The Paris Review's Blog, page 721

April 1, 2014

A Vintage Plimpton Prank

Today’s been so chock full of hoaxes, shenanigans, pranks, put-ons, spoofs, tomfoolery, and good-natured hooliganism that we’ve almost forgotten to remind you of the hoaxes, shenanigans, pranks, put-ons, spoofs, tomfoolery, and good-natured hooliganism of yesteryear. One case in particular merits revisiting: we speak, of course, of a 1985 hoax executed in grand fashion by our late founder, George Plimpton. PBS’s American Masters tells the story with help from Jonathan Dee:

For the April 1, 1985, issue of Sports Illustrated, George Plimpton wrote “The Curious Case of Sidd Finch,” a profile on an incredible rookie baseball pitcher for the New York Mets. Sports fans took his April Fools’ Day joke seriously. Even other journalists were willing to believe a novice could throw a 168-mph fast ball, thanks to his Buddhist training (Sidd was short for Siddhartha, the title character of Herman Hesse’s novel). To keep the hoax going, a nervous George Plimpton relied on a young Jonathan Dee, now a famous fiction writer but then an associate editor and Plimpton’s personal assistant at The Paris Review. Dee describes Plimpton’s tense days surrounding the hoax in this film outtake.

American Masters’ Plimpton! Starring George Plimpton as Himself premieres nationally Friday, May 16, on PBS.

Here’s Pie in Your Eye

Pieing for fun and profit.

“I used to throw pies for a living.”

The story usually elicits a good chuckle or two. It’s the perfect gambit when dinner-party conversation lags—a legendary prank executed long ago in my rascal past, a kind of April Fools’ joke.

But what my audience never knows is this: they’re talking to a guy who once commanded a hit squad of domestic terrorists that carried out a slew of public attacks in broad daylight and got away with it.

Well, mostly. An enraged crowd of Trekkies nearly stomped me to death after I’d boldly gone and pied William Shatner, their beloved Captain Kirk, at a Star Trek convention. But I’m getting ahead of myself.

While I abhor pointless violence, I have long believed there are some people in this world who deserve to be smacked in the face with a pie. Vladimir Putin, for example, or my girlfriend’s ex-husband—anyone for whom a well-aimed pie could serve as a rebuke and a corrective measure. The legal code may define it as a violent act—when comedian Jonnie Marbles pied Rupert Murdoch, he earned jail time for assault—but to my mind, what motivates the striking thrust is not violence but idealism. Che Guevara once said, “The true revolutionary is guided by great feelings of love.” I say the tart’s trajectory is often guided by faith in humanity—or at least a sense of humor.

Popular belief has it that the pie-in-the-face gag (a word derived from the Norse gagg, meaning “yelp”) originated in the silent-movie era. Performed by the slapstick director Mack Sennett’s Keystone Kops, Fatty Arbuckle, Laurel and Hardy, the Three Stooges, and various imitators then and since, the stunt seems uniquely American. What better enforcer of the democratic dogma than a tossed pie? A gooey face is an instant social equalizer.

Of course, the self-important have always been targets for a takedown; even if pieing is a predominantly American phenomenon, the puncturing of pomposity is universal. I’m reminded of certain graffiti left behind in Egyptian tombs by workers who remarked on the pharaoh’s resemblance to the buttocks of an ox.

The French have a word for it, of course: lèse-majesté, “injured sovereignty,” an ancient crime from the Roman era, still on the books in such countries as Turkey and Thailand. Even in the Netherlands, a man was jailed in 2012 for calling Queen Beatrix a “con woman” and a “sinner,” and demanding abolishment of the monarchy. Royalty has always deserved, short of the guillotine, the pie.

The first incidence of political pie-throwing occurred in 1970, when politics overshadowed everything. Nixon ruled, the Vietnam War dragged on, and the previous decade’s legacy of political assassinations carried over into a new decade of surliness and pugnacity. In the early days of May, antiwar protesters filed the streets and the National Guard shot four students dead on the Kent State University campus.

Capitol Hill on May 13, 1970, was not in a joking mood. Thomas King Forcade, head of the Underground Press Syndicate, was testifying before a meeting of the President’s Commission on Obscenity and Pornography, originally convened by Lyndon B. Johnson. Forcade cited forty-five publications around the country shut down or persecuted by authorities on charges of obscenity. He concluded his testimony with the cry, “The only obscenity is censorship!” Then he drew a cream pie he’d somehow smuggled in his briefcase and launched it accurately into the face of commission chairman Otto N. Larsen, the head of the University of Washington’s sociology department. Wire services carried the photo worldwide.

Forcade’s epic pie-toss was the first known instance of pastry as a political weapon. Nothing less than domestic terrorism à la mode, it was a kind of violence that inflicted smiles: Abbie Hoffman and the Yippies scattering money on the floor of the Stock Exchange; an armed, uniformed squad of Vietnam Veterans Against the War roughing up tourists in the U.S. Capitol and threatening to add to their “body count.” Guerilla Theater, we used to call this tomfoolery, and as the original Boston Tea Party did, it helped fire up a revolution.

Forcade was a buddy of mine. We conspired on a wide range of joint ventures, so to speak, involving pot, publishing, politics, and mayhem, including the creation of High Times magazine. An unusual intellect as well as a pioneer of Colombian imports, Forcade was an avid fan of the sci-fi genre. One of his favorite novels was Agents of Chaos.

Written by Norman Spinrad, Agents of Chaos posits a naive revolutionary group sometime in the distant future; they fight the Hegemony to bring democracy to the solar system. But the rebels and rulers contend with a third force, the unpredictable Brotherhood of Assassins—aka the Agents of Chaos. Fearless, cultish followers of the philosopher Gregor Markowitz, the Agents are guided by his Theory of Social Entropy. “Every Social Conflict,” according to Markowitz, “is the arena for three mutually antagonistic forces”: the Establishment, the anti-Establishment, and Chaos—the pervasive tendency for everything to screw up.

Forcade was on the side of the screw-ups. He saw Democrats and Republicans, liberals and conservatives, left and right, as part and parcel of the same Establishment; he wanted to be the Third Force, subverting the whole shebang. In Agents of Chaos he found his guiding principle, and, aided by illicit pharmacopeia and a manic-depressive condition, he acted it out. As a result, he was shunned by the left, hounded by the FBI, and frequently irritating to his closest friends.

Goaded by the political zeitgeist, I was determined to create my own Agents of Chaos, a cadre of trusted comrades who could be called upon to rise up and act decisively, who would know how to infiltrate difficult locations, carry out a plan of action, and escape into the night. Partisans to fight off Nixon’s gestapo after Tricky Dick’s inevitable coup d’etat! But clandestine groups required too much secretive energy. Instead, I decided, we would train openly, using pies as a front.

Taking a businesslike approach, we created a brochure offering a menu of attacks: Squirt Gun Ambush, Seltzer Bottle Blitz, and the classic Pie-in-the-Face, with a choice of flavors (chocolate cream, lemon meringue, etc.). Fees began at a basic $150, with upward adjustments depending upon the difficulty involved. Their anonymity guaranteed, customers signed a contract authorizing the hit. Payment was 50 percent up front, with the remainder, plus expenses, due on the successful conclusion of the mission. For an extra fee we provided photographic evidence. A small advertisement in the Village Voice got us started; a bit of PR pulled a mention from Voice columnist Howard Smith. Agents of Pie-Kill took off.

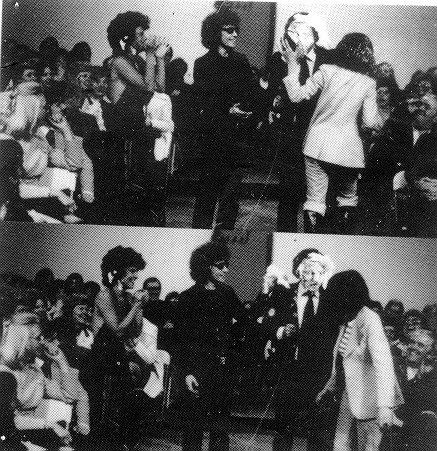

David Frost getting pied on live TV. That’s me with the big fro. The woman next to me is the actress Adrienne Barbeau. I pied her.

At first, our ranks counted two: me and my then-girlfriend. Call her Agile Accomplice. She’s the one in thigh-high leather boots who jumped out of a taxicab in front of the Buffalo Roadhouse patio, just off Sheridan Square, waving a couple of water-filled pistols, dousing a client’s cheating boyfriend. (He was dining al fresco with his new sweetie.) It was she who shoved a cream pie in David Frost’s face on live network television, a hit contracted by the show’s producer. She possessed a certain pie panache.

When business demanded more agents, our first recruit was a sturdy young man named Aaron Kay. He was a Brooklyn-born disciple of A. J. Weberman, the so-called Garbologist, infamous for digging through Bob Dylan’s trash. Kay used to act as a sort of bodyguard for Weberman—his awesome girth and bulk were perfect for fending off Weberman’s critics, mainly fanatical Dylan fans. I taught our willing cadet the proper procedures: reconnoitering the location, surveilling the target, rehearsing the moves and plotting alternate escape routes. Within days of joining Pie-Kill, he was in the field, armed and dangerous—as long as he didn’t eat the pies.

At its peak, Agents of Pie-Kill’s roster numbered half a dozen agents. We pulled in a fair amount of cash revenue and inspired imitators worldwide. Time called us “the biggest fad since streaking.” Every day the news would report someone somewhere getting a pie in the face. Our own Agent Kay scored headline-making hits against the conservative pundit William F. Buckley and antifeminist Phyllis Schlafly.

Things got out of hand when Pat Halley, a Detroit affiliate acting pro bono, smacked a pie into the kisser of the fifteen-year-old self-proclaimed Perfect Master Guru Maharaj Ji. As reported by Walter Cronkite on national news and around the world, God had been hit in the face with a shaving-cream pie! The Guru’s acolytes retaliated, putting Halley in the hospital with fifty-five stitches and a permanent plastic plate in his skull.

It wasn’t long before we noticed Agent Kay had switched to autopilot. He couldn’t stop throwing pies at people: Watergate operative Gordon Liddy, New York City mayor Abe Beame, Senator Daniel Moynihan, and even rock poet Patti Smith. The list goes on. Agents of Pie-Kill had created a monster. And suddenly, the times were a-changin’ once again: Nixon was gone, the war was over, and a peanut farmer was president. Time to close the patisserie.

The subversion of our radical agenda—to what was, at best, a lighter moment on the evening news, and, at worst, a business model for the service industry—was politically pathetic, it’s true. But “there’s no success like failure,” as Dylan says, capturing the ambivalence of the postsixties era, “and failure’s no success at all.” So it goes on. In the wilds of Canada, Les Entartistes, a Canadian bunch specializing in politicians and financiers, was still tossing tarts into the late 1990s. More recently, Confeiteiros sem Fronteiras has been active in Brazil, lobbing pies at rich rainforest despoilers. The pitcher A. J. Burnett, during the Yankees 2009 season, deflated scoring teammates with pies in the face as they touched home plate. Lucy Liu and Jimmy Fallon mutually pied each other last year on late-night TV.

My own exploits would fill volumes. The full story awaits scholarly research in the Pie-Kill Archives, recently acquired by Yale’s Beinecke Library. I will probably never launch a pie again. Nor will my former associates: Agile Accomplice has gone off to pursue targets with a sharpened pen. My cadre has withered away—except for Aaron Kay, who, at sixty-three, weighs a reported 366 pounds. He is too well recognized to wield a pie effectively, and is under doctor’s orders not to consume any more of them.

The terrible truth is that far more serious agents of chaos have run the surprise-attack business into the ground. Things are so tight now you couldn’t fling a cupcake without running afoul of Homeland Security or Moms Against Bullying. On some level, the prankster has been pranked—the joke’s on us. As a veteran mischief-maker, I would say that April Fools’ Day in America is over.

But then again, you never know.

Based in LA, Rex Weiner is a cofounder of the Todos Santos Writers Workshop and the Hollywood correspondent for Rolling Stone Italia .

Give a Warm Welcome to Our Newest Issue

At last! Spring is here, Easter is coming, and, as you can see, the latest issue of The Paris Review has already taken its pastels out of the closet—it’s ready to sally forth into the cherry blossoms. And at its heart are two of our most anticipated interviews.

At last! Spring is here, Easter is coming, and, as you can see, the latest issue of The Paris Review has already taken its pastels out of the closet—it’s ready to sally forth into the cherry blossoms. And at its heart are two of our most anticipated interviews.

First, there’s Cormac McCarthy on the Art of Fiction:

I rise at six and work through the morning, every morning, seven days a week. I find the sun has a forlorn truth before noon.

And there’s Thomas Pynchon on his process, his elaborate research for Bleeding Edge, and his depiction in the media:

Being called paranoid seems preferable to any number of things. Especially now, with the degrees of access, the ubiquity of cameras—it’s a position that seems increasingly less, well, paranoid. The word that does bother me is recluse. I don’t consider myself reclusive.

Plus, an excerpt from a newly unearthed novel by Roberto Bolaño; fiction by Lydia Davis and Ottessa Moshfegh; poems by Frederick Seidel, Anne Carson, and Dorothea Lasky; an essay by Christian Lorentzen; and a portfolio by Salman Rushdie.

We humbly assert that it’s one of our strongest issues ever. See for yourself.

The Circus Is Brighter in Poland, and Other News

“Cyrk” poster, designed by Lech Majewski, Poland, 1973.

D. H. Lawrence’s hometown has opened a new pub called the Lady Chatterley.

An enterprising fourteen-year-old has an urgent message for the government: change your official typeface to Garamond and you’ll save millions.

Shakespeare plays illustrated in three easy panels. (“Three witches tell Macbeth he will be king. Macbeth kills lots of people in order to be king. Macbeth is killed.”)

Taking stock of Monocle, which is now seven years old: “a magazine that is in general focused on a particular brand of well-heeled global urbanism … Monocle doesn’t have bureaus, it has bureaux … what Monocle and its advertisers clearly understand, even if the point is seldom made explicit, is that living in a first-tier city is a luxury good, like a Prada bag or a pair of Hermès boots.”

Don’t merely go to the circus. Go to the circus in Communist-era Poland. “The visual style of the Polish School of Posters, funded and sponsored by state commissions, was characterized by vibrant colors, playful humor, hand-lettering, and a bold surrealism that rivaled anything similar artists in the West were doing at the time.”

March 31, 2014

Opening Day

George W. Bush throws the first pitch at a Washington Nationals game on March 30, 2008. Photo: Kate Wellington, via Flickr

If there is a baseball team in your area, you may one day be asked to throw out the first pitch. Throwing out the first pitch is a way to recognize someone who is famous or is being honored before the start of a baseball game. —eHow, How to Throw Out the First Pitch

A little after one this afternoon, New York City mayor Bill de Blasio, a Red Sox fan, threw the ceremonial first pitch at Citi Field, where the Mets were facing the Washington Nationals. He was surrounded by seven children affected by the recent East Harlem gas explosion. According to the New York Observer, “Mr. de Blasio, wearing a personalized Mets jersey bearing his last name and the number six, stood a few feet in front of the pitcher’s rubber and tossed a strike to a Mets catcher. Still, fans aggressively booed the mayor when his name was announced, not long before he threw the ceremonial pitch.”

Although his poll numbers are bad right now, de Blasio ought not to take this personally. As the New York Times’s Sam Roberts points out, “Mayors are traditionally booed … I can’t remember one who actually was cheered.”

Confirm the time and date you are to throw out the first pitch of a baseball game. You should be given at least a couple weeks to prepare.

It is hard to imagine anything more terrifying for a non-athlete than the pressure of having to get a ball across the plate, even when one is allowed the dubious privilege of moving in closer than the regulation sixty-plus feet. Judging by the images the Times provides—of mayors Mitchel, Bloomberg, and Koch, respectively—most of them have been awful. (By far the best mayoral first pitch on record is that of Fiorello H. La Guardia; in this film of the 1936 Giants–Dodgers opener, the Little Flower demonstrates both zest and good form.)

Set aside a couple days to practice. Get a baseball, a glove and go to a field with a friend. Start off throwing to each other from about seven feet away to loosen up your arm. As you get comfortable, get further and further apart. Limit your first session to about fifty tosses, and don't throw harder than what feels natural. If you go out to practice again, you can increase the number of throws you do the second time.

It has always seemed strange that baseball should be not just the national pastime—as a baseball fan, I get that—but an expected part of our lives. More than most sports, it requires a lot of practice to master even its most basic elements: hitting, pitching, fielding, and a dense thicket of rules. And yet, our public figures are routinely expected to throw the ball—really far, even with the handicap—into its minuscule strike zone, just as writers, lawyers, and accountants are, every spring, encouraged to take up bats and gloves and man our nation’s softball fields. The result is a kind of ritual embarrassment for the many and a source of glory for the proud few. Like the National Anthem itself, baseball depends on a lifetime of exposure to make any sense whatsoever. When we fail, we fail spectacularly.

And yet, the results can be spectacular, with the kind of spectacularness that can only come of hard work, discipline, and knowledge. The Mets opener was scored by a teenage doo-wop a cappella group from New Jersey called the Whiptones, who appear to be as impressive as they are bizarre. They won the Mets Anthem Search in the off-season. They were not booed.

Remain calm as you walk to the pitching mound to throw out the first pitch. When you are ready to throw the ball, throw it using the same motion that you have practiced. Wave to the crowd as you leave to the mound.

How Much Could Be Left Unsaid: An Interview with Jenny Offill

Issue 208 of The Paris Review included Jenny Offill’s story “Magic and Dread,” an excerpt from her new novel, Dept. of Speculation, published earlier this year. James Wood called it “a novel that’s wonderfully hard to encapsulate, because it faces in many directions at the same time, and glitters with different emotional colors.” Offill is the author of the novel Last Things, and the coeditor, with Elissa Schappell, of two anthologies of essays. She has also written several children’s books, including 17 Things I’m Not Allowed to Do Anymore, 11 Experiments That Failed, and Sparky! She teaches writing at Queens University, Brooklyn College, and Columbia University.

For the narrator of your novel, the wife, there’s a lot of conjecture going on—guessing how to write a book, how to be in a marriage, how to raise a child, how to bear the time of writing a book. Do you consider writing to be a fundamentally speculative act?

One of the odd things about being a writer is that you never reach a point of certainty, a point of mastery where you can say, Right. Now I understand how this is done. That is why so many talented people stop writing. It’s hard to tolerate this not-knowing. It’s hard to tolerate feeling like an idiot or an imposter, and it gets harder as the years tick by.

But I would argue that this feeling of uncertainty is actually the best practice you could have for the other important things you will do in your life. No one ever masters falling in love or being a parent or losing someone close to him. And who would want to master such things, really? Wandering through the woods, looking for a sudden sunlit clearing, that’s the most interesting part of it.

As I read Dept. of Speculation, I kept thinking about the relationship between the blocks of text and the empty space that separates them.

The blank spaces in Dept. of Speculation are meant to provide a place for the reader to enter more fully into the book. The wife is a narrator who hesitates and loops back, then leaps forward again. There is a jittery quality to her thoughts that I was trying to capture. To that end, I thought a lot about how much could be left unsaid in this narrative without sacrificing emotional velocity. If I had wanted to fill in those spaces, I know exactly what I’d put in there.

At one point in Dept. of Speculation, the narrator shares her student evaluations. “She is a good teacher but VERY anecdotal. No one would call her organized … She acts as if writing has no rules.” All these observations could be applied to your work, either as criticism or as praise.

Yes, it was a bit of a joke, of course. I only ever got one of those as an evaluation—the anecdotal one—but after teaching for many years you get a feel for what your students like or don’t about you. I’m very disorganized. I can’t operate a simple stapler successfully and I still xerox things upside down. My students patiently endure all of this.

But the last one—“She acts like writing has no rules”—was a springboard into something bigger, this idea that there are verifiable dos and don’ts in fiction. I don’t believe this at all. If you have enough authority, you can do anything you want.

That said, I did break a secret rule of my own with this book, which is to never ever write about someone who is a writer or a writing teacher. Because who cares? Generally, smart novelists get around this by making their protagonist a painter or a photographer or a documentary filmmaker. That little feint seems to placate the critics.

Your writing is full of allusions to and quotations of other texts. Coleridge, Kafka, Thomas Edison, Carl Sagan. What role does intertextuality play in your writing, and how did you decide to incorporate these particular texts?

Oh, I collect facts and quotes when I can’t write, and I can’t write most of the time. I do a little chance operation sometimes where I flip through outdated reference books to see if anything will strike me as beautiful or momentous. Library roulette, I call it.

I recently read an Enrique Vila-Matas essay on his theory of the novel. He claims that one of the essential features of the twenty-first-century novel will be the triumph of style over plot. When you’re writing, how much are you interested in story, and how much are you interested in form? Does one precede the other?

Fuck the plot, as Edna O’Brien said. What I try to capture as a writer is the feeling of being alive, of being awake. Because of this, I’m more apt to follow the wisp of a thought or a half-glimpsed image than chart a sequential series of events. But I absolutely believe in momentum. Momentum is not plot, but it has that same quality of urgency and forward motion, I think.

Vila-Matas again—“Let’s not kid ourselves; we write in the wake of others.” In whose wake do you write?

I write in the wake of all the writers and thinkers mentioned in the novel. This novel in particular was influenced by the work of Mary Robison and David Markson. But I list more of the jumping-off points on my Web site under the section called Half a Library.

Rilke appears a few times in Speculation, but one quotation especially resonated with me. “Surely all art is the result of one’s having been in danger, of having through an experience all the way to the end, to where no one can go any further.”

Yes, I love that quote. It seems very true to me. Always the danger for me in life and in art is not to be brave. I am not a naturally brave person. I have to will myself not to hole up in my house and read my life away.

Wanted for July: A Writer-in-Residence

Last fall, we partnered with the Standard, East Village to find a Writer-in-Residence—someone with a book under contract who would get a room at the hotel for three weeks’ uninterrupted work. Our winner, Lysley Tenorio, was profiled by the Wall Street Journal; in January, he installed himself in room 1006 and found much to admire from his window. The whole thing proceeded so swimmingly, we thought: Why not do it again?

And so we are. Today through May 1, we’re accepting applications for the next residency at the Standard, East Village, in downtown Manhattan. The residency will last the first three weeks in July; once again, applicants must have a book under contract. Applications will be judged by the editors of The Paris Review and Standard Culture. You can find all the details here. (We’ll answer your most burning question in advance: yes, the room includes unlimited free coffee.)

Recapping Dante: Canto 23, or Hypocrites Get Heavy

John Flaxman, Hypocrites, 1807

We’re recapping the Inferno. Read along! This week: the hypocrites and their leaden robes.

Canto 23 opens like the thematic climax of a slasher flick. Virgil and Dante—picture a cinematic hero and his love interest—have taken the opportunity to escape the methodical watch of the serial killer. Or killers, in this case: our travelers have fled from a pair of the murderous Malebranche, whose naturally violent tempers have been exacerbated by the loss of their human plaything and two of their fellow demons. Dante and Virgil are trying to calculate their next move. Their cell phones don’t work (hell doesn’t get great reception), they cannot fight back, and so Dante, whose scalp is “taut with fear,” asks Virgil to find them an out.

As the demons begin to descend upon our travelers, Virgil grabs hold of Dante as a mother does her infant, and the two slide down a rock to hide. Dante says, “Never did water … rush down … more swiftly than my master down that bank”; and if you suspend disbelief just a bit, you can imagine that it is a coy way of saying, “Virgil acted so quickly, I didn’t even have time to piss myself from fear.”

Though the two are unable to elude detection, they have made it to the next ditch, where the Malebranche’s jurisdiction ends, and where they are therefore safe from the billhooks and the claws. It seems like a bit of a cop-out—after all, if the demons were willing to disobey the divine law that protected Dante and Virgil, why weren’t they weren’t willing to disobey the divine law that determines the territories of hell? But then again, the climax in crime movies always requires a bit of imagination. Are we really supposed to believe that Jimmy Stewart was able to stun his would-be killer in Rear Window using only the flash from his camera?

In this next pocket of hell, Dante and Virgil meet the hypocrites, who are weighed down by long robes of gilded lead. They move with the same sort of sluggish indolence as the people wearing ankle-weights at the gym. Once again, Dante’s accent gives him away, and two sinners stop to speak with him. (They can also tell he’s alive by the way his throat moves.) Dante introduces himself using a construction similar to Francesca’s, from canto 5:

Dante, canto 23: “In the great city, by the fair river Arno, I was born and raised.”

Francesca, canto 5: “On that shore where the river Po with all its tributaries slows to a peaceful flow, there I was born.”

Dante goes on, but before long, he’s distracted by a sight that has even Virgil staring in awe: a sinner nailed to the floor as Christ was to the cross, who feels the weight as each sinner slowly walks over his body. This man is Caiaphas, who, convinced that one man should be martyred for the many, was responsible for Christ’s death. The Hollanders, whose annotations to the Inferno I’ve mentioned before, suggest that Virgil may be totally captivated by this scene because Caiaphas hadn’t yet died and gone to hell when Virgil passed through hell the first time—meaning Virgil has never seen a man crucified to the ground before. This would also explain why Virgil is often able to remain aloof in hell, explaining the torturous scenes to Dante but remaining completely unfazed by the sinners. Here, for once, Virgil is out of his element, and Dante must learn about the hypocrites from one of their own, a sinner.

Hoping to leave the hypocrites, Dante and Virgil ask for directions; they learn that the bridge leading to the next area is no longer standing, and that the demon Malacoda in canto 21 lied to them (“Nearby’s another crag that yields a passage,” Malacoda had said). It’s safe to assume Malacoda didn’t think Dante and Virgil would even survive long enough to find out he was lying.

One of the sinners tells Virgil it probably wasn’t the brightest idea to trust Malacoda—the devil is, after all, the father of all lies. Virgil, irate and probably feeling quite like a moron, struts off in “long strides,” to mock the sinners who are weighed down by their robes. Dante follows in his footsteps.

To catch up on our Dante series, click here.

Alexander Aciman is the author of Twitterature. He has written for the New York Times, Tablet, the Wall Street Journal, and TIME. Follow him on Twitter at @acimania.

Nails by Ray Bradbury, and Other News

Photo via Jezebel/Imgur

Discovered in Harvard’s library: three books bound in human flesh. (“One book deals with medieval law, another Roman poetry and the other French philosophy.”)

One of the perennial dangers of interviewing writers is that they may turn the experience into a short story, with you in it. “Updike had transcribed—verbatim—their exchanges, beginning with the helpful suggestion that the interviewee drive while the interviewer take notes, and extending to trivial back-and-forth unrelated to the matter at hand.”

The estate of Ted Hughes has ceased to cooperate with his latest biographer, barring his access to Hughes’s archives. “The estate was insistent I should write a ‘literary life,’ not a ‘biography.’”

Writing advice from James Merrill: “You hardly ever need to state your feelings. The point is to feel and keep the eyes open. Then what you feel is expressed, is mimed back at you by the scene. A room, a landscape.”

Go on. Give your fingernails that sexy, on-trend Fahrenheit 451 look. You deserve it.

March 28, 2014

Inappropriate

Every funeral is unhappy in its own way. In the case of a second cousin of mine, this way was unexpected. There was grief, yes, and remembering, and laughing, and subterranean tensions, and tearful reunions, and the occasional old score to be settled. None of this is what I mean.

The funeral had proceeded along the normal lines. She had lived a long and full life. Children and old friends had spoken. There had been a brief, ecumenical homily, as suited her unreligious nature. The master of ceremonies, an old friend who happened to be a rabbi, gave instructions as to the next steps in the proceedings—a trip to the cemetery, for those who were going, and later an open house at a son’s apartment. There was the general rustling that accompanies imminent departure.

And then, a woman rushed in from the back of the room. Or maybe she hadn’t been in the back of the room; we were in a large funeral home with a number of chapels on different floors. She could have been lurking anywhere, really; a pew, the hallway, another funeral.

The woman, who was middle-aged and clad in a colorful, flowing skirt, took her place behind the recently vacated lectern. “I want to share something with all of you,” she said, and launched into an a cappella rendition of the Elizabethan ballad “Trees They Do Grow High.”

No one knew quite what to do. I think we all must have assumed that someone else knew who she was. We did not meet one another’s eyes. The singing was very loud, and noticeably off-key. There were endless verses, some maybe invented. She was visibly moved by the act of singing, and several times had to choke back tears.

Then, her song finished, the woman stalked out. Still, I guess, afraid that she was connected to another guest in some way, we all lowered our eyes, and once again gathered our belongings to leave. Afterward, of course, we learned that everyone was equally mystified as to her identity. I think we all felt we had shared something special, and I don’t, in fact, think the feeling was inappropriate.

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers