The Paris Review's Blog, page 695

June 12, 2014

Daymares, and Other News

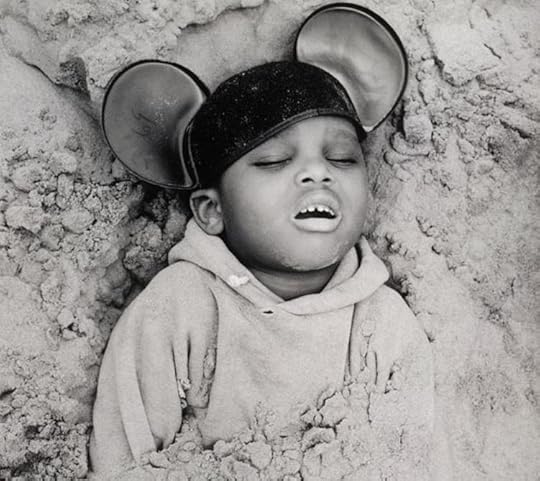

Arthur Tress, Child Buried in Sand, Coney Island, 196o, black-and-white photograph. Via Gothamist.

“I really don’t know what I’m supposed to do … But as soon as I find out, I’ll do it.”

Donna Tartt’s The Goldfinch is the literary novel of the moment—but it is any good? Many, including our own Lorin Stein, respond with a resounding no. “A book like The Goldfinch doesn’t undo any clichés—it deals in them … Nowadays, even The New York Times Book Review is afraid to say when a popular book is crap.”

“Every moment of serious reading has to be fought for, planned for … A prediction: the novel of elegant, highly distinct prose, of conceptual delicacy and syntactical complexity, will tend to divide itself up into shorter and shorter sections, offering more frequent pauses where we can take time out. The larger popular novel … will be ever more laden with repetitive formulas, and coercive, declamatory rhetoric to make it easier and easier, after breaks, to pick up.”

A portfolio of Arthur Tress’s photographs, from the late sixties and seventies, of children at play in Coney Island: “Tress spoke with children about their dreams—often nightmares that involved falling, monsters, that buried alive scenario—and would then photograph them experiencing it in a safe, staged setting.”

New! From the makers of “Frank Sinatra Has a Cold,” it’s “Morrissey Has an Infection.”

June 11, 2014

These Bugaboos

One measure of a book’s influence is the mark it leaves on the vernacular. In this sense, many plaudits must go to William Styron, born today in 1925, who helped start The Paris Review and served as an advisory editor. His 1979 novel, Sophie’s Choice, has ascended into idiom, as Wikipedia and Urban Dictionary have acknowledged. The latter defines a Sophie’s Choice as “essentially a no-win situation … a choice between two unbearable options,” and gives the following example:

The loan [sic] hiker’s arm was wedged in a crevice when he slipped and fell. He didn't have the strength to release himself. Each movement wedged his arm more deeply into the crevice. After several days without food and water, he was left with a Sophie's Choice: continue to wait for help and possibly die, or use the serrated blade of his pocket knife to cut off his own arm and climb to safety before bleeding to death.

But some don’t seem to grasp the finer points of the phrase’s usage.

To wit: there has been, since 1984, a restaurant in England named Sophie’s Choice. Yes, a center of fine dining, serving “modern European cuisine and a range of wines from around the world,” which takes its name from a novel whose titular choice involves which of one’s offspring will die in a concentration camp.

“Our emphasis on good service creates a relaxed and welcoming atmosphere,” the proprietors write. Mains include roast breast of Barbary duck and char-grilled medallions of lamb rump with Cumberland sauce. They do weddings.

Styron said in his second Art of Fiction interview,

Not long ago I received in the mail a doctoral thesis entitled “Sophie’s Choice: A Jungian Perspective,” which I sat down to read. It was quite a long document. In the first paragraph it said, In this thesis my point of reference throughout will be the Alan J. Pakula movie of Sophie’s Choice. There was a footnote, which I swear to you said, Where the movie is obscure I will refer to William Styron’s novel for clarification. This idiocy laid a pall over my life for a dark brief time because it brought back all these bugaboos we have about the written word.

One can imagine that this establishment was no better received, if the author was aware of it. And I hope he was not—this is a scenario in which ignorance is bliss. If you choose to celebrate his birth tonight, best to make your reservations elsewhere.

Field Geology: An Interview with Rivka Galchen

Photo: Sandy Tait

In 2008, Rivka Galchen published Atmospheric Disturbances, a novel about a psychiatrist who wakes up one day to discover that his wife has been substituted by a replica. He subscribes to the delusions of a patient (who believes he can control the weather) to explain her disappearance. What James Wood referred to as the narrator’s first-person “double unreliability” made for a richly inconclusive novel about the confusion and mystery of love.

In her new story collection, American Innovations, Galchen, who has a background in medicine, returns us to worlds in which weird things happen. A woman watches the objects in her Brooklyn apartment leave of their own volition; a student of Library Sciences develops a third breast; refrigerated string cheese won’t stay put. Galchen’s stories suggest oppositions that dissolve in their own reversals: real things take on the patina of the artificial, while the fantastic and strange can feel more real than what we call real life. To read her stories is something like using a map without contours or coordinates; it’s impossible to plan your trip.

Over e-mail, Galchen and I discussed fiction’s relationship to field geology, the peculiarities of the short story as a form, and the allure of McDonald’s. Galchen is exhilaratingly imaginative, precise, and generous.

Why is the story a form you return to?

Short stories feel found to me—I like that about them. Of course, they’re actually not found, they’re written, just as novels are written, but they seem to have a more dense and unchangeable core than novels do, or at least it seems like one reaches the immutable core faster.

I like how stories can feel like some shiny thing on the ground, something that might be malachite, or might be a fragment of a comet, or might be a rusted old ignition. The writing process for a short story feels more like field geology, where you keep turning the thing over and over, noting its qualities in detail, hammering at it, putting it near flame, pouring different acids on it, and then finally you figure out what it is, or you just give up and mount it on a ring and have an awkward chunky piece of jewelry that seems weirdly dominating but that you for some reason like. I could be wrong about field geology here.

Where do you find your stories?

Sometimes I wonder if it’s immaterial things rooting around to find their material. For example, I have a story set in large part in a McDonald’s, there’s a young girl at the center of it, it’s in many ways a kind of love story, but why McDonald’s? McDonald’s was just sitting there in the old costume trunk of the back brain, and there was some inchoate emotion trying to play its little tune, and for whatever congregation of reasons McDonald’s was ideally useful to that emotion. It gave it the right language—probably in part because of that weird residue of how enchanting McDonald’s used to be when we were kids, how it was all an outsize luxury. And then, of course, it looks so different to us today. I think it has something to do with the question, What is it fiction is actually good at? What can it do that’s not better done with, say, a long piece of journalism, or a photograph, or a TV show? And that, in turn, has something to do with the intangible murk from which stories start to organize themselves. That intangible murk is the part that feels found to me.

The story you’re referring to, “Wild Berry Blue,” might be called realist. Does it stand apart from your more recent stories?

I guess I think of all of my stories as realism in the emotional sense. There’s this very ancient Japanese myth, the Tale of the Bamboo Cutter. In it, there’s an old, poor, childless bamboo cutter, and one day he comes across a stalk of bamboo that’s glowing. In the glowing stalk, he finds a tiny baby girl. He brings the baby home to his wife, they raise her as their own, they begin to find gold in the bamboo they harvest, the girl grows rapidly into an uncanny beauty whom even the emperor falls in love with, but she turns down all the suitors. It turns out she is from the moon, she had been sent away, but now it’s time for her to return to the place where she really belongs, she boards a spaceship and returns to the moon!

It’s weird to think of this as a story at least twelve hundred years old. But when I read it recently, I thought, This is the most straightforward description I have ever come across of what it feels like to be near a baby. They seem to come from another world, they have a strange charisma, life seems bright and rich in their aura, and one day they will leave you. Saying the baby is seven pounds, that it nurses for twenty minutes or so every three hours, its name is this, its eyelashes are that … all that realistic detail seems to just miss the whole essence of being with a baby.

In “The Lost Order,” the narrator receives a call from a man who mistakes her for a receptionist at a Chinese restaurant. She vaguely assures him his lemon chicken is on its way. What interests you about phone calls?

The disembodied language is great to work with. You get a glimpse of the bizarre little dream maps of a character. There are so many fewer physical cues coercing callers away from their misperceptions. In that sense, calls are closer to reading—the way the newspaper, for example, doesn’t cue you how to read it. The other day I was reading an article and it said, “…forces encountered hospitalities…” I paused and reread. It said, “… forces encountered hostilities…”

Your stories are funny and playful, but they don’t contain jokes.

I used to watch a lot of reruns of Get Smart, the spy-spoof show. One of the running gags was that any time Maxwell Smart or Agent 99 or Chief had something very important or top secret to communicate, they would lower the Cone of Silence, which was an actual Plexiglas-looking thing. It was ridiculous, and it also tended to malfunction in one way or another—and then a further joke was how banal so much of what was said in there was. I think that gets at the way that nearly every moment of every day, every interaction and comment, if it’s held up to the right light or juxtaposed against the right thing—well, there’s always a metaphorical cone of silence there, which makes manifest the humor already present in the words or situation.

Many of your narrators avoid difficult or complex feelings. In “The Northern Side Was Covered with Fire,” the narrator seems to care less that her husband has just left her than that he has taken with him her favorite Parmesan grater. A fan letter from a prisoner encourages her to hypothesize an explanation for a mysterious, sky-splitting incident in Siberia.

I think it’s realism. When something is very emotionally large, it’s a very human thing to walk around it for a short or long while and get a sense of its size and character. That’s my theory about what’s going on when you see people really lose it over, say, someone walking slowly on the sidewalk. Surely it’s not inherently that upsetting. So it must be that we’re catching the flak from some other, distant explosion.

Often the apparent engagement with something very large, well, I think it’s just that—only an apparent engagement. Think of the rise in spirit photography—evidence that the dead are still around!—after the Civil War and again after World War I. Or the rise of the mystery novel—something is wrong here, surely we can solve it—in Japan after World War II. It takes so, so long to even begin to understand things. Very shortly after 9/11, when I was a medical student at Mount Sinai Hospital, I would see people wearing T-shirts that said “I Survived 9/11.” There’s something darkly comic about thinking of those T-shirts now. It has to do with just how from the center of things that was, even though it was at the center.

Your narrators often seek out certainties on the Internet, which is a presence throughout the collection.

On the Internet, we’re like kids staring at our faces in spoons. But since the Internet is sort of everything, it seems like it's impossible to say anything true about it. I remember a kids’ book about a family, set in two seasons. In the wintertime, every word spoken by anyone in the family freezes. Then in the spring everyone in the family starts getting mad at one another, having bizarre ideas. It takes them awhile to realize that this is because the words from the winter have thawed, and that’s what they’re hearing—these old words from months ago. The Internet seems to me to be something like that, where what used to be passing thoughts and rumors—things intended to be spoken, intended to vanish after a moment or two—have stayed on, frozen, then thawed, then frozen, then thawed.

How do you think the idea of diagnosis affects your fiction?

The medical field is a nice cure for the stupidity of certainty—you see that there are so rarely “cures.” So much of medicine—most of it, really—doesn’t crossword-puzzle out into a clean-edged diagnosis. Medicine explains things up to a point, and then hits a wall. So much of it gives only a sensation of explanation, a fuzzy foundation from which to generate a treatment plan. It’s not like physics—that doesn’t hit a wall until you get very, very, very far. I think it’s something medical professionals understand better than the rest of us, the way that they’re constantly bumping up against both the uses and limits of their taxonomies and protocols. There are so few cases that have the clean shape of, say, snakebite from snake x, treat with antivenom y. Fiction often does its best work in those same wide spaces where data starts to lose its conclusive usefulness.

Alice Whitwham is the events coordinator at McNally Jackson Books.

Notes on a Successful Book Club

Detail from the first-edition hardcover jacket of Judith Rossner’s Looking for Mr. Goodbar.

Back when I worked in retail, a friend and I whiled away our breaks and slow days with what we called, unofficially, the Lurid Book Club. Admissions standards were straightforward: to be considered, a book had to be lurid. Accordingly, we read Flowers in the Attic, Seductive Poison: A Jonestown Survivor’s Story of Life and Death in the People’s Temple, Peyton Place, Savage Girls and Wild Boys: A History of Feral Children, and Escape, described by its publisher as “the dramatic first-person account of life inside an ultra-fundamentalist American religious sect, and one woman’s courageous flight to freedom with her eight children.” (We told a customer about the LBC and she contributed her copy of Anne Rice’s Claiming of Sleeping Beauty, which, besides being not at all what the book club was about, was tedious in the extreme.)

Unlike many book clubs, it was an unqualified success. It was impossible to not do the reading: we could not put these books down. But the social element was essential, too; the shared horror of the experience made it bearable. I can’t call it a guilty pleasure, because it wasn’t exactly pleasurable. I’m sure this plays into something dark in the human soul—or at least mine. But it was cathartic and educational. I highly recommend it.

If you should start your own Lurid Book Club, may I suggest the oeuvre of Judith Rossner? She’s best known for Looking for Mr. Goodbar, the 1975 novel (and subsequent film) that fictionalized the brutal murder of Roseann Quinn. This story—with its seedy singles-bar settings, its teacher-of-deaf-children-by-day, rough-sex-addict-by-night protagonist, and its violent denouement—is quite lurid enough. But that’s just for starters.

I ran across Rossner’s Any Minute I Can Split (about a woman who joins a commune) far too young, and after that I devoured August (about a troubled woman’s relationship with her equally troubled therapist) because my grandparents for some reason had both of them. On the subject of two of her other novels, I can do no better than Wikipedia:

In 1977, Rossner published Attachments, a story about a pair of friends who marry conjoined twins. Attachments was followed by Emmeline, the story of a fourteen-year-old farm girl who gets a factory job to support her impoverished family, is seduced and bears a child taken from her, whom unbeknownst to her she marries two decades later.

Essential, I would argue, to any comprehensive LBC syllabus. If your tastes run to the classics, I would also recommend Leave Her to Heaven, The Best of Everything, and, of course, the entire Jacqueline Susann catalogue.

I miss the Lurid Book Club—maybe it’s time to revive it. So many potential titles continue to beckon: In Bed with Gore Vidal; Jay’s Journal; Driving the Saudis: A Chauffeur’s Tale of the World’s Richest Princesses (plus their servants, nannies, and one royal hairdresser). Yes, there are better books in the world, books that I need and want to read. But to borrow from of Valley of the Dolls, “Never judge anyone by another’s opinions. We all have different sides that we show to different people.”

Lunch Poem Letters

Toward the end of college and for several years after, I kept two postcard photographs taped above my desk: one of Anaïs Nin, the other of Frank O’Hara—the mother and father of my literary interests at the time. Nin was a gateway for me into feminist writing and into thinking about creativity and the self. My love for O’Hara, on the other hand, was ecstatic. I was infatuated—and still am—with the conversational tone of his poetry, the ease with which he moves from Russian novels to bad movies, Robert Frost to Busby Berkeley, Bayreuth to Hackensack; his poems are like letters to a friend, and when I read them, I am that friend.

As collections go, none brings this quality to the fore more than the thirty-seven Lunch Poems, published in 1964 by City Lights. It is number nineteen in their Pocket Poets Series, an apt category for poems that O’Hara wrote during hour-long lunch breaks from the Museum of Modern Art in New York, where he was a curator. He roved through midtown, recording the “noisy splintered glare of a Manhattan noon” as well as his “misunderstandings of the eternal questions of life, co-existence and depth,” as O’Hara himself described the volume—“while never forgetting to eat Lunch his favorite meal.”

Lunch Poems turns fifty this year. Tonight, a host of writers will gather at St. Mark’s Church in New York to read it and celebrate the “indecision and cognac and bikinis.” (Yesterday, a commemorative plaque was unveiled outside O’Hara’s former residence at 441 East 9th Street.) City Lights’ new reissue of the slim volume includes a clutch of correspondence between O’Hara and Lawrence Ferlinghetti—we’ve reproduced five of these letters below—in which the two poets hash out the details of the book’s publication: which poems to consider, their order, the dedication, and even the title. “Do you still like the title Lunch Poems?” O’Hara asks Ferlinghetti. “I wonder if it doesn’t sound too much like an echo of Reality Sandwiches or Meat Science Essays.” “What the hell,” Ferlinghetti replies, “so we’ll have to change the name of City Lights to Lunch Counter Press.”

Letters copyright 2014 by City Lights Books. Reprinted by permission of City Lights Books from the forthcoming Lunch Poems: 50th Anniversary Edition by Frank O’Hara.

Hunting John Wilkes Booth’s Diary, and Other News

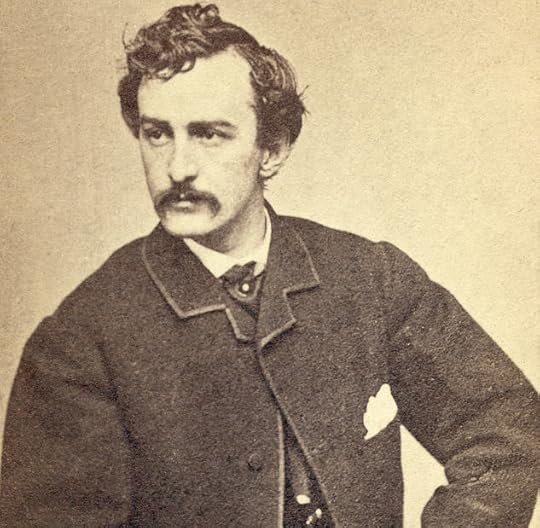

Booth ca. 1865. His diary may be in an abandoned tunnel in Brooklyn.

Knausgaard responds to his newfound celebrity …

… and the French shrug at that celebrity. “Knausgaard gives us one striking example of what looks again like a very French phenomenon … The list of French books in the same vein of meticulous self-analysis is nearly infinite … Let’s hope that Knausgaard’s unexpected success will make them rethink their hasty judgment and consider the French production with fresh eyes.”

Is John Wilkes Booth’s diary in a forgotten Brooklyn subway tunnel?

The complex, semitragic history of Entertainment Weekly and ent-fo, i.e., “entertainment information”: “The plan was highly digestible reviews intended to keep the bourgeoisie in touch … They wanted to assist ‘the aging baby boomer who still wants to be plugged in,’ using a scale (A to F) that reflected the ‘universal experience’ of school grades. If you read EW, the logic went, you were saving yourself from your own bad decisions: The magazine’s pitch for subscribers even asked potential readers to weigh the $50-dollar yearly rate against ‘the cost of a bad evening’s entertainment.’”

Commentators in the nineteenth century argued that chess, being so addictive, would turn our nation’s youths into bloodthirsty maniacs: “The great interest taken in this warlike game—the importance attached to a victory—and the disgrace attending defeat, are exemplified in numerous instances … It is said, that the Devil, in order to make poor Job lose his patience, had only to engage him at a game at Chess.”

June 10, 2014

Originals and Remnants

The poet Susan Howe is seventy-seven today. A few years ago, she and the musician David Grubbs collaborated on “Frolic Architecture,” a series of multidisciplinary performances that sprang from a book of her collage poems by the same name. Harvard has posted a video of the performance, which is quietly, insistently disruptive. As it progresses, prerecorded shards of Howe’s voice seem to fall into her live voice, and Grubbs fills the space with incidental sounds: insect chirps, gravel and snow and leaves variously underfoot. The performance seems at once to take on weight and ascend into the ether.

Howe remarked on the collage, and the process of recording it, in her 2012 Art of Poetry interview:

HOWE

I am an Americanist. There’s something that we do, a Romantic, utopian ideal of poetry as revelation at the same instant it’s a fall into fracture and trespass. Frolic Architecture cuts itself to bits. It could be that because I am a woman, bullets are more like blanks. What fuels the poems in that collection is the sense of epic breaking into shards.

INTERVIEWER

I’ve heard the recording of your performance of Frolic, and you actually speak—sound out—its fragments and phonemes, those shards. You treat your work as a score.

HOWE

Collaborating with the musician-composer David Grubbs has brought vividly home to me how acoustic a seemingly collaged and visual work can be. Several years ago our first collaboration was for a performance at the Fondation Cartier in Paris, and was based around an early poem of mine called “Thorow.” We collaborated again to produce Souls of the Labadie Tract. The work I have done with David has influenced the course of my later poetry by showing me a range of contemporary music with which I was unfamiliar. It also restored my earlier interest in Charles Ives. I love the way Ives’s musical use of quotation throws connectives to the winds. His work is Romantic and iconoclastic at once.

And in the journal Lana Turner, Ben Lerner wrote with typical acuity about the performance:

I assumed Grubbs had digitally manipulated Howe’s voice in order to mimic the fragmentation of the collages. And Grubbs did often and artfully alter her voice, but it turns out that many of the sounds I thought were digital slivers weren’t. It simply did not occur to me that Howe would be capable of reading such diverse phonemes and even smaller linguistic particles in real time with such precision. But she is: I have never heard a person pronounce “nt” or “rl,” for instance, so exactly. Howe can render even the most distressed text acoustic … Howe’s recorded voice—sometimes digitally cut up, sometimes left alone—alternated or overlapped with the live performance, and Grubbs had made sure that there was little or no perceptible sonic difference between what was digital and what was happening before us; when I shut my eyes, I couldn’t tell. This blurring of the boundary between the live and the recorded was a deft way to indicate how Howe’s poems are at once originals and remnants.

Sacred Rites

William-Adolphe Bouguereau, Crown of Flowers (detail), 1884.

The food takes awhile which gave us time to watch a waitress deliver a Dutch Baby and envelop us with its fragrant, perhaps sacred, steam. A tray of ruby grapefuit [sic] juice in large glasses made me think of luxurious jewels. Obviously we had traveled back to a past time. —A review of the Original Pancake House

When I was about twenty-six, a friend sent me a listing for a job at an online review site, which, at the time, had not yet gone public. It seemed to me a good idea to apply to lots of things, so I sent in a letter.

“We’re looking for someone hip and quirky for this job,” said the woman, Tyler, who interviewed me from San Francisco; she’d mentioned an improbably high salary and a host of benefits and perks. “You seem hip and quirky. But we need someone more integrated into the Web site’s community. I notice you have no reviews, no profile, and no ‘friends.’ We’ll need to see more of a commitment.”

I attacked my new assignment with determination. I set myself a quota of ten reviews a day and implored everyone I knew to join my network. In my capacity as manager of the lingerie store where I worked weekends, I commandeered the computer, knocking out reviews of the coffee at the bodega on the corner (“too subtle for the common palate”), the new artisanal pizzeria (“a horseman of the gentrification apocalypse”), and the local nail salon (“The nail technician was slovenly and surly; her coat was soiled; she started cutting my cuticles without asking”).

While I placed a premium on quantity, I began to take my task seriously: I was appalled by the cavalier manner in which fellow reviewers dismissed small businesses after a single visit or graded spots where they hadn’t bothered to wait for a table. I took special care in rebutting what I felt to be thoughtless and uninformed reviews. My tone became hectoring.

It was pathetically easy to become popular in this Web site’s universe. “You seem to really know what you’re talking about!” one stranger wrote me. “I like your strong opinions!” said another. In two weeks, I’d acquired more than a hundred “friends,” who complimented my every review with the pre-fab tags that indicated things were awesome, useful, or witty. I’d achieved the honorific of “Notable.” On the message boards, I was put on someone’s list of “Hottest Girls on the Site (NYC Area)”—presumably based on a blurry picture of myself posing with Mr. Met—and had been awarded two “Reviews of the Day,” for critiques of a cheese store and Pretty Nails.

After some time, having met, apparently, my uninformed-harangue quota, I was invited to attend a “Notables event” at a midtown bar called Sapphire, so the higher-ups could see how I dealt with the community. The “Notables”—a title bequeathed purely on the basis of review quantity—arrived in full force. The theme was “gangsters,” or maybe “roaring twenties”: several guys sported fedoras, three girls wore boas, and there was a plastic tommy-gun in evidence. One girl, for reasons I never ascertained, had on a Renaissance Faire–style corset. “That’s Julia S,” I was told, “the hottest girl on the site.”

The event was sponsored by a jalapeño-flavored vodka, so that’s what everybody drank. One girl started vomiting almost immediately. I found her a plastic bag. A joke video made by one of the staffers played in the background, but no one paid any attention, and you couldn’t really make out the words of the parody song, which seemed to be a take on Mariah Carey’s “Touch My Body.” There was light dancing.

“We’d like to fly you out to San Francisco,” said Tyler, the woman at the main office. “We hear you’re hip, and quirky, and handled the Notables really well at the Sapphire event.”

I went. The interviews took place in what might have been a set decorator’s idea of an Internet startup, decorated as it was with dogs, Foosball tables, and expensive coffee gadgetry. The founders of the company were young and confident; one of them lounged on an exercise ball. I tried to project hip quirkiness with every fiber of my being.

“We were really impressed with how you handled Angela,” said one of the founders. “She’s the Notable who threw up.”

The job didn’t pan out; looking back, I guess that was some kind of fork in the road. Maybe my life could have been different. Maybe, had I been hipper and quirkier, my life would have been more straightforward and successful. Certainly I would still have, at the very least, my status as a Notable. But is there any point thinking that way? Sacred steam or no, there is no way to travel back to a past time.

The National Writer

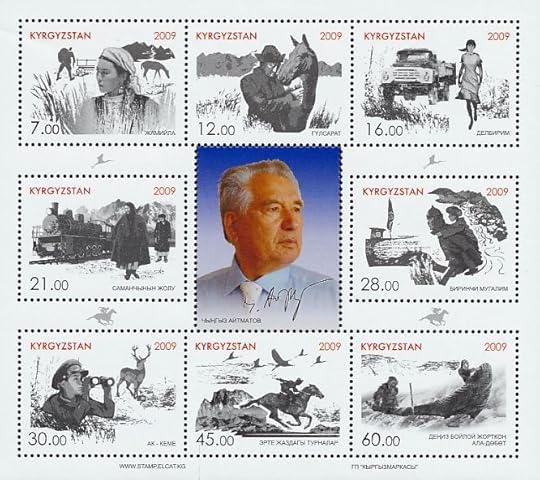

Chinghiz Aitmatov and the literature of Kyrgyzstan.

“Chyngyz Aitmatov and his arts,” a series of Kyrgyz postage stamps.

Six years ago today, when pneumonia claimed the life of the Kyrgyz writer Chinghiz Aitmatov, I learned about it the old-fashioned way: from a man weeping in the streets.

I don’t mean to imply that all of Kyrgyzstan had thrown its hands up in despair at the loss of its best writer and most famous native son, though I wouldn’t have blamed them if they had. I just happened to come across an old man—an ak cakal, or “white beard,” as the elderly there are known—sitting next to a small radio on a park bench, letting tears run down his face as he listened to the news. I’d been living in Kyrgyzstan for a year at that point, halfway through a tour in the Peace Corps; my Kyrgyz was not so sharp that I could clearly understand the radio, but it was more than good enough to ask the man if everything was all right. In response, he lifted a tattered copy of Aitmatov’s novel Jamila toward me and whispered, “He’s gone.”

It’s hard to overstate Aitmatov’s importance to Kyrgyzstan’s national identity. In my time there, new acquaintances regularly quizzed me on the country’s national this and national that. Kyrgyzstan’s national food? A fried rice dish called plov. The national music? Anything played on the ukulele-like komuz. The national writer? Chinghiz Aitmatov, obviously. (My younger English students had a hard time understanding why I couldn’t as quickly recite the United States’ national writer, et al.) December 12, the author’s birthday, is celebrated nationwide as Chinghiz Aitmatov Day. After Kyrgyzstan gained independence, Aitmatov represented the young country as an ambassador to the European Union, NATO, and elsewhere. “One of the great charms of Aitmatov’s life,” Scott Horton wrote for Harper’s shortly after the writer died, “was that he charted first the decline of the Central Asian life and identity, and then participated in its resurrection as the Soviet Union collapsed and as the Central Asian states regained, quite unexpectedly, their autonomy and footing on the world stage.”

Even in death, Aitmatov sits at the center of Kyrgyzstan’s complicated relationship with literature. One the one hand, books there are a genuine status symbol: many families prominently display elegant leather-bound encyclopedia sets and other attractive books in the rooms where they entertain guests. My host family, which lost many of its possessions in a fire before I met them, held on to their badly singed volumes even in cases where half of every page had burned away.

Even in death, Aitmatov sits at the center of Kyrgyzstan’s complicated relationship with literature. One the one hand, books there are a genuine status symbol: many families prominently display elegant leather-bound encyclopedia sets and other attractive books in the rooms where they entertain guests. My host family, which lost many of its possessions in a fire before I met them, held on to their badly singed volumes even in cases where half of every page had burned away.

But in other contexts, books are valued only for their most basic functions. On my first visit to Bishkek’s main bazaar, I ordered an empanada-like samsa, and it came wrapped in a grease-stained page torn from a collection of Alexander Pushkin’s poetry. When it came time to expel the byproduct of that samsa, I found half a history book leaning against the outhouse wall, offering itself up as toilet paper.

I never met him, but Chinghiz Aitmatov, born in 1928, often felt like a guide to me as I lived and worked in his country. I started reading his masterpiece, The Day Lasts More Than a Hundred Years, in my mother’s living room in Minnesota and finished it seven thousand miles away, in a village called Murzake. Improbably, the book juxtaposes a Kazakh community’s quest to bury a dead man in a remote desert cemetery with an astronaut’s and cosmonaut’s efforts to prepare their countries’ bickering leaders for first contact with an alien ambassador. Cloaked in the guise of science fiction, Aitmatov’s satire of Soviet leaders managed to slip past censors more easily than more explicit condemnations, like those of Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn. Moderate social criticism recurred frequently in Aitmatov’s work, as did complicated portraits of rural Central Asian communities, which Aitmatov produced without ever straying into “village prose,” a Soviet literary movement extolling the virtues of rural life and Russian nationalism that, for the USSR’s Turkic minorities, might loosely be compared to writing in the voice of Uncle Tom.

Aitmatov wrote The Day Lasts and much of his later work in Russian, seeking a larger audience, just as Vladimir Nabokov switched from Russian to English after fleeing the Bolsheviks. But the fact that Aitmatov wrote his early work in Kyrgyz challenged me to see the beauty in a language I often thought of as limited. Compared to English, the Kyrgyz vocabulary is quite small: present and future tense are one and the same; the subtle distinctions between words like similar and same are folded into a single word that hangs on its context.

Shortly before Aitmatov passed away, I tried to start learning Russian. My tutor was an old Russian woman, racist toward the Kyrgyz and nostalgic for the days when Kyrgyzstan was still a part of the mighty Soviet Union. So nostalgic, in fact, that my lessons hued closely to the Soviet style of teaching: on my first day she handed me a copy of War and Peace in the original Russian and instructed me to start reading out loud so she could correct my pronunciation. At the next lesson, I asked her if we could start with something a bit more basic. “I know just the thing!” she told me, digging through some boxes. She rose with a copy of Aitmatov’s The Day Lasts and explained that a novel by a “mere” Kyrgyz writer would be much easier for me to comprehend. I didn’t see a need for a third lesson.

Whether a person in Kyrgyzstan is mocking a writer’s work or cherishing it or throwing it into the toilet, she lives in a country fundamentally shaped by the tradition of storytelling. Before coming under the control of the Russian Empire and later the Soviet Union, the Kyrgyz were a historically nomadic group. The pre-Soviet Kyrgyz left few monuments or traditions with obvious applications in the more urban, post-Soviet country today. This is one of the reasons Aitmatov mattered so much: he embodied Kyrgyz culture at a time when it wasn’t clear what that meant.

But long before Aitmatov wrote his first words, the Kyrgyz had a robust oral storytelling tradition. The most famous of these stories is the Epic of Manas, the legendary founder of Kyrgyzstan, whose story takes days to recite. Like the Iliad and the Odyssey, Manas is a story of conquest—of Uighurs and Afghans, mainly—followed by a long journey home. As Aitmatov himself said of the oral tradition, while other peoples display their culture in tangible arts like architecture and written books, the Kyrgyz “expressed their worldview, pride and dignity, battles, and their hope for the future in [the] epic genre.”

But long before Aitmatov wrote his first words, the Kyrgyz had a robust oral storytelling tradition. The most famous of these stories is the Epic of Manas, the legendary founder of Kyrgyzstan, whose story takes days to recite. Like the Iliad and the Odyssey, Manas is a story of conquest—of Uighurs and Afghans, mainly—followed by a long journey home. As Aitmatov himself said of the oral tradition, while other peoples display their culture in tangible arts like architecture and written books, the Kyrgyz “expressed their worldview, pride and dignity, battles, and their hope for the future in [the] epic genre.”

Every name in Kyrgyzstan tells a story—a village called Mailuu Suu, or “Oily Water,” for example, helpfully reminds travelers that it sits on top of a nuclear-waste dump. And a shameful number of new parents give their daughters names like Boldu (“Enough”) and Burul (“Turn”), to indicate that they would have preferred a son. But less discussed is the name Kyrgyzstan itself, which means more than its primary definition, “the land of the Kyrgyz.” The word Kyrgyz is derived from the phrase körk küz, which means “forty girls”—a reference to the forty daughters of Manas, who became the mothers of the forty tribes of Kyrgyzstan. I can think of no other country whose name is derived from a work of fiction, unless you count the Bible. Even as Kyrgyzstan continues to face the struggles of a developing country, it’s worth remembering that the country came to be in part because its bards told its story again and again. It falls to the storytellers on Aitmatov’s shoulders to write the next chapter.

Ted Trautman has written for The New Yorker, The Atlantic, Slate, Wired, and others. He lives in Puebla, Mexico.

Signs and Wonders: In the Studio with Hayal Pozanti

My first encounter with artist Hayal Pozanti was the lucky happenstance of a predetermined seating arrangement: she was placed across the table from me at a dinner celebrating Jessica Silverman Gallery, which represents Pozanti on West Coast. We spent the evening in deep discussion on the finer points of photographic theory and discovered a shared interest in the writings of Freidrich Kittler. Agreeing to stay in touch, I found myself in New York for Frieze Art Fair and decided to pay a visit to Pozanti’s studio in Queens. She was born in Istanbul in 1983 and moved to New York in 2009. In a small partitioned space with views looking over the East River toward midtown Manhattan, we talked about her current body of work, which will be exhibited later this year at the Prospect New Orleans biennial and at the Parisian iteration of the Foire Internationale d’Art Contemporain.

With my recent paintings, I’ve been thinking a lot about Ken Price, Philip Guston, and Allan McCollum. And, of course, I always come back to Giorgio Morandi—I think about him regularly. I find that a common ground for all of these artists was the ability to create, through figurative abstraction, a world parallel to the one we live in. As a Turkish immigrant who has moved from place to place, who speaks several languages, I’m intrigued by the possibility of creating a universal language to unite my cross-cultural experiences. When I think back to my childhood in Istanbul—even during my time as a young professional there—I was always concerned with the question of acceptance and with the idea of unifying people.

My early paintings were very figural—I was looking at Turkish miniatures and thinking about the Abrahamic religions I was in contact with daily. While getting my M.F.A at Yale and studying with Peter Halley, my practice was based on images that I would collect from the Internet. I was really engrossed in that culture of image collecting, collaging. But I realized that I couldn’t propose something new by appropriating things. I wanted to step away from the computer, because I was spending so much time in front of the screen, sitting there staring at something with dozens of tabs open.  I decided to invent my own language, through abstraction. I was deeply intrigued by hieroglyphic and pictographic-based civilizations, and often I would take the train down from New Haven to visit the Met’s collection of Mesoamerican artifacts. I also have a background in graphic design—prior to making art full time, I worked in a corporate environment developing visual branding—so I have a familiarity with making signs and symbols.

I decided to invent my own language, through abstraction. I was deeply intrigued by hieroglyphic and pictographic-based civilizations, and often I would take the train down from New Haven to visit the Met’s collection of Mesoamerican artifacts. I also have a background in graphic design—prior to making art full time, I worked in a corporate environment developing visual branding—so I have a familiarity with making signs and symbols.

My initial approach to shape making were variations on “a circle in a square.” After generating hundreds of sketches, I noticed similarities in form and order. This led me to narrow it down to thirty-one signs—an alphabet, if you will. After that, I began combining those initial signs to produce additional ones, much like creating words and sentences from letters.

I free-sketch most of the time. Then I put the sketch-painting in the computer and keep painting on the computer. I have a track pad, so I’m still using my hands.  When I’ve adjusted the image to my liking, I print off a preliminary copy as my guide and begin the composition anew, painting with acrylics or oils on wood board. Sometimes, I’ll pause to take a photograph of the composition, import it into Photoshop, and see how it looks on-screen. Until a painting is completed, I think about how the composition looks on the wall, through the camera’s viewfinder, and on-screen. Recently, I’ve also starting making three-dimensional sculptures and short animation videos, both informed by my sketches and paintings.

When I’ve adjusted the image to my liking, I print off a preliminary copy as my guide and begin the composition anew, painting with acrylics or oils on wood board. Sometimes, I’ll pause to take a photograph of the composition, import it into Photoshop, and see how it looks on-screen. Until a painting is completed, I think about how the composition looks on the wall, through the camera’s viewfinder, and on-screen. Recently, I’ve also starting making three-dimensional sculptures and short animation videos, both informed by my sketches and paintings.

As for my routine, I’m usually very disciplined. I live in Chinatown with lots of families in very close quarters, so I wake up to children running down the stairs. In the morning, I put on the BBC world report, do Pilates, and then catch the L train to my studio. I put in regular hours. I tried being the bohemian artist for a while, but then you’re not in sync with the world, and phone calls need to be made.

Joseph Akel is a writer based in New York City and San Francisco. A regular contributor to Artforum, Frieze, and ArtReview, among others, he is a Ph.D. candidate in the University of California, Berkeley's Rhetoric Department.

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers