The Paris Review's Blog, page 709

May 2, 2014

What We’re Loving: Spiders, Spaces, Stinkin’-Hot Nights

An exhibition image from Marc Yankus’s “The Space Between,” at ClampArt.

If I had to teach a class on the Framing Device, the first thing I’d make them read is Jeremias Gotthelf’s 1842 novella The Black Spider, recently published in a new and (to this non-German-reader) magical translation by Susan Bernofsky. The opening scene is a christening in the Swiss countryside: idyllic, sentimental, lovingly detailed. Then one of the guests notices a strange blackened post in the house where the festivities are held, an old man begins to tell the story of how it got there … and in no time things have gotten very weird indeed, and they continue weird even when the story ends, the idyll stained by the past. A fairytale for grownups, an early horror story, an allegory of the Black Death or of sin—however you read it, it has the deep logic of a dream. —Lorin Stein

Sometimes I’ll Google some nouns with a writer’s name, hoping to discover that said writer has miraculously published a piece about said nouns. This usually doesn’t work out for me—zero results for “Norman Rush + Botswana + heavy-metal leather subculture,” and zero more for “Jonathan Lethem + Larry Levan + Paradise Garage + disco”—but lightning can strike, as it did with “Richard Ben Cramer + baseball + Baltimore.” That led me to Cramer’s “A Native Son’s Thoughts (Many of Them Heretical) About Baltimore (Which Isn’t What It Used to Be), Baseball (Which Isn’t What It Used to Be) and the Steadfast Perfection of Cal Ripken Jr. (Which Is Ever Unchanging, Fairly Complicated and Truly Something to Behold),” published in Sports Illustrated circa 1995. Hot dog! As its forty-four-word title indicates, this piece has it all. There’s baseball, which, for reasons that remain unclear, I’ve begun to enjoy watching; there’s Baltimore, where I grew up; and there’s the vigorous prose from Cramer, whose masterpiece on the 1988 election, What It Takes, I’ve just finished, thus creating a void that can only be filled with more Cramer. When I read the first clause (“It’s a stinkin’-hot night at the ballpark”) I knew I was safe for a little while longer. —Dan Piepenbring

“The Space Between,” Marc Yankus’s show at Clamp Art, is on now through May 17; it reveals a new side of the artist. His earlier images explored his love of color washes and blurred shapes—photography that sometimes looked as though it had been printed on a wet surface. With this new body of work, Yankus has written a love letter to the stonemasons, bricklayers, and architects of an ever-evolving New York City landscape. The detail captured in these photographs is unreal and meditative; he’s shot these monumental buildings sometimes at great heights and always from their best angles. A master of minute detail, Yankus invites us to study the individual bricks right down to the fine cement layers that seal them together. Though people are ever-present in these works, there’s not a soul to be found. It lends a ghostly beauty to these prints, making it exceedingly difficult to pick a favorite. —Charlotte Strick

I’ve been reading Adam Shatz’s vivid remembrance of the journalist and historian Patrick Seale, who died last month. Seale wrote the two best books on modern Syrian politics, in English or any other language. The Ba’athists in Damascus trusted him and the Western spymasters learned from him. And what a time it was for foreign correspondents, especially if you lived in Beirut. As Shatz writes, “It was the Mad Men era of Middle East reporting, a time of high living and high-stakes intrigue … The correspondent’s calendar was marked by revolutionary conspiracies; many were first reported as rumors, sometimes overheard at the bar of the St. George Hotel, where spies, arms dealers, diplomats and other adventurers gathered at the end of the day.” —Robyn Creswell

A Woman in Berlin, a diary of the final days of Nazi Berlin, and its fall to the Russian army of 1945, by an anonymous German woman, tells a story that is sometimes left out of World War Two narratives: the horror that Hitler inflicted on ordinary German people. All the violent savagery that German troops dealt out to their “inferior” Slavic neighbors is returned tenfold as Russian troops rape and pillage their way through what is left of German homes, answering Hitler’s scorched earth policy with their own form of angry nihilism. The author, whoever she is, wrote the diary for her husband, so he could understand what had happened after their lives had been rebuilt, though their marriage didn’t survive their different experiences of the war. The language in the translation by Philip Boehm is beautiful, and the book is not nearly as depressing as I’ve made it seem. —Anna Heyward

Every day the poet Gilberto Owen weighed himself at the 116th Street subway station, and every day his weight was always less. “I suppose that’s what illness is like: you stand down and are replaced by the ghost of yourself.” This is just one of the three stories that weaves its way through Valeria Luiselli’s masterful Faces in the Crowd, a novel in which people die many times just to wake up right where they left off; people come and go by the whim of a pen tip; and Ezra Pound stands on a platform for a train he’ll never board. —Justin Alvarez

On Afghanistan’s border, Pashtun women sing Landays—couplets that end with the sound “ma” or “na,” with nine syllables on the first line and thirteen on the second. Anonymity is key to their survival and their tradition; these poems are supposed to belong to no woman and every woman. We always see Afghan women portrayed as weepy or silently suffering; here they chortle, roll their eyes, bitch, and suffer on their own terms. “Making love to an old man / is like fucking a shriveled cornstalk black with mold.” Black and white photos contextualize these “scraps of song” with uncomfortable clarity. I especially like one of fluffy black goats sniffing around a ruin that could have been ruined by time or drones or both. —Nikkitha Bakshani

So Green

Semik, a Russian lubok from the nineteenth century.

You never really get over secret childish chauvinism about your birthday month. At least, I never did. In my mind, May will always be the best month of the year; emerald, the best birthstone; and lily-of-the-valley, the finest flower. (On the subject of Taurus, I am agnostic; I have always resented the fact that we are supposed to be stubbornly rolling around in velvet or something.)

Because my own birthday falls so early in the month, and because I was definitely on the “preciousness” spectrum, my eighth birthday had a May Day theme. I knew little of the day’s ancient roots or traditional practices, let alone its adoption by the labor movement. But I had a Tasha Tudor book called Around the Year that featured young girls, flower garlands, and a beribboned maypole, and I was sold.

For my birthday, we gathered flowers, made May baskets, and left them on neighbors’ doorsteps while we hid nearby. They must have been very confused. Although my parties were generally homespun affairs, on this occasion my mom hired a gentleman in Renaissance dress who played a hurdy-gurdy while we danced around a maypole that a friend’s dad had constructed from a birch trunk. We were all terrified of the hurdy-gurdy man, and kept our distance.

“The Merry Month of May” was written in 1599 by the prolific playwright and pamphleteer Thomas Dekker. Dekker was widely considered a wastrel and a hack—Ben Jonson dismissively called him a “dresser of plays about town”—and he spent seven years in debtors’ prison. But his pastoral is one of the most enduring paeans to the fifth month. Somehow I doubt it was in the hurdy-gurdy man’s repertoire.

O, the month of May, the merry month of May,

So frolic, so gay, and so green, so green, so green!

O, and then did I unto my true love say,

Sweet Peg, thou shalt be my Summer’s Queen.

Now the nightingale, the pretty nightingale,

The sweetest singer in all the forest quire,

Entreats thee, sweet Peggy, to hear thy true love’s tale:

Lo, yonder she sitteth, her breast against a brier.

But O, I spy the cuckoo, the cuckoo, the cuckoo;

See where she sitteth; come away, my joy:

Come away, I prithee, I do not like the cuckoo

Should sing where my Peggy and I kiss and toy.

O, the month of May, the merry month of May,

So frolic, so gay, and so green, so green, so green;

And then did I unto my true love say,

Sweet Peg, thou shalt be my Summer’s Queen.

The Dark Galleries

Portrait of Ballin Mundson; Gilda (Charles Vidor, Columbia, 1946)

Portrait of Mr. Antony, Strangers on a Train (Alfred Hitchcock, Warner Brothers, 1951, painted by Ted Haworth)

Portrait of Azeals Van Ryn, Dragonwyck (Joseph L. Mankiewicz, Twentieth Century Fox, 1946)

Portrait of Jennie Appleton, Portrait of Jennie (William Dieterle, Selznick Productions, 1948, painted by Robert Brackman)

Portrait of Pandora Reynolds, Pandora and the Flying Dutchman (Albert Lewin, MGM, 1951, painted by Ferdie Bellan)

Portrait of Matilda Frazier, The Unsuspected (Michael Curtiz, Warner Brothers, 1947)

Portrait of an Unknown Woman, The Dark Corner (Henry Hathaway, Twentieth Century Fox, 1946)

Portrait of Alice Reed, The Woman in the Window (Fritz Lang, International Pictures, 1944)

Second Portrait of Sally Morton, The Two Mrs. Carrolls (Peter Godfrey, 1947, Warner Brothers, painted by John Decker)

Portrait of a Murderer, The Big Clock (John Farrow, Paramount, 1948)

The noir and gothic films of the forties and fifties often feature beguiling portraits, paintings that possess a strange power; they inspire acts of fraud, forgery, theft, murder, and obsession. Think of The Woman in the Window, Laura, or Vertigo: in the first few scenes of each film, a kind of investigator becomes enraptured with a woman who also appears in a painted portrait—and, often, the twist reveals that she’s not who she seems to be. In Laura, the portrait itself stands in for the woman who’s supposedly disappeared, as Detective Mark McPherson investigates the crime—until, that is, Laura walks into her old apartment, where the detective is sleeping beneath the portrait that so intrigued him. The portrait serves as a kind of false look, or false double, that only can really be appreciated on film.

The artists who created these portraits—usually just large-scale photographs slapped with varnish—typically went uncredited; today most of the portraits themselves have gone missing. In The Dark Galleries: A Museum Guide to Painted Portraits in Film Noir Gothic Melodramas and Ghost Stories of the 1940s and 1950s, the art and film historians Steven Jacobs and Lisa Colpaert have created a guide to an imaginary gallery of these imaginary paintings, which often took imaginary people as their subjects.

What interested Jacobs most was not so much the portraits themselves, but the roles they played in their respective films: they reflected how people thought they should behave in front of pieces of art. The plots of these films often came from classic literature or standard noir fare, but it was film techniques that brought the paintings into more direct conversation with the narrative.

Jacobs noticed that cinematographers used editing methods like reverse-shot patterns to make it appear that the portrait was looking back, as in Laura—in which a portrait has to stand in for the missing character in McPherson’s mind. They also used eye-line matches between the portraits and characters in tracking shots—or special effects with color and sound. For example, Bernard Herrmann’s well-known refrain “Carlotta’s Portrait” plays as Scottie follows Madeleine into an art gallery, where she stares at a portrait of a woman eerily similar to her—an eeriness conveyed by the camera’s glide between their shared features, to the sound of an unsettling score.

Jacobs has also published a book of the real and imaginary architecture in Alfred Hitchcock’s films. His book with Colpaert, designed to resemble a forties- or fifties–era catalog, offers an encyclopedic collection of portraits, organized by categories like the “Gallery of Matriarchs and Female Ancestors” (Lady Caroline de Winter in Rebecca), a “Gallery of Ghosts” (Carlotta Valdes from Vertigo), and the “Gallery of Dying Portraits” (Norma Desmond in Sunset Boulevard). There’s also an illustrated survey of noir and gothic art, devoted to film stills of the made-up artists, museums, galleries, critics, and connoisseurs from these movies—and shots of “Paintings Concealing Safes” or “Modern Art in the Homes of Criminals.”

Even though the plots of the films hinge on these artworks, surprisingly little information exists about many of them—which is all the more surprising in light of the fact that some of the artists who painted them were certifiably famous. Of the more than ninety works in the book, only one is credited to an artist: to Ivan Albright, who painted the titular portrait for The Picture of Dorian Gray. Man Ray painted the portraits in Pandora and the Flying Dutchman, but those works can no longer be found. He was credited only as “still photographer” for the film. Similarly, Robert Brackman received acknowledgement for his work on Portrait of Jennie, but there’s no specific credit for his portrait.

Of the works included in the book, Jacobs estimates that only about five exist today. Two are at museums: Albright’s grotesque Picture of Dorian Grey is at the Art Institute of Chicago and Brackman’s Portrait of Jennie can be found at the Norton Simon Museum in Pasadena, California. The portrait by Albert Ferren for Vertigo is owned by one of the restorers of the film, and the Decker paintings from Scarlett Street have whereabouts unknown. One wonders what an exhibition of these paintings would look like in real life, but then again, that might spoil the fun: as The Dark Galleries suggests, most of the allure in these paintings derives from their roles in imaginary spaces.

Ali Pechman is a writer living in New York City. She has written about art for Artforum, Artnews, and The Awl, among others.

Snub Your Suitors the Brontë Way, and Other News

She knew how to say no. Charlottë Bronte, painted by Evert A. Duyckinck, based on a drawing by George Richmond, 1873.

Need to reject a marriage proposal or two? Take a page from Charlotte Brontë’s book. Here’s what she wrote to Henry Nussey, a Sussex curate, in March 1839: “Do not therefore accuse me of wrong motives when I say that my answer to your proposal must be a decided negative … I have no personal repugnance to the idea of a union with you—but … you do not know me, I am not this serious, grave, cool-headed individual you suppose.”

Just when you thought it’d been a while since anyone asserted the death of the novel, here’s Will Self, asserting the death of the novel. “This time it’s for real,” the headline notes.

What do conductors do? Divining the art of hand-flapping: “One problem some conductors encountered is what a conducting friend of mine calls the ‘Grecian Urn’ syndrome. This is where the left hand mimics the right hand exactly, tracing the outline of an antique urn. It’s more picturesque than the ‘dead hand’ syndrome, where the left hand hangs limply, but just as useless.”

New research suggests that Freud was right all along: our dreams are fueled by sex. “I vividly recall the day in the late 1970s when I realized that dreams and their unconscious sexual meaning were part of a larger whole … I and another orderly were given the task of delousing, showering and cleaning up an old alcoholic who had been picked up off the streets for a drying-out period … All of a sudden this emaciated, brittle old man jumped up, stared straight at us revealing a full erection and then lifted a massive metal table over his head, threw it against the wall and began wailing in ever louder sing-song tones a string of sexual expletives that left me and my colleague terrified that the man was crumbling, psychically, before our eyes.”

Inflammatory bowel disease “is fast becoming resistant to every antibiotic thrown at it.” But there is a kind of miracle cure: a fecal transplant. “Some doctors have likened the recoveries of desperately ill patients to those seen with anti-HIV protease inhibitors in the mid-1990s … Yet few other interventions elicit such disgust, revulsion and ridicule … What’s behind this knee-jerk aversion? Perhaps, as one epidemiologist believes, it’s the voice of our evolutionary ancestors, warning us away from a major source of parasites and other pathogens. Perhaps, says another researcher, it’s the fading of an agrarian life that equated manure with opportunity, whose cultural influence is now drowned out by public health warnings of diarrhea-borne epidemics in towns and cities. With the last lines of antibiotic defense beginning to crumble, however, getting past the cognitive dissonance of healthy poo as powerful curative could be a matter of life or death for tens of thousands of patients.”

May 1, 2014

The Most Expensive Word in History

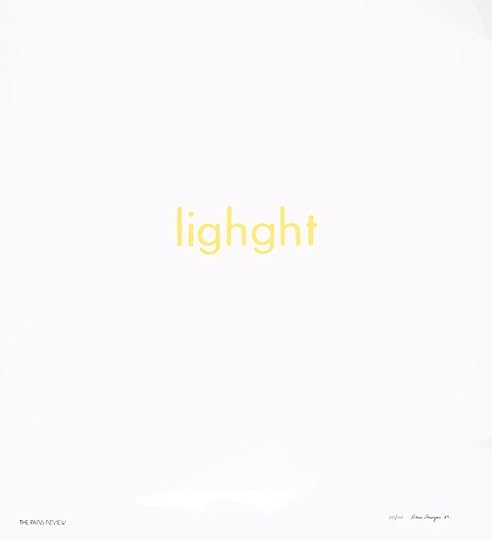

Since 1964, The Paris Review has commissioned a series of prints and posters by major contemporary artists. Contributing artists have included Andy Warhol, Robert Rauschenberg, Helen Frankenthaler, Louise Bourgeois, Ed Ruscha, and William Bailey. Each print is published in an edition of sixty to two hundred, most of them signed and numbered by the artist. All have been made especially and exclusively for The Paris Review.

Among these is Aram Saroyan’s lighght print, available in our online store. The print is a record of Saroyan’s most famous poem—one among many collected in his newly reissued Complete Minimal Poems. Soon after the poem’s first publication in 1965, “lighght” engendered a surprisingly long-lived controversy, in which The Paris Review’s own George Plimpton played no small part. As Ian Daly’s terrific piece at poetry.org explains,

Plimpton decided to include it in the second volume of The American Literary Anthology, which he was editing for the National Endowment for the Arts … Plimpton picked Saroyan’s “lighght,” so the NEA cut him a check for $750—the same as all the other authors in the anthology. The Review kept $250, and Saroyan kept the rest. All of which seems reasonable enough—that is, unless you judge the poem’s worth on a strictly cost-per-word basis—which is exactly what Congress did.

When Representative William Scherle, a Republican from Iowa, caught wind of the one-word poem, he launched a national campaign against the indefensible wastefulness of the newly established NEA, and urged the removal of its chairperson, Nancy Hanks … Mailbags of letters from fuming taxpayers clogged the agency’s boxes, most of them variations on a theme: We can’t afford to lower taxes but we can pay some beatnik weirdo $500 to write one word…and not even spell it right?!

“If my kid came home from school spelling like that,” one congressman said, according to the now-defunct arts and literature quarterly Sabine. “I would have stood him in the corner with a dunce cap.”

The NEA lived to cut another check, of course, but more than twenty-five years later, “Ronald Reagan was still making pejorative allusions to ‘lighght.’ That sparked Saroyan to write about the whole affair for Mother Jones in 1981, in a piece he called ‘The Most Expensive Word in History.’”

But our lighght print is not merely a keepsake from an ill-advised political debacle. As Daly elegantly writes—and as none of the pols could see through the fog of their vituperation—the poem is also energetic, ineffable, beautiful:

“Lighght” is something you see rather than read. Look at “lighght” as a poem and you might not get it. Look at it as a kind of photograph, and you’ll be closer. “The difference between “lighght” and another type of poem with more words is that it doesn’t have a reading process,” says Saroyan, who lives in Los Angeles and teaches writing at the University of Southern California. His Complete Minimal Poems was published in June by Ugly Duckling Presse. “Even a five-word poem has a beginning, middle, and end. A one-word poem doesn’t. You can see it all at once. It’s instant.”

The Paris Review’s lighght print is available here in an edition of 150.

LOL

Robert Henri, The Laughing Boy, 1910.

Last night, I was part of a panel on the late novelist Dame Muriel Spark, in concert with the publication of The Informed Air, a collection of her essays. In no way am I an expert, but I am a devoted fan—more and more as I get older—and I was glad to take part in the celebration of a writer who should be more widely read.

As anyone on the East Coast knows, yesterday was characterized by lashing rains and driving winds—a fact that sort of explains why I was dressed like an old salt in a fisherman’s sweater, wellies, and slicker. (Emphasis on sort of. I put on some red lipstick to make it look as though the whole thing was dashing and deliberate, but I don’t think anyone was fooled—or cared.) In spite or maybe because of the monsoon-like conditions, it was a lot of fun, and I came away with a new appreciation for an author whose work is as notable for its guarded compassion as what John Updike termed its “sweet sting.”

Everyone agreed that Spark is frequently hilarious. At least, we thought so. In the course of the conversation, my friend Emily and I discovered that in recent months both of us had attempted to read particularly amusing passages aloud to respective boyfriends, and the men in question were completely unmoved. She wondered if it was a British-American thing; I wondered if it was a male-female thing. Whatever it was, it was awkward.

By chance, another friend returned my copy of Iris Owens’s After Claude this week. It should be said that I consider After Claude’s first half to be one of the funniest things I’ve ever read. I literally laughed out loud on the subway, and I’m not prone to losing myself so thoroughly. My friend, however, told me that he “couldn’t get into it.” And in such situations, there’s no point in explaining why something is hilarious—and why someone is wrong.

Lord knows I’ve been on the other side of this. If I had a nickel for every time I’ve tried to get into The Ginger Man, I’d have a dime. The Dud Avocado left me stony-faced. We won’t even get started on Douglas Adams. But in no case did I blame these failures on the people who loved the books—I felt the fault lay with me. When we share what we find amusing, we make ourselves vulnerable. As a friend once said, watching someone guffaw at something you can’t get into “is kind of like watching them masturbate.”

Maybe I’m extra sensitive on the point. My parents used to have quite serious fights about which of the Marx Brothers was funniest—my dad felt that my mom’s preference for Groucho revealed a fundamental character flaw, and by implication, a cache of contemptible conventionality. One always felt that somewhere behind his words was the certainty that, had she been alive and in a position to, she just might have had a Bad War.

Getting back to Muriel Spark for a moment: we talked about why she was considered a “woman’s novelist,” and while that is certainly a phrase burdened by generations of condescension, in my book it’s no bad thing. When in 2008 the New York Times ArtsBeat blog asked editors of the Book Review to name the funniest novels of all time, the resulting list was overwhelmingly male. Said David Kelly, “Someone here mentioned Jane Austen, but only halfheartedly and only after I pointed out that not a single novel by a woman had been proposed. What gives?” I find this surprising mostly because the books I find funniest are all by women—and I don’t mean Jane Austen, droll as she can be. (I draw the line at rolling in the subway aisles over the antics of Lady Catherine de Bourgh, although, you know, go for it.) To my mind, it’s hard to beat Memento Mori or The Ballad of Peckham Rye. Moments of Speedboat are as funny as anything I’ve read. Barbara Comyns can be weirdly hilarious, especially in Sisters by a River. And my love for Barbara Pym is on the record. For my money, you can’t top the “Dominion of the Birds” sequence in Excellent Women. But if I had to sum up what I love in one quote:

Father Anstruther shook his head, then took a plate and wandered off to choose his tea. “Fairies,” he muttered. “Who was it who used to make such deliciously light fairies?”

“It was Mother, Father,” replied Miss Dew, oddly.

I Did Not Approve This Message

David Foster Wallace, James Joyce, and the trouble with public image.

Jesse Eisenberg and Jason Segel filming The End of the Tour, a movie about David Foster Wallace not authorized by his literary trust. Photo: loveleeliz, via Instagram

In 2010, just under two years after David Foster Wallace’s death, the journalist David Lipsky published Although Of Course You End Up Becoming Yourself: A Road Trip with David Foster Wallace, a memoir of transcripts from an interview he’d conducted with Wallace in 1996 for Rolling Stone. The book was well reviewed—it made the Times best-seller list—and late last year it was announced that it would become a film starring Jesse Eisenberg as Lipsky and Jason Segel as Wallace. The End of the Tour is already in postproduction and slated for release in late 2014, but last week, the Wallace Literary Trust issued a public statement making it “clear that they have no connection with, and neither endorse nor support” the film: “There is no circumstance under which the David Foster Wallace Literary Trust would have consented to the adaptation of this interview into a motion picture, and we do not consider it an homage.”

I was struck by similarities between this situation and the case of James Joyce and Samuel Roth, which began in 1926. In his recent book Without Copyrights: Piracy, Publishing, and the Public Domain, the scholar Robert Spoo devotes two chapters to Joyce’s desperate attempts to defend his intellectual property against Roth, an infamous American “booklegger” who reprinted the entire text of Ulysses, as well as large portions of Finnegans Wake, without permission. Roth’s actions, like those of the filmmakers of The End of the Tour, were not illegal: Joyce didn’t possess the U.S. copyright on his works, which were originally published in Europe and—after a brief window during which he could have established copyright by securing American publication—fell immediately into the U.S. public domain.

Nonetheless, Joyce retaliated. His campaign began with a letter of protest signed by more than 160 authors and intellectuals including T. S. Eliot, Virginia Woolf, H. G. Wells, W. B. Yeats, and Albert Einstein. Roth was widely excoriated in the literary press, sometimes in viciously anti-Semitic terms. Joyce was held up as a kind of martyr. When the author did finally take legal action against Roth, in March 1927, he alleged not copyright infringement but name misappropriation; his complaint was filed under Section 51 of the New York Civil Rights Law, which protects “[a]ny person whose name, portrait, or picture is used … for advertising purposes or for the purpose of trade without … written consent.” In other words, Joyce was challenging not the piracy of his work but the commercial exploitation of his name and reputation. For this indignity, he sought half a million dollars in damages.

The case never went to trial. Roth, bleeding funds and facing separate criminal charges for obscenity, settled by agreeing to a “consent injunction,” which prohibited him from making use of Joyce’s name in the future. Though Joyce saw no money from Roth and failed to establish a legal precedent for authors seeking to protect their reputations—his stated reason for bringing the suit in the first place—he was able to use the opportunity to reframe his reputation in ways that went far beyond Roth’s piracy.

“By presenting himself as a sufferer under American law, Joyce rewrote a narrative that had cast him as the law’s subverter,” Spoo writes. Ulysses, to the extent that it was known at all, was widely regarded as an immoral and indecent book, but “[i]n the wake of Joyce’s revisionary campaign, Ulysses came to seem more sinned against than sinning, less a corrupter of morals than a scene of trespass.” Spoo argues that the Roth case was a turning point in Joyce’s career that ultimately led to the authorized American publication of Ulysses with Random House in 1934—and that Roth “in the end was immolated on the altar of Joyce’s aggrieved celebrity.”

I called Spoo and asked for his opinion on the Wallace estate’s stand against The End of the Tour. (Besides being a professor of law, Spoo is a former editor of the James Joyce Quarterly and served as co-counsel for Professor Carol Shloss’s successful suit against the Joyce Estate in 2009.)

“The public statement seems to hover between an admission of helplessness and a threat of reprisal,” Spoo observed, in a lawyer’s careful tone. “I think they’re hedging. They’re saying, ‘We know we can’t stop the production, but we reserve our rights in the future.’”

Spoo emphasized that there were important differences between Joyce’s actions and the Wallace estate’s: in 1927, Joyce was alive, and thus protected under privacy and antidefamation laws that don’t extend to Wallace as a deceased person. “In the United States there are severe limitations on preventing anyone from talking about the dead,” he told me. “You can’t libel or slander the dead. They don’t really have any privacy rights to speak of.”

But because they hold the copyrights to Wallace’s works, the Wallace estate’s case may be stronger than Joyce’s was. Even though the estate doesn’t own the rights to Lipsky’s memoir, Spoo speculates that “there could be a copyright issue if the movie were to make use of any of [Wallace’s] published writings without permission.” Then, too, the transcripts of the interview Wallace gave to Lipsky in 1996 could be copyrighted and claimed by the Wallace estate, since taped interviews, according to Spoo, present a gray area, legally speaking.

A more likely legal recourse for the estate would involve not Wallace’s intellectual property but his name, reputation, and what is called the right of publicity or “personality rights.” Could the Wallace Literary Trust sue the filmmakers of The End of the Tour on the basis of name misappropriation, as Joyce had done in 1927? Possibly, though the legal strategy wouldn’t be the same. The 1903 privacy rights statute under which Joyce’s complaint was filed is still on the books, but only in New York State, and only for the living; there are no federal laws pertaining to publicity rights. But California—the most obvious state in which to bring suit, since it was Wallace’s place of residence at the time of his death, and the case involves a Hollywood production company—has very stringent personality rights laws. (In 1985, the legislature passed the Celebrity Rights Act, which grants personality rights for seventy years after death.) “The Wallace estate are probably thinking about this,” said Spoo. “They probably are wondering to what extent will the movie be using Wallace’s name, and will it be in such a way that they could possibly have a cause of action.”

A further complication: in the eyes of the law, is the version of Wallace played by Jason Segel a real person or a character? If the estate makes a fuss, the filmmakers could easily argue the latter. “If somebody’s name is used in a book”—even a biography or a work of nonfiction—“it is typically very difficult,” according to Spoo, “to sue for a violation of publicity rights.”

How much damage could the Wallace estate do to The End of the Tour? Legally, their options may be limited, but, as the tale of Joyce and Roth shows, there are always options for famous authors to pursue in the court of public opinion. If they continue to be vocal about their displeasure, they could have a substantial effect on the film’s fortunes among its core audience of Wallace diehards. While they might not succeed in making David Lipsky or the film’s director James Ponsoldt into cultural pariahs—the modern-day equivalents of Samuel Roth—they could definitely make their lives more difficult.

* * *

Some literary estates are more obstructionist than others. Joyce’s estate is, notoriously, one of the worst: on principle, his grandson Stephen refuses many requests to quote from Joyce’s work. On the face of it, there’s nothing wrong with the Wallace Trust’s attempt to distance itself from a film it has nothing to do with, if that’s as far as it goes—but some Wallace scholars are already worried that this statement may augur ill for the future.

“I’ve been troubled by the idea that one has to reach out to the estate of a deceased person to get permission for things,” Spoo said. He allowed that some uses of an author’s name and work might be legally sound but ethically questionable, and it’s appropriate, in such cases, to reach out to an estate to ask their blessing. “But I don’t know where that line is, so I refuse to draw it,” he went on. “Every time I try to draw it, I find that I’m silencing something that could be valuable to talk about. I just don’t think there should be a limit on how we interpret an author.”

Wallace is heir to a literary tradition that has historically sought to limit interpretation in just this way. Modernism and postmodernism are aesthetic movements that evolved alongside the strengthening of intellectual property laws and the growth of a hyper-protectionist rights-based culture, particularly in America. “Modernist authors thought of their work as ownable and resented assaults on it,” Spoo writes. “The idea of literary property was talismanic, emblematic of respect for artistic labor, an acknowledgment of the dignity of the attic.” Like many of the ideas modernist writers espoused, this one was tinged with anxiety: “The fear of failed copyrights lay behind many developments of modernism.”

I asked Spoo whether this fearful, protective attitude toward intellectual property persisted, in his opinion, into the postmodern period. The question seemed to catch him off guard, but he did his best to indulge me: “If modernism is a period of concern over copyright—or of trying to find reasonable substitutes for copyright—is postmodernism a postcopyright period?” he wondered aloud. “The writing changes, the whole sense of one’s relationship to one’s own writing changes. When you look at the voice of a Pynchon or a Gaddis or a Burroughs, is it a voice that is claiming singular ownership of these words? I’m not sure it is. There seems to be a postproprietary attitude in the writing itself. Whether that reflects a postcopyright attitude towards one’s work, though, I don’t know.”

Some readers of Wallace have attributed such a postproprietary ethos to him. Writing in The Awl, Maria Bustillos sensibly warns us not to “even speculate on the sad and unfathomable question of what Wallace would or would not have consented to”—but criticizes the estate for attempting to police his reputation. “Any honest effort to discuss, to understand, and to build upon the conversation Wallace’s work began should be honored by readers in the spirit of intellectual curiosity and open-heartedness he himself embodied in his short life,” Bustillos writes.

Yet we know from D. T. Max’s biography, Every Love Story Is a Ghost Story, that Wallace was intensely concerned with his public image. In this he follows in the footsteps of his heroes Thomas Pynchon, William Gaddis, and Don DeLillo, all of whom have been, in their way, just as controlling of their reputations as Joyce was, even if they exert this control through anonymity and refusal rather than through protectionist aggression. Is there a connection between the kind of encyclopedic, all-encompassing fictions that both Joyce and Wallace wrote—what Tom Le Clair has called “the systems novel” and James Wood “hysterical realism”—and the slightly hysterical attempts of writers and literary estates to shape the public’s impression of their legacy? I think of Oscar Crease, the playwright at the center of Gaddis’s A Frolic of One’s Own, obsessively pursuing a futile lawsuit against filmmakers he thinks have stolen his idea: a grotesque version of the artist as rights-holder, disfigured by his sense of injustice.

Whether the Wallace estate’s attempt to dictate the terms of his public image is in the author’s spirit or not, one thing is certain: it’s doomed to failure. Writers’ reputations, particularly after their deaths, are not carefully crafted works of self-expression but palimpsests by diverse hands. “With somebody as big as Wallace or Joyce, it’s ultimately impossible for one entity to shape their authorial image,” Spoo told me. “There are too many people interested in them to control it.”

Evan Kindley is an editor at large at the Los Angeles Review of Books and a contributing editor at The Pitchfork Review. He teaches at Claremont McKenna College.

A Field Guide to the Ass-End of Hell

On reading Peter Matthiessen in the Everglades.

I first encountered Peter Matthiessen in a hurricane, with the roof-flown certainty that we’d never meet again. Just passing through, the memory blurs at 135 mph. I was in the Bahamas reading Killing Mister Watson, sweating out a Category 4, trying to concern myself with an Everglades outlaw who produced excellent cane syrup and, in the wake of his murder, a bunch of conflicting yarn-burners. I only made it through the beginning, apparently no further than E. J. Watson himself, ventilated by thirty-three neighborly slugs upon stepping off his boat and into his own lore. This just after the hurricane of 1910 had wasted Chokoloskee. Announced by a comet, the storm upchucked the marl, catapulted Watson’s infant son through the mangroves, and, as Matthiessen had it, “blew the color right out of the world.”

My hurricane merely blew the color out of the TV. With an earful of low-pressure williwaw, I had problems getting all those Watson thoughts inside my head, preparing to duck shard as the windows bowed, wondering if the author’s next word would be my last. Kind of a morbid, if not meteorologic, approach to one’s literature, imagining the final line that accompanies you and your velocity into the whateverafter, joining LeQuinn Bass (last words: “Well, shit”), the Owl Man of Deep Wood (“Finish it”), Belle Starr (a screech—she was shot in the back, off her horse), and whomever else Bloody Watson managed to ether before it was all said and blown away. The last thing you’d want to read should be the first. Maybe something poignant about nature’s collaborative disregard for epitaph and perpetuity: bloodless fungi and blind algae that worked with the wind and rain to obliterate man’s scratchings. Or more to the point: Folks have had enough of your ratfuck family. There was an excess of fine choices and the wind sounded like it wanted them all, so I gave up. I watched Victor Victoria until the power went out, right when James Garner was spying on Julie Andrews in the tub. Then darkness. Then back under a feedstore in Chokoloskee, hiding in the stink-rot of the postman’s drowned chickens.

Located at Chatham Bend, Smallwood’s feedstore now serves as a Watsonian institute and occasional destination for ghost busters. Though Watson has yet to be implicated in the strange orange cloud seen hovering over the parking lot by a team of paranormal investigators from Missouri, the site holds the warrant for his arrest in Oklahoma in 1889. There’s also a chart mapping out the murders Watson may or may not have committed, and a box of corrupted shells that Watson may or may not have loaded into his shotgun during his last moments. The handwritten inscription beneath the photo of the Watson house says, “Rangers burned it.” With their livelihoods endangered by a bunch of no-account cypress huggers, locals may have hated the federal government and its National Park claims more than they feared EJW.

Photo: Dave Tompkins

Last May, I caught a ride with a pair of archaeologists to Ten Thousand Islands, in the southwest Everglades, to see how Watson it really was down there. My copy of Killing Mister Watson had been rendered inoperable by Hurricane Ike, but I had since vanished into Matthiessen’s Shadow Country and its nine hundred pages of beautifully rendered Audubonic bird riffs, free of my personal weather hysterics, save for some in-flight turbulence during the part where Watson’s second born decapitates his old man’s buried corpse, not without exertion. At times, it reads like a Petersen’s Guide to Dirty Deeds in the Everglades, with special attention to fouling the air. Such evocations of nature and blasphemy to the nose make me wish the ghost of this ex-CIA naturalist would transcribe the bog-burp scene from The Dark Crystal. Or the fish-gut documentary Leviathan , which offers a drowning man’s POV of gulls in the sky. Stenches carry.We took the Tamiami Trail to Everglades City, as did Lucius Watson, when driving down to sort out his father’s legend among suspects, back when the road was just a limestone sketch of puddles and potholes. This included twenty or so farmers and fisherman who’d been deputized by the sheriff to arrest the man they’d already shot to pieces. Matthiessen checked off a similar posse list (or cousin thereof) for his own research. Lucius would end up tossing his unfinished Watson manuscript into the fire, a scene that appears in the middle of a rewritten manuscript that earned Matthiessen the National Book Award. Just another tangle with history and myth in the Everglades, swapping muckspit and twang vector. But be careful what you dredge for. In her book Swamplife, anthropologist Laura Ogden describes the Everglades as a rhizome, “entanglements of people, memory and nature on the move,” for the shifty and shiftless, as well as those who engaged in their own conquest of the useless, trying to scare up harvest from soil entombed with ancient dead marine matter, ossified Calusa, and the slain black workers who originally pickaxed the shell and chopped cane on Watson’s property. Offing employees kept costs down.

Then working in cultural resources for the National Parks, my friends were going to Chokoloskee to investigate a shell mound in an artifacts site possibly linked to the Calusa or Miccosukee. Watson provided atmosphere. Along the way, talk migrated from the bass line in Ice T’s “Colors” to Chief Billy’s missing finger—Chief Billy, the ex-Vietnam helicopter pilot who lost his middle flipper to an alligator and told dirty jokes about it while flying one of the archaeologists to see prehistoric canoes. The other archaeologist had recently boated Miss Florida through the Everglades and learned her father was a swamp hydrologist and that Miss Florida was actually Miss Queen of the Coast. Conversation down there often invents new ways to arrive at drainage and gators.

Photo: Christy Gast

The shell-mound hopping commenced in a shallow-water flats boat, with a face full of wind, free of mosquito clouds and bales of weed dropping from the sky. Not a galoot in clear blue sight, just landscape on the creep, as if the mangrove were going to up and take the islands with them. Early Florida naturalist William Bartram would’ve called this “enlivening the delusion.” Through the engine roar and jacket flap, one of the archaeologists mentioned a man in Everglades City going on YouTube and saying his wife had “gone missing.” The ranger then yanked the wheel into a starboard dip, giving the boat a sudden DEA lean before joyriding into wave donuts. But it was the birds that were clearly having the most fun. Squadrons of swallow-tailed kites skimmed the water, racing parallel with us, then breaking sharply toward another estuary, another Watson haunt, no beak or bird feet, just wing and tail in sharp resonance, cutting headless shadows into sky paper. Then hurricane-defiant ibis, snake-necked anhingas, and pelican bug shovels. (Half expected to see the Chuck-will’s-widow metaphor that preceded the first bullet into Watson.) Then egrets, their legend migrating up to Florida on a Bahamian ghost tale: man marries witch and witch transforms into egret, chanting Kyee bottom-bottom. But hunters just wanted these birds for their plumes. Matthiessen’s depiction of blasted egret rookeries: the silence that returns after all the shooting, but in the dream of yet another Watson triggerman, “ghosty trees on dead white guano ground,” heaps of skinned carcasses left behind. The vultures can’t keep up, “so stuffed and stupid they can’t hardly fly.”

We pass Chevelier Bay, named after the French rare-egg collector who took a more humane approach to his pluming and “scraped acquaintance with every field of knowledge … except how to get on with other human beings.” (Watson shoots the felt hat off Chevelier’s head, thirty pages in.) After a brief archaeo-CSI analysis of a rectangular plot of mud (Ranger: “It’s so nerdy to dig in the dirt and blau! just know things!”), my friend suggests we head over to Watson’s, as if Watson still existed. As if he didn’t. En route, the engine is killed so we can just float and admire a cow-faced ray and then a bull shark. Someone makes a crack about seeing the Tucker kid in the shallows, killed by Watson’s son and left for the gators, happy to tamper with the evidence. More kites blow past, this time in the opposite direction, away from the forty-acre shell mound once referred to as the “ass-end of hell.” Watson’s Place. A sky-blue Port-a-Jon sits on the dock, to the right of a historical marker. Still no mosquitoes. Where are all the mosquitoes?

The cistern. Photo: Christy Gast

One of Watson’s original gumbo limbo trees (Bursera simaruba) has managed to endure over a century of Floridian storm bluster. Nothing remains of the house, save for a few foundational pilings, two cisterns, and the cast-iron vat for boiling Island Pride syrup. Empty houses often retreat back into the woods in Shadow Country. When a teenage Watson dares to glance back at the Owl Man’s charred mansion in Edgefield, Georgia, the house (called Deep Wood) “withdrew like a wounded creature behind the climbing shrouds of vine and creeper.”

The Owl Man was family, one of the few positive, not to mention literate, influences in Watson’s life. A confederate war hero with “commendable wounds,” Watson’s cousin Selden Tilden had been tarred, feathered, scalped, and deposited in a hog wallow for abolitionist views that mocked the Regulators. Then things go Ambrose Bierce. Watson thinks he sees the banished Owl Man on the roof at Deep Wood, crouched between dormer and bee’s nest. He considers consulting his own pigs, transplanting the apparition into bacon consciousness: “What could hallucination mean to young pigs starved for slop?” Good question. (To which Kenneth Patchen might’ve retorted, “In a pig’s sun porch!”)

Distracted by the idea of pigs tripping on Owl Man stealing Watson’s dead rabbit, I almost lose my place—now standing at Bloody Watson’s cistern, gauging the snake-nip index. Composed of tabby and crushed shells, this is where marooned diamondbacks whispered off to after the hurricane, eyeing Watson as he entered his house for the last time, his psychopathic rapist foreman Leslie Cox brooding in the dark, drunk on hooch, reeking from murdering the rest of the household while Miccosukee tribesmen stood quietly in the mangroves, waiting to haul this evil shithead away. The author does humanity a solid by leaving Cox’s hard-earned demise to the imagination. Race hatred is twisted into a sneer, “the way a cat twists out a crap, leaving that nasty little point at the back end.”

Whatever happened here, one thing is certain: the mosquitoes want me off the island. I’m covered—all up in my face, eyes, nose, ears. The archaeologist chuckles, cracking her mouth just enough to mutter, “This is just light bug.” Brack stagnant, the cisterns provide optimal breeding pools. Some say this is Watson’s way of continuing to extract blood from Chatham Bay, another drainage scheme from one of Florida’s most notorious invasive species: a fire-headed drunk in a linen suit who could shoot your mustache off. Now, heavy bug.

Dave Tompkins is writing a book on the natural history of subwoofer bass ecosystems in Miami. His first book,

How to Wreck a Nice Beach

, was published in 2010.

Special thanks to M. Memory (archaeologist) and C. Gast (constructed a full-scale fabric replica of the Nike Hercules missile, based in the Everglades). The trip wouldn’t have been possible without them.

Train Robberies for Everyone, and Other News

Marius Amdam, The Great Train Robbery

Junot Díaz on getting an MFA: “I didn’t have a great workshop experience. Not at all. In fact by the start of my second year I was like: get me the fuck out of here. So what was the problem? Oh, just the standard problem of MFA programs. That shit was too white.”

Al Feldstein, the editor who turned Mad Magazine into an institution in the late fifties, has died, at eighty-eight. “In his second issue, Mr. Feldstein seized on a character who had appeared only marginally in the magazine—a freckled, gaptoothed, big-eared, glazed-looking young man—and put his image on the cover, identifying him as a write-in candidate for president campaigning under the slogan ‘What—me worry?’”

When print books are scanned and converted into e-books, a process called optical character recognition is supposed to ensure that all of the letters are “read” correctly. But things sometimes go awry, and your e-book includes sentences like this: “‘Bertie, dear Bertie, will you not say good night to me,’ pleaded the sweet, voice of Minnie Hamilton, as she wound her anus affectionately around her brother’s neck.”

DreamWorks’ Jeffrey Katzenberg has a dim view of the future of the cinema: “A movie will come out and you will have seventeen days, that’s exactly three weekends, which is 95% of the revenue for 98% of movies. On the eighteenth day, these movies will be available everywhere ubiquitously and you will pay for the size [of the screen you watch it on]. A movie screen will be $15. A 75” TV will be $4.00. A smartphone will be $1.99… ”

In praise of train robberies: “Dismemberment and armed robbery have been lost in today’s commuting experience … A few train robberies would do wonders for commuter attitude. Instead of insisting the city clean up all the snow as opposed to just most of it; instead of complaining that the Citi Bike seats are too long or short, too hard or squishy; instead of issuing eye rolls when a passenger shoves in ahead of closing doors, disrupting their Candy Crush level—a train heist would remind folks that any arrival, even a tardy one, is a blessing.”

What’s wrong with contemporary philosophy? “The exclusion of the agrarian and nomadic, in favor of the urban and sedentary. The problem is not just ‘the West’, or Europe, or masculine domination, or white supremacy, or even the intersection of all of these. The problem is the city.”

April 30, 2014

David Lynch, Hiding in Plain Sight

The filmmaker comes to BAM.

Lynch in 2007. Photo: Thiaggo Piccoli, via Wikimedia Commons

What, in retrospect, did we hope to hear from David Lynch last night? In “a rare public appearance,” the filmmaker appeared in conversation with Paul Holdengräber at BAM, to a sold-out crowd. The people were there. Lynch was there. And so … now what?

It wasn’t as if we expected to walk out with David Lynch decoder rings, finally capable, having listened to him, of educing his films’ meaning. Much of their joy derives from their refusal to cohere. Nor could we reasonably hope to reconcile the work with the man—the gap between the Missoula-born Eagle Scout and the psychosexual Grand Guignol of, say, Blue Velvet has always been pretty difficult to bridge. That’s all part of the Lynch magic, and you can hardly expect a guy to declaim upon the essence of his magic…

So why were we there, then? Did we simply want to see him bodily, to confirm the corporeal existence of a man whose work sometimes seems—extraterrestrial? Sure. But we also presumed we would learn something, anything, about him. Something new, something that qualified as insight: something that might make the whole Lynchian gestalt that much less opaque.

Such was not the case.

As David Foster Wallace wrote in 1995, “Lynch’s movies are about images and stories in his head that he wants to see made external and complexly real.” Lynch has expanded the grammar of film as much as any director of his era; he has as singular and penetrating a vision of American life as any living artist—and he had almost nothing to say about his work, especially not about his movies. He wasn’t going to talk shop. He wasn’t, with the exception of a bit about Eraserhead’s Lady in the Radiator, going to talk about the stories in his head. Sometimes it seemed he wasn’t going to talk, period.

“One time I heard it,” he said of Bobby Vinton’s cover of “Blue Velvet”—“and images started coming from this song…”

Aha! What images?

David Lynch didn’t say what images.

Holdengräber tried to draw him out. It was just the two of them onstage, under the hot lights—two chairs, a small table, an area rug, and an awed hush. In his gentle Continental croon, Holdengräber read aloud a few florid quotations and asked Lynch to react.

Lynch didn’t care much for reaction. The quotations were beautiful, he acknowledged. Many things last night would be described as beautiful.

On a big screen behind the men, an iconic image from Blue Velvet appeared: a detached, decaying ear half-buried in a suburban lawn. And Holdengräber ventured, coyly—he might ask, why this ear …

“You’d have to see the film,” Lynch said.

This got a big laugh. Silly Holdengräber, the audience seemed to say, with his insistence on interpretation, his outmoded desire to know more! Still, maybe he could goad Lynch into saying something about his thoughts, his inspirations—the intro to Eraserhead crept onto the big screen, and Holdengräber recited another beautiful quotation about the dreamlike nature of the cinema…

“It’s done,” Lynch said conclusively of Eraserhead. “Then it goes out into the world, and it is what it is.”

Now the people broke into boisterous applause. Absolutely! It is what it is! What a genius! Who could deign to take issue with such self-evident, tautological truth?

Holdengräber was a bright and quick-witted interlocutor—but his measured, psychoanalytical approach was humorously at odds with Lynch’s gee-willikers shtick. He displayed a series of paintings on the big screen—Edward Hopper, Francis Bacon—and treated them like Rorschach blots. What did Lynch see in them? How did they make him feel? Lynch didn’t even have to answer, really; he could proffer an all-American gee-whiz shrug and trot out those sincere adjectives. (“Beautiful … fantastic …”) He never had to put his art on the line.

And thus we heard that David Lynch loves Jimi Hendrix (“He may be the best guitar player”); we heard that David Lynch loves Kanye West (“I love ‘Blood on the Leaves’ … so minimal, so powerful, but at the same time so beautiful”); we heard that David Lynch loves the paintings of Francis Bacon and Edward Hopper; we heard that David Lynch loves sugar (“granular happiness”); we heard that David Lynch loves factories, or rather, he loves what factories are made of: “I love smoke. I love fire. I love metal. I love glass. I love plaster. I love bricks.”

David Lynch loves, and he believes. He would have you think that this is all he does—he’s just folks! He believes in coffee. He believes in the harmonics of ideas. He believes, of course, in transcendental meditation, in beams of white light from the Buddha’s eyes, in a reservoir of unlimited human potential.

An image flashed onto the big screen: the sun-drenched exterior of Bob’s Big Boy, in Burbank. Something thawed in Lynch. He began to talk. He went to Bob’s Big Boy every day for seven years, he said; he’d order a chocolate milkshake and lots of coffee. He’d show up at 2:30 in the afternoon, hoping the shakes wouldn’t be runny since the machine had had time to cool down after the lunch rush. Plus, a diner, as he astutely noted, is a terrific place to lose yourself. You could free-fall into one dark mental crevasse after another, could do some serious psycho-spelunking—but with the people, the food, and the warm incandescent light, you’d always know how to recover yourself.

At last! Lynch was telling a story—was opening up—we could picture him arriving daily as the crowd thinned; installing himself, maybe, in the same booth every time, in wordless enactment of some Lynchian ritual; wondering, as some late-model soda jerk got to work on his order, Will today be a perfect milkshake day? In three years, he only got three perfect shakes, he said. In fact, so lacking was quality control that he one day took it upon himself to go out back behind the restaurant, searching for the box of milkshake mix—what was in that stuff, anyway?—dumpster-diving behind his favorite haunt, searching, bent on solving the mystery…

Why did he want to know?

What sorts of images occurred to him in the diner?

He might have gone on, but Holdengräber had no further questions on the subject. And with that, any hopes of “real talk”—of getting to kinda know the guy—were dashed.

* * *

It’s perfectly defensible for an artist to claim that his work is self-contained, or that he’s no more attuned to its mystery than his audience is. No fan of Lynch’s would disagree with his assertion that “Some people like to have a meaning, and some people don’t care, because it allows you to dream.” But there are gradations to this position. An artist can discuss his vision, his ideas, without filing a final verdict on what his work means. He can offer a window to his work without declaring it the window.

Lynch took a hard line. No way in hell would an aspirant filmmaker leave that auditorium with a scrap of technique from the master’s table; no way would a casual fan find a new way of seeing. Again, there’s nothing wrong with such limits. But one wonders why a man who so disdains explanation would consent to appear in conversation—before thousands of spectators. There were eager apostles in every one of the 2,090 plush seats in the Brooklyn Academy of Music’s Howard Gilman Opera House (“beautiful theater…”) just waiting to hear … something.

But Lynch knew his audience—he knew that most any something would suffice. As Flavorwire notes in its fawning review of the night, Lynch boasts “a genial folksiness that would make the average grasping politician jealous. When Lynch says ‘guys,’ ‘girls,’ and ‘folks,’ he means it, and doesn’t sound coached to death.” More than an artist, Lynch was a politician last night, and this was a campaign stop—he was burnishing his reputation as a savant, as David Lynch, the willfully eccentric auteur-entrepreneur. The crowd at BAM was largely of that new, younger generation who have come to Twin Peaks by way of Netflix, who have not been aware of Lynch long enough to have seen one of his movies in theatrical release. He knew we were already believers; where once he was Hollywood’s enfant terrible, he has assumed, somewhat uneasily, the role of éminence grise. He didn’t have to talk seriously about his art. He just had to be kind of faintly … you know … Lynchian. He had to build his brand.

Lynch hasn’t made a movie since Inland Empire, which appeared in 2006; rumor has it he’s working on one now, but in the intervening years, he’s found the time to record two albums of electronic music, to open a nightclub in Paris, to market his own line of organic coffee—and you can pick up a pair of Twin Peaks Nike Dunks, too. For a while he recorded himself reading the weather for Los Angeles every day. Granted, he’s always been one to keep many irons in many fires, and his eclecticism is hardly something to be shunned. But those extracurricular interests were always pursued alongside, rather than instead of, his work as a feature-film director; this is the longest he’s ever gone without a major release. And yet he’s already captured the youth vote. Brooklyn Vegan called the night a “freewheeling gabfest”—as if it wasn’t filled with ponderous silences.

Is it too cynical to declare that all this is more calculated than it seems—and less artful? Lynch may be able to utter a believable “shucks!”, but he’s much too canny in his self-presentation to be a true eccentric. In other words: he may well be a weirdo, but he knows exactly what he’s doing. The Lynch brand sometimes seems to extend straight to his shock of white hair—coifed and/or pompadoured specifically so that we of the media might call it a shock, because that’s what our eccentrics must have: shocks of white hair.

Why is such a brilliant filmmaker so insistently branding himself? It undermines the singular strength of his movies—the movies he has no interest in talking about, but plenty of interest in kind of talking about…

“It’s treacherous talking with you,” Holdengräber said at one point. Lynch responded with surprising candor. “The words, they’re not really necessary,” he told the crowd—all two thousand of us—who had paid at least twenty-five dollars to see him speak.

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers