The Paris Review's Blog, page 715

April 17, 2014

Frozen Books

Wet Books, Richard Cubitt

Someone has posted the following to Reddit:

My roommate gets distracted sometimes, and she misplaced her book in the freezer. I’m not making this up.

The pages are warped from moisture and most of them are frozen solid in a block.

How can we save the book?

Thanks!

Cue the Fahrenheit 451 jokes—lots of them. But there were also plenty of practical tips to help the poster with his or her wacky dilemma. These include (but are not limited to) blotting the pages with paper towels and/or rice; allowing the book to dry in a cool room so as to slow melting; rubbing the paper with vinegar to prevent mildew; and, if all else fails and the poster deems the book worth it, investing in a vacuum pump and creating an at-home distiller.

As one knowledgeable person explained,

This is how books are salvaged from flooding on a commercial scale. They are frozen in the short run (with industrial freezers, if needs be, such as if a pipe breaks in a library), and stuffed into freeze driers which operate on a vacuum principle: the water sublimes, going straight from solid to vapor, while the book is still frozen, preventing any significant microbial growth if done correctly.

I can’t pretend to have ever forgotten a book in the freezer, but time was, I often left books out overnight in my family’s yard, and found them warped and damp with dew or rain. Plenty of them are warped to this day, but a great aid in such cases was the old book press my dad picked up at a tag sale when I was about twelve. These devices—ours was made of wood and had a black metal crank—are used by those who deal with rare books, but believe me, they work just as well (if not better) with the paperback copy of The Wolves of Willoughby Chase you picked up at the local library sale.

I have nothing against the occasional e-book. And I certainly understand the beauty and dignity of an exquisite edition, and the pleasure of filling your shelves with volumes in pristine condition. But personally—because I am hard on objects, and I lug reading material wherever I go, and, yesterday, I discovered that a Clinique Chubby Stick had come uncapped in my tote and stained everything with “Pudgy Peony”—I love physical volumes for their sheer durability. I like that a book can live through coffee spills and tears (both kinds) and ballpoint pens and, if necessary, the occasional smashed Cadbury Creme Egg, forgotten at the bottom of one’s bag.

I don’t think I’d go so far as the poster who suggested, “You could get some used $.50 books and try a few different methods while keeping the important book frozen.” But I like that the possibility exists. As long as books survive in paper and ink, it will be partly because they can also be just this side of disposable—because some will be found, and end up, on a neighbor’s stoop, or at the local thrift store. Because some deserve to.

That said, if anyone knows how to extract moisturizing lip gloss from the pages of a library book, I would very much like to know.

Whan That Aprill, with His Shoures Soote…

The Merchant

Chaucer

The Clerk

The Cook

The Franklin

The Friar

The Knight

The Manciple

The Miller

The Monk (with dogs)

The Nun’s Priest

The Parson

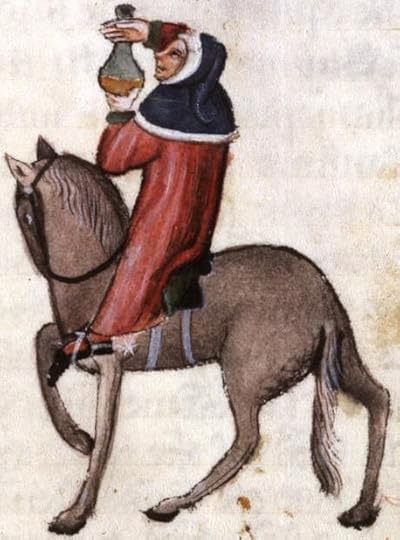

The Physician (Note: The Paris Review does not endorse the preparation of pharmaceuticals on horseback)

The Prioress

The Reeve

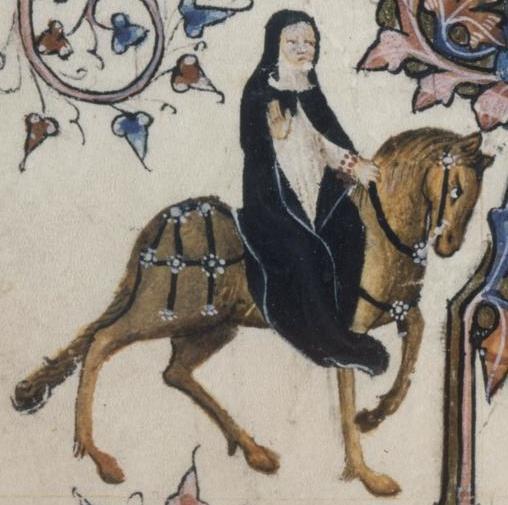

The Second Nun

The Shipman

The Squire

The Summoner

The Man of Law

The Wife of Bath

Chaucer scholars have generally settled on April 17, 1387, as the date his pilgrims departed for Canterbury—an historic and storied journey that has been, for more than six centuries, the bane of every student’s existence. A brief refresher: in the Canterbury Tales, twenty-nine pilgrims and a narrator vie to out-perorate one another on what must have been a tedious excursion to Saint Thomas Becket’s shrine, in, yes, Canterbury. Their prize? A free meal at a hotel restaurant.

Thus ensued several thousand lines of fart jokes, prurient asides, murderous Jews, and dubious blancmange, all of it now forever inscribed in the annals of literature.

The Ellesmere manuscript—written shortly after Chaucer’s death, in the early fifteenth century—is considered the definitive version of the Tales. It was produced on vellum, and it features involved, colorful illustrations of many of the pilgrims, pictured above. (None of their more scandalous exploits are depicted, alas, though it may not have been terribly edifying to see a drawing of a man being branded on the buttocks, anyway.)

I had an English teacher who made a shaky but memorable case for the Tales’ contemporary relevance. There were, he avowed, new chapters being written every day. All you had to do was book a long trip on a Greyhound bus or board a transcontinental flight, and you’d find strangers from all walks of life foisting their stories upon you, daring you to one-up them, whether you drew them out or not. Indeed, he said, these stories would hinge on the same crimes of passion that Chaucer’s pilgrims found so enthralling. It wasn’t as if any of us had tired of hearing about adultery. And so we should appreciate Chaucer, he said, because almost nothing in storytelling had changed in the years since the Tales.

Having encountered only this morning a garrulous and kind of lewd fellow-commuter, I can say: my teacher was totally right.

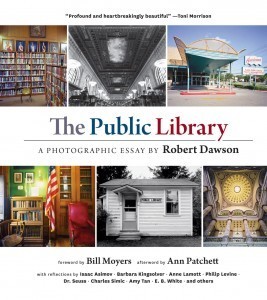

America’s Public Libraries

A photo essay for National Library Week.

There are approximately seventeen thousand public libraries in the United States. Since I began this project in 1994, I have photographed hundreds of libraries in forty-seven states.

I didn’t intend this project to last eighteen years. Many of the early libraries were photographed during longer journeys, when I had the time. The photography was usually connected to some other effort, such as when I taught workshops in Alaska in 1994 and Key West, Florida, in 1997. In 2000 my family and I took a long drive throughout the American West, occasionally photographing libraries along the way. In 2007 we traveled through Louisiana and parts of the South, again photographing a few. Every summer we have stayed in a little cabin in Vermont. I have always brought my camera along on each of those trips and gradually began to accumulate photographs from places other than my home in California. In the late 2000s I began to focus the project. I made specific library photo trips throughout Nevada and to Seattle, Salt Lake City, and Chicago. I began to realize that if I wanted to make this a national study, I had some more traveling to do.

In the summer of 2011 my son Walker and I spent eight weeks driving more than 11,000 miles to twenty-six states, photographing 189 libraries. We drove through the Southwest; Texas; the South, including the Mississippi Delta; up to Detroit; through the Rust Belt; and then over to Washington, D.C.; Philadelphia; and New England. Unfortunately, we were followed the entire way by a record-breaking heat wave. We called it our Library Road Trip and even got it funded through a Kickstarter effort. Filmmaker Nick Neumann joined us during part of the trip. I would write during the day and in the evening post a blog with my writing, our photos, and some of Walker and Nick’s film footage. I would change my large-format 4 x 5 film in the motel bathroom while Nick and Walker edited the video that they had shot that day. The next morning we would get up and do it all over again. This odyssey was exhausting but solidified the project and its goals.

In the summer of 2012 Walker accompanied me again as we spent four weeks driving more than 10,000 miles to fifteen states, photographing 110 libraries. As we drove we listened to two extraordinary books on tape—A People’s History of the United States by Howard Zinn and 1491 by Charles C. Mann. Both helped provide a context for what we were seeing. We traveled throughout the upper Midwest and witnessed some of the devastating drought in the farm belt. I again posted our travels on our blog, Library Road Trip. The 2012 trip filled in the parts of the map that I had not previously photographed and largely completed the project. However, at the end of the summer, I realized that I had photographed many libraries in poor communities but not many in wealthy places. So to add balance I photographed libraries in some of the country’s wealthiest communities near my home in the San Francisco Bay Area, including Mill Valley, Tiburon, and Portola Valley. Finally, in November 2012, I finished the project by photographing the heroic efforts of the Queens Public Library to provide services to the victims of Hurricane Sandy in the Rockaways in New York City.

In the summer of 2012 Walker accompanied me again as we spent four weeks driving more than 10,000 miles to fifteen states, photographing 110 libraries. As we drove we listened to two extraordinary books on tape—A People’s History of the United States by Howard Zinn and 1491 by Charles C. Mann. Both helped provide a context for what we were seeing. We traveled throughout the upper Midwest and witnessed some of the devastating drought in the farm belt. I again posted our travels on our blog, Library Road Trip. The 2012 trip filled in the parts of the map that I had not previously photographed and largely completed the project. However, at the end of the summer, I realized that I had photographed many libraries in poor communities but not many in wealthy places. So to add balance I photographed libraries in some of the country’s wealthiest communities near my home in the San Francisco Bay Area, including Mill Valley, Tiburon, and Portola Valley. Finally, in November 2012, I finished the project by photographing the heroic efforts of the Queens Public Library to provide services to the victims of Hurricane Sandy in the Rockaways in New York City.

Because I started the project shooting film, I continued to use film cameras throughout the project. The 4 x 5 Toyo field camera was ideal for recording the details of public libraries. I would also use a medium-format Mamiya 7 camera when I didn’t feel comfortable or have time to shoot with the larger-view camera. Over the last few years, I would also shoot recording shots with a small Canon G10 digital camera alongside the images made with my larger film cameras. Sometimes it was helpful to use this camera first, to locate the best angle or most interesting subjects in a library.

In his 2013 State of the Union address, President Barack Obama said that citizenship “only works when we accept certain obligations to one another and to future generations.” New York Times columnist Timothy Egan declared that the American “Great Experiment—the attempt to create a big, educated, multi-racial, multi-faith democracy that is not divided by oligarchical gaps between rich and poor—is still hanging in the balance.” Our national public library system goes a long way toward uniting these United States. A locally governed and tax-supported system that dispenses knowledge and information for everyone throughout the country at no cost to its patrons is an astonishing thing—a thread that weaves together our diverse and often fractious country. It is a shared commons of our ambitions, our dreams, our memories, our culture, and ourselves.

This project has allowed me a means of viewing much of our country over the last two decades. During that time libraries have changed dramatically, especially with the introduction of computers. However, since this nationwide odyssey, Walker and I have come to some similar conclusions: We Americans share more than what divides us. Most people work hard at their jobs and care about their families as well as their communities and the places they call home. And many care passionately about their libraries. Over the course of this project, I have been socked in the jaw by a crazed man in Braddock, Pennsylvania; screamed at by a homeless woman in Duluth, Minnesota; almost had my film confiscated on an Indian reservation in Colorado; and eyed suspiciously throughout the country. Despite all, this project has only reinforced my belief in the basic decency of most Americans. It has been a privilege to complete this study of our nation’s public libraries. And it has been a rare opportunity to see what we have in common through the lens of the local public library.

Robert Dawson’s photographs have been recognized by a fellowship from the National Endowment for the Arts and by a Dorothea Lange–Paul Taylor Prize. He has been an instructor of photography at San Jose State University since 1986 and at Stanford University since 1996.

A version of this essay appears as the introduction to The Public Library: A Photographic Essay . Copyright © 2014 Robert Dawson; reprinted with the permission of Princeton Architectural Press.

Hoarding Shakespeare, and Other News

James Orchard Halliwell-Phillipps lived like a tramp, but he had a huge collection of "Shakespearean rarities." Photo via the Guardian

On Vijay Seshadri, the poet who won this year’s Pulitzer: “The combination of epic sweep … and piercing, evocative detail is characteristic of the contribution Seshadri has made to the American canon.”

Next week at Lincoln Center, Rachel Kushner introduces Anna, a seventies documentary that will be familiar to readers of The Flamethrowers: it “centers on the titular pregnant, homeless sixteen-year-old whom the filmmakers discovered in Rome’s Piazza Navona.”

“In a small series of sheds in Sussex a nineteenth-century joker and eccentric hoarded the evidence that reconciles Shakespeare the playwright with Shakespeare the man.”

Heaven Is for Real “is based on the mega-bestseller by a pastor whose four-year-old had major surgery, after which he knew things he couldn’t possibly have known, and also claimed to have met Jesus … The intended audience appears to be people in medically induced comas who enjoy Nebraska-themed screensavers and who think that Michael Landon had a little too much ‘bad boy edge’ on Highway to Heaven.”

What’s this? Just the average story of a doctor-buccaneer who lived among the natives of Panama in the seventeenth century: “It took almost an hour for his shipmates to recognize him. Then one started backwards in shock. ‘Why! Here’s our doctor!’ the man cried, and a crowd gathered around him, trying to rub off the geometric paint that obscured his features. It was Lionel Wafer, the pirate surgeon.”

In 1951, when the sociologist C. Wright Mills published White Collar: The American Middle Classes, “an entire society was being white-collarized. Status and prestige, emotional games and office politics: These were leaking out of the workplace and into the world, coloring the entire way people interacted and organized their time and leisure. The frankly confrontational style of blue-collar work and industrial unions was disappearing.”

April 16, 2014

Kingsley Amis’s James Bond Novel

Happy birthday to Kingsley Amis, who would be ninety-two today. In his 1975 Art of Fiction interview, Amis says,

I think it’s very important to read widely and in a wide spectrum of merit and ambition on the part of the writer. And ever since, I’ve always been interested in these less respectable forms of writing—the adventure story, the thriller, science fiction, and so on—and this is why I’ve produced one or two examples myself. I read somewhere recently somebody saying, “When I want to read a book, I write one.” I think that’s very good. It puts its finger on it, because there are never enough books of the kind one likes: one adds to the stock for one’s own entertainment.

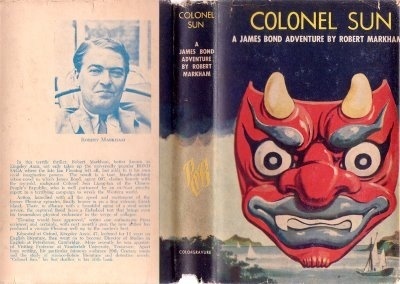

Amis was always a staunch defender of genre fiction—and one of the “examples” he speaks of having produced is Colonel Sun, a James Bond novel he published in 1968 under the pseudonym Robert Markham.

Amis had a predilection for Bond; a few years earlier, he’d published The James Bond Dossier, a critical analysis of Ian Fleming’s novels. When Fleming died, new writers were called upon to carry the torch of the franchise, and Amis was eager to try his hand. Aug Stone, writing at The Quietus, has the story of Amis’s unlikely entrée into the Bond canon. He was not a shoo-in. Anne Fleming, Ian’s widow, greeted Amis’s with a resounding harrumph:

“Amis will slip Lucky Jim into Bond’s clothing, we shall have a petit-bourgeois red-brick Bond, he will resent the authority of M., then the discipline of the Secret Service, and end as Philby Bond selling his country to SPECTRE,” she wrote in a review of Colonel Sun requested by the Sunday Telegraph.

And then there were there was the unsettling cover of Colonel Sun, whose first hardcover printing, pictured above looks like charmingly cut-rate Dali. Other editions weren’t much better, though they come closer to suggesting a thriller:

But anyone who feared that Amis would fuck up the franchise with some kind of measured, literary razzle-dazzle had it all wrong; he knew how to plot. As its flap copy makes clear, Colonel Sun was not about to traffic in high-minded nuance:

Lunch at Scott’s, a quiet game of golf, a routine social call on his chief M, convalescing in his Regency house in Berkshire – the life of secret agent James Bond has begun to fall into a pattern that threatens complacency … until the sunny afternoon when M is kidnapped and his house staff savagely murdered.

There’s no doubt in that “savagely murdered”: this is not lit’rit’chur. It has wanton violence, exotic locales, and a megalomaniacal villain from the East—from reddest Red China, even!—with a penchant for torture and wordplay. (Redundant?) As Stone writes,

Amis considered “Russia versus Britain too old-hat” … “Red China as villain is both new to Bond and obvious in the right kind of way. And Chinese master-villain would be fun…” His Colonel Sun Liang-tan of the Special Activities Committee, People’s Liberation Army, is an Anglophile with a madman’s sense of destiny. Fond of British culture, Sun speaks English with a bizarre mixture of regional pronunciations, treating his captives, M and later Bond, with the utmost civility. This is, of course, all a prelude to the monstrous torture scene that surpasses even that of Casino Royale, and this simply a preliminary exercise before 007 is to take up his role in Sun’s grand terrorist scheme.

Still, Amis had to indulge, on occasion, his literary pedigree. The torture scene finds Colonel Sun quoting, insidiously, the Marquis de Sade—though whether this is a comment on the torture or a part of it remains unknown. And Amis’s Bond has more dreams—Amis had recommended those to Fleming in the Dossier. “What about a few dreams?—known as the handy off-the-peg method of injecting significance into any form of fiction.”

Really, though, Colonel Sun only shies from thriller conventions when it comes to sex, which one would think Amis could’ve piled on. But in its absence he was only observing tradition:

Amis has pointed out that on average Bond seduces “one girl per trip,” and that this is hardly excessive … But there is surprisingly little sex in Colonel Sun, especially considering Kingsley’s reputation (Martin Amis wrote in Experience, “A promiscuous man, and a promiscuous man in the days when it took a lot of energy to be a promiscuous man, Kingsley was excited by his contiguousness to yet more promiscuity”).

Colonel Sun was, given the celebrity of its author and its tough position as the first post-Fleming Bond novel, surprisingly well received; the general consensus seemed to be that it was a ripping good yarn, worthy, perhaps, of Fleming himself. (Too bad his widow probably never read it.) The novel has yet to be adapted for film, true—but after more than twenty years out of print, it’s now available as an e-book. The next best thing.

The Zebra

Nathan Pyle has recently written an illustrated handbook for living in—or, perhaps even more crucially, visiting—New York. NYC (Basic Tips and Etiquette) contains such valuable tips as

Beware of the empty train car, it’s empty for a reason.

Bring cash to group dining events.

12% chance you have spotted a celebrity. 88% chance you have spotted someone who vaguely resembles a celebrity. 100% chance you are awkwardly staring at someone while you argue about it.

These will, I think we agree, apply to any good-sized city.

Yesterday, two of Pyle’s tips were very much on my mind. The weather had, abruptly, turned brutal: cold, with high winds and lashing rain. This weather! This weather! This weather! everyone chanted. Pyle is absolutely right in his assertion that “one $20 umbrella will outlast four $5 umbrellas.” I went for my hardiest number, which is, incidentally, patterned with cheerful zebras on a red ground.

The problem is, good, sturdy umbrellas do not give way easily on the street—they dominate all in their path. And I could not master mine. The same characteristics that allowed my Zebra to stand tough in gusts that blew out Beta umbrellas were those that made him a bully. So strong was he that I was helplessly pulled in his wake like a reject nanny out of Mary Poppins. I was protected, yes, but only from the elements. Everyone hated me, either out of jealousy or because under the force of my huge, heavy umbrella I was weaving all over the street.

Things did not improve when I reached the narrower streets of Chinatown, where the approaching Zebra sent packs of tourists scuttling and, when challenged by a group of children on the sidewalk, had to be held as far above the fray as my shaking, short arms could manage. You are always in someone’s way, Pyle reminds us, in an exhortation to speed. But I could not. My spinnaker would not allow it. In the space of a few blocks, I’d gone from sub-Poppins to Sorcerer’s Apprentice.

So I closed the umbrella, and I was wet, and cold, and uncomfortable. But I realized a part of me—a small part, granted—was relishing it. The weather had been beautiful for days—aggressively, gaudily beautiful. After the long winter, the warm sun and the flowering trees felt like a balm. Everyone beamed at each other and soaked up every ray we could find. But it was almost too much; just as in perverse moments one’s worst nature ruins a too-perfect day with a fight, the happiness felt unsustainable. Maybe it was something superstitious in me, but I was slightly relieved to have the beauty alleviated, even to know that blossoms were being knocked from the trees.

The Missing Borges

Seven years ago, a stolen first edition of Borges’s early poems was returned to Argentina’s National Library. But was it the right copy?

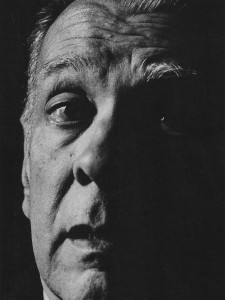

Jorge Luis Borges in 1963. Photo: Alicia D'Amico

The world of rare books and manuscripts is full of intrigues, betrayals, and frauds. Alberto Casares has lived in this world for decades; as the president of the Antiquarian Booksellers Association of Buenos Aires, he’s an expert on the subject. He’s got the physique du rôl: a gray, messy beard; a soft body; an intense and wary look.

A few months ago, Casares was offered a seventeenth-century original edition of Don Quixote for one million euros. He recognized it as a well-known forgery from the nineteenth century, worth no more than €200,000. The seller took it away, determined to find a more unsuspecting client, and Casares was left alone with the melancholy of having lost something that was never his to own.

What would some people give to own it? Casares told me, “Bibliographers are willing to commit crimes to follow their mad desire to own things.” He was thinking of a former client, Daniel Pastore, a collector of rare books and first editions, heir to a pharmaceutical fortune and owner of Imago Mundi, Buenos Aires’s most elegant antiquarian bookshop, which closed a few years ago after a succession of international scandals involving Pastore.

Casares was annoyed and fascinated by Pastore, who was eighteen the first time he walked into Casare’s bookshop. He was handsome, rich, likeable, and learned—a good client. But he was also pedantic; he claimed to know more about rare books than Casares. Sometimes he did. But not when it came to Jorge Luis Borges.

* * *

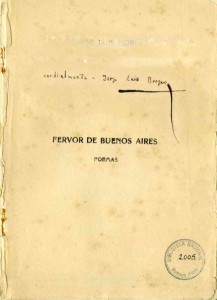

One morning in late 1999, Pastore brought in a copy of the first edition of Fervor de Buenos Aires, Borges’s first published book. For men like Casares and Pastore, it was a kind of grail—the most valuable first edition of Argentina’s greatest twentieth-century writer.

One morning in late 1999, Pastore brought in a copy of the first edition of Fervor de Buenos Aires, Borges’s first published book. For men like Casares and Pastore, it was a kind of grail—the most valuable first edition of Argentina’s greatest twentieth-century writer.

The first edition of Fervor was funded by Borges’s father when the author was twenty-three. “The book was actually printed in five days; the printing had to be rushed, because it was necessary for us to return to Europe,” Borges writes in his 1970 essay ”Autobiographical Notes.” “[It] was produced in a somewhat boyish spirit. No proofreading was done, no table of contents was provided, and the pages were unnumbered. My sister made a woodcut for the cover, and three hundred copies were printed … Most of them I just gave away.”

Borges had lived in Europe between 1914 and 1921, and the forty-six poems he gathered in Fervor de Buenos Aires reflect what he found upon returning to Argentina. “The city of his childhood had changed,” says Beatriz Sarlo, a leading expert on his works. “It had almost lost the most colorful marks of its criollo small town past … Borges returned, then, to a place he did not know.”

“Fervor de Buenos Aires foreshadows everything I would do afterward,” wrote Borges. Every self-respecting collector of his works owns a copy from that first edition. Few copies remain—only 150, according to Casares, with no more than fifteen in circulation. But Pastore had that copy in his hands. Could Casares confirm that it was a legitimate first edition?

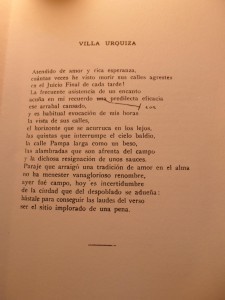

He identified it immediately—it was the Fervor de Buenos Aires from the Peña Collection, sold to the National Library a couple of months earlier by Juan Manuel Peña. Indeed, Casares knew this copy  very well; six years earlier, Peña had lent it to him to make a facsimile edition. It had no cover; a handwritten dedication by the author to the poet Nydia Lamarque; and, in the fifth line of the poem “Villa Urquiza,” a correction, also handwritten: the article una was crossed out, and in the right margin Borges had changed it to the preposition con. Borges used to correct his verses as he gave them away, especially in this edition, which had been published with mistakes because of the rush. (Many copies of the first edition show the same handwritten correction.)

very well; six years earlier, Peña had lent it to him to make a facsimile edition. It had no cover; a handwritten dedication by the author to the poet Nydia Lamarque; and, in the fifth line of the poem “Villa Urquiza,” a correction, also handwritten: the article una was crossed out, and in the right margin Borges had changed it to the preposition con. Borges used to correct his verses as he gave them away, especially in this edition, which had been published with mistakes because of the rush. (Many copies of the first edition show the same handwritten correction.)

“The edition is good,” said Casares. “It was stolen from the National Library. Who gave it to you?”

Pastore mentioned Guillermo Billinghurst, a “mediocre bookbinder,” according to Casares, who used to bring him Borges first editions of dubious origins—a client had left it with him for binding, he would claim every time, and did not return to pick it up.

“I’m going to report this robbery to the National Library,” Casares warned Pastore. “You do whatever you want.” He watched Pastore leave with the stolen book. But he remained “deeply convinced that [Pastore] was not going to buy it.”

Fifteen years later, Casares bitterly regrets his outburst of civic responsibility. What happened afterward taught him that, in Argentina, it’s better to keep your mouth shut.

* * *

Before he filed the report, Casares called Juan Manuel Peña to warn him that a book from his collection had been stolen from the library. Instead of thanking him, Peña begged him to hide it. The Library had not yet paid him for the books, which he had already delivered, and a scandal could ruin his chances of getting the money. Casares, determined to do the right thing, talked to Alejandro Vaccaro, the Borges specialist, who understood the seriousness of the matter and offered to go with him to explain it to the director of the National Library, Francisco Delich.

They got an audience, but, just like Peña, the director did not seem to welcome the news. First, Delich and a couple of library employees denied that the copy had been stolen—it was, they said, stuck in Portugal as part of a traveling exhibition about Borges. (Much later, a library employee confirmed that, for budgetary issues, the Argentine government took three years to repatriate that exhibition.) Also, the library had never properly catalogued the book before sending it off in the exhibition, which made it hard to confirm it was the same copy.

Exasperated, Casares demanded that the police be told, and that they raid Billinghurst’s apartment immediately to recover the book. But the employees only went as far as to initiate an internal inquiry.

* * *

Years passed. Billinghurst had already died of liver disease by the time the internal inquiry confirmed that the copy of Fervor had, in effect, disappeared. Casares was summoned to the Ministry of Education to confirm his theft report. The bureaucrat that took his statement warned him: “If you ratify this, it will get to the federal justice.”

And so it did. The officers at the federal court of Judge Jorge Ballestero were used to dealing with drugs and government corruption; they didn’t quite understand the gravity of the matter. After all, this was not a manuscript or a unique copy—it was a printed book, one of many. Even if it had Borges’s handwriting in it, what, really, was its importance? The library itself had another copy of the same edition.

Trafficking in cultural property, including rare books and manuscripts, is a six-billion-dollar-a-year industry, second only to arms and drugs, according to estimates often cited in international conferences. Interpol, which two decades ago opened an office to deal with this kind of crime, says that estimate is impossible to confirm. Most of the trafficking centers on London—its endpoint tends to be the United States, where there are enough people willing to pay hundreds of thousands of dollars, or even millions, for a rare book. According to Travis McDade, a professor at the University of Illinois Law School, owning a unique symbol of universal culture makes some people feel just as unique. “Never underestimate people’s necessity to be considered intelligent,” he says. Nobody knows how many valuable books have been stolen and bought in the black market, and every now and then a scandal breaks to prove our ignorance. In 2003, it was found that an employee at the Royal Library in Denmark had stolen, in the previous thirty years, more than three thousand unique books, among them manuscripts by Immanuel Kant, fifteenth-century atlases, and first editions of Martin Luther. The case only became public when, after the employee died, his widow tried to sell the collection to Christie’s. The value of these books and manuscripts lies not only in the fact that a millionaire might be willing to pay for them, but, as both buyers and traffickers understand, in their import as cultural artifacts.

When, four years after filing his report, Casares was called to give a statement about it, he was unable to make the Argentine court understand this.

* * *

The National Library of Argentina, Buenos Aires. Photo: Phillip Capper, via Flickr

No one seemed to care about the civic aspect of the matter, either. The National Library is as old as Argentina: it was created in 1810, together with the first national government, and its first director was Mariano Moreno, one of the greatest national heroes and the founder of the country’s first newspaper. The library was, at one point, something to be proud of, and Borges’s name is inextricably linked to its history; he was its director for eighteen years, between 1955 and 1973. By then, books were already disappearing from its shelves. When asked whether this was true, he replied, in typical fashion, “I can’t tell whether books are being stolen, because I’m blind.”

Deborah Yanover, the owner of Bueno Aires’s Librería Norte, told me that his father—the late Héctor Yanover, the bookshop’s founder and another former director of the library—often received offers of first editions and manuscripts, stolen from the library of which he was the director. According to Horacio Salas, another director, the library lost some two hundred thousand books in the last few decades.

Out of how many? No one knows. That’s right: no one knows how many books there are, or should be, in Argentina’s National Library. Horacio González, its current director, told me that the library “has approximately a million books and some four million other pieces (newspapers, music sheets, records, photographs, etc.). I don’t have exact numbers and at this point it is very difficult to have them.”

This problem is not exclusive to the library. State archives are woefully neglected. When a naval officer opened the door of a basement in the Navy building for me a few years ago, he found it had turned into a lake of wastewater in which boxes, papers, and rats floated. In 2001, an undersecretary at the Interior Ministry found, by chance, while he was moving offices, a very valuable file with classified documents from the last dictatorship (1976–1983). He called me: Maybe some of it would be useful for a book I was writing? I could take whatever I wanted. Only after I wrote about it for the newspaper was he forced to hand in the file to the office in charge of processing it.

* * *

In mid-2003, while the investigation languished in court, Pastore called Casares again, this time not to show him but to ask him for a copy of the first edition of Fervor de Buenos Aires. He was preparing a collection of Borges’s first editions and other treasures, for which he expected to get a record price: four million dollars. It would be auctioned at Bloomsbury Book Auctions, in London.

But Casares didn’t have an edition of Fervor, and he couldn’t get one from the collectors he called. Instead, at a reduced price, he sold Pastore one of the facsimiles he’d made ten years earlier from the stolen Fervor. Pastore also asked him to write the prologue for the auction catalog.

On October 28, 2003, almost a month before the auction, the catalog made it into the hands of Alejandro Vaccaro, the collector who’d accompanied Casares to file the report on the Fervor theft. Vaccaro found the description of the copy of Fervor included in the offer: it was an exact match of the copy stolen from the Library. There was the dedication to Nydia Lamarque and the correction on “Villa Urquiza.” The summary also mentioned that the copy had belonged to the Peña collection. There were no doubts: this was the stolen copy!

What Vaccaro didn’t understand was why Casares, who had reported the crime as soon as it had happened, had now turned into an accomplice.

He called a journalist from La Nación, and the following day everyone knew that a valuable book stolen from the National Library would be auctioned off in London for £22,000. It was an international scandal, an embarrassment for the country.

Pastore and the organizer of the auction, an Italian man called Massimo De Caro, claimed there was an error in the catalog. Casares explained that the catalog writer, a Bolivian named Molina, had had the facsimile before him as he wrote: hence the mistake. The book offered in the auction was not the one from the Peña collection, they said.

No one believed them. They had to remove the book from the auction, which became a failure. Pastore and De Caro offered to take the book to the library so that its new director, Horacio Salas, could confirm it was not the stolen copy. Salas accepted—but before he received them, he called Judge Ballestero, who was in charge of the dormant case, and who in turn alerted Interpol. When Pastore and De Caro walked into the director’s office, they found the police, who confiscated the book and put it under custody of the court.

* * *

Casares, now suspected of having taken part in the very crime whose investigation he had initiated, testified before the judge that the book was not the same one that had been stolen from the Library—nor, however, was it the facsimile he’d sold to Pastore. It was, he explained, a third book, similar to the others. It had the correction on the fifth line of the poem, but the stroke on the correction line was different. And unlike the stolen copy, this one was bound, its original cover intact.

Vaccaro denounced Casares as a liar and even showed up at the entrance of the yearly antiquarian book fair to hand out flyers against “book thieves.” The issue was only settled when Juan Manuel Peña assured everyone that, indeed, contrary to Casares’s claims, this was the book that had belonged in his collection, the one he’d sold to the Library.

The judge agreed and ordered that it be returned. And that was that: in mid-September 2007, the investigation was officially closed. “Borges returns to the National Library,” celebrated La Nación. No punishments were imposed.

“Judge Ballestero acted with precision and fervor, to make a play on words,” announced Horacio González, the library’s new director—the fifth since the theft.

* * *

Three weeks before the ruling, a Uruguayan man named César Gómez Rivero was looking up some books from the fifteenth century at Spain’s National Library, in Madrid. Without anyone noticing, he used a razor blade to cut out nineteen unique prints, including two world maps from Claudius Ptolemy’s Cosmographia, printed in 1482 and often considered some of the most beautiful woodcuts of early world maps. He rolled them up carefully and hid them under his clothes. That same night, he boarded a plane to Buenos Aires. It was the biggest robbery in the history of the Spanish Library; days later, when the incident became public, its director was forced to resign.

Interpol traced the stolen prints—Ptolemy’s map alone was valued at €110,000—all the way to Daniel Pastore’s antique bookshop, which had listed them in its catalog. He had already sold some of them, over the Internet, to clients in Australia and the United States. Pastore received a light sentence of community service, but the international scandal was such that even before the Antiquarian Booksellers Association could expel him, Pastore shuttered his store.

His partner in the London auction, Massimo De Caro, was caught a few years later in Italy. In April 2012, it was revealed that at least 1,500 historic books—and maybe as many as four thousand—had disappeared from the Girolamini Library in Naples. De Caro had been the library’s director for eleven months. The police found boxes with hundreds of stolen books at his house.

* * *

Seven years after Fervor de Buenos Aires’s return to the library, and fifteen years from the beginning of this story, Casares is still bitter about the damage done to his reputation, which has never repaired. He assured me once more that the book returned to the library was not the stolen copy, and, sensing my skepticism, he insisted: in the correction of the “Villa Urquiza” poem, the line that Borges drew between the crossed-out article and its replacement was of a different length and inclination. It was not necessary to have the original copy to compare; the facsimile was enough. He’d handed it to the court to make the comparison, but they hadn’t bothered to check.

Seven years after Fervor de Buenos Aires’s return to the library, and fifteen years from the beginning of this story, Casares is still bitter about the damage done to his reputation, which has never repaired. He assured me once more that the book returned to the library was not the stolen copy, and, sensing my skepticism, he insisted: in the correction of the “Villa Urquiza” poem, the line that Borges drew between the crossed-out article and its replacement was of a different length and inclination. It was not necessary to have the original copy to compare; the facsimile was enough. He’d handed it to the court to make the comparison, but they hadn’t bothered to check.

Many details seem to refute him. If he’d seen the stolen book in Pastore’s hand, it seemed clear that Pastore had kept it. Then there was the question of Pastore’s history, and that of his partner De Caro. Plus, Peña, the book’s original owner, had recognized it as his own. If this weren’t enough, Vaccaro, the other complainant, had assured me that a few years after the scandal, Pastore had invited him to lunch to tell him “the truth.” He said the book was, in effect, the one stolen from the library, but that it had been bought in good faith from John Wronosky—an antique bookseller from Boston who offers Borges manuscripts (of dubious authenticity, according to some collectors) for up to half a million dollars.

“Next time someone comes to me with a stolen book,” Casares said, “I will just keep my mouth shut.”

As I was leaving Buenos Aires for several months, I asked a student to go to the library, request the recovered copy, and send me a scanned copy of the “Villa Urquiza” page.

After some toing and froing, they did not allow him to see it.

Were they hiding it?

I e-mailed the director, Horacio González: They were telling me the recovered book was not the one that had been stolen. Was this true?

To my surprise, González replied, “It is as you say. Fervor de Buenos Aires, first edition, is a recovered book that does not seem to be the one that was stolen.” Laura Rosato, the curator of the Borges collection, was copied on the e-mail. She confirmed it: this was, indeed, another book.

Where had this copy come from?

What had happened to the stolen one?

No one knew.

Graciela Mochkofsky is an Argentine journalist and writer. She is currently a fellow at the Dorothy and Lewis B. Cullman Center for Scholars and Writers at the New York Public Library. She is working on a new book about an unprecedented wave of massive conversions into Judaism throughout Latin America.

Damn the Kafkaesque, and Other News

Franz Kafka: he’s more than just an adjective.

“The Pulitzer Prize is a human enterprise. Editors, past winners and a few Columbia University pooh-bahs comprise the board that awards them. Like all such collections of human beings, Pulitzer Boards are capable of brilliant good sense, and egregious errors.”

Cynthia Ozick’s stirring defense of Kafka, the man: “Whoever utters ‘Kafkaesque’ has neither fathomed nor intuited nor felt the impress of Kafka’s devisings. If there is one imperative that ought to accompany any biographical or critical approach, it is that Kafka is not to be mistaken for the Kafkaesque.”

Was the first-ever emoticon in a seventeenth-century poem? Maybe! But probably not.

Thoughts on the twenty-fifth anniversary of the Mazda Miata: “I was frequently stopped while driving. Fellow Miata owners waved enthusiastically. Clubs were formed. People constantly made offers to buy my car. Miata is a car that’s worn like a jacket. The lithe driving dynamic is a second skin.”

But the Miata was never endorsed by a man who’s walked on the moon: the only car to claim that honor is the Volkswagen Beetle, which found an unlikely advocate in Buzz Aldrin.

April 15, 2014

Happy Motoring

Rand McNally published its first road atlas on April 15, 1924. It was called—in a touching testament to the marketing of yore—the Rand McNally Auto Chum. Many hours of intrepid googling have failed to yield a photo of the Chum, but I did find a retrospective of atlas covers, and this commemorative press release, which catalogs some of the decidedly unchummy features of the 1924 atlas. A few of the things it didn’t do:

Did not identify roads by number; instead roads were listed by their names, such as Roosevelt Highway. In fact, the atlas depicted zero miles of interstate, as those roads did not yet exist.

Did not include an index for cities, or other places. If a driver didn’t know where a town was located, he or she would have to page through the atlas to find it.

Did not appear in full color. The 1924 atlas was printed in only two colors, dark blue and red. The first full-color edition was printed in 1960.

One can only imagine the faces of so many vexed motorists as they tossed their unindexed, two-tone Chums out the windows of their stranded Model Ts.

As with so many reference texts, the road atlas has fallen into desuetude, for reasons obvious to anyone with an Internet connection. In its coverage of the Rand McNally anniversary, Yahoo! News already presumes that its readership knows nothing of atlases past; their tone is that of a nostalgic grandfather. “Before there were smart phones and Google Maps,” the story begins, “people relied on road atlases and paper maps stored in their glove boxes.” Gee!

We’ve also lost the complimentary road maps once offered by gasoline companies, a few of which are pictured above. (Look closely for the title of a Flannery O’Connor short story in one of them.) It was the gas giants who helped to underwrite the cost of the first atlases: better maps meant more people on the road, and more people on the road meant more gasoline sold.

The Yale University Library hosts an old but serviceable guide to early road maps, and its text, by Douglas A. Yorke Jr. and John Margolies, provides an excellent précis on the importance of oil-company cartography, which, with its flashy art and sloganeering, amounts to a kind of petrol propaganda:

The oil-company road map became the primary medium through which Americans found their way on the ever-growing network of the national roads and highways … By the twenties, most major oil companies had some form of promotional map program. The covers often featured a man and a woman discovering the joy of driving through the countryside, enjoying the freedom and mobility the automobile offered … The 1927 Standard Oil map of Ohio compares the motorist to the pioneer in the Conestoga wagon, blazing trails and discovering new lands. The Kentucky Standard Oil map of the same year has a three panel spread, depicting a motorist using a free map to plan their descent into the rolling valley below. Oil companies were encouraging the automobile owner to travel and explore the country—using their gasoline.

Hate-Reading

Frederic Leighton, Study at a Reading Desk, 1877

I am a rereader by nature. Like most rereaders, I have a few beloved favorites—Sisters By a River, or We Think the World of You, or A Girl in Winter—that bring me comfort as well as pleasure. Then there are a few books that I know just as well as these, and revisit just as often, but which I loathe. The writing is not bad; that would make the reading a chore instead of a sick pleasure. Usually I despise the narrator in some way—for being out of touch or oblivious or solipsistic. I particularly hate certain culinary memoirs and novels with leaden dialogue. The irritated satisfaction these books give me is akin to the irresistible pain of worrying a sore tooth.

I never hate-read work by someone I actually know. A few times I have gone on to learn too much about the writer of one of these books, and the pleasure went away. The wealth of available information may feed some kinds of animus; mine depend on the hermetic isolation of my own obscure prejudices. They must not be humanized.

Why do I do this? You don’t revisit a bad restaurant to revel in the terrible food, or relisten to an awful album to reassure yourself that it was as bad as you remembered. I do understand wanting to share something so jaw-droppingly appalling that you suddenly feel everyone needs to know about it. Can you believe this! you want to say, about some weird travelogue or implausible novel. But you aren’t, generally, inclined to repeat the experience.

What makes hate-reading strange is that it is solitary, and it is time-consuming. You are voluntarily closeting yourself with the hate-object. It simply can’t be healthy. Or can it? As Hazlitt has it, “without something to hate, we should lose the very spring of thought and action.” Or at least a relatively harmless outlet.

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers