The Paris Review's Blog, page 694

June 15, 2014

“Mum and the Sothsegger”

Game of Thrones and medieval poetry.

An illustration of apiaries from the Tacuinum Sanitatis, fourteenth century.

Game of Thrones, of which the season finale is tonight, is the rare show that affords Middle English enthusiasts a chance to geek out: the series makes many nods to medieval literature. Scholars have noted that it draws on the themes and features of such canonical medieval works as the Canterbury Tales and Beowulf. But as I watch, I’m reminded of another, more obscure work from the period, the fifteenth-century dream-vision poem “Mum and the Sothsegger,” which bears a number of striking parallels to Game of Thrones.

“Mum” is a strange, alliterative work about gossip and government and bees (yes, bees). No one is sure who wrote it, and its beginning and end are missing, which only adds to the mystery surrounding its composition. The poem essentially investigates whether it’s better to stay mum or to speak the truth; the titular Mum and Sothsegger personify the two sides of the debate. The work is a product of Lancastrian England, a time when—after Henry IV had overthrown and executed Richard II to become king—the royal court used severe censorship to quell dissent. Measures like the Arundel Constitution of 1409 meant you could be burned at the stake for expressing any vaguely defined “heretical” beliefs. In light of its historical moment, “Mum” is most convincingly read as a poem about succession anxiety and managing dissent. The poem is interested in the same questions of political philosophy that drive GoT, trying to work out how a person should be and how the state should comport itself toward its citizens.

Henry IV’s status as a usurper, much like Robert Baratheon’s after the overthrow of the Mad King in Thrones, sets a possible precedent for overthrow, raising the question of whether the old rules of succession still apply. In the face of brute force, lineage and birthright appear to be irrelevant—now if you kill the king, you are the king. In “Mum,” the anonymous poet walks a fine line in bringing the justness of Henry’s rule into question. He couches backhanded compliments in what appear to be lavish bouts of praise for the new king. He lauds Henry for being “witte and wise” and “cunnyng of werre,” but the passage is incendiary by dint of what’s left out—there’s no mention of lineage (the defining kingly quality), because the king has none. Henry is characterized as a “doer in deedes of armes”: seemingly a compliment to his battle skills, but also a way of carefully underscoring the violent means by which he took the throne.

In working within the restriction of expression under Lancastrian rule, the poem reveals a currency of information in which careful calculation is used to determine how much it’s safe to say. In this system, keeping mum is a form of greed, in which secrets become a form of wealth and information is hoarded until the right moment, when it can be cashed in for maximum value. The figure of Mum embodies the idea of ars tacendi, or the art of being quiet, art being the key word here—anyone can be quiet, but it’s an art to overhear the right stuff and keep strategically quiet. Mum is a yes-man, an apparent friend, a seductive confidant, who sits on secrets “forto wynne silver” (and other kinds of purchase).

Several of GoT’s characters have similar ambitions. Think of Margaery Tyrell, the eunuch Lord Varys, and the brothel-owner-gone-rogue Littlefinger, whom designations of gender, ethnicity, monetary wealth, status, etc. have excluded from other venues of power—they gain purchase in the Game through the expert collection and deployment of secrets. So when is it time to speak up? According to Mum, “He spendith no speche but spices hit make,” meaning don’t say a word unless you’re getting paid(in paprika, apparently). In line with this advice, Margaery, Varys, and Littlefinger often employ bribery and blackmail to leverage information as currency.

“Mum and the Sothsegger” presents Mum as the more persuasive option in terms of self-interest and self-preservation—but ultimately the poem redeems telling the truth as the moral high road. Sothsegger, Mum’s counterpoint, is depicted as an exalted gardener-beekeeper who offers the possibility of correction by speaking up. Even Mum admits, in his often contradictory speech:

For who hat knowlache of a cloude by cours abouve,

And wil stande stille til the storme falle

And wende not of the waye, and the wite is his owen.

If you see the storm clouds and you don’t find shelter, it’s your own fault. Still, telling the truth can be a dangerous path in a society that places a high value on discretion. A beekeeper runs the risk of getting stung. There’s no clear earthly reward, and the risk of punishment is high.

Ned Stark can be seen as a kind of Sothsegger figure in GoT. He refuses to keep his mouth shut and pursues the truth for what he perceives to be the good of the realm—this concern for “the realm” in Westeros mirrors the idea of the “common profit” that appears throughout medieval literature. For his commitment to the truth and his refusal to shut up about the illegitimacy of Joffrey’s reign, Ned Stark pays with his head. Likewise, the Sothsegger mentality prevails when Robb Stark insists on having the truth of his relationship with Talisa out in the open, despite her low status and the clear betrayal of the contract with House Frey; and more recently, when Prince Oberyn commits himself to extracting the truth of his sister’s rape and murder from the Mountain, which proves to be his downfall.

In the dream-vision segment of the poem, the narrator falls asleep and finds himself in a garden with a hive full of busy bees. Here the truth-telling beekeeper gives the poem its own “winter is coming” moment as he explains the bees’ workmanship:

“The bees been so bisi,” cothe he, “aboute comune profit,

And tendeth al to travail while the tyme dureth

Of the somer saison and of the swete floures;

Thayr wittes been in wirching and in no wile elles

Forto waite any waste til winter approche,

That licour thaym lacke thair lyfe to susteyne.”

The bees and the hive serve as metaphors for the ideal citizen and the ideal state, with winter as the catchall term for times of war, famine, and lack. The surplus of honey is viewed in terms of future shortage, squirreled away as a life-sustaining “licour.” Like the Starks of Winterfell, the bees live in a state of constant vigilance, held to the grindstone by the knowledge that “winter approche.”

In its criticism of Henry and the hypocrisies of the nobility, “Mum and the Sothsegger” is pretty radical for the conservative poetry of its time, but its radicalism is tempered by its formal aspects. The poem is an act of dissent in a repressed climate—it’s full of feints and winks and knowing indirection. And so, in its way, is Game of Thrones: it pays homage to the medieval literary tradition by adopting this model of intentional fakeness, couching its tale in the fictional realm of Westeros, not to dodge persecution for heresy but to evoke the universal. In its fabricated familiarity, Westeros comments on the broader philosophical questions of citizen and state, which remain pertinent as ever.

The full text of Mum and the Sothsegger is available through the University of Rochester. Here are its first twenty lines:

Hough the coroune moste be kepte fro covetous peuple

Al hoole in his hande and at his heeste eke,

That every knotte of the coroune close with other,

And not departid for prayer ne profit of grete,

Leste uncunnyng come yn and caste up the halter

And crie on your cunseil for coigne that ye lacke,

For thay shal smaicche of the smoke and smerte thereafter

Whenne collectours comen to caicche what thay habben.

And though your tresorier be trewe and tymbre not to high,

Hit wil be nere the worse atte wyke-is ende,

For two yere a tresorier twenty wyntre aftre

May lyve a lordis life, as leued men tellen.

Now your chanchellier that chief is to chaste the peuple

With conscience of your cunseil that the coroune kepith,

And alle the scribes and clercz that to the court longen,

Bothe justice and juges yjoyned and other,

Sergeantz that serven for soulde atte barre,

And the prentys of court, prisist of alle,

Loke ye reeche not of the riche and rewe on the poure

That for faute of your fees fallen in thaire pleyntes.

Chantal McStay studies English at Columbia University and is an intern at The Paris Review.

June 13, 2014

What We’re Loving: Pop Stars, Rock Stars, The Fault in Our Stars

The Fault in Our Stars—now a major motion picture.

Last week I read a dazzling novel about a starcrossed young couple and a reclusive, grouchy, alcoholic novelist who changes their lives. That was Mao II, by Don DeLillo. But in the middle of reading Mao II—on the very same plane ride—I dipped into a friend’s copy of The Fault in Our Stars. Somehow I had missed all the hype, and didn’t know what to expect. (Said my traveling companion: “You’re already crying? You’re what, two pages in?") I finished the book one sitting later. More accurately, I was lying down, in a hammock, to obviate the need for a hanky. Among its many tear-jerking qualities, the book powerfully evokes the work of David Foster Wallace, the only real-life novelist who could fill the shoes of the fictional Van Houten. As Laura Miller writes in Salon, “The Fault in Our Stars is full of Wallace allusions; scenes like the one where a teenager sobs over his girlfriend, while playing a first-person shooter game, read like Wallace come back to life—if he came back and wrote for kids. In a week that saw the passing of the great children’s-book publisher Frances Foster, The Fault in Our Stars filled me with hope for young readers, even as it made me mourn, all over again, for friends we’ve lost. —Lorin Stein

Britney Spears must be some kind of a journalistic muse. In 2008, David Samuels wrote about her in “Shooting Britney,” a perceptive look at the paparazzi and the surrogate intimacy of celebrity culture. Now, in “Miss American Dream,” Taffy Brodesser-Akner—what a name!—pulls back the curtain on Britney’s new residency in Las Vegas. The piece gets inside the lurid pageantry that’s become a prerequisite of “Britneyplex, which is the enormous machine built around Britney Spears.” It’s also an acutely observed study of the longueurs of fame; moments of synapse-frying overstimulation are followed by episodes of surreal blandness. E.g.: “She was sitting in a room in the semi-dark, slightly hunched over, a little bored, at the tail end of a daylong junket in which TV journalists asked her questions like ‘What do people not know about you?’ (‘Really that I’m pretty boring.’) and ‘What was the craziest rumor you ever heard about yourself?’ (‘That I died.’)” —Dan Piepenbring

One of these days, U2 is going to release a new album—in the meantime, there’s U Talkin’ U2 to Me?, a bizarrely wonderful podcast I’ve laughed out loud to on the subway. Described by its hosts (Scott Aukerman of Comedy Bang! Bang! and Between Two Ferns, and Adam Scott from Parks & Recreation) as “the comprehensive and encyclopedic compendium of all things U2,” the show talks about U2 pretty sporadically, but it’s worth checking out for the improvisations from the two Scotts, including a hysterical Harold-like game in which they make up fake podcasts within the world of the show, each with its own fictional history and quirks. This week’s episode takes the form of an audio commentary on the podcast itself. It’s even weirder than that sounds. —Chantal McStay

A recent article in the Huffington Post suggests reading Rumi for a more meaningful life—advice I found both unsurprising and unnerving. I come from a Persian household where Rumi’s poetry was always at the literary forefront, but in more recent years, the poet’s words have been reduced to captioning photos of perfectly timed sunsets and vast ocean views. I prefer the darker Rumi, even if a line like “Either give me more wine or leave me alone” isn’t likely to inspire enthusiasm. Rumi’s work is much too varied to be reduced. “Two there are who are never satisfied—the lover of the world and the lover of knowledge,” he wrote. That a poet from the thirteenth century is still so widely read testifies to his intuition and candor. —Yasmin Roshanian

Medical Literature

A portrait of Frances d'Arblay (”Fanny Burney“) by Edward Francisco Burney, ca. 1785.

Today marks the birthday of the English novelist and playwright Fanny Burney, born in 1752, whose Evelina, Cecilia, Camilla, and The Wanderer were all major sensations in her day. Hers were satirical novels—often now called proto-Austenian—which were highly regarded by contemporary critics as well as readers.

Burney wrote one of the earliest accounts of a mastectomy—her own—which she was, horrifyingly, awake enough to observe. The operation was performed by “7 men in black, Dr. Larrey, M. Dubois, Dr. Moreau, Dr. Aumont, Dr. Ribe, & a pupil of Dr. Larrey, & another of M. Dubois”—the latter of whom was considered the number-one doctor in France. Warning: the account, taken from a letter to her sister, gets a little gory, so it’s not for the faint of heart. But Burney did survive, until 1840, at least. Of course, we can't be sure she really had cancer: she had pains in her breast, but in the absence of a biopsy, it’s hard to know.

I mounted, therefore, unbidden, the Bed stead—& M. Dubois placed me upon the Mattress, & spread a cambric handkerchief upon my face. It was transparent, however, & I saw, through it, that the Bed stead was instantly surrounded by the 7 men & my nurse. I refused to be held; but when, Bright through the cambric, I saw the glitter of polished Steel—I closed my Eyes. I would not trust to convulsive fear the sight of the terrible incision. Yet— when the dreadful steel was plunged into the breast—cutting through veins—arteries—flesh—nerves—I needed no injunctions not to restrain my cries. I began a scream that lasted unintermittingly during the whole time of the incision—& I almost marvel that it rings not in my Ears still, so excruciating was the agony. When the wound was made, & the instrument was withdrawn, the pain seemed undiminished, for the air that suddenly rushed into those delicate parts felt like a mass of minute but sharp & forked poniards, that were tearing the edges of the wound. I concluded the operation was over—Oh no! presently the terrible cutting was renewed—& worse than ever, to separate the bottom, the foundation of this dreadful gland from the parts to which it adhered—Again all description would be baffled—yet again all was not over,—Dr. Larry rested but his own hand, & — Oh heaven!—I then felt the knife (rack)ling against the breast bone—scraping it!

Out of Joint

The opening ceremony; Brazil and Croatia.

When I switched on last night’s World Cup opening ceremony, it first appeared that some São Paulo carnivalesque version of Macbeth was in production and Birnam wood was on its way to Dunsinane. A number of figures masquerading as trees were making their way around the field shaking their branches and twigs. But soon the trees had exotic birds for companions and then some children in white bounced on a trampoline while mechanical leaves unfolded and, of course, we were not in Scotland but a virtual rainforest, where the uncontacted tribe appeared to consist only of JLo, Pitbull, and Claudia Leitte. Luckily for them, the Amazonian jungle on display was the Disneyfied version, significantly denatured: there were no carnivorous plants in evidence or shamelessly sexual banana fronds. Two years ago, scientists discovered in a Brazilian river a new species of blind snake that looks like a penis. I do not believe it was represented during the opening ceremony. The tribe of three sang “We Are One (Ole Ola),” plucked from the Songbook of Truly Awful Tunes Written for Grand Occasions. The message held up until the twenty-sixth minute of the game that followed, between Brazil and Croatia, when Neymar received the tournament’s first yellow card for slamming his forearm into Luka Modrić’s throat.

We all know that Nature, even when significantly denatured, abhors a vacuum—so as soon as the rainforest had left the field, on came the teams. The Brazilians walked out with their right arms extended on to the right shoulder of the player in front, as if only their leader could see.

Not seeing, as it turned out, was a theme of the game. The Japanese referee Yuichi Nishimura, for example, failed to see that the Brazilian striker Fred had not been fouled by Dejan Lovren, which led to Neymar converting the game-winning penalty. Nor did the ref see that Julio Cesar, Brazil’s goalkeeper, had also not been fouled when Perisic had a goal disallowed. Or that Oscar’s clinching third goal came after Rakitic had been blatantly fouled.

Call me Croatian, but that’s the way it was. What everybody saw was Croatia’s first goal, which could not be in doubt, as it was scored by a Brazilian when Marcelo inadvertently directed the ball past his own goalkeeper and into the back of the net. In case there was any uncertainty, the TV feed bizarrely decided at this point to employ its spanking new goal-line technology and show us the ball crossing the line and rolling slowly … to the back of the net.

It has been clear for some time that we are in the service of the robot and not the other way round, but more and more it is becoming evident that we cannot trust ourselves to discern anything.

Neymar, who came close to receiving a red card for his felling of Modric—can you really give a red card to the most popular player in the host country before the first game is three-quarters over?—showed that he is a talented and lovely player, and he scored two goals. Yet his team, so far, only looks good, not great.

Pascal once remarked, “If Cleopatra’s nose had been out of joint the history of the world would have changed.” And so it is with the whistles of referees and the history of World Cups.

Jonathan Wilson’s work has appeared in The New Yorker, Esquire, The New York Times Magazine, and Best American Short Stories, among other publications. He is the author of eight books, including Kick and Run: Memoir with Soccer Ball. He lives in Massachusetts.

Bloomsday Explained

Djuna Barnes, Joyce, 1922.

“Bloomsday,” the James Joyce scholar Robert Nicholson once quipped, “has as much to do with Joyce as Christmas has to do with Jesus.” The celebrations of Ulysses every June 16—the date on which the novel is set—attract extreme ends of the spectrum of literary enthusiasm. Academics and professionals mingle with obsessives and cranks, plus those simply along for the ride. The event can be stately and meticulous or raucous and chaotic—or, somehow, all of the above.

A telling instance came a few years ago, when the Irish Arts Center arranged a Bloomsday picnic in New York’s Bryant Park, under the rueful shadow of the Gertrude Stein statue. (Stein disliked Joyce.) Aspiring Broadway types were enlisted to circulate in period costume before bursting into popular songs from 1900-era Ireland. I spoke to one of the performers, a young Irish actor who had recently moved to New York. Had she read Ulysses? “I plan to,” she said, and in my memory, she adds, “I’m told it’s a grand book by them that knows.” The kicker was when the Irish finance minister, in town for summit meetings, got up to say that his government would take as inspiration the balanced daily budget that appears in Ulysses. The problem? Leopold Bloom’s spreadsheet in Ulysses works out only because he omits the money he’s paid to Bella Cohen’s brothel. No one pointed out the irony.

The admixture of expertise and fanboyism that marks Bloomsday, perhaps unique among literary gatherings, is remarkable—but no more so than Bloomsday’s emergence as a cultural event, one that attracts mainstream attention and participants from well outside the readership of Ulysses, by which I mean to include all those who profess to have read it. A novel written in 1922 and legally unavailable in the U.S. until 1934, a novel hailed to this day as the pinnacle of modernist obscurity and density, one that, as novelist Jacob M. Appel recently put it, “isn’t exactly hopping off the shelves in airports,” has earned an international holiday. Of all the literary celebrations that might blow up, why Joyce, why Ulysses, and why Bloomsday?

The answer lies in the celebrity and cultural capital of the Joyce brand, the result of Joyce’s machinations and the way he’s been taken up in mainstream U.S. culture. When Joyce started work on Ulysses a hundred years ago, he was a rather cultish figure, having recently published A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man and Dubliners, after many roadblocks for both. This limited but fervid devotion played into Joyce’s career: through the efforts of Ezra Pound, Ulysses and its author became something of a cause célèbre for modernist coteries. Pound secured Joyce patronage (largely from women—Joyce’s career is unthinkable without the interventions of Harriet Shaw Weaver, among others), enabling him to leave off teaching to write (the dream of many). A series of public legal incidents catapulted the novel into wider public consciousness: the seizure of copies of The Little Review that contained the “Nausikaaa” chapter, Joyce’s campaign to prevent Samuel Roth from selling a pirated edition, and the 1933 case “The United States of America v. One Book Called ‘Ulysses,’” in which Judge John Woolsey determined that Ulysses was art, not smut. In the 1930s, Joyce appeared on the cover of Time and Stalin’s list of banned authors, and generally became famous as the epitome of literary difficulty and elitism.

Joyce, of course, was adept at cultivating his own myth, whether developing an iconic image for photographs or talking about his technique. Simply consider his decision to base a novel on the episodes of the Odyssey; then consider his bruiting that about. What better way, asked the late Hugh Kenner, to get your book discussed? Though Joyce maintained (disingenuously, in my mind) that anyone could read and enjoy Ulysses, he also quite famously said, “It will keep the professors busy for centuries arguing over what I meant, and that’s the only way of insuring one’s immortality.”

Indeed, the very style of Ulysses—or rather, its myriad styles—serves as a constant reminder of its author’s genius, asking readers to think beyond the plot and consider the motivations for each stylistic change. For example, in the novel’s sixth chapter, readers suddenly encounter new typography: boldface headers for sections of text, untraceable to any character thought. Why? Because the setting is a newspaper office, so there are headlines, dummy. Chapter 12 starts off with a first-person narrative “I,” the only chapter featuring this technique. Why? Because it is the chapter based on Homer’s Cyclops episode, and the “I” represents the single Cyclopian eye (and the limited perspective it produces). (Dummy.) The experience of reading Ulysses is partly the experience of deciphering such logic. While usually we read novels and keep track of what motivates characters, for Ulysses we keep track of the tricks up the author’s sleeve; we’re thinking about a figure outside the narrative.

Joyce’s contemporaries in the cinema world were doing something similar. When Charlie Chaplin performs circus acrobatics to the delight of the big-top crowds, the joke is only partly that the circus audience mistakenly thinks the Little Tramp is part of the show, a virtuoso, when in fact he’s trying to survive the situation. The larger joke is that we understand that the on-screen audience has almost gotten it right; the Tramp of the story is no virtuoso, but the actor portraying him is. Like Ulysses, the movie requires us to think beyond the fictional realm being represented to the genius in the real world.

The protean techniques in Ulysses mimic the operations of film stardom. Stylistic innovation is the central facet of the modernist legacy, signaled by Pound’s exhortation to “make it new.” In Ulysses, narrative style turns out to reflect techniques of the most popular medium of the day. Modernism and celebrity culture emerge as two sides of the same cultural coin. The popularity and the populist tinge of Bloomsday events start to look less surprising against this context.

Patrick Kavanagh and Anthony Cronin at the church in Monkstown, June 16, 1954. Photo: National Library of Ireland Commons

In the decade or so after Joyce’s death, in 1941, Bloomsday was instituted in Dublin; among the first participants were poet Patrick Kavanagh and novelist Flann O'Brien. The group role-played scenes of the novel. Around this time, references to Joyce began popping up in mainstream American culture, starting with Sunset Boulevard, with the novel usually deployed as a sign of elite literary culture and caché. Perhaps the most famous sighting is the iconic photograph of Marilyn Monroe brandishing Ulysses, attempting to shed her bombshell reputation. Of course, this image plays on our questions of whether the novel is readable and whether anyone, much less a Hollywood star, actually reads it. These questions permeate the Ulysses legacy, but the answers hardly matter to the culture at large. Yes, many people read Ulysses (as Monroe apparently did), but, as our Bloomsday celebrations show, one need not penetrate the mystery in order to recognize, and partake of, its prestige.

The highest-profile New York event on June 16 will be “Bloomsday on Broadway,” which is a hot ticket most years, simulcast on WNYC and heard around the world. At Symphony Space, actors, writers, and celebrities—Stephen Colbert and Alec Baldwin have appeared in recent years—will perform excerpts expertly. In between, commentators will celebrate Ulysses, but if this year is like years past, they will do so with testimonials and platitudes: elevation, not explication. If you have to ask, you’re missing the point, which is to recognize the stature of a book without necessarily comprehending it. All you need is to understand its un-understandability. This incomprehensibility, which everyone can understand (to paraphrase Stein) signals the way Joyce and his famous Ulysses mediate between literary modernism and modern celebrity culture and the attendant concerns of branding and iconicity. In this way, it turns out that Bloomsday has a great deal to do with Joyce; it may be that Santacon, not Christmas, is the most apt comparison.

Jonathan Goldman is an associate professor at the New York Institute of Technology, Manhattan. He is the author of The Modernist Author in the Age of Celebrity and coeditor of Modernist Star Maps: Celebrity, Modernity, Culture.

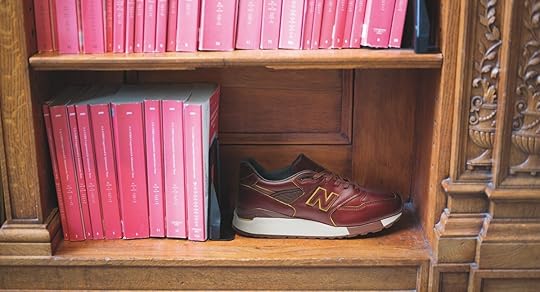

Literary Sneakers, and Other News

Because books and footwear belong together. Photo: Courtesy of New Balance

Donald Hall, who published poems in our first issue, has taken to the Concord Monitor to excoriate a senator in verse: “Get out of town, / You featherheaded carpetbagging Wall St. clown, / Scott Brown!”

Today in crass commodification: New Balance is releasing a series of shoes based on great American lit. “No one captures the essence, spirit, and the American experience better than American authors and the stories they have told throughout history. For the Made in USA Authors Collections, we pay homage to great American authors by building a collection inspired by their stories and moments.” The shoes are three hundred dollars a pair and “aren’t specifically tied to an author’s name.”

“The history of the professional executioner is a chronicle of perfecting the choreography of death. It’s a story of exacting skill and the never-ending search for a more efficient means to enact (and contain) the spectacle of death.”

Bob Silvers talks to The Guardian about the New York Review of Books, which is to be the subject of a new documentary by Martin Scorsese.

No plans this weekend? Paint your actuary! “It might seem strange that an artist would lavish such care on the nuts and bolts of something so mundane, like a poet writing couplets about a corporate expense report. But … accounting paintings were a significant genre in Dutch art.”

June 12, 2014

Taxonomy

Which is it?

I have a terrible feeling that the game “Animal, Vegetable, Mineral” is an endangered species. Granted, my evidence is strictly anecdotal—several kids I know had never heard of it—but this is nonetheless a cause for serious concern.

It’s not that I was ever so great at the game; on car trips, my heart always sank when anyone identified the category as “mineral” because my knowledge was so scant. And let’s face it, as guessing-games go, it’s a bit of a dud: with none of the urgency of Twenty Questions and none of the glamour of Six Degrees of Kevin Bacon, poor old Linnaeus can feel like a bore.

But I don’t think the game is in trouble just because it’s slow. The contemporary material world is complicated. Last night, I put myself to sleep going through the various objects in my bedroom and attempting to classify them. It did not go well; several times I had to cheat by looking up the component parts of my humidifier (mineral), the shell of generic ibuprofen (animal) and the filling of my knockoff Tempur-Pedic pillow (surprisingly, vegetal). Short of a degree in inorganic chemistry—or a bylaw prohibiting the inclusion of anything invented after, say, 1950—the game is nearly impossible. “Mineral ascendant,” I scrawled in my notebook.

In the 1950s British game show Animal, Vegetable, Mineral (the American version was called What in the World?), scholars attempted each week to identify various objects of historic interest. It’s a really good show—you can find full episodes online—reminiscent of Antiques Roadshow, but without the money. Even by mid-century BBC standards, though, it’s a strikingly unsexy title.

Perhaps the weirdest use of “animal, mineral, vegetable” comes to us via the musical Peter Pan. Peter (as played by Mary Martin) has disguised herself as a woman to somehow entice and distract the campy Captain Hook. Among other bizarre hijinks, they have a brief round of “Animal, Vegetable, Mineral.”

Just when you start to think it was a simpler time, you see something like this. And are reminded that, maybe, it was just weirder.

The Jimmy Winkfield Stakes

A racetrack in obsolescence.

Photo: Ilya Lipkin

Every year on the third Monday of January, the Aqueduct Racetrack, in South Ozone Park, Queens, runs a six-furlong race in honor of Jimmy Winkfield. The choice of date, Martin Luther King Day, is not accidental. Of Winkfield’s many accomplishments, which include winning the Russian Oaks an incredible five times for Czar Nicholas II, he is best known as the last black jockey to run a winner in the Kentucky Derby, in 1902.

To be black in the world of horse racing was no easy thing in the early part of the twentieth century. Winkfield, born in Kentucky, had enjoyed a storied career in Russia and France, but when he returned to America he was forced to enter a reception held in his honor through the hotel’s service entrance, with the bellhops and the kitchen staff.

Because of the raw January weather, attendance at the Jimmy Winkfield Stakes is usually rather sparse compared to the bigger events at the height of the racing season. This year, my older brother Ilya and I saw the race completely on a whim—we thought it might be fun to trek out to the Aqueduct like we used to when we were younger. Back then, if the weather was fine, our father would drive us to the track out in Ozone Park, a favorite destination for the unattached men in the neighborhood. Edik from the dry cleaners down the street was a fixture there, as was Pavel, the bartender at the Pennant Sports Bar on Northern, and Parsons, whose brother was an orderly at the elder-care facility where our grandfather died. To me, gaining admission to that world of working men was no less exciting than the races themselves. I watched with great interest as they quaffed beer and studied the odds on the board and cursed when they invariably lost their money. Being a bit older, Ilya had a better sense of what was actually going on. He nagged Pavel until the bartender showed him how to decipher the near-hieroglyphic racing form. The one time my father let him place a bet, we won eighty dollars. It proved to be a red-letter day, because that same afternoon, I fed a carrot to Cigar, the Hall of Fame thoroughbred, just before the first big win of his career. (The Aqueduct now runs a race in his honor as well.)

In the years since, we knew from the Post, Internet gambling had decimated the Aqueduct’s attendance numbers, and, fed up with the corruption and mismanagement of the New York Racing Association, politicians of both parties had promised to close it down. Still, I was chagrined to find the track’s once bustling lobby, which had always been the most thrilling place, completely empty except for a few gamblers who had arrived early to claim their carrels. Twenty years ago, Champs, the track bar, would have already been packed—my father always complained about having to wait thirty minutes for a glass of Old Milwaukee. Now the stools at the imitation brass rail stood patronless. Everywhere we went, we encountered an eerie silence. The nattering of the girls at the betting window and the swish of the janitor’s cloth as it passed over a plaster jockey were completely swallowed by the cavernous ceiling and cement walls. No effort had been made to update the decor or to effect even the most minor of repairs. The only thing that had not been there during our last visit was a red-and-blue sign painted onto the concrete that read UPDATE YOUR STATUS. Ilya waited with his camera until a gnarled man with a bulbous red nose passed underneath it before snapping a photo.

What little remained of the grandeur we recalled was most in evidence outside, on the building’s track side. There, a dozen or so spectators were watching one of the grooms walk a horse through the sandy loam, his flanks covered with a heavy tartan blanket against the cold. The sheer scale of the structure behind us, with its rows and rows of seats soaring up to a huge winged roof, lent dignity not only to the horses lining up for the first race but to the score or so of late-arriving men who began to trickle into the stands once the call to post rang out over the PA. It was hard not to be struck by the variety of faces filling up the seats. There were a few blue-eyed, straw-haired men who came, judging from their accents, from the drizzly lowlands of Northern Europe. Next to Ilya, a five-man delegation from the mountains of Peru was arguing heatedly over the odds printed in the racing form. Up by the rail, two Asian men in baggy denim and worn-out flannel passed a pair of binoculars back and forth. Anywhere except the Aqueduct these men would have cut a sorry figure; here, away from the judging of eyes of wives and children and police officers and family-court judges, they could at last lay claim to a measure of respect. Not only were they valued customers, they were experts, and with a bit of luck, they could be rich as well—a little rich, at any rate, if only for the afternoon.

* * *

The first race, six furlongs along the inner dirt track, was brief and unassuming. Starting near a copse of leafless trees at the far end of the track, the riders pulled toward the rail as they came around the bend, fanning back out as they came down the stretch. The silence in the stands was broken by a chorus of shouts—“Four! Four, five!”—directed at the high-definition monitor tracking the horses’ progress. When the dust had settled—figuratively speaking, since a light drizzle had turned the loam to muck—a dark brown colt called Green Gratto had taken first place, knocking the 3-1 favorite, Team Lazarus, out of the money. Some of the less fortunate gamblers elected to abuse themselves by watching Green Gratto and his owner have their picture taken by the boxes of chrysanthemums in the winner’s circle. Most of the crowd, however, quickly shook off the disappointment and filed back into the building to see the simulcast race at Sam Houston Park, leaving behind a small flurry of torn betting slips for the gulls to pick through. The scrawniest and most desperate of these animals tried to choke down loose bits of losing tickets. They began to take on the glum aspect of the men that had discarded them.

Inside, Ilya and I were joined by our long-time friend Chris Cumming. Like us, Chris had found himself drawn to the track over the years; in junior high, he and his father often went not only to the Aqueduct but also to Saratoga, up I-95. As a graduate student at UCLA, Chris observed the start and end of each semester by driving out to Santa Anita Park—with its expansive view of the San Gabriel Mountains, widely considered the most beautiful racetrack in the world. Chris made no pretense of being an expert when it came to horses, but I respected his opinion implicitly, so I asked him, once we had picked out two seats right by the finish line for the second race, whether it was possible to make real money at the track.

There were two prevailing opinions, he said. The first was that the races at every track—Aqueduct, Sam Houston, Santa Anita, Saratoga, whichever—were massively rigged. It was an outlook born of ressentiment, but it was confirmed by the testimony of dozens of jockeys, trainers, and organized criminals. (In the book Wiseguy, for example, the infamous gangster Henry Hill brags that he and his associates rigged so many races at the Aqueduct that the NYRA was forced to discontinue the Superfecta bet they had been using to maximize their profits.) The best that one could hope for then was that one’s interests did not run counter to the interests of whoever it was that controlled the outcome of each race—a pretty bleak hope, on the whole.

On the other hand, from what Chris had heard at Santa Anita, it was just as widely held that horses were nothing more than dice with legs, and that for all the information offered in the racing form—the horse’s parentage; his win rates on dirt, on grass, on turf; his jockey’s career record—there was no way, short of actually being able to see into the future, to predict any of the races. Each track offered the services of one or more handicappers, but they were no different from the hucksters he encountered on his beat as a financial reporter: the hedge funds that take a two-thousand-dollar commission and a twenty-percent performance fee for their worthless “management,” or the brokerages that win and lose fortunes throwing darts at the stock page of the Times.

Just then, Sol the Freud, the 5-2 favorite, charged passed us into first place, exactly as the handicapper predicted. Chris had bet him, it turned out; he shrugged and went to collect his pay out.

Photo: Ilya Lipkin

By two o’clock, the morning drizzle had thickened into a proper rain, so the three of us sought shelter in the Equestris Restaurant, the dining room for “high rollers” on the racetrack’s third floor. The moment we stepped inside, Ilya lit up. The restaurant’s elaborately folded cloth napkins, its potted fronds, and, above all, the artless reproduction of Géricault’s Riderless Races painted on the far wall could not have better suited his unfailing eye for the pathetic and the garish. While Chris and I split a turkey sandwich I had brought from home, Ilya criss-crossed the room, photographing everything from the scalloped ceiling to sea-foam green carpet—pausing, before each shot, to flash us a toothsome grin. Later, I read that, despite its chintzy trappings, the Equestris Restaurant was actually the largest restaurant in New York City when it opened in 1983 and that the gala was attended by quite a few celebrities, among them Warren Beatty, Andy Warhol, and even a twenty-four-year-old Michael Jackson, fresh from the success of Thriller. Glum as the dining room was now, thirty years had not dimmed that aura of exclusivity. Though the racetrack had no security guards to keep the rain-soaked gamblers out—indeed, judging by the omnipresence of malt liquor and the thick smell of marijuana indoors as well as out, the Aqueduct was rivaled only by the beach at Coney Island for lack of police presence—none of them ever ventured up into the restaurant. Besides us, the only other patrons were a white family from Long Island, quietly dividing a platter of lasagna served to them by a tuxedoed waiter with all the deference due a visiting head of state.

We watched the next races on the television installed at our table, a small white set nearly identical, I noticed, to the twelve-inch Mitsubishi Ilya and I had had in our bedroom growing up. It was amazing, Ilya said, just how boring horse racing was if you weren’t betting. The horses were practically indistinguishable; the commentary impossible to follow. And the snowy, soundless picture felt like a dispatch from purgatory, where, as punishment for a life of haste and inattention, some poor souls were doomed to ride and ride without ever getting anywhere.

Chris took a more sanguine view. Monotony, he said, was in the nature of every sport. One game always followed the next, season after season, year after year. No sooner had you won the Stanley Cup or the World Series than you were back where you started, 0-0. That was why he never understood fans who cried when their team lost or mailed death threats to a rival goalie. Nothing was permanent, neither victory nor defeat. The least you could say for the racetrack was that it was the one place in the world where a win was never celebrated and a loss was always suffered quietly. For all that, Chris conceded, it might make sense to leave a little early, as it was getting close to rush hour.

On our way out, we noticed that the crowd in the stands had nearly tripled while we were in the restaurant. The rain had let up, a few shafts of sunlight had broken through the low-hanging clouds, and nearly all sixty seats on the ground floor were taken. The crowd, it turned out, had gathered in anticipation of the final race of the day, the Jimmy Winkfield Stakes, though no one seemed to recognize it as such—they only called it “the race” or “the big one.” (“Who do you like for the big one?”) Our curiosity stoked, Chris and Ilya went to stake out seats, while I made my way over to the rail to stretch my legs. There, three squat men in FDNY caps carefully observed the warm-up of a fierce black colt on the inside dirt track. This was Charleymillionaire, and from their excited chatter, I gleaned that he was the favorite, and that the Jimmy Winkfield Stakes were expected to be the first big win in what was to be a distinguished career. It was not hard to see why the men were so impressed with him. Each step Charleymillionaire took made the ropy muscles bulge beneath his glossy coat. His tail swished back and forth furiously. Somewhere behind his eyes, it seemed like there must have dwelled an ancient memory of running unsaddled across a Spanish plain. When his jockey tugged at his reins, he gave an angry snort before complying.

I was just about to return to my seat, wondering how the other horses stood a chance against such a determined animal, when I caught notice of a chestnut gelding called Hot Heir Skier. A little smaller in stature than Charleymillionaire, he was doing a few light sprints right by the rail, taking no notice of the crowds or of the stands. (Between sprints, the other horses’ heads inevitably drifted toward the spectators.) He lifted one hoof and placed it down, and then another, and another, as serenely as the horses I had once seen on a drive to Vermont, with nothing to do but chew hay all day and watch cars zip by. His jockey hardly had to steer him—although, from time to time, he gave him a good thwack anyway. I’m the first to scoff when pet owners speak as if their dogs are human beings—and yet, as Hot Heir Skier came by the rail, swinging his head around ever so slightly, his shallow, button-like eyes were square with mine, and I looked at him, and he looked at me, and I was sure he was regarding me not just with animal curiosity but actually with pity—as though I were worse off than he for having no jockey to tell me where to go and how to get there.

I went to place a fifty-dollar bet on him, only to find the cashier shutting up as I reached the front of the line.

* * *

At first it seemed I had caught a lucky break. The moment the bell sounded, Charleymillionaire charged right out of the gate, leaving Hot Heir Skier boxed in at the rail by Otoy, a runty long shot. The colt’s tail whipped through the shower of dirt thrown up around him while the other horses trailed behind like guppies in the slipstream of a massive trout.

As the riders came around the bend, however, Otoy fell to the back of the bunch, giving Hot Heir Skier the room to glide out—still lifting one hoof serenely after another—in front of Oliver Zip. With the gelding hot on his heels, Charleymillionaire’s jockey began to whip him mercilessly, trying to preserve his lead. The more furiously he drove himself, he more and more he fell behind. Hot Heir Skier easily passed him in the home stretch, tossing his head with the same haughty unconcern he had showed me. Oliver Zip took second place, followed by Pax Orbis. He and Charleymillionaire finished so closely together that it took a photo review to establish that Charleymillionaire had finished out of the money. Had I successfully bet on Hot Heir Skier to win, I would have collected eight hundred dollars.

Chris and Ilya and I filed out with the rest of the crowd. Looking from face to face, all of them almost beatific in their expressionlessness, it seemed I was not the only person at the Aqueduct that day to receive an object lesson in stoicism.

Acceptance, of course, must go hand in hand with forgetfulness. Apart from a tiny notice in the racing form, no announcement had been made that the race just run was the Jimmy Winkfield Stakes—and apart from a display case in the lobby filled with dingy, fake-looking trophies, the only indication that there had even been races at the Aqueduct before that day was the Wood Memorial Wall. Here, in a lightless corner behind one of the staircases, four-by-six-inch photographs showing winners, jockeys, trainers, and owners were crowded floor to ceiling like the paintings in a French salon. Most of the gamblers at today’s race had, in all likelihood, seen some of these victories; still, not a single man stopped to pay his respects. One would think that a place so thoroughly relegated to the past might be more mindful of what has come before.

The death knell has already sounded for the Aqueduct—soon, not one, but seven casinos offering blackjack, poker, craps, and live entertainment will open all over New York State. Nostalgia comes with old age—why not look back? But to be of the past is not the same as to be in the past. A regular at the Aqueduct stands with one foot in a glum today and one in a sunny tomorrow. Today he doesn’t have two nickels to rub together; tomorrow, his horse has won by a nose, his pockets are full of money and his family has forgiven him for his failures as a husband and a father. Soon, he will be gone and the men beside him in the stands, men who can’t even recall the name of a horse that accomplished the astounding feat of winning the Triple Crown while undefeated, will hardly remember him who has done so little. It is a pleasant place, the Aqueduct. Go while it’s still standing.

Michael Lipkin is a student and writer living in New York City. His writing has appeared in n+1, The Nation, and The American Reader.

Kickoff

The World Cup begins now. Jonathan Wilson and Rowan Ricardo Phillips will write dispatches for The Daily; here, they introduce themselves and the games.

Jonathan Wilson, from London:

“All the new thinking is about loss. In this it resembles all the old thinking.” That’s Robert Hass, in the opening of his great poem “Meditation at Lagunitas.” The lines resonate: earlier this week, before departing for the World Cup in Brazil, the U.S. national team coach Jurgen Klinsmann, who is German, asserted, “We cannot win the World Cup,” and it didn’t go down well. At least one pundit suggested that he should “get out of America.”

In soccer-saturated London, where I arrived last week, Klinsmann’s remarks might have elicited a more sympathetic response. England hasn’t won the World Cup since 1966, and this year’s team is generally considered transitional, unformed, untested. However, with the kind of twisted logic that applies to soccer supporters worldwide, the dominant “not a hope” take on England’s chances has subtly transformed in recent days to a “well, there are no expectations, so the pressure’s off, so in fact that could translate into improved performance, so hmm, well maybe, just maybe…”

England’s manager, Roy Hodgson—who’s a bit grumpy, has interesting hair, is undoubtedly the most literary figure England has ever employed (The Guardian reported that he read Laurent Binet’s novel HHhH on the flight to Rio), and likes to rib the press about their obsessions with certain players and the hysterical pressure they exert on him to play them—recently succumbed to the dangerous new optimism. He announced that England was indeed capable of winning. Even so, (almost) all the new thinking is still about loss, and in this it resembles the thinking of populations in participating countries worldwide, unless you happen to be from Brazil or Argentina, or maybe Germany— although not so much now that their star midfielder, Marco Reus, has torn his ankle ligaments and is out for the duration.

This isn’t to say that Brazil or Argentina must triumph, although no team from outside South America has ever won the World Cup when it has been played there, but simply that when it comes to international soccer, American over-optimism is rarely in evidence except for, as you might expect, in the minds and hearts of Americans. Nobody, of course, who knows anything at all about soccer, thinks that the U.S. can win the World Cup, and to compound matters the team is in a group of death with Ghana, Portugal, and Germany. In the furor over Klinsmann’s remarks and his subsequent refusal to back down, I was reminded of the time that Ronald Reagan came on TV after he’d traded arms for hostages and announced that even though it looked like he’d done exactly that, in his heart he knew that he hadn’t. American hearts can be frequently, powerfully, and touchingly resistant to reality.

England’s first game is against Italy on June 14, and it takes place in Manaus, in the heart of the Amazonian rainforest. It’s where Werner Herzog went to make Fitzcarraldo, a wildly improbable and troubled shoot documented in hallucinatory prose in his book Conquest of the Useless. But dragging a ship over a steep hill (the locus insanus of Fitzcarraldo) is as nothing compared to the efforts the Brazilian government made in creating the 42,000-seat Arena Amazonia: three men died during construction and the cost ran to $275 million. The tragic beauty of the enterprise has been lost on Roy Hodgson, who some time ago alienated the local population by mouthing off about the inhospitable heat and humidity of the city. In response, Manaus’s mayor, Arthur Virgilio, let it be known that neither Hodgson nor his team was welcome in his bailiwick. Meanwhile, the Italian coach, Cesare Prandelli, wisely kept his thoughts to himself.

Here we are, ready to go. In recent days, John Oliver’s rant slamming soccer’s governing body, FIFA, has gone viral; the Sunday Times in the UK has exposed the way in which a certain Qatar official appears to have bribed a clear path for his country to host World Cup 2022; the New York Times has revealed that before World Cup 2010 in South Africa, a match-fixing syndicate headed by the Singaporean Wilson Raj Perumal got to some referees; there are burning tires and a strike in the streets of Sao Paulo; military police are patrolling the favelas in Rio; some of the showcase stadiums are still under construction. And yet the worldwide TV viewing audience for today’s opening match between Brazil and Croatia is expected to be around two hundred million.

As Aristotle wisely noted, “Man is a goal-seeking animal.”

* * *

Rowan Ricardo Phillips, from New York:

This World Cup will be the tenth of my lifetime, which is a far more pleasant way for me to face the fact that, barring a really bad turn of events, I’ll turn forty this year. Byron had his yellow leaf—that “My days are in the yellow leaf” from his “On This Day I Complete My Thirty-Sixth Year”—which is an echo of Macbeth’s “My way of life / Is fall’n into the sea, the yellow leaf”; and I have my World Cups, amassing like seasons, rejuvenating me but also bringing to light my age.

I won’t lie to you: a World Cup to me is like a first day of snowfall, nothing more and nothing less. It’s as grand and as meager, as regular in the world of sublime things. If the game of football isn’t for you, if the World Cup is something you confuse with the World Series and think happens every year, no worries. But stick around, take a few minutes to kick back. Let’s share a guilty pleasure or two.

I’ve seen six World Cups from New York City, one from Providence, and one from Barcelona. Each of these cities conditioned the experience more than did the places where the Cup was held. In 2006, I watched France hammer Brazil, 3-0, in the stunned silence of a Brazilian household in Rhode Island. I like to think I’m a respectful person—I wasn’t going to walk into someone’s house, eat his food, then outwardly root against his country—but I had been silently favoring France. As the halftime whistle blew and Brazil was down, the kind and always smiling professor I was staying with walked calmly over to his VCR. He pressed stop, carefully removed the tape from the machine, placed it on the floor, and jumped up and down on it with both feet as if it were a joyless trampoline. When the game ended, I left without saying good-bye, like people always seem to do on TV, just hanging up.

New York this year may not offer such an experience, but I hope it’ll be close enough. Bars and restaurants have hung flags out front, some displaying the flags of every nation and others flying only one or two, trying to anticipate the preferences of their clientele. The Argentine restaurant near my house had large Brazilian and Argentine flags side-by-side under their main sign, a mind-blowing disappointment; I had to stop and take a picture. A line from The Inferno came into my head: “intrai per lo cammino alto e silvestro,” roughly, “I entered on the deep and savage way.” Many bars you thought you liked will betray you this month, but once the U.S. gets knocked out, everything will be the same, everything will be in its right place. In November, when I turn forty, a stadium in Manaus will shine untouched in the summer sun like a taut navel swimming in oil. In mid-July, after Brazil has won the Cup, the Hamptons will be the next thing to fall for.

Constant Freshness

A manuscript page from “Reading Rorty and Paul Celan One Morning in Early June,” an unpublished—or at least unpublished ca. 1989—poem by Charles Wright.

Congratulations to Charles Wright, who was announced today as America’s next poet laureate. James Billington, the librarian of Congress, said that Wright’s poems have “an infinite array of beautiful words reflected with constant freshness” and commended his “combination of literary elegance and genuine humility—it’s just the rare alchemy of a great poet.”

Wright has received, , “just about every other honor in the poetry world, including the Pulitzer Prize, the National Book Award, the Bollingen Prize and the Ruth Lilly Poetry Prize.”

The Paris Review interviewed Charles Wright in 1989 for the Art of Poetry series; he said of the form,

There seem to me to be certain absolutes in whatever field of endeavor one is in. In business and banking they may be availability and convertibility, security and safekeeping, minimal loss and steady, incremental accession. I don’t think it’s that way in poetry, though such values will get you to temporary high places. Brilliance is what you reach for, language that has a life of its own, seriousness of subject matter beyond the momentary gasp and glitter, a willingness to take on what’s difficult and beautiful, a willingness to be different and abstract, a willingness to put on the hair shirt and go into the desert and sit still, and listen hard, and write it down, and tell no one.

We’re happy to have published six of Wright’s poems in our Summer 2008 issue. Here’s one of them, “In Memory of the Natural World”:

Four ducks on the pond tonight, the fifth one MIA.

A fly, a smaller than normal fly,

Is mapping his way through sun-strikes across my window.

Behind him, as though at attention,

the pine trees hold their breaths.

The fly’s real, the trees are real,

And the ducks.

But the glass is artificial, and it’s on fire.

We wish Wright all the best in his new role.

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers