The Paris Review's Blog, page 720

April 3, 2014

The Uncommon Birds of George Edwards

The American Kingfisher

The Bearded Vulture

The Toucan or Brazilian Pye

The Golden Bird of Paradise

The King Bird of Paradise

The Whooping Crane

The Black-Capped Lory

The Green Parrot of the West Indies

The Longest-Tailed Hummingbird

The Ornate Lorikeet

The Penguin

The Red African Gray Parrot

The Hawk-Headed Parrot

The Dodo and the Guinea Pig

The Summer Duck of Catesby

George Edwards, born today in 1694, is known as “the father of British ornithology”—as fine a paternal legacy as a guy can hope for. Today, his reputation as a naturalist endures in no small part because of his excellent drawings, which introduced English readers to scores of exotic creatures: first and foremost, birds. His greatest work is the four-volume Natural History of Uncommon Birds, whose full august title deserves to be seen in toto: A Natural History of Uncommon Birds: And of Some Other Rare and Undescribed Animals, Quadrupeds, Fishes, Reptiles, Insects, &c., Exhibited in Two Hundred and Ten Copper-plates, from Designs Copied Immediately from Nature, and Curiously Coloured After Life, with a Full and Accurate Description of Each Figure, to which is Added A Brief and General Idea of Drawing and Painting in Water-colours; with Instructions for Etching on Copper with Aqua Fortis; Likewise Some Thoughts on the Passage of Birds; and Additions to Many Subjects Described in this Work.

These drawings are taken from that work, which you can read here. Of particular note is his illustration of the dodo, which was, even then, extraordinarily rare and facing extinction.

As for the man: According to The Aurelian Legacy: British Butterflies and Their Collectors, a contemporary of Edwards’s “described him as of medium stature, inclined to plumpness and of a cheerful, kindly nature ‘associated with a charming diffidence.’”

In Brief

From the cover of Liana Finck’s A Binkel Brief.

Dear Editor,

I am a Russian revolutionist and a freethinker. Here in America I became acquainted with a girl who is also a freethinker. We decided to marry, but the problem is that she has Orthodox parents, and for their sake we must have a religious ceremony. If we refuse the ceremony we will be cut off from them forever. Her parents also want me to go to the synagogue with them before the wedding, and I don’t know what to do. Therefore I ask you to advise me how to act.

Respectfully,

J. B.

Answer: The advice is that there are times when it pays to give in to old parents and not grieve them. It depends on the circumstances. When one can get along with kindness it is better not to break off relations with the parents.

You have probably heard of “A Bintel Brief,” the famous Yiddish advice column that ran in Der Forvertz, guiding several generations of newly arrived Jewish immigrants through the confusions of the new world. Penned by editor Abraham Cahan, the column, which has been anthologized, makes for evocative reading. It’s often heartbreaking and sometimes funny; the tersely definitive responses are compassionate and generally wise.

It was with great pleasure, then, that I came upon a copy of Liana Finck’s new graphic novel, A Bintel Brief: Love and Longing in Old New York. Finck illustrates a number of the “Bintel Brief” letters—from an educated young woman engaged to an old-world greenhorn; from a poor mother whose watch has been stolen by an even poorer friend; from a cuckolded husband—but she does more than that. She speculates about what might have happened to the writers. She illustrates unspoken byplay, read between the lines. She records her own reactions. In so doing, she brings an entirely new dimension to what has become, for modern readers, a portal into a world that feels impossibly distant. It is about nostalgia, yes—Finck would not have been alive when the column ran—but it is also about how we engage with the past. The letters alone feel like such an anachronism.

But are they? Funnily enough, I was reading through Finck’s book, which I have been meting out like a treat, when a friend sent me this. It’s gotten some exposure on Reddit, as one might expect.

There is one particularly moving letter that Finck chooses to illustrate, in which the survivor of a pogrom wonders whether to uproot his elderly father, now alone, and bring him to safety in America. Cahan wrote, “For various reasons we need to answer this heart-wrenching letter privately. The writer should send us his full address.”

Different Ways of Lying: An Interview with Jesse Ball

Photo: Joe Lieske

Jesse Ball writes novels and stories in the vein of Kafka or Daniil Kharms—surreal, often hyperpolitical constructions from contemporary life. His 2011 novel, The Curfew, whirls around an absurd dystopia, an uncanny avatar of our own. It’s home, but not quite. The Way Through Doors (2009) and Samedi the Deafness (2007) are set in neighborhoods at once eerily similar to and foreign from our own. To read Ball, who won The Paris Review’s Plimpton Prize in 2008, is to step into a kind of liminal space. And his new novel, Silence Once Begun, contains his most beguiling sleight of hand yet.

Silence Once Begun begins in a Japanese fishing town where eight people have recently disappeared from their homes. At a bar, Oda Sotatsu, an unassuming, lonely young man, wagers on a card game and loses to the mesmeric Jito Joo—Sotatsu signs a document that says he’s responsible for the recent disappearances. Jito Joo takes this confession to the police, and soon rumormongering and hearsay consume the town. Throughout his trial and imprisonment, Sotatsu remains almost completely silent, refusing to testify on his own behalf in court and barely engaging with the relatives who appeal to him. At the center of the novel, framing its various narratives, is a divorced investigative journalist named Jesse Ball.

Our conversations found the real Jesse Ball by turns serious and coy. We discussed the political value of plain speech, his near ascetic desire for isolation, and the necessity of lying.

Silence Once Begun demonstrates the failure of this town’s justice system, a failure to do right by one of their own. Another of your novels, The Curfew, also engages with unjust and inescapable social systems. Do you see your work as political?

Saying almost anything as well as you can say it, or doing anything properly and with your whole being, is a political act. And so I think almost any text that strives to have its own focus, without bowing to contemporary modes of humor or a little commercialism or whatever else—I think that’s very political. As long as everyone decides to hold and contain their own state, things improve.

My books, some of them appear to verge toward the political. This one certainly seems to be an indictment of a justice system. In the course of time, many things that appear certain within an epoch or an era seem ludicrous and silly to those in another time. However, plain clear speech, or questions stated within the power of the heart, don’t really become silly. They retain a certain power. In terms of attempts to write clearly, I think that’s the most political act.

When people would ask my father what his political beliefs were, or to write down whether he was a Democrat or a Republican, he’d always write down that he was, like, a Peter Kropotkin anarchist or something. There was also some obscure religious movement in England at one point that was called the Fifth Monarchists. I guess they believed the British king was the anti-Christ. My father would put that down as his religious affiliation. I think in some sense, that kind of contrarianism as always been in me.

So much of the book is about the politics of truth and truth telling. Sotatsu’s brother advises the reader to be wary of what their father says about Sotatsu—meanwhile, Sotatsu’s father says, “I am telling you things now that you can use.” What’s at stake in the competing narratives here?

I think a book is often an account, or a series of accounts, that create a world that is sort of half of the world. There are references to a world, and then the reader supplies the other fifty percent. So when you have multiple accounts that appear to be going in different directions, the reader is sort of vying with those and can create a very rich world, full of paradoxes or conflicting authorities and ideas. Ultimately, that’s a closer approximation of the truth of experience, what it’s like to live, than a single, supposedly objective account.

You’ve mentioned Kobo Abe as an influence. How does his very surreal vision of Japan come to bear on Silence Once Begun?

I don’t really think Silence Once Begun takes place in Japan so much as it takes place in this imaginary Japan, the one I’ve found in those novels—in Shusaku Endo’s books or Kobo Abe’s. It’s more like Kafka’s Amerika to America. It isn’t really America, so much as a fictional place.

The thing I like about Kobo Abe especially is how little compelled he feels to resolve things that don’t need to be resolved in his novels. There’s a great deal of, I don’t know, you could almost call it discomfort that comes in when you’re reading his novels, and I think it ends up being a bountiful kind of discomfort. Part of that is in being able to accept which things can in fact be determined. The larger consensus of culture wants to have this delirious speech that tells us that all these things can actually be known, can be determined, all these things are safe and the world is comfortable—when it isn’t at all. It’s like trying to patch an endless hole. You come up with some momentary truth that isn’t really a truth, which is what a lesser novelist would do. But not Kobo Abe. That’s one of the things I aspire to do, to not make any determinations where things should be left ambiguous.

You were a bit coy in the press material as to why your fictional journalist shares your name. But it’s obviously a significant choice.

You were a bit coy in the press material as to why your fictional journalist shares your name. But it’s obviously a significant choice.

At the time I wrote it, I was going through a difficult point in my life and it was just the easiest thing to have that character be Jesse Ball and not choose a different name. The book is a lot of plain speech, and the simplest spoon to dole out all of this plain speech with was just my own name. It’s an attempt to reconcile my experience of these painful events with the world that I hope exists.

What is that world?

It’s hard to put it into words. It’s a place where a person can have a meager place, and not be sent away.

In what sense?

Not be continually exiled from their small chair.

Do you value extreme isolation, then?

I probably like being isolated more than many people do, but I’m lucky to have the friendship of many fine people, and they keep me from becoming very isolated. The world of my mind is certainly a populated and warm place, too. It’s difficult for me to become too isolated with such resources.

I’ve read that you teach a course on lying. How does one do that?

It’s just a reappraisal of the general moral position that it’s wrong to lie and it’s right to tell the truth. That’s reductive and silly, since everyone lies all the time. Malicious lying is usually a matter of need, but often the cruelest things we say are the truth. My class goes through different ways of lying, and at the end, it’s not like students come out of it as expert liars. What they get from the class is that they can write more precisely without having this very weak idea about the morality of truth and lies—to not parody some idea that is very popular.

If we’re lying all the time, what are the things you lie about the most?

Well, I write lists about what I hope to accomplish. I would say my biggest lie is the spirit with which I write these lists, as if I’m certainly going to accomplish these things when it’s almost one-hundred percent clear that I won’t. And there are things I’ll put down on the list that I end up never accomplishing. I think the lies I make the most are in regards to my hopes and intentions for myself. As for lies I tell other people—I will certainly tell lies. When somebody is very ill and looks awful, and you tell them they look nice. Or if you just ate the last cookie, if someone asked me if I ate the last cookie, I would definitely lie about that. But I think the most common lie is when someone calls on the phone and you’re asleep. You almost always will say that you were awake. That’s because there’s maybe a puritanical ideal that we should always be laboring and doing good work, and we should never be caught asleep. But I would never say that I was asleep, whether or not I was.

Raindrops Keep Fallin’ on My Head

A still from Noah. Animals, ark not pictured.

Early in Darren Aronofsky’s new movie, Noah, the title character, played by Russell Crowe, comes across an antediluvian beastie, a cross between a dog and an armadillo. The beastie snarls because there’s a broken-off assegai tip in its flank, but Noah wins its trust and soothes it before it expires. Since Noah is famous as the Biblical patriarch who saved animals, a moviegoer might be forgiven for looking forward to more such scenes of human-animal interaction. Will there be an explanation about why the dogadillo didn’t make it on to the ark? Will Noah have to talk a lioness out of disemboweling an okapi on board? Will there be trilobites?

Uh, no, it turns out. Pairs of animals do stream onto Aronofsky’s ark under divine instruction, as calmly and trustingly as if Temple Grandin had designed their on-ramp, but once the creatures are in their berths, the Noah family wafts a censer of magical burning herbs, and presto, change-o—all the animals fall asleep. One of the most charismatic elements of the Noah story—in the opinion of most people under the age of six, the most charismatic element—is quietly euthanized. A stowaway descendant of Cain, looking very much like an escapee from Pirates of the Caribbean, does bite the head off of a dormant rodent and gnaw upon it with much sententious commentary, and a few implausible-looking CGI birds are deputized to scout for land, but apart from these brief episodes, the ark might as well be empty.

Aronofsky’s difficulty with animals is oddly systematic. He gets pretty much everything about the Biblical history of vegetarianism wrong. In the movie, descendants of Cain kill and eat animals with gory glee, a sign of the sinfulness of their tribe. In fact, though, Cain was into vegetables. Cain offered God the fruits of his fields—his trouble was that God preferred the smell of his brother Abel’s offering of burnt livestock (mmm, bacon). Aronofsky also garbles Noah’s position on the question. In the director’s telling, Noah abstains from meat as a matter of sensibility as well as principle. In the Bible, however, Noah is the world’s first meat eater. Everyone was vegetarian before the Flood. Not long after the ark settled on Mount Ararat, God gave Noah the right to eat animals as well as exercise dominion over them. God doesn’t quite say why, but the implication seems to be that once Noah demonstrated responsibility for the animals, he could be trusted with a new authority over them.

But only one aspect of the natural world seems to interest Aronofsky: the survival of humans. The movie’s most egregious distortion comes in an early intertitle, when the descendants of Cain are said to have created an “industrial civilization” that God thinks it best to destroy. The Bible does mention a Cain descendant known for metallurgy, but industrial civilization is no older than the eighteenth century, and it seems patent that Aronofsky is playing on the contemporary audience’s fears of how human-generated climate change might end the world as we know it.

Hollywood being Hollywood, Aronofsky makes those fears personal. In the Bible, Noah’s three sons board the ark with wives of their own. In the movie, only one of his sons has a wife, and she’s barren, and Noah is under the impression not only that God intends for the human race to go extinct but that it’s Noah’s job to make sure it does. Aronofsky assimilates Noah’s story to the story about Abraham and Isaac; the conservationist turns out to have it in for his own species and even his own germ line. Tearful pleas to Noah ensue: let there be grandchildren.

I confess that as a middle-aged vegetarian homosexual who is not interested in adopting, I found the urgency that the movie purported to feel about this issue calculatedly spurious. Not eating meat, not having children: in my personal experience these are not choices that cause much, or even any, anxiety in daily life. The actor playing Ham is exceptionally foxy, but sorry as I was to imagine that he might not convey his genes to a later generation, I couldn’t get that worked up about the personal angle. Don’t you want our sons to be happy? Noah’s wife wails, evidently having failed to read any of the New York Times articles about how marital happiness drops significantly after the first child and precipitously after the second.

When she adds that she couldn’t bear the thought of her youngest son dying alone, it seems a low blow to the unpropagated in the audience—but not a blow that necessarily hits home. Dying is going to be unpleasant for all of us, and I for one am not sure it won’t go better if unobserved. I should clarify here that I might well be induced to find the end of the human race troubling. But if I did, it would be because such a termination would undermine the meaningfulness of many human endeavors, even those by people like me who expect to have no descendants. Not because I personally, or anyone else personally, would lack descendants. It’s arguable, in fact, that the human cause is furthered if some of us choose not to procreate. Noah was incapable of such abstractions. Watching it came to feel, after a while, a little like having dinner with a carnivore who keeps asking for reassurance that I don’t disapprove of his ordering fried chicken. Eat your chicken, have your babies. Let me eat my lentils in peace, and let’s talk about something else.

Is there any ideology in the mishmash? The flavoring of the movie is from a venerable populist recipe: push radicalism to a discrediting extreme, then pull the viewer back, with sentiment, to the comfortable middle-of-the-roadism that he began with. Maybe there’s a clue in the movie’s most notable invention, the Watchers. These are animated congeries of boulders with glowing eyes, said to be fallen angels who regret having helped humans create the aforementioned industrial civilization. The Book of Genesis does mention giants, whom I always understood as introducing a modicum of exogamy into a storyline that otherwise implied rather a lot of incest, but Aronofsky’s Watchers are concerned with production rather than reproduction. It’s largely they who build the ark. Did Noah need their help? He lived more than six hundred years; he had plenty of time on his hands for labor. Why would it be hard to believe he could build an ark? Why would it be any harder than believing in, say, the unexplained, spontaneously occurring granola that his family seems to have no shortage of?

Aronofsky thought his Noah needed Watchers, to judge by the screen time he gives them. They’re animated in a style that looks like it’s of Davey and Goliath vintage. Maybe they represent the assistance of computerized imagery in moviemaking: Their aid, when first introduced, expanded human power, but the power has enabled the greedy among us to lay waste to the world, until today, when, under an inspired leader … You know the drill. The movie becomes a parable of video-gamification, as so often happens with science fiction these days. The old world of nature will be recreated in a new ark of technology. In the event, though, the technology-created world never does resemble the one it replaces. The technologists can’t resist taking a bite of the apple of improvement. The structure is made a little larger. The animals are more securely immobilized. They’re packed in more tightly. And pretty soon it’s hard to tell the difference between an ark and a factory farm. Try some of the squirrel.

Caleb Crain is the author of Necessary Errors.

Printing Wikipedia, and Other News

“Printers,” from the Trousset encyclopedia, Paris, 1886–1891.

Spotted in the Times: our very own Sadie Stein (and her apartment) paying tribute to Laurie Colwin.

A German publisher wants to print Wikipedia—all 4,484,862 articles of it. The omnibus “would fill a bookcase that’s 32 feet long and 8 feet high. But not everyone thinks it’s a good idea.” I can’t imagine why.

Have we failed to utilize effective incentivizing techniques to promote greater linguistic clarity? In other words, are we losing the war against jargon?

The photographer Nancy Warner takes wistful pictures of abandoned farmhouses on the Great Plains.

In 1937, Richard Nixon applied to be a special agent in the FBI. He was not accepted. In a letter of recommendation, the dean of Duke Law School wrote that Nixon was “one of the finest young men, both in character and ability, that I have ever had the opportunity of having in classes.”

Want fast Internet? Go to the darkest depths of Norway, where there are more polar bears than people.

April 2, 2014

Prized

We’re pleased to announce that two of our stories have been selected by Jennifer Egan for this year’s Best American Short Stories collection: Benjamin Nugent’s “God,” which appeared in issue 206; and “Hover,” by Nell Freudenberger, from issue 207. Their stories will appear in an anthology to be published in October.

We’re pleased to announce that two of our stories have been selected by Jennifer Egan for this year’s Best American Short Stories collection: Benjamin Nugent’s “God,” which appeared in issue 206; and “Hover,” by Nell Freudenberger, from issue 207. Their stories will appear in an anthology to be published in October.

We also have nine nominees for this year’s Pushcart Prize:

David Searcy, “Mad Science,” issue 204

Ottessa Moshfegh, “The Weirdos,” issue 206

Susan Stewart, “Pine,” issue 207

Kevin Young, “Three Poems to Amy Winehouse,” issue 204

Stephen Dunn, “Feathers,” issue 204

Ben Lerner, “False Spring,” issue 205

David Gates, “The Curse of the Davenports,” issue 205

Kate Levin, “Dirty Parts,” from the Daily, July 2013

LuLing Osofky, “Kent Johnson’s / Araki Yasusada’s / Tosa Motokiyu’s “Mad Daughter and Big-Bang,” from the Daily, May 2013

Congratulations to all!

The Set

William Evans Burton, comedian. Illustration from Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, February, 25, 1860.

The problem is the beaming. For whatever reason, I frequently boast a huge smile when in public, and as any city-dweller will tell you, this is a bad idea. I may be grinning about a doll, a muffin, a soda label. “She’s mad happy,” a teenager once remarked to another as I passed their school.

Yesterday, at the Ninety-Sixth Street subway station, I know exactly what I was smiling about. I had overheard one woman remark to another, “As soon as we get to the baby gym, all he wants to do is take off his pants and get on the trampoline.” It was all I could think about as I prepared to see my psychiatrist—specifically, I was thinking that this was utterly reasonable on the (presumed) baby’s part, and that if I ever found a gym where de-pantsing and jumping on a trampoline was SOP, maybe I would join a gym. And all of which would have been fine, if I had not been the only person grinning while everyone else avoided the eyes of the man strolling down the subway platform.

Whether he was homeless or not, I cannot say. Drunk? Perhaps. Certainly not completely well, as society defines such things. In any case, he, like me, seemed delighted. And when his twinkling eyes met mine, he recognized a comrade-in-arms.

He parked himself in front of me, and said, “Who’s the only man in America who cares? Obamacares!”

I wasn’t sure what to say; but nothing was required. It soon became clear that this was not a mere political endorsement, but the first bit in a topical comedy set.

“America’s the only country in the world where you get to pay to be poisoned with radiation!” he said, staring fixedly at me.

I saw no alternative but to continue grinning and nod my head encouragingly. No one else on the platform seemed to agree.

“How do you know radiation is killing the cancer?” he demanded. “Because you’re dying!”

I didn’t think his material was very good, but the delivery was excellent.

The train pulled into the station and I boarded, giving him a friendly nod of farewell. I sat down and—there he was before me.

“America’s the only country in the world,” he said, “where doctors staple your stomach shut. I’ve got an operation for you: stop eating! Give me a million dollars!”

I had, myself, signed up for insurance not a week prior. I had paid a little extra for some mental-health benefits. Prescriptions are expensive, but as I always say to the pharmacists, you wouldn’t want anything cheap in your brain.

“America’s the only country in the world where the food in the hospitals makes you sick,” said the comedian. He tipped his hat to me and exited at the next express stop.

The young guy across the aisle met my eye now, and gave me a weary, conspiratorial look. “Crazies,” he said, sympathetically.

“You have no idea,” I said.

Sit on It

The art of sploshing. (Contains mildly NSFW photography.)

© Martha Burgess

The Friday night before last, on an otherwise abandoned block in Gowanus, I spied a young man and woman; she was carefully carrying a plastic bag that contained a boxy package. “Are you here for the sploshing?” I asked. They were. I followed them to their destination—Trestle Gallery, a nonprofit art organization affiliated with Brooklyn Art Space, on the first floor of a building that once housed factories. Was it their first time sploshing? I wanted to know. It was. And me, would I be participating, too? No. I was only there to watch.

I’d learned of artist Martha Burgess’s “Cake Sit” a few months prior, over dinner at Omen, the serene, Zen-like Japanese restaurant on Thompson Street. The novelist Monique Truong, whose Book of Salt I often cite as one of the best examples of food writing, turned to me and asked, with wide-eyed excitement, “Have you heard of cake splooshing?!”

Although I spend an inordinate amount of time writing, thinking, and talking about cake, to say nothing of eating it, this splooshing, as Truong called it, was new to me. People, she explained, sit on cakes and get off on it.

Cursory research revealed that sploshing—the correct spelling—is, indeed, a thing, and that there’s a specific cake version thereof. Burgess herself mentioned a 1928 precedent in George Bataille’s Story of the Eye: “I first saw her mute and absolute spasm (which I shared) the day she sat down in the saucer of milk.” But Truong found a direct reference in Tove Jansson’s 1946 Comet in Moominland: “‘There you sit on our cake,’ said the Snork Maiden. Then the Muskrat got up, and, oh, dear, you never saw such a mess as there was on his bottom. And as for the cake … ‘Now I shall be sticky for the rest of my life, I suppose,’ said the Muskrat bitterly. ‘I only hope I can bear it like a man and a philosopher.’”

On its own, the act of plopping one’s posterior on a beautifully frosted, possibly delicious dessert didn’t intrigue me. If anything, I was horrified by the idea of wasting of a perfectly good cake on something as fleeting as taking a seat. The pleasure principle was intriguing, but only in theory. Who wants to get crumbs up one’s bum or sticky icing on one’s pants?

What did interest me, and enough to want to see the perverse paradise in person, is Burgess’s appropriation of the fetish for a public, communal performance project. Over tea a week later, the artist, who identifies herself as “the tree that fell in the forest,” explained that in this current show, “Performing Audience,” she experiments with “the distinctions between artist, audience, and art institution—blurring all those boundaries.”

“You know how many artists say, It takes the audience to complete the work of art?” she asked. “I just wanted to speed up that process a bit.”

Back in Gowanus, I trailed Arcadia Hartung, whose name I’d learn later—after I’d dubbed her “Fabulous,” because that’s what was printed on the back of the underpants she wore when she lowered her bum into her cake—and her friend up a flight of stairs and into the small, bare-walled exhibition room. Along the way I found out that she’s a former intern of Ms. Burgess’s; that neither she nor her plus-one had ever (deliberately) sat on a baked good before; and that she had bought—not baked—the cakes in her bag.

© Martha Burgess

Close to thirty people had gathered in the gallery, and the space was charged with an upbeat, excited energy. The artist, head down, camera in hand, was having an intense conversation with the videographer, whose equipment was smack dab in the center of the room. Ahead of them was what constituted the proscenium: a bare wall covered in butcher paper, in front of which stood a Donald Judd–inspired purple rectangular cardboard construction. The first round of sploshers had already begun to place their cakes on this bench; Ms. Burgess rearranged them according to her aesthetic preference. Sitting atop the bright, violet surface, the single-file line of confections looked like a Wayne Thiebaud still life.

Standing “offstage,” Truong waved me over and introduced the poet Barbara Tran, a friend of Burgess’s who had agreed to perform that evening. She was wearing bright red pants, which she’d bought for the occasion; they matched her cake, which she’d baked using a box mix of strawberry batter. The finished, layered product was covered with textured swoops of white icing and dotted with tiny red-hots. She was going for a Roy Lichtenstein Ben-Day effect. Tran was wondering what sort of frosting made for optimal sploshing—for whatever reason, she’d decided chocolate was not as cushy. Buttercream, she presumed, was better than ganache.

A few minutes later, nine people, including Tran, stood on the other side of that cardboard barrier, each participant behind his or her respective cake. It looked like a police lineup for pastry thieves. Burgess snapped their photos. Then she had them walk out in clusters—four, two, or one at a time—to engage in the act itself. Four of them came. They sat. It was done. Burgess asked them to stay, plonked down and sinking into their cakes, so she could take photos. While they waited, a few of them stuck their fingers into their cushions and tasted. After they stood up, Burgess photographed the strangely beautiful sculptures they’d left behind.

“Regarding the encounter between a human’s hindquarters and a cake,” she explained, “I’m drawn to the object that is produced as a result of the process, and I feel that this result may be more important than the accident itself.” As for the process, Burgess believes it’s “not unlike printmaking—one’s ass being potatoes.” This irreverence is part of her MO. The act, she says, is “sensual and silly and goofy and very sweetly bad … I don’t think of it as waste so much as an act of rebellion.”

© Martha Burgess

Truong saw rebellion, too. “The moment that Barbara, in her bright red pants bought especially for the occasion, flattened that cake, I was experiencing the cathartic thrill of destroying all the birthday cakes belonging to my little first-grade classmates … So maybe for me, the cake sit—her cake sit—was like the burning of an effigy, the cake a stand-in for an awful childhood, except a cake sit was incredibly fun.”

Charlotte Druckman is a journalist and editor whose food writing has appeared in the Wall Street Journal, T: The New York Times Style Magazine, and Bon Appetit. She is also the author of Skirt Steak: Women Chefs on Standing the Heat & Staying in the Kitchen.

Proof of the cake sit is on display at Trestle Gallery through April 4, in the form of Burgess’s photographs.

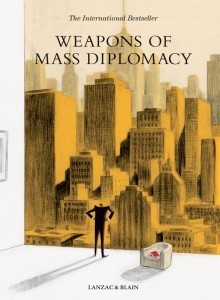

Heroes of the Civil Service: An Interview with Antonin Baudry

Antonin Baudry, 2013. Photo: Clarisse Rebotier

In 2010, a graphic novel, Quai D’Orsay, was published in France under a pseudonym, causing a quiet sensation. Set in, of all places, the Foreign Ministry, Quai D’Orsay starred a young speechwriter frantically learning on the job—the novel featured recognizable public figures, including the foreign minister, Dominique de Villepin, who famously said non to the war in Iraq.

In France, graphic novels, or comic books (bandes dessinées), are a revered venue for pointed satire. The bestseller’s author, it turned out, was a wunderkind former staffer for Villepin named Antonin Baudry. A man of varied passions—board games, Metallica, Greek philosophy—Baudry is currently the French Cultural Counselor for the U.S. Last fall, he adapted the graphic novel for the big screen. The resulting film, The Minister, became an instant hit in France, earning the rookie screenwriter a nomination for a César, the French Oscar. The Minister is now showing (under the title The French Minister) at select theaters in the U.S., including the IFC Center, in New York; the graphic novel is available in English under the title Weapons of Mass Diplomacy.

Sitting in his cavernous office in the French embassy, overlooking Central Park, the informal diplomat says he would love to try another graphic novel “on globalism, set in the Middle Ages.”

Both in the graphic novel and the movie, you make it seem as if you hadn’t the slightest qualification to write speeches for the foreign minister. Is that true?

Yes. I didn’t have the background that all the people there had at all. I had never met a politician before. I had never met a diplomat. What happened was that Dominique de Villepin was looking for young people from different universes to write for him. He heard through a mutual friend that I had done master’s theses in math and literature, and he wanted to meet me. I totally panicked. I said to my friend, Why did you do this to me? I had to buy a suit. The minister received me at the Quai D’Orsay, and it was just like being hypnotized. He explained a lot of things to me and everything seemed clear, and then when I left, I couldn’t remember a thing. And there was this time pressure. He said I had to answer within twenty-four hours because we were possibly on the eve of a Third World War. I was twenty-six, and I thought, Why not? I’d done academic writing and I knew I wanted to write novels. I accepted the job because I think many writers have no experience of the world. I once worked for the sanitation department in Berlin, cleaning the streets at five in the morning. I loved it for the same reason—it gave me the chance to observe another universe instead of staying in my room, contemplating myself.

The minister is a very endearing character. Can you describe the man who inspired him?

I love de Villepin. We’re still friends. I have a lot of admiration and tenderness for him. He made me suffer a lot, but I was a consenting victim. He’s a very, very smart person who has some madness in him. And he’s aware of it—he plays with it, he believes it’s necessary. And I agree. If he weren’t as he was, France wouldn’t have said, Non, we won’t participate in the Iraq War. The process leading up to that was chaotic and very strange, but the decisions, and the results, were rational. That’s what I wanted to show in the book and in the film—how irrational processes can lead to rational results. It’s a Hegelian story. As Hegel says, the owl of Minerva only takes flight at dusk. It represents wisdom, which appears only after the day is done. You can’t understand the logic of the process, but there is one.

Did speechwriting teach you anything useful about fiction writing?

It taught me a lot as a writer. It made me realize that you never know exactly who is writing. It’s a mix of voices in your head, and you have to hear them all and choose, somehow. Each word is a battlefield.

How was it different, speechwriting?

Well, it’s not writing. It’s understanding a situation, what words it needs. It’s collecting a lot of information about what’s really at stake. And then a major part of the work is trying to understand how everyone will interpret what you write. The Americans will interpret these words in such a way, the Iraqis will interpret them differently, and so will the British. You’re talking on different levels to different people.

One of the painful things to watch in the movie is how the young speechwriter’s hours of work are dismissed with one word, and he has to start all over.

Yes, the first time, it’s really surprising, and you’re disappointed, but then it becomes part of the game. You’re interacting with so many people, taking into account so many different points of view and egos. It’s like being in a washing machine. There is no rational way to deal with it, to be honest. But the idea that you can write something, work really hard on it, and then cast a cold eye on it, throw it away, and start from scratch—and consider that part of the normal course of things—is useful for any writer.

What made you decide to tell this story as a graphic novel?

I had the feeling that many of the things I wanted to say were better conveyed visually. The same interactions that would appear heavy-handed in writing could be described elegantly with a single image. What I tried to do in the graphic novel was not to imitate the people it’s based on but to develop an equivalent for each. For example, the minister has this big nose with a narrow head and weird hair. It’s really not Villepin at all. But it’s an equivalent—people recognize him somehow.

How was writing for a graphic novel different from writing for a film?

When I worked on the comic book, I was standing right next to the artist. At the end of the day, I could really see what I’d done—you have immediate feedback, and you can change things. When you’re making a film, by the time you discover the visual results of the decisions you’ve made as a writer, it’s totally too late to change them. As a screenwriter, you have to be very experienced to understand the onscreen consequences of what you’re writing.

When the graphic novel first came out, you went under a pseudonym, Abel Lanzac. I found an interview from your incognito period. All you revealed was that your wife was the reincarnation of an Egyptian princess and that you didn’t like roasted endives.

When the graphic novel first came out, you went under a pseudonym, Abel Lanzac. I found an interview from your incognito period. All you revealed was that your wife was the reincarnation of an Egyptian princess and that you didn’t like roasted endives.

I showed the storyboard to one of people who inspired the book, the minister’s chief of staff. He laughed a lot and said there was no problem with publishing it at all. His one piece of advice was to take a pen name so I could write whatever I wanted and wouldn’t have to ask for authorization as a diplomat. But it didn’t work, because my publisher sent out a press release, which said, “This book is by Abel Lanzac (pseudonym).” If you indicate that it’s a pseudonym, it doesn’t work. So I decided to drop the pen name.

Speaking of the chief of staff—who appears in the book and film—does such a perfect human being really exist?

Yes. Pierre Vimont. He was unbelievable. That was a true discovery for me—the genuine public servant, totally dedicated to the state and the common interest. He worked so hard. He would leave the office at three in the morning and be back at seven. He was always under extreme pressure, which he never, ever transmitted onto others. He was so calm, so kind, and so smart. Two things were impossible with him. One was preceding anyone through a doorway. I tried every way I could think of to let him go first. The second thing was to give him a piece of information he didn’t already have. That was impossible. I don’t know how he did it. One night I was on night duty at the ministry. You’re the one who monitors all the information coming in and you have to decide what’s important, whether you have to wake someone at night. There was a negotiation about a cease-fire between the Israelis and the Palestinians. I received a telegram at two A.M. that said the deal was done. I immediately rushed into his office to tell him. And he said, Yes, I know. It’s great news. I thought, How does he know? He’s not on the phone … He was always like that. He always just knew. He’s a hero to me.

That was the radical suggestion of the book and the film. Not only were these civil servants not jerks, but they were heroic.

Totally. French people are always saying that civil servants don’t work and are always on holiday. France is a country that criticizes a lot, which is a great cultural tradition. But I know so many people in government who work hard all their days, sacrificing their personal lives. I’m happy they’re in charge. I wanted to show that. It’s a satire, but a very tender one.

The other supporting character who steals the show is Heraclitus, the Greek philosopher—from the fifth century B.C.

My wife is a specialist of Heraclitus. She teaches at Columbia. Her field is the representation of the Greek philosophers in seventeenth-century Spanish literature. So Heraclitus and Democritus are living on our sofa. I like this idea that you have two main attitudes in life—Heraclitus, the one who cries, and Democritus, the one who laughs. If you don’t try to be too intellectual, those are the two possibilities you have when you’re facing situations. Laugh or cry. That’s why I wanted him as part of the show. Not only for his comments about life, but also for his distance from the world. He’s always represented in his garden, his back to the city, looking out from a distance and crying because it’s too sad to see how men live their lives.

What was it like to hear Villepin give the speech you worked on, defying the United States over the Iraq War?

In France, everybody pretends now that we were against this war, but it’s not true at all. The vast majority of the French elite, including the left-wing intellectuals, were trying to convince Villepin to follow Bush. When I heard him deliver his speech, I cried. I knew it was important. But I also knew that it wouldn’t stop the war. Those are the limits of speeches, the limits of debate, the limits of the pursuit of truth.

Getting back to heroic civil servants, I hear you saved the French embassy in New York from being sold.

I made a counter offer, which was to open it to the public with the specific idea of having a French bookshop with fifteen thousand books. It’s a not-for-profit. It’s not even going to look like a retail place—it’s designed to look like a grand private library. No commercial displays or aggressive lighting. You can buy books, but you can also just sit on the sofa and read them. Part of the concept is to create a French-American venue for international debate, to invite the most original writers in the U.S. and Europe to discuss art and finance and politics. We’re going to have a literary festival curated by Greil Marcus.

A page from Weapons of Mass Diplomacy.

It’s the last building Stanford White designed. Actually, he was shot dead by a jealous husband while he was working on it. It was a gift from Colonel Whitney to his nephew, who was getting married. The Whitney family lived there for thirty years, then sold it to an German actress. Then Claude Lévi-Strauss, the French ethnologist, was appointed by General de Gaulle as the first cultural counselor to the U.S. He saw the building and convinced France to buy it.

Is it true there’s a Michelangelo statue in the lobby?

Yes. Stanford White went to Italy to get the marble for the building, and he came back with this statue and stuck it in the lobby. Everyone thought it was just some statue. They put their ashtrays on it. Then one day, twelve years ago, the director of the Institute of Fine Arts at New York University came by and asked about it. The staff thought it probably came from the streets of Florence, but the director said, Actually, I’m pretty sure it’s a Michelangelo. She paid for a survey by the Met. Their verdict was that there’s a ninety-five percent chance that it’s Michelangelo. There was a huge panic in the French administration, who wondered how they were going to insure it.

Without causing a diplomatic incident, do you have any observations to make about the natives here?

I love them.

Why?

I’ve never met so many interesting, unique, and intense people as I have during my travels across the United States. Here, it’s much more common that people do a lot of things in one single life. It’s less common in France—people go in a single direction very deeply there.

Go on. What are some of our other strengths?

Your self-confidence. And your belief that everything is possible, which is beautiful.

Do you really recite Descartes every night?

Descartes, for me, is an American. He’s supposed to be so French. We tend to reduce him to Cartesianism, with its boring rational approach. It’s not that. He also thinks everything is possible. If you can think it, you can do it. You just have to make good decisions. If you’re lost in the forest, what do you do? He says just choose a direction and stick to it. I think that’s a very American way of thinking. We live in a world of insanity, but let’s not procrastinate. Let’s make a decision, the most educated one we can make, and let’s go for it. That is very American. That is not so French! Descartes is the secret conduit between the French and American spirits.

Poets Want Their Privacy, and Other News

Smile, you're on CCTV.

“Delicious, unkosher, dark, vague, the Cloud / Of Mexico Pork threatens our borders.” In a new forum, John Ashbery, Cathy Park Hong, Charles Bernstein, Robert Pinsky, Rae Armantrout, and others contribute poems about the surveillance state in the twenty-first century. (Those lines are Pinsky’s.)

Good news for grad students reluctant to enter academia: “Humanities Ph.D.s are all around us—and they are not serving coffee.”

The Mets blew what now? An unfortunate headline teaches us the everlasting value of commas.

Anyone who worships at the altar of user experience will wince at these designs by Katerina Kamprani, who has made it her task to suck the utility out of everyday objects.

One man’s strangely inspiring search for a vocation: “He started the Restroom Association of Singapore to clean up the public toilets. People loved it. He then realized there were fifteen toilet associations around the world, in cities in Britain and Germany and Japan and some other places, too, but no world headquarters. So he started the World Toilet Organization … and that is how Jack Sim became the Toilet Man.”

A brief history of naked babies in fashion magazines.

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers