The Paris Review's Blog, page 714

April 21, 2014

Sleep of Reason

Volkov, Tatiana Larina’s Dream, 1891

When Edith M. Thomas wrote “Talking in Their Sleep” in 1885, she was already regarded as one of America’s foremost poets. Well into the last century, her poems were part of the canon—and this one, in particular, was a common inclusion in grade-school readers, memorized and recited by generations of students.

If you look at the 1919 textbook Wheeler’s Graded Literary Readers, with Interpretations, you’ll find “Talking in Their Sleep” presented as a straightforward story of plants and trees sleeping through the winter: “In the spring, just as boys and girls awake in the morning, they will awake again.” As a child, I found the poem terrifying. That something should seem dead when sleeping was scary enough; that the seeming-dead should also speak only made it worse. But then, sleep-talking has always frightened me.

You see, by day, I am caution personified. The self-designated peacemaker in a volatile family, I have always seen words as potentially lethal things to be managed with care and forethought. I rarely speak without considering what I say—will it offend someone? Anger them? Sound foolish? And I am morbidly self-conscious about my speaking voice; even into my thirties, I am regularly mistaken for a child on the telephone, which I avoid using with even my closest friends. Given these sensitivities, it has always struck me as both cruel and somehow fitting that my worst nightmare should come true on an almost nightly basis.

“I talk in my sleep,” I’ll tell someone nervously if I know we are to share a room, and the person will laugh—but no one has ever known what’s to come. Even I don’t, exactly, though I’m told my late-night soundtracks encompass everything from singing to screaming to fully intelligible monologues.

Anyone who hears such things is understandably alarmed—listeners will usually rouse me from what they assume to be a horrible night terror brought on by the buried memory of some early trauma. But in fact, my dreams are deadly dull. More often than not, when awoken, I’ll be in the midst of debating someone about a book, or a recipe, or arguing over the best place to buy a terry-cloth bathrobe. I just do it all at top volume. All the quotidian situations, I guess, in which I constantly, exhaustingly, needlessly police my words and thoughts.

Somniloquy affects 4 percent of adults. According to Wikipedia, “depending on its frequency, it may or may not be considered pathological.” I suspect mine might be pathological. In any case, those who love me are counseled to wear earplugs.

“You think I am dead,”

The apple tree said,

“Because I have never a leaf to show–

Because I stoop,

And my branches droop,

And the dull gray mosses over me grow!

But I’m still alive in trunk and shoot;

The buds of next May

I fold away–

But I pity the withered grass at my root.”

“You think I am dead,”

The quick grass said,

“Because I have parted with stem and blade!

But under the ground

I am safe and sound

With the snow’s thick blanket over me laid.

I’m all alive, and ready to shoot,

Should the spring of the year

Come dancing here–

But I pity the flower without branch or root.”

“You think I am dead,”

A soft voice said,

“Because not a branch or root I own.

I never have died,

But close I hide

In a plumy seed that the wind has sown.

Patient I wait through the long winter hours;

You will see me again–

I shall laugh at you then,

Out of the eyes of a hundred flowers.”

Recapping Dante: Canto 26, or You Can’t Go Home Again

Alessandro Allori, Odysseus Questions the Seer Tiresias, 1580

We’re recapping the Inferno. Read along! This week: tales of brave Ulysses.

Wrapped in a shroud of fire, sputtering words from the tip of the flickering flame—this is how Ulysses appears to us in canto 26. As Dante approaches the eighth pouch of the Eighth Circle of Hell, he sees sinners in flames; he knows he’ll find Ulysses among these “fireflies that glimmer in the valley.” The man is tied up in a flame with Diomed, both of them being punished for their ruse at Troy. Dante begs Virgil to let Ulysses speak.

When we finally put down the Inferno, Ulysses is one of the sinners we remember best. Not because he’s well known or the architect of one of the greatest schemes in history, but because, like Pier or Francesca, there’s charm, tenderness, and beauty in the way he speaks. On this point, I disagree with Robert Hollander, whose annotations explain that these aforementioned sinners are not meant to be entirely sympathetic—they’re actually self-righteous, Hollander writes, and they’re unable to see the gravity of their sins. By allowing them to speak in a manner that almost absolves them, Dante is even poking fun at them.

Dante may have been an ironist, too, but above all, he was a poet, as canto 26 proves. Here we have a Ulysses who finally returned to Ithaca and yet could not abandon adventure. He loved his wife and son and father and his home, but his heart remained tethered to the unknown. Dante’s Ulysses longed to see more. After years of travel, he and his men reached the rim of the earth, end of the world—legend foretold that any adventurer who went beyond that point would be killed. Ulysses kept going, and his ship was destroyed.

C.P. Cavafy, an early twentieth-century Greek poet, also wrote about Ulysses’s lust for adventure in his poem “Ithaca”:

As you set out for Ithaka

hope the voyage is a long one,

full of adventure, full of discovery.

Laistrygonians and Cyclops,

angry Poseidon—don’t be afraid of them:

you’ll never find things like that on your way

as long as you keep your thoughts raised high,

as long as a rare excitement

stirs your spirit and your body.

Laistrygonians and Cyclops,

wild Poseidon—you won’t encounter them

unless you bring them along inside your soul,

unless your soul sets them up in front of you.

Hope the voyage is a long one.

May there be many a summer morning when,

with what pleasure, what joy,

you come into harbors seen for the first time;

may you stop at Phoenician trading stations

to buy fine things,

mother of pearl and coral, amber and ebony,

sensual perfume of every kind—

as many sensual perfumes as you can;

and may you visit many Egyptian cities

to gather stores of knowledge from their scholars.

Keep Ithaka always in your mind.

Arriving there is what you are destined for.

But do not hurry the journey at all.

Better if it lasts for years,

so you are old by the time you reach the island,

wealthy with all you have gained on the way,

not expecting Ithaka to make you rich.

Ithaka gave you the marvelous journey.

Without her you would not have set out.

She has nothing left to give you now.

And if you find her poor, Ithaka won’t have fooled you.

Wise as you will have become,so full of experience,

you will have understood by then what these Ithakas mean.

Cavafy tells Ulysses not to rush. Ithaca is home, but it isn’t; its real gift is that it isn’t where we are now—and every waypoint and every island that stands before Ithaca is part of what Ithaca has to offer. Dante’s Ulysses arrived home too soon, and asked too much of the tiny Greek isle. Dissatisfied, he took off again. Ithaca is a purpose but not a goal—Dante’s Ulysses lost his Ithaca when he arrived in Ithaca. The difference between Cavafy and Dante is that the former is speaking to a still-wandering hero, and the latter writes as a Ulysses who had already set off a second time.

Reading Cavafy beside Dante’s text is tragic—in this light, Cavafy’s poem is no longer a piece of advice, but a lament and a cautionary tale. We, too, may one day despair upon reaching Ithaca. What if, like Ulysses, we spent far too little time at sea, and we finally arrive at Ithaca only to find it has nothing left to offer?

A Nation of Postcards, and Other News

Image: Boston Public Library

On that ever-mysterious rubric, “literary fiction”: “It was clever marketing by publishers to set certain contemporary fiction apart and declare it Literature—and therefore Important, Art, and somehow better than other writing … Jane Austen’s works are described as literary fiction. This is nonsense … Austen never for a moment imagined she was writing Literature. Posterity decided that—not her, not John Murray, not even her contemporary readership. She wrote fiction, to entertain and to make money.”

The French economist Thomas Piketty has alighted upon our shores, “like a wonkish heir to de Tocqueville, to tell Americans how to salvage what he called their ‘egalitarian pioneer ideal’ from a potentially devastating ‘drift toward oligarchy.’”

A salve for irritated prescriptivists: this new browser extension literally replaces every instance of literally with figuratively, all over the Internet.

Gillette’s new razor does violence to the spirit of entrepreneurship: “It’s a men’s razor that does what every other men’s razor since time immemorial has done—removes hair from your face—but with ‘a swiveling ball-hinge’ that the company says will make it easier to get a clean shave … The razor represents everything terrible about America’s innovation economy.”

Online, the Boston Public Library has more than 25,000 U.S. postcards from the thirties and forties, all of them vividly illustrated.

April 18, 2014

What We’re Loving: Good Friday Riffs, Your New White Hair

Samuel Johnson’s portrait by James Barry.

It took me twenty-five years to read Jane Eyre. The first twenty-four and three quarters were tough going—I almost never made it past the death of the annoying Christian schoolmate. Rochester drove me up the wall; so did passive-aggressive Jane. Then a couple of months ago a friend gave me a beat-up old pocketbook edition. This time it took. When I realized a couple of pages were missing, I read them on my phone. When the paperback got lost in the coatroom at Café Loup, I started taking my iPad to bed (a reluctant first). When the same friend presented me with a Folio edition giveaway, weighing sixteen pounds (with regrettable illustrations), I took it everywhere, in case I had half an hour alone. I was warned that things go downhill after you-know-who appears in the night and tears Jane’s you-know-what. Not for me. The weirder the subplot, the more Jane tightened her grip. What had changed? Maybe certain writers—Norman Rush, Defoe, Dickens, Melville, Hawthorne—or maybe just reading in general had taught me that dialogue can come in weird shapes, not just tit-for-tat, and that soliloquies can happen on the page. Maybe I’ve just gotten to know more women, like Jane, who live at war with themselves, and maybe the freakiness of wanting and hating to be bossed around makes more sense to me now. The whole time, I kept thinking, So many girls read this when they’re kids—and get it. How could it take so long to catch up? —Lorin Stein

Reading a László Krasznahorkai novel is a major commitment, and the kind I’m willing to make, but I haven’t had the time lately to devote myself to it. I’ve made do with the London Review of Books’ recent story “There Goes Valzer.” A man named Róbert Valzer who likes walking (“not that I have anything do to with the famous Robert Walser”) takes an aimless stroll on the Day of the Dead in his La Sportiva boots, through cemeteries and out to the edge of town. Because of its brevity and relatively short sentences, the story offers an opportunity to better appreciate Krasznahorkai’s sly humor, often camouflaged by his melancholic themes. Not that there isn’t disillusionment here, but it’s tempered by a ready absurdity: “I hate Michaelmas daisies and, I must confess, I am not too keen on people either, in fact you might say I hate people too, or, better still, that I hate people as much as I hate Michaelmas daisies and that is simply because every time I see Michaelmas daisies they remind me of people rather than of Michaelmas daisies, and every time I see people I always think of Michaelmas daisies not of people.” (Yes, that is a short sentence—for Krasznahorkai.) —Nicole Rudick

This unending winter—and the moods that have come with it—has reminded many Americans, brutally, of the effect the environment has on our psyches. It’s a theme I haven't encountered in a work of American fiction in recent memory, though I wonder, with our rapidly changing earth, if we’ll begin to see it reflected more in our country's creative output. The seasons and their regularities, their whims have figured prominently in Japanese art for many centuries, though, and Takashi Hiraide's The Guest Cat, recently translated by Eric Selland, is a new cornerstone in this tradition. A short novel about little more than the comings and goings of a neighborhood cat around the grounds and home of a childless couple, the swells and lags in the emotional narrative of the book are propelled by a rising temperature, a blooming flower, a drooping tree. It’s reassuring to feel that perhaps a close tie between one's mental state and the weather may be, in fact, quite natural. —Clare Fentress

Boswell’s The Life of Samuel Johnson is a bit like Nigel Slater’s Kitchen Diaries: there’s an entry for almost every season, holiday, or time of the year. Reading Boswell’s Life, it’s hard not to think of it at times as a practical joke; Boswell’s silliness is the great enigma of this book. Just to see what he would say, Boswell would ask Johnson questions like “What would you do if you were locked in a tower with a newborn baby?” The entry for Good Friday, 1778, contains so much: a discussion of literary aestheticism and didacticism, of the usefulness that literature can have to society, of the etiquette of making small talk. And it’s full of the usual yuks from the Boswell-Johnson buddy act:

Johnson: “Sir, it would have been better that I had been of a profession. I ought to have been a lawyer.”

Boswell: “I do not think, Sir, it would have been better, for we should not have had the English dictionary.”

Johnson: “But you would have had reports.” —Anna Heyward

I remember the first time I watched The Shining. My hands covered my eyes through half of the film: I saw a flash of room 237, a rotting corpse embracing Jack Nicholson, a flood of blood. “Here’s Johnny!” echoed through my basement. While I didn’t fully comprehend Kubrick’s handiwork at the time, I recognized there was more to the film than its horror/ghost story surface would have you believe. The Native American burial ground (genocide?); the furniture appearing and disappearing (ghosts, madness?); the photo of the July 4th Ball that closes the film (American imperialism?). What a relief it was to watch Rodney Ascher’s documentary Room 237 and realize I was not alone! It’s easy to dismiss many of the ideas here as over-analysis or conspiracy theories—watching the film forward and backward at the same time is my favorite. One theory contends that Kubrick directed the Apollo 11 moon landing. But there’s something beautiful in a documentary about people going crazy over a film about people going crazy. I think the documentary’s assistant editor, Gordon Stainforth, sufficiently got across my thoughts on the film: “The sum of what we learn refuses to add up neatly.” —Justin Alvarez

In the wake of this week’s ferry accident in South Korea—an accident that’s offering no end of tragedy—I came across a harrowing article on the foundering of the Estonia in September 1994. Proceed with caution—it’s almost mathematical in its recounting of the chaos and disorientation of maritime disaster: “Survival that night was a very tight race, and savagely simple. People who started early and moved fast had some chance of winning. People who started late or hesitated for any reason had no chance at all. Action paid. Contemplation did not.” —Stephen Hiltner

I recently had a dream where all my friends had gone gray. They weren’t any different besides that, though everybody was behaving a bit differently, or trying to figure out if they were supposed to behave differently. I think I dreamed this because I read Eileen Myles’s poem “Peanut Butter” a year ago, where she writes, “I’m immoderately in love with you, knocked out by your new white hair.” I saved that line in a notebook I just filled, so I saw it again and read the poem again. I still like it, but I’m inaugurating my new one with “During my life I was a woman with hazel eyes,” because it’s weird, and I’ll want it again next winter. —Zack Newick

What We‘re Loving: Good Friday Riffs, Your New White Hair

Samuel Johnson’s portrait by James Barry.

It took me twenty-five years to read Jane Eyre. The first twenty-four and three quarters were tough going—I almost never made it past the death of the annoying Christian schoolmate. Rochester drove me up the wall; so did passive-aggressive Jane. Then a couple of months ago a friend gave me a beat-up old pocketbook edition. This time it took. When I realized a couple of pages were missing, I read them on my phone. When the paperback got lost in the coatroom at Café Loup, I started taking my iPad to bed (a reluctant first). When the same friend presented me with a Folio edition giveaway, weighing sixteen pounds (with regrettable illustrations), I took it everywhere, in case I had half an hour alone. I was warned that things go downhill after you-know-who appears in the night and tears Jane’s you-know-what. Not for me. The weirder the subplot, the more Jane tightened her grip. What had changed? Maybe certain writers—Norman Rush, Defoe, Dickens, Melville, Hawthorne—or maybe just reading in general had taught me that dialogue can come in weird shapes, not just tit-for-tat, and that soliloquies can happen on the page. Maybe I’ve just gotten to know more women, like Jane, who live at war with themselves, and maybe the freakiness of wanting and hating to be bossed around makes more sense to me now. The whole time, I kept thinking, So many girls read this when they’re kids—and get it. How could it take so long to catch up? —Lorin Stein

Reading a László Krasznahorkai novel is a major commitment, and the kind I’m willing to make, but I haven’t had the time lately to devote myself to it. I’ve made due with the London Review of Books’ recent story “There Goes Valzer.” A man named Róbert Valzer who likes walking (“not that I have anything do to with the famous Robert Walser”) takes an aimless stroll on the Day of the Dead in his La Sportiva boots, through cemeteries and out to the edge of town. Because of its brevity and relatively short sentences, the story offers an opportunity to better appreciate Krasznahorkai’s sly humor, often camouflaged by his melancholic themes. Not that there isn’t disillusionment here, but it’s tempered by a ready absurdity: “I hate Michaelmas daisies and, I must confess, I am not too keen on people either, in fact you might say I hate people too, or, better still, that I hate people as much as I hate Michaelmas daisies and that is simply because every time I see Michaelmas daisies they remind me of people rather than of Michaelmas daisies, and every time I see people I always think of Michaelmas daisies not of people.” (Yes, that is a short sentence—for Krasznahorkai.) —Nicole Rudick

This unending winter—and the moods that have come with it—has reminded many Americans, brutally, of the effect the environment has on our psyches. It’s a theme I haven't encountered in a work of American fiction in recent memory, though I wonder, with our rapidly changing earth, if we’ll begin to see it reflected more in our country's creative output. The seasons and their regularities, their whims have figured prominently in Japanese art for many centuries, though, and Takashi Hiraide's The Guest Cat, recently translated by Eric Selland, is a new cornerstone in this tradition. A short novel about little more than the comings and goings of a neighborhood cat around the grounds and home of a childless couple, the swells and lags in the emotional narrative of the book are propelled by a rising temperature, a blooming flower, a drooping tree. It’s reassuring to feel that perhaps a close tie between one's mental state and the weather may be, in fact, quite natural. —Clare Fentress

Boswell’s The Life of Samuel Johnson is a bit like Nigel Slater’s Kitchen Diaries: there’s an entry for almost every season, holiday, or time of the year. Reading Boswell’s Life, it’s hard not to think of it at times as a great practical joke; Boswell’s silliness is the great enigma of this book. Just to see what he would say, Boswell would ask Johnson questions like “What would you do if you were locked in a tower with a newborn baby?” The entry for Good Friday, 1778, contains so much: a discussion of literary aestheticism and didacticism, of the usefulness that literature can have to society, of the etiquette of making small talk. And it’s full of the usual yuks from the Boswell-Johnson buddy act:

Johnson: “Sir, it would have been better that I had been of a profession. I ought to have been a lawyer.”

Boswell: “I do not think, Sir, it would have been better, for we should not have had the English dictionary.”

Johnson: “But you would have had reports.” —Anna Heyward

I remember the first time I watched The Shining. My hands covered my eyes through half of the film: I saw a flash of room 237, a rotting corpse embracing Jack Nicholson, a flood of blood. “Here’s Johnny!” echoed through my basement. While I didn’t fully comprehend Kubrick’s handiwork at the time, I recognized there was more to the film than its horror/ghost story surface would have you believe. The Native American burial ground (genocide?); the furniture appearing and disappearing (ghosts, madness?); the photo of the July 4th Ball that closes the film (American imperialism?). What a relief it was to watch Rodney Ascher’s documentary Room 237 and realize I was not alone! It’s easy to dismiss many of the ideas here as over-analysis or conspiracy theories—watching the film forward and backward at the same time is my favorite. One theory contends that Kubrick directed the Apollo 11 moon landing. But there’s something beautiful in a documentary about people going crazy over a film about people going crazy. I think the documentary’s assistant editor, Gordon Stainforth, sufficiently got across my thoughts on the film: “The sum of what we learn refuses to add up neatly.” —Justin Alvarez

In the wake of this week’s ferry accident in South Korea—an accident that’s offering no end of tragedy—I came across a harrowing article on the foundering of the Estonia in September 1994. Proceed with caution—it’s almost mathematical in its recounting of the chaos and disorientation of maritime disaster: “Survival that night was a very tight race, and savagely simple. People who started early and moved fast had some chance of winning. People who started late or hesitated for any reason had no chance at all. Action paid. Contemplation did not.” —Stephen Hiltner

I recently had a dream where all my friends had gone gray. They weren’t any different besides that, though everybody was behaving a bit differently, or trying to figure out if they were supposed to behave differently. I think I dreamed this because I read Eileen Myles’s poem “Peanut Butter” a year ago, where she writes, “I’m immoderately in love with you, knocked out by your new white hair.” I saved that line in a notebook I just filled, so I saw it again and read the poem again. I still like it, but I’m inaugurating my new one with “During my life I was a woman with hazel eyes,” because it’s weird, and I’ll want it again next winter. —Zack Newick

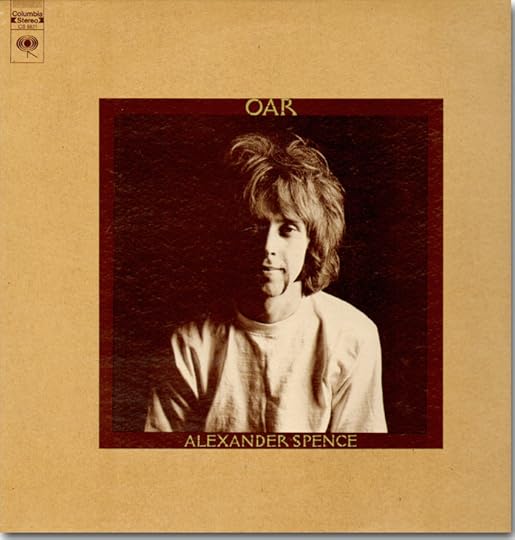

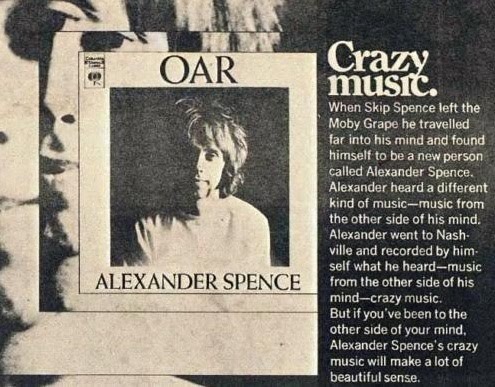

Crazy Music

Skip Spence’s “music from the other side.”

Skip Spence is known for his work in Moby Grape, a seminal psych-rock outfit, and for his only solo album, Oar (1969), which has one of the most gloriously unhinged creation myths in the history of popular music.

In ’68, Spence—who would be, coincidentally, sixty-eight today—was cutting a new Moby Grape record in New York. The city was not bringing out the best in him. One night, as his bandmate Peter Lewis tells it, Spence “took off with some black witch” who “fed him full of acid”: not your garden-variety LSD, mind you, but a powerful variant that supposedly induced a three-day fantasia of hallucinations and cognitive haymaking. The result? “He thought he was the Antichrist.”

Spence strolled over to the Albert Hotel, at Eleventh and University, where he held a fire ax to the doorman’s head; from there, he negotiated his way to a bandmate’s room and took his ax to the door. The place was empty. So he hailed a cab—you know, with an ax—and zipped uptown to the CBS Building, where, on the fifty-second floor, he was at last wrestled to the ground and arrested. He did a six-month stint in Bellevue, where he was deemed schizophrenic. “They shot him full of Thorazine for six months,” Lewis said. “They just take you out of the game.”

But Spence wasn’t out of the game. The same day they released him from Bellevue, he bought a motorcycle, a fucking Harley, and cruised straight on to Nashville, where he aimed to record a series of new songs he’d written in the hospital. He was clad, legend maintains, only in pajamas.

If I had to choose one image to condense and aggrandize the rock ’n’ roll mythos, it would be this: a schizophrenic man fresh out of the loony bin, exultant astride his gleaming new hog, wheels aimed south, gaze narrowed, hands steady, pajamas whipping in the wind.

It’s probably not true, at least not in toto. But Spence did, somehow, make it to Nashville, where, at Columbia’s studios, he recorded and produced Oar in seven days. He plays every instrument on the album.

The label released Oar on May 19, 1969, with zero fanfare. It was their worst seller, and it was soon expunged from their catalogue. Small wonder, given the ads they ran for it, which at once exploited Spence’s illness and doomed his music, suggesting it was inaccessible:

As maladroit as it is, the “crazy music” label stuck, especially as the story of Oar’s creation began to spread, taking on the sheen and hyperbole of urban legend. Ross Bennett describes it as “the ramblings of a man on the brink of mental collapse.” Lindsay Planer writes, “The majority of the sounds on this long-player remain teetering near the precipice of sanity.”

That would imply that Oar is difficult to parse, or fragmented to the pointed of obscurity, or just, like, kind of out there, man. But it’s much more put-together than all that; fragile, yes, off, yes, but not off the deep end. These are folk songs inflected with psychedelia. Their reputation as deranged curios doesn’t stand up.

For starters, Spence’s lyrics seldom bear the scars of his perilous journey to the fringes of consciousness. “Little Hands,” for instance, is just a warmed-over serving of free love:

Little hands clapping

Children are happy

Little hands loving all ‘round the world

Little hands clasping

Truth they are grasping

A world with no pain for one and all

You can practically hear the Thorazine at work. And as for the other eleven tracks, many of them are straightforward ballads—or winking expressions of lust. In fact, if there’s one thing Spence sings about most on Oar, it’s wanting to get laid—hardly the abstruse concern of a man lost to metaphysics.

Still, the music is certainly strange, full of unconventional chord changes, harmonies, and voices, lush at one moment, bare and droning in the next. And lyrically, a song like “Broken Heart” has its far-out moments:

An Olympic super swimmer

Whose belly doesn’t flop

A super racecar driver

Whose pit, it can’t be stopped

A honey dripping hipster

Whose bee cannot be bopped

Better to be rolled in oats

Than from the roll be dropped

Likewise, “Fountain” contains the memorably oblique couplet “If I’m dropping quarters on your bed / It seems like it’s the right thing to do.” Are these images crazy, though, or are they just sort of artfully peculiar?

Oar is maundering and strikingly shambolic—but it’s also a much more cogent statement than its critical reputation suggests. Spence tore across the country to make it happen; he put nine hundred miles between himself and New York. That might be something you’d do if you were insane, but it’s also something you’d do if you were merely insanely ambitious. That’s the greater compliment. To say that the record is a product of monomaniacal drive is much more favorable than to cast it, however desirably, as the crude discharge of an unwell mind. Is it really so difficult to believe that Spence was in control? You should listen to Oar for the music, not for the crazy.

The Coconut Cupcake

Yesterday I made some Easter-themed cupcakes, topped with cream-cheese frosting and dusted with green-tinted coconut. Within each nest, I placed four jelly beans. Brand: Teeny-Been. They were, if I do say so myself, pretty cunning.

When I was asked to contribute a word to Let’s Bring Back: The Lost Language Edition, I was thrilled to have a chance to agitate for my favorite adjective. It’s not that the word has disappeared, exactly, but it has shed one of its meanings. While one usage always denoted craftiness, the other meaning was benign, even infantile. Something cunning was dear, precious, made with craft and care.

Cunning seems to have been particularly appropriate to things on a small scale—perhaps denoting the skill necessary to convey perfection in miniature—and Lord knows we can hardly afford to lose a word in the already-small lexicon of things used to describe the diminutive. Cunning is a second cousin to cute: while cute applies only to the viewer’s reaction and pleasure, cunning gives full credit to the person behind the effect, a sly nod to the intention, and manipulation, behind the effort.

In the 1917 cookbook A Thousand Ways to Please a Husband, a Tut’s tomb of a certain kind of homely vernacular, everything—from triangles of toast to croquettes to the little butterflies decorating the table at a Rainbow Announcement Luncheon to the mini hatchets at a Washington’s Birthday Tea—rates the cunning treatment. This was, as Jane and Michael Stern term it in their “Ladies’ Lunch” chapter of Square Meals, the era of “smart and cunning entertaining,” and no conceit could be taken too far. After all, as A Thousand Ways is at pains to remind us, labor-saving devices were starting to come in. Women’s suffrage could not be ignored. Yes, the characters in these books are homemakers, but they are filled with energy and imagination and the desire to express their tastes and intelligence. The results may seem frivolous, but the intention was clear: to bring beauty, care, and economy to all spheres of life, however limiting or constrained. Cunning indeed.

The Smithereens of Collapse: An Interview with Bill Cotter

Photo: Leon Alesi

Issue 208 of The Paris Review includes Bill Cotter’s story “The Window Lion,” which pairs remarkably well with his new novel, The Parallel Apartments. In fact, they’re related—but I’ll let Cotter talk about that. The novel is the sort of book that invites opposing adjectives: it’s sexy and repellant, “brainy” and full of “heartfelt joy” (Heidi Julavits); it’s comic but also relentlessly, tragically sad. I spent much of my time while reading the novel trying to articulate its tone. I got this far: “the image of Walt Disney’s dick was a revelation.”

Cotter agreed to a talk on the phone—he lives in Austin, Texas. We spoke for well over two hours, about writing, reading, the idea of “a Texas novel,” and his day job as an antiquarian book dealer and restorer. He has an excellent vocabulary and an imagination that’s far-out and fantastic.

While reading, I was reminded of a favorite quote, from William James—“To better understand a thing’s significance, consider its exaggerations and perversions … learn what particular dangers of corruption it may be exposed to.” The novel, especially with regard to sex and relationships, seems a distorted version of reality, a kaleidoscope of exaggerations.

I like the idea that verity can be glimpsed by bending mirrors and chipping lenses. In fact, I don’t know how to get at the truth of characters in any other way. I don’t know how to send characters on movie dates, have them play tennis on a sunny day, or sit them down for turkey and mashed potatoes. In order to get at them for real, it’s necessary, for me, to dress them in silly clothes, hack off their fingers, smear them with ptomaine, then stick them between the sheets or pitch them starved into a cage or just let them rush around erecting bearing walls too weak to hold up the trembling rafters. It’s in the busted minds of troubled offspring, or among bones not quite picked clean, or poking out of the smithereens of collapse that I think the true truths are found.

I’m always interested when a book changes my perception of a place. Here we have a “Texas novel,” and despite the fact that I have not yet been to Texas—shame on me—it feels like a fresh new look at the place and a new take on what some might consider the “Texas novel.” Am I crazy?

How cool it would be if this were someday considered a Texas novel! I don’t think there’s room for it, though—that city block is already crowded with the pre-quadruple-bypass works of Larry McMurtry on one side, and Madison Cooper’s oceanic Sironia, Texas on the other, and there is little room in the alley between them, even for such excellent novels as Jacqueline Kelly’s The Evolution of Calpurnia Tate, Karen Olsson’s Waterloo, and the demi-Texas novels of the honorary Texan Cormac McCarthy. Here we disqualify entirely the unreadable leaden ingot of the decidedly non-Texan James Michener. Even as an Austin novel, mine has little chance to ascend. Billy Lee Brammer’s 1961 The Gay Place, actually a series of three short novels, is solidly affixed to its postament as the quintessential work of Austin fiction and is unlikely to be toppled anytime soon, even though my book is better.

Are you originally from Texas?

I was born in Dallas in 1964, and consider myself a Texan, but I lived elsewhere for many years. In ’73 my family moved to Tehran, and then Ahwaz, a good-size city near the Abadan oil fields. From ’76 to ’94 came the Massachusetts years, a decade of which I mostly spent in psychiatric hospitals or halfway houses. Following stints in New York, New Orleans, and Las Vegas, I found myself in Austin in 1997, arriving in a ruin of a Toyota on the day Diana died. I’ve been here since, and I consider it my hometown.

I like to think that in the novel I paint an Austin that doesn’t often offer itself up for portraiture, one that does not feature the few things that non-Austinites usually collocate with the city, like Stevie Ray Vaughn, Lance Armstrong, SXSW—or, Fuck-by-Fuck-You, the moniker I prefer—Rick Perry, et cetera. But the embarrassing truth of it is that I probably could have set the story, with minor adjustments, in any number of cities. I chose Austin because I know the geography well enough to confidently shuttle the characters about without too much risk of plot paradoxes. I do have a chapter set in the Gulf town of Texas City, about which I will admit another embarrassing truth—I’ve never been there. I just got a feel for it by creeping along the streets with Google Earth.

“The Window Lion” also takes place in Austin, in a place not dissimilar to the apartment complex of The Parallel Apartments. What say you?

Believe it or not, it is the same place! At least in my head it is. I once had a notion to write a collection of interconnected short stories whose common setting was this imaginary complex, which itself is modeled after the Motel-6-style Austin apartment complex called The Dolphin, where I lived in a tiny studio alongside divorcees and grad students and Whataburger cashiers for nine years. But the idea seemed hackneyed, so I abandoned it. “The Window Lion,” and several scenes in the novel, are the most palpable ghosts of the stillborn venture.

This is a book mostly about women. They’re complicated, troubled, and often afraid, but they persevere.

This is a book mostly about women. They’re complicated, troubled, and often afraid, but they persevere.

I don’t think I set out to write about women—I’m mostly interested in people, regardless of gender—but since my first novel, Fever Chart, had a male protagonist, a semiautobiographical one whom I had grown mighty tired of by the time the book was finally published, there was probably some part of me that thought it would be refreshing to build a story around a gender-neutral or female hero, though precisely how the character of Justine Durant, ostensibly the protagonist, grew from a single, discrete, self-spelunker in the beginning of the book to an inextricable member of a five-generation matriarchy, I cannot say. But because the book turned out to feature this matriarchy, and because I sometimes examine it and its members from very close psychic proximities, I worry that I’m being seen by readers—particularly those of non-male genders—as arrogant and condescending. Who am I, as a man, to assay to write so dearly and so extensively about and within genders I can only ever get so close to? Especially about women who happen to be in on one or another phase of motherhood, arguably the state of being most distant from the experience of being a man? I do come from a family of extremely powerful women, and I like to think that maybe the book is a monument to or an appreciation of them.

On the other hand, the men in the book are often “vicious clowns.”

I think the truth of it is that I don’t know how to write real male characters. Maybe the deepest male character in the book is Rance, the auto-rimming, self-cleaning, half-million-dollar multilingual sex robot.

The book is not a particularly violent book, but when it visits, it swings fast and furious.

Fast and furious, yep. I wanted to prod the reader through an impossible, unlivable universe that he might be glad to escape at the end of the book—but the nature of violence, in real life, is always fast and furious. If it wasn’t, we could simply dodge it, unless we’re tied to a chair by vindictive drug cartel torturers. And it seemed that the only way to make violence work in this fictive enterprise was to be loyal to its true nature as sudden, angry, and, for want of a competent synonym, violent.

The book is realistic and yet distorted, even cartoonish. It wasn’t until halfway through that I got a handle on articulating its tone: “She looked down; it was the first time she’d seen his dick, and it did seem like a very nice dick, uniform and subtly arced, a Walt-Disney dick.” If R. Crumb ever wrote a novel it would read like The Parallel Apartments .

I don’t know how to characterize the tone of the book, but I will say I strove to avoid earnestness. And by earnestness I mean sincerity without humor. I think only a truly great writer can get away with being really, literarily earnest without coming across as a cloying and sentimental. Jose Saramago, J.M. Coetzee, and Nadine Gordimer can do it. For us lesser pens, humor is essential, especially when it comes to sex scenes.

But you write sex well—which is not to necessarily say you write good sex. “Justine bit into her own cut lip. It tingled and bled. Franklin got on top of her and went to work in a complicated, be-bop like rhythm. He said he’d read about the present variant in Cosmo, but Justine was sure Darling had taught him this oddball syncopation. Justine didn’t care. She began to buck back. Why had she been unconscious for so long? This was just fine. This was nice.”

When I first started writing seriously, in my mid-thirties, I recall Googling “how to write.” My search was rewarded with a list, written for grade-schoolers, of twenty or so guidelines for writing a good story. The one I recall most vividly is “Make it fun!” This is good theory in general, and, I think, especially important when it comes to writing sex. Sex, the act itself, when viewed without eros, is very silly business, what with all that snuffling and shuddering and pinguid gymnastic theater. It doesn’t look like much fun at all. It is the job of the writer to make it fun on the page, and the only way I know to do this is to subtract sentimentality and add humor. Tease the characters a bit, distract them with jolts and surprises, juxtapose them with highly un-erotic fixtures, assign them curious peccadilloes that impede or amplify performance, maybe throw in a shockingly graphic detail or two, to keep the readers on their toes. Make it fun!

Scott Cheshire earned his MFA from Hunter College. He is the interview editor at the Tottenville Review, and teaches writing at the Sackett Street Writers’ Workshop. His work has been published in Slice, AGNI, Guernica, and the Picador anthology The Book of Men. His first novel, High as the Horses’ Bridles, will be published this summer. He lives in New York City.

The Allure of the Roller Rink, and Other News

Photo: GuillaumeG, via Wikimedia Commons

Marianne Moore’s strange, sad childhood: “Mary [her mother] established a pattern whereby Marianne, in family conversations and correspondence, was invariably referred to as a boy and identified only with male pronouns. Furthermore, Mary encouraged the siblings to regard each other as ‘lovers,’ and to think of her as their ‘lover,’ too.”

In the Paris of the eighteenth century, elite prostitutes were monitored by the fuzz—but why? “A final and enduring theory is that the reports were meant as bedtime reading for King Louis XV and his mistress, the Marquise de Pompadour, who had been the protector of the police lieutenant general most responsible for establishing the unit in the first place. According to this theory, the reports were meant to enliven the reputedly jaded, enervated royal sex life.”

Japanese astronauts took some cherry pits into space. Now, one of them has grown into a mighty cherry tree, perhaps with superpowers.

“Adventure Time is a smash hit cartoon aimed primarily at kids age six to eleven. It’s also a deeply serious work of moral philosophy, a rip-roaring comic masterpiece, and a meditation on gender politics and love in the modern world.”

“I can’t articulate exactly what it was that turned the roller rink into fantasy-on-wheels for me … the feelings I sought only came from visits to those dingy rinks—their smell of ashtrays, sweat, and desolation. In retrospect, part of what I craved was the roller rink’s ability to detach me from the everyday. Because I frequented roller rinks as they were on their way ‘out,’ they seemed to exist apart from the regular world.”

April 17, 2014

Gabriel García Márquez, 1927–2014

García Márquez in high school, as seen in our Summer 2003 issue.

We’re saddened to report that Gabriel García Márquez has died, at eighty-seven. The Paris Review interviewed him in 1981:

INTERVIEWER

Why do you think fame is so destructive for a writer?GARCÍA MÁRQUEZ

Primarily because it invades your private life. It takes away from the time that you spend with friends, and the time that you can work. It tends to isolate you from the real world. A famous writer who wants to continue writing has to be constantly defending himself against fame. I don’t really like to say this because it never sounds sincere, but I would really have liked for my books to have been published after my death, so I wouldn’t have to go through all this business of fame and being a great writer. In my case, the only advantage in fame is that I have been able to give it a political use. Otherwise, it is quite uncomfortable. The problem is that you’re famous for twenty-four hours a day and you can’t say, “Okay, I won’t be famous until tomorrow,” or press a button and say, “I won’t be famous here or now.”

In the summer of 2003, we published an oral biography of García Márquez, lovingly compiled by Silvana Paternostro. Here are a few excerpts from it.

María Luisa Elió: Have you been out on the streets with him? The girls throw themselves at him. It must be annoying … García Márquez’s phenomenon is very special. He has great charisma.

Alberto Fuguet: To read García Márquez at a certain age can be very harmful, and I would forbid it. It can spoil you forever. García Márquez is a software that you install and then can’t get rid of.

Santiago Mutis: The entire world understands [One Hundred Years of Solitude] because it is an epic, a bible. It tells the story of life itself from beginning to end—a human version, with a very Colombian truth. It is life as it is lived here. Colombia is a magical country; the people believe in that. When you go to a market fair in Villa de Leyva, the people spray the truck with holy water so that it won’t fall off the road. I think this is what happened with Gabo: the nation had an oral tradition, and that oral tradition started to get closed in a bit; the cities began taking on an important role. When the pop culture threatened—to stop being oral—Gabo was there to pick it up. It starts to pass into literature; he senses it, starts to refine it—it’s his parents, his family, his land, his friends, it’s everything. Pop culture is the mother and father of art—that is Gabo.

Ramon Illán Bacca: Well, everyone cooks with parsley, but there’s always one cook who takes it to an artistic level. Right? His genius lies in that.

Juancho Jinete: I will never forget when Gabito came and stayed at Álavo’s house, and Juan Gossaín—who is the big cheese in Colombian journalism today—was also at the house. Gabo hugged me and said, “These are my childhood friends.” Then Juan Gossaín told Gabito, “Maestro, let me interview you.” Gabito said to him, “What kind of a journalist are you? What more do you want? You have the story right in your hands. Get it!” It was true—you didn’t have to ask any questions … Gabito told him, “What more do you want? This is my friend here since we were children. There’s your story.”

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers