The Paris Review's Blog, page 707

May 9, 2014

Hulk, the Brazilian Outsider

Hulk playing for Brazil at the 2013 FIFA Confederations Cup. Photo: Agência Brasil

The 2014 World Cup, which begins on June 12, is all about Brazil. It is the host country, its team is the favorite, its players and manager are the focus of a huge majority of the two hundred million people who live in the nation and millions more who live outside it. Thirty-one other national teams will be arriving in the country next month, some of them with arguably as good a chance of winning the tournament as Brazil. But until the Selecao—or the Selection, as the Brazilian team is called—gets knocked out of the World Cup, every other team will be a guest in its house.

At nearly every position on the field, Brazil fields some of the best players in the world from the best teams in the world: its star, the forward Neymar, who plays for Barcelona during the club season; its playmaker, Oscar, who plays in London for Chelsea; its defenders Marcelo and Thiago Silva, who play for Real Madrid and Paris Saint-Germain, respectively. The only thing the team doesn’t have this year is a Ronaldo; as the British writer John Lanchester pointed out before the 2006 World Cup, the team then nearly included four of them—“Ronaldao, Ronaldo, Ronaldinho, and Ronaldinhozinho: big Ronald, normal-sized Ronald, small Ronald, and even smaller Ronald.”

In place of all those Ronaldos, though, Brazil has Hulk—its starting right winger, who has a build far different from most any other soccer player in the country, or the world, for that matter. On the pitch, his upper body looks like someone tried to wrap an undersize jersey over a brick house. Hulk plies his trade at Zenit St. Petersburg, in Russia, almost as close as a Brazilian can get to soccer Siberia as the United States. He’s also somewhat removed from the country’s samba school of soccer, a style of play the nation prides itself on and that is commonly referred to as Jogo Bonito, or the Beautiful Game. It’s best represented this year by the creative footwork of Neymar and Oscar, who dodge and dart every which way while maintaining control of the ball as if it were on the long end of a yo-yo attached to their toes instead of their fingers. This isn’t Hulk’s game; his is more the battering ram.

Yet Hulk himself disagrees. “I don’t think my style of playing is different from the classic Brazilian style,” he says over the phone from his apartment in St. Petersburg, with the help of a translator, while his two young boys—Ian, five, and Tiago, three—run riot in the background. “I like to dribble. I like to turn heads with the ball. Maybe only my physical state can make someone wrong about my style of playing.”

“Hulk has technique,” says Juca Kfouri, Brazil’s best-known soccer journalist and a columnist with Folha de S.Paulo, “although it’s unrefined.” Kfouri compares Hulk to the powerful striker Vava, from the World Cup teams of 1958 and 1962. The Brazililan novelist Sergio Rodrigues finds Hulk’s style more reminiscent of Gil, from the 1978 team, who, like Hulk, used to dribble in from the right and fire left-footed cannonballs from a distance. “We do have strong, powerful players in Brazil football,” Rodrigues says. “It’s just that they are usually not the best.”

Or the most popular. “Hulk might walk down the street in Rio de Janeiro and Sao Paulo without being recognized,” Kfouri says. For a man who is nearly six feet tall and two hundred pounds, that would seem hard to do.

Hulk’s hulking statue.

Hulk, whose given name is Givanildo Vieira de Souza, grew up in Campina Grande, a city in the northeastern state of Paraiba, one of the poorer areas of the country, with a severely dry climate. Nearby beaches and the discovery of dinosaur tracks and prehistoric rock carvings draw tourists, yet the area is more known to the rest of Brazil as a place people emigrate from. Hulk did just that, at sixteen, when he moved to Portugal for a year of soccer training. Two years later he landed in Japan, where he helped the club Tokyo Verdy get promoted from the league’s second tier to its first. In 2008, he moved back to Portugal and spent four years with the club FC Porto. The team won the league championship three of those years, and Hulk led it in scoring twice. He was so important to Porto that a statue of him, shirtless, in his trademark-goal celebration pose—an imitation of Lou Ferrigno’s TV Hulk in full flex—now stands in the team’s museum. (Hulk’s father was a fan of the television program, and nicknamed his son after it.)

“That’s the first people ever heard of him in Brazil,” says Rodrigues, whose first novel to be translated in English, Elza: the Girl, will be published this fall, and who will be covering the World Cup for the Brazilian weekly Veja. “It was a bit of, ‘Oh, it’s Portugal. It’s easy to do that in Portugal.’”

When Scolari took over as manager for a second time, in late 2012, Hulk became a fixture in Brazil’s starting lineup, after he’d moved yet again, this time to Russia. Scolari placed him on the right wing, mirroring Neymar on the left, with the injury-riddled striker Fred parked in between them. Scolari seems to like that Hulk’s wrecking-ball moves and powerful left foot give the Brazilian team a second option in the rare instances that Neymar and Oscar’s skilled acrobatics aren’t working.

The fans haven’t necessarily agreed. In a friendly match in Rio de Janeiro prior to last summer’s Confederations Cup, Hulk was booed for taking the place of the more beloved, and technically proficient, homegrown player Lucas Moura, who currently plays for Paris Saint-Germain and didn't make the final cut for this summer's team.

“I went out of Brazil very early, so the people in Brazil didn’t know me well. So they didn’t support me so much,” Hulk says. “I was never intimidated by this because I always knew that I had to go to the field and do my job. But when we had the Confederations Cup last year everything changed, and now it’s the opposite way.”

Indeed, the booing stopped, and when Hulk left the field he was more often applauded than not. Brazil won the tournament—beating the likes of Italy and Spain—and Hulk played well throughout, but he didn’t score. “It’s one of the reasons people feel suspicious,” Rodrigues says. “The Confederations Cup was Neymar’s playground, and Hulk was just one of the sidekicks.”

Brazil hosted the World Cup once before, in 1950, before it had ever won any of its five championships. Its national team breezed its way to the final that year, where it lost in a shocking upset to Uruguay. The country still hasn’t gotten over it. “It’s one of those national traumas,” Rodrigues says. “It’s like the Kennedy assassination. It’s that bad.”

In the years that followed, Nelson Rodrigues, the country’s most respected playwright—who was also a soccer journalist—coined the phrase complexo de vira-lata, or “the mongrel complex,” to define the inferiority issues that plagued the nation following the loss. If Neymar doesn’t shine at this year’s World Cup, Brazilians will count on Hulk to do so instead. But if neither of them do, it will likely mean someone from somewhere else did, and who knows what complex could result from that.

David Gendelman is research editor at Vanity Fair. Follow him on Twitter at @gendelmand.

Acrobats and Mountebanks

This week, Project Gutenberg made available Acrobats and Mountebanks, an 1890 book that explores the circuses, fairs, carnivals, and hippodromes of nineteenth-century France. Written by Hugues Le Roux and Jules Garnier, and translated from the French by A. P. Morton, the book features 233 illustrations of clowns, trainers, tamers, equestrians, equilibrists, acrobats, gymnasts, contortionists, fortune-tellers, dwarves, elephants, carousels, Ferris wheels, and all the trappings of classic mountebankery. It’s worth perusing for the drawings, a selection of which are presented above—but it’s also, after more than a century, still an astonishingly funny read, full of sharp observations and acerbic asides. Here, for instance, is a passage on dwarves:

No one should wonder at the fact that many people are more interested in the abnormal than in the beautiful. But this trait being once recognised, the dwarf is more wonderful than the giant; man is such a complicated machine, that in watching these microscopic creatures who gesticulate and speak like ourselves, we feel something of the same astonishment that would strike us if we found the seconds marked by a miniature watch which we could only see through a magnifying glass. For this reason the dwarf show is one of the most popular booths in the fair.

Every one knows that there are two kinds of dwarfs—those who are naturally dwarfs, and those who, as children, were at first of average size and growth, but whose development was abruptly checked. In their case the limbs which no longer grew, were yet capable of enlargement. As a rule the head is enormous. Monsieur François, from the Cirque Franconi—the partner of Billy Hayden the clown, the tiny circus rider—is a typical specimen of this class of dwarfs, who are called noués to distinguish them from the perfect miniature of humanity. They are physically deformed, but in all other respects they resemble other men. François, for instance, is very intelligent. I shall always remember our first interview two years ago in Erminia Chelli’s box at the Cirque d’Eté.

“How old are you, Monsieur François?”

“Twenty.”

“I am older than you are, M. François; yet, as you know, I am not celebrated.”

M. François shook his head … “You see not every one can be a dwarf.”

And on entering a lion’s cage:

I, who now address you, have entered a black-maned lion’s cage quite recently. Oh! do not exclaim at my heroism …When the beast, who at first grumbled a little, was sitting up and seemed composed again, my companion called to me:

“Come in, now!”

I went in cautiously at the back, taking two steps forward, so that I might still be nearer to the door than to the lion. I must own that the desert king did not honour me by even turning his head. He was talking to his tamer. The two gentlemen left me standing, and I looked rather like a bootmaker waiting for orders from a nobleman.

Man is a coward. The lion’s contempt gave me courage. I advanced a step so that I could touch the leg of the beast.

“Oh!” I said, “how silky it is!”

It was not silky at all, it was abominably harsh.

Since then I have reflected upon the feeling which could have induced me to utter this falsehood, and the result of this self-examination is so humiliating that I will confide it to you as a penance. In fact “how silky it is” was prompted by an instinct of base flattery—a courtier’s compliment—the toadyism of a coward who felt himself nearer to the lion than to the door.

The boldest individuals, who put their heads two or three times a day into the lion’s mouth, have told me that the best way to withdraw it from the gulf is, first of all, not to open the acquaintanceship with this experiment; and, secondly, to perform it with great nerve.

Nerve, that is the great secret of the lion-tamer, the sole cause of his authority over his beasts. When he has studied a subject for some time, endeavouring to master its character—and amongst the higher animals the character is very individual, very accentuated—one morning the man quietly walks into the cage. He must astonish the beast and over-awe him at once. As to the training, it consists—and here I quote the words of an expert in such matters—in commanding the lion to perform the exercises which please him; that is to say, to make him execute from fear of the whip those leaps which he would naturally take in his wild state.

There is one fact which no one would suspect—that it is easier to train an adult lion taken in a snare than an animal born in a menagerie. The lion of the booth is in the same position as sporting dogs which play much with children; they are soon spoilt for work. Pezon possesses five or six lions which he has brought up by hand. As a rule they live with the staff of the menagerie on terms of perfect familiarity, but this frequently leads to tragic accidents.

Lions, even lions in a fair, will devour a man in fine style.

Can I say that the fear of such an accident is ever sufficiently strong to make me pause on the threshold of a menagerie? No. I cherish, and, like me, you also cherish, the hope that some day perhaps we may see a lion-tamer eaten.

And, maybe most fetchingly, on the appeal of carnival food:

Do you remember, my dear friend, the drive we took outside the shows and bands, one fine Easter-Tuesday, brilliant with sunshine? You dared not leave your brougham, you were so alarmed at the hoarse roar of the crowd, the explosion of crackers, the shrieks of the women in the swings. Still you had one great desire that you would not own to me, half dreading a reproof, a wish evoked by a most appetizing odour which made your nostrils dilate.

“I am sure you are longing for some fried potatoes,” I cried triumphantly at last.

Ah! who would ever forget the glance with which your eyes rewarded me for guessing your fancy!

Let’s Hear It for Refrigerators, and Other News

From Life, November 19, 1965. Via the Appendix.

BREAKING: FLAUBERT NOT A REALIST, SAYS EXPERT TESTIMONY

Nathaniel Mackey has won the Ruth Lilley Poetry Prize: a cool $100k. Don Share, editor of Poetry magazine, says, “The poetry of Nathaniel Mackey continues an American bardic line that unfolds from Whitman’s ‘Leaves of Grass’ to H.D.’s ‘Trilogy’ to Olson’s ‘Maximus’ poems, winds through the whole of Robert Duncan’s work and extends beyond all of these. In his poems, but also in his genre-defying serial novel (which has no beginning or end) and in his multifaceted critical writing, Mackey’s words always go where music goes: a brilliant and major accomplishment.”

The rise and fall of the conventional romance novel: “By the seventies, Harlequins became known for their lush language, which often evoked settings that sounded like Thomas Kinkade paintings: ‘The rolling tide of summer grass had engulfed the small meadow in a sweet-smelling flood of lambs’ tails, coltsfoot, feverfew, the drifting pollen from them like pale yellow dust on Linden’s bare arms as she lay full length among them.’” Now self-published erotica, much of it hardcore enough to make your average Harlequin heroine blush, have eaten into sales.

We take our refrigerators for granted, but history reminds of the glories inherent in artificial refrigeration, which used to blow people’s minds.

Google now offers a street view of the Grand Canyon: “On the virtual river you can fast-forward downstream, avoiding the soaking rapids and searing sun, putting in and taking out as you please. But part of the Grand Canyon experience is surrendering to the flow of the river and committing to the journey. Anyone who has traveled in canyon country knows how much the terrain can change in a matter of seconds during an afternoon rainstorm, or in the hours between noon and dusk, as sunlight glistens and fades upon the canyon walls. To these subtle but vital gradations, Google’s roving digital eye remains conspicuously blind.”

May 8, 2014

The Illustrated Walt Whitman

Beautiful/Decay has a striking selection of images from Allen Crawford’s illustrated, hand-lettered new edition of Whitman’s “Song of Myself,” a long poem included in Leaves of Grass. Crawford writes in the introduction,

I’ve tried to make the vigor of “Song of Myself” tangible. I’ve attempted to liberate the words from their blocks of verse, and allow the lines to flow freely about the page, like a stream or a bustling city crowd. The text and imagery in this book are intended to be in keeping with Whitman’s unfurnished sensibility … Whitman’s verse concerns itself with epic sweeps and grand gestures, which means including nearly everything and everyone. Walt did indeed contain multitudes, and I had to follow his lead if I was going to properly serve his words. At times, this could prove exasperating: Keeping up with Whitman’s torrents of people and places sometimes felt like riding a bee-stung bison down the aisle of a bus. I found that in order to add anything at all to Whitman’s panorama of people and places, I had to add a dimension of my own. Events in my daily life affected my approach to each spread, and the Philadelphia of today seeped into the Philadelphia of Whitman’s day. Thus, you’ll find a variety of contemporary or near-contemporary images in this book. Not doing so would have been a disservice to Whitman’s work, which attempts to create a new form of verse for The Here and The Now.

You can see more of his work here.

In Earnest

Albert Edelfelt, Läsande Kvinna (Reading Woman), 1885

“Every time I buy a book here, it changes my life,” the man told me earnestly. He was not the bookseller, but he was minding the stand on Broadway and Seventy-Third Street while the proprietor got a fruit juice from the nearby cart. He clearly wanted to do right by his friend, the owner, in his brief absence, and I was eager to help him. There was not much that appealed to me, but I finally found a hardcover, lavishly praised the interim salesman to the returned proprietor, and handed him the five-dollar bill that would, he remarked, cover the cost of the mango drink he was now sipping.

I did not really think that The Lifestyles of the Rich and Famous Cookbook (1992) would change my life. If I’d thought more about it, I might have hoped to share the book with a few likeminded friends, where we’d marvel at the dated food styling and speculate about the quality of “Liza’s Salade de Provence,” which involves corn, raw mushrooms, pink grapefruit, and hearts of palm. In short, I guess you could say what interest I had was ironic.

But then I sat down at home and opened it, and I was reading it, and the act of reading—the process of assimilating letters and sounds and translating that into meaning—is not ironic, is it? In fact, in the absence of other people, there isn’t much irony at all. I might have tweeted something about Joan Collins’s menu planning—“Extravagance is the only way when it comes to buying beautiful dresses and to making salads”—or shared a picture of the “Smoked Salmon Bruschetta” that was allegedly a specialty of Elle Macpherson’s. But instead, I just read, and thought, and maybe smiled a little at some things, but not at anyone’s expense. We were in it together.

There is nothing left to say about irony, really. Nothing that hasn’t been said before, and better. Not after David Foster Wallace, not after the last twenty years. A recent Fast Company article went so far as to suggest that irony fatigue is propelling, in part, new “sadvertising” trends, designed to tug at viewers’ heartstrings rather than—well, I can’t say “funny bones.”

Anyone who has been a teenager knows that negativity and its derivatives are a certain kind of social glue. Powerful, potentially intoxicating, and, to overextend the metaphor, noxious when abused. Conversely, maybe solitude kills irony; there is certainly nothing more truly earnest. I’m not even sure we can be funny when alone—not without, at least, some distanced part of ourselves as audience.

I will surely show my cookbook to people, and maybe we’ll even do a themed meal of Valentino’s risotto, and the “Banana Soft ‘Tacos’” served by Texas hostess Caroline Hunt to visiting royalty. But secretly I will feel bad about it, because I will know that when I read about Dame Barbara Cartland’s pink-hued ninetieth birthday party, it was without any mockery, and that when she said, “anything to do with love makes me happy,” it was hard to second-guess.

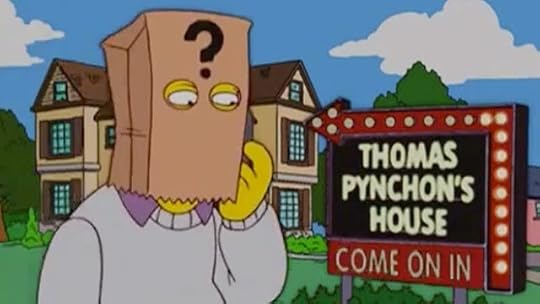

Watch: The Greta Garbo of American Letters

A still from Pynchon’s “appearance” on The Simpsons, for which he lent his voice.

Today is Thomas Pynchon’s birthday. His fans have also declared it Pynchon in Public Day, a social-media tribute with a modest concept: take to the streets with your camera and post photos of “horns, W.A.S.T.E. insignia, [and] the novels of Thomas Pynchon read unashamedly on trains, while still sub-rosa. It is simple, it is inevitable, it has begun.”

And so it has: Twitter teems with shadowy portraits of those Awaiting Silent Trystero’s Empire. If you’re not about to draw a muted post-horn in a public restroom, you can celebrate Pynchon in Public Day by revisiting this CNN report from 1997, when, upon the release of Mason & Dixon, the cable-news pooh-bahs determined to track him down—his privacy was simply too inscrutable to ignore. Being CNN, they found him, but he prevailed upon them to refrain from identifying him on camera; he appeared as one among the crowds of New York.

The report is an engaging look at Pynchon’s media hijinks over the years. Its newsy, wide-eyed tone dates it to those strange days before the Internet’s hegemony, when it was easier to play games with one’s identity. “Many of his fans don’t even know what he looks like!” the anchor, Joie Chen, says, her brow knit in befuddlement: Just what sort of a crank is this guy? (Look out, too, for John Larroquette mispronouncing oblique.)

The text edition of the piece claims that “Pynchon’s oh-so-low profile has earned him the sobriquet as the Greta Garbo of American letters”—not a phrase I’d heard before, but one I’ll begin to deploy posthaste.

“While Pynchon’s books can be found side by side with other works of popular fiction, you won’t find Pynchon the author anywhere,” the reporter explains, as if we might have expected to spy him lurking behind the shelves at Barnes & Noble. And perhaps he’s there—I haven’t checked. Wherever he is, I hope he’s celebrating his special day with cherry-quinine petit fours, eucalyptus-flavored fondant, and pepsin-flavored nougat.

Clitics

Life in the linguistics lab.

Image via Giphy

In August 2009, I took a job as a “confederate” at the “MIXER” project, run by the linguistics lab of a university in the Philadelphia area. The goal of the MIXER project was to gather recorded interviews for a database of conversational American speech. Over the previous five years, the lab had recorded thousands of speakers; having secured a grant from an undisclosed sponsor, they were gearing up for another year. For three hundred dollars a week, my only responsibility was to receive the participants that came to the lab and to get them to speak.

The interviews were conducted in a recording booth known as the Mermaid Lounge, so named for the amphibian girl and paint-by-numbers fish characters painted on the far wall. Inside the Lounge was a single desk where two computer monitors sat head-to-head, surrounded by cameras and all kinds of microphones: clip-ons, standalones, condensers. At the other end of the hallway was the HIVE, a seminar room that served as base of operations for the MIXER-6 team—me, a secretary, and the lead confederate, who liaised with the sponsors. The lead confederate on MIXER-6 had participated in every study so far except MIXER-4, which she’d missed due to dental surgery. Now, after several complicated adjustments, she wore an elaborate dental fixture that rendered her effectively mute. She typically relayed messages through the secretary, Stabler, a burly little man with golden-blond hair and a bushy beard. Stabler was responsible for outreach; that meant flyering, Craigslist ads, and organizing participant data. Unfortunately, he was hamstrung by his terrible stammer, which was particularly pronounced whenever he spoke on the phone: “Hello, thank you for c-c-calling the l-l-ab … Are you r-r-responding to the a-a-ad?”

As a confederate, my responsibilities consisted of escorting the participants to the Mermaid Lounge, fitting them with a small, sensitive mic, and seeing them through three “sessions.” The first, the Prompt Session, was scripted. Participants read through a series of warm-up phrases as they scrolled across a monitor. These were mostly binomials like riff raff, hip-hop, flim flam, willy nilly, etc. Once the articulatory mechanisms were sufficiently exercised, I moved onto the Natural Session, during which I conversed with the participant on a topic of his or her choice. If necessary, we could discuss the algorithmically generated topic of the day, which might be Netflix, or terrorism, or gun control. Finally, after fifteen minutes, the participant put on a pair of headphones for the Noisy Session. An automated voiced counted down to zero, and then a steady stream of white noise came through the soft earpieces while I continued to converse with the participant.

Because the study offered the participants three hundred dollars without requiring them to ingest any disruptive substances, the schedule filled quickly. The respondents fell into three groups: recent college graduates, retired Philadelphians, and veterans from a nearby recovery center. Sessions with the graduates were more or less indistinguishable from the conversations I would have with my friends after work—and that made me uncomfortable. I found myself more at ease with the retirees, who were so grateful for a break from the drudgery of retired life that the fifteen minutes were quickly filled with enthusiastic monologue. One of the first participants, Tutu S., a former high school principal dressed all in cranberry—cranberry corduroys, a cranberry-striped collar visible beneath a cranberry sweater—chattered about the topic of the day (gun control) without so much as pausing for breath. Another retiree, Alex K., arrived at the lab in camping gear, dragging several tote bags behind him. “Oh, oh, what an interesting opportunity this is!” he sighed. The fluorescent light of the Mermaid Lounge reflected on his bald head. Standing in the door of the HIVE, he kept telling us what an interesting topic we had chosen. Eventually, the lead confederate escorted him out.

Of course, not every session went so smoothly. Jonathan C., another early participant, blocked every attempt at natural conversation. He read through the prompts with all the petulance of a child put on time-out. “Hee-haw, hurdy gurdy, hoosie-whatsit,” he pouted. His sheepish, confession-booth eyes scanned across the monitor. I noticed that there was a perfectly oval birthmark right in the center of his forehead.

“What do you do?” I asked.

“I’m an attendant at a fur coat storage facility,” he replied.

I grasped for a segue: “What’s the temperature like in that storage facility?”

“It depends.” He paused. “It depends on the coat.”

Thankfully, Jonathan became more candid during the Noisy Session. As soon as he heard the hiss in the headphones, he began to yell out unprompted: “BECAUSE MY FATHER IS A FAILURE … BECAUSE HE GAVE ME A BAD EMOTIONAL BLUEPRINT! … ” while the staff at the HIVE looked in on the session impassively, ticking off notes on a clipboard.

Far and away the most courteous—if not necessarily the most forthcoming—participants were the veterans. Recruited from two recovery centers in North Philadelphia, they had heard that the study was funded by the Department of Defense, so many of them would frame their participation in terms of responsibility and duty. “We like to help out when we can,” one participant explained to me. Another, Rachel S., imagined that the study would be more formal than it was. Seeing me in the doorway of the HIVE, she burst out laughing. “I thought you’d be some Pentagon guy,” she explained.

A tall, fit man named Oscar M., who limped into the Mermaid Lounge with a brace on his leg, told me that, before the service, he worked as a window cleaner on the skyscrapers in the financial district. Looking through the lounge’s picture window, which looked out onto Center City, he named every building in the skyline. According to Oscar, the daytime head on the Cira Center was so intense the cleaners couldn’t work past ten A.M. When the Noisy Session began, he began to reminisce about his time in the service. He told me about how he finally earned “Shellback Status.” When I said I had no idea what that was, he flashed a nostalgic smile. As his ears flooded with white noise, he described to me the hazing process he had endured. “MAKE YOU SWIM THROUGH GARBAGE, OIL, SPIT ON YOU, PISS ON YOU,” he shouted, trying to make himself heard over the noise. “JUST KEEP SWIMMIN’!” The hiss cut out, signaling the end of the session.

Afterward, I told the lead confederate that it was “interesting” to have so many retirees in the study. “Oh, good!” she said, or tried to say, hindered by her shiny green braces. “I’m glad they’re signing up because a lot of them fit the target demographic.”

“What demographic?” I asked.

There was a loud snap; she clapped her hand to her mouth. Something was wrong with her braces. After standing for a moment, her face twisted into an expression of bewilderment and discomfort, she picked up a pen, scratched something on a Post-It note, and handed it to Stabler.

“Th-the sp-sponsor d-d-doesn’t want y-y-you to kn-know,” he read aloud.

My final participant, Sinclair O., had signed up at the beginning of the study, but he had had to cancel because, as he explained, a trolley had run over his foot. Beneath his large sunglasses, I noticed a cluster of red pimples around his nose and mouth. His whole affect was one of profound irritation.

“Name?” I asked.

“Don’t you already know?” he snapped.

“It’s only a preliminary question,” I said. I saw my reflection in his glasses, sitting behind my monitor, the open window glaring behind me.

Sinclair’s annoyance only deepened during the binary prompts. “Flim-flam, riff raff, hoosie whatsit,” he shook his head. “What is this?” I wasn’t sure how to explain. He laughed nervously. “What are you doin’ with this?” he asked. “Now, now—are you gonna discredit me?”

“Trust me, this isn’t a test,” I assured him. I rushed through the prompts to reach the Natural Session sooner, but that went no better.

“So you’re from Philly?” I asked.

He furrowed his brow, just above the rim of his aviators. “I’m definitely not from Philly,” he said sharply. “I came here just to see my brother. Here I am one year later, tryin’ to go back to Oakland.”

I tried to change the subject. “How’d you find out about the study?”

“Because I’m tryin’ to get out!” he snapped again. “Enough of this place. It’s all the same here, man. People, they can move to Germantown, but it’s the same shit—you just in Germantown now. People think they can move to South Philly, and it’s the same shit—now you in South Philly.” He worked his way through the map of Philadelphia until, all of a sudden, he pointed at his nose. “Man, see this?! I don’t get this shit when I’m in Oakland. This shit on my face is because of Philadelphia.”

When the white noise began for the Noise Session, Sinclair immediately pulled off the headphones. “No way,” he said. “Not doin’ that.” This was the first time a participant reacted negatively to the noise. “How ’bout you man?” he asked. “Why you workin’ here?”

“I applied for the job,” I answered weakly.

“Why here, though—I mean, who are you?” He rubbed the clip-on mic between his fingers.

“Well,” I said, trying to remember, “one of the lead linguists here offered me a job. I met him when I worked at a coffee shop.” This was Mark M., who walked around with an ostentatious-looking African cane and tied his stringy white hair together with a headband. “I was reading this book about linguistics and I wrote a word—”

“What word?” Sinclair interrupted.

At this coffee shop, Mark M. had spotted my notebook, where I had written down the word clitics. “Do you know what clitics are?” he’d asked me. I didn’t, and still don’t.

“I don’t remember what word,” I told Sinclair.

The headphones went silent, so we returned to the HIVE in order to sign release forms. Sinclair continued to press me.

“I mean, really, what’s this for?”

“Speech recognition,” I explained. This was the response we had been trained to give. “They’re trying to improve speech recognition.” Sinclair’s face twisted with suspicion. “Listen, I can delete it,” I offered, “but then you won’t get paid.”

“Well,” he countered, “you can say you’re going to delete it, but you might really be saving it somewhere.”

“No, really, I can show you.” I retrieved the microphone on which the conversation had been recorded and showed Sinclair the trashbin icon on the microphone’s interface. Admittedly, it looked dubious.

“It can say it’s deleting it,” Sinclair went on, “but it could really be sending it off somewhere and savin’ it for later!”

For a moment, I worried that Sinclair was going to rip the microphone from my hand and smash it on the ground. Instead, he took the confirmation papers from me and calmly signed them. His signature authorized the recording to be used for “any future research.” Below his signature, he added, in florid script: “Remember, be nice!”

Timothy Leonido is a writer based in Philadelphia. Other work can be found in Gauss PDF, and is forthcoming in Triple Canopy and Lateral Addition.

These Big Eyes Are Lies, and Other News

Margaret Keane, Big Eyes

Putin has signed a law banning foul language in plays and movies; any books with cuss words will come in sealed packages, with warnings. Which words qualify as uncouth? A panel of “independent experts” is soon to convene in pursuit of that very fucking question.

Meanwhile, in America and the UK, an unexpurgated edition of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s Taps at Reveille—its expletives intact; its sex, drugs, and anti-Semitic slurs restored—will arrive next month.

Long before the heyday of Lisa Frank, there was the pop artist Walter Keane, who became something of a household name in the sixties: his work depicted sad children with enormous, farcically melancholy eyes. But his wife Margaret deserved all the credit: “The man wasn’t a painter at all. Margaret was the creator of all the Big Eye art. Walter basked in the glory, partied with the celebrities, and reaped the rewards. As she would later relate, the tearful, doe-eyed children she painted had nothing to do with Walter’s supposed belief in children redeeming the world. The weeping waifs reflected her own sorrow.”

Revising the myth of Phineas Gage, who survived, in the late nineteenth century, an accident in which an iron rod went straight through his head, and who has been fodder for Psych 101 students ever since. “Recent historical work, however, suggests that much of the canonical Gage story is hogwash, a mélange of scientific prejudice, artistic license, and outright fabrication. In truth each generation seems to remake Gage in its own image, and we know very few hard facts about his post-accident life and behavior.”

“How do you design cities and civic spaces in ways that account for people’s varied reactions to sound itself? Where does ‘sound’ end, and ‘noise’ begin?”

May 7, 2014

Archibald MacLeish, Librarian of Congress

Archibald MacLeish in 1944. Photo via Wikimedia Commons

Today brought welcome news that the New York Public Library has abandoned its plan to “renovate” (i.e., reduce and/or ruin) its research flagship at Bryant Park, on 42nd Street. The renovation would have meant removing the stacks beneath the main reading room, thus displacing an untold number of books and research materials; the plan met with derision among scholars and authors, and a piece in the Times last year by Michael Kimmelman made an elegant case against it.

And wouldn’t you know it—today is also Archibald MacLeish’s birthday. His 1974 Art of Poetry interview is great reading, but given the news of the day, and given his role as the Librarian of Congress—a position he held from 1939 to 1944—it seems fitting to peruse his 1940 essay, “The Librarian and the Democratic Process,” which addresses … well, not many of the same issues at stake in the NYPL’s renovation controversy. It was 1940; the world was on the brink of war, and digitization was not a going concern for librarians. But the piece does find MacLeish asking, in a sweeping, stentorian tone: What is a librarian supposed to do, anyway?

Mr. Andrew Carnegie is cited as holding the opinion that the purpose of a library is to “improve the masses. “Mr. Henry E. Legler supplies the view that the purpose of a library is to “furnish the ambitious artisan with an opportunity to rise.” Mr. F. A. Hutchins is authority of the proposition that the purpose of a library is to give “wholesome employment to all classes for those idle hours which wreck more lives than any other cause.” It is at least doubtful to my mind whether librarians would accept these descriptions of their usefulness today … To provide harmless recreation in competition with the street and the saloon is not a profession: if it were, Hollywood would be a profession from producers and directors down to ticket takers and ushers in plum-covered regimentals. To give wholesome employment for those idle hours which wreck the young is not a profession … definitions such as these taken together with the contemporary state of mind would seem to establish the fact that no generally accepted or acceptable definition of the function of librarianship has yet been found.

Oh, for the forties, when Hollywood was prima-facie valueless and a good bit of rhetorical puffery—the bloat of “no generally accepted or acceptable definition of the function of” would never fly today—was par for the course. Still, as the NYPL dispute attests, MacLeish’s central question remains a good one. What we expect from our libraries remains unclear.

In the seventies, MacLeish wrote more about his library philosophy in “The Premise of Meaning,” which he originally published in The American Scholar, and which the Scholar, in a rather unscholarly turn, doesn’t even mention online, let alone reproduce. A library, he wrote,

is an extraordinary thing … It is not a sort of scholarly filling station where students of all ages can repair to get themselves supplied with a tankful of titles … On the contrary it is an achievement in and of itself—one of the greatest of human achievements because it combines and justifies so many others … But what is more important in a library than anything else … is the fact that it exists. For the existence of a library, the fact of its existence, is, in itself and of itself, an assertion—a proposition nailed like Luther’s to the door of time. By standing where it does … at the center of our intellectual lives—with its books in a certain order on its shelves and its cards in a certain structure in their cases, the true library asserts that there is indeed a “mystery of things.” Or, more precisely, it asserts that the reason why the “things” compose a mystery is that they seem to mean, that they fall, when gathered together, into a kind of relationship, of wholeness, as though all these different and dissimilar reports, these bits and pieces of experience, manuscripts in bottles, messages from long before, from deep within, from miles beyond, belonged together and might, if understood together, spell out the meaning which the mystery implies.

Big in 2014

Stefan Zweig in 1900.

Last night, I attended a talk at the New York Public Library between Paul Holdengräber and George Prochnik, the author of The Impossible Exile: Stefan Zweig at the End of the World. Three different publishers were involved; the room was packed and attentive. In the mysterious way of such things, Stefan Zweig is, after some sixty years of obscurity in the United States, having A Moment. Wes Anderson helps, of course; Grand Budapest Hotel was a tribute to Zweig’s work, and is the cause of much of the renewed interest. But that someone like Zweig—once the toast of the international literati—came to Anderson’s attention in the first place shows signs of the mysterious forces that create such ebbs and flows. What makes a trend? Maybe it has a bit to do with something Prochnik said last night: no one can engage in the work of biography without at least some belief in ghosts.

Spiritualism aside, I am told that the trends for 2014 encompass everything: chocolate-chip-cookie milk-shots, dressing like superheroes, indie crossover R&B. There seem to be a great many cozy dystopias appearing in films. I won’t even speculate on apps. Or exercise.

I can’t tell you why these things have found such popularity. Certainly, I can tell you anecdotally that all of a sudden everyone seems to be reading Stoner, by John Williams. We appreciate good weather as we never have, but we are wary of being made fools of. It is hard to buy clothing, even cheap clothing, without filtering everything through something intellectual. It is okay to talk about insurance, sometimes. I don’t know if it is a product of these ghostly forces, but for the first time in my life I have felt an irresistible urge to drink sidecars. All I know is that in order for these things to take any kind of hold, they must feel like revelations to someone, if only for a moment, before they pretend that they knew all along and then have to reject it as obvious. Is that occult?

Zweig is the rare case that allows for real debate about the nature of his Moment. As Clive James put it,

Largely because of his highly schooled but apparently effortless gift for a clear prose narrative, he attained, while he lived, immense popularity not just in the German-speaking countries but in the world entire, and he is still paying the penalty for it. Except in France, where his major works are never out of print, it is usually safer to call him second-rate. Safer, but not sound.

But when is the instinct to self-protection ever really sound? Or, for that matter, unsound? It is the most universal and perennial of trends, maybe. Zweig himself wrote, “Never can the innate power of a work be hidden or locked away. A work of art can be forgotten by time; it can be forbidden and rejected but the elemental will always prevail over the ephemeral.” But surely to keep company with the ephemeral—in perpetuity—is the greatest triumph of all, no? That’s what ghosts do.

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers