The Paris Review's Blog, page 690

June 25, 2014

An Exhilarating Head Trip

P. H. Newby; date unknown. Photo via phnewby.net

The old girl kept writing and complaining about the police. It was enough to start Townrow on a sequence of dreams. Night after night he floated in the sunset-flushed, marine city. He could smell the salt and the jasmine. He dreamed that Mrs Khoury, Mr Khoury and he were all sailing out of the harbor in a boat that slowly filled with water. He dreamed he was in a hot, dark room with a lot of men who argued and shouted. It must have been in the Greek Sailing Club because when a door opened there were oars and polished skiffs; and opposite, high over Simon Artz’s, of the other side of the Canal, was Johnnie Walker with his cane and his top hat setting off for Suez. Or was it the Med.?

So begins P. H. Newby’s Something to Answer For, the 1969 novel that won the first-ever Booker Prize. “The Booker was not, as it is now, a high media event,” Anthony Thwaite wrote in an obituary for Newby in 1997. “I remember the then–sales director of Faber & Faber, the book’s publisher, telling me that the prize probably resulted in no more than about four hundred extra copies.”

That’s a shame, because Newby, who was born today in 1918, deserved, and deserves, more attention. Graham Greene called him “a fine writer who has never had the full recognition that he deserves,” and that’s as true now as it was in Newby’s lifetime. Very few of his twenty novels are still in print; in the whole of The Paris Review’s archive, his name comes up only once, in Truman Capote’s 1957 Art of Fiction interview: “Well, who are some of the younger writers who seem to know that style exists? P. H. Newby, Françoise Sagan, somewhat.”

In additional to his success as a novelist, Newby enjoyed a long career as a broadcast administrator—he rose through the ranks to become the managing director of BBC Radio. He lived in Cairo from 1942 until 1946: it was “like living in a human laboratory, in which there were no inhibitions,” Thwaite writes, and it informed a number of his novels, Something to Answer For among them.

Something is set in the Egypt of 1956, during the Suez Crisis, and it boasts a wondrous sense of place—but it’s also a deeply interior novel, exploring winding epistemological corridors by way, oddly enough, of blunt force trauma to the head. Its protagonist, Townrow, has sustained some kind of cranial injury, which leaves him increasingly disoriented and destabilizes the text. As Sam Jordison, who in 2007 embarked on a quest to read every Booker Prize–winning novel ever, described the novel’s plot in the Guardian, Townrow

Something is set in the Egypt of 1956, during the Suez Crisis, and it boasts a wondrous sense of place—but it’s also a deeply interior novel, exploring winding epistemological corridors by way, oddly enough, of blunt force trauma to the head. Its protagonist, Townrow, has sustained some kind of cranial injury, which leaves him increasingly disoriented and destabilizes the text. As Sam Jordison, who in 2007 embarked on a quest to read every Booker Prize–winning novel ever, described the novel’s plot in the Guardian, Townrow

is never quite sure what’s going on—and nor are the readers who follow his bemused progress. He knows he’s gone to Egypt to see the widow of his recently deceased friend Elie and perhaps defraud her of her estate. He can’t say much more with any clarity. He’s unsure for instance whether he saw Elie’s burial at sea or dreamt it. He misremembers scenes and conversations he’s had with Leah Strauss—the woman he’s fallen in love with. He’s overwhelmed by the ongoing events surrounding the ongoing Suez crisis and can’t even remember whether he’s British or Irish, involved or neutral in the whole affair.

It’s all very distressing for Townrow, who just wishes that he could “point his mind at something.” For the reader, however, it’s an exhilarating head trip. Scenes are rewritten as Townrow re-remembers them; conversations are willfully and gleefully contradicted; plot strands are wrapped around each other. All that remains constant is the absurd march of history and the brief, bloody Suez invasion, which Newby depicts in a few virtuoso bursts of bracingly sharp detail.

Kirkus Reviews thought of the book as “A little Kafka—a little Greene—a little Ambler, in a charade which is also an expertly agile entertainment poised between the unsuspected and the unknown.”

Highs in the Mideighties

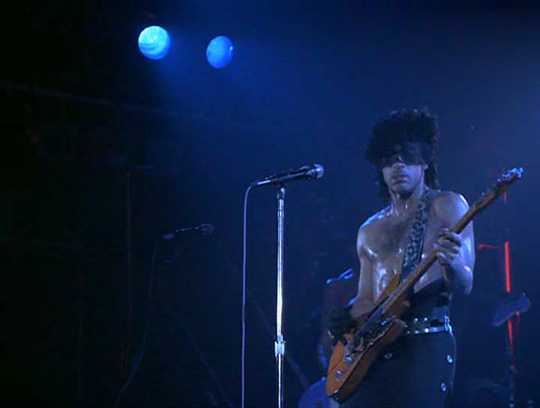

Recalling the heyday of Prince and Madonna on the thirtieth anniversary of Purple Rain.

Twenty-four-hour music television, the brainchild of a TV-spawned pop star, the Monkees’ Michael Nesmith, began broadcasting in August 1981 with the Buggles’ “Video Killed the Radio Star.” MTV was everywhere within eighteen months. If new pop and postpunk had gleefully and rapidly rewritten rules, taking music forward in a constant revolution of purpose and invention, their aftermath was an era of momentum for its own sake. Things got ever shinier, greed and need replaced innovation: conservatism was a force and a problem both outside and within eighties pop.

Two new names appeared in this froth of newness. Both stood out from the crowd, both clearly demanded attention, worship, devotion: Prince and Madonna. These were names that couldn’t have existed at the dawn of modern pop, names that baited royalty and religion.

Both based their sound on electronically processed dance music, allowing them the opportunity to change style from record to record in a way that seemed innovative, one step ahead of the pack, like Dylan or Bowie before them. Both had egos the size of mansions. Both had a new hunger for success, for money. Both used MTV to become stars, and both used movies (Desperately Seeking Susan, Purple Rain) to make the jump from stardom to superstardom. Sex! Religion! Gigolo! Whore! Purple! Cone bra! No one could accuse Prince or Madonna of underplaying their hands. And, eventually, both challenged Michael Jackson’s place at the very top of the pop empire; by the eighties’ end Madonna had (arguably) toppled him in the popularity stakes, and Prince had (certainly) creatively eased past Jackson with the most streamlined, silver-finned R&B of the decade. These were their similarities. In other respects they were quite different.

Prince had first appeared with the itchy falsetto disco of “I Wanna Be Your Lover” (no. 11, ’79) and was presented—not least by himself—as a teenage prodigy. He grew up in the largely white city of Minneapolis: “The radio was dead, the discos was dead, the ladies was kind of dead. If I wanted to make some noise, if I wanted to turn anything out, I was gonna have to get something together. Which was what we did. We put together a few bands and turned it into Uptown.”

He wanted to be everybody’s lover and—unlike most disco acts—was quite at home with lyrics about oral sex, incest, and Dorothy Parker. This set him apart. By 1983 he was channeling Sly Stone and the Beach Boys on “Little Red Corvette,” and a year later Newsweek was calling him “the Prince of Hollywood” as Purple Rain—starring Prince as the Kid—grossed $80 million.

Prince was hyperactive, more productive than any major star since the Beatles; some of his most commercial songs—“Manic Monday,” “Nothing Compares 2 U”—were tossed off as demos for others less prodigiously gifted to take to number one. There was always more in the locker.

Madonna, on the other hand, was the most grasping pop star in history. She was all Blonde Ambition, a triumph of the will. If her roots were always showing (suburban, Italian American, Catholic), it was still almost impossible to feel her soul. Rosaries were for show, crucifixes were worn like candy necklaces; if she ever went to confession it didn’t come across in her lyrics. She was a highly sexual, strong woman commodifying her own sexuality. She was a billboard. She was a material girl and proud of it.

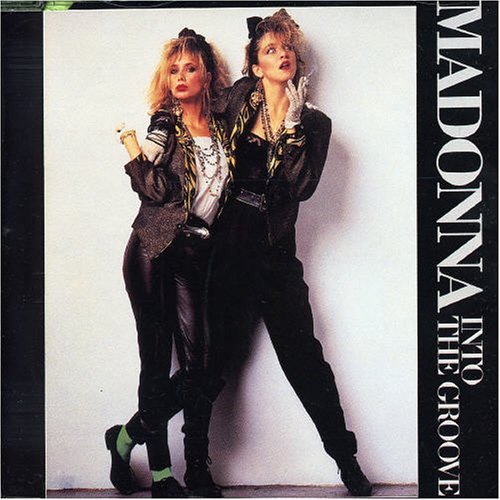

And if you listen to The Immaculate Collection it succeeds on almost every level. Like Lesley Gore before her—with Quincy Jones, Jack Nitzsche, Thom Bell—Madonna used the best young producers (John “Jellybean” Benitez, Stephen Bray, William Orbit, Stuart Price) to get to the top and stay at the top. Each step was perfectly conceived, each single a stop on the way to her ultimate destination—iconhood. “Holiday” and “Lucky Star,” in 1983, were instant club classics, floor-fillers for the masses, with a delicate ache to take “just one day out of line”; 1984’s “Like a Virgin” and “Material Girl” (the video for which had her playing Marilyn Monroe for the first time) were pubescent pop, there to antagonize and irritate, and to set up her persona; “Into the Groove” (her first number one, in ’85) was the invitation for everyone to partake, with its cool, crooked finger—“I’m waiting!” And the world succumbed. A few career-hardening singles later, Madonna could take eighteen months out and return with an event single, “Like a Prayer,” which (because it had to be) was her best yet. At this point, in 1989, she owned pop, and it was hers to lose.

The role-playing had been there from the start. “There was a real transformation,” said former schoolfriend Kim Drayton. “In the sophomore year she was a cheerleader with smiles on her face and long hair; very attractive; then by her senior year she had short hair. She was in the thespian society, and she didn’t shave her legs any more, you know, like all of us did, and she didn’t shave her armpits. Everyone was like, ‘Oh, what happened to her?’” Dancing became her escape route. The eldest girl in a family of eight children, her mother had died when she was just five. Her dad had been a defense engineer for General Dynamics; he worked long hours, and Madonna didn’t get on with her stepmother, who made her help out changing diapers. “When all my friends were out playing, I felt like I had all these adult responsibilities … I saw myself as the quintessential Cinderella,” she said. So she danced in the backyard to Motown 45s with her black schoolfriends, and she went to gay clubs in Detroit where she didn’t feel men looked at her like a hard-ass. By the time she arrived in New York and hung out at the Danceteria in 1982, she had the moves, if not yet the look or the voice.

Three years on she recorded “Into the Groove” and, for me, it was her peak. The most sublime example of pop on pop since “Do You Believe in Magic,” it was all about saturating your mind and freeing your body, a three-minute, unrelenting chime of joy: “Only when I’m dancing can I feel this free.” She came from nothing, a real-life Cinderella, and she made some of the greatest records of the eighties, became a true legend. It’s “Papa Don’t Preach” with an exceptionally happy ending.

Three years on she recorded “Into the Groove” and, for me, it was her peak. The most sublime example of pop on pop since “Do You Believe in Magic,” it was all about saturating your mind and freeing your body, a three-minute, unrelenting chime of joy: “Only when I’m dancing can I feel this free.” She came from nothing, a real-life Cinderella, and she made some of the greatest records of the eighties, became a true legend. It’s “Papa Don’t Preach” with an exceptionally happy ending.

So why do I struggle to love Madonna? On one level it was her lack of specialness—take away the drive and she’s fine, she’s good. She’s as good as Kim Wilde. Her voice had a squeaky cuteness, a predatory squeaky cuteness that contradicts itself. On another, less personal level, she was a cultural sponge. Once Madonna co-opted a fashion, a look, then it belonged to her. Try imagining anyone who has emerged in her wake pulling off the Monroe look—even someone as big as Christina Aguilera, Kylie Minogue, or Lady Gaga: immediately you think, it’s a bit Madonna. In this respect, she’s been an awful role model for women and has done a lot of harm without giving much back. Like Margaret Thatcher, who, as prime minister, never allowed another woman MP into the cabinet, Madonna acted as if she was the only woman allowed in pop.

Prince was always more playful, at once generous and controlling, a benevolent dictator—the Tito of pop. He started a label called Paisley Park, writing and producing for the likes of the Time, Sheila E., and Apollonia, the busty costar of Purple Rain; then he spent $10 million building a white modernist Paisley Park studio complex. His jammy fingermarks were all over the label’s output, at every level. For the cover photo of the Time’s Ice Cream Castle he instructed Paul Peterson to wear an orange suit. He also wanted Mark Cardenas to wear blackface, which was an affectation too far. According to Peterson, “He said, ‘If you wear blackface people will notice you.’ Well, he would have been right there.”

Unlike Madonna, Prince was all contradictions: black funk and white rock, the sound of the future pilfering from the past’s cabinet of curiosities, and—like Little Richard before him—unending lust and adherence to the Bible. This was fully realized on 1984’s international breakthrough album, the soundtrack to Purple Rain. It was put in capsule form on “Darling Nikki,” a violent grind of a track that referenced female masturbation but, if played backward (Prince had done his Beatles homework), the fade included the spoken lines “Hello. How are you? I’m fine, because I know the Lord is coming soon.”

It must have caused a few people who had bought the album for “Take Me with U” to go bright red. Purple Rain was like a condensed CV, each track pointing in a different possible future direction, splendidly and unquestionably announcing the arrival of a legend. The first single taken from it, “When Doves Cry,” was also his first U.S. number one and, just for larks, it didn’t include a bassline. (It was the first hit single to lack a bassline since Andrew Gold’s “Never Let Her Slip Away” in 1978.) “Take Me with U” was eighties Mersey-beat—as if Prince was seeing Purple Rain as an update of A Hard Day’s Night—dressed up with some gorgeous lovelorn strings and a dynamic, slightly disturbing, Brian Wilson–like intro and coda. “Let’s Go Crazy” (another number one) was synth glam, a vari-speed “Rock and Roll Part 2” in double time, its lyrics indecipherable beyond a camp religious intro, panting sounds, and a clarion call of “Let’s go crazy! Let’s get nuts!” The title track resurrected the emotional mudbath of John Lennon’s “Mother” and the dead-handed thud of the Band; a parody of white rock’s self-pity, it may not be a coincidence that this is the song that brings Prince’s character, the Kid, deliverance in the movie.

Purple Rain spent a dozen weeks at the top of the U.S. album chart. Prince’s place at the table was confirmed when the British press gave him the kind of nickname which they reserve for only the biggest pop stars, the ones who can rise no higher: Macca Wacky Thumbsaloft, Dame David Bowie, Wacko Jacko, Madge, and Ponce. You didn’t need the ire of the Sun or the National Enquirer when Smash Hits was there to remind superstars that no one, but no one, is untouchable.

With the Kid and his busted-up success story, Prince showed a sleight of hand not seen since David Bowie’s Ziggy Stardust. Purple Rain was the pop event of the year, and it was a skin he could easily shed. The sequel, 1985’s Around the World in a Day, was built on a bed of the romantic woozy strings from “Take Me with U”; from its psychedelically ornate cover on, it was the Lovin’ Spoonful put through a Paisley Park filter; the title track and “Raspberry Beret” were sunny-afternoon hijinks, sweet utopian pop.

No wig-outs or workouts, just marshmallows. It wasn’t given a major push, as if Warner Brothers didn’t think it could hold the same crossover appeal as Purple Rain. Critically and commercially, in the conservative environment of the mideighties, it felt like Prince was being upbraided for not giving us Purple Rain 2, for going too far.

Prince shrugged, moved on. “It is true I record very fast,” he told MTV. “It goes even quicker now the girls help me … the girls meaning Wendy and Lisa.” Guitarist Wendy Melvoin could barely contain her pride in Rolling Stone: “I’m sorry, no one can come close to what the three of us have together when we’re playing in the studio. Nobody!” She was right. By the time of Parade in 1986, and its companion movie Under the Cherry Moon, Prince was untouchable. He could indulge his fantasies of upper-class English girls on screen (Francesca Annis and a young Kristin Scott Thomas were the love interests in Under the Cherry Moon) and still come over as impish rather than creepy. He’d try to be the romantic suitor, try to keep his fly zipped up, but always had that glint in his eye within a matter of seconds. “Girls and Boys” was great, but “Kiss” (no. 1, ’86) was greater, a super-parched dancer containing killer eighties map refs: “You don’t have to watch Dynasty to have an attitude.” Within a year Prince released a double album, Sign ‘O’ the Times, which contained no filler at all—he had found Paisley Park hired hands who could keep up with him, egg him on to greater heights of screwball abandon. “Starfish and Coffee”? And a side order of ham. “Wear something peach or black,” he asked fans before his 1987 shows. With a new addition, the writhing dancer Cathy “Cat” Glover, he made the Sign ‘O’ the Times tour the most spectacular of the eighties, pushing her up against a giant silver heart during “If I Was Your Girlfriend” that then tipped up, dumping the two lovebirds backstage. He didn’t miss a single beat. And, again, again, he moved on.

Madonna also kept plugging away at a parallel film career, though she didn’t have a predilection for English gents with country houses to blame for the box office failure of Who’s That Girl and Shanghai Surprise. Given their similar tastes, it’s no coincidence that Madonna’s best album, 1989’s Like a Prayer, bore a heavy Prince footprint. It was a tightrope-walking blend of the spiritual and carnal; Prince aside, no one had pulled this stuff off since Elvis. There was even a duet between the two pretenders to Jacko’s throne (the crisp “Love Song”), which must have made the King of Pop frown just a little.

Even so, both Prince and Madonna hit a crisis as the eighties turned into the nineties. Neither had embraced either hip hop’s golden age or the house and techno revolution (which revolved much slower in its homeland). Both were seen entirely as eighties icons—they didn’t have Michael Jackson’s prehistory to loosen their ties to that specific decade. Both decided to ratchet up their output.

In Prince’s case, this meant reminding everyone of why they loved him in the first place. He remained stubbornly himself, sticking to the landscapes he knew best, sure of his own greatness. First he recorded, then pulled, an album—The Black Album. It was bootlegged heavily but was still spoken about more than it was heard. Then he made a third movie, Graffiti Bridge, in 1990. It was an almost exact replica of Purple Rain, with Prince as the moody singer, sitting on his motorbike, pouting like a lady. All at once, things fell apart. The Black Album filtered through and turned out to be quite tedious, all dry-hump funk. Graffiti Bridge was a greater error as it was such an overground failure. There were no good songs, Prince looked old, his hair was horrid. Everything about it seemed lazy. For somebody so forward-looking, it was a catastrophic error of judgment.

Madonna, similarly, lost her sense of timing. In the space of what seemed like weeks, she released a career retrospective (The Immaculate Collection), a new album (Erotica), and a book of photographs called Sex. No matter what the new album contained, photos of the world’s biggest pop star in the nude were always going to trump it.

You could argue a case for Sex being a political move in the culture wars of 1990. The same year saw Robert Mapplethorpe’s nudes facing an obscenity trial; was this Madge showing solidarity with the cultural left? It could also be seen as the work of someone who was now being treated as a new strain of feminist by universities, one who was seizing the means of porn production. Or you could argue that she had nowhere else to go—Madonna was as ubiquitous as the Beatles had been; splitting up wasn’t an option, but dressing down was.

Looking back, the Sex book feels like one of the most radical moves made by anyone in this fifty-year story. But in 1990 it was regarded generally by those open to it as bad art, as bad porn, and by those against it as a publicity stunt. Either way, releasing the Erotica album so soon afterward was Madge overload and none of the singles from it reached number one. This is a shame, as it was her best album—“Justify My Love” preceded it and was Madonna at her most sensuous, all spooked Mellotron chords, whispering rather than screaming. The title track was almost as good, a 98 bpm Balearic rhythm topped with a simple but dark three-note piano motif: “If I take you from behind, push myself into your mind…” Well, it worked for me. Other singles from the album (“Rain,” “Deeper and Deeper,” “Bad Girl”) were good solid disco pop, based around minor chords, and were notably more mature and less attention-grabbing than anything she’d done before. None of this mattered. She’d taken her clothes off and that was the entire Madonna story. The album flopped.

Looking back, the Sex book feels like one of the most radical moves made by anyone in this fifty-year story. But in 1990 it was regarded generally by those open to it as bad art, as bad porn, and by those against it as a publicity stunt. Either way, releasing the Erotica album so soon afterward was Madge overload and none of the singles from it reached number one. This is a shame, as it was her best album—“Justify My Love” preceded it and was Madonna at her most sensuous, all spooked Mellotron chords, whispering rather than screaming. The title track was almost as good, a 98 bpm Balearic rhythm topped with a simple but dark three-note piano motif: “If I take you from behind, push myself into your mind…” Well, it worked for me. Other singles from the album (“Rain,” “Deeper and Deeper,” “Bad Girl”) were good solid disco pop, based around minor chords, and were notably more mature and less attention-grabbing than anything she’d done before. None of this mattered. She’d taken her clothes off and that was the entire Madonna story. The album flopped.

How did these icons dig their way out of a hole? Prince got a bigger shovel. He toughened up his sound and added a few more cuss words for “Sexy MF” and “My Name Is Prince,” both of which were useful additions to his catalog, but it still felt like he was playing catch up. In the eighties his music had been the story; in the nineties his battles with the music industry—writing “slave” on his cheek, changing his name to the Artist Formerly Known as Prince—became the story, and it was a turn off. By 1994, when he had his last Top 10 hit with “The Most Beautiful Girl in the World,” he felt like a relic.

Madonna realized that no matter what she did after Sex, it would be an anticlimax. Besides, everyone save her hardcore fans had their knives sharpened. So she pretty much disappeared, a queen in exile as grunge and riot grrrl took the heat off her. She started her Maverick record label and signed Alanis Morissette, whose Jagged Little Pill album sold thirty-three million copies and moved the discourse of female empowerment on by proxy. By the time she returned with Bedtime Stories in ’95 she could play godmother to the riot-grrrl scene, and Courtney Love was glad to back her up. With fresh impetus, she cut Ray of Light and Music, both sonically supermodern; once again she was raising the bar for club-orientated pop. She wore the crown.

Bob Stanley has worked as a music journalist, DJ, and record-label owner, and is the cofounder of the band Saint Etienne. He lives in London.

Excerpted from Yeah! Yeah! Yeah! The Story of Pop Music from Bill Haley to Beyoncé by Bob Stanley. Copyright © 2014, 2013 by Bob Stanley. With permission of the publisher, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. All rights reserved.

A Dream of Toasted Cheese

An early drawing by Beatrix Potter. Image via Retronaut.

Sir Henry Enfield Roscoe was a prominent nineteenth-century chemist—a pioneer in photography and the first to obtain the element vanadium in its pure form. He was also, incidentally, Beatrix Potter’s uncle. In 1906, he wrote,

I also wrote a First Step in Chemistry which has had a large sale. With reference to this little book, I here insert a reproduction of a coloured drawing by my niece, Miss Beatrix Potter, as original as it is humorous, which was presented to me by the artist on publication of the work.

Although by 1906 Potter was already the successful author of Peter Rabbit, The Tale of Squirrel Nutkin, and The Tailor of Gloucester, she would’ve been a girl when First Step in Chemistry was published. The image, however, is interesting not merely because of its accomplished style—the precocious Potter received childhood art lessons—but because it recalls her interest in science. While she’s well known now as a conservationist and animal artist, her early scientific interests were broad: she studied archeology and entomology and made a serious study of mycology. Indeed, in 1897 she had a male friend submit her paper “On the Germination of the Spores of the Agaricinea” to the Linnean Society.

Roscoe supported her in these endeavors: using his university connections, he arranged meetings for Beatrix with prominent botanists and officials at Kew Gardens. The congratulatory picture is a testament to their affectionate relationship. Nevertheless, the image, while fantastic, is peculiar: the mice seem to have taken over the lab by night to conduct risky cheese-toasting experiments with terrifyingly large Bunsen burners. And while the bespectacled lead mouse seems scholarly enough, behind him, the scene is anarchic: the effect is more that of Ratatouille than of a well-organized laboratory. And let’s face it, the resulting treat is less than tempting. The mice are sort of like scientific Tailors of Gloucester—albeit less organized, and less altruistic.

Reality Bites

One of the many memes to reemerge after Luis Suárez’s latest biting incident.

When Zinedine Zidane head-butted Marco Materazzi during the 2006 World Cup final between France and Italy, he more or less blew any chance France had of winning the game. Materazzi is believed to have made some provocative suggestions about Zidane’s sister, and what’s winning the World Cup next to defending one’s sister’s reputation?

Luis Suárez’s action yesterday—he left an impression of his teeth in Giorgio Chiellini’s left shoulder—will, after his inevitable ban, have the same effect of terminally harming his country’s chances of victory. But unfortunately for him, Suárez doesn’t have a chivalric excuse.

Human beings frequently act against their own self-interest. Think of the highly successful British pop group KLF, two of whose members, self-described as the K Foundation, withdrew a million pounds of their own money from the bank back in 1994 and ceremonially burned it. It seemed like a good guerrilla art–type idea at the time, and then later it didn’t. But, like Zidane, K Foundation had a reason for acting as they did, more obscure but no less real.

That soccer players from time to time act as street-fighting men, butting, punching, and kicking, shouldn’t really surprise us: they are by and large young, spirited, tough guys, from tough backgrounds, involved in a game where you run around kicking and heading and frequently miss the object of your attention. Not long before the Suárez bite, Italy’s Claudio Marchisio was sent off for going in high and studs-up against the leg of Egidio Arevalo Rios. Intentionally or not, he could easily have broken Rios’s leg. In such cases the referee’s red card quiets the baying fans in the coliseum. A bite, however, plumbs the atavistic soul in all of us, and sets off a frenzy of response that is not so easily muted.

It’s the unmotivated, animal action that gets to us. So here, on Twitter, is a video of Suárez as Jaws, emerging from the ocean, choppers bared, to chomp a hole in Roy Scheider’s fishing boat.

Italy is the best country in the world at closing things down. It has an advanced system of wildcat strikes and a government office that monitors them to provide information for public benefit. Its labor force is tactically sophisticated—and so, too, its soccer team. Shut down a transport system? Shut down Uruguay? No problem. For an hour in yesterday’s match everything went according to plan, then Marchisio was sent off. Even after this setback, Italy looked more than capable of salvaging the necessary draw to send them through to the next round. Then Suárez bit Chiellini, got away with it, and a minute later Diego Godin rose to meet a corner, twisted, and had the ball bang off his back and past Buffon for Uruguay’s winning goal.

After the game, an unrepentant Suárez offered reporters an excuse for his behavior: “These situations happen on the field. I had contact with his shoulder, nothing more, things like that happen all the time.” Now he waits for reality to bite.

Jonathan Wilson’s work has appeared in The New Yorker, Esquire, The New York Times Magazine, and Best American Short Stories, among other publications. He is the author of eight books, including Kick and Run: Memoir with Soccer Ball. He lives in Massachusetts.

A Freud for Every Season, and Other News

Ignatio Garate Martinez, Sigmund Freud, 2012; image via Wikimedia Commons.

“I suppose it says something about our era that the Freud we want is Freud the translator, rather than Freud the doctor—the conversational, empathetic, curious Freud, rather than the incisive, perverse, and confident one.”

Read to your baby as early as you can, scientists say. If you have a baby, drop everything and go read to him now. It will help “immunize” him “against illiteracy.” Whether some texts are better vaccinations than others remains to be seen.

The latest installment of Henri Cole’s Paris diary: “This morning I observed a beautiful, sleeping chipmunk. Animals—like humans—seek a safe, sheltered place to sleep. Deer make a bed out of unmowed grass, rodents burrow in the soil, and apes create a pallet of leaves. In Paris, I sleep alone on a thick foam mattress. Because my dreams are incoherent, I lose any sense of time or place. Often I fly.”

A new radio show, Meet the Composer, proves that contemporary composers are neither bland nor square: “My experience with composers is superpersonal,” the host says. “I always do all of my commissioning at 3 a.m. at the bar, after we’ve been hanging out forever.”

Seamus Heaney, the man, the poet, the app: “Too often arts organizations and publishers resort to stunts and gimmicks to add some glitz to poetry, and issue terrible statements about how they want to make it ‘relevant’ and ‘trendy.’ If a poem needs digital bells and whistles to become relevant, it’s obvious it wasn’t very good in the first place … this app adds context and insight to the tales without compromising or clouding them with too much technical faff.”

June 24, 2014

Smuthound

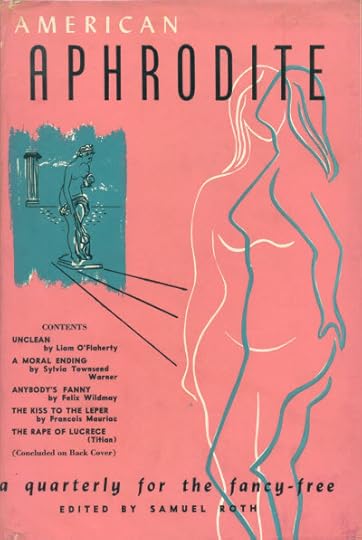

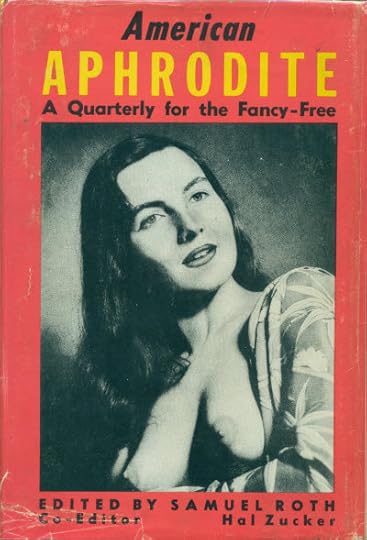

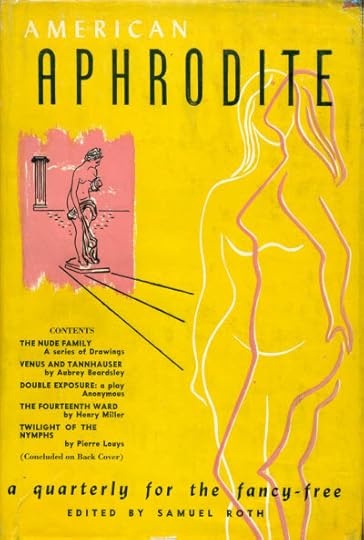

Warning: the slideshow below contains images deemed obscene in the fifties.

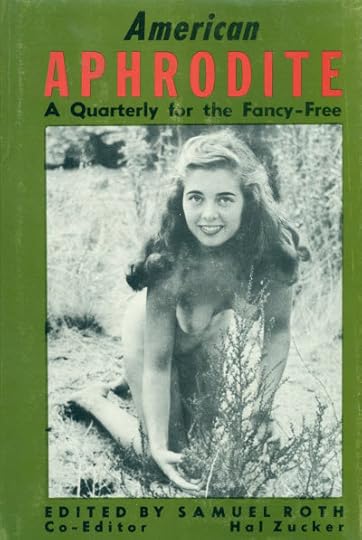

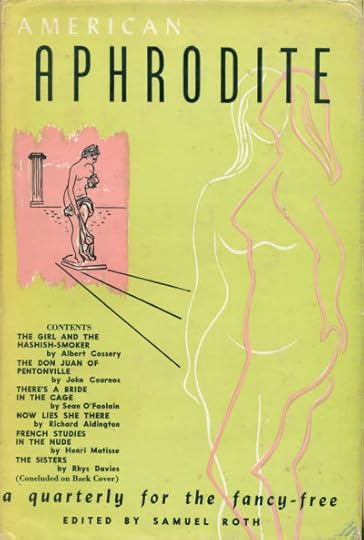

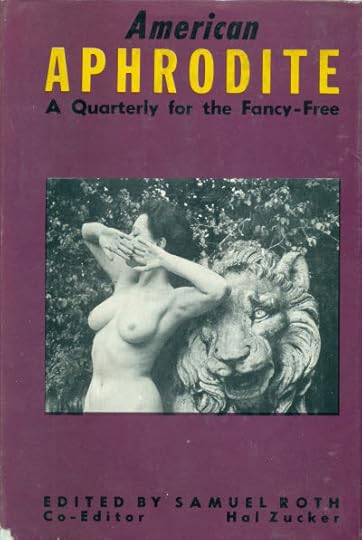

Fifty-seven years ago today, the Supreme Court rendered its decision in Roth v. United States, the preeminent obscenity case of the time. That Roth isn’t Philip—not that he’s any slouch when it comes to indecency—but Samuel, a widely reviled publisher perhaps most remembered today for bootlegging portions of Ulysses. As Michael Bronsky described him in a piece for The Boston Phoenix,

Roth became so notorious as both literary pirate and smuthound (the word in use at the time) that he was attacked in The Nation and The New Yorker as a literary fake and social nuisance. Vanity Fair included him, along with the up-and-coming Adolf Hitler, in its 1932 photo essay titled “We Nominate for Oblivion.”

In the course of his long and thoroughly ribald career, Roth often found himself dragged to court—this particular case saw him violating a federal statute that banned the transmission of “obscene, lewd, lascivious, or filthy” materials using the postal service. Roth had been doing just that: his magazine American Aphrodite (“A Quarterly for the Fancy-Free,” the covers of later editions said) was the finest in literary smut. (And trust us: The Paris Review knows a thing or two about literary smut.)

Impressively—and perhaps profligately—American Aphrodite was a clothbound publication; take a look at the covers above to get a sense of its tenor. The titles of the work Roth published are by turns gently titillating (“The Willing Maid a Day Too Young,” “A Lover Without Knowing It,” “Take It Off! Take It Off!”), ridiculously frank (“Gallery of Big Women in the Nude,” “Japanese Ladies Taking Their Bath”) or simply bizarre (“The Two-Thousand Pound Raspberry,” “Shake Your Goat-Leg,” and a four-part series called “The Women of Plentipunda”). Bronsky writes,

American Aphrodite usually featured things like mild erotic line drawings, some piece of long-out-of-print British literature (the “scandalous” seventeenth-century plays of Aphra Behn appear in many issues), a “bawdy” new translation from Chaucer, and something truly shocking, like nude photos of ten-year-old girls taken in Victorian brothels.

And in his 2013 book, Without Copyrights: Piracy, Publishing, and the Public Domain, Robert Spoo explains that the magazine

contained a typical Rothian stew of slightly dated literature and winking erotica, though some of the material, such as Aubrey Beardsley’s unfinished novel Venus and Tannhäuser, contained stronger sexual content. Woodcuts and drawings of thinly clad or nude women adorned the quarterly’s pages, along with frank poems, such as one inquiring of God whether it is wrong to desire “Two women in one affection, / Two vulvas, four breasts” … Roth’s editorials chided “Madame Post Office” and other official powers for repressing “our rights as American citizens engaged in interpreting the cultural and emotional motives of our time.”

For better or worse, that repression continued with Roth v. United States, in which a six-person majority submitted that obscene material wasn’t protected by the First Amendment, and that said material could be defined that whose “dominant theme taken as a whole appeals to the prurient interest [to the] average person, applying contemporary community standards.” The court maintained that Congress could ban any material fitting this definition; it upheld Roth’s conviction, and he went to prison. The verdict held until 1973, when it was superseded by Miller v. California, which also involved sending smut through the mail—another story for another day.

Rules of Civility

Detail from Pierre-Auguste Renoir’s Two Girls Reading, ca. 1890.

Over the weekend, someone asked me how I’d argue for the survival of the print book. I was taken aback; it felt like being asked to defend food against Soylent Green, or sex against the exclusive domain of artificial insemination. But I considered the question carefully, and aside from the obvious arguments, here’s one way I like to think of it.

When I was younger, I used to think setting people up would be sort of like recommending a book you loved: whether or not it worked out, a friend would know you’d tried in good faith to match her tastes and interests, and not hold it against you if you’d gotten it wrong. At best, her life would be enriched; at worst, she’d still be able to recognize what you saw in the other person. In any event, once you’d made the introduction, the arrangement ceased to have anything to do with you.

Instead, I discovered that setting people up is more like recommending a movie—specifically, a comedy. And if a friend doesn’t enjoy—doesn’t get—a comedy you like, somehow both of you feel betrayed, and some small part of you thinks less of the other. And there is the horrible knowledge that the person who dislikes always has the advantage.

Not, mind you, that I’ve done a great deal of matchmaking. My first experiences with it were so off-putting that I swore it off at a pretty young age. It’s not that every attempt was a disaster; one set of friends actually hit it off, and dated for about a year. But that ended up being harder still; the stakes were higher and inevitably, when they split up, my relationship with one of the two grew weaker.

This is as good an argument as I have for the survival of the book: book recommendation is intensely social and inherently civilized. Time spent with a book is almost never time wasted; even those reading experiences that are less than enjoyable are not without value.

The reaction one has to a film or music is often visceral, emotional. While a book can certainly engage emotions—as I write this, A Fault in Our Stars is still heading up the best-seller lists—the experience is always at least partially cerebral. I have sometimes almost hated friends who were wrong (and it really does feel that black and white) about movies; the heated There Will Be Blood fights of 2007 come to mind. I don’t think I have ever had that reaction while disagreeing about a book, and I’ve talked about a lot of books with a lot of people.

When I was a kid, I had a series of note cards sporting an image of a young girl reading the words, “A Good Book Is a Good Friend.” (Why, yes, I did subscribe to Cricket!) The Internet ascribes these words to a 1901 issue of The Outlook, and tells me that it is part of a longer quote:

“A good book is a good friend. It will talk to you when you want it to talk, and it will keep still when you want it to keep still—and there are not many friends who know enough for that.”

There’s little arguing with that, but I’d go further: a good book facilitates relationships. So does a bad one. After all, even if your friend doesn’t like it, you can just put it back on the shelf. And they’ll both speak to you the next day.

Shades of Oranje

The Netherlands and its flexible formations.

Louis van Gaal, team manager for the Netherlands, in 1988, as interim manager with Ajax.

France ’98 remains the standard for World Cups in my lifetime. The number of great players in their prime, the quality of the games in the knockout rounds, the last-second drama of the now (thankfully) abolished Golden Goal—a rule by which the first team to score a goal in extra time won—it all proved irresistible. France as a nation had turned to embrace the right, and up had risen the National Front; nevertheless, people traveled in happy droves to spend days, if not weeks, in their dream of Romantic France. During those June days, football flourished under what should have been a crushing paradox of love and hate, more felt than fully understood.

Brazil ’14 is not France ’98, but it’s getting close. Its group stage has been unquestionably better. Both tournaments have been played in times of terrible turbulence, providing a welcome distraction for some and annoying others—as in 1998, regardless of the result, it will be a national triumph and a national disgrace.

Yesterday, a friend asked me how I feel about it all. But do we feel about anything as an “all” or a whole? Aren’t there portions we consciously or unconsciously admire, see, unsee, or detest? At times, the games in this World Cup have been so good that I’ve had to close my eyes and put my head back in order to clear my mind, to review what I’ve just seen, a team’s movement, or the sounds of the match, the commentators chasing the game, the mazy motion of New York City midday summer noise sidewinding through my open windows.

Yesterday, I found myself closing my eyes in dismay. The Netherlands, a.k.a. the Oranje—in homage to their royal color, inherited from Willem van Oranje–played Chile for the top spot in Group B. Both teams were undefeated, having trounced the defending champ, Spain, and discarded Australia. Because of goal difference, Chile needed to win this final game in order to top the group; Holland needed only a draw. At a time when some teams were already being eliminated, these two were comfortable in knowing that they would both move on—still, there was much at stake in a seemingly inconsequential game. Assuming Brazil were to beat Cameroon in the later game—as they ended up doing—the runner-up of Group B would play Brazil in the next game, and afterward the loser would have to go home. Brazil has hardly been sharp thus far, but if you can avoid playing Brazil in Brazil, especially in an all-or-nothing game, you’d better do it. But what if Brazil hadn’t won? Or what if Mexico—for my money the best team of the tournament thus far—had absolutely routed Croatia, overtaking Brazil in Group A on goal difference? (This nearly happened.) Then the team that won Group B, rather than the runner-up, would’ve had the distinct nonpleasure of playing Brazil. In other words: everything was in the air. It was time to be flexible.

Forty minutes into the game, Holland, a team that revolutionized the passing game and player movement, had completed forty-seven passes. By halftime, the Dutch playmaker Wesley Sneijder had completed two passes. To put these two numbers into perspective … well, there is no putting these numbers into perspective.

Holland has, since 1974’s “Clockwork Oranje” team, led by Johan Cruyff, been the symbol of offensive football; that team, and the great Ajax teams of the midseventies, were the great global ambassadors of an offensive 4-3-3 formation. Those teams were coached by Rinus Michels. Michels, Cruyff, and Johan Neeskens then went together to Barcelona; Cruyff ended up coaching Ajax and Barcelona. To this day, both Ajax and Barcelona play 4-3-3. Doing otherwise is taken as a great affront; when a coach does that, however rarely, his days are often numbered.

But in the case of the Dutch National team, there are exceptions. One would be France ’98, when Guus Hiddink deployed a 4-4-2—four defenders, a midfield diamond, and staggered forwards—and the occasional 4-5-1 to great effect. Another would be now, with Louis van Gaal, whose tactical decisions have been more fluid and unpredictable. Holland debuted against Spain with a 5-3-2—that’s five defenders for a team famous for attacking.

As you know by now, Holland scored five goals in the span of forty-five second-half minutes. Spain didn’t know what hit them. In their next game against Australia, Holland again played 5-3-2. Australia had clearly studied the formation, and consequently Holland sputtered through the first half. In the second, they switched to the tried-and-true 4-3-3 and put the sword to the team from Down Under.

Now, against Chile, with everything and nothing to play for, more changes were afoot. Holland had to make due without one of their star strikers, Robin van Persie, who’s been suspended. Instead of making a like-for-like switch and simply replacing van Persie with another forward, they changed the entire formation, playing a 4-2-2-2 and subbing another forward, Dirk Kuyt. But they were playing him as a carrilero—a wide player who defends and attacks equally along a specific sideline—out on the left. Kuyt is right footed. The stratagem was effective: Chile hardly had a shot on goal. But the South American commentators were appalled. How could Holland just throw away their tradition? Holland should always want the ball. That’s the legacy of the orange shirt. And here they were just letting Chile have the ball to themselves.

Although Chile seemed a shade of the side that had been so spectacular during their first two games, a Chilean broadcaster in the booth, Luis Omar Tapia, paid the team a telling compliment amid the general distaste that was being expressed of Dutch side before them. To paraphrase, he said it was lovely to watch this Chile, as they were designed first and foremost to recuperate the ball, to take it from the opposition—most teams now, he said, didn’t emphasize this trait, and it was beautiful to see Chile do so. It was telling, but not in the way he intended: he’d implied that van Gaal’s tactics were working on the pitch. Chile, to be effective, needed the opposition to have—or at least desire to have—the ball. Instead, Holland left Chile increasingly toothless with the ball. Holland’s second goal came on a corner kick—taken by Chile.

By the end of the game, Holland had won 2-0; once again, their best players had been expressive and decisive, and even the most romantic devotee of 4-3-3 could see the point. Van Gaal’s Holland will not here be burdened by its history, but will change as needed, even if they risk looking unattractive for large parts of a game.

Holland wore blue for their first two games. Those deep blue shirts seemed fitting during those moments, as this was not a Holland that looked like it could live up to the history of that famous “oranje” shirt. I closed my eyes for a while during that game, too. And often when I close my eyes, a color wheel appears, floating there in the black, neither near nor far nor bright nor dark; the primary colors are there, but so are their complementary colors. Yellow has its violet, red has its green, and blue has it orange. Blue is the opposite of orange. Statement made.

And yet things are never so simple. Against Chile, Holland came out in all orange. Yes, all orange, but from head to toe: no black shorts, no white shorts. It was orange overkill, as if to give those who wanted a vision of the past an unbearable dose of it. As if to say: here is your history, here is your orange, here is your oranje. Orange or oranje? Orange is the new oranje.

Rowan Ricardo Phillips’s second book of poems, Heaven, will be published next year. He is the recipient of the 2013 PEN/Joyce Osterweil Award and a 2013 Whiting Writers’ Award.

Mad with Desire (Kind Of)

The peculiarly virginal hero of Orlando innamorato and Orlando furioso.

From Gustave Doré’s illustrated Orlando furioso.

Love stories center on a problem—two people love each other, or one person loves another, and how are they going to get together? Sex is part of the solution, or usually is. There are, in literature, those strange cases where it isn’t.

In the literature of antiquity, sex is almost a last resort for the expression of love, and it seldom ends well. It’s the classic pitfall of the Old Testament. The transformations that compose the Metamorphoses are often brought about by sexual peril: Daphne turns into a tree to avoid having sex with Apollo. Syrinx turns into marsh reeds to escape pursuit by Pan. Io is turned into a cow as a bizarre result of having been raped by Zeus. Actaeon, the hunter, is famously turned into one of the very stags he hunts as punishment for seeing Diana naked, and is torn apart by his own dogs. The beautiful youth Hermaphroditus is so repulsed by the idea of erotic contact with a female nymph; she, obsessed, tries to take him by force. She wraps herself around him as he fights her off and prays to the gods to join them as one. And so one they become: a single two-sexed being.

In the realm of myth, sex is transformation, metaphor. Later on, in Arthurian and Carolingian romances, it is the concept of virginity that transforms—and not women’s virginity, but men’s. For the knights of Arthur’s Round Table, undistracted by any real political conflict during the reign of peace, the pursuit of God in grail form is the definitive test of purity. Only the virginal knight Galahad can see the Holy Grail, because of his virginity. “I never felt the kiss of love, / Nor maiden’s hand in mine,” Tennyson has him admit.

Galahad finds his Carolingian counterpart in Orlando, the idealistic, probably virginal hero in the Matter of France. The fifteenth century’s Orlando furioso (and its less-read predecessor, Orlando innamorato) revolves around the physical manifestation of Arthurian religious idealism: the religious wars between the Christian and Islamic worlds. Both stories concern Orlando’s doomed pursuit of the seemingly nondenominational Angelica, a woman whose sexuality is so potent that to escape pursuit by nearly everyone she meets, she must turn invisible by the use of a magic ring not unlike Tolkien’s. She is much closer to the template Ovid lays out in Metamorphoses, the stalked female relying on bodily transformation to escape abuse, though she is, ostensibly, the villain of the tale.

The Orlando cycle may be, in fact, the epic text most densely populated with imperiled virgins since the Metamorphoses itself. The characters themselves seem aware of this, often quoting Ovid to one another and identifying themselves in the very changeable positions of hunter and hunted. In Orlando innamorato, written by the Italian Matteo Boiardo in the 1470s, Orlando meets Angelica when she appears out of nowhere, like the White Hart in Gawaine’s tale, to offer a challenge to Charlemagne’s knights. She is later claimed, imprisoned, and manages to escape, while Orlando drops everything to pursue her across the war-scarred Franco-Christian empire. He catches up with her a few times, only to lose her again. In Orlando furioso, the pursuit finally drives him mad. Sex may well be a transformative act for others, but abstention is the thing that changes Orlando, bodily, elementally.

Perhaps this is why the Italians of this age talk of love in the ambiguous terms of fire—specifically “burning.” Lust burns, but the word also seems to foreshadow the lover’s fate, projecting a scene of later torment. One of Michelangelo’s most famous sonnets ends on the contradiction, “When near you burn me, when far off, you kill.” To burn is his fate: with passion, while on Earth, and presumably in hell later on. Michelangelo actually blames God, putting him at fault for making his creation so brittle and weak, in spirit as well as body, and for making us too passionate. “He is to blame,” he says, “who fashioned me for fire.”

But in the Orlando cycle, God’s role—as a character absent from the many myths springing up around his own legend; in the motivations, actions, and day-to-day lives of even his most devout subjects—appears questionable. There is, primarily, the case of the warrior Orlando’s love-driven treason, on which he reflects:

But in the Orlando cycle, God’s role—as a character absent from the many myths springing up around his own legend; in the motivations, actions, and day-to-day lives of even his most devout subjects—appears questionable. There is, primarily, the case of the warrior Orlando’s love-driven treason, on which he reflects:

Love, which burns my heart, makes this wind, beating his wings about the flames. By what miracle, Love, do you keep my heart ever burning but never consumed by fire?

This burning will lead him to forsake everything for her and remain, somehow, a good and chaste Christian by the standards of the poets who speak of him. Angelica’s effect on others is attributed to something more pagan, like witchcraft. When Charlemagne’s court catches sight of her for the first time, “All the barons, / And King Charles were in love. They blazed.”

Boiardo, Orlando innamorato’s author, died in 1494 without finishing the story. Ludovico Ariosto took up the reins a few decades later, first publishing Orlando furioso in 1516. The sequel is stranger, and better remembered as a sort of parody of the first, with the author infusing the farcical elements of the legend with his own voice and a strong underlying feminism.

Orlando furioso is a bizarre, idiosyncratic, cynical story—not one that has inspired a lot of great criticism, though it apparently influenced Shakespeare’s Much Ado About Nothing and Spenser’s The Fairie Queene. (There was also a famous stage production in the seventies involving gigantic puppets.) It is, in its way, a cult epic: bloody, mean, and very clear-eyed about love. There aren’t really any ideal couples or pure knights, and there is no Holy Grail. People fall in love mostly by trickery. Orlando never “wins” Angelica, and he doesn’t seem to understand what would happen if he did. The most interesting coupling, between the Christian Bradamante and the Saracen Ruggiero, is politicized: she forces him to convert before marrying him. Perhaps its part of the secret criticism of religion underlying it—a cult that claims to love its subjects but also calls them imperfect, calls upon them to change in impossible ways.

At the very least, the Orlando cycle draws these kinds of parallels between the twin cults of love and religion. While the already vague concepts of religious fidelity and personal honor fade into the background, so, too, do the even vaguer motives of love and sex. Though the effect of Angelica’s sexuality on others is the impetus for the entire story, it is also, in the case of Orlando, nearly irrelevant. The story seems to hinge less on his treasonous pursuit of a woman than on his chastity, disputed though it is.

Orlando’s sexuality is distinct from the outset. Married and yet apparently chaste—whatever that word actually means in the context of these tales—he forsakes his loyalty to his country, his wife, and his religious beliefs for a woman he can’t even get it up for. At one point in Orlando innamorato, Angelica greets him by drawing him a bath, before which she massages him, presumably naked, causing him to feel “tremendous joy, although / no part of him was seen to grow.”

Orlando’s sexuality is distinct from the outset. Married and yet apparently chaste—whatever that word actually means in the context of these tales—he forsakes his loyalty to his country, his wife, and his religious beliefs for a woman he can’t even get it up for. At one point in Orlando innamorato, Angelica greets him by drawing him a bath, before which she massages him, presumably naked, causing him to feel “tremendous joy, although / no part of him was seen to grow.”

He later fears that his rival for her love will get the best of him, for said rival “knows the tricks of flattery,” whereas

If I disturbed a single hair

on any woman’s head, I’d swoon.

I’d not know how to end or start,

unless she taught me, lent me heart.

Boiardo’s narrator comments upon Orlando’s haplessness in love, describing him as someone who “speaks of love like one who dreams,” and later lamenting, “O how much better fit to fight / than love a girl was that great knight!”

When it comes to his sexual intactness, he goes back and forth. Boiardo’s narrator questions the reliability of his source for the story, Turpin, an archbishop of Rheims. When explaining that Orlando has “no taste” for sex, he notes:

Turpino says the Count of Blaye

was chaste, a virgin, his life long.

You may believe what pleases you.

Turpin says lots of thing, some wrong.

And later, when Orlando is briefly reunited with Angelica:

He rode along and talked with her

but never dared to touch the girl.

He loves that lady so much that

he worried he might anger her.

Turpino never lies! He calls

the baron a baboon for this.

Of course, Boiardo clumps consensual and nonconsensual sex together as one act, assuming that a lack of interest in one is as good as a lack of interest in the other. It would be possible to think of Orlando as a person who is simply not turned on by a lack of consent were it not for the incident of the sexual massage, the bath, and the limp dick.

Of course, Boiardo clumps consensual and nonconsensual sex together as one act, assuming that a lack of interest in one is as good as a lack of interest in the other. It would be possible to think of Orlando as a person who is simply not turned on by a lack of consent were it not for the incident of the sexual massage, the bath, and the limp dick.

The question of his chastity gives a more complex shade to his eventual madness, which results from his discovery, in Orlando furioso, that Angelica has fallen in love and run away with someone else, and is, importantly, no longer a virgin—that she has, in a sense, left him behind. The course his madness takes is bloody and extreme, and more closely resembles the obsessive, physical response of sexual denial. This is what Balzac talks about when he refers to the eponymous Cousin Bette as having a sort of virgin energy, an untapped and seemingly inexhaustible resource that makes her able to single-mindedly exact her revenge. “Life,” he writes,

when its forces are economized, takes on a quality of resistance and of incalculable endurance in the virgin nature. The brain is enriched in its entirety by the reserve forces of its faculties. When chaste persons need to use their bodies or their souls, whether they are called upon for thought or action, they are conscious of a spring in their muscles, a knowledge infused into their intellects, a demoniacal power—the black magic of Will.

Victor Hugo’s Jean Valjean, while not overtly referred to as a virgin, is discussed in similar terms. He never had time for a lover, and so his outpouring of love for his charge, Cosette, becomes all the more extreme, confused, and violent. Obsession sets in, taking over logic as well as the body. Likewise, when Orlando loses his wits, he is at first immobilized:

Weary and heart-stricken, he dropped onto the grass and gazed mutely up at the sky. Thus he remained, without food or sleep while the sun three times rose and set. His bitter agony grew and grew until it drove him out of his mind. On the fourth day, worked into a great frenzy, he stripped off his armour and chain mail …

Then he tore off all his clothes and exposed his hairy belly and all his chest and back.

Now began the great madness, so horrifying that none will ever know a worse instance.

From here he goes on a killing spree, destroying all the sheep, trees, and humans who are unlucky enough to cross his path. His compatriots go to the moon, literally, to recover his sanity, there finding a glass case with Orlando’s “wits” cooling inside. He must be pinned down and made to inhale the contents of the vial in order to be restored to himself. When he recovers, he is not only sane, but cured of love.

From here he goes on a killing spree, destroying all the sheep, trees, and humans who are unlucky enough to cross his path. His compatriots go to the moon, literally, to recover his sanity, there finding a glass case with Orlando’s “wits” cooling inside. He must be pinned down and made to inhale the contents of the vial in order to be restored to himself. When he recovers, he is not only sane, but cured of love.

One wonders what happens to the less fortunate in Ariosto’s world, those who suffer from the same insanity but who lack friends to hold them down and force them to snort their own brains. Presumably they go on forever suffering, at least until they find an enchanted stream or magic spell that is the antidote.

In the end, Orlando’s story falls down on the side of love as bewitchment. Love is a kingdom, its authors say, absolutely unaffected by God’s otherwise despotic rule. It’s one of the most interesting assertions that two separate and deeply Catholic writers can make in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries—though it’s also, in its way, one of the most ordinary.

Henry Giardina is a writer living in London.

How Your Gender Affects Your Vocabulary, and Other News

Hans Thoma, Adam and Eve, 1897.

George Saunders talks “about his family’s sense of humor, the connection between satire and compassion, his early comedy influences, and how he came to embrace the funny side of his writing.”

Some words that men are likelier to know than women: claymore, scimitar, solenoid, dreadnaught. Some words that women are likelier to know than men: taffeta, flouncing, bodice, progesterone. The conclusions are yours to draw.

“I Was a Digital Best Seller”—the horrifying true story!

It sounds like a spinoff of DeLillo’s The Names: a journalist named Rose Eveleth becomes obsessed with a small town that shares her name: Eveleth, Minnesota. She visits it only using Google Street View.

Spending time with Prince at a listening party for his new record: “When you arrive at Paisley Park, you switch to Prince time. After nearly an hour’s wait, I was ushered into Studio B [at] about one a.m. … My next two hours at Paisley Park would be filled with funk, frustration, and funny lines—all courtesy of Prince.”

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers