The Paris Review's Blog, page 712

April 25, 2014

Warhol via Floppy Disk, and Other News

Andy Warhol, Andy2, 1985, ©The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc., courtesy of The Andy Warhol Museum

Shakespeare: playwright, poet, armchair astronomer. “Peter Usher has a very elaborate theory about Hamlet, in which the play is seen as an allegory about competing cosmological worldviews … Claudius happens to have the same name as Claudius Ptolemy, the ancient Greek mathematician and astronomer who we now associate most closely with the geo-centric Ptolemaic worldview.”

From the mideighties: Andy Warhol’s rediscovered computer art.

New research by the University of California-San Diego’s Rayner Eyetracking Lab—nobody tracks eyes like the Rayner—suggests that speed-reading apps might rob you of your comprehension skills.

“I have been surreptitiously scrutinizing faces wherever I go. Several things have struck me while undertaking this field research on our species. The first is quite how difficult it is to describe faces … We might say that a mouth is generous, or eyes deep-set, or cheeks acne-scarred, but when set beside the living, breathing, infinitely subtle interplay of inner thought, outward reaction and the nexus of superimposed cultural conventions, it tells us next to nothing about what a person really looks like.”

In Germany, business is booming. The secret: pessimism. “German executives are almost always less confident in the future than they are in the present.”

Discovered in an archive of the LAPD: more than a million old crime-scene photographs, some of them more than a century old.

April 24, 2014

Medical Expert Evidence

It’s late, and you’re still awake. Allow us to help with Sleep Aid, a series devoted to curing insomnia with the dullest, most soporific prose available in the public domain. Tonight’s prescription: “Medical Expert Evidence,” a treatise first published in Lippincott’s Magazine of Popular Literature and Science in April 1873.

Albert Anker, Zwei schlafende Mädchen auf der Ofenbank Date, 1895

There is scarcely any position of more responsibility than that of the medical expert in cases of alleged poisoning. Often he stands with practically absolute power between society and the accused—the former looking to him for the proof of the crime and for the protection which discovery brings; the latter relying upon him for the vindication of his innocence. How profound and complete, then, should be his knowledge! how thorough his skill! how pure and spotless his integrity! how unimpeachable his results! Yet recently the humiliating spectacle has been repeatedly presented of expert swearing against expert, until the question at issue was apparently degraded into one of personal feeling or of professional reputation. So far has this gone that both judicial and public opinion seems to be demanding the abolition of expert testimony. The medical expert must, however, remain an essential feature in our criminal procedures, partaking as he does of the functions of the lawyer, inasmuch as he has, to some extent, the right to argue before the jury, partaking also of the judicial character in that it is his duty to express an opinion upon evidence, but differing from both judge and advocate in that as a witness he testifies to facts. Were the attempt made to do away with his functions, there would be an end to just convictions in the class of cases spoken of, because no one would be qualified to say whether any given death had been produced by poison or by a natural cause.

In many matters that come under the notice of medical experts there is room for honest differences of opinion. Of such nature are questions of sanity and insanity. It must be remembered that these are, after all, relative terms. Reason leaves its seat by almost imperceptible steps. Who can determine with exactness the line that separates eccentricity from madness—responsibility from irresponsibility? Moreover, the phenomena upon which opinion is based are, in such cases, so hidden, so complex, so obscure, that in the half-lights of a few short interviews they will often be seen differently by different observers.

In scarcely any of its parts does toxicology belong to this class of subjects—certainly not at all in so far as it deals with mineral poisons. To a great extent it is a fixed science—a science whose boundaries may be widened, whose processes may be rendered more delicate, but whose principles are in great measure settled for ever. Not in the imperfections of the science, but in the habits of the American medical profession and in the methods of our criminal procedures, lies the origin of the evils complained of.

Some of the causes of the present difficulties are readily to be seen. One is the common ignorance of legal or forensic medicine among the members of the profession. In none of our medical colleges is legal medicine taught as a part of the regular course or as an essential branch of study. Consequently, when the student graduates he has only heard a few passing allusions to the subject from professors of other branches. Unfortunately, this is more or less true of many other medical subjects of importance: helped out, however, by his mother wit, and impelled by necessity, the imperfectly-educated graduate after a time becomes very generally a skillful practitioner. During the period of growth his daily needs govern the direction of his studies, which are therefore more or less exclusively confined to the so-called practical branches. Forensic medicine is not one of these, poison cases are comparatively rare, and to be called upon to give a definite opinion upon such matters before a legal tribunal happens not once in the lifetime of most medical men. Consequently, to a great part of the American medical profession legal medicine is a veritable terra incognita.

Moreover, the whole drift of modern medicine is toward a division of labor, and forensic medicine is more widely separated from the ordinary specialties of the science than these are from one another. In a case of delicate eye-surgery who would value the opinion of a man whose attention had been devoted mainly to thoracic diseases? What specialist of the latter character would even offer an opinion? Yet physicians who acknowledge that they have paid no especial attention to toxicology do not hesitate to give the most positive opinions upon the most delicate questions of that science. Men who would, as in honor bound, ask for a consultation in any case of serious sickness outside of their line of private practice, on the witness-stand put forth with the utmost boldness their ignorant crudities, careless or forgetful of the fact that they may be imperiling the life of an innocent human being. On the trial of Mrs. Wharton for the attempted murder of Mr. Van Ness, Dr. Williams asserted that there are peculiar characteristic symptoms or groups of symptoms of tartar emetic poisoning; and both he and Dr. Chew—who with frankness acknowledged that he had not especially studied toxicology—did most positively recognize tartar emetic as the sole possible cause of certain symptoms which were but a little beyond the line of medicinal action, and for which obviously possible natural cause existed. Contrast these bold opinions with the cautious statement of a man who had given a lifetime of study to this particular subject. On the trial of Madeleine Smith, Professor Christison—at that time the first toxicologist of England—stated that if in any case the symptoms and post-mortem appearances corresponded exactly with those caused by arsenic, he should be led to suspect poisoning.

Another source of mischief lies in the fact that the law does not recognize the well-established principles of forensic medicine, and consequently the books in which these principles are laid down by the highest authorities are excluded by the courts, while the vivâ voce evidence of any medical man, however ignorant on such points, is admitted as that of an expert.

It is therefore not to be wondered at that juries give but little consideration to the knowledge or professional standing of expert witnesses. It is, in fact, notorious that the medical autocrat of the village, who has superintended the entrance of the majority of the jurymen into this troublous world, is a more important witness than the most renowned special student of the branch: indeed, the chief value of the real expert often rests on his ability to influence the local physician. At the late Wharton-Van Ness trial the defence desired to show that the work of the chemist employed by the prosecution was unreliable, because the analyses made by him in a previous case had “been condemned by the united voice of the whole scientific world.” The court was not able to see the relevancy of this, and refused to allow the professional ability or standing of an expert to be called in question. The witness thus adjudged competent brought no results into court; had kept no laboratory notes; relied solely on a memory so deficient that although he had been teaching for thirty-five years, he could not tell the shape of a crystal of tartar emetic, the poison in question; and upon the stand made a statement different from one which he had furnished officially to the district attorney of Baltimore fourteen months before.

There are principles of toxicology which ought to have legal force and recognition, and ought to govern expert testimony in the same way that the principles of evidence govern ordinary testimony. Without presuming to enumerate these, I will cite two or three for illustration. Certain substances, the so-called irritant poisons, such as arsenic, tartar emetic and the like, induce their toxic effects by causing irritation and inflammation of the alimentary canal. All authorities agree that poisoning by these substances cannot be proved, or even rendered, very probable, by symptoms alone—that chemical evidence, the discovery of the poison in the food, dejections, or in case of death the body, is absolutely essential for making out a case. Irritation and inflammation of the alimentary canal occur so often and so suddenly from natural causes, which are sometimes apparent, but often hidden, that no especial weight can be attached to them.

In the case of the so-called neurotic poisons, those which act upon the nervous system, the symptoms are so closely simulated by natural disease that even when they agree in the most absolute manner with those usually developed by any such poison they only render poisoning highly probable, not certain. When in any case the symptoms diverge from the typical array, poisoning becomes improbable just in proportion to the amount of divergence.

All toxicological authorities also agree that in the case of the metallic poisons, such as tartar emetic and arsenic, the metal must be brought into court, and that the so-called “color tests” are not to be relied on. When sulphuretted hydrogen is passed through solutions of these metallic substances colored precipitates are thrown down, which at one time were thought to be absolute proof of the existence of the poison in the original solution. But in the celebrated Donnal case, tried at Falmouth, England, in 1817, Dr. Neale saved the accused by showing that a decoction of onions, of which the deceased had eaten a short time before death, yielded similar precipitates to those relied upon by the prosecution as establishing the presence of arsenic in the stomach. In regard to tartar emetic, Dr. Taylor, in his work on medical jurisprudence, says: “Antimony in the metallic state is so easily procured from a small quantity of material that on no account should this be omitted. A reliance on a small quantity of a colored precipitate would be most unsatisfactory as chemical evidence.” In defiance of all the authorities the prosecution, on the trial of Mrs. Wharton for the murder of General Ketchum, rested its proof of poison upon these color tests and their sequences. The defence, however, found that the counterparts of three out of the four so-called characteristic reactions were readily performed with the substances known to have been in the stomach of General Ketchum at the time of his death.

Several cases of poisoning which have been tried recently in this State and Maryland have attracted much attention, and I propose now briefly to outline these, and show that the disgraceful scenes which have taken place were not due to deficiencies of toxicological science, but to the causes already spoken of.

First in time among these causes célèbres was the Schoeppe case, the facts of which may be briefly summed up as follows: Dr. Schoeppe, a young German practicing medicine in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, became engaged to be married to a Miss Stennecke, a maiden lady of sixty years of age. Miss Stennecke was somewhat of an invalid, not often actually sick, but habitually distressed by dyspeptic symptoms, etc. On the morning of the 27th of January, 1869, feeling unwell, she sent for Dr. Schoeppe, who gave her an emetic. In the afternoon, according to the testimony of her maid, she was weak, but apparently not ill. Between 7 and 8 P.M., however, she became much worse, and her servant noticed that she was very drowsy, so that if left alone she would immediately fall asleep whilst sitting in her chair. Shortly after this she was put to bed, and was not seen again until the next morning about six o’clock, when she was found comatose, with contracted pupils, irregular respiration and complete muscular relaxation. Late in the afternoon of the same day she died quietly.

Nothing was said about poisoning until some days afterward, when, a will having been produced in favor of Dr. Schoeppe, an accusation was made against him. The body of Miss Stennecke was exhumed, and underwent a post-mortem examination, which, for culpable carelessness and inexcusable omissions, stands unrivaled. Not a single organ in the whole body was thoroughly examined, and many of the more important parts were not looked at. Death, preceded by the symptoms exhibited in the case of Miss Stennecke, occurs not infrequently from insidious disease of the kidneys, yet these organs were not taken out of the body. The stomach was examined chemically by Professor Aiken of the University of Maryland, who reported that he had found prussic acid, and who testified on the trial that Miss Stennecke had received a fatal dose of that poison. When, however, his evidence was sifted, it was discovered that he had only obtained traces of the poison by the distillation of the stomach with sulphuric acid. As saliva contains ferrocyanide of potassium, out of which sulphuric acid generates prussic acid, the latter substance will always be obtained by the process adopted by Professor Aiken from any stomach which has in it the least particle of saliva. If, then, the professor did really get prussic acid, without doubt he manufactured it.

Dr. Hermann, however, testified that Miss Stennecke, whom he saw on the morning of her death, must have died of a compound poison, because her eye looked like that of a hawk killed by himself some years before with a dose of all the poisons he had in his apothecary’s shop. Dr. Conrad confirmed the assertion of Dr. Hermann, that Miss Stennecke could not have died from a natural cause, and testified that as the liver was healthy, therefore the kidneys must have been so too—a conclusion which could only have been evolved from his inner consciousness.

In vain Professor Wormley protested, declaring that it was impossible Miss Stennecke could have been killed by prussic acid, because that poison always does its work in a few minutes, if at all, whereas Miss Stennecke lived nearly twenty-four hours after the alleged poisoning. What did it matter that Dr. Conrad had shown himself by his post-mortem examination ignorant of the first rudiments of legal medicine, and that Dr. Hermann was a village doctor of the olden type dragged into court from a mediæval contest with the diseases of simple country-folk, while Professor Wormley had devoted his life to toxicology and achieved a world-wide reputation? What did it matter that the written words of all authorities upon such subjects in every land were in absolute accord with Dr. Wormley? Under the ruling—which has been reaffirmed at Annapolis—the settled principles of science were overborne by ignorant conjecture, and to the mockery of justice, to the deep disgrace of our commonwealth, Dr. Schoeppe was condemned to death upon evidence which, from the same bench, was subsequently stigmatized as being insufficient to warrant his commitment for trial.

Three years of close confinement under the shadow of death followed. The governor refused a pardon, and Dr. Schoeppe heard the hammer driving the nails into his scaffold beneath the prison-window. He was measured for his coffin, but at the last moment was reprieved, and listened to the heavy thud as the drop fell and a man whose companion he was to have been on the scaffold was launched into eternity. Finally, moved by the incessant pleadings of Mr. Hepburn, the junior counsel, by the urgings of the public press, led by the Philadelphia Evening Bulletin, and by the protests of numerous scientific bodies, the legislature passed a special act granting Dr. Schoeppe a new trial. On this occasion the judge allowed the weakness of the expert testimony for the prosecution to be demonstrated, and chiefly as a result of this demonstration—of what has been called the “coarse brutality” of showing Dr. Conrad’s ignorance—Dr. Schoeppe was acquitted.

If the principles contended for in this article had been acknowledged, the processes and results in the case of Dr. Schoeppe would have been far different. In the first place, the post mortem would have been entrusted to some one qualified to make it—an expert in legal medicine—and very probably a natural cause for the death of Miss Stennecke would have been found. Such post mortem not having been made, the case, after Professor Aiken’s analysis, would have been dropped, because it was impossible that prussic acid could have caused the death. Had, however, capable experts failed to detect a natural cause of death, a very serious case might have been made out against Dr. Schoeppe, even though the analyst had not found morphia in the stomach. The prosecution might have affirmed that the poison had been absorbed, and therefore was not in the stomach, and, for the support of the charge, relied upon the resemblance of the symptoms to those produced by morphia, and upon the absence of natural cause of death.

A case which has acquired even more celebrity than the last is that of Mrs. Wharton of Baltimore. The chief facts, as developed at the first trial at Annapolis, are as follows: General Ketchum, a man of over middle age and usually in good health, was very much engaged in attending to matters of business at Washington throughout the entire day of the 24th of June, 1871. The weather was very hot, yet he walked about hurriedly and steadily, getting no dinner, and returning in the evening to Mrs. Wharton’s at Baltimore about 9 P.M., where he ate a very hearty meal, consisting partly of raspberries. During the night he was heard to go down stairs several times. The next day he complained of feeling unwell, but took at bed-time a glass of lemonade with brandy, and during the night had some slight vomiting and purging. In the morning he complained of sick stomach and giddiness, and at Mrs. Wharton’s earnest request Dr. Williams was finally sent for, and on arriving at 4 P.M. found him sitting up and vomiting, and prescribed as for a slight attack of cholera morbus. The next morning General Ketchum thought himself so much better that he discharged his physician. He was, however, very drowsy during the day, and the evidence at the trial rendered it probable that he took laudanum on this day upon his own responsibility. In the evening he was found sleeping heavily upon the lounge, and again at Mrs. Wharton’s request Dr. Williams was sent for, but did not think it worth while to come. The next morning Mrs. Wharton again sent for Dr. Williams, as General Ketchum was found still lying upon the lounge in a stupor. He remained in this state until his death, which took place in a convulsion at 3 P.M. He had had during the intervening period repeated convulsions, and about one o’clock had become very uneasy, uttering incoherent cries, but did not recover true consciousness. At the examination of the body, made the following morning, the spinal cord was not looked at: the inner membranes of the brain were found congested, and the brain-substance presented throughout “those dark points of blood which indicate passive congestion.” No other lesions were found, and the stomach was handed for analysis to Professor Aiken, who in due time reported that he had “satisfied himself” of the existence of at least twenty grains of tartar emetic in it.

It is highly probable that this official announcement had much influence upon the minds of Drs. Williams and Chew, with their colleagues, and it is very certain that by it and their representations was created the public belief in Baltimore that General Ketchum had been poisoned. The false analysis remained for months uncontradicted, and backed up as it was by the whole intellectual and moral force of the University of Maryland, it could scarcely happen otherwise than that public opinion should become so set and hardened that no testimony at the trial could affect it, especially as local pride and local prejudice came to its support when experts from other cities questioned the work of the Baltimore physicians.

Mrs. Wharton’s servants were first accused, but after a few days she was arrested, and with her daughter—who has clung throughout to her faith in her mother’s purity and goodness—was thrust into a common felon’s cell, with only the grated bars between her and the lowest of men in every stage of drunkenness and delirium. After nearly two weeks her lawyers obtained her removal to one of the better rooms of the jail, but it was months before anything was said in her favor.

The trial opened on December 4, 1871, at Annapolis, and lasted nearly two months. The circumstantial evidence certainly went no farther than to render it probable that if General Ketchum died of poison it was administered by Mrs. Wharton. The State attempted to prove as a motive that Mrs. Wharton owed the deceased money. They were signally unsuccessful in this, however; so that a very intelligent member of the jury said to the writer since the trial, “Whether Mrs. Wharton did or did not poison General Ketchum, certainly the State completely failed to prove a motive.” The defence admitted that Mrs. Wharton had bought tartar emetic near the time of the alleged poisoning, but proved that she was in the habit of using it externally as a counter-irritant, and that it was purchased in the most open manner, through a third party, not with the secresy that marks the steps of the poisoner.

Thus the whole case centred in a rather remarkable degree upon the expert testimony, and the very point of it all was the chemical analysis. This is not the place to follow out in detail the scientific testimony, but only to point out some peculiarities of it. Almost all the medical witnesses for the prosecution were colleagues of Professor Aiken, none of them men of eminence in toxicological science—surgeons, physiologists, obstetricians, the whole faculty, trying apparently to hide the nakedness of their colleague. Never was strong language more justifiable than that of Mr. Hagner, when he said, “It seemed that the University of Maryland was on trial, and that blood was demanded to support it.”

After all, the testimony of most of these gentlemen amounted only to this: that they did not believe the death of General Ketchum could have occurred from natural causes. On the other hand, the numerous medical witnesses for the defence, unconnected by any bond of common interest, testified that natural causes, were sufficient to account for the death; many of them asserting that the case in all its symptoms and post-mortem appearances tallied precisely with the so-called fulminating form of cerebro-spinal meningitis, which was prevalent in Baltimore at the time of General Ketchum’s death.

The medical witnesses for the defence further called attention to the fact that the symptoms of General Ketchum’s illness were wholly different from those produced by tartar emetic, and some denied that the latter could have caused the sickness. The chemical evidence for the prosecution was triumphantly refuted. It was shown that antimony did not conform in its reactions with at least one of the tests, which Professor Aiken said his precipitates did; that almost all the other reactions could be closely simulated with ordinary organic bodies; that the processes used were those universally condemned by authorities; and that carelessness was everywhere so manifest in their conduction as to entirely vitiate any results. It was also proved that Professor Aiken had simply estimated the amount of tartar emetic in General Ketchum’s stomach by the ocular comparison of the bulk of precipitates, neither of which could have been pure, and in neither of which was the existence of antimony really proved. To weigh a precipitate was a labor not to be thought of when nothing more important than the life of a woman was involved: guessing was all that such a trifling issue demanded!

The most extraordinary event of this most extraordinary trial occurred when the chemists for the defence had completely broken down the testimony of Professor Aiken. With the knowledge, it is said, of at least one of the judges, without the presence of a representative of the defence, or even of a legal officer, the body of General Ketchum was secretly exhumed by the doctors who had shown themselves so eager for the execution of Mrs. Wharton. The viscera, which they removed, were put into the hands not of a chemist of national reputation, but of an individual who had been advanced from the position of hospital steward at Washington to that of professor of chemistry in a small local institute at Baltimore. This professor, when on the witness-stand, was singularly confused as to his weights and measures, and finally shared the ignominy of his predecessor. The defence had several chemists at Annapolis of world-wide reputation and unspotted integrity. If the prosecution really believed that General Ketchum had been poisoned, if they really did expect tartar emetic to be found, why did they not allow the presence of these gentlemen at the analysis, and thereby ensure the condemnation of Mrs. Wharton? The conviction is irresistible that they were afraid of the truth—that they were simply determined to procure the desired verdict at all hazards and by any means. Yet this was the procedure for the completion of which the court suspended the trial for two days, because, as Chief-Justice Miller stated from the bench, “it thought the ends of justice demanded it”! Is any further evidence needed of the strange ideas, of the perversion of truth and justice, which have grown out of the American method of using expert testimony?

Before leaving this trial I desire to quote from advanced sheets of the edition of Dr. Taylor’s great work on medical jurisprudence, now passing through the press. Reviewing the trial in London with that freedom from bias which the isolation of distance produces, he says: “The trial lasted fifty-two days, and an astonishing amount of evidence was brought forward by the defence and prosecution, apparently owing to the high social position of the parties, for there is nothing, medically speaking, which might not have been settled in forty-eight hours. The general died after a short illness, but the symptoms, taken as a whole, bore no resemblance to those observed in poisoning with antimony; and but for the alleged discovery after death of tartar emetic in the stomach, no suspicion of poisoning would probably have arisen... The chemical evidence,” he adds, “does not conflict with the pathological evidence, for it failed to show with clearness and distinctness the presence and proportion of poison said to have been found. The evidence that antimony was really there was not satisfactory, and that twenty grains were in the stomach wholly unproven.”

What would have been the course of this trial if expert testimony were established upon proper principles? Professor Aiken having shown his complete incompetency in the Schoeppe case, the analysis would have been entrusted to some skillful chemist, who by failing to discover poison would have established the innocence of Mrs. Wharton, or by bringing positive results into court have ensured conviction; or, Dr. Aiken having made the analysis, and having broken all the laws of toxicological evidence, his testimony would have been ruled out, and the case dismissed because the bungling of the State’s witness had destroyed the evidences of guilt or of innocence.

In January, 1873, Mrs. Wharton was tried at Annapolis for attempting to poison Eugene Van Ness. The facts of the case are briefly as follows: Mr. Van Ness, whose relations with the Wharton family had been extremely intimate for many years, was a bank-clerk, but during the spring and early summer of 1871, besides attending to his regular duties, was employed in settling a large estate. He habitually rose early, often at 5 A.M., and generally worked until eleven o’clock at night. During this period he suffered from severe nervous headaches, and probably from other symptoms of an overworked nervous system, but on this point the testimony disagreed. His stomach is at all times so sensitive that brandy nauseates him. On the 19th of June, after taking some claret on an empty stomach at Mrs. Wharton’s, he felt very badly, suffering from lightness of the head or giddiness and general wretchedness, with stiffness and numbness in the back of his neck. On the 20th he stopped at Mrs. Wharton’s about 4 P.M., having eaten nothing for seven or eight hours, and took raspberries with cream, and drank claret. This claret, he stated, “had a taste like peach leaves.” Directly after this he had an attack similar to, but much more violent than, that of the day before. Some little time after this, whilst in a condition of profound relaxation, he took some brandy, and at once emptied his stomach by a single spasmodic effort of vomiting, with immediate relief. The weather was extremely hot during the whole time in which the various attacks here narrated took place.

On the 24th of June, Mr. Van Ness rose at 5 A.M., but was forced to return to bed by a severe headache. At 9 A.M., after dressing, he said to his wife that he would not eat at home, but would stop at Mrs. Wharton’s on his way to the office, to get a cup of her “nice black tea.” A piece of toast was all he ate before his return to Mrs. Wharton’s from the banking-house at 4 P.M. Mrs. Wharton then offered him some lager beer, and, partly at his own suggestion, put into it something out of a bottle labeled “Gentian Bitters.” He found the liquid so bitter that he took but a part of it.

Shortly afterward Mr. Van Ness became partially blind, and was “seized with the same feeling of giddiness” as on the day before. After this he had convulsions, with unconsciousness, for which large doses of chloroform and chloral were given. During the attack the patient repeatedly said it was of the same character as the preceding ones, and referred the trouble to the pit of the stomach and to indigestion.

The next morning (Sunday), about an hour after waking, he took some tea and toast, and in ten minutes was seized with nausea, followed by heartburn and retching, which lasted all day. On Monday morning some beef tea—two-thirds of a cupful—was given him, and in less than an hour as much more, which induced nausea with heartburn. In the evening he was roused, and more beef tea offered him, which he refused because the last dose had made him sick, and he was afraid this would have the same effect. He was, however, prevailed on to take it. After this he fell asleep, but in a short time woke up with violent nausea, burning at the pit of the stomach, and finally vomiting. Not until this occurred did he discover anything wrong with the beef tea: as he vomited it he found it had an acrid metallic taste.

The circumstantial evidence in the case did not amount to any more than, or indeed as much as, in the previous trial. It was distinctly admitted that no motive could be found, Mr. Van Ness testifying that the relations between himself and Mrs. Wharton were most friendly; that he held four thousand dollars of her government bonds, for which she had not even a receipt; that she depended upon him for the completion of her pecuniary arrangements for a contemplated trip to Europe; or, in other words, that she had nothing to gain and much to lose by his death, and that there was no conceivable emotional motive, such as hate, revenge or envy.

No attempt was made to prove that Mrs. Wharton had at any time in her possession strychnia, the poison alleged to have been used by her. As on the previous trial, the case centred upon the expert testimony, but there was no direct chemical evidence, neither the food, the matters vomited nor the bodily secretions having been examined. Some sediment found in a tumbler of punch was asserted by Dr. Aiken to consist largely of tartar emetic. This tumbler was not connected with Mrs. Wharton, except by being found at her house in a position where, in the language of one of the State’s witnesses, “hundreds of persons” had access to it. It was carried about in the pocket of a lady inimical to Mrs. Wharton, and into at least one drug-store, before it reached Professor Aiken, whose analysis was as faulty as before. Any tartar emetic present in the sediment might have been procured in a pure form by the simple process of dialysis. The only apparatus necessary for this would have been a glass vessel divided into two compartments by a piece of hog’s bladder stretched across it. These chambers having been partially filled with distilled water, and the sediment of the tumbler put into one of them, the tartar emetic would have left the other ingredients and passed into the second compartment. By taking the water out of this and evaporating it, the poison would have been obtained in a pure crystalline state, and might have been brought into court. But Dr. Aiken thought it sufficient for him to “satisfy himself”: as he stated on the witness-stand, he did not consider it his business whether other people were or were not satisfied. Consequently, the court was only favored with a memorized report of the color tests used by him, exactly as in the previous trial. One of the reactions which he said he obtained antimony does not conform to.

Drs. Williams and Chew unhesitatingly stated on the witness-stand that they recognized poisoning as early as the Saturday of Mr. Van Ness’s illness. Yet they gave no antidote. They employed on Monday and Tuesday a treatment which, although well adapted to a case of natural disease presenting such symptoms, would in a case of poisoning have materially increased the risk to life. They did not save the matters vomited: they did not save the secretions, which would certainly have contained antimony if Mr. Van Ness had been poisoned as alleged. According to their testimony, Mr. Van Ness received six doses of poison on as many different days, four of the doses administered under their eyes; yet they gave no warning to the unfortunate victim or to his friends. If the theory they upheld be correct, that Mrs. Wharton poisoned both General Ketchum and Mr. Van Ness, the extraordinary spectacle was presented of one man lying dead in the house from the effect of poison, of another receiving day after day the fatal dose with the knowledge of the attending physician, yet no antidote given, no warning word put forth, no saving of the evidences of guilt! It would seem as though silence at a trial would best become gentlemen with such a record, yet they were the only experts who asserted that strychnia was the sole possible cause for the attack of the 24th of June, and tartar emetic of the subsequent attacks.

The experts for the defence asserted that the convulsion of Saturday could not have been caused by strychnia or other known poison; that although the symptoms of the later attacks resembled those of tartar emetic poisoning, they were not identical with those usually produced by that drug; and that it was exceedingly improbable that these attacks were due to the poison named, because obvious natural causes for them existed.

The impropriety and total insufficiency of our methods of criminal prosecutions were very strongly shown by this trial. One member of the jury could barely write his name, and not more than one or two of them were in the lowest sense of the term educated; no record of the testimony was kept by the court, and none, except in the very beginning, by the jury, who must therefore have been guided chiefly by impressions, lawyers’ speeches or newspaper records; the feeling amongst the populace, with whom the jurymen freely mingled, was so bitter that one of the experts was barred out of his lodgings at ten o’clock at night, openly because he was for the defence of Mrs. Wharton; the newspaper which circulated most largely in the place misrepresented the testimony, and devoted its columns to scurrilous attacks upon the integrity and professional ability of the medical witnesses for the defence. Yet under these influences, mazed and confused by the subtleties and partial statements of the lawyers, these twelve honest but ignorant men were called upon to decide between physicians offering precisely opposite opinions. It is well when this so-called administration of justice ends as a monstrous farce and not as a tragedy.

The conduct of the Wharton-Van Ness trial would have been far different if the expert testimony had been what it ought to have been. If the excretions of Mr. Van Ness had been put in the hands of a properly-qualified chemist, by finding the metal antimony or by proving its absence he would at once have settled the case. As it is, there is no proper evidence of the guilt of Mrs. Wharton. The probabilities are in favor of her innocence, because the symptoms were certainly widely divergent from those induced by poison, if not, as I believe, absolutely incompatible with poisoning. The medical gentlemen who attended Mr. Van Ness, by destroying all the evidence, have made a just conviction and an absolute proving of innocence equally impossible.

If it were necessary, further illustrations of the deficiencies of our criminal processes could be detailed. Some little time since, upon the chemical evidence of Professor Aiken, a poor colored woman was hung in Anne Arundel county, Maryland. She died protesting her innocence, and the general impression appears to be now that she did not commit the crime. A prominent member of the Maryland Bar told me recently of a case tried in that State, in which the accused, as he stated, certainly did kill the deceased with arsenic, yet in which, by showing the insufficiency of Professor Aiken’s analysis of the stomach, he obtained the acquittal of the prisoner.

It cannot be stated too strongly that the trouble is not in the science of toxicology, nor in the real students of it. So far as mineral poisons are concerned, any qualified expert will determine the question of poisoning with the unwavering step of a mathematical demonstration.

The legal recognition of the true character and position of the expert, and of certain principles of medical jurisprudence, would probably improve the present status, but it is doubtful whether some other method of reform may not be more available. Professor Henry Hartshorne, at the last meeting of the American Medical Association, suggested that the court should appoint in poisoning cases a commission to collect the scientific testimony and make report on the same. This seems at first sight practicable, but suppose the court had appointed, as is not at all improbable they would have done, Professors Aiken and Chew and Dr. Williams as the commission in Mrs. Wharton’s case? The result would certainly have been an unjust conviction.

In Spain and some other countries of Europe the custom is to refer the case to the local medical society. If the opinion afterward given is unanimous, the court is bound by it; if any member object to the opinion, the case is referred to the medical society of the province; if the disagreement continue, the matter is brought before the chief society of the capital. Evidently, this plan would not work well here. In Prussia it was formerly, and may still be, the custom for an expert holding a fixed appointment under the government to investigate the case, and to send his report to the Royal Medical College of Prussia. A standing committee of this body, after investigating the matter, sent the original report, with their comments, to the ministry, by whom it was referred to a permanent commission of experts. The report of the latter body, with all the other papers, was finally sent to the criminal court. This method seems complicated, but it resulted in giving to Prussia the best corps of experts the world has ever seen, as well as the most eminent individual medical jurists.

It is not, however, the object of the present paper to urge any especial method of reform, but to call attention to the need of it, and to show that the present evils do not grow out of the imperfections of medical jurisprudence, but out of the methods of our criminal procedures. Certainly, the matter needs investigation, and it is hardly possible but that some practicable means of relief could be devised by the deliberations of a mixed commission of lawyers and medical jurists of eminence.

Still awake? Read more here.

The Deadline Approaches

A reminder: until May 1, we’re accepting applications for a Writer-in-Residence at the Standard, East Village, in downtown Manhattan—you’ll get a room at the hotel for three weeks’ uninterrupted work. The residency will last the first three weeks in July; applicants must have a book under contract. The applications will be judged by the editors of The Paris Review and Standard Culture. You can find all the details here. Bonne chance!

The Aulds Have It

Jolie/Laide is a series that seeks the beautiful and the ugly in unexpected places.

Angela Lansbury in Terry Richardson’s iconic cover shot for The Gentlewoman.

Continue to present yourself as a woman of loveliness and dignity, a woman who feels good and knows she’s looking her best. —Angela Lansbury, The Gentlewoman, Autumn/Winter 2012

When I was a little girl, I had no reason not to follow my parents’ edict to respect my elders, especially when it came to my female elders. My mother was stunning. I’d watch, mesmerized, while she applied her makeup, spritzed her Chloe perfume, and put on her latest Valentino or Ungaro ensemble before an evening out with my father. I thought her mother, my grandmother, was the epitome of elegance in her Upper East Side tweed uniform. Flipping through my mother’s latest issue of Vogue, I saw a photo of Sophia Loren in glasses. “This woman looks like mom when she wears her glasses,” I announced. “I do not look like Sophia Loren, but I thank you for the compliment,” my mom said.

At the time—the eighties—Sophia was in her early fifties. The mask of fright she now wears, courtesy of an aggressive plastic surgery regimen, had not yet been donned. During that period, I also saw pictures of Audrey Hepburn, who was ten years Loren’s senior, and I thought she, too, was beautiful. Of plastic surgery, she once said, “I think it’s a marvelous thing, done in small doses, very expertly, so that no one notices.”

In those photos, Hepburn and Loren seemed to play the role of the approachable patrician; to “grow old gracefully,” a phrase that Oil of Olay would soon borrow for an ad campaign in which women who appeared to be in their late thirties declared they did not intend to do something so silly, but would, instead, “fight it”—growing old—every step of the way. Maybe that was when the fight against aging began in earnest; when we gave beauty an expiration date that would encroach further into youth over the ensuing decades.

Actresses of a “certain age”—turning forty was career suicide—were boxed out of the box office. At first, they disappeared from the screen entirely. When they returned it was to play the mothers of women old enough to be their younger sisters, and they did so significantly altered.

Sadly, the precedent provided by Loren and Hepburn was supplanted by Botox and lip plumpers, people injecting bum fat into their other cheeks. This new breed of mature woman looked alien, generic, one shiny creature indistinguishable from the next; at their worst, they resembled leonine gargoyles.

These women were supposed to show their younger counterparts how to behave, how to age with dignity and, yes, grace. Instead, they had let us down, and, even worse, were trying to look like the people they should have been setting examples for. The result: twenty-something women hooked on Restalyne and the rise of the cougar, sex-crazed women pursuing men young enough to be their sons.

On the other end of the spectrum, just as depressing, we’ve seen an uptick in the eccentric grandmother, the kooky matron. Today’s Demi Moore is tomorrow’s Baby Jane Hudson; twenty-nine years after playing Mrs. Robinson, Anne Bancroft took on the role of the archetypal loony old bat, Miss Havisham. The eternally jilted bride, I’ve noticed, has been cast younger and younger, and she’s played these days with a subtle, disquieting hint of licentiousness; I give you Charlotte Rampling, Gillian Anderson, and Helena Bonham Carter.

Over all of these women there looms a shadow of decadence: the decay of the body, the corruption of morality, the disintegration of reason. With age, they seem to suggest, come vanity and folly.

I’d begun to despair of ever having role models. And then Penny Martin—the editor-in-chief of The Gentlewoman, that “fabulous biannual magazine for modern women of style and purpose”—put the timeless, tasteful, and outspoken eighty-six-year-old Dame Angela Lansbury on the cover of the 2012 Autumn/Winter issue. Yes, the most famous portrayer of Sweeney Todd’s Mrs. Lovett—something of a cougar herself, and most certainly unhinged—was the cover girl of the publication for the thinking chic woman. “She was on my list when I went for the job interview and I feel it was important for a number of reasons,” Martin said of the decision. “To have a woman of her age on the cover of a magazine when it’s not an ‘Age Issue,’ it clearly spoke to a lot of people.” Lansbury did not look like an alien, or a withering hag. She was every inch the dignified octogenarian: she was unfussy and glamorous. Smartly clad in a (peachy rose-colored) silk shirt with a strand of (red) beads around her neck, and a streak of lipstick to match, there Dame Angela was in black and white; her signature (since 1966) “boyish golden crop” gone silver-white, she wore the trademark glasses of her photographer, Terry Richardson—he of the creepy predilection for young models—of all people. Hers is a stylishness based in pragmatism—she shops, we’re told, at Gap and Uniqlo for her daily uniform of “shirts and trousers.”

Although her presence on that cover could be taken as an ironic statement, the irony was not at the expense of its subject. She speaks openly about how her looks didn’t measure up to the movie industry’s standard of beauty—“All I could do as an actress was give the illusion of being a much more beautiful woman than I am … I don’t think my appearance was ever in any way responsible for my success as an actress.” She is equally, if not more, candid on the subject of sex as she challenges the “sexual invisibility” associated with women over fifty. Lansbury’s theory is that instead of being preyed upon or ensnared by older women, younger men are naturally drawn to the more senior option.

During the years when younger women are hoping to find the man who’s going to marry them and give them a family, they’re unsure of their own sexuality and their ability to attract and to hold a man … The hopes and expectations they bring become a burden, and men feel the weight of it. Whereas I think women who have settled those questions in their own minds don’t present such an enigma to a young man. Because they are what they are.

Angela is what she is, no pretense or vanity. That’s why Martin’s dedicating an issue of the magazine to the actress had an impact. It’s not just that this women is old; she’s real—not an airbrushed character.

Soon after, Jackie Onassis’s sister—Lee Radziwill, age seventy-nine, a princess of Poland, Andy Warhol’s best friend, Truman Capote’s swan—appeared on the front of the February 2013 issue of T: The New York Times Style Magazine. It marked a cultural transition away from one Kennedy-related trope—Grey Gardens—to another—the regal dowager.

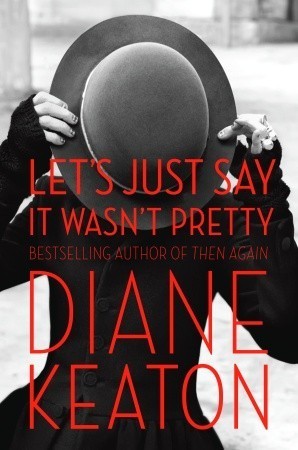

From there, a crop of memoirs followed: from Diane Keaton and Angelica Huston, from Patti Smith, from the fashion legend Grace Coddington. Joan Rivers and Elaine Stritch are the subjects of new documentaries. Last year, at eighty, Cicely Tyson won a Tony Award for her turn as Carrie Watts in The Trip to Bountiful, while the relatively unknown eighty-four-year-old actress June Squibb was nominated for an Oscar. Lena Dunham cast Squibb in Girls along with Louise Lasser, who, up until that turn, was best known for her roles in the Woody Allen films of the late sixties and early seventies.

Biddies are trending, that much is clear. And this particular strain has a few defining traits: She is not a conventional beauty, and has, despite that fact—and sometimes because of it—carved out a successful career in the limelight. She has not been overzealous in her visit to the plastic surgeon (except Joan, whose aggressive program has become integral to her schtick) and she hasn’t attempted to hide her age from her audience. Like Lansbury, she is what she is and works hard, “every day,” as Brubach wrote of the Dame.

Keaton, for one, continues to sign on for film roles and, next week, has a second book out. In Let’s Just Say It Wasn’t Pretty, the actress challenges her industry’s cookie-cutter definition of and obsession with beauty, freely cops to her own related insecurities, and, ultimately, celebrates her flaws (and defends her love of turtlenecks):

Keaton, for one, continues to sign on for film roles and, next week, has a second book out. In Let’s Just Say It Wasn’t Pretty, the actress challenges her industry’s cookie-cutter definition of and obsession with beauty, freely cops to her own related insecurities, and, ultimately, celebrates her flaws (and defends her love of turtlenecks):

I tell myself I’m free to do whatever the hell I want with my body. Why not? I may be a caricature of my former self; I’m still wearing wide-belted plaid coats, horn-rimmed glasses, and turtlenecks in the summertime. So what? Nobody cares but me. I don’t see anything wrong with face-lifts or Botox or fillers. They just erase the hidden battle scars. I intend to wear mine, sort of.

Keaton speaks for “a group of sixty-five and older show business folk,” but she also identifies with a larger contingent. “I’m a post-World War II demographic,” she writes. “I’m one of the seventy-six million American children born between 1946 and 1964.” That’s quite a large market share, even if we’re only talking about the women in it. Based on today’s extended average human life expectancy, at sixty-eight, even the oldest of boomers have got a lot of livin’ to do.

Two decades ahead of Keaton, Lansbury proves there’s life in the old girl yet. She likes to remind us that older women are sexually visible; the fact that she’s still appearing on the stage and screen reminds us that they are professionally visible, too. Women over sixty-five have acquired a pop cultural relevance they haven’t always had, because they’ve been able to contribute more in the workplace and take on higher profile jobs. They’re also living longer, which means they can continue to accomplish more over an extended period of time; sometimes, they don’t have a choice. For many, retirement is a luxury—or else, a resignation to mortality.

Look at the woman who put a controversially pretty face on the feminist movement. At eighty, most of what Gloria Steinem does, according to New York Times columnist Gail Collins, who interviewed the activist right before her birthday last month, “involves moving the movement forward. Speech to meeting to panel to fund-raiser.” As Collins points out, “very few women have aged as publicly” as Steinem has. Most of those who have don’t choose to do so without a nip or tuck. All Gloria’s done is dye her hair, which, Nora Ephron posited in her 2005 essay “On Maintenance,” is not only “the most powerful weapon older women have against youth culture,” but also “actually succeeds at stopping the clock … makes women far more open to drastic procedures (like face-lifts).”

Coincidentally, when Ephron put that theory forward, she used Gloria Steinem’s now famous response to turning forty—“This is what forty looks like”—as a segue. Steinem, who has not succumbed to “drastic procedures,” has now become a poster woman for what eighty looks like. And, as Collins writes, “Actually, she doesn’t look terrible at all. She looks great. She looks exactly the way you would want to imagine Gloria Steinem looking at 80.”

I think she looks great, too, and I’m not alone. Steinem looks exactly the way I’d want to imagine Audrey Hepburn to look at eighty-five, which she would be on May 4, had she lived; she looks the way I’d want to imagine Diane Keaton to look when she’s in her eighties, and she looks the way I already know Angela Lansbury looks at eighty-eight. Steinem looks like a vibrant, confident—and stylish—elder stateswoman, 2014 edition.

For whatever moment they’re enjoying in the cultural spotlight, I’m thankful, because they’re active and actively aging; they’re putting the cougars and Havishams to shame. They provide women younger than they are with something to look forward to—and something to live up to.

Charlotte Druckman is a journalist and editor whose food writing has appeared in the Wall Street Journal, T: The New York Times Style Magazine, and Bon Appetit. She is also the author of Skirt Steak: Women Chefs on Standing the Heat & Staying in the Kitchen.

Trouble-Proof

Gustave Caillebotte, Rooftops in the Snow, 1878

Is there a song about city life more evocative than “Up on the Roof,” the Drifters’ 1963 hit? In 1980, The Illustrated History of Rock and Roll said, “From the internal rhyme of ‘stairs’ and ‘cares’ to the image of ascending from the street to the stars by way of an apartment staircase, it’s first-rate, sophisticated writing.” All true, but the appeal is emotional, visceral, too.

Many years ago, I used to occasionally babysit for a little boy who sported a diaper until an advanced age. When he had to go to the bathroom, he would scream, “PRIVACY!” and everyone would have to vacate whatever room he was in.

That was weird, in retrospect. But I sort of envy him it—not the diaper, but the ability to magically invoke solitude. Maybe I am extra aware of it because I am currently visiting with my parents, and they have a tendency to shout to each other between floors, and I have a tendency to regress, and suddenly, just as when I was a teenager, all I want is to have some space of my own, where I can read, and think, in private.

Reading somewhere private and tucked away is one of life’s greatest and rarest pleasures. Neither “Up on the Roof” nor “Under the Boardwalk” is, exactly, about reading. But the Drifters were urbanites, and so were the composers, Carole King and Gerry Goffin, and they understood the need for solitude—anywhere you can find it—and the unparalleled delights of escaping notice. Half the point of the roof, and the boardwalk, after all, is that others are right nearby—“people walking above,” “right smack dab in the center of town”—but they don’t know you’re there.

The best spot I ever found was in a closet at my grandparents’ house, which was itself concealed behind a bookshelf. I made a nest on top of a chest of drawers, and no one knew where I was for hours at a time. Also good, and also on my grandparents’ property, was the old canvas parachute we rigged up in the walnut tree in the backyard. Back home, I had to take drastic measures—crawling out, Drifters-style, onto the roof, or sometimes secreting myself in a cupboard in the attic. I remember thinking there was no place secret enough in the world.

The other day, I experienced the kind of primal and wholly irrational rage I have not felt in years. I arrived at the library and made my way into the further reaches of the highest stack, to a tiny carrel tucked between Art and Architecture. This is my spot: it is where I work every day, and I have never known anyone to so much as walk by. And yet, on this day, I found the desk lamp lit and, in its glow, the silver hair of an elderly man. How dare he! I thought. And then he looked up in irritation, because, after all, I was disturbing his solitude.

There are many benefits to being an autonomous grown-up. But being able to hide oneself is not one of them. We are too big, for starters, and too accountable to other people. We can’t scream “PRIVACY!” and have people bend to our will. That little boy, incidentally, is now premed at an Ivy League university. I wonder whether the world is still his bathroom, or whether, as for the rest of us, he now has to find privacy wherever he can.

Solitude & Company, Part 4

Photo: Festival Internacional de Cine en Guadalajara, 2009

In our Summer 2003 issue, The Paris Review published Silvana Paternostro’s oral biography of Gabriel García Márquez, which she has recently expanded into a book. In celebration of García Márquez’s life, we’re delighted to present the piece online for the first time—this is the fourth of five excerpts. Read the complete text here.

MARÍA LUISA ELÍO: I got a call from Spain about 4 a.m. that Gabo had been awarded the Nobel Prize. I put on a pair of pants and a sweater and left for his house, and there was Mercedes with all the phones off the hook. There was a big sign on the door of their house that said Congratulations. He had these big eyes wide open as if he were hallucinating.

JUANCHO JINETE: Obregon went to visit Gabito in Mexico. The address he had for the house was where rich people live, like Mexican soap stars. The day he went to visit was the day Gabo got the Nobel Prize. So when he got to the address, there were flowers everywhere, and he thought, Oh my! He’s dead!

HECTOR ROJAS HERAZO: When the Nobel came around, Colombia went crazy. Everybody was talking about Gabito. That must’ve changed him. The moment comes that he has to be faithful to the success he has achieved.

NEREO LÓPEZ: We formed a delegation with the director of Colcultura in order to accompany the Nobel Laureate to Sweden. Singers like La Negra Grande and Toto, la Momposina; folk groups, a group from Barranquilla and a group from the Valle Province. There were 150 of us. They had told the vallenato musicians that Swedish girls went ape over Latin American men, so the guys went there ready, willing, and able to screw all the Swedish girls that crossed their paths. On the third day we said, “Hey, we haven’t gotten any calls yet. ” Seeing that the mountain wasn’t coming to Mohammed, we took Mohammed to the mountain, and we went to a striptease joint. What a joke! They were a bunch of nuns, all covered up, flashing an occasional breast. We were lodged onboard a comfortable but inexpensive ship while the guests of honor were put up in a first-class hotel. It was so cold, one of our crowd wanted to leave. He said: “The thing is that I have a problem and I need your help. When I go outside to take a leak I don’t find my penis.” He wondered how on earth he was going to go back to his country, where he had three women to respond to. When I asked him where he went to release himself, he told me that he went on deck. I told him that with four or five inches of snow, it was only natural for his penis to hide. I told him, “For goodness sake, man, what’s the matter with you? There is a bathroom downstairs.” At a restaurant, the woman behind the counter let out a shriek because Escalona was going to drink the vinaigrette, thinking it was some sort of fruit juice: “You’re drinking the salad dressing!” Aracataca had arrived in Stockholm!

GUILLERMO ANGULO: I think Gabo gets annoyed when someone tells him that he’s a great writer. That’s very obvious, and he knows it and no one has to tell him.

ENRIQUE SCOPELL: The Nobel Prize did great damage to Colombian literature. Because now everyone wants to be García Márquez. They say, “Oh no. If García Márquez didn’t say it then it’s not Colombian literature. ” He casts a very big shadow. Like a bonga tree’s.

RAMON ILLÁN BACCA: Critics and journalists worship him. They were a horrific presence upon all of us who were trying to write. But people always are very interested in great authors. What has not been written about Thomas Mann?

EDMUNDO PAZ SOLDÁN: The world of García Márquez has always seemed strange to me. I’ve been able to enjoy it, but from afar. I never considered him a father, more like an uncle— I could visit him but I would want to leave the next day. As a reader, I admire his writing. But as a writer, I have to say the hell with it. It’s not my thing.

ALBERTO FUGUET: To read García Márquez at a certain age can be very harmful, and I would forbid it. It can spoil you forever. García Márquez is a software that you install and then can’t get rid of.

MARÍA LUISA ELÍO: Have you been out on the streets with him? The girls throw themselves at him. It must be annoying. It’s a phenomenon that didn’t happen with Octavio Paz. I’ve been out with Octavio not once but a thousand times, and I haven’t seen people throwing themselves at him to kiss him or ask him whether or not he is Octavio Paz. García Márquez’s phenomenon is very special. He has great charisma.

ELISEO ALBERTO: I was walking with Gabo in Cartagena when we heard someone crying out his name: “Gabo, Gabo, Gabo.” We turned around and saw this young couple. The young woman was waving at him to come over. When we got there, she held Gabo by the arm and said to him, “Gabo, please help me. He doesn’t believe me. Gabo, will you please tell him that I love him.”

ODERAY GAME: When I lived in Madrid he would call me up and say, “I’m coming to Madrid for three days. I know you have friends in the press so do not tell them I’m coming.” After three anonymous days he would tell me, “Hey, I can’t stand being locked up. Let’s go out to a bookstore and see if somebody will ask me to autograph a book.”

JAIME GARCÍA MÁRQUEZ: When he comes to Colombia they don’t let him rest. A few years ago, we were both in our pajamas talking away, and there is the president, who wants to say hello.

Silvana Paternostro is a journalist who has written extensively on Cuba and Central and South America. She is the author of In the Land of God and Man: Confronting Our Sexual Culture and My Colombian War: A Journey Through the Country I Left Behind.

Twenty-Four-Hour Bookstore, and Other News

Beijing’s new twenty-four-hour bookstore.

Fact: in 1934, H. G. Wells interviewed Stalin.

Professor Richard H. Hoggart has died, at ninety-five. In 1960, Hoggart helped to end British censorship of Lady Chatterley’s Lover; he is “widely credited as the most persuasive in convincing a jury of nine men and three women that Lawrence’s graphic descriptions of sex between Lady Constance Chatterley and her husband’s groundskeeper, Oliver Mellors, were not obscene.”

Beijing now has a twenty-four-hour bookstore. It has nightly promotional offers and air-conditioning. “We want to create an intellectual environment for book lovers,” the store’s manager said. But lest you think it sounds like paradise: “We mainly sell social science books.”

The critic Franco Moretti “pursues literary research of a digital and quantitative nature”; in other words, he handles books as if they’re mountains of data. “I’m interested in the survival of genres, of texts, of forms. I’m a formalist. I think that should be the basis of literary analysis because, I suspect, that is also the basis of readers’ choices, although readers may not be aware of that. They don’t seem to choose a story. They choose a story told in a certain way, with a certain style and sense of events.”

For Mary Gaitskill, Let’s Talk About Love, Carl Wilson’s excellent book about Céline Dion, becomes a meditation on our preoccupation with cool: our ferocious disdain for Dion suggests we live in “a world of illusory shared experiences, ready-made identities, manipulation, and masks so dense and omnipresent that in this world, an actual human face is ludicrous or ‘crazy’; a world in which authenticity is jealously held sacrosanct and yet is often unwelcome or simply unrecognizable when it appears.”

April 23, 2014

Down to the Wireless

Mike Licht, Women of Wi-Fi, after Caillebotte. Image via Flickr

Someone in my building—or maybe two different people, I don’t know—rejoices in cruel, taunting names for his wireless networks: “MineNotYours” and “NoFreeLunch.” “I’m just going to go out on a limb here,” my old boyfriend once said, “and speculate that this person is an asshole.”

But is he? Riding in the elevator or passing neighbors in the hall, I often wonder who it might be—the retired nurse upstairs? The mild-mannered gentleman with the rescue dogs? The 103-year-old who sits with her nurse in the lobby? Does someone have a small, secret life as a righteous, anonymous enforcer?

A few are more transparent. “Miguel21” is not hard to guess; “AngieandTommyWirelss” too. I’m assuming “Yankees” belongs to the guy who’s always duded up in Bombers regalia. And presumably, anyone who cared could guess that “PymsCup” was mine.

Others have a whiff of intrigue. Who is “StinkyTofu”? Wherefore “ChouChou”? And is “CaliforniaDreamin” really so unhappy living here in New York? I hope not.

Such is city living: anonymity and proximity and small, petty mysteries and the occasional reminder of another’s tastes and likes and feelings. It is half misconceptions, of course. Back when I lived in Greenpoint, we just assumed that the hulking retired paratrooper with the penchant for Final Fantasy had the network called “Bonecrusher.” We referred to him this way as a matter of course, and without mockery. We had lived there for a year before we learned that, in fact, he was “MondayImInLove”—and, incidentally, that he loved The Cure.

This is not a decision one ponders much—at least, I didn’t. You choose it in a moment, try to think of something you’ll remember, perhaps. Some are happy to live with a string of numbers. And yet it is how you are known—or not known—by many of those physically closest. Or perhaps it takes on a life of its own. I know “NoFreeLunch” and “MineNotYours” is unnecessarily confrontational, unpleasant, even. I mean, we all have locks on our networks—no need to belabor the point, or engage in such gratuitous chest-beating. And yet, there is something I like about it. Every time I log on, there it is: an assertion of personality—that which is, or could be, or maybe only exists in this small, insignificant domain.

Vote for the Daily (or Else)

A still from Lyndon Johnson’s notorious “Daisy” attack ad, 1964.

You may not have known it, but The Paris Review is nominated for two Webby Awards: one for best cultural blog and one for best “social content and marketing” in arts and culture. The winner of the People’s Voice award is determined by popular vote; the deadline is tomorrow at 11:59 p.m.

We’re honored by the nomination and we hope we can count on your support, but we’re not one to beg for votes—we’ve run a clean, dignified, gentlemanly campaign, free of pandering, slandering, smears, and slurs. But what has that gotten us? Four percent of the popular vote.

Fuck the high road: we’re going negative.

As of this writing, Mental Floss leads the cultural blog category with sixty-six percent of the vote. They are, on the face of it, an upstanding publication. Their site currently features a video of an amoeba eating human cells alive; ours, by contrast, features a video of our associate editor being smacked in the face with a bag of water.

But who are these people, really? Can you trust a periodical whose title puns on dental floss for your cultural blogging needs? What does it mean to be a Flosser? We asked our friends at Urban Dictionary, and the answer will astonish you:

There you have it. These people are, by their very definition, unreliable. So how did they come by a whopping sixty-six percent of the vote, you ask? Easy: in flagrant breach of Webby campaign decorum, they ran a constant advertisement on the bottom of their site. The Daily would never stoop to such lows; we never advertise.

But it gets worse—the Flossers’ gall knows no bounds. A very reliable source indicates that they’re gaming the system:

Your choice, then, is clear. To quote another levelheaded campaign ad: These are the stakes! To make a world in which all of God’s children can live, or to go into the dark. We must either love each other, or we must die.

Vote for The Paris Review on April 24. The stakes are too high for you to stay home.

Shakespeare, Heartthrob

Reclaiming the Bard for the common man.

Tom Hiddleston as Coriolanus in Josie Rourke’s production at Donmar Warehouse.

There was a time when attending a motion picture was not an occasion but an event. Most of the great movie houses that might remind us—the Roxy in Times Square, Fox Theater in San Francisco, the Loews Palace in DC—are long gone, but the Music Box remains. A local landmark on Chicago’s North Side, the theater still has its Austrian curtains, house organ, and even a hoary legend: the ghost of Whitey, the house manager who ran the theater from opening night in 1929 until Thanksgiving eve, 1977, when he lay down for a cat nap and passed away in the lobby.

The Music Box is an 800-seat theater, more than three times the size of Donmar Warehouse, another theater nearly four thousand miles away in London. What brought the two houses together was Shakespeare’s Coriolanus. A recent performance at the Donmar was beamed live, and later rerun, to cinemas all over the world as part of Britain’s National Theater Live series. It was the first time the Music Box telecasted a production that completely sold out.

In Shakespeare’s canon, Coriolanus sits somewhere between rarely remembered plays like Pericles and Two Gentlemen of Verona and stock selections like King Lear and Romeo and Juliet. A story of pride and political intrigue plucked from Plutarch’s Lives, the play is a little like an olive: a bitter fruit from Rome and something of an acquired taste. Its title character is one of Shakespeare’s great creations—for an accomplished actor, a role almost as inevitable as Iago or Macbeth. T.S. Eliot called the play “Shakespeare’s most assured artistic success;” he admired it so much he wrote two “Coriolan” poems with an eye toward an unfinished tetralogy.

It’s unlikely enough that an art-house movie theater would sell so many tickets to a telecast of Coriolanus—but I should add that this was a morning matinee in Chicago on a frigid Sunday in February. When I arrived, then, I wasn’t exactly worried about finding a place to sit—but I was bewildered to discover a packed house where I expected an acre of open seats.

I found mine between two accommodating couples in the second-to-last row. At the other end of the theater, Coriolanus was already blasting the Roman peasants—you dissentious rogues—for daring to demand grain. For Shakespeare’s surliest character, he was quite comely, and considerably younger than the middle-aged men who typically inhabit the role. He was also the reason why the audience looked suspiciously like a pep assembly.

If the name Tom Hiddleston means nothing to you, you probably missed last summer’s Thor: The Dark World, in which Hiddleston reprised his role as Loki, the mischief-making demigod who has become the most successful villain in the Marvel movie universe. You almost certainly didn’t vote him MTV’s “Sexiest Man in the World,” a title he won last December in a 77-percent landslide. That victory was thanks to the very girls (and not a few boys) who were drawn to the Music Box that morning: they came not for Shakespeare’s gilded syllables, but for Tom’s sportive grin.

It has transatlantic appeal. The host of the telecast noted that the theatrical run at Donmar had sold out in twenty-four hours and that she had been surrounded at an earlier performance by “school kids” who “stood up and screamed their appreciation.” Her experience echoed my own and that of the handful of others who were drawn to the Music Box not for an international sex symbol but for the Sweet Swan of Avon. The sell-out was such a surprise to some regulars that a staff member took the stage at intermission to assure them the $15 tickets had not been handed out gratis (and to inform the irregulars that an encore performance would be scheduled ASAP).

I hope the grumbling was minimal. The last thing Shakespeare needs is votaries standing akimbo-armed before the front doors of the theater. Yes, the plays constitute some of the sublimest heights of human expression, but Shakespeare could also tell a good fart joke. If we sometimes overlook that, it’s because an aspic of expectation has embalmed the Bard. We don’t simply watch the plays—we bear witness, with the result that contemporary audiences can sit through entire performances with the kind of rigid composure better suited to being held at gunpoint.

It wasn’t always that way. Pick up Shakespeare in America, an anthology published by the Library of America this month to coincide with the Bard’s four hundred and fiftieth birthday today. A miscellany of poems, speeches, letters, and assorted ephemera, the book reminds us that, in this new England of ours, the admiration and appropriation of Shakespeare have most often been unabashedly demotic.

One of the first selections is an epilogue to Coriolanus by the Revolutionary War poet Jonathan M. Sewall. It was offered as an addendum to the play when it was performed for (and, perhaps, by) war-weary American troops stationed in Portsmouth, New Hampshire. Though Coriolanus is often seen as a tale of liberty reaffirmed and loyalty rewarded, Sewall draws a parallel between the American troops’ rebellion and that of the title character:

A diff’rent scene has been display’d to night;

No martyr bleeding in his country’s right.

But a majestic Roman, great and good,

Driv’n by his country’s base ingratitude,

From parent, wife, and offspring, whelm’d in woe,

To ask protection from a haughty foe:

To arm for those he long in arms had brav’d,

And stab that nation he so oft had sav’d.

If Shakespeare was called upon to consecrate the divide between the colonies and home country, he could also split Americans. My favorite selection in Shakespeare in America is an anonymous pamphlet describing New York’s infamous Astor Place Riot of 1849. A simmering feud between the American actor Edwin Forrest and British thespian Charles Macready came to a head when Macready was invited to perform Macbeth at the tony Astor Place Opera House. Across town, Forrest decided to put up the same play in the popular confines of the Broadway Theater. The dueling performances became a contest—who were the rightful heirs of Shakespeare’s legacy, the aristocrats or the people? The people, for their part, tried to hasten a decision by breaking up Macready’s first performance: “Rotten eggs were thrown, pennies, and other missiles; and soon, still more outrageous demonstrations were made, and chairs were thrown from the upper part of the house so as to peril life.”

The performance, understandably, ended early. Yet Macready, undeterred and urged on by the city elite, agreed to a second performance three days later, one that would be guarded by hundreds of police and “several regiments” of the National Guard. They were needed: fifteen thousand people converged on the Opera House to disrupt the performance, and a battle ensued that saw over twenty people killed and scores more wounded.

Though history doesn’t tell of a similar contest on the other side of the pond, Shakespeare’s plays there were hardly subdued events. The Globe itself was never so silent unless the theater had emptied, and patrons had no qualms about delivering parting shots to an especially poor performance. Like contemporary audiences for a Thor movie, they had paid money for diversion and delight. Hamlet—even Hamlet!—was entertainment before it was art. Indeed, it survived as art only because it first excelled as entertainment. The unruly devotion of Elizabethan audiences preserved the plays for us, and the revelry of the uninitiated—with its laughter, sighs, and shrieks of delight—better approximates their humor than the gray liturgy of “art appreciation.”

It also recalls what it must have been like at the first night of a new play, an encounter with something unknown and extraordinary. At the encore telecast—I went, the Donmar production is superb—I bumped into a friend. She knew little of Coriolanus. She simply trusted the playwright and admired the leading man. They had entertained her before; it seemed safe to conclude they would do so again.

We sat together in the oblong theater, under the cobalt colored ceiling where tiny lights twinkle to indicate the stars. I said nothing of what was to come, from the hugger-mugger over hungry bellies to war-by-other-means to, at last, the incarnadine conclusion. I wanted that experience of Shakespeare, if only vicarious, of something entirely unexpected. So we watched, and when the stage fell dark and the players assembled for a bow, we did what seemed natural: we cheered.

John Paul Rollert is a writer in Chicago. His work has appeared in The Los Angeles Review of Books, Boston Review, and The New York Times.

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers