest moment as a novelist. It was the most effusive she ever got about his work.In almost all of his friendships, Van Vechten liked to assert himself as the senior partner, a bossy proprietorial force of nature who dazzled and bulldozed with wit and charisma. Yet with Stein, whose singular genius he never doubted, he was happy to play the supplicant; at her he never lashed out or sulked as he did with so many others when he felt his specialness was being ignored. It was the reason that the two of them were able to maintain such a happy relationship for so many years. Ernest Hemingway once noted that Stein could never remain friends with anybody whom she saw as a threat. Van Vechten, a man she considered a literary lightweight and who was forever vociferously renewing his oath to her, was about as far from a threat as it was possible for her to imagine. Whenever Stein and Toklas executed one of their periodic culls of friends and groupies, Van Vechten, singing Gertrude’s praises thousands of miles away in his Manhattan bubble, avoided the blade.

* * *

By the start of the 1930s, Van Vechten, rich and bloated from what he termed “the splendid drunken twenties,” had given up writing and taken up portrait photography, spending days on end locked away from the unpleasant realities of Depression-era America surrounded by prints of his beautiful and celebrated subjects. He shot an astonishing array of noteworthy people, from George Gershwin to Georgia O’Keeffe. When The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas became an unexpected bestseller in 1933, Van Vechten became impatient to add her picture to his gallery. The suddenness of Stein’s success surprised Van Vechten as much as anyone. Almost the moment her book hit the shelves she morphed from a cult figure into a bona-fide celebrity. Fulsome reviews by prominent writers appeared everywhere, and a photograph of her taken by one of her new favorite courtiers, George Platt Lynes, graced the cover of Time. Van Vechten was thrilled for her—but bitterly jealous, too. He feared that in the frenzy of acclaim, he would be pushed from the frame at the expense of new, younger disciples.

The chance to link himself definitively to Stein in this phase of her career came in the fall of 1934, when she arrived in the United States for her triumphant homecoming lecture tour. Van Vechten was partly responsible for instigating and arranging the tour, and he provided invaluable assistance in soothing her nerves and cooing praise into her ears, reassuring her that her time had come; the American public really was crazy for her at last. He saw the proof himself as he followed Stein to many of her engagements across the country—striding around the stage with her hands in her pockets, she charmed audiences with a beguiling mixture of esotericism and folksy, homespun wisdom. To some she seemed like an adorably eccentric grandmother; to others, a radically prophetic voice. To just about everyone she was as enchanting as the woman Van Vechten had first met in Paris in 1913.

When he got the chance to photograph Stein during her tour, Van Vechten made sure he did so in a way that took her public image to a new level of grandeur. In Virginia, he shot her in front of neoclassical buildings, including the Rotunda designed by Thomas Jefferson, deliberately placing her within the pantheon of historic American heroes. Once again their shared instinct for myth creation kicked in; they both understood that this was the moment in which Gertrude Stein would achieve her immortality. Touring America, she saw the history of the nation more vividly than ever before, and she sensed her place within it. When she passed through Dayton, Ohio, she noted to Van Vechten that this was where the Wright Brothers had started out; Marion, Ohio, she learned excitedly, was Warren Harding’s hometown. From Illinois she wrote Van Vechten breathlessly, urging him to “make a pictorial history of these United States and I will write one and we will all be so happy.”

Van Vechten’s self portrait, 1935

By now, Stein’s letters to Van Vechten were routinely addressed to “Papa Woojums,” Woojums being the name of the family unit that Stein, Toklas, and Van Vechten created for themselves around this time, and in which each adopted a distinct role. While Van Vechten and Toklas were the parental figures—Toklas was “Mama Woojums”—Stein was “Baby Woojums,” not because she was helpless or vulnerable but because she was special, a treasured jewel who needed coddling and directing lest her savant genius go to waste. It was a subtle but telling reconfiguration that recognized Van Vechten’s talents and satisfied his self-image as a man of importance—yet still ensured that Stein remained the center of attention.The night before Stein sailed back to France, Van Vechten had her come over to his apartment for a final photo shoot. In his cramped makeshift studio, he positioned her in front of a crumpled and ragged Stars and Stripes, as if the flag was being blown about in a strong breeze. This was not a Gertrude Stein that had ever been seen before; not a Delphic oracle or a bohemian eccentric, but a pillar of the establishment. With a firm, unsmiling gaze and the haircut of a Roman senator, Stein had been transformed by Van Vechten’s lens into something permanent, weighty, and emphatically American, like a female addition to Mount Rushmore. Van Vechten’s mission to embed himself in Stein’s public profile was complete. The photograph has become perhaps the definitive image of Stein, and when a book of her lectures was published shortly after the tour, it was this photograph that adorned its front cover, chosen by Stein herself.

When Stein died in 1946, it was to Papa Woojums that she left the task of getting her large number of unpublished manuscripts into print, the measure of her respect and affection for him. Despite fearing that “Gertrude had bitten off more than I could easily chew,” Van Vechten faithfully undertook his duty. Within a little more than a decade, Stein’s complete works had been published.

Edward White is the author of The Tastemaker: Carl Van Vechten and the Birth of Modern America. White studied European and American history at Mansfield College, Oxford, and Goldsmiths College, London. Since 2005 he has worked in the British television industry, including two years at the BBC, devising programs in its arts and history departments. He is a contributor to The Times Literary Supplement. He lives in London.

Vancouver in Neon, and Other News

Photo: Vancouver Public Library

“University presses don’t just publish books: they keep books in print and rescue out-of-print books from obscurity … But the digital age complicates and threatens the mission of the country’s approximately 100 university presses. Ellen Faran, who has an MBA from Harvard and is the director of MIT Press, recently told Harvard Magazine: ‘I like doing things that are impossible, and there’s nothing more impossible than university-press publishing.’”

Almost every book set in Africa seems to have the same cover art: “an acacia tree, an orange sunset over the veld, or both … the covers of most novels ‘about Africa’ seem to have been designed by someone whose principal idea of the continent comes from The Lion King.” (Plug: Norman Rush’s Whites, Mating, and Mortals, all set in Botswana and all excellent, have acacia-free covers.)

Why have we ceased to eat swans? “Often served at feasts, roast swan was a favored dish in the courts of Henry VIII and Elizabeth I, particularly when skinned and redressed in its feathers and served with a yellow pepper sauce.”

Midcentury Vancouver “had the second-most neon signs per capita on the globe, after Shanghai … neon signs fell victim to a ‘visual purity crusade’ in the 1960s. Critics thought that the neon cheapened the look of the streets, and obscured Vancouver’s natural beauty. (‘We’re being led by the nose into a hideous jungle of signs,’ wrote a critic in the Vancouver Sun—a newspaper whose headquarters was prominently bedecked in neon—in 1966. ‘They’re outsized, outlandish, and outrageous.’)”

Remembering the artist Richard Hamilton: “One evening, Hamilton told me he had developed a method for photographing the toaster prints, so as not to interrupt the surface with his own reflection: he would move his tripod off to one side to take the picture, later returning each image to its original orientation using Photoshop. Today, when I think of Hamilton, I think of that illusive process: the mirrored surface, the lens’s sidelong glance, the almost complete disappearance of the artist from the work—like a hotel lobby that someone has just walked out of.”

May 13, 2014

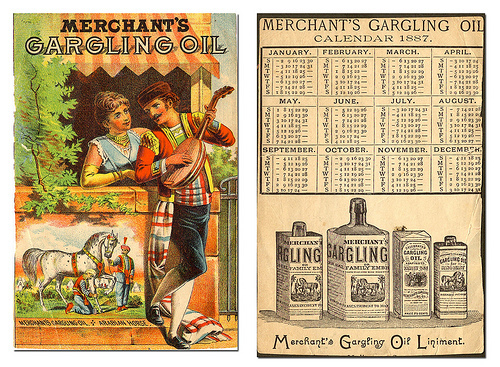

For Man and Beast

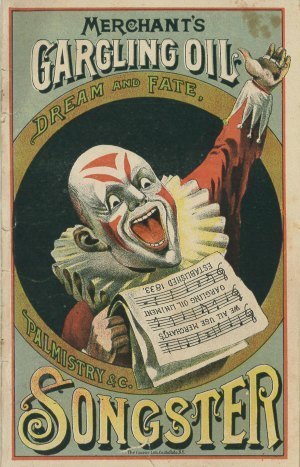

The Internet will lead a traveler down strange byways. I no longer remember where I started, but here I stand, at the end of a circuitous and occasionally treacherous path, suddenly full of facts about Merchant’s Gargling Oil. Let’s not linger on how I got here. I’m as confused as you are.

Merchant’s Gargling Oil is “a Liniment for Man and Beast,” a catch-all salve first produced by George W. Merchant, a druggist, in 1833. Who can guess what compelled Merchant to whip up that first batch of petroleum, soap, ammonia water, oil of amber, iodine tincture, benzine and water? Who still can say what frame of mind found him slathering this unguent on his skin? And who, at last, will stand up and tell me why Merchant saw fit to market his concoction as “Gargling Oil” even though he intended it primarily for external use?

These mysteries belong to the ages. More certainly, we can say that Merchant’s Gargling Oil was intended to treat burns, scalds, rheumatism, flesh wounds, sprains, bruises, lame back, hemorrhoids or piles, toothache, sore throat, chilblains, and chapped hands; that the Merchant business was successful enough to produce a promotional line of almanacs, songbooks (“songsters”), and stamps; and that horses were evidently crazy for the stuff. Beyond that, this Gargling Oil is awash in contradictions. For instance, despite its external uses, you could, if you wanted to, take it internally:

Merchant’s Gargling Oil is a diffusible stimulant and carminative. It can be taken internally when such a remedy is indicated, and is a good substitute for pain killers, cordials and anodynes. For Cramps or Spasms of the Stomach, Colic, Asthma, or Internal Pain, the dose may be from fifteen to twenty drops, on sugar, or mixed with syrup in any convenient form, and repeated at intervals of three to six hours.

Even though it was marketed as suitable “for Man and Beast,” it was sold in two separate versions—yellow for animals, white for people—but if a man found himself under particular duress, he could simply go ahead and use the beast version. “It will stain and discolor the skin, but not permanently,” the packaging noted.

The Gargling Oil could be found on shelves, along with other fine Merchant’s products, until 1928, when the Merchant factory in Lockport, New York, caught fire and burned to the ground. Today it leaves behind a formidable body of advertisements and miscellanea, many of which bear this curious slogan, attributed to an ape:

If I am Darwin’s grandpapa,

It follows don’t you see,

That what is good for man and beast,

Is doubly good for me.

I don’t see how this follows. But then, I don’t even recall how I got here.

Three Short Stories About Deviled Eggs

Photo: JeffreyW, via Flickr

I.

Once, when I was very young and foolish, I threw a party, the refreshments for which consisted exclusively of deviled eggs. Mind you, there was some variety: I made deviled eggs with bacon, deviled eggs with horseradish, deviled eggs with pickle relish, even a highly dubious specimen involving salmon roe. Each one was topped with something different—paprika, chopped chives, green peppercorns—and boasted a small sign. Keep in mind that this was many years ago, before we knew smoked paprika, let alone eggs stuffed with smoked trout or sriracha, but I tried. (I had also not yet discovered Durkee Famous Sauce, which would revolutionize my egg-deviling.) On this long-ago day, in my innocence, I boiled and mashed and stuffed and garnished for hours, and at the end it seemed to me that I had never seen anything so beautiful as that table full of deviled eggs. No one else was that into it. Even people who like deviled eggs seemed to understand instinctively that half their power came from their preciousness. I had to eat so many that I was sick, but I still loved them. The party was a failure.

II.

The single worst deviled egg I’ve ever eaten was in Maine in the summer of 2008. By this time I had eaten my way around town, having consumed all manner of deviled eggs—some good, some bad—but never before or since had I encountered an abomination like this. Here was what was in the deviled egg: egg yolk and horseradish. No salt, so mayonnaise. I had not known such degradation was possible. I had to throw the balance into a garbage can set under a pine tree. We had accidentally decided to picnic on a gay beach, and when I went to throw the egg away, I came upon a man giving another man a blow job in the woods.

III.

One day not long ago I was visiting my parents. Life had changed; suddenly deviled eggs were everywhere—at tapas bars, in sepia-toned Brooklyn whiskey joints. I, too, was jaded; I had taken to cutting my eggs horizontally, across the equator, and serving them this way. One one occasion, I even deviled some pheasant eggs. This was what we had come to.

My parents declared that, come Saturday morning, we would all go to tag sales. I said I didn’t need anything in the world—except, perhaps, an old-fashioned deviled-egg plate, the perimeter scored with egg-shaped depressions. And then, at the last sale of the day, we found one: it is cut glass, very heavy, and holds fifteen deviled eggs. I am not sure what to put in the center of the dish. It cost me one dollar.

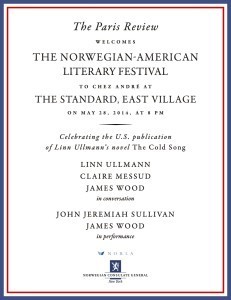

The Norwegian-American Literary Festival Comes to New York

For the last two years, a small group of American writers and critics has convened in Oslo for a series of informal lectures, interviews, and discussions. Dubbed the Norwegian-American Literary Festival, this unlikely gathering has introduced packed houses to the likes of Donald Antrim, Elif Batuman, Lydia Davis, Sam Lipsyte, and John Jeremiah Sullivan, and—on the American side—has helped spread word of contemporary Norwegian masters including Karl Ove Knausgaard, Joachim Trier, and Turbonegro.

For the last two years, a small group of American writers and critics has convened in Oslo for a series of informal lectures, interviews, and discussions. Dubbed the Norwegian-American Literary Festival, this unlikely gathering has introduced packed houses to the likes of Donald Antrim, Elif Batuman, Lydia Davis, Sam Lipsyte, and John Jeremiah Sullivan, and—on the American side—has helped spread word of contemporary Norwegian masters including Karl Ove Knausgaard, Joachim Trier, and Turbonegro.

Now, for one night only, The Paris Review is proud to welcome the Norwegian-American Literary Festival to New York.

On Wednesday, May 28, join us at Chez André in the East Village to hear Claire Messud and James Wood in conversation with the Norwegian novelist Linn Ullmann, followed by rare musical performances by James Wood and John Jeremiah Sullivan. Liquid refreshments will be served.

Admission is free, but space is limited—reserve tickets for you and one guest now by e-mailing us at rsvpNALF@theparisreview.org.

Snapping, Humming, Buzzing, Banging: Remembering Alan Splet

Millions of Americans heard the name Alan Splet (1940–1994) for the first time as a punch line on television. The occasion was the 1980 Academy Awards, where his sound design the previous year, on Carroll Ballard’s The Black Stallion, had earned him a special Oscar. Citing prior commitments, Splet did not attend the ceremony. When the presenter held up the statuette and the honoree failed to appear to accept it, the evening’s host, Johnny Carson, turned this perceived snub of Hollywood taste back on the truant. “It always happens,” he deadpanned to the audience, “first George C. Scott doesn’t show, then Marlon Brando, and now Alan Splet.”

Splet deserves better. He was no joke. In fact, to an exclusive circle of independent filmmakers who know how much his collages of sound and musical refinement added to their movies from the late seventies to the early nineties, his name is still invoked with an affection verging on awe. Tributes can be found on YouTube from Ballard, Peter Weir, Caleb Deschanel, and Philip Kaufman, with whom Splet collaborated on three films. Splet’s sound design and editing on The Unbearable Likeness of Being (1988) ranks among the most haunting and sophisticated of its day—or any day. Leoš Janáček’s string and piano music is as ravishing as Sven Nykvist’s cinematography, underlining not only the distinctly tart Czech melancholia of the novel, but also serving, notes Kaufman, to “supplant Kundera’s voice as the narrator and give the film its drive.”

No filmmaker in those years bonded more intensely or productively with Splet than David Lynch. The two met in 1970 when the writer-director needed a sound track for his short film The Grandmother. (Splet was then employed at a Philadelphia industrial film company, having bailed on a career in accounting.)

With no money to foster the visions Lynch had in his uncompromising young head, the pair spent twelve-hour days inventing effects on the cheap, recording human mewls and gurgles and hissing machine-made sounds. Not until their concoctions matched the images on the editing table and the pairing created an elusive “mood” (a key term for Lynch) were they satisfied. Thereafter, until Splet’s death in 1994, he partnered with Lynch on every major film project, those that were completed (Elephant Man, Dune, Blue Velvet, Wild at Heart) and those that weren’t (Ronnie Rocket).

In the opinion of some, however, their masterpiece of “audio surrealism” remains Eraserhead. Begun in Philadelphia and finished in Los Angeles, its atmosphere is as marked by the sooty poverty of the filmmakers as The Grandmother had been. It was during this time (around 1973) that Lynch, who could not afford paints, did two meticulous drawings in ballpoint pen: a crucifixion, in a style that combines Mattias Grünewald and Francis Bacon, and a resurrection, now lost. Hoping to raise money to finish the film, they had prints made, an enterprise that was rewarded with total failure.

That despondent result did not prevent Splet from buying the original of the crucifixion drawing, framing it, and hanging it over the mantelpiece in the Berkeley, California, house where he lived with his wife and fellow sonic explorer, Ann Kroeber. (Planning to auction it off, she has interviewed Lynch on film about the background of the piece and his friendship with her husband—watch an excerpt of that film below.)

My only relationship with Splet was over the phone, while I was writing several articles about Lynch in the early 1990s, as Twin Peaks was altering the sensory pathways of America’s network-television audience. I proposed a piece about Lynch’s unique conception of sound and image to the Village Voice; the editors liked what I wrote and then decided not to run it because they judged too many adulatory words were being published at the time about Lynch. (In addition to his TV and film projects, he was exhibiting his art at the Leo Castelli Gallery and teaming up with composer Angelo Badalamenti on a symphony at BAM.)

In asking the editors of The Paris Review if they might publish an article written more than twenty years ago, I couched the appeal as a way to revive interest in Splet. He died much too young, left an audible signature on every film he touched, and should be remembered as an artist of stubborn integrity, not as the butt of a Hollywood joke.

“It’s too bad Ronnie Rocket never got made,” says Alan R. Splet about one of several David Lynch scripts still tied to Dino De Laurentiis’s bankruptcy. “There was lots of heavy electricity, amplified power in the script. It went back more toward the Eraserhead side of things. Maybe David feels he’s moved beyond that.”

Splet starts to laugh nervously, almost maniacally, as he recites all the kinds of electricity he could produce if called upon by Lynch. “There’s snapping, humming, buzzing, banging, like lightning, shrieking, squealing …”

As the sound engineer who has worked with Lynch since The Grandmother, their AFI student film completed in 1969, Splet saves up noises that he thinks his friend will like and sends them along on cassettes for Lynch to use or enjoy.

“I remember for Dune I collected a bunch of things and then I flew down to Mexico City,” he says. “One Sunday we set up a Nagra in his apartment and listened to sounds all afternoon. I just gave David a heavy arcing sound to use behind the logo on Twin Peaks. I haven’t heard what he’s done to it, but it’s the kind of thing he likes. He tends to go for power effects.”

No American filmmaker loves industrial sounds more than David Lynch. Eraserhead, Elephant Man, and Dune are filled with nostalgia for nineteenth-century steam and sparks—everything from the brute pounding of a drill press to the creaks and sighs of old elevator motors to the mood of a power plants on a cold night to the whirr of cranes and pulleys and winches to household short-outs. His films echo with the throbs and groans of doomed technology. Or, as he rather inadequately explains his reverence for this kind of sonic material, “The idea of man working with nature is just thrilling to me. I’d rather go to a factory any day than walk in the woods.”

This wide-eyed ability to find a narrative vein in lonely places makes Lynch the Edward Hopper of American film. The power station in Eraserhead seems to be in the movie mainly because he likes how it looks and sounds: fenced in, deserted, humming, the behemoth that feeds the city from the dark side of town. But it also serves to dwarf and humiliate the main character; it’s another menacing, noisy presence in the urban hellhole that deepens and mocks his passivity.

People tend to remember and talk about Lynch’s potent imagery: the pathetic, mummified baby; oozing chickens; the hypodermic draining of Baron Harkonnen’s puss-filled carbuncles; a close-up of ants and an ear in the grass.

But it’s the eerie sound tracks, off-kilter dialogue, and the underwater pace of events that lifts his work beyond the gross-out, horror genre and into the realm of experimental film. Sound for Lynch is the key to mood; and mood, if not everything for Lynch, is at least half of the equation.

In Bobby Vinton’s song “Blue Velvet,” Lynch found a key to many of the elements in the movie: its lush color scheme, ballad tempo, unhealthy dwelling on the past, and obsessive relationship between a man and a woman. This Golden Oldie, the slow dance at many a senior prom in the early sixties, also turns out to be a psychotic’s favorite material.

Working for Lynch seems to involve floating suggestions in front of him until he locks on to something he likes. Starting with atmosphere, with the hush of suburban streets in Blue Velvet or the emptiness of high school corridors in Twin Peaks, he tests situations and characters against some deep, inner tuning fork.

On location searches for Wild at Heart in New Orleans with his production designer Patricia Norris, he would stop at the sound of water dripping on tin in a back alley and say, “We have to come back and record that.” He wears headphones for almost every shot, sometimes not even listening to the dialogue track but to some piece of music that he thinks describes the feeling of a scene. Often, it’s not even the music he’ll use in the film; it’s as though sound helps him see what he wants on the screen more clearly.

He is open to all kinds of input from actors—Kyle MacLachlan’s chicken walk in Blue Velvet was his own idea—but Lynch knows exactly what he wants. The opposite of an eclectic temper, he can be maddeningly specific for reasons that only he needs to understand. On Eraserhead Lynch drew two telephone wires for Splet, each line indicating four or five pitches he wanted. It was Splet’s job to go find these sounds. When he played Lynch some Fats Waller pipe-organ numbers as possible sound-track material, the director honed in immediately. “I never listened to any other kind of music for the film,” he says. “I knew that was it.”

To some extent, Lynch stands on the shoulders of his older Hollywood colleagues. The generation of American filmmakers who came of age in the seventies—Coppola, Altman, Allen, Scorsese, De Palma, Lucas, Spielberg—had an unusual regard for the art of music and sound. The lush orchestral scoring in the Corleone gangster opera, the antiheroic musical New York, New York, Allen and Spielberg flexing their muscles by refusing to use music that would sell to the kids—these looked toward golden-age Hollywood traditions of sound craft, while the multivoice sound track of Nashville brought movie dialogue up to acid-head standards established by Sgt. Pepper’s and Firesign Theatre.

The Conversation and Blow-Out—perhaps the only two dramatic films ever made about sound technicians—use eavesdropping, not voyeurism, as the trigger for political paranoia, while Apocalypse Now transformed Vietnam from a boxed-in, monaural war into a Dolby experience that gives the Doors the last word. Lucas serves the needs of all these filmmakers, having turned his techno-fetishism into the thriving business THX, which will install state-of-the-art sound systems in your local theater for a small fortune.

But the Lynch-Splet sound track for Eraserhead is of another order. The electric hum; soughing wind; ceaseless, industrial roar; and the array of noises that issue from the baby (chokes, coughs, gasps, gurgles, spit-ups, and that steady, inconsolable cry) are the product of a mind wired to sixties art experiments rather than Hollywood movies. To magnify his fantastic, minimalist storyline, Lynch treats sound as plastic material, in the spirit of Varèse, Cage, or Dziga Vertov’s Enthusiasm. The closeness and exaggeration of household noise adds to the oppression that squeezes the couple from beyond the walls. Fats Waller reverberates as though Lynch-Splet had patched into a broadcast from a Depression-era skating rink. The sound is chilling, ancient, faraway, as though time itself had physically decayed.

Lynch had a motto in his early days: Picture Dictates Sound. But it also worked the other way around. As Splet remembers it, “We would take sounds, slow them down, and these would evoke images for David.” Both are sworn to secrecy about the source of the baby’s rich vocabulary. “Yeah, he’s a busy guy,” is about all anyone can get out of Lynch; Splet admits only that “all the baby’s sounds were organic.”

As he made bigger-budget films that told real stories—Elephant Man, Dune, Blue Velvet—Lynch devised less extravagant sound tracks. Apart from Brian Eno’s prophesy theme and the industrial noises on Baron Harkonnen’s planet—the leaking steam, clanging iron doors, thump of pumps, some good radio static—Dune is pretty dull, considering the budget. The music by Toto is not even wallpaper. Blue Velvet is more hyper-real than Eraserhead is surreal. Lynch used Splet’s foghorns and train whistles to give Dorothy Vallens’s apartment block a lonesome, ordinary dread. The thinness of her wooden door when knocked on lets us know how poorly the bosses at the Slow Club pay their singer.

That movie also began Lynch’s association with composer Angelo Badalamenti, who coached Isabella Rossellini on her vocals. The song “Mysteries of Love,” which closes the film on a blissful note, was written by Badalamenti after Lynch brought him the fragment of a lyric and some vague instructions. “He asked for something beautiful, cosmic, floating,” says Badalamenti. “He just talks about moods. He wanted a Mideastern flavor on Blue Velvet, to make the streets feel foreign. He likes Shostakovich and he asked if I could write like that. That’s how we do everything.”

Badalamenti, who scored Lynch’s famous public-service commercial for New York City’s campaign against rats and his ad for Opium perfume (as well as Nightmare on Elm Street 3 and National Lampoon’s Christmas Vacation) has written about a half dozen motifs for the characters on Twin Peaks. The score has a generic, synthesized, Wagner-on-quaaludes sound. “David asked if I could do a cool jazz but like a cool, dark jazz slightly off-center,” he says. (Those who spend time with Lynch often end up talking like him.)

“Industrial Symphony No. 1,” the operatic piece they did last year for BAM, was a return to full-blown sound experiments. The score included chain saws, sirens, electrical eruptions, power generators, and a phone call. The stage might have been an X-ray of Lynch’s soul: one half-naked woman danced on top of an abandoned car and up and around a power tower while another floated on a trapeze above the scene in a chiffon dress, singing about love and darkness.

Much of this music came from Floating into the Night, the album sung by Julie Cruise to words by Lynch, which might be one of the slowest pop records ever made. Cruise was the woman on the trapeze, and she does a number in a roadhouse in Twin Peaks. Most of the lyrics approach self-parody—they’re dark, vague, full of longing for love—and Cruise whispers and coos more than she sings. It’s mood music taken to extremes: there’s not much to it except teenage morbidity, creepy because it’s completely heartfelt. Like so much of Lynch’s work, it taps into adolescent eroticism rather than anything adult. But she says, “I’m not sure I’ve had that experience yet.”

Asked to trace the course of his career, Lynch sums it up this way: “I used to like darkness and low-frequency sounds, and now I tend to go for lighter things and high-frequency sounds.”

Lynch is alone among American filmmakers in his ability to maintain access to Hollywood and European cash while also making works that are almost avant-garde in their deep, personal abstraction. Despite his often inarticulate sense of how things should look and sound, he creates towns like Lumberton and Twin Peaks that most of us won’t soon forget. The multiple storylines of the new television series, the dozens of characters whose mouths he fills with kooky dialogue, seem less important to him than the town itself, which is located somewhere television has never been before.

His new film Wild at Heart, a road picture scheduled to be released in the fall, has all kinds of music, from speed metal to Spanish-tinged slow blues, and sound cues abound throughout the script. It reads as darkly as anything he has ever done; and it opens with a spectacular motorcycle accident that hits a wide range of shattering metal-on-metal, metal-on-pavement, flesh-against-glass frequencies.

On the first page Lynch describes what he wants to hear on the sound track: “The motorcycle bounces off a black ’66 Chevrolet and makes a sound like the end of the world.” We’ll know soon what the apocalypse sounds like in David Lynch’s head.

Richard B. Woodward is an arts critic in New York City.

The (Microscopic) Tracks of My Tears, and Other News

Tears of grief, photo © Rose-Lynn Fisher, courtesy of the artist and Craig Krull Gallery, Santa Monica, CA; image via Smithsonian Magazine

Up for auction: an edition of The Importance of Being Earnest, warmly inscribed by one Oscar Wilde himself to Major James Nelson, the prison governor who permitted Wilde access to books during his stint at Reading Gaol in May 1895. “A trivial recognition of a great and noble kindness,” the inscription reads.

All this month, New York’s Elizabeth Street Garden celebrates the life and work of Robert Walser. “Much of his work and philosophies rest on the quiet magic and personal fulfillment of walking; the urban experience is full of such walks, and this is often how people discover Elizabeth Street Garden.”

“Was Andrew Wyeth so celebrated because he was so misunderstood, or did it work the other way around? His reputation seems ill-fitting, whether you consider him one of the great American painters of the last century, as many laymen and a few professionals do, or a kitsch monger and conman, as many more professionals and a few sniffy, wised-up laymen do.”

In a new project called “Topography of Tears,” the photographer Rose-Lynn Fisher puts dried human tears under the microscope. She collected more than one hundred tears: tears of joy, tears of grief, onion tears, basal tears …

Many of our nation’s ice-cream trucks—though not, fortunately, Mister Softee—are blaring a jingle based on one of the most racist songs in American history.

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers