The Paris Review's Blog, page 711

April 28, 2014

The Hypnotic Act

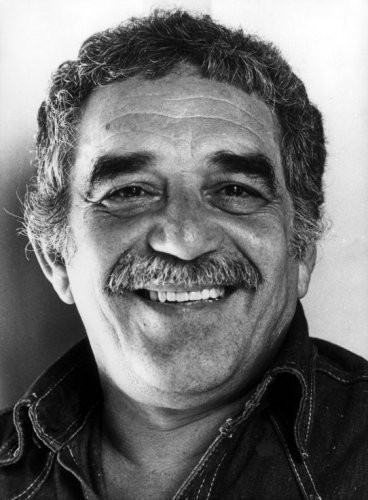

Silvana Paternostro (front row, second from right) poses for a photo with her journalism class, taught by Gabriel García Márquez (third row from front, center, in glasses).

Last week, we had the pleasure of featuring Silvana Paternostro’s “Solitude & Company,” an oral biography of Gabriel García Márquez from our Summer 2003 issue. But Silvana also wrote, for our Winter 1996 issue, “Three Days with Gabo,” an essay about the time she spent at a small journalism workshop hosted by García Márquez in Cartagena that spring. As Silvana writes: “For us, Latin American journalists in the early stages of our careers, he is a role model. We like to say that before he was a novelist he was a reporter. He says he has never stopped being one.” The essay provides a charming account of García Márquez’s professorial style—somehow both whimsical and practical—and it serves a reminder of his formidable talents as a journalist and an observer:

It has been said that Gabo is too creative to be a good journalist. After all, he is the same writer who in his novels, with a straight face, had Remedios the Beauty levitating to the skies and the smell of Santiago Nasar after his well-announced death penetrating the entire town.

As if reading my mind he says, “The strange episodes in my novels are all real, or they have a starting point, a basis in reality. Real life is always much more interesting than what we can invent.” He says that the ascension of Remedios the Beauty was inspired by a woman he saw spreading clean white sheets with her arms stretched out to the sun. He has also said that “to move between the magical and the incredible, one has to become a journalist” … He begins to read paragraphs out loud from some of our articles; he offers light copyediting. Some of the sentences are too long and Gabo pretends to be choking as he reads along. “We have to use breathing commas,” he says. “If not, the hypnotic act does not work. Remember, wherever there is a stumble, the reader wakes up and escapes. And one of the things that will make the reader wake up from hypnosis is to feel out of breath.”

We’ve made Silvana’s essay available online for free; you can read it here. It’s a fitting conclusion to our tribute to García Márquez—he will be missed.

The Way of All Flesh, Etc.

The New Orleans Advocate reports that “Mickey Easterling, a New Orleans socialite known as much for her grand lifestyle and outlandish hats as for her civic, cultural, and political activism, died Monday at her Lakefront home.” Easterling was a character of the old school: a generous benefactor of many charities who wintered in Morocco and was given to sweeping pronouncements.

Her family honored her wishes by throwing a festive wake-cum-cocktail party. The centerpiece of the shindig was the deceased herself—propped up in full regalia and makeup, just as in life. Reports the Daily Mail, with photos,

The consummate hostess, she was never without her glass of champagne or cigarette holder, and wore a flamboyant feather boa, bonnet, and a diamond-studded brooch that said ‘Bitch’ … To Easterling’s right, on a small table, sat a bottle of her favorite Champagne—Veuve Clicquot—as well as a pack of American Spirit cigarettes, and in her right hand was a Waterford crystal Champagne flute, the kind she used to carry around with her sometimes when restaurant glassware wouldn’t suffice.

While the spectacle was, it must be said, somewhat macabre, it was not unprecedented. In a recent piece titled “Dead People Get Life-Like Poses at Their Funerals,” ABC News chronicles the practice of “Extreme Embalming”—which sounds far too much like the world’s most horrifying reality show. ABC cites three other cases: just enough to make the “trend” cutoff. It is, needless to say, still a fringe practice. Says one Pennsylvania mortician, “Most funeral homes, the most extreme thing they might do is dressing the deceased in shorts.”

Personally, I take a live and let live—or its converse, I guess—approach to these matters. One can’t help but wonder if close encounters with the extreme embalmed might have unfortunate, Three Faces of Eve–style consequences for children of an impressionable age. But then, there are worse things than mementi mori.

For many years, Mickey Easterling kept company with the composer and writer Paul Bowles. In his classic 1949 novel The Sheltering Sky, Bowles gives us one of the most trenchant of assertions on the subject of mortal coils.

Death is always on the way, but the fact that you don’t know when it will arrive seems to take away from the finiteness of life. It’s that terrible precision that we hate so much. But because we don’t know, we get to think of life as an inexhaustible well. Yet everything happens a certain number of times, and a very small number, really. How many more times will you remember a certain afternoon of your childhood, some afternoon that’s so deeply a part of your being that you can’t even conceive of your life without it? Perhaps four or five times more. Perhaps not even. How many more times will you watch the full moon rise? Perhaps twenty. And yet it all seems limitless.

Says Easterling’s daughter, “It’s a really nice way to say,‘The party’s over.’”

Recapping Dante: Canto 27, or Let’s Make a Deal with the Pope

Amos Nattini, I Consiglieri Fraudolenti, date unknown.

We’re recapping the Inferno. Read along! This week: the price of wheeling and dealing with the Pope.

In Canto 27, just as Ulysses’s incandescent spirit departs, another burning sinner approaches Dante. This time, because the spirit is Italian, Dante speaks with him, instead of allowing Virgil to interpret; and though the sinner is never identified by name, the biographical information he offers suggests that he is Guido da Montefeltro, a well-known Ghibelline captain who fought a good many battles.

Much like Vanni Fucci, Guido is not eager to speak with Dante. He decides to speak only because he believes that Dante is one of the damned, and will never again be among the living—he feels secure that his story will never be heard again. Oops.

Guido says that Pope Boniface VIII solicited him for guidance on conquering Palestrina, a Ghibelline fortress. Guido demurred, but the Pope assured him his soul would be saved in exchange for his help—and that convinced Guido to help out, even if he had his doubts about the pope. Upon Guido’s death, St. Francis came to escort him to heaven, as promised, but a demon intervened on the grounds that no man can be pre-absolved for a sin he hasn’t yet committed. The Pope’s promise was thus null, and Guido was led instead to Minos, who deemed him guilty of fraudulent counsel.

Guido is a lot like Ulysses, whom we heard from in the last canto—he’s just as cunning, and he nurses the same sense of restlessness:

When I saw I had reached that stage of life

when all men ought to think

of lowering sail and coiling up the ropes,

I grew displeased with what had pleased me once.

Guido’s similarity to Ulysses raises a few questions about these two cantos. Namely: why is there so much ambiguity in the nature of their sin? The strongest theory for cantos 26 and 27 is that the sinners are guilty of some form of fraudulent advice—which covers all manner of evil or duplicitous counsel. But it is never fully explained what exactly the sin is.

Is it that Ulysses’s sin is the plan he hatched at Troy, and Guido’s is helping Boniface quell a rebellion? This seems a bit strict: Guido and Ulysses are not so much giving fraudulent advice there, after all. They’re simply strategizing. If we consider that for a general, the nature of commanding an army in battle is outsmarting or overpowering the enemy—what Aristotle calls necessary and probable behavior for men of their nature in their situation—the manner in which they accomplish their victories seems insignificant. We may begin to suspect that Ulysses and Guido gave fraudulent advice not in their military and political stratagems, but in their advice to themselves. In a broader sense, their sin is hubris—they thought they could beat the system. They set off in their own way once more, even at an age when men should lower their sails and coil up the ropes. They acted as their own fraudulent advisers.

To catch up on our Dante series, click here.

Alexander Aciman is the author of Twitterature. He has written for the New York Times, Tablet, the Wall Street Journal, and TIME. Follow him on Twitter at @acimania.

On Epitaphic Fictions: Ben Franklin, W. B. Yeats

The first in a three-part series on writers’ epitaphs.

John Singer Sargent, William Butler Yeats, 1908

“In lapidary inscriptions, a man is not upon oath.” —Samuel Johnson

Got a brittle, expensive medium? Bring an elastic ethics.

Dr. Johnson understood that words on headstones provide cover stories. Acts of make-believe inscribed in stone may be as banal as an incorrect—or fudged—year of birth; the phrase “In Loving Memory” must be a fiction much of the time. On the other hand, great writers have composed words for headstones, real and imaginary, that offer us complex fictions in which we may dwell, as if in compensation for loss. For such writers, good grief is infused with imagination.

Witness this epitaph in the collection of the Yale Library, from an autograph manuscript composed circa 1728:

The Body of

B. Franklin,

Printer;

Like the Cover of an old Book,

Its Contents torn out,

And Stript of its Lettering and Gilding,

Lies here, Food for Worms.

But the Work shall not be wholly lost:

For it will, as he believ’d, appear once more,

In a new & more perfect Edition,

Corrected and Amended

By the Author.

He was born Jan. 6. 1706.

Died 17

The Benjamin Franklin who wrote this was twenty-two, living in Philadelphia, a runaway apprentice passing as a journeyman printer for going on five years, daily making good on his lie by daily making good books, pamphlets, newspapers, broadsides, and printed ephemera. The fictions elaborated in this text and the fictions at play in Franklin’s life as fabricated in his Autobiography (1793) overlap prodigiously. Ever the forward thinker, Franklin sets himself down here not with a lie, but as a make-believe construction of impressionable paper and ink and cloth and thread and board. A man in his prime, nowhere near his final reckoning, he is already concerned with judgment, about how he might be read. His vision anticipates his revision, the replacement of signatures he’s struggled to compose with signatures composed by the Lord.

An epitaph typically reinforces values we look for in strong poems: gravity, brevity, levity, and the authority of the speaker’s experience, granted in epitaph’s special case by his death. Franklin is ahead of himself in his rock-solid grasp of these conventions. First, he imagines the grief of those who attend this text as grave, and does not fail to evoke the seriousness of death. Second, he is brief, for his estate or his survivors must pay for his epitaph by letter and line and inch of brittle stone, in a world where a chisel is expensive. Third, he responds to the downcast gaze of family and friends with winking humor, in a metaphor hammered at each caesura, punctuation mark, and line-break until it is so beaten out it suggests the lightness of eternity. (Recall John Donne’s “Valediction: Forbidding Mourning,” and its fiction of a love “like gold to aery thinnesse beate.”) Lastly, though these words were not carved on the tomb where his body rots beside his wife’s, there is a clear implication that Franklin’s center-justified prose provides instruction to his survivors.

Franklin’s handling of his epitaph, which is of no use till God knows when, gives us a sharper likeness of him than the hundred-dollar bill. He offers us a concrete figure for his Christian faith, a book; yet he conveys a sense that his firmest faith is vested not in what the Good Book says, but what his forthcoming Autobiography will tell us. Whatever rewriting his soul will suffer, Franklin anticipates that he will be revised—corrected, and amended, and even gilded—on this side of the grave, while there is still time for him to enjoy his being issued in a second edition.

* * *

For the genre, Franklin’s imaginary inscription is somewhat long-winded. Epitaphic fictions may be extremely compressed; sometimes they achieve greater scope because they are tiny portions of larger works. William Butler Yeats’s epitaph—the final stanza of his late poem, “Under Ben Bulben”—is measured out in three lines and two short imperatives, a mere twelve syllables. Even so, it conjures two fictions.

Yeats’s speaker’s first command is so idealistic it may not be followed. His second command would be nonfiction only when its reader is mounted.

In the year of Yeats’s birth, conveyance on horseback meant the fastest speeds attainable (even today, speed corresponds to power). At the time of Yeats’s reburial (the body was moved from France to Ireland in 1948) under the stone pictured above, the first world was on the cusp of the jet age. Even in Ireland, Yeats might have said, “That is no country for old men.”

Perhaps the imperatives on his stone are addressed to a fictional someone who literally remembers the past that Yeats remembers, some “aged man,” “some paltry thing, / A tattered coat upon a stick… ” They may even be addressed to a more idealistic fiction, a present-day reader come to pay his respects, a reader for whom elevated views and dignified gaits and romantic clops of iron shoes on cobblestone are continuous with the present—a reader who, like Yeats, bears the past inside him. Either way, twelve quick syllables after such a visitor arrives, the speaker of the epitaph has told him to move on. Yeats never really sailed to Byzantium. No one was ever really going to approach his grave on the back of a horse. And only in fictions do we meet anyone capable of casting such a cold eye on life or death.

Daniel Bosch is Senior Editor at Berfrois . His sonnet sequence “To a Barista” is at The Common ; his meditation on race and invocation will appear later this week at The Morning News .

Malamud Lookin’ Good, and Other News

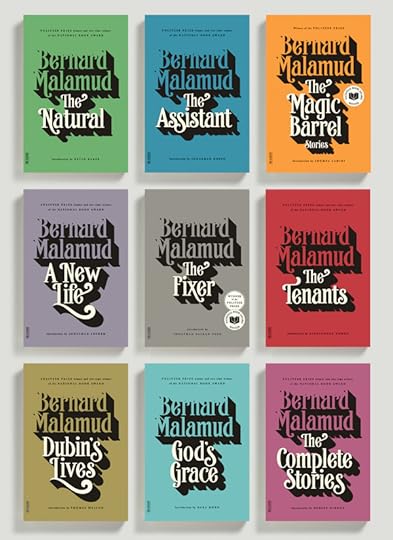

Charlotte Strick’s new designs for the Bernard Malamud centenary. Image via FSG Work in Progress

Here’s our Southern editor, John Jeremiah Sullivan, on the art of preservation—not in the sense of manly survivalism but in the sense of making jam. His essay was recently nominated for a James Beard Award.

And here’s Charlotte Strick, our art editor, interviewed about her sharp new designs for the Bernard Malamud centenary.

While we’re at it, Daily contributor Caleb Crain has asked, “how much gay sex should a novel have?” (“The half answer, half protest that immediately springs to mind is, It depends. Many are the conditions that it depends upon.”)

And Daily contributor Willie Osterweil found that today’s sports movies have comparatively few feats of athleticism in them. “There’s a new breed of sports movie in town, one that does away with all that pesky team-building and ersatz democracy. These films celebrate the real heroes of sports, the real heroes of any workplace: the bosses.”

The lost art of memorizing poetry: “Many of today’s prominent poets seem to be writing poems that actively resist memorization. Take John Ashbery, for example … As I walked uphill, repeating Ashbery’s lines to myself, I found them as slippery as an eel.”

Why do we tend to place painful episodes in parentheses? A variety of literature has “windows in a wall of verse or prose that suddenly open on an expanse of personal pain. Masquerading as mere asides, they might hold more punch than parentheses are usually expected to hold, more even than the surrounding sentences, and have all the more impact for their disguise as throwaways.”

April 27, 2014

Before You Watch Mad Men Tonight

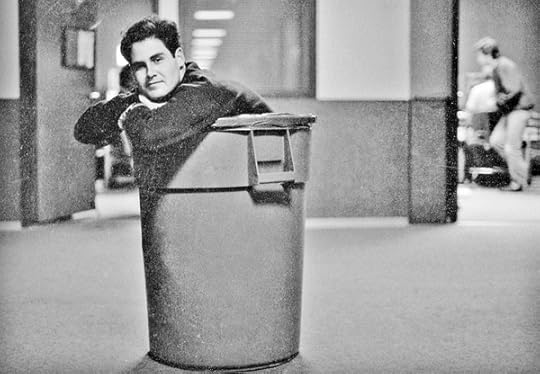

Matthew Weiner, in film school, 1990. “I realized that if you could write, you could have complete control.”

Read The Paris Review’s interview with Matthew Weiner, which appears in our latest issue and is, as of today, available in its entirety online. (If you bring it up with your friends and they’re like, Yeah, I read that two months ago—what rock have you been living under, it’s probably because they subscribe to The Paris Review. But so can you.)

Weiner discusses the writers who’ve influenced him:

I don’t make lists or rank writers. I can only say which ones are relevant to me. Salinger holds my attention, Yates holds my attention. John O’Hara doesn’t, I don’t know why—it’s the same environment, but he doesn’t. Cheever holds my attention more than any other writer. He is in every aspect of Mad Men, starting with the fact that Don lives in Ossining on Bullet Park Road—the children are ignored, people have talents they can’t capitalize on, everyone is selfish to some degree or in some kind of delusion. I have to say, Cheever’s stories work like TV episodes, where you don’t get to repeat information about the characters. He grabs you from the beginning.

And his early dalliance with poetry:

INTERVIEWER

What were your poems like?

WEINER

Pretty funny, a lot of them, in an ironic way. And very confessional. A lot like what I do on Mad Men, actually—I don’t think people always realize the show is super personal, even though it’s set in the past. It was as if the admission of uncomfortable thoughts had already become my business on some level. I love awkwardness.

And the origins of the Mad Men pilot:

Four years after I’d started working in TV, I wrote the pilot for Mad Men. Three years after that, AMC wanted to make it. They asked me, What’s the next episode about? So I went looking through my notes. Now, imagine this. At this point it’s 2004—I’m writing for The Sopranos—and I go back to look at my notes from 1999 ... but then I find this unfinished screenplay from 1995, and on the last page it says “Ossining, 1960.” Five years after I’d abandoned that other screenplay, I’d started writing it again without even knowing it. Don Draper was the adult version of the hero in the movie. And there were all of these things in the movie that became part of the show—Don’s past, his rural poverty, the story I was telling about the United States, about who these people were. And when I say “these people,” I mean people like Lee Iacocca and Sam Walton, even Bill Clinton to some degree. I realized that these people who ran the country were all from these very dark backgrounds, which they had hidden, and that the self-transforming American hero, the Jay Gatsby or the talented Mr. Ripley, still existed. I once worked at a job where there was a guy who said he went to Harvard. Someone finally said, You did not go to Harvard—that guy didn’t go to Harvard! And everyone was like, Who cares? That went into the show.

It’s the perfect primer for tonight’s episode, and it’s available in full here.

April 25, 2014

What We’re Loving: Archives, Architects, the Arctic Sky

Lebbeus Woods, San Francisco Project: Inhabiting the Quake, Quake City, 1995. Image via the Drawing Center

Sadie Stein already recommended Arlette Farge’s little book-length essay The Allure of the Archives. A year later, I have to second the recommendation. On the surface, this is a personal memoir by a feminist historian whose research—into eighteenth-century police files—fundamentally changed our picture of pre-revolutionary Paris. But really this is a handbook about how to write, how to think about, history. Gripping, graceful, and beautifully translated by Thomas Scott-Railton, it captures the fun and the dangers of library work like nothing I’ve ever read. —Lorin Stein

A new anthology from Brick introduced me to Don DeLillo’s “Counterpoint: Three Movies, a Book, and an Old Photograph,” an essay from 2004. That title belies both the piece’s range and its force of concentration. It looks at Glenn Gould, Thelonious Monk, and Thomas Bernhardt, three isolated, brilliant men who craved and feared the seclusion that came with their work. DeLillo is interested not just in their difficult lives but in the cultural consensus we reached upon their deaths—who did we decide these men were, and why? As its images begin to collect, all of them rendered in that laser-cut DeLillo prose, the essay becomes a haunting account of the distance between an artist and his audience, his art, and himself. DeLillo has a rare gift for writing about the sensory experience of art, for tracing the vectors of meaning in sight and sound. “In a busy diner,” he writes of a scene from Thirty Two Short Films About Glenn Gould, “there are voices in layers and zones, some folded over others, in counterpoint.” And he condenses The Fast Runner into a solitary image, an image of, well, overwhelming solitariness: “The man is running, eyes wild, into the arctic sky.” —Dan Piepenbring

Lebbeus Woods, who died in 2012, was an artist’s architect. He imagined the buildings that cities would need when calamity came calling. His work exists almost exclusively as experiment—only one of his ideas was actually constructed—and 175 of his graphite dreams are currently on display at The Drawing Center in SoHo. Some look like gashes in the side of a building, or what would happen to a street if it suddenly woke up. Some are like seedpods split open and engorged, a home for one suspended by a slender stalk, and some are simply floating, free of the city entirely. Or maybe these are cities, untethered, finally free to found themselves. —Zack Newick

Growing up a diehard Cubs fan on the North Side of Chicago, I rarely encountered many South Siders. But when my family moved out to the Northwest suburbs, I came to know a few White Sox fans, and only then did I fully understand a rivalry that’s grown since the 1906 World Series. Now, thanks to The Upshot (as well as millions of baseball fans avowing their allegiances on Facebook), we can use maps to visualize the exact Chicago neighborhoods “where White Sox jerseys stop being welcome,” along with the borders between the Yankees and the Red Sox, the Dodgers and the Angels, and—let’s just forget about the poor Mets. —Justin Alvarez

Spring means that getting dressed is no longer a matter of piling on as many layers as possible and keeping rain boots on standby—it now seems safe to put away down jackets and woolen tights. On the street, beautifully dressed women keep reminding me of Jil Sander’s 1998 ready-to-wear show, with its perfect shin-length hems and bluish shades of white. I’ve always thought of this show as the last triumph of nineties minimalism before we were hit by a wave of decorative luxury, with John Galliano at its crest. (Let’s not forget the $25,000 dresses of Dior’s “homeless” collection of 2000, or the weird mania for Louis Vuitton luggage.) —Anna Heyward

Ever So Humble

Andreas Duncan Carse, Bargain Hunters

This morning my family went to several tag sales, as is our habit. Saturday is of course the major day for such things, but there are always a few that begin earlier, and a careful perusal of the local papers had yielded three, of which one looked promising. It was an estate sale, and the ad boasted “collectibles,” “books,” and a 1991 Chrysler LeBaron.

Since my parents sold their house, they have talked a lot about “divesting.” After clearing out her own parents’ home, my mom said repeatedly that she did not want to burden me and my brother with a similar task, and they had an enormous, slightly morbid tag sale of their own. And yet this has not curtailed their activities: every Thursday they examine the paper, annotate the sales page with arrows and underlines and the occasional exclamation mark, and plot their route.

By chance, the sale was located across the street from the “Home Sweet Home” museum, where, in 1823, the actor and dramatist John Howard Payne composed the eponymous song. It quickly became a standard, reprised in shows and bars across America. Reportedly, “Home Sweet Home” was banned from Union camps in the Civil War because it made soldiers too homesick and lowered morale.

The estate sale was held in a saltbox house, clearly old. It was an old-lady house. The kitchen felt vaguely midcentury; the floors were covered with grubby carpeting. Upstairs, a bedroom and adjoining bathroom had been fitted with metal safety railings. The sale was run by one of the services people hire to clear out the homes of the dead, and it was already teeming with people who pored over the bookshelves and boxes of kitchen utensils like a bunch of Dickensian rag-pickers. My mom greeted several regulars whom she knew.

There were rain bonnets. There were doilies. There were figurines. There were boxes of recipe cards in a spidery hand. There were polyester pussy-bow blouses. There were pamphlets from the local Episcopal church. There was a china dish still filled with cellophane-wrapped hard candies. As if it needs saying, there was a life. The woman running the sale told us the owner had been ninety-nine.

As for the dowdy car, we were informed that the owner had logged fewer than ten thousand miles on it.

I ran across a small, mildewed, government-issue 1941 prayer book, signed by the woman’s late husband: “To my wife, Camilla.” Her ID from the same period showed that she had been a nurse; later documents bore witness to her time in the local Ladies’ Village Improvement Society. There was not much of value, and not much one wanted to buy. My mother commented on how high the prices were.

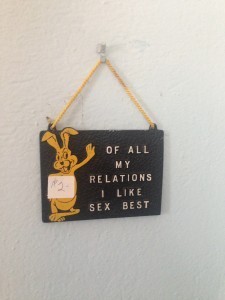

I picked through a tray of clip-on earrings, trying hard to find something I wanted, although my mother had already found a stack of books. It was theatrically depressing. When I ran across a hardcover called Laugh While You Can, I thought I might have to leave, wait for my mother outside in the car. I took a final tour through the upstairs rooms, including the one with the safety bars that had clearly belonged to the dead owner. And there, on the wall, was this:

After that, everything was bearable.

And at the end of the morning, my parents had purchased a DVD of No Country for Old Men and had told the woman at the sale to call them if the price of the Chrysler went down.

A Marvelous Crutch: An Interview with Brad Zellar

McKenna. Corsicana Tumbling Academy. Corsicana. Photo: Alec Soth, via LBM Dispatch

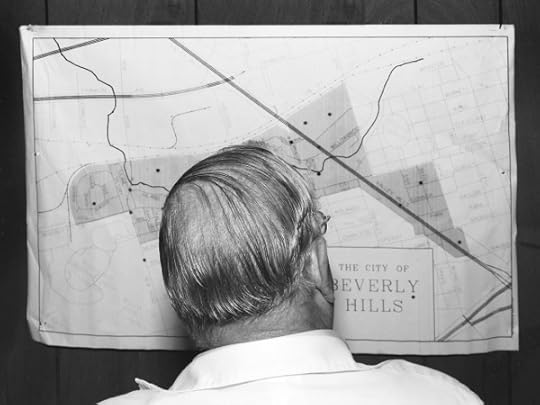

Douglas. Beverly Hills. Photo: Alec Soth, via LBM Dispatch

Fellowship Church. Grapevine. Photo: Alec Soth, via LBM Dispatch

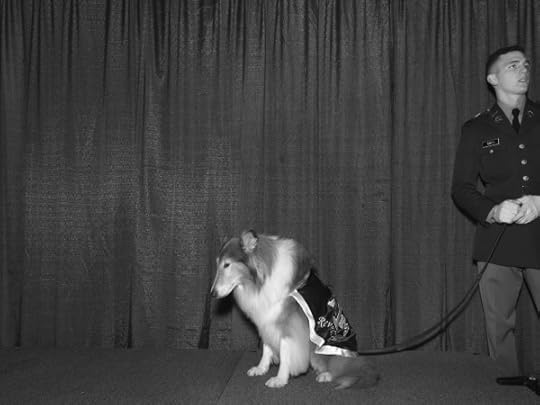

Reveille VIII, Texas A&M mascot. College Station. Photo: Alec Soth, via LBM Dispatch

Texas City, “The town that would not die.” Photo: Alec Soth, via LBM Dispatch

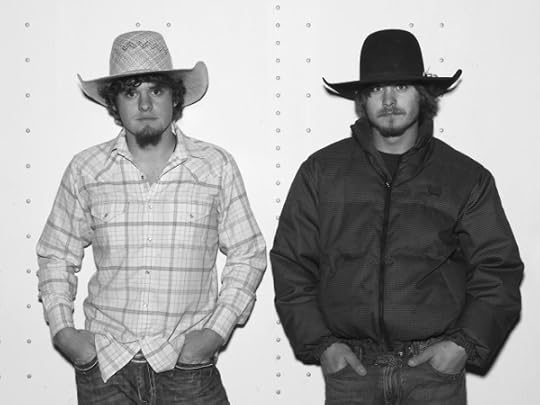

Cory and Justin, Bull riders, in San Antonio. Photo: Alec Soth, via LBM Dispatch

Execution of Jerry Martin. Huntsville Prison, Walls Unit. Photo: Alec Soth, via LBM Dispatch

Brad Zellar’s writing has appeared in daily newspapers from Minnesota and in an expansive blog called Your Man for Fun in Rapidan; he has chapters and essays in collections like The 1968 Project and Twin Cities Noir, and occasionally he writes fiction, which he tells me he publishes “under an assortment of fake names.” But he’s most comfortable writing about photographs, as he did in the book Suburban World: The Norling Photos, and in his most recent project with the photographer Alec Soth, the LBM Dispatch.

Named for and printed by Soth’s limited-run publishing house, Little Brown Mushroom, the Dispatch reimagines the iconic American road-trip photography book as a series of small newspapers, each of which chronicles a quick trip Zellar and Soth have taken through a different state or territory. Previous Dispatches have covered Michigan, Ohio, and California’s “Three Valleys—Silicon, San Joaquin, and Death.” The most recent includes images and stories from the Texas Triangle.

I wanted to know about the writing process for the Dispatch, and how Zellar chooses the issues’ many quotations from historical and literary sources. But I was most curious to hear his thoughts on writing to accompany images. Not quite a photo-interpreter in the Berger/Sontag tradition (though he is a great writer in the “how to look” sense), Zellar embraces photography as a fan, and he’s not afraid to let images do the talking when necessary. In Zellar’s work, photos are windows, excuses for curiosity—above all, the Dispatch embodies the devotion to stay curious.

A lot of your work, here and elsewhere, has accompanied photos. How does it affect your own writing to know that pictures will share its space? How does it make you think about your purpose as a writer?

The public library in my hometown had a terrific collection of photo books when I was a kid. I was an obsessive reader, but it was from those photo books that I formed my first real impressions about what the world looked like. And they played a huge role in cementing a resolve that I very much wanted to travel and see that world. I used to spend hours hunched over William Eggleston’s Guide, the first Diane Arbus monograph, and a book of vernacular American photographs called The Champion Pig.

From an early age I used to write stories based on photographs, and I’ve never really stopped. I have a large collection of found photos, I like to take photos myself, and I just get a kick out of looking at pictures and trying to animate them with words. I love that photos represent so many possible realities, and they’re sort of a laboratory for exploring points of view. You have the people in the pictures, obviously, each of them a different voice with a different version of whatever story is being told, you have the people outside the frame or lurking in the peripheries, and then, of course, you have the photographer.

I look at photos and hear voices. I imagine all the other pictures and moments from the same roll of film. I make forensic inventories of every piece of information I can glean from a photograph, and a list of questions the photo poses for me. Working with a photographer is such a marvelous crutch for a writer. There’s so much I don’t have to write down, because I know I’m going to have Alec’s evidence to work with.

You’ve said that the Dispatch is very much about quickness—the trips are short and fast, the work comes almost immediately. But a lot of your writing is curatorial, the quotes and excerpts and so on.

The planning and preparation generally takes more time than the actual trips. I usually leave town with a notebook full of quotes, facts, and figures, very little of which ever ends up getting used. The whole focus of a trip can turn in an instant when we’re working, and we’re both very much aware of that by now.

A big part of what allows us to move quickly once we’re on the road is the amount of research, planning, and preparation we do before we get in the van. Once we’ve targeted a state or region we’ll usually start brainstorming about things we know about the place—quick, off-the-top-of-the-head stuff. The history, literature, music, and art that’s been produced there. I’ll assemble a mixtape and a small library of relevant books. I like histories, but my initial interest is always fiction and poetry. We’ll also look at other artists who might have worked in the area. From there we’ll dig into current events, local news, demographics, and events calendars, essentially trying to put together a list of possible themes as well as an initial itinerary. We both like to have a decent idea where we’re headed every day, and some notion of what we’re interested in there. Serendipity always plays a huge role in the trips, obviously, but generally that’s the result of following our original trail and turning up something of interest along the way.

There are always those moments when, for lack of a better word, the arc of the whole trip swims into focus, and that usually leads us to start looking more intently for stuff that may not have been on our original radar. It’s usually a thematic Eureka—in “Upstate” [Dispatch #2], for instance, we started feeling like the whole swing of the thing was taking us back into time, history, and the wilderness.

Do you talk at all about your goals, as far as depiction goes? What’s the larger motive as far as what ends up in the Dispatch and what doesn’t?

Alec and I started with the idea that we would just find a way to work around home, and for a period of several months, purely for fun, we were exploring the exurban fringes of the Twin Cities, pretending to be newspapermen. In the course of these rambles we ended up in places that, though they were no more than forty minutes from my doorstep, might well have been foreign countries. Little townships, small town service clubs and fraternal organizations, church dances, crime scenes, small business expos, stuff like that.

In a place called Linwood Township—maybe thirty miles from Minneapolis—we visited the town hall, which was located in a tin, prefab building. Every single expenditure for the township had to be voted on by a show of hands from every taxpayer who showed up for the meeting. In an adjacent room there was a senior citizen center. The whole thing felt like something you’d stumble across in the Yukon. The township had recently planned a big centennial celebration. It was going to run over several days, and they sent out press releases, only to discover later, through a call from the county historical society, that they were off on the date by something like forty-nine years.

We weren’t looking for provincialism. We went into the project expecting to discover the milfoil of corporate America—the same sort of bland development you’d encounter in the suburbs and city just to the north. But we’ve discovered exactly the opposite. You get off the freeways and into the heart of the heart of the country and time and again you find that all these quaint notions about American cultural life and values are still out there. They’re sometimes under siege, obviously—there’s economic hardship and meth and immigration and other stuff like that. But there are also all these places where you’ll find well-preserved and thriving Main Streets and a boisterous local culture and social life.

In the states we visit, we’re always trying to get away from regional stereotypes—the cowboys, et cetera. But it turns out there’s no escaping them. There have been times when we’ve been trying all day, or even for days at a time, to find a doomsayer or a true crackpot, and we just keep running into these tough, resilient, incredibly open people. It’s corny as hell sometimes, but it’s also sort of inspiring. It’s probably fair to say that we’re both pretty cynical and naturally solitary characters, and neither of us shies away from uncomfortable encounters, but on so many occasions when we’ve steeled ourselves to walk into a situation that from the outside looks like nothing but trouble, we’ve been welcomed with open arms. The only exception to this has come in attempting to penetrate the bastions of the really wealthy. They just won’t let you in, and things can get nasty in a hurry.

What do you mean?

We’ve tried everything, almost literally. We’ve worked contacts with art collectors and people on the boards of museums, made countless calls, cold-called at exclusive clubs and country clubs, tried corporate offices, submitted formal requests. It’s crazy. I guess they’re just very wary of how they might be portrayed—perhaps for good reason—and they’re accustomed to being in complete control. It’s shrewd, really, if frustrating. The resistance has been firm, dismissive, and often hostile.

To your point about the persistence of regionalism, I think we often forget—to use one totally unverified but pretty cool statistic I once heard—that if the entire American population were packed as densely as Brooklyn, we could all fit in New Hampshire. Most American communities are rural, and even those that are close to cities, like the ones you found in Minnesota, still have this incredible resistance to true change.

A sense of place is huge for me, whether I’m reading or looking at photos. I like to have some idea of where I am. Perhaps not surprisingly, the places in this country that have the strongest and most rooted regional identities—the Deep South and the West—tend to have the deepest literary traditions. You can’t visit Mississippi without thinking of Faulkner, Eudora Welty, or Barry Hannah, and they did such an incredible job of describing the place that even on my first trip down there it all felt very familiar to me. In the Midwest you tend to have the classic portraits of suffocating conformity—Sinclair Lewis’s Main Street or Sherwood Anderson’s Winesburg, Ohio, just for instance—and growing up in that world I’m not as drawn to such places, or such books. The West—and particularly Montana—has produced scads of great literature and art, and that’s a place that has always attracted me for that reason—partly for the larger-than-life romance of it, but also because it all still resonates and feels relevant to the current state of things. The Northeast is full of moldering history, too. And the ghosts of Washington Irving and James Fenimore Cooper and Nathaniel Hawthorne seem to be everywhere.

Solitude & Company, Part 5

In our Summer 2003 issue, The Paris Review published Silvana Paternostro’s oral biography of Gabriel García Márquez, which she has recently expanded into a book. In celebration of García Márquez’s life, we’re delighted to present the piece online for the first time—this is the last of five excerpts we’ve run this week. Read the complete text here.

Photo: National Archieef Nederland, via Wikimedia Commons

ROSE STYRON: Somehow, everyone on Martha’s Vineyard seemed to know that he was coming to visit us. Everyone wanted to meet him. Harvey Weinstein, spotting me in Vineyard Haven, hurried over to say, “Please invite me—he’s my favorite author—I’ll sweep the floors.” President Clinton, whom Gabo admired and hoped to talk with, wanted Chelsea to meet him. We decided a large cocktail gathering on our lawn would be prudent, to be followed by a very small seated dinner so the president and Gabo and our Mexican guests, the Carlos Fuenteses and Bernardo Sepulvedas (he was the former foreign minister), could chat in relative quiet. At dinner Gabo’s goddaughter, our friend Patricia Cepeda, translated ably. Our Vineyard neighbors, the Vernon Jordans and the William Luers, and Hillary Clinton completed the table. We all remember that President Clinton’s sweater sported an Elvis crossword puzzle.

WILLIAM STYRON: Although I wasn’t listening closely, I could tell—I have enough Spanish to know—that Gabo and Carlos were engaging him in a talk about the Cuban embargo. They were both at that time passionate about the embargo. Clinton was resisting this conversation, I presume because his mind was already made up. He wasn’t about to be budged even by people that he admired as much as Gabo. So Bill Luers, sitting closer, seeing Clinton’s eyes glaze over, as an ex-diplomat spoke out firmly enough to change the tone of the conversation from politics in Cuba to literary matters. It changed the entire tone at the table. Someone, Bill Luers or perhaps Clinton, asked everyone at the table to give the name of their favorite novel. Clinton’s eyes lit up rather pleasurably. We had a sort of literary parlor game. I recall that Carlos said his favorite novel was Don Quixote. Gabo said The Count of Monte Cristo, and later described why. He said it was the perfect novel. It was spellbinding, not just a costumed melodrama, really a universal masterpiece. I said Huckleberry Finn just off the top of my head. Finally, Clinton said The Sound and the Fury. Immediately, to everyone’s amazement he began to quote verbatim a long, long passage from the book. It was quite spellbinding to see him do that because he then began to give a little interesting lecture on the power of Faulkner and how much Faulkner had influenced him. He then had this kind of two-way conversation with Gabo, in which Gabo said that without Faulkner he would never have been able to write a single word, that Faulkner was his direct inspiration as a writer when he was just beginning to read world literature in Colombia. He made a pilgrimage to Oxford, Mississippi. I remember him mentioning this to Clinton. So the evening was a great success, though a total failure as far as politics went.

GUILLERMO ANGELO: Fame and fortune make people change. You can’t compare the old Gabo with who he is today. Nowadays, he is far more aloof; he doesn’t give of himself the way he used to in the past. Gabo has a strange tendency—he adores power, be it economic power or political power. He loves that kind of thing. Once, [General Omar] Torrijos [former dictator of Panama] told him that he [Gabo] liked dictators and Gabo asked him why. “You’re my friend and Castro’s.”

WILLIAM STYRON: I do think that in many ways there’s an eccentric aspect to Castro, which sets him apart from other dictators. He’s got a fascinating and supple and intricate mind. I think that Gabo is attracted to that part of Castro. I remember this interesting little anecdote that Gabo told me. A very delicate crisis—I forget what—that brought the world’s journalists’ attention to Cuba. Gabo flew in to Havana from, I think, Mexico City. There were hundreds of journalists gathered at the airport. Fidel met Gabo and they walked together into an anteroom in the airport. They were there for half an hour or more while these journalists from all the world’s news agencies were clustered around waiting to see what in this case Gabo had said to Fidel and vice versa. They finally came out and confronted the journalists. The first question, of course, was to Gabo: “Could we ask you what you were talking about just now?” And Gabo answered, “We were talking about the best way to cook red snapper. ”

GUILLERMO ANGULO: Gabo really boasts of the fact that there are nine heads of state that he can call on the phone, and he’s become a friend of Clinton’s.

WILLIAM STYRON: We had an interesting talk about presidents. We both agreed that we were almost fatally attracted to presidents. In his case, in Latin America, these men who have almost always ruthlessly climbed to power have an enormous effect on their fellow men. This is a central aspect of national existence. A man like Castro, the president of Mexico—they hold sway over a whole nation. Therefore they are legitimately people who fascinate writers. I find them fascinating, but the idea that I could in any sense influence him in a major way is a delusion. But this is not true in Latin America.

ENRIQUE SCOPELL: This thing about Gabito is an illness. When Gabo says something, it’s like hearing it from the pope. What do you call it when the pope says something and he’s never wrong? Ex cathedra. That means he can’t be wrong. He can make a mistake when he speaks as a normal man, but not when he speaks ex cathedra.

WILLIAM STYRON: Gabo could not exist in the Anglo-Saxon world. We have no real tradition. It’s not that writers to some degree aren’t respected in this country. They are, but not to the degree they are not only respected but venerated elsewhere. Carlos Fuentes and Octavio Paz had that effect in Mexico. Mario Vargas Llosa was close to becoming president of Peru. Gabo is this sort of phenomenon par excellence. The idea of a writer having such a profound political and cultural influence in the United States like Gabo has in Latin America is inconceivable.

JUANCHO JINETE: I will never forget when Gabito came and stayed at Alvaro’s house, and Juan Gossain—who is the big cheese in Colombian journalism today—was also at the house. Gabo hugged me and said, “These are my childhood friends. ” Then Juan Gossain told Gabito, “Maestro, let me interview you.” Gabito said to him, “What kind of a journalist are you? What more do you want? You have the story right here in your hands. Get it!” It was true—you didn’t have to ask any questions. You know that when journalists start asking questions they ruin the interview—they start to ask a bunch of nonsense that nobody is going to answer truthfully; they tell you the truth that you want to hear—that such and such was a wonderful person, and so on and so forth, all clichés, but none of it is true. Gabito told him, “What more do you want? This is my friend here since we were children. There’s your story.”

Silvana Paternostro is a journalist who has written extensively on Cuba and Central and South America. She is the author of In the Land of God and Man: Confronting Our Sexual Culture and My Colombian War: A Journey Through the Country I Left Behind.

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers