The Paris Review's Blog, page 691

June 23, 2014

Life Before QWERTY

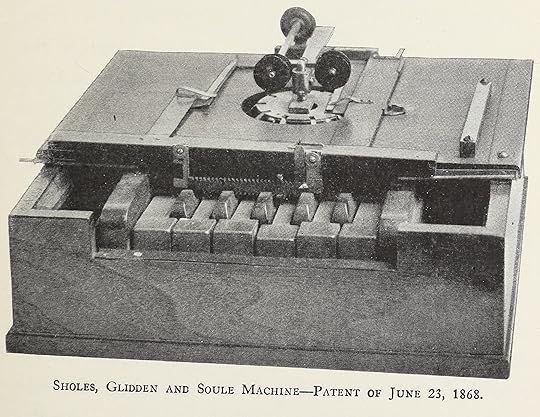

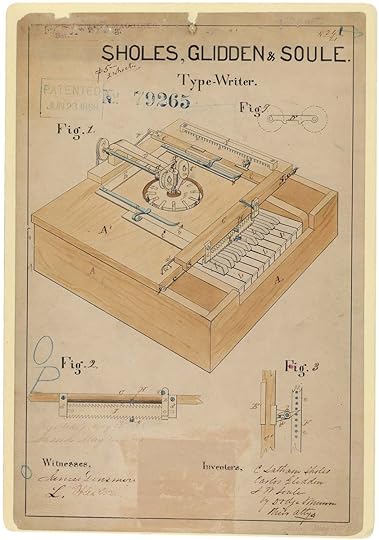

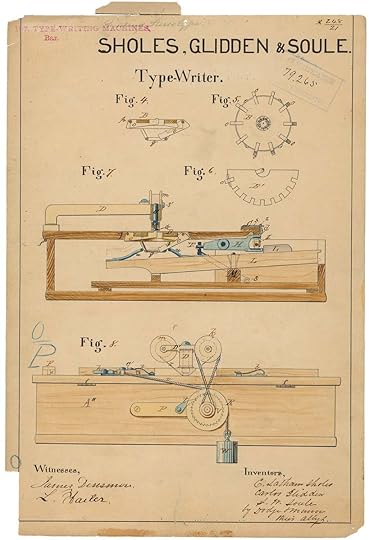

The history of the typewriter is, as with the history of the personal computer after it, rife with collaboration, ingenuity, betrayal, setbacks, lucre, acrimony, misguided experimentation, and bickering white men. There are rough analogs for Bill Gates and for Steves Jobs and Wozniak (though there’s no one so delirious and insane as Steve Ballmer)—and one such analog is Christopher Latham Sholes, a Milwaukee printer whose first “type-writer” was patented 146 years ago today.

Sholes is widely credited with having invented the first QWERTY keyboard. It helped to prevent jams and increase typing speeds by putting frequently combined letters farther apart—but that took years of trial and error; the initial iteration of his typewriter was far more rudimentary in design. It looks like a miniature piano crossed with a clock and/or a phonograph and/or a kitchen table—and Sholes did, in fact, design the prototype out of his kitchen table. As you can imagine, it didn’t boast what today’s designers would call “intuitive UX.” Its keys, borrowing from innovations in telegraphy, were arranged as such:

3 5 7 9 N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z

2 4 6 8 . A B C D E F G H I J K L M

Notice the absence of 0 and 1; Sholes and his cohort assumed that people would make do with I and O. They also couldn’t be bothered with lowercase letters—the first Sholes model was in a condition of eternal caps lock, doomed to permanent shouting. And yet in another sense Sholes was full of intuition and prescience: purportedly, the first letters he typed on the machine were “WWW.” George Iles’s 1912 book, Leading American Inventors, describes the mechanics:

The first row is of ivory, duly lettered; the second row is of ebony; and then, as you see, a third row, made up of letters and characters that are little used, is in the form of pegs. The framework is of wood, with the leverage below, and the basket form of typebars above closely resembles those of some machines in use today. The original model was very clumsy and weighty. The writing was on a tape of tissue paper, and the platen was fastened to the body of the boxlike affair. The writing could not be seen till it was completed, and when the document was once removed from the machine there was no way by which it could be replaced with any degree of certainty that the lines would correspond with those previously written.

As an early developer declared, “It was good for nothing except to show that its underlying principles were sound.” But its technical advances, enumerated below, were enough to earn it a patent, and to attract the attention of investors and fellow inventors:

As an early developer declared, “It was good for nothing except to show that its underlying principles were sound.” But its technical advances, enumerated below, were enough to earn it a patent, and to attract the attention of investors and fellow inventors:

(1) A circular annular disc, with radial grooves and slots to receive and guide the typebars so that they struck the center. (2) Radial typebars to correspond with this disc. (3) A ratchet to move the paper-carriage by the breadth of a tooth when a key was struck. (4) A hinged clamp to hold the paper firmly on its carriage.

Sholes was intent on winning over the stenographer demographic—he assumed such workers were the likeliest customers, and that they would do the most to improve the product—so he did the natural entrepreneurial thing and hired a consultant. He sent James Ogilvie Clephane, a renowned court reporter in Washington, D.C., an early model and told him to give it hell. Clephane did; so unforgiving was his field-testing that he destroyed a succession of costly prototypes, and he told Sholes in no uncertain terms that his typewriter was garbage. But his brutal feedback began the long process that culminated in the QWERTY design.

Not that this was a cakewalk; Sholes and his companions went through years of prototypes, and fell deeply into debt, before they arrived at a marketable model, and even then, in 1874, no one really wanted the typewriter, known by that point as the Remington 1. It cost $125, a small fortune for the day, and typewritten correspondence was stigmatized as impersonal and impolite. Sholes faced competition from a league of rival manufacturers, many of whom he’d once worked with.

Still, in its incipient form, Sholes’s machine was at least fun to develop. Leading American Inventors includes this bucolic account of work in the Milwaukee mill where he held court with his colleagues, Carlos Glidden and Samuel Soule:

Still, in its incipient form, Sholes’s machine was at least fun to develop. Leading American Inventors includes this bucolic account of work in the Milwaukee mill where he held court with his colleagues, Carlos Glidden and Samuel Soule:

In that grimy old mill on the Rock River Canal there were interludes to lighten and brighten the toil of experiment. All three partners were chess players of more than common skill, and they often turned from ratchets and pinions to moves with knights and pawns. Ever and anon a friend would drop in, and the talk would drift from writing by machinery to Reconstruction in South Carolina, or to the quiet absorption by farms and mills of the brigades mustered out after Appomattox. Then, with zest renewed, the model was taken up once more, to be carried another stage toward completion. One morning it printed in capitals line after line both legibly and rapidly. Sholes, Soule, and Glidden were frankly delighted.

Today the site is marked with a reverent plaque, courtesy of the Milwaukee County Historical Society, which buoyantly claims that “C. Latham Sholes perfected the first practical typewriter.” Would that it were so.

The Vestigial Clown

Detail from Hans Breinlinger’s The Clown, 1948.

Yesterday, a friend and I entered into a great debate. It started with my question:

“Does the clown exist who could make you laugh?”

He said yes; he thought that clown who does the act with snow off Union Square would make him laugh. (The show is lauded for its masterful clown-craft and its evocation of childlike wonder.)

“Okay,” I said, “has a clown ever made you laugh?”

“Of course not,” he said.

Does anyone expect to be amused by clowns in this day and age? We all know that clowns are creepy, clowns are scary, clowns are lame—but that understanding has always been predicated on the understanding that, like dolls, clowns are supposed to be happy, fun, innocent. Thus, when a clown goes psychotic, it is doubly terrifying. Or it was thirty years ago, at least. Now, in a world of John Wayne Gacy and It and Insane Clown Posse and Diddy’s coulrophobia-driven “no clowns” rider, we expect clowns to be sinister.

Take this recent survey of kids in children’s hospitals, a historical clown stronghold:

More than 250 children aged between four and sixteen were asked for their opinions—and every single one said they disliked clowns as part of hospital decor.

Even some of the older children said they found clowns scary, Nursing Standard magazine reported.

The youngsters were questioned by the University of Sheffield for the Space to Care study aimed at improving hospital design for children.

“As adults we make assumptions about what works for children,” said Penny Curtis, a senior lecturer in research at the university.

“We found that clowns are universally disliked by children. Some found them frightening and unknowable.”

We are clearly witnessing the last gasp of the clown as a phenomenon, as opposed to the clown as a signifier. Clowns, in other words, seem doomed to become the new mimes. When was the last time you saw a real-life, earnest mime in the wild—as a performer as opposed to a punch line? And yet, presumably, any small child can identify a mime.

The scary clown isn’t a new idea—in 1892’s Pagliacci, after all, the title character murders his wife in full commedia dell’arte regalia. The historian Andrew McConnell Stott, who wrote a biography of the pioneering whiteface clown Joseph Grimaldi, actually credits Charles Dickens with creating the trope. According to an article last year in Smithsonian,

Grimaldi’s real life was anything but comedy—he’d grown up with a tyrant of a stage father; he was prone to bouts of depression; his first wife died during childbirth; his son was an alcoholic clown who’d drank himself to death by age 31; and Grimaldi’s physical gyrations, the leaps and tumbles and violent slapstick that had made him famous, left him in constant pain and prematurely disabled. As Grimaldi himself joked, “I am GRIM ALL DAY, but I make you laugh at night.” That Grimaldi could make a joke about it highlights how well known his tragic real life was to his audiences.

Enter the young Charles Dickens. After Grimaldi died penniless and an alcoholic in 1837 (the coroner’s verdict: “Died by the visitation of God”), Dickens was charged with editing Grimaldi’s memoirs. Dickens had already hit upon the dissipated, drunken clown theme in his 1836 The Pickwick Papers. In the serialized novel, he describes an off-duty clown—reportedly inspired by Grimaldi’s son—whose inebriation and ghastly, wasted body contrasted with his white face paint and clown costume. Unsurprisingly, Dickens’s version of Grimaldi’s life was, well, Dickensian, and, Stott says, imposed a “strict economy”: For every laugh he wrought from his audiences, Grimaldi suffered commensurate pain.

Stott credits Dickens with watering the seeds in popular imagination of the scary clown—he’d even go so far as to say Dickens invented the scary clown—by creating a figure who is literally destroying himself to make his audiences laugh. What Dickens did was to make it difficult to look at a clown without wondering what was going on underneath the makeup: says Stott, “It becomes impossible to disassociate the character from the actor.” That Dickens’s version of Grimaldi’s memoirs was massively popular meant that this perception, of something dark and troubled masked by humor, would stick.

The truly jolly clown, in fact, was a more modern figure. Certainly, he had no heyday like the early days of TV, when the clown-hosted children’s show was ubiquitous. A figure both fun and authoritative, the clown—in what now feels like a historical anomaly—surely served as a needed liaison to the grownup world. Now—as in most ages past—children view strange, saturnalian grownups with suspicion. It’s amazing that Ronald McDonald has held on, a friendly emissary from a different world.

It makes sense that the clown’s star should wane somewhat. After all, many of the societal roles of the clown—those of emotional outlet, societal commentary, transference—are now enacted by any number of other media. We have movies, we have TV, we have standup; comedy is so integrated into the fabric of modern life that the idea of a dedicated clown feels as anachronistic as that of a sin-eater.

I’m not qualified to get into the historical implications of clowning, but I do know this: it’s fascinating to live in a time when everything is shifting before our eyes. These shifts aren’t novel anymore, as life-changing technology must have been for our great-grandparents. They’re not scary, as the upheaval of the sixties would have been to an older generation, or indeed so exciting as that same period was for my parents. But we’re now hyperaware of every shift: we may be inured to the pace of change, but we monitor it closely.

Over the weekend, my dad mentioned that in the clown-mad 1950s, his parents came back from a trip to Venice with a bunch of glass clowns. Now, such a souvenir would seem not just creepy, but tacky, too. Mine is probably one of the last generations to have much to do with jolly clowns; I remember a short-lived cartoon called Little Clowns of Happy Town in the 1980s. I’m dating myself; writing in the Guardian in 2012, Stuart Kelly referred to the scary-clown trope as “almost nostalgically fearful”—a delicious contradiction.

Win, Lose, or Draw

What next for Team USA?

Jermaine Jones in 2013. Photo: Erik Drost, via Wikimedia Commons

Jonathan Wilson, from London:

Twenty years ago, I was in Giants Stadium watching the 1994 World Cup quarterfinal between Germany and Bulgaria. A group of cheerful German supporters unfurled a large banner that read, IT’S NOT A TRICK … IT’S GERMANY!!! This intriguing and challenging work of art (text, textile, mixed media, probably influenced by Joseph Beuys) baffled me for many years, right up until last night, when Jermaine Jones—the USA’s German-born, all-action midfielder—curled a superb “take that, Lionel Messi!” right-foot shot from the edge of the area into the far corner of Portugal’s net. Wowsers, I thought. It wasn’t a trick … it was Germany.

Last week, on Sports Illustrated’s Planet Futbol site, Grant Wahl reflected on the high number of dual nationality German American players on the U.S. team—there are five, and it’s common “to hear [them] speaking to each other in German.” Wahl speculated that if, in 1981, the year Jermaine Jones was born, the U.S. had had as many American servicemen in Brazil as in Germany (there were 222 and 248,000, respectively) we might have a really spectacular team by now. Improving your team by selectively locating your armed-forces bases: it’s an interesting Freakonomics- or Gladwell-type theory, but it might need some tweaking in light of the results so far at this year’s tournament. America’s long engagements in Iraq and Afghanistan, I suspect, will produce negligible returns on the soccer field. These countries aren’t soccer powers, and we probably won’t hear anyone shouting across the field in Pashto, Dari, or Mesopotamian Arabic at the next World Cup. Certain teams, however, are clearly on the way up, and I’m thinking now that a base or two in Costa Rica, Algeria, Iran, and Mexico—where there are, at present, none at all—wouldn’t hurt. On the other hand, we might as well close those in Portugal, Australia, England, and Greece.

But what a game the USA played against Portugal yesterday. Tim Howard made one of the best saves of the tournament, and Clint Dempsey, with his badge-of-honor broken nose and black eye, chested in a goal that, until the very last kick of the game, looked to be sending the USA into the round of sixteen. Instead, defensive lapses—which appeared the result of miscommunication at the back; can the rest of the team please get on board with the German?—led to Ronaldo, who hadn’t really been much of a factor for the previous ninety-four minutes, sending in a perfect cross for Varela to head home and equalize.

So the U.S. must gather itself for one last go-round with—who else?—Germany. A draw is a likely result—a draw of the sort sometimes subtly engineered by teams for whom it’s mutually beneficial, as it would be in this case.

There are, per Wikipedia, fifty million Americans who were either born in Germany or are of German descent, which makes it the largest “ancestry group” in the nation. My guess is that a number of them swelled the outdoor crowd in Chicago yesterday evening, watching the big screen and going wild. Even more will come out on Thursday. Soccer, baby, the eagle has landed. It’s not a trick … it’s the USA.

* * *

Rowan Ricardo Phillips, from New York:

The only more pernicious chimera than the myth of consistency is that of constant improvement. I may not write as well tomorrow as I write today, nor am I better person for every mistake I make. I cheer myself, then, with the simple belief that feeling shame for my failures and regret for my missed opportunities is a waste of time. Every day is a commitment to that day, every syllable uttered or written down is a link to a greater chain—but it’s still just a link, and links by necessity have gaping holes in them.

These beliefs can make me a lousy person to watch a football game with. I wince at missed passes and good runs into space that the player on the ball doesn’t see; I barely flinch when goals are scored, almost scored, or acrobatically denied. Goals are the outcome of hundreds of little and forgotten movements and mistakes. Results are the cover art of the narrative. But who knows what the narrative really is? When he was coaching Real Zaragoza in 1979, the Serbian Vujadin Boškov, who passed away this year, described in his challenged Spanish the game as a tautology, a simple and yet vexed chain of truths: “Fútbol e fútbol, e gol e gol.” It’s become a truism in Spain about the game. Why do unpredictable, maddening things happen in the game? Because football is football, the goal is the goal.

The great support that the U.S. has received since Monday’s 2-1 victory over Ghana was solely the fruit of their goals. The team was in shambles—stretched thin at the back, disconnected in the midfield, incoherent up front, and incapable of stringing together a simple chain of passes. It was the worst performance by a game-winning World Cup team that I can remember seeing. And yet they won. That they ended up scoring on a corner kick—fumbled to them by the Ghanaian defender Jonathan, a very good player who tried to usher out a heavy U.S. pass, only to have the ball bounce up and off his leg at the last instant—was beside the point. They had won, and they had finally, in their third consecutive attempt at a World Cup, beaten the Black Stars of Ghana. The rest is silence.

Winning, the thinking goes, invites confidence. And it did: last night, the United States team that played Portugal was completely unrecognizable from the team that had played Ghana just a few days ago. They were compact, clear in their ideas both with and without the ball. They looked for offensive advantages and, when their passing didn’t let them down, they played for those advantages, creating pressure instead of absorbing it. They trusted their heads to sort out problems that mere lung-busting effort could never solve. It was, considering the context, the best U.S. performance I’ve seen since the 2002 World Cup.

And yet they drew.

Certainly they will try, but in this tournament they will never play better. The U.S. midfielder Michael Bradley has been taking a tremendous amount of heat for losing that final possession, which led, mere seconds later, to Silvestre Varela’s emphatic diving header, a goal Eusébio himself, the black panther of football, would have been proud of. Bradley has been just about the worst player in the tournament thus far: he’s unable to pass either perceptively or safely, and despite his shaved head and permanent scowl—the typical accoutrements of a hardman in football—he’s been a veritable turnstile on defense. But, to his credit, Bradley tried to play the ball. He wasn’t looking to boot it into the soupy air above the Arena Amazônia, as far away as possible from him or any other player. He tried to control the ball. He wanted the responsibility of the moment, he wanted—like we all do when we play and dream of playing in the World Cup—the ball at his feet. It didn’t work out. Football is football.

Now the United States is set to face Germany. The general sense seems to be that if the team can play as they did against Portugal, they can do so against Germany. The Ghana performance seems to have been deleted from the memory banks of American fans. But Germany is an entirely different order of problem than Portugal. They have significantly better players, and their style of play will ask questions of the U.S. game plan that Portugal’s did not. Germany will press the U.S. everywhere on the field, forcing them to make assured controls and to pass the ball with quick and assertive precision. In short, what Germany does incredibly well without the ball is exactly what the U.S. does incredibly poorly with the ball.

There was immediate talk, as Jonathan mentions above, about the possibility of the two teams conspiring for a draw so that they both qualify for the next round. A draw, after all, is all that would take. This has happened once before with Germany, in the 1982 World Cup, when West Germany and Austria made a pact to coast through an easy game so both would advance in the tournament. But the world has changed since then: West Germany doesn’t exist, and this German team may have more ties to Ghana than to the U.S. There’s one Boateng brother on the German team, for example, and another on the Ghanaian team. Besides that, the Polish German striker, Miroslav Klöse, is one goal away from becoming the all-time leader in goals scored in a World Cup.

No matter what happens against Germany, I trust the draw against Portugal will, in the long run, bring more joy in its remembrance than the win against Ghana. Call me crazy, but you don’t play to win the game—you play to play the game.

Jonathan Wilson’s work has appeared in The New Yorker, Esquire, The New York Times Magazine, and Best American Short Stories, among other publications. He is the author of eight books, including Kick and Run: Memoir with Soccer Ball. He lives in Massachusetts.

Rowan Ricardo Phillips’s second book of poems, Heaven, will be published next year. He is the recipient of the 2013 PEN/Joyce Osterweil Award and a 2013 Whiting Writers’ Award.

Recapping Dante: Canto 33, or History’s Vaguest Cannibal

Gustave Doré, Canto XXXIII

We’re recapping the Inferno. Read along! This week: a Sophie’s Choice in medieval Pisa.

Here we meet the last great sinner of the Inferno: Count Ugolino. Like the others, he’s a historical figure remembered today chiefly for his appearance in Dante’s poem; and in spite of everything he confesses in these few verses, we inevitably pity him.

At the end of canto 32, Dante finds Ugolino gnawing violently at the head of another sinner, Archbishop Ruggieri. Ugolino tells Dante that he will describe his own crime, and allow Dante to determine which of the two of them is the greater sinner.

Ugolino, a magistrate, was charged with betraying the city of Pisa—he gave three of their fortresses to a neighboring town—and for this he was locked, along with his four children, in a tower there (not the one you’re thinking of). One night, he dreamed that he and his young children appeared as wolves; they were hunted and torn to shreds. He awakes to find his children crying in hunger for food, but when mealtime in the tower arrives, Ugolino hears the doors being nailed shut.

He understands that he and his children will starve to death. Seeing them in agony, he begins to gnaw at his own hands, and his sons say, “Father, we would suffer less if you would feed on us.” Ugolino composes himself and watches his children die slowly of hunger over the course of the fourth, fifth, and sixth days. For two days, Ugolino, who has gone blind from hunger, wails over his children, speaking to them as though they were still alive. And then he speaks one of the most haunting and also perhaps most memorable lines in the Inferno: “Then fasting had more power than grief.” This line has been interpreted variously; some believe it means that he continued to starve, whereas others contend that Ugolino ate his dead children.

After Ugolino speaks these words, he immediately resumes gnawing on Ruggieri in shameful hunger. But Dante has placed Ugolino in the ninth circle, among the traitors, which means he’s damned for his betrayal, not for eating his children. Dante dedicates several likes to chastising Ugolino’s city for punishing the count’s children. It’s a strange break in the poem—seldom does Dante the poet, in his poet’s voice, openly decry the actions of a particular person, let alone an entire government.

As Dante moves on, he sees sinners hanging upside down with their eyes frozen shut: “their first tears become a crust that like a crystal visor fills the cups beneath the eyebrows.” Dante promises one of the afflicted that he will wipe away his tears if the sinner tells him who he is. And once Dante learns that the sinner is Fra Alberigo, Dante casually walks away, breaking his promise—sort of a jerk move, if you ask me. Alberigo had his houseguests assassinated during an argument. Dante has clearly taken a page out of Virgil’s book, and has taunted this sinner after kicking another in the head.

Something spooky happens—Dante feels a wind and wonders where it comes from, since there is no God in hell, and conventional wisdom at the time held that wind was caused by the sun and God. But Virgil tries to change the subject, perhaps because the wind is coming from Satan, and after all, it would be pretty horrifying to learn that you are about to go meet Satan. Dante, Virgil says, will soon discover the source of the wind himself …

To catch up on our Dante series, click here.

Alexander Aciman is the author of Twitterature. He has written for the New York Times, Tablet, the Wall Street Journal, and TIME. Follow him on Twitter at @acimania.

All Aboard for Collectivists, and Other News

A portrait of Ayn Rand. Illustration: Manuelredondoduenas, via Wikimedia Commons

Gordon Lish, at eighty, lives literally in the dark, because of his psoriasis: “His apartment is a crepuscular chamber, largely unchanged since his wife died more than a decade ago. With his heavy knit sweater and wild white hair, which culminates in a braid, he wanders these rooms looking like some cross between an old fisherman and King Lear … The problem with Lish is that he is all over the place. That also happens to be the best thing about him.”

“I hope you don’t have friends who recommend Ayn Rand to you. The fiction of Ayn Rand is as low as you can get re fiction. I hope you picked it up off the floor of the subway and threw it in the nearest garbage pail.” Flannery O’Connor hated Ayn Rand …

… and Rand loved trains. More specifically, she loved to write about morally unworthy people dying in fiery train crashes: “The doomed include everyone from a lawyer who feels he can ‘get along under any political system,’ to ‘an elderly schoolteacher who had spent her life turning class after class of helpless children into miserable cowards’ because they believed in the will of the majority …”

Borges: not a World Cup fan. “Soccer is popular,” he once said, “because stupidity is popular.”

Further evidence that writing may be, you know, creative: scientists tracked “the brain activity of both experienced and novice writers … The inner workings of the professionally trained writers in the bunch, the scientists argue, showed some similarities to people who are skilled at other complex actions, like music or sports.”

June 20, 2014

What We’re Loving: Reckless Love, Love via Telegraph

From an early twentieth-century postcard. “Kisses from both are now flying about / Where all of a sudden the current runs out.”

After reading David Constantine’s story “In Another Country,” which the Canadian publisher Biblioasis passed along to me, I can’t figure out why a U.S. press hasn’t caught on to his work. He’s won a number of big prizes, including the Frank O’Connor International Short Story award twice—last year, he beat out Joyce Carol Oates, Deborah Levy, and Peter Stamm—and no wonder: this story has me wanting more. (Thankfully, Biblioasis will publish a selection of his stories next year.) The sentences are restrained, the tone muted. The remoteness between the husband and wife of the story is never described but is made palpable through the stillness in their interactions and the spareness of the prose, but the tension created by the slow unraveling of the past within the present is innervating: “What worried Mrs. Mercer suddenly took shape. Into the little room came a rush of ghosts. She sat down opposite him and both felt cold. That Katya, she said. Yes, he said. They’ve found her in the ice. I see, said Mrs. Mercer.” If you get excited, as I do, by stories in which very little happens, then this one is for you. —Nicole Rudick

In 1949, Niki de Saint Phalle and Harry Mathews eloped together, both a bit shy of their twentieth birthdays. The ten-year marriage that followed saw joy, sorrow, electroshock therapy, disapproving parents, reprimanding neighbors, two children, suicidal episodes, numerous infidelities, artistic awakenings, homes in more than four countries, and, ultimately, insurmountable growing pains. In Harry and Me: 1950–1960, The Family Years, de Saint Phalle chronicles their famous, tumultous relationship in verse and image. A remarkably generous portrait of their time together—it includes sidebars of text written by Mathews in response to de Saint Phalle’s account, in which he corrects and addends but never criticizes—this book is a must-read for anyone interested in the work of either artist. Their developmental years were spent in stride, and the naïveté that brought them together (and eventually drove them apart) was instrumental in shaping their artistic desires, particularly the whimsy and color that marks de Saint Phalle’s sculpture. Though the relationship ends, the children suffer, and the hurt never truly goes away, neither party, many years later, seems to regret the marriage. Instead, they go to bat for the young, reckless love that directed the course of their lives. —Clare Fentress

Lots of people are nostalgic for rotary phones and handwritten letters. Not so many have the same wistfulness for the telegraph. But William Saroyan’s “1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8,” from his 1934 short story collection The Daring Young Man on the Flying Trapeze, has left me rethinking the old teletype machine and its nuanced relation to our digital age. The story tells of two telegraph operators, who meet—virtually—by striking up a conversation over the wires. Saroyan’s depiction of the giddy thrill of instantaneous, faceless communication, in which half the fun is in the imagined possibilities, seems oddly anachronistic to the modern reader, but it also predicts the appeal of instant messaging and texting. From the first hello hello hello, the narrator realizes the untapped opportunity of his teletype machine as a personal device of contact, of love: “I had never thought of the machine as being related in any way to me … I began to try to visualize the girl. I began to wonder if she would go out with me to this house I wanted and help me fill it with our lives together.” —Chantal McStay

For years now, I’ve started every Tuesday with Harper’s Weekly Review, a news digest that never fails to delight and inform. Impassive and compact, the Weekly Review is a marvel of juxtaposition—in its three concise paragraphs, the sublime and the profane are never far apart. Events of massive sociopolitical import sit with constabulary notes from all over. A snippet from the latest, for example: “A Massachusetts law firm that specializes in processing foreclosures was evicted for failing to pay its rent. In Fresno, California, a burglary defendant was stabbed to death by his sister’s boyfriend hours after being mistakenly freed by a jury that had checked the wrong box on a court form. Florida authorities discovered twenty-three grams of marijuana hidden in the rolls of a 450-pound man’s stomach fat.” Nothing else gets at the seriocomic vastness of the news cycle like this. In the diversity of experience it conveys, the Weekly Review often reminds me of a line from The Pale King: “What they’d then thought was the wide round world was a little boy’s preening dream.” —Dan Piepenbring

ESPN’s 30 for 30 documentary series has released a new batch of films on soccer history—as if the World Cup hadn’t already taken over my life—from the Hillsborough disaster and Loughinisland massacre to the mystery of the Jules Rimet Trophy, which has been missing since 1983. Watching the series, the one name I had not heard before was Moacir Barbosa, one of the world’s best goalkeepers, whose reputation was forever altered after Brazil’s defeat by Uruguay in the final match of the 1950 World Cup. The film follows Barbosa’s descent from national hero to pool worker: he spent the rest of his life replaying Alcides Ghiggia’s goal in his head. In an interview soon before his death, he said, “The maximum punishment in Brazil is thirty years imprisonment, but I have been paying, for something I am not even responsible for, by now, for fifty years.” —Justin Alvarez

Most know Thornton Wilder as that guy who wrote the hit play Our Town. But he’s also an awesome novelist. His best is The Eighth Day, a Great American Novel to rival any other that has sewn that badge on its sash. I’m currently finishing up Theophilus North, a novel told in a series of vignettes about the titular character’s various well-intentioned schemes to help residents of Newport, Rhode Island, in the summer of 1926. It’s an entertaining and clever summer read sprinkled throughout with Wilder’s sharp insights into humanity. “‘I can’t stand being loved—love?—worshipped! Overestimation freezes me. My mother overestimated me and I haven’t said a sincere word to her since I was fifteen years old,’” one character says; another responds, “‘All love is overestimation.’” —Andrew Jimenez

Last week, Blake Bailey wrote for Vice about Nabokov’s unpublished notes from the 1962 Lolita screenplay. In March 1960, Nabokov was in California, renting a villa in Brentwood Heights; he met with Stanley Kubrick at the latter’s Universal City Studio, where the two began collaborating on cinematizing the novel. Nabokov was enamored with the task of screenwriting. He noted, years later, that “only ragged odds and ends” of his script were used in the final draft, but Nabokov’s screenplay—like the novel, and like Kubrick’s film—is alive with the incandescent, euphoric Nabokovian voice. His notes give tangible faces to Humbert and Lolita, and his depictions of scenes read like his prose: “In the aura of light from the passage, Lolita sleeps angelically. Tom shakes his head in dismissal of evil, in reaffirmation of young innocence …” —Yasmin Roshanian

Don’t Hold Back

Dan Dailey, Romance, 1987

Each member of my family has quirks and foibles. I stomp my foot like a cartoon furious person when I lose my temper, and I once humiliated myself the one time I attempted the road test by waiting ten minutes to turn at an intersection, panicking, and nearly hitting an oncoming car. My brother pulls a weird, unconscious face whenever he passes a mirror; he will never live down the years he spent, as late as the first grade, refusing to wear clothing. My dad is mocked regularly for getting ketchup all over his face and for insisting on down jackets in seventy-degree weather. And then there’s my mom’s thing. It’s probably very unwise of me to write what I am about to write while I am staying with my parents. But I am, like pope emeritus Benedict XVI, a Servant of the Truth.

Although she’s an excellent cook and great company, my mom is a nervous hostess. She finds the demands of guests and meal-planning onerous—terrifying, even. By the time dinner is served, she has generally worked herself into an anxious frenzy. I’m sure most people at the table can’t tell; to her family, the signs are unmistakable.

At some point in the meal, a wild look will come into her eyes. Her hands will clench. It is as though she is possessed. A conversation may be in progress; someone may be mid-anecdote. It matters not. As though powerless to prevent the words, she will suddenly declaim:

“DON’T HOLD BACK. THERE’S MORE OF EVERYTHING!”

Conversation will cease; guests will thank her politely; things will resume. Having gotten that off her chest, she subsides into more or less normal behavior. Ideally, on these occasions, my brother, Charlie, will be at the table and I can meet his eye.

At a recent barbecue, Charlie ended up seated next to her. And at a certain point in the meal, her hands began to tense spasmodically. We saw The Look overtake her. “Don’t do it. Don’t do it,” my brother muttered to her, but it was too late. And this was one of those occasions when, in fact, there was not enough steak, so it was particularly awkward. Because that’s the really weird part: she’ll say it whether it’s true or not.

When it’s just the family, Charlie or I will usually shout my mother’s line before she has a chance to deliver it herself. Ideally, we try to do it at the least opportune moment—when someone is telling a story or confessing something personal. In fact, one or the other of us shouts the line whenever we eat together.

My mom will get really sad when we do this. In fact, she’ll do what we call “the sad face,” which combines the dolor of the Pièta Madonna with what my dad calls “a sense of profound disillusionment.” I am not proud to reveal that this only serves to increase our glee.

But this isn’t about cruelty; there is the pleasure of insularity, of complicity, of shared history. There is the reassuring sense that nothing ever changes. At least nothing truly important. There is, indeed, always more of everything.

Dear Diary: An Interview with Esther Pearl Watson

Esther Pearl Watson’s comic Unlovable is based on a found diary, from the 1980s, of a teenager Watson has named Tammy Pierce. Tammy lives in a small North Texas town with her parents and younger brother; her life is banal, poignant, and excruciatingly funny. She clings just above the bottom rung of her high school social hierarchy, awkwardly pursues “hot guys,” and is regularly exploited by her best friend, Kim.

In Watson’s hands, however, this is not a coming-of-age story. Expanding on the details of the diary, she amplifies Tammy’s naïveté and absurdity, capturing the grotesqueness of adolescence, how teenagers live in their aspirations and ideals but also in an amplified shame. Watson’s lines are exaggerated and energetic; her characters are sweaty and ugly, their imperfections magnified as if being scrutinized in a sixteen-year-old’s mirror. You feel, vividly, the humiliation of bodies. Matt Groening has called Unlovable “the great teen comic tragedy of our time.”

Watson has been at work on the series for more than a decade, first publishing it as minicomics and on the back page of Bust magazine. The third collected volume of the strip has just been released by Fantagraphics Books—a lime-green, gold-glitter affair that is apt tribute to Tammy’s fervent aspiration to be a makeup artist.

I spoke with Watson over Skype, calling her in Los Angeles from my apartment in Brooklyn. Though she’s well known in the LA art scene, her voice carries the lilt of her own Texan upbringing.

How is Unlovable different from the original diary?

I started keeping a daily diary when I was thirteen—I hoped there was somebody else out there who felt the need to put down what happened every day. My diaries are impossible to read now because they’re so boring. I would write down what I ate, what I wore, trying to make my life sound normal, but I wouldn’t write that my dad was building flying saucers in the backyard.

“Tammy”’s diary was different. I found it in a gas-station bathroom in a sink. Somebody had unloaded a bunch of garbage, piles of clothes. I hid it under my shirt and ran out to the car and said to my husband, Mark, Let’s get out of here, quick! We read it out loud, driving our beat-up car through the desert. It was less than a hundred pages. “Tammy” talked about friends, this whole cast of characters, and she tried to choose between two guys, which one she would go out with. She would sneak out of her bedroom window to hang out with these delinquent kids who you just knew were using her. And you wanted to yell advice at her—That doesn’t mean he likes you, he wants something else! Listen to your mom!

We could all give advice to ourselves at that age.

What was interesting to me about the diary was the hindsight—seeing mistakes, of course, and looking back and realizing that a superpopular song was cheesy, or thinking, Wow, I tried to impress that girl. I don’t know if all that was important, but it really felt like it at the time.

Are you from a small town?

I grew up in the Dallas–Fort Worth area. We moved around a lot because my parents couldn’t pay the bills. And my dad was building flying saucers in the front yard—that never went over well. One of my favorite places we lived was Wylie, Texas. I somehow convinced my parents not to leave Wylie while I was going to middle school. It was the only time I was able to stay long enough to get to know everybody in the school and how they all related, who the good and bad kids were, who had the outsider parents. I like to reference that compact little ecosystem for Unlovable.

Why did you decide to adapt it into a comic?

Mark and I spent many years trying to figure out how to publish the diary. I had a whole stack of rejections for it. I even wrote a young-adult novel based on it. Some of the rejections had to do with the idea that nobody wants to read a real diary, or nobody cares about the eighties—there was a list of reasons people didn’t want to publish it.

Mark had read Marvel and DC comics growing up, but I feel like those comics weren’t really for girls. They were intimidating—the guys are muscular and fighting and harsh and the girls are, too. They’re like guys with giant boobs. I never found them interesting or friendly. So I decided to make a minicomic of it. I thought, I’m going to do everything I was told not to do. I’m going to do everything wrong.

The comic has nostalgic appeal—for the eighties but also for a pre-Internet teenagehood.

It was different then. Tammy spends a lot of time waiting for a phone call, for instance. I remember that being excruciating—the hoping. Then someone else would call, and if you didn’t have call waiting maybe the person you were waiting for called while somebody else was calling! You could ruin an entire day waiting for someone to call.

The anxiety and the longing are timeless. But I’m surprised by the fact that Tammy is cruel as often as she is victimized.

There are moments when Tammy wants to feel on top. She’ll lash out. People say rude things to her, and she can repeat them to the guy who bags her groceries and feel like she’s one of those cool girls at school who always have a comeback line. Unlovable is about showing that we need space in which to be awkward, to learn and figure out what it is we are really trying to say with our actions.

It seems like Kim is the comic’s stealth feminist voice. She shifts suddenly from her usual laconic demand for a dollar in exchange for friendly help to offering a cogent opinion on, say, the hypocrisy of her sex-ed course.

I can only plant it in subtle ways. I always imagined Kim as somebody who doesn’t have the best home life but has the most potential out of all the characters. We tend to judge someone so quickly—Kim is a nightmare and Tammy should get far away—but Kim might turn out to be the one person who actually understands how the system works. She might be able to make the system work for her very well. Tammy is crudely repeating social patterns and has not quite figured out gaining and using power. But Kim has.

The series began as minicomics, which you sent to potential illustration clients. Then you moved into the DIY zine scene, exhibiting at conventions. How does zine culture intersect with comics and indie comics and the art world?

In the beginning, in 2003, I felt like I was wearing separate hats. I was selling paintings, I was doing illustration for commercial magazines, and I was publishing children’s books. Mark and I had written a book, Whatcha Mean, What’s a Zine?, which was published by Houghton Mifflin, a major publisher even though the book was about alternative media. Then, we started to go to conventions, where all these different zine publishers were either trying to subvert the commercial world or hoping to get into it. We were going backward—we already had established careers and suddenly we’re trying to sell our promo material for two dollars.

But something really interesting has happened with Unlovable. It does cross genres. It’s sold in bookstores and it’s part of alternative zine culture, but I would also hang it in a gallery as fine art.

You don’t use multiple panels on each page, as most comic books do, but rather a single image on each page.

I’m a painter, and I imagine each panel in comics as a canvas. I used panels for Bust magazine because the story had to be told one page at a time, but I try to avoid using multiple panels in the book form of the comic, too.

I was intentionally trying to disrupt the comic lexicon because I felt like it didn’t belong to me. And I see now how I was trying to create a new language. Sometimes people don’t understand Unlovable because it’s not a very clean, linear story. Its stories are one panel long, or one page long, or sometimes several pages long. Then thrown in there you have Chuck Norris giving Kim bra advice, or Colonel Sanders telling Tammy who she’s dating and who she’s not dating. Teddy Ruxpin pops in to converse. Teens live in a world that’s reality and fantasy at the same time.

Do you still have the diary?

Yes. I tried to get rid of it, burn it at one point. I don’t want anybody to get ahold of it. I want to protect Tammy’s privacy.

The original author listed her first name, and her weight often, but not her address. I know she might be around my age because I relate to the stories, but I would not want to know if one of my diaries had become somebody’s muse.

Meg Lemke is a contributing editor at MUTHA Magazine and chairs the comics and graphic novel programming committee at the Brooklyn Book Festival. You can find her online @meglemke.

Kissing and Biting

Italy puckers up; unhinged American exuberance; infamous teeth.

Luis Suárez in 2011. Photo: Jacoplane, via Flickr

Italy’s Mario Balotelli, he of the “why always me?” undershirt, wants a kiss from the “the UK queen”—yes, that one—if he secures a victory against Costa Rica. The domino effect of that result would go like this: Italy will go on to beat Uruguay while England crushes Costa Rica by some outlandish score and, miracle of miracles, England qualifies for the next round on goal difference. From my brooding vantage—looking out at the low dark clouds gathered over the sceptred isle this morning—a little royal peck on the cheek doesn’t seem too much to ask for Mario’s compliance. He should go for more—but maybe not from the queen.

All sports aficionados are historiographers. Fans of, say, the Chicago Cubs or the Boston Red Sox before 2004 “remember” failures and disappointments that occurred decades before they were born. Sports talk and commentary worldwide is a litany of reference and record: great names from the past, statistics, moments of triumph and disaster. No game is an island.

Does this explain why the USA’s supporters in Brazil seem to have reached a level of euphoria unmatched by the fans of any other country? I mean, they’re really going bonkers over there, and there’s something entirely unhinged about it. What the crowd is unhinged from, of course, is the past, the dead Wrigley Field weight of history that tells you, “Don’t even think about it.”

As Henry James, author of “The Jolly Corner,” which I’m guessing is a soccer story, once wrote: “It takes an endless amount of history to make even a little tradition.” The USA soccer team has no tradition that anyone really recalls. Its forays into world soccer are each time fresh and new, although, given the way that interest in the game is mushrooming across the fifty states, this may well be the last year we’ll be able to say that.

If only that were the case in England, where the postmortem on yesterday’s disastrous game with Uruguay is haunted by the ghost of losses past. “Same old England …” is the Big Match Verdict of the daily tabloid the Sun. Same old Luis Suárez, too, unfortunately: the Liverpool and Uruguay striker, who had keyhole surgery on his knee only four weeks ago, returned to torment his opponents with one deft, superb header and the punishing winner after a terrible mistake by England’s captain Steven Gerard: a brutal, ferocious right foot shot past Joe Hart, bulging the net.

In England, nobody seems quite ready to let go of the facts that Suárez (1) has a large and distinctive set of teeth and (2) used them to bite the PSV Eindhoven midfielder Otman Bakkal back in 2010 and the Chelsea defender Branislav Ivanovich just over a year ago. Today’s newspaper headlines include OUR WORST BITEMARE and IT HAD TO BE CHEW. Even the upmarket lefty Guardian, usually so sensitive to the lives of others, led its front page with ALL BITE ON THE NIGHT: SUÁREZ SENDS ENGLAND TOWARDS WORLD CUP EXIT.

But what a glorious World Cup this is turning out to be: out of thirty-two teams, only Iran, Nigeria, Japan, and Greece have found ways to bore everyone to death. Meanwhile there are wonderful upstarts: the frequently slighted CONCAAF teams, Mexico, USA, and Costa Rica; Chile playing with speed, skill and passion; an ever-improving Croatia; and now Uruguay, back in the ascendancy. Three of these countries—you can figure out which—have populations of less than five million. But maybe that’s an advantage. Neither China nor India came close to making it through to Brazil.

Jonathan Wilson’s work has appeared in The New Yorker, Esquire, The New York Times Magazine, and Best American Short Stories, among other publications. He is the author of eight books, including Kick and Run: Memoir with Soccer Ball. He lives in Massachusetts.

“Aestheticized Loot,” and Other News

“Six different artists made these paintings.” Photo via Vulture

An excerpt from Marilynne Robinson’s next novel, Lila .

Discovered: twenty unpublished poems by Neruda.

“As video games move from amusements to art, game designers should be increasingly concerned with presenting moral dilemmas in their games … Rather than having choices presented ‘as either/or, good/bad binaries with relatively predictable outcomes,’ games should strive to present ‘no clear narrative-or-system-driven indication as to what choice to make.’”

The photographer Eilon Paz has released Dust & Grooves: Adventures in Record Collecting , featuring pictures of, yes, record collectors and their daunting collections. Among the specialists: a guy who only collects The White Album; a guy who only collects Sesame Street records; the Guinness World Record holder (no pun intended) for largest collection of colored vinyl.

“A large swath of the art being made today is being driven by the market, and specifically by not very sophisticated speculator-collectors who prey on their wealthy friends and their friends’ wealthy friends, getting them to buy the same look-alike art … It’s colloquially been called Modest Abstraction, Neo-Modernism, M.F.A. Abstraction, and Crapstraction. (The gendered variants are Chickstraction and Dickstraction.) Rhonda Lieberman gets to the point with ‘Art of the One Percent’ and ‘aestheticized loot.’ I like Dropcloth Abstraction, and especially the term coined by the artist-critic Walter Robinson: Zombie Formalism.”

Among the World Cup’s rules and regs: sex laws. Some teams are banned from pregame intercourse; others are only barred from certain forms of it. E.g.: “France (you can have sex but not all night), Brazil (you can have sex, but not ‘acrobatic’ sex), Costa Rica (can’t have sex until the second round) and Nigeria (can sleep with wives but not girlfriends).”

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers