The Paris Review's Blog, page 692

June 19, 2014

Razed in Cincinnati

Photo: Cincinnati Public Library, via Flickr

A few days back, MessyNessyChic—let’s not dwell on the name—posted a series of photographs of Cincinnati’s old public library, erected in 1874 and demolished in 1955. Even if you’re disinclined to fetishize the past, it’s hard not to greet these images with awe and a certain degree of wistfulness. This was one hell of a library, with a checkerboard marble floor, soaring shelves, cast-iron alcoves, and several stories of spiral staircases. In the grandeur of its design, it’s something on the order of McKim, Mead, and White’s original Penn Station—a work of architecture so self-evidently valuable to the contemporary eye that its demolition can be met only with bewilderment and righteous despair: What clown authorized the wrecking ball here?

But aesthetics were not then, and aren’t now, a high municipal priority—as evidenced by the criticism of the time. Harper’s Weekly once wrote about the library, “The first impression made upon the mind on entering this hall is the immense capacity for storing books in its five tiers of alcoves, and then the eye is attracted and gratified by its graceful and carefully studied architecture …”

It seems backward, and dismayingly utilitarian, to note the “immense capacity” first and the “graceful” design second—by that logic, the world’s warehouses and hangars rate among our architectural marvels. But maybe they do; we won’t know for sure until we start tearing them down.

The Cincinnati Library’s Flickr collection hosts even more photographs of the building—they’re much easier to digest if you pretend it’s still standing. Here are two more:

Over There

R. Ferro, Cupidity - Greed

Lately I’ve been listening to the excellent BBC documentary World War I, which you can download and then listen to, incongruously, while waiting on line at the grocery store. The series presents the listener with a multifaceted portrait of the Great War, but—for obvious reasons, given the topic—it’s not exactly a laugh a minute.

That’s part of what makes the British Library’s new exhibition, “Enduring War: Grit, Grief, and Humour,” so surprising. Of course, people have always laughed and joked and made the best of awful situations—resilience is a marvelous thing. But the lighter side of World War I hasn’t come in for much scrutiny.

The exhibition is multifaceted: there are propaganda posters, excerpts from Rupert Brooke’s war journals, harrowing accounts of gassings and shell-shock, and horrifying casualty numbers. But along with this, the curators have made a point of highlighting soldiers’ darkly humorous letters and joke postcards; photos of servicemen goofing off; and satirical excerpts from the morale-boosting publication Honk! The voice of the benzine lancers.

If you’re wondering whether I’m reporting this live from the British Library’s Folio Room, let me just say: I wish. But the library’s World War I archive page is absolutely fantastic. I spent literal hours learning about army chaplains, war dogs, civilian diets, trenchfoot remedies. The range of materials is enormous: you can see both the original manuscript of “Dulce et Decorum Est” and read about “the presence and variety of swearing within World War One ranks and how its use bonded or divided soldiers.” To wit,

If swearing was part of the brutalizing process of the war, it was also capable of wit and invention. A devious and clever indication of word and accent comes in W H Downing’s 1919 Australian war glossary, Digger Dialects, in a couple of definitions: Carksucker—American soldier; Fooker—English private. This enjoyment of the potential for wit in swearing is also seen in the description of the anti-gas Phenate-Hexamine or PH Helmet by Captains Robert Graves and J C Dunn of the Royal Welch Fusiliers, who famously described it as the “goggle-eyed (or googly-eyed) bugger with the tit.”

‘If a whiff of gas you smell,

Bang your gong like bloody hell,

On with your googly, up with your gun—

Ready to meet the bloody Hun’

If you’re in London, you can see the posters, ephemera, and artifacts for yourself: the show opens today.

Laid Bare

The fall of Spain; how Croatia got its groove back; four degrees of surprise from Australia.

Croatia’s team relaxed in the buff, causing a scandal at home.

The same day that, in Chile, more than twenty previously unknown works by Pablo Neruda were discovered in the most unlikely of places—a drawer—Spain thought it was a good idea to continue their monarchy by changing the constitution so the prince could replace the abdicating king. I rejoiced at one and shrugged at the other. Fittingly, Chile beat Spain 2-0 yesterday.

Chile showed the extent to which Spain is past its sell-by date. Spain has become a product, a collection of starry names to sell to a depressed populace. The sales pitch used to work: they won the Euros in 2008, the World Cup in 2010, and the Euros again in 2012, an unprecedented streak. But what worked then never evolved into what will work now. Most of the players from 2008 were in Brazil in 2014: the goalkeeper Iker Casillas was benched by his club team for the majority of the past two seasons, yet started in this World Cup. His place was barely questioned. Of course he wanted to play: Spain has more than 50 percent unemployment for adults twenty-five and under; the players stood to win a bonus of 720,000 euros each if they won this World Cup. But yesterday their gaps on the field expanded like an opening wound. The players—and soon after them the ball itself—rolled around more and more slowly. They seemed to be playing uphill.

But there will be more than enough elegies and eulogies for Spain. Let me instead sing the praises of Chile, a team that’s been on the upswing for some time now. Their next and final match in the group stage will be against the Netherlands, with the two thus far undefeated teams vying for the top spot in the group. Coincidentally, both teams played Spain in the last World Cup, with Chile losing what was, like yesterday’s game, a must-win scenario, 2-0. Both Chile and the Netherlands have already qualified for the knockout rounds, so Monday’s game should be a formality—but one of them will likely end up playing Brazil in the next round. But given the way Brazil has been playing, let’s not get ahead of ourselves.

Then again, Brazil’s next opponent is Cameroon, and I’m less certain that the planet is round than I am that Brazil will beat Cameroon. Last night, the ghastly Cameroon team lost 0-4 to Croatia, who seems to have risen from the ashes of their opening game against Brazil last week. Let’s hear it for team bonding: after the loss to Brazil, the Croatian players took to swimming and chilling poolside, in the nude. It worked.

What else? Holland beat Australia. (You’re not surprised.) Australia was, at one point, in the lead. (You’re a little surprised.) Australia had possession of the ball nearly as often as Holland. (You’re surprised.) Australia’s Tim Cahill (who plays in New York!) scored a goal against Holland as good as Holland’s Robin van Persie’s goal against Spain. (Your head hurts.)

But that’s how this tournament goes. At any moment you may see something that will stick with you for the rest of your life. The rapid, mazy triangulations of Brazil’s 1982 team; Maradona’s slalom against wobbling phalanxes of English defenders; Roger Milla defying age and elevating Cameroon to dizzying heights with his goals, then teaching the world how to celebrate with style, shimmying with the corner flag.

Joy. This tournament keeps giving it, though it’s sometimes buried. Yesterday, in Rio’s historical Maracanã stadium, the camera would often capture the dejected faces of uniformed Spanish fans as the inevitability of loss and the end of an era settled on them. In the highest part of the stadium, a gigantic screen often shows video of the crowd. Whenever someone would notice he was onscreen—and it always took a few seconds or a nudge from someone—everything about him would change. He would rise to his feet and wave to everyone. His mouth would move with the passion of a song. Hello, hello, go go go.

Rowan Ricardo Phillips’s second book of poems, Heaven, will be published next year. He is the recipient of the 2013 PEN/Joyce Osterweil Award and a 2013 Whiting Writers’ Award.

Project Angel Raid

Sleep-away camp revisited.

From the cover of Alexandra G. Lockwine’s Camping by Biddy, 1911.

Five miserable summers straight, I made the trek to Camp Saginaw, a.k.a. Camp Saggyballs. The cornpone setting in Oxford, Pennsylvania, was the backdrop for my induction into the myth and ritual of the camp, whose songs and traditions served mostly to perpetuate the philosophy that this was the best place on Earth. It was not—what with the mediocre campfires, the soggy waffles, the deflating banana boat on the murky lake.

Still, I attended until I had earned the only slightly coveted green Old-Timer shirt, affixed with an Indian chief insignia; until I’d scraped my knuckles raw enough times at the gaga court to develop permanent scars; and until I no longer became teary-eyed when “Total Eclipse of the Heart” played at the roller rink while the girl I crushed on slow-skated by with another boy.

Most important, I attended until, at long last, I successfully snuck to Girls’ Camp at midnight.

How many nights over multiple summers my bunkmates and I had stayed up plotting Project Angel Raid! We dressed in all black or navy blue, talking with our flashlights pointed up to the rafters, only to fall asleep in our sweatpants and hoodies. Come morning we hit our mattresses with a heavy fist—yet another failed mission …

But there was an added incentive the summer I turned twelve: I met Jill, she of the freckled cheeks and strawberry blonde hair. So what if she wore corrective glasses because she was slightly cross-eyed? She had taken a shine to me, and it was important for me to demonstrate my devotion with the type of bravado brandished only during a caper.

My affection, to be sure, was pure. After all, she was different from the usual campers—ages six to sixteen—who were generally from mid-Atlantic Jewish families in the Potomac area and northern Jersey. Those kids romped through the acres of zip lines and climbing walls, go-cart tracks, playing fields, tennis courts, canoe creeks, mess halls (with pitchers of bug juice), swimming pools, archery and gun ranges. Jill wasn’t one of the JAP-y girls who clumped on eyeliner and tube tops for evening canteen. She was a down-to-earth type, a unique beauty—if suddenly she were to pass by, you would lengthen your stride on the soccer pitch or muster enough strength to hit a fade-away jumper on the basketball court.

Our operation became imperative after the annual field trip to the roller rink. We traveled on dizzying yellow school buses past Mine-as-Well, Pennsylvania, and neighboring aw-shucks hamlets with hog farms that inspired accusations of flatulence:

Skunk in the barnyard

P.U.

Whoever farted

That’s you.

I sat next to Jill, whose hair smelled like delicious Herbal Essences shampoo, and the sweat on my hamstrings made my legs stick to the pleather seats. Such a brazen move as sitting together made teasing—in the form of another humiliating ditty—inevitable.

Hey, lolly-lolly-lolly. Hey-lolly-lolly-lo

Hey, lolly-lolly-lolly. Hey-lolly-lolly-lo

I know a guy, his name is Ross …

Hey-lolly-lolly-lo

Jill’s salad he likes to toss …

Hey-lolly-lolly-lo

The roller rink smelled like microwaved pizza and was a galactic-neon relic of the eighties. At this very rink, in a past summer, I had caught wind that a girl named Kim “liked” me. I had pursued her but had made the mistake of leading with the following line: “Hey, Ryan says you ‘like’ me …”

This year, though, Jill and I were able to skate awkwardly along the slippery waxed wood, the strobe lights aglow, the disco ball for a moment covering her crossed eyes. We made a pact that my crew would visit hers that night. She and her friends might sleep in blush. We guys would change into all black when we got back to the bunk and do our best to stay awake.

* * *

My crew had been conducting daily recon on far-flung edges of the property with the covert goal of completing an angel raid. But the obstacles preventing a successful mission were numerous.

First, the counselors, who at Camp Saginaw were mainly British and Australian. To this day, when I meet an Aussie, I become docile at what I perceive to be authoritarian cadences. These characters used their accents to enforce the rules. You might get a jolly congratulations for this or that romantic conquest, but no Sydneysider wanted trouble for letting you loose on his watch.

The geographic orientation of the camp, too, posed its difficulties. The cabins of campers twelve and under were divided by age group—Juniors and Inters—into clusters, with Boys’ Camp set on a slope and the equivalent Girls’ Camp cabins set at a higher grade uphill on the opposite side of the mess hall, a model-rocket launch away.

Though our Inter bunk was laughably distant from Jill’s, we had one strategic advantage: a short left out of our door lay a staircase to Lower Field, out of reach from the counselors’ “torches,” which beamed across lawns, and the patrolling golf carts and John Deere Gators, always on the lookout for camouflaged delinquents.

And many were the watch squads.

After all, there was no shortage of rabblerousing at Saginaw. Mornings, for example, you’d wake at seven to the blast of reveille from the loudspeakers and the voice of “Birdie”—real name Roberta Frankel, a red-haired old lady with a predilection for Tweetie Bird shirts, a habit of playing Barry Manilow’s “Copacabana” over the loud-speaker, and a nonchalance that said, I’d rather be in Boca—and exit your cabin only to find BOLLOCKS written in shaving cream by the tetherball pole. But to me this was child’s play—I was almost of bar mitzvah age, mind you, and ready to engage in grown-up behavior. Namely, making it to Girls’ Camp at night.

After lights out, the counselors on duty would sit in the pagoda drinking Coors and talking about getting some, their words peppered with the vernacular of the British Isles.

Once their chatter died down, my friends and I tip-toed toward the exit. Among us were Eric and Ira, whose fathers ran neighboring dental practices in Maryland, and David, whose perpetual hang-dog demeanor earned him the moniker “Droopy D” or “Droop Dog.” If you didn’t remove the spring on the screen door, it would emit a cartoonish whine, so I unhooked it and held the now ghost-silent door for my comrades. We dashed down the staircase into a heavy darkness through Lower Field—the suede of our Vans and Airwalks soaked in the dew.

We trudged up past the pool where, during the day, the swimming instructor Mort Fish held court and knocked on his head, claiming it was made of wood.

We had to traverse a brightly lit road by the canteen. We crossed one at a time in flash sprints and entered Girls’ Camp—I smelled pine needles, and pinecones crunched beneath our feet. When we arrived at Jill’s bunk, we rapped gently on the door and some functionary sideline friend answered with a promise to retrieve Jill.

Soon, out came my sleepy four-eyed damsel and two of her friends. We sat cross-legged there on the deck—too awkward to make any moves and too drowsy to express too much emotion: we were all like the diffident Droop Dog. The girl in the shadowy corner suggested a game of truth or dare. This, I later realized, was just a ploy to initiate some tonsil hockey. I was ready, I thought. My auburn bowl cut at the time was so damn cute, I deserved half a dozen strabismic concubines.

Jill went first and chose dare. I, debonair boy that I was, challenged her with knocking on the door of the adjacent bunk and then running back to us.

“I mean, I’ll do it,” she said. “But …”

The elliptical pause meant both “this is just kind of stupid” and “why didn’t you dare me to kiss someone?”

We were in the process of letting her off the hook—suggesting it was a dangerous endeavor—when all of a sudden we heard a squeak, a definitive, high-pitched one. We ignored it aggressively, and in so doing called attention to it. Just then, a female British counselor wearing a bandana came out of the bunk and told us to hush up and pack it in for the night. That was enough to deflate the party. We four guys bid brief, mumbled farewells of zero poetic substance or consequence and descended the steps.

On the way back we debated whether the high-pitched squeak was a soprano fart or that new term we had learned—a queef. I suppose we should’ve felt defeated; my first kiss was still two summers away. But the feeling was of victory. We’d stayed awake. We’d successfully executed a mission to Girls’ Camp. We passed the pool, ran up the steps, pulled back the screen door, reattached the spring, and drifted off into a heavy navy-blue sleep.

Ross Kenneth Urken is a writer in Manhattan. Read more of his work here.

This Machine Will Self-Destruct, and Other News

Kaboom!

New additions to the list of things the pen is mightier than: the mouth, the camera. “As soon as kids acquire a basic understanding of letters and reading … they exhibit a greater trust in printed textual information than in oral or visual information … something about the act of learning to read causes children to ‘rapidly come to regard the written word as a particularly authoritative source of information about how to act in the world.’” And it is. Trust me.

Clancy Martin and Amie Barrodale on the Chateau Marmont: “To the left is a room with a lot of nice old mismatched couches and armchairs. Not blocking the chairs, so you might not notice it, just against the far wall, is a podium. An attractive person is always standing there, and if you try to sit in the lobby, he or she says, ‘Are you staying here?’ If you are, then you can sit.”

On DIS magazine and accelerationism: “‘Do they really just worship consumerism?’ … As curator Agatha Wara, a DIS associate, once explained it to me, accelerationists believe that ‘the only way to get over capital is through capital’—that is, by accelerating capitalism’s own tendency toward self-destruction.”

Speaking of that very tendency, Amazon is making a smartphone.

Did you know? It’s not easy to translate Proust: “There is always a tension in translation between the spirit and the letter, between conveying things we might call tone, mood, feel, or music, and being as literally faithful to the original as possible. Moncrieff excelled at both.”

How an episode of Star Trek: The Next Generation describes the outermost limits of our capacity to communicate: “Tamarian verbalisms depict the world through images and figures, which distort their ‘real’ referents. Troi and Picard can’t help but interpret Tamarian through their (and our) cultural obsession with mimicry: Metaphorical language operates not by signification, but as poetry, by transforming the real in a symbolic mirror. But for the Tamarians, something far weirder is going on …”

June 18, 2014

Virgins in Cellophane

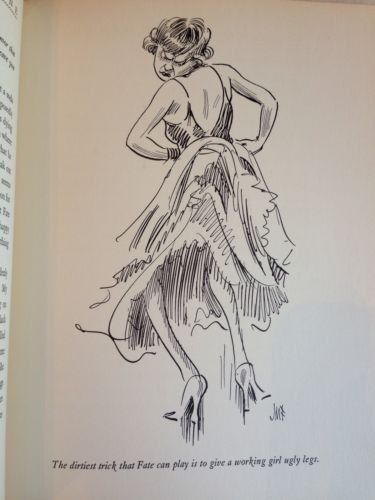

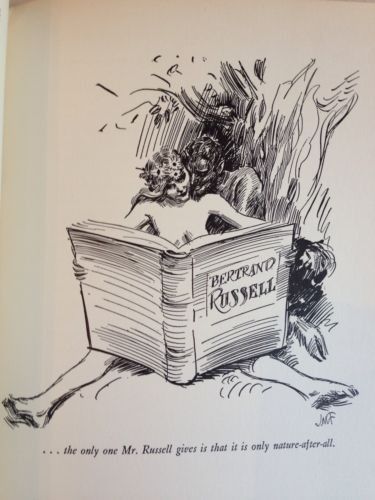

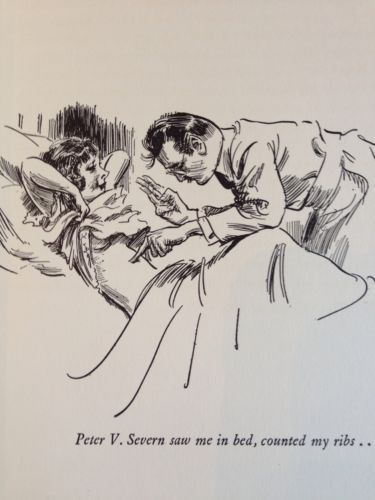

James Montgomery Flagg was one of the most famous illustrators of the early twentieth century. His most ubiquitous creation is that iconic World War I–era poster of Uncle Sam—the one where he points straight through the fourth wall and proclaims, “I WANT YOU FOR U.S. ARMY”—which is, depending on whom you ask, a stirring call to arms or a brazen, manipulative act of jingoism that did violence to the national psyche.

Flagg, born today in 1877, was a master draftsman with heavy, distinctive penmanship. He was versatile and prolific, and he came to prominence at a time when improvements in printing technology made it easier than ever to reproduce complex drawings—accordingly, he enjoyed a degree of celebrity unknown to his profession before or since, hobnobbing in Hollywood, vacationing in Europe, throwing caution to the winds of many nations. At the height of his powers, he was reputedly the best-paid illustrator in America.

Flagg loved to draw women, preferably voluptuous women, and he was no stranger to the bawdy and the blue. But none of this explains what compelled him to illustrate Virgins in Cellophane, a collaboration with Bett Hooper, published in 1932—one of the creepiest paeans to chastity (wink, wink) this side of purity balls.

Virgins’s subtitle is “From Maker to Consumer Untouched by Human Hand”: that consumer is lecherous enough to launch a thousand nightmares. The drawing on its cover features three ample, pink-nipped nudes bursting forth from some guy’s vest pocket—said nudes are duly wrapped in cellophane, their condition undoubtedly pristine, their maidenheads presumably intact, and the guy’s fleshy, prurient fingers are in the process of plucking one of them out like a cheap cigar.

I’m sure you have questions; I wish I had answers. The Internet is scarce on metadata. I was unable to find any sort of descriptive copy about the book, its assuredly titillating plot, or its less-famous coauthor, Hooper. I did find a few stray drawings from Flagg, all of them characterized by a chummy, inert misogyny of the Coffee, Tea or Me? variety. I’ve included them below; your mind will have to do the rest. You may not be surprised to learn that, if these drawings are any indication, the virgins aren’t as chaste as advertised; one wonders how they got out of the cellophane for all that hanky-panky, but we may never know. All of this is underscored by a terrifying irony: this is the same illustrator who implored record numbers of young men to enlist.

The Whys and Wherefores

Jeanette MacDonald in an Argentinean Magazine, February 1934

I remember the moment clearly: it was a late winter afternoon, and I was sitting on the radiator in my bedroom, reading Michelle Phillips’s memoir California Dreamin instead of doing my ninth-grade English homework. The author described moving into the mansion where the 1930s movie star Jeanette MacDonald had once lived. The Mamas and the Papas—then at the height of their fame—gutted the place, in the process ripping out the built-in wardrobes, whose enormous drawers had been designed to hold entire gowns, laid flat. And I made the conscious decision not to tell my grandmother about it. I thought it would distress her.

Back when the world was simpler and videotapes were physical objects, my grandmother and I used to set aside an afternoon when we’d settle ourselves on the couch with the milkshakes she made from homemade ice cream and gorge on Jeanette MacDonald–Nelson Eddy films. Why my grandparents had them all on cassette I don’t know; maybe my grandpa had picked up the lot at a tag sale. Those operettas became the soundtrack to my summers; to this day, I can’t hear the “Indian Love Call” without a Proustian rush of nostalgia. Of course, since one never hears the “Indian Love Call,” said rush has yet to happen.

There was a time when everyone knew MacDonald and Eddy. Films like Rose-Marie and Maytime made the handsome singers household names, and made hits of their scores. The films were corny and soapy, and even eighty years ago the music was nostalgic. Eddy’s acting—especially in their early collaborations—was wooden. (Check out the clinch in Naughty Marietta for proof.) But my grandmother loved them when she was a little girl, and at the same age, I adored them. A few plot synopses will illustrate why.

Rose-Marie (1936) :

Opera singer (Marie de Flor) seeks out fugitive brother in the Canadian wilderness. During her trek, she meets a Canadian mountie (Sgt. Bruce) who is also searching for her brother. Romance ensues, resulting in several love duets between the two.

Sweethearts (1938) :

A musical comedy duo in their sixth year on Broadway receive an offer to perform in Hollywood making films. The change of lifestyle is inviting to the Sweethearts as the move will take them away from relatives and friends who want to engage them in countless performances. However, when it comes to signing their Hollywood contract they do not sign as Gwen has been deceived into believing her sweetheart and husband is engaged in an affair with their personal assistant. The Sweethearts split up and carry on performing their musical production around America with their understudies as their co-stars. Eventually they are united in a Broadway Show.

Naughty Marietta (1935):

In order to avoid a prearranged marriage, a rebellious French princess sheds her identity and escapes to colonial New Orleans, where she finds an unlikely true love.

Naughty Marietta is by far the best, I think, and Maytime the worst. To me, these films exemplified all things idyllic and wholesome. But childhood dreams are made to be shattered! Only a few years ago, I ran across a book at a library sale the ripped the scales from my eyes. I refer to Sweethearts: The Timeless Love Affair Onscreen and Off Between Jeanette MacDonald and Nelson Eddy, by Sharon Rich. From the flap copy:

Sweethearts is the true story of one of Hollywood’s greatest cover-ups: the love affair between Jeanette MacDonald and Nelson Eddy. Known as “America’s Singing Sweethearts” of the 1930s and forties, they made eight box office hits together for Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer and became the most popular singing team in movie history. Rumor had it that they hated each other off-screen but the truth was that they were in love. Interference by MGM studio boss Louis B. Mayer triggered a series of tragic events that caused them to self-destruct their film careers, health and ultimately their lives. Discussed candidly in the book are Jeanette’s four pregnancies by Nelson, her affair with studio boss Louis B. Mayer and her marriage to bisexual Gene Raymond. Nelson married a mentally unstable woman, Ann Franklin, who blackmailed him into marriage, threatened to disfigure Jeanette, and vowed to go to the press with the scandal if Nelson tried to divorce her. Despite all, Nelson and Jeanette had a fierce, spiritual bond and loved each other to the end. The author was a close friend of Jeanette’s older sister, actress Blossom Rock, interviewed over 200 people, including celebrities, plus had access to a wealth of unpublished letters and memoirs.

Obviously, I devoured it. Not only that, I spent a good long while on the author’s excellent and comprehensive website. (“Forget the bare-bones dates and facts and the sanitized versions that can be found elsewhere. If you’re visiting this website you no doubt want to know more—the whys and wherefores of the lives of Jeanette MacDonald and Nelson Eddy.” Did I ever!) But even as I adjusted to this new world, I reassured myself that my grandmother had never run across the book. She, at least, retained her innocence.

Or did she? For all I know, she was wise to the truth the whole time. Maybe she found the lurid stories fascinating. Maybe she didn’t believe them. Maybe she didn’t care. Maybe she just enjoyed the ritual of sharing a piece of her childhood with a granddaughter. She, after all, was not a child.

That said, I’m glad I never told her about those closets. I really think it would have made her sad. At least, I’d have been sad to tell her.

Happy birthday, Jeanette.

Red Giant: An Interview with Shane Jones

I met Shane Jones in 2009, in Chicago, during the annual AWP conference. Amid the crowded fluorescent labyrinth, I happened upon him manning the Publishing Genius Press table, projecting an aura of calm that seemed delightfully out of step with the usual huckster energy of the book fair. I bought his novel Light Boxes and read it on the plane home, where I was so transported by the world Shane had created that I forgot all about the smells and turbulence of travel by air. I remember tucking the book into my bag and thinking, Whatever this person does next, I’ll read it. Shane and I have stayed in touch ever since.

Crystal Eaters is full of the fabulist inventions that often mark Shane’s fiction—a ravenous sun and “crystal counts,” the idea that we’re born with a hundred crystals inside us, a supply that dwindles until, at the end of our lives, it’s exhausted—but at the core of the novel is a family’s struggle to turn toward one another in the face of unbearable loss. Shane conjures a world that is, in ways large and small, melting down.

Shane and I spoke via e-mail—I was in Andover, Massachusetts, and Shane in Albany, New York—about the new book, fatherhood, death, and therapy.

There are many layers of mythology in Crystal Eaters—surrounding, to name a few, the black crystals, people in the city versus people in the village, the beliefs of Brothers Feast and the Sky Father Gang. “Everyone is eventually fooled into believing in something that doesn’t exist,” you write.

Religion, spirituality, cults—Brothers Feast and the Sky Father Gang are cults—prayer, crystals, myths, folktales, the universe as a system of life and destruction—I’m attracted to these things, and they are players in the book. The idea of choosing something—a value system—and believing in it is very beautiful, even if it’s absurd in the face of death. I’m always surprised when writers say they don’t believe in a god or religion but they believe in creating a world on two hundred pages using symbols. We’re all worshiping something. The city worships things like hospitals and fast food and phones and constant consumption, and I’d say those things are a dangerous kind of worship. I’m more interested in the dirt dwellers, who believe, here, that they have a number of crystals inside their stomachs. I very desperately want to believe in something, and I think writing is a way to dig at this wall. There doesn’t have to be an answer, really. Just the movement.

As far as being fooled into believing in something that doesn’t exist—as a kid, you’re constantly being sold one fantasy or another. Santa Claus, Sesame Street, the police are the good guys, parents know what they’re doing, doctors will help you with medicine, men protect women, et cetera. These concepts slowly dissolve, or are at least kind of remolded, as you get older.

In your essay “Pram in the Hall,” you talk about how fatherhood, the surreal exhaustion of it, pushed you into this headspace that sounds amazing creatively. You talk about looking at the spot where the ceiling and the wall meet and seeing “the seam crack open, revealing a horizon of white light and red lava.” That image seems like one that could exist within the world of Crystal Eaters.

The foundation of Crystal Eaters is a family drama and coming-of-age story, but it’s all taken apart by the logic of the crystal worship and the chaos of the universe. And it does connect to fatherhood and my early experiences with being a father. The book would have been more fantasy and less about family dynamics and death if it wasn’t for the fact that I was working on it while my wife was pregnant. And after Julian was born, I was still writing and editing, sleeping in naps, thinking things like, How do I take care of a human being? Seeing my son born, seeing him grow, pushed me to work harder than ever before. It’s a very personal book.

Mom and Dad are okay parents in some ways, but they’ve lost touch with one child, who is in jail—and with their daughter Remy, their interactions are filled with small failures of communication and compassion. There’s a moment when Remy thinks her crystal count has been lowered from “damaging parents’ words entering my brain.”

There’s an old interview with Martin Amis where he talks about his parents passing and he says that when his father died, he felt a great surge of energy, a real willingness to work and live. But when his mother died, he felt like the air got sucked out of him. Her death left this great big hole and he didn’t want to do anything. When Crystal Eaters is about to close, the family draws in and connects, physically, to Mom. She’s reached zero crystals—she becomes this void that the others can fall into, and her daughter, Remy, is the one who will fill it. We know Mom’s going to die. How do you approach the inevitable? The figure of the mother is the ultimate life force, and to see any mother die is brutal.

There’s an old interview with Martin Amis where he talks about his parents passing and he says that when his father died, he felt a great surge of energy, a real willingness to work and live. But when his mother died, he felt like the air got sucked out of him. Her death left this great big hole and he didn’t want to do anything. When Crystal Eaters is about to close, the family draws in and connects, physically, to Mom. She’s reached zero crystals—she becomes this void that the others can fall into, and her daughter, Remy, is the one who will fill it. We know Mom’s going to die. How do you approach the inevitable? The figure of the mother is the ultimate life force, and to see any mother die is brutal.

That question—how do you approach the inevitable?—seems so central to Crystal Eaters, not only in this context of Mom but with the idea of a crystal count in general—the possibility of knowing how much time you have left. Were the crystals always part of the book?

I work a day job, and part of it involves political campaign work. I was in Rochester in 2010 in some massive campaign office and I started writing down a list of ideas. “Crystal count” was the first thing I wrote in this list of about a hundred things. We’re all haunted by the fact we are going to expire, and what we do against it, or don’t do, defines us. And even in that defining, we know, deep down, that it may be meaningless. It’s like that Thomas Bernhard quote—“Everything is ridiculous in the face of death.” The crystals were always part of the book, but other stuff did change. The original draft had an entire storyline taking place in the city. You got to see everything. That was a bad idea—it made the city seem less menacing, and the way the book is now, you just get glimpses of it until the end, when it really explodes on you.

At the end of Crystal Eaters, both the family and the world at large are collapsing in radical ways, but there’s still a lot of beauty to be found—imagistically, the togetherness of the family at the end. And I don’t mean beauty in the slight, decorative sense, but more like I never lost that feeling of human possibility. What did you want to leave the reader with?

It’s a complicated ending because you have all these connections happening. The family, for the first time, gathers and physically connects around the dying mother. The sun comes in to connect to the earth and the black crystals. But these connections come with an ending. Personally, the idea that the earth is going to be erased by the sun is thrilling. I wish I’d be around to see it. There will be another beginning. Toward the end of the book, Remy tells a doctor that Mom is a red giant because of her red color, from her illness—this is something I learned while watching a relative die, how the skin on the legs sometimes turns into this red shell. But the term also means the future sun. A red giant is always expanding and growing—so Mom doesn’t really die, she lives in the form of the sun. I wanted to leave the reader feeling completely obliterated, carved out, but also inside that carving out a feeling of possibility.

Painkillers, God, and America

Let us pray. Photo: Jason Wojciechowski, via Flickr

According to the American Society of Interventional Pain Physicians, Americans consume 80 percent of the world’s painkillers—more than 110 tons of addictive opiates every year. It must be a very painful place to live.

How much of that pain has been caused by soccer? Not much, at least not to begin with: an unlikely and magnificent 1-0 victory over England in World Cup 1950 (held then as now in Brazil) featured a bunch of part-timers putting the boot to the “Kings of Football.” It didn’t require so much as a baby aspirin. Since then, working on the “no pain no gain” principle so beloved of hackneyed American high-school football coaches, the U.S. has enjoyed a steady climb up the world rankings and some encouraging advances in international tournaments, including a World Cup quarter-final in 2002. Still, in the last sixty-four years, there have been more losses and draws—a draw in the U.S. means, as we all know, a loss—than wins. But not many Americans were following the team during all that. I imagine only a fraction of a ton of painkillers were consumed.

Now, though, after this week’s stirring 2-1 victory over Ghana, the 80-percenters are getting on-board big-time, and The New York Times is reporting that a majority of Americans are convinced, unlike their coach, that the USA can triumph in Brazil. The team is clearly riding for a fall, isn’t it? They play Portugal on Sunday. One would think it’s pass-the-Tylenol time.

But not so fast. The heart has its reasons which reason knows nothing of, and among these is that other central facet of American culture, God. Could He save the day? On Monday, a BBC TV commentator scolded the USA’s Clint Dempsey for not singing his national anthem when it was played. The English are not that much into God—a quarter of the population has “no religion,” and in the 2001 census 390,127 individuals listed themselves as “Jedi Knights”—which is probably why the commentator missed the fact that in all likelihood Dempsey was not dissing but praying. He certainly crossed himself at one point, but I can’t remember if this was post-anthem or right after the superb goal he scored thirty-two seconds into the game against Ghana.

God, of course, has shown more than a passing interest in the world of sports for some time now. Players often thank Him when things go well. He clearly likes winners. I have never seen a goalkeeper point skywards after a ball has rolled through his legs into the net.

So what’s it going to be, America: heavenly intervention or a handful of extra-strength brand name? Looking at the suspiciously over-exuberant support offered by the euphoric crowd of 20,000 USA supporters gathered in the Arena das Nunas last Monday, I think nothing more may be needed than whatever it was those people were on. Free pints of caipirinha for all, and bring on Portugal with its iconic star Cristiano Ronaldo. USA! USA!

Jonathan Wilson’s work has appeared in The New Yorker, Esquire, The New York Times Magazine, and Best American Short Stories, among other publications. He is the author of eight books, including Kick and Run: Memoir with Soccer Ball. He lives in Massachusetts.

How to Piss Off W. Somerset Maugham, and Other News

You shouldn’t have said that. Somerset Maugham in a portrait by Carl Van Vechten, 1934.

Beneath Picasso’s painting The Blue Room, infrared technology has revealed another painting, “a portrait of a man wearing a jacket, bow tie, and rings.”

Literary Feud of the Day: Patrick Leigh Fermor versus W. Somerset Maugham. The latter called the former “a middle-class gigolo for upper-class women,” but “at least a small part of Somerset Maugham’s hostility can be attributed to an evening during which Leigh Fermor, a guest at the older writer’s table, entertained the company by making fun of his host’s stutter.”

Pablo Delcán on his complex, eerie cover designs for the Spanish editions of Jeff VanderMeer’s Southern Reach trilogy: “It was about giving a twist to the natural and known world, a way of making it fictional and distorted.”

Charles Barsotti, one of The New Yorker’s greatest cartoonists, died yesterday. Among his many masterworks is a cartoon of a cheerful God talking to a nervous new arrival in heaven: “No, no, that’s not a sin, either. My goodness, you must have worried yourself to death.”

An interview with Barbara Cassin, whose Dictionary of Untranslatables is now available in English: “I wanted something else, and this something else is rephilosophizing words with words and not with universals. And these words are words in languages. Let us see what it means, how it can bring us to dwell a little bit on the difference between mind, Geist, and esprit. What happens if we look at the words, where they emerge and where they philosophize? Let us have a look.”

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers