The Paris Review's Blog, page 718

April 9, 2014

The Cat Came Back

Detail from the poster for Disney’s The Incredible Journey, 1963.

Yesterday, a dog raced a Metro-North train from the South Bronx into Manhattan. The train slowed down at several points so the dog, an adorable shepherd/collie mix, would not risk injury. Passengers feared for her safety during the mad dash—and cheered lustily as she was collected by two transit cops, who took her to animal control to treat her injured paw.

We love to see pets going to great lengths for our companionship, or whatever it is they’re doing. It’s hard enough to know what your dog or cat is thinking as it goes from room to room—and no one can divine the thoughts of these heroic specimens who follow their masters across continents, Incredible Journey–style. We usually choose to regard this as proof of pure devotion. But in other cases, we see these antics—especially by cats—as slightly sinister. Consider the case of “The Cat Came Back.”

Written in 1893 as a minstrel song with a very different title, “The Cat Came Back” tells of a malevolent cat who won’t stay away—until he’s killed. It’s not the sort of enlightened fare we usually associate with modern elementary education. And yet, a sanitized version of the song is a staple of nursery schools and day camps, where it’s seen as a useful tool for teaching young children about rhythm and harmony. For whatever reason, kids love the minor-key tune and the story of the grim, Mephistophelean cat.

There’s a G-rated modern version in which the owner tries to pawn the cat off on Santa Claus and an air balloon; and then there’s an earlier iteration, in which said owner clearly wants to see the feline dead. Kids laugh at both, because this cat will not be ruled by man. He defies adult authority—to say nothing of the laws of physics and geography—and this is as reassuring as it is terrifying. He “couldn’t” stay away, we are told—but not because he so loves the beleaguered Mr. Johnson, or Wilson, or whatever the owner’s name happens to be. He is a law unto himself. And the glee in telling his story has little to do with affection, and much to do with things dark and unexplained.

If no owner claims that train-loving dog, animal control is going to put her up for adoption, even though her heart is clearly wild and free and her thoughts inscrutable. But maybe for someone, that will be an adventure. Maybe they’ll like the minor key of its small mysteries. And why take on another life, if not for that?

Infinite Reality

Reviving the art of Turkish miniatures.

Goodfellas, drawn by Murat Palta in the style of traditional Turkish miniatures.

In Turkey, people used to yawn when they heard the word miniature. “He looks just like one of those guys in miniatures” was a good way to insult someone. Generations of students have learned to ignore, or dislike, the art of miniature and the broader category of traditional Turkish arts—tezhip, the art of illumination; ebru, paper marbling; cilt, bookbinding; and hat, calligraphy. After all, uncool people practiced them—better to keep one’s distance.

Miniature paintings date to the third century A.D. They’re small paintings used in illustrated manuscripts (decorated books, basically) to depict scenes from the classics: the Iliad, the Aeneid, the Bible. Illuminated bibles—like the Syriac Bible of Paris, believed to have been produced in the Anatolian city of Siirt—helped spread the message of God. In Asia, miniatures developed into an independent art form, with techniques quite distinct from those of Western painting. As Wikipedia says, in Persian miniatures,

walls and other surfaces are shown either frontally, or as at (to modern eyes) an angle of about forty-five degrees, often giving the modern viewer the unintended impression that a building is hexagonal in plan. Buildings are often shown in complex views, mixing interior views through windows or “cutaways” with exterior views of other parts of a facade … The Ottoman artists hinted at an infinite and transcendent reality (that is Allah, according to the Sufism’s pantheistic point of view) with their paintings, resulting in stylized and abstracted depictions.

Kamāl ud-Dīn Behzād was one of the most prominent practitioners of Persian miniatures. His Construction of the fort of Kharnaq, as well as Reza Abbasi’s Youth Reading, are among its most beautiful examples; both can be found in the British Museum. In the Ottoman empire, the miniature flourished as an art form during the reign of Mehmed the Conqueror. Traditional miniaturists didn’t sign their work. Some of the best known of Ottoman miniatures were produced collectively in Topkapı Palace, where people worked without a sense of individual authorship.

The modern distaste for miniatures was prevalent among the educated classes, whose most common grievance had long been that Turkey never had a Renaissance—we didn’t have a Medici family to commission great art. When Mehmed the Conqueror took Istanbul, scholars and artists fled to Rome, bringing their expertise and knowledge about antiquity to Europe. As a consequence, we were taught, Turkish artists were condemned to produce examples of these boring traditional arts. Had they learned the technique of perspective from their European masters, Caravaggios and Rembrandts would’ve popped up throughout the empire like fresh daffodils.

This self-deprecating mood changed briefly in 1998, when Orhan Pamuk published a novel called My Name Is Red, which showed hundreds of thousands of bemused Turkish readers that miniature art was not only worthy of interest but also cool—even sexy—in the age of postmodernism. In Istanbul, the long history of Ottoman miniatures quickly became the talk of the town; when, in 2001, John Updike praised the novel in The New Yorker, the excitement grew. In other words, it was only when Americans showed interest in our traditional arts that middle-class Turks decided to take a closer look.

The American-founded Bosphorus University opened ebru classes where hipsters and prospective intellectuals met and made marbled papers together. A left-wing record label, Kalan, started putting out albums by traditional composers. Kids started showing interest in the ney, a kind of Middle-Eastern flute, and a heavy metal band started performing songs by Âşık Veysel, an Anatolian incarnation of the wandering minstrel. But this interest waned in the 2010s: once again, traditional arts came to be seen as unfashionable relics. There seemed to be no place for them in the digital era.

Pulp Fiction

Then, in late 2012, a young graphic designer named Murat Palta created a portfolio for his college thesis. He wedded the miniature to contemporary movies, making a gallery of miniaturized films including Clockwork Orange, Goodfellas, Inception, Kill Bill, Pulp Fiction, Scarface, Terminator II, The Godfather, and Star Wars. The miniatures, like Palta’s other works, are funny, ironic, and beautifully drawn. It would be difficult—and wrong—to place his work somewhere on the continuum of tradition and modernity; it’s at once reverent and irreverent. He put his miniatures on his Bēhance page, where they were viewed almost a million times.

In Ottoman miniature, there’s no sense of perspective or linear narrative. Everything happens on the same flat surface before the all-encompassing gaze of infinity. So Palta’s miniatures remove the movies from their chronological context—the climactic moments are presented all at once. Just look at his miniature for The Shining, where he captures Danny’s encounter with the ghosts of the murdered twins in the same frame as Jack Torrance’s chopping at the door with a fire axe. Miniatures have a different way of editing reality: What better way of showing the frenzy of the Overlook Hotel than picturing it as an infinite madness where the Western understanding of time no longer applies?

Detail from The Shining.

Palta isn’t the only one helping to revive the moribund form. Derviş Zaim, a Turkish director famous for his translation of traditional Ottoman arts into the medium of film, made use of miniatures in his 2006 film, Waiting for Heaven, which is about a miniaturist and embraces the miniature aesthetic. Zaim used a special color palette and arranged the scenes in such a way that they represent the strange, achronological principles of miniatures, as he describes in an interview with Cinema Without Borders:

The space and time in the classic miniature painting is used in a different way, maybe in a cubist manner. I am not suggesting that Ottoman Classical miniature artists are an early example of cubism … [but] Ottoman miniature artists may use x time and y time side by side in order to create richer, broader explanations and narration. They may also use z location and f location side by side … by doing this, they will problematize the space and time like cubists do.

Almost two decades have passed since I first heard my history teacher complain about how “Turkey didn’t live the Renaissance.” Perhaps what Palta, Zaim, and Pamuk have accomplished in their work is our own Renaissance—a rebirth of our lost traditions for a modern audience.

Kaya Genç is a novelist and essayist from Istanbul.

How the Future Dressed in the Past, and Other News

This is how one man in 1893 thought we would dress in the seventies. Image via the Public Domain Review

The CIA used many strange tools to fight the commies. One of them? Doctor Zhivago . According to a CIA memo, “This book has great propaganda value … not only for its intrinsic message and thought-provoking nature, but also for the circumstances of its publication: we have the opportunity to make Soviet citizens wonder what is wrong with their government, when a fine literary work by the man acknowledged to be the greatest living Russian writer is not even available in his own country in his own language for his own people to read.”

Remembering the poet Ian Hamilton and the New Review, which was, “depending on your point of view, either the best literary periodical of the past fifty years or an elitist folly lavishly bankrolled by the taxpayer.”

In 1893, W. Cade Gall published the “Future Dictates of Fashion,” in which he speculated as to the garb of years to come, all the way up to 1993. His conjectures were … wildly inaccurate.

Difficult-to-parse news item of the day: “A 49-year-old Santa Cruz man died late Thursday night while crossing Mission Street after being struck by a car.” “Pretty plucky of him to cross the street after he had been hit, I thought.”

Damien Hirst is writing an autobiography. “It will include a barely known first act—a black and hilarious account of Hirst’s youth, growing up in a semi-criminal, often violent milieu, while sharing with his friends an unlikely, but binding passion for art.”

April 8, 2014

“Arabia”

Tonight, at our Spring Revel, we’ll honor Frederick Seidel with the Hadada Award. In the weeks leading up the Revel, we’ve been looking back at the work Seidel has published in The Paris Review throughout his career.

A sunset in Zanzibar. Photo: hobbs_luton, via Wikimedia Commons

When I first read “Arabia,” which appeared in our Summer 2011 issue, I was sitting on a rickety chair looking out at Lake Michigan. It was a gorgeous day in late June, a twenty-one-year-old was cat asleep at my feet, and I’d just started to sweat in the sun when I read the poem’s first lines:

I move my body meat smell next to yours,

Your spice of Zanzibar. Mine rains, yours pours—

Sex tropics as a way to not be dead.

I don’t know who we are except in bed.

This was before I’d read much of Seidel’s work, and these lines felt outrageous to me, especially that long row of monosyllables, “as a way to not be dead.” It was the perfect poem to read on a summer vacation—as long as it went on, I was living in a kind of lewd Zanzibar of the the mind.

With its ostentatious rhymes (Labia with Arabia), its nods and winks to the politics of the day (The president of the United States / Is caught between those two tectonic plates, / Republicans and Democrats) and its flagrantly oversexed images (a cowboy sipping honey from a pair of sweet lips), “Arabia” now reads to me like vintage Seidel—the way it forces the visceral and the bodily to coexist with the elegant, the faint taunt that comes in a line like “I’m happy staring at what makes me stare.” It also contains what you might read as an incidental summary of Seidel’s poetics: “It’s politics, it’s tropics, and it’s warm.” (And it is, like sex tropics, a great way not to be dead.) After that first stanza, it continues:

I’ll tell you someone I’m not happy with—

But no I won’t. I won’t destroy the myth.

The president of the United States

Is caught between those two tectonic plates,

Republicans and Democrats, the nude

Alternatives to naked solitude.

It’s politics, it’s tropics, and it’s warm

Enough to arm the sunrise with a car alarm

That’s going off and starts the earthquake shake

And shiver, shiver, of the sobbing steak.

O sweet tectonic fault line and sweet lips

Exuding honey that the cowboy sips.

Read the whole poem here.

On Being a Regular, or Strange Chefs, Part 2

A counterpart to yesterday’s piece.

Regulars in the village pub in Tomintoul, Banfshire, 1943. Photo: British Ministry of Information

Speaking of characters. There was a time when, for a small adventure, one had only to go to a particular bakery in the West Village. You know the one I mean. The owner was unfailingly unpleasant, the coffee unfailingly terrible, the place lacking air-conditioning and, in summer, unbearably stuffy. But the croissants were good in their heavy way, and it was always entertaining to see people attempt to ingratiate themselves with the management.

When said owner retired, he sold his business to a hard-working and kindly employee and today things go on much as before, save that now the customer service is more or less normal. It’s not the adventure it used to be. I happened to stop in for a pain aux raisins and one of those awful coffees the first day they reopened, just by chance. One fellow bellied up to the counter and said in a confidential fashion, “Man, am I glad to see you. Jean was a piece of work. Came here every day for ten years and couldn’t get a friendly word out of him.”

He was clearly looking for commiseration, but got only a noncommittal smile from the new owner, and went away with his desired status as “beloved regular” still very much in question. No sooner had he left than another man, who’d overheard, approached the counter with an equally confidential air.

“I heard what that guy said,” he said, “and frankly, I never understood people like that. Jean liked anyone reasonable. You just had to act like a human being. I mean, he and I got along great.”

He also was rewarded only with a vague smile. Clearly, despite the change in demeanor, the no-favorites policy was in no danger. These things exist for a reason, it seems to me. I like anonymity. If you live in New York by choice, you probably do, too. In my case, this love of privacy comes with a hatred of being scrutinized and a tendency to paranoia, which is not always ill founded.

There was, for instance, a certain gourmet takeout shop near my place of employment where I used to stop for a jelly donut maybe once a week. The same young guy waited on me each time and one day said, all jocular: “If this keeps up, we’re going to have to roll you out of here one of these days!”

Had a covenant been broken? I think it had. I should have had a croissant.

On Being a Regular, or, Strange Chefs, Part II

A counterpart to yesterday’s piece.

Regulars in the village pub in Tomintoul, Banfshire, 1943. Photo: British Ministry of Information

Speaking of characters. There was a time when, for a small adventure, one had only to go to a particular bakery in the West Village. You know the one I mean. The owner was unfailingly unpleasant, the coffee unfailingly terrible, the place lacking air-conditioning and, in summer, unbearably stuffy. But the croissants were good in their heavy way, and it was always entertaining to see people attempt to ingratiate themselves with the management.

When said owner retired, he sold his business to a hard-working and kindly employee and today things go on much as before, save that now the customer service is more or less normal. It’s not the adventure it used to be. I happened to stop in for a pain aux raisins and one of those awful coffees the first day they reopened, just by chance. One fellow bellied up to the counter and said in a confidential fashion, “Man, am I glad to see you. Jean was a piece of work. Came here every day for ten years and couldn’t get a friendly word out of him.”

He was clearly looking for commiseration, but got only a noncommittal smile from the new owner, and went away with his desired status as “beloved regular” still very much in question. No sooner had he left than another man, who’d overheard, approached the counter with an equally confidential air.

“I heard what that guy said,” he said, “and frankly, I never understood people like that. Jean liked anyone reasonable. You just had to act like a human being. I mean, he and I got along great.”

He also was rewarded only with a vague smile. Clearly, despite the change in demeanor, the no-favorites policy was in no danger. These things exist for a reason, it seems to me. I like anonymity. If you live in New York by choice, you probably do, too. In my case, this love of privacy comes with a hatred of being scrutinized and a tendency to paranoia, which is not always ill-founded.

There was, for instance, a certain gourmet takeout shop near my place of employment where I used to stop for a jelly donut maybe once a week. The same young guy waited on me each time and one day said, all jocular: “If this keeps up, we’re going to have to roll you out of here one of these days!”

Had a covenant been broken? I think it had. I should have had a croissant.

A World Beyond the Glass: An Interview with Mary Szybist

Photo: Meilani Kirkwood, courtesy of Graywolf Press

Mary Szybist may not have been the best-known writer on the poetry shortlist for the 2013 National Book Award, but her book Incarnadine was ambitious and thoughtful enough to overcome this. Her second collection, after Granted (2003), Incarnadine comprises poems focused on the Annunciation. Szybist, who was raised Catholic, uses this intimate moment as an opportunity to explore the relationships between poetry and prayer and to explicate an encounter between the human and “the other”—something outside of human experience, be it nature or, in this case, God.

The National Book Award judges called Incarnadine “a religious book for nonbelievers.” It opens with an epigraph from Simone Weil’s Gravity and Grace, which sums up Szybist’s approach to the project: “The mysteries of faith are degraded if they are made into an object of affirmation and negation, when in reality they should be an object of contemplation.” Receiving the award, she said, “There’s plenty that poetry cannot do, but the miracle, of course, is how much it can do, how much it does do.” I spoke with Szybist recently about religion, poetry, prayer, and the meaning of her name.

Incarnadine deals with the Annunciation—the visitation of Mary by the angel Gabriel, who tells her that she will have God’s son—and the implications and meaning of such an event. It’s an encounter between the human and something beyond human understanding. Your book is an attempt to describe the indescribable through poetry—which is something that prayer can do, also.

Prayer is one way to do this—and yes, I have thought about the connections between poetry and prayer for a long time, and sometimes I am even tempted to believe that they are similar engagements. When I was young, I reached a point where I found myself unable to pray. I was devastated by it. I missed being able to say words in my head that I believed could be heard by a being, a consciousness outside me. That is when I turned to poetry.

I have always been attracted to apostrophe, perhaps because of its resemblance to prayer. A voice reaches out to something beyond itself that cannot answer it. I find that moving in part because it enacts what is true of all address and communication on some level—it cannot fully be heard, understood, or answered. Still, some kinds of articulations can get us closer to such connections—connections between very different consciousnesses—and I think the linguistic ranges in poetry can enable that.

Reading your poems about Mary and what her experience might have meant, I was reminded of Blake’s line “I must create a system or be enslaved by another man’s.” Was that in your mind as you were writing? Or is this book the distillation of a lifetime of thinking about religion and faith?

I turn to poems to find spaces that might enlarge, rather than distill, experience. I thought a lot about that idea from Blake when I was working on this collection. Returning to Christian iconography felt, at times, like going backward. Nevertheless, I came to think that I couldn’t lessen the power the icons had for me simply by trying to ignore them. They had taken hold of my imagination a long time ago, and I was still in their imaginative thrall, even if intellectually I rejected much of what they stood for.

So it was Blake, in a way, who inspired me to remake them. I was never compelled, however, by the idea that the only way to lessen the power of one system is to replace it with another. I don’t find Blake’s new cosmology the most interesting part of his work. I return to Songs of Innocence and of Experience often, not because they present a solution or a new and better system, but because they brilliantly hold up the limitations of two modes of experience and prompt me to try to imagine a way of being that might not suffer from the restrictions and dangerous naïveté of either mode. I love that Blake sympathetically acknowledges the temptations of both modes and the difficulties of going beyond them. In the spirit of Blake’s Songs, I wanted to create multiple versions in this collection in an attempt to provoke my imagination beyond them. I want to take the iconography of the Annunciation out of the realm of symbol, where its meaning is predetermined, and into the realm of contemplation—a realm with room for doubt, investigation, imagination, play.

You’ve spoken about how you were inspired by seeing the vast number of paintings made in the Middle Ages about just a handful of religious scenes—among them the Annunciation—and all the variations that different artists brought to the same tableaux. Did this tradition influence you in approaching the poems for Incarnadine?

The first time I visited Italy, I was overwhelmed by how many paintings depicted the same scenes, particularly religious scenes—the Nativity, the Madonna, the Crucifixion, the Assumption, and so on. At first there seemed something excruciatingly limited about it, and I felt relieved to live at a time when our choices as writers and artists are, at least relatively, so expansive. I remember one afternoon in a museum thinking to myself, I can’t look at one more painting of a dead or dying Christ. I actually felt physically ill at the thought of it. Then I turned the corner into the next room and was grateful to be in the presence of Andrea Mantegna’s harrowing, beautiful Cristo morto.

Only then did it occur to me that many of the paintings I love most—Annunciation scenes by Fra Angelico, Simone Martini, Leonardo da Vinci, Sandro Botticelli—were made within these subject limitations, and I started to wonder if the limitations themselves had played a role in engendering the art. I began to imagine imposing this subject limitation on a series of poems. I was drawn to the challenge of having to work that particular limitation, and I was drawn to the Annunciation scene for all kinds of reasons, including the ones you articulated at the start of this interview. Paintings of the Annunciation tend to reinforce a vision that a transformative encounter between two radically different kinds of being is possible, and yet they also emphasize a real and unmistakable distance between those beings that never closes. That acknowledgement, for me, is part of why the vision feels viable. I wanted to include and enter that space in the poems.

You quoted Wallace Stevens in your acceptance speech. Is there a poem that stands out in your mind as being able to connect us with “the other”?

I think that a good deal of poetry and art gives us some sense of access to another’s voice, perception, texture of thought, imagination. Sometimes it gives us better access to the strangeness in ourselves.

Wallace Stevens is a virtuoso of this. I am particularly moved by the vision of “The Idea of Order at Key West.” In that poem, the song of the woman on the shoreline is a kind of otherness, and the speaker’s connection with it moves him toward deeper engagement with the larger world.

Your mother died this year, and while listening to your acceptance speech, I couldn’t help but think of that, and the idea that today art and poetry offer people many of the same things that religion once did.

I am both attracted to and resistant to the idea that poetry and art can be replacements for religion. Art is not religion, and neither can bring back the dead—at least not in the way that I want them back. One of the things I liked about practicing a religion is the sense of being part of something larger than myself, larger even than my own imagination. It provided relief from myself. I gave myself over to a set of rituals, I could enter into prayers the way I could enter into a church. The opportunity of making a poem offers something different. As Charles Wright once said, “New structures, new dependencies.”

Since you finished Incarnadine, have you been exploring a new approach or way of thinking?

Someone once advised me to write the kind of poems that I wanted to read, and I have been thinking about that a lot. Lately I want to read poems that somehow provide company, if not guidance, in living through grief and sadness. I used to think often of this sentence from Iris Murdoch—“Only the very greatest art invigorates without consoling, and defeats all our attempts to use it as magic.” Occasionally, however, it is possible for a great poem to invigorate and console. I think of George Herbert and William Carlos Williams. I have been thinking about what kind of consolations poems might still authentically offer.

I would imagine that one positive thing about winning the National Book Award is that people know how to pronounce your last name.

I suspect that there is little danger that many people will know how to pronounce my last name! I can’t say that it has ever bothered me when people mispronounce my name. There are conflicting authorities when it comes to how to pronounce it. My parents and grandparents pronounced it SHE-bist, so that is how I pronounce it. It is a way of belonging to them. On the other hand, my great-grandparents most likely invented—or deferred to?—this Americanized pronunciation. My understanding is that the Polish pronunciation is closer to sha-BIST.

Perhaps there is a way in which I wanted Incarnadine to give my first name as much possibility as my last name. “Mary” always seemed so common and overworn, so weighed down by the “known”—and by what I came to think of as a Platonic ideal of the Virgin Mary. One of the unexpected treats of visiting Laos a couple of years ago was learning how funny the name “Mary” seemed to Laotians. The young boys I tutored in English knew the verb to marry, but the idea of using it as a name struck them as strange and comical. “Mary,” the boys asked, “are you married?” Hilarious laughter ensued.

A Polish woman once told me that “Szybist” means glassmaker or window maker. I have no idea if this is true, and I haven’t pursued the truth yet because I am fond of the idea that my name might carry such meaning. I remain intrigued by the old trope of stained glass as a metaphor for poetry and even for language. I spent many hours looking up at the Annunciation scene in a stained glass window in my childhood church, watching the way the light changed the scene, lighting it up, letting it go. The faces of the figures are somehow always the first parts to be extinguished in the evening. The colored glass was so thick that I couldn’t see much through it, even in the most optimal moments. Still, I could see shadows, light—hints of a world beyond the glass.

The Disappearing Face of New York

What was once Optimo Cigars is now a boutique cupcake shoppe. Photo: James and Karla Murray, via Facebook

Smithsonian Magazine, Beautiful Decay, and others have recently featured photographs from Store Front: The Disappearing Face of New York, published in 2008 by James and Karla Murray. In 2004, the couple “began a project to capture New York City’s iconic storefronts—the city’s unique, mom-and-pop restaurants, shops, and bars—before they disappeared.” Now, ten years later, they’ve revisited the storefronts to find that most of shops have, in fact, disappeared:

Many traditional “mom and pop” neighborhood storefronts that had prevailed in some cases for over a century were disappearing in the face of modernization and conformity, and the once unique appearance and character of New York's colorful streets were suffering in the process … We noticed very early on while photographing the original stores that if the owner did not own the entire building, their business was already in jeopardy of closing. The owners themselves frequently acknowledged that they were at the mercy of their landlords and the ever-increasing rents they charged … When the original 2nd Avenue Deli location in the East Village closed in 2006 after the rent was increased from $24,000 a month to $33,000 a month, and a Chase Bank took over the space, we knew the contrast of before and after was severe.

More of the photos can be seen on James and Karla’s Facebook page. They’re especially sobering given the sad fate of Rizzoli Bookstore, which will shutter its beautiful, historic 57th St. location on April 11.

Raskolnikov Meets the Caped Crusader, and Other News

Image via Open Culture

If you’re having trouble getting serious reading done, you can go ahead and blame the Internet, which fosters deleterious skimming habits. “It was torture getting through the first page. I couldn’t force myself to slow down so that I wasn’t skimming, picking out key words, organizing my eye movements to generate the most information at the highest speed. I was so disgusted with myself.”

Yesterday was Don B.’s birthday, making today the perfect occasion to reread his 1987 essay, “Not-Knowing.” “Let us discuss the condition of my desk. It is messy, mildly messy. The messiness is both physical (coffee cups, cigarette ash) and spiritual (unpaid bills, unwritten novels). The emotional life of the man who sits at the desk is also messy—I am in love with a set of twins, Hilda and Heidi, and in a fit of enthusiasm I have joined the Bolivian army.”

“Every April, ‘O, Miami’ attempts to deliver a poem to every single person in Miami-Dade County.” (There are at least 2.591 million of them—I just checked.)

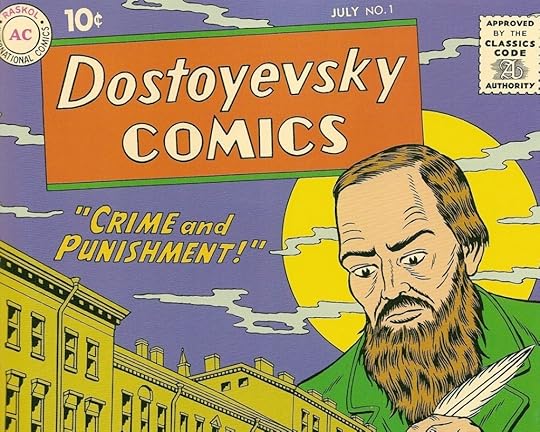

Crime and Punishment and Batman: all in one scintillating, thrill-packed issue of Dostoyevsky Comics. One wonders which superhero moonlighted in the Brothers Karamazov issue.

From the annals of game-show history comes Bumper Stumpers , a late-eighties Canadian television curio in which contestants parsed the wordplay in vanity license plates. (E.g. “VTHKOLM,” which means fifth column, obviously.)

Meet Todd Manly-Krauss, the “writer” with the world’s most irritating Facebook presence.

April 7, 2014

Realism for Everyone

Donald Barthelme would’ve been, and should be, eighty-three today. It would be an exaggeration to say that I feel the absence of someone whom I never met—someone who died when I was three—but I do wonder, with something more than mere curiosity, what Barthelme would have made of the past twenty-odd years. These are decades I feel we’ve processed less acutely because he wasn’t there to fictionalize them: their surreal political flareups, their new technologies, their various zeitgeists and intellectual fads and dumb advertisements. Part of what I love about Barthelme’s stories is the way they traffic in cultural commentary without losing their intimacy, their humanity. They feel something like channel-surfing with your favorite uncle; he’s running his mouth the whole time, but he’s running it brilliantly, he’s interlarding his commentary with sad, sharp stories from his own life, and you’re learning, you’re laughing, you’re feeling, because he’s putting the show on for you, lovingly, his dear nephew.

But I’m losing the thread. My point is not to reveal a secret wish that Barthelme was my uncle.

I wanted to say something about lists. Barthelme was a master of many things, but one of them was, of course, the list—the man could make a prodigious inventory. I don’t mean to be glib when I say that. List-making is often dismissed as sloppy writing, but in Barthelme’s hands, a list never functions as an elision or a cheap workaround; he makes marvelous profusions of nouns, testaments to the power of juxtaposition. His lists feel noetic—they capture the motion of a mind delighting in how many things there are, and how rampantly they’re proliferating, and how strangely they collide in life, when they do. Here, for instance, is a list of breakfasts from “The Zombies,” which I once heard Emily Barton read aloud at a panel on Barthelme:

A zombie advances toward a group of thin blooming daughters and describes, with many motions of his hands and arms, the breakfasts they may expect in a zombie home.

“Monday!” he says. “Sliced oranges boiled grits fried croakers potato croquettes radishes watercress broiled spring chicken batter cakes butter syrup and café au lait! Tuesday! Grapes hominy broiled tenderloin of tout steak French-fried potatoes celery fresh rolls butter and café au lait! Wednesday! Iced figs Wheatena porgies with sauce tartare potato chips broiled ham scrambled eggs French toast and café au lait! Thursday! Bananas with cream oatmeal broiled patassas fried liver with bacon poached eggs on toast waffles with syrup and café au lait! Friday! Strawberries with cream broiled oysters on toast celery fried perch lyonnaise potatoes cornbread with syrup and café au lait! Saturday! Musk-melon on ice grits stewed tripe herb omelette olives snipe on toast flannel cakes with syrup and café au lait!” The zombie draws a long breath. “Sunday!” he says. “Peaches and cream cracked wheat with milk broiled Spanish mackerel with sauce maitre d’hotel creamed chicken beaten biscuits broiled woodcock on English muffin rice cakes potatoes a la duchesse eggs Benedict oysters on the half shell broiled lamb chops pound cake with syrup and café au lait! And imported champagne!” The zombies look anxiously at the women to see if this prospect is pleasing.

The list is the ideal vehicle here. It’s an efficient mechanism for comedy, yes, but it also pulls back the curtain a bit, letting the reader share in the wry wonder that I imagine Barthelme might’ve felt as he composed it: How did it come to pass that we, in our kitchens and our restaurants and our fluorescent supermarkets, developed such a sophisticated vocabulary for food, for breakfast? How is it that we eat so many things, that the human experience has come to encompass rice cakes and fried liver, to say nothing of courtship rituals centered on ingestion? I would guess that Barthelme was not so wide-eyed about these things as I am—but what his lists offer, in effect, is the working of a mind, an invitation to join him in doing the math, connecting the dots, asking the questions, and so on. To those who would dismiss it as merely goofy, I offer this bit from his Art of Fiction interview:

INTERVIEWER

Wordsworth spoke of growing up “Fostered alike by beauty and by fear,” and he put fearful experiences first; but he also said that his primary subject was “the mind of Man.” Don’t you write more about the mind than about the external world?

BARTHELME

In a commonsense way, you write about the impingement of one upon the other—my subjectivity bumping into other subjectivities, or into the Prime Rate. You exist for me in my perception of you (and in some rough, Raggedy Andy way, for yourself, of course). That’s what’s curious when people say, of writers, This one’s a realist, this one’s a surrealist, this one’s a super-realist, and so forth. In fact, everybody’s a realist offering true accounts of the activity of mind. There are only realists.

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers