The Paris Review's Blog, page 716

April 15, 2014

Read Zadie Smith’s Story from Our Spring Issue

Not pictured: Miss Adele, the corsets.

Zadie Smith’s story “Miss Adele Amidst the Corsets” appears in our latest issue, and we’re delighted to announce that, as of today, you can read it online in its entirety. But “Miss Adele” won’t be gracing the Internet in perpetuity; it’s only available while our Spring issue is on newsstands. Subscribe to The Paris Review and you’ll have constant, round-the-clock, 24/7/365 access to this story and a wealth of others, anytime, anywhere, anyhow—digitally, in print, and perhaps in media yet to be invented.

“Well, that’s that,” Miss Dee Pendency said, and Miss Adele, looking back over her shoulder, saw that it was. The strip of hooks had separated entirely from the rest of the corset. Dee held up the two halves, her big red slash mouth pulling in opposite directions.

“Least you can say it died in battle. Doing its duty.”

“Bitch, I’m on in ten minutes.”

“When an irresistible force like your ass … ”

“Don’t sing.”

“Meets an old immovable corset like this … You can bet as sure as you liiiiiive!”

“It’s your fault. You pulled too hard.”

“Something’s gotta give, something’s gotta give, SOMETHING’S GOTTA GIVE.”

“You pulled too hard.”

“Pulling’s not your problem.” Dee lifted her bony, white Midwestern leg up onto the counter, in preparation to put on a thigh-high. With a heel she indicated Miss Adele’s mountainous box of chicken and rice: “Real talk, baby.”

Read the whole story.

The Dadliest Decade

Why were the nineties so preoccupied with fatherhood?

Robin Williams as Peter Banning in Hook, 1991

Some decades are summed up easily, the accretion of cliché and cultural narrative having reached such a point that we hardly need say anything at all. The sixties: hippies, drugs, revolution, rock-and-roll. The eighties: Young Republicans, greed is good, massive perms, Ronald Reagan. This is reductive, obviously, but it’s also helpful cultural shorthand. The nineties, like the seventies, have a less unified narrative: there’s gangster rap, Monica Lewinsky, Columbine, Kurt Cobain, O.J., MTV, white slackers on skateboards, and the LA riots, but they’re all disparate, disconnected. There was no counterculture powerful enough to write the narrative from below, no one mass-cultural or political trend hegemonic enough to make itself the truth. Some enjoy calling this diffusion postmodernism, though most everyone else agrees those people are assholes.

But there was, I contend, a current that ran through the culture of the nineties, a theme that has not to my knowledge been recognized as such. That theme is the heroic dad.

The nineties have sometimes been framed as an assault on family values, what with the Culture Wars and the president’s penis’s interchangeability with a cigar and all, but it was the nineties that saw the dad ascendant in popular culture. By 1990, even the youngest baby boomer was twenty-six, and most of them were solidly in their thirties and forties. They were losing their grip on cool. And they were having kids. It was only natural that they’d want to dramatize the experience. Granted, Bill Cosby, arguably the most quintessential dad in TV history, reached his peak popularity in the mideighties—but the early nineties saw an explosion of hit dad-based sitcoms: Coach, Married … with Children, The Simpsons, Home Improvement, Major Dad. These continued to proliferate throughout the decade; witness Full House and Everybody Loves Raymond, among many others. Many of these were just trying to get a piece of the megasuccess of The Cosby Show and Roseanne. But when those sitcoms are discussed, they’re often applauded for their working-class heroes, while the recentering of dad is less often highlighted. (This is exactly how Reaganite politics worked, too: use lip service to the working class to retrench economic power.)

The trend is more obvious in Hollywood, where the dadventure—don’t look for that term elsewhere; I’m making it up right here—found greater traction than ever in the nineties. You’ll recognize the dadventure if you give it some thought; it’s a subgenre in which the protagonist is a capital-F Father, one whose fatherhood defines both his relationship to the film’s other characters and supplies the film’s central drama. In a dadventure, the stability of the family is threatened—whether by violence or drama, it’s almost always because of some negligence around the dadly duties—and only dad can save the family by coming face to face with his fatherly responsibilities. In the end, he learns just how much fun being a dad can be.

Between 1978 and 1988, there were a total of three dadventures that made the box-office top-ten for their respective years: Mr. Mom, Back to School, and Three Men and a Baby. But then came the nineties: between 1989 and 1999, ten dadventures hit the box-office top ten, and they’re worth listing in full:

Look Who’s Talking

Parenthood

Honey, I Shrunk the Kids

Hook

Father of the Bride

Mrs. Doubtfire

The Santa Clause

The Flintstones

Jumanji

Big Daddy

Since then, from 2000 through 2013, there have been only four: Cheaper By the Dozen, The Pursuit of Happyness, Despicable Me, and Despicable Me 2. (Of course, this tally probably ignores a whole range of films wherein dadliness is defined on Freudian, structural, or mythic levels—where the drama of fatherhood undergirds the film’s meaning without banging you over the head with it. But those are way harder to count, and anyway, shush.)

We all know that culture is aimed, predominantly, at the young: they’re the ones who spend all their disposable income on beer, who don’t have major financial commitments, whose brand loyalty is still up in the air. So why in the nineties, a decade where the counterculture was definitively subsumed by marketing and “selling out” was the major cultural no-no, did dad worship become a profitable trend? Didn’t Gen X just roll its eyes, tell dad to shut up, and move to Austin?

The boomers, the first “generation” constituted as a mass cultural, economic, and political force, were accustomed to being talked about, and it was hard to let go of their cultural centrality. The only problem is that they were the ones who, in their youth, used mass culture to unseat mom and dad, who believed that intergenerational antagonism was a sign of political seriousness. What to do now that they were the squares? And how to face their looming mortality?

If only they could convince their kids they were cool, maybe they could convince themselves.

* * *

One of the most charming dadventures ever made, and the film that most blatantly reveals the belief structure and form of the genre, is 1991’s Hook, a kind of dadly Peter Pan fan fiction turned into a major Hollywood hit by Steven Spielberg.

In it, Robin Williams, history’s number one dadventure star, plays an all-grown-up Peter Pan: he’s left Neverland and is now a successful corporate lawyer (not a joke) who goes by the name Peter Banning. His family life is a mess—he works too many hours to see the wife and kids. But when his two young children are kidnapped by none other than Captain Hook, Peter, who has completely forgotten his eterna-boy identity, has to return to Neverland and remember how to think lovely, wonderful, youthful thoughts in order to restore his powers and save them.

That’s right: Peter Pan, perhaps the most #nodads male figure in the history of English literature, has become a corporate lawyer, but his innate fatherly love for his kids is enough to restore him as an eternal child. Meanwhile, Captain Hook’s evil plan centers, for some reason, on convincing the kids that dad’s a dick. In what is meant to be a climactic evil-might-just-win scene, Hook gets Peter’s son to smash clocks while screaming every instance of neglect and cruelty his dad put him through. That should be evidence enough that Hook is an act of boomer self-assurance intended mainly for the dads in the audience. But it’s the sad tale of the orphan Rufio, who took leadership of the Lost Boys in Peter’s absence, that really perfects the narrative.

No eternal boy-gang can go without a leader, and Rufio—the triple-mohawked Mad-Max punk who runs the Lost Boys as if they’re a queer postapocalyptic skater gang—is way cooler than Pan ever was. Rufio, as you may be able to tell by my enthusiasm for him even twenty years later, is the only point of identification for the kids this film is ostensibly for. He’s the film’s heart, its real hero. Rufio inevitably beefs with Peter, because here’s Pan, as square as square comes, a dad in a boy’s world, claiming to be the mythical departed leader of the gang. It’s only when Rufio is brutally murdered by Hook that our lust for vengeance accommodates us to Robin Williams—i.e., dad—as an actual hero, and even then we accept him only grudgingly.

No eternal boy-gang can go without a leader, and Rufio—the triple-mohawked Mad-Max punk who runs the Lost Boys as if they’re a queer postapocalyptic skater gang—is way cooler than Pan ever was. Rufio, as you may be able to tell by my enthusiasm for him even twenty years later, is the only point of identification for the kids this film is ostensibly for. He’s the film’s heart, its real hero. Rufio inevitably beefs with Peter, because here’s Pan, as square as square comes, a dad in a boy’s world, claiming to be the mythical departed leader of the gang. It’s only when Rufio is brutally murdered by Hook that our lust for vengeance accommodates us to Robin Williams—i.e., dad—as an actual hero, and even then we accept him only grudgingly.

It’s a sneaky but hardly subtle move. Rufio’s last words are “I wish I had a dad like you,” thus framing all of the punk, skater, and boy-gang impulses within one of the decade’s most common political lines: societal problems are caused by poor fathering or the absence of fathers. (This is an accusation leveled most often against communities of color—and it’s no coincidence that the actor who plays Rufio, Dante Basco, is Filipino American.) The kids, it seems, just need to accept that growing up is cool and being a dad is cooler: cooler, at any rate, than being a postapocalyptic punk forever-boy. It’s a nice try, but in 2014, you never see anyone dressing up as Robin Williams’s Banker Pan—come Halloween, everyone’s going as Rufio.

Hook is hardly an atypical dadventure; it’s just particularly barefaced. There’s a whole wealth of nineties culture positioning fatherhood as the real adventure, the really cool thing to do. This is, let’s hope, reflected male boomer horror: the horror of having found oneself in the very position one has spent one’s whole cultural life posing against.

But the nineties was also a decade in which the United States projected itself as a global father. As the only superpower after the collapse of the USSR, all its actions, military and economic, were always framed as beneficial for the people they affected, even when it was exercising “tough love.” NAFTA? Good for Mexican exports. Invading Kuwait? Bombing Kosovo? Humanitarian intervention. Everything was justified by dad logic: the U.S. was only doing it for the other countries’ own good, even if those other countries didn’t like it.

The point is not to claim that Warren Christopher was basing foreign policy on Mrs. Doubtfire. But is it not possible to see the nineties, beneath its postmodern mashup of clashing countercultures and co-option, as a period of return to the fifties cult of the dad, a reentrenchment of the patriarch brought on by the very generation who tried to dethrone him in the first place?

The eighties, at least, were drenched in cocaine and neon, slick cars and yacht parties, a real debauched reaction. But nineties white culture was all earnest yearning: the sorrow of Kurt Cobain and handwringing over selling out, crooning boy-bands and innocent pop starlets, the Contract With America and the Starr Report. It was all so self-serious, so dadly.

Today, by some accounts, the nineties dad is cool again, at least if you think normcore is a thing beyond a couple NYC fashionistas and a series of think pieces. Still, that’s shiftless hipsters dressed like dads, not dads as unironic heroes and subjects of our culture. If the hipster cultural turn in the following decades has been to ironize things to the point of meaninglessness, so be it. At least they don’t pretend it’s a goddamn cultural revolution when they have a kid: they just let their babies play with their beards and push their strollers into the coffee shop. In the nineties, Dad was sometimes the coolest guy in the room. He was sometimes the butt of the joke. He was sometimes the absence that made all the difference. But he was always, insistently, at the center of the story.

Willie Osterweil is a writer and editor at The New Inquiry.

Bob Ross by the Numbers, and Other News

A publicity still from Bob Ross’s The Joy of Painting

Donna Tartt’s The Goldfinch has won the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction.

John Jeremiah Sullivan’s latest piece is a masterful look at two musicians who have fallen into obscurity: “In the world of early-20th-century African-American music and people obsessed by it … there exist no ghosts more vexing than a couple of women identified on three ultrarare records made in 1930 and ’31 as Elvie Thomas and Geeshie Wiley.”

A statistical analysis of the paintings of Bob Ross. (Ninety-one percent contain at least one tree; 39 percent contain at least one mountain; 21 percent contain cumulus clouds.)

Taking stock of today’s art world: “The artist has undergone an enormous increase in value, to the point of idolization. But success has come at a high price, with the power of the art system, the adjustment to taste guidelines, and the dependence on galleries and curators. To create something new all one’s own, while remaining in the game, is a balancing act that only few succeed at mastering.”

An interview with Black Dog Bone, the founder, publisher, and editor-in-chief of Murder Dog, hip-hop’s most “potent” underground magazine.

“The original designs for the cubicle came out of a very 1960s-moment; the intention was to free office workers from uninspired, even domineering workplace settings.”

April 14, 2014

On Knowing Things

Photo: Allen Timothy Chang

Yesterday, I was one of several people manning a book-centric advice booth as part of a New York literary festival. For days beforehand, I was paralyzed with nerves. I couldn’t face the other, more legitimate advice-givers; I felt like a charlatan and an impostor. I had something of an existential crisis.

I have always wanted to be a maven. But my standards are high, because I once knew a true maven. She was not a know-it-all; she just knew everything. I met her when I was nineteen and my college boyfriend and I were traveling through London. Lise, who at the time was in her seventies, was a friend of his family, and she was the sort of hostess who welcomed friends, and friends of friends, and acquaintances of friends, to stay with her in her flat, south of Hyde Park.

She was an imposing sort of person, her already-deep voice further deepened by years of chain-smoking. In later years, she had a stern doctor and would periodically use some sort of early e-cigarette, but the Marlboro Reds would generally reappear on the kitchen table. As would the whiskey, the butter. She could speak Russian and German and French and had worked as a translator. Meals at her house lasted for five hours, and at the end everyone was drunk but her. Formerly involved with helping end theater censorship in England—and the widow of a spy-turned-diagnostician-turned-mystery-writer—she seemed to know everyone. Beckett and Pinter and Peter O’Toole would all turn up in her stories; other Sunday lunch guests might be Labour whips, or countesses, or just someone’s young daughter who had lost her way and needed a place to stay for a while.

The food was always good, if idiosyncratic. Meals were all sided by a sweet, vinegary, dilled cucumber salad—a tribute to the time her family had spent in Finland—and often ended with strawberries dressed with Grand Marnier and a dash of orange flower water. There were always far more cheeses than one wanted, and far more wine. When I turned twenty-one, she threw a sumptuous birthday luncheon and we all drank so much champagne, and ate so many oysters, that we were sick. She wasn’t, of course.

A few years later, when I was living in London myself, she asked me to help her alphabetize her extensive library. Like many disorganized people, I enjoy order as a novelty—like a vacation—and fell to the task with enthusiasm. Given that I am quite short and not particularly strong, I was in retrospect a strange candidate for the job of moving several hundred volumes on very high shelves. But maybe she sensed that I needed the satisfaction of a doable physical task. Maybe she knew how much our friendship would help me. Maybe she was lonely.

She missed her husband terribly. My boyfriend and I read his novels—which featured a portly spy-turned-doctor-turned-crime-solver with a penchant for Savile Row suiting—and listened for hours to stories of his exploits. He had been quite autocratic. Apparently, one day in the early sixties, he had directed her to buy a pretty dress; then he’d picked her up, driven her to city hall, produced a marriage license, handed her a bouquet, and married her without a by-your-leave. The wedding dress—a brown-figured silk jersey, very much of its era—still hung in the spare room where I would sometimes stay.

When I say she knew everything, I am exaggerating, of course, but in the realm of civilized pleasures, she was indeed sage. You could ask her about the finest recording of a Bach cantata, where to rent a morning suit, who made the best pumpkin ravioli, whether Cuban cigars were a good price—and she would really know. Not just about London, but all over the world. She had opinions on everything: Swiss-made vegetable peelers, hagiographic biographies, overinflated wine vintages, politics, toasting protocol—and was given to unilateral pronouncements. “Like all very large men,” she once said of her late husband, “he was very light on his feet.”

She died relatively young—her doctors had not been wrong about her hard living—and her ashes were buried in a garden next to her husband’s. Not long before she died, she gave me her collection of miniature books, which I had always loved. They sit in my bedroom now.

* * *

So that is my idea of a qualified advice-giver. Of course, I need not have worried, because in the end, I did not need to know everything. I was able to recommend books I loved—After Claude and Pitch Dark—to a guy looking for first-person 1970s fiction. I talked about recent writing on the subject of marriage with a woman I know. A very polite young woman from New Zealand was kind enough to ask me about New York writing that she could read quickly; I suggested Here Is New York and the new anthology Goodbye to All That. A couple of people wanted publishing advice; a few friends stopped by to say hello. The hour passed quickly, and I had fun, but I am not at all sure I have the stuff of mavens in me.

Then again, there are different sorts of lessons. Lise told one story about a famous London theater critic and his wife, an American writer. At one of Lise’s celebrated cocktail parties, she came across the writer in question grinding out cigarettes into the parlor carpet with a chic midsixties pump. Lise politely asked her to stop.

“Fuck off, bitch,” replied the woman.

“This is my house,” said Lise, “and if there is to be any fucking off, it shall be done by you.” At which point she quite firmly showed them the door.

Sometimes an instructive anecdote is better than any advice. And when someone asked me yesterday if I liked said writer’s best-known novel, I said, quite honestly, that I found the voice unsympathetic.

Where They Create

If you’ve seen the photos of last week’s Spring Revel, you might be under the impression that life at The Paris Review is a ceaseless parade of Bellinis and photo ops, full of mirth and joie de vivre and toast after graceful toast, all elegantly lit and impeccably groomed. And don’t get us wrong—it’s all of those things. But we cannot lie. Every once in a while, it’s quieter around here.

Last month, Paul Barbera—who curates Where They Create, a site that chronicles the studios and work spaces of artists and writers—photographed our office on behalf of Svbscription, “a new service that delivers luxury, hand-selected products, and experiences to your door.” Paul’s excellent photos capture an average day on 544 West Twenty-Seventh Street; we’re happy to present a selection of them on the Daily. (Note that the desk of a certain Web editor—cluttered with books and papers, and looking not unlike the carrel of a wayward theologian who’s just discovered the threshold to hell—is very judiciously not pictured.)

You can see the rest of Paul’s Paris Review photos here, and read Svbscription’s interview with Lorin Stein here.

Recapping Dante: Canto 25, or a Trip to the Reptile House

William Blake, The Circle of the Thieves; Agnolo Brunelleschi Attacked by a Six-Footed Serpent, Canto XXV, 1827

We’re recapping the Inferno. Read along! This week: Virgil shuts up and men become reptiles.

Canto 25 is known for having the least dialogue of any canto in the Inferno. It seems like a minor feat, but when you remember how many questions Dante likes to ask, and how long Virgil will typically spend explaining things, and how sinners really like to chat it up with the living, canto 25 begins to seem remarkable. In fact, Virgil hardly has the chance to explain anything at all here.

It begins with Vanni, the sinner from canto 24 who, in a fit of shame and spiteful anger, revealed to Dante the sad fate of the White Guelph party in Florence. Vanni makes an obscene gesture into the air, and curses God. And although we do not know exactly what “Making the figs with both his thumbs” means, we can guess that it is the centuries old Italian way of flipping God the bird. Dante wants to get away, and the snakes from the previous canto attack Vanni, hog-tying him and wrapping themselves around his neck to silence him.

As Dante leaves Vanni, a centaur—with snakes on his back and a dragon on his shoulder—starts screaming. The centaur’s voice was the mysterious sound Dante heard in canto 24, before he lost interest. This is Virgil’s only didactic moment in the canto: he tells Dante that the centaur is Cacus, who was clubbed to death by Hercules. (Accounts of Cacus’s death vary depending on the poet’s preference—strangely, the version Virgil tells Dante is not the version Virgil himself wrote about. Virgil’s Cacus was strangled to death.) Dante uses canto 25 to quarrel with other poets. Later, he describes a scene in which two sinners change their physical appearances, and he essentially tells the reader that this scene is far more striking than any of the shape-changing moments written by Ovid or Lucan.

The rest of canto 25 features a lineup of sinners, all of them Florentines—just in case Dante’s thoughts on the state of Florence weren’t clear enough. One has to wonder: With all the terrible sinners in Florence and the disastrous state of politics in the city, what’s left there for Dante to like at all?

First, Dante watches as a reptile bites a sinner; as the beast wraps itself around the sinner’s body, clinging to him like ivy, Dante says, “Slowly, the two become one,” becoming some frightening, unknown beast with one head, one pair of limbs, and “members never seen before.” Unlike many of the other punishments, which are designed primarily to inflict pain on the sinners, this one is psychological—it’s demeaning.

And it seems rather effective. Our pilgrim is bewildered by the scene before him. But he’s about to witness something far more harrowing: as the first transformation finishes, another reptile scuttles out and bites another sinner in the stomach. As the two become transfixed, staring at one another, a thick smoke pours from the reptile’s mouth and from the sinner’s wound. Soon, the two plumes of smoke merge, and slowly the reptile takes on the shape of a man. Its tail becomes legs, its limbs become arms, it grows human skin and walks upright, and its animal features become a human face. As the reptilian hiss slowly becomes a human voice, the wounded sinner and the reptile exchange bodies—the sinner makes the same transformation, but in reverse. Dante believes he may be able to recognize the sinner who had just taken a human form—Francesco de’ Cavalcanti.

There is something gruesome and poetic in the absolute precision of Dante’s descriptions of the metamorphoses. Canto 25 offers a rare, scientific glimpse into the nature of punishment in hell, and it stands out, along with the forest of suicides and Pier delle Vigne, as one of the more definitive examples of how punishments in hell actually work.

To catch up on our Dante series, click here.

Alexander Aciman is the author of Twitterature. He has written for the New York Times, Tablet, the Wall Street Journal, and TIME. Follow him on Twitter at @acimania.

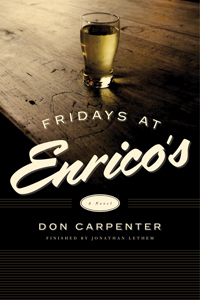

Finishing Carpenter

Editing Don Carpenter’s final manuscript.

Photo via doncarpenterpage.com

Part of my job as a clerk at Berkeley’s great used bookstore Moe’s, in the early nineties, was to scour the massive wall of fiction and confront the books that weren’t selling. Out of all the staff I claimed this task because it interested me the most, and because it suited my vanity to be able to claim that “I run the lit section.” Codes, written in pencil, and discretely tucked into the corner opposite the asking price, revealed when a given title had hit the shelf. After six or eight months you reduced the price. Once it had been knocked down a couple of times, two options remained: chuck the book into the pile of discards under the staircase, or take it home and read it.

A Couple of Comedians, with its great title and Norman Mailer blurb, got me to flip it open. When right there in the stacks I was met with Don Carpenter’s punchy prose, and with his grabby, wry, and humane outlook, I took the book home. I read it. I loved it. I looked downstairs, in our pocket-size paperback stacks, and found a copy of Hard Rain Falling, Carpenter’s first novel, repackaged with a Tom of Finland–style painting and corresponding jacket copy to sell as “gay lit” (“The hard-hitting novel of a young street tough and his inevitable journey toward prison—and self-knowledge …”). I read Hard Rain Falling and thought it made two masterpieces in a row. The suggestion given by the dust jackets of the two books—and the move from the Northern California bildungsroman of Hard Rain Falling to the entertainment industry hijinks of comedians—was of a writer who, failing to sustain a literary career, had migrated to Hollywood and was, all too typically, never heard from again.

My next move—a compulsive one, for me, when I discovered an out-of-print writer—was to go to Peter Howard’s Serendipity Books, a legendary Borges-like physical compendium of seemingly every book ever published, which happened to be just down the street from my house. You could call my visit the equivalent, nowadays, of googling. At Serendipity, sure enough, I found a run of all of Carpenter’s early books, including an autographed copy of Blade of Light I purchased and still own. I also found the three late-eighties books published by Jack Shoemaker’s North Point Press. Carpenter, from the evidence, had not only survived Hollywood, but was alive and writing and living nearby. After I’d read a few more of the books I flirted with the idea of find my way up to Marin and presenting myself to Carpenter as his “biggest fan” (“and I run the lit section!”). It appeared that finding him might not require more than puttering around Mill Valley’s central square for a few hours, and poking my head into a coffee shop or two. I didn’t manage this—whether for the better or worse, I’m spared knowing. In 1995 came word that the sixty-four-year-old Carpenter, who’d been suffering a host of illnesses that severely restricted his ability to work, had killed himself.

Though I wasn’t actually alone in my admiration, it took a while for Carpenter’s scattered constituency to discover one another. For years he was “in print” only as the protagonist of a few anecdotes in—and as the dedicatee of—Annie Lamott’s talismanic writer’s handbook Bird By Bird. George Pelecanos and I both advocated for Hard Rain Falling to Edwin Frank at New York Review Books, and when it was published in their reprint series, with a Pelecanos introduction, it gave occasion for tributes from fans like Ken Tucker and Charles Taylor and Sarah Weinman, readers familiar with others of the books, and with Carpenter’s great screenplay, Payday. For all of us, Carpenter, though difficult to categorize and never famous in his own day, was a writer who mattered, one who not only wouldn’t go away, but grew more significant in memory. This in turn encouraged those who were caretakers of a substantial unpublished manuscript—Shoemaker, and Carpenter’s daughter Bonnie—to reexamine the case for publication, after a nearly forty-year time-out. That’s where this more specific story of Fridays at Enrico’s begins.

When asked by Shoemaker if I’d weigh in on the “unfinished” manuscript that had been supplied him by the estate, I felt exhilarated and trepidatious. Even a single additional paragraph of Carpenter felt like a gift, but what if the book wasn’t good, or wasn’t good enough? Plenty of writers slide toward the end, and though I was grateful for the existence of Carpenter’s last few books, they weren’t exactly the ones I was prone to obsessively rereading, or recommending to others. Then again, who would I be, to presume to recommend against publication? I’m a fan of scraps, fragments, letters, any trace of a writer I admire; I like The Castle and The Crack-Up and Edwin Drood. Still, it might be perverse to follow the rediscovery of Hard Rain Falling with something marginal. Not while the terrific Hollywood novels, and others that Carpenter had deemed ready, and which had been embraced by readers, if too few, remained out of print.

My concerns were misplaced. I’ll leave it for others to rate Fridays at Enrico’s amid Carpenter’s best—I’m too far inside this book now to play the role of its evaluator as well—but from page one the manuscript cast me as an appreciative reader, not a triage nurse. The voice was in place, the architecture solid, Carpenter’s wily purposes well enacted throughout. It had a fine ending, too. Knowing the book existed, that Carpenter had pulled it off, whether destined to be published or not, made the world a slightly but crucially bigger place. I told Shoemaker I thought he should publish, and that I’d do what was necessary. The chance to flatter myself by coming in like Mariano Rivera in the ninth was irresistible.

I retyped the whole book, wanting to get Carpenter’s syntax into my body, to trust myself with anything I changed. More than anything, I took stuff out. Carpenter’s unedited draft restated certain motifs, making preliminary gestures in an early chapter for effects he’d carried through in later pages, so I deleted the preliminary gestures. He used the word but too much, and his characters “grinned” or were “grinning” far too often—they still probably grin too often, but I did what I could. Some things I took out only to put back in: an apparently irrelevant bit of business with a parking attendant, for instance, turned out to set up a writer’s inspiration for a story a few pages later. Carpenter was subtle. Among his subtleties was a restriction of the book’s vocabulary, which, despite seeming repetitive at times, gave the novel a certain humble integrity, bringing the voice into the range of the characters and their world. I’d only wreck it if I tried to impose variations. Four or five chapters I needed to turn inside out—they’d begun on the wrong foot, but the right foot was waiting, a page or two in, for me to bring forward. Against what I removed I added just a few passages, covering some missing transitions, the odd inexplicable lapse or two. There might be five or eight pages of my writing in the book, but I’d like to think you’d never guess which, should you bother even to care. Mostly, to be truthful, this was a job of data entry: the book proved itself right by the way it refused to be altered, moving through my fingers, as a house might prove itself sound by being lived in a while.

Fridays at Enrico’s is a book about writers, lots of them. But it never feels insular, because none of the characters, even those who publish, effectively inject themselves into any “literary” milieu. They remain outsiders and strivers, defined by their struggles even to believe they can lay claim to this calling, let alone turn it into some kind of career. In their estrangement simultaneously from the lives of common working folk yet also from any exalted or precious notions of living the life of an “artist”—and in the way they mediate their estrangement through drinking—Carpenter’s characters recall those of Richard Yates. This may partly be a matter of simple realism in the depiction of a certain lives that were being lived in the fifties and sixties, but as a final statement this book reminds me specifically of Yates’s own, the underrated Young Hearts Calling (admittedly a book cursed with one of the worst titles going). Of course there were twisty little ironies attendant in rewriting a manuscript that concerned not only writers writing manuscripts, but writers being rewritten by editors, and feeling bitterly betrayed by the results. The task even had the power make to me self-conscious of my typing habits, so keenly does Carpenter attend to this now-retro feature of his characters’ avocation (there’s also an important learning-to-type scene in Carpenter’s second novel, A Blade of Light). I hadn’t retyped an entire manuscript since one of my own in the early nineties. It’s a good habit, one I may have to resurrect.

Of course, the book’s writers, like Carpenter himself, were estranged from the literary establishment in a way Richard Yates could never have conceived: by three thousand miles of incomprehension. In a tender and revealing reminiscence of his close friend Richard Brautigan, called “My Brautigan: A Portrait from Memory,” Carpenter wrote, “Over the years (our) walks and talks got to be more and more about what Richard called the East Coast Literary Mafia. Richard’s work was known and respected all over the world, in many languages, but somehow he could seldom get a good review in America. He made the whole thing into an East vs. West issue, which maybe it was and maybe it wasn’t.” The tone is typical Carpenter, compassionate, and worldly without being cynical. The West Coast traditionally celebrated in American letters is an allegorical one, encoding Manifest Destiny, presenting the place as an existential testing-ground for notions of utopia and self-reinvention, even if only to expose the bankruptcy of those prospects. Raymond Chandler, Nathanael West, Ken Kesey, the Beats, even Brautigan himself can be understood on these terms (ironically, it’s a fundamentally Eastern view of the West). The California in Don Carpenter’s books, whether Northern or Southern, and the settings in Portland, Oregon, reveal something simpler but in some ways stranger to consider. Carpenter writes as someone who knows the West as a real geography, with a culture of its own, a place to live out the usual quandaries of existence, rather than a petri dish for American Destiny. For that reason, too, his view of the writer-in-Hollywood is free of the clichés that plague the genre.

Of course, the book’s writers, like Carpenter himself, were estranged from the literary establishment in a way Richard Yates could never have conceived: by three thousand miles of incomprehension. In a tender and revealing reminiscence of his close friend Richard Brautigan, called “My Brautigan: A Portrait from Memory,” Carpenter wrote, “Over the years (our) walks and talks got to be more and more about what Richard called the East Coast Literary Mafia. Richard’s work was known and respected all over the world, in many languages, but somehow he could seldom get a good review in America. He made the whole thing into an East vs. West issue, which maybe it was and maybe it wasn’t.” The tone is typical Carpenter, compassionate, and worldly without being cynical. The West Coast traditionally celebrated in American letters is an allegorical one, encoding Manifest Destiny, presenting the place as an existential testing-ground for notions of utopia and self-reinvention, even if only to expose the bankruptcy of those prospects. Raymond Chandler, Nathanael West, Ken Kesey, the Beats, even Brautigan himself can be understood on these terms (ironically, it’s a fundamentally Eastern view of the West). The California in Don Carpenter’s books, whether Northern or Southern, and the settings in Portland, Oregon, reveal something simpler but in some ways stranger to consider. Carpenter writes as someone who knows the West as a real geography, with a culture of its own, a place to live out the usual quandaries of existence, rather than a petri dish for American Destiny. For that reason, too, his view of the writer-in-Hollywood is free of the clichés that plague the genre.

Speaking of Brautigan, the notion has clung to Fridays at Enrico’s that the project began for Carpenter as an attempt at a memoir of their friendship, or even a biography. I can’t really see how this explains the resulting book, except that novelists frequently begin with one thing and end up with something else. Carpenter was plainly a true native of the realm of the novel, so that any portraiture or self-portraiture here—and surely there’s both—has been distributed among several characters, then subsumed in the other kind of “truthfulness” that a novel, by its form, demands. For what it’s worth, the character of Stan Winger—my favorite in the book—seems directly influenced by the life story of Malcolm Braly, the much incarcerated author of On the Yard, in my opinion the other best prison novel in U.S. literature—besides Hard Rain Falling, that is.

Yet I have no evidence that Carpenter knew Braly personally, not that I’ve done much digging. I still know barely more about Carpenter’s actual life story than you can learn from the dust jackets of the books, from the interstices of William Hjorstberg’s encyclopedic biography of Brautigan, and from the lovely volunteer Web site maintained by the estimable and modest “Chris.” It was there at the Web site that I discovered, in the scanned pages of a priceless 1975 interview, that Don Carpenter only ever spent a single night behind bars: “Seaside Oregon. Carrying six cans of beer down the street. Moping with an intent to gawk. That’s the most jail time I’ve done.” How, then, did Carpenter attain his extraordinarily sympathetic portraits, in Hard Rain, Blade of Light, and now in Enrico’s, of the prisoner’s life? The usual way: with his ear, with his curiosity, with his vulnerabilities, with his talent. In the same interview, discussing Blade of Light, Carpenter makes clear he sees incarceration as a baseline condition, that of selves stuck in bodies, and bodies stuck in fates: “He’s inside there, and he knows he’s trapped in there, just as you know you’re trapped in here, see? … I mean, you know, we’re all caught in this thing. We all wake up at three o’clock in the morning saying ‘How am I gonna get out of here? … Can I start over? Can I do anything to be someone else?’” Consider that those were the words, in 1975, of a man who had yet to lose his health, and much of his eyesight. In that light, it’s hard not to see his portrayal of Stan Winger, locked in solitary confinement and working to set in language a vivid description of the fresh taste of the first sip of a glass of beer, as a self-portrait of a writer in a failing body reconstituting a world of sensory pleasures from which he’s increasingly barred. Similarly, near the end of Enrico’s the female novelist Jaime Froward reflects on her apprentice days in the woods outside Portland, learning to write while caring for a new baby, days fiercely lonely and embattled as she lived through them, yet in recollection the finest she’d ever known. In the breadth of human experience imparted by this book we’re taken as near to memoir as we’d ever require from Don Carpenter, who said, “If I was able to express my views of the universe without writing fiction, I would do so.” Lucky for us he couldn’t.

Jonathan Lethem’s latest book is Dissident Gardens.

A version of this essay appears as the afterword to Fridays at Enrico’s. Copyright © 2014; reprinted with the permission of Counterpoint Press.

Poe in Bronze, and Other News

The clay model of Stefanie Rocknak’s proposed Edgar Allan Poe statue. Photo via My Modern Met

This fall, Boston plans to erect an impressive new statue of Edgar Allan Poe: a raven at his side, a veiny heart tumbling from his “trunk full of ideas,” his coat billowing in the wind.

Against the word relatable: “It presumes that the speaker’s experiences and tastes are common and normative … It’s shorthand that masquerades as description. Without knowing why you find something ‘relatable,’ I know nothing about either you or it.”

“Futurologists are almost always wrong … The future has become a land-grab for Wall Street and for the more dubious hot gospellers who have plagued America since its inception and who are now preaching to the world.”

Why are so many young-adult novels set in dystopias? “The complete collapse of the narrative of what a secure future looks like for today’s young people … [has] fostered a generational anxiety about how to cope with overmighty state power.”

In case you missed it—last week, “a German fisherman pulled a 101-year-old message in a bottle out of the Baltic Sea.” (It was not, thankfully, an SOS to the world.)

“In the recent history of American music, there’s no figure parallel to Tom Lehrer in his effortless ascent to fame, his trajectory into the heart of the culture—and then his quiet, amiable, inexplicable departure.”

April 12, 2014

Frederick Seidel on Massimo Tamburini

The Ducati 916, designed by Tamburini. Photo: ScuderiaAssindia, via Wikimedia Commons

Massimo Tamburini died last Sunday at seventy. Tamburini was an Italian motorcycle designer; his work for Ducati, Cagiva, and MV Agusta set the standard for artful, stylish . The journalist Kevin Ash said that Tamburini’s design for the Ducati 916, which debuted in 1994, “moved it forward, personalized, and Ducati-fied it, in particular the blend of sharp edges and sweeping curves, which, like most innovation, broke existing rules.” And this week’s obituary in the Times found many enthusiasts who were unstinting in their praise:

For decades Mr. Tamburini reigned as “the Michelangelo of motorcycling,” as The Sunday Express, the British newspaper, called him in 2010, and his work exerted a pervasive influence on the look of motorcycles in the late 20th century.

“He always gave great élan to the shapes,” Bruno dePrato, the European editor of Cycle World magazine, said in a telephone interview on Wednesday. “This élan is not aggressiveness, with very edgy shapes and other excesses in styling. His bikes were just shaped by the wind.”

As it happens, Frederick Seidel, whose readers know him as a Ducati aficionado, had paid homage to Tamburini and the Ducati 916 in his poem “Milan,” from the 1998 collection Going Fast. (Curiously enough, Jonathan Galassi also read the final lines of “Milan” in his salute to Seidel at our Spring Revel on Tuesday; read on and you’ll see why.) In memory of Tamburini and his legendary designs, we’ve reprinted the poem here.

MILAN

This is Via Gesù.

Stone without a tree.

This is the good life.

Puritan elegance.

Severe but plentiful.

Big breasts in a business suit.

Between Via Monte Napoleone and Via della Spiga.

I draw

The bowstring of Cupid’s bow,

Too powerful for anything but love to pull.

Oh the sudden green gardens glimpsed through gates and the stark

Deliciously expensive shops.

I let the pocket knives at Lorenzi,

Each a priceless jewel,

Gods of blades and hinges,

Make me late for a fitting at Caraceni.

Oh Milan, I feel myself being pulled back

To the past and released.

I hiss like an arrow

Through the air,

On my way from here to there. I am a man I used to know.

I am the arrow and the bow.

I am a reincarnation, but

I give birth to the man

I grew out of.

I follow him down a street

Into a restaurant I don’t remember

And sit and eat.

A Ducati 916 stabs through the blur.

Massimo Tamburini designed this miracle

Which ought to be in the Museum of Modern Art.

The Stradivarius

Of motorcycles lights up Via Borgospesso

As it flashes by, dumbfoundingly small.

Donatello by way of Brancusi, smoothed simplicity.

One hundred sixty-four miles an hour.

The Ducati 916 is a nightingale.

It sings to me more sweetly than Cole Porter.

Slender as a girl, aerodynamically clean.

Sudden as a shark.

The president of Cagiva Motorcycles,

Mr. Claudio Castiglioni, lifts off in his helicopter

From his ecologically sound factory by a lake.

Cagiva in Varese owns Ducati in Bologna,

Where he lands.

His instructions are Confucian:

Don’t stint.

Combine a far-seeing industrialist.

With an Islamic fundamentalist.

With an Italian premier who doesn’t take bribes.

With a pharmaceuticals CEO who loves to spread disease.

Put them on a 916.

And you get Fred Seidel.

April 11, 2014

What We’re Loving: Communism, Climates, Cats

Joseph Stalin with his daughter Svetlana, 1935.

Shortly after moving to New York, I found a used copy of Twenty Letters to a Friend, a memoir, written in 1963, by Svetlana Alliluyeva, Stalin’s daughter. It’s an unlikely book, to say the least—she condemns Communism, details her father’s agonizing death, and tries to come to terms with her own, very particular Stalinist experience—and it fed my budding fascination with Soviet cultural history. Nicholas Thompson’s essay in the March 31 issue of The New Yorker, which describes his friendship with Alliluyeva and her experiences in the United States, was a reminder of how that bizarre, late Soviet period had first piqued my interest. I’d never read, though, about Alliluyeva’s encounter with Frank Lloyd Wright’s widow, Olgivanna, an adherent of the theosophist G.I. Gurdjieff. Oligvanna believed Alliluyeva to be the reincarnation of her daughter, also named Svetlana, and wanted her to marry the dead woman’s husband; she did. It’s the kind of thoroughly weird story that couldn’t possibly be true, but then, this is Stalin’s daughter. —Nicole Rudick

After receiving two uncomprehending reviews in the New York Times, Jenny Offill’s novel Department of Speculation has finally gotten the kind of attention it deserves, first from James Wood in The New Yorker and now from Elaine Blair in The New York Review of Books. The latter is actually more than a review; it’s a brief and startling essay on the place of adultery in fiction today. Of the marriage in Department of Speculation, Blair writes, “How can a relationship so intensely intimate and companionable seem so easily soluble? And what is that other thing, extramarital sex, that has everyone quickly making contingency plans to jump ship? The wife and husband’s exemplary, perhaps even ideal, modern marriage is a form of personal gratification—a nonbinding choice that is very much bound up with the ego.” When Blair writes about fiction, she writes about life, which in some moods seems to me the only way to do it. Read an excerpt of Offill’s novel in issue 207. —Lorin Stein

I don’t often have the time to reread these days, but I recently gave a copy of André Maurois’s Climates to a friend, and he enjoyed it so much that I was inspired to revisit it. It’s an autobiographical novel of love lost, found, and lost again, the kind of book you find yourself giving to all your friends, wanting them to read it immediately so you can marvel at it together. Back when I first read Sarah Bakewell’s beautiful translation, I felt it mirrored the melancholy of events in my own life. I worried, I think, that it wouldn’t resonate as much now. But I was wrong: it is a gripping read, deeply felt, and so full of memorable lines that I wanted to dog-ear every other page. I would have, except that this time it was a library copy—I had long since given mine away. —Sadie Stein

When I rewatched Paul Thomas Anderson’s Punch-Drunk Love, I knew, faintly, that the film’s odd pudding subplot was based on a true story. But only now have I done my homework. Fun fact: in 1999, a Californian engineer named David Phillips was grocery shopping when he noticed a loophole in a frequent-flier offer on Healthy Choice products. He did the math and discovered that if he could purchase enough cheap Healthy Choice–brand foods, the value of the miles would exceed the cost. So Phillips scoured the region, buying up some twelve thousand cups of Healthy Choice pudding—the cheapest product he could find, at a quarter a cup. He redeemed them for 1.25 million American Airlines frequent-flier miles. This is that rare thing, a Kafkaesque story with a happy ending: a man confronts the warped logic of bureaucracy and emerges victorious. It was shrewd of Anderson to rip it from the headlines. In Punch-Drunk Love, Adam Sandler’s character makes the same discovery, and it softens his neurotic, seething violence. He’s attuned to the world, we see, just vibrating on a different wavelength. The plot gets at the surreal, godlike power that corporations can wield in our lives, descending from on high to deliver the occasional windfall or catastrophe. As Sandler’s character says, “I have to get more pudding for this trip to Hawaii. As I just said that out loud I realize it sounded a little strange, but it’s not … You can go to places in the world with pudding.” —Dan Piepenbring

Which of the stories in our pasts should define us? All of them? Only the good ones, or maybe just the worst? In Diary of the Fall, the Brazilian novelist Michel Laub explores the aftermath of a cruel prank his unnamed narrator played on the only Catholic student at a Jewish school in Rio. The account is interwoven with his father’s battle with Alzheimer’s and his grandfather’s survival of Auschwitz. Brutal yet delicate, Laub’s novel asks what it means to be Jewish in the twenty-first century, and it attempts to understand man’s basic identity, “part of a past that is likewise of no importance compared to what I am and will be.” —Justin Alvarez

The passing away of Dan’s cat earlier this week [Ed.—it’s true, I’m sad to say] put me in mind of a poem by the Australian poet Peter Porter, “The King of the Cats Is Dead.” I don’t know if Dan’s cat was the king—we never met—but they are all regal in their own way: some more Robert Baratheon, some Renley, and many, we should acknowledge, Joffrey. Often they are all three at once. Porter’s poem is a sort of mock epic, but it feels genuine, too: a lament for lost mystery and grandeur. Though I may be imposing, it also strikes me as a testament to the stature, in our own eyes, of the things we love. “Time is explored / and all is known, the portents / are of brief and brutal things, since / all must hear the words of desolation / the King of the Cats is Dead / and it / is only Monday in the world.” —Tucker Morgan

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers