The Paris Review's Blog, page 698

June 4, 2014

More Drunk Texts from Famous Authors

The long-awaited sequel.

Jessie Gaynor is a consummate professional who sometimes tweets at @jessiegaynor.

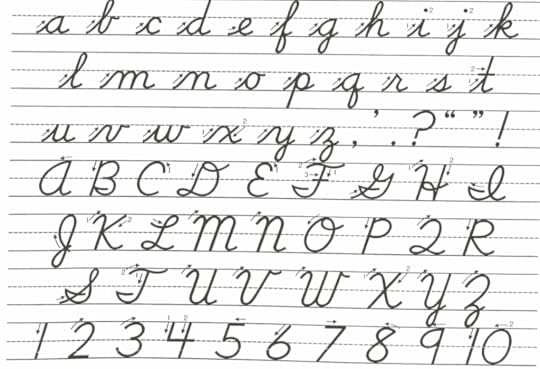

Cursive Matters, and Other News

Image via Wikimedia Commons

A new history argues that Joyce suffered from syphilis.

And a new study suggests unique cognitive benefits to learning to write in cursive: “In alexia, or impaired reading ability, some individuals who are unable to process print can still read cursive, and vice versa—suggesting that the two writing modes activate separate brain networks and engage more cognitive resources … cursive writing may train self-control ability in a way that other modes of writing do not, and some researchers argue that it may even be a path to treating dyslexia.”

In an ancient Chinese tomb, archaeologists have found three-thousand-year-old pants. “These pants, which were recovered from a tomb in China, are about four hundred years older than the previous record holder for ‘oldest pants.’”

At the Tate, “Crowds gather at the heart of Henri Matisse: The Cut-Outs, drawn to an artless home movie showing the master at work. He looks, and was, extremely unwell … Art for him is the moment at which, to quote a remark he made about Snail, one becomes ‘aware of an unfolding’. ‘At this time of year,’ he wrote to a friend, ‘I always see the dried leaves on your table, catching fire as they pass under your fingers from death to life.’”

“Books do indeed furnish a room—but tobacco smoke gives it volume, substance and an aroma.”

In the forties, the U.S. Public Health Service gave this pamphlet to anyone whose home had been sprayed with DDT; it includes a poem of sorts. “Stay indoors at night / That is when malaria skeeters bite / But DDT upon your wall / will kill them if they call.”

June 3, 2014

A Boiling Soup of Opium

Unknown Chinese artist, Commissioner Lin and the Destruction of the Opium in 1839

Happy Opium Suppression Movement Day! This is, according to such reputable resources as Wikipedia and career.osa.ncku.edu.tw, a Taiwanese holiday dedicated to stamping out cigarette smoking—but it all began on June 3, 1839, when more than one thousand tons of illegal opium were systemically destroyed at Humen, in China’s Guangdong province.

By that time, an estimated four to twelve million Chinese citizens were opium addicts; though the opium trade had been banned in China since 1800, smugglers continued to import massive quantities, largely to the gain of the British and the East India Company. The Daoguang Emperor, understandably fed up with these circumstances, adopted a kind of zero-tolerance policy, enforced by a Special Imperial Commissioner named Lin Zexu.

In March of 1839, tensions between the British and the Chinese came to a head, and Commissioner Lin aimed to seize the Brits’ entire supply of opium; when said Brits offered only a small bit of their contraband, Lin threatened to behead one of them. Long story short, his force paid off, and he came into tons and tons of opium. On June 3, he began to destroy it all, a task that absorbed the better part of three weeks. An 1888 account explained his process, which was ingenious, if labor-intensive:

At an elevated spot on the shore a space was barricaded in; here a pit was dug, and filled with opium mixed with brine: into this, again, lime was thrown, forming a scalding furnace, which made a kind of boiling soup of the opium. In the evening the mixture was let out by sluices, and allowed to flow out to sea with the ebb tide.

Elijah Coleman Bridgman, an American missionary, offered a more extended explanation:

In the first place, a trench was filled two feet deep, more or less, with fresh water, from the brow of the hill. The first trench was in this state, having just been filled with fresh water. Over the second, in which the people were at work, forms, with planks on them, were arranged a few feet apart. The opium in baskets was delivered into the hands of coolies, who going on the planks carried it every part of the trench. The balls were then taken out one by one, and thrown down on the planks, stamped on with the heel till broken in pieces, and then kicked into the water. At the same time, other coolies were employed in the trenches, with hoes and broad spatulas, busily engaging in beating and turning up the opium from the bottom of the vat. Other coolies were employed in bringing salt and lime, and spreading them profusely over the whole surface of the trench. The third was about half filled, standing like a distiller’s vat, not in a state of active fermentation, but of slow decomposition, and was nearly ready to be drawn off. This was to be done through a narrow sluice, opened between the trench and the creek. This sluice was two feet wide, and somewhat deeper than the floor of the trench. It was furnished with a screen, made fine like a sieve, so as to prevent any large masses of the drug from finding their way into creek. Loo told us that the destruction of the opium, which commenced on the 3d, would be completed by the 23d.

At one point, someone was caught trying to abscond with some of the opium. He was beheaded then and there. Not long afterward, the First Opium War began in earnest.

Curb Your Enthusiasm

An illustration for George du Maurier’s Trilby, serialized in Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, July 1894

In a recent Science of Us post, Melissa Dahl investigates the evolution of the exclamation mark. As one grammarian tells her, “Exclamation points are becoming the standard after salutations and happy or eager statements such as ‘I’m looking forward to seeing you’ ... It almost seems mandatory in e-mail.”

While few can deny that an unexclamated text reads as terse today, the overuse of the exclamation mark dates to far before the dawn of Seinfeld, let alone the proliferation of electronic communiques. Most recently, I was struck by George du Maurier’s promiscuous use of punctuation in his 1894 novel, Trilby.

To the extent that anyone talks about Trilby today, it is usually because the book was the genesis of the term svengali; because said Svengali is an egregiously anti-Semitic caricature; or just because the author was the grandfather of Daphne. A century ago, it was known for its depiction of bohemian Paris and the portrait of its title character, a sexually liberated but pure-hearted Englishwoman who falls prey to the sinister machinations of Svengali.

Svengali—who does indeed practice mesmerism, as well as speaking a really-hard-to-read German-accented French that is written out phonetically—spends a lot of the novel monologuing in a villainous manner:

And, ach! what a beautiful skeleton you will make! And very soon, too, because you do not smile on your madly loving Svengali. You burn his letters without reading them! You shall have a nice little mahogany glass case all to yourself in the museum of the École de Médecine, and Svengali shall come in his new fur-lined coat, smoking his big cigar of the Havana, and push the dirty carabins out of the way, and look through the holes of your eyes into your stupid empty skull, and up the nostrils of your high, bony sounding-board of a nose without either a tip or a lip to it, and into the roof of your big mouth, with your thirty-two big English teeth, and between your big ribs into your big chest, where the big leather lungs used to be, and say, “Ach! what a pity she had no more music in her than a big tom-cat!” And then he will look all down your bones to your poor crumbling feet, and say, “Ach! what a fool she was not to answer Svengali’s letters!”

Then, some twenty pages later,

But you are not listening, sapperment! great big she-fool that you are—sheep’s-head! Dummkopf! Donnerwetter! you are looking at the chimney-pots when Svengali talks! Look a little lower down between the houses, on the other side of the river! There is a little ugly grey building there, and inside are eight slanting slabs of brass, all of a row, like beds in a school dormitory, and one fine day you shall lie asleep on one of those slabs—you, Drilpy, who would not listen to Svengali, and therefore lost him! … And over the middle of you will be a little leather apron, and over your head a little brass tap, and all day long and all night the cold water shall trickle, trickle, trickle all the way down your beautiful white body to your beautiful white feet till they turn green, and your poor, damp, draggled, muddy rags will hang above you from the ceiling for your friends to know you by; drip, drip, drip! But you will have no friends … And people of all sorts, strangers, will stare at you through the big plate-glass window—Englanders.

This gets old pretty fast. And yet the story clips along, thanks partly to all the jolly Left-Bank color, but also to du Maurier’s deployment of the exclamation mark. The narrator is, like Svengali, given to long declamations, and these are liberally strewn with tokens of his enthusiasm. Generally, he will start off fairly calm, warm to his topic, and by the end of the paragraph have become nearly hysterical. To wit,

It is a wondrous thing, the human foot—like the human hand; even more so, perhaps; but, unlike the hand, with which we are so familiar, it is seldom a thing of beauty in civilized adults who go about in leather boots or shoes. So that it is hidden away in disgrace, a thing to be thrust out of sight and forgotten. It can sometimes be very ugly indeed—the ugliest thing there is, even in the fairest and highest and most gifted of her sex; and then it is of an ugliness to chill and kill romance, and scatter love’s young dream, and almost break the heart. And all for the sake of a high heel and a ridiculously pointed toe—mean things, at the best! Conversely, when Mother Nature has taken extra pains in the building of it, and proper care or happy chance has kept it free of lamentable deformations, indurations, and discolorations—all those gruesome boot-begotten abominations which have made it so generally unpopular—the sudden sight of it, uncovered, comes as a very rare and singularly pleasing surprise to the eye that has learned how to see! Nothing else that Mother Nature has to show, not even the human face divine, has more subtle power to suggest high physical distinction, happy evolution, and supreme development; the lordship of man over beast, the lordship of man over man, the lordship of woman over all!

His paeans are not confined to the beauty of the human foot: also worthy of many exclamation marks are love, sausages, the antics of art students, and feminine virtue. Here he is on some kind of bohemian pension in Chelsea:

There were several such houses in London then—and are still—thank Heaven! And Little Billee had his little billet there—and there he was wont to drown himself in waves of lovely sound, or streams of clever talk, or rivers of sweet feminine adulation, seas! oceans!—a somewhat relaxing bath!—and forget for a while his everlasting chronic plague of heart-insensibility, which no doctor could explain or cure, and to which he was becoming gradually resigned—as one does to deafness or blindness or locomotor ataxia—for it had lasted nearly five years!

(Du Maurier is also fond of dashes.)

One wonders whether du Maurier’s stylistic excitability was a holdover from the many years he logged as a Punch cartoonist. One also wonders what his boon chum Henry James made of his approach to punctuation. What can’t be questioned is that it worked: Trilby was a sensation. There was a stage adaptation—the lead actress sported a soft felt chapeau that we still know as the trilby—but there were also songs, dances, soap, toothpaste, and a city in Florida. Svengali also served as the inspiration for the Phantom of the Opera. Apparently, the author grew to resent Trilby’s long shadow, but it made him rich.

I can think of no better way to close this than as du Maurier chose to end Trilby itself:

A little work, a little play

To keep us going—and so, good-day!

A little warmth, a little light

Of love’s bestowing—and so, good-night!

A little fun, to match the sorrow

Of each day’s growin—and so, good-morrow!

A little trust that when we die

We reap our sowing! And so—good-bye!

Swat with Scruple

Balthasar van der Ast, Flowers and Fruit, c. 1620

From “Why We Hate Insects,” an essay by Robert Lynd, collected in his 1921 book, The Pleasures of Ignorance.

It has been said that the characteristic sound of summer is the hum of insects, as the characteristic sound of spring is the singing of birds. It is all the more curious that the word “insect” conveys to us an implication of ugliness. We think of spiders, of which many people are more afraid than of Germans. We think of bugs and fleas, which seem so indecent in their lives that they are made a jest by the vulgar and the nice people do their best to avoid mentioning them. We think of blackbeetles scurrying into safety as the kitchen light is suddenly turned on—blackbeetles which (so we are told) in the first place are not beetles, and in the second place are not black …

There are also certain crawling creatures which are so notoriously the children of filth and so threatening in their touch that we naturally shrink from them. Burns may make merry over a louse crawling in a lady’s hair, but few of us can regard its kind with equanimity even on the backs of swine. Men of science deny that the louse is actually engendered by dirt, but it undoubtedly thrives on it. Our anger against the flea also arises from the fact that we associate it with dirt. Donne once wrote a poem to a lady who had been bitten by the same flea as himself, arguing that this was a good reason why she should allow him to make love to her. It is, and was bound to be, a dirty poem. Love, even of the wandering and polygynous kind, does not express itself in such images. Only while under the dominion of the youthful heresy of ugliness could a poet pretend that it did. The flea, according to the authorities, is “remarkable for its powers of leaping, and nearly cosmopolitan.” Even so, it has found no place in the heart or fancy of man. There have been men who were indifferent to fleas, but there have been none who loved them, though if my memory does not betray me there was a famous French prisoner some years ago who beguiled the tedium of his cell by making a pet and a performer of a flea. For the world at large, the flea represents merely hateful irritation. Mr W. B. Yeats has introduced it into poetry in this sense in an epigram addressed “to a poet who would have me praise certain bad poets, imitators of his and of mine”:

You say as I have often given tongue

In praise of what another’s said or sung,

’Twere politic to do the like by these,

But where’s the wild dog that has praised his fleas?

[…] There are insects that make us feel that we are in presence of the uncanny. Many of us have this feeling about moths. Moths are the ghosts of the insect world. It may be the manner in which they flutter in unheralded out of the night that terrifies us. They seem to tap against our lighted windows as though the outer darkness had a message for us. And their persistence helps to terrify. They are more troublesome than a subject nation. They are more importunate than the importunate widow. But they are most terrifying of all if one suddenly sees their eyes blazing crimson as they catch the light. One thinks of nocturnal rites in an African forest temple and of terrible jewels blazing in the head of an evil goddess—jewels to be stolen, we realize, by a foolish white man, thereafter to be the object of a vendetta in a sensational novel … It is for us the thing that flies by night and eats holes in our clothes. We are not even afraid of it in all circumstances. Our terror is an indoors terror. We are on good terms with it in poetry, and play with the thought of the desire of the moth for the star.

We remember that it is for the moths that the pallid jasmine smells so sweetly by night. There is no shudder in our minds when we read:

And when white moths were on the wing,

And moth-like stars were flickering out,

I dropped the berry in a stream,

And caught a little silver trout.

No man has ever sung of spiders or earwigs or any other of our pet antipathies among the insects like that. The moth is the only one of the insects that fascinates us with both its beauty and its terror … There are scarcely more diseases in the human body than there are kinds of insects in a single fruit tree. The apple that is rotten before it is ripe is an insect’s victim, and, if the plums fall green and untimely in scores upon the ground, once more it is an insect that has been at work among them. Talk about German spies! Had German spies gone to the insect world for a lesson, they might not have been the inefficient bunglers they showed themselves to be. At the same time, most of us hate spies and insects for the same reason. We regard them as noxious creatures intruding where they have no right to be, preying upon us and giving us nothing but evil in return. Hence our ruthlessness. We say: “Vermin,” and destroy them. To regard a human being as an insect is always the first step in treating him without remorse. It is a perilous attitude and in general is more likely to beget crime than justice. There has never, I believe, been an empire built in which, at some stage or other, a massacre of children among a revolting population has not been excused on the ground that “nits make lice.” “Swat that Bolshevik,” no doubt, seems to many reactionaries as sanitary a counsel as “Swat that fly.” Even in regard to flies, however, most of us can only swat with scruple. Hate flies as we may, and wish them in perdition as we may, we could not slowly pull them to pieces, wing after wing and leg after leg, as thoughtless children are said to do. Many of us cannot endure to see them slowly done to death on those long strips of sticky paper on which the flies drag their legs and their lives out—as it seems to me, a vile cruelty.

A distinguished novelist has said that to watch flies trying to tug their legs off the paper one after another till they are twice their natural length is one of his favorite amusements. I have never found any difficulty in believing it of him. It is an odd fact that considerateness, if not actually kindness, to flies has been made one of the tests of gentleness in popular speech. How often has one heard it said in praise of a dead man: “He wouldn’t have hurt a fly!” As for those who do hurt flies, we pillory them in history. We have never forgotten the cruelty of Domitian. “At the beginning of his reign,” Suetonius tells us “he used to spend hours in seclusion every day, doing nothing but catch flies and stab them with a keenly sharpened stylus. Consequently, when someone once asked whether anyone was in there with Cæsar, Vibius Crispus made the witty reply: ‘Not even a fly.’” … One of the most agonising of the minor dilemmas in which a too sensitive humanitarian ever finds himself is whether he should destroy a spider’s web, and so, perhaps, starve the spider to death, or whether he should leave the web, and so connive at the death of a multitude of flies. I have long been content to leave Nature to her own ways in such matters … The ladybird, the butterfly, and the bee—who would put chains upon such creatures? These are insects that must have been in Eden before the snake. Beelzebub, the god of the other insects, had not yet any engendering power on the earth in those days, when all the flowers were as strange as insects and all the insects were as beautiful as flowers.

Robert Lynd (1879 – 1949) was an Irish writer and essayist.

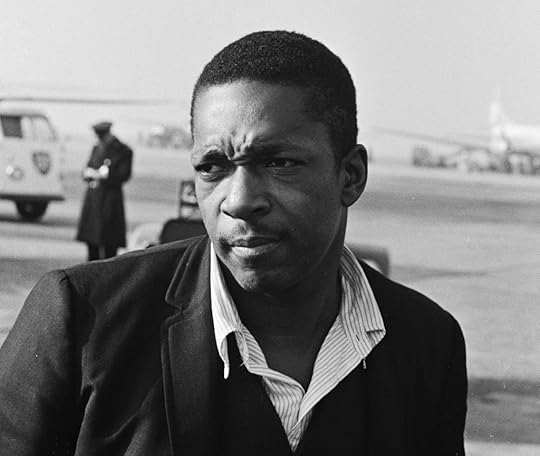

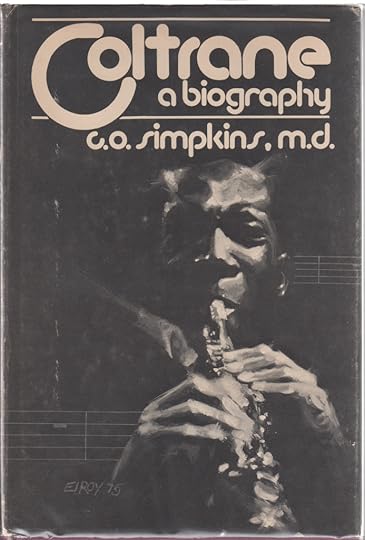

An Absolute Truth: On Writing a Life of Coltrane

A few years ago I found a used, first-edition hardcover of Dr. Cuthbert Ormond Simpkins’s 1975 book, Coltrane: A Biography, online for $150. I had long admired its feverish, street-pulpy story about the saxophonist John Coltrane, whose powerful music increasingly seemed capable of altering one’s consciousness before he died in 1967, at age forty. Posthumously, the mythology and exaltation of Coltrane, as well as his musical influence, only grew. But by that point, Simpkins had already researched and written Coltrane’s story, expressing an uncompromising, unapologetic black voice rarely found in the annals of jazz before or since.

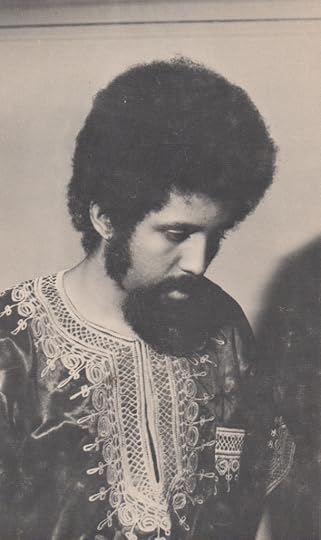

I forked up the money for the hardback. The dust jacket bears an impressionistic black-and-white painting of Coltrane playing soprano saxophone. The rounded, sans serif font resembles that of Soul Train, the popular TV show that premiered in 1971. On the back cover is a photograph of a young, Simpkins sporting a West African dashiki shirt, a high Afro, thick sideburns, and a beard.

Simpkins’s idea for the book was conceived during his senior year at Amherst, in 1969; he worked on it during breaks from Harvard Medical School in the early seventies. Simpkins possessed no credentials in jazz or literature. The publisher of the original hardcover is Herndon House; quick Google and Library of Congress searches yield no other books from that publisher. There are identical typographical errors in all three editions—first and second hardback, and paperback. (Sarah Vaughan’s name, for instance, is spelled once as “Vaughn,” and Nesuhi Ertegun appears as “Nehusi.”) All indications point to the book having been self-published, the original piece preserved in two later editions.

The writer Stanley Crouch remembers when Coltrane: A Biography first came out. “In the black jazz world, the arrival of the Simpkins book was a major event,” he told me. There had been a book-launch party at the New Lafayette Theater in Harlem during which saxophonists Sam Rivers and George Braith played. In the New York Times, Gary Giddins wrote a positive review, favoring the book to another Coltrane biography, by J.C. Thomas, that came out the same year. It was a promising, gutsy start for the young writer, but Simpkins’s goal was not to advance a literary career; he never wrote another jazz history. He forged one book on John Coltrane, then moved on to a career in medicine.

The writer Stanley Crouch remembers when Coltrane: A Biography first came out. “In the black jazz world, the arrival of the Simpkins book was a major event,” he told me. There had been a book-launch party at the New Lafayette Theater in Harlem during which saxophonists Sam Rivers and George Braith played. In the New York Times, Gary Giddins wrote a positive review, favoring the book to another Coltrane biography, by J.C. Thomas, that came out the same year. It was a promising, gutsy start for the young writer, but Simpkins’s goal was not to advance a literary career; he never wrote another jazz history. He forged one book on John Coltrane, then moved on to a career in medicine.

Coltrane: A Biography has long been out of print, but its significance has become even more apparent since then. Leonard Brown, a professor of music and African American Studies at Northeastern University and the author of John Coltrane and Black America’s Quest for Freedom, told me, “The Simpkins book on Coltrane was written from the perspective of a young, twenty-something black man in the early 1970s, a critical, chaotic time in American history in general and African-American history in particular. That perspective is hard to access today. You can’t find it in a university or conservatory setting.”

New York Times music critic Ben Ratliff, who wrote Coltrane: The Story of a Sound, echoed Brown: “In the early 1970s jazz had become broken, really within a ten-year period, and Coltrane’s death had something to do with that. I have great respect for Simpkins’s book because it is passionately researched and great-souled. There’s a feeling in the book of something urgent being at stake. I think Simpkins, who, importantly, was neither a journalist nor a musician, threw himself into it. The ways in which his book might be perceived as dated today—the detours into poetry, for example—might yet be ways in which it stays fresh.”

* * *

The day after Christmas, in 2012, I packed my rented Chevrolet Impala in New Orleans and drove five hours northwest to Shreveport. My plan was to spend a couple of days with Dr. Cuthbert Simpkins, Coltrane biographer and trauma surgeon.

Simpkins was born in Shreveport in 1947 and returned there in 2004 to be head of trauma surgery at LSU Health Shreveport, the former Confederate Memorial Hospital. His parents—Dr. C.O. Simpkins, a former dentist, and Dorothy Herndon Simpkins—are still alive and residing (separately—they divorced in the 1970s) in Shreveport. They were civil rights pioneers in the fifties and sixties, organizing local efforts with national leaders such as Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Ella Baker.

After dropping my bags at a bed-and-breakfast, I drove across town to the ranch-style house Simpkins shares with his wife, Diane, in a forested suburban neighborhood. Tuffy, as he’s known to family and friends, was wearing green hospital scrubs. He had just returned home from a shift in the intensive care unit at Rapides Regional Medical Center in nearby Alexandria.

In the kitchen, I met Tuffy’s mother, Dorothy, now eighty-six and recovering from a stroke. She can walk slowly with help and can acknowledge conversation by moving her head and smiling. She seemed delighted by our company, tapping her feet to the music on the stereo (it was Cannonball Adderley). When Coltrane: A Biography was published, Simpkins named his press, Herndon House, after her.

Before my trip I had read about Simpkins’s parents in several civil rights histories. Dorothy and C.O. were unrelenting, at times militant advocates for equal rights. Dr. Simpkins was known to carry a gun, including one in the shape of an ink pen and loaded with a single bullet. (“Nonviolent tactics sometimes worked better when you were carrying a gun,” he told me later.) In the 1950s Dorothy was one of the first black people in Shreveport to refuse to move from the front of a city bus. The police once pulled her from a bus and arrested her in front of the troupes of Boy Scouts and Cub Scouts she was escorting. In the early sixties, when Tuffy was a teenager, two of the family’s houses were bombed by white supremacists.

After only a half hour of conversation, it was clear that Tuffy and Diane operate as a unit. I asked how they met. They laughed together, looked at each other as if to ask, Are you going to tell this story or am I? “We met at the main post office in New Brunswick, New Jersey, in 1982,” Tuffy began. “I wanted to write a book about Russia. I didn’t know anything about Russia, so I knew I had to go there and learn the language, all the nuances and dialects, and I needed a passport. I walked in the post office and noticed Diane immediately. I got in line for her window. She was beautiful and I saw that she treated people really well, and she had a beautiful voice and a wonderful smile. I asked for her phone number. She said, I don’t give customers my phone number. I gave her my number. She never called.

“So, one day I put on my best suit, cleaned myself up, bought a dozen roses, and went back to the post office. I had just reread Cyrano de Bergerac, so I wrote a poem in that romantic style and gave that to her, too. And I gave her ten phone numbers. I gave her my father’s phone number, my mother’s phone number, my brother’s phone number, and a few friends’. I wrote her a note saying, If you don’t trust me enough to call me, call these other people as references. She waited about two days to call. The rest is history. I never got around to my book on Russia.”

They laughed and Tuffy looked at me: “On our first date I learned she already knew about Monk and Sun Ra.” He shrugged his shoulders. “What could I do? I was done.”

I asked Tuffy when his impulse to write about Coltrane came about. He responded:

I was working on my senior honors thesis in chemistry at Amherst in 1969. My girlfriend at the time, Shela Anderson, was a freshman at Smith College. She noticed that whenever I listened to Coltrane I took notes on pieces of paper. I listened to a lot of music but it was only Coltrane that moved me to write down my thoughts and feelings. Shela was a talented writer and she suggested that I keep my notes. I had been throwing the scraps of paper away, so she gave me spiral notebook to write in. After one night of thinking about the formulas I was deriving for my chemistry thesis, I woke up and declared to myself that I was going to write a book on Coltrane. I wanted to know who John Coltrane was. I wanted to know where his music came from.

* * *

“Trane” might as well have come from Krypton. The man “John Coltrane” is hard to locate in other people’s memories today, or in the existing studio or club recordings of his music, which document the known pinnacles, not the fits and starts and hours and years of rigor and anxieties. A list of facts doesn’t help much, either: his formative years in North Carolina are difficult to excavate and easy to summarize or skip over. Plus, the iconographic mid-century jazz photography makes Coltrane look seven feet tall (a 1947 Naval photograph shows him to be under five-foot-ten, a normal-size man). The legend is overwhelming.

Distance, distraction, and apathy make the devastating chaos of the 1960s and early seventies difficult to feel today, too. Malcolm X was assassinated in 1965. Martin Luther King was assassinated in 1968. The Vietnam War was going nowhere. The country was on fire, literally in some places, and reactionary forces clamped down, creating a weird climate of both chaos and torpor. In the 1972 presidential election, the sitting president, Nixon, carried forty-nine states.

Tuffy Simpkins began researching Coltrane: A Biography in 1969 and published it in 1975. During that span, he interviewed more than a hundred subjects, almost all of them black: musicians in New York, Coltrane’s childhood friends and schoolteachers in North Carolina. The tone he found for his book is imbedded in Coltrane’s cultural moment, which was described by the late poet, playwright, and performance artist Sekou Sundiata in Steve Rowland’s outstanding five-hour radio documentary, Tell Me How Long Trane’s Been Gone:

People can mistake being fierce for being angry, you know, and they are not the same, and I think there was something fierce about what [Coltrane] was doing, something driven about what he was doing, you know, and I think that was in tune with the times, you know. When I speak about this consciousness, and this developing consciousness, developing at a very rapid rate, a very rapid pace, affecting every segment of society, certainly every segment of the black community. There’s sort of a breathlessness to the sixties and the seventies, as if in fact there’s not enough time to get it all said, to get it all done, a sense of urgency that it has to happen now.

* * *

The next morning in Shreveport, Tuffy and Diane picked me up at the bed-and-breakfast and drove me to the suburban house where the elder Dr. Simpkins lives with his wife. Along the way, we meandered through the old neighborhood where the family lived through those years of civic strife. As with many black neighborhoods across America in the sixties and seventies, this one was fissured by a new downtown highway bypass, part of urban renewal, or “Negro removal,” as James Baldwin called it.

We stopped at Dr. Simpkins’s old dental office, and went inside the back room where he held strategy meetings with dissenters and activists a half century ago. We also saw the vacant lot where the almost-finished Simpkins family home was bombed in 1962. (A Jet magazine story on the bombing valued the home at fifty thousand dollars—about four hundred thousand in 2013 money.) We then drove into an affluent neighborhood on Cross Lake and pulled into the driveway of the home of Tuffy’s father and stepmother. The large house features a patio with a swimming pool and cabana. Below is a boat dock on the lake.

The elder Dr. Simpkins could pass for a man ten or fifteen years younger. Over a lunch of sandwiches and high-end rum, I listened to the memories. Dr. Simpkins told this story about his grandfather, Oscar Seymour “Seeb” Simpkins, who owned valuable real estate in nearby Mansfield: “When some whites wanted to take the choice land he lived on, he got his guns and told a white friend who came to warn him, as he took a swig of whiskey, You tell ’em to hurry up cause I’m damn tired of waiting.” They never came and Seeb kept his land.

In 1962, the second Simpkins house was bombed, this one a vacation home on a lake. Dr. Simpkins was in the crosshairs of white supremacists in northwest Louisiana who saw him as the principle agitator in that region. As a result, or as part of a concerted effort, the company insuring his dental practice canceled his policy. Dr. Simpkins was pulled in two directions: his instinct was to stay home and fight for equality, but he also wanted to send his kids to college. The kids’ safety and well-being came first, so Dr. Simpkins gathered the family in the living room and told them they’d be moving.

The family eventually settled at 197th Street and 110th Avenue in Queens, and Dr. Simpkins set up his practice there. (In 1990, he moved back to Shreveport and was elected into the Louisiana House of Representatives.) Naima Coltrane, John’s first wife, owned a dashiki shop a few blocks away, on Hollis Avenue. She and her daughter, Saida, became Dr. Simpkins’s patients. When Tuffy expressed interest in writing about Coltrane, his father encouraged him to reach out to Naima; she was the first person he interviewed for the book, and she later gave Tuffy contact information for many of his sources.

* * *

In the car, I asked Tuffy about his process for writing Coltrane: A Biography.

I know I made many mistakes, but I had to write regardless of what people might say about it or critics might think about it. I wanted to capture the feel of Coltrane, who he was, what his music sounded like, what the times felt like—I wanted to use whatever mode of writing was necessary to capture that feeling. I wanted the book to palpitate, to move and feel, to have blood running through it. To be Coltrane, as much as a book can be somebody.

I was concerned about how white people would feel about it. I thought it might offend them. Some of the things—the anger, the bitterness of the black experience—were expressed in a tough manner. But I decided I wasn’t going to change anything. I just let it be out there like it was.

The audience I developed in my mind’s eye was an audience of black children, as though I was talking to my own children. Something about writing for children imposed an absolute truth in my effort. I thought that was the best way for me to put the truth out there without any compromise.

* * *

The practice of remaking a Broadway show tune—a staple of white American popular culture at mid-century—into something more exotic, by exploring and taking apart the tune’s melodic, harmonic, and chordal structures and improvising around those structures before putting them back together, was the underpinning of postwar jazz, both white and black. It had hints of scandal and risk: exploiting or one-upping a standard pop song by Gershwin or Cole Porter or Howard Arlen was hip, underground entertainment. The exercise reached its zenith in 1961, when Coltrane covered “My Favorite Things,” written by Rodgers and Hammerstein for the 1959 Broadway production of The Sound of Music. He turned a two-minute forty-four second song into a thirteen-minute warhorse of dominion.

But that was never Coltrane’s motivation, and he proved it in the six years after “My Favorite Things” by developing music that was not based on preexisting chords but on modes and scale structures that gave him more freedom. The elements that mattered to him the most were rhythm and pure sound, influenced by music from Africa and India. One tune might span an entire set in a club, seventy-five minutes or more. For many listeners, Coltrane provided a model for breaking free from constraints, for evolving into a spiritual being free of Western conventions. In 1965, his quartet held residency at New York’s downtown club, the Half Note, and owner Mike Caterino reported that at least ninety percent of the audience was black, a much higher number than other black musicians drew in his club at the time. That moment is long gone, but thankfully preserved, in part, by the many recordings Coltrane left behind.

* * *

The opening paragraph of Coltrane: A Biography reads like a poetic note jotted by Simpkins on scratch paper in his final semester at Amherst.

Moments. Moments of great emotion never die. They are like purple diamonds swirling through the ages, or lavender pulsation burning, magnificently, about the mortal universe.

Four paragraphs later, he writes,

Through courage comes freedom. It takes courage to express what you feel, to meditate as you need. Emotional depth and mastery of technique rarely throb within a single pulsation. John Coltrane possessed, and was possessed, by this gift. His story begins with his ancestors.

The book goes on to describe Coltrane’s family background with emphasis on his maternal grandfather, Reverend William Wilson Blair, an A.M.E. Zion minister and relentless, trailblazing leader for equal rights:

(Re. Blair) denounced the white man from the pulpit, teaching that we should work together for our common advancement. Some Blacks thought being so straightforward with “important” white folks was improper, and that conditions for Blacks need not be improved. Others shuddered as he unleashed attacks with all the fury of the holy ghost.

The analog between Rev. Blair and Dr. C.O. Simpkins, the gun-carrying dentist, is clear but unstated in the book, as is the prominence of Coltrane’s family in High Point in the 1930s with the Simpkins family’s in Shreveport in the 1950s.

The strength of the book comes from firsthand stories Simpkins obtained through his interviews. He tells the story of a teenage Coltrane and his best friend, James Kinzer, one day secretly following home John’s schoolyard sweetheart, who lived on the poorer side of High Point. After she entered her house, the two boys knocked on her door. When she answered, she burst into tears, ashamed and embarrassed by her poverty.

Another story comes from Calvin Massey, a trumpeter and friend of Coltrane’s from Philadelphia, where Coltrane moved with his family after graduating from high school, in 1944. In the late forties, a black drummer named Nasseridine, a converted Muslim and close friend of Coltrane’s, was beaten to death by white Philadelphia police after being confronted while kneeling on his prayer rug on a street corner. In another story from Massey, he and Coltrane were put in jail by Philadelphia police simply for “corner lounging.”

* * *

Simpkins received early interest in his book from established editors and publishers, but after several false starts, he took control of the process and self-published it. He knew that would mean limited distribution—he printed two thousand hardcover copies—but he had a singular vision for the book, a particular document he wanted to leave behind.

The last edition was published in 1989, when Black Classic Press reissued ten thousand paperback copies. Though Simpkins isn’t anxious to author a new edition, he says that if he did, he’d want it published exactly as it was the first time, with the same handful of misspellings and typographical errors and no index. The book is a piece for the time capsule.

* * *

At Tuffy’s house, I marveled at the box of his original interview tapes that he brought out of a closet. He interviewed iconic saxophonists Ornette Coleman and Sonny Rollins separately on the same day, June 1, 1972, two weeks before five men were captured during the second Watergate Hotel burglary and a month before the movie Superfly was released.

Listening to the tapes today, a prevailing image emerges for me: a young black medical student finds his way into all of these different living rooms around New York and in North Carolina in the early 1970s. He sits for hours, listening. I can hear James Kinzer in High Point telling the story about Coltrane’s teenage girlfriend; I can hear Calvin Massey telling about the police murder of the drummer Nasserdirine; I can hear saxophonist Jimmy Heath talking about looking into Coltrane’s coffin in the summer of 1967 and thinking to himself, “He looked like a simple boy from the country.”

Sam Stephenson is a writer working on a biography of W. Eugene Smith for Farrar, Straus and Giroux. He is author of The Jazz Loft Project. He is also a partner in the documentary company Rock Fish Stew Institute of Literature and Materials, based in Durham, North Carolina.

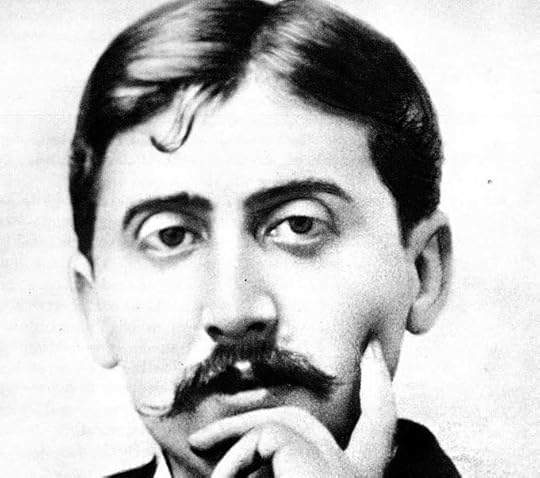

Proust Says “Pipe Down,” and Other News

Will you please be quiet, please?

In which Penguin Random House unveils its new logo and “brand identity.”

Proust’s letters to his noisy neighbors: “It seems almost too perfect that Proust, the bedridden invalid, would have sent notes upstairs, sometimes by messenger, sometimes through the post, to implore the Williamses to nail shut the crates containing their summer luggage in the evening, rather than in the morning, so that they could be better timed around his asthma attacks.”

Where are erotica writers having sex? In the doctor’s office. At the Louvre. On the Haunted Mansion ride at Disney World.

Making an unlikely appearance in the Times Op-Ed section this morning: our Art of Nonfiction interview with Adam Phillips.

“When I find myself having to defend the narrative force of video games, I like to give the example of a real experience I had in my childhood involving the game Metroid. In this science fiction adventure, we guide a bounty hunter called Samus Aran … he wears armor which covers his whole body, until, at the end, after finding and destroying the Mother Brain, Samus … removes his helmet to reveal that he is really a woman … I had controlled a woman the whole time without knowing … Narrative sublimity is possible in the medium of electronic games.”

June 2, 2014

Candy Crush

Photo: Evan Amos, via Wikimedia Commons

My brother was one of those kids who loved camp. He started young, went for years, and, when he was older, returned as a counselor. During the school year, he and his friends would periodically meet up at an Outback Steakhouse in midtown. He still attends the weddings of those friends.

There was one kid in his bunk who was the camp outcast: a physically uncoordinated know-it-all who, in the grand tradition of nerds, managed to maintain an inviolate sense of wounded superiority. His response, when taunted, was to say—with an irony that was surely intended to be devastating—“You’re so kind.” You can imagine how effective this was.

I guess my brother was nice to him, in an offhand sort of way. Maybe he just wasn’t actively cruel. All I know is, when we went up there on family visiting day, this kid wouldn’t leave him alone. Mostly he stood around, nearby. But several times he appeared at my brother’s shoulder and held out a hand, silently proffering candy: Airheads, Pop Rocks, those long, flat Jolly Ranchers. While I found the whole thing kind of weird, my brother seemed to take it as his due.

As kids, we are told to avoid grownups bearing candy. Presumably that’s because they’re using it as a lure, or maybe because the candy itself is tainted. (Or, in some cases, because it’s propaganda.) To kids, candy is currency—precious, limited, usually out of reach. No wonder it’s so appealing, even when we’ve outgrown those sugar-craving juvenile taste buds.

For grownups, the exchange of candy is less straightforward. There is implicit in such transactions the tacit understanding that the adult recipient could, if he so chose, purchase candy for himself, and this complicates matters. Also, we don’t tend to want it as much.

Kids are not wrong in thinking that adults have ready access to sweets. There is much free, impersonal, dish candy in a grown-up’s life—Tootsie Rolls on desks, Nips and Starlite Mints at grandmas’ houses, those delicious little liquid-centered strawberry things at the dry-cleaner’s, a jelly-filled mint by a diner register. This is not weird. But in these cases, the choice is yours; there are no strings attached other than those of straightforward commerce or simple hospitality.

Then there are people actively offering candy: even putting aside the risks of abduction and poisoning, this is never, ever not suspect.

The other day, I was sitting with a friend at a bar in Brooklyn. A random dude plopped himself down next to us and then, with no warning, abruptly slapped two peppermint patties down on the table in front of us with a confrontational air.

“Thanks,” we murmured nervously, and pocketed them to be polite.

A moment later, he smashed his phone down on our table.

“Charlie Chaplin and Albert Einstein!” he said, with the same vague air of menace. We looked at the screen; there they were.

“Wow,” I said. “What were the circumstances of their meeting?”

“I have no fucking idea!” he shouted.

Later, we saw that he had a really big box full of peppermint patties in his bag.

If only human connection were this easy.

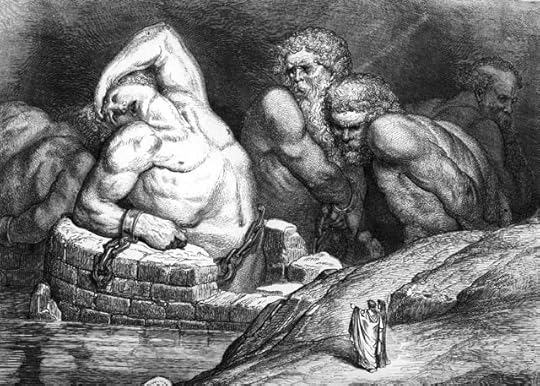

Recapping Dante: Canto 31, or Dante the Television Writer

Gustave Doré, Canto 31

We’re recapping the Inferno. Read along! This week: the thirty-first canto as explained by a breathless contemporary TV critic.

By now it is clear that this season’s sleeper star is the breakout show-runner, Dante Alighieri. His show The Inferno, an unlikely gem of narratological genius, has consistently stood out from the televisual pack, relying for the most part on the rarefied taste of its audience and the poignant, lyrical style of the head writer. This most recent episode, canto 31, is no exception.

This divine segment uses, as ever, a canny rhetorical device to dispense with exposition: the question. In this case, our hero, Dante, entering the next circle of hell, gazes through a thick fog, through which he can faintly perceive the outline of various towers. So what does he do? He asks a question about them, of course, and his companion Virgil helpfully informs him—and us—that these are giants, not towers. Simple! Elegant! Where other shows go in for flash and gimmickry, The Inferno just tells us what’s what.

Likewise, the show’s oft-criticized habit of alluding to classic texts is, in this viewer’s opinion, a refreshing break from the crude, pseudo-mythological subtext of HBO’s Game of Thrones. This week, Dante compares the sound of a bugle in hell to the resounding bellow of Roland’s horn inthe Chanson de Roland, the French epic poem: an apt comparison, even if it’s lost on a contemporary audience.

As Dante and Virgil continue through the infernal domain of giants, the first giant they encounter begins speaking in gibberish: Raphèl maì amècche zabì almi. It’s a phrase that fans around the world have been frantically attempting to decode, to no avail. After all, the giant who spits out this nonsense is Nimrod, who built the tower of Babel. (It’s my opinion that Dante means to use hell as a sort of moral landscape, in which punishments reflect a sinner’s crime—but this is pure speculation.) The ultimate genius of The Inferno may be that it brings an intellectual component to one of the oldest adventure stories in history. Odysseus and Aeneas traveled through hell, and here Dante has crafted a Christian notion of the underworld without disregarding these ancient traditions.

At the end of this episode, Dante and Virgil speak with a far more reasonable giant, who takes them into his hand and carries them, lowering them gently into hell’s final circle. Of course, the action breaks off there—Dante knows a thing or two about cliffhangers. And so we wait with bated breath for the next installment of this national treasure.

Never has an adventure story been so intellectually rewarding, and seldom is a theological and lyrical masterpiece ever so thrilling to read. It is probably true that there won’t be a Dante line of clothing at Banana Republic, and there certainly won’t be a fleet of Dante cosplayers at next year’s Comic Con. But I feel certain that the lone fan will show up in a red bonnet, and that a discerning few will get the reference right away, even though the shortsighted network will probably cancel the show. In time the one season of The Inferno will be remembered as fondly as all seasons of Breaking Bad. AMC might have had Walter White, but Dante has Lucifer himself.

To catch up on our Dante series, click here.

Alexander Aciman is the author of Twitterature. He has written for the New York Times, Tablet, the Wall Street Journal, and TIME. Follow him on Twitter at @acimania.

Take a Walk with Our Summer Issue

That adorable canine on the cover is Boo, a shaggy brown Brussels griffon and an habitué of our old loft on White Street. Boo’s owner (and portraitist) is Raymond Pettibon, whose portfolio, “Real Dogs in Space,” is at the center of issue 209, fit for consumption in the dog days of summer.

That adorable canine on the cover is Boo, a shaggy brown Brussels griffon and an habitué of our old loft on White Street. Boo’s owner (and portraitist) is Raymond Pettibon, whose portfolio, “Real Dogs in Space,” is at the center of issue 209, fit for consumption in the dog days of summer.

Then there’s our interview with Joy Williams—whose stories have appeared in The Paris Review since 1969—on the Art of Fiction:

What a story is, is devious. It pretends transparency, forthrightness. It engages with ordinary people, ordinary matters, recognizable stuff. But this is all a masquerade. What good stories deal with is the horror and incomprehensibility of time, the dark encroachment of old catastrophes—which is Wallace Stevens, I think. As a form, the short story is hardly divine, though all excellent art has its mystery, its spiritual rhythm.

And in the Art of of Poetry No. 98, Henri Cole discusses his approach to clichés (“I like the idea of going right up to the edge of cliché and then stopping”), his collages, and his contempt for the sentimental:

Oh, I hate sentimentality. Heterosexual men are more susceptible to it than women, because middle age keeps telling them they’re gods. This is not true for women, however, who are often discarded. Is it possible that we can more readily see the bleakness of the human condition if life has been a little harder for us? Nothing kills art faster than sentimentality.

There’s also an essay by Andrea Barrett; fiction from Zadie Smith, J. D. Daniels, Garth Greenwell, Ottessa Moshfegh, and Shelly Oria; the third installment of Rachel Cusk’s novel Outline, with illustrations by Samantha Hahn; and new poems by Henri Cole, Charles Simic, Ange Mlinko, Nick Laird, Rowan Ricardo Phillips, Les Murray, Adam Kirsch, Jane Hirshfield, and Thomas Sayers Ellis.

It’s an issue that, like Boo, commands immediate and frequent affection, and will keep you enthralled for years to come.

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers