The Paris Review's Blog, page 708

May 6, 2014

Entirely New Problems

The Archers, 1935-37

Snowy Landscape, 1930

Tavern, 1909

View of Basel and the Rhine, 1927-28

Violet House in Front of a Snowy Mountain, 1938

Self-Portrait as a Sick Person, 1918-19

Sitting Woman, 1907

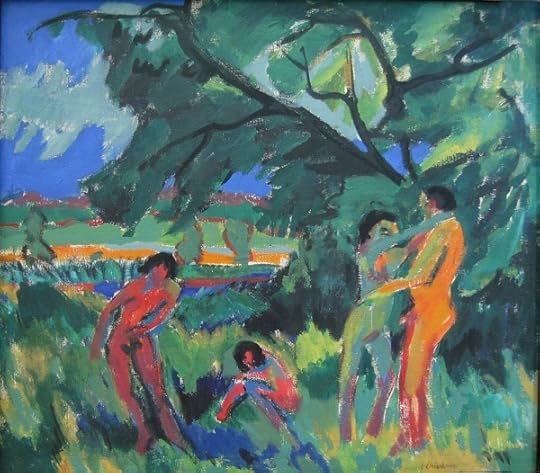

Naked Playing People, 1910-11

Landscape in Graubünden with Sun Rays, year unknown

Self-Portrait as a Soldier, 1915

Vier Holzplastiken, 1912

Apropos of Sadie’s piece about “degenerate art”: today marks the birthday of Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, one of many German expressionist painters whose work the Nazis filed under that dread “degenerate” rubric. Kirchner, who was born in Bavaria, suffered a breakdown when he was serving in World War I; he was plagued with health problems for the rest of his life, and spent much of his time in Davos. In 1937, the Germans destroyed or sold more than six hundred of Kirchner’s works; from Switzerland, he wrote,

Here we have been hearing terrible rumors about torture of the Jews, but it’s all surely untrue. I’m a little tired and sad about the situation up there. There is a war in the air. In the museums, the hard-won cultural achievements of the last twenty years are being destroyed, and yet the reason why we founded the Brücke was to encourage truly German art, made in Germany. And now it is supposed to be un-German. Dear God. It does upset me.

In 1938, fearing that Germany would annex Switzerland, Kirchner shot himself. The Kirchner Museum, in Davos, offers a fifteen-page biography of the artist—a remarkable, if sorrowful, read, full of suffering and exile. I was struck foremost by this prefatory note—intended to introduce his 1922 exhibition in Frankfurt—which Kirchner wrote himself under the pseudonym Louis de Marsalle. It finds the painter somewhat desperately planting the idea that he’s reinvented himself, that his illness, and his new life outside Germany, have only bolstered his work. He seems bent on convincing himself of his success as much as anyone else:

The bleak and yet so intimate nature of the mountains has had an enormous impact on the painter. It has deepened his love for his subjects and at the same time purged his vision of everything that is secondary. Nothing inessential appears in the paintings, but how delicately every detail is worked out! The creative thought emerges strongly and nakedly from the finished work. Kirchner is now so taken up with entirely new problems that one cannot apply the old criteria to him if one is to do justice to his work. Those who wish to classify him on the strength of his German paintings will be both disappointed and surprised. Far from destroying him, his serious illness has matured him. Besides his work on visible life, creativity stemming solely from the imagination has opened up its vast potential to him—for this the brief span of his life will probably be far from sufficient.

Degenerate Art

Lasar Segall, Eternal Wanderers, 1919, oil on canvas; on display at the Neue Galerie.

Cornelius Gurlitt, identified in obituaries as a “Nazi-era art hoarder,” died this morning in Munich of heart trouble. Gurlitt’s cache of more than 1,400 important modern works, inherited from his art-dealer father—including pieces by Picasso, Matisse, Manet, and Renoir—was discovered in 2012. It was not made public until November 2013. Although classified as “second-degree mixed-race Jewish,” Hildebrand Gurlitt was one of three dealers given official sanction by Hitler to peddle “degenerate art” in other countries, with the profits going to Germany. And although Gurlitt was required to return a number of works to their former owners, the majority of the collection is thought to have been acquired “legally.”

Says Bloomberg,

Isolated from the outside world, Gurlitt stopped watching television in 1963, booked hotel rooms months in advance by post when he had to travel, and never used the Internet, according to Spiegel magazine. His collection was discovered in a raid after authorities became suspicious when he was found carrying 9,000 euros during a random search at the Swiss border in 2010. He was returning from a visit to Bern to sell some artwork there.

It is unclear what will happen to the collection, although art historians will apparently continue to investigate the works’ provenance and post images of them.

By chance, New York’s Neue Galerie is currently hosting a wildly popular show titled “Degenerate Art: The Attack on Modern Art in Nazi Germany, 1937,” which attempts to replicate, in part, the famous traveling exhibition that the Nazis sent across Germany and Austria, as both cautionary lesson and moneymaking venture. The images assembled by the Neue—by Kirschner, Grosz, Klee, Kokoschka, and many more—represent a triumph of curation and international cooperation. But Gurlitt’s cache might have changed and broadened the scope of the show considerably—a thought that’s enough to give you chills.

When I saw the show at the Neue, it was packed, with lines out the door. But it was collegial; we were all so eager to have a brush with darkness, to be part of its routing, and then to have a Klimtorte in the magnificent restaurant, which is modeled on a Viennese coffee house. A woman who entered ahead of me said that she and her sister had planned their vacation from San Francisco specifically to see the show.

Gurlitt was apparently confused by the uproar caused by his collection. He said in 2013, “What do these people want from me? I’m just a very quiet person. All I wanted to do was live with my pictures.”

Maude

Franz Marc, Kater auf gelbem Kissen, 1912

I was in New York for a book talk, staying at a friend’s house in an industrial area of Brooklyn, when I awoke to a sound somewhere between a teakettle’s whistle and the creak of an ancient floorboard: my friend’s cat, Maude, meowing piteously at the edge of the bed. She was tiny, the color of ivory, with half crescent moons for claws and bright green, bloodshot eyes.

I’d been warned that Maude meowed in the mornings when she wanted the faucet turned on—she drank from the tub—so I walked to the bathroom and twisted the spout until cold water trickled down. Maude leapt into the tub and began lapping away, her tongue bright as chewing gum. I went about my slow morning routine: coffee, Twitter, fussing with hair, scrutiny of encroaching crow’s-feet, etc.

It was noon by the time I was ready to leave, and I returned to the bedroom for my laptop. There, in the middle of the white room, on the white bedspread, was the white cat, covered in blood. It seeped out from her in clouds, watery and pale red like a nightmare sky. But when I bent over and touched her she was still breathing, alert, looking at me with those science-fiction eyes.

There is blood in the abstract and blood in the now, and real blood always makes me feel like I’ve just jumped out a window. I’m Wile E. Coyote perched in midair, finally looking down. I called the cat sitter, who lived just a few doors away; she was barely out of her teens, but had a comfort around bodily fluids I will never possess. We climbed the narrow stairs to the bedroom together, and then she lifted Maude up and examined her skinny, sticky legs with those hard moons of nail. There was no wound, just a bladder that had emptied itself of the wrong liquid.

I had known the cat was unwell, but not the extent of the truth: Maude had kidney cancer. The cat sitter carried a supply of pain medication, and she withdrew a syringe of it from her bag. Maude was pliable in her arms, unresisting, and seemed to calm down even further after the injection, her features melting into the young woman’s small arms.

I left Maude with the cat sitter for the rest of the day. Hours later, the image of the stained comforter clung to me while I read to a roomful of young Brooklynites. My stories were about death, but death of the least emotional kind, death that occurred centuries ago among kings and queens, when velvet-wrapped relics were handed out like party favors among the elite and surgeons stored skeletons like chipmunks hoarding nuts for the winter. There are real people in real graves in my book, but they died deaths that no one alive today would mourn. If they did, it would be with the sweetness of a sorrow once removed, the way you feel after a good cry at the movies.

That night, I found Maude curled up on my hosts’ daughter’s flowered bedspread. There was no blood left, thanks to the cat sitter’s cleaning, just the cat, breathing slowly, the moon illuminating her pale fur through the window. I knew she was dying. There was something in her eyes, a seeing without seeing. I sat down on the bed with her, though I knew there was nothing more I could do, her veins already coursing with powerful pain medication, her owner already on his long drive home from Vermont.

* * *

Several years back, I had attended an event where a local philosopher attempted a “séance” of dead writers. There were no lace-draped conjurers, no Ouija board, no crystal balls, just the bald philosopher jumping on the cushions of a booth to read the introduction of his new book. When I expressed my disappointment at the lack of theatrics, a friend’s date shuddered. “Death isn’t funny,” she said. “It’s not cool. Once you’ve had someone close to you die, you know that.”

That had made me think of Ellen, whom I met in fourth grade when I was impressed by her ability to draw cartoon bunny people. She penciled them in the corners of her notes to me, chubby buck-toothed creatures formed from interlocking circles. From her yearbook photos—long curly hair, perfect skin, widely spaced brown eyes—I can see she would have been beautiful now.

Ellen belonged to a family of Ukrainian Jews who lived in a depressingly functional apartment complex near the mall. Like many girls on the brink of adolescence, we were obsessed with clothes. My most enduring memory of her is when she chastised me, over the phone, for wearing the same peach turtleneck to school yet again.

This obsession with appearances led to us drifting apart. She went to a different middle school and hung out with preppy kids. I discovered grunge and lived permanently in combat boots. We didn’t speak. The next time I saw her, she was in my living room pressing a bloodied tissue to her nose, her bald head large as a melon.

The type of cancer she had escapes me now. My mother, who was close to her family, said they used to vacation near Chernobyl, and I pictured sickness dusting the rusted machinery there, welling up in the water. Mom visited her in the hospital, but I never went. I had a horror of hospitals: the white instruments, the stainless steel, hope wilting in the corners next to the potted plants. I was thirteen, too interested in who I would become to think about other people ending. And then one morning I awoke early to my mother’s soft sobbing in the kitchen—Ellen had died.

I don’t remember much of the procession to the cemetery, just the dark bulk of her family moving across the grass, the ridges of gravestones like the crests of white waves. Ellen’s mother, her short curly hair dyed red to hide the grey, had a face like a wrung-out sponge. My mother told her it was good she’d had two children, so she’d have something besides Ellen to live for.

* * *

Did I feel guilty for not ever visiting Ellen in her final months? For not ever saying hello, other than the one time she was in my house? Was that why I wanted to sit with Maude that night? Probably. I stroked Maude’s cream-colored fur, feeling her belly rise and fall and listening to the night sounds of Brooklyn around me. Silverware clattered, babies cried, a few seconds of music swelled from a passing car. It reminded me of the hum around Ellen’s apartment: dozens of people living together yet alone.

It was around that time I realized Maude’s belly was no longer moving. I bent down to listen, but there was nothing. I jerked my hand away. Don’t touch her, she’s dead, I thought, as if this kind of touch pollutes. But another part of me knew that death isn’t contagious, that it moves more slowly than we think. I stayed with Maude, my hands lingering over her little body, even as I felt the sadness rise inside my chest. After a few minutes, I walked over to my friend’s daughter’s large open closet, stared at the jelly bean–colored clothes hangers, kicked at the bright pink marabou feathers littering the floor. I hoped no one would tell this little girl that her cat had died on her bed.

From the closet, I could see the curve of Maude’s back. And for a second, she seemed to shift ever so slightly. I returned and put my hand on her belly: her fur was moving, rising and falling softly once again. She was still cold, but definitely breathing. The following day, when Maude’s owner returned, she would go to the vet and be put to sleep. But I didn’t know that yet. Relief washed over me, and then exhaustion, and I crawled into my own bed. That was the only time in my life I’ve sat with a dying thing.

Bess Lovejoy is the author of Rest in Pieces: The Curious Fates of Famous Corpses. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, The Believer, The Wall Street Journal, Time, Lapham’s Quarterly, Slate, The Boston Globe, and elsewhere.

The What Will Save You Factor

At our Spring Revel last month, John Jeremiah Sullivan presented the Hadada Award to Frederick Seidel. Sullivan’s remarks follow, along with three of Seidel’s poems, which were read aloud that night: “Downtown,” read by Zadie Smith; “Frederick Seidel,” read by Martin Amis; and “The Night Sky,” read by Uma Thurman.

As a kind of offsite, ersatz staff member at The Paris Review, I claim the pleasure both of thanking you all for your presence here, and of thanking everyone at the Review—Lorin, and the board, and my colleagues there—for giving me the honor of announcing this award. I don’t think I’ve ever used the word honor in a less glib manner.

When you are in your twenties and living in the city, or any city, or anywhere, and trying to write, there are poets whose work will come to mean something to you beyond pleasure, beyond even whatever we have in mind when we use the word inspiration, and into the arena of survival, into what the poet whose work we are celebrating tonight describes as the “what will save you factor.”

When I was in my twenties and living in New York, the poet who came to mean that for me and a lot of the other younger writers and editors I knew was one named Frederick Seidel, a poet who had come, like another we’d heard about, from St. Louis via Harvard, and from there, via everywhere.

He wasn’t ours, wasn’t a peer, I mean, not a Rimbaud or a Plath suddenly stalking among us, using the cover of brashness to say things we’d never allowed ourselves to say, but rather a man then entering his late sixties, whose work had been known and respected and at times viciously attacked for decades, but which seemed to be entering a phase of new intensity. Or possibly we were just hearing about it for the first time.

At moments he could seem like a coterie poet—as if the people you knew who’d read him, were the only people who’d read him—but at others you’d get the feeling that no matter where you went, no matter where in the world, there’d be someone who’d give you the look, when you brought up his name, the look that said they’d been there, had undergone the exquisite and occasionally searing experience of reading Seidel’s poems.

It’s easy for me to say exactly what struck me about those poems the first time I encountered them. I was someone who had attended a lot of poetry readings in the 1990s, on college campuses and in bookstores—I worked as a lackey at a writer’s conference for a few years, where serious poets would blow through, and I even convinced myself for a while that I could write poems—which is only to say that the sound of American poetry, the ground note of it, was very clear in my head when I moved to the city. And it was impossible to deny—maybe you could deny it to others, but not to yourself—that there was something missing, something that might just be essential to the whole business. The sealed-in nature of the poetry world had taken a certain kind of risk out of things, a certain kind of danger, and as a result, a certain kind of consequence. Not to say that there weren’t excellent poets working, but when they went up to the podiums and cracked open copies of their own books, there was often an uncomfortable sense that it was all taking place between giant, invisible quotation marks, and the very theme of too many poems seemed to be: the hope of having something to say. Of sounding like what great poetry might sound like, would sound like.

But these poems, these Seidel poems, were nothing like that. Indeed they seemed to come from outside that entire sphere of concern. They were not worried about having something to say. They knew they had plenty to say, that there was always plenty to say—about love, sex, politics, murder, beauty, money, death, and motorcycles—it was whether a person could say it. To do that took both work—the work of perfecting a style—and courage, the courage of writing what seemed most true. Not what is true, mind you—we don’t get to know “what is true”—but what seems most true, which is a harder task, because it can be done, and therefore failed at, and because it hurts. This poet was asserting what felt like an ancient right, a right to sing out of the deepest self—to write painfully ugly things, and to write painfully beautiful things, but not to write a single thing that he didn’t mean, that didn’t scare him. Lou Reed sang, about Andy Warhol, “I scared myself with music, you scared yourself with paint.” Seidel scared himself with poetry, and us too. How had he done it? How had he dared? That’s a question for his biographers. All I know is that once you’d heard his voice, there was no turning around from it, no tricking yourself into thinking you hadn’t heard it. The voice was sardonic, and it could be satanic, and it was sacred.

Sometimes the writers you love in your twenties turn out to be writers you can love only in your twenties, and I do remember wondering, back then, what we would think of Seidel’s work in ten years, or in twenty years. He settled the question by somehow, implausibly, getting better. He had warned us that he would, I suppose. Hadn’t this writer told us, years ago, that he takes for his motto, “I rot before I ripen”? He ripened. In 2006, he wrote Ooga-Booga. He wrote “The Death of the Shah,” the first undeniable, capital-G Great American Poem of the twenty-first century. And he has not slowed down. Incredibly, when we started talking about which poems to include in tonight’s short reading, we found ourselves leaning toward new material. But wound up choosing something a little older, something relatively recent, and something brand new, from just a few months ago.

1. DOWNTOWN

July 4th fireworks exhale over the Hudson sadly.

It is beautiful that they have to disappear.

It’s like the time you said I love you madly.

That was an hour ago. It’s been a fervent year.

I don’t really love fireworks, not really, the flavorful floating shroud

In the nighttime sky above the river and the crowd.

This time, because of the distance upriver perhaps, they’re not loud,

Even the colors aren’t, the patterns getting pregnant and popping.

They get bigger and louder when they start stopping.

They try to rally

At the finale.

It’s the four-hundredth anniversary of Henry Hudson’s discovery—

Which is why the fireworks happen on this side of the island this year.

Shad are back, and we celebrate the Hudson’s Clean Water Act recovery.

What a joy to eat the unborn. We’re monsters, I fear. What monsters we’re.

We’ll binge on shad roe next spring in the delicious few minutes it’s here.

2. FREDERICK SEIDEL

I live a life of laziness and luxury,

Like a hare without a bone who sleeps in a pâté.

I met a fellow who was so depressed

He never got dressed and never got undressed.

He lived a life of laziness and luxury.

He hid his life away in poetry,

Like a hare still running from a gun in a pâté.

He didn’t talk much about himself because there wasn’t much to say.

He found it was impossible to look or not to.

It will literally blind him but he’s got to.

Her caterpillar with a groove

Waits for love

Between her legs. The crease

Is dripping grease.

He’s blind—now he really is.

Can’t you help him, gods!

Her light is white

Moonlight.

Or the Parthenon under the sun

Is the other one.

There are other examples but

A perfect example in his poetry is the what

Will save you factor.

The Jaws of Life cut the life crushed in the compactor

Out.

My life is a snout

Snuffling toward the truffle, life. Anyway!

It is a life of luxury. Don’t put me out of my misery.

I am seeking more Jerusalem, not less.

And in the outtakes, after they pull my fingernails out, I confess:

I do love

The sky above.

3. THE NIGHT SKY

At night, when she is fast asleep,

The comet, which appears not to move at all,

Crosses the sky above her bed,

But stays there looking down.

She rises from her sleeping body.

Her body stays behind asleep.

She climbs the lowered ladder.

She enters through the opened hatch.

Inside is everyone.

Everyone is there.

Someone smiling is made of silk.

Someone else was made with milk.

Her mother still alive.

Her brothers and sisters and father

And aunts and uncles and grandparents

And husband never died.

Hold the glass with both hands,

My darling, that way you won’t spill.

On her little dress, her cloth yellow star

Comet travels through space.

The Sound of Pure Internet, and Other News

Photo: Fleshas, via Wikimedia Commons

One of the finest World War II documentaries, 1945’s The Battle of San Pietro, was faked. Does this make it less true?

Here’s what it was like to attend a literature seminar taught by Philip Roth in the seventies: “He barely looked at us or made eye contact, but murmured a hello, then sat down in his chair, crossed one long leg over the other, and slowly unbuckled his watch. That’s as sexy as it got.”

“Does journalism fit into capitalism? … Journalism does exist in capitalism, and capitalism is kicking journalists’ asses. The same goes for editors, and for many publications.”

Matt Parker, a sound artist, has been touring data hubs—those epicenters of the Internet, where all our e-stuff takes physical form—and recording the ethereal hum they give off. The result: “musical renderings of the great churn … an incredibly loud and obnoxious place filled with white noise and buzzing hard drives.”

Analyzing the artisanal toast trend: “Artisanal toast is hardly the first harbinger of our food obsession, or even necessarily the most egregious, but it’s become a scapegoat for a growing, broader cultural backlash; the toast that broke the camel’s back.”

May 5, 2014

A Little Circus

American Masters’s Plimpton! Starring George Plimpton as Himself premieres nationally Friday, May 16, on PBS. The network has released a few short clips in advance, and they paint a pretty picture of life at the Review under the Plimp’s tenure. The portion above finds Robert Silvers, Jonathan Dee, and others reflecting on Plimpton’s business acumen—or triumphant lack thereof—and the relaxed tenor of his leadership. “I think it meant a lot to him to have this kind of camp,” Silvers says. “It was a whole little world, you might say. And he was the king of it. And he was a ringmaster, you might say, of a little circus there.”

Below, Peter Matthiessen, who died last month and who had been the last living founder of the Review, discusses the magazine’s ambitions—its approach to fiction and poetry, and its early coups with interviews.

Escapism

Today on HuffPo books, Jay Crownover discusses the different subcategories of the “literary bad boy,” which include “The Unattainable” (Sherlock Holmes), “The Nonconformist” (Holden Caulfield, of course), “The Alpha” (Achilles), “The Lothario” (Bond), “The Misunderstood” (Ponyboy from The Outsiders), and, in a bold move, “The Anti-Hero,” as represented by Hannibal Lecter.

It is hard not to wrestle, increasingly, with the listicle-ization of lit, the too-easy shorthand of Virginia Woolf finger-puppets, cheeky pro-book tote bags, Dickens bibs, and twee-pop-Brontë mashups. There is reading, and then there is reading as signifier, in which we don’t lose ourselves in books themselves so much as turn them into easy, quotable advertisements for ourselves. Sexy librarians? Sure. “Keep Calm and Read On”? Okay. “What Would Jane Austen Do”? How about live two hundred years ago in an unrecognizable world with a completely different set of mores? How much less scary when Lady Chatterley’s Lover is not a cultural battleground but just a vintage cover on a T-shirt.

That said, I wear my Jane Eyre T-shirt. I covet the Barbara Pym doll on Etsy. I love to see a cat reading the classics as much as, if not more than, the next guy. Like, I imagine, most of us, I am glad of anything that makes books approachable and appealing, so long as we don’t forget their power. (And yes, I immediately did ask myself, “What Is Your Literary Bad Boy Type?”)

Richard Hoggart, the academic who was instrumental in ending the censorship of Lady Chatterley’s Lover in Britain, died last month. In his testimony at the 1960 obscenity trial, the cultural historian said of the book’s depiction of sex, ”The first effect, when I first read it, was some shock, because they don’t go into polite literature normally … Then as one read further on, one found the words lost that shock. They were being progressively purified as they were used.” It was a different world, yes, and it is perhaps too easy to point to the Lady Chatterley’s Lover lampshade, or locket, or sweatshirt you can now buy, and wonder about the nature of progress. And the difference between “purifying” and “diluting,” and whether, in the end, both are inevitable in the march from the forbidden to the merely “bad.”

John Jeremiah Sullivan Wins James Beard Foundation Award

Photo: PatríciaR, via Wikimedia Commons

Congratulations to our Southern editor, John Jeremiah Sullivan, who’s been honored with the James Beard Foundation’s MFK Fisher Distinguished Writing Award for his essay “I Placed a Jar in Tennessee.”

The James Beard Foundation awards are presented “for excellence in cuisine, culinary writing, and culinary education.” “I Placed a Jar in Tennessee” appeared in the Winter 2013 issue of Lucky Peach; it tells the story of Kevin West, who has recently discovered, or perhaps rekindled, a family passion for home-preserving and pickling. If the title strikes you as familiar but unplaceable, fear not, for I have done your googling for you—it refers to Wallace Stevens’s famous poem “Anecdote of the Jar,” first published in 1919:

I placed a jar in Tennessee,

And round it was, upon a hill.

It made the slovenly wilderness

Surround that hill.

The wilderness rose up to it,

And sprawled around, no longer wild.

The jar was round upon the ground

And tall and of a port in air.

It took dominion every where.

The jar was gray and bare.

It did not give of bird or bush,

Like nothing else in Tennessee.

Recapping Dante: Canto 28, or Unseamly Punishments

Gustave Doré, Canto XXVIII

We’re recapping the Inferno. Read along! This week: Mohammed torn asunder.

Canto 28 opens with a very self-conscious address by Dante. He tells the reader that even if his writing weren’t constrained by the dictates of meter and form, he still would’ve had trouble describing the following scene. But he had no idea what he was talking about: canto 28 is marvelous and harrowing. Canto 28 is perfect.

He begins by listing famous battlefields—if all the mangled bodies and limbs and guts from all these vicious wars were combined, he says, they would pale in comparison to the ninth pit of hell. The first thing he sees here is a man “cleft from the chin right down to where men fart.” What’s remarkable about this line is not that a poet as great as Dante would use the word fart—although, let’s face it, that is sort of funny—but that it’s almost identical to a line that Shakespeare would write many centuries later, in Macbeth: “unseamed … from the nave to th’ chops.”

Our unseamed sinner—with his entrails and “loathsome” “shit” sack torn asunder—is Mohammed, who tells Dante that this pit is reserved for those who “sowed scandal and schism.” The Hollanders point out that Dante must therefore have seen the prophet not as the founder of a new religion, but as the catalyst for the schism that would branch off from Christianity and become Islam.

Mohammed explains how punishment works around here. He and his fellow mangled sinners eventually find that their injuries have healed—but once they’re all closed up, they’re mangled yet again by a demon. The punishment is not simply about pain and suffering, to say nothing of the inconvenience of having to carry your colon in your hands; the indignity of being mangled is equally important. Mohammed believes, for some reason, that Dante and Virgil are dead and simply taking a tour of hell before being punished. Clearly, Mohammed hasn’t quite grasped the way hell works.

As Dante and Virgil continue walking, they come across another gruesome scene. A sinner named Pier da Medicina, who recognizes Dante, has been wounded so badly that sound can no longer leave his mouth, and he must hold open his windpipe to speak. This Pier, like the famous bleeding tree in canto 13, is singularly pathetic and pitiable: “Should you ever see that gentle plain again that slopes from Verceli down to Marcabò,” he says, “for Pier da Medicina spare a thought.” It is a melancholy phrase from a sinner we don’t get to know well, and whom all of history, except for Dante, has forgotten. The simplicity and intimacy of his request makes us pity him—he wants to be remembered in the most obscure manner. And now, thanks to Dante, this Pier lives forever in that little realm on earth, and any time we see the slopes from Verceli down to Marcabò, we who have read Dante will also have to spare a thought for a man we never knew.

The poet and pilgrim go on to speak with another sinner whose severed hands are spurting steady streams of blood. This man is a Ghibelline whose actions played a great part in starting the feud between the two parties that divided Florence. After a crime like that, it sort of seems like his punishment leaves him off easy.

But before Virgil and Dante leave, the two see something that still manages to overshadow the unseamed Mohammad, the unfolded talking windpipe, and the blood hoses coming from a man’s wrists: they see a headless figure approaching them, holding his own head by the hair like a lantern. It’s a scene that can be met in darkness only by Caravaggio’s painting of David holding the head of Goliath. The sinner is Bertran de Born, a poet who wrote in Provençale and who, according to the Hollanders, took a great deal of pleasure in seeing towns leveled. (Dante will meet another Provençale poet in Purgatorio—Arnaut Daniel, who will actually speak in Provençale.) Bertran de Born’s sin was turning Prince Henry against his father, Henry II.

The last line in canto 28 mentions contrapasso, which is, simply put, the idea that the punishment should fit the crime. Dante is devoted to the concept. Think about it: Bertran de Born’s head was separated from his body as he “severed persons thus conjoined.” Fire falls down on sodomites as it did on Sodom; suicides lose their bodies in the afterlife; the lustful in hell are tormented with weird forms of sex deprivation. It starts to make a lot of sense, doesn’t it?

To catch up on our Dante series, click here.

Alexander Aciman is the author of Twitterature. He has written for the New York Times, Tablet, the Wall Street Journal, and TIME. Follow him on Twitter at @acimania.

The Origins of Barbecue, and Other News

Photo: Derrick Tyson, via Flickr

The secret libraries of New York. (None of them are technically secrets, but “the comparatively less well-known libraries of New York” doesn’t have the same ring to it.)

“A surveillance society … threatens our interiority, our right to a private self that ensures we can never be fully transparent, to others or to ourselves. In a culture driven to render us ever more transparent to one another, literature and art may be among the few spaces in which to keep hold of this understanding of the private self.”

On the disappearance of spectacular cinema: “As the bulk of filmmaking has shifted away from studio productions and virtually all movies except for franchises have become, in effect, independent films, movies have fallen into conflicting extremes of artifice and of reality, and the idea of reality has become a sort of critical cult.”

“The first indigenous tribes Christopher Columbus encountered on the island he named Hispaniola had developed a unique method for cooking meat over an indirect flame, created using green wood to keep the food (and wood) from burning. Reports indicate that the Spanish referred to this new style of cooking as barbacoa: the original barbecue.”

These statues are very, very, arrestingly large.

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers